1. Introduction

The building sector is a significant source of global carbon emissions, accounting for about one-fifth of worldwide emissions [

1]. Carbon emissions over a building’s life cycle can be divided into operational carbon (from energy use during building operation) and embodied carbon (generated across all stages from raw material extraction, manufacturing, transport, and construction, to end-of-life processing) [

2,

3,

4]. For decades, extensive research has focused on reducing operational carbon (e.g., energy-efficient design, renewable energy integration), whereas systematic studies on reducing embodied carbon remain noticeably insufficient [

5,

6,

7]. Among the many factors influencing embodied carbon, building service life is paramount: extending a building’s lifespan spreads one-time construction emissions over a longer period and reduces the material production and waste disposal from frequent rebuilds, thereby effectively lowering embodied carbon per unit time [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Studies have shown that lengthening a building’s service life from 50 to 150 years can significantly reduce the average annual embodied carbon; by contrast, short-lived buildings (e.g., 50 years) can accumulate up to three times the emissions of longer-lived ones (e.g., 80 years). In general, the longer the service life, the lower the cumulative embodied carbon [

14,

15,

16]. In other words, extending building lifespan to avoid reconstruction yields significant carbon reduction benefits.

However, in practice, it is difficult for residential buildings to remain “as-built” over the long term, because occupant needs and environmental conditions are constantly changing. Many residential buildings are demolished prematurely, well before reaching their designed lifespan, thus failing to realize the carbon-reduction potential of longer life [

11,

17,

18,

19]. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in regions of rapid urbanization. In China, for instance, the average actual service life of residential buildings is only 30–35 years, significantly below the 50-year design lifespan and far lower than the 74–132-year averages in the US and UK [

20,

21]. The main reasons are: (1) changing occupant requirements, and (2) aging of building systems and equipment, which render a building’s functions obsolete long before the structure itself wears out, leading to whole-building demolition [

17,

22,

23,

24]. In China, the premature scrapping of residential buildings has resulted in enormous resource waste and carbon emissions: construction debris now accounts for about 30–40% of urban solid waste in China, yet the recycling rate of construction waste is under 10%, far below the over 90% typical in developed countries [

21,

25,

26,

27,

28]. This low resource efficiency and the prevalent demolish–rebuild cycle not only waste vast quantities of building materials but also exacerbate carbon emissions in the built environment.

To address these challenges, the field has increasingly emphasized circular design strategies centered on adaptability and longevity. In China, for example, governmental and academic initiatives promote “century-long housing” and high-quality, long-life residential development [

29,

30,

31]. Circular design strategies are now a focal pathway for reducing embodied carbon in residential buildings. A growing body of work demonstrates the mitigation potential of these circular approaches. For example, simulation results show that Design-for-Disassembly (DfD) can reduce embodied carbon by nearly half [

32,

33]. Similarly, prefabricated modular construction has been shown to cut construction-stage emissions by around 30% [

34]. The Skeleton–Infill (SI) system markedly improves adaptability and reduces waste generation over long service lives [

35]. Several case studies further validate these findings. Morales-Beltrán et al. achieved approximately a 50% reduction in embodied carbon by redesigning a traditional reinforced concrete structure into a hybrid system following DfD principles [

36]. Jang et al. found that modular prefabricated housing emits 36% less embodied carbon in material production and construction than a cast-in-situ (CIS) concrete building [

37]. Mayer et al. enhanced the reuse potential of timber wall systems by 35–47% through reversible connections [

38]. Violano et al. proposed a prototype dwelling composed of fully recoverable timber components [

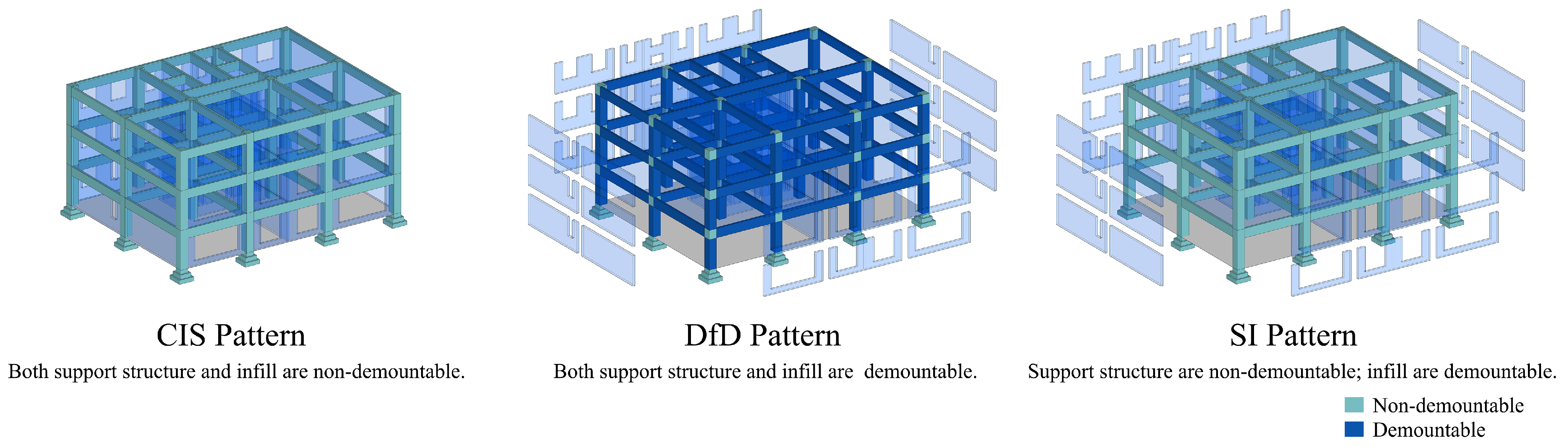

39]. Collectively, these studies indicate that circular design can deliver substantial embodied-carbon mitigation in residential buildings. At present, circular design in residential buildings has coalesced around several representative patterns. From the standpoint of cast-in-place versus prefabricated component strategies, three design patterns can be distinguished: the conventional Cast-In-Situ (CIS) pattern, the Design-for-disassembly (DfD) pattern, and the Skeleton–Infill (SI) system. These three design patterns exhibit systematic differences in underlying concepts and technical pathways: (1) CIS pattern relies on a monolithic cast-in-place structural system with rigid connections, which has poor adaptability when confronted with changing functional requirements or aging installations, often necessitating destructive demolition and rebuild, with high resource consumption and environmental impact [

19,

40]; (2) DfD pattern emphasizes reversible connections and non-destructive disassembly of building components at the design stage, so that at end-of-life components can be efficiently recovered and reused rather than discarded [

32,

41,

42,

43]. However, this approach mainly focuses on resource recycling at the demolition stage and often does not fully address spatial adaptability and functional updates during the use phase; (3) SI pattern separates a long-lived structural support frame (e.g., the load-bearing structure) from replaceable infill components (e.g., non-structural partitions), enabling flexible reconfiguration of interior space without damaging the primary structure, thereby greatly improving adaptability during use and extending the building’s overall lifespan [

44,

45]. Crucially, the “disassembly” advocated in the DfD pattern is different from the “demolition” in the CIS pattern: the former is a planned, non-destructive dismantling process aimed at component recovery and reuse, whereas the latter is an irreversible, destructive process that usually results in material waste and environmental burden. Thus, compared to the high-carbon, linear “build–use–demolish” process of the CIS pattern, both DfD and SI patterns improve resource circulation and extend building service life, thereby reducing embodied emissions. Despite these advantages, real-world adoption remains limited: globally, fewer than 1% of new buildings fully adhere to the DfD pattern [

46,

47,

48,

49], reflecting barriers such as lagging regulations, limited industry experience, and an underdeveloped supply chain support [

50].

Research gaps persist in systematically comparing life-cycle embodied carbon emissions of design patterns such as DfD and SI versus the traditional CIS pattern. The key gaps are: (1) a lack of apples-to-apples comparative studies under unified conditions. Current research has not systematically compared the embodied carbon of CIS, DfD, and SI patterns under a common baseline; especially under high-frequency renovation scenarios, the cumulative carbon divergence between a demolish–rebuild approach and a component-reuse approach has not been quantified. This gap hinders objective evaluation of the actual carbon reduction advantages of DfD and SI relative to CIS and makes it difficult to discern the differences in carbon benefits between DfD and SI. (2) A lack of long-term carbon reduction mechanism assessments from a resource-circulation perspective. Existing embodied carbon studies mostly focus on emissions from initial construction or a single end-of-life event, and do not analyze the dynamic carbon emission patterns over multiple cycles of renovation, recycling, and reuse. Particularly in China’s context of short building lifespans and frequent renewals, there is a shortage of comprehensive evaluations of the carbon offsets and cumulative emissions over long time scales (i.e., extending analysis well beyond the conventional 50-year building lifespan) resulting from material replacement and reuse. In fact, most prior studies limit the analysis to about 50 years or less; thus, it remains unclear how a significantly longer horizon (e.g., 90 years) might alter the comparative outcomes of different design approaches—an issue this study aims to address.

To bridge the above research gaps, this study quantitatively compares the embodied carbon of the three design patterns (CIS, DfD, and SI) in a typical multi-story residential building under unified conditions of building prototype, service life (90 years), and functional renovation cycle (30 years). This study fully considers resource-circulation factors such as material recycling and component reuse, aiming to identify the carbon-reduction benefits of each design pattern and to reveal the key factors influencing embodied carbon emissions. Specifically, the study focuses on the following core questions.

This question establishes a common basis for comparison by using the same building prototype, service life, and renovation schedule for all cases, eliminating confounding factors. It allows an objective “apples-to-apples” comparison of the actual differences in life-cycle embodied carbon among the CIS, DfD, and SI design patterns.

- 2.

Identify the carbon reduction mechanisms of the three design patterns from a resource-circulation perspective.

This question extends the analytical horizon to 90 years and simulates multiple renovation scenarios (in 30-year cycles) to examine the dynamic processes of material replacement, component reuse, and carbon accumulation under each design pattern. It reveals how each design pattern affects carbon emissions over a long-time scale from a resource recycling standpoint.

Through this structured research framework, this study provides quantitative evidence to address the embodied carbon problem caused by short residential lifespans and frequent rebuilds. We explicitly adopt a 90-year analysis horizon—nearly double the standard 50-year design life—to capture multiple renovation cycles and long-term effects that shorter studies would miss. The findings offer theoretical and empirical support for transitioning from the traditional linear “build–use–demolish” model toward more sustainable, circular housing design paradigms.

2. Methods

This study draws on a set of twelve prototypical residential building models developed by our research team (Harbin Institute of Technology research team) under a National Natural Science Foundation of China project. Established through adaptability and typological analyses, these models are considered representative of mainstream residential design in contemporary China. The three design patterns described above were applied to each prototype, yielding thirty-six simulated cases (12 × 3). Within the EN 15978 framework, 90-year life-cycle carbon emissions were calculated and subjected to comparative analysis. The following sections detail: the building service-life factor setting, the baseline model acquisition and grouping, and the embodied carbon calculation methods and tools.

2.1. Building Service-Life Factor Setting

We uniformly set the service life of all building cases to 90 years. This 90-year service life encompasses multiple cycles of renovation or rebuilding, allowing a more comprehensive assessment of embodied carbon differences over a long-time horizon. This extended timeframe was chosen to significantly exceed the conventional 50-year building lifespan, in line with emerging “century-long housing” objectives [

29,

30,

31], so that multiple renovation cycles and long-term impacts can be captured. It should be noted that in China’s current context, residential buildings are often demolished after around 30 years of use due to changing functional needs or aging equipment, meaning actual lifespans are far below the 50-year design lifespan [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Additionally, statistics show an average residential building lifespan of only about 25–30 years in China [

22,

55]. Based on these statistics, we introduce a 30-year interval within the 90-year period as a primary cycle for functional updates or rebuilding. This represents a typical renovation cycle for residential buildings. In our model, we assume that every 30 years the building faces functional obsolescence or equipment aging, requiring appropriate renewal measures. Each design pattern addresses this need differently.

Specifically, we consider the embodied carbon of a residential building on a given site over a total period of 90 years, with full demolition events assumed at 30-year intervals based on the typical lifespans of Chinese residential buildings. The scenario assumptions for each design pattern are as follows:

CIS (Cast-in-Situ): Utilizes an integral cast-in-situ structure with rigid, irreversible connections. When usage needs change or equipment ages, the building typically can only be dealt with by destructive demolition and complete rebuilding (shown in

Figure 1). Over a 90-year life cycle, a CIS residential building is assumed to undergo full demolition and reconstruction at year 30 and again at year 60. Each demolition is carried out destructively, and all resulting debris is treated as construction waste (accounted for with corresponding carbon emissions from waste processing). Therefore, under the CIS pattern, the building undergoes three completely new constructions and three demolitions within 90 years.

DfD (Design for Disassembly): Employs a structural system with reversible connections so that it can be taken apart non-destructively at the end of its service life (See

Figure 1). Over 90 years, a DfD residential building is assumed to require “rebuilding” at year 30 and year 60 due to functional or equipment obsolescence, but the process is carried out as non-destructive disassembly of the entire structure. The disassembled components can be recovered and reused, reducing the demand for new materials. In other words, the DfD pattern does not avoid mid-life teardown of the building, but through disassemblable design, it turns what would have been one-time disposable materials into reusable components. At the final end-of-life (year 90), the DfD building is also disassembled for component recovery, enabling the reuse of components.

SI (Skeleton-Infill): Employs a system where a long-lived structural “skeleton” is separated from easily replaceable “infill” components (Illustrated in

Figure 1). The structural support frame has a lifespan of at least 90 years (long-term use), whereas infill components have a lifespan of about 30 years and can be replaced mid-life as needed. Over 90 years, an SI residential building does not require demolition of the main structure; its functional layout can be adjusted at any time, and at years 30 and 60, only the infill components are renewed, with no full teardown or rebuilding. This means that, unlike the CIS and DfD patterns, which require rebuilding the entire structure at intervals, the SI pattern upgrades building performance in each cycle simply by replacing infill components, thus avoiding destructive demolition during the service life.

In summary, the three design patterns exhibit different characteristics over a 90-year life cycle: the CIS pattern undergoes multiple cycles of “demolition and rebuilding”, the DfD pattern undergoes multiple cycles of “disassembly and reassembly” (with component reuse), and the SI pattern features a “long-lived structure with periodic infill replacement” (shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2). These contrasting characteristics establish a clear scenario basis for the subsequent embodied carbon comparisons.

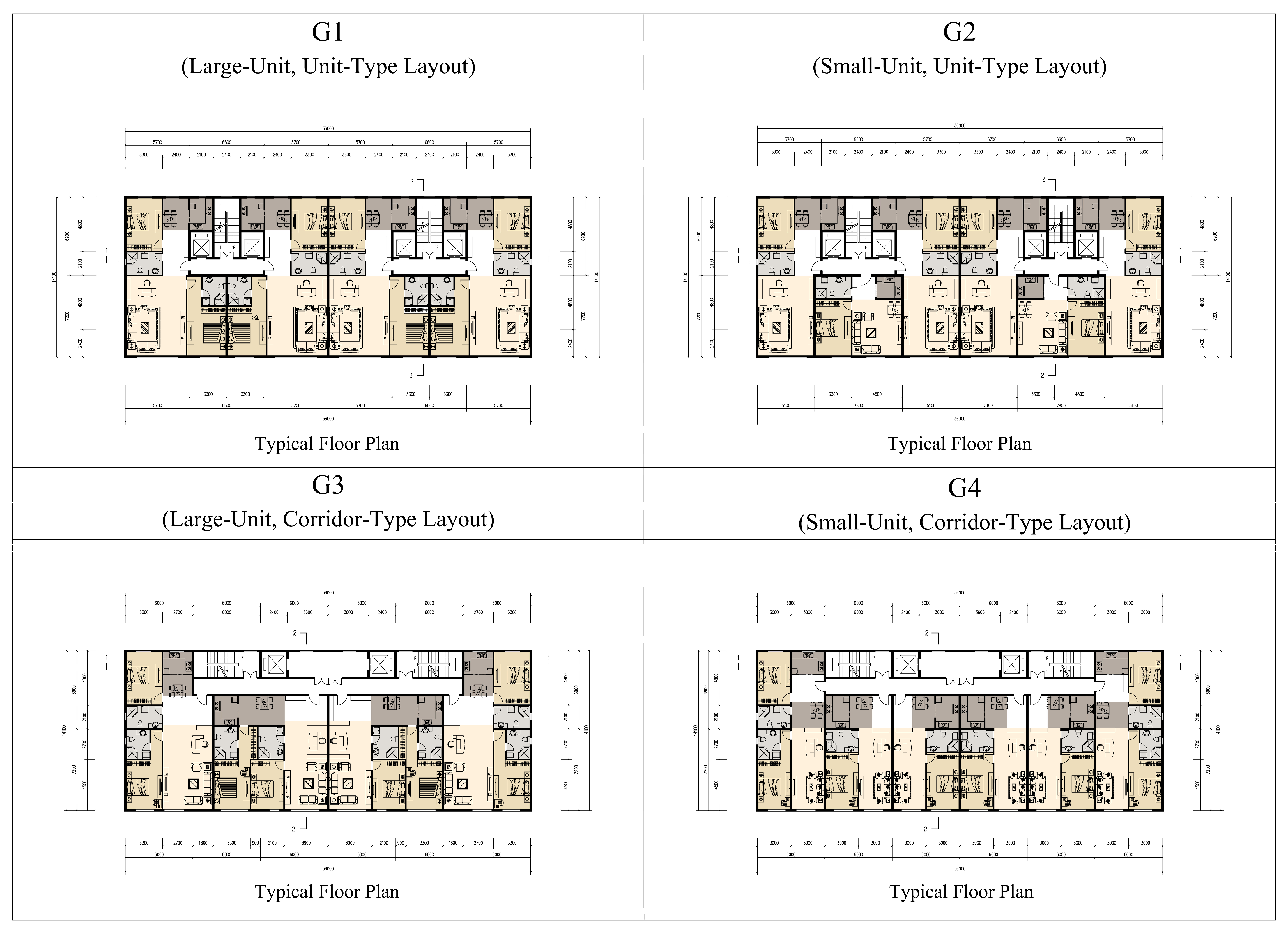

2.2. Baseline Model Acquisition and Grouping

Our residential building sample models were derived from a set of standard models developed by our research team (Harbin Institute of Technology). Between 2018 and 2022, we performed a typological analysis of 954 residential buildings (considering design adaptability and structural types) and established a library of standard models with broad representativeness. These models cover the main current forms of Chinese residential design. They combine 2 circulation layouts (unit-type vs. corridor-type) and 2 dwelling size categories (>90 m

2 vs. ≤90 m

2) to form 4 basic floor plan types; each layout type can further adopt 3 structural systems (frame, frame–shear wall, or shear wall), yielding a total of 12 distinct sample models [

56]. These sample models reflect the key variations in mainstream residential building types and spatial organization. Furthermore, to eliminate the influence of building height on the results, all samples are standardized to 20 stories with a typical floor height of 3 m. The floor plans and sections of 20-story residential buildings for these four layouts are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Specifically, based on the different combinations of the 4 layout types and 3 structural types, the models are organized into 4 primary groups by layout (G1, G2, G3, G4). Combining each layout with the 3 structure options produces a comprehensive 4 × 3 matrix of samples (4 layout types × 3 structures), consisting of 12 clearly distinguished subgroups:

G1 (Large-Unit, Unit-Type Layout): Dwelling unit area > 90 m2, unit-type (one stair core serving two units per floor), standard floor area ~441.72 m2. This group includes 3 structural variants: G1-F (frame), G1-FS (frame–shear wall), and G1-S (shear wall).

G2 (Small-Unit, Unit-Type Layout): Dwelling unit area ≤ 90 m2, unit-type (one stair core serving three units per floor), standard floor area ~441.72 m2. Structural variants include G2-F (frame), G2-FS (frame–shear wall), and G2-S (shear wall).

G3 (Large-Unit, Corridor-Type Layout): Dwelling unit area > 90 m2, corridor-type (one stair core serving four units per floor), standard floor area ~414.00 m2. Structural variants include G3-F (frame), G3-FS (frame–shear wall), and G3-S (shear wall).

G4 (Small-Unit, Corridor-Type Layout): Dwelling unit area ≤ 90 m2, corridor-type (one stair core serving six units per floor), standard floor area ~414.00 m2. Structural variants include G4-F (frame), G4-FS (frame–shear wall), and G4-S (shear wall).

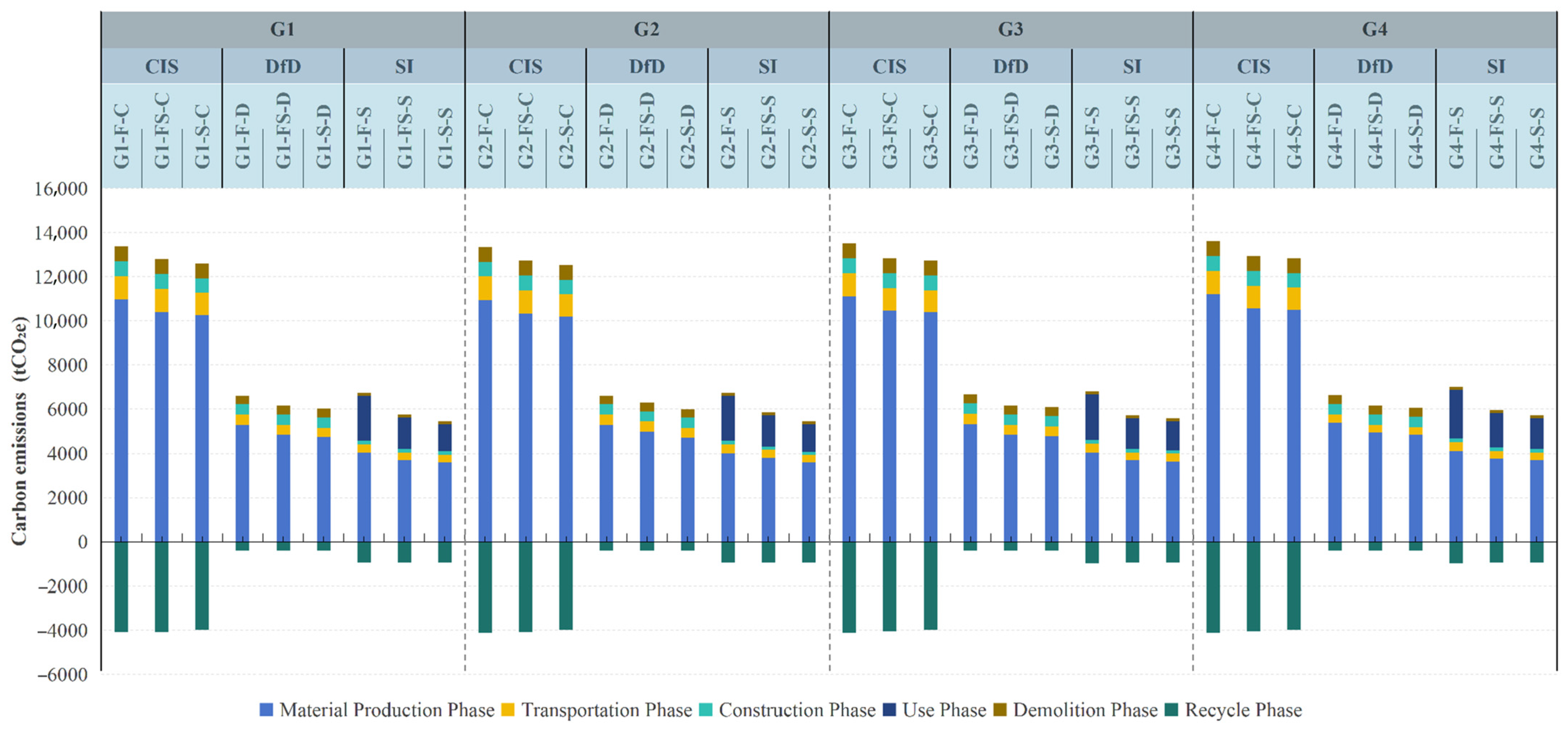

On this foundation, to study the impact of design patterns on embodied carbon emissions, we applied each of the 3 design patterns (CIS, DfD, SI) to every subgroup model. In this way, each subgroup produces 3 different design pattern schemes, and the 12 subgroups yield a total of 36 independent simulated cases (each case designated with a unique code, see

Figure 5). Through this layered grouping experimental design, the study covers a diverse range of residential types and design patterns. This fine-grained classification effectively captures the important differences among unit layout, structural system, and design pattern, providing a solid foundation for a detailed comparison of embodied carbon emissions across the schemes.

2.3. Embodied Carbon Calculation and Tools

This study calculated embodied carbon emissions for each case following the EN 15978:2011 standard [

57]. The assessment boundary covers the product phase (A1–A3), construction phase (A4–A5), use phase (B1–B5, excluding B6 and B7), end-of-life phase (C1–C4), and beyond life-cycle phase (D, representing the carbon benefits from material recycling and reuse), ensuring consistent and reliable data sources [

58,

59,

60,

61].

Figure 6 illustrates the life-cycle boundary definitions according to EN 15978. Note that since this study focuses on embodied carbon, operational carbon during the use phase (e.g., HVAC energy use) is not included; however, component maintenance and replacement activities during use are included in the B-phase embodied carbon calculations. In terms of calculation method, we adopted the standard emissions factor approach in line with EN 15978 requirements. All life-cycle phase calculations conform to the EN 15978 specifications. The material carbon emission factors are mainly derived from the Chinese national standard Calculation Standard for Building Carbon Emissions (GB/T 51366–2019) [

62]; likewise, carbon emission parameters for phases such as transportation and construction were taken from the recommended values in that standard to ensure data consistency and reliability.

We employed PKPM Green Building Design (PKPM-BES, version 2024) and BIM Base KIT2025 to carry out the simulations. These tools were used to extract the quantities of all structural, enveloped, and non-structural materials. The complete calculation workflow is documented in the

Supplementary Materials, where the input spreadsheets and calculation formulas are provided to ensure full reproducibility of the embodied-carbon results. Because current software tools do not yet fully support the modeling of component reuse and replacement processes under circular design scenarios, we complemented the simulations with formula-based calculations to quantify the full life-cycle embodied carbon of the residential buildings. In practice, PKPM was used to perform the primary building carbon simulations, while additional calculations were implemented to account for embodied carbon emissions associated with different component service lives and replacement frequencies. This hybrid workflow enhances data accuracy and enables fine-grained, robust comparisons between the different design patterns.

PKPM-BES offers the following advantages: (1) leveraging BIM integration, it can automatically extract quantities of key structural and envelope materials, reducing manual calculation errors; (2) it supports a carbon factor database based on Chinese standards (e.g., GB/T 51366–2019), facilitating direct alignment with our life-cycle accounting framework. However, PKPM’s functionality is limited in areas such as modeling component reuse and reversible connections, making it difficult to directly capture the component-recycling features of DfD and SI. Thus, we combined PKPM with supplementary calculations to evaluate carbon emissions during component reuse and replacement stages. Specifically, for components that are reused (in DfD cases), we applied a carbon credit equal to the emissions that would have been generated to produce an equivalent new component (avoided emissions), and for infill components that are periodically replaced (in SI cases), we added the embodied carbon of new materials for each replacement cycle. These supplementary calculations follow EN 15978 principles, ensuring that the benefits of component reuse and the impacts of infill replacements are appropriately captured in the life-cycle assessment. For the modular design and component optimization aspects of the DfD and SI cases, we also employed BIM Base KIT2025. This platform excels in prefabricated and modular building design, with strengths mainly in: (1) high-precision BIM-based modeling and 3D visualization of components, accurately depicting the separated structure of the support frame vs. infill system; (2) seamless data integration with PKPM and other mainstream design/analysis software, enabling direct transfer of component information and material properties without redundant modeling or data loss.

In this study, the modular designs for the DfD and SI pattern buildings were first completed in BIM Base KIT2025, and the generated component and material data were directly imported into the PKPM platform to carry out precise life-cycle embodied carbon calculations. Through this integrated approach—combining PKPM’s design and analytical capabilities with BIM Base KIT2025′s modular modeling—we established a complete, accurate, and traceable component data chain at the design simulation stage, providing a robust data foundation for subsequent evaluation of carbon emissions from component replacement and reuse.

2.4. Assumptions and Parameter Settings

To ensure full transparency and consistency, we summarize here all key parameters and assumptions for the LCA.

Table 2 lists the base values, assumed ranges, and data sources for parameters used in each life-cycle phase (A1–A5, B1–B5, C1–C4, D). For example, a reference service life of 90 years (range 70–110 years) was used, with renovation intervals of 30 years (range 25–35 years), following EN 15978 guidelines and Chinese practice. We include all structural and non-structural elements (e.g., primary frame, infill partitions, finishes) in the inventory for every case. The use-phase (B1–B5) incorporates scheduled maintenance: non-structural partitions and finishes are replaced at each renovation, and major MEP systems (HVAC, plumbing) are replaced every 30 years, uniformly across CIS, DfD, and SI cases. Importantly, all three design patterns use identical structural layouts: we kept the same spans, column grid, and design loads for CIS, DfD, and SI variants of each prototype, ensuring structural components have the same dimensions and materials. Any additional materials required for DfD connectors or SI skeletons have been accounted for. For instance, specialized DfD connectors (bolts, brackets) were assumed to use an equivalent steel tonnage as conventional welded connections.

We also performed a one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis on these parameters.

Table 3 (below) shows the effect on total CO

2e of varying each parameter for a representative case (Group G1, frame structure, CIS). The results indicate that service life and renovation interval have the largest impact (changes of ~−14% to +20%), while factors like the recycling rate and transport distance produce only minor variations.

5. Conclusions

Under a unified set of assumptions (a 90-year service life with 30-year renovation cycles), this study systematically quantified and compared the life-cycle embodied carbon emissions of three design patterns (CIS, DfD, and SI) in a typical multi-story residential building. The analysis revealed the carbon-reduction benefits and mechanisms of each design pattern under scenarios of frequent renovation, confirming the significant long-term carbon mitigation potential of the DfD and SI patterns. This work helps to fill the gap in existing research, which has lacked long-term, equivalent comparisons of these three design patterns. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

From a resource-circulation standpoint, three factors—material intensity, service life, and end-of-life management—govern embodied-carbon outcomes. In our cases, the material-production phase contributes more than 80% of total embodied carbon and thus remains the largest single source of emissions. Extending service life and achieving high recovery/reuse rates can reduce embodied carbon by approximately 40–55% and 15–25%, respectively, underscoring the necessity of integrating circularity strategies at the design stage.

Through a multi-scenario, multi-factor quantitative comparison, this study substantiates the pronounced long-term environmental advantages of SI and DfD patterns for residential buildings, providing theoretical grounding and empirical evidence to support the promotion of adaptable, long-lived, and low-carbon housing.