Workplace Stress Among Construction Professionals: The Influence of Demographic and Institutional Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Stressors Among Construction Professionals

2.1.1. Organizational and Interpersonal Stress Factors

2.1.2. Task-Related Stressors

2.1.3. Physical Stressors

3. Method and Data

3.1. Design of the Questionnaire Survey

3.2. Data Collection

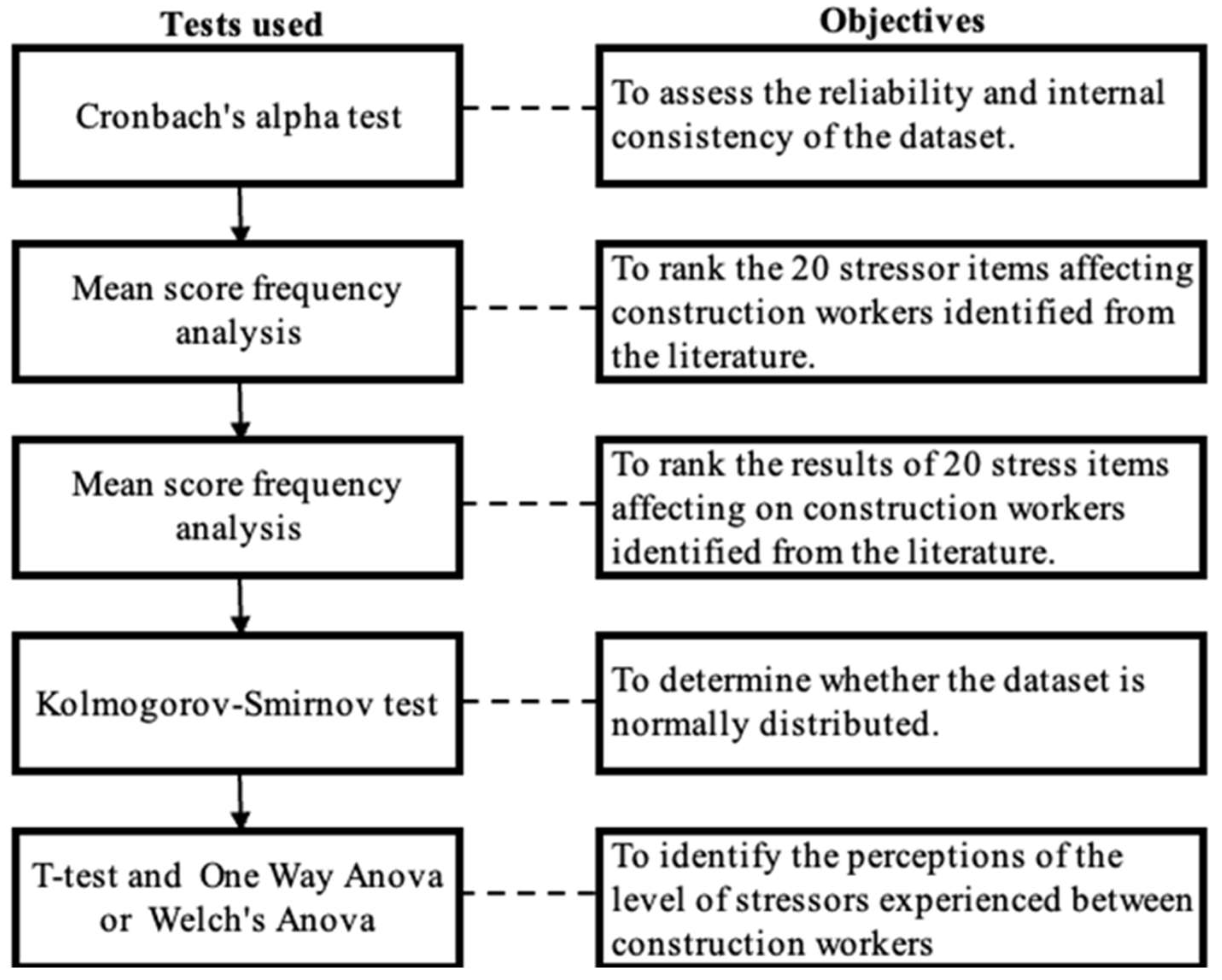

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Stressors in the Construction Industry

4.3. Differences in Perceptions Across Demographic and Workplace Contexts

4.4. Effects of Workplace Stressors on Private Lives of Employees

5. Discussion

6. Limitation and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gundes, S. Exploring the dynamics of the Turkish construction industry using input–output analysis. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundes, S. Input structure of the construction industry: A cross-country analysis, 1968–1990. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A systematic review of mental stressors in the construction industry. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick, J.; Rogers, K.; Corbett, E.; Binch, S.; Jackson, K. An Analysis of the Prevalence and Distribution of Stress in the Construction Industry; Health and Safety Executive: Buxton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Love, P.E.; Edwards, D.J.; Irani, Z. Work stress, support, and mental health in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Shan Isabelle Chan, Y.; Dongyu, C. Structural linear relationships between job stress, burnout, physiological stress, and performance of construction project managers. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2011, 18, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Edwards, P.; Lingard, H. Workplace stress experienced by construction professionals in South Africa. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Naslund, J.A. Measures to improve the mental health of construction personnel based on expert opinions. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Zhang, H.; Skitmore, M. Effects of organizational supports on the stress of construction estimation participants. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschman, J.S.; Van der Molen, H.F.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Psychosocial work environment and mental health among construction workers. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mohd-Rahim, F.A.; Chan, Y.Y.; Abdul-Rahman, H. Fuzzy mapping on psychological disorders in construction management. J. Constr. Eng. Manage 2017, 143, 04016094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, O.; Loosemore, M.; Fini, A.A.F. Construction workforce’s mental health: Research and policy alignment in the Australian construction industry. Buildings 2023, 13, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordjour, G.A.; Chan, A.P. Exploring occupational psychological health indicators among construction employees: A study in Ghana. J. Ment. Health Clin. Psychol. 2019, 3, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selcuk, E.; Gundes, S. İnşaat Projelerinde Verimlilik Performansını Etkileyen Faktörler. In Proceedings of the 2. Proje ve Yapım Yönetimi Kongresi, İzmir, Turkey, 13–16 September 2012; pp. 1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Avcı, M.; Selçuk, E. Türkiye’de İnşaat Projelerinde Çalışanların İşçi Sağlığı ve Güvenliği Tutumlarının Değerlendirilmesi. Haliç Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Derg. 2020, 3, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, H.; Serbaya, S.H.; Rizwan, A.; Saleem, M.; Maleh, Y.; Alamgir, Z. Impact of emotional intelligence on the stress and safety of construction workers in Saudi Arabia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, S. Importance of testing with independent subjects and contexts for machine-learning models to monitor construction workers’ psychophysiological responses. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Leung, M.Y.; Ojo, L.D. An exploratory study to identify key stressors of ethnic minority workers in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental ill-health risk factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yang, W.; Liu, T.; Xia, F. Demographic influences on perceived stressors of construction workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, P.; Ye, G.; Zhao, D. Risk-compensation behaviors on construction sites: Demographic and psychological determinants. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 04017008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Salgado, C.; Camacho-Vega, J.C.; Gomez-Salgado, J.; Garcia-Iglesias, J.J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Allande-Cusso, R.; Martín-Pereira, J.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Stress, fear, and anxiety among construction workers: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1226914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, A.A.; Galindo, E.; Reschke, K.; Bidzan, M.; Stueck, M. Editorial: The interplay of stress, health, and well-being: Unraveling the psychological and physiological processes. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1471084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekra, K.A.; Perera, B.A.K.S. Defining occupational stress: A systematic literature review. FARU J. 2023, 10, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSE. Health and Safety Executive. Tackling Work-Related Stress Using the Management Standards Approach. 2019. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/wbk01.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Colligan, T.W.; Higgins, E.M. Workplace stress: Etiology and consequences. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2006, 21, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J. Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress with health: A systematic review of evidence on the effort-reward imbalance model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebarni, R. The impact of stress in site management effectiveness. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1996, 14, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. The impact of individual and job characteristics on ‘burnout’ among civil engineers in Australia and the implications for employee turnover. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2003, 21, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.; Samanmali, R.; De Silva, H.L. Managing occupational stress of professionals in large construction projects. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Akinyemi, T.A. Conceptualizing the dynamics of mental health among construction supervisors. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2593–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Ahmed, K.; Chan, I.Y. Impact of Stressors/Stress on Organizational Commitment of Engineers in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V.; Turner, M. The rhythms of project life: A longitudinal analysis of work hours and work–life experiences in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebelli, H.; Choi, B.; Lee, S. Application of wearable biosensors to construction sites. II: Assessing workers’ physical demand. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, T.S.; Everett, J.G. Physiological demands during construction work. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2002, 128, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, S. Wristband-type wearable health devices to measure construction workers’ physical demands. Autom. Constr. 2017, 83, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, K.J.C.; Dainty, A.R.J.; Ison, S.G. Gender: A risk factor for occupational stress in the architectural profession? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.H. Once, twice, or three times as harmful? Ethnic harassment, gender harassment, and generalized workplace harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Kamardeen, I. Work stress is a threat to gender diversity in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Peihua Zhang, R.; Edwards, P. An investigation of work-related strain effects and coping mechanisms among South African construction professionals. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 298–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K.; Patanakul, P.; Pinto, M.B. Project personnel, job demands, and workplace burnout: The differential effects of job title and project type. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2016, 63, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Li, X.; Yang, F. Stressors and job burnout of Chinese expatriate construction professionals. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, J. Role stress, job burnout, and job performance in construction project managers: The moderating role of career calling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Imran, H.; Lewis, P.; Zhai, D. Investigating the latent factors of quality of work-life affecting construction craft worker job satisfaction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04016134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Waters, T. Gender differences in occupational stress among professionals in the construction industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2004, 20, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitharana, V.H.P.; De Silva, G.S.; De Silva, S. Health hazards, risk and safety practices in construction sites–a review study. Eng. J. Inst. Eng. Sri Lanka 2015, 48, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A., Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, K.J.; Ison, S.G.; Dainty, A.R. The job satisfaction of UK architects and relationships with work-life balance and turnover intentions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2009, 16, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, N.S.; Love, P.E. Psychological adjustment and coping among construction project managers. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Edwards, P.; Lingard, H.; Cattell, K. Predictive modeling of workplace stress among construction professionals. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 04013055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, J.; Loganathan, S.; Kamalanabhan, T.J.; Kalidindi, S.N. Investigating the relationship between occupational stress and work-life balance among Indian construction professionals. Constr. Econ. Build. 2022, 22, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Chan, Y.S.; Yu, J. Integrated model for the stressors and stresses of construction project managers in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Liang, Q.; Chan, I.Y. Development of a stressors–stress–performance–outcome model for expatriate construction professionals. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04016121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, P.J.; Hrymak, V.; Bruce, C.; Byrne, J. The role of interpersonal conflict as a cause of work-related stress in construction managers in Ireland. Constr. Innov. 2025, 25, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.S. Definition and conceptualization of stress in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1980, 25, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Boadu, E.F.; Dansoh, A.; Fagbenro, R.K. Coping with psychosocial hazards: A systematic review of young construction workers’ practices and their determinants. Buildings 2023, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hon, C.K.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B.; Wu, P.P.Y. A Bayesian network model for the impacts of psychosocial hazards on the mental health of site-based construction practitioners. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04022184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caven, V. Constructing a career: Women architects at work. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.; Sun, C.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B.; Biggs, H.C. Psychosocial hazards affecting mental health in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 3165–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. Does work–family conflict mediate the relationship between job schedule demands and burnout in male construction professionals and managers? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2005, 23, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Lingard, H. Identification and verification of demands and resources within a work–life fit framework: Evidence from the Australian construction industry. Community Work Fam. 2014, 17, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Odagiri, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimomitsu, T.; Theorell, T.; Inoue, S. Association of overtime work hours with various stress responses in 59,021 Japanese workers: Retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas, B.; Izci, F.B. Individual and workplace factors related to fatal occupational accidents among shipyard workers in Turkey. Saf. Sci. 2018, 101, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, W.; Yu, Y.; Antwi Afari, M.F. Quantifying the effect of mental stress on physical stress for construction tasks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.J.; Jee, N.Y. Analyzing safety behaviors of temporary construction workers using structural equation modeling. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, K.; Bowen, P.; Edwards, P. Stress among South African construction professionals: A job demand-control-support survey. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2016, 34, 700–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, R.R.; Sawang, S. Construction workers’ well-being: What leads to depression, anxiety, and stress? J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T.; Giggins, H.; Ranasinghe, U. A critical analysis of risk factors and strategies to improve mental health issues of construction workers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotimi, F.E.; Burfoot, M.; Naismith, N.; Mohaghegh, M.; Brauner, M. A systematic review of the mental health of women in construction: Future research directions. Build. Res. Inf. 2023, 51, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Loosemore, M. The influence of personal and workplace characteristics on the job stressors of design professionals in the Chinese construction industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 05023006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M. Job stress and burnout among construction professionals: The moderating role of online emotions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4831–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.H.; Senaratne, S.; Fu, Y.; Tijani, B. Tackling stress of project management practitioners in the Australian construction industry: The causes, effects and alleviation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4016–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A.; Townsend, K.; Loudoun, R.; Robertson, A.; Mason, J.; Maple, M.; Lacey, J.; Thompson, N. Towards an Evidence-Based Critical Incidents and Suicides Response Program in Australian Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firose, M.M.; Chathurangi, B.N.M.; Kamardeen, I. Work stress among construction professionals during an economic crisis: A case study of Sri Lanka. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2025. Ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademci, E.; Gundes, S. Individual and Organisational Level Drivers and Barriers to Building Information Modelling (BIM). J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 26, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk, E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on construction project performance: Challenges and strategic responses. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakul, N.; Gundes, S. Capital Structure in the Construction Industry: Theory and Practice. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 48, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S.; Rasagopalasingam, V. The causes and effects of work stress in construction project managers: The case in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2017, 17, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 2017, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aalderen-Smeets, S.; Walma van der Molen, J. Measuring primary teachers’ attitudes toward teaching science: Development of the dimensions of attitude toward science (DAS) instrument. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Gossop, M.; Powis, B.; Strang, J. Reaching hidden populations of drug users by privileged access interviewers: Methodological and practical issues. Addiction 1993, 88, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 update; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter, F.; Wallnau, L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Wadsworth: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.M.; Donnelly, J.P. The Research Methods Knowledge Base; Atomic Dog: Mason, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Methodology in the Social Sciences: Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, E.; Çelik, İ.; Urlu, S. Araştırmalarda Uygun İstatistiksel Tekniğin Belirlenmesinde Normallik ve Homojenlik İhlallerinin Etkisinin İlgili Literatür Bağlamında Değerlendirilmesi. J. Psychom. Res. 2024, 2, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Pironti, M.; Quaglia, R. AI in knowledge sharing, which ethical challenges are raised in decision-making processes for organisations? Manag. Decis. 2024, 63, 3369–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainani, K.L. Dealing with non-normal data. PMR 2012, 4, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Sharma, S.C. Robustness to nonnormality of regression Ftests. J. Econom. 1996, 71, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Watson, G.S. Robustness to non-normality of regression tests. Biometrika 1962, 49, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Knief, U.; Forstmeier, W. Violating the normality assumption may be the lesser of two evils. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 2576–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jekel, J.F.; Katz, D.L.; Elmore, J.G. Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Preventive Medicine; W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach, D.G.; Wang, H.; Bendoly, E.; Zhang, S. Importance of organizational citizenship behaviour for overall performance evaluation: Comparing the role of task interdependence in China and the USA. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2007, 3, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 2020; Available online: https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CxUsEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=n38AvGCe4V&sig=2HibIDC6bl2YuTKsNInrn4I3nos&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Staffa, S.J.; Zurakowski, D. Strategies in adjusting for multiple comparisons: A primer for pediatric surgeons. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moder, K. Alternatives to F-test in one way ANOVA in case of heterogeneity of variances (a simulation study). Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2010, 52, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Marcial, D.; Launer, M. Test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the survey questionnaire on digital trust in the workplace. Solid State Technol. 2021, 64, 4369–4381. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium Sized Enterprises; 2003/361/EC; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- Tsubono, K.; Mitoku, S. Public school teachers’ occupational stress across different school types: A nationwide survey during the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1287893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Saridakis, G.; Blackburn, R. Job stress in the United Kingdom: Are small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises different? Stress Health 2015, 31, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, N.; Smeeton, N.; Freethy, I.; Jones, J.; Wills, W.; Dennington-Price, A.; Jackson, J.; Brown, K. Workplace health and wellbeing in small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs): A mixed methods evaluation of provision and support uptake. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, M.; Boß, L.; Engels, J.; Kuhlmann, R.; Kuske, J.; Lepper, S.; Lesener, L.; Pavlista, V.; Diebig, M.; Lunau, T.; et al. Facilitating stress prevention in micro and small-sized enterprises: Protocol for a mixed method study to evaluate the effectiveness and implementation process of targeted web-based interventions. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, J.; Odawara, M.; Takahashi, H.; Fujimori, M.; Yaguchi-Saito, A.; Inoue, M.; Uchitomi, Y.; Shimazu, T. Barriers and facilitative factors in the implementation of workplace health promotion activities in small and medium-sized enterprises: A qualitative study. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.H. Allowed into a man’s world’meanings of work–life balance: Perspectives of women civil engineers as ‘minority’workers in construction. Gend. Work Organ. 2009, 16, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, M.; Li, H.X.; Hasan, A.; Ahmadian Fard Fini, A. Gender inequality and challenges of women in the construction industry: An evidenced-based analysis from China. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Lin, J. Effect of company size on occupational health and safety. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2004, 4, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, K.; Ando, H.; Eguchi, H.; Tsuji, M.; Tateishi, S.; Mori, K.; Ogami, A. Relationship among work–treatment balance, job stress, and work engagement in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Ind. Health 2022, 61, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stressor Factors Groups | Survey Questions | Supporting Literature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love et al. [5] | Leung et al. [6] | Bowen et al. [7] | Boschman et al. [10] | Hosseini et al. [12] | Alsulami et al. [16] | Ahmed et al. [18] | Chan et al. [19] | De Silva et al. [30] | Nwaogu et al. [31] | Jebelli et al. [34] | Sunindijo and Kamardeen [39] | Bowen et al. [40] | Abdalla et al. [42] | Shan et al. [44] | Loosemore and Waters [45] | Vitharana et al. [46] | Haynes and Love [49] | Manivannan et al. [51] | Leung et al. [52] | Leung et al. [53] | Schuler [55] | Seo HeeChang et al. [65] | Cattell et al. [66] | Langdon and Sawang [67] | Newaz et al. [68] | Rotimi et al. [69] | Zhang et al. [70] | Wu et al. [71] | Jin et al. [72] | Biggs et al. [73] | Firose et al. [74] | ||

| Organisational/ Interpersonal Stressors | SF15—Violence at work (threat, assault, etc.) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF18—Harrasment/Bullying | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF13—Acts of personal disrespect at work | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF12—Conflicts/poor relationships with coworkers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| SF17—Gender discrimination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF14—Insufficient encouragement/support from manager | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF16—Age discrimination | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF20—Facing obstacles when my views differ from coworkers. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF6—Little development/learning opportunities at work | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Task Stressors | SF3—High job demands/responsibility | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| SF8—Excessive workload | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| SF4—High level of time pressure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| SF7—Unclear job scope and responsibility | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| SF10—High level of client’s demands and requirements | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF11—Fear of failure at the job/job insecurity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| SF19—Taking on tasks due to others’ negligence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF1—Long working hours (overtime) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| SF2—Uncertainty in working hours (irregular work schedule) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical Stressors | SF9—Inadequate occupational health and safety measures at the workplace | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF5—Poor physical working conditions (noise, crowd etc.) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Quartile | Mean Score Scale (1–5) | Quartile Ranges of Averages | Levels of Impact of Expressions | Likert Scale Response Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Quartile | Mean < 3.16 | Min:2.82; Q1:3.16 | Low impact statement scores | (1) Not Effective at All (2) Slightly Effective (3) Neutral |

| Middle Half Quartile | Mean = 3.16–3.83 | Median:3.43 | Moderately effective expression ratings | (3) Neutral (4) Effective to some extent |

| Upper Quartile | Mean > 3.83 | Q3:3.83; Max:4.23 | Most effective expression ratings | (4) Effective to some extent (5) Most Effective |

| General Information | No. of Samples | % of Total Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 111 | 60 |

| Female | 74 | 40 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 94 | 50.80 |

| Single | 91 | 49.20 |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 60 | 32.43 |

| 30–39 | 82 | 44.32 |

| 40 and above | 43 | 23.25 |

| Position in the company | ||

| Senior management | 77 | 41.60 |

| Technical Operational Management | 32 | 17.30 |

| Design and support | 76 | 41.10 |

| Number of employees | ||

| 1–49 | 89 | 48.10 |

| 50–249 | 51 | 27.60 |

| 250 or more | 45 | 24.30 |

| Years of experience | ||

| 1–5 years | 66 | 35.70 |

| 6–10 years | 38 | 20.50 |

| 11–15 years | 30 | 16.20 |

| 16–20 years | 19 | 10.30 |

| 21–25 years | 10 | 5.40 |

| 26 years and above | 22 | 11.90 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 | 105 | 56.80 |

| 1 | 41 | 22.20 |

| 2 | 32 | 17.30 |

| 3 and above | 7 | 3.80 |

| Place of work | ||

| Construction site | 21 | 11.40 |

| Office | 92 | 49.70 |

| Both construction site and office | 72 | 38.90 |

| Weekly working hours | ||

| 0–20 h | 6 | 3.20 |

| 21–20 h | 14 | 7.60 |

| 31–40 h | 29 | 15.70 |

| 41–50 h | 87 | 47.00 |

| 51–60 h | 32 | 17.30 |

| 60 h and above | 17 | 9.20 |

| Item No. | Items | Frequency of Responses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | S.D | Ranking | Quartile Grouping | |||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |||||||

| SF4 | T | High level of time pressure | 1.10 | 4.86 | 15.67 | 25.94 | 52.43 | 4.23 | 0.959 | 1 | Upper Quartile Category |

| SF3 | T | High job demands/responsibility | 2.17 | 5.95 | 10.81 | 29.72 | 51.35 | 4.22 | 1.005 | 2 | |

| SF8 | T | Excessive workload | 6.49 | 6.49 | 11.89 | 30.81 | 44.32 | 4.00 | 1.188 | 3 | |

| SF7 | T | Unclear job scope and responsibility | 4.33 | 9.19 | 12.97 | 31.35 | 42.16 | 3.97 | 1.146 | 4 | |

| SF1 | T | Long working hours (overtime) | 4.87 | 11.89 | 10.82 | 36.75 | 35.67 | 3.86 | 1.169 | 5 | |

| SF2 | T | Uncertainty in working hours (irregular work schedule) | 5.95 | 11.35 | 17.30 | 25.40 | 40.00 | 3.82 | 1.240 | 6 | Middle Half Category |

| SF19 | T | Taking on tasks due to others’ negligence | 3.25 | 12.98 | 15.68 | 37.28 | 30.81 | 3.79 | 1.113 | 7 | |

| SF14 | O/I | Insufficient encouragement/support from managers | 7.03 | 7.03 | 27.03 | 26.48 | 32.43 | 3.70 | 1.194 | 8 | |

| SF10 | T | High level of client’s demands and requirements | 5.95 | 18.92 | 12.97 | 27.02 | 35.14 | 3.66 | 1.292 | 9 | |

| SF5 | P | Poor physical working conditions (noise, crowd, etc.) | 10.27 | 14.60 | 21.62 | 25.40 | 28.11 | 3.46 | 1.314 | 10 | |

| SF6 | O/I | Little development/learning opportunities at work | 10.27 | 14.60 | 23.24 | 27.57 | 24.32 | 3.41 | 1.282 | 11 | |

| SF13 | O/I | Acts of personal disrespect at work | 17.84 | 10.27 | 15.68 | 24.86 | 31.35 | 3.41 | 1.468 | 12 | |

| SF11 | T | Fear of failure at the job/job insecurity | 10.80 | 19.46 | 18.92 | 25.41 | 25.41 | 3.35 | 1.335 | 13 | |

| SF9 | P | Inadequate occupational health and safety measures at the workplace | 18.92 | 13.51 | 17.85 | 22.70 | 27.02 | 3.25 | 1.465 | 14 | |

| SF12 | O/I | Conflicts/poor relationships with coworkers | 17.85 | 14.60 | 25.40 | 15.67 | 26.48 | 3.18 | 1.432 | 15 | |

| SF20 | O/I | Facing obstacles when my views differ from coworkers | 22.16 | 8.11 | 23.24 | 30.81 | 15.68 | 3.09 | 1.379 | 16 | Lower Quartile Category |

| SF15 | O/I | Violence at work (threat, assault, etc.) | 27.57 | 10.81 | 18.92 | 10.81 | 31.89 | 3.08 | 1.612 | 17 | |

| SF17 | O/I | Gender discrimination (Discrimination in promotion and development opportunities at work) | 28.11 | 9.19 | 21.08 | 15.13 | 26.49 | 3.02 | 1.561 | 18 | |

| SF16 | O/I | Age discrimination (Discrimination in promotion and development opportunities at work) | 23.24 | 12.97 | 23.25 | 20.00 | 20.54 | 3.01 | 1.446 | 19 | |

| SF18 | O/I | Harassment/Bullying | 34.05 | 11.89 | 17.84 | 9.73 | 26.49 | 2.82 | 1.619 | 20 | |

| Stress Factors | Independent Samples | One Way Anova/Welch ANOVA Test | Number of Significant Differences | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Test | |||||||||||||

| Gender | Marital Status | Age | Position | Number of Employees | Experience | Place of Work | |||||||

| Anova | Welch | Anova | Welch | Anova | Welch | Anova | Welch | Anova | Welch | ||||

| SF15. Violence at work (threat, assault, etc.) | 0.075 | 0.098 | 0.331 | 0.352 | 0.026 * | 0.624 | 0.113 | 1 | |||||

| SF18. Harassment/Bullying | 0.034 * | 0.005 ** | 0.265 | 0.730 | 0.080 | 0.004 ** | 0.069 | 3 | |||||

| SF13. Acts of personal disrespect at work | 0.023 * | 0.044 * | 0.671 | 0.698 | 0.779 | 0.546 | 0.006 ** | 3 | |||||

| SF12. Conflicts/poor relationships with coworkers | 0.014 * | 0.342 | 0.631 | 0.522 | 0.797 | 0.703 | 0.000 ** | 2 | |||||

| SF17. Gender discrimination | 0.000 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.137 | 0.193 | 0.147 | 0.152 | 0.349 | 2 | |||||

| SF9. Inadequate H&S | 0.034 * | 0.028 * | 0.324 | 0.151 | 0.031 * | 0.004 ** | 0.001 ** | 5 | |||||

| SF16. Age discrimination | 0.002 ** | 0.170 | 0.587 | 0.247 | 0.553 | 0.632 | 0.013 * | 2 | |||||

| SF20. Facing obstacles when my views differ from coworkers | 0.729 | 0.387 | 0.949 | 0.848 | 0.777 | 0.557 | 0.061 | 0 | |||||

| SF6. Little development/learning opportunities at work | 0.263 | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.028 * | 0.008 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.110 | 5 | |||||

| SF3. High job demands/responsibility | 0.835 | 0.026 * | 0.619 | 0.216 | 0.006 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.404 | 3 | |||||

| SF8. Excessive workload | 0.130 | 0.806 | 0.647 | 0.485 | 0.035 * | 0.000 ** | 0.670 | 2 | |||||

| SF4. High level of time pressure | 0.400 | 0.389 | 0.947 | 0.496 | 0.404 | 0.002 ** | 0.001 ** | 2 | |||||

| SF7. Unclear job scope and responsibility | 0.835 | 0.997 | 0.381 | 0.822 | 0.001 ** | 0.469 | 0.532 | 1 | |||||

| SF10. High level of client’s demands and requirements | 0.138 | 0.460 | 0.766 | 0.026 * | 0.003 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.025 * | 4 | |||||

| SF11. Fear of failure at the job/job insecurity | 0.007 ** | 0.378 | 0.109 | 0.456 | 0.061 | 0.020 * | 0.005 ** | 3 | |||||

| SF19. Taking on tasks due to others’ negligence | 0.566 | 0.968 | 0.594 | 0.312 | 0.912 | 0.339 | 0.015 * | 1 | |||||

| SF14. Insufficient encouragement/support from managers | 0.007 ** | 0.266 | 0.984 | 0.048 * | 0.122 | 0.020 * | 0.027 * | 4 | |||||

| SF1. Long working hours | 0.427 | 0.095 | 0.001 ** | 0.538 | 0.001 ** | 0.142 | 0.563 | 2 | |||||

| SF2. Uncertainty in working hours (irregular work schedule) | 0.981 | 0.301 | 0.009 ** | 0.023 * | 0.030 * | 0.002 ** | 0.559 | 4 | |||||

| SF5. Poor physical working conditions (noise, crowd, etc.) | 0.096 | 0.005 ** | 0.028 * | 0.415 | 0.360 | 0.183 | 0.514 | 2 | |||||

| Mean Score Analysis Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of Stress Factors Encountered at the Workplace | Mean Average | Mean Score | S.D. | Rank |

| Effects of stress factors on mental health | 3.08 | |||

| 21. Minor physical discomforts (bodily pain, headaches, neck pain, or other aches, etc.) | 3.80 | 1.13 | 7 | |

| 22. Occupational injuries | 3.23 | 1.416 | 12 | |

| 23. Desire to leave profession/career change | 3.30 | 1.309 | 11 | |

| 24. Anxiety and depression | 3.44 | 1.366 | 10 | |

| 25. Burnout syndrome | 3.60 | 1.383 | 8 | |

| 26. Sleep disturbances (difficulty falling asleep, poor sleep quality) | 3.81 | 1.286 | 6 | |

| 27. Irritability and tension | 3.91 | 1.141 | 4 | |

| 28. Receiving psychosocial support | 3.04 | 1.366 | 13 | |

| 29. Anxiolytic use | 2.37 | 1.362 | 15 | |

| 30. Alcohol consumption | 2.31 | 1.314 | 16 | |

| 31. Smoking | 2.50 | 1.471 | 14 | |

| 32. Self-harm behaviour | 1.72 | 1.166 | 17 | |

| Effects of Stress Factors on Family Life | 3.70 | |||

| 33. Marital conflicts | 4.06 | 1.04 | 2 | |

| 34. Income related family stress | 4.02 | 1.208 | 3 | |

| 35. Insufficient engagement in elderly care | 3.23 | 1.436 | 10 | |

| 36. Limited time with children | 3.50 | 1.399 | 9 | |

| Effects of Workplace Stress Factors on Social Life | 3.90 | |||

| 37. Limited time for personal growth | 3.84 | 1.128 | 5 | |

| 38. Dissatisfaction with life | 3.84 | 1.259 | 5 | |

| 39. Inability to engage in preferred activities (such as traveling, learning languages, participating in artistic activities, etc.) | 4.07 | 1.139 | 1 | |

| 40. Social isolation (inability to meet with friends or others) | 3.84 | 1.216 | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selcuk, E.; Gundes, S. Workplace Stress Among Construction Professionals: The Influence of Demographic and Institutional Characteristics. Buildings 2025, 15, 4460. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244460

Selcuk E, Gundes S. Workplace Stress Among Construction Professionals: The Influence of Demographic and Institutional Characteristics. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4460. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244460

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelcuk, Eda, and Selin Gundes. 2025. "Workplace Stress Among Construction Professionals: The Influence of Demographic and Institutional Characteristics" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4460. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244460

APA StyleSelcuk, E., & Gundes, S. (2025). Workplace Stress Among Construction Professionals: The Influence of Demographic and Institutional Characteristics. Buildings, 15(24), 4460. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244460