Urban Building Carbon Sinks Under the Carbon Neutrality Goal: Research Hotspots, Measurement Frameworks, and Optimization Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

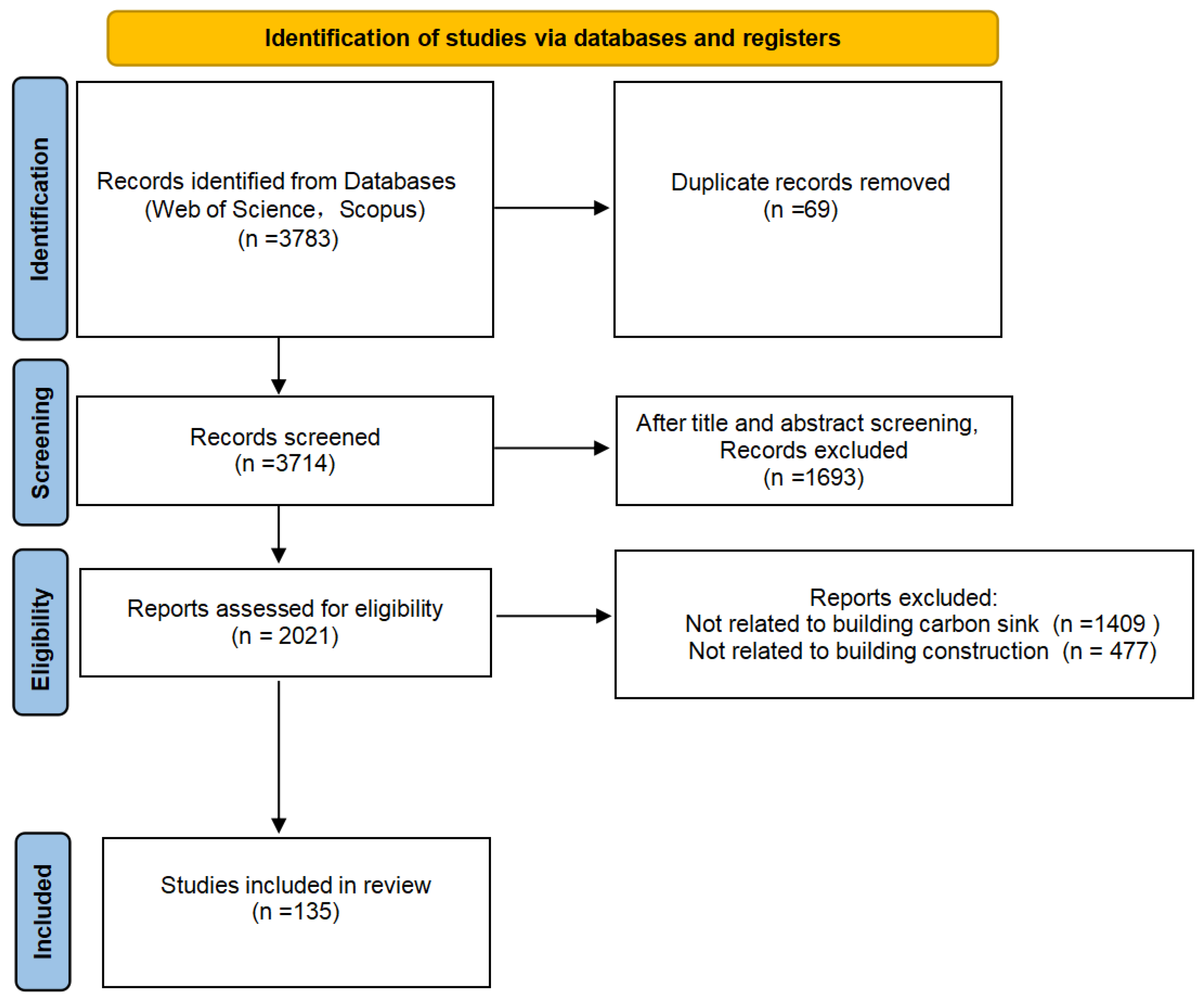

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Methodology

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- The research focuses on carbon sink technologies or materials related to buildings.

- The study involves measurement or evaluation methods for building carbon sinks.

- The article is a peer-reviewed academic publication.

2.3. Literature Statistical Analysis Combined with Qualitative Analysis

2.4. Summary of the Methodological Workflow

3. A Literature Review on Urban Building Carbon Sequestration Research

3.1. Literature Statistical Analysis

3.1.1. Reference Resource

3.1.2. Annual Publication Trends

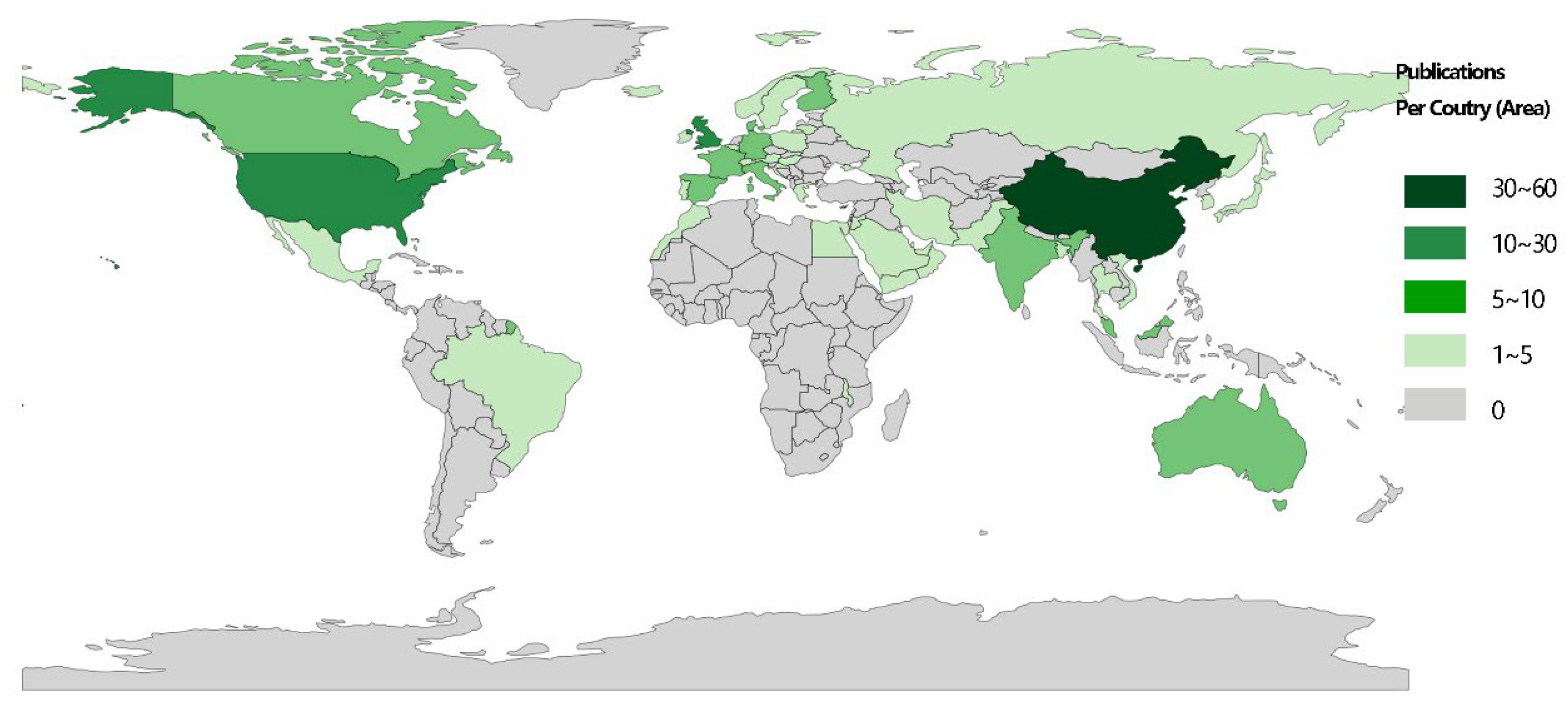

3.1.3. Geographical Distribution of Studies

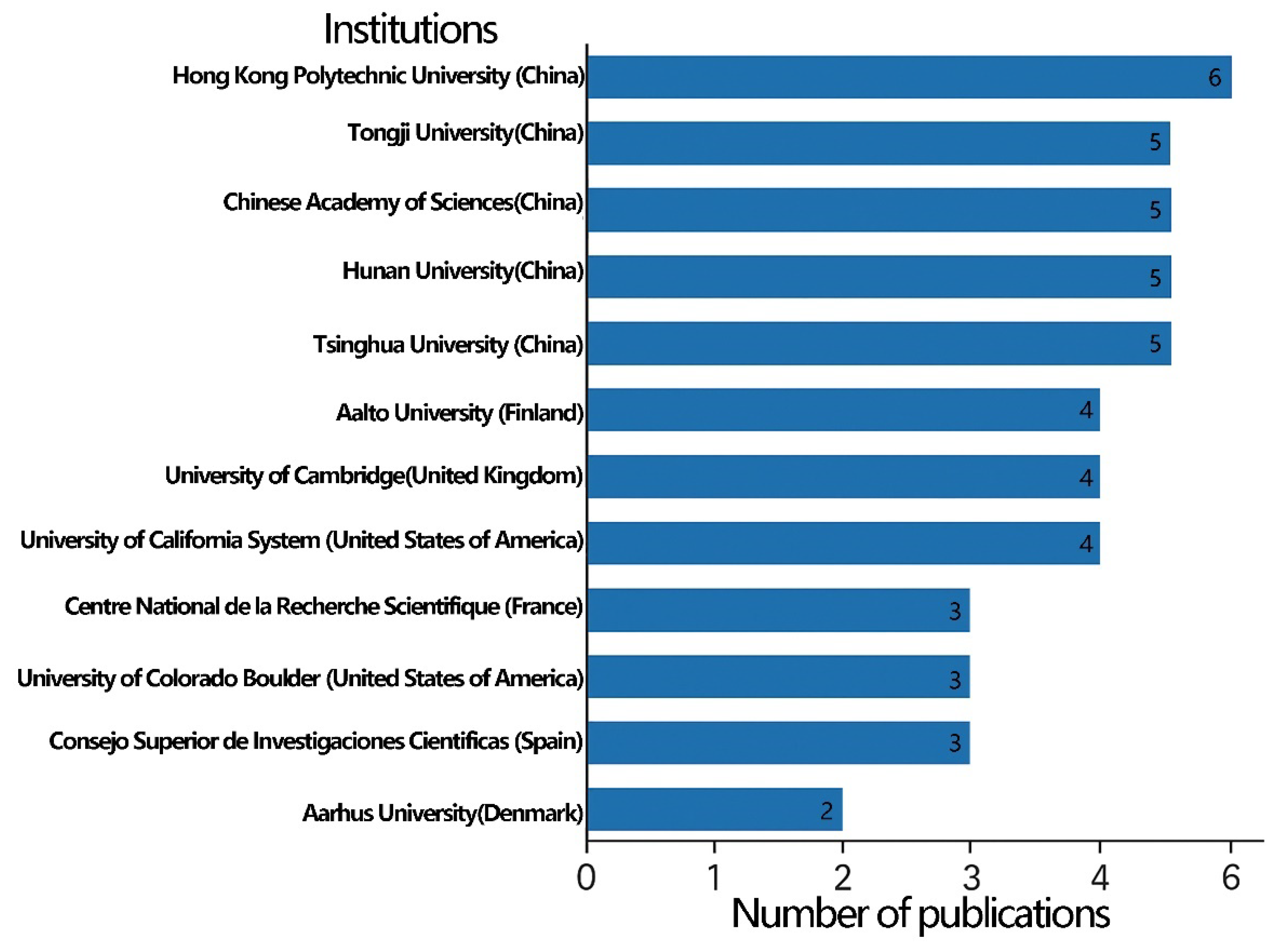

3.1.4. Institutional Contributions

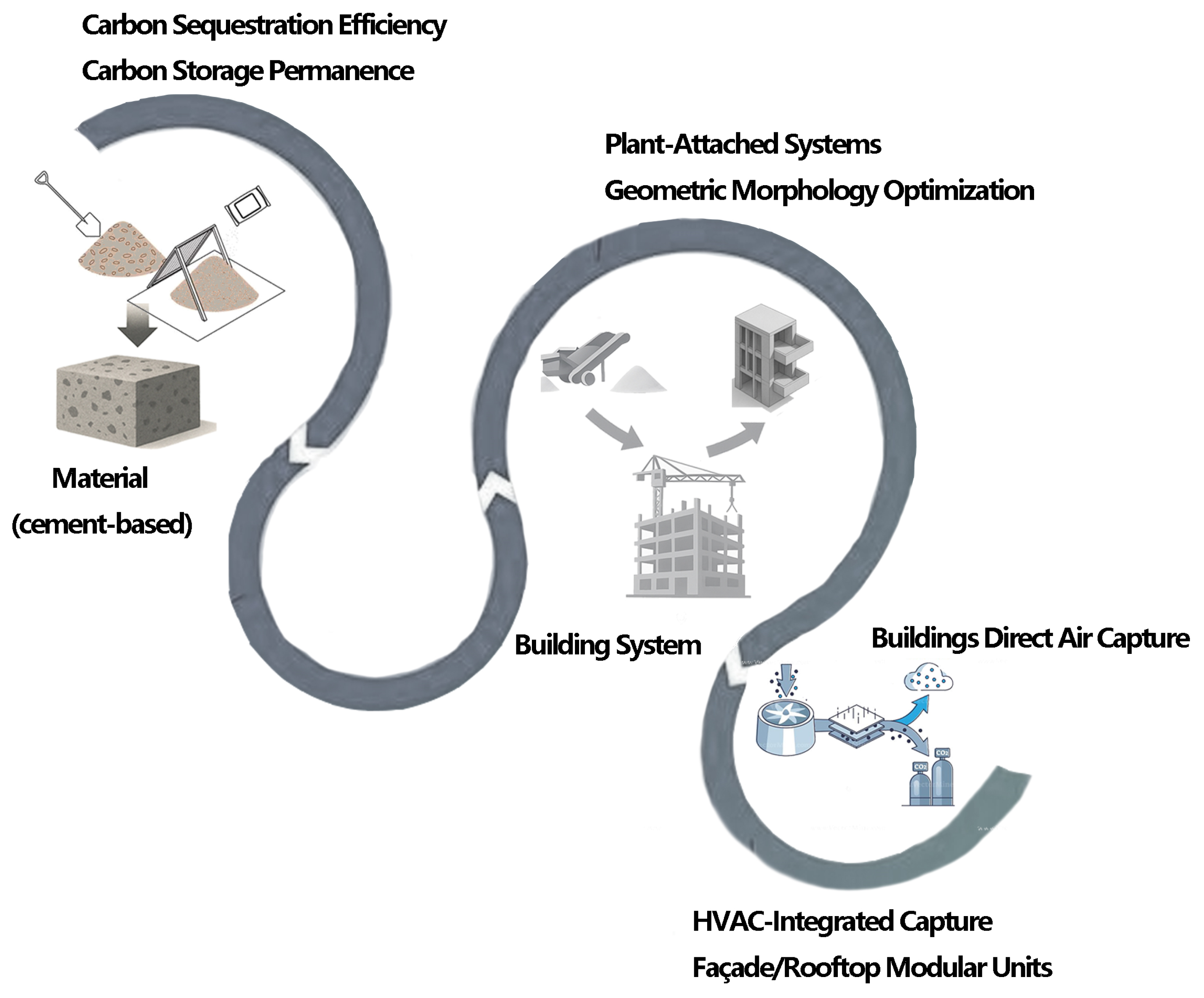

3.2. Literature Analysis: Analysis of Carbon Sequestration Processes

4. Evolution of Research Hotspots in Urban Building Carbon Sinks

4.1. Carbon Sinks in Building Materials

4.1.1. Carbon Sink Mechanisms of Different Materials

4.1.2. Carbon Sink Mechanism of Concrete

4.2. Building-Scale Carbon Sinks: Intrinsic and Attached Design Strategies

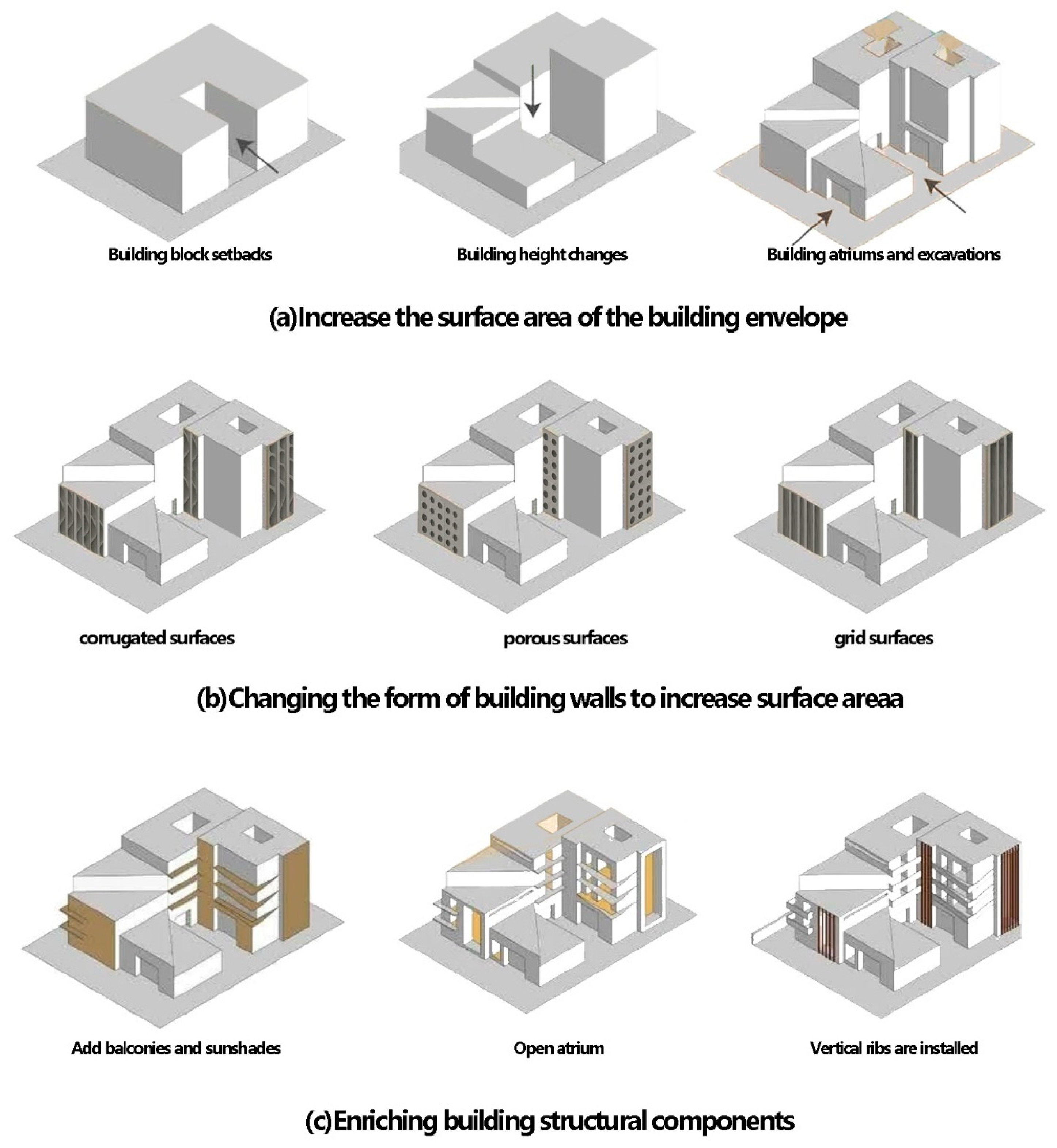

4.2.1. Carbon Sink Processes in Building Structures: Design Optimization for the Building Itself

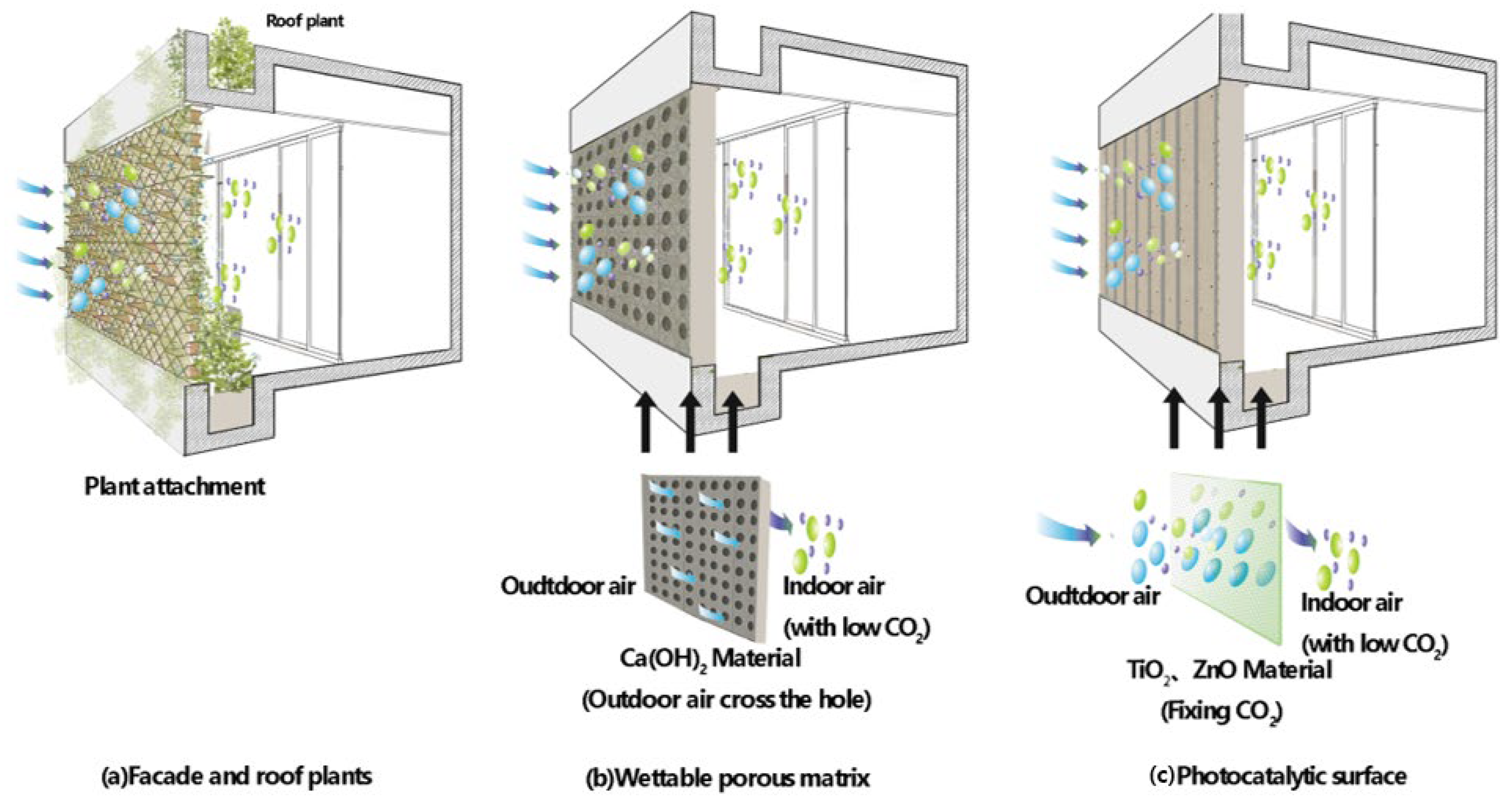

4.2.2. Carbon Sinks via Building Attachments: Vegetation, Moist Substrates, and Photocatalytic Interfaces

- Vegetation-Based Attachment Systems: Leaf-Surface Carbon Uptake and the “Biological Pump” Effect

- 2.

- Moist Porous Substrate Systems: Passive Adsorption and Mineralization Interfaces

- 3.

- Photocatalytic Surfaces: Artificial “Leaf” Systems for CO2 Conversion

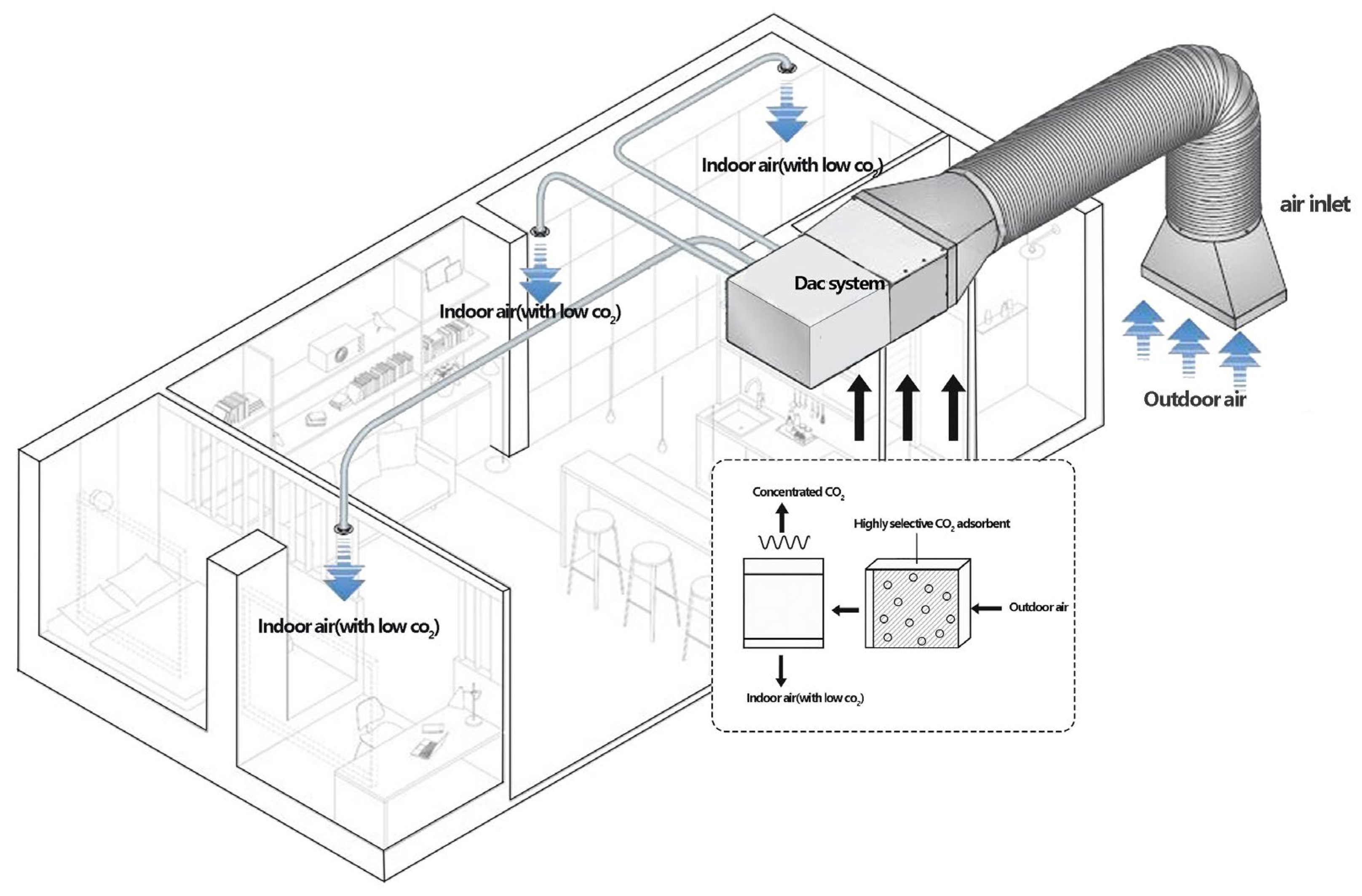

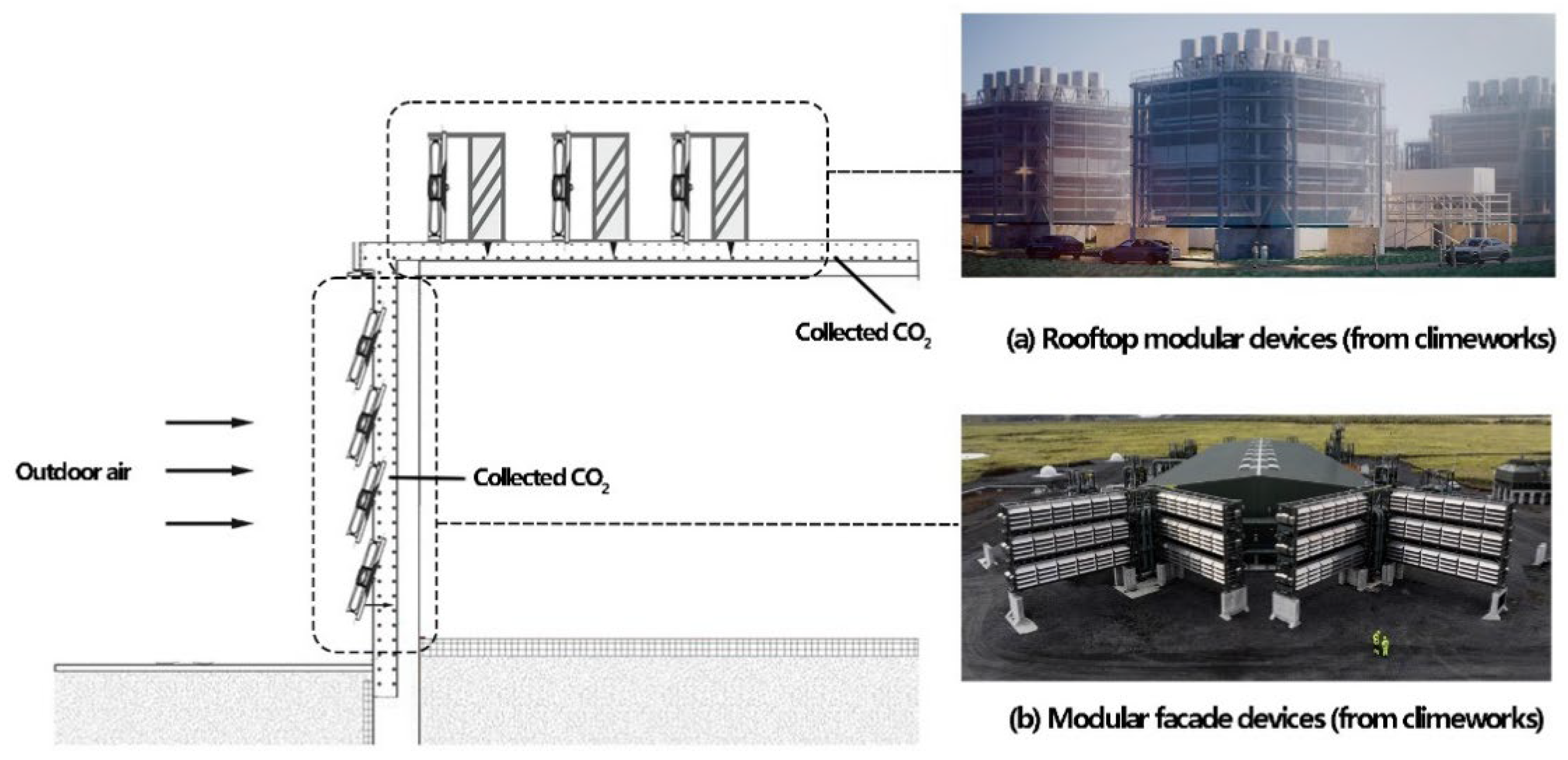

4.3. Active Carbon Capture in Buildings: From Spatial Devices to Urban Carbon-Cycle Nodes

Active Carbon Capture: Principles and Building Integration

5. Measurement Framework of Urban Building Carbon Sinks

5.1. Carbon Measurement Methods at the Material Level

5.2. Carbon Measurement at the Building-System Level

5.3. Measurement Methods for Building-Integrated Active Carbon Capture

6. Life-Cycle Optimization Design of Urban Building Carbon Sinks

6.1. Material Production Phase: Feedstock Selection and Mix Design

6.2. Design and Construction Phase: Spatial Geometry and Structural Strategies

6.3. Operations Phase: Dynamic Cycling and Replaceability

6.4. End-of-Life: Demolition and Regeneration to Extend the Carbon Cycle

7. Outlook and Challenges

7.1. Public Awareness and Societal Alignment

7.2. Toward Multi-Pathway Synergy and Integration

7.3. Robust Measurement and Standardized MRV

7.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

- Rapid growth with cross-disciplinary convergence. The field has accelerated since 2020, with leading contributions from China, the United States, and Nordic countries. Building carbon sink research now spans materials science, environmental engineering, building technology, and ecology, forming a robust interdisciplinary landscape.

- Thematic evolution mirrors rising technical maturity. Research has progressed from material-level carbonation mechanisms to building-system passive sinks, and now to active capture integration—broadening from single-material performance to spatial design and system optimization driven by carbon-neutrality goals.

- Multi-scale measurement remains challenging. Material-level methods (e.g., TGA, XRD) and system-level field techniques (e.g., phenolphthalein, static chambers) coexist with mass-balance approaches for active capture. Yet a cross-scale standardized MRV framework is still lacking, limiting comparability and synthesis.

- Life-cycle optimization is the key lever. Enhancing sink capacity requires systemic strategies spanning material production (optimized mixes, industrial by-products), design & construction (geometry to increase exposure), operations (ecological attachments and DAC coupling), and end-of-life (reuse and re-carbonation of wastes);

- Future direction: active integration and urban-scale benefits. With maturing DAC and related technologies, buildings can become active infrastructures for urban carbon regulation. Improved LCA practice will underpin optimized design toward net-zero/negative outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 863–953. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Seto, K.C.; Dhakal, S. Human settlements, infrastructure and spatial planning. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change, 1st ed.; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 923–1000. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Energy Technology Perspectives 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 280–348. [Google Scholar]

- Churkina, G.; Organschi, A.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Ruff, A.; Vinke, K.; Liu, Z.; Reck, B.K.; Graedel, T.E.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, D.W.; Holmes, G.; Angelo, D.S.; Heidel, K. A process for capturing CO2 from the atmosphere. Joule 2018, 2, 1573–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Hart, J.; Arehart, J.H.; D’Amico, B. Buildings as a global carbon sink? A reality check on feasibility limits. One Earth 2020, 3, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, K.; Rosasco, P. Cost–benefit analysis for green façades and living wall systems. Build. Environ. 2013, 70, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, F.; Davis, S.J.; Ciais, P.; Crawford-Brown, D.; Guan, D.; Pade, C.; Shi, T.; Syddall, M.; Lv, J.; Ji, L.; et al. Substantial global carbon uptake by cement carbonation. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ma, B.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y. Cement and concrete as carbon sinks: Transforming a climate challenge into a carbon storage opportunity. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, L. Accelerated carbonation technology for enhanced treatment of recycled concrete aggregates: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 282, 122671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Xian, X. A review for accelerated carbonation improvement of recycled concrete coarse aggregates and the meta-analysis of environmental benefit assessment and cost analysis of concrete so produced. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatian, O.; Sopian, K.; Salleh, E.; Lim, C.H.; Riffat, S.; Saadatian, E.; Sulaiman, M.Y. A comprehensive review of carbon dioxide reduction from green roofs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, G.; Coma, J.; Sol, S.; Cabeza, L.F. Green roofs and facades: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautamäki, R.; Lehvävirta, S. How urban green infrastructure contributes to carbon neutrality. Build. Cities 2025, 6, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Scrutinising embodied carbon in buildings: The next performance gap made manifest. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2431–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, C.; Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Measuring embodied carbon dioxide equivalent of buildings: A review and critique of current industry practice. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, J.; Rakha, T. Building-integrated carbon sequestration techniques: Towards mitigating climate change. In Proceedings of the ACSA/AIA Intersections Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 30 September–2 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arehart, J.H.; Hart, J.L.; Pomponi, F. Carbon sequestration and storage in the built environment: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–320. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Clowes, M.; James, M.M.-S. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, J.A., Jr.; Sanquetta, C.R.; Iwakiri, S.; de Mello Maron da Costa, M.D. The use of wood construction materials as a way of carbon storage in residential buildings in Brazil. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 21, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Stirling, R.; Morris, P.I.; Taylor, A.; Lloyd, J.; Kirker, G.; Lebow, S.; Mankowski, M.E. Durability of mass timber structures: A review of the biological risks. Wood Fiber Sci. 2018, 50, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, K.; Campoe, O.; Allan, N.; Hinkle, H. Increasing carbon sequestration, land-use efficiency, and building decarbonization with short rotation Eucalyptus. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, A.; Uibu, M.; Caramanna, G.; Kuusik, R.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. A review of mineral carbonation technologies to sequester CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 8049–8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habert, G.; Miller, S.A.; John, V.M.; Provis, J.L.; Favier, A.; Horvath, A.; Scrivener, K.L. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; Seo, E.A.; Tae, S.H. Carbonation and CO2 uptake of concrete. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2014, 46, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-efficient Cements: Potential Economically Viable Solutions for a Low-CO2 Cement-Based Materials Industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pade, C.; Guimaraes, M. The CO2 uptake of concrete in a 100-year perspective. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šavija, B.; Schlangen, E. Carbonation of cement paste: Understanding, challenges, and opportunities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 117, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Bishnoi, S. Understanding the process of carbonation in concrete using numerical modeling. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2021, 19, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura Gómez, P.; Sánchez Montero, J.; Torres Martín, J.E.; Chinchón-Payá, S.; Rebolledo Ramos, N.; Galao Malo, Ó. Carbonation-induced corrosion of reinforced concrete elements according to their positions in the buildings. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2023, 4, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottelé, M.; Perini, K.; Fraaij, A.L.A.; Haas, E.M.; Raiteri, R. Comparative life cycle analysis for green façades and living wall systems. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, M.; Pulselli, R.M.; Marchettini, N.; Pulselli, F.M.; Bastianoni, S. Carbon dioxide sequestration model of a vertical greenery system. Ecol. Model. 2015, 306, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, Y.A.; Abanades, J.C. Carbonation rates of dry Ca(OH)2 mortars for CO2 capture applications at ambient temperatures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 14804–14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zick, M.E.; Pugh, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Forse, A.C.; Milner, P.J. Carbon dioxide capture at nucleophilic hydroxide sites in oxidation-resistant cyclodextrin-based metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202206718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Meng, H.; Wu, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y. TiO2-based photocatalytic building material for air purification in sustainable and low-carbon cities: A review. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Efimova, O.; Breyer, C. Techno-economic assessment of CO2 direct air capture plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pérez, E.S.; Murdock, C.R.; Didas, S.A.; Jones, C.W. Direct capture of CO2 from ambient air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeppert, A.; Czaun, M.; Prakash, G.S.; Olah, G.A. Air as the renewable carbon source of the future: An overview of CO2 capture from the atmosphere. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7833–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kner, K.S. The thermodynamics of direct air capture of carbon dioxide. Energy 2013, 50, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Müller, T.E.; Thenert, K.; Kleinekorte, J.; Meys, R.; Sternberg, A.; Bardow, A.; Leitner, W. Sustainable conversion of carbon dioxide: An integrated review of catalysis and life cycle assessment. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434–504. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiat, I.; Abdullatif, Y.M.; Bicer, Y.; Amhamed, A.I.; Al-Ansari, T. Integrating direct air capture and HVAC systems: An economic perspective on cost savings. Syst. Control Trans. 2025, 1, 687–691. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Davis, S.J.; Creutzig, F.; Fuss, S.; Minx, J.; Gabrielle, B.; Kato, E.; Jackson, R.B.; Cowie, A.; Kriegler, E.; et al. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; et al. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): The way forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, T.; Treyer, K.; Bauer, C.; Mazzotti, M. Life cycle assessment of direct air carbon capture and storage with low-carbon energy sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11397–11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, V.; Shao, Y.; Boyd, A.J. Carbonation curing versus steam curing for precast concrete production. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2012, 24, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, B.; Poon, C.S.; Liu, Q.; Kou, S.; Shi, C. Experimental study on CO2 curing for enhancement of recycled aggregate properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 67, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.; Olek, J. Carbonation behavior of hydraulic and non-hydraulic calcium silicates: Potential of utilizing low-lime calcium silicates in cement-based materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 6173–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinour, H.H. Some effects of carbon dioxide on mortars and concrete—Discussion. J. Am. Concr. Inst. 1959, 30, 905–907. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H.D.; Caldeira, K. Stabilizing climate requires near-zero emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L04705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villain, G.; Thiery, M.; Platret, G. Measurement methods of carbonation profiles in concrete: Thermogravimetry, chemical analysis and gammadensimetry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teemusk, A.; Kull, A.; Kanal, A.; Mander, Ü. Environmental factors affecting greenhouse gas fluxes of green roofs in temperate zone. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, R.B. Electrochemical sensors for monitoring the corrosion conditions of reinforced concrete structures: A review. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Huang, X.; Xue, J.; Guan, X. A practical simulation of carbon sink calculation for urban buildings: A case study of Zhengzhou in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J.; Ash, R.M. Annual biomass loss and potential value of urban tree waste in the United States. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shi, T.; Bing, L.; Wang, Z.; Xi, F. Calculation method and model of carbon sequestration by urban buildings: An example from Shenyang. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzbacher, J.A.; Gebald, C.; Piatkowski, N.; Steinfeld, A. Concurrent separation of CO2 and H2O from air by a temperature–vacuum swing adsorption/desorption cycle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 9191–9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Darunte, L.A.; Jones, C.W.; Realff, M.J.; Kawajiri, Y. Systems design and economic analysis of direct air capture of CO2 through temperature vacuum swing adsorption using MIL-101(Cr)-PEI-800 and mmen-Mg2(dobpdc) MOF adsorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, A. Assessing the net carbon removal potential by a combination of direct air capture and recycled concrete aggregates carbonation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Gomes, K.V.; McCormick, C.; Blumanthal, K.; Pisciotta, M.; Wilcox, J. A review of direct air capture (DAC): Scaling up commercial technologies and innovating for the future. Prog. Energy 2021, 3, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ni, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Hitch, M.; Pascual, R. Carbonation of steel slag and gypsum for building materials and associated reaction mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 125, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W. Carbonation of cement-based materials: Challenges and opportunities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Dai, J.G.; Zhao, X.L. Magnesium cements and their carbonation curing: A state-of-the-art review. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSHub/MIT. Interim Report: Accounting for Carbon Uptake in the EPDs of Cement-Based Products; MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Lv, Z. Study on carbon fixation ratio and properties of foamed concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, B.R.; Li, V.C.; Skerlos, S.J.; Zhang, D.; Hu, W.H.; Lim, T.; Wu, H.; Adeoye, J.; Neves, A., Jr. Storing CO2 in Built Infrastructure: CO2 Carbonation of Precast Concrete Products; Technical Report; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Yan, J.; Huo, Y.; Chen, T. Effect of carbonation curing regime on 3D printed concrete: Compressive strength, CO2 uptake, and characterization. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Han, X.; Cao, X.E. Comprehensive performance evaluation of HVAC systems integrated with direct air capture of CO2 in various climate zones. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.R.; Dessì, P.; Cabrera-Codony, A.; Rocha-Melogno, L.; Kraakman, N.J.; Balaguer, M.D.; Puig, S. Indoor CO2 direct air capture and utilization: Key strategies towards carbon neutrality. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 20, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, L.; Yang, H. Recent progress in indoor CO2 capture for urban decarbonization. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.K.; Kim, J.; Ham, S.M.; Kim, S.; Han, A.T.; Kim, H.; Kwon, T.H. CO2 treatment of recycled concrete aggregates with high mortar contents: From finding optimal treatment condition, quality enhancement, to life cycle assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 137953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Roles of carbonated recycled fines and aggregates in hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties of concrete: A critical review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138, 104994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Li, L.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Abomohra, A. A comparative life cycle assessment on recycled concrete aggregates modified by accelerated carbonation treatment and traditional methods. Waste Manag. 2023, 172, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, N.N.; Shafique, M.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Z. Net zero carbon buildings: A review on recent advances, knowledge gaps and research directions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 3, e04200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Xiang, C. Green roofs and facades with integrated photovoltaic system for zero energy eco-friendly building—A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audus, H.; Riemer, P.W.; Ormerod, W.G. The IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme; CRE: Gloucestershire, UK, 2024; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaser, A.A.; Maxi, M.; Elmousalami, H. AI-powered digital twins and Internet of Things for smart cities and sustainable building environment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Dong, Y.; Tang, B.; Xu, Z. Developing a dynamic life cycle assessment framework for buildings through integrating building information modeling and building energy modeling program. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material Type | Carbon Sink Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Applicability at Urban Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based materials (e.g., wood, bamboo, agricultural by-products) | Absorb atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis during plant growth and store it as biogenic carbon | High carbon storage density; renewable; strong ecological benefits | Prone to degradation; limited durability; high fire risk; constrained by land and forestry resources, making large-scale use difficult | Moderate to low |

| Natural mineral materials (e.g., magnesite, carbonate rocks) | Combine with CO2 through mineral carbonation to form stable carbonate minerals | High carbon storage stability; capable of long-term sequestration | Slow natural carbonation rate; limited availability; high energy consumption in processing and transportation | Moderate |

| Concrete | Reacts with atmospheric CO2 during hardening and service life, forming calcium carbonate minerals | Largest global usage; significant scale effect; stable carbon storage; carbonation rate and capacity can be enhanced through material design | Low unit carbon uptake; high emissions during production | High |

| Comparison Metric | Passive Carbon Sink Strategies | Active Carbon Capture (DAC) Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Low cost, primarily driven by materials (e.g., concrete, vegetation) and maintenance over the life cycle | High initial investment (USD 600–900/t CO2/yr), but higher capture efficiency |

| Capture Rate | Low capture rate, typically 5–15 kg CO2/m3·yr (e.g., concrete) | High capture rate, typically 50–80 kg CO2/m2·yr (e.g., amine-based DAC systems) |

| Life-cycle Storage | Long-term storage (decades to centuries), but influenced by environmental changes | High short-term capture efficiency, but requires efficient storage, transport, and utilization systems |

| Practical Constraints | Limited by building design, material availability, climate impacts, and construction complexity | High energy consumption and operational costs, reliance on stable low-carbon energy, MRV uncertainties |

| Applicability | Widely applicable to large-scale infrastructure (e.g., urban buildings, green infrastructure) | Suitable for specific high-efficiency areas, such as building facades and industrial zones |

| Energy Demand | No additional energy requirements, mainly influenced by natural environment and building design | High energy demand, reliant on renewable energy to ensure net-negative emissions |

| Technology Maturity | Mature technology, widely applied in architectural design and urban greening | Still under development and demonstration, facing challenges with integration and scalability |

| Long-term Feasibility | Strong sustainability, relying on natural processes (e.g., plant photosynthesis, carbonation) | Requires optimization of energy consumption, cost reduction, and MRV system improvement for widespread deployment |

| Method Type | Key Methods | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material-level | TGA, XRD, FTIR, Chemical Titration | High precision, suitable for lab-scale studies | Does not capture environmental effects |

| System-level | Phenolphthalein, Gas Exchange, Sensors | Real-world performance, applicable at building scale | Environmental interference, high cost |

| Active Carbon Capture (DAC) | Mass Balance, Breakthrough Curve, NDIR Gas | High efficiency, direct CO2 removal | High energy demand, complex integration |

| Method | Technical Principle | Applicable Object | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Measures sample mass change with temperature/time; calculates CO2 fixation from carbonate decomposition loss | Concrete powder, mineral admixtures | High precision; quantitative; allows kinetic analysis | Destructive; requires sample grinding |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Identifies crystalline phases (e.g., CaCO3, MgCO3) via diffraction patterns | Carbonated concrete, mineral-sequestration materials | Strong phase identification; semi-quantitative | Insensitive to amorphous phases; costly instrumentation |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Detects characteristic C=O vibration bands in CO32− groups to determine bonding states | Cement hydrates, alkali-activated materials | High sensitivity; simple preparation | Low quantitative precision; requires calibration curves |

| Chemical Titration | Quantifies carbonate via acid-base neutralization or precipitation | Cement paste, industrial residues | Low-cost, simple, fast screening | Interference from impurities; subjective endpoint |

| Method | Technical Principle | Applicable Object | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolphthalein Indicator | Detects carbonation depth via color change (pink → colorless below pH 10.2) | Concrete walls, beams, columns | Fast, low-cost, intuitive | Semi-quantitative; destructive; humidity-sensitive |

| Gas Exchange Chamber | Monitors CO2 concentration change inside a sealed chamber over time | Green façades, carbonated surfaces | Direct CO2 flux; real-environment data | Microenvironment disturbance; small sampling area |

| Embedded Sensors | Measures pH/CO2 inside concrete over time via micro-sensors | Infrastructure, long-term monitoring | In situ, continuous, non-destructive | High cost; limited sensor lifespan |

| Model Estimation | Uses building or urban-scale models to estimate total sequestration | Single buildings or cities | Integrates multiple factors; macro insights | Dependent on assumptions; uncertainty high |

| Remote Sensing | Uses LiDAR or hyperspectral imaging to infer biomass/carbon stock | Green roofs, urban forests | Wide coverage, repeatable, scalable | Indirect; requires ground validation |

| Method | Technical Principle | Applicable Object | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Balance | Calculates total captured CO2 via inlet–outlet concentration difference and airflow rate | Building-integrated DAC units | Simple, real-time, system-level assessment | Requires airtight operation |

| Breakthrough Curve | Tracks outlet CO2 concentration vs. time in adsorption beds (S-shaped curve) | Sorbent testing, adsorption modules | High precision; kinetic parameters | Lab-scale; not for large systems |

| NDIR Gas Analysis | Measures CO2 via IR absorption at 4.26 μm | All CO2-monitoring processes | High accuracy; fast response; compact | High cost; periodic calibration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Zhou, C. Urban Building Carbon Sinks Under the Carbon Neutrality Goal: Research Hotspots, Measurement Frameworks, and Optimization Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 4445. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244445

Liu T, Zhou C. Urban Building Carbon Sinks Under the Carbon Neutrality Goal: Research Hotspots, Measurement Frameworks, and Optimization Strategies. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4445. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244445

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tianshuo, and Congyue Zhou. 2025. "Urban Building Carbon Sinks Under the Carbon Neutrality Goal: Research Hotspots, Measurement Frameworks, and Optimization Strategies" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4445. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244445

APA StyleLiu, T., & Zhou, C. (2025). Urban Building Carbon Sinks Under the Carbon Neutrality Goal: Research Hotspots, Measurement Frameworks, and Optimization Strategies. Buildings, 15(24), 4445. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244445