1. Introduction

Research shows that reducing unsafe behavior can improve workers’ safety performance [

1,

2]. Three main sources of unsafe behavior occur in the workplace, including disregarding safety regulations due to workload pressure, taking shortcuts to save time and energy, and misjudging risks [

3]. Among these antecedents, individual risk perception is regarded as a key link in the accident chain and has therefore attracted sustained scholarly attention. Differences in risk perception can directly affect risk communication: when facing the same hazards, managers and workers may reach divergent judgments, which hinders shared situational awareness and aligned action. Accordingly, identifying and understanding the existence of risk perception differences between workers and managers is crucial to facilitating effective risk communication and to designing targeted safety interventions.

However, most existing evidence relies on self-reports or behavioral outcomes, which show that differences exist but do not explain how they arise in the brain. Researchers still lack a clear understanding of the underlying neural mechanisms, including when they occur, at which processing stages they unfold, and through which cognitive-affective routes managers and workers diverge. This gap makes it difficult to pinpoint the cognitive bottlenecks that safety interventions should target. Studying the neural basis of risk perception can therefore (i) provide mechanistic evidence to refine dual-process models of risk perception, (ii) uncover implicit, preconscious processing that questionnaires cannot capture, and (iii) offer objective indicators to support the design and evaluation of safety training and intelligent monitoring systems in construction. These gaps motivate the present study.

1.1. Study of Risk Perception Discrepancy

Different characteristics of hazards can elicit different psychological reactions. In comparison with controllable hazards such as smoking and alcohol, uncontrollable hazards such as nuclear energy and gene technology tend to trigger greater fear and are perceived as high risk, even though the mortality rate caused by smoking and alcohol is often higher than that of nuclear accidents. Meanwhile, research has found that experts tend to value quantitative characteristics more, such as the likelihood of exposure and the severity of consequences [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Individual characteristics also have a significant influence on risk perception; factors including cross-cultural differences [

8], gender [

9], profession [

10], and knowledge [

5] all influence individual risk perception. As Friedman and Miles [

11] argue, individual views are embedded in social structures and cultural systems.

In construction, safety management involves multiple organizational layers—enterprise managers (setting overarching goals), project managers (overseeing project-level safety), and workers (executing site operations). Although all levels bear responsibility, role demands and task exposure imply that risk perceptions may diverge across groups, potentially creating communication barriers and undermining safety management. For instance, Zhao et al. [

10] reported that architects perceived lower risks than engineers. Wang et al. [

12] compared business managers and project managers, finding that different levels emphasized different risks; notably, project managers weighted technical and natural risks more during construction. However, these studies largely focus on managerial strata and overlook the frontline workforce—the group whose perceptions most immediately condition unsafe acts.

Construction safety is highly reliant on the risk perception of workers, as it directly impacts unsafe behaviors. Previous studies have indicated that there are differences in risk perception between workers and managers. Feng et al. [

13] used a psychological measurement paradigm and found managers tended to show higher perceived risk, with differences attributable to occupational background, incentives, and sensitivity to hazardous cues. Zhang et al. [

14] proposed a measurement of risk perception ability (RPA), and found that managers’ RPA was significantly superior to that of workers. Further, Hua et al. [

15] applied event-related potential (ERP) experiments and observed that managers allocated more attentional resources and exhibited stronger affective responses than workers, indicating stage-specific cognitive differences in processing risk information. Overall, evidence on cross-group differences exists but remains sparse, and researchers have not yet conducted systematic, mechanism-oriented comparisons of workers and managers in realistic construction scenarios.

1.2. Research on the Brain Mechanism of Risk Perception

Loewenstein et al. [

16] proposed that risk perception is based on two psychological mechanisms: a sensation-based “emotion-driven” route and a cognitively deliberative “outcome-oriented” route. Similarly, Slovic et al. [

17] distinguished a slow, effortful, analytic system from a fast, intuitive, experiential system.

Building on this dual-process view, advances in neuroscience have provided physiological evidence that enables more mechanistic accounts in safety science. By viewing risk perception as the cognitive processing of risk information, scholars have used electroencephalography (EEG), ERP and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to probe its neural basis and to propose mechanism-based models. For example, Qin and Han [

18,

19] showed that risky (vs. safe) environmental contexts modulate early perceptual/attentional components (P200) and late evaluative/affective components (LPP). In warning-message research, Ma et al. [

20] validated the Communication–Human Information Processing (C-HIP) model with attention and cognition stages; Bian et al. [

21] similarly argued that safety-sign processing involves rapid detection (P200) and conscious integration in working memory (N200/N400). Thus, differences in risk perception between workers and managers may also emerge in early perceptual/attentional components and in late evaluative/affective components.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the relevant ERP components.

In construction safety settings, recent EEG/ERP studies have applied neuroscience methods, further enriching this neural picture. Liao et al. [

22] identified a top-down attention reorientation mechanism for processing threatening stimuli. In terms of hazard identification, Jeon and Cai [

23] compared the differences in hazard recognition performance and neural indicators in construction scenarios in virtual reality and the real environment. Zhang et al. [

24] introduced the influence of incidental emotions on risk perception, finding earlier ERP components: P150 and N170 components, thereby further expanding the HPTS model into a three-stage emotional information-processing (EIP) model of risk perception: hazard identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation. Liu et al. [

25] investigated the temporal lag between visual attention and electroencephalographic activity when identifying hazards of human falls and object falls during construction. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [

26] analyzed eye-brain coordination mechanisms through fixation-related potentials (FRPs) to predict hazard recognition performance (HRP) and provide theoretical support for developing intelligent safety recognition devices. Zhang et al. [

27] investigated the effects of the interplay between top-down (T-D) and bottom-up (B-U) attention networks on hazard recognition. A recent review synthesized these indicators (θ/β, α power, P200/N200/P300/LPP, FRP) yet also highlights heterogeneous metrics and limited standardization [

28]. Despite this progress, one critical gap remains. Current EEG/ERP research primarily treats construction personnel as a homogeneous group and rarely compares different organizational roles directly. Thus, it remains unclear whether workers and managers differ mainly in early automatic detection of hazards, in later evaluative and affective processing, or in both.

Currently, most comparative studies on risk-perception differences still rely on questionnaires. These methods can show that differences exist but cannot explain their neural origins and often suffer from subjective and recall bias. Event-related potentials (ERP) offer millisecond temporal resolution and provide a powerful tool to decompose risk perception into early and late processing stages and to capture subtle divergences that precede overt behavior. Existing studies show that risk perception engages both early and late ERP components, but researchers still know little about how these stages differ between workers and managers. To address these gaps, we use ERP experiments to compare workers and managers in realistic construction scenarios and to describe group-specific neural dynamics across different information-processing stages. In this way, we move beyond describing group differences and provide mechanistic evidence that can inform risk communication and targeted safety management. Specifically, we operationalize risk perception with two complementary tasks: a hazard identification task, in which participants judge whether a hazard exists, and a risk judgment task, in which they answer, “How risky is the hazard?”

1.3. Hypothesis

In line with early ERP work on risk perception, researchers typically divide neural indices of risk perception into two types: early perceptual/attentional components and later evaluative/affective components. In construction-safety research, ERP studies mainly report early perceptual/attentional components such as P100, P150, and N200, as well as later evaluative/affective components such as P300 and the late positive potential (LPP). Building on this literature, Hua et al. [

15] showed that workers and managers differ primarily in an early attentional component (e.g., P100) and a late evaluative-affective component (e.g., LPP) during risk analysis tasks. Researchers typically treat the P150 as part of the P1 family and link it to early encoding of visual features and to the allocation of spatial attention to task-relevant stimuli [

29]. Researchers widely use the N200 as a neural marker of early cognitive control and conflict monitoring and relate it closely to attentional suppression and response inhibition [

30]. Its amplitude increases with decision conflict and task difficulty [

31]. The LPP reflects sustained, motivated attention toward stimulus significance and supports semantic elaboration and memory-related processing [

32]. Together, these components provide a set of stage-specific neural markers for early perceptual/attentional processing (P150, N200) and later evaluative-affective engagement (LPP) in construction risk perception.

Hence, we hypothesized that a risk perception discrepancy exists between workers and managers. In the hazard identification stage, compared with workers, managers’ accuracy of hazards identified (HI-ACC) is higher (H1a), and managers’ hazard identification reaction time (HI-RT) is shorter (H1b). We further expected that differences between workers and managers in risk perception processes would be reflected in early ERP components, such as P150 (H1c) and N200 (H1d). In the risk judgment stage, compared with workers, managers’ accuracy of risk judgment (RJ-ACC) is higher (H2a), and managers’ reaction time of risk judgment (RJ-RT) is shorter (H2b). We expected that differences between workers and managers in risk perception processes would be reflected in late components, such as the LPP (H2c). We also examined early components during the risk judgment stage on an exploratory basis, as additional indices of early visual–attentional processing; no directional hypothesis was formulated for early components in the risk judgment stage.

2. Materials and Methods

Section 2 describes the methodological framework of this study. We first present the participant sample (

Section 2.1) and the development and validation of the stimulus materials (

Section 2.2), followed by the experimental procedure for the two tasks (

Section 2.3). We then define the behavioral indicators used in the analyses (

Section 2.4) and finally describe the EEG recording parameters and ERP preprocessing and analysis methods (

Section 2.5).

2.1. Participants

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 [

33] to determine the required sample size. We specified a repeated-measures ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of Group (workers vs. managers) and a within-subjects factor reflecting repeated measurements across conditions, assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), a significance level of α = 0.05, and desired statistical power of 0.80. These parameters follow conventional standards for behavioral and ERP research and reflect a realistic expectation of medium-sized group differences in risk-related processing. Under these settings, the minimum required total sample size was estimated to be N = 30.

We randomly selected fifty-six construction professionals from two construction companies in Guangxi and Hunan, China, to participate in the study. Although the two companies operate in different provinces, they develop their safety management standards and operating procedures strictly in accordance with national safety production laws, regulations, and technical specifications, and they have both established relatively standardized safety management systems, so they do not represent idiosyncratic outliers. By drawing samples from two firms in different regions but with similarly regulated safety management systems, we minimized confounding organizational-level institutional differences and focused the analysis on role differences between workers and managers. This strategy also reduced the risk that our findings would reflect the unique culture of a single enterprise and thereby improved the external validity and generalizability of the results. We divided participants into two groups: 28 workers and 28 managers.

The workers’ group included frontline construction personnel from multiple trades, such as scaffolders, electricians, welders, and general laborers. Their daily tasks primarily covered civil works (e.g., excavation, formwork, and scaffolding erection) and installation activities (e.g., piping, cabling, and equipment installation), and they faced on-site hazards directly during routine operations. The managers’ group comprised full-time on-site project managers and safety managers, and their core duties centered on construction safety. In addition to coordinating project progress, they conducted regular safety inspections, identified and rectified hazards, completed safety documentation, organized and delivered safety education and training, and oversaw the day-to-day implementation of safety regulations on site. Thus, the managers’ group represents specialized safety management professionals who work within frontline construction projects, whereas the workers’ group represents frontline operators who primarily carry out physical construction tasks.

To ensure a homogeneous sample and to reduce variability due to brain health, sensory function, and hemispheric lateralization, all participants were free from neurological or mental disorders, possessed normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were right-handed. They provided informed consent prior to the study and received compensation for their participation. After the exclusion of outliers, valid data were obtained for the hazard identification task from 38 participants (20 workers and 18 managers). For the risk judgment task, valid data were collected from 44 participants, including 28 workers and 16 managers. The specific demographics of participants in the two tasks are shown in

Table 2. As shown in

Table 2, managers in these companies typically had higher levels of formal education and more systematic safety training than workers. Thus, in this sample, job role is not independent of education and training; these factors co-vary rather than being orthogonal. Accordingly, the comparison between managers and workers should be understood as capturing the joint effect of organizational role together with its typical education and safety-training profile in this context.

The experiment was approved by the Internal Review Board of the Neuromanagement Lab in Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

2.2. Materials

We obtained 140 photographs that each depicted a single hazard, and 35 standardized risk-free photographs from a real construction site (see

Figure 1). Each hazard photograph illustrated one typical unsafe condition that commonly occurs in construction, such as unsafe body postures during work at height, missing or improperly used personal protective equipment, inadequate edge protection or guardrails, obstructed or cluttered walkways, and unsafe proximity to openings, electrical installations, or moving equipment. In contrast, we took the 35 risk-free photographs on the same site while we strictly followed Chinese national safety standards for construction operations, such as sufficient fall protection, clear access routes, and appropriately managed materials and equipment. We photographed all images under natural daylight conditions, then anonymized them and standardized their size, resolution, contrast, and brightness for experimental presentation.

To define a standard for risk judgment accuracy (RJ-ACC), we obtained benchmark risk ratings for each of the 140 single-hazard images from an expert panel. The panel consisted of 40 individuals: 10 company managers, 10 safety patrol personnel, 10 experienced builders, and 10 university teachers with research expertise in risk perception. Each expert independently answered the question “How risky is the hazard?” on the same 5-point Likert scale used in the experiment (1 = little risk, 5 = great risk). For each image, the mean expert rating was calculated and then rounded to the nearest integer to obtain a consensus target rating. Inter-rater agreement among experts across images was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.99). In the behavioral data analysis, we treated a trial as correct when the participant’s rating for an image (1 = little risk, 5 = great risk) matched the expert target rating.

2.3. Procedure

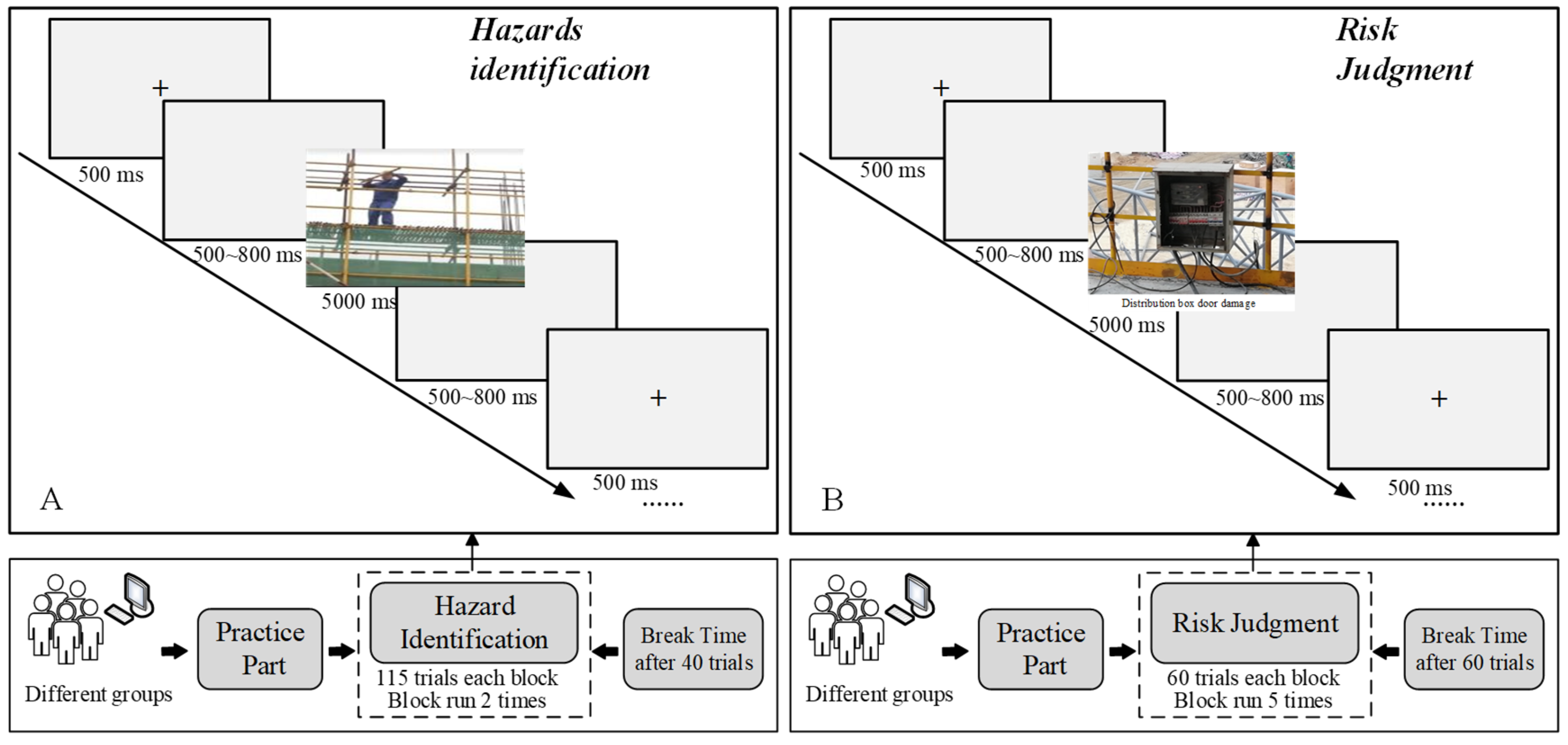

Each participant completed the tasks individually in a one-on-one laboratory session. Participants were seated in a quiet laboratory to complete the experiments, which comprised two blocks: hazard identification and risk judgment. In the hazard identification block, participants were asked to determine the presence of hazards in the images by pressing keys (‘1 = hazard exists’, ‘0 = no hazard’). This block consisted of 115 trials, including 80 pictures depicting a single hazard and 35 standardized risk-free images, presented in random order. Participants took a break every 40 trials (approximately every 2–3 min). The risk judgment block involved evaluating “How risky is the hazard?” on a Likert 5-point scale from ‘1 = little risk’ to ‘5 = great risk’, across 60 trials featuring images depicting a single hazard.

Experiments were categorized by participant group, either workers or managers. Stimuli were displayed at the center of a gray screen using E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The sequence of the experiments was as described, with stimuli presented on a computer screen located 100 cm away, at a visual angle of 9.831° × 7.552° (17.2 cm × 13.2 cm, width × height). As depicted in

Figure 2, each trial in the hazard identification task began with a fixation point on a gray background for 500 ms, followed by a blank screen for 500–800 ms. Subsequently, a picture was displayed at the center of the screen for 5000 ms against a gray background. Pilot testing with shorter exposure durations (e.g., 1500–3000 ms) resulted in excessive missed responses, reduced risk-rating variability, and substantial EEG artifacts due to hurried eye movements. Therefore, the 5000-ms window was selected as a compromise that preserved time pressure while allowing sufficient visual scanning and yielding stable ERP data across participants.

Participants were instructed to press the number keys (1 for ‘Yes’, 0 for ‘No’) to indicate the presence of a hazard. The risk judgment task mirrored the hazard identification task in terms of the durations of fixation and blank screen; however, each picture was displayed for 5000 ms. The order of picture presentation was randomized, and there was a five-minute break between each block.

2.4. Behavioral Measures

The behavioral data collected include key press results (RESP) and reaction time (RT). Based on this, behavioral data for hazard identification and risk judgment were calculated. Hazard identification behavioral data include the accuracy of hazards identified (HI-ACC) and the hazard identification reaction time (HI-RT); risk judgment behavioral data includes the accuracy of risk judgment (RJ-ACC) and the reaction time of risk judgment (RJ-RT). The calculation methods for each indicator are shown in the following

Table 3.

2.5. ERP Recording and Analysis

EEG data were recorded by an electrode cap (Brain Products, GER) with 32 Ag/AgCl electrodes mounted according to the extended international 10–20 system. ERP averages were computed offline by Analyzer 2.2.0 (Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany). The arithmetic mean of bilateral mastoids (TP9/TP10) was first selected in Analyzer software to re-reference the raw EEG data, and the filter bandpass was set to 0.3–40 Hz. Trials with amplifier clipping artifacts or peak-to-peak deflection exceeding ±100 μV were excluded from averaging. Stimulus-locked data were segmented into epochs comprising 200 ms before stimulus onset and 800 ms after the onset. The baseline correction was carried out using the first 200 ms of each channel. Superimposed averaging was conducted on the ERP waveforms for hazard identification tasks and risk judgment tasks, and the segmented ERP waveforms were group averaged for workers and managers. The measurement windows of P100, P150, N200, and LPP are shown in

Table 4.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Data

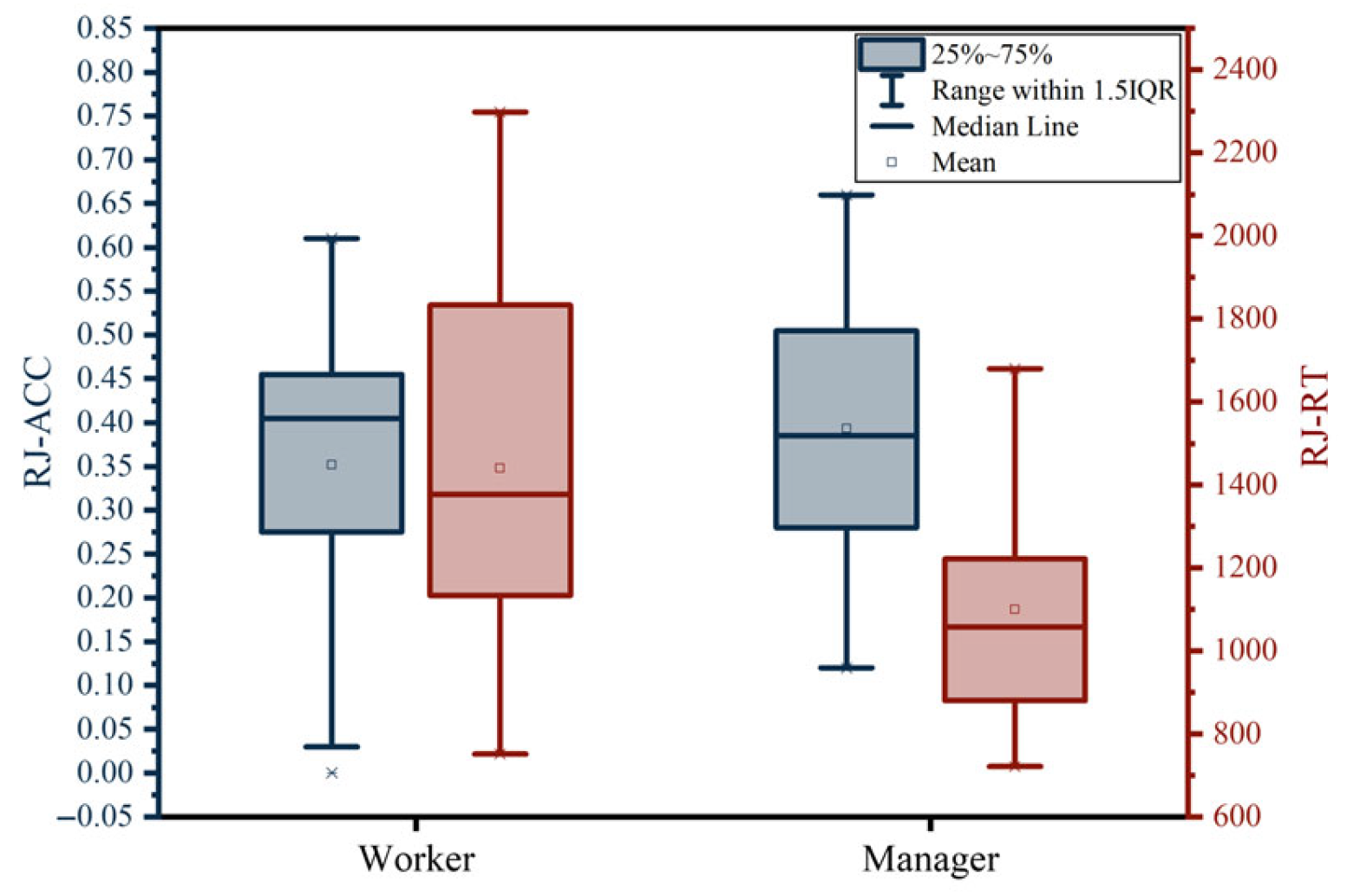

The distributions of workers’ and managers’ HI-ACC, HI-RT, RJ-ACC, and RJ-RT are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to perform a normality test on the above behavioral data, the results indicated that HI-ACC and RJ-RT did not follow a normal distribution while the rest of the indicators did. An independent-samples T-test was used to determine the differences in HI-RT, RJ-ACC between workers and managers. The results showed that the differences in HI-RT and RJ-ACC between workers and managers were not significant (H1b and H2a were rejected). The independent sample Mann–Whitney U-test was conducted to determine if there were significant differences in HI-ACC and RJ-RT between workers and managers. The results indicated that the accuracy of hazards identified (HI-ACC) of workers was significantly lower than that of managers (

p = 0.009 < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.118, −0.020]), with a medium rank-biserial effect size (

rrb = 0.489). The reaction time of risk judgment (RJ-RT) of workers was significantly greater than that of managers (

p = 0.012 < 0.05, 95% CI [78.964, 600.631]), with a medium rank-biserial effect size (

rrb = 0.460). H1a and H2b were accepted (see

Table 5).

3.2. ERP Data

3.2.1. N200 in Hazard Identification

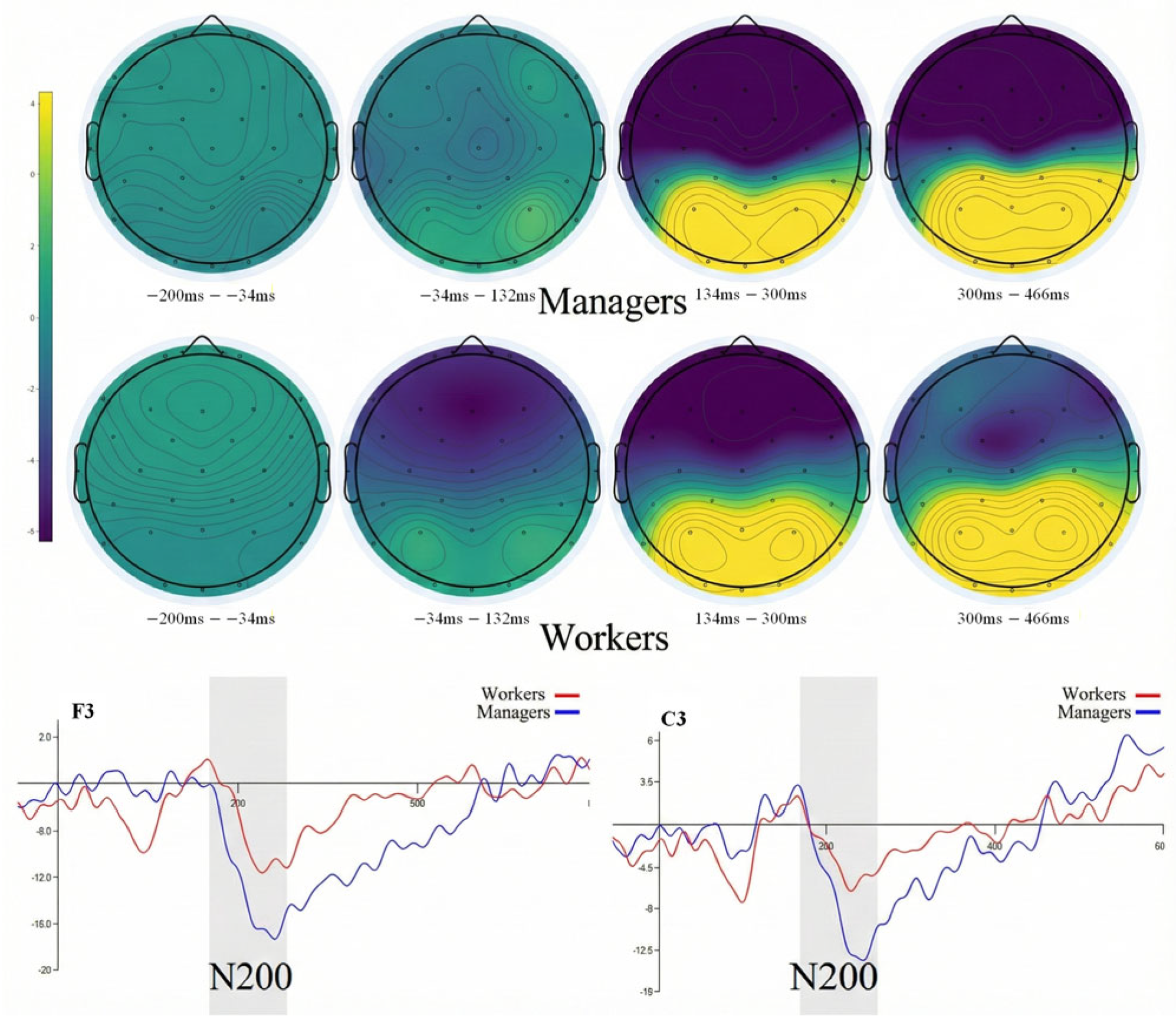

The brain activation patterns of managers and workers are shown in

Figure 5. 1 (Task condition: hazard identification) × 2 (Group: workers and managers) repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on P150 amplitude from electrode F4, Fz, and C3, which revealed that the main effect of the group was not significant (P150: F(1,35) = 0.035,

p = 0.853 > 0.05). H1c was rejected (see

Table 6).

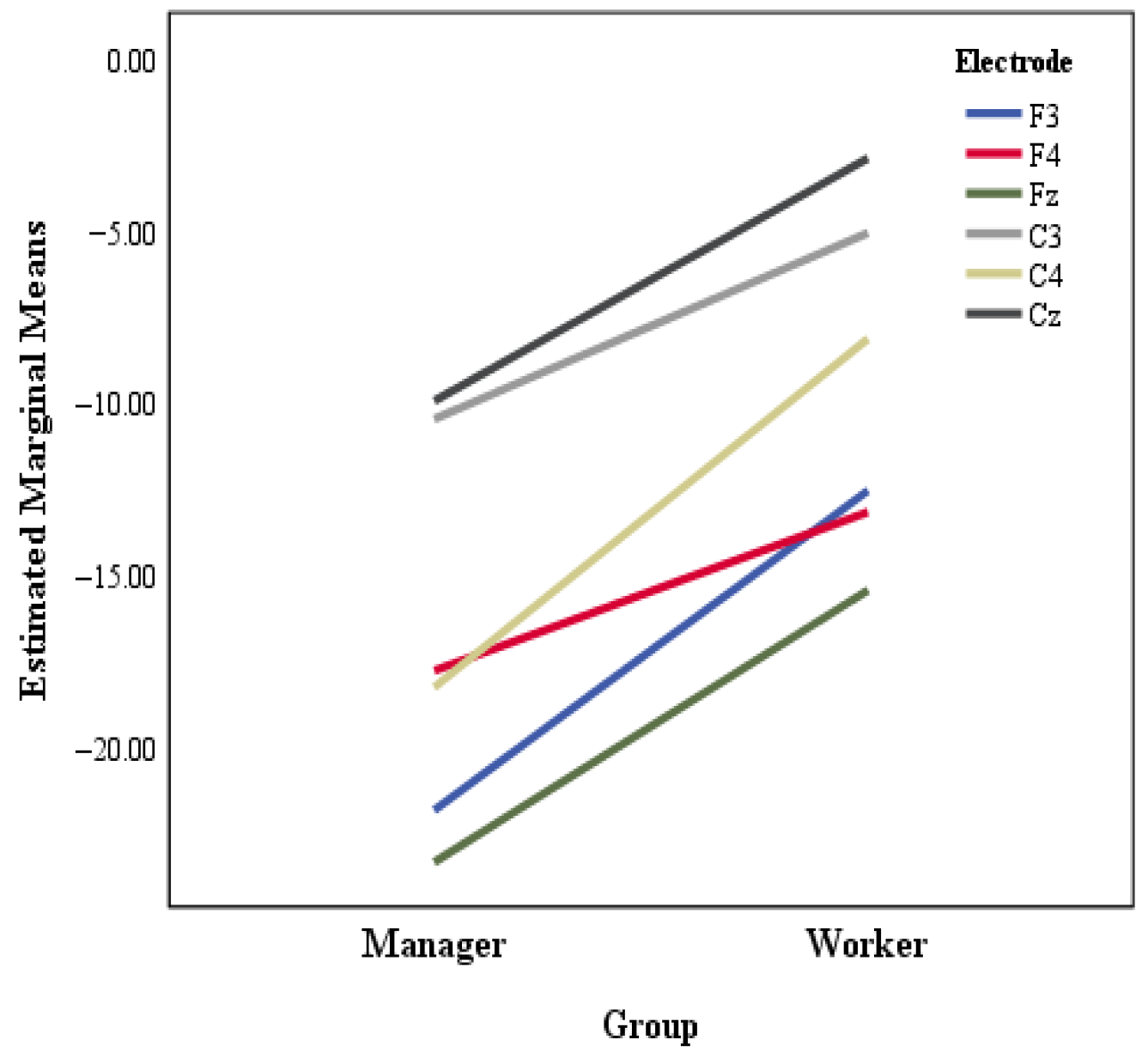

For the analysis of the N200 component, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on electrode F3, F4, Fz, C3, C4, and Cz. The results, shown in

Figure 5, demonstrated a significant main effect of group on the N200 (F(1,35) = 4.633,

p = 0.040 < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the average amplitude of the N200 for managers was significantly larger than that for workers (Absolute Δ = 7.385, η

2 = 0.115). H1d was accepted (see

Table 6,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

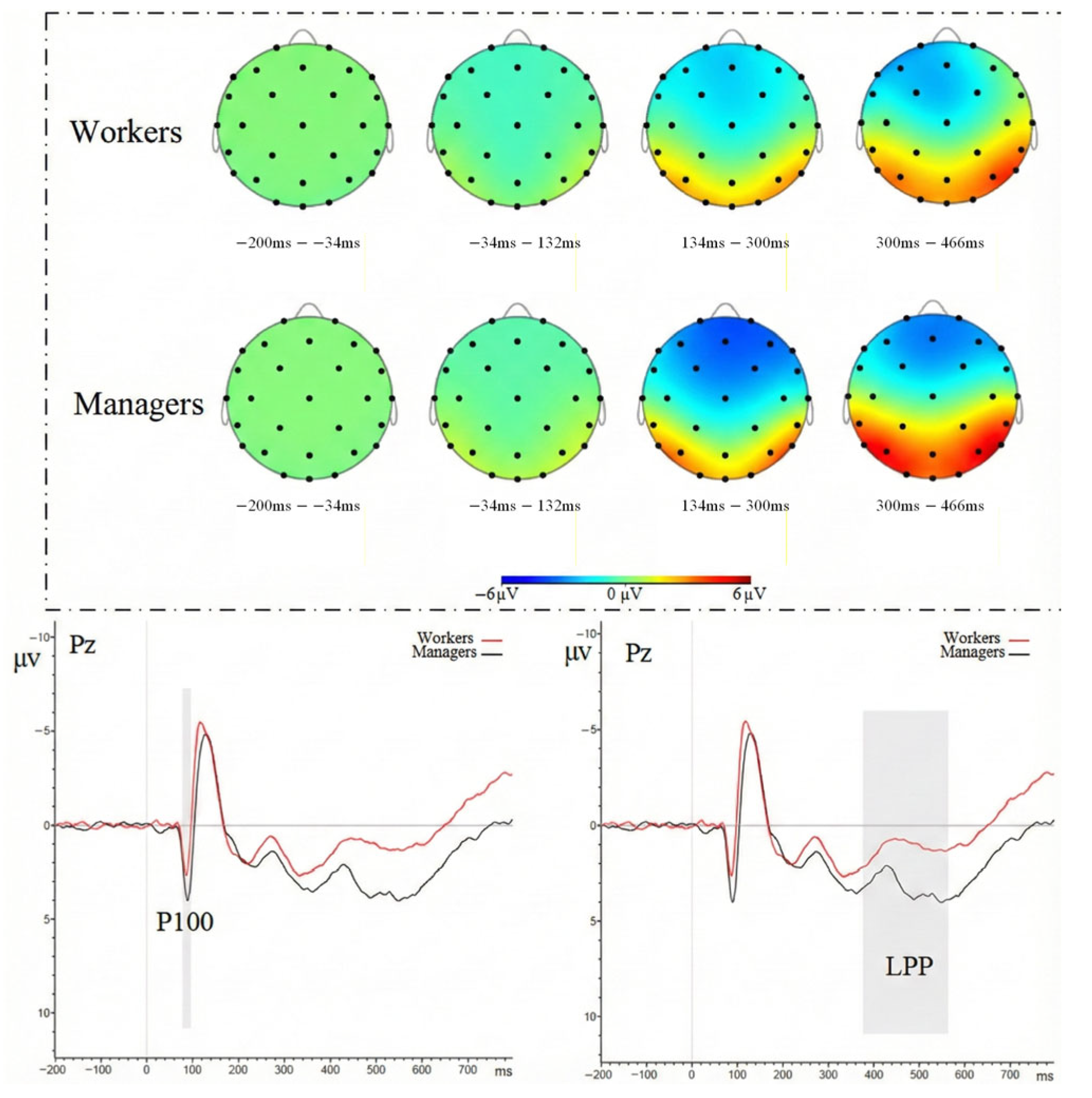

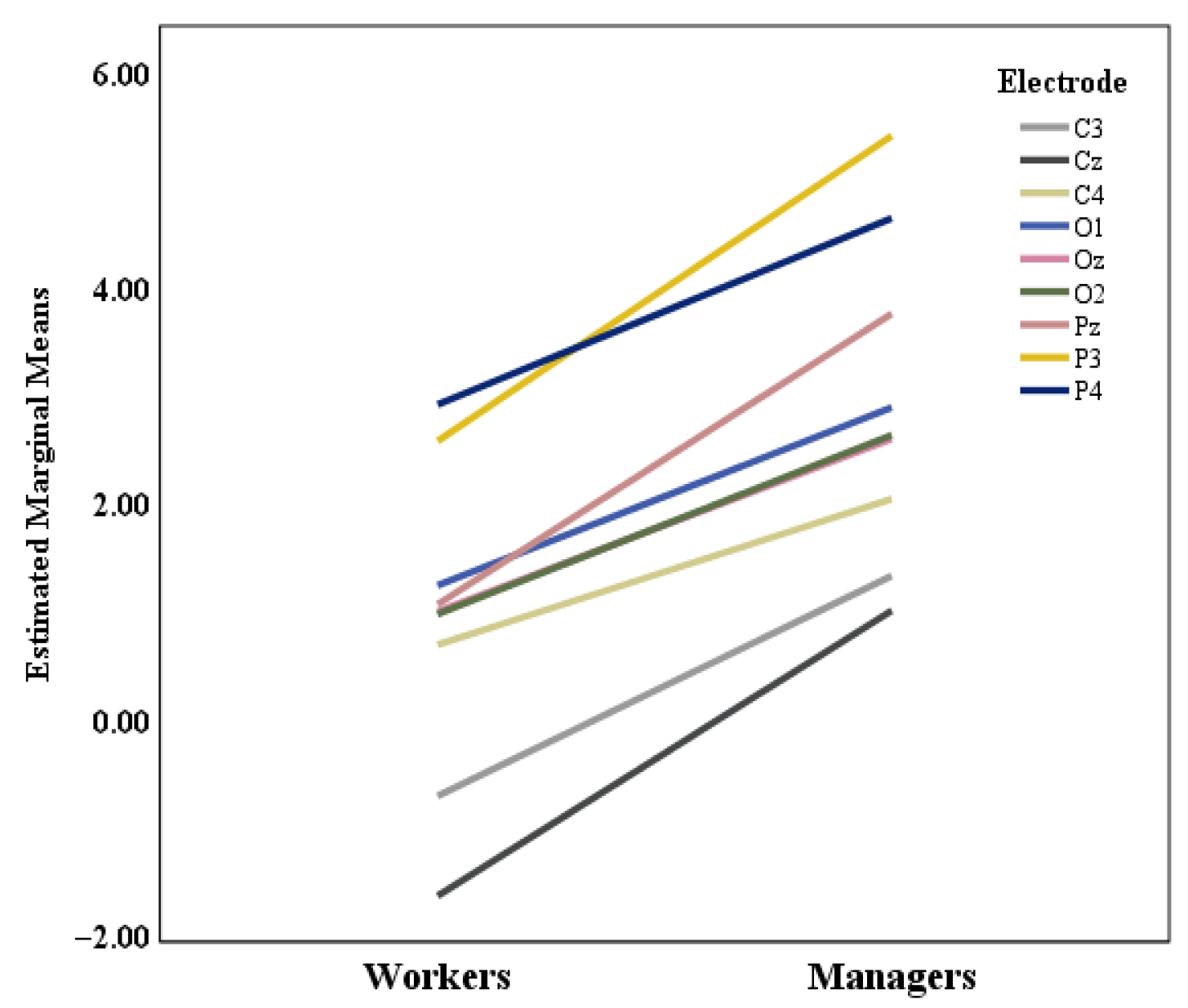

3.2.2. P100 and LPP in Risk Judgment

The brain activation patterns of managers and workers are shown in

Figure 7. 1 (task condition: risk judgment) × 2 (group: workers vs. managers) repeated-measures ANOVA on LPP amplitude at electrodes P3, P4, Pz, C3, C4, Cz, O1, O2, and Oz revealed a significant main effect of group (LPP: F(1,42) = 5.460,

p = 0.024 < 0.05). Exploratory analysis of early ERP components during the risk judgment stage revealed a significant group difference in P100 component from electrode P3, P4, Pz, O1, O2, Oz, CP1, and CP2 (P100: F(1,42) = 5.326,

p = 0.026 < 0.05).

Post hoc comparisons revealed that the average amplitude of the P100 for workers was significantly lower than that for managers (Absolute Δ = 1.544, η

2 = 0.113); the average amplitude of the LPP for workers was significantly lower than that for managers (Absolute Δ = 2.024, η

2 = 0.115). H2c was accepted (see

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9,

Table 7).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Discrepancy in Hazard Identification

4.1.1. The Difference in the Accuracy of Hazards Identified

According to behavioral data, in the hazard identification process, the accuracy of hazards identified (HI-ACC) of workers was significantly lower than that of managers (

p = 0.009 < 0.05), supporting H1a. From the demographic characteristics of workers and managers, workers are mostly temporary workers, with higher mobility and fewer opportunities for systematic training and learning. Managers have a higher level of education and usually undergo systematic job training. A recent study showed that more experienced participants and trained supervisors detect hazards more accurately and quickly, whereas novices miss more hazards [

34]. The aforementioned reasons may be related to managers having a higher accuracy rate in hazard identification. From the work goals of workers and managers, managers value the safety management effect of the construction process and have a stronger sense of responsibility for reducing hazards. Their work performance ties with safe construction and efficient completion. Workers value job experience and construction technology and pay more attention to work progress. Their behavioral benefits mainly come from taking risks to rush the work [

35]. The above differences may enable managers to develop a more comprehensive understanding of various hazards and become more sensitive to their occurrence. Therefore, compared with workers, managers are able to correctly identify the hazards presented in the images.

Differences in HI-RT between workers and managers were not significant (rejecting H1b). Several factors may explain the lack of group differences in HI-RT. First, during hazard identification (HI), the task emphasized detecting the presence of a hazard rather than responding quickly. Under accuracy-oriented instructions, participants typically adopt a cautious decision policy and spend more time to ensure correctness, thereby compressing between-group variability in reaction time [

36]. Second, image-based HI tasks often elicit convergent visual-search strategies. When task goals and scene statistics are shared, observers show regular, repeatable scan paths and fixation allocations that reflect common guidance and stopping policies [

37], which reduces RT separability. Finally, within the drift–diffusion model (DDM), workers and managers may operate under comparable boundary separation (a)—the amount of evidence required to commit to a choice—and similar nondecision time (Ter), which reflects perceptual/encoding and motor-execution durations [

38,

39]. Together, these similarities would produce no significant group difference in HI-RT. By contrast, the significant HI-ACC difference likely reflects managers’ more effective cue extraction and evidence accumulation during HI.

4.1.2. Neural Activity Discrepancy Underlying Behavioral Differences

In the hazard identification task, managers elicited significantly larger (more negative) N200 amplitudes than workers (

p = 0.040 < 0.05; partial η

2 = 0.115), indicating a medium-sized group difference. The N200 is a negative-going component that typically occurs 200–300 ms after stimulus onset. It is widely regarded as a neural marker of early cognitive control and conflict monitoring and is closely associated with attentional suppression and response inhibition [

30,

40,

41]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that N200 amplitude is positively correlated with the level of decision conflict and task difficulty [

31]. In the present context, the larger N200 in managers suggests stronger engagement of conflict monitoring and inhibitory control when scanning for hazards. By contrast, the smaller N200 in workers may reflect weaker recruitment of these control processes, which is consistent with their lower hazard identification accuracy (HI-ACC). Under the same time constraints, managers appeared to integrate diagnostic cues more efficiently, which plausibly accounts for their higher accuracy.

4.2. The Discrepancy in Risk Judgment

4.2.1. The Difference in the Reaction Time of Risk Judgment

For RJ-ACC, which did not differ significantly between workers and managers (rejecting H2a), a complementary explanation involves the multidimensional representation of risk. Classic work shows that risk judgments integrate at least two attributes—probability (vulnerability) and consequence severity—into a subjective “cognitive map,” with heterogeneous weighting across individuals and roles [

42]. Such heterogeneity pulls binary correct/incorrect classifications toward the group mean and thereby attenuates accuracy differences at the aggregate level. Under this account, even if neural indices of information processing differ between workers and managers (e.g., P100, LPP), RJ-ACC may still be non-significant, consistent with questionnaire-based findings reported by [

14].

During risk judgment, managers exhibited significantly shorter reaction times than workers (

p = 0.012), supporting H2b. In our sample, workers were predominantly temporary or itinerant employees with fewer opportunities for systematic safety training, whereas managers generally had higher education levels, longer tenure in construction, and more structured safety training experience. Prior work shows that experience and training not only improve identification accuracy but also reduce the time needed to appraise hazards [

34]. Role and employment conditions may further widen this gap. Temporary or itinerant employment is consistently associated with fewer training opportunities and lower safety competence [

43], which in turn correspond to slower and less confident risk assessments. Taken together, these sample characteristics may be associated with the shorter risk-judgment reaction times (RJ-RT) observed in managers compared with workers.

In addition, our definition of RJ-ACC relied on a single integer expert consensus rating as the “correct” level of risk for each image. This is a conservative criterion, because some reasonable individual differences in how participants weight probability versus severity, or other risk dimensions, will be classified as “incorrect”, potentially underestimating true similarities in risk appraisal across individuals and groups.

4.2.2. Neural Activity Discrepancy Underlying Behavioral Difference

In the risk judgment task, managers exhibited significantly larger amplitudes than workers for both the early P100 and the late LPP components. Effect sizes for these differences were in the medium range (P100:

p = 0.026 < 0.05, partial η

2 = 0.113; LPP:

p = 0.024 < 0.05, partial η

2 = 0.115). The LPP effect supports H2c, whereas the P100 difference did not form part of our a priori hypotheses, so we treat it as an exploratory finding. Functionally, the P100 component has been shown to reflect early-stage sensory gain, selective enhancement of task-relevant visual features, and suppression of irrelevant input during visual search [

44,

45,

46]. The larger P100 observed in managers may indicate more efficient attentional gating, characterized by greater amplification of hazard-relevant cues and stronger suppression of distractors. This exploratory interpretation aligns with the behavioral finding that workers exhibited longer risk-judgment reaction times (RJ-RT) than managers. Consistent with this exploratory pattern, Hua et al. [

15] reported higher P100 amplitudes in managers during probability and damage judgment tasks. However, this convergence should be interpreted cautiously and requires replication in future studies.

The LPP, typically occurring between 300 and 700 ms post-stimulus, reflects sustained, motivated attention toward stimulus significance. It supports processes such as semantic elaboration and memory encoding and retrieval [

32,

47]. Threatening or high-arousal stimuli robustly increase LPP amplitude compared to neutral or low-arousal content [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Accordingly, the larger LPP observed in managers reflects stronger motivational engagement and greater recruitment of cognitive resources for evaluative control during risk judgment. This enhanced processing may contribute to faster and more accurate responses. Beyond affective processing, converging evidence has linked the LPP to decision-evidence accumulation and choice confidence [

53]. Therefore, managers’ enhanced LPP may reflect a more efficient build-up of decision-related evidence when appraising hazard information.

Given that managerial status in this context is closely coupled with higher education and more systematic safety training, the enhanced P100 and LPP responses in managers are likely to reflect the cumulative effects of training and experience typically associated with managerial positions, rather than a pure effect of job title per se.

Taken together, our findings across both the hazard identification and risk judgment stages provide converging neural and behavioral evidence for group-level differences in risk perception. During the hazard identification stage, managers had stronger engagement of conflict monitoring and inhibitory control processes (Lower N200). During the risk judgment stage, managers had more effective early attentional gating of hazard-relevant cues (Larger P100) and stronger motivational engagement (Larger LPP) in risk judgment processing, reflecting a neurocognitive advantage in suppressing distractors and mobilizing higher-order control mechanisms. By integrating ERP and behavioral data across multiple risk perception stages, we demonstrated that group-level differences systematically emerge from conflict detection (N200) in hazard identification to perceptual selection (P100) and affective evaluation (LPP) in risk judgment. These findings extend prior related ERP research, which showed that compared to workers, managers exhibited larger LPP amplitudes and demonstrated greater accuracy during damage judgment tasks [

15].

4.3. Implications

Our findings have important implications for enhancing construction safety, particularly by improving risk communication across hierarchical roles. While effective communication between managers and frontline workers is critical for hazard mitigation, it is often undermined by divergent risk perceptions, which can lead to misunderstandings, delays, and suboptimal decisions. However, few studies have systematically examined the cognitive underpinnings of such perceptual misalignments. Using EEG techniques, we confirmed the existence of role-based differences in risk perception and further identified distinct neural mechanisms across multiple stages of risk perception—from hazard identification to risk judgment. These physiological findings provide objective and time-resolved evidence that can inform tailored communication and training strategies. Importantly, our results help fill a critical gap in the construction safety literature by moving beyond self-report measures, which are limited in explaining the cognitive mechanisms underlying risk perception differences.

The ERP patterns in our study indicate that the gap between workers and managers is stage-specific rather than global. Workers engage conflict monitoring and inhibitory control less strongly during hazard identification, as reflected in smaller N200 amplitudes and lower HI-ACC compared with managers, whereas during risk judgment managers exhibit stronger early visual–attentional gating, indexed by larger P100 amplitudes, and more sustained evaluative and motivational engagement with hazardous scenes, indexed by enhanced LPP amplitudes.

These findings suggest that training should not simply raise general awareness but should directly target distinct neurocognitive bottlenecks at both early selection and later evaluative stages. The weaker early visual and attentional responses of workers imply that short, high-frequency attentional-gating drills may help. For example, image- or VR-based exercises that require workers to rapidly scan complex site scenes and flag hazards under time pressure can strengthen P100-like mechanisms by amplifying hazard-relevant cues and suppressing distractors. Eye-tracking-based training platforms can also diagnose suboptimal visual search patterns and provide personalized feedback to improve workers’ scanning strategies. These training approaches highlight key hazard cues and optimize visual search strategies to strengthen workers’ early attentional gating, and they present ambiguous or conflicting risk scenarios to engage N200-related conflict detection and improve workers’ hazard recognition.

Secondly, managers’ advantage in risk judgment, reflected in shorter RJ-RT and larger P100 amplitudes, points to the value of structured, manager-led pre-task scanning that helps workers adopt more efficient early cue selection strategies. Before critical operations, supervisors can guide teams through standardized visual checklists and scenario walk-throughs and explicitly demonstrate how they prioritize and filter visual information. In parallel, larger LPP amplitudes in managers indicate deeper and more sustained evaluative processing of potential consequences. Training modules that incorporate vivid accident cases, near-miss analyses, and guided reflection may help workers build similar evaluative schemas and strengthen this late-stage appraisal process. These practices align with behavior-based safety programs and toolbox talks in construction, and our results suggest that they work best when they recalibrate workers’ early attentional focus (P100) and later evaluative engagement (LPP) so that they more closely resemble those of experienced managers.

Overall, we argue that recognizing and adapting to role-specific cognitive profiles is essential for developing evidence-informed interventions that not only reduce unsafe behavior but also improve shared situational awareness and risk communication on construction sites.

5. Conclusions

This paper concentrated on the differences in risk perception between workers and managers in two stages: hazard identification and risk judgment. Using ERP technology, this study revealed that the differences in risk perception existed between workers and managers. Specifically, at the hazard identification stage, workers showed significantly lower N200 amplitudes than managers, while at the risk judgment stage, managers exhibited significantly larger P100 and LPP amplitudes than workers. These differences in ERP components reflect divergent information-processing strategies in risk perception between workers and managers. Workers engage conflict monitoring and inhibitory control less strongly when deciding whether a hazard is present, as reflected in smaller N200 amplitudes, whereas managers show stronger early visual–attentional gating and more sustained evaluative processing of hazardous scenes. Workers also identify fewer hazards correctly and judge risk more slowly than managers. Taken together, these findings provide a time-resolved, neurocognitive explanation for the persistent risk-perception gap between workers and managers: workers struggle more at both early detection and later evaluative stages, whereas managers process hazard cues more efficiently and invest more evaluative resources in potential risks. By moving beyond self-report measures and linking specific ERP components (N200, P100, LPP) to stage-specific processing differences, this study advances the literature on manager-worker differences in construction safety and identifies concrete targets for risk communication and training interventions.

However, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, risk perception has multidimensional characteristics, such as the severity of accident consequences, the likelihood of occurrence, fear, exposure, etc. This study only examined the differences in risk judgment between workers and managers based on “How risky is it?”, without delving into different dimensions to explore the deeper differences. Second, our ERP paradigm necessarily simplified the temporal characteristics of real construction work. We asked participants to respond within fixed exposure windows that bounded decision time, but these windows still lasted longer than the time that workers typically have to perceive risk on active construction sites. This design may have reduced group differences in reaction time because both workers and managers could adopt relatively cautious decision policies. As a result, the behavioral gaps that we observed here likely underestimate the true performance differences under real-time working conditions. Third, we cannot directly map the absolute RJ-RT difference observed in the laboratory onto real site-level timescales. Our image-based laboratory paradigm did not model detailed hazard kinematics, worker movement sequences, or chained motor responses. As a result, we could not derive reliable site-specific thresholds (e.g., how many common hazards workers could avoid when RJ-RT decreases by X ms). Future studies should combine ERP measures with high-fidelity simulations or field observations to quantify how laboratory reaction-time differences translate into real-world safety outcomes. Future research can also (i) decompose “risk” into separable components, such as probability judgments, consequence-severity judgments, and affective responses, and test whether workers and managers diverge on these dimensions; (ii) complement the present laboratory paradigm with high-fidelity video or VR-based hazard scenarios and explicit time-pressure manipulations to assess whether the stage-specific neural markers identified here generalize to field performance; (iii) validate ERP indices against field-based indicators, including near-miss reports and on-site safety audits; and (iv) examine how “unknown-unknown” risk scenarios limit the usefulness of managers’ existing knowledge structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H.; Methodology, X.H. and S.Y.; Validation, Y.Z.; Formal analysis, J.L., X.H., Y.L. and S.Y.; Investigation, X.H. and S.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.Z., J.L. and X.H.; Supervision, S.Z., X.S. and Y.Z.; Project administration, S.Z., X.S. and Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2021JJ00).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Neuromanagement Lab in Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 20230315, 15 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Choudhry, R.M. Implementation of BBS and the Impact of Site-Level Commitment. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2012, 138, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, R.M. Behavior-based safety on construction sites: A case study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 70, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, R.A.; Hide, S.A.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Gyi, D.E.; Pavitt, T.; Atkinson, S.; Duff, A.R. Contributing factors in construction accidents. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, N.; Malmfors, T.; Slovic, P. Intuitive toxicology: Expert and lay judgments of chemical risks. Toxicol. Pathol. 1994, 22, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadori, L.; Savio, S.; Nicotra, E.; Rumiati, R.; Finucane, M.; Slovic, P. Expert and public perception of risk from biotechnology. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Keller, C.; Kastenholz, H.; Frey, S.; Wiek, A. Laypeople’s and experts’ perception of nanotechnology hazards. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hubner, P.; Hartmann, C. Risk Prioritization in the Food Domain Using Deliberative and Survey Methods: Differences between Experts and Laypeople. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 504–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, M.; Soler, J.; Trankle, U.; Spagnhol, J.M. Cross-cultural differences in driver risk-perception. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1989, 21, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.; Slovic, P.; Mertz, C.K. Gender, race, and perception of environmental health risks. Risk Anal. 1994, 14, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; McCoy, A.P.; Kleiner, B.M.; Mills, T.H.; Lingard, H. Stakeholder perceptions of risk in construction. Saf. Sci. 2016, 82, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Developing stakeholder theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Yu, H.; Wang, L. A Study on the Differences of Risk Cognition among International Construction Enterprises, Projects, and Legal Departments. J. Eng. Manag. 2019, 33, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Characteristics and causes of difference in hazard cognition of construction employees-based on the comparison between managers and workers. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Hua, X.; Shi, X. Measurement for Risk Perception Ability. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Zhang, S.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. Differences in Risk Analysis between Workers and Managers: Study from the Perspective of Neuroscience. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Han, S. Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying identification of environmental risks. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Han, S. Parsing neural mechanisms of social and physical risk identifications. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009, 30, 1338–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Jin, J.; Wang, L. The neural process of hazard perception and evaluation for warning signal words: Evidence from event-related potentials. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 483, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Fu, H.; Jin, J. Are We Sensitive to Different Types of Safety Signs? Evidence from ERPs. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, P.-C.; Zhou, X.; Chong, H.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, D. Exploring construction workers’ brain connectivity during hazard recognition: A cognitive psychology perspective. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2023, 29, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Cai, H. Wearable EEG-based construction hazard identification in virtual and real environments: A comparative study. Saf. Sci. 2023, 165, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. The influencing mechanism of incidental emotions on risk perception: Evidence from event-related potential. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Liang, M.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Liao, P.-C. Time lag between visual attention and brain activity in construction fall hazard recognition. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liang, M.; Liao, P.-C. Toward an Intuitive Device for Construction Hazard Recognition Management: Eye Fixation–Related Potentials in Reinvestigation of Hazard Recognition Performance Prediction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, B.H.W.; Feng, Z.; Goh, Y.M. Investigating the interplay of bottom-up and top-down attention in hazard recognition: Insights from immersive virtual reality, eye-tracking and electroencephalography. Saf. Sci. 2025, 187, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xu, D.; Xu, P.; Hu, C.; Li, W.; Xu, X. Neuroscience meets building: A comprehensive review of electroencephalogram applications in building life cycle. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 85, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, A.; Thoma, V.; De Fockert, J.W.; Richardson-Klavehn, A. Event-related potential effects of object repetition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, R.; Foerster, A.; Kunde, W. Pants on fire: The electrophysiological signature of telling a lie. Soc. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Q. The neural basis of risky decision-making in a blackjack task. Neuroreport 2007, 18, 1507–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajcak, G.; Weinberg, A.; MacNamara, A.; Foti, D. ERPs and the Study of Emotion. In The Oxford Handbook of Event-Related Potential Components; Kappenman, E.S., Luck, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Tan, Y.; Xia, Z.; Feng, K.; Guo, X. Effects of construction workers’ safety knowledge on hazard-identification performance via eye-movement modeling examples training. Saf. Sci. 2024, 180, 106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, G. A cross-level influence of group cognition on individual unsafe behavior intention. China Saf. Sci. J. 2019, 29, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz, R.P. The speed-accuracy tradeoff: History, physiology, methodology, and behavior. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowler, E.; Rubinstein, J.F.; Santos, E.M.; Wang, J. Predictive Smooth Pursuit Eye Movements. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2019, 5, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, R.; McKoon, G. The Diffusion Decision Model: Theory and Data for Two-Choice Decision Tasks. Neural Comput. 2008, 20, 873–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J.; Van Der Maas, H.L.J.; Grasman, R.P.P.P. An EZ-diffusion model for response time and accuracy. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2007, 14, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, T.A.; Chen, C. Trait anxiety and conflict monitoring following threat: An ERP study. Psychophysiology 2009, 46, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, J.R.; Van Petten, C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: A review. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M. Factors underlying observed injury rate differences between temporary workers and permanent peers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillyard, S.A.; Anllo-Vento, L. Event-related brain potentials in the study of visual selective attention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, S.J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, S.J.; Fan, S.; Hillyard, S.A. Attention-related modulation of sensory-evoked brain activity in a visual search task. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1993, 5, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolcos, F.; Cabeza, R. Event-related potentials of emotional memory: Encoding pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2002, 2, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, J. Working memory load modulates the neural response to other’s pain: Evidence from an ERP study. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 644, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, B.N.; Schupp, H.T.; Bradley, M.M.; Birbaumer, N.; Lang, P.J. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: Covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. Biol. Psychol. 2000, 52, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, H.T.; Cuthbert, B.N.; Bradley, M.M.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Ito, T.; Lang, P.J. Affective picture processing: The late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. Psychophysiology 2000, 37, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, H.T.; Cuthbert, B.N.; Bradley, M.M.; Hillman, C.H.; Hamm, A.O.; Lang, P.J. Brain processes in emotional perception: Motivated attention. Cogn. Emot. 2004, 18, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, H.T.; Stockburger, J.; Codispoti, M.; Junghoefer, M.; Weike, A.I.; Hamm, A.O. Selective visual attention to emotion. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, D.M.; Murphy, P.R.; Kelly, S.P.; O’Connell, R.G. The classic P300 encodes a build-to-threshold decision variable. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2015, 42, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).