Effects of Surface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Bond Performance of Geopolymer–Concrete Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Specimen Preparation

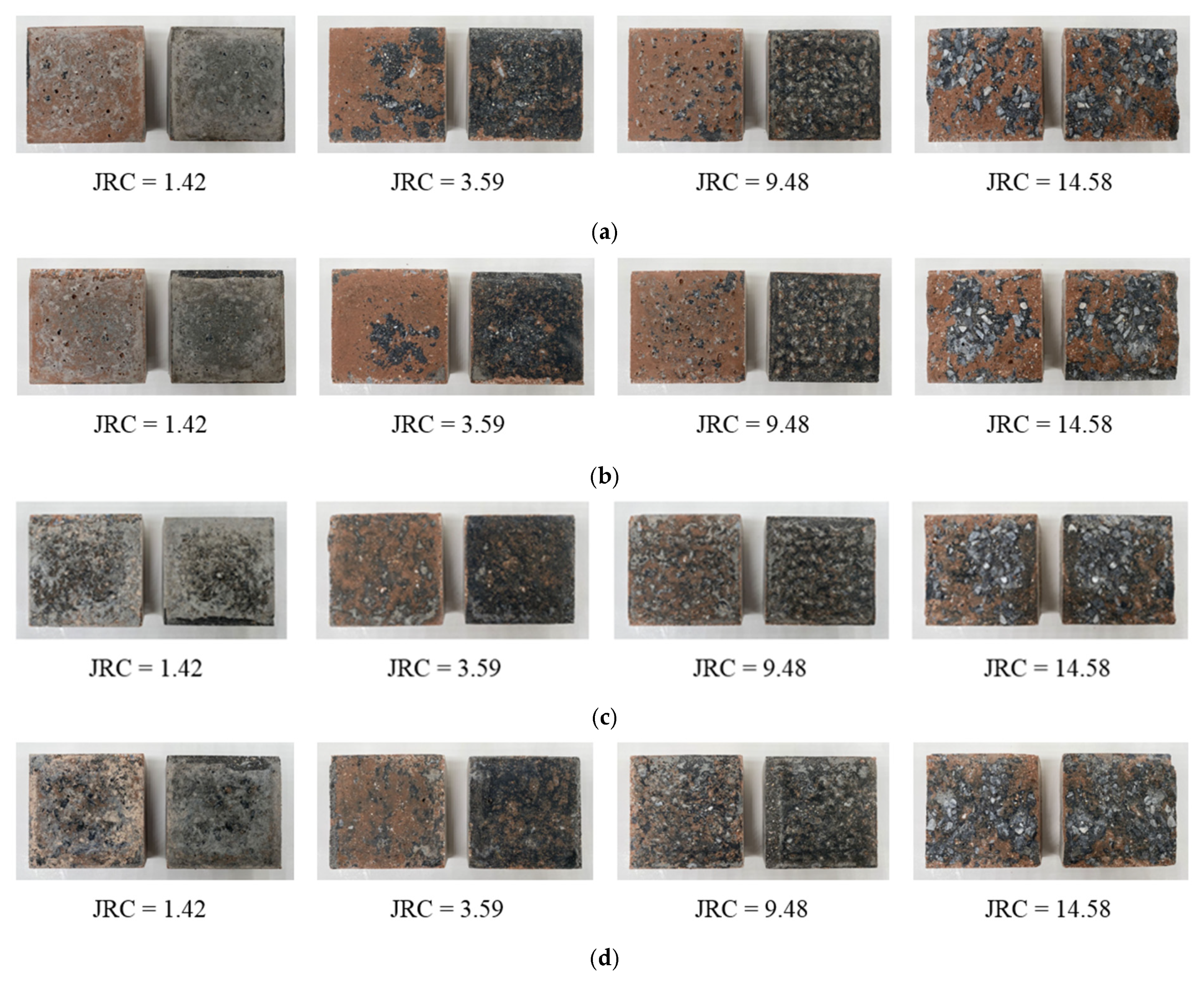

2.2.1. Preparation of Cement Concrete Substrate with Different Surface Roughness

2.2.2. The Preparation of GCC Specimens Using Different Interfacial Agents

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Surface Roughness Measurement

2.3.2. Splitting Tensile Test

3. Results and Discussion

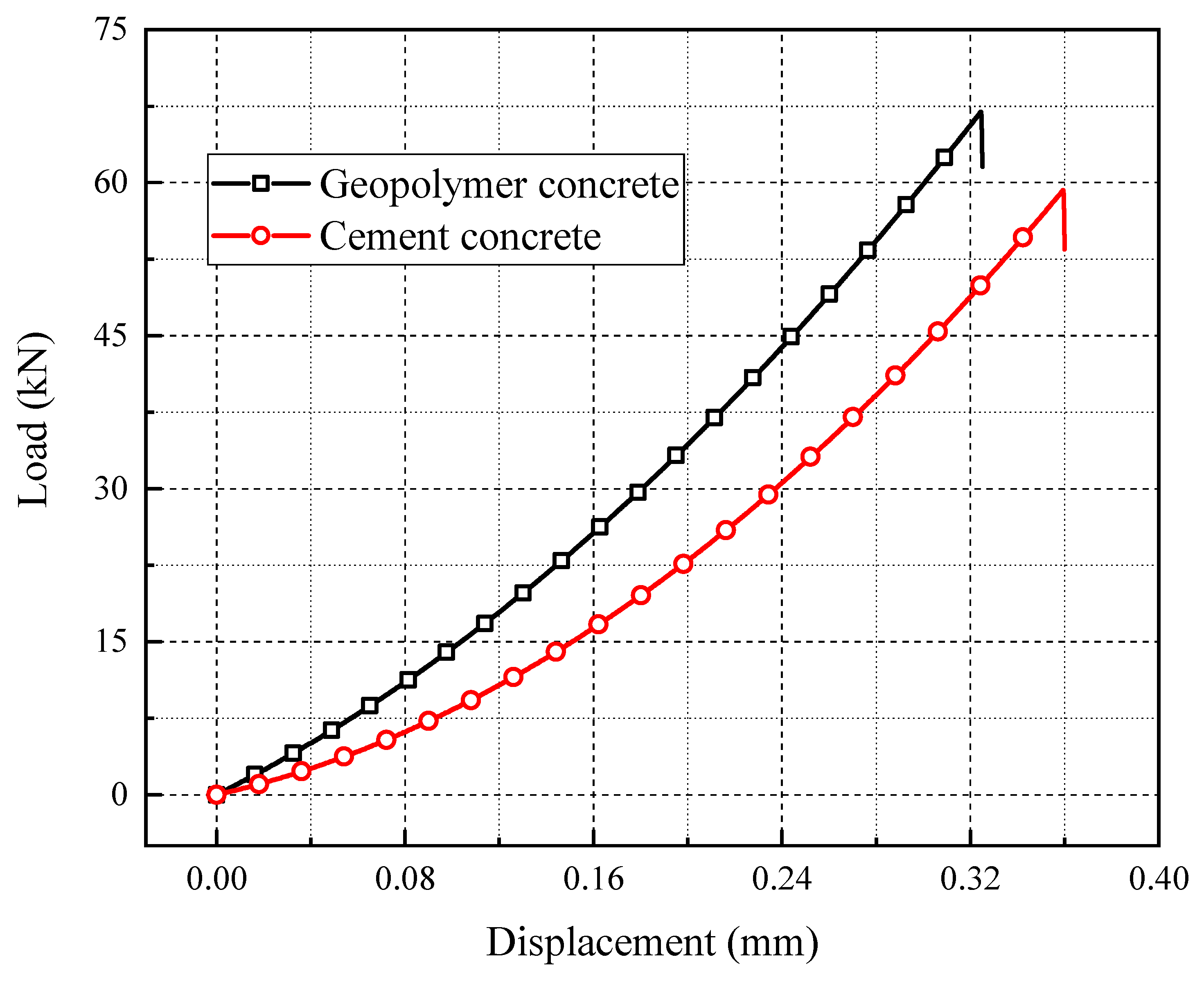

3.1. Splitting Tensile Load–Displacement Curve

3.2. Failure Mode

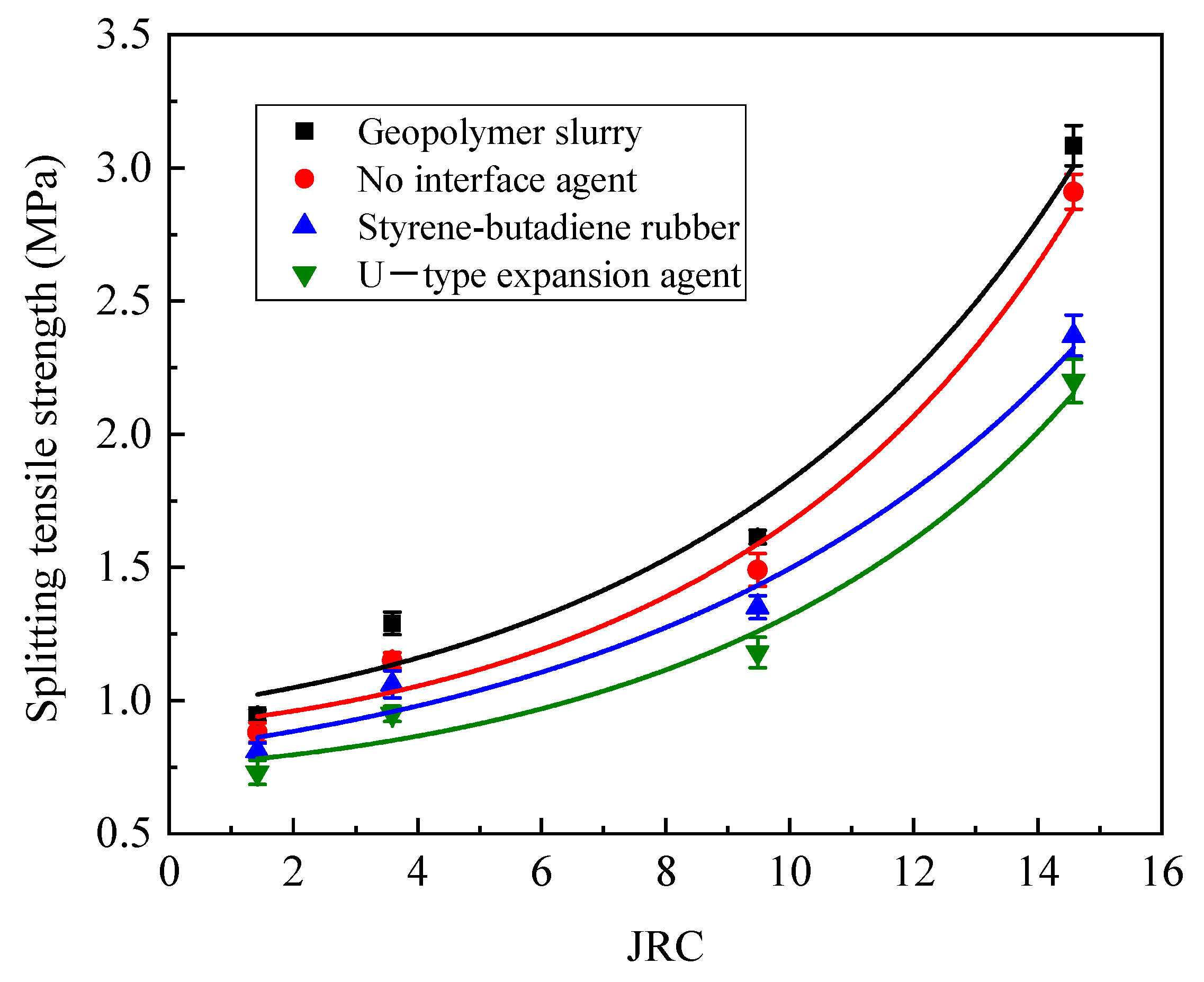

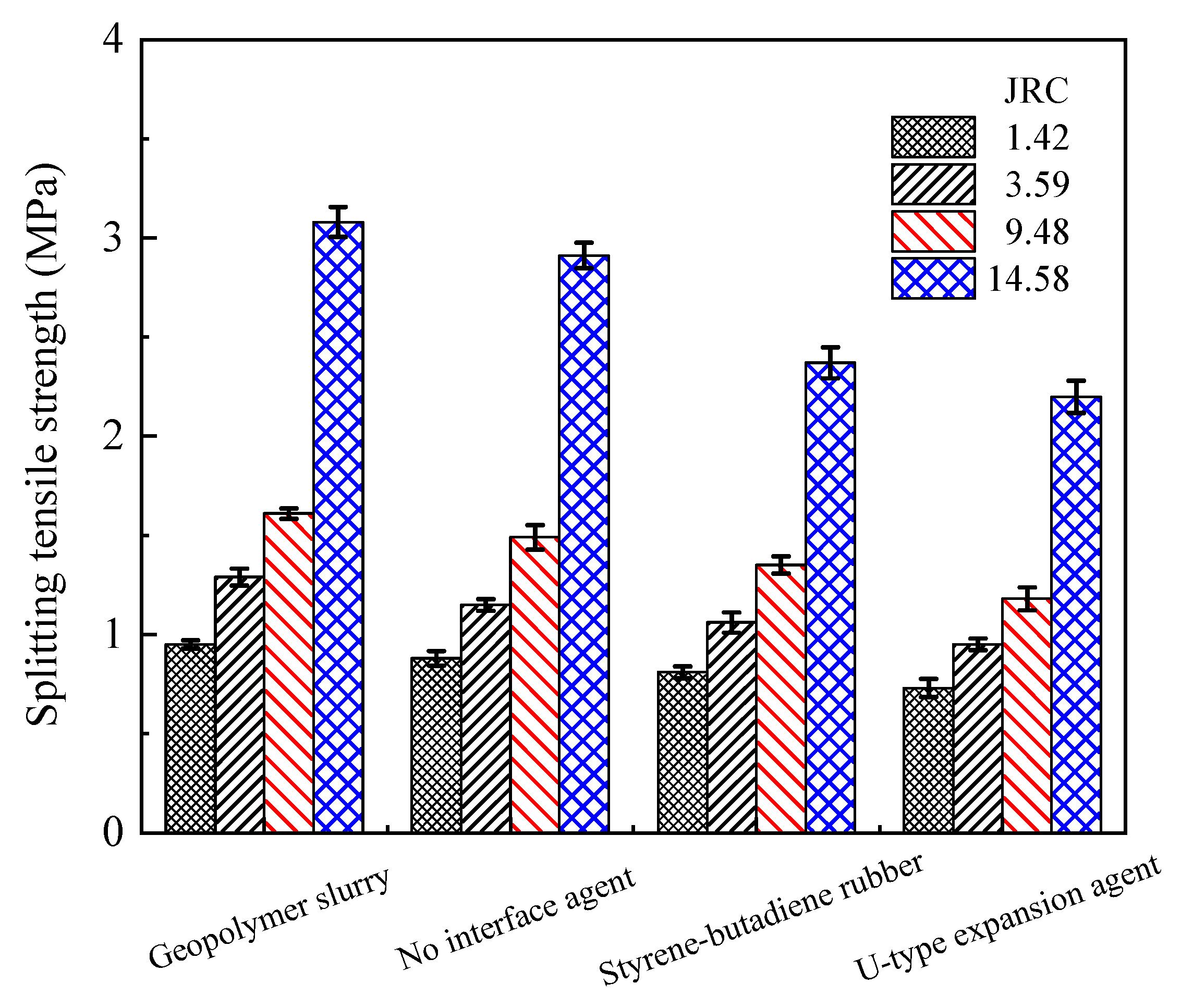

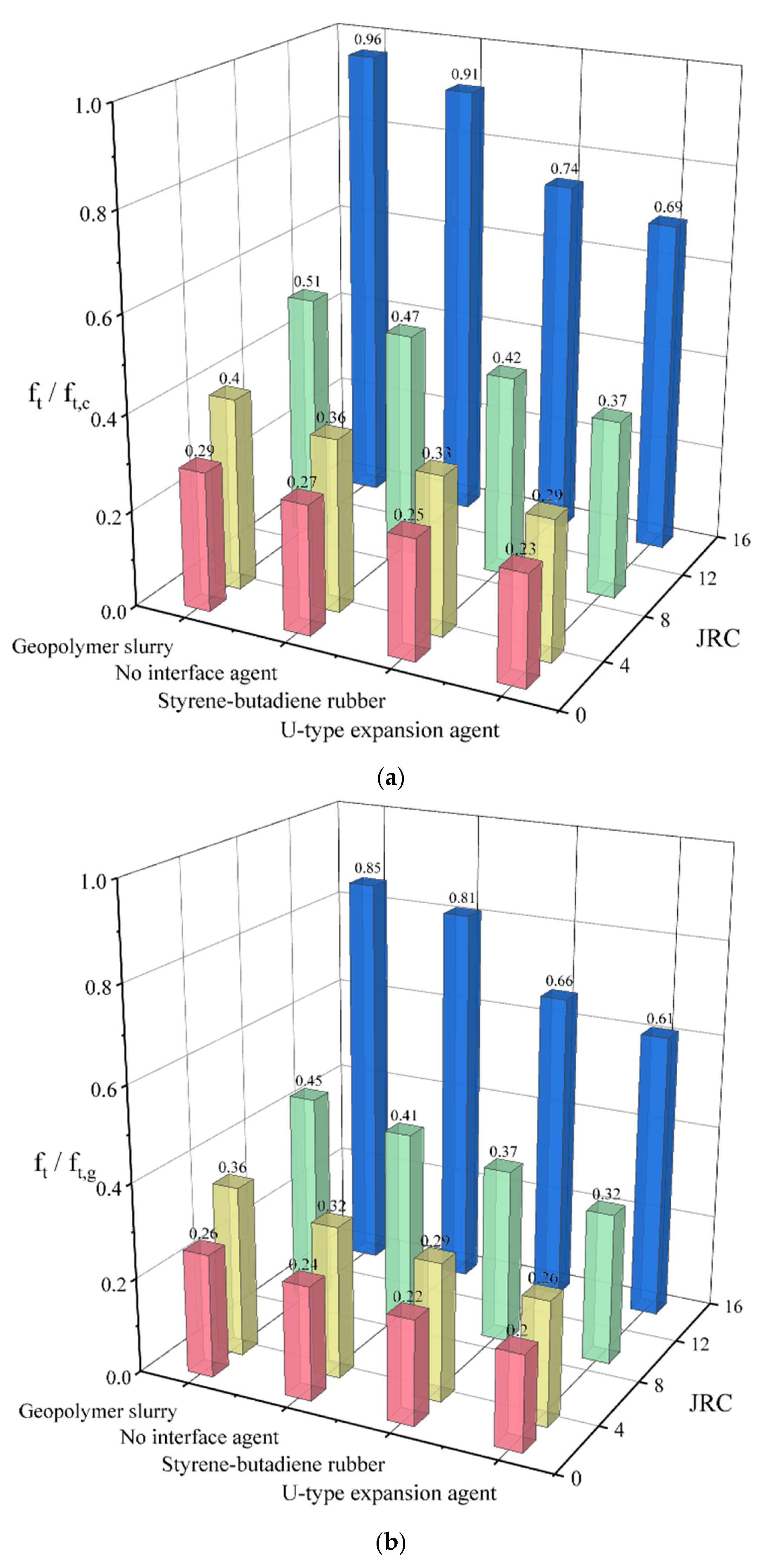

3.3. Effects of Interface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Splitting Tensile Strength

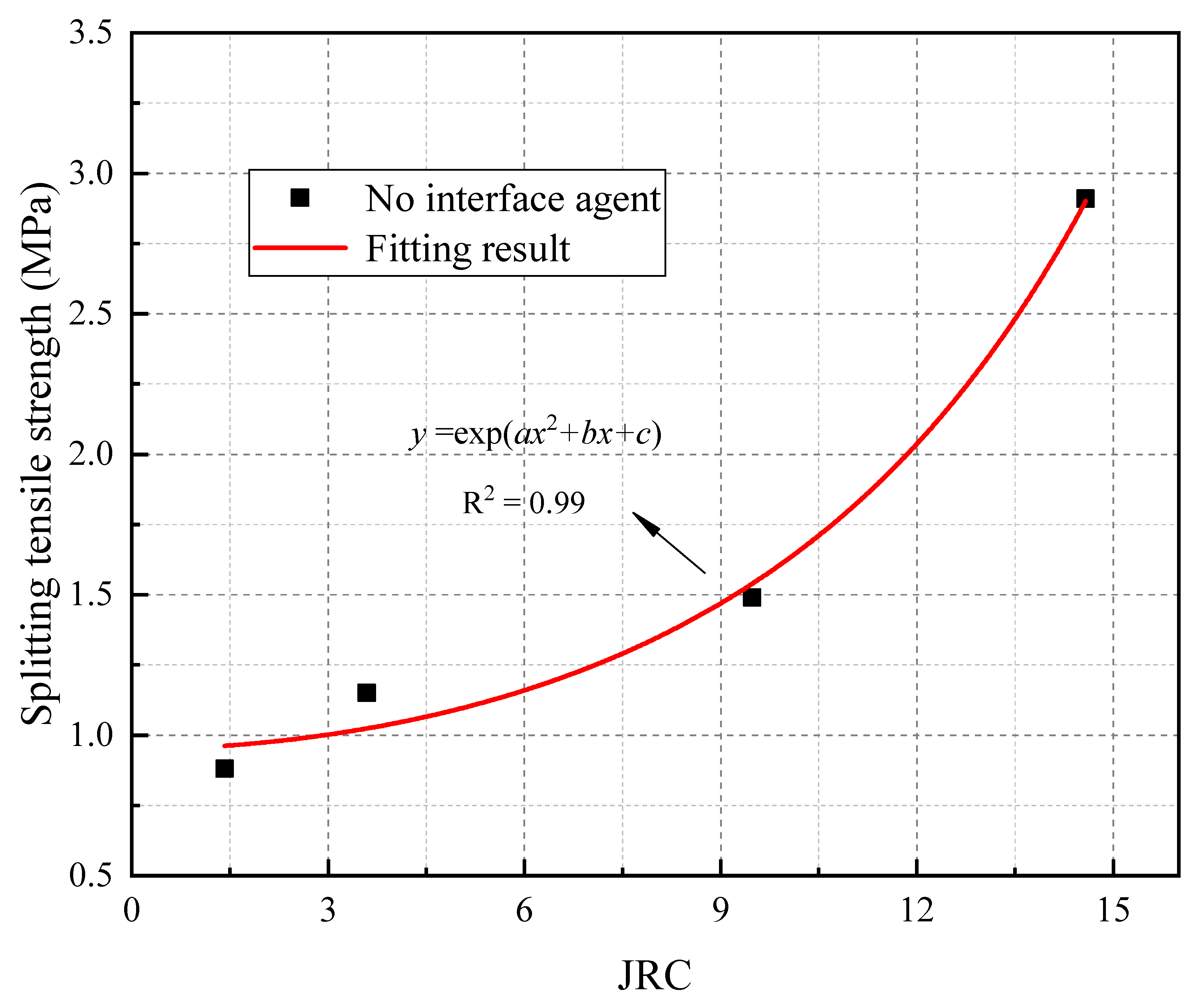

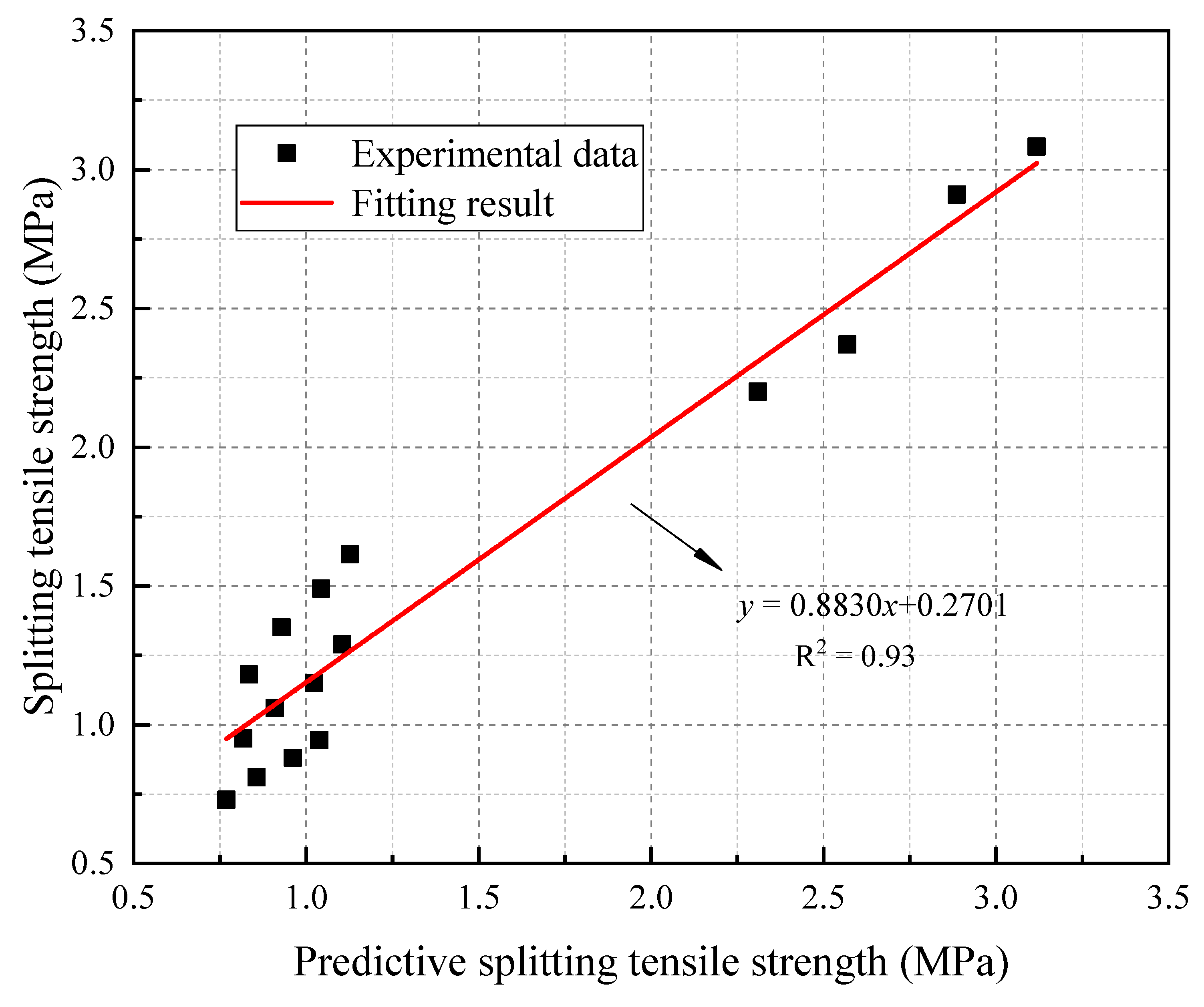

3.4. The Establishment of Bonding Strength Prediction Model

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- As the interface roughness (JRC) increased, the splitting tensile strength exhibited a corresponding upward trend, characterized by gradual growth followed by rapid growth. The splitting tensile strength of GCC specimens with split surfaces was approximately three times higher than that of those with cast surfaces. In practical engineering applications, concrete surfaces require chipping to achieve a degree of roughness approximating that of the split surfaces.

- (2)

- The interfacial agents ranked in descending order of their effect on splitting tensile strength were geopolymer paste, no interface agent, cement paste mixed with 10.0% styrene-butadiene rubber emulsion, and cement paste mixed with 10.0% U-type expansion agent. Geopolymer slurry can be used as an interface agent to concrete surfaces, which effectively enhances the bond strength between geopolymer concrete and old concrete.

- (3)

- Interface roughness significantly influenced the failure mode of GCC specimens. Increasing JRC values shifted the failure mode from interfacial bonding failure to splitting tensile failure within both concrete types.

- (4)

- A empirical formula for calculating the splitting tensile strength of the interface between geopolymer concrete and cement concrete was developed, which can provide a scientific reference for the practical engineering application of geopolymer concrete as a repair material.

- (5)

- In actual structural repair projects, complex factors such as stress, shrinkage, and temperature gradients significantly influence the bonding performance between geopolymers and concrete. Future research may further explore the long-term durability of geopolymer–concrete composite structures under complex service conditions, alongside the degradation mechanisms of their microstructures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, G.; Niu, D.T.; Hu, X.P.; Pan, B.X.; Zhong, S. Experimental study of the interfacial bond strength between cementitious grout and normal concrete substrate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 122057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xiao, H.G.; Liu, M.; Zhang, F.L.; Lu, M.Y. Shear behaviour of interface between normal-strength concrete and UHPC: Experiment and predictive model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Cui, S.A.; Cao, Z.Y.; Zhang, S.H.; Ju, J.W.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.W. Study on the interfacial bonding performance of basalt ultra-high performance concrete repair and reinforcement materials under severe service environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, H.; Muhamad, R.; Visintin, P.; Shuki, A.A. Mechanical properties and bond stress-slip behaviour of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zou, X.W.; Yang, L.; Wang, P.; Niu, M.D. Influence of humidity on the mechanical properties of polymer-modified cement-based repair materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, M.M.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Dulaijan, S.U.; Ibrahim, M. Mechanical properties and durability characteristics of polymer- and cement-based repair materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C. A study on the mix proportion of fiber-polymer composite reinforced cement-based grouting material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 328, 127025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, F.; Luccion, B.; Ruano, G.; Torrijos, M.C.; Morea, F.; Giaccio, G.; Zerbino, R. Mechanical response of fiber reinforced concrete overlays over asphalt concrete substrate: Experimental results and numerical simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, F.; Roviello, G.; Ricciotti, L.; Ferrándiz-Mas, V.; Messina, F.; Ferone, C.; Tarallo, O.; Cioffi, R.; Cheeseman, C.R. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 86, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.U.A.; Fairchild, A.; Zammar, R. Comparative strain and deflection hardening behaviour of polyethylene fibre reinforced ambient air and heat cured geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mashhadani, M.M.; Canpolat, O.; Aygormez, Y.; Uysal, M.; Erdem, S. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of fiber reinforced fly ash based geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, C.; Borges, P.H.R.; Bhutta, A.; Banthia, N. Bond strength between concrete substrate and metakaolin geopolymer repair mortar: Effect of curing regime and PVA fiber reinforcement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 80, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, H.; Yang, M.J.; Zhang, D.L.; Gao, Z.L. Bond strength of PCC pavement repairs using metakaolin-based geopolymer mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 65, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, R.L.; Chen, F.Z.; Jia, X.C.; Cong, P.T. Effects of Reactive MgO on the Reaction Process of Geopolymer. Materials 2019, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Fan, L.F. High-ductile engineered geopolymer composites (EGC) prepared by calcined natural clay. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Fan, L.F.; Li, P.F. Effect of PDMS content on waterproofing and mechanical properties of geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 26248–26257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.C.; Zhu, H.G.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.H.; Yang, S. Influence of slag content on the bond strength, chloride penetration resistance, and interface phase evolution of concrete repaired with alkali activated slag/fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.C.; Zhang, B. Repair of ordinary Portland cement concrete using alkali activated slag/fly ash: Freeze-thaw resistance and pore size evolution of adhesive interface. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 124334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.S.; Luo, R.; Qin, L.L.; Liu, H.; Duan, P.; Jing, W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Liu, X.H. High temperature properties of graphene oxide modified metakaolin based geopolymer paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 125, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Das, C.S.; Lao, J.C.; Alrefaei, Y.; Dai, J.G. Effect of sand content on bond performance of engineered geopolymer composites (EGC) repair material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 328, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albidah, A.; Alghannam, M.; Abbas, H.; Almusallam, T.; Al-Salloum, Y. Characteristics of metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete for different mix design parameters. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouhet, R.; Cyr, M. Formulation and performance of flash metakaolin geopolymer concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Peng, K.D.; Alrefaei, Y.; Dai, J.G. The bond between geopolymer repair mortars and OPC concrete substrate: Strength and microscopic interactions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yin, J. A review on microscopic property of concrete’s aggregate-mortar interface transition zone. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 847, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zhu, Z.M.; Wang, M.; Wang, F.; Luo, C.S.; Wan, D.Y. Study of the failure properties and tensile strength of rock-mortar interface transition zone using bi-material Brazilian discs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granrut, M.D.; Simon, A.; Dias, D. Artificial neural networks for the interpretation of piezometric levels at the rock-concrete interface of arch dams. Eng. Struct. 2019, 178, 616–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xiao, H.G.; Li, H. Comparative studies of the effect of ultrahigh-performance concrete and normal concrete as repair materials on interfacial bond properties and microstructure. Eng. Struct. 2020, 222, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Liao, Z.Q.; Wang, L.H. Interfacial bond properties between normal strength concrete substrate and ultra-high performance concrete as a repair material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Sun, Q.S.; Li, J.F.; Liu, Y.C.; Sun, H.P.; Zhang, C. Experimental study on the shear performance of the bonding interface between geopolymer concrete and cement concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanbay, Y.G.; Aslanbay, H.H.; Özbayrak, A.; Kucukgoncu, H.; Astas, O. Comprehensive analysis of experimental and numerical results of bond strength and mechanical properties of fly ash based GPC and OPC concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Su, L.W.; Mai, Z.H.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.M.; Li, J.L.; Xie, J.H. Bond durability between geopolymer-based CFRP composite and OPC concrete substrate in seawater environments. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 93, 109817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P.; De la Varga, I.; Munoz, J.F.; Spragg, R.P.; Graybeal, B.A.; Hussey, D.S.; Jacobson, D.L.; Jones, S.Z.; LaManna, J.M. Influence of substrate moisture state and roughness on interface microstructure and bond strength: Slant shear vs. pull-off testing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 87, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.S.; Santos, P.M.D.; Dias-da-Costa, D. Effect of surface preparation and bonding agent on the concrete-to-concrete interface strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah, S.H.A.; Hassan, M.H.; Bunnori, N.M.; Johari, M.A.M. Bond strength of the interface between normal concrete substrate and GUSMRC repair material overlay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 216, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, T.A. Research on the dynamic response and failure characteristics of concrete-granite specimens with varied interface roughness. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04022407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Luo, T.; Zhang, H. Influence of surface roughness and hydrophilicity on bonding strength of concrete-rock interface. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 213, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courard, L.; Piotrowski, T.; Garbacz, A. Near-to-surface properties affecting bond strength in concrete repair. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Ahmad, M.; Ueda, T.; Deng, J.; Aslam, K.; Nazir, I.; Sarwar, M.A. Experimental investigation of the bond strength between new to old concrete using different adhesive layers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basar, G.; Der, O.; Guvenc, M.A. AI-powered hybrid metaheuristic optimization for predicting surface roughness and kerf width in CO2 laser cutting of 3D-printed PLA-CF composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. 2025, 38, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.H.; Ren, W.X.; Dai, H.Q.; Zhu, X.L. Investigations on electromagnetic wave scattering simulation from rough surface: Some instructions for surface roughness measurement based on machine vison. Precis. Eng. 2023, 82, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 18046-2008; Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag Used for Cement and Concrete. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 50082-2024; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Concrete. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of PRC: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Singh, M.; Goswami, J.; Santra, R. Effect of Styrene Butadiene Ratio on Mechanical Properties of Concrete Mixture. Polym-Plast. Technol. 2012, 51, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, J.J.; Gerges, N. Styrene-butadiene rubber modified cementitious grouts for embedding anchors in humid environments. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, C.; Shui, Z.H.; Yu, R. Effects of expansive additives on the shrinkage behavior of coal gangue based alkali activated materials. Crystals 2021, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Deng, J.J.; Cheng, B.Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, B.J. New anticracking glass-fiber-reinforced cement material and integrated composite technology with lightweight concrete panels. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 7447066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.L.; Sun, Y.H.; Zhao, X.; Fan, L.F. Study on synthesis and water stability of geopolymer pavement base materials using waste sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, R.; Zheng, J.H.; Li, J.W.; Hui, C.; Liu, J.X. Preparation mechanism and properties of thermal activated red mud and its geopolymer repair mortar. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xue, C.; Jia, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y. Preparation and curing method of red mud-calcium carbide slag synergistically activated fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based eco-friendly geopolymer. Cem. Con. Compos. 2023, 139, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.S.; Su, Y.P.; Luo, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.H.; Hu, R.H. Preparation and performance optimization of fly ash- slag- red mud based geopolymer mortar: Simplex-centroid experimental design method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, R.; Cruden, D. Estimating joint roughness coefficient. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1979, 16, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Ummin, O.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Jia, H.Y.; Zuo, J. Influence of surface roughness and interfacial agent on the interface bonding characteristics of polyurethane concrete and cement concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chai, J.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Wang, R.J.; Yuan, Q.; Cao, Z.L. Experimental investigation of the interfacial bonding properties between polyurethane mortar and concrete under different influencing factors. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, D.; Behnood, A.; Robisson, A. Interfacial bond in concrete-to-concrete composites: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 1291995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.M.; Julio, E.N. Correlation between concrete-to-concrete bond strength and the roughness of the substrate surface. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Júlio, E. Development of a laser roughness analyser to predict in situ the bond strength of concrete-to-concrete interfaces. Mag. Concr. Res. 2008, 60, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, Z.W.; Wang, D.H. Influence of interface agent and form on the bonding performance and impermeability of ordinary concrete repaired with alkali-activated slag cementitious material. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 110043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zou, H.N.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, J.Y. Interface bonding properties of new and old concrete: A review. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1389785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.X.; Guo, R.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Fu, C.S.; Wan, F.X.; Pan, T.H. Effects of interface agent and cooling methods on the interfacial bonding performance of engineered cementitious composites (ECC) and existing concrete exposed to high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 376, 131054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hooton, R.D.; Zhang, X.W. Effects of interface roughness and interface adhesion on new-to-old concrete bonding. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.B.; Fu, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N. Study on splitting tensile strength of interface between the full lightweight ceramsite concrete and ordinary concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yuan, Y.J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Z.C. Bond behavior between lightweight aggregate concrete and normal weight concrete based on splitting-tensile test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CaO (%) | SiO2 (%) | Al2O3 (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | MgO (%) | SO3 (%) | Cl− (%) | Others (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51.42 | 24.99 | 8.26 | 4.03 | 3.71 | 2.51 | 0.04 | 5.04 |

| Material | Cement (kg/m3) | Metakaolin (kg/m3) | Slag (kg/m3) | Gravel (kg/m3) | Sand (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) | Activator (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement concrete | 425.2 | - | - | 1301.1 | 586.7 | 187.1 | - |

| Geopolymer concrete | - | 212.5 | 212.5 | 1300.0 | 650.0 | - | 300.1 |

| Coefficient a | Coefficient b | Coefficient c |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0050 | 0.0035 | −0.0540 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, B.; Chen, D.; Zhong, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L. Effects of Surface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Bond Performance of Geopolymer–Concrete Composites. Buildings 2025, 15, 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244446

Lu B, Chen D, Zhong W, Li J, Zhang Y, Fan L. Effects of Surface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Bond Performance of Geopolymer–Concrete Composites. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244446

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Biao, Dekun Chen, Weiliang Zhong, Junxia Li, Yunhan Zhang, and Lifeng Fan. 2025. "Effects of Surface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Bond Performance of Geopolymer–Concrete Composites" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244446

APA StyleLu, B., Chen, D., Zhong, W., Li, J., Zhang, Y., & Fan, L. (2025). Effects of Surface Roughness and Interfacial Agents on Bond Performance of Geopolymer–Concrete Composites. Buildings, 15(24), 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244446