Seismic Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Arch Bridges Considering Component Correlation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Seismic Reliability Analysis

2.1. Seismic Hazard Analysis

2.2. Seismic Vulnerability Analysis

3. Vine Copula Theory

3.1. Pair-Copula Functions

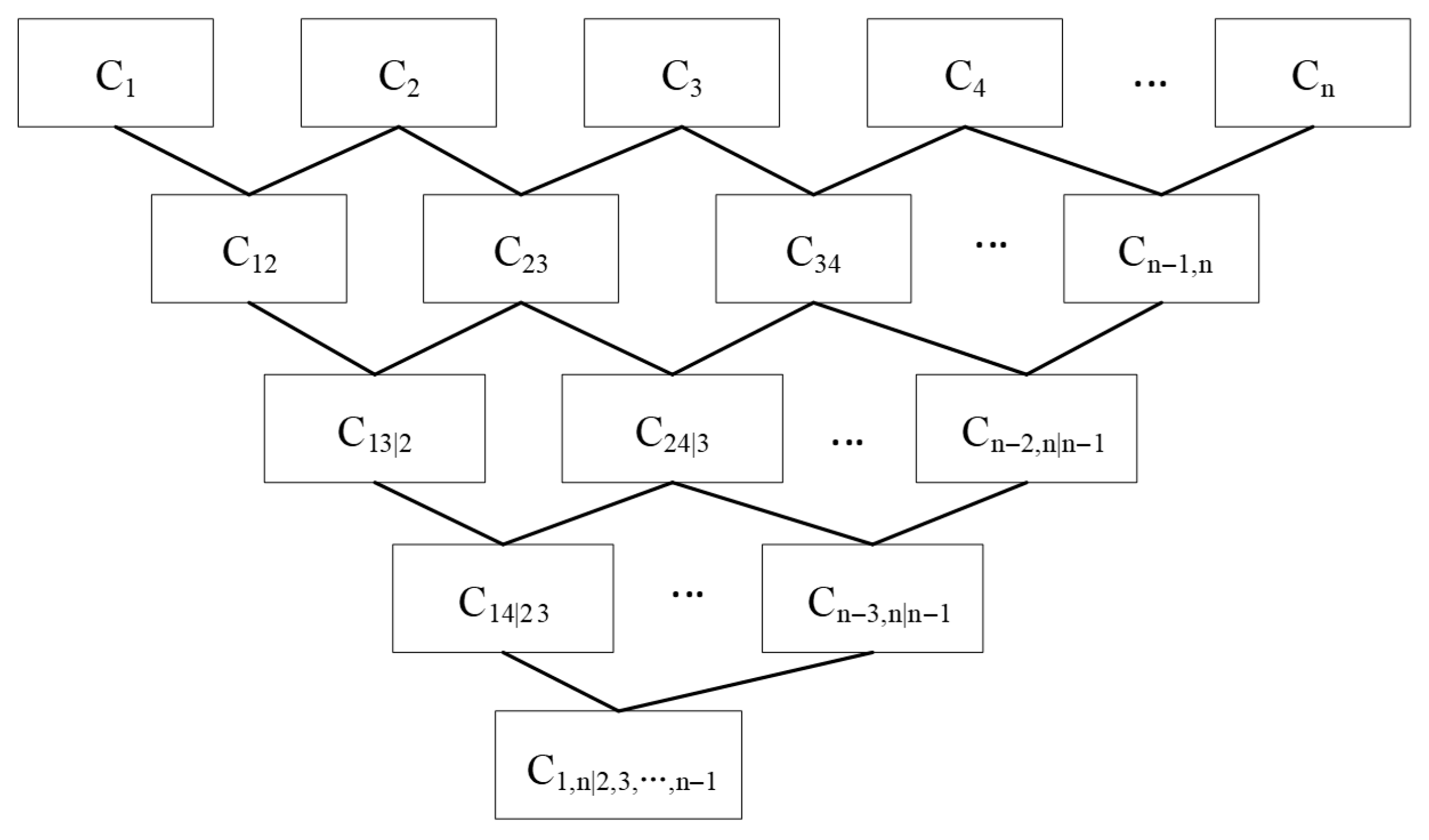

3.2. Vine Copula

3.3. Determining the Optimal Pair-Copula Function

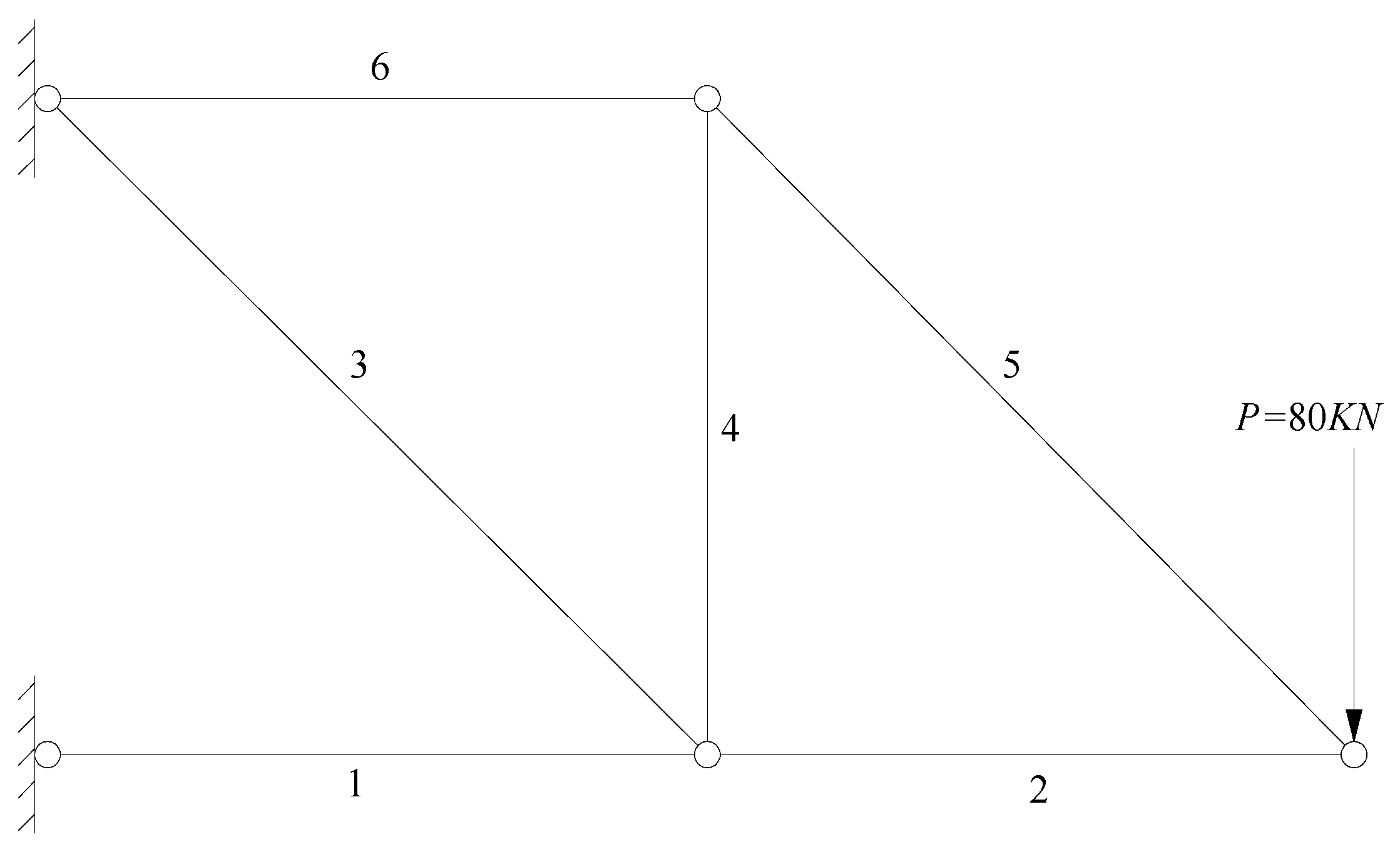

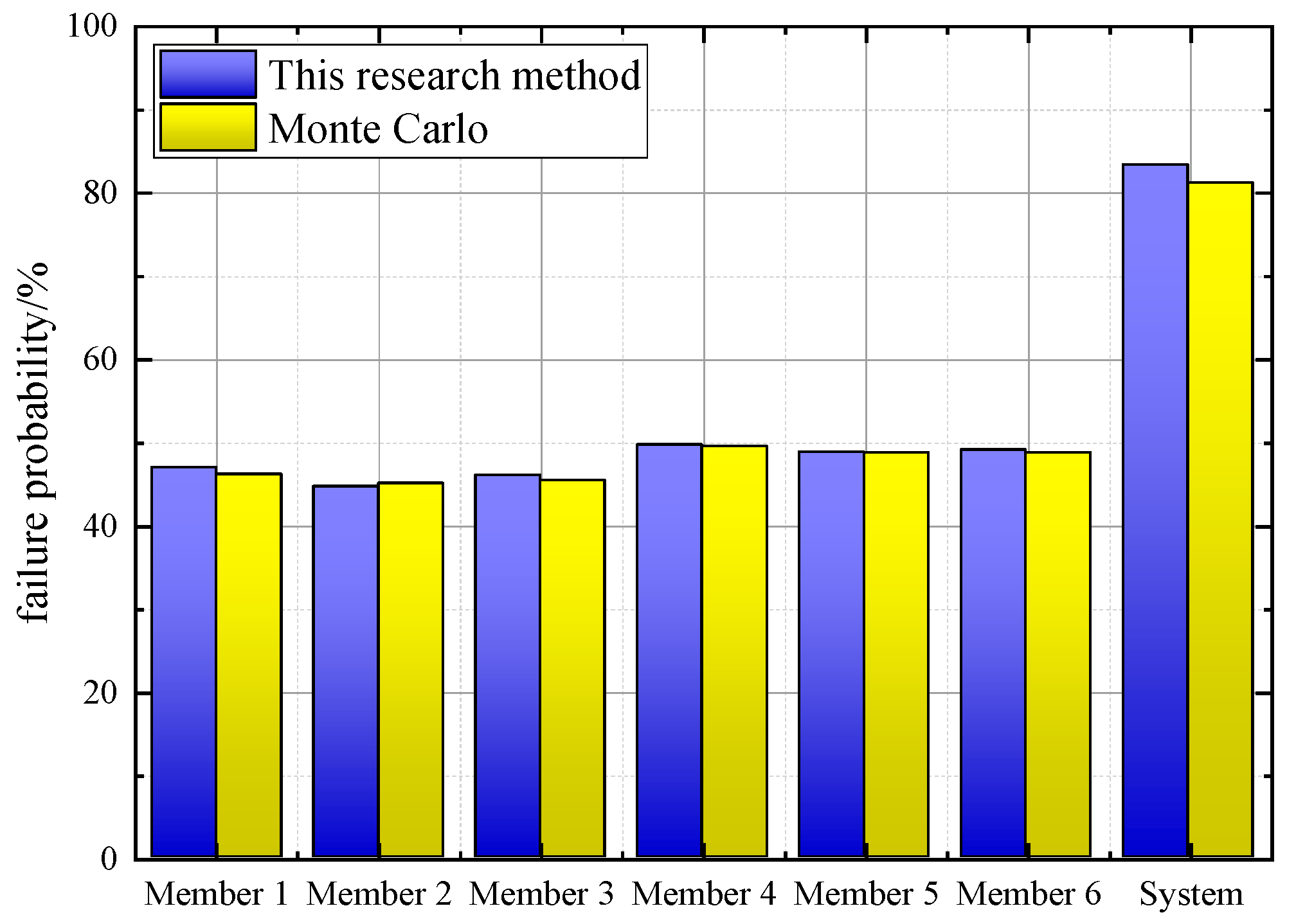

4. Example Verification

5. Engineering Example

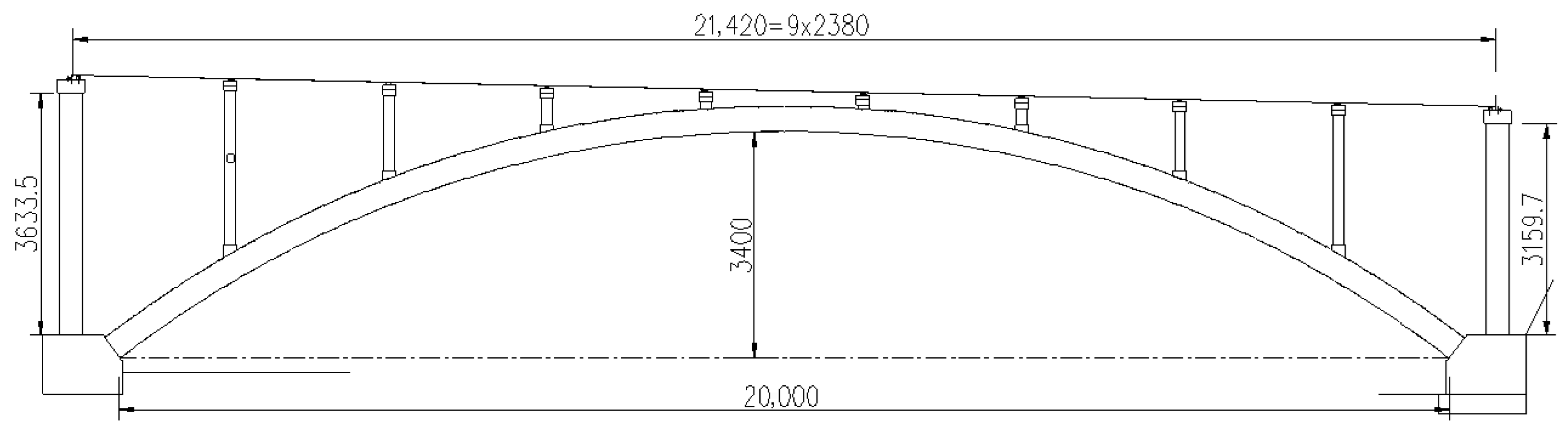

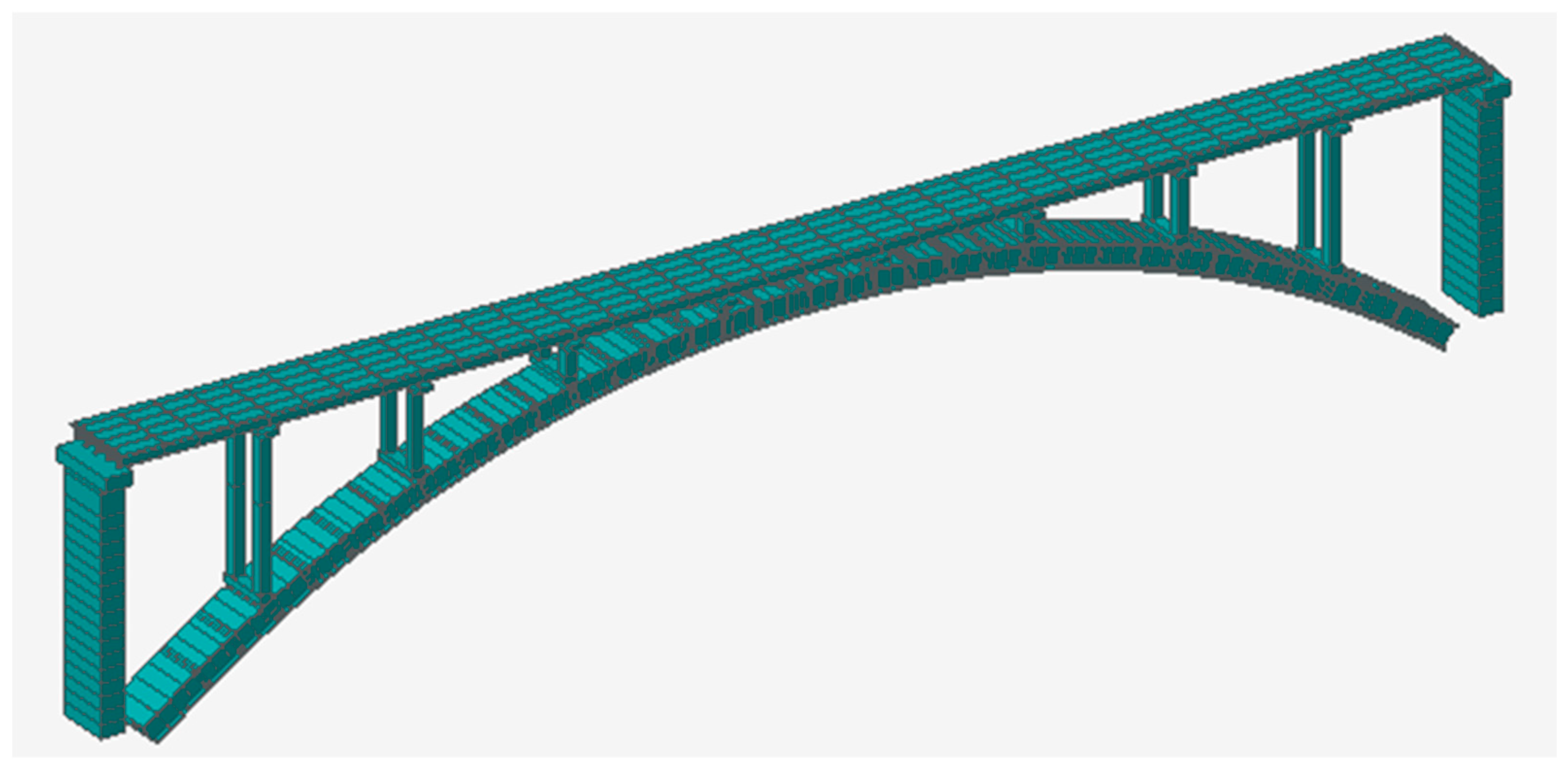

5.1. Engineering Background

5.2. Uncertainty Analysis

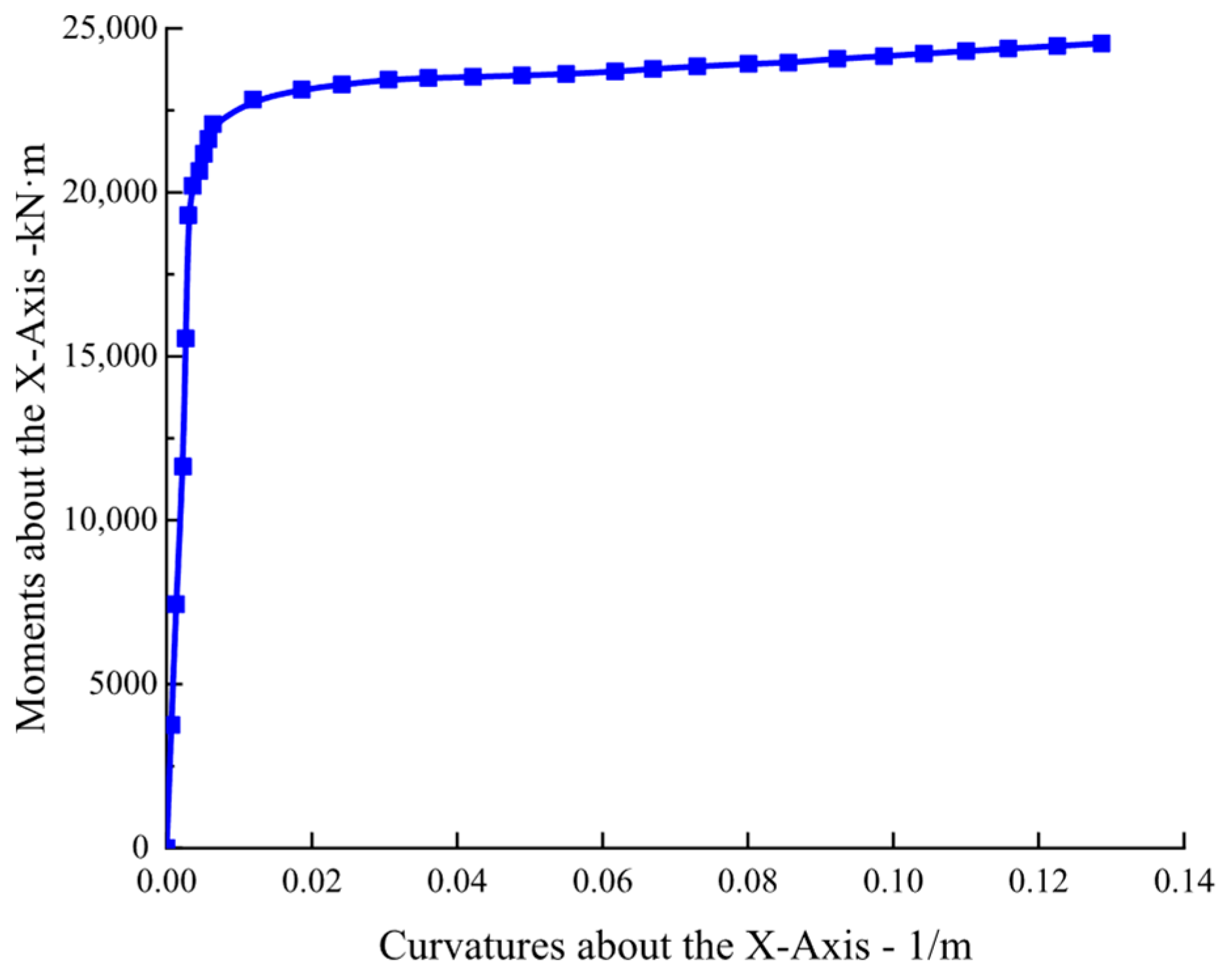

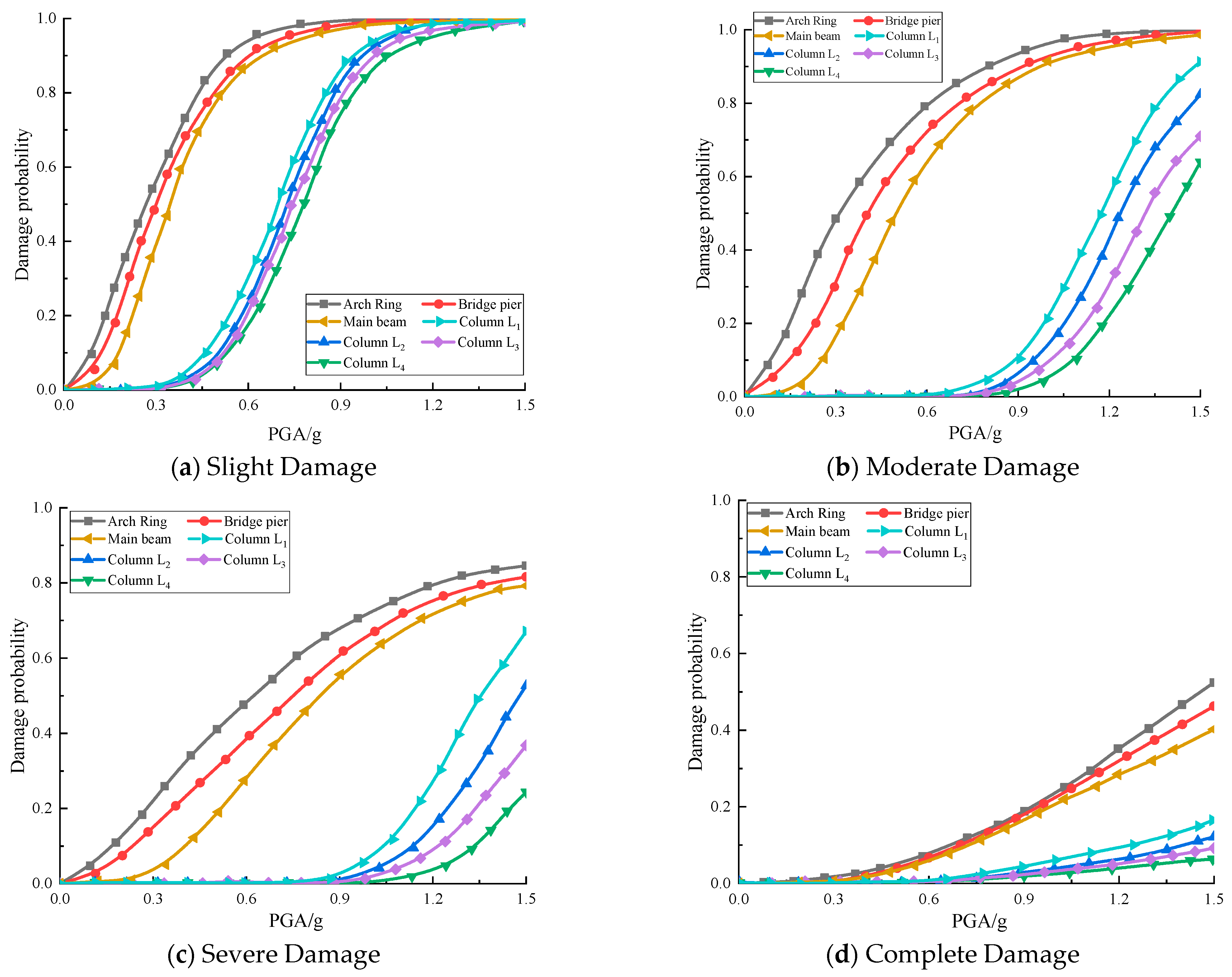

5.3. Component Seismic Vulnerability Analysis

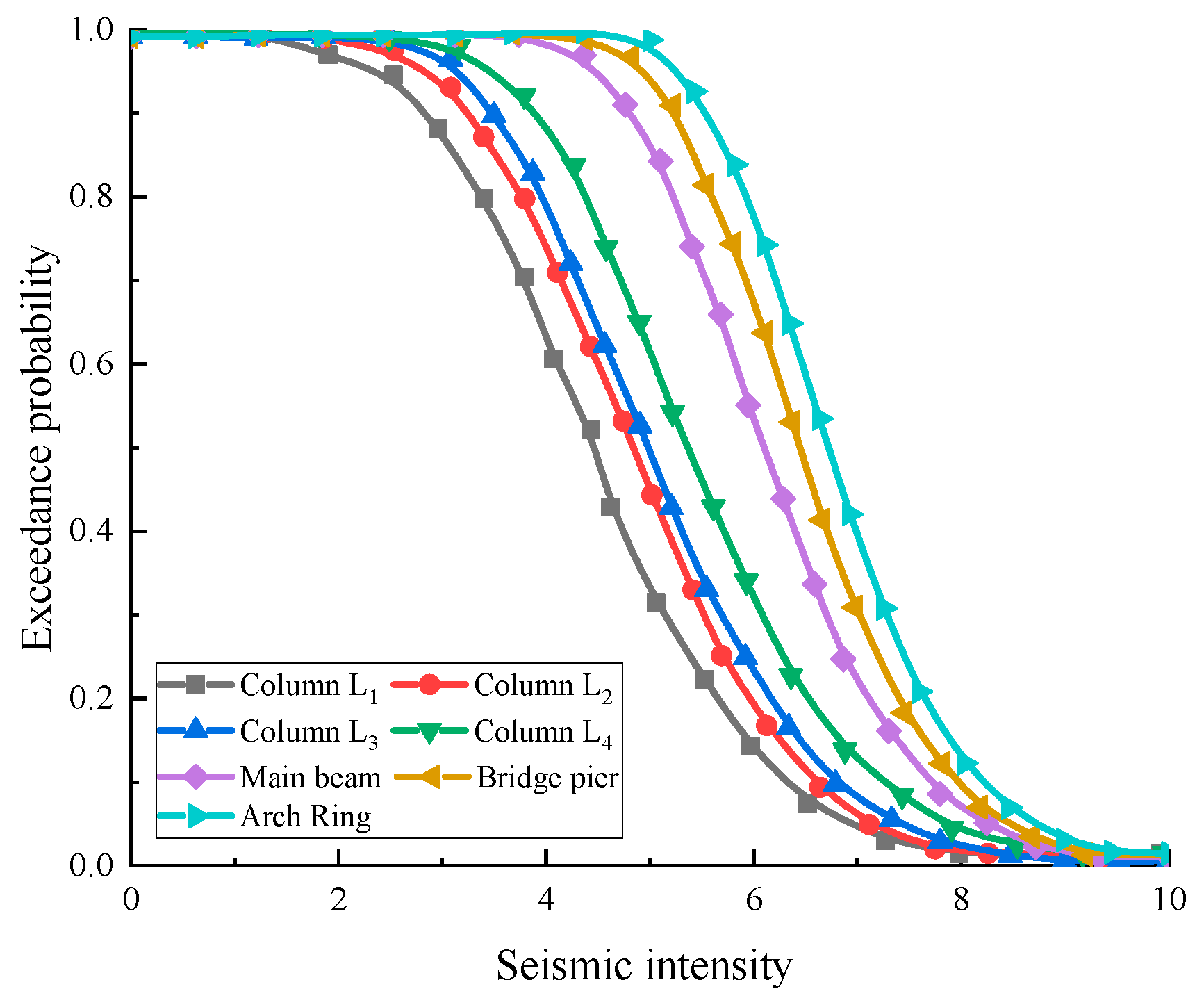

5.4. Component Seismic Hazard Analysis

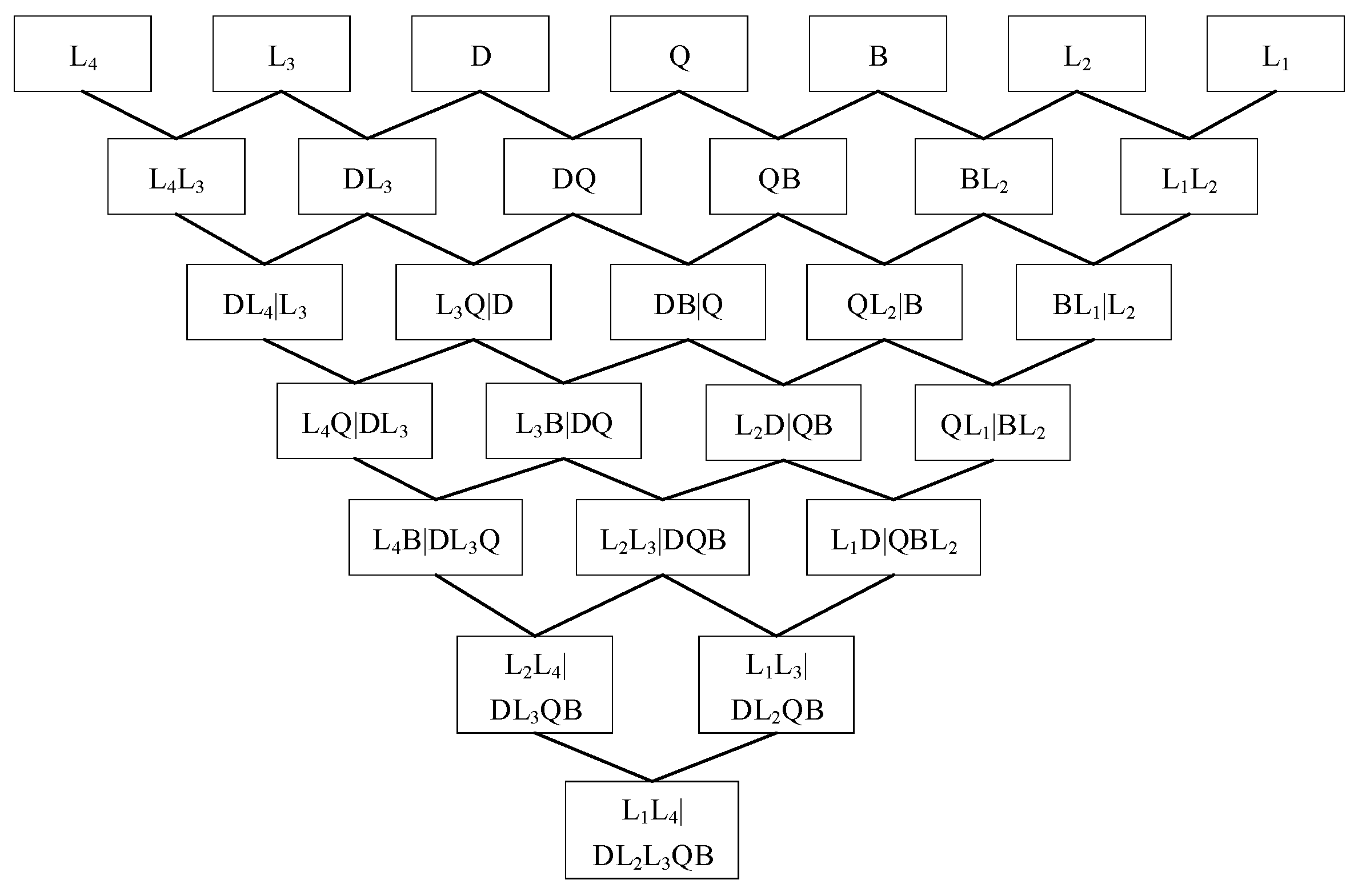

5.5. System Seismic Reliability Analysis

5.6. Parametric Sensitivity and Generality Analysis

- (1)

- Arch Axis Coefficient (m): 1.75, 1.85 (baseline), 1.95.

- (2)

- Rise-to-Span Ratio: 1/5.0, 1/5.882 (baseline), 1/6.5.

- (3)

- Concrete Grade for Arch Ring: C50, C55 (baseline), C60.

- (4)

- Site Condition (affecting selected ground motions): Site Class II, Site Class III (baseline), Site Class IV.

6. Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under the same damage state, the damage probability of the arch ring is always the highest, followed by the piers and main girder, while the overall damage probability of all columns is the lowest, with their complete failure probability almost zero. Comparing the vulnerability of similar components at different positions shows that under the same conditions, column L1 is relatively more prone to failure.

- (2)

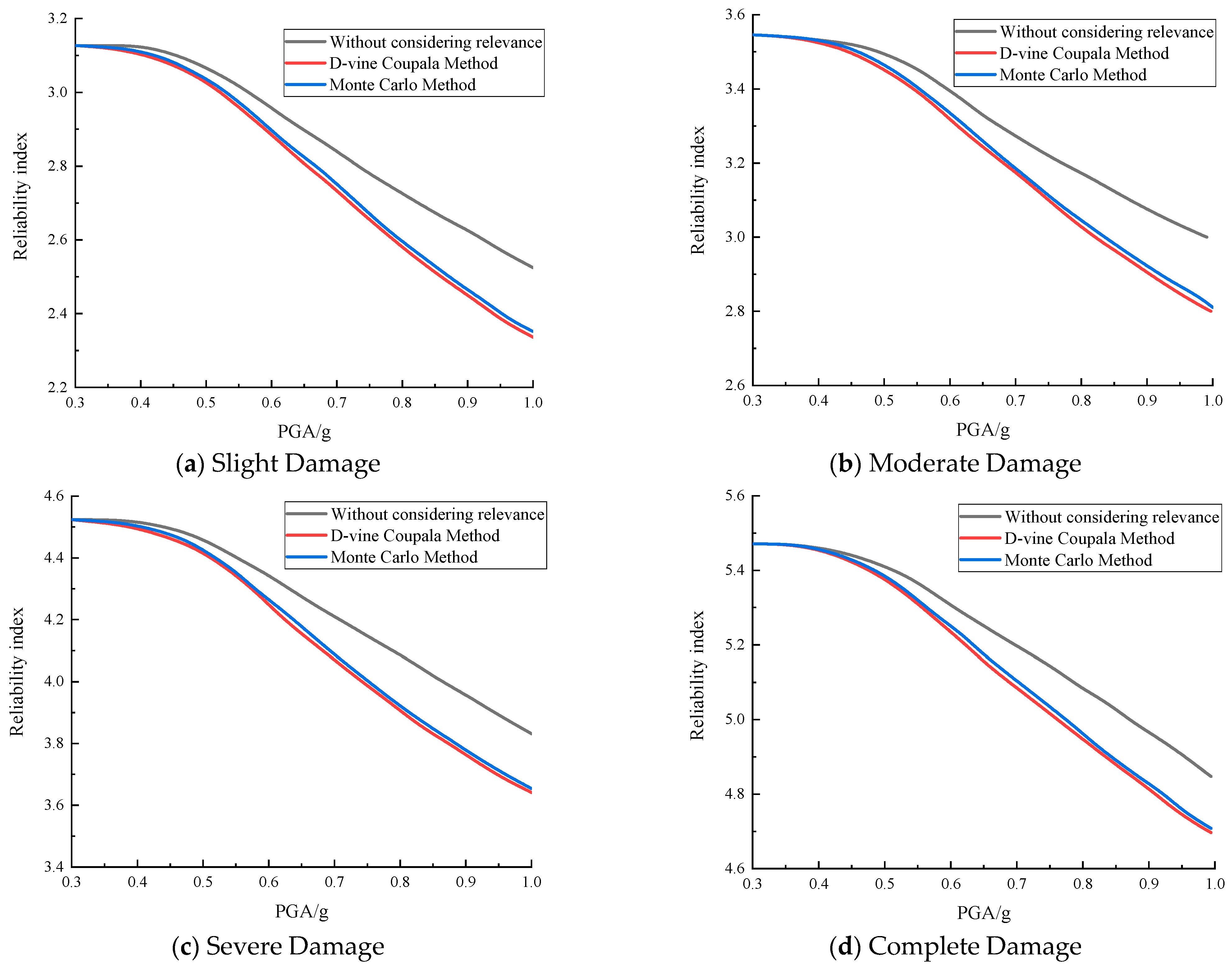

- When component correlation is considered, the seismic reliability indices of the reinforced concrete arch bridge system under minor, moderate, severe damage, and complete failure states are all lower than those ignoring correlation, indicating that component correlation significantly affects system seismic reliability. Ignoring correlation leads to an overestimation of the system’s seismic performance.

- (3)

- The system seismic reliability obtained by the D-vine Copula method and the Monte Carlo method differs slightly, with a maximum relative error not exceeding 2.26%, verifying the applicability and accuracy of the D-vine Copula method in the reliability analysis of complex structural systems.

- (4)

- The proposed method effectively captures the nonlinear correlation characteristics between components by constructing an accurate joint probability distribution model. Compared to the traditional Monte Carlo simulation, which requires large-scale repeated sampling, the D-vine Copula method significantly reduces computational complexity through analytical derivation, improving computational efficiency by over 80%.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

- (1)

- The uncertainty quantification in this study focuses on key material, geometric, and ground motion intensity parameters, which are sampled independently. Correlations among these input variables (e.g., between concrete strengths in different components) are not considered, which is a common simplification in such system-level analyses; incorporating them remains a topic for future research. Furthermore, structural damping is treated as deterministic, and soil–structure interaction effects are not explicitly modeled, with foundations assumed fixed. These assumptions are consistent with the design basis of the case-study bridge, founded on competent rock. While these choices keep the current analysis focused and tractable for illustrating the novel component-correlation framework, future work could explore the influence of these additional uncertainties and interactions on the system reliability of arch bridges.

- (2)

- The proposed D-vine Copula framework provides an analytical model for system reliability that considers component correlations. Future research could explore the synergy between this type of model and data from structural health monitoring systems [32]. For example, monitoring data from in-service RC arch bridges [33] could be used to calibrate or validate the correlation parameters within the Copula model, moving towards a more empirically grounded and continuously updated reliability assessment paradigm.

- (3)

- This work establishes a foundation for several promising extensions. First, the framework could be enhanced by incorporating non-stationary ground motion models to better represent the spectral characteristics of near-fault or long-duration earthquakes. Second, a powerful synergy could be achieved by integrating the proposed Copula-based joint failure probability model with Bayesian updating techniques. Finally, investigating the correlation between material/geometric uncertainties (inputs) and the resulting performance correlations (outputs) remains an important area for refining the overall uncertainty quantification.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. Probabilistic seismic performance assessment of urban traffic network incorporating micro inter-connection model of interchanges. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, X. Research on the cross-sectional geometric parameters and rigid skeleton length of reinforced concrete arch bridges: A case study of Yelanghu Bridge. Structures 2024, 69, 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygılı, Ö.; Lemos, J.V. Seismic vulnerability assessment of masonry arch bridges. Structures 2021, 33, 3311–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, B. Structure reactions and train running safety on CFST arch bridges under different kinds of near-fault earthquakes. Structures 2024, 70, 70107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Y. Failure Probability-Based Dynamic Instability Evaluation of the Long Span Steel Arch Bridge Subjected to Earthquake Excitations. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2023, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.J.; Chen, S.Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.L.; Ning, Y.H. Analysis of Seismic Vulnerability of Concrete-filled Steel Tube Arch Bridges under Scouring. Highw. Eng. 2022, 47, 40–46+112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytulun, E.; Soyoz, S.; Karcioglu, E. System identification and seismic performance assessment of a stone arch bridge. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Jahangiri, V.; Marefat, M.S. Seismic performance assessment of plain concrete arch bridges under near-field earthquakes using incremental dynamic analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 106, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-T.; Ahn, J.-H.; Haldar, A.; Huh, J. Fragility-based seismic performance assessment of modular underground arch bridges. Structures 2022, 39, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Yan, G.; Yang, H.; Zhao, C. RC arch bridge seismic performance evaluation by sectional NM interaction and coupling effect of brace beams. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.S.; Yang, H.P.; Qian, Y.J. Seismic vulnerability analysis of reinforced concrete arch bridge pile foundation considering scour effect. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2023, 45, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, J.; Aparicio, A.; Jara, J.; Jara, M. Seismic assessment of a long-span arch bridge considering the variation in axial forces induced by earthquakes. Eng. Struct. 2012, 34, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Impact of component damage correlations on seismic fragility and risk assessment of multi-component bridge systems. Struct. Saf. 2025, 117, 102635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.S.; Yuan, Y. Random seismic response and seismic reliability analysis of bar-system arch bridges. Highw. Eng. 2020, 45, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidinia, M.; Haghiabi, A.H.; Tahroudi, M.N.; Nasrolahi, A.; De Michele, C. Deep learning and vine copula-based sequencing: Approaches under investigation for forecasting soil temperature dynamics. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 4949–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Taveira-Pinto, F.; Romão, X.; Reis, M.; das Neves, L. Reliability assessment of offshore dynamic scour protections using copulas. Wind Eng. 2019, 43, 506–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.; Nogal, M.; O’cOnnor, A.; Martinez-Pastor, B. Reliability assessment with density scanned adaptive Kriging. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 199, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sio, C.; Azimi, S.; Sterpone, L. FireNN: Neural networks reliability evaluation on hybrid platforms. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2022, 10, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, C.A.; Jalayer, F.; Hamburger, R.O.; Foutch, D.A. Probabilistic basis for 2000 SAC federal emergency management agency steel moment frame guidelines. J. Struct. Eng. 2002, 128, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C. Research on Seismic Vulnerability and Seismic Strengthening Strategies of Bridges Considering Chloride Ion Erosion. Ph.D. thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. Earthquake Engineering; Seismological Press: Beijing, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- GB 18306-2015; Seismic Ground Motion Parameters Zonation Map of China. The General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (AQSIQ) and the Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2015.

- Aas, K.; Czado, C.; Frigessi, A. Pair-copula constructions of multiple dependence. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Xu, Y.L.; Li, Y. Optimized C-vine copula and environmental contour of joint wind-wave environment for sea-crossing bridges. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 225, 104989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Peng, M.-Y.; Yang, Z.-Y. System reliability analysis of Cable-stayed bridge using pair Copula and ICLHS with unequal weights under seismic loading. Structures 2024, 64, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, S. Reliability assessment framework of the long-span cable-stayed bridge and traffic system subjected to cable breakage events. J. Bridge Eng. 2017, 22, 04016133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Lei, Y.; Liu, L.J. Efficient Moment-Independent Sensitivity Analysis of Uncertainties in Seismic Demand of Bridges Based on a Novel Four-Point-Estimate Method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Cao, Q.; He, H.; Cheng, Y. Global seismic vulnerability analysis of continuous girder bridges based on multivariate Copula function. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2022, 48, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgnia, Y.; Abrahamson, N.A.; Al Atik, L.; Ancheta, T.D.; Atkinson, G.M.; Baker, J.W.; Baltay, A.; Boore, D.M.; Campbell, K.W.; Chiou, B.S.-J.; et al. NGA-West2 research project. Earthq. Spectra 2014, 30, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, Y.K.; Guo, Y. Time-dependent seismic fragility analysis of bridge systems under scour hazard and earthquake loads. Eng. Struct. 2016, 121, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; He, P.X. Time-dependent seismic fragility analysis of long-span arch bridges based on Kriging model. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 47, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, D.; Civera, M.; Surace, C. Bridge monitoring: Application of the extreme function theory for damage detection on the I-40 case study. Eng. Struct. 2023, 279, 115573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civera, M.; Massarelli, E.; Dalmasso, M.; Chiaia, B.; Ciavattone, A.; Del Monte, E.; Ambrosio, D.; Felluga, C.R.; Chessa, A.; Costantini, V.; et al. Bridge structural assessment and health monitoring: The case study of the iconic Corso Regina Margherita Bridge in Turin, Italy. In Proceedings of the IABSE Congress, Ghent 2025: The Essence of Structural Engineering for Society, Ghent, Belgium, 27–29 August 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Copula | Copula Function Expression c = (u1,u2;θ) | Generator φ(t) | Parameter Range θ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Copula | / | (−1, 1) | |

| Clayton Copula | (0, +∞) | ||

| Gumbel Copula | [1, +∞) | ||

| Frank Copula | (-∞, +∞)\{0} |

| Parameter Meaning | Probability Distribution | Mean | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Member elastic modulus/MPa | Normal distribution | 2 × 105 | 0.08 |

| Length of members 1, 2, 4, 6/mm | Normal distribution | 1 × 103 | 0.05 |

| Length of members 3, 5/mm | Normal distribution | 1.4 × 103 | 0.05 |

| Cross-sectional area of members 2, 4, 6/mm2 | Normal distribution | 1 × 104 | 0.05 |

| Cross-sectional area of members 1, 3, 5/mm2 | Normal distribution | 2 × 104 | 0.05 |

| Concentrated load/N | Normal distribution | 8 × 104 | 0.1 |

| Category | Parameter | Value/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Material Properties | C55 Concrete (Arch Ring) | fc = 55 MPa; E = 3.55 × 104 MPa; ν = 0.2; ρ = 2600 kg/m3 |

| C50 Concrete (Main Girder) | fc = 50 MPa; E = 3.45 × 104 MPa; ν = 0.2; ρ = 2600 kg/m3 | |

| C40 Concrete (Piers & Columns) | fc = 40 MPa; E = 3.30 × 104 MPa; ν = 0.2; ρ = 2600 kg/m3 | |

| Reinforcement Steel (HRB400) | Yield Strength fy = 400 MPa; E = 2.0 × 105 MPa | |

| Boundary Conditions | Arch Springings | Fully fixed |

| Pier Bases | Fully fixed | |

| Deck-Column Connections | Rigid connection (full moment transfer) | |

| Column-Arch Connections | Rigid connection | |

| Deck Expansion Joints | Released longitudinal translational DOF | |

| Primary Loads (Static) | Self-weight | Automatically calculated by software |

| Superimposed Dead Load | 80 kN/m uniformly distributed on the deck |

| Random Variable | Distribution Type | Mean | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| C55 concrete elastic modulus E1/MPa | Normal distribution | 3.55 × 104 | 0.10 |

| C50 concrete elastic modulus E2/MPa | Normal distribution | 3.45 × 104 | 0.10 |

| C40 concrete elastic modulus E3/MPa | Normal distribution | 3.3 × 104 | 0.10 |

| Arch rib cross-sectional area A1/m2 | Lognormal distribution | 0.6322 | 0.05 |

| Column cross-sectional area A2/m2 | Lognormal distribution | 1.7624 | 0.05 |

| Main girder cross-sectional area A3/m2 | Lognormal distribution | 4.2861 | 0.05 |

| Arch rib moment of inertia I1/m4 | Lognormal distribution | 0.02184 | 0.05 |

| Main girder moment of inertia I2/m4 | Lognormal distribution | 3.1347 | 0.05 |

| Damage State | Bridge Pier | Main Arch Ring | Columns | Main Beam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pier Curvature Ductility Ratio λ | Arch Ring Steel Strain ε1 | Arch Ring Steel Strain ε2 | Column Strain Ratio ε3 | Girder Moment–Curvature γ | |

| Slight Damage | λ ≤ 1.45 | ε1 ≤ 0.01 | ε2 ≤ 0.0035 | ε3 < 2.25 | γ < 0.0145 |

| Moderate Damage | 1.45 < λ ≤ 3.78 | 0.01 < ε1 ≤ 0.03 | 0.0035 < ε2 ≤ 0.0050 | 2.25 < ε3 < 2.5 | 0.0145 < γ < 0.0437 |

| Severe Damage | 3.78 < λ ≤ 12.59 | 0.03 < ε1 ≤ 0.05 | 0.0050 < ε2 ≤ 0.0080 | 2.5 < ε3 < 3.0 | 0.0437 < γ < 0.102 |

| Complete Damage | λ > 12.59 | ε1 > 0.05 | ε2 > 0.0080 | ε3 ≥ 3.0 | γ ≥ 0.102 |

| Varied Parameter | Value | System Reliability Index (β) | Optimal Copula for (Q-B) Pair | Parameter θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | / | 2.45 | Clayton | 2.15 |

| Arch Axis Coefficient (m) | 1.75 | 2.38 | Clayton | 2.08 |

| 1.95 | 2.51 | Clayton | 2.22 | |

| Rise-to-Span Ratio | 1/5.0 | 2.31 | Clayton | 2.31 |

| 1/6.5 | 2.58 | Frank | 3.05 | |

| Arch Concrete Grade | C50 | 2.29 | Gumbel | 1.78 |

| C60 | 2.62 | Clayton | 2.40 | |

| Site Class | II | 2.61 | Clayton | 2.33 |

| IV | 2.28 | Clayton | 1.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ye, H.; Wang, X. Seismic Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Arch Bridges Considering Component Correlation. Buildings 2025, 15, 4442. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244442

Liu J, Zhang J, Zhang H, Ye H, Wang X. Seismic Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Arch Bridges Considering Component Correlation. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4442. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244442

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jianjun, Jijin Zhang, Hanzhao Zhang, Hongping Ye, and Xuemin Wang. 2025. "Seismic Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Arch Bridges Considering Component Correlation" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4442. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244442

APA StyleLiu, J., Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Ye, H., & Wang, X. (2025). Seismic Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Arch Bridges Considering Component Correlation. Buildings, 15(24), 4442. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244442