Research on the Mix Proportion, Admixtures Compatibility and Sustainability of Fluidized Solidification Soil Coordinated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Wastes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

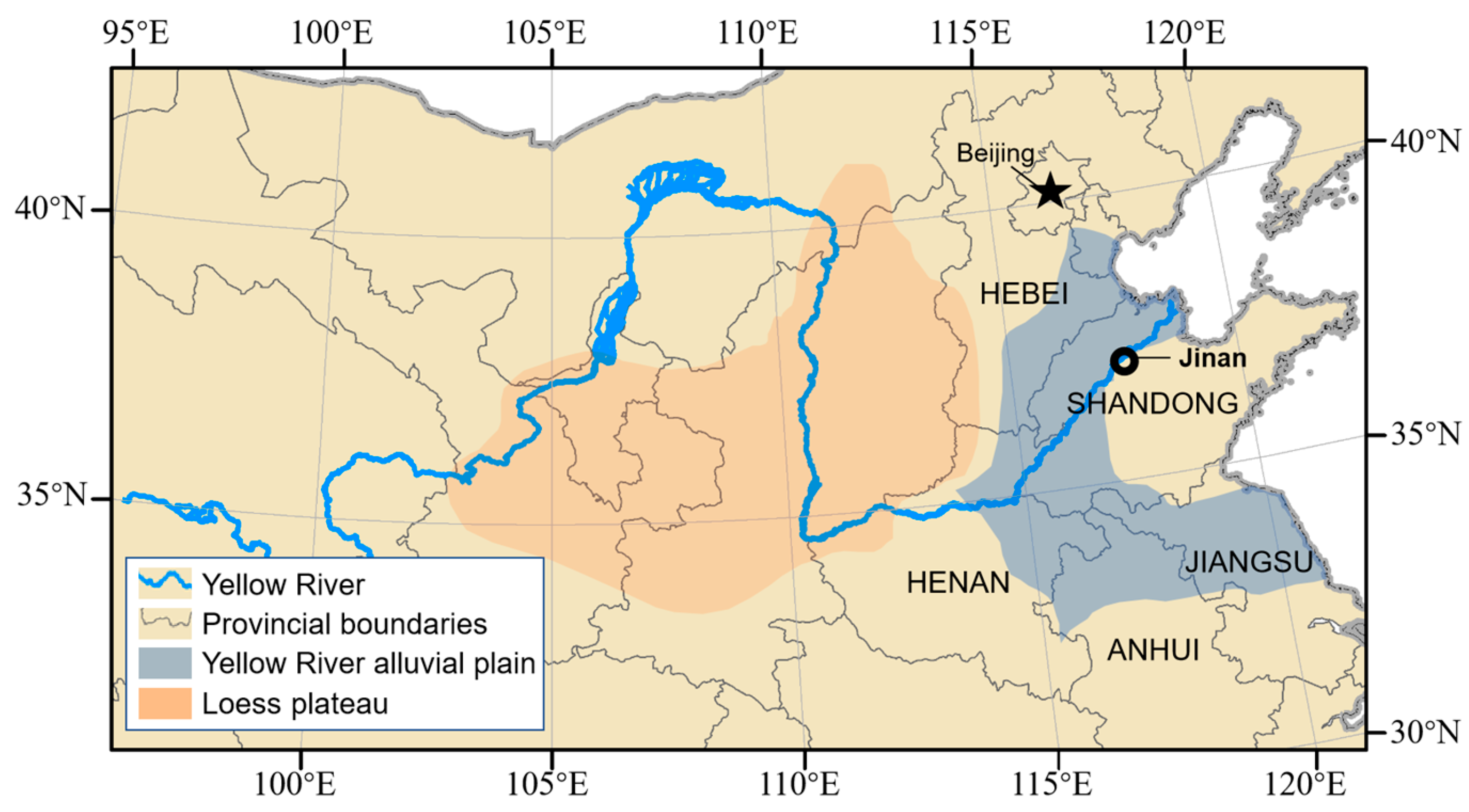

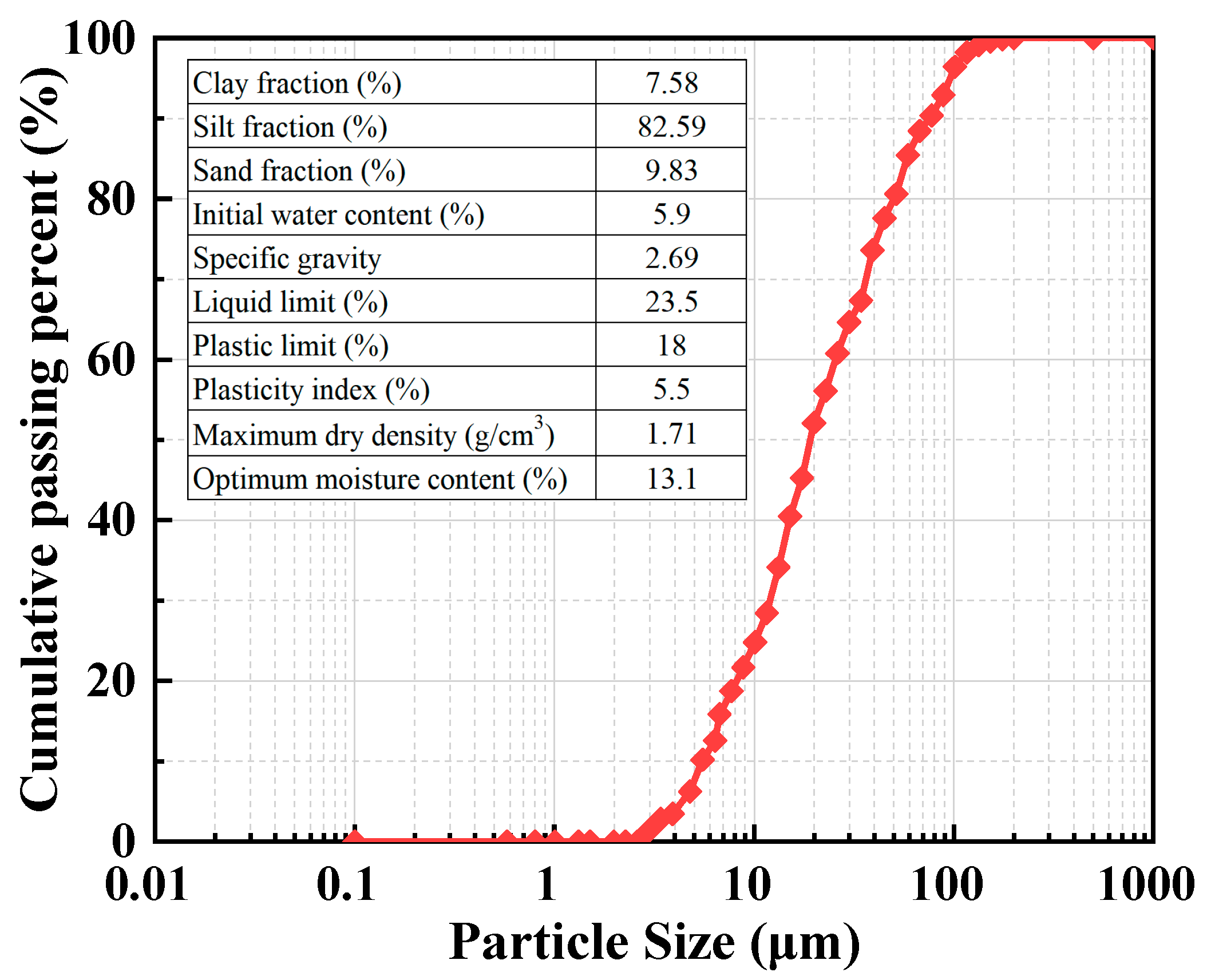

2.1.1. Soil

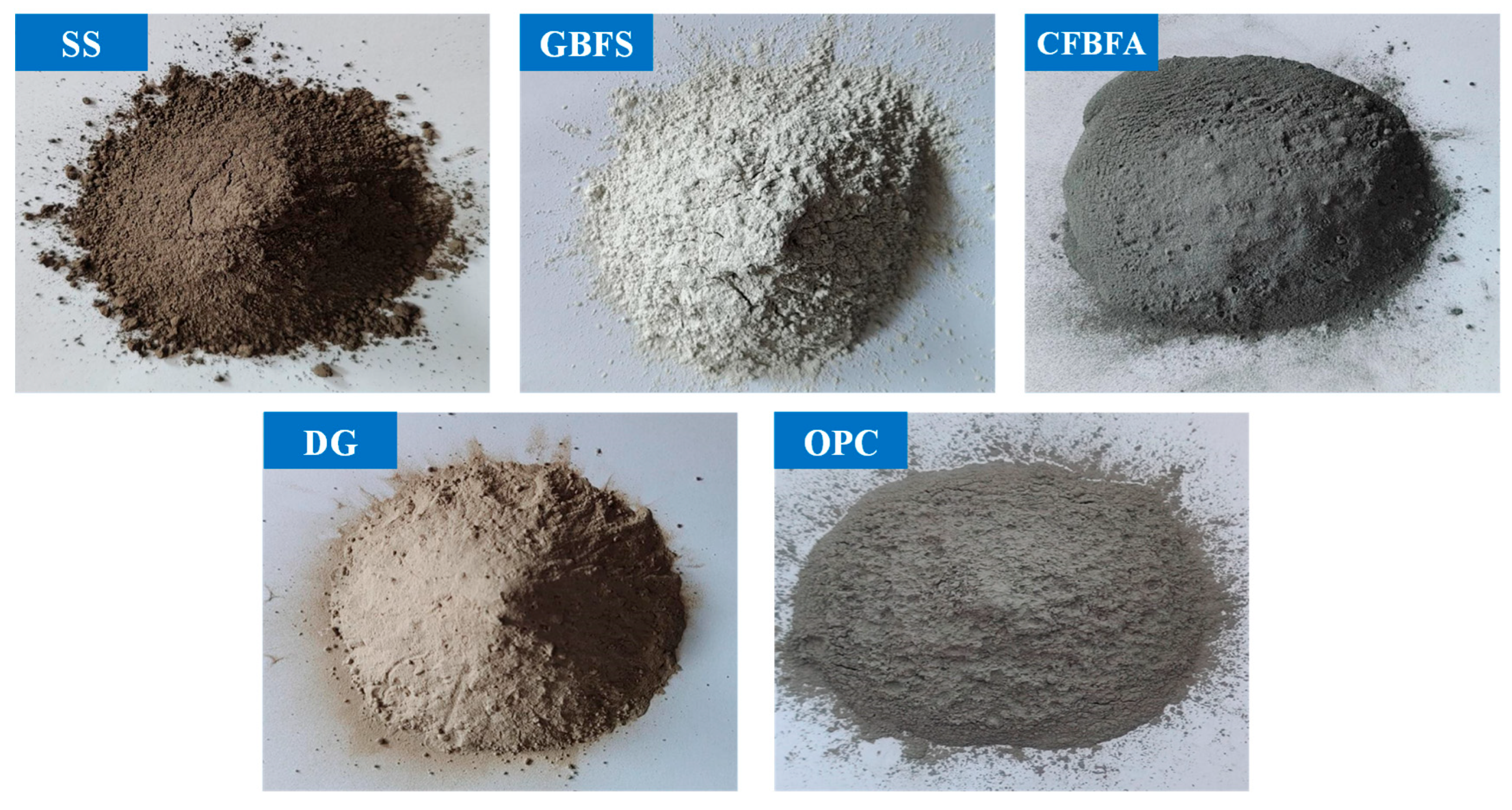

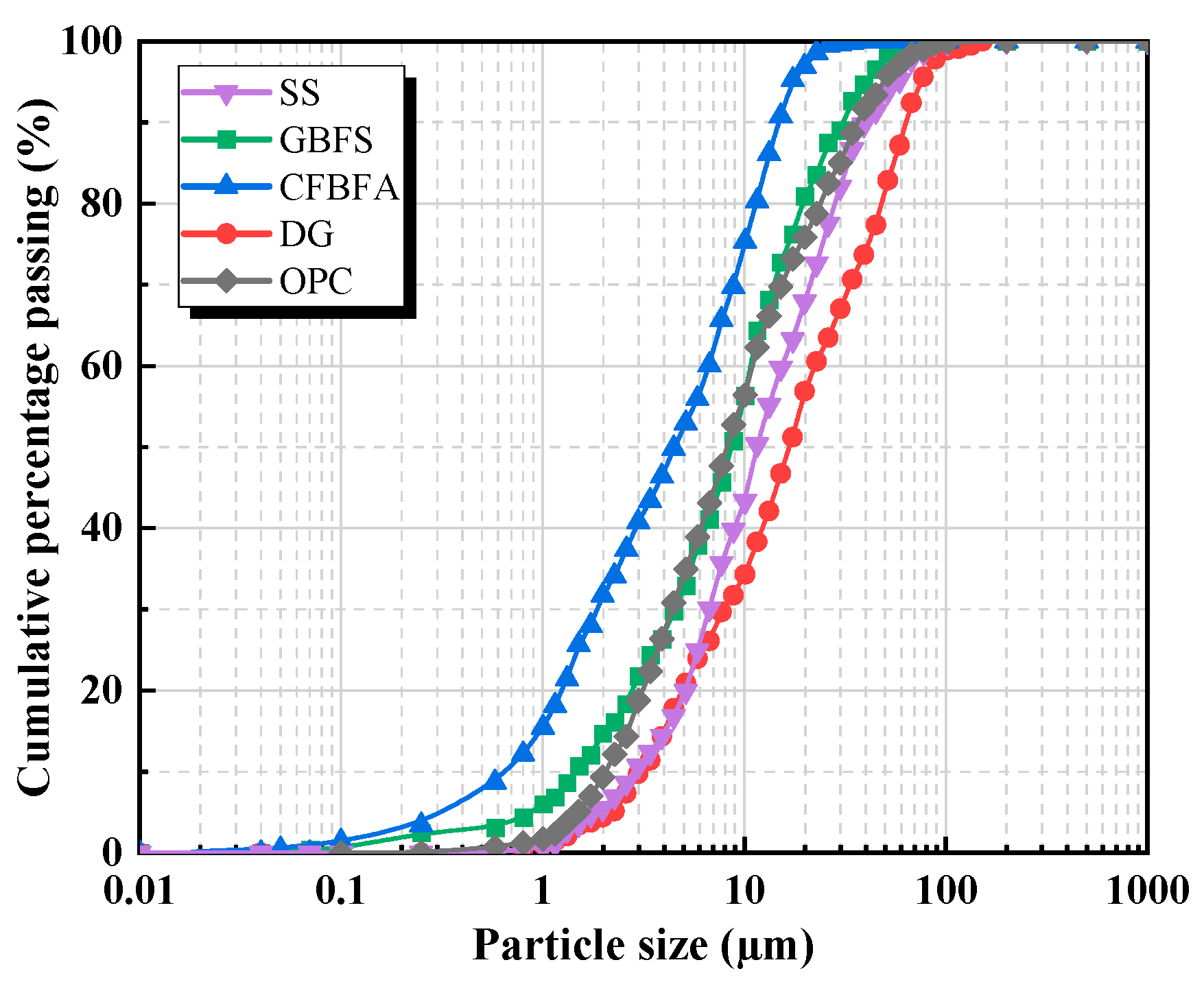

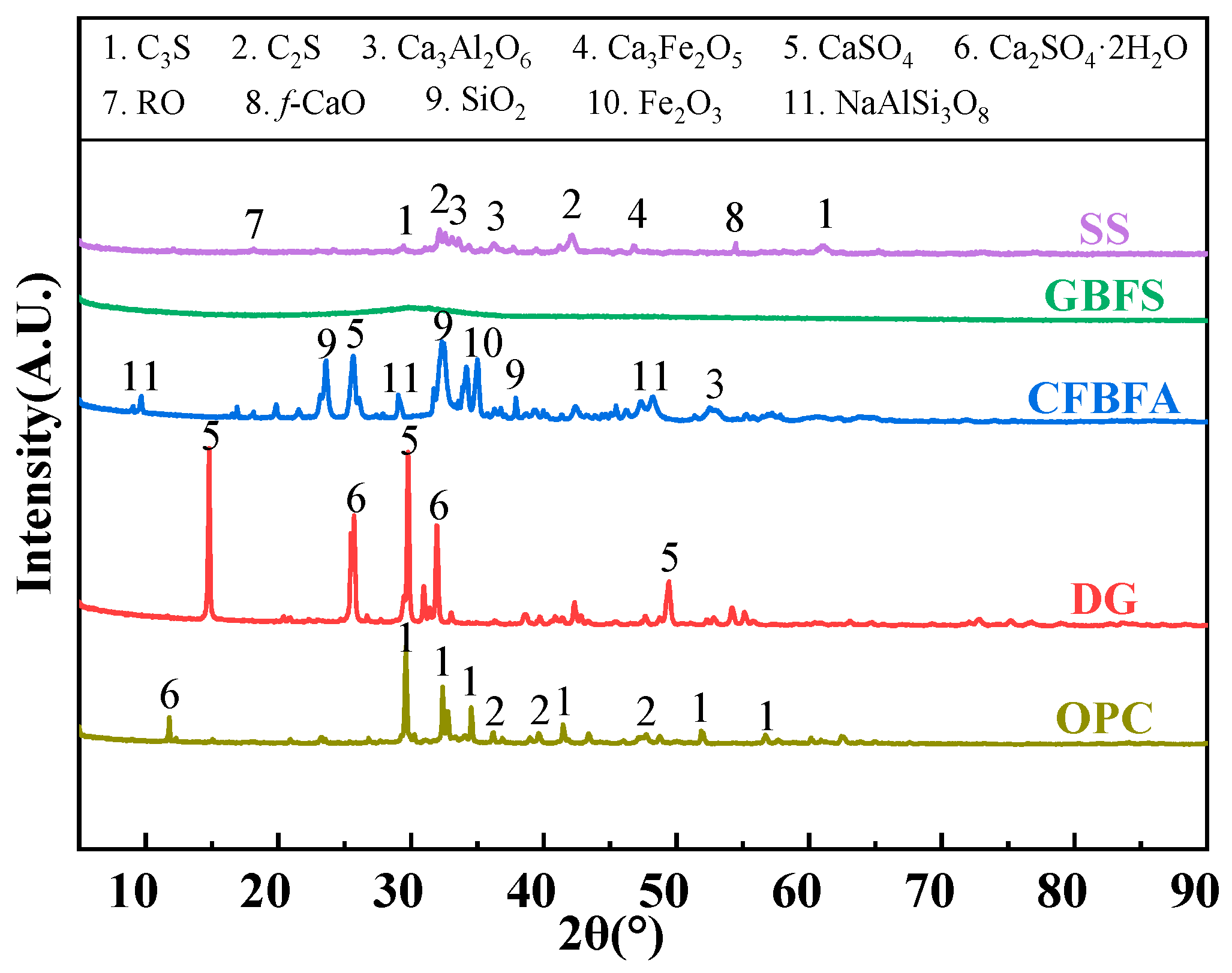

2.1.2. Raw Materials of MSWC

2.1.3. Admixtures

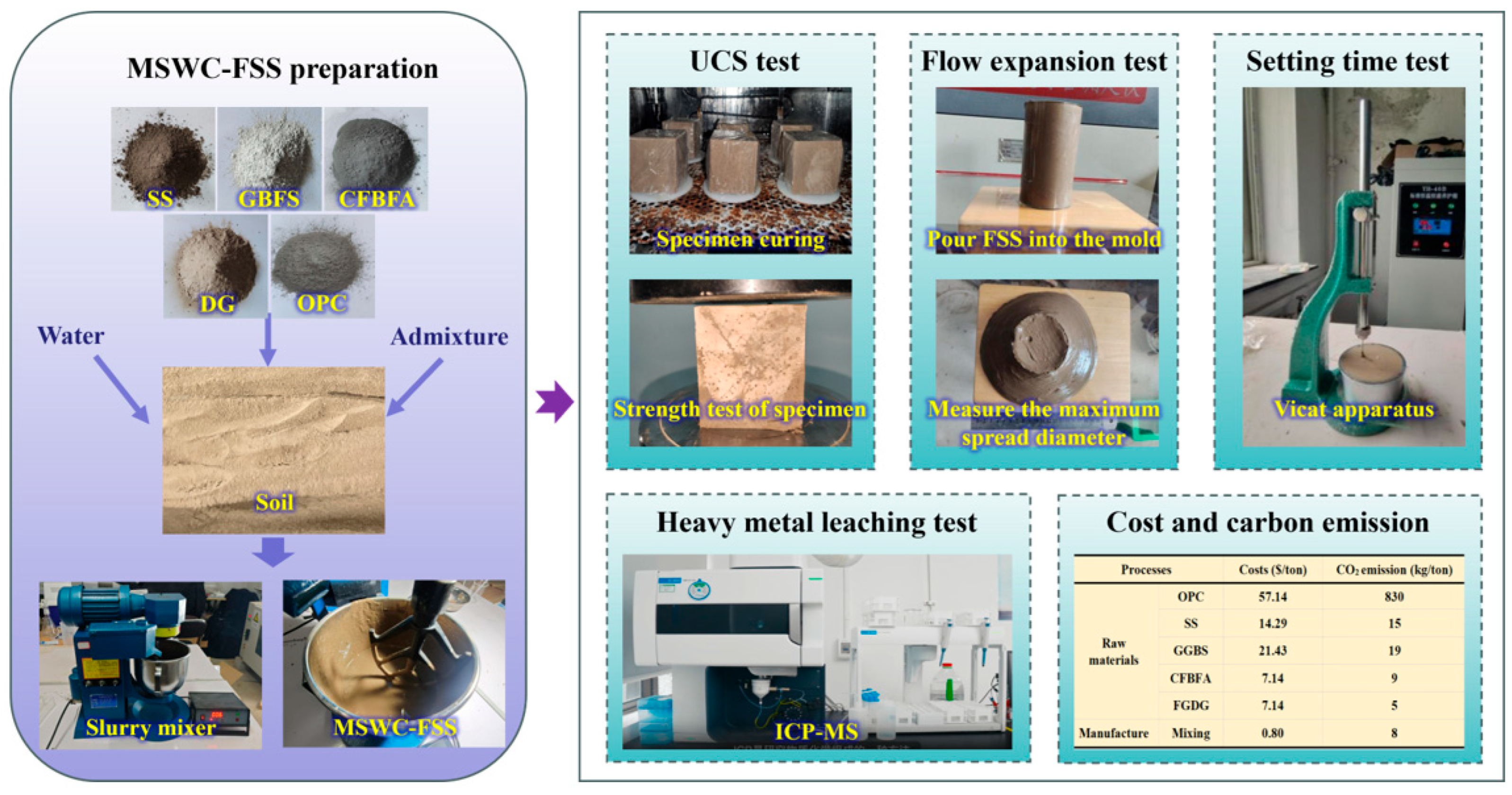

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. MSWC-FSS Preparation

2.2.2. UCS Test

2.2.3. Flow Expansion Test

2.2.4. Setting Time Test

2.2.5. Heavy Metal Leaching Test

3. Development of MSWC for FSS

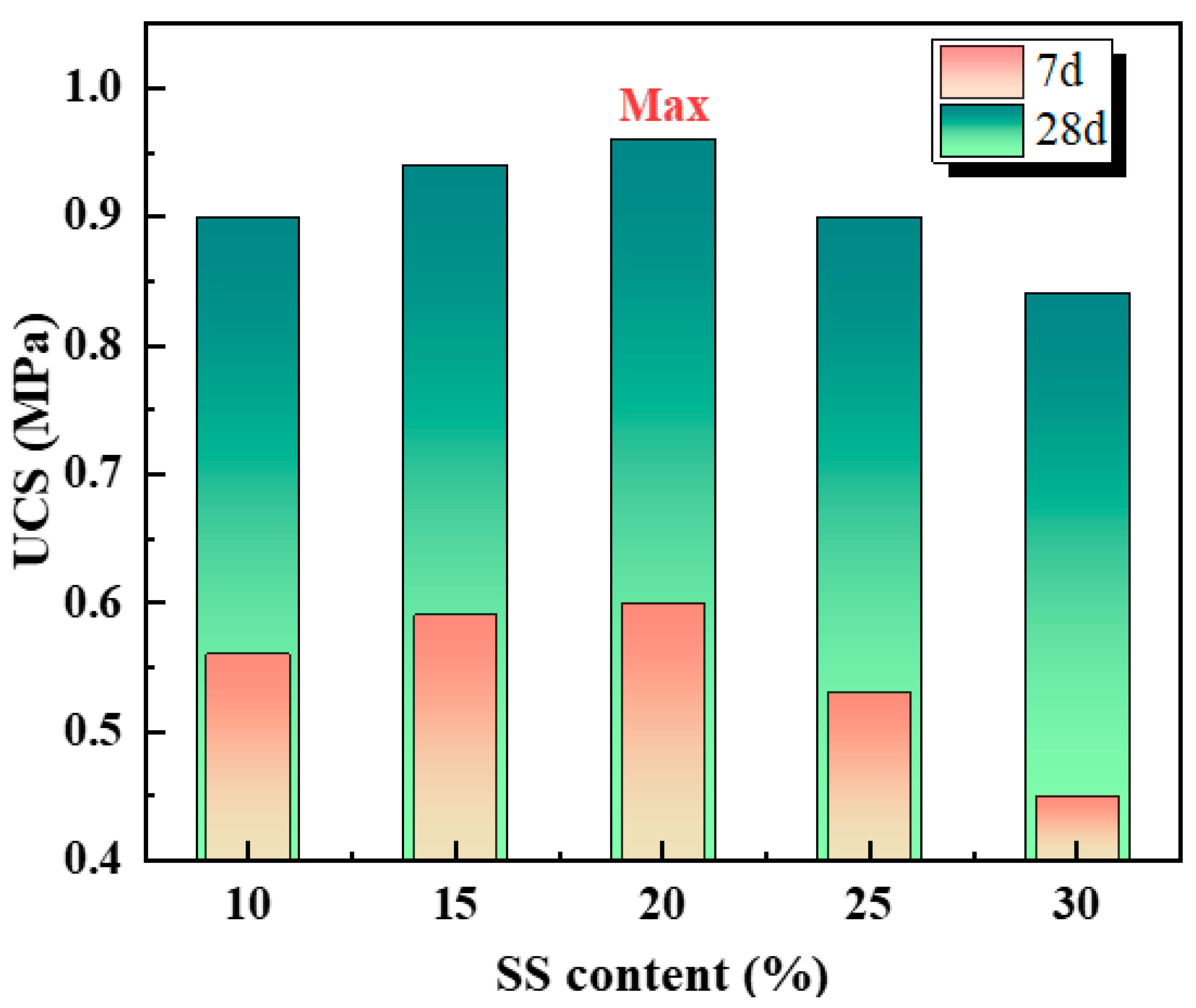

3.1. Effect of SS Content on UCS of MSWC-FSS

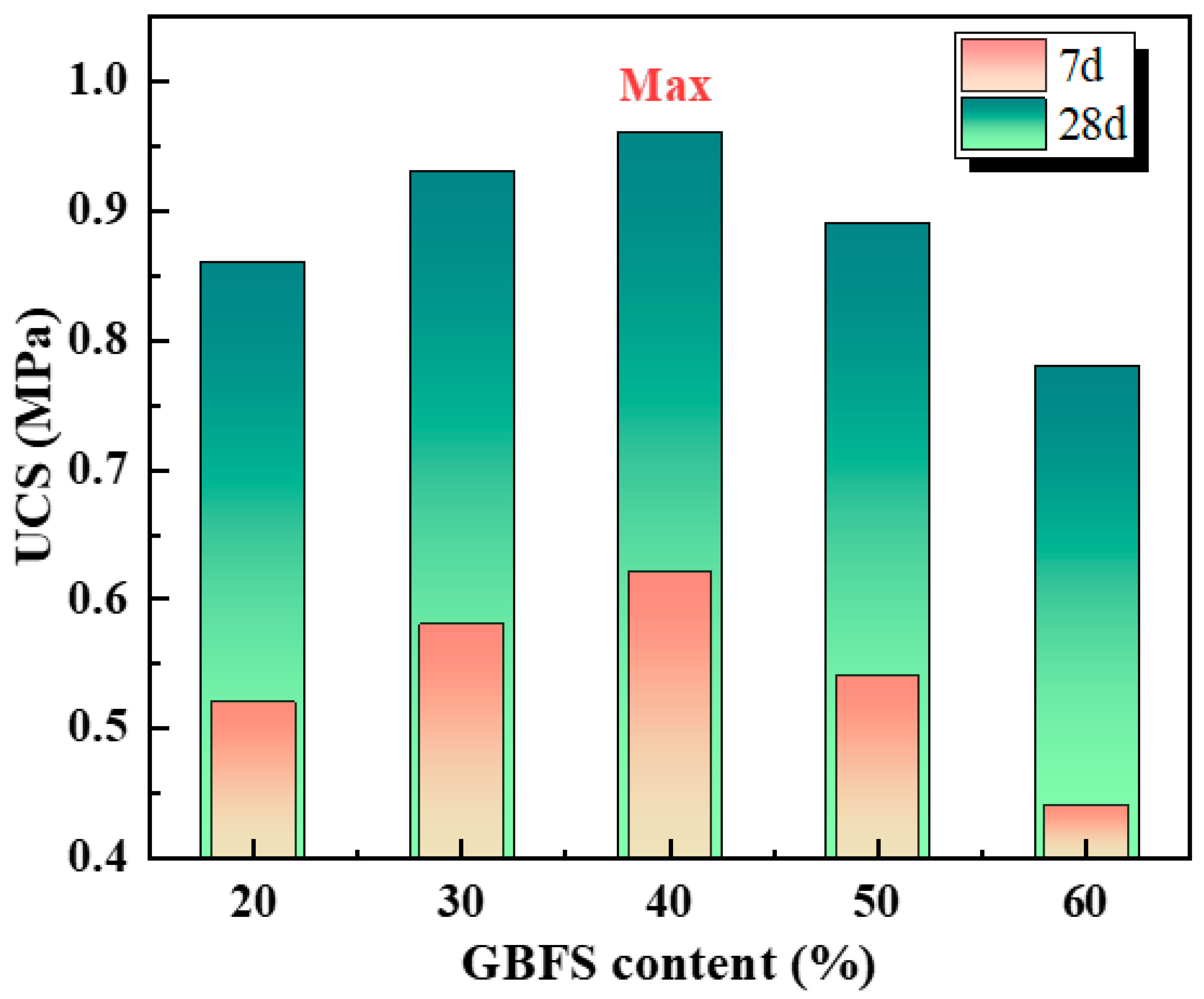

3.2. Effect of GBFS Content on UCS of MSWC-FSS

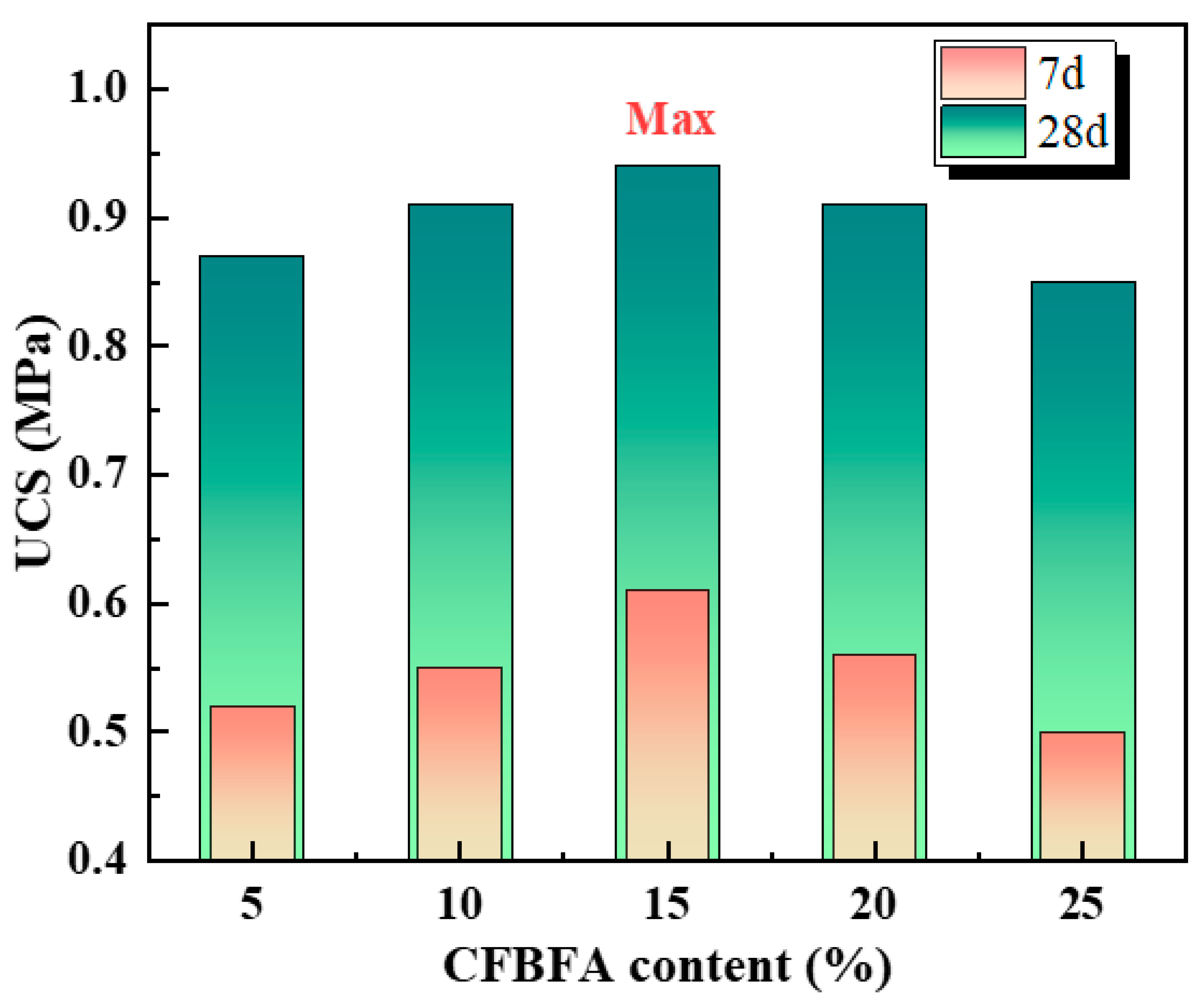

3.3. Effect of CFBFA Content on UCS of MSWC-FSS

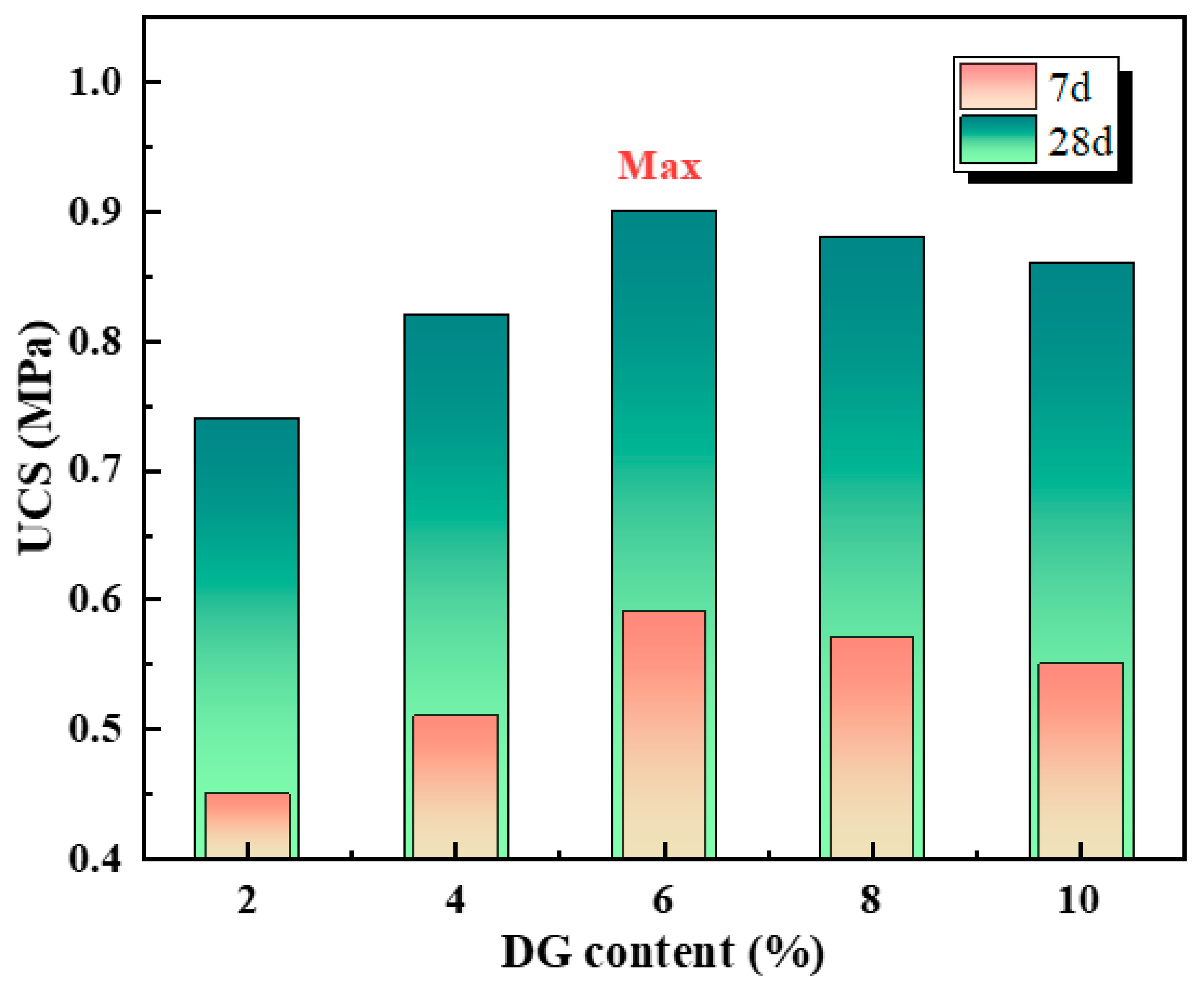

3.4. Effect of DG Content on UCS of MSWC-FSS

4. Study of Compatibility of Admixtures with MSWC-FSS

4.1. Water Reducers

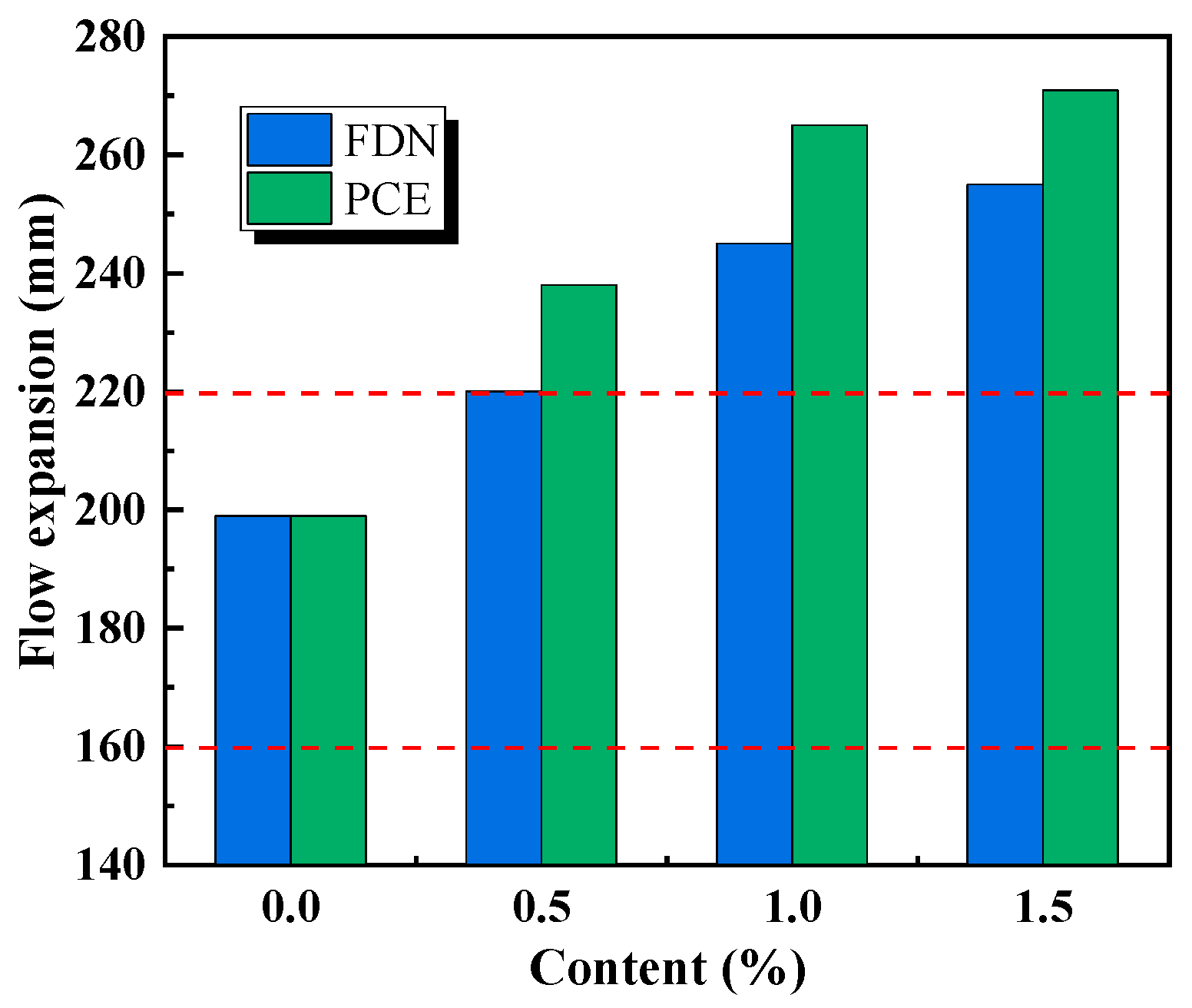

4.1.1. Effect of Water Reducers on the Flow Expansion of MSWC-FSS

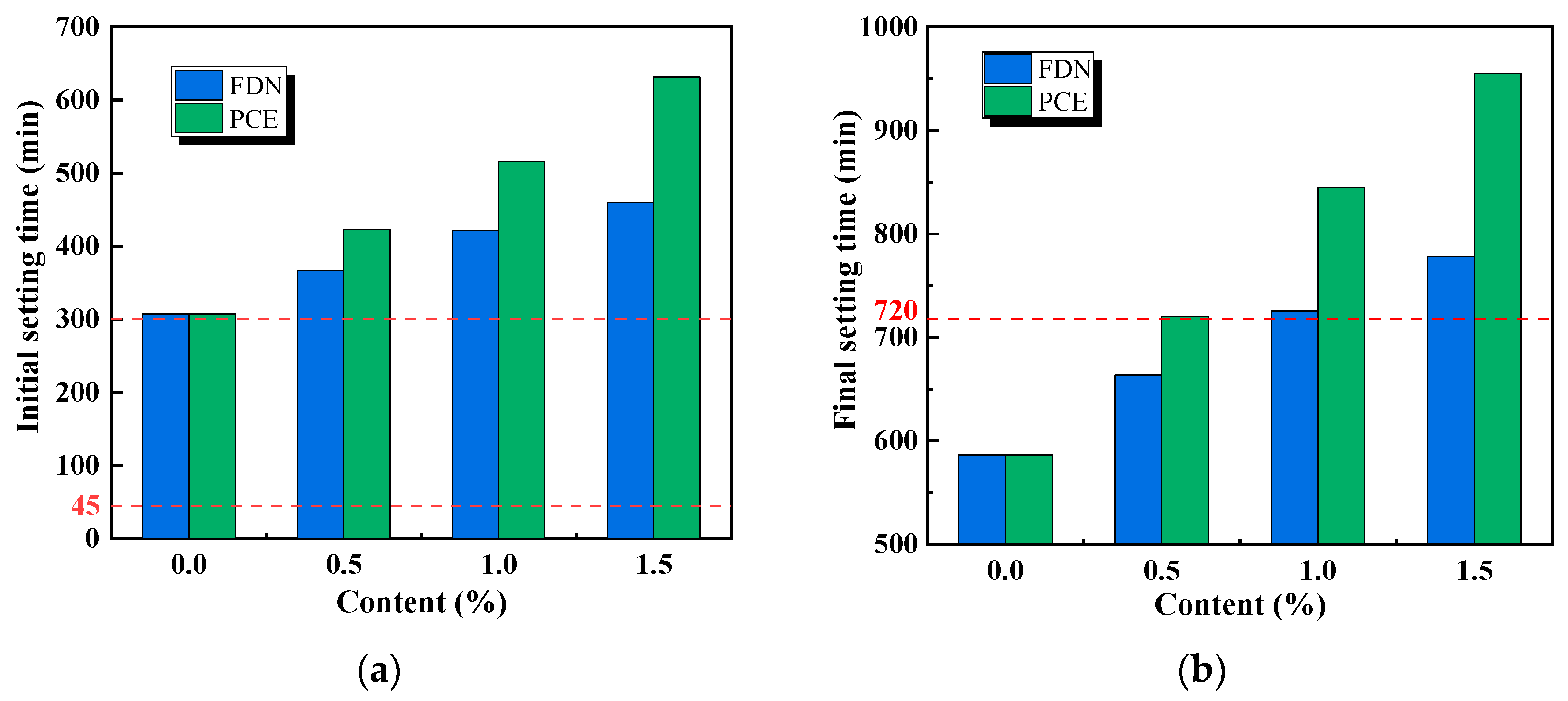

4.1.2. Effect of Water Reducers on the Setting Time of MSWC-FSS

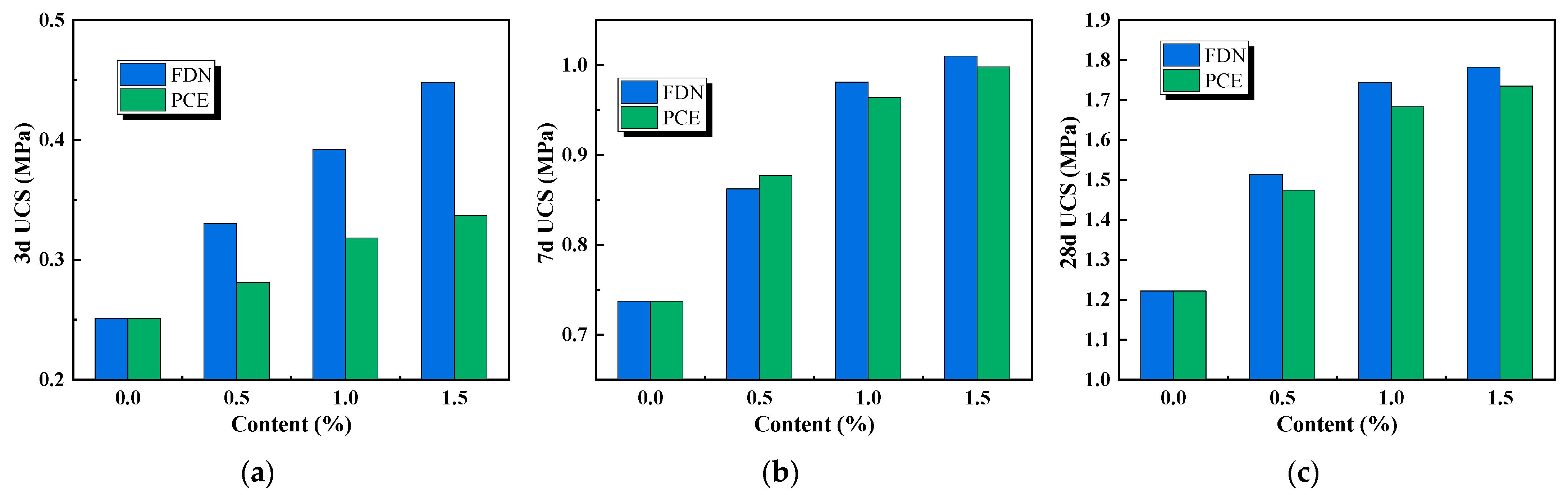

4.1.3. Effect of Water Reducers on the UCS of MSWC-FSS

4.2. Early-Strength Agents

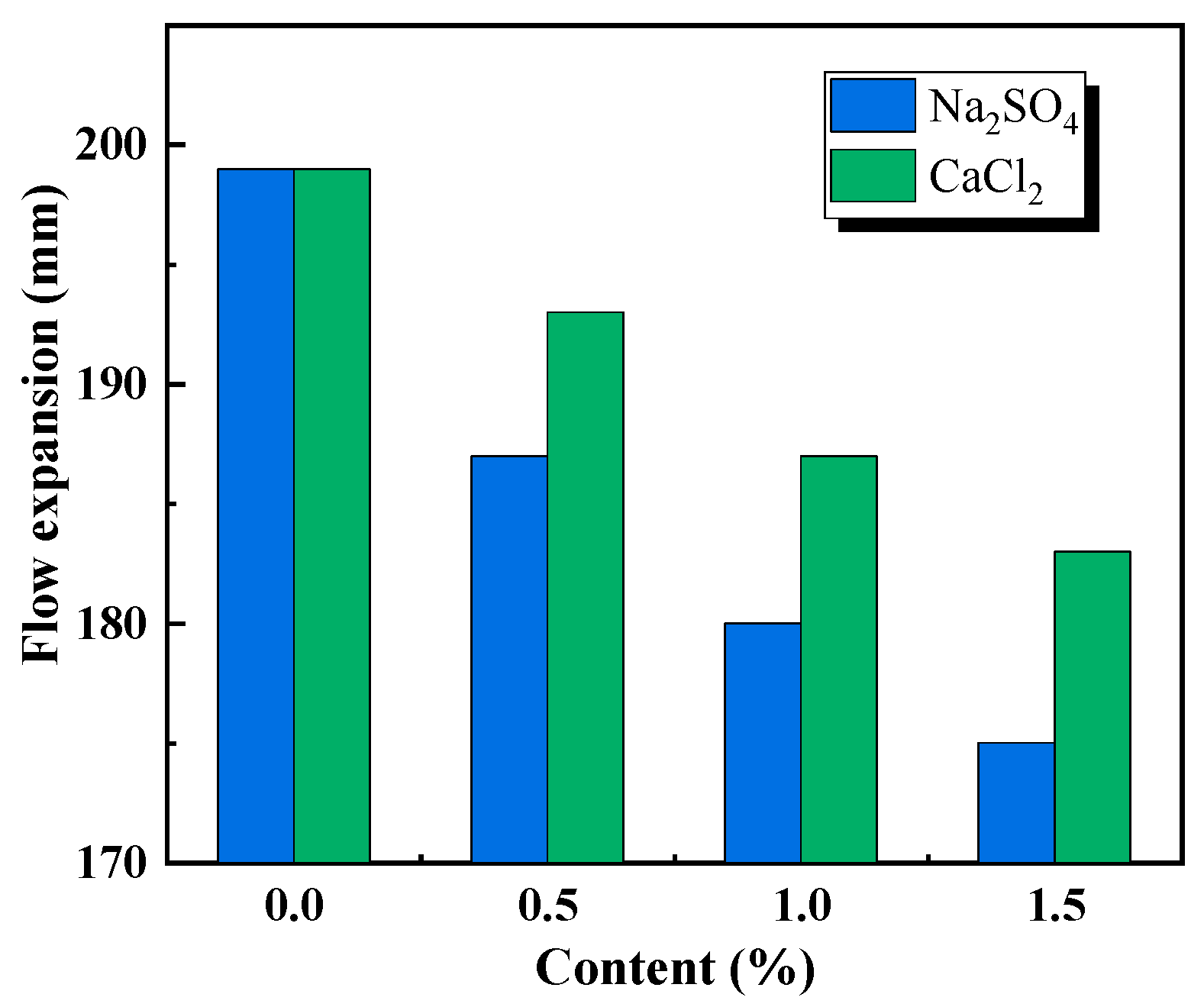

4.2.1. Effect of Early-Strength Agents on the Flow Expansion of MSWC-FSS

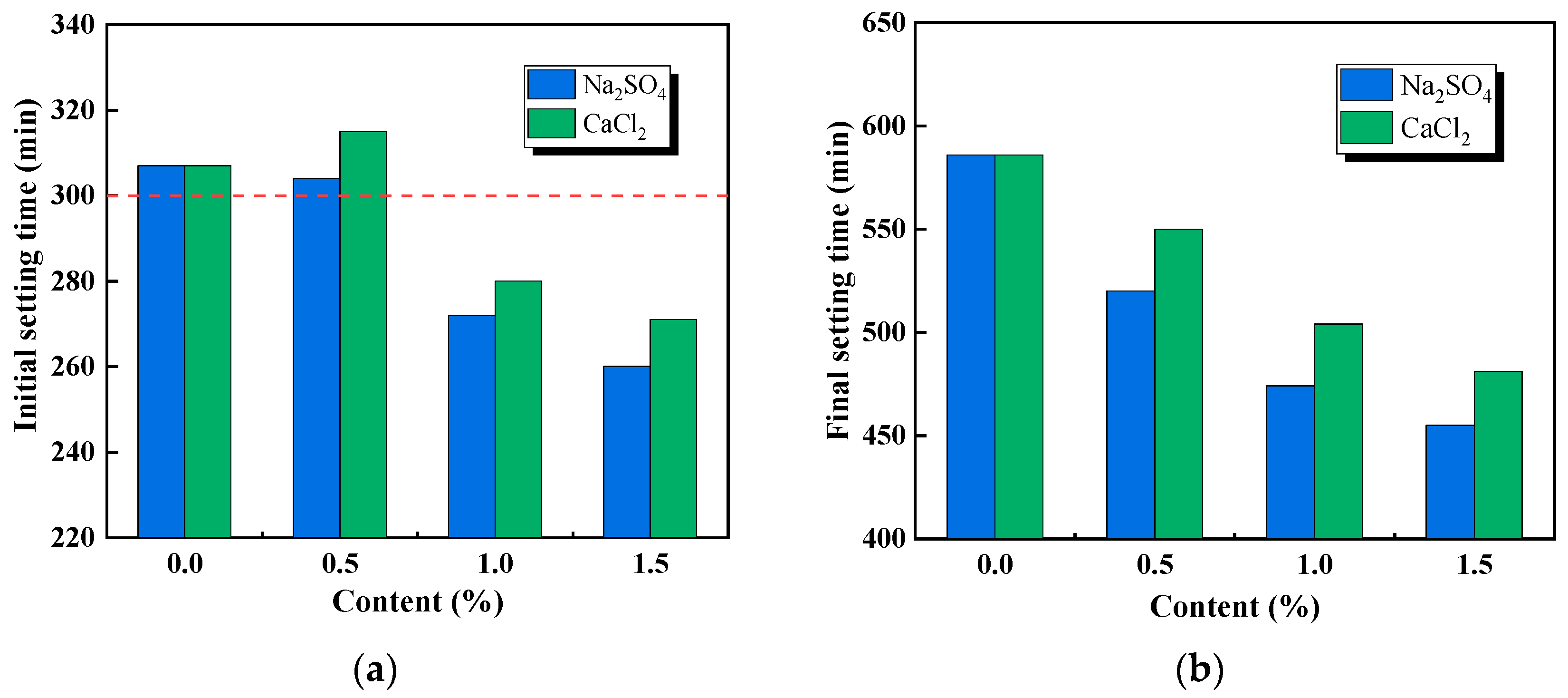

4.2.2. Effect of Early-Strength Agents on the Setting Time of MSWC-FSS

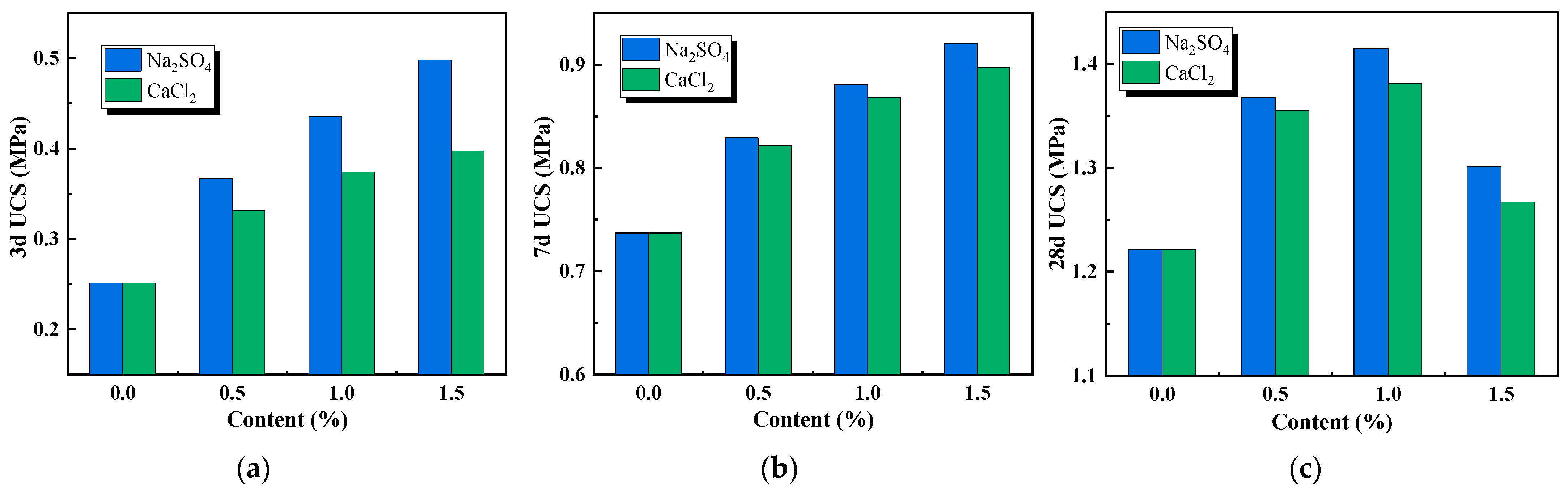

4.2.3. Effect of Early-Strength Agents on the UCS of MSWC-FSS

5. Sustainability Assessment of MSWC-FSS

5.1. Heavy Metal Leaching Behavior

5.2. Cost and Carbon Emissions Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, X.; Meng, H.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Q.; Wang, L. Development, Performance, and Mechanism of Fluidized Solidified Soil Treated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Waste Cementitious Materials. Buildings 2025, 15, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Pang, S.; Xie, F.; Fan, H.; Sun, J. Optimization of ratios and strength formation mechanism of fluidized solidified soil from multi-source solid wastes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Han, L.; Shi, P.; Rong, Y.; Ba, M.; Li, S.; Miao, H.; Zhao, Y. Preparation and characterization of premixed fluidized solidified soil with municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Hou, L. The design methodology for proportioning fluidized solidified soil. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhan, J.; Wang, X. Influence of composition of curing agent and sand ratio of engineering excavated soil on mechanical properties of fluidized solidified soil. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2023, 41, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Chen, G.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Z. Sustainable solutions: Transforming waste shield tunnelling soil into geopolymer-based underwater backfills. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, X. Test study on mechanical properties of compound municipal solid waste incinerator bottom ash premixed fluidized solidified soil. Iscience 2023, 26, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Lin, K.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Li, N.; Wang, W. Fluidized solidified soil using construction slurry improved by fly ash and slag: Preparation, mechanical property, and microstructure. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 115301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; He, L.; Shen, S. Analysis of strength characteristics and microstructure of alkali-activated slag cement fluidized solidified soil. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 085502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Alkali-Activated Dredged-Sediment-Based Fluidized Solidified Soil: Early-Age Engineering Performance and Microstructural Mechanisms. Materials 2025, 18, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huo, M.; Hou, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L. Current Research and Prospect of Low Strength Flowable Filling Materials. Mater. Rep. 2024, 38, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Scrivener, K.; Kirkpatrick, R. Innovation in use and research on cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Cui, X.; Du, Y.; Jin, Q.; Hao, J.; Cao, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Development and verification of subgrade service performance test system considering the principal stress rotation. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 50, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Xie, J.; Vuye, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Synthesis of geopolymer using alkaline activation of building-related construction and demolition wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Z.; Blom, J.; Vuye, C.; Gu, F. Feasibility of using building-related construction and demolition waste-derived geopolymer for subgrade soil stabilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 142001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Chen, B. Study on the basic properties and mechanism of waste sludge solidified by magnesium phosphate cement containing different active magnesium oxide. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xue, Y.; Wu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, M. Performance investigation and environmental application of basic oxygen furnace slag—Rice husk ash based composite cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 123, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Ma, W. Study on the mechanical properties and solidification mechanism of ground granulated blast furnace slag-carbide slag-desulfurization gypsum solidified shield musk. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 475, 141166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gu, F. Hydration mechanisms of geopolymer grouting materials derived from circulating fluidized bed fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag. Powder Technol. 2025, 466, 121402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Effect of calcination process on ferrite phase and silicate phase of ferrite-belite-rich Portland cement clinker from industrial solid waste. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 2024, 13, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, B.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Cui, L.; Liang, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ou, H.; Liang, H. Energy effective utilization of circulating fluidized bed fly ash to prepare silicon-aluminum composite aerogel and gypsum. Waste Manag. 2023, 172, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Zhou, W.; Lyu, X.; Liu, X.; Su, H.; Li, C.; Wang, H. Comprehensive utilization of steel slag: A review. Powder Technol. 2023, 422, 118449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, J.; Xiang, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Rong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chang, J.; Zhang, H.; He, J. Optimization of Curing-agent Mix Ratio and Mechanism of Strength of Fluidized Multisource Solid-waste Solidified Loesses China J. Highw. Transp. 2025, 38, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Dong, W.; Sun, Q.; Yao, G.; Lv, R. Research on the preparation and properties of GBFS-based mud solidification materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 423, 135900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jarmouzi, R.; Sun, Z.; Yang, H.; Ji, Y. The Synergistic Effect of Water Reducer and Water-Repellent Admixture on the Properties of Cement-Based Material. Buildings 2024, 14, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, C.; Shu, X.; Ran, Q.; Yang, Y. Recent advance of chemical admixtures in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 124, 105834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Huang, P. Early Strengthening Agent in Cementitious Composites and Its Function Mechanism: A Review. Mater. Rep. 2023, 37, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Yu, F.; Du, T. A review of the application of steel slag in concrete. Structures 2024, 63, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencel, O.; Karadag, O.; Oren, O.H.; Bilir, T. Steel slag and its applications in cement and concrete technology: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 283, 122783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.O.; Nguyen, T.B.T.; Honeyands, T.; Monaghan, B.; O’Dea, D.; Rinklebe, J.; Vinu, A.; Hoang, S.A.; Singh, G.; Kirkham, M.B.; et al. Production, characterisation, utilisation, and beneficial soil application of steel slag: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, E.O.; Pederson, F.; Kim, H.-J. Application of steel slags, ferronickel slags, and copper mining waste as construction materials: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bao, Y.; Wang, M. Steel slag in China: Treatment, recycling, and management. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, S.; Wang, Q. Inhibition mechanisms of steel slag on the early-age hydration of cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ling, T.-C.; Shi, C.; Pan, S.-Y. Characteristics of steel slags and their use in cement and concrete-A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Cui, X.; Ma, X.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, H. Experimental investigation on dynamic characteristics of hydrophobic modified silt after freezing-thawing under cyclic loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Kang, X.; Su, C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. Effects of water chemistry on microfabric and micromechanical properties evolution of coastal sediment: A centrifugal model study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhu, L.; Zou, X.; Kang, X. Investigation of the interface stick-slip friction behavior of clay nanoplatelets by molecular dynamics simulations. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 679, 132601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, R. Simulation and property prediction of MgO-FeO-MnO solid solution in steel slag. Mater. Lett. 2020, 273, 127930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG 3430; Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- ASTM D6103; Standard Test Method for Flow Consistency of Controlled Low Strength Material (CLSM). American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- DBJ51/T 188; Technical Standard for Engineering Application by Using Premixed Fluidized Stabilized Soil. Department of Housing and Urban Rural Development of Sichuan Province: Chengdu, China, 2022.

- GB/T 1346; Test Methods for Water Requirement Of Standard Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. State Administration for Market Regulation, National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2024.

- GB 5085.3; Identification Standards for Hazardous Wastes-Identification For Extraction Toxicity. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- HJ/T 300; Solid Waste-Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity-Acetic Acid Buffer Solution Method. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Lu, C.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hawileh, R. Synergistic effect of waste steel slag powder and fly ash in sustainable high strength engineered cementitious composites: From microstructure to macro-performance. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Cui, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, B. Enhancing the hydration activity of steel slag-Portland cement composite by BES sodium activator. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 48, 102213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Gao, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, M. Municipal solid waste incineration fly ash as activator for ground granulated blast-furnace slag: Hydration behavior and stabilization/solidification effectiveness. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, P.; Chen, X.; Ge, X.; Wang, Y. Study on hydration characteristics of circulating fluidized bed combustion fly ash (CFBCA). Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, T.; Ni, W.; Li, K.; Gao, W.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. The mechanism of hydrating and solidifying green mine fill materials using circulating fluidized bed fly ash-slag-based agent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, G.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H. Study on long-term solidification of all-solid waste cementitious materials based on circulating fluidized bed fly ash, red mud, carbide slag, and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 427, 136284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerato, F.; Rocha, J. Effect of heat-treated flue gas desulfurization gypsum on the setting time of stabilized mortars: An experimental study. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, L.; Wang, J.; Yao, T.; Sun, G.; Zong, C.; Zhang, H. Effect of fluorgypsum and flue gas desulfurization gypsum on properties of aluminate cement based grouting materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Peng, G.; Wang, H. Experimental study on influence of plasticizer on fluidity of convection solidified silt Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, G.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H. Property enhancement and mechanism of cement-based composites from the perspective of nano-silica dispersion improvement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Song, W.; Shu, X.; Huang, B. Use of water reducer to enhance the mechanical and durability properties of cement-treated soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Niu, M.; Song, Z. The mechanism of alkali-free liquid accelerator on the hydration of cement pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, Z. Synergistic Effect of Early-Strength Agents on the Mechanical Strength of Alkali-Free Liquid Accelerator Mortar. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wang, Z.; Yin, L.e.; Li, H. Research on Synergistic Enhancement of UHPC Cold Region Repair Performance by Steel Fibers and Early-Strength Agent. Buildings 2025, 15, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, G.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Gao, J. Effect of a novel negative temperature early-strength agent in improving concrete performance under varying curing temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, H. Effects of wet grinding combined with chemical activation on the activity of iron tailings powder. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ni, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Li, Z. Investigation into the semi-dynamic leaching characteristics of arsenic and antimony from solidified/stabilized tailings using metallurgical slag-based binders. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 381, 120992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ju, C.; Zhou, M.; Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Hou, H. Sustainable and efficient stabilization/solidification of Pb, Cr, and Cd in lead-zinc tailings by using highly reactive pozzolanic solid waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 306, 114473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, I.K.; Azzam, A.; Al Jebaei, H.; Kim, Y.-R.; Aryal, A.; Baltazar, J.-C. Effects of alkali-activated slag binder and shape-stabilized phase change material on thermal and mechanical characteristics and environmental impact of cementitious composite for building envelopes. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Long, G.; Ma, C.; Xie, Y.; He, J. Design and preparation of ultra-high performance concrete with low environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.M.; Trinh, H.T.M.K.; Nguyen, D.; Tao, Q.; Mali, S.; Pham, T.M. Development of sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete containing ground granulated blast furnace slag and glass powder: Mix design investigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 397, 132358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Raw Materials of Cementitious Material | Soil | Admixtures | Mass Ratio of Cementitious Material to Dry Soil (%) | Water-Solid Ratio | 28 d UCS of FSS (MPa) | Size of UCS Specimen (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Cement, silica fume and CaO | Dredged sediment | / | 20 | 0.55 | 0.8~1.0 | 70.7 × 70.7 × 70.7 |

| [2] | GBFS, fly ash, carbide slag and Ca(OH)2 | Low-plasticity clay | / | 8, 12, 16, 20 | 0.50, 0.52, 0.54, 0.56, 0.58 | 0.3~2.4 | φ39.1 × 80 |

| [3,7] | GBFS, MSWI-BAP, cement, gypsum and sodium silicate | Clay mixed with MSWI-BA aggregate | 1.5% water reducer | 30 | About 0.6 | 3~7 | φ40 × 80 |

| [6] | Sodium silicate, GBFS and cement | Waste shield tunnelling soil | Anti-washout admixtures (polyacrylamide, hydroxyethyl cellulose), 0.075% PCE | 23 | 0.967 | 1.5~1.6 (formed in air), 1.35 (formed in water) | φ39.1 × 80 |

| [9] | alkaline-activator (CaO and Na2CO3), GBFS | The soil from the foundation trench | / | 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 | 0.67 | 4.4~7.3 | 70.7 × 70.7 × 70.7 |

| [5] | CaO, cement and fly ash | Engineering excavated soil mixed with 2%, 15% and 65% sand | / | 15 | 0.8 | 0.4~3.3 | 100 × 100 × 100 |

| [8] | Cement, fly ash, GBFS and DG | High moisture content slurry from the construction site | 2% water reducer | 16.3 | 0.542 | 0.67 | 70.7 × 70.7 × 70.7 |

| [23] | Cement, GBFS, CFBFA and DG | Loess | / | 15 | 0.51 | 0.39~2.14 | 70.7 × 70.7 × 70.7 |

| [24] | GBFS, fly ash, carbide slag, cement and DG | The soil from a construction site | 0.5% water reducers (FDN and PCE), 1.5% early-strength agents (NaCl, CaCl2 and Na2SO4) | 25 | 0.32 | 3~6 | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| Setting Time (min) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Specific Surface Area (m2/kg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | 3 d | 7 d | 28 d | |

| 115 | 184 | 33.8 | 43.5 | 51.6 | 381 |

| Materials | Chemical Composition (wt.%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | Fe2O3 | SO3 | TiO2 | K2O | |

| SS | 30.62 | 16.28 | 8.72 | 6.29 | 28.57 | — | — | — |

| GBFS | 44.71 | 29.29 | 14.85 | 7.33 | 0.39 | 1.28 | 0.68 | 0.41 |

| CFBFA | 3.44 | 49.93 | 36.17 | 0.79 | 5.8 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.17 |

| DG | 45.35 | 1.56 | 0.8 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 50.63 | 0.02 | 0.41 |

| OPC | 51.42 | 24.99 | 8.26 | 3.71 | 4.03 | 2.51 | — | — |

| Number | Raw Materials Content in MSWC (wt.%) | MSWC Content (wt.%) | Water-Solid Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | GBFS | CFBFA | DG | OPC | |||

| 1 | 10 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 40 | 15 | 0.45 |

| 2 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 35 | ||

| 3 | 20 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 30 | ||

| 4 | 25 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 25 | ||

| 5 | 30 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 20 | ||

| 6 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 50 | ||

| 7 | 15 | 30 | 10 | 5 | 40 | ||

| 8 | 15 | 40 | 10 | 5 | 30 | ||

| 9 | 15 | 50 | 10 | 5 | 20 | ||

| 10 | 15 | 60 | 10 | 5 | 10 | ||

| 11 | 15 | 35 | 5 | 5 | 40 | ||

| 12 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 35 | ||

| 13 | 15 | 35 | 15 | 5 | 30 | ||

| 14 | 15 | 35 | 20 | 5 | 25 | ||

| 15 | 15 | 35 | 25 | 5 | 20 | ||

| 16 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 2 | 38 | ||

| 17 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 4 | 36 | ||

| 18 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 6 | 34 | ||

| 19 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 8 | 32 | ||

| 20 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 10 | 30 | ||

| Admixture Content (%) | MSWC Content (wt.%) | Water-Solid Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Reducers (FDN and PCE) | Early-Strength Agents (Na2SO4 and CaCl2) | ||

| 0.5, 1, 1.5 | 0 | 15 | 0.45 |

| 0 | 0.5, 1, 1.5 | ||

| Sample | Concentration (ug/L) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | Cr | Cd | Cu | As | Pb | Ni | Mn | Hg | |

| MSWC | 223 | Not detected | 84.7 | Not detected | 5.3 | 4.2 | Not detected | 22.1 | 0.074 |

| MSWC-FSS | 87.4 | Not detected | 3.6 | Not detected | 2.2 | 1.1 | Not detected | 4.3 | 0.04 |

| Limits | 1 × 105 | 5 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 105 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 1 × 102 |

| Processes | Proportion in MSWC | Costs ($/ton) | CO2 Emission (kg/ton) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw material procurement | OPC | 20 | 57.14 | 830 |

| SS | 20 | 14.29 | 15 | |

| GBFS | 40 | 21.43 | 19 | |

| CFBFA | 15 | 7.14 | 9 | |

| DG | 5 | 7.14 | 5 | |

| Manufacture | Mixing | 100 | 0.80 | 8 |

| MSWC | 100 | 25.09 | 186.20 | |

| Cementitious Material Type | FSS Density (ton/m3) | Water-Solid Ratio | Cementitious Materials Content (%) | Cementitious Materials Mass (ton/m3) | Unit-Cost ($/m3) | Unit-CO2 Emission (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSWC | 1.7 | 0.45 | 15 | 0.176 | 4.41 | 32.75 |

| OPC | 10.05 | 145.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Shu, R.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Han, B.; Cui, X.; Meng, H.; Zhang, X. Research on the Mix Proportion, Admixtures Compatibility and Sustainability of Fluidized Solidification Soil Coordinated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Wastes. Buildings 2025, 15, 4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244440

Sun H, Shu R, Liu J, Yu X, Han B, Cui X, Meng H, Zhang X. Research on the Mix Proportion, Admixtures Compatibility and Sustainability of Fluidized Solidification Soil Coordinated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Wastes. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244440

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Hao, Rong Shu, Jilin Liu, Xiaoqing Yu, Bolin Han, Xinzhuang Cui, Huaming Meng, and Xiaoning Zhang. 2025. "Research on the Mix Proportion, Admixtures Compatibility and Sustainability of Fluidized Solidification Soil Coordinated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Wastes" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244440

APA StyleSun, H., Shu, R., Liu, J., Yu, X., Han, B., Cui, X., Meng, H., & Zhang, X. (2025). Research on the Mix Proportion, Admixtures Compatibility and Sustainability of Fluidized Solidification Soil Coordinated with Multi-Source Industrial Solid Wastes. Buildings, 15(24), 4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244440