3.1. Framework Overview

This study proposes a modular multimodal intelligent agent framework for construction site safety monitoring and hazard reasoning. The framework integrates three core components—perception, knowledge, and reasoning—establishing a closed-loop workflow of “scene perception, regulation matching and hazard reasoning.” It comprises three submodules, with the overall architecture illustrated in

Figure 1.

The scene understanding module focuses on collecting basic data. By integrating YOLOv10 with the CLIP model fine-tuned by LoRA, it accurately captures the activity types of construction personnel and the wearing status of PPE. This module outputs structured scene descriptions to ensure reliable perception in complex construction site environments. The knowledge retrieval module builds a construction safety knowledge graph to represent entities such as construction objects and activity types. By integrating RAG, it retrieves relevant information from the knowledge graph and injects it into the LLMs, achieving dynamic mapping between visual scenes and safety regulations. In the reasoning and decision-making module, we use a reasoning model, equipped with scene perception results and related safety knowledge, a FusedChain prompting strategy is adopted to guide the reasoning model in step-by-step hazard identification and compliance evaluation. This process eventually determines whether potential safety hazards exist and identifies their specific types.

This framework integrates three core modules and involves key technologies such as CLIP, YOLOv10, RAG, and LoRA. Detailed definitions of these technologies can be found in

Appendix A (Glossary of Key Technical Terms). The implementation logic of each module will be elaborated in detail below.

3.2. Target Detection and Preprocessing

To accurately locate workers and extract regions of interest, the YOLOv10 model is adopted as the object detector [

25]. YOLOv10 employs an end-to-end detection architecture consisting of a backbone network, a neck structure, and a detection head. Given an input image of a construction scene, the model extracts multi-level visual features and outputs a set of bounding box parameters

, including the normalized center coordinates

, width and height

, confidence score

, and class label of each detected object

. In this study, the YOLOv10 model is used with an input resolution of 640 × 640, and the confidence threshold is set to 0.6.

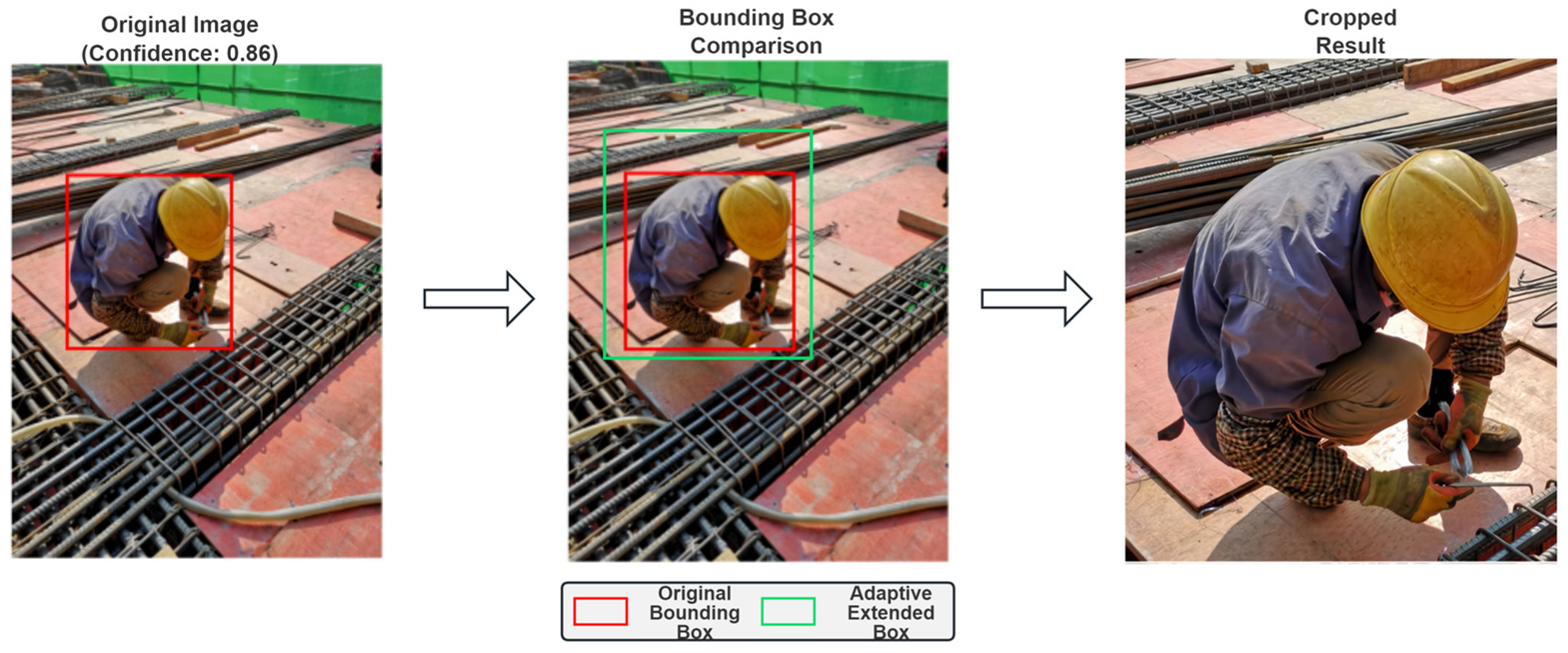

To mitigate the negative impact of truncated detection boundaries on subsequent tasks, this study introduces an adaptive bounding box expansion strategy. Specifically, the normalized bounding box parameters are mapped back to the original image coordinate system, and the boundaries are dynamically expanded according to Equation (1) to preserve the contextual information around the detected objects. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the original bounding box (red) truncates the worker’s local features, whereas the adaptively expanded box (green) preserves the worker and contextual scene, yielding more effective crops for semantic matching.

where

are the pixel coordinates,

,

, and the expansion coefficient

is set to 0.1 after optimization through grid search.

For the expanded regions of interest (ROI), a combined approach of bilinear interpolation and zero-padding is applied for size normalization. Each region is first resized so that its shorter side is an integer multiple of , while preserving aspect ratio, and then zero-padded to reach a final size of . Then, any remaining blank areas are filled with zero-valued pixels along the edges to reach the target resolution. Through this process, all ROIs are standardized to a uniform resolution before being fed into downstream tasks. This design helps reduce background noise and improves the robustness of semantic matching in subsequent modules.

3.3. Semantic Alignment

After obtaining worker-region images from construction scenes, the CLIP model based on contrastive learning is used for scene understanding [

26]. To address the high computational cost and overfitting risk of full fine-tuning, LoRA is applied to the self-attention layers of both the image and text encoders in CLIP [

27]. Specifically, the pretrained weights W are frozen, and two low-rank matrices A and B are introduced and trained to approximate the parameter updates efficiently [

28]. This approach reduces the number of trainable parameters while preserving model performance, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

During fine-tuning, the LoRA rank is set to , and a dropout rate of is applied to the LoRA inputs to mitigate overfitting. The model is optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of , scheduled with a cosine annealing strategy to ensure stable convergence. The total number of training iterations is defined as 500 N/K, where is the total number of samples and is the number of categories, ensuring sufficient learning under few-shot conditions. A batch size of 32 is adopted to balance memory usage and training efficiency, allowing the entire fine-tuning process to run on a single 24-GB GPU.

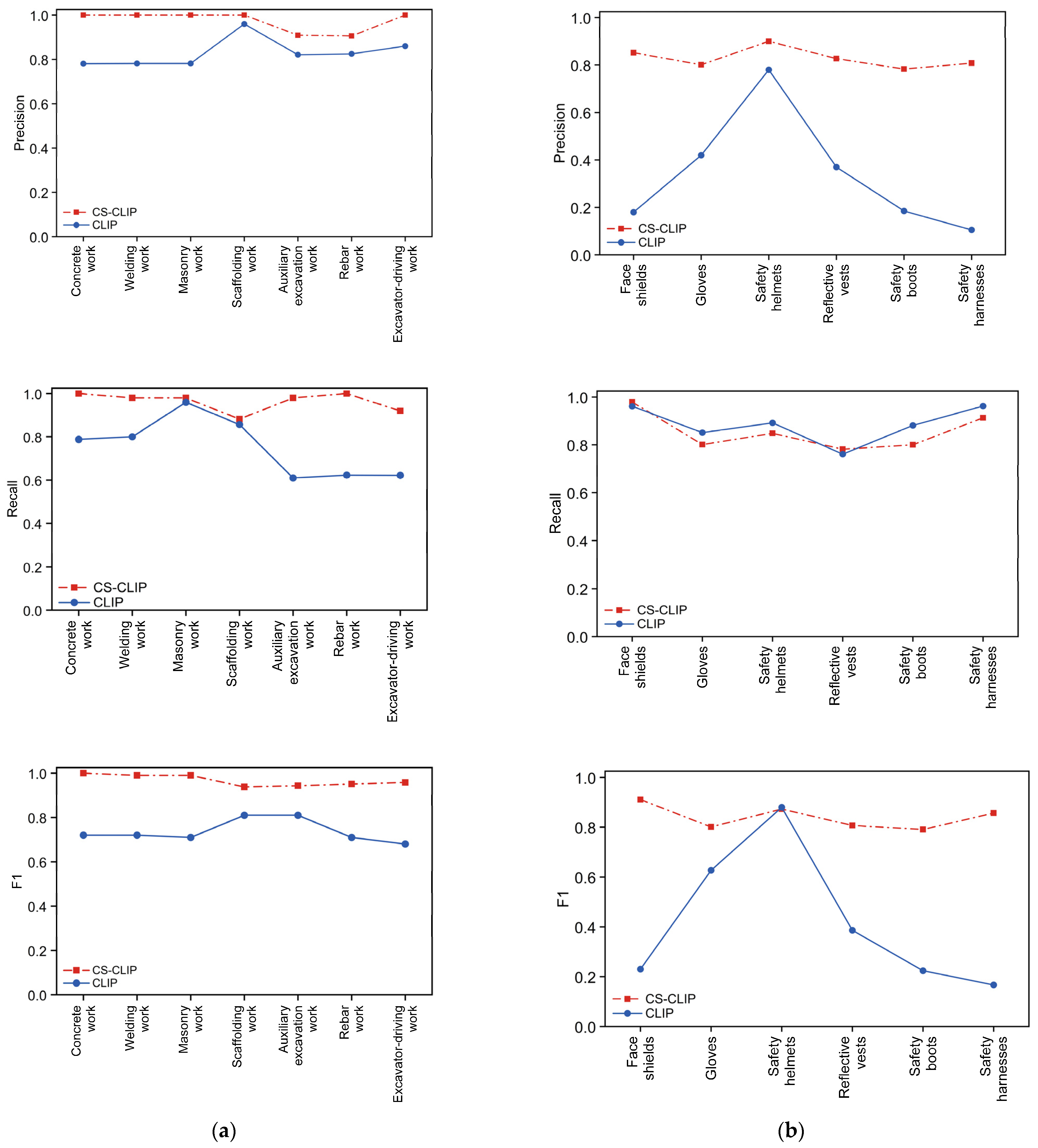

As shown in

Figure 4, construction activity recognition and PPE detection are jointly performed based on the CLIP model. For activity recognition, textual descriptions of construction activities and scene images are separately encoded by the pretrained text and image encoders, and the cosine similarity between each text–image pair is computed. The activity description with the highest similarity score is selected as the final prediction. For PPE detection, both positive and negative descriptions of each protective equipment are compared with the image features in the same way. If the similarity with the positive description exceeds that of the negative description, the worker is determined to be wearing the corresponding PPE. As illustrated in

Figure 4, this unified similarity-based inference (applied to both activity and PPE tasks) outputs per-worker activity labels and PPE statuses, enabling integrated scene understanding.

3.4. Knowledge Graph Construction and Hybrid Retrieval

Identifying construction safety hazards requires not only accurate interpretation of scene information but also the combination of information with relevant regulations to provide interpretable professional analysis. To achieve this goal, we constructed a construction safety knowledge graph and proposed a knowledge retrieval method based on this graph. This approach ensures that the retrieval process maintains both semantic relevance and strictly abides by the rules and restrictions, thereby effectively integrating scene understanding information with domain knowledge.

The core knowledge sources of the knowledge graph include construction safety standards and historical safety incident reports. The safety standards, which define behavioral requirements for workers and specify conditions for determining rule violations, are based on Chinese national construction safety regulations such as GB 50870–2013 [

29] and GB 51210–2016 [

30]. Historical incident reports document accidents caused by such violations and provide information about causes, hazard types, and the consequences of missing PPE or unsafe behaviors.

For the construction safety domain, we defined four types of core entities: Worker, Behavior, Safety_Rule, and Hazard. The entity set of the construction safety knowledge graph can be formalized as:

where

denotes the entity set, representing on-site workers or generalized roles performing operations at construction sites;

refers to the set of construction activity types, corresponding to specific work tasks conducted by workers;

represents the safety rule set;

stands for the set of potential safety incident types.

The relations are designed to capture the causal chains linking work scenarios, safety rules, and potential risks. Centered on the entities, we define six types of relationships, and the relationship set can be expressed as:

The specific constraints can be formalized as follows:

where

indicates that a worker carries out a specific behavior, representing the particular task a worker is engaged in;

specifies that a behavior must adhere to a given safety rule, defining the safety norm corresponding to the behavior;

links a behavior to a specific risk, identifying potential hazards that the behavior may lead to;

signifies that a safety rule can reduce or prevent a certain risk, explaining how rule compliance lowers risk exposure;

reflects whether a worker has followed a specific safety rule, used to check the worker’s adherence to regulations;

denotes that a worker is exposed to a certain risk, inferred based on the worker’s behavior and rule compliance status;

represents the fact set.

The primary focus of the proposed knowledge graph is to capture the causal relationships between worker behaviors and associated hazards, which are represented using an unweighted graph. It is assumed that behavior entities serve as the endpoints of accident chains, meaning that no causal links exist between accidents themselves. If a single behavior is associated with multiple accidents, it is considered that this behavior independently triggers each of these accidents. Accordingly, the triples in the knowledge graph can be represented as:

Here, denotes the knowledge graph, where each element is a triple . represents the set of entity names, containing head and tail entities, with a total size of ; denotes the set of relations between entities, with a total size of ; represents the fact set, where each triple corresponds to a fact.

We constructed a construction safety knowledge graph comprising 5 types of agents, 43 types of behaviors, 86 safety regulations, 97 risk categories, and 227 types of construction activities, covering various unsafe behaviors, accident causes, and safety regulations. The completed knowledge graph was stored and managed using Neo4j, which enables efficient processing of complex entity–relation queries [

31].

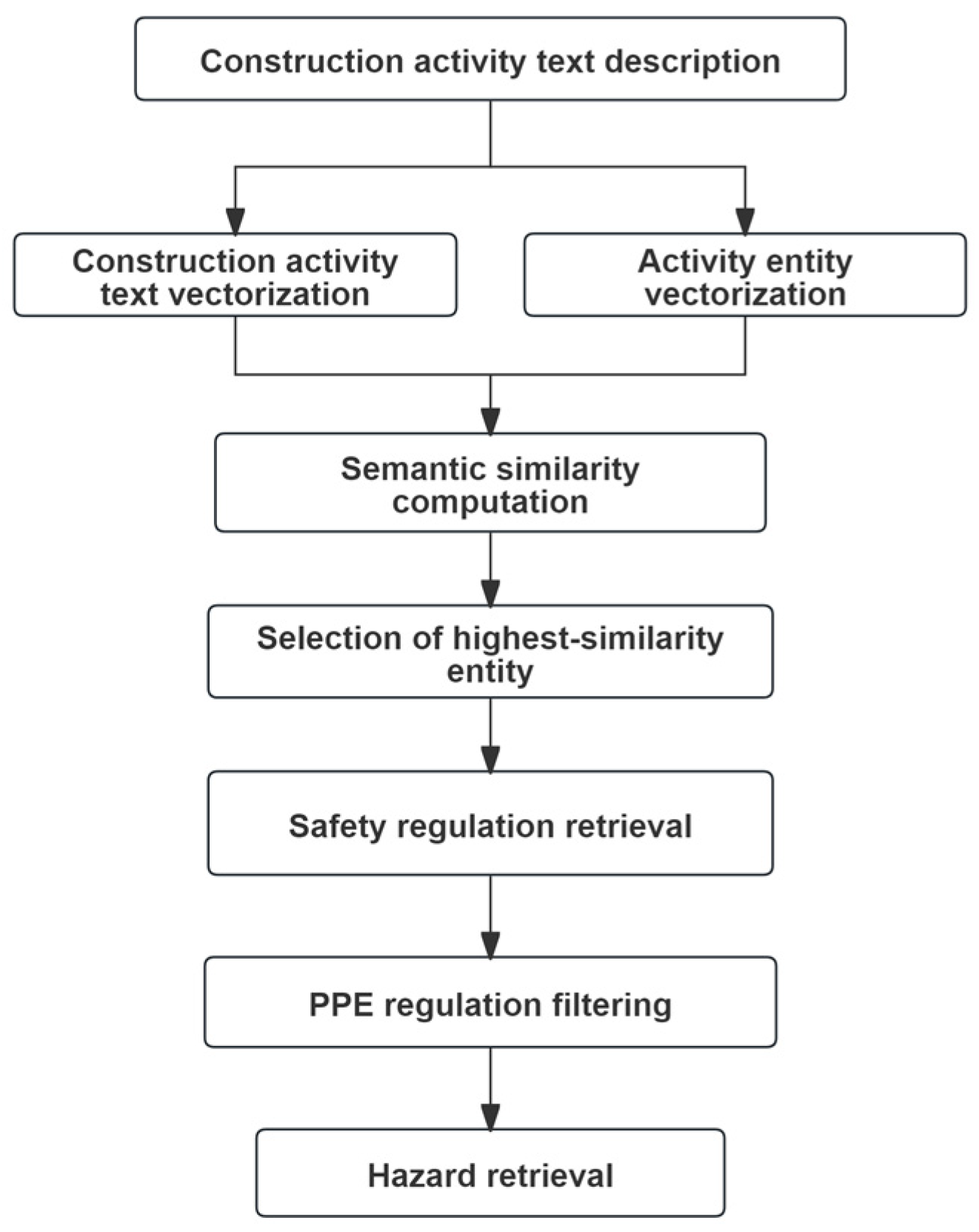

During the retrieval process, we integrated knowledge graph reasoning with text embedding techniques to form a hybrid retrieval strategy, as illustrated in

Figure 5. First, a general embedding model (BAAI General Embedding, BGE) is used to embed information about workers’ construction activities and activity entities from the knowledge graph into the same vector space [

32]. The semantic similarity between the construction activity information and all activity entities in the knowledge graph is then calculated. Based on high similarity scores, the relevant activity type is selected, and after matching with the corresponding entity, all related regulatory information associated with that entity is retrieved. Given the context length limitations of LLMs, not all relevant regulations can be used as prompt input. Subsequently, the retrieved regulatory entities are embedded into the same vector space, similarities are computed, and the regulations most relevant to the worker’s behavior are selected by ranking. This retrieval strategy ensures that the results are not only semantically relevant but also comply with regulatory requirements, while maintaining efficiency and traceability.

3.5. Reasoning and Decision-Making

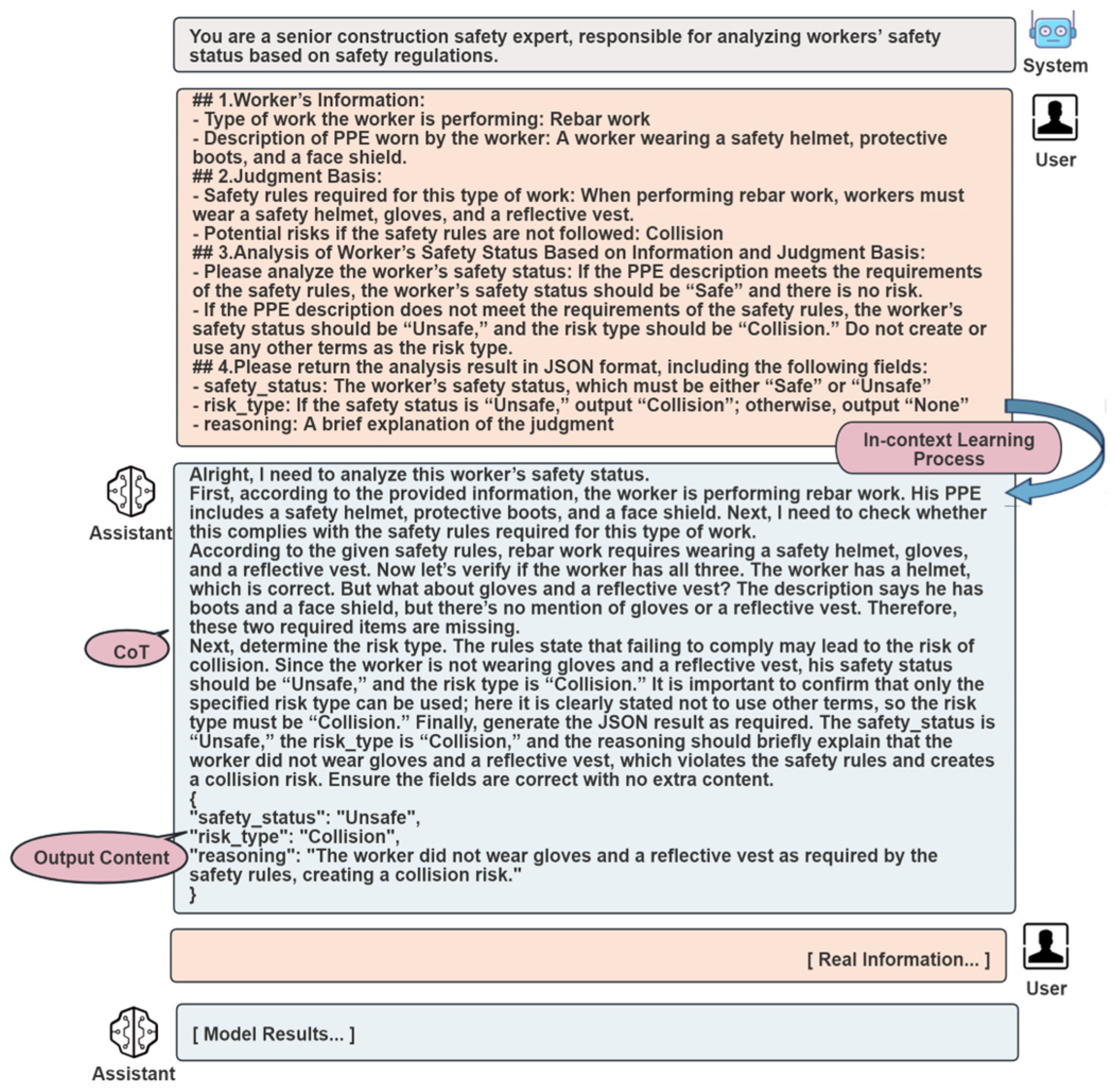

After retrieving relevant knowledge, the next step is to use this information for safety hazard reasoning. To achieve this, we propose a FusedChain prompting method, which integrates In-Context Learning (ICL) [

33], few-shot learning, and CoT [

34] approach. This method combines CoT reasoning and few-shot demonstrations directly within the ICL framework to form a multi-layered prompt structure.

Figure 6 illustrates the FusedChain prompt template: define a safety expert role and rules, demonstrate Chain-of-Thought reasoning via a sample Q&A, then apply the template to real scene inputs for formal safety analysis.

First, use the system prompts to establish a behavioral framework and operational guidelines for the LLM. Then, through the User and Assistant parameters, construct an in-context learning example to help the LLM understand the current task and ensure that its output is not only factually accurate but also contextually appropriate. Finally, the CoT technique is used to guide the LLM to reason step by step, generate conclusions, and explicitly refer to relevant safety regulations. By decomposing the reasoning process into progressive steps, the FusedChain strategy enhances the analytical capability and interpretability of the model, ensuring that the generated conclusions are reasonable and evidence-based.

Considering the deployment cost and resource constraints in practical engineering applications, we prioritized open-source models with relatively small parameter sizes. Specifically, we adopted the lightweight DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B (DeepSeek-R1-7B) as the core reasoning model. The detailed parameter settings of the model are presented in

Table 1.