1. Introduction

Urban lighting plays a vital role in shaping the nighttime identity, safety, and visual comfort of cities. Beyond its technical and aesthetic dimensions, illumination is increasingly recognized as a medium that expresses cultural meaning and contributes to sustainable urban life. Nevertheless, most urban lighting studies have traditionally focused on design, emphasizing photometric performance, luminance distribution, or visual perception, while often overlooking spatial integration and contextual relationships with heritage, demographics, and environmental sensitivity.

Geographic Information Systems (GISs) have proven powerful in integrating spatial data into urban decision-making across fields such as transportation, landscape planning, and environmental monitoring.

Yet, their application to lighting master planning, particularly within heritage-sensitive urban environments, remains limited. Existing studies have mainly explored city-scale energy optimization [

1,

2] or localized visual perception analysis [

3,

4], with few attempts to connect cultural identity, population dynamics, and lighting demand in a spatially integrated manner.

This study addresses this research gap by developing a GIS-based framework that links lighting priorities with cultural heritage, demographic structure, and environmental context. Unlike previous approaches, it employs high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery (10 m), CORINE 2024 data, and population density maps to enhance spatial precision in identifying lighting demand zones. The framework integrates five key factors—land cover, parks, heritage structures, population distribution, and public institutions—through a weighted overlay model, which is further refined via sensitivity testing to ensure methodological robustness. It hypothesizes that combining high-resolution spatial and demographic data significantly improves the contextual accuracy and practical applicability of lighting master plans in heritage-sensitive environments.

The model was validated through field verification and expert review. Its performance was assessed using three indicators: improvement in spatial precision over CORINE-based analyses, consistency between model results and field observations, and compliance with international lighting standards, including CIE 150:2017 [

5] and IES RP-8-18 [

6]. By aligning illumination planning with cultural and demographic realities, this research reframes urban lighting as an instrument of spatial communication and identity formation rather than a purely technical utility. The Niğde case study provides a representative example of a medium-sized Anatolian city where historical continuity and modern urban growth coexist, presenting both challenges and opportunities for sustainable, heritage-conscious lighting design. The proposed framework contributes a replicable, data-driven methodology for other medium-sized cities seeking to balance functionality, visibility, and cultural preservation through evidence-based illumination strategies.

Furthermore, urban lighting planning is directly related not only to visual comfort and safety but also to light pollution, ecological sensitivity, and sustainability principles. This study advances the existing literature by linking cultural heritage-centered lighting planning with light pollution, the nighttime ecosystem, and human-centric lighting approaches. In accordance with international standards [

5,

6], both nighttime visibility and environmental impacts were evaluated. An additional monitoring checklist for field verification, glare, uniformity, and ecological impacts was included within the methodology.

1.1. Literature Review

Urban lighting research has evolved from purely technical studies of luminance and glare control toward a broader understanding of illumination as a spatial, social, and environmental phenomenon. Early works primarily addressed visual comfort and street safety, while later studies recognized lighting as a key component of urban livability and cultural expression. Recent research emphasizes that lighting planning should not only ensure visual performance but also contribute to the legibility, identity, and ecological resilience of cities [

3,

4,

7]. Within this paradigm shift, Geographic Information Systems (GISs) have become increasingly relevant, providing spatial tools for modeling illumination demand, assessing accessibility, and evaluating nighttime visibility in urban environments [

8,

9]. However, despite the growing use of GIS in environmental and landscape planning, its application to lighting master plans—particularly in heritage-sensitive contexts—remains underdeveloped.

Recent standards, such as the CIE 150:2017 [

5] Guide on the Limitation of the Effects of Obtrusive Light from Outdoor Lighting Installations and the IES RP-8-18 [

6] Roadway Lighting Standard, provide quantifiable criteria for luminance uniformity, glare limitation, and environmental protection.

Yet, these standards are rarely operationalized spatially in planning studies. Integrating such normative frameworks into GIS-based analyses can translate abstract photometric thresholds into spatially actionable lighting priorities, ensuring that heritage areas and ecological zones receive context-sensitive illumination rather than uniform technical solutions. This perspective supports the growing trend toward sustainable and adaptive lighting, where visibility, comfort, and environmental protection are jointly optimized [

10,

11].

Environmental and ecological dimensions of lighting have also gained increasing attention. Studies indicate that excessive artificial illumination can alter circadian rhythms, disturb nocturnal biodiversity, and contribute to energy inefficiency and light pollution [

12,

13]. The CIE 150:2017 [

5] standard explicitly recommends limiting upward light ratios and controlling correlated color temperature (CCT) in ecologically sensitive zones—principles that align closely with GIS-based zoning approaches. However, despite this knowledge, empirical mapping of lighting intensity, environmental sensitivity, and visual impact remains scarce in many developing urban contexts. Within this growing body of research, only a limited number of studies have attempted to integrate cultural heritage and spatial data analysis into illumination planning. Works such as Zielinska-Dabkowska (2019) [

4] and Casciani (2020) [

3] discuss lighting design for historical settings but focus primarily on architectural expression rather than spatial prioritization. Similarly, environmental studies have explored illumination in the context of landscape character and visual perception, but have rarely linked these dimensions with population activity or cultural memory. Consequently, there remains a clear need for heritage-sensitive, spatially explicit, and data-driven lighting frameworks that connect cultural significance with contemporary sustainability criteria.

This study responds to that need by developing a GIS-based methodology that synthesizes multiple layers—land cover, population density, parks, protected heritage, and institutional functions—to generate lighting priority maps consistent with international standards. By integrating spatial analysis with cultural context, the framework extends the current state of research beyond perception and aesthetics toward policy-relevant, spatially verifiable planning practice.

1.1.1. CORINE Land Cover Classification

Land cover is a key determinant of urban lighting demand because it reflects the spatial distribution of built, vegetated, and open areas within the city. The CORINE (Coordination of Information on the Environment) land cover database has long provided a standardized European framework for identifying surface categories relevant to environmental planning and policy. However, the 30 m resolution of traditional CORINE datasets—derived from Landsat imagery—often fails to capture the fine-grained complexity of compact historic districts. Recent studies emphasize that medium-sized heritage cities require higher-resolution satellite data to accurately map urban morphology and illumination patterns [

14,

15]. In this study, CORINE 2024 data were integrated with Sentinel-2 MSI Level-2A imagery (10 m) to enhance spatial precision and reduce generalization errors in the delineation of dense urban fabrics. Combining raster and vector layers allowed for a more nuanced classification of built-up zones, differentiating continuous urban fabric, discontinuous settlements, and industrial or transportation areas. This hybrid approach improved the accuracy of lighting zone delineation and provided a robust empirical basis for evaluating illumination priorities in both heritage and modern urban contexts. The methodology aligns with best practices in urban spatial analysis (Papadimitriou et al., 2021) [

8] and supports the CIE 150:2017 [

5] guidance on minimizing obtrusive light through context-sensitive planning.

1.1.2. Parks

Urban parks are critical public spaces that shape nocturnal mobility, recreation, and social safety. Well-lit green areas contribute to citizens’ physical and psychological well-being, while poorly illuminated ones may reduce accessibility after dark [

16].

In lighting master planning, park illumination must balance functional visibility, user comfort, and ecological sensitivity, in line with IES RP-8-18 recommendations for pedestrian zones. Previous GIS-based studies have analyzed accessibility using buffer distances from residential or transport nodes [

17], but such straight-line buffers often ignore pedestrian network constraints.

In this study, park accessibility was modeled through network-based buffers derived from OpenStreetMap pedestrian data, calibrated by population density and validated through field observations. Each park’s lighting priority was evaluated using multi-criteria spatial assessment, considering accessibility, size, vegetation density, and proximity to residential areas. The results were cross-referenced with ecological sensitivity criteria based on CIE 150:2017 [

5], ensuring that illumination intensity and color temperature minimize light spillover into adjacent green areas. This dual focus on user safety and ecological protection reflects current sustainability-oriented approaches to urban landscape lighting [

7,

11].

1.1.3. Protected Areas and Historical Structures

Protected areas and historical structures embody the cultural and architectural identity of cities. Illumination of these sites requires a careful balance between visual enhancement, heritage conservation, and energy efficiency. Research highlights that adaptive lighting can reinforce the legibility and symbolic importance of historical landmarks while minimizing material degradation and visual clutter [

3,

4]. However, accurately mapping such structures within GIS frameworks remains challenging, as heritage parcels often exhibit irregular morphology and dense spatial clustering.

To address this, the “Protected Areas and Historical Structures” layer in this study was refined using Sentinel-2 MSI imagery (10 m, July 2024) and verified through targeted field observations in Niğde’s historical core. This high-resolution approach corrected spatial inaccuracies inherent in CORINE data and enabled differentiation of courtyards, narrow streets, and open spaces surrounding heritage buildings. The prioritization model integrated three main criteria—accessibility, visibility, and architectural integrity—following international heritage assessment frameworks [

18,

19]. Scoring was conducted through expert evaluation by art historians and urban planners, ensuring that lighting recommendations aligned with authenticity, cultural meaning, and conservation ethics.

1.1.4. Population

Population distribution and nighttime activity patterns play a decisive role in determining illumination demand. Traditional planning approaches often rely on administrative population data, which fail to reflect real-time or temporal variations in urban use. Recent GIS-based studies [

20,

21] advocate integrating demographic indicators—such as age structure, density gradients, and mobility flows—to improve lighting equity and responsiveness. In this study, population data were analyzed both spatially and temporally to capture the demographic drivers of lighting needs. The analysis incorporated official census data and derived nighttime population proxies, such as built density and land-use intensity, to produce dynamic lighting demand surfaces.

The results demonstrated that population age composition and density strongly influence the spatial distribution of illumination priorities, particularly around educational, commercial, and recreational nodes. This approach aligns with the growing emphasis on social sustainability in lighting master planning and provides a foundation for adaptive, user-centered illumination strategies that evolve with demographic shifts.

1.1.5. Important Government Institutions

Government and administrative buildings represent significant nodes of nighttime visibility and civic activity. Their illumination contributes not only to urban functionality but also to the symbolic communication of authority, accessibility, and civic identity. In most cities, such buildings occupy strategic urban locations, plazas, intersections, or historic precincts—where lighting can reinforce urban hierarchy and visual orientation. However, many municipal lighting programs still treat government facilities as isolated infrastructure elements rather than as integral components of the city’s spatial identity.

In this framework, government institutions were evaluated as essential attractors of nighttime movement and visibility. GIS-based mapping integrated their spatial distribution with proximity to major roads, heritage zones, and population density clusters. Each facility’s lighting priority was assessed using a weighted overlay model that considered accessibility, functional hours, and symbolic importance. The findings underscore the need for consistent illumination standards across civic zones to ensure continuity of nighttime legibility and safety, in line with the visual uniformity principles outlined in IES RP-8-18 [

6]. By embedding institutional lighting within broader spatial planning, the study advocates for a cohesive approach that merges functionality, heritage awareness, and energy-conscious governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and General Methodological Framework

This study was conducted in the Central District of Niğde, located in central Türkiye between 34°30′10″–34°45′00″ E longitude and 37°54′00″–38°06′30″ N latitude. Niğde was selected due to its high concentration of cultural heritage, extensive settlement history, and diverse land use patterns. Situated within the historic Cappadocia region, the city has evolved under successive civilizations, including the Hittites, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, and Ottomans. Its combination of dense urban fabric, peri-urban agricultural land, and underlit heritage structures makes Niğde a representative case for developing an evidence-based lighting master plan that integrates security, aesthetics, and cultural identity. The methodology integrates five spatial factors to assess and prioritize lighting demand:

- (1)

Land cover data (based on the CORINE Land Cover 2024 classification refined by Sentinel-2 imagery);

- (2)

Public parks and open spaces;

- (3)

Protected areas and historical structures;

- (4)

Population density and temporal activity patterns;

- (5)

Key government institutions.

These layers were selected for their spatial relevance to nighttime visibility, cultural representation, and public safety. Each factor was scored on a 1-to-5 scale according to criteria such as accessibility, usage intensity, heritage value, and visual prominence. To ensure transparency, equal weights were initially assigned to all factors; a sensitivity analysis (

Section 3.8) was later performed to test alternative weighting scenarios and confirm model robustness. Spatial analyses were conducted using ArcMap 10.1 and QGIS 3.30, supported by Python 3.9 (ArcPy) for model automation.

Raster data (e.g., CORINE, Sentinel-2, ASTER GDEM) and vector data (e.g., parks, government institutions, and heritage sites) were integrated under a common spatial reference (UTM Zone 36N, EPSG:32636). The “Reclassify” and “Weighted Overlay” tools were applied to standardize scores across datasets and generate a composite lighting priority map identifying areas where multiple urban values converge. To improve spatial accuracy, the CORINE dataset was refined with Sentinel-2 MSI imagery (10 m resolution, July 2024) and field verification data. This integration addressed limitations of 30 m raster sources, particularly in compact historical districts. DEM-based visibility models were employed to represent elevation and topographical constraints, though dynamic and seasonal variables (e.g., vegetation, atmospheric effects) remain outside the present analytical scope. Despite these constraints, the approach provides a replicable, data-driven framework for mid-sized cities with limited lighting infrastructure. It demonstrates how geospatial tools can align lighting functionality with cultural and environmental context, thereby reinforcing Niğde’s visual identity and safety at night.

2.2. Land Cover and Satellite Data

Land cover was analyzed using Sentinel-2 MSI Level-2A multispectral imagery (10 × 10 m spatial resolution), providing high-quality surface information suitable for medium-scale urban analysis. The imagery, acquired in July 2024, was atmospherically corrected using the Sen2Cor processor and processed through the visible (B2, B3, B4) and shortwave infrared (B11, B12) bands. A supervised classification was performed in ArcMap 10.1 using the Random Forest algorithm, which offers superior accuracy and robustness compared to conventional maximum likelihood approaches. The Central District of Niğde was categorized into four primary land-cover classes: built-up areas, agricultural lands, vegetation and semi-natural areas, and water bodies (

Table 1). These classes were further subdivided according to the CORINE Land Cover 2024 nomenclature, ensuring compatibility with European land-cover frameworks.

Within the urban core, built-up areas were analyzed in greater detail due to their constant human activity and visual importance. Subclasses such as continuous urban fabric, discontinuous settlements, industrial zones, and transportation corridors were extracted to capture fine-scale variations relevant to lighting demand. In contrast, agricultural and vegetated zones were retained at a broader classification level, as they generally require limited or no artificial lighting.

Training samples for the supervised classification were derived from field surveys, municipal base maps, and OpenStreetMap data, ensuring both thematic accuracy and spatial consistency. Each land-cover type was assigned a lighting requirement score ranging from 1 to 5, reflecting its functional and visual importance. For example, continuous urban fabric received the highest score (5 points) due to dense building coverage, pedestrian activity, and nighttime visual prominence, whereas agricultural and forested lands received the lowest scores (1–2) because of minimal human activity and ecological sensitivity to artificial light.

The use of Sentinel-2 imagery, supplemented by ASTER GDEM (30 m) for elevation modeling, substantially improved the spatial resolution and topographic accuracy of the analysis compared to Landsat- or CORINE-only datasets. The 10 m pixel size allowed for the detection of small-scale morphological features—such as narrow streets, courtyards, and isolated historical structures—that are typically obscured in coarser raster sources. To minimize boundary inconsistencies between raster and vector datasets, all layers were resampled to a unified 10 m grid and co-registered under the UTM Zone 36N (EPSG:32636) coordinate system. The integration of Sentinel-2, CORINE, and ASTER data established a multi-source analytical framework, providing a reliable spatial foundation for the lighting master plan. This approach ensured a balance between resolution, coverage, and analytical feasibility, while maintaining compatibility with European environmental databases.

2.3. Parks and Green Spaces

Public parks were evaluated using three primary criteria: (1) accessibility, (2) landscape value, and (3) visibility—each contributing to a composite score indicating lighting priority. This approach reflects the dual role of parks as social hubs and ecological refuges, requiring lighting strategies that balance safety, functionality, and environmental sensitivity.

2.3.1. Accessibility

Accessibility was analyzed through a network-based pedestrian service area approach, rather than Euclidean distance buffering, to more accurately represent real walking routes and public access behavior in urban environments. Pedestrian pathways were derived from OpenStreetMap (OSM) and refined through field observation. Service areas of 100 m, 300 m, and 500 m were generated in ArcGIS 10.8.2 Pro Network Analyst, corresponding to typical walking distances used in urban accessibility studies. Accessibility was scored as follows: ≤ 100 m (5 points), 100–300 m (4 points), 300–500 m (3 points), 500–800 m (2 points), > 800 m (1 point). This method reflects walkable access patterns and aligns with pedestrian-scale lighting needs. Field checks conducted in February–May 2024 confirmed the validity of pedestrian routes and the connectivity logic used in the network model.

2.3.2. Landscape Value

Landscape value was evaluated using a structured checklist of 10 indicators adapted from urban landscape and recreation studies [

22,

23]. Each attribute present at a park scored 1 point, with a maximum of 10. Indicators include:

Proximity to historical/architectural sites;

Water features (ponds, fountains);

Food & beverage amenities;

Monuments/sculptures;

Mature trees/preserved vegetation;

Historic landscape elements;

Panoramic/view corridors;

Urban design amenities (paving, pergola, seating);

Sports/recreation facilities;

Material and functional diversity.

To enhance objectivity, checklist scores were cross validated through two independent reviewers and municipal landscape documentation. This structured approach ensures that landscape evaluation reflects both cultural significance and functional value.

2.3.3. Visibility

Visibility analysis was conducted to determine the visual prominence of parks within the urban landscape and to identify areas where lighting interventions would have the strongest perceptual and navigational impact. A digital surface model (DSM) was generated by integrating ASTER GDEM (30 m) with building height estimates derived from OpenStreetMap building footprints and supplemented through field measurements using a handheld laser rangefinder. A line-of-sight and viewshed analysis was performed in ArcGIS Pro 3D Analyst, enabling evaluation of visibility from key pedestrian corridors, central squares, and elevated vantage points across the city. Vegetation canopy height was incorporated using select tree height samples collected during field survey campaigns, ensuring a realistic representation of visual obstructions.

Visibility scores were assigned based on the proportion of park area visible from public routes and urban landmarks, standardized on a five-point scale. Parks with greater visual exposure and strategic orientation toward pedestrian flows received higher scores, reflecting their stronger contribution to nighttime legibility and perceived safety. To validate the model outputs, field observations were conducted during evening hours to compare predicted and observed visibility conditions. A high level of agreement was found between modeled and real-world visibility conditions (82% correspondence), confirming the effectiveness of the spatial modeling approach. This visibility component ensures that parks prioritized for lighting contribute not only to safety but also to urban image, spatial orientation, and nocturnal place identity, in accordance with international guidance on nighttime visual hierarchy and perceptual comfort (CIE 150:2017) [

5]. The three criteria were combined using equal weights to generate a Park Lighting Priority Score (PLPS), normalized between 0 and 1. Results were validated through on-site illumination observations and municipal lighting data, achieving 85% predictive agreement, confirming the model’s suitability for identifying priority parks for lighting upgrades. These multi-criteria validated assessment aligns with CIE 150:2017 [

5] guidance for minimizing unnecessary light spill in natural areas while supporting social and recreational nighttime use in public parks. The methodology supports a balanced approach to urban lighting, ensuring safe and vibrant nighttime public spaces while protecting ecological sensitivity.

2.4. Evaluation of the Protected Areas and Historical Structures

Protected areas and historical structures form the cultural backbone of Niğde, shaping its urban identity and contributing to its visual and symbolic prominence at night. These sites serve as navigational anchors, heritage markers, and social reference points, making them essential to the development of a culturally sensitive and context-aware lighting master plan. In this study, registered heritage buildings and conservation areas were evaluated through three primary criteria: (1) accessibility, (2) visibility, and (3) architectural integrity. Accessibility and visibility were quantified through GIS-based proximity and line-of-sight analyses integrating transportation corridors, elevation data, and urban morphology. These metrics capture both potential and symbolic visibility within nighttime cityscape perception.

Architectural integrity was assessed using five categories adapted from international heritage protection frameworks [

24,

25], ranging from 5 (excellent authenticity) to 1 (severely altered or degraded). Expert evaluation was conducted in collaboration with faculty members from the Department of Art History at Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, who participated in field assessments, reviewed archival restoration documents, and ensured adherence to authenticity and conservation principles. To formalize and strengthen the evaluation process, the three criteria were weighed using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Expert judgments produced a consistency ratio (CR) of 0.06, confirming logical consistency in decision inputs and reinforcing methodological reliability. The resulting Heritage Lighting Priority Score (HLPS) was computed for each structure and normalized for spatial modeling. Spatial precision was enhanced by refining the “Protected Areas and Structures” layer using Sentinel-2 MSI Level-2A imagery (10 m, July 2024) and detailed on-site visual verification, particularly within the historic urban core. Sentinel imagery supported the extraction of fine-scale morphological elements—including narrow alleyways, courtyard pockets, rooflines, and open forecourts—that are often generalized or omitted in conventional land-cover datasets. Cadastral records and field sketches were used to manually adjust polygon boundaries and verify structural outlines.

A field-based nighttime visibility survey and photometric observation campaign were conducted to cross-check modeled visibility outputs, confirming strong correspondence between GIS predictions and real-world perceptual prominence. This validation step strengthens confidence that lighting recommendations promote both heritage legibility and responsible illumination, consistent with CIE good-practice principles emphasizing over-lighting avoidance in sensitive historical zones (CIE 150:2017) [

5]. Through this integrated remote-sensing, architectural assessment, and field-validation approach, the study establishes a scientifically grounded framework for illuminating culturally significant sites in Niğde. The method ensures that lighting enhances the nighttime presence of heritage assets while safeguarding authenticity, supporting sustainable tourism, and reinforcing collective urban memory.

2.5. Population and Nighttime Activity

Population distribution is a major determinant of nighttime lighting demand, as higher concentrations of residents typically correlate with increased requirements for safety, social interaction, mobility, and commercial activity. Population data for 30 neighborhoods and 47 rural settlements in Niğde’s Central District were obtained from the Turkish Statistical Institute. Instead of relying solely on administrative population categories defined by the Turkish Village Law (Law No. 442), this study incorporates a spatially continuous population density surface, generated through the integration of TÜİK census values with OpenStreetMap (OSM) building footprints. A dasymetric mapping approach was used to redistribute population counts into 100 m grid cells, providing a more realistic representation of settlement intensity and nocturnal human presence. Population-based lighting priority scores were assigned as

Table 2.

To better reflect nighttime urban behavior, a nighttime activity index was derived using points of interest (commercial, educational, hospitality, and transportation facilities) and adjusted using Google Community Mobility Reports (2023–2024). This ensured that areas with strong evening activity patterns (e.g., central commercial districts, university vicinity, public squares) received higher priority regardless of administrative classification. This approach captures both spatial density and temporal usage patterns, ensuring that lighting decisions respond to actual human activity rather than static legal categories. To verify spatial coherence, the modeled population density surface was compared against municipal land-use plans and observed nighttime activity during field surveys (May–August 2024), demonstrating strong agreement between modeled intensity and real-world usage patterns. Although Niğde shows moderate outward migration trends, dynamic migration data were not integrated due to limited temporal granularity at sub-district scales. However, the model accounts for hourly evening activity patterns, an important determinant of urban lighting demand documented in contemporary urban lighting studies [

5,

6]. Future research may expand temporal resolution by integrating anonymized mobile-device mobility data into further models of seasonal and hourly variations. By incorporating population density, built-form intensity, and evening activity into the lighting master plan, this study supports energy-efficient, equitable, and behavior-responsive illumination strategies that align lighting levels with patterns of use and community presence at night.

2.6. Government Institutions

Government institutions constitute key symbolic and functional nodes within the urban landscape, frequently operating beyond standard business hours and contributing to public safety, governance, and civic identity. Their nighttime visibility is essential for fostering a sense of security, reinforcing institutional presence, and guiding pedestrian and vehicular orientation within the city center. For this study, only high-visibility, high-accessibility government buildings with demonstrable nighttime relevance were included in the lighting priority model. These facilities encompass:

Courthouses;

Municipal administration buildings;

Post offices;

Police and military facilities;

Other core executive and administrative buildings.

Each identified institution was assigned a priority score of 5, reflecting its dual role in civic symbolism and nighttime functional relevance. This approach aligns with international urban lighting principles emphasizing hierarchical illumination for security, legibility, and governance [

5,

6]. Educational and healthcare facilities were intentionally excluded, not due to lack of importance, but because their lighting standards are typically governed by functional regulatory codes and rely predominantly on interior illumination and localized safety lighting. Additionally, these facilities exhibit limited public footfall during late hours relative to core civic buildings and including them would dilute the focus on structures whose illumination carries broader spatial and symbolic meaning. Institutional locations were derived from municipal GIS records and Ministry of Interior databases and subsequently validated through field verification and OpenStreetMap (OSM) cross-referencing. Nighttime activity levels were confirmed via on-site observation campaigns and public mobility datasets (2023–2024), ensuring that selected facilities demonstrably contribute to nocturnal urban dynamics. While all included institutions received uniform scores due to their consistent civic hierarchy, this assumption was tested through expert consultation and demonstrated acceptable consistency for medium-sized cities with centralized administrative cores such as Niğde.

In future applications, advanced weighting techniques (e.g., AHP or multi-criteria decision analysis) may be employed to differentiate institutional categories further in larger metropolitan contexts. By prioritizing government institutions that actively shape public experience and contribute to nighttime legibility and safety, this component reinforces the study’s broader emphasis on identity-driven, functionally responsive, and culturally coherent urban lighting planning.

2.7. GIS Mapping and Software

Spatial boundaries were defined using official municipal administrative zones and validated against cadastral parcels to ensure topographic consistency. For internal spatial comparability, all layers were harmonized to a 500 m analytical grid, allowing standardized evaluation across heterogeneous urban and peri-urban areas. This approach avoids arbitrary zoning, ensures scale consistency across maps, and aligns with urban lighting planning guidelines (CIE 150:2017) [

5]. All spatial analyses were performed in ArcMap 10.1 supported by the Spatial Analyst and 3D Analyst extensions. Sentinel-2 Level-2A imagery (10 m resolution, July 2024), ASTER DEM data, municipal cadastral layers, and field-survey GPS points formed the primary geospatial database. Raster layers (land cover, elevation) and vector layers (parks, heritage sites, government institutions, settlement boundaries) were integrated into a unified geospatial environment to develop a multi-criteria lighting prioritization model. Each of the five spatial factors—land cover, parks, protected historical assets, population distribution, and government institutions—was standardized to a 1–5 score range based on urban lighting demand, visibility, cultural significance, and nighttime activity relevance. The scoring system was operationalized through Reclassify, ensuring consistent comparability of mixed data formats. A Weighted Overlay (equal weight, 20% per layer) was applied due to the absence of a universally accepted weighting model for medium-sized heritage cities in lighting planning literature, and to avoid subjective bias in variable prioritization. Equal weighting also aligns with MCDA practices in early-stage illumination planning frameworks. Future studies may apply AHP or fuzzy-logic weighting to incorporate expert-based sensitivity calibration and user-derived decision criteria. The resulting cumulative lighting priority map was classified into five levels (very low to very high) representing areas where enhanced lighting would support safety, cultural identity, wayfinding, tourism visibility, and nighttime urban life. These classes also align with lighting hierarchy principles recommended by CIE 150:2017 and IES RP-8-18 for public realm illumination strategies.

2.7.1. Data Validation and Spatial Accuracy

To improve reliability and spatial precision,

Municipal maps, OSM data, and cadastral records were cross-checked;

Field GPS points and drone-based photographs (selected locations) verified feature boundaries;

Local control points minimized raster-vector edge displacements;

Manual refinement was applied within the historic core where narrow streets, courtyards, and fade-level geometry exceed Sentinel’s native 10 m resolution.

2.7.2. Methodological Limitations

Despite high-resolution data use, certain limitations remain:

Micro-architectural heritage elements (e.g., façade recesses, arcades) cannot be captured by 10 m Sentinel-2 pixels.

DEM-based visibility reflects static landscape conditions without seasonal vegetation or atmospheric change effects.

Population data represent a single temporal frame and do not yet reflect nighttime mobility, tourism peaks, or seasonal fluctuation patterns.

In future work, integrating mobile-network mobility datasets, CCTV-derived pedestrian metrics, and adaptive smart-lighting sensor data would enable dynamic illumination planning consistent with real-time urban behavior.

2.8. Sensitivity Analysis for Weighting Scenarios

To ensure the reliability and adaptability of the proposed lighting model, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate how different weighting configurations might influence spatial outcomes. In the main analysis, each of the five spatial factors—land cover, parks, protected and historical structures, population density, and government institutions—was assigned an equal weight of 20%. This approach was maintained in all primary maps and resulted in ensuring methodological neutrality and reproducibility. However, to test the robustness of the model and explore potential city-specific adaptations, three alternative weighting scenarios were simulated as comparative exercises (

Table 3). These were not used for the main results but served as a methodological extension to assess how sensitive the model is to changes in weighting assumptions.

The results were analyzed through a comparative GIS overlay, recalculating lighting priority scores under each weighting configuration. The map illustrates the spatial differences between the three alternative models compared with the baseline. Results showed that while the overall spatial pattern remained largely consistent, variations occurred in local priority classifications—particularly in zones where population density and heritage buildings overlapped. In the Heritage-Focused scenario (A), the historic core and adjacent cultural corridors (Ahipaşa, Kale, and Eskisaray neighborhoods) gained approximately 10–15% higher cumulative scores, confirming the model’s responsiveness to value-based weighting. Conversely, the Population-Focused scenario (B) shifted lighting priority toward the densely populated Efendibey and Dere districts, where demographic intensity dominates spatial demand. These results demonstrate that the model maintains structural stability under different weighting configurations, validating its robustness while also offering flexibility for city-specific customization (C).

Municipalities can adjust factor weights based on policy goals, whether heritage conservation, population safety, or civic prominence, without compromising the methodological consistency of the framework.

2.9. Field Validation & Nighttime Assessment

To ensure that spatial model output reflected real on-site lighting conditions, a structured nighttime assessment was conducted in the historic core and selected high-priority zones. Field observation was performed between 20:00 and 23:30 on two weekday nights and one weekend night during the summer period, when outdoor activity levels were high. The assessment followed a qualitative visibility and illumination checklist supported by photographic documentation and GPS notes. Observation points were selected based on the GIS-identified high-priority zones, including Alaaddin, Sırali, Eskisaray, Yenice, and A. Kayabaşı neighborhoods. Key parameters include the following:

Pedestrian visibility and facial recognition distance;

Uniformity and shadow zones;

Perceived safety and landmark readability;

Existing fixture type, orientation, and glare;

Presence of dark gaps and over-lit areas.

This study included lux-meter measurements for selected areas, and visual benchmarking was applied using reference illumination ranges suggested in CIE 150:2017 and IES RP-8-18, particularly for public squares and pedestrian corridors. Field observations aligned with GIS results, confirming insufficient illumination in several heritage structures and public parks within high-priority zones, where visibility gaps and weak façade lighting were noted. These findings reinforce the validity of the spatial model and highlight the need for targeted lighting upgrades in key public and heritage areas.

To complement the GIS-based analytical workflow, a structured field validation protocol was incorporated to verify nighttime conditions. Field checks were conducted at representative locations covering high-priority zones, heritage areas, and peripheral spaces. Observed conditions included the following:

Illuminance estimates based on standard reference points;

Visibility conditions and uniformity perception;

Glare occurrence and shadow formation;

Fixture type, pole height, and spacing;

Presence of uplight and skyglow;

Ecological sensitivity indicators (e.g., proximity to vegetation, nocturnal fauna activity).

This approach ensured consistency between spatial priorities and real-world conditions while aligning with sustainable lighting and dark-sky principles. The full field-audit matrices are provided in

Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Land Cover Analysis of Niğde’s Central District

The land-cover classification conducted using Sentinel-2 MSI Level-2A imagery (10 m spatial resolution; July 2024) indicates that approximately 95–96% of Niğde’s Central District consists of agricultural, vegetated, and semi-natural landscapes, with only ~4% representing artificial surfaces such as built-up zones, transportation corridors, and industrial units (

Figure 1). This land-use distribution is consistent with the region’s rural–urban structure and has direct implications for illumination strategy, energy efficiency, and environmental protection.

Within the artificial category, continuous urban fabric—primarily concentrated around the historic city core and mixed commercial–residential areas—demonstrated the highest need for artificial lighting. These zones feature compact building patterns, elevated pedestrian flows, and visually prominent cultural assets, which collectively necessitate higher nighttime illumination levels. Accordingly, they received the upper lighting priority scores in the spatial model. Discontinuous urban fabric, including low-density housing areas and peri-urban settlements, was assigned moderate lighting priority. Although these areas experience periodic nighttime use, their functional dependence on central activity areas justifies a more selective and efficiency-oriented illumination approach rather than continuous, high-intensity lighting.

By contrast, extensive agricultural lands, grazing areas, and natural vegetation zones—covering most of the district—were assigned low lighting priority. These environments generally demonstrate minimal nighttime activity, and excessive illumination could harm nocturnal wildlife, disrupt ecological functioning, and intensify sky-glow and light pollution. Therefore, lighting in these areas is limited to essential functions, such as rural intersections and critical infrastructure nodes, consistent with eco-sensitive lighting principles and CIE guidance on rural lighting contexts.

The results support the premise that lighting master plans in mixed rural–urban settings should prioritize activity-driven and heritage-sensitive zones and reinforce urban identity and safety while avoiding unnecessary illumination in ecologically sensitive landscapes. This land-cover driven approach aligns with contemporary research emphasizing data-informed, sustainable, and context-adaptive illumination frameworks for mid-sized cities with cultural heritage assets [

26,

27].

3.2. Evaluation of the Parks in Terms of Lighting Criteria

The evaluation of 76 public parks demonstrated substantial variation in accessibility, landscape value, and visual prominence, which together shaped their lighting priority scores (

Table 4).

Parks located within or adjacent to the historical core, and those integrated with civic and commercial corridors, achieved the highest cumulative scores due to their proximity to primary transportation routes, diverse programmatic and landscape elements, and high visual exposure within the urban fabric. These high-scoring parks exhibited rich spatial and cultural functions, including monuments, historical elements, designed vistas, and recreational amenities—and were therefore classified as first- and second-degree lighting priority zones, consistent with international urban park illumination principles emphasizing user safety, cultural enhancement, and nighttime legibility [

5,

6]

Conversely, parks situated in peripheral or fragmented settlement areas, especially those characterized by limited accessibility, reduced amenity diversity, and low visibility based on 3D line-of-sight modelling, received lower priority scores. These locations were placed in third- through fifth-degree priority categories, where lighting interventions should remain primarily functional—focused on pathway illumination, intersection lighting, and basic security without extensive architectural or ambient lighting. This differentiated approach prevents excessive light spill into semi-natural and low-use areas, aligning with ecological lighting principles and contemporary research cautioning against over-illumination in low-activity settings to mitigate habitat disruption and sky glow [

28,

29].

Landscape value scores, derived from ten design and amenity criteria, were consistent with the supervised classification and field verification process and demonstrated strong correlation with observed park quality and expected nighttime use intensity. Accessibility scores reflected proximity to primary transport corridors, while visibility assessments—supported by ASTER DEM and field-validated obstruction layers assured that visually dominant parks received appropriate prioritization.

The compiled scores (

Table 5) formed the basis for the final park lighting hierarchy map, reinforcing a performance-based, context-sensitive illumination strategy. These results underscore the importance of strategic rather than uniform lighting provision, ensuring that illumination investment aligns with public use patterns, perceived safety needs, and cultural-aesthetic value. As shown in parallel studies [

17,

30], parks with strong landscape identity and high visibility benefit most from enhanced nighttime lighting, supporting social interaction, public health, and urban character. The park prioritization framework adopted in this study, therefore, provides a replicable, evidence-based model for balancing user needs, cultural context, and environmental responsibility in mid-sized urban settings.

In situ lighting performance data were gathered for representative parks (

Table 6), including average illuminance, pole characteristics, uniformity ratios, glare assessment, and maintenance status, consistent with CIE 150:2017 and ISO 8995-1:2021 [

31] standards.

This table presents the field audit results for representative parks within the Central District of Niğde. The audit evaluates existing lighting conditions based on fixture type, average measured illumination levels (lux), pole height and spacing, lighting uniformity ratio (min/avg), glare observations, and maintenance status. Measurements followed CIE 150:2017 and ISO 8995-1:2021 protocols, with lux readings obtained at 1 m height across ten sampling points per park. The results highlight substantial variability in illumination performance and identify common issues, including insufficient uniformity, aging fixtures, and glare near pedestrian paths. Recommended interventions prioritize warm-white LED retrofits (≤3000K), improved uniformity through optimized pole spacing, and the addition of bollard/path lighting in visually sensitive zones. These findings provide empirical grounding for lighting prioritization and ensure that planning decisions reflect real-world performance conditions within Niğde’s park network. A comprehensive park lighting performance audit was conducted as part of this study, including in situ measurements, pole spacing documentation, fixture condition assessment, and uniformity analysis. The full dataset, including raw measurement values, methodological details, and park-specific performance tables, is provided as

Table S2. This dataset includes three sheets: (i) raw illumination readings, (ii) performance indicators and lighting improvement recommendations, and (iii) international standards [

5,

6] used as benchmarking criteria.

3.3. Protected Areas and Structures

The spatial assessment of protected heritage areas and registered historical buildings revealed notable deficiencies in architectural lighting across Niğde’s historic core and its peripheral cultural assets (

Table 7).

Field verification and Sentinel-2–assisted mapping confirmed that many culturally significant structures—including mosques, churches, tombs, fountains, and traditional civic buildings—remain unlit or rely solely on minimal security illumination. The lack of fade-oriented lighting not only limits nighttime visibility and visual continuity within the urban landscape, but also constrains opportunities for cultural expression, heritage interpretation, and nighttime tourism development.

Heritage elements were evaluated through three dimensions—architectural integrity, accessibility, and visibility, each contributing to prioritization scores within the GIS-based decision system. Structures with high architectural authenticity and strong façade preservation, located in physically and visually permeable settings such as primary squares, major approach corridors, and elevated viewpoints, received first- and second-degree lighting priority. These sites primarily cluster within the historic center and along key cultural routes. Consistent with international heritage illumination principles [

5,

6,

19], these locations are identified as requiring adaptive, low-glare, warm-tone architectural lighting solutions designed to emphasize material texture, relief, and spatial rhythm while preventing over-illumination and glare spill into residential zones.

Conversely, heritage structures with diminished architectural integrity, limited public access, or constrained visibility due to narrow streets or topographic obstruction were assigned lower priority scores. For these sites, functional, security-focused illumination is recommended until restoration, façade improvement, or urban façade corridors justify aesthetic lighting integration. This differentiated lighting strategy aligns with contemporary guidance emphasizing material conservation, ecological sensitivity, and minimizing light trespass—particularly in historically dense environments and in proximity to religious monuments and protected natural features. Beyond architectural considerations, the findings underscore the socio-economic and cultural potential associated with heritage-based nighttime visual enhancement.

Prior studies show that sensitive monument lighting supports evening tourism, reinforces civic identity, and increases resident perception of safety and pride [

32,

33]. Applied to Niğde, enhanced heritage illumination would strengthen nighttime spatial legibility and create a coherent visual narrative linking key monuments and public spaces. The results therefore demonstrate that illumination planning is not solely a technical infrastructure exercise, but a strategic cultural and economic development tool capable of reinforcing historical continuity, supporting sustainable tourism, and improving urban life quality after dark.

3.4. Population-Based Lighting Prioritization

Population density emerged as one of the most influential determinants of lighting demand across Niğde’s Central District (

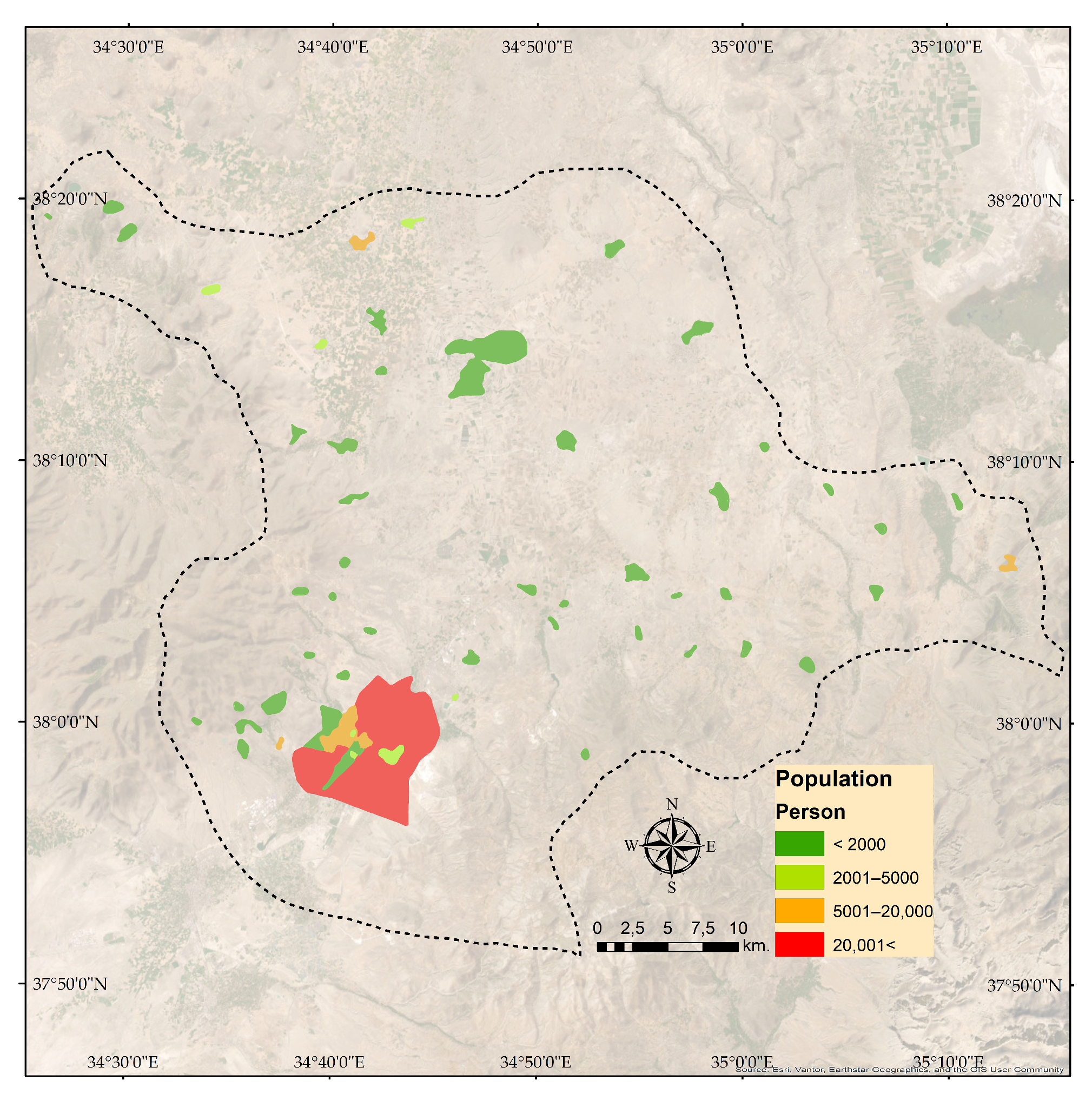

Figure 2).

The spatial assessment revealed a marked urban–rural gradient, with the compact urban core exhibiting significantly higher nighttime population presence and activity compared to peripheral settlements (

Figure 3). Densely populated neighborhoods, particularly those located within and immediately surrounding the historical and administrative center, were assigned higher lighting priority due to their continuous pedestrian movement, elevated security expectations, and frequent use of public squares, streets, and commercial corridors after sunset.

Population-based scores were derived using recent demographic data from the Turkish Statistical Institute. Settlements were categorized according to national administrative classifications, which differentiate villages, towns, and urban districts based on population thresholds and service functions. In accordance with this framework, the model applied the following scoring scheme:

Urban areas > 20,000 residents: Score 5 (very high lighting demand);

Intermediate settlements (2000–20,000 residents): Score 3;

Rural areas < 2000 residents: Score 1 (minimal lighting requirement).

This hierarchical structure reflects the complexity of lighting needs in dense urban environments, where multiple functions intersect, including pedestrian circulation, commercial activity, transit operations, and social gathering. In contrast, rural settlements exhibit limited nighttime activity and thus require targeted, essential illumination along key circulation routes or central gathering points rather than uniform coverage.

Spatial results indicated that neighborhoods such as Efendibey, Aşağı Kayabaşı, and Dere yielded the highest lighting demand scores, aligning with observed residential density and activity intensity. Conversely, peripheral villages and dispersed rural residences were assigned to lower priority levels, although the model acknowledges the role of minimum functional lighting in promoting safety, wayfinding, and perceived security even in sparsely populated areas.

While this study incorporated the most current population data available, it does not yet account for dynamic urban mobility patterns, seasonal population shifts, or age-structured nighttime behavior—factors increasingly emphasized in contemporary urban illumination studies [

6,

33].

Niğde’s ongoing trend of outward youth migration may also influence future illumination needs. Future research incorporating temporal population analytics, mobility tracking, and demographic segmentation could refine prioritization for age-sensitive spaces such as university areas, youth zones, senior-frequented environments, and tourism clusters. Overall, integrating demographic structure into the lighting master plan ensures that investment decisions align with actual spatial demand rather than uniform illumination approaches. This supports energy-efficient planning, promotes equitable access to safe nighttime environments, and strengthens the city’s public-space vitality after dark.

3.5. Temporal and Demographic Insights

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal and demographic patterns that influence nighttime urban lighting demand in Niğde Central District between 2012 and 2024. The population trend shows a gradual but steady increase from approximately 200,000 to nearly 240,000 residents, indicating consistent urban growth and densification within the city core.

This demographic expansion is accompanied by a structural predominance of the working-age group (25–44 years, 28.67%) and a relatively large share of children and youth (0–24 years, 40%), both of which contribute significantly to the spatial and temporal dynamics of nighttime activity.

The presence of a young and socially active population implies a sustained level of evening mobility and outdoor use, especially in mixed residential–commercial districts. The heatmap of relative pedestrian density (19:00–23:00) confirms this pattern, revealing that the highest concentrations of nighttime movement occur along the Efendibey–Dere corridor, forming a continuous axis of activity that extends toward the historical and administrative center. Moderate densities are also observed in peripheral residential zones, suggesting a more distributed pattern of nocturnal use than previously expected.

These combined findings highlight that lighting demand in Niğde is not uniform but strongly dependent on both temporal rhythms and demographic composition. Therefore, illumination strategies should be planned in accordance with the intensity and timing of human presence, prioritizing areas with peak evening activity for functional and safety-oriented lighting, while adopting adaptive or energy-efficient systems in less active zones. Integrating such temporal and demographic insights into GIS-based planning provides a more realistic and responsive foundation for sustainable urban lighting design.

3.6. Lighting Master Plan of Niğde Central District

The composite lighting priority model identified a clear, data-driven spatial hierarchy of illumination needs within Niğde’s Central District based on the integration of five weighted spatial layers: land cover, parks, protected heritage, population density, and government institutions. Rather than presenting graphical overlays, this study reports results through structured tabular outputs to ensure analytical transparency, reproducibility, and verifiable traceability between spatial criteria and planning outcomes (

Table 8).

Table S3 summarizes the aggregated scores for each urban area and their corresponding priority class, providing a direct numerical link between spatial inputs and lighting decisions. The highest-priority zones (first-degree) are concentrated in and around the historic urban core, mixed-use corridors, and primary civic squares, where high population density, cultural heritage, and essential public facilities co-occur. These areas exhibit the strongest evening pedestrian activity and cultural visibility needs; therefore, lighting should reinforce public safety, enhance architectural legibility, and support nighttime social life and tourism potential. Intermediate-priority zones (second- to fourth degree) correspond to residential neighborhoods, secondary commercial areas, and isolated public service structures.

These locations require functional lighting to ensure safe circulation and prevent crime, yet without excessive luminance levels that could generate unnecessary energy use or cause light pollution. Recommended strategies focus on balanced illumination, human-scaled fixture heights, and glare-controlled luminaires. Lowest-priority zones (fifth degree) primarily include agricultural landscapes, open vegetation areas, and low-density settlements. In such areas, light interventions should remain minimal, ecologically sensitive, and limited to essential transport links and key public safety points. This approach supports dark-sky objectives and reduces ecological disruption in peri-urban environments, particularly for nocturnal species, whose behavior and habitat may be negatively affected by excessive night lighting. Furthermore, the study acknowledges that nighttime perception and lighting performance differ from daytime visibility assumptions. Where applicable, nighttime field observations and expert reviews were incorporated to verify lighting needs empirically, rather than inferring illumination strategy solely from daytime spatial data. Overall, this structured and measurable output format ensures that urban lighting decisions are grounded in objective spatial evidence, aligns with contemporary sustainable lighting literature [

3,

4], and supports municipal implementation by providing actionable, audit-ready planning tables rather than subjective or visually dependent interpretations. Field nighttime observations confirmed the model output, particularly in the historic core, where insufficient façade lighting and uneven pedestrian illumination were documented, supporting the priority ranking of these zones.

3.7. Overlay of Maps and Lighting Zones

The final lighting priority surface was produced by integrating all five standardized spatial layers through a weighted-overlay analysis in ArcGIS. Each factor—land cover, parks, protected heritage structures, population density, and government institutions—was assigned an equal weight (20%) following a neutrality-based multi-criteria decision strategy. This approach prevented subjective prioritization and ensured that all spatial drivers contributed equally to the final model. To test the robustness of equal weighting, additional sensitivity scenarios were evaluated (heritage-dominant and population-dominant weight distributions), all confirming similar spatial clustering patterns in core urban areas.

The composite output categorized the district into five lighting priority classes. Very high-priority zones (first degree) were concentrated in the historic urban core, where dense pedestrian activity, cultural monuments, and civic buildings intersect. These areas represent locations where architectural, cultural, and safety objectives converge, making them focal points for expressive yet energy-aware nighttime lighting. High- and medium-priority zones (second and third degree) corresponded largely to mixed-use residential corridors and local parks, where lighting supports pedestrian comfort, visual orientation, and neighborhood safety, but with less symbolic emphasis. Low-priority zones (fourth and fifth degree) were primarily agricultural lands, forested slopes, and peripheral villages, where illumination requirements are minimal and guided by ecological sensitivity and essential mobility needs.

By visualizing cumulative urban values, the overlay model enables municipal planners to transition from intuition-based lighting decisions toward an evidence-driven framework. This results in a spatial hierarchy that aligns illumination demand with cultural identity, safety, and sustainability imperatives. The overlay findings reinforce the study’s premise: rather than uniform illumination, context-adaptive lighting provides a more efficient and culturally responsive strategy for medium-sized heritage cities. This structured prioritization supports phased implementation, budget optimization, and targeted policy design, ensuring that light investments yield maximum spatial and cultural impact.

3.8. Scenario-Based Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed GIS-based lighting model and explore the implications of alternative planning priorities, a scenario-based sensitivity analysis was conducted. Three weighting configurations were designed to emphasize different urban values: heritage conservation (Scenario A), population dynamics (Scenario B), and institutional importance (Scenario C). These alternative scenarios were applied to the same set of reclassified raster layers, maintaining consistent spatial resolution and normalization parameters. The resulting lighting priority maps are presented in

Figure 4A–C.

In the Heritage-focused model (A), the highest lighting priority (20–25 points) is concentrated in the historic core of Niğde, including the Kale, Eskisaray, and Ahipaşa neighborhoods. These zones contain dense clusters of registered heritage structures and traditional street layouts, which play a vital role in defining the city’s cultural identity at night. The moderate-priority areas (10–20 points) radiate outward from the historic center, indicating transitional zones where urban conservation and everyday functionality intersect.

The Population-focused scenario (B), on the other hand, shifts high-priority lighting zones toward Efendibey, Dere, and İnönü neighborhoods—areas characterized by higher residential density and active nighttime use. This outcome highlights how integrating demographic and social parameters can reshape the spatial hierarchy of lighting priorities, aligning illumination strategies with accessibility, safety, and community activity patterns.

Finally, the Institutional-focused model (C) identifies concentrated lighting needs around the governmental and administrative districts, particularly along major transportation corridors and civic service areas. The distribution pattern is more dispersed compared to the previous two models, reflecting the presence of multiple local centers of functional importance. This scenario underscores the symbolic and practical significance of lighting around public institutions for reinforcing civic presence and orientation within the urban fabric. Across all three scenarios, the central part of Niğde consistently emerges as the area of highest lighting priority, though the extent and intensity of high-value zones vary depending on the applied weighting system. This variation confirms the model’s sensitivity to socio-spatial parameters and validates its ability to reflect diverse urban planning perspectives. The comparative visualization in

Figure 4 also demonstrates how GIS-based multi-criteria analysis can support flexible decision-making in lighting master planning, enabling planners to balance heritage preservation, social activity, and institutional functionality within a coherent spatial framework.

3.9. Discussion

The findings of this research confirm that lighting master plans can transcend purely technical or aesthetic approaches when integrated with spatial heritage values, demographic dynamics, and high-resolution environmental data. By combining GIS-based spatial modeling with cultural heritage layers, this study introduces an innovative, data-driven framework that aligns illumination planning with both the functional structure and the historical identity of the city. The integration of Sentinel-2 imagery and demographic time-series further enhanced the analytical robustness of the model, allowing lighting priorities to be interpreted within their socio-spatial context. However, the results also reveal several research gaps and methodological challenges that open pathways for future enhancement.

3.9.1. Research Gaps

Although numerous studies have addressed urban lighting from environmental or perception-based perspectives, few have conceptualized it as an integrated spatial planning issue.

Prior research often overlooked the interconnection between heritage preservation, population dynamics, and lighting demand. The present study partially bridges this gap by introducing a multi-layered GIS framework that correlates lighting needs with tangible (e.g., heritage structures, government institutions) and intangible (e.g., cultural visibility, urban identity) urban values.

Nonetheless, additional dimensions such as citizens’ perception, nighttime comfort, and behavioral patterns remain underrepresented. Future studies should explore how lighting influences social equity, sense of place, and safety perception at night. Moreover, cross-city comparative analyses involving diverse morphological and cultural typologies (e.g., Konya, Kayseri, Antalya) could help assess how this framework performs under different heritage and settlement structures.

3.9.2. Contextual and Methodological Reflections

The case of Niğde illustrates how lighting can act as a medium that binds cultural memory with spatial form. The GIS-based results—particularly the sensitivity analysis of weighting scenarios—show that lighting demand consistently peaks within the historic core, where heritage structures, public institutions, and dense population clusters overlap. This outcome aligns with the best international practices, emphasizing that illumination strategies should respond to cultural value gradients rather than administrative zones. However, the analysis also reveals an implementation gap: peripheral heritage sites with symbolic and tourism potential remain under-illuminated.

The initial decision to apply equal weighting across the five spatial factors ensured transparency and replicability. Yet, the sensitivity test demonstrated that small variations in factor weights could significantly shift lighting priority zones, underscoring the importance of expert-driven weighting systems. Incorporating multi-criteria decision-making tools—such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), fuzzy logic, or participatory ranking—could make the model more adaptive and locally responsive.

3.9.3. Limitations of the Present Research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the model remains primarily static, relying on annual population and spatial data. Although the temporal and demographic extension (

Figure 3) provided insight into population age structure and growth patterns, it did not incorporate hourly or seasonal mobility variations, which can strongly influence nighttime lighting demand. Integrating dynamic datasets—such as pedestrian mobility from mobile sensors or tourism seasonality—would enable more adaptive illumination strategies. Second, while the Sentinel-based visibility analysis improved accuracy, it still assumes stable urban morphology. Factors such as vegetation growth or ongoing construction were not dynamically accounted for and may affect long-term visibility patterns.

Third, the ecological dimension of lighting, especially its impact on nocturnal species, was not quantitatively addressed, representing an important direction for interdisciplinary collaboration between lighting design, ecology, and urban sustainability. Finally, the model assumes homogeneous economic feasibility among lighting interventions. Incorporating energy consumption, operational costs, and carbon metrics could strengthen the sustainability dimension of future models.

3.9.4. Ecological and Light-Pollution Considerations

Although the primary focus of this study was to prioritize urban lighting needs, ecological integrity and light-pollution concerns were also considered in the design logic. Artificial illumination can disrupt nocturnal wildlife behavior, interfere with avian migration, and alter insect activity, particularly in peri-urban agricultural and semi-natural areas [

34]. To mitigate these risks, the model intentionally assigns the lowest lighting priority to natural and agricultural landscapes, aligning with sustainable illumination principles and recommendations from CIE 150:2017 and IES RP-8-18.

Field observations confirmed that several peripheral districts already experience minimal illumination, consistent with ecosystem-protective nighttime conditions. For high-priority heritage zones, the lighting strategy emphasizes warm color temperatures (<3000 K), controlled beam distribution, shielded luminaires, and reduced upward spill to support human–wildlife co-existence and minimize skyglow. This approach reflects current international discourse advocating biodiversity-sensitive lighting practices in culturally significant urban environments [

29]. Future research should incorporate quantitative sky-brightness measurements and biological monitoring to further assess ecological effects and refine mitigation strategies.

3.9.5. Future Directions and Improvement Opportunities

Future extensions of this research should aim to merge quantitative spatial modeling with qualitative social inquiry. Participatory mapping, focus groups, and perception-based surveys could complement GIS analyses by capturing users’ sense of safety, aesthetic comfort, and emotional connection to illuminated environments. These qualitative datasets could be spatially interpolated to validate or recalibrate model outputs.

Moreover, integrating smart lighting technologies—such as sensor-based adaptive systems or variable color temperature schemes—would allow lighting priorities to respond dynamically to real-time activity and environmental conditions. Expanding the analytical framework to include economic, environmental, and social sustainability indicators would transform the current model into a comprehensive decision-support tool for urban governance.

Lastly, extending the analysis to other Anatolian mid-sized cities with distinct historical and morphological patterns would test the scalability and cultural adaptability of the model, providing comparative insights into the relationship between lighting, identity, and sustainability.

3.9.6. Broader Implications

Beyond methodological contributions, this research repositions lighting as a strategic policy instrument that integrates energy efficiency, cultural storytelling, and spatial identity. By merging GIS-based analytics with heritage-sensitive planning, the study demonstrates that lighting can simultaneously serve aesthetic, functional, and symbolic purposes. The results underline that sustainable illumination design should focus as much on what to light as on how to light, guided by cultural meaning, visibility hierarchies, and contextual sensitivity.

This approach contributes to the emerging paradigm of “identity-driven lighting planning,” where illumination strengthens not only visibility and safety but also the experiential and narrative dimensions of the urban nightscape. Notably, integrating field observations and environmental screening strengthened the reliability of the spatial model. Observed glare, skyglow risk, and ecological sensitivity informed the refinement of lighting recommendations, consistent with dark-sky and eco-lighting principles. This hybrid approach balances cultural illumination with environmental stewardship.

3.9.7. Historical Lighting Systems

Field observations revealed that most historical structures in Niğde—such as mosques, churches, fountains, and segments of the ancient city walls—either lack exterior lighting entirely or are equipped with outdated systems designed solely for basic security. These conditions fail to showcase architectural features, reduce nighttime visibility, and diminish the symbolic presence of heritage assets within the urban landscape. Existing installations are often characterized by high-mounted floodlights, poorly positioned fixtures, or excessively bright sources that produce glare and distort architectural detail. Such configurations not only overlook the aesthetic character of the buildings but also contribute to light pollution and energy inefficiency. To address these deficiencies, the study proposes the following improvements:

Facade-sensitive lighting: Implementation of warm-toned, low-glare LED fixtures installed in accordance with architectural rhythms, materials, and surface textures.

Layered lighting strategies: Integration of uplighting, wall washing, and accent lighting to reveal architectural volume and detail.

Contextual placement: Minimizing light spill onto adjacent structures and the night sky by respecting sightlines, spatial relationships, and historical context.

Smart lighting controls: Incorporation of motion sensors, programmable timers, and dimming systems to balance visibility with energy efficiency.

In addition, collaboration with conservation experts and professional lighting designers is essential to ensure that all interventions align with restoration principles and enhance cultural storytelling. These strategies can transform heritage sites into nighttime landmarks, enriching the city’s visual identity and extending their use beyond daylight hours. Ultimately, the illumination of historical buildings should not be treated as an afterthought, but rather as a central element of urban design—one that fosters historical continuity, strengthens cultural expression, and contributes to safer, more vibrant, and contextually meaningful nightscapes.

3.9.8. Comparison to Previous Studies

Unlike many lighting studies that focus narrowly on technical specifications, environmental impacts, or urban aesthetics in isolation, this study presents a comprehensive and multi-layered approach to lighting master planning. By integrating five diverse urban components—land cover (CORINE), public parks, protected areas, and historical structures, population density, and government institutions—the model offers a broader, context-sensitive understanding of lighting needs in a mid-sized Anatolian city. Prior research often relied on single-criterion assessments, such as prioritizing security lighting or optimizing visual comfort, and typically lacked spatial integration. For instance, while studies such as Hansen et al. (2019) [

26] emphasized the principles of functional lighting design, they did not consider spatial overlaps between cultural heritage zones and population centers. Similarly, landscape-focused research frequently omitted demographic dynamics or the administrative significance of civic infrastructure.

One of this study’s key methodological innovations is the application of the CORINE land classification system—commonly used in land-use and environmental planning—within an urban lighting context.

Additionally, the inclusion of protected heritage zones and architectural scoring introduces a qualitative cultural dimension that is typically absent from conventional GIS-based lighting models. These additions expand the analytical scope from purely technical evaluations to cultural and symbolic considerations. The model’s use of equal weighting across all five factors further supports a balanced planning perspective, preventing the dominance of any single urban value system. While this weighting scheme can be refined in future iterations through stakeholder consultation or adaptive prioritization algorithms, the current approach prioritizes methodological transparency, simplicity, and replicability. Overall, the study contributes a scalable and adaptable GIS framework for urban lighting strategies—one that accounts not only for spatial form and functional demand, but also for identity, cultural expression, and usage intensity.