Research on Engineering Characteristics of Lignin–Cement-Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Lateritic Clay

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program Design

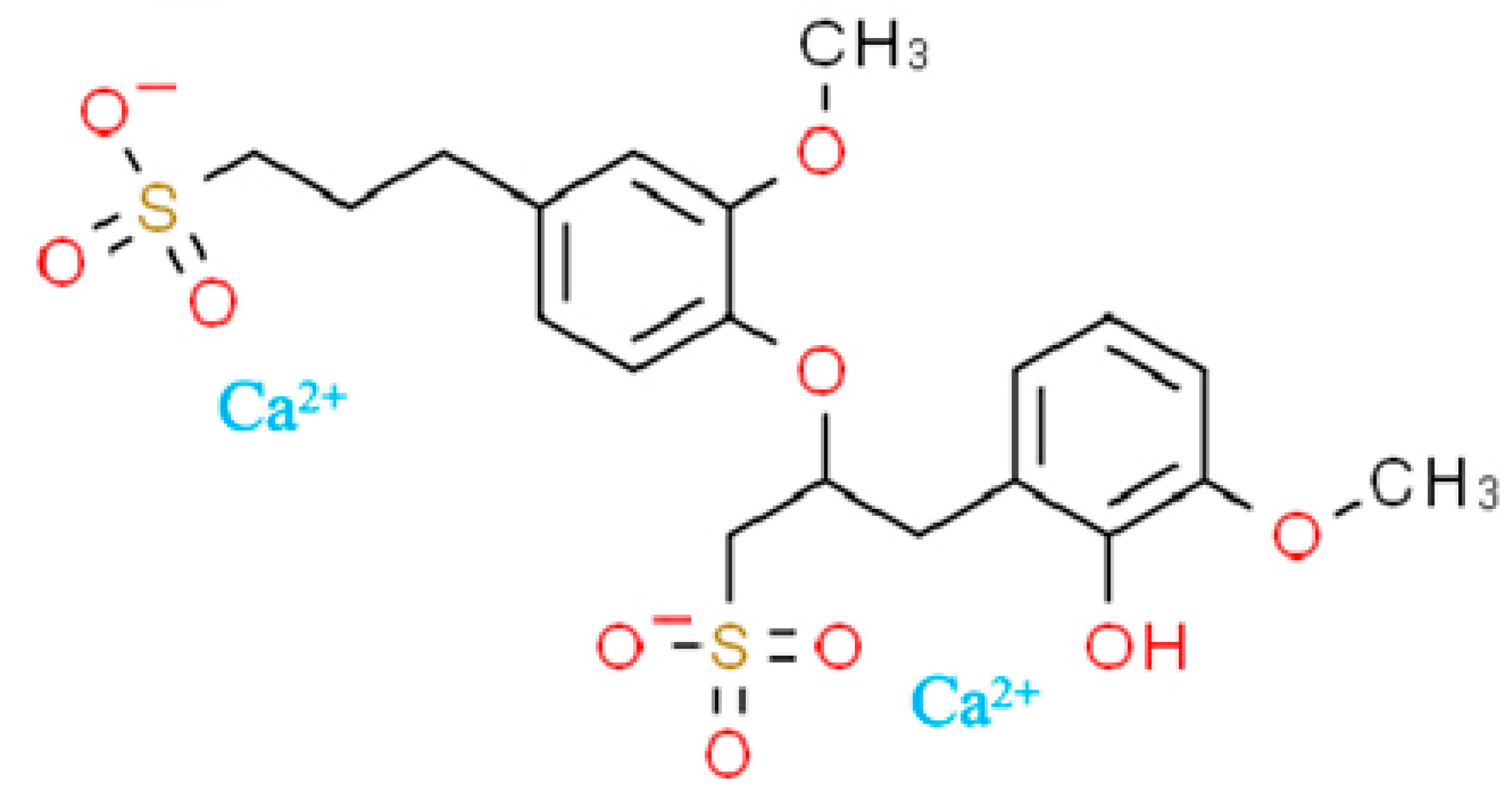

2.1. Materials and Their Characterization

2.2. Experimental Methodology

2.2.1. UCS Test

2.2.2. Permeability Test

2.2.3. TCLP Test

2.2.4. Microscopic Test

3. Results

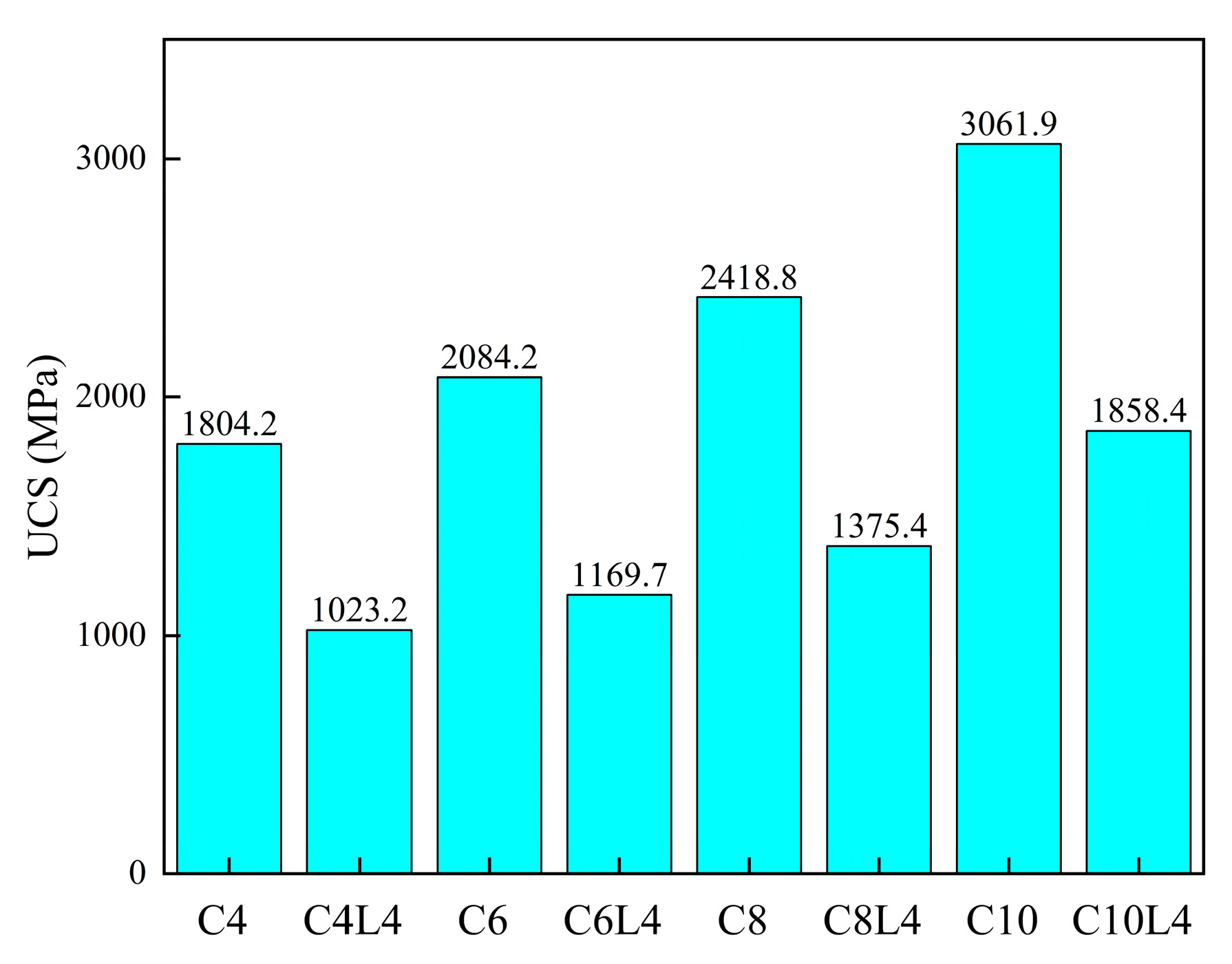

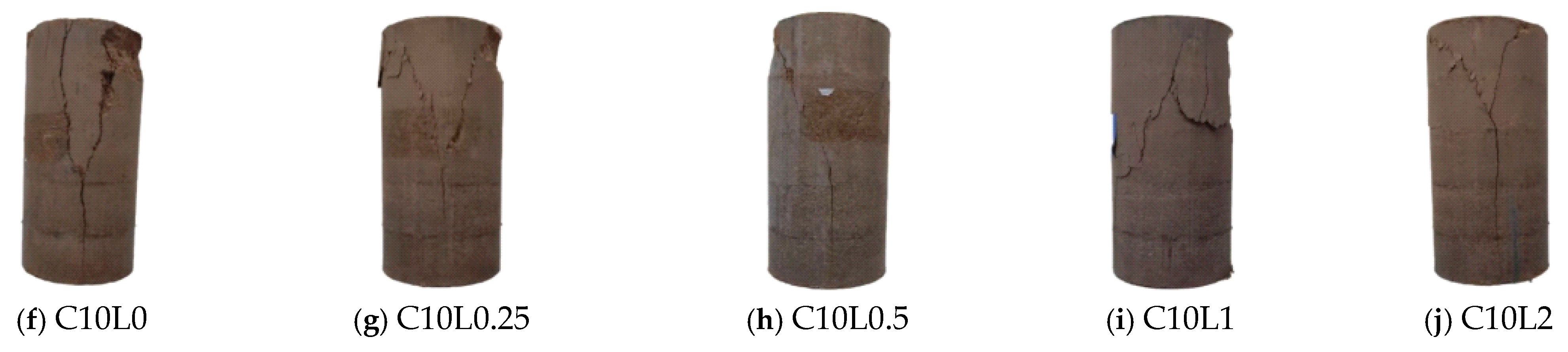

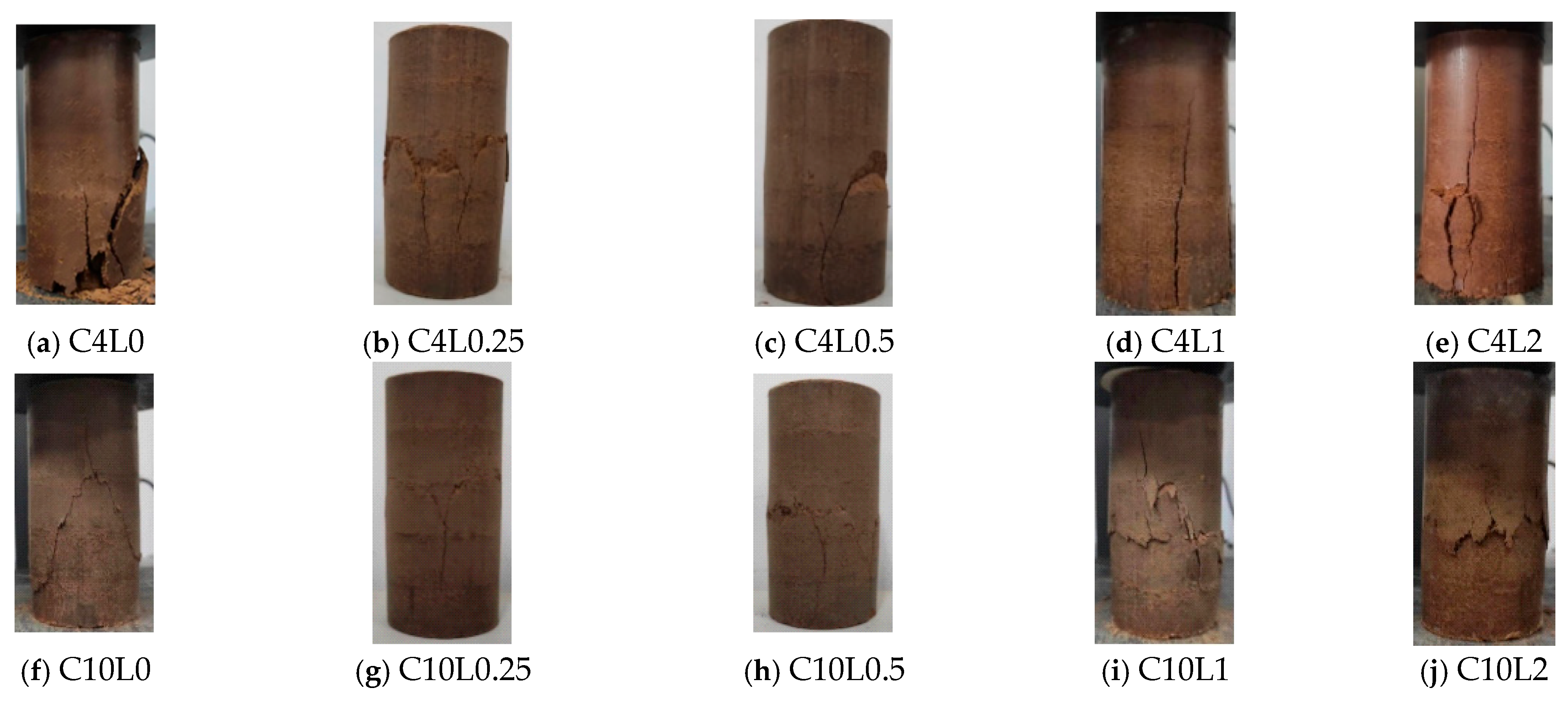

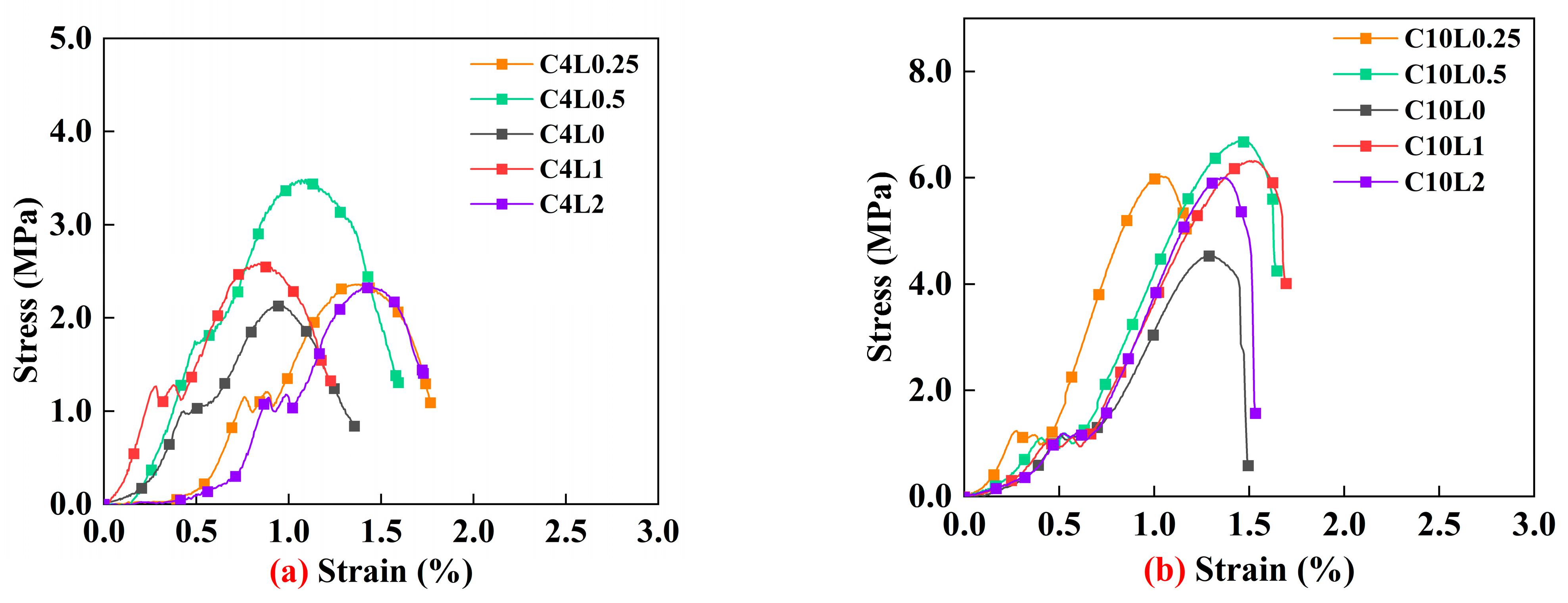

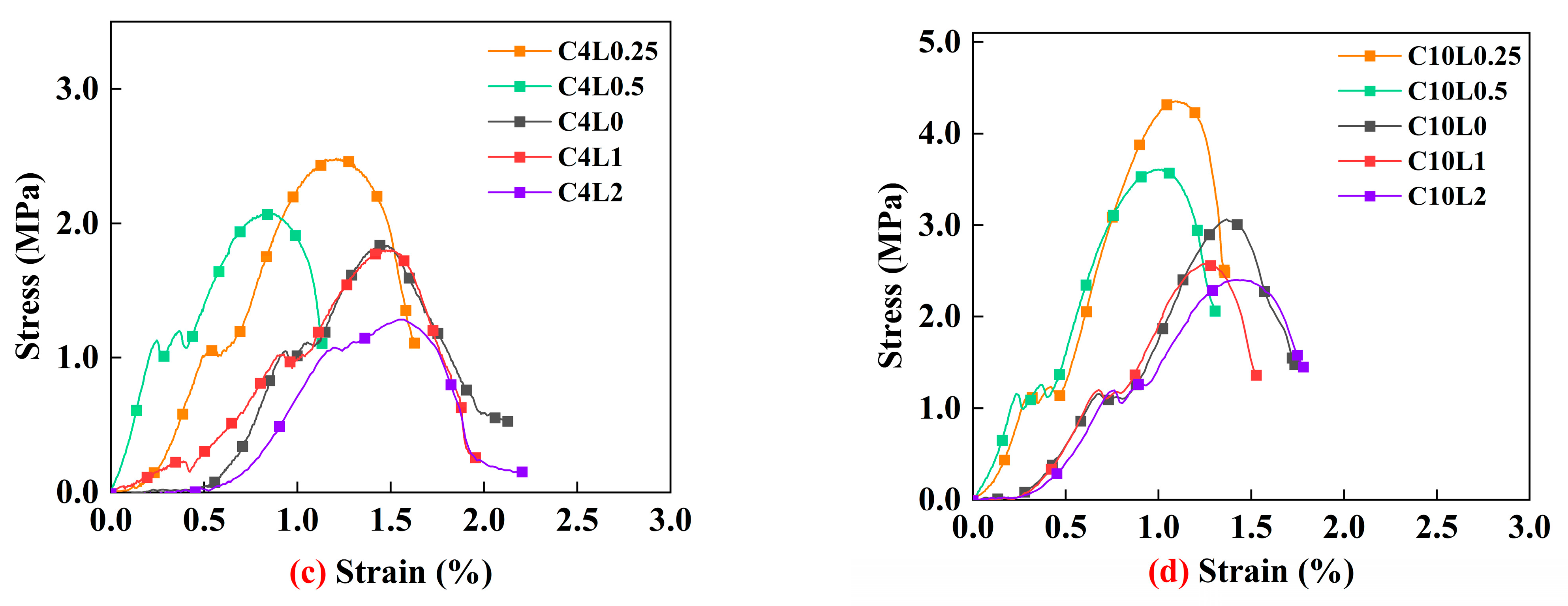

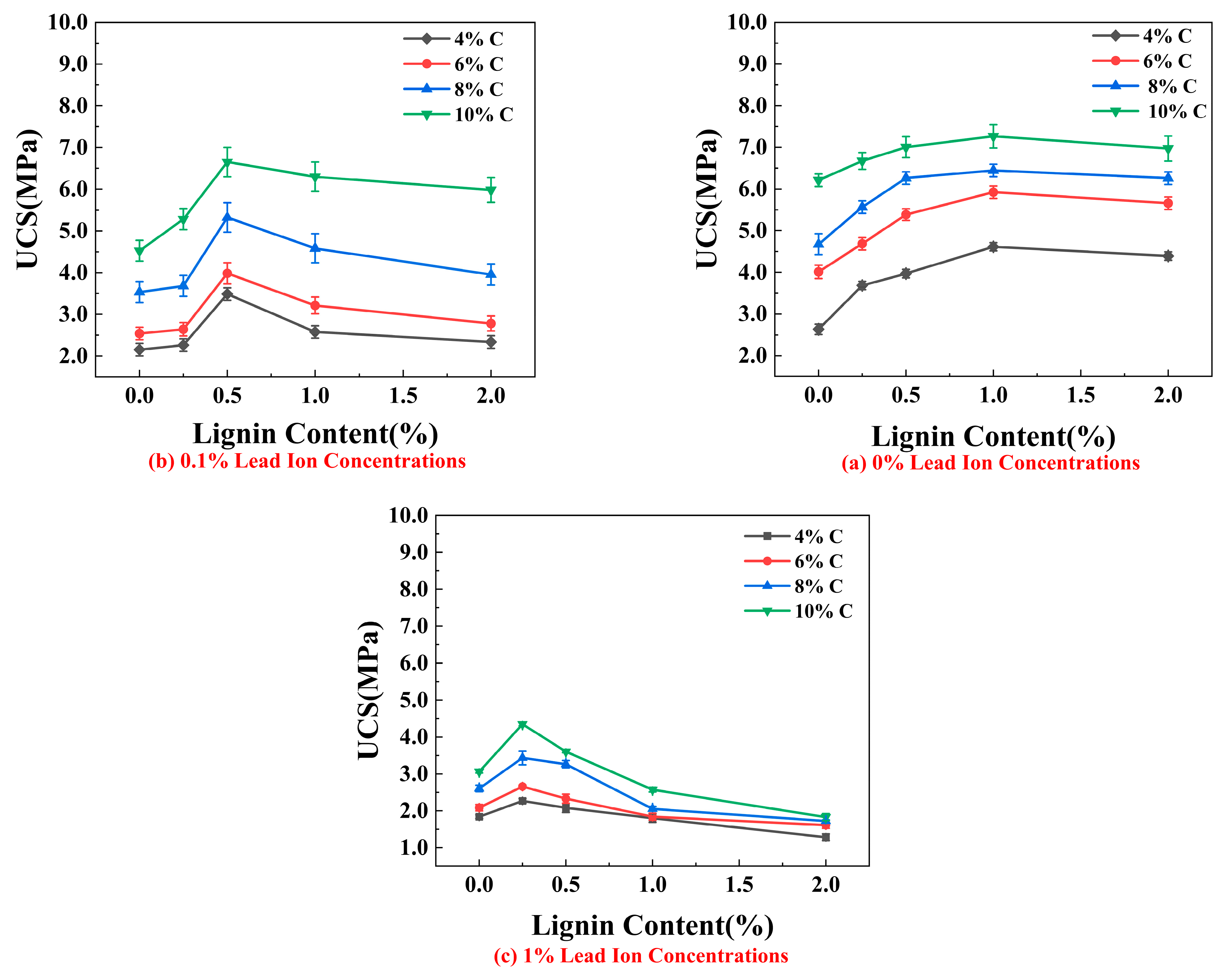

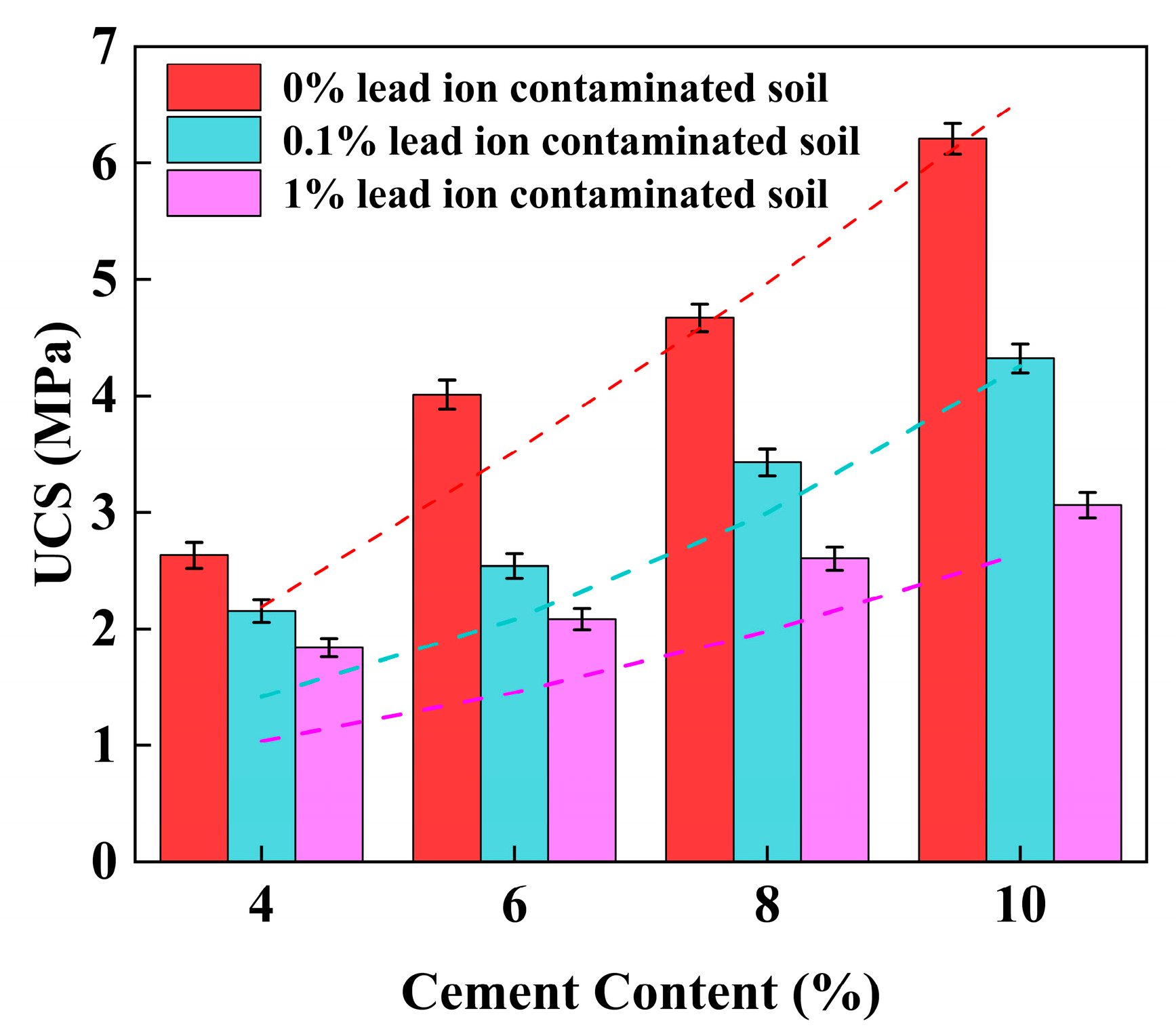

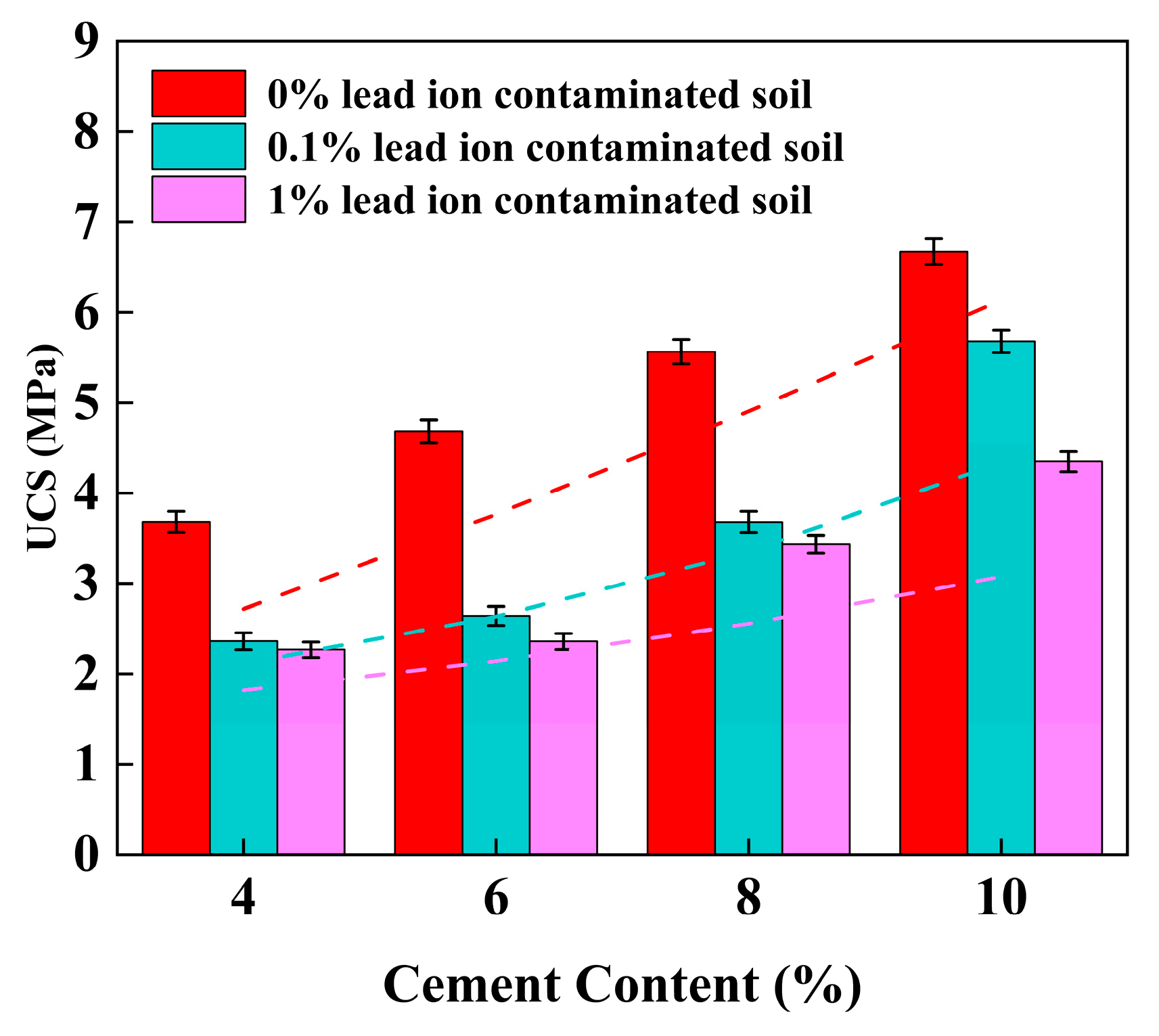

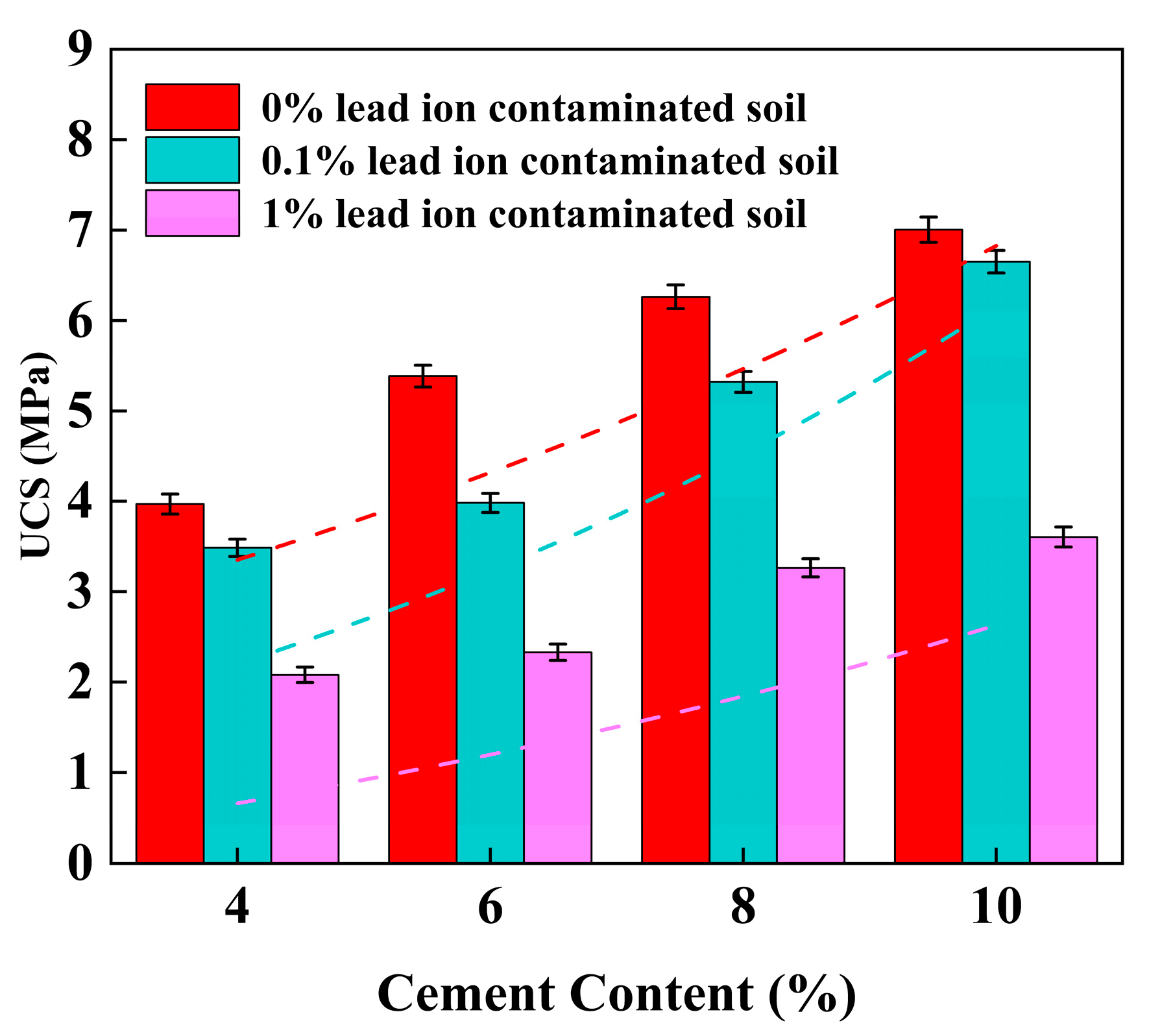

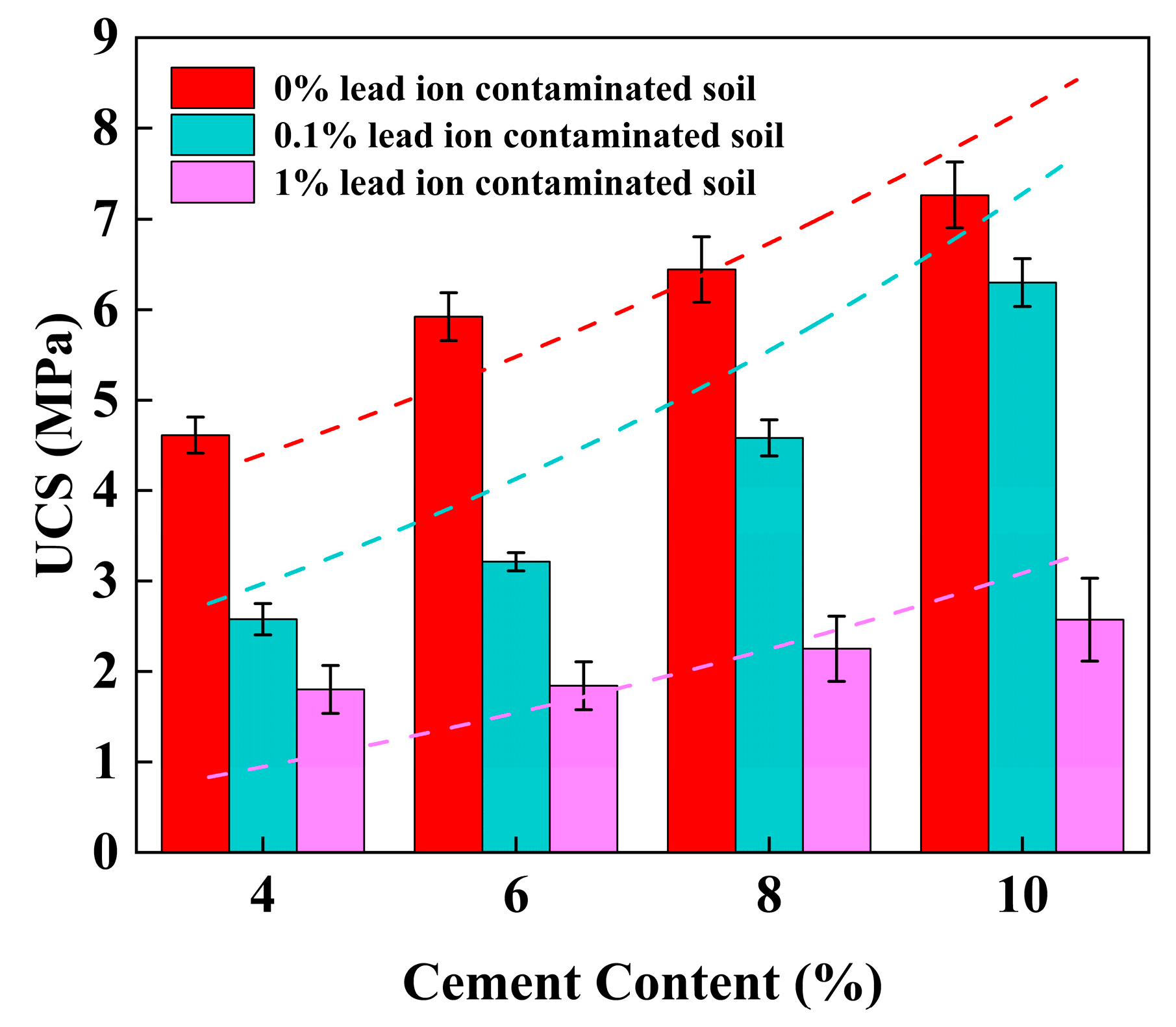

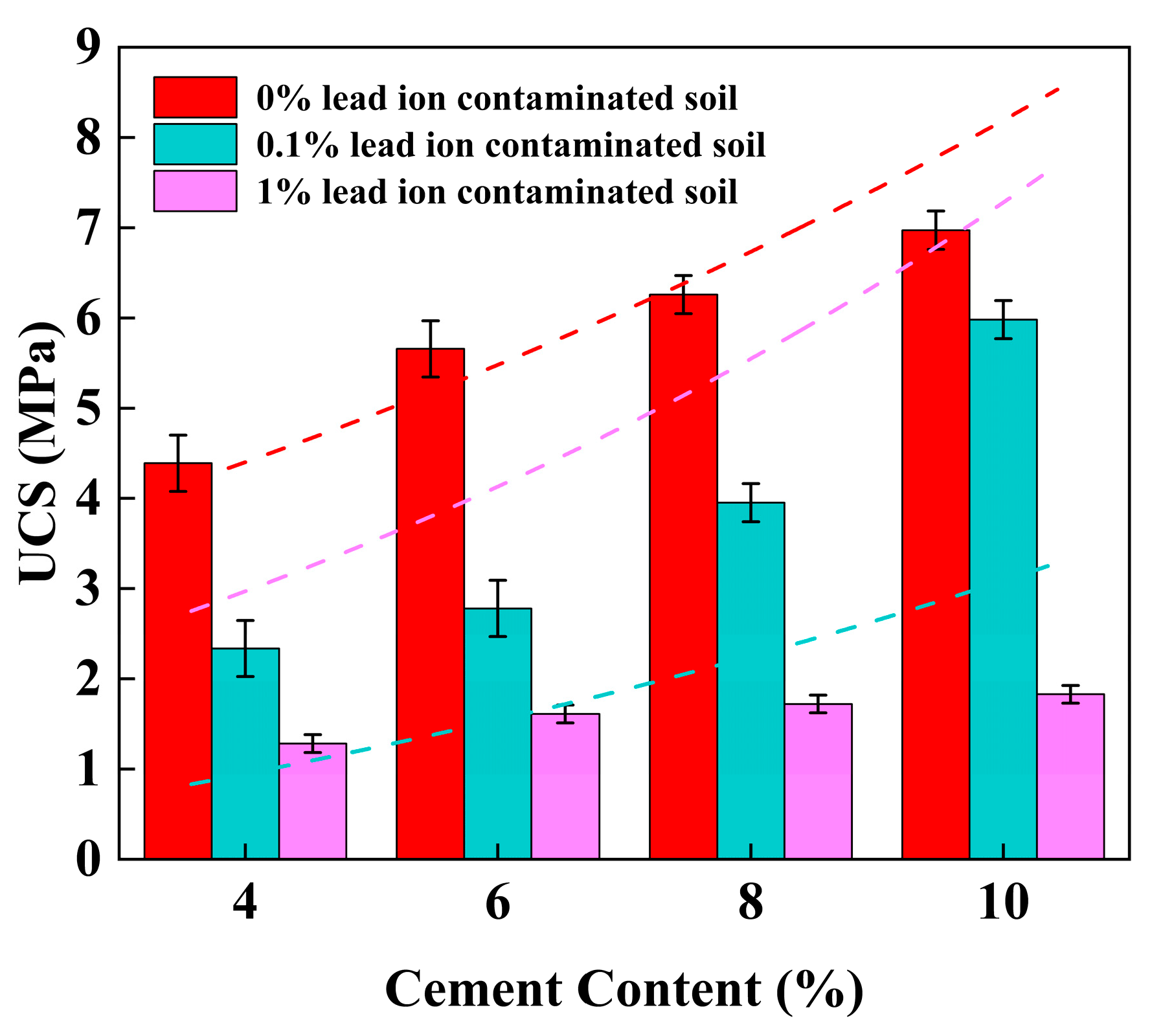

3.1. Unconfined Compressive Strength (UCS)

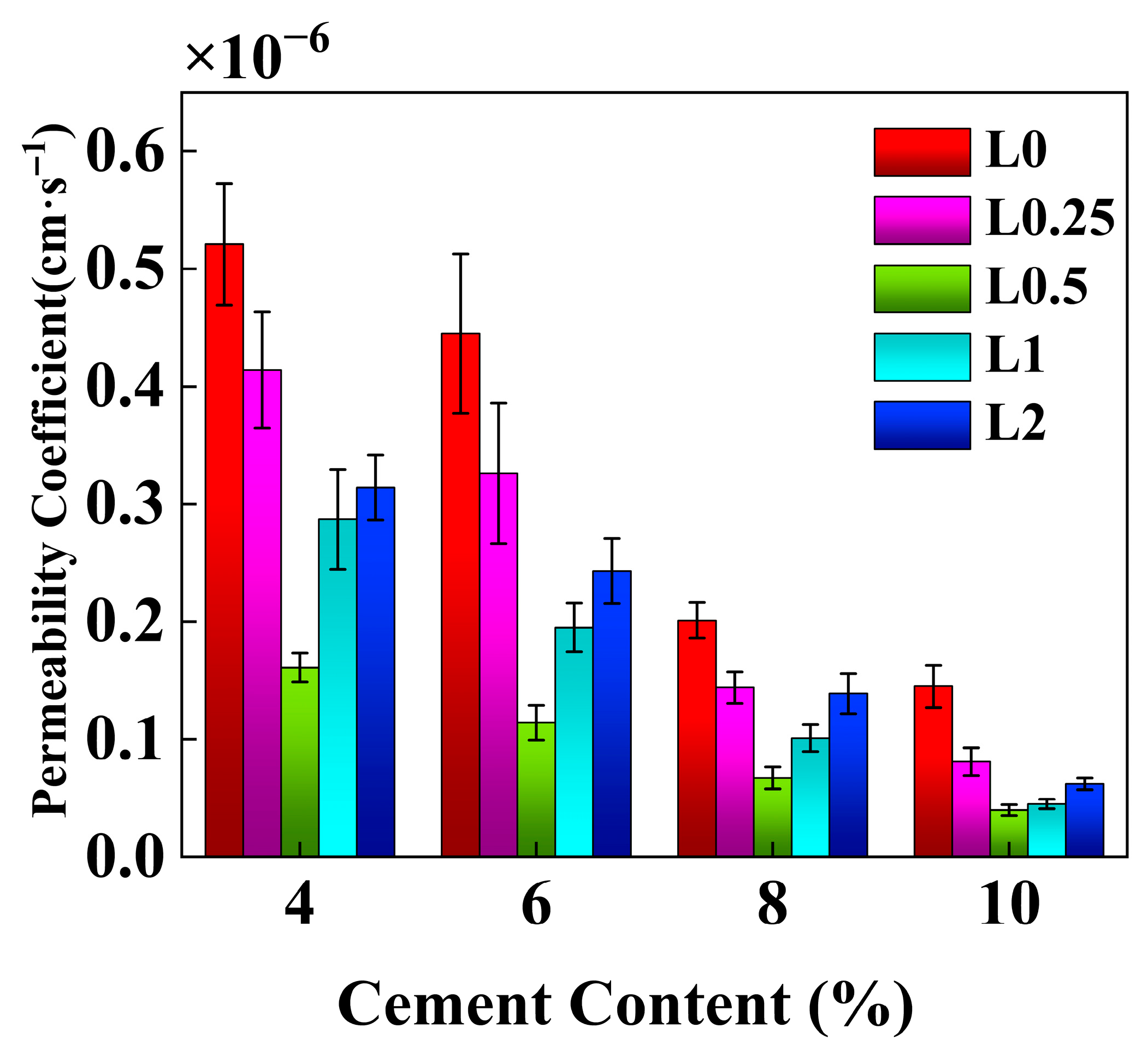

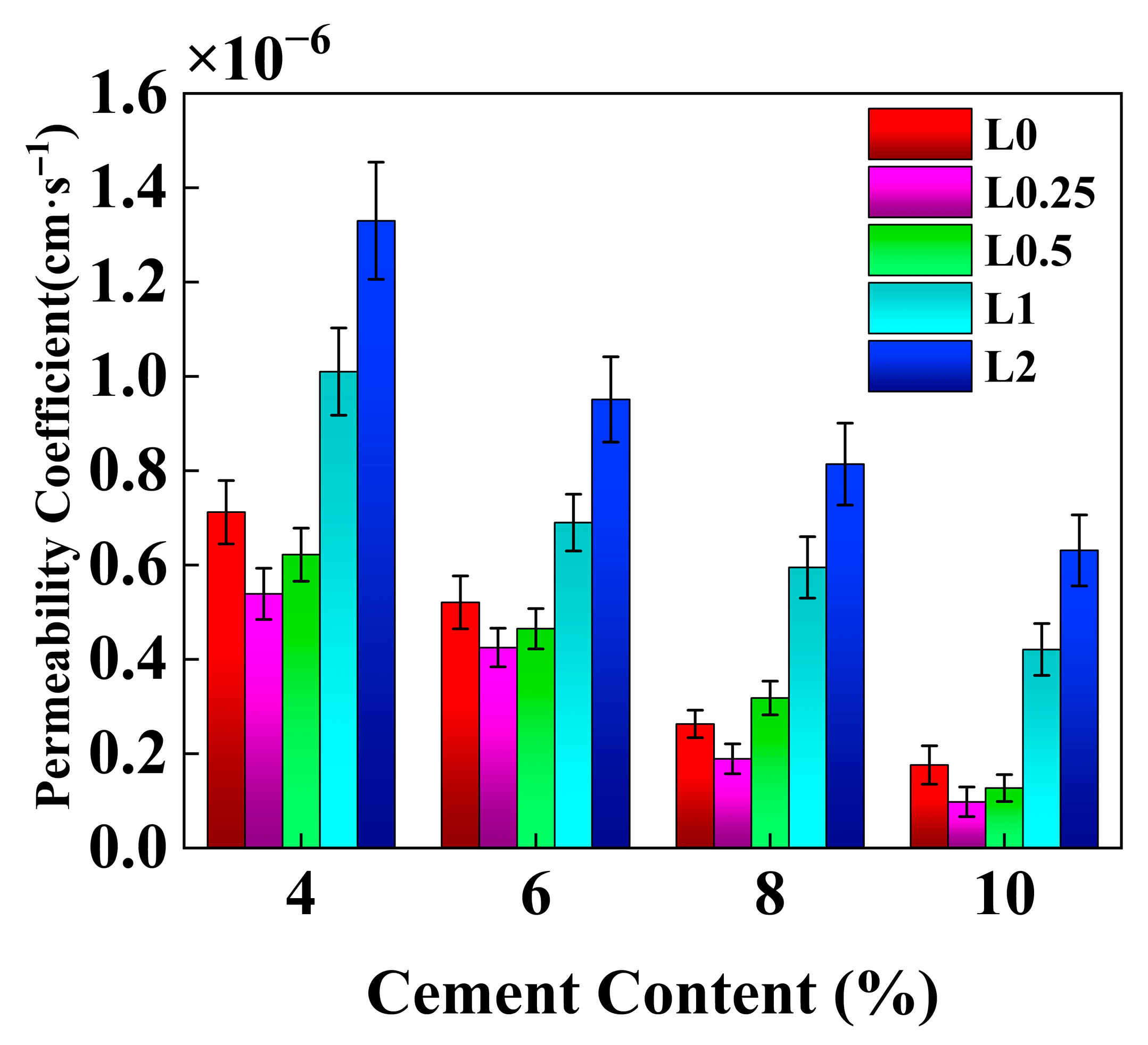

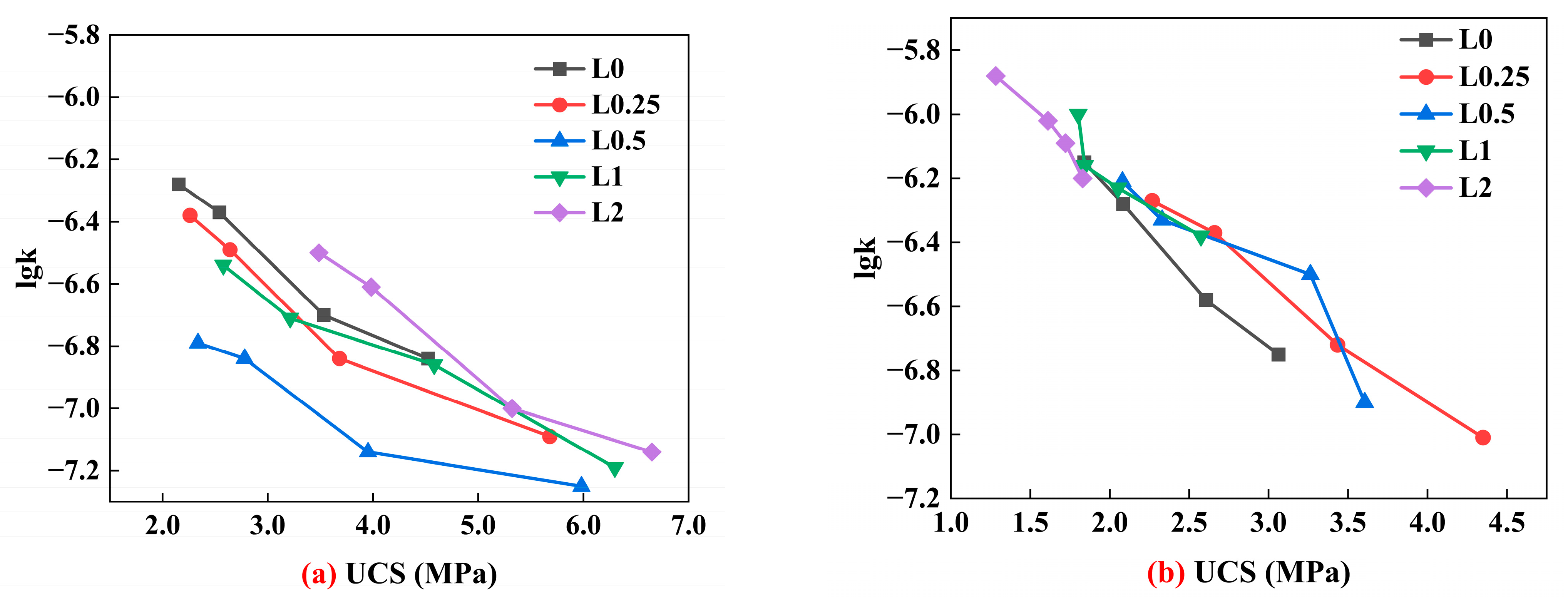

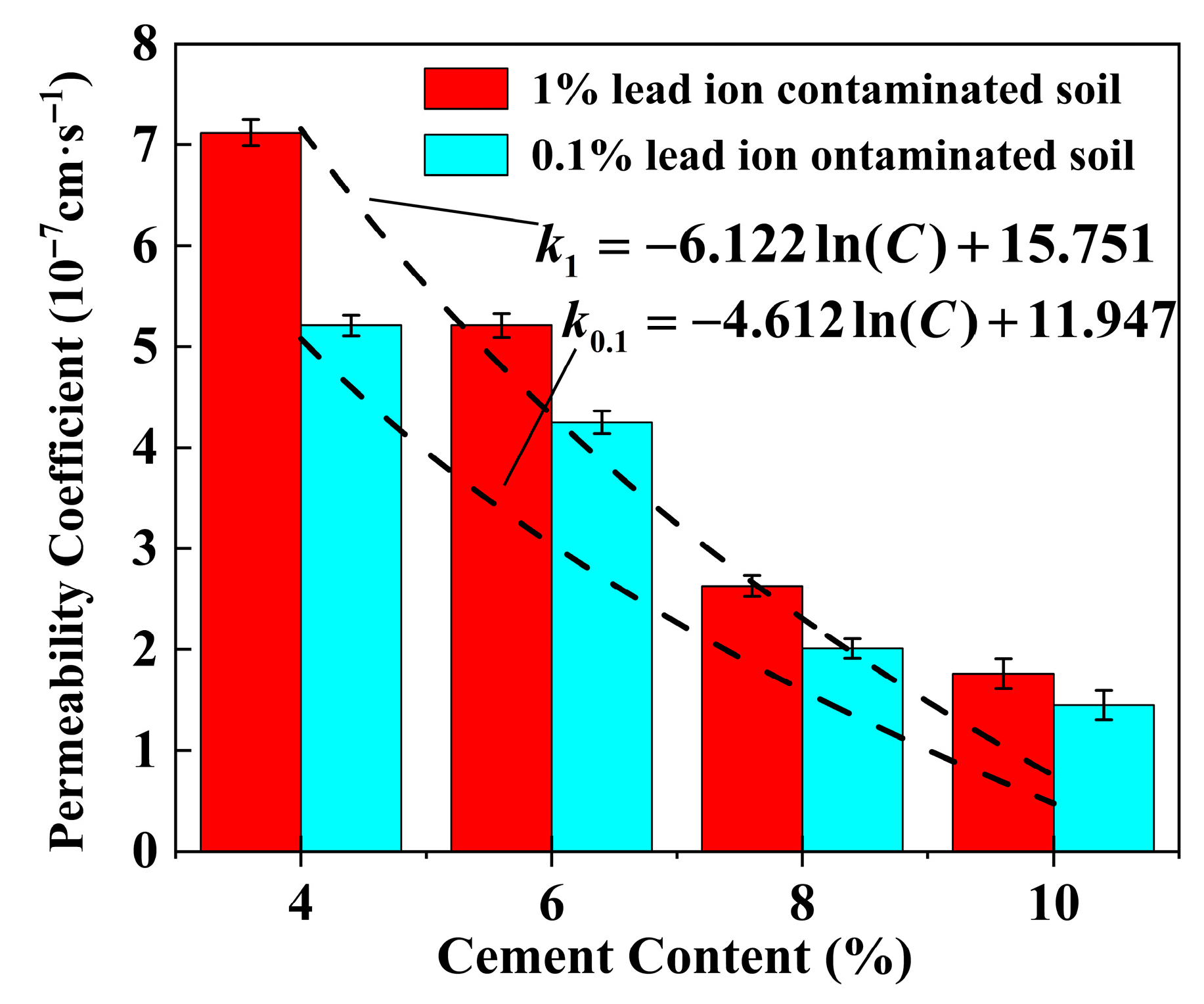

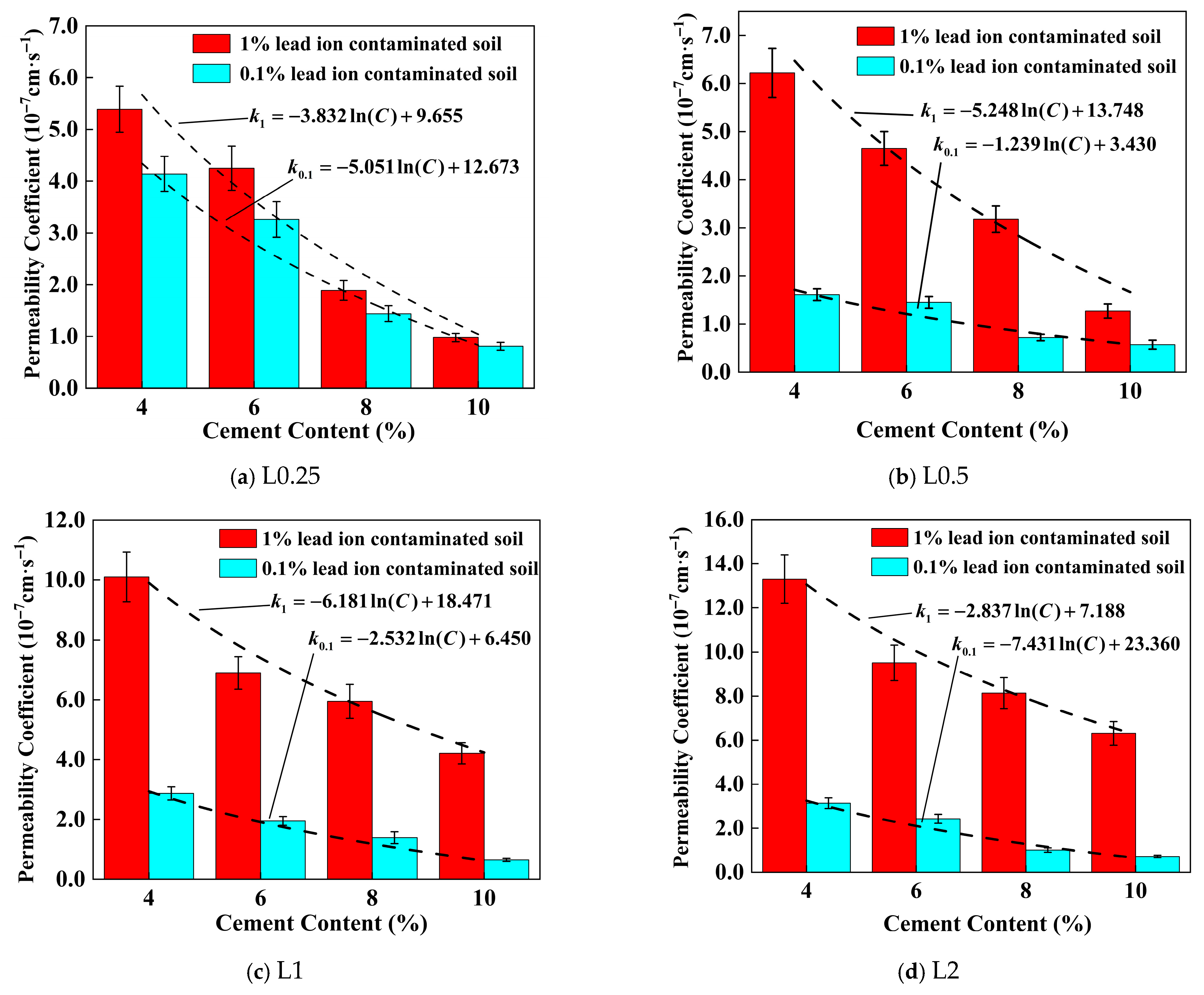

3.2. Permeability Characteristics

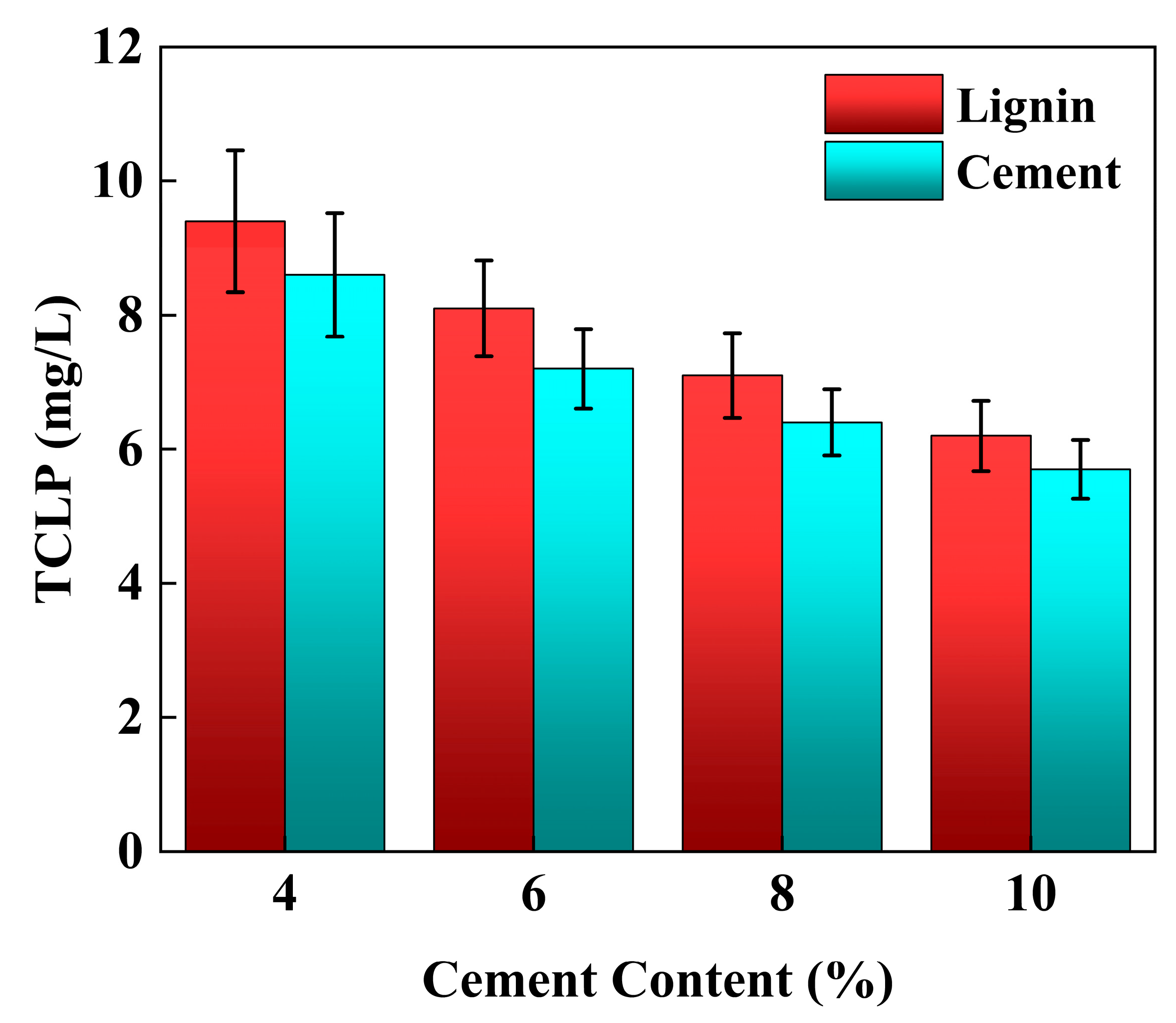

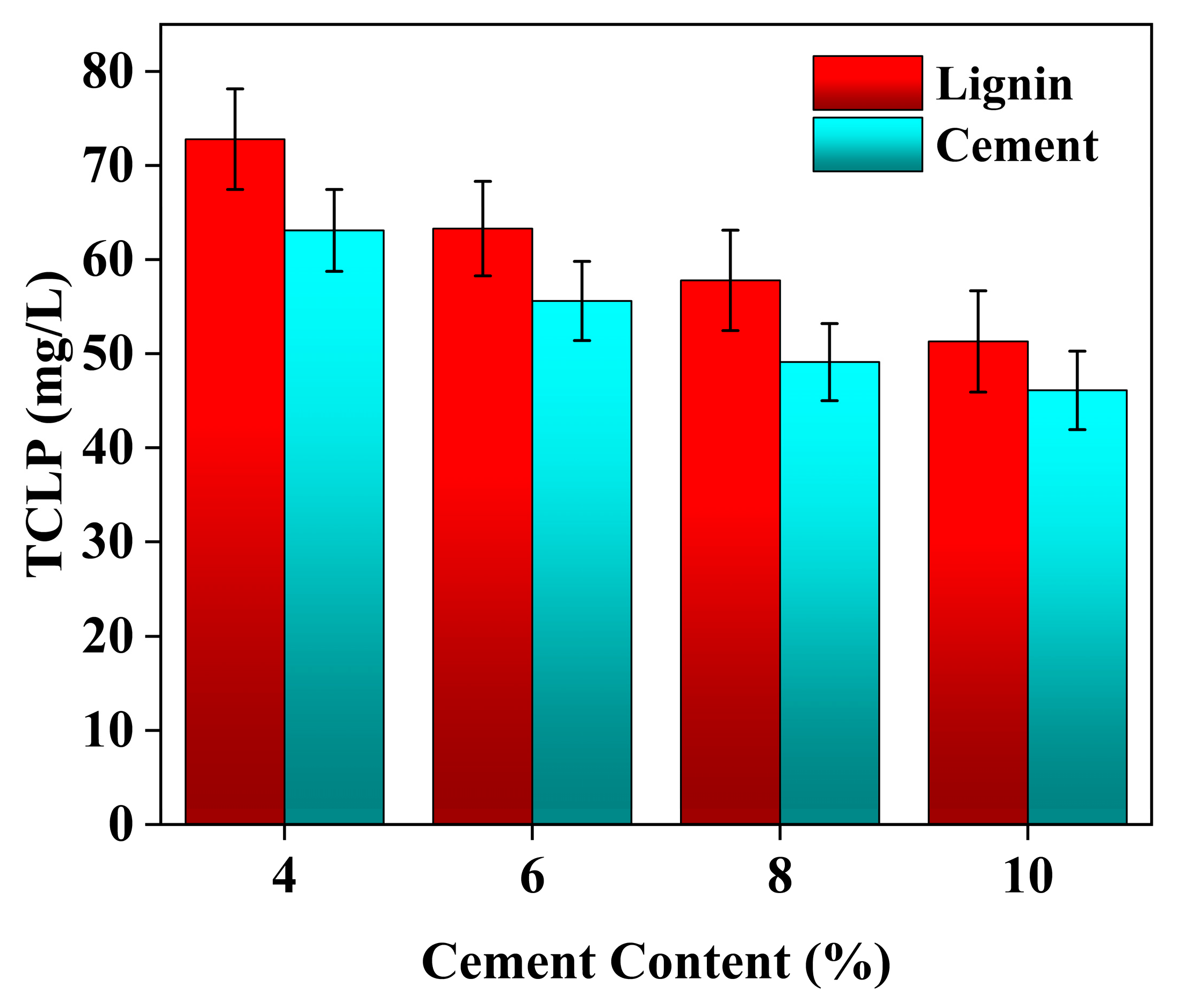

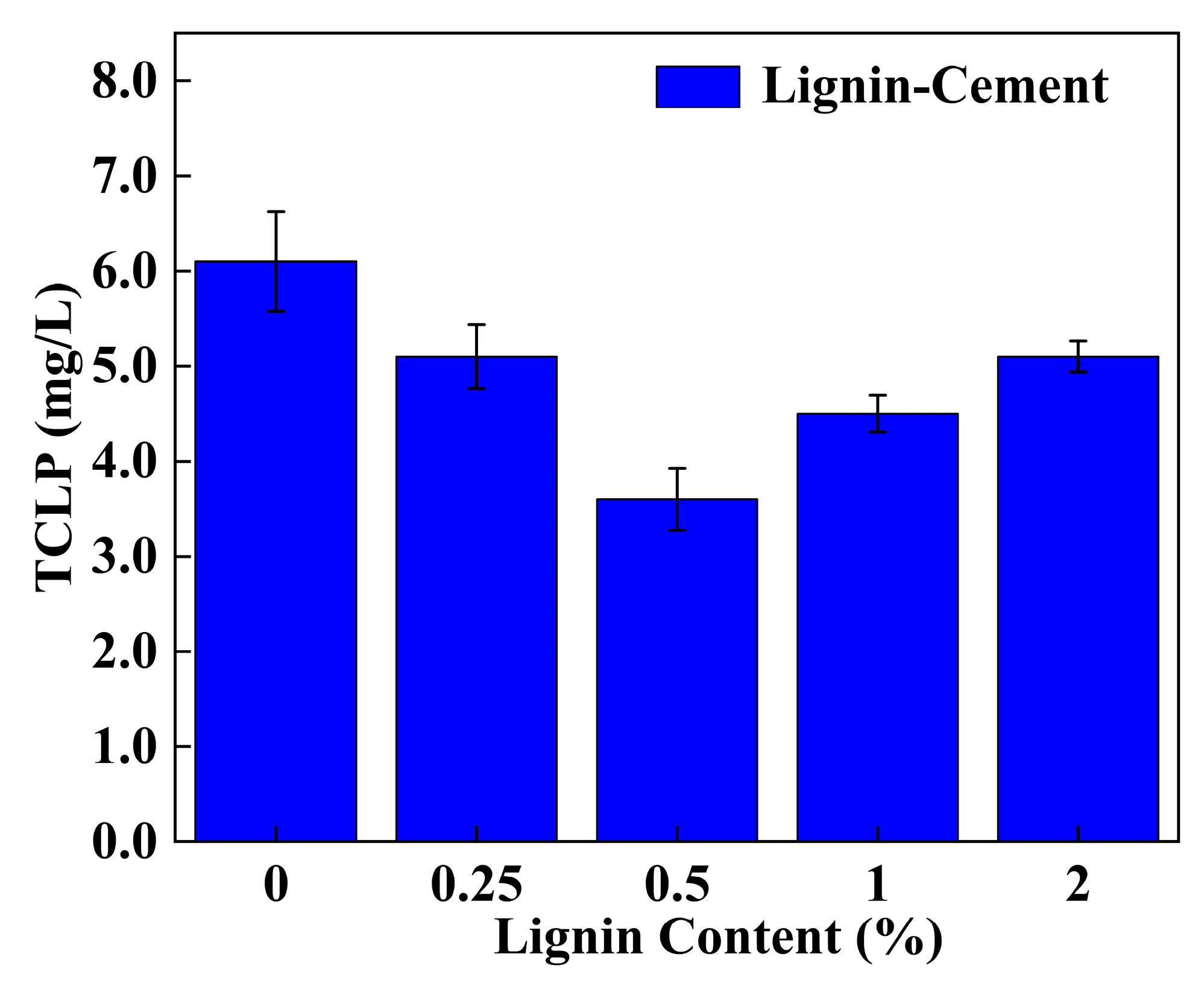

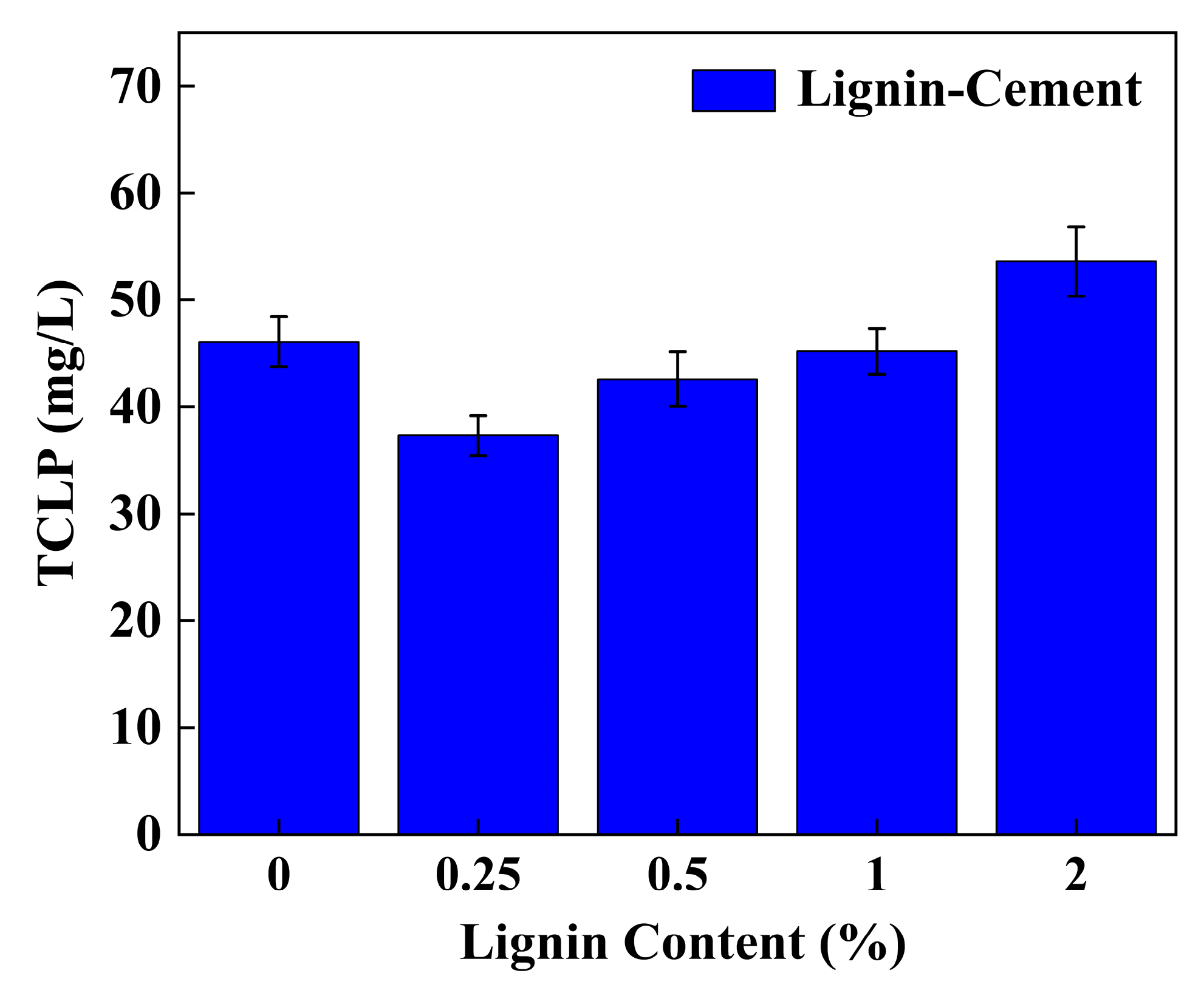

3.3. TCLP Leaching Characteristics

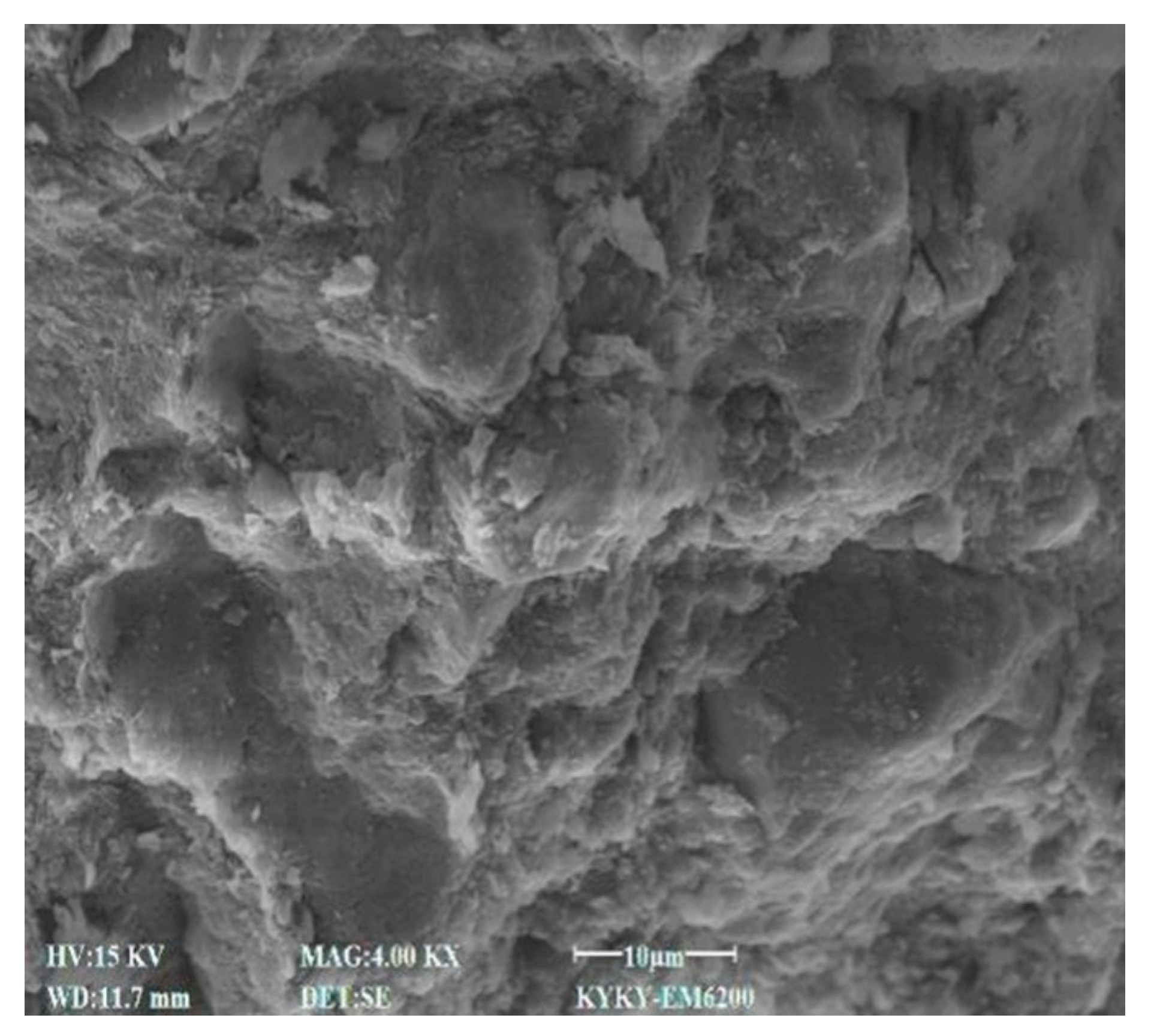

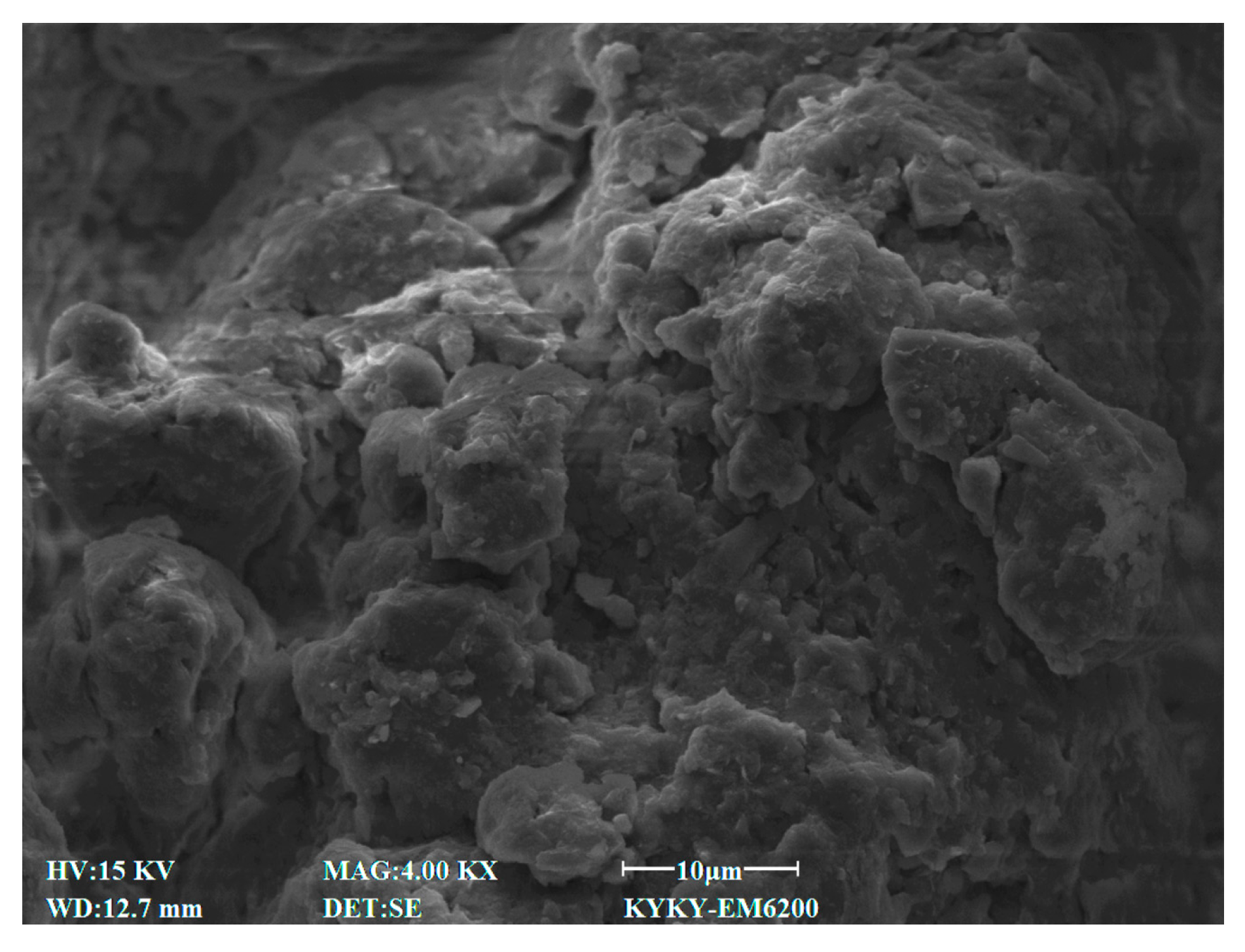

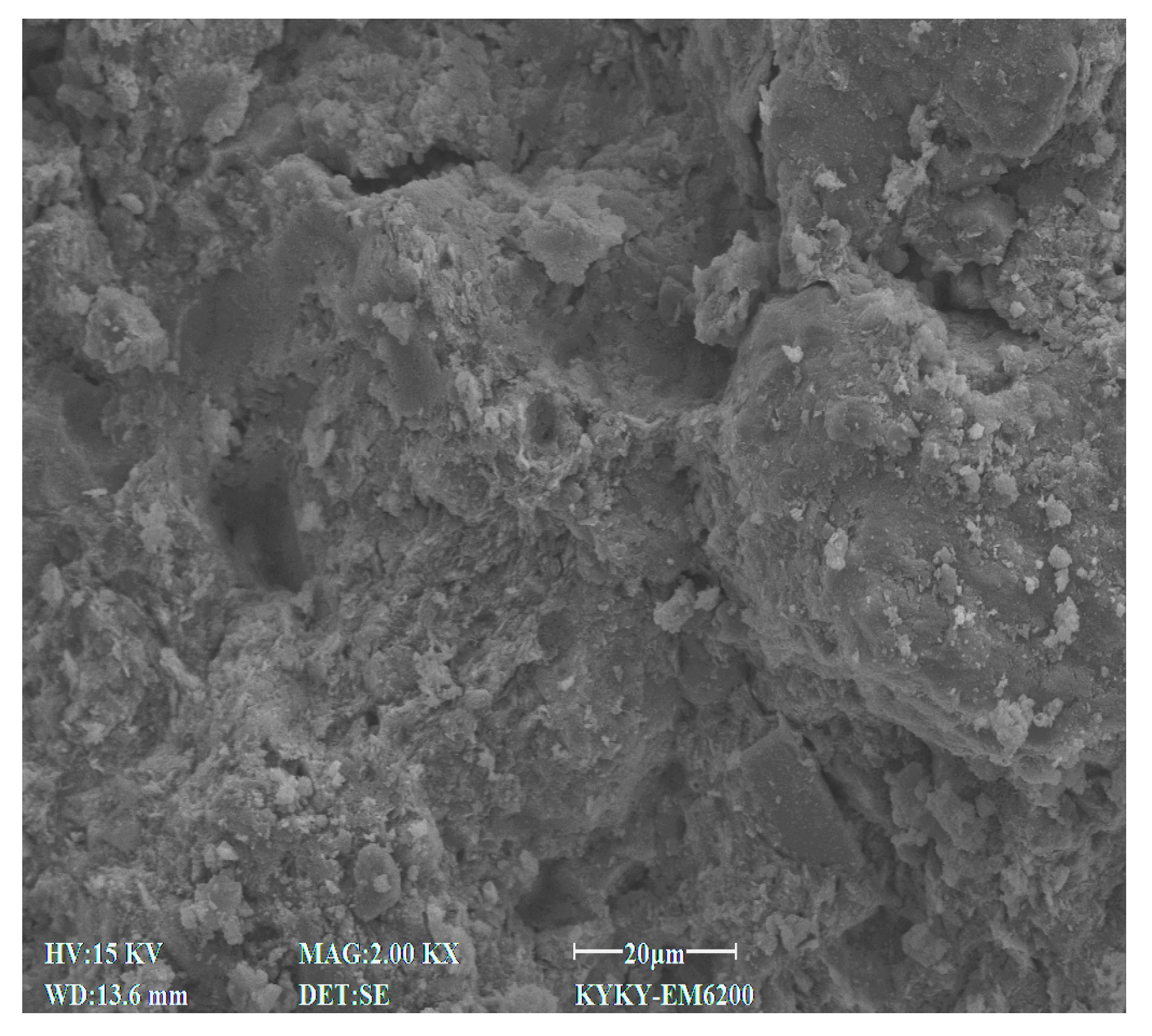

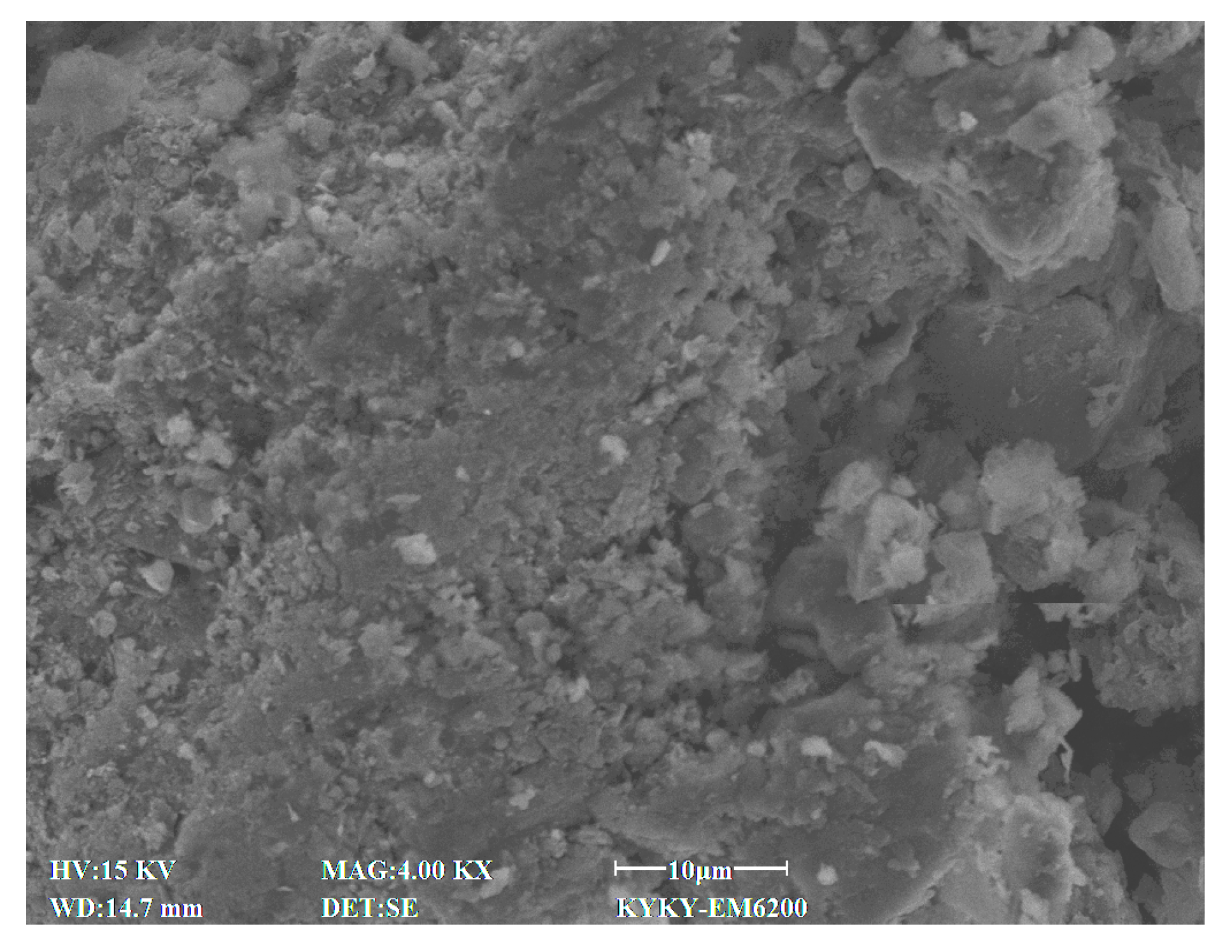

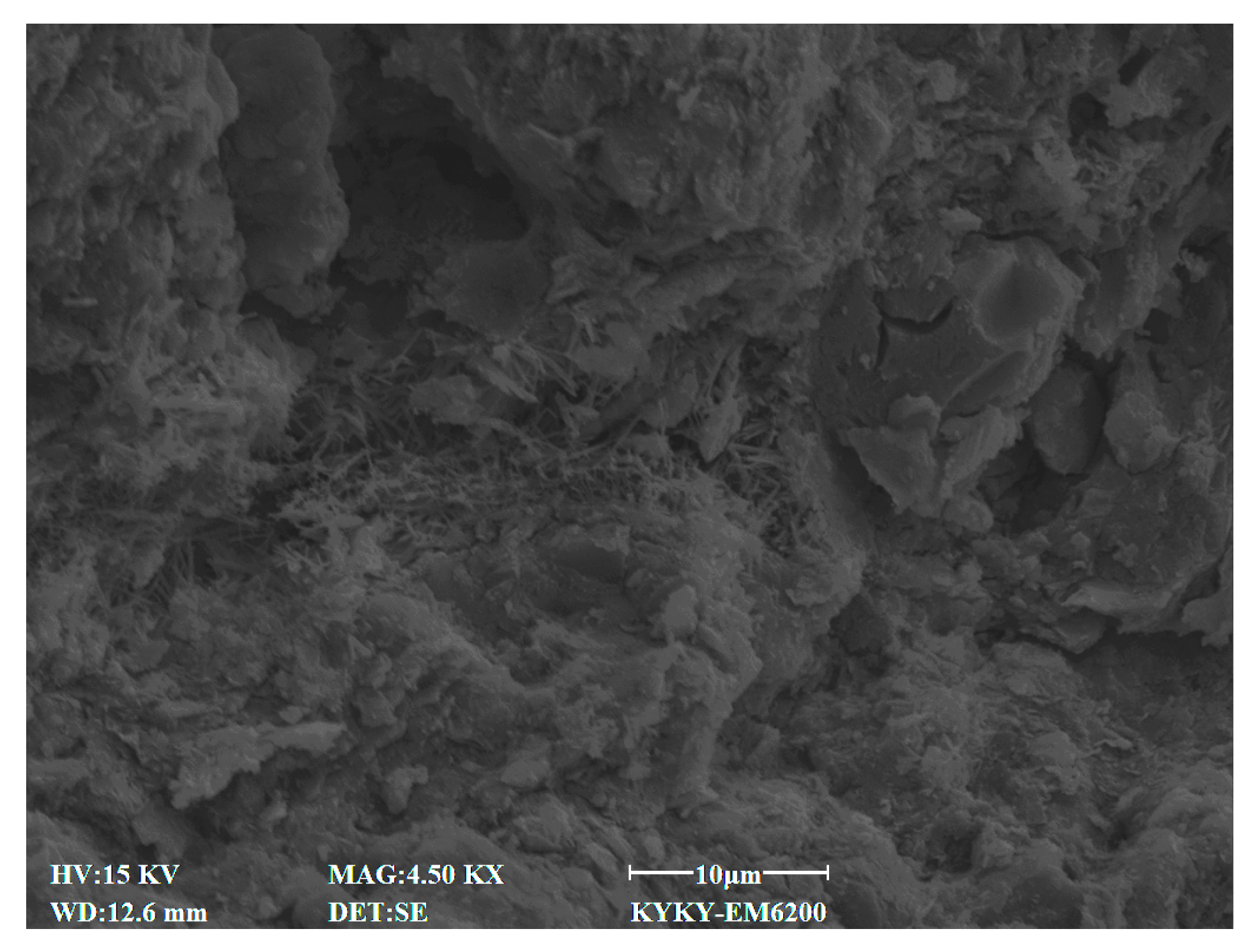

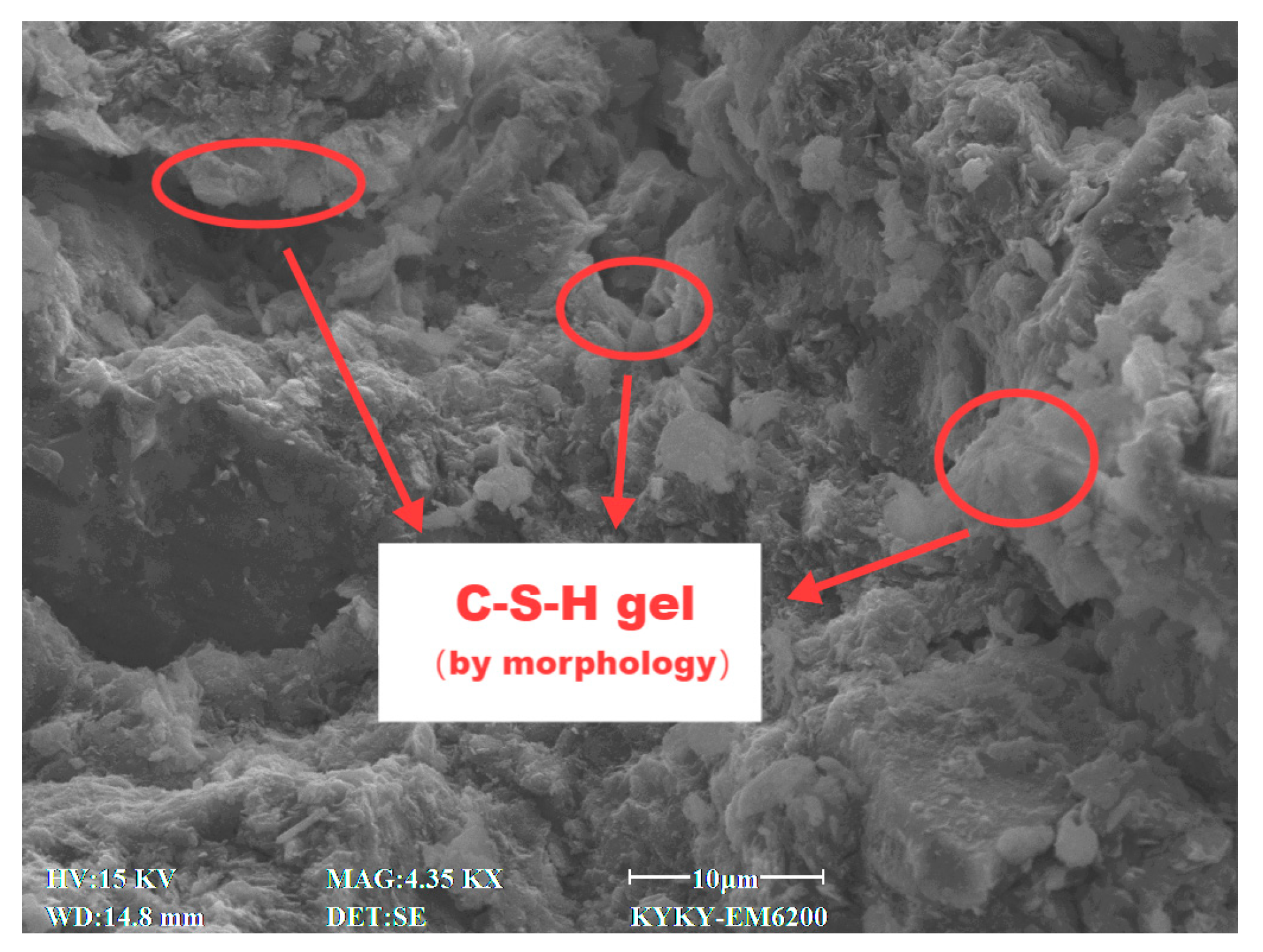

3.4. SEM Characteristics

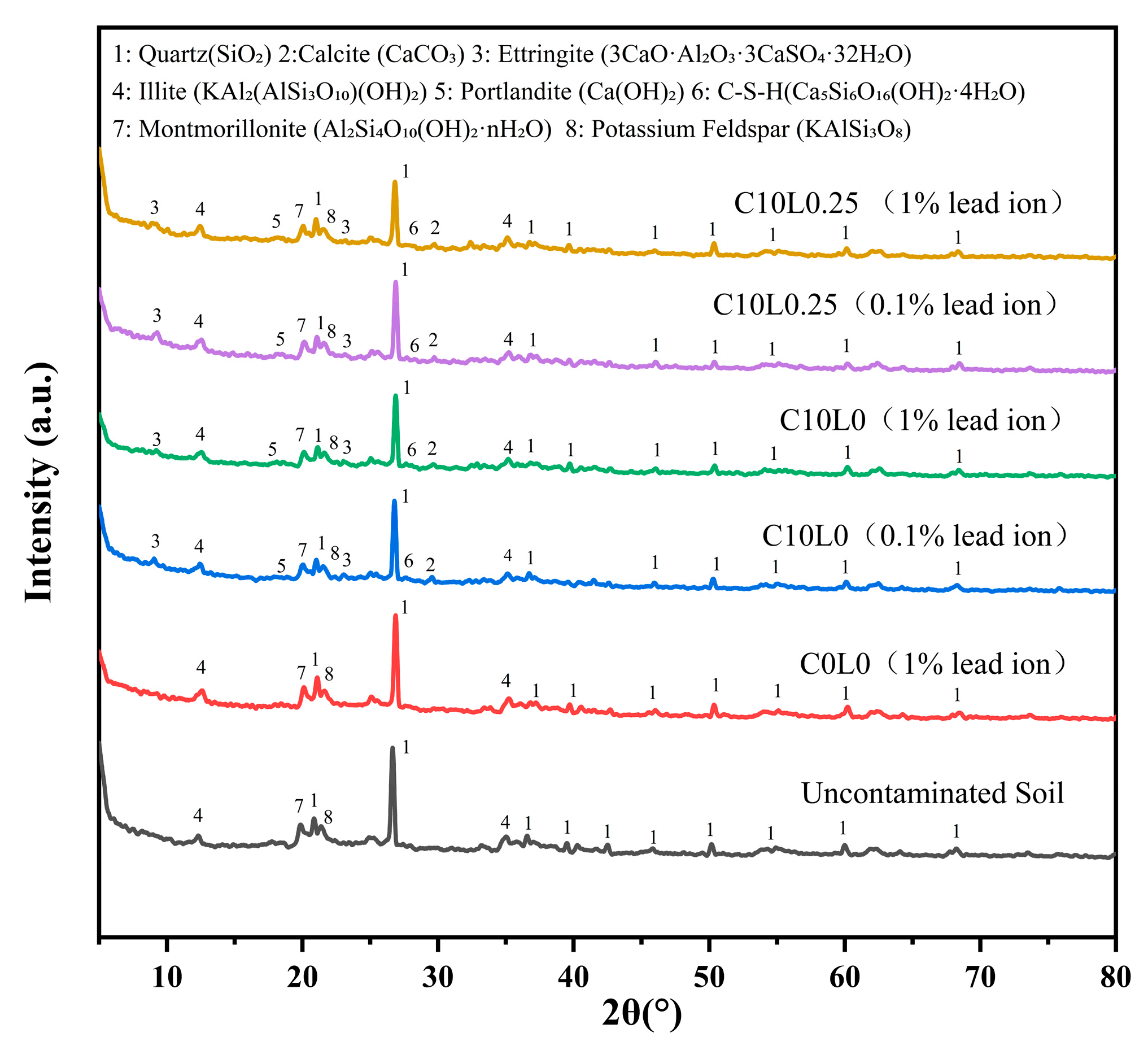

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction Characteristics

4. Discussion

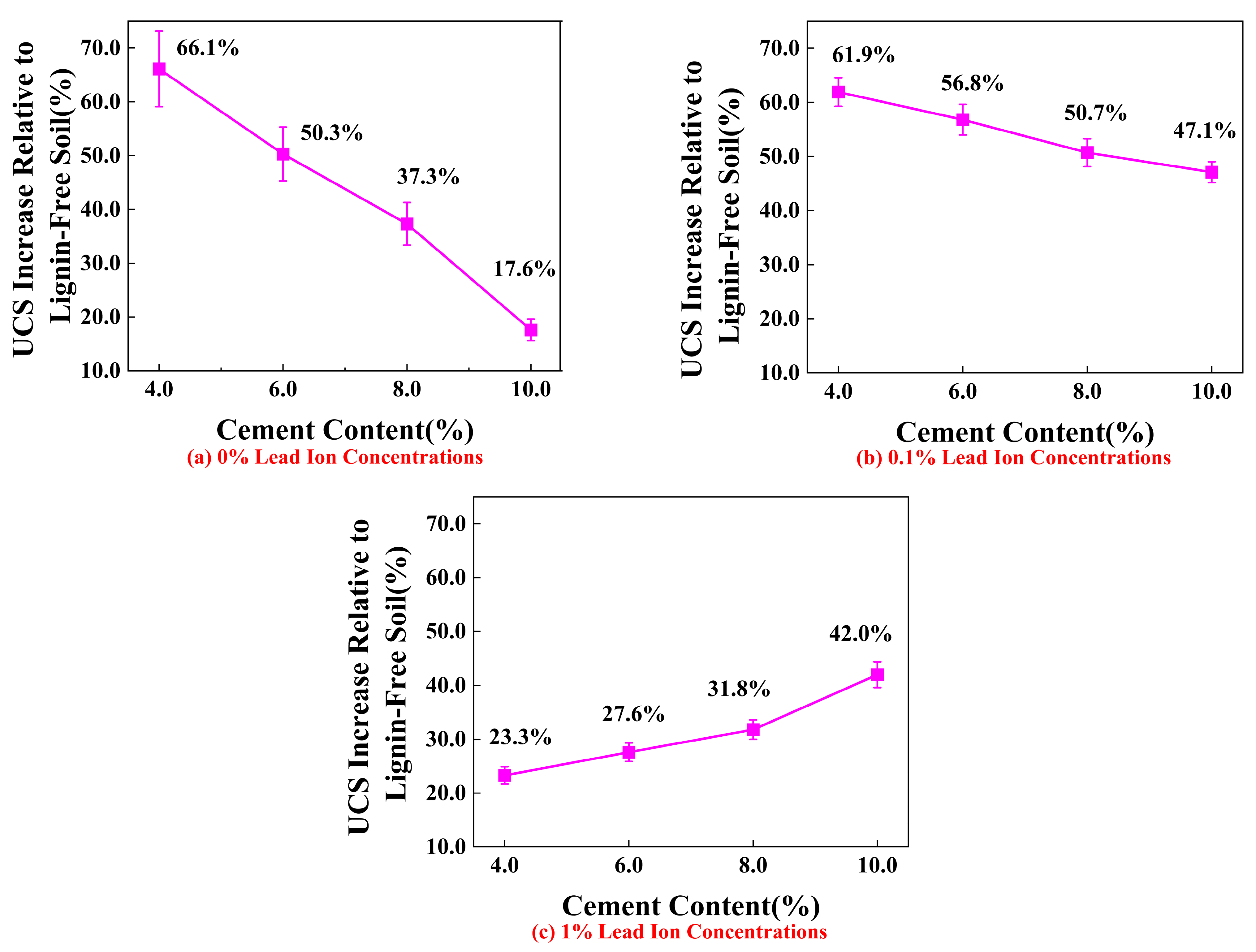

4.1. Effect of Lignin Content on UCS of Stabilized Soil

4.2. Effect of Cement Content on UCS of Stabilized Soil

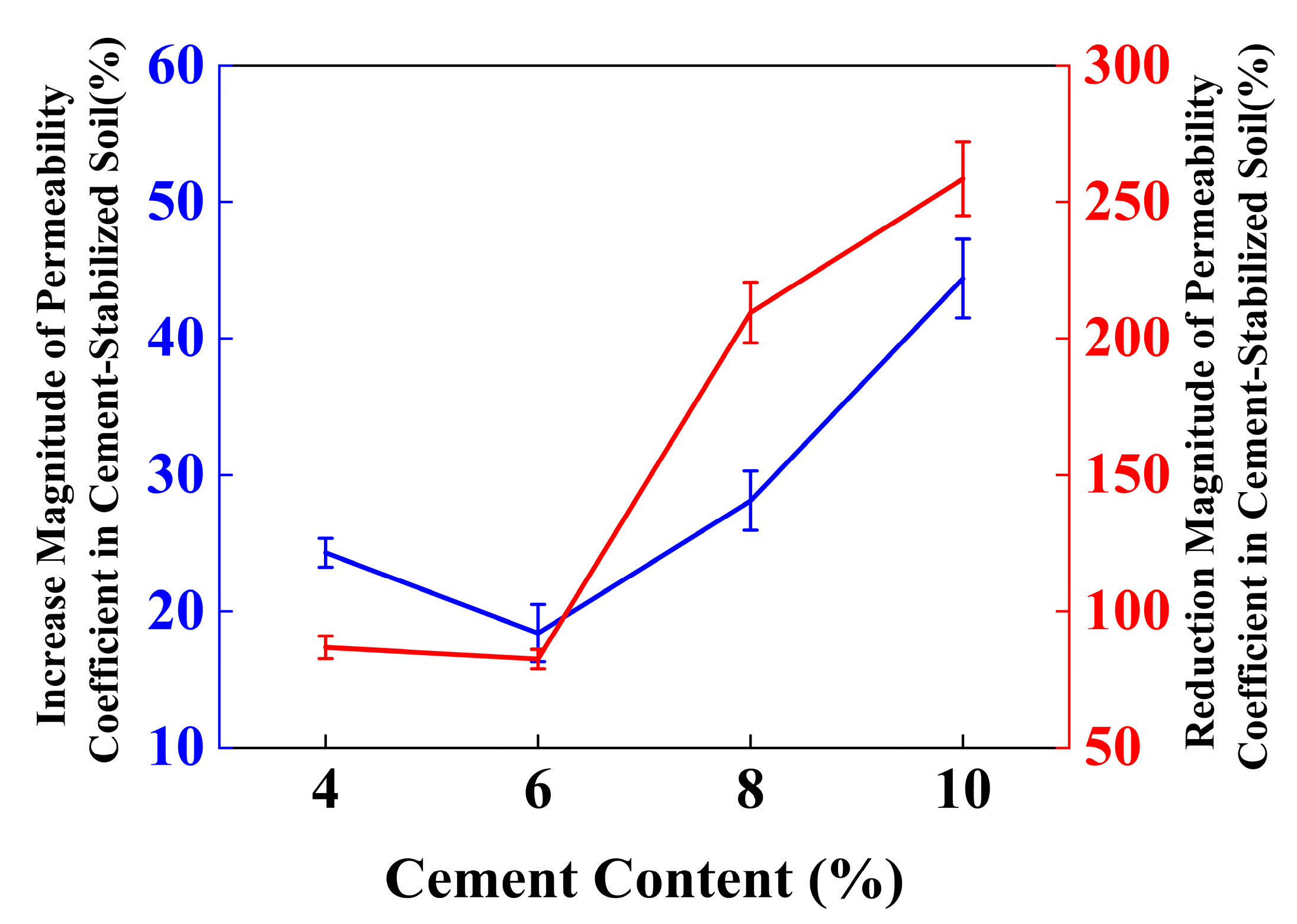

4.3. Effect of Lignin Content on Permeability Coefficient of Stabilized Soil

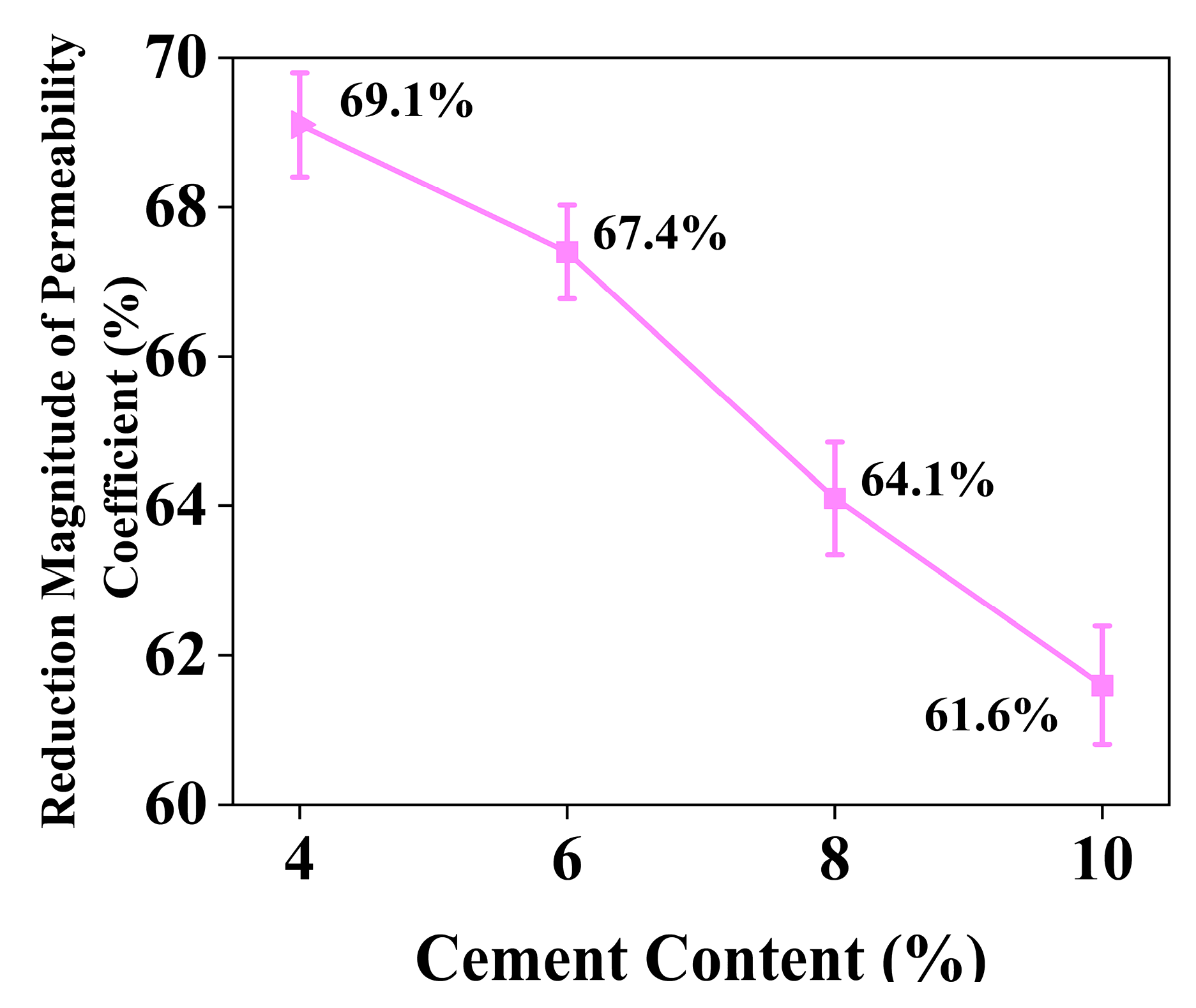

4.4. Effect of Cement Content on the Permeability Coefficient of Stabilized Soil

4.5. Effect of Individual Addition of Lignin and Cement on TCLP Concentration of Stabilized Soil

4.6. Effect of Lignin Content on TCLP Concentration of Cement-Stabilized Soil

4.7. Effect of Cement Content on Microstructural Characteristics of Stabilized Soil

4.8. Effect of Lignin Content on Microstructural Characteristics of Stabilized Soil

4.9. XRD Mineral Composition Analysis

4.10. Performance Comparison and Practical Implications of the Best-Performing Formulations

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Lead Ion Concentrations (%) | a | b | Fitting Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1611.64 | 0.1363 | 0.9669 | |

| 0.1 | 1276.83 | 0.1220 | 0.9890 | |

| 1 | 1274.20 | 0.0876 | 0.9895 |

| Lead Ion Concentrations (%) | a | b | Fitting Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2580.21 | 0.9560 | 0.9929 | |

| 0.1 | 1299.00 | 0.1196 | 0.9985 | |

| 1 | 1257.72 | 0.1235 | 0.9454 |

| Lead Ion Concentrations (%) | a | b | Fitting Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 498.98 | 2162.34 | 0.9752 | |

| 0.1 | 2018.84 | 0.1146 | 0.9729 | |

| 1 | 1390.87 | 0.0976 | 0.9450 |

| Lead Ion Concentrations (%) | a | b | Fitting Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 423.82 | 3094.33 | 0.9681 | |

| 0.1 | 626.66 | −218.52 | 0.9633 | |

| 1 | 136.22 | 1163.94 | 0.9244 |

| Lead Ion Concentrations (%) | a | b | Fitting Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 417.41 | 2898.11 | 0.9553 | |

| 0.1 | 605.37 | −474.69 | 0.9209 | |

| 1 | 87.46 | 998.95 | 0.9133 |

References

- Song, P.; Xu, D.; Yue, J.; Ma, Y.; Dong, S.; Feng, J. Recent advances in soil remediation technology for heavy metal contaminated sites: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calgaro, L.; Contessi, S.; Bonetto, A.; Badetti, E.; Ferrari, G.; Artioli, G.; Marcomini, A. Calcium aluminate cement as an alternative to ordinary Portland cement for the remediation of heavy metals contaminated soil: Mechanisms and performance. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ni, P.; Yi, Y. Comparison of reactive magnesia, quick lime, and ordinary Portland cement for stabilization/solidification of heavy metal-contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouzbakht, S.; Gitipour, S.; Baghdadi, M. Impact of hydrochar in stabilization/solidification of heavy metal-contaminated soil with Portland cement. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L.; Huang, C.; Li, Z.; Ruan, S.; Peng, B.; Li, M.; Liang, Q.; Yin, K.; Lu, S. Heavy metals immobilization of LDH@biochar-containing cementitious materials: Effectiveness and mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, D.; Li, X.; Lin, Q.; Yin, G.; Zhang, M.; Hu, H. Potassium lignosulfonate as a washing agent for remediating lead and copper co-contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Duan, G.; Lin, A.; Zhang, T.; Li, S. Enhanced remediation of Cr(VI)-contaminated soil by modified zero-valent iron with oxalic acid on biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Zou, Y.; Wu, Y.; Mao, W.; Zhang, J.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M.; Wang, B.; Wu, P. Quantification of the effect of biochar application on heavy metals in paddy systems: Impact, mechanisms and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medha, I.; Chandra, S.; Vanapalli, K.R.; Samal, B.; Bhattacharya, J.; Das, B.K. (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane and iron rice straw biochar composites for the sorption of Cr (VI) and Zn (II) using the extract of heavy metals contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, M.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, D.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, J. Efficient Pb(II) removal from contaminated soils by recyclable, robust lignosulfonate/polyacrylamide double-network hydrogels embedded with Fe2O3 via one-pot synthesis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H. Adsorption characteristics of modified rice straw biochar for Zn and in-situ remediation of Zn contaminated soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zhang, J.; Fang, P.; Suo, C. Study on Properties of Copper-Contaminated Soil Solidified by Solid Waste System Combined with Cement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsad, A.; Bahraq, A.A.; Khalid, H.R.; Alamutu, L.O. Stabilization/solidification of heavy metal-contaminated marl soil using a binary system of cement and fuel fly ash. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1557. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y. Stabilization/Solidification of Heavy Metals and PHe Contaminated Soil with β-Cyclodextrin Modified Biochar (β-CD-BC) and Portland Cement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Ge, C.; Zhao, G.; Hou, S. Sustainable Stabilization of Cadmium (Cd)-Contaminated Soil with Biochar-Cement: Evaluation of Strength, Leachability, Microstructural Characteristics, and Stabilization Mechanism. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2025, 34, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. Cyclic drying and wetting tests on combined remediation of chromium-contaminated soil by calcium polysulfide, synthetic zeolite and cement. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 91282–91284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, F.; Liu, J.; Xu, D.; Kang, B.; Yang, C.; Deng, Y. Solidification/Stabilization (s/s) of Zinc Contaminated Soils Using Cement Blended with Soda Residue. Environ. Geotech. 2020, 10, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C. The Structural Mechanism of Calcium Lignosulfonate-Modified Loess Stabilization. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 59, 468–475. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Zhou, H.; Deng, B.; Wang, D.; Zhu, J. Mechanical Properties Test and Microscopic Mechanism of Lignin Combined with EICP to Improve Silty Clay. Sustainability 2025, 17, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ou, M. Experimental Study on Expansive Soil Improved by Lignin and Its Derivatives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, Z.; Hu, T.; Li, D.; Wei, X.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Contaminated soil remediation with nano-FeS loaded lignin hydrogel: A novel strategy to produce safe rice grains while reducing cadmium in paddy field. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Mi, B.; Luo, C.; Tao, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Mo, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Tu, N.; et al. A novel strategy employing lignin biochar to simultaneously promote remediation and safe crop production in Cd-contaminated soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, J.; Tang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Q. Remediation of cadmium and lead contaminated soils using Fe-OM based materials. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.N.; Guo, X.; Chng, M.L.; Ibrahim, M.; Bashir, M.J. Effect of Lignin and Commercial Plant Extract on the Fractionation of Heavy Metals in Multi-Metal Contaminated Soil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2024, 15, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 36600-2018; Soil Environmental Quality-Risk Control Standard for soil Contamination of Development Land. Ministry of Ecology and Environment & State Administration for Market Regulation, China Environment Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Methods. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- HJ/T 300-2007; Solid Waste-Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity-Acetic Acid Buffer Solution Method. Institute of Solid Waste Pollution Control Technology, Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, Environmental Protection Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB 5085.3-2007; Identification Standards for Hazardous Wastes-Identification for Extraction Toxicity. Institute of Solid Waste Pollution Control Technology, Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Guo, J.; Xu, M.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. Growth and morphology of ettringite fibres. J. Hebei Univ. Technol. 2023, 52, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Sun, W.K.; Chen, L.Q. Research on the Mechanisms of Soil Agent Solidifying Buildings Residues. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 1450, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Moisture Content (%) | Liquid Limit (%) | Plastic Limit (%) | Specific Gravity | Maximum Dry Density (g/cm3) | Optimum Moisture Content (%) | PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28.2 | 51.2 | 26.1 | 2.76 | 1.75 | 19.1 | 6.2 |

| Bulk Density (g·m−3) | Specific Surface Area (m2·kg−1) | Initial Setting Time | Final Setting Time | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Soundness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3d | 28d | |||||

| 1.65 | 300 | 160 | 332 | 23.8 | 45.4 | Qualified |

| Lead Ion Content (%) | Lignin Content (%) | Cement Content (%) | Curing Age (d) | Number of Test Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0, 0.25, 0.50, 1, 2 | 4, 6, 8, 10 | 28 | 60 |

| 0.1 | 0, 0.25, 0.50, 1, 2 | 4, 6, 8, 10 | ||

| 1 | 0, 0.25, 0.50, 1, 2 | 4, 6, 8, 10 |

| Lead Ion Content (%) | Lignin Content (%) | Cement Content (%) | Curing Ag (d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1,2 | 4, 6, 8, 10 | 28 |

| 1 |

| Test Series | Lead Ion Content (%) | Lignin Content (%) | Cement Content (%) | Curing Period (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lignin-only Cement-only | 0.1, 1 | 4, 6, 8, 10 | 0 | 28 |

| 0 | 4, 6, 8, 10 | |||

| Lignin–Cement Composite | 0.1 | 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 | 10 | |

| 1 | 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 |

| Lignin Content (%) | Lead Ion Concentration (%) | Parameter a | Parameter b | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.1 | −4.612 | 11.947 | 0.9795 |

| 1.0 | −6.122 | 15.751 | 0.9426 | |

| 0.25 | 0.1 | −5.051 | 12.673 | 0.9551 |

| 1.0 | −3.832 | 9.655 | 0.9557 | |

| 0.5 | 0.1 | −1.239 | 3.430 | 0.9677 |

| 1.0 | −5.248 | 13.748 | 0.9544 | |

| 1.0 | 0.1 | −2.532 | 6.450 | 0.9784 |

| 1.0 | −6.181 | 18.471 | 0.9749 | |

| 2.0 | 0.1 | −2.837 | 23.360 | 0.9496 |

| 1.0 | −7.431 | 23.360 | 0.9133 |

| Lead Concentration | Best-Performing Formulation | UCS (MPa) | Permeability | TCLP Leaching Concentration (mg/L) | Cost-Effectiveness (Material Cost) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% | C4L0.5 | 2361.5 ± 95.4 | reduction rate reached 69.1% | 3.6 ± 0.1 (<5) | Low cement content |

| 1% | C10L0.25 | 3604.7 ± 110.9 | reduction rate reached 76.78% | 37.3 ± 1.9 (>5) | High cement content |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Huang, B.; Chen, A.; Shi, X.; Li, S.; Xiao, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhao, L. Research on Engineering Characteristics of Lignin–Cement-Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Lateritic Clay. Buildings 2025, 15, 4433. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244433

Chen J, Wei X, Huang B, Chen A, Shi X, Li S, Xiao Y, Liao X, Zhao L. Research on Engineering Characteristics of Lignin–Cement-Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Lateritic Clay. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4433. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244433

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Junhua, Xiulin Wei, Bocheng Huang, Aijun Chen, Xiong Shi, Shouqian Li, Ying Xiao, Xiao Liao, and Liuxuan Zhao. 2025. "Research on Engineering Characteristics of Lignin–Cement-Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Lateritic Clay" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4433. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244433

APA StyleChen, J., Wei, X., Huang, B., Chen, A., Shi, X., Li, S., Xiao, Y., Liao, X., & Zhao, L. (2025). Research on Engineering Characteristics of Lignin–Cement-Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Lateritic Clay. Buildings, 15(24), 4433. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244433