Study on the Influence Mechanism of Metro-Induced Vibrations on Adjacent Tunnels and Vibration Isolation Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Determination of the similarity ratios.

- Fabrication of the model box, including the metro and power tunnels.

- Selection of the model soil.

- Design of the excitation system to simulate train vibrations.

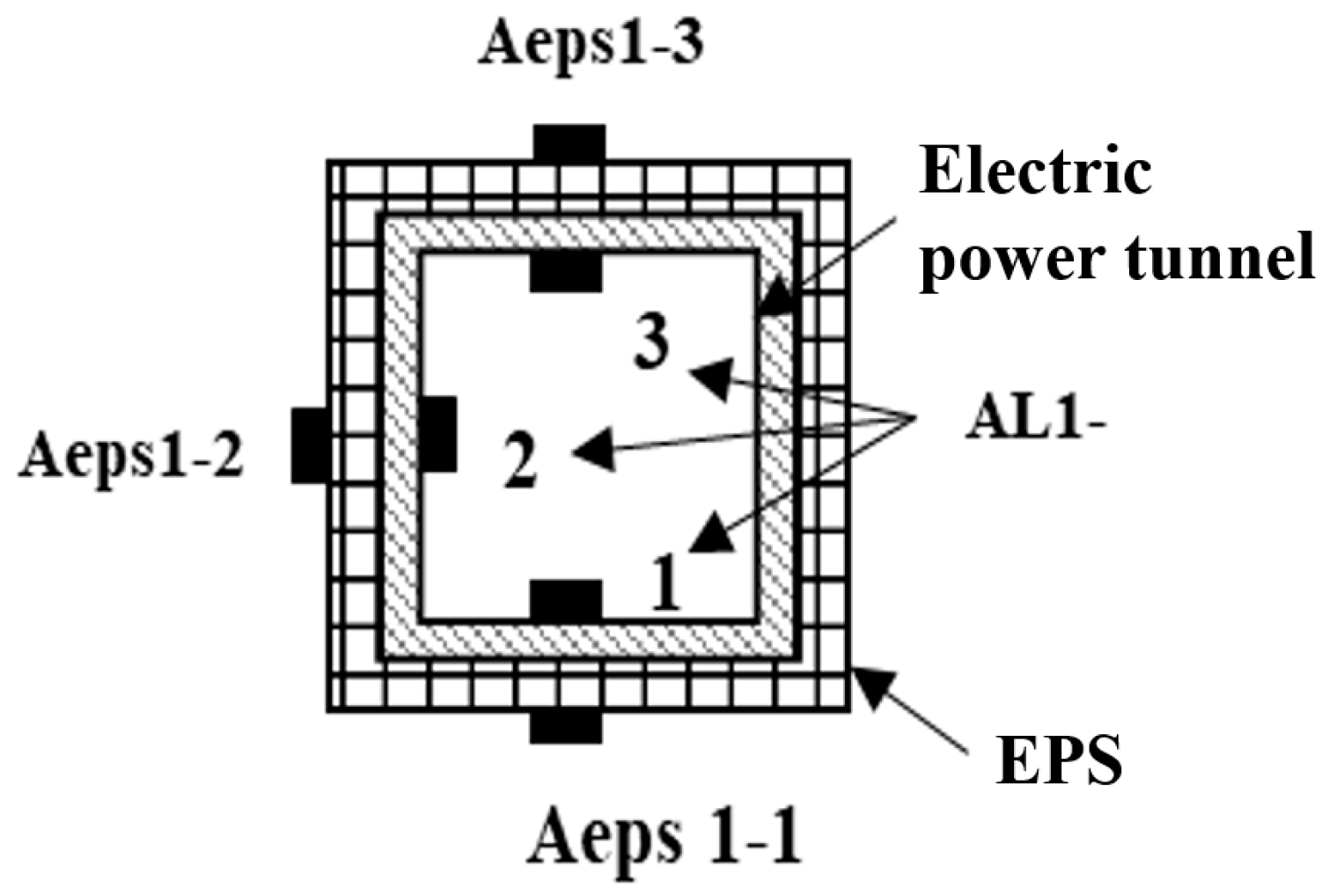

- Layout of key measurement points and instrumentation.

- Selection and configuration of the vibration isolation materials (EPS and rubber particles).

2. Test Method

2.1. Test Device and Principle

2.2. Materials

- (1)

- Model Soil

- (2)

- Tunnel Materials

- (3)

- Vibration Mitigation and Isolation Materials

2.3. Test Loads

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Structural Response of the Power Tunnel Without Vibration Isolation Measures

- (1)

- Acceleration Response

- (2)

- Dynamic Strain Response

- (3)

- Earth Pressure Response

3.2. Structural Response of the Power Tunnel with Vibration Isolation Measures

- (1)

- Acceleration Response

- (2)

- Dynamic Strain Response

- (3)

- Earth Pressure Response

3.3. Comparison of Power Tunnel Structural Responses Under Different Vibration Isolation Measures

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Vibration Acceleration Attenuation Pattern: The vibration acceleration generally decreases with increasing distance from the source. The soil exhibits a stronger suppressive effect on high-frequency vibrations, which attenuate more rapidly, while mid-to-low frequency vibrations attenuate relatively more slowly. The acceleration is highest in the soil beneath the tunnel lining, followed by the side sections, and is relatively lower in the upper part.

- (2)

- Spatial Variation and Special Phenomena in Vibration Propagation: During upward propagation, vibrations attenuate in all directions, with the fastest attenuation in the transverse direction, followed by the longitudinal direction, and the slowest in the vertical direction. When propagating to a certain distance near the ground surface or structures, some mid-to-low frequency vibrations do not continue to decrease but may rebound and increase.

- (3)

- Vibration Mitigation Effectiveness of EPS and Rubber Particles: The model tests show that the attenuation ratios of vibration acceleration for EPS and rubber particles are 60% and 41%, respectively. Both materials can reduce the peak acceleration. A steeper attenuation slope is observed at the isolation layer location, and EPS demonstrates superior vibration attenuation compared to rubber particles, indicating better overall performance.

- (4)

- Based on comparative observations of material changes before and after testing, and in light of the material properties and existing research [20], the vibration isolation mechanisms of the two materials are inferred as follows: EPS dissipates vibration energy through compression-induced gas release and foam deformation, accompanied by inter-particle sliding friction, while rubber particles achieve energy dissipation via minor elastic deformation, inter-particle sliding friction, and gap filling effects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.L.; Cui, Z.D. Dynamic response of soil around the tunnel under subway vibration loading. In Proceedings of the GeoShanghai 2018 International Conference; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhong, M.; Zhao, H. Study on the vibration effect on operation subway induced by blasting of an adjacent cross tunnel and the reducing vibration techniques. J. Vibroengineering 2013, 15, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Cao, Z.; Sun, H.; Xu, C. Effects of the dynamic wheel–rail interaction on the ground vibration generated by a moving train. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2010, 47, 2246–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Jones, C. Coupled boundary and finite element analysis of vibration from railway tunnels—A comparison of two- and three-dimensional models. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Random large-deformation modelling on face stability considering dynamic excavation process during tunnelling through spatially variable soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Wen, C.; Bao, R.; Ma, S. Vibration Response and Cumulative Fatigue Damage Analysis of Overlapped Subway Shield Tunnels. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Yao, C.; Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, X. Analysis on the Dynamic Responses of an Overlapped Circular Shield Tunnel under the Different Vibration Loads. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 3131–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, M.; Crespi, P.; Tropeano, G.; Simoncelli, M. On the Influence of Shallow Undergorund Structures in the Evaluation of the Seismic Signals. Ing. Sismica 2021, 38, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Huang, N.; Muhammad; Xu, C.; Tong, L. Negative Poisson’s ratio locally resonant seismic metamaterials vibration isolation barrier. Acta Mech. Sin. 2024, 40, 523370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, C.; Pu, X.; Guo, W.; Tong, L. Analytical modeling for nonlinear seismic metasurfaces of saturated porous media. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 303, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Huang, N.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zeng, C.; Tong, L. A locally resonant metamaterial and its application in vibration isolation: Experimental and numerical investigations. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 53, 4099–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Y. Vibration reduction performance of rubber concrete backfill layer in high-speed railway tunnel. Noise Vib. Worldw. 2019, 50, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, J.; Haghighi, E.; Esmaeili, M. Effectiveness of grouted layer in the mitigation of subway-induced vibrations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F-J. Rail Rapid Transit. 2023, 237, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chango, I.V.L.; Chen, J. Numerical and Statistical Evaluation of the Performance of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers as Tunnel Lining Reinforcement during Subway Operation. Buildings 2022, 12, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Konagai, K. Seismic isolation effect of a tunnel covered with coating material. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2000, 15, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasheminejad, S.M.; Miri, A.K. Seismic isolation effect of lined circular tunnels with damping treatments. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2008, 7, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Seismic Isolation Effect of a Tunnel Covered with Expanded Polystrene Geofoam. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 194–196, 1943–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Lu, X.Z. Study on the Influence of Damping Materials on the Seismic Dynamic Response of Retaining Walls. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Bathurst, R.J. Research on shock mitigation on circular tunnels using expanded polystyrene. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electric Technology and Civil Engineering: ICETCE 2011, Lushan, China, 22–24 April 2011; Volume 1, pp. 2528–2531. [Google Scholar]

| Name of Physical Quantity | Physical Quantity | Name of Physical Quantity | Physical Quantity | Name of Physical Quantity | Physical Quantity | Name of Physical Quantity | Physical Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | L | Mass | M | Poisson’s Ratio | ν | Velocity | v |

| Displacement | u | Time | T | Density | ρ | Acceleration | a |

| Area | A | Frequency | F | Cohesion | C | Gravitational Acceleration | g |

| Stress | σ | Concentrated Load | F | Friction Coefficient | μ | Surface Load | p |

| Strain | ε | Elastic Modulus | E |

| Name of Physical Quantity | Fundamental Dimensions | Similarity Relation | Scaling Ratio | Name of Physical Quantity | Fundamental Dimensions | Similarity Relation | Scaling Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | [] | 15 | Friction Coefficient | — | 1 | ||

| Displacement | [] | 15 | Concentrated Load | [][][]−2 | 875 | ||

| Area | []2 | 125 | Surface Load | [][]−1[]−2 | 7 | ||

| Stress | [][]−1[]−2 | 7 | Mass | [] | 3375 | ||

| Strain | — | 1 | Time | [] | 5.66 | ||

| Elastic Modulus | [][]−1[]−2 | 7 | Frequency | []−1 | 0.17 | ||

| Poisson’s Ratio | — | 1 | Velocity | [][]−1 | 2.64 | ||

| Density | [][]−3 | 1 | Acceleration | [][]−2 | 0.466 | ||

| Cohesion | [][]−1[]−2 | 7 | Gravitational Acceleration | [][]−2 | 1 |

| Structure | Type | Unit Weight (kN/m3) | Elastic Modulus (kN/m2) | Shear Modulus (G/MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio (ν) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Prototype | 19.7 | 72.9 | 28.1 | 0.3 |

| Model | 19.7 | 14.56 | 6.27 | 0.3 |

| Structure | Type | Unit Weight (kN/m3) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (kN/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro Segment | Prototype | 24.2 | 60 | 34.5 |

| Scaled Model | 24.4 | 10.1 | 7.2 | |

| Trackbed | Prototype | 23.7 | 30 | 30 |

| Scaled Model | 23.9 | 6.3 | 6.1 | |

| Power Tunnel | Prototype | 23.9 | 40 | 32.5 |

| Scaled Model | 24.1 | 8.3 | 6.2 |

| Material | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Coefficient of Friction with Concrete | Coefficient of Friction with Soil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS | 1.6 | 0.075 | 0.69 | 0.3 |

| Rubber particles | 1.8 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.34 |

| Condition | Spatial Parallel Angle and Distance (m) | Axis Intersection Angle | Excitation Load | Frequency (Hz) | Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Power tunnel 0.8 m directly above metro tunnel | 0° | Sinusoidal Load | 15, 75, 225 | 0.35 |

| 2 | Power tunnel 0.8 m directly above metro tunnelEPS polyethylene foam vibration isolation and damping | 0° | Sinusoidal Load | 75 | 0.35 |

| 3 | Power tunnel 0.8 m directly above metro tunnelRubber particle isolation and vibration reduction | 0° | Sinusoidal Load | 75 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, Q.; Zhang, B.; Tang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, J. Study on the Influence Mechanism of Metro-Induced Vibrations on Adjacent Tunnels and Vibration Isolation Measures. Buildings 2025, 15, 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244412

Ye Q, Zhang B, Tang X, Zheng Y, Yuan J. Study on the Influence Mechanism of Metro-Induced Vibrations on Adjacent Tunnels and Vibration Isolation Measures. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244412

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Qige, Bin Zhang, Xingjia Tang, Yixuan Zheng, and Jie Yuan. 2025. "Study on the Influence Mechanism of Metro-Induced Vibrations on Adjacent Tunnels and Vibration Isolation Measures" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244412

APA StyleYe, Q., Zhang, B., Tang, X., Zheng, Y., & Yuan, J. (2025). Study on the Influence Mechanism of Metro-Induced Vibrations on Adjacent Tunnels and Vibration Isolation Measures. Buildings, 15(24), 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244412