1. Introduction

The construction industry is facing increasing pressure to reduce its environmental footprint due to intensive resource extraction, high energy consumption, and the generation of vast amounts of industrial waste [

1]. Concrete is the most widely used construction material, and the production of Portland cement alone is responsible for about 7–8% of global CO

2 emissions, while also consuming significant amounts of non-renewable resources such as limestone, marl, and clay [

2]. In this context, the valorization of industrial by-products and secondary raw materials into alternative binders presents a promising strategy for minimizing environmental impact and promoting circular economy principles [

3]. Recycling industrial residues mitigates landfill burden and offers opportunities to minimize the carbon emissions, lower energy consumption, and save natural resources.

Alkali activation has emerged as a viable and scalable solution for transforming various types of waste and by-products into cementitious binders [

4]. Alkali-activated materials (AAMs) rely on the chemical activation of aluminosilicate materials through alkaline solutions, leading to the formation of calcium-alumino-silicate-hydrates (C-A-S-H) or sodium(potassium)-aluminosilicate-hydrate (N(K)-A-S-H) gel phases [

3]. This low-carbon pathway allows the production of binders with mechanical and durability performance comparable or superior to that of traditional cement, while simultaneously utilizing large volumes of waste [

5]. The alkali activation enables the use of regionally available waste or by-products, tailored according to specific chemical compositions and reactivity [

6].

Among the various waste and by-products suitable for alkali activation, ladle furnace slag (LFS)—a secondary metallurgical residue from steel refining—is gaining attention due to its high calcium and alumina content [

7]. Although traditionally considered less reactive than ground granulated blast furnace slag, recent studies have demonstrated that LFS can be effectively alkali-activated under optimized conditions [

8]. Most commonly, alkali activation involves the use of commercial sodium silicate solutions in combination with sodium or potassium hydroxide [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. For instance, Adenasanya et al. reported compressive strengths of up to 65 MPa in alkali-activated LFS pastes prepared using conventional alkaline solutions [

14].

Despite these promising results, the widespread application of traditional silicate-based activators is limited by their high cost, energy-intensive production, and footprint, which challenges their sustainability in large-scale applications [

15]. The use of alternative activators is key for zero-carbon alkali-activated and geopolymer cements. Alternative activator solutions based on industrial waste streams—such as waste-derived sodium silicate solutions [

16,

17], anodizing etching solution [

18], Bayer liquor [

19], textile waste water [

20]—offer a promising route to reduce both environmental impact and production costs. However, in the specific case of LFS, the vast majority of research still relies on conventional activators (alkali silicate and hydroxide solutions), with very limited pioneer studies exploring alternatives such as sunflower shell biomass fly ash [

21]. This highlights a significant research gap: the exploration of abundant industrial waste as an activator for ladle furnace slag binder systems.

Furthermore, the development of dry-state activators enables the formulation of so-called “one-part” alkali-activated binders, which require only the addition of water on site, thereby simplifying handling and improving safety. Solid precursors such as desulfurization dust [

22], biomass ash [

21,

23], and cement kiln dust [

24,

25] have shown potential not only as alkali sources but also as reactive mineral additions that enhance microstructure densification and performance. Cement kiln dust (CKD) and cement by-pass dust are fine particulate by-products of cement manufacturing and contain notable amounts of free lime, sulfates, and alkalis—components that can actively contribute to the activation process [

26]. CKD has been employed as a partial or even complete substitute for commercial alkali activators in several systems, including pozzolanic material [

24], fly ash [

27], metakaolin [

28], and blast furnace slag [

29]. CKD is promising as an activator in applications where a moderate rather than highly alkaline environment is preferred.

In addition to the use of LFS as a primary precursor, numerous studies have highlighted the beneficial role of incorporating additional reactive aluminosilicate materials to improve both the chemical reactivity and mechanical performance of alkali-activated systems [

30]. These supplementary materials enhance the development of reaction products and contribute to the improved workability, setting behavior, and long-term durability of the hardened matrix [

31]. The aluminosilicate reactive phase facilitates the formation of a more complex and stable binder gel—often referred to as a hybrid C-A-S-H/N-A-S-H matrix [

3]. Among the most widely studied reactive aluminosilicate sources are fly ash and bottom ash, both of which are by-products of coal combustion in thermal power plants. These ash residues are typically composed of amorphous or semi-crystalline aluminosilicate phases that are reactive under alkaline conditions [

32]. The co-utilization of LFS with fly ash or bottom ash thus represents an effective valorisation strategy that not only addresses multiple waste streams but also yields higher performance and a lower carbon footprint. This multi-waste approach supports the transition toward circular economy practices in construction materials engineering and aligns with global goals for reducing the carbon footprint of the cement and concrete industry. However, often, multi-waste systems continue to rely on commercial, energy-intensive alkali activators (e.g., sodium silicate and hydroxide), which undermines their environmental and economic benefits.

The present study introduces a novel fully waste-based cementitious system that eliminates the need for conventional activators. We formulate one-part eco-cement, mortar, and concrete, composed entirely of industrial residues—ladle furnace slag (LFS) and coal ash (CA)—which are alkali-activated exclusively using different amounts of cement kiln dust (CKD). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the use of CKD as the sole alkaline activator for LFS-based systems. Unlike conventional alkali activation approaches that rely on commercial sodium silicate or hydroxide solutions, this research explores the feasibility of utilizing CKD, a highly alkaline and calcium-rich cement industry residue, as a cost-effective and sustainable alternative activator. The findings offer new insights into resource-efficient binder design and provide a pathway toward the development of circular-economy-compatible alternatives to conventional Portland cement for use in sustainable infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

The main raw material for the preparation of alkali-activated material was ladle furnace slag (LFS). LFS is a by-product of secondary refinement steel, provided by slag processor Aeiforos Bulgaria S.A., Pernik, Bulgaria. The representative sample of LFS was collected from an outside stockpile at a steel plant yard. The LFS was oven-dried to constant mass at 80 °C, then milled in steel ball mill for 1 h.

Coal ash (CA) is composite waste generated at Bulgaria’s largest thermal power plant Maritsa Iztok-2 (1602 MW). The power generation technology involves the combustion of pulverized lignite coal using boilers and steam turbines. The units are equipped with flue gas desulfurization (FGD) systems to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. The power plant generates fly ash (estimated at 1.2–3 million tons/year), bottom ash (approximately 0.12–0.6 million tons/year), and gypsum from FGD (around 0.2–0.5 million tons/year) [

33]. The three waste streams are mixed with water and transported through pipelines into an ash pond. Consequently, the term “coal ash” refers to this combined mixture of fly ash, bottom ash, and FGD gypsum. The CA was oven-dried and milled in a steel ball mill for 1 h.

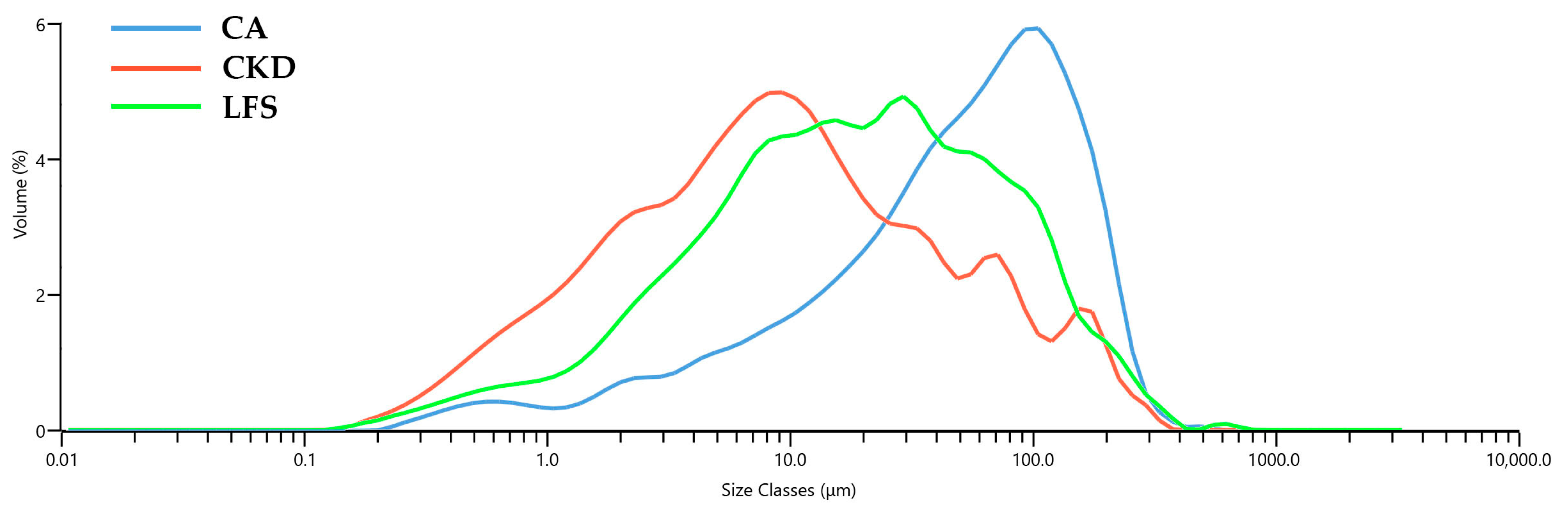

Cement kiln dust (CKD), supplied by Heidelberg Materials Devnya JSC, Devnya, Bulgaria, was used as the dry alkaline activator in this study. Due to its fine particle size and pronounced hygroscopic nature, precautions were taken to prevent premature reactions with atmospheric moisture and carbon dioxide. To preserve its reactivity, the CKD was stored in sealed containers under dry conditions and was used in the mixture as is. A proportion of 90% of the CKD particles were below 102 µm [

26].

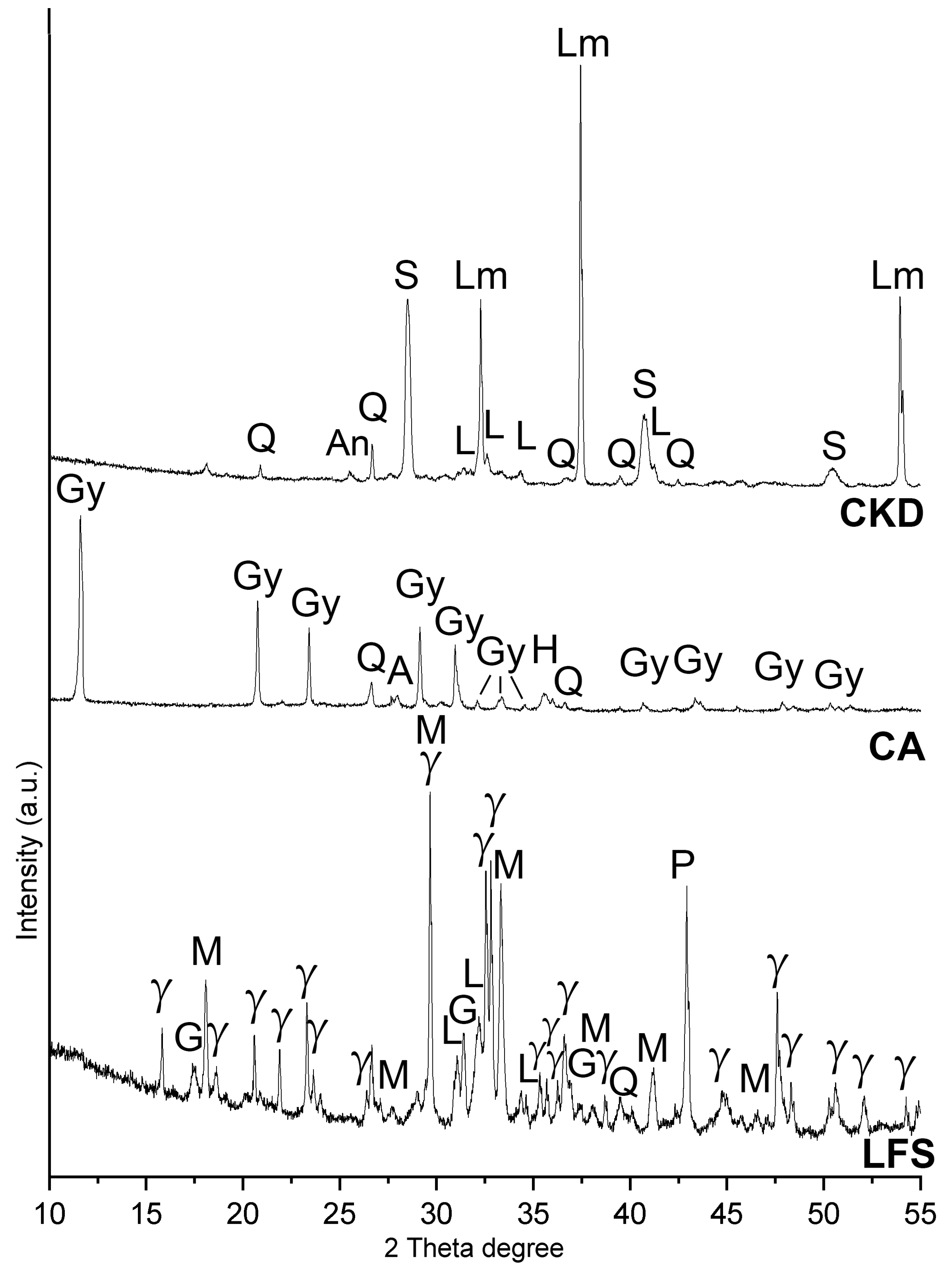

The powdered raw materials are presented at

Figure 1.

The aggregates for mortar and concrete preparation were fractioned electric arc furnace (EAF) slag provided by Aeiforos Bulgaria S.A. EAF slag is a by-product of the steel industry, produced during the melting of iron scrap in electric arc furnaces in steelworks. The slag is poured from the furnace, cooled, and stockpiled. The resulting eco-aggregates were obtained by sieving in accordance with EN 13242:2002 + A1:2007 [

34], ensuring compliance with the standard requirements for aggregates used in civil engineering works and construction.

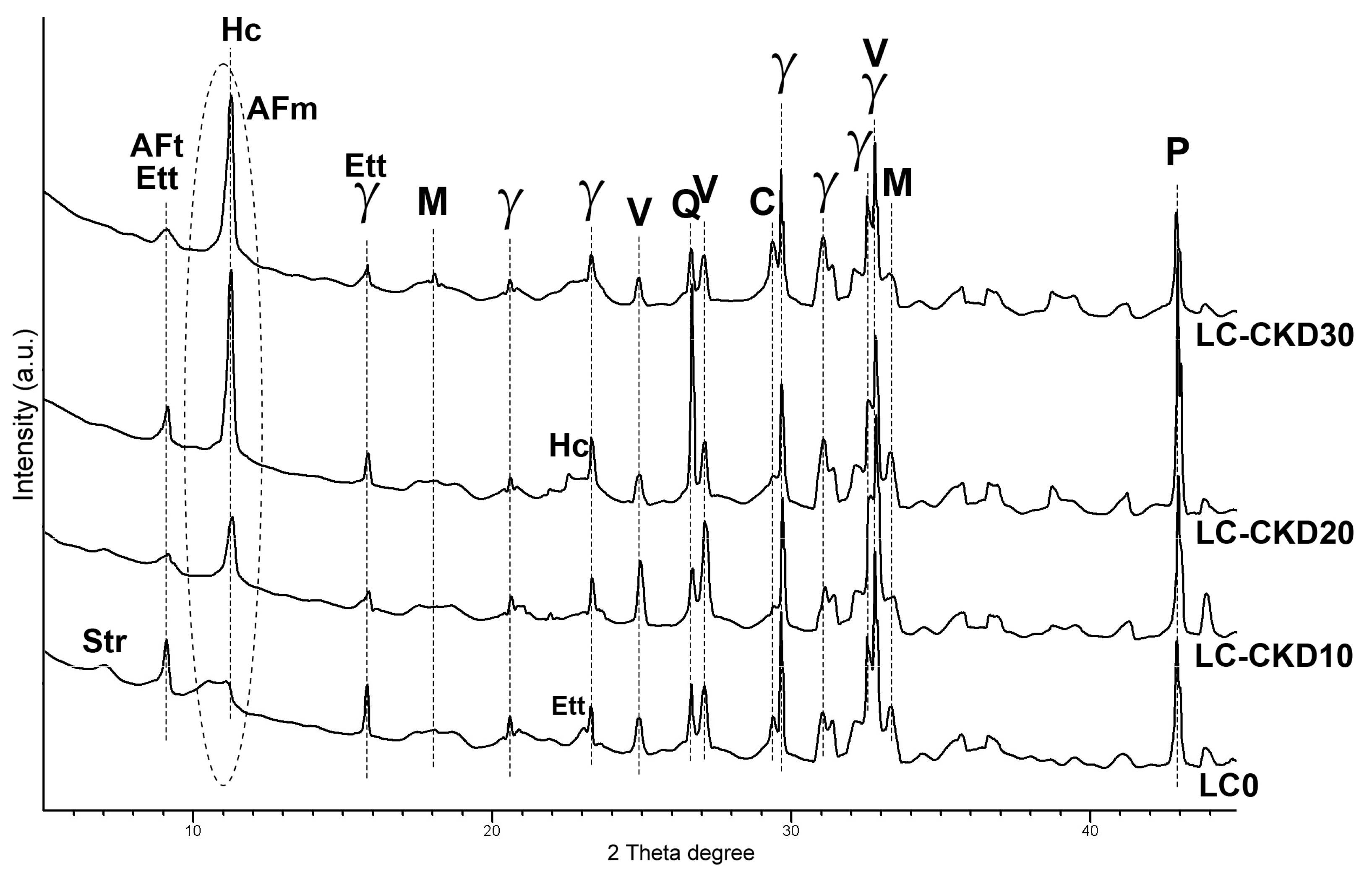

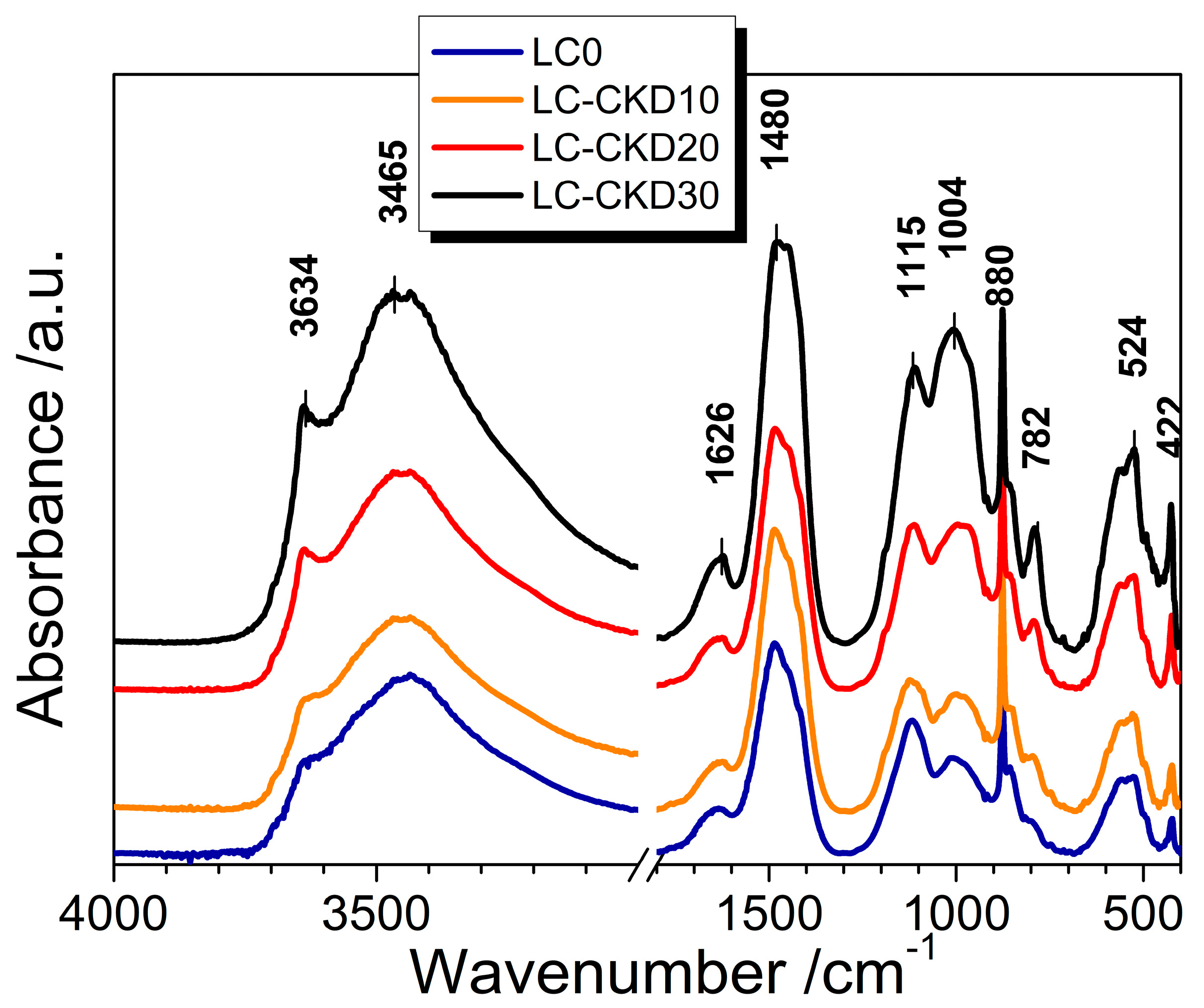

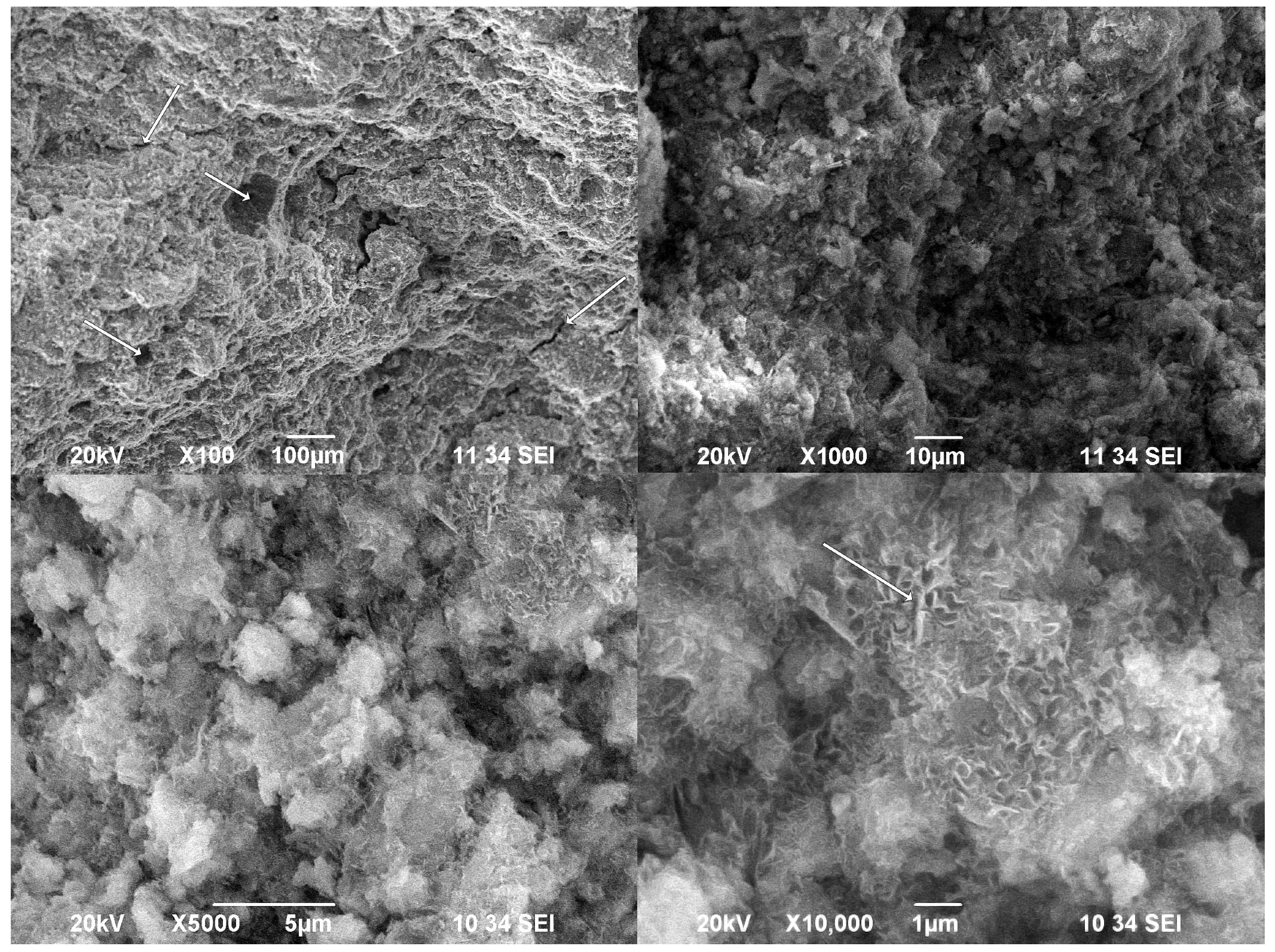

The chemical composition of the precursors was determined by XRF using pressed pellets and analyzed on a Rigaku Supermini 200 WD apparatus, Rigaku Corporation, Osaka, Japan. The powder X-ray diffractograms were obtained on an Empyrean (Malvern-Panalytical, Malvern, UK) diffractometer using CuKα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA. The Infrared spectra were recorded on FT-IR JASCO 4× (Tokyo, Japan) apparatus on 13 mm KBr pellets in the mid-infrared range 4000–400 cm

−1 with the following working parameters: absorption mode, resolution of 2 cm

−1, gain 4×, aperture of 2.5 mm, interferometer scanning speed of 2 mm s

−1, and accumulation of 64 scans for each spectrum. All spectra were manually baseline-corrected. The SEM images were obtained on a JEOL 6390 apparatus (Jeol USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) at 20 kV under a secondary electron regime. The observed specimen was a fracture piece prepared with gold cover under vacuum. The particle size distribution was evaluated by a Mastersizer 3000 (Malvern-Panalytical, Malvern, UK) in dry dispersion mode. The compressive strength was measured as follows: pastes—on 3 cubic specimens with one side area of 10 cm

2; mortar—prisms with dimensions 160 × 40 × 40 mm; concrete—cubes with sides of 70 mm. The absolute density was measured using a gas pycnometer (AccyPy1330, Micromeritic, Norcross, GA, USA) after milling the samples. The Vicat apparatus was used to measure the consistency of the fresh mixtures and setting time, according to EN 196-3:2016 [

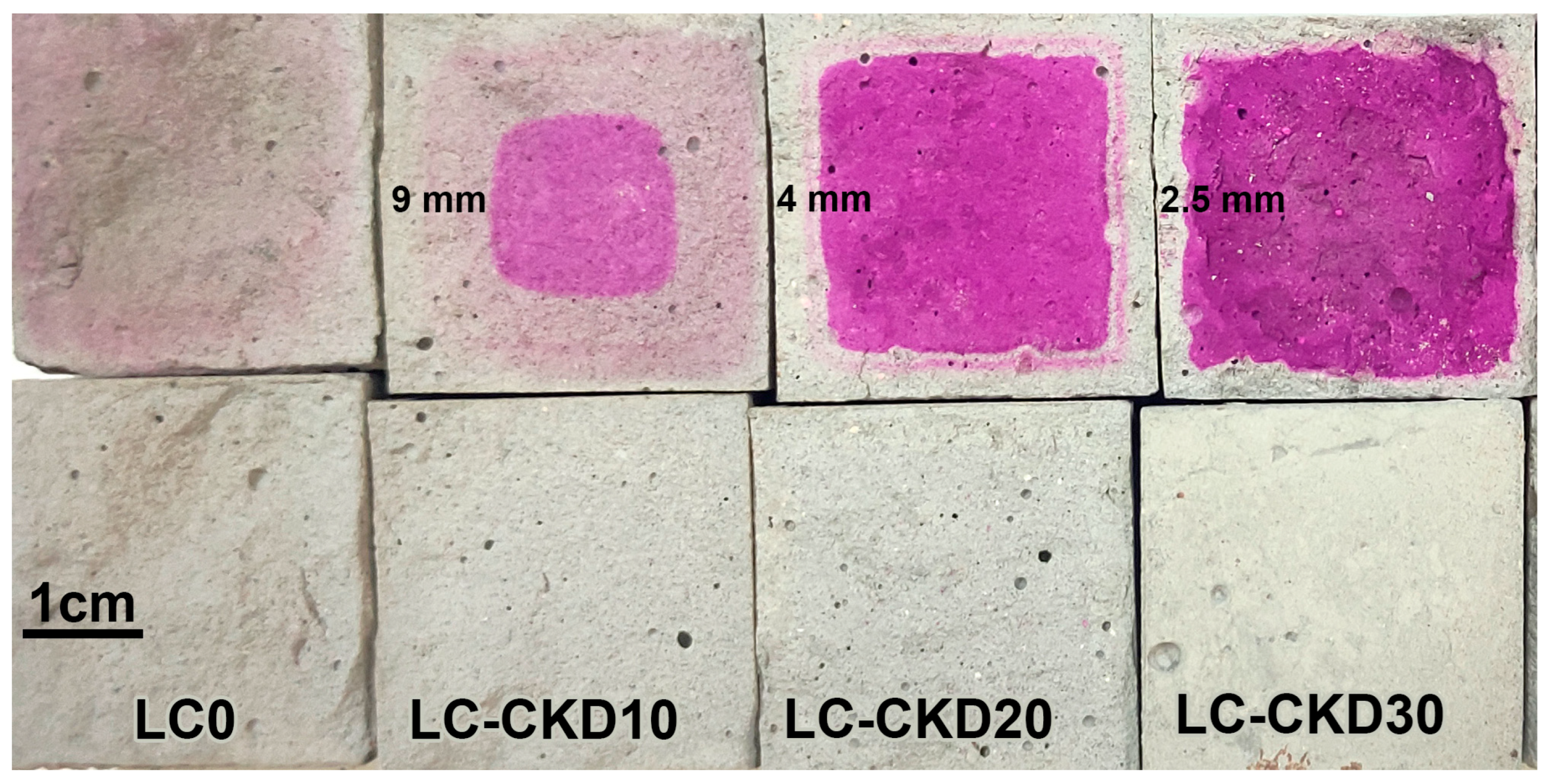

35]. The carbonation depth experiments were performed using a standard solution of phenolphthalein indicator on fresh split specimens, according to EN 14630:2006 [

36].