Experimental Investigation of Metamaterial-Inspired Periodic Foundation Systems with Embedded Piezoelectric Layers for Seismic Vibration Attenuation †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

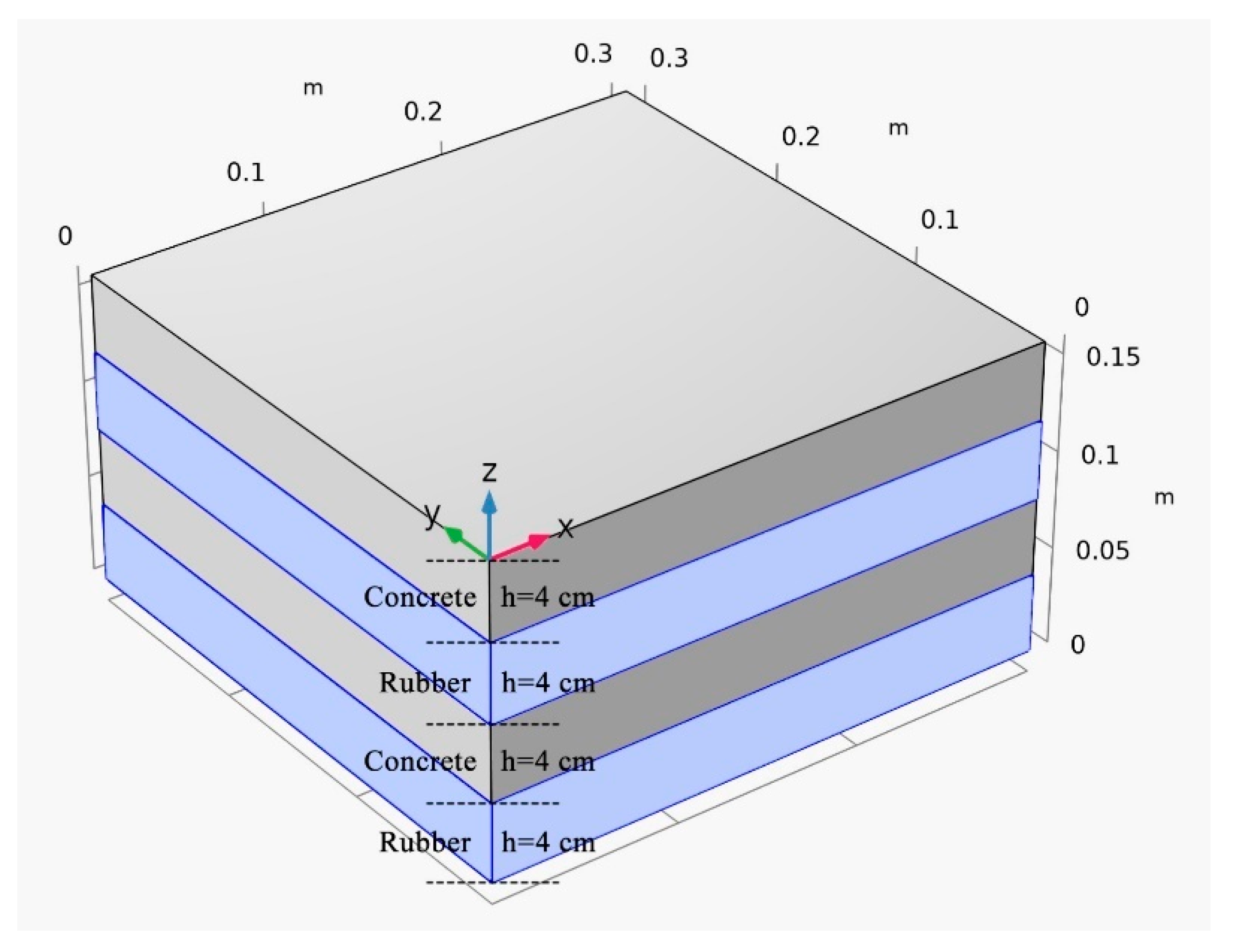

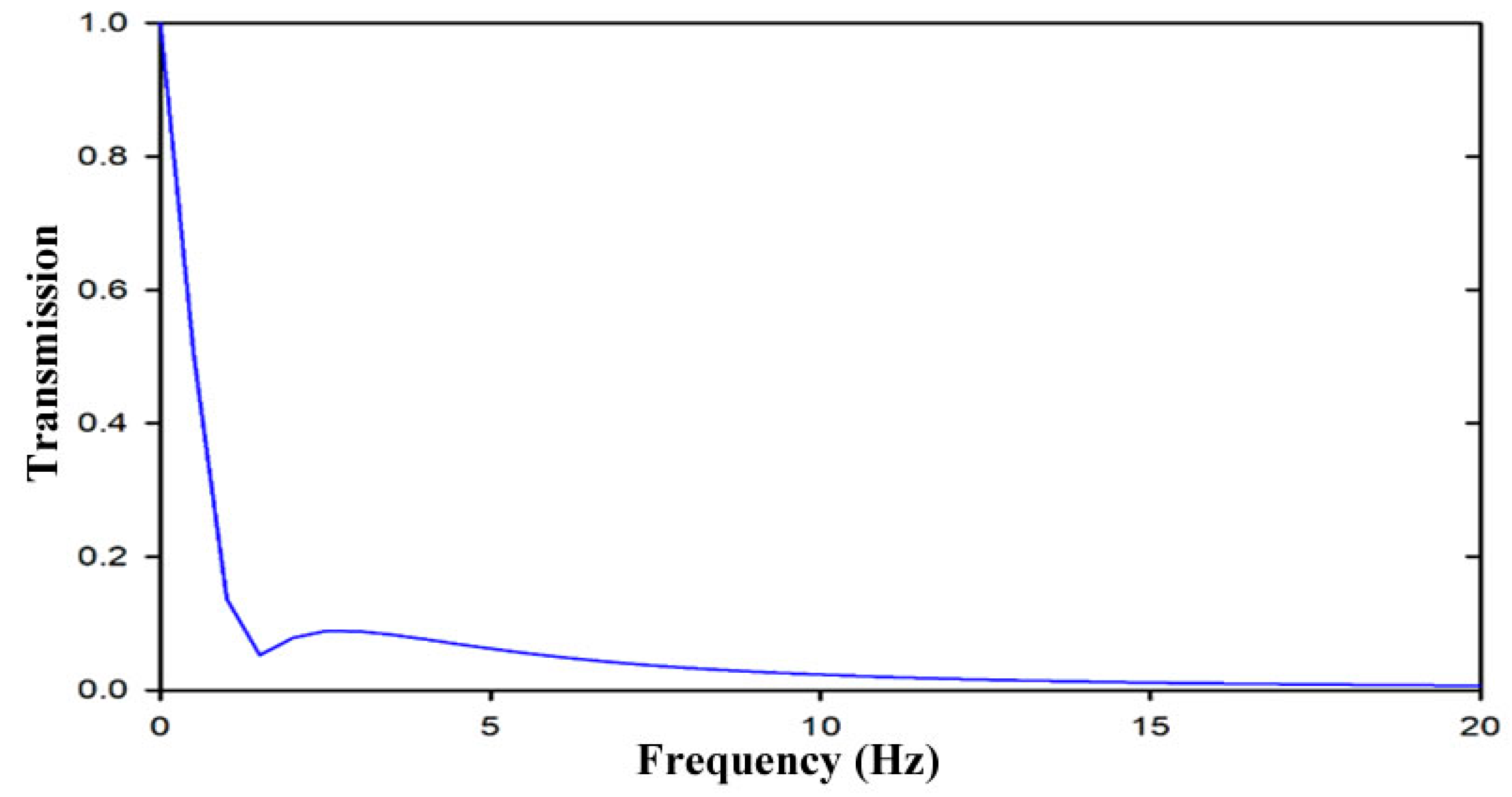

2.1. Phononic Crystal Structure and Modeling

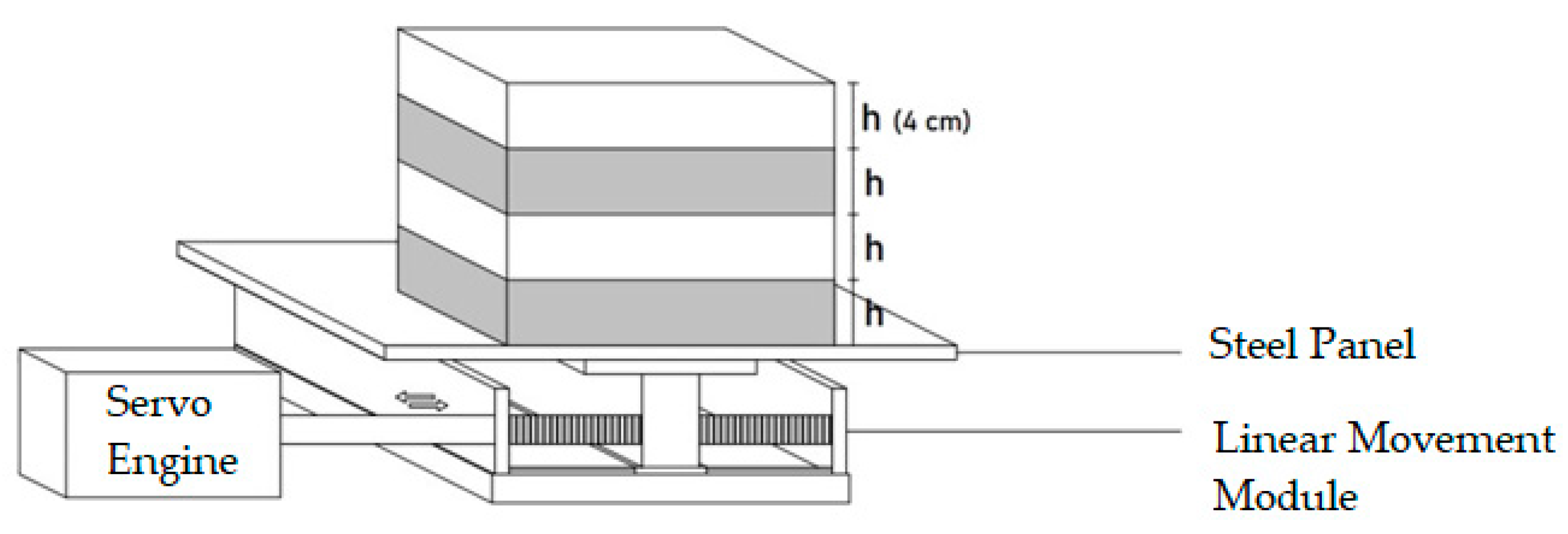

2.2. Shake Table Design

2.3. Preparation of Test Specimens

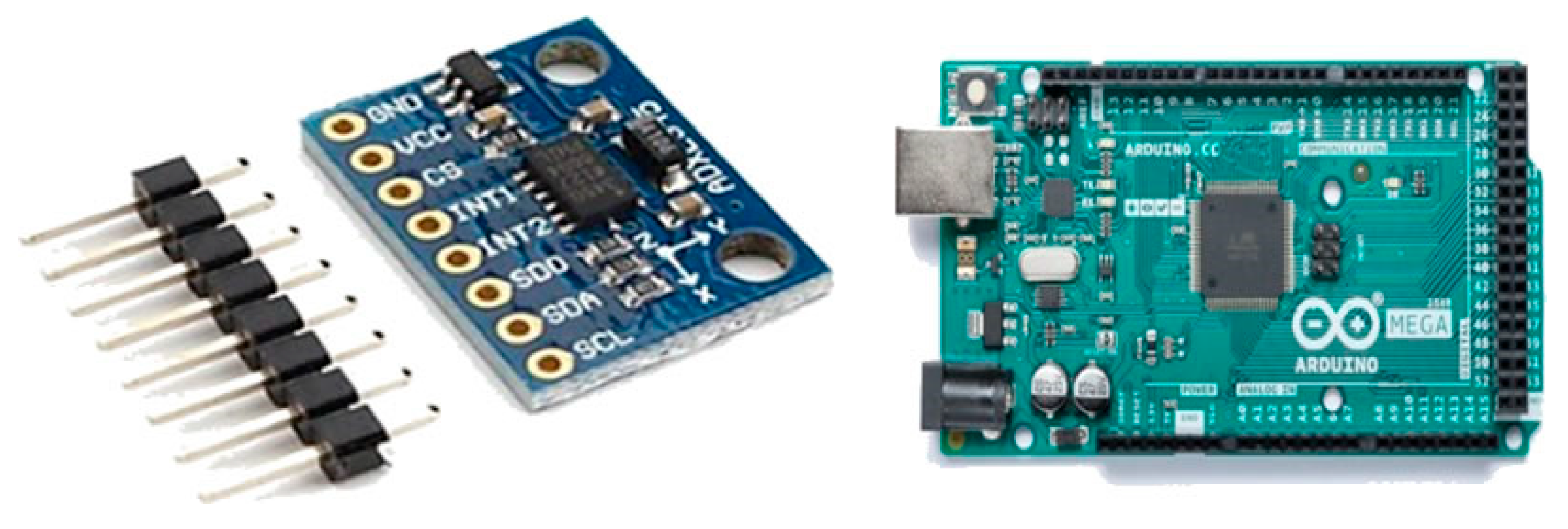

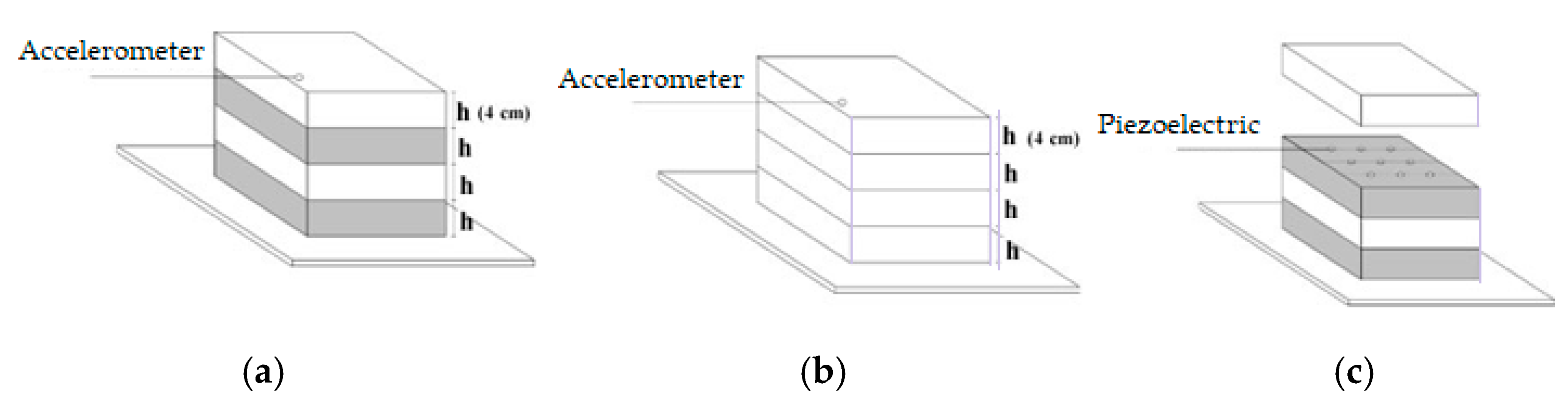

2.4. Experimental Specimen Types and Instrumentation Details

- One-dimensional periodic foundation: A one-dimensional (1D) metamaterial structure composed of alternating rubber and reinforced concrete blocks. This configuration was designed to attenuate vibration energy in the z-direction through frequency band gaps. Compared with the conventional foundation, the 1D periodic structure distributes vibration energy across target frequencies based on metamaterial principles.

- Conventional foundation: A reference configuration consisting solely of a reinforced concrete block, without any isolation layers or metamaterial properties.

- Piezoelectric-integrated 1D foundation (Piezo-1D): A periodic foundation structure integrated with piezoelectric sensors (supplied by a local manufacturer, Istanbul, Türkiye) to provide both vibration attenuation and energy-harvesting capabilities.

3. Experimental Program

3.1. Applied Vibration Protocols

3.2. Assessment Methodology

- Maximum acceleration values;

- Root-mean-square (RMS) values of acceleration;

- Electrical output signals from piezoelectric sensors;

- Frequency spectra obtained via Fourier transform;

- Observed deformation effects under repeated vibrations.

4. Experiment Results

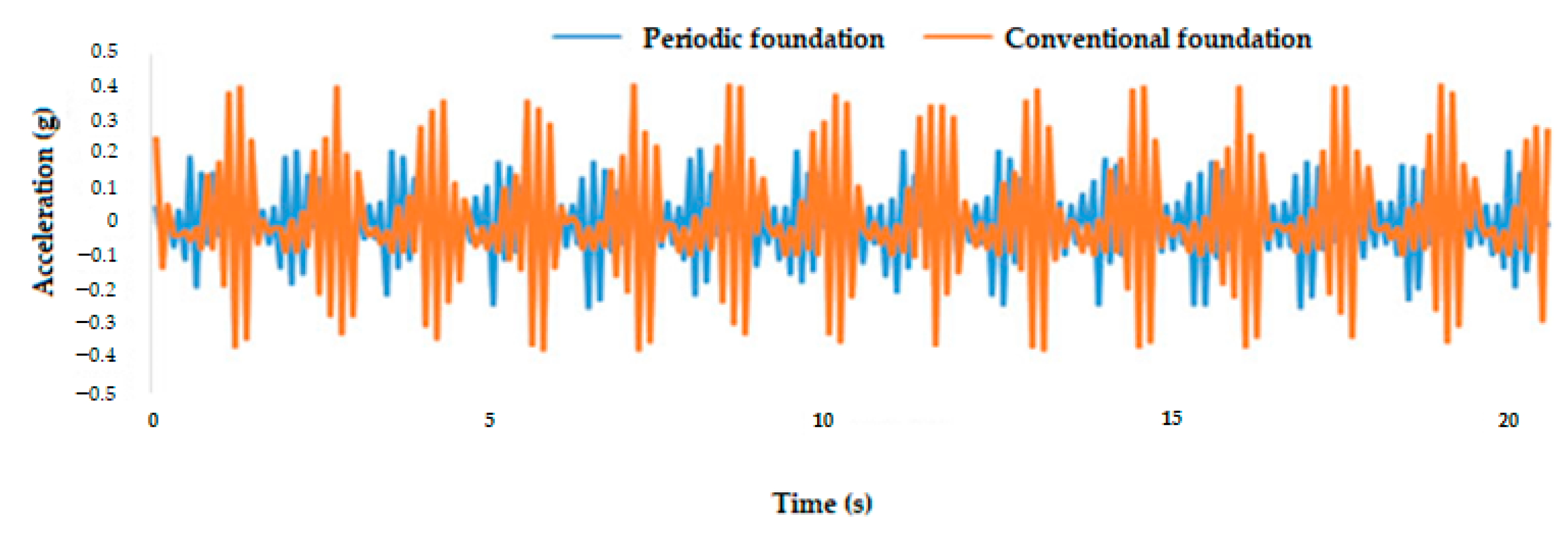

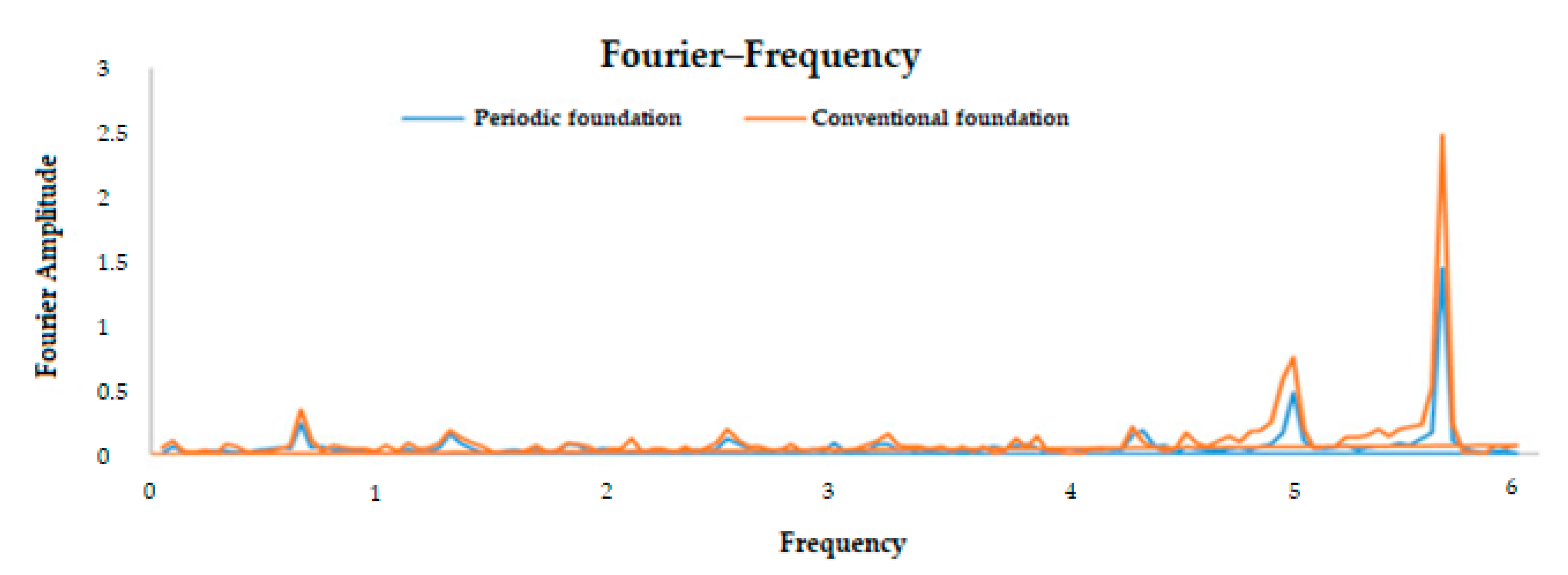

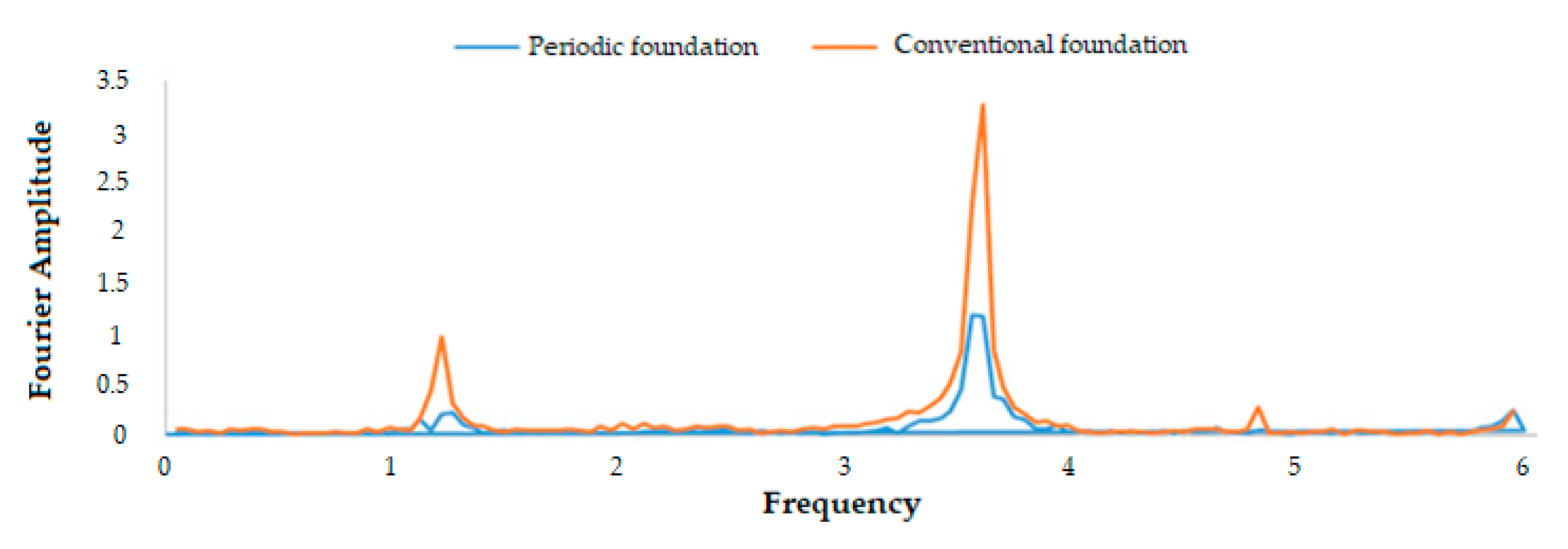

4.1. Results of 4000-Step Vibration Excitation

4.2. Results of 3000-Step Vibration Excitation

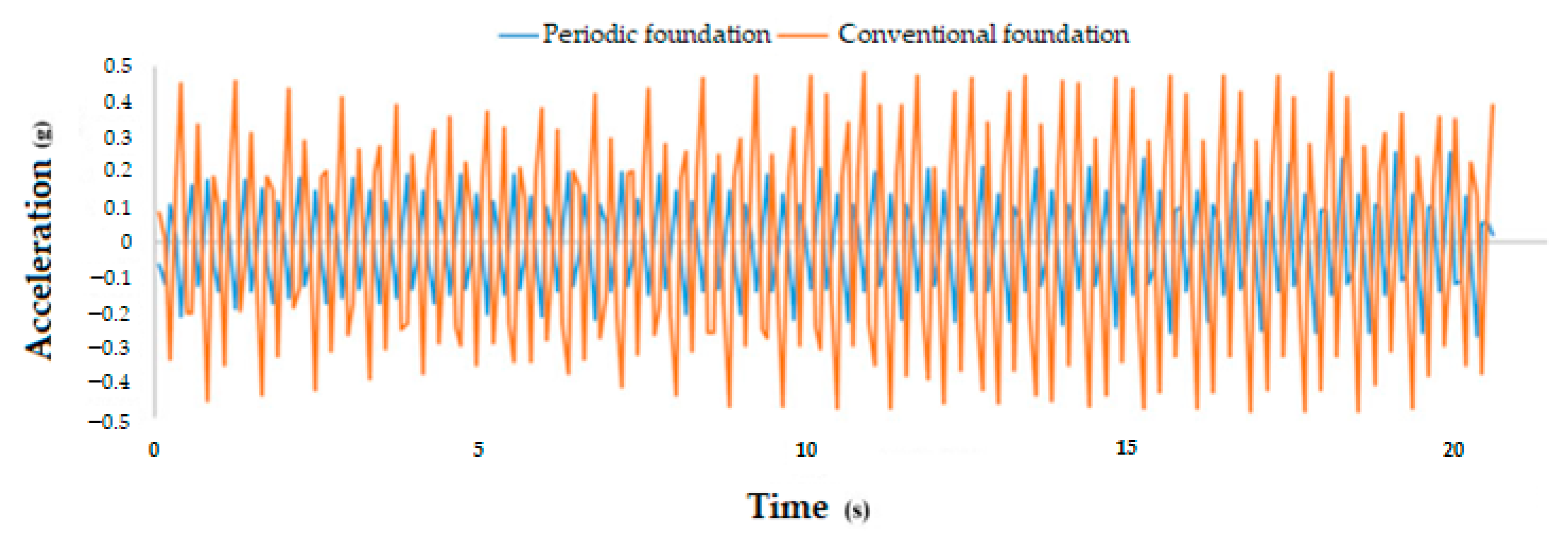

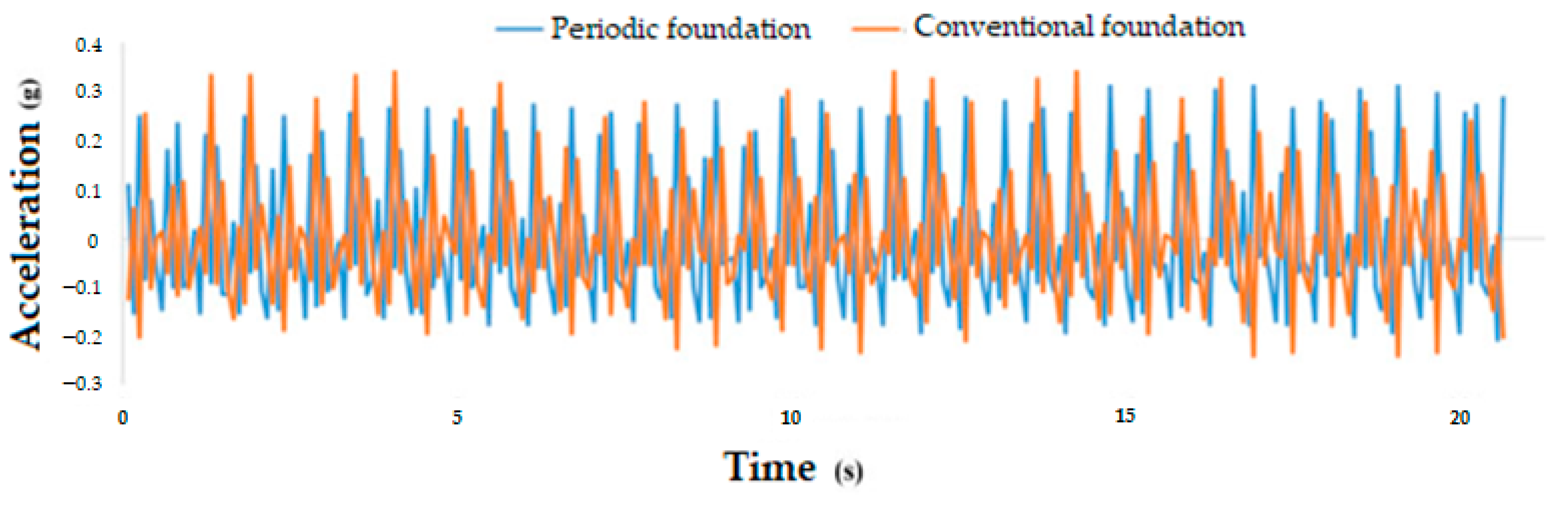

4.3. Results of 5000-Step Vibration Excitation

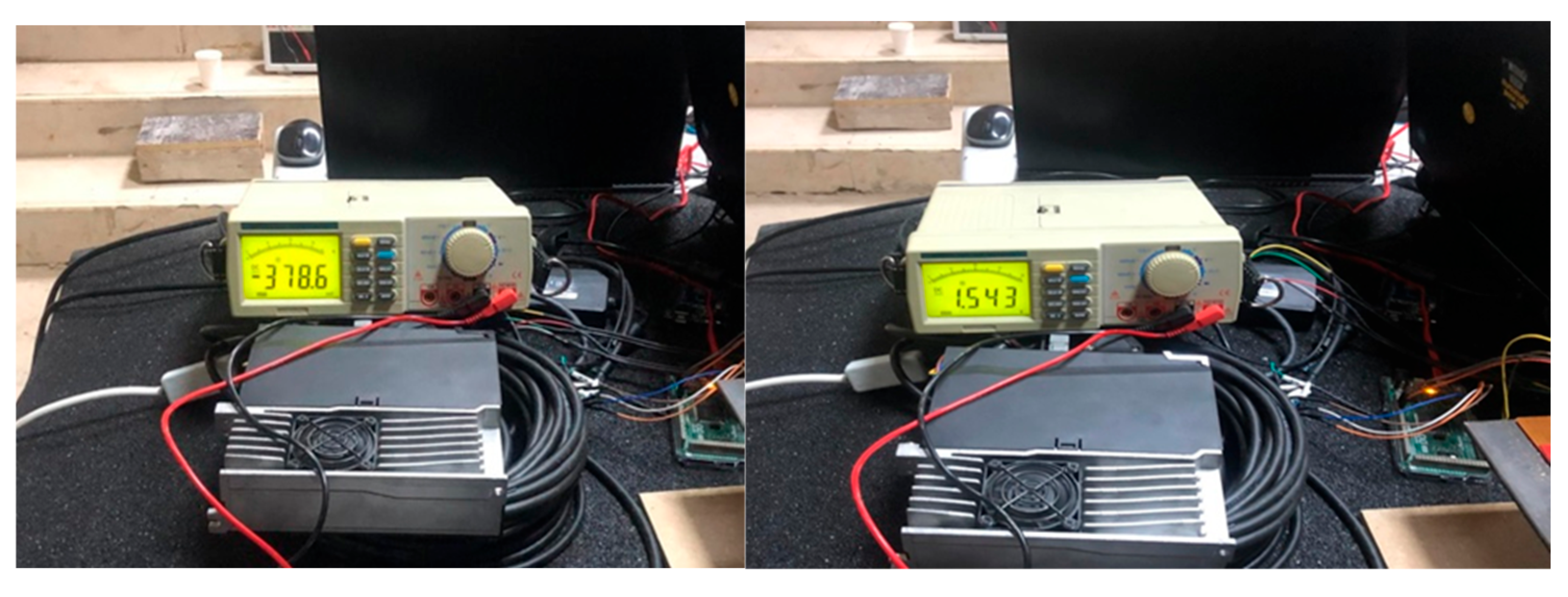

4.3.1. Energy-Harvesting Performance of Piezoelectric Sensors

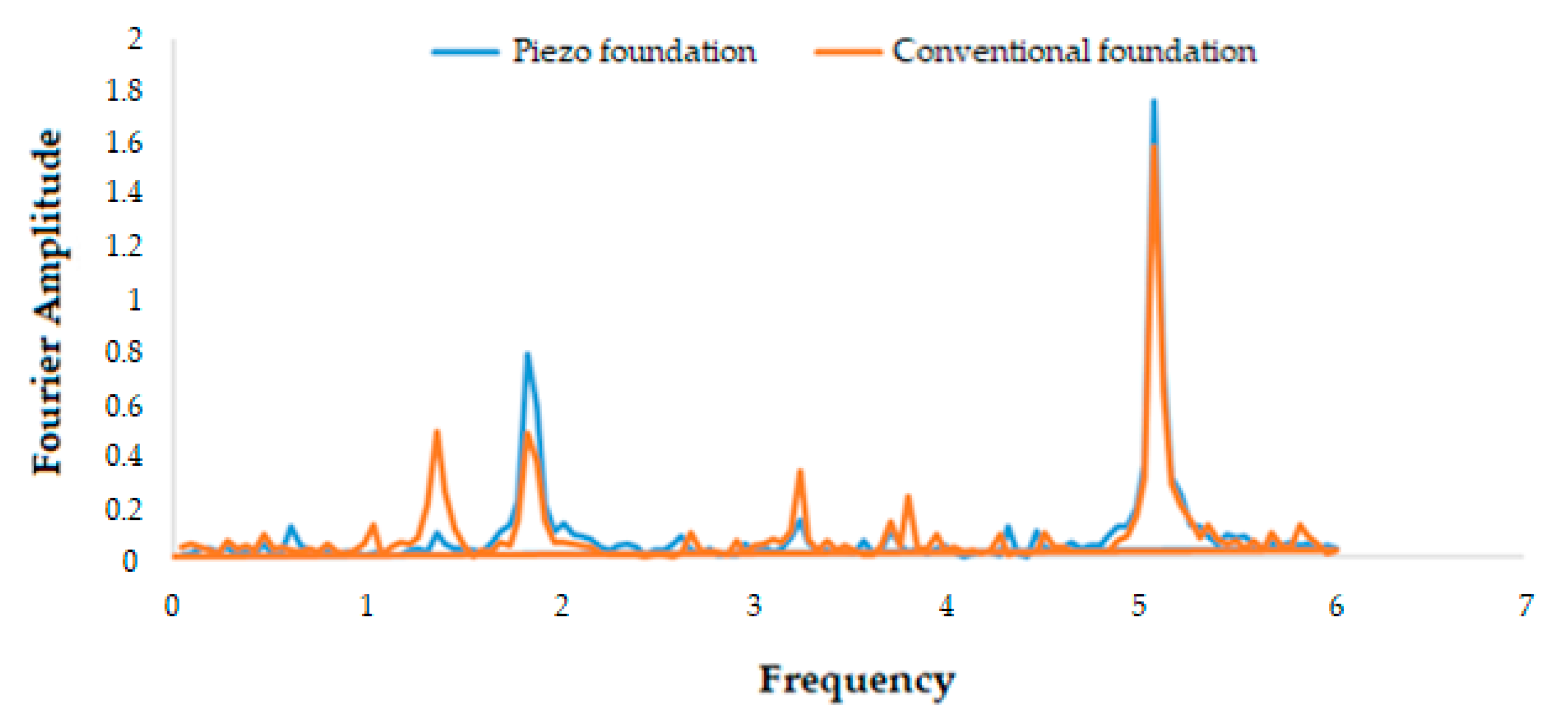

4.3.2. Damping Performance of Piezoelectric-Integrated Periodic Foundation

- Reduce the amplitude of seismic-induced accelerations transmitted to the structure;

- Create frequency band gaps at low-frequency ranges relevant to earthquake engineering;

- Generate measurable electrical energy under vibration.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turkish Building Earthquake Code; Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change of the Republic of Türkiye: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/03/20180318M1-2-1.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025). (In Turkish)

- Bao, J.; Shi, Z.; Xiang, H. Dynamic responses of a structure with periodic foundations. J. Eng. Mech. 2012, 138, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelif, A.; Adibi, A. Phononic Crystals; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, M.S.; Halevi, P.; Dobrzynski, L.; Djafari-Rouhani, B. Acoustic band structure of periodic elastic composites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigalas, M.M.; Economou, E.N. Elastic and acoustic wave band structure. J. Sound Vib. 1992, 158, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, H.-W.; Yu, G.-L.; Cheng, L. Achieving ultra-broadband and ultra-low-frequency surface wave bandgaps in seismic metamaterials through topology optimization. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295, 115863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, A.; Roux, P.; Guenneau, S.; Gueguen, P.; Craster, R.V. Forests as a natural seismic metamaterial: Rayleigh wave bandgaps induced by local resonances. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Espinosa, F.M.; Jimenez, E.; Torres, M. Ultrasonic band gap in a periodic two-dimensional composite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Shi, Z. A new seismic isolation system and its feasibility study. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2010, 9, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achaoui, Y.; Ungureanu, B.; Enoch, S.; Brûlé, S.; Guenneau, S. Seismic waves damping with arrays of inertial resonators. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2016, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achaoui, Y.; Antonakakis, T.; Brûlé, S.; Craster, R.V.; Enoch, S.; Guenneau, S. Clamped seismic metamaterials: Ultra-low frequency stop bands. New J. Phys. 2017, 19, 063022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brûlé, S.; Javelaud, E.H.; Enoch, S.; Guenneau, S. Experiments on seismic metamaterials: Molding surface waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 133901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, E.; Fırat, S.; Beyhan, G.; Çankaya, İ.; Vural, İ.; Kırtel, O. Field experiments on wave propagation and vibration isolation by using wave barriers. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2009, 29, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Shi, Z. Application of periodic theory to rows of piles for horizontal vibration attenuation. Int. J. Geomech. 2013, 13, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniaci, M.; Krushynska, A.; Bosia, F.; Pugno, N.M. Large-scale mechanical metamaterials as seismic shields. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 083041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Shi, Z. Periodic pile barriers for Rayleigh wave isolation in a poroelastic half-space. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 121, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, G.; Lim, C.W. Artificially engineered metaconcrete with wide bandgap for seismic surface-wave manipulation. Eng. Struct. 2023, 276, 115375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.; Shi, Z.; Meng, Q.; Lim, C.W. A novel buried periodic in-filled pipe barrier for Rayleigh wave attenuation: Numerical simulation, experiment and applications. Eng. Struct. 2023, 297, 116971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Ren, F.; Li, S.; Tian, S.; Li, Y.; Mo, J. A study on low-frequency vibration mitigation by using the metamaterial-tailored composite concrete-filled steel tube column. Eng. Struct. 2024, 305, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, M.F.; Kumbasaroglu, A.; Yalciner, H.; Babacan, Y.; Korozlu, N.; Cimilli Catir, F.E. Investigation of Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Structures Insulated with Seismic Meta-Materials in Earthquake Engineering. In Proceedings of the International Yıldırım Bayezid Scientific Research and Innovation Symposium (IYBSRIS 2025), Bursa, Türkiye, 9–10 May 2025; Bursa Technical University: Bursa, Türkiye, 2025; Volume 2, pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Casablanca, O.; Ventura, G.; Garesci, F.; Azzerboni, B.; Chiaia, B.; Chiappini, M.; Finocchio, G. Seismic isolation of buildings using composite foundations based on metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 174903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Laskar, A.; Cheng, Z.; Menq, F.; Tang, Y.; Mo, Y.L.; Shi, Z. Seismic isolation of two-dimensional periodic foundations. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 044908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Menq, F.; Mo, Y.L.; Tang, Y.; Shi, Z. Three-dimensional periodic foundations for base seismic isolation. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 075006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witarto, W.; Wang, S.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Nie, X.; Mo, Y.L.; Chang, K.C.; Tang, Y.; Kassawara, R. Seismic isolation of small modular reactors using metamaterials. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 045307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witarto, W.; Wang, S.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Wang, J.; Mo, Y.L.; Chang, K.C.; Tang, Y. Three-dimensional periodic materials as seismic base isolators for nuclear infrastructure. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 045014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.J.; Shi, Z.F.; Wang, S.J.; Mo, Y.L. Periodic materials-based vibration attenuation in layered foundations: Experimental validation. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y. Phononic crystals containing piezoelectric material. Solid State Commun. 2004, 130, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.Y.; Chen, Q.; Liang, B.; Cheng, J.C. Control of the elastic wave bandgaps in two-dimensional piezoelectric periodicstructures. Smart Mater. Struct. 2007, 17, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damcı, E.; Şekerci, Ç. Development of a low-cost single-axis shake table based on Arduino. Exp. Tech. 2019, 43, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.A.I.E.; Syam, R.; Renreng, I.; Harianto, T.; Wibowo, N.R. The development of earthquake simulator. EPI Int. J. Eng. 2021, 4, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M. Performance Evaluation of ARI-I Shake Table. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Institute of Science and Technology, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11527/13906 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- TS EN 12390-2; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 2: Making and Curing Test Specimens. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Türkiye, 2019.

| (A) Technical Specifications of Control and Sensor Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Brand/Model | Technical Specifications | Connection Type/Protocol |

| Microcontroller Card | Arduino Mega 2560 | 54 digital I/O, 16 analog input, 256 KB Flash, 16 MHz operating frequency | USB, UART |

| data | data | data | |

| Vibration Sensor (Accelerometer) Piezoelectric Sensor | ADXL345 - | 3-axis, ±16 g measurement range, digital output, 13-bit resolution 3.3/5 V reading range, analog signal output | I2C/SPI Positive/negative/electrode |

| Motor Driver Board | (LZ100) | Position, speed, and torque control mode; overspeed, overload, etc., protection mode; 5-LED digital display; PWM supported | PWM/Digital |

| Servo Motor | (80LZ750) | Metal gear, 180° rotation angle, 0.75 kW, torque: 2.39 Nm, 5000 rpm | PWM |

| (B) Performance Parameters of the Vibration System | |||

| Parameter | Value/Range | Explanation | |

| Working Direction | Single axis (X-direction) | Horizontal movement only | |

| Maximum Displacement | Approx. 7.5 cm | Measured from the table center | |

| Burden Capacity | ~80 kg | System load limit, including test specimen | |

| Table Dimensions | 40 cm × 40 cm | Manufactured from ST35 steel | |

| Measurement Resolution | 13-bit (ADXL345 sensor) | Digital data generation on each axis | |

| Control Software | Arduino IDE-based (Version 2.3.4) | Frequency/amplitude control via user interface | |

| Concrete | Rubber | |

|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 2.400 | 915 |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 24.392 | 0.15 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Property | Value/Description |

|---|---|

| Disc diameter | 35 mm |

| Placement range | 10 cm |

| Number of layers | 2 rubber plates (top and bottom) |

| Number of sensors | 9 sensors × 2 layers = 18 |

| Parameter | 1D Periodic Foundation | Conventional Foundation | Piezo Periodic Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse width | 5 µs | 5 µs | 5 µs |

| Motor step count | 3000/4000 | 3000/4000/5000 | 5000 |

| Assessment parameter | Acceleration (g) | Acceleration (g) | Acceleration (g) |

| Parameter | 1D periodic foundation | Conventional foundation | Piezo periodic foundation |

| System | Maximum Acceleration (g) | RMS Acceleration (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic foundation | 0.25069 | 0.11227 |

| Conventional foundation | 0.40576 | 0.19682 |

| System | Maximum Acceleration (g) | RMS Acceleration (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic Foundation | 0.26707 | 0.13044 |

| Conventional Foundation | 0.4836 | 0.30265 |

| System | Maximum Acceleration (g) | RMS Acceleration (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic Foundation | 0.31278 | 0.15644 |

| Conventional Foundation | 0.34991 | 0.14197 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oz, M.F.; Kumbasaroglu, A.; Yalciner, H.; Korozlu, N.; Babacan, Y.; Çatır, F.E.C.; Sayarcan, D. Experimental Investigation of Metamaterial-Inspired Periodic Foundation Systems with Embedded Piezoelectric Layers for Seismic Vibration Attenuation. Buildings 2025, 15, 4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244399

Oz MF, Kumbasaroglu A, Yalciner H, Korozlu N, Babacan Y, Çatır FEC, Sayarcan D. Experimental Investigation of Metamaterial-Inspired Periodic Foundation Systems with Embedded Piezoelectric Layers for Seismic Vibration Attenuation. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244399

Chicago/Turabian StyleOz, Mehmet Furkan, Atila Kumbasaroglu, Hakan Yalciner, Nurettin Korozlu, Yunus Babacan, Fulya Esra Cimilli Çatır, and Done Sayarcan. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of Metamaterial-Inspired Periodic Foundation Systems with Embedded Piezoelectric Layers for Seismic Vibration Attenuation" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244399

APA StyleOz, M. F., Kumbasaroglu, A., Yalciner, H., Korozlu, N., Babacan, Y., Çatır, F. E. C., & Sayarcan, D. (2025). Experimental Investigation of Metamaterial-Inspired Periodic Foundation Systems with Embedded Piezoelectric Layers for Seismic Vibration Attenuation. Buildings, 15(24), 4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244399