Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Vertically Uniform Loaded Strip Foundations near Slopes Considering Heterogeneity, Anisotropy, and Intermediate Principal Stress Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Definitions and Basic Theories

2.1. Unified Strength Theory (UST)

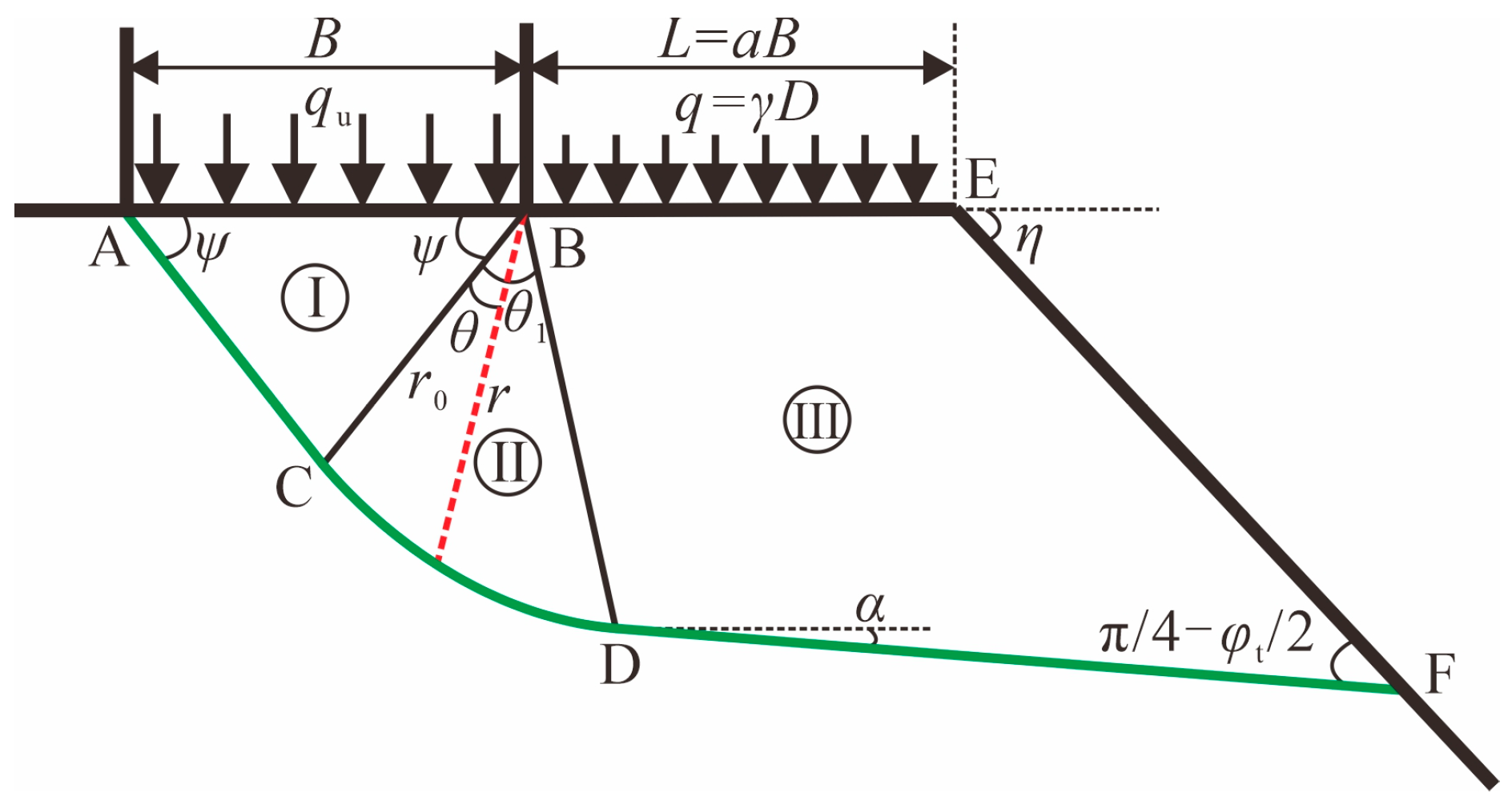

2.2. Assumptions of the Failure Mode

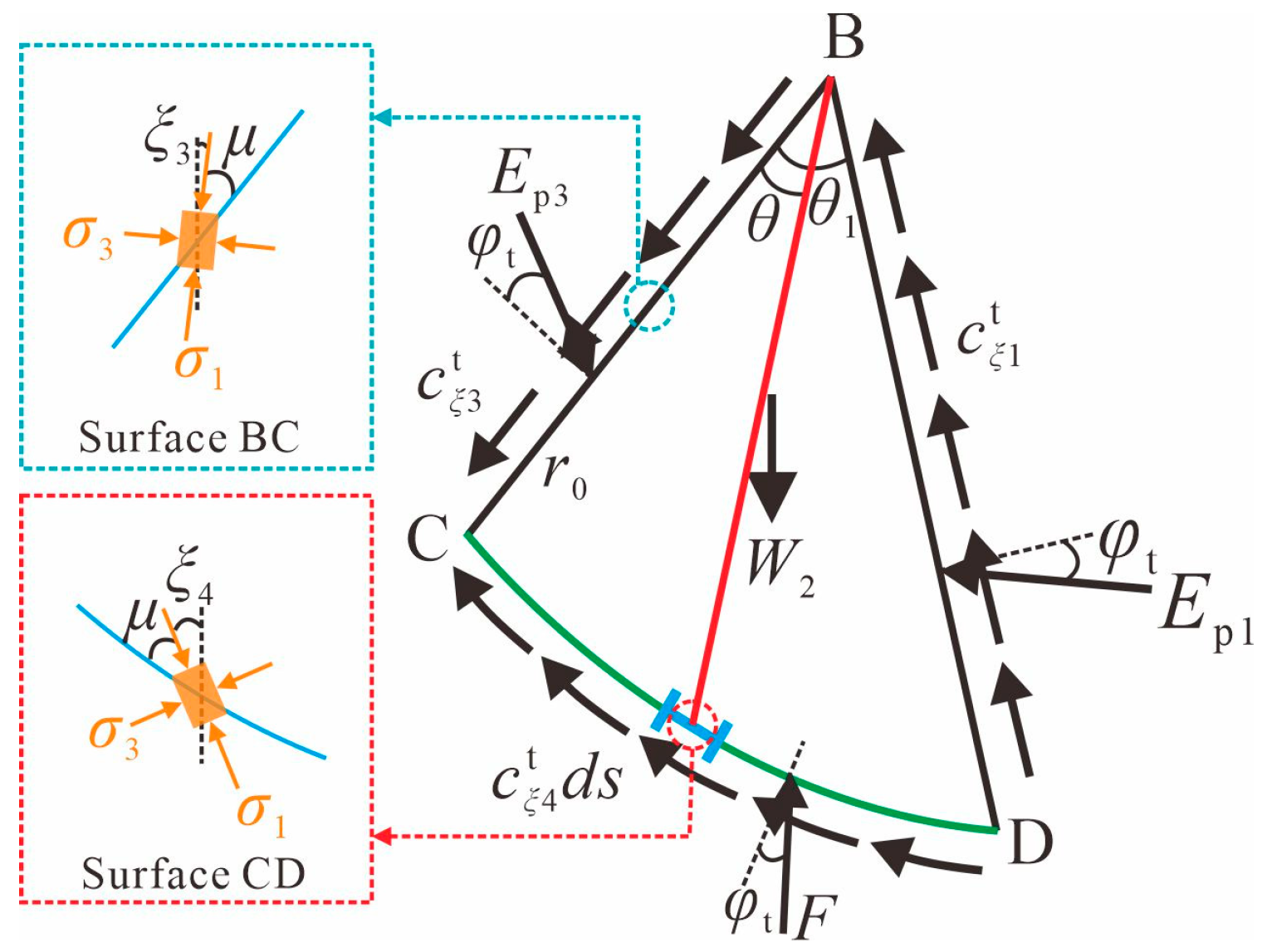

- The foundation soil experiences general shear failure, forming a continuous sliding surface ACDF. The soil within the sliding zone is in a state of plastic limit equilibrium and is governed by the unified shear strength formula under plane strain conditions (i.e., Equation (4)). The shear strength of the foundation’s lateral soil is neglected, and an equivalent uniformly distributed surcharge q = γD is used as a substitute.

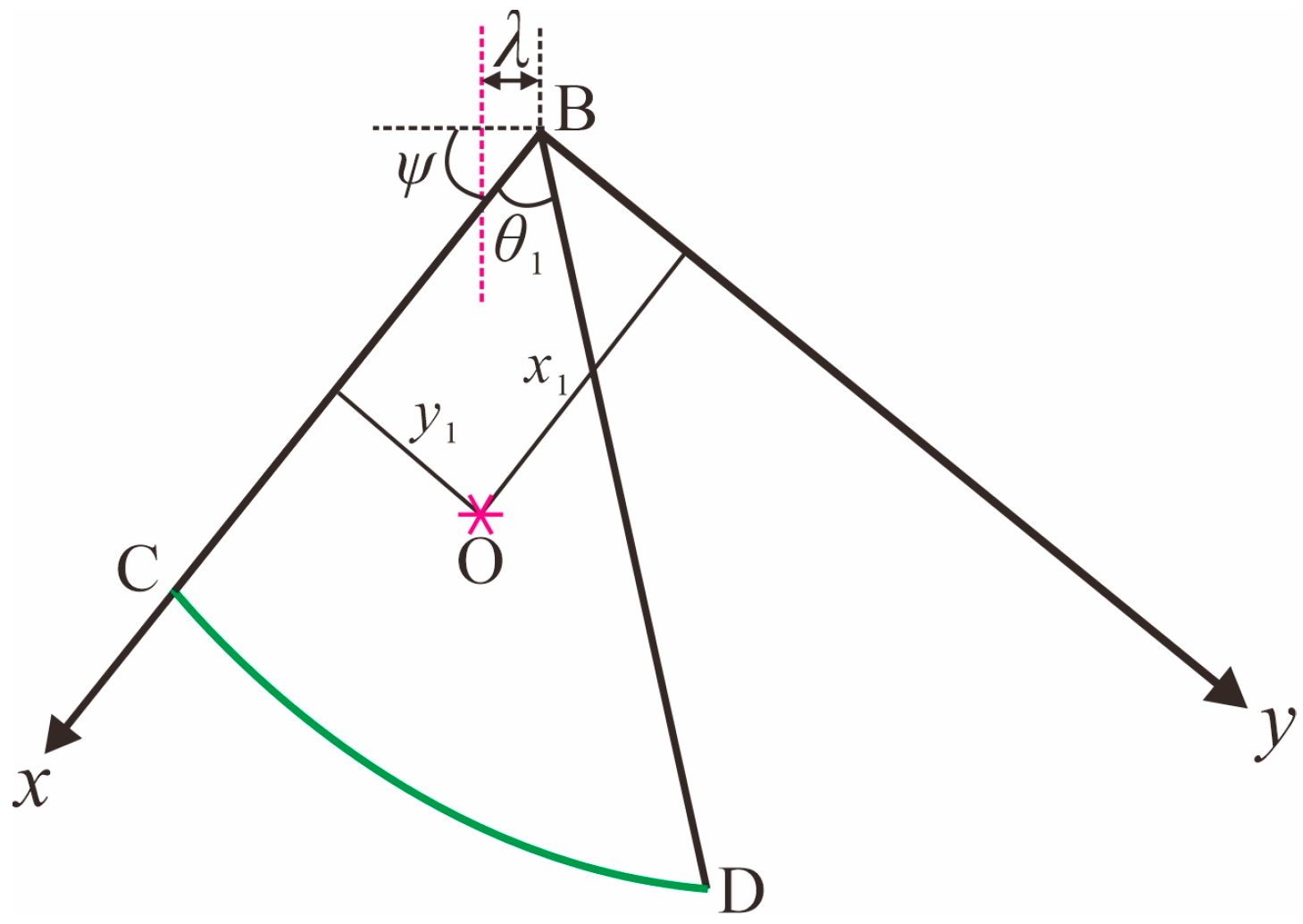

- The soil on the side near the slope fails first, while the soil on the opposite side of the foundation, although subjected to the same forces, does not experience sliding. It is assumed that Region I forms a symmetrical triangular elastic wedge, where the angle ψ between surfaces BC and AB depends on the roughness of the base. When the base is completely rough, ψ = φt. When the base is completely smooth, ψ = π/4 + φt/2.

- Region II is the transitional shear zone, where surface CD follows a logarithmic spiral equation with a top angle θ1. Region III is the passive failure zone, where the angle between surface DF and the slope surface EF is π/4 − φt/2. If the angle between the radius r of any point on the logarithmic spiral CD and the initial radius r0 is θ, then r0 and r can be expressed as:

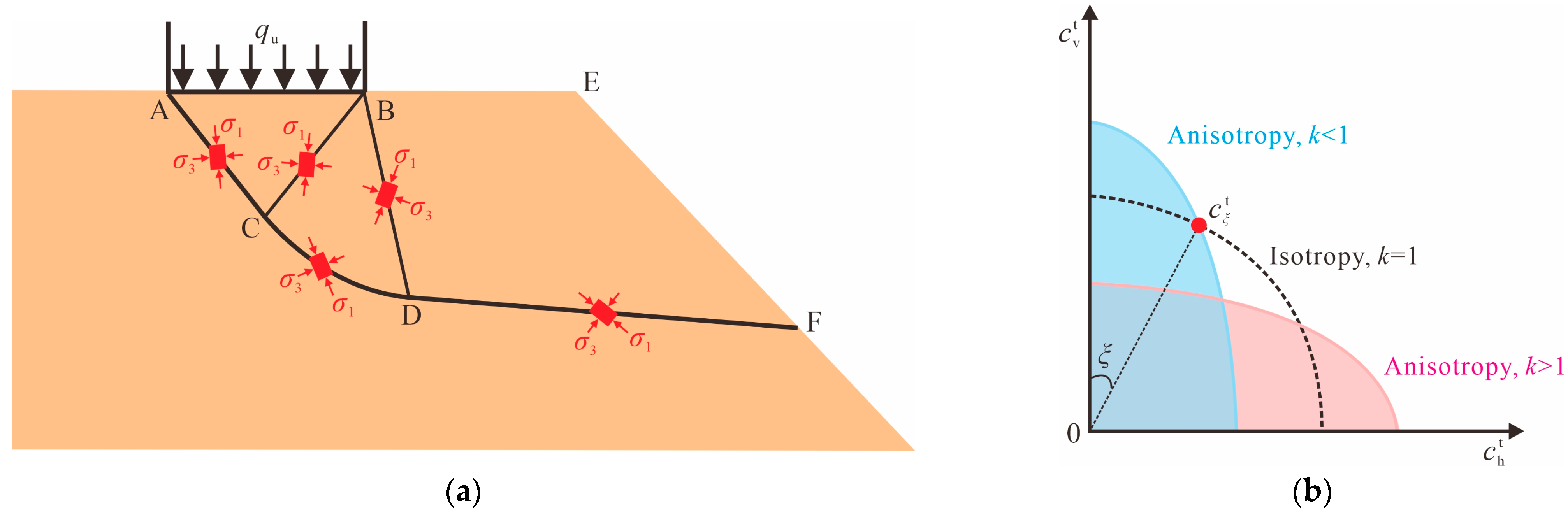

2.3. Heterogeneity and Anisotropy of Soil Strength

2.3.1. Characteristics of Soil Strength Heterogeneity and Computational Models

2.3.2. Characteristics of Soil Strength Anisotropy and Computational Models

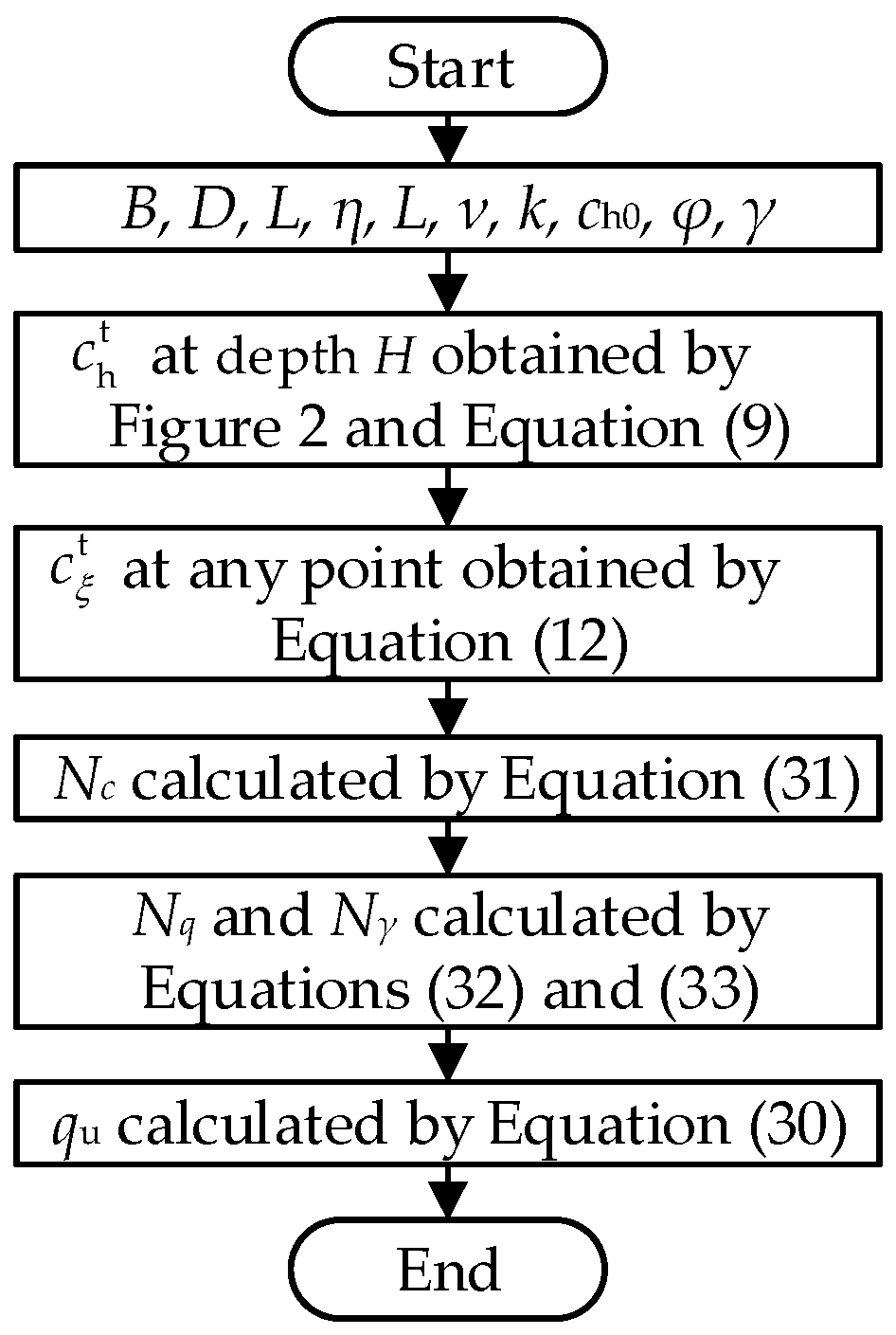

3. Analytical Solution of Ultimate Bearing Capacity for Foundations near Slopes

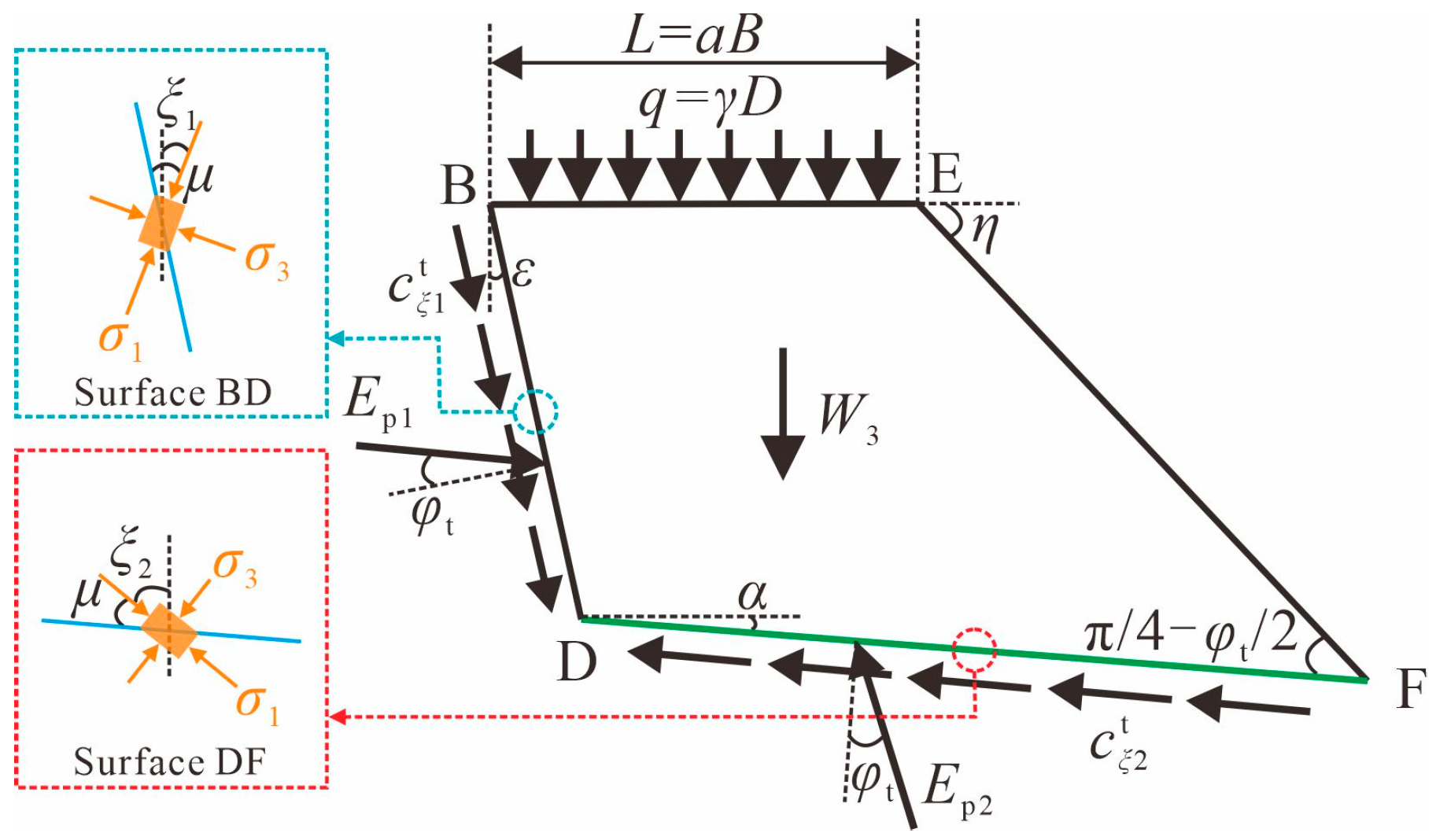

3.1. Derivation of Formula

3.2. Theoretical Degeneration Analysis

4. Comparisons and Validations

4.1. Comparisons with Results of Theoretical Solutions

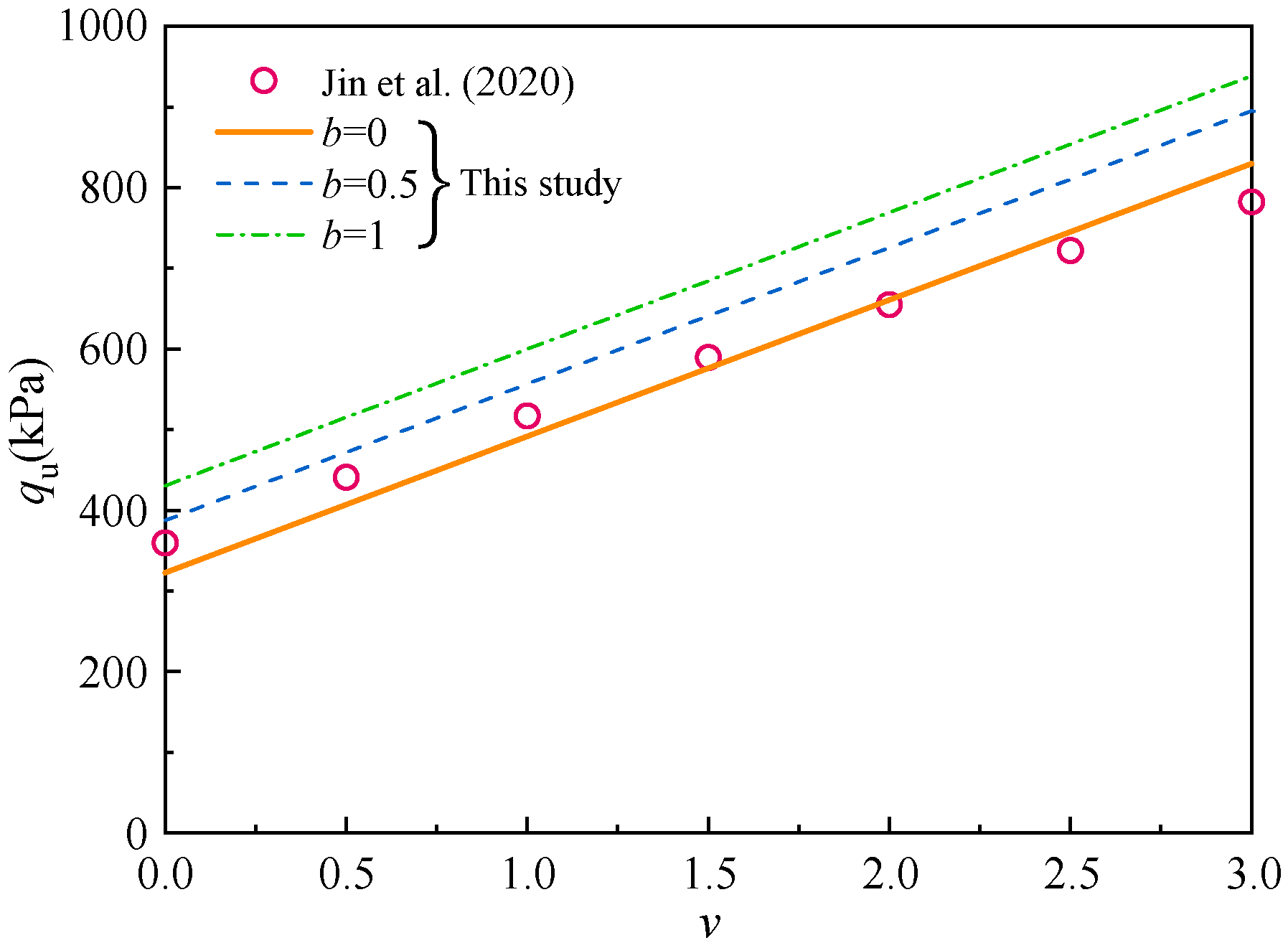

4.1.1. A Comparison with the Result of Jin et al. [4]

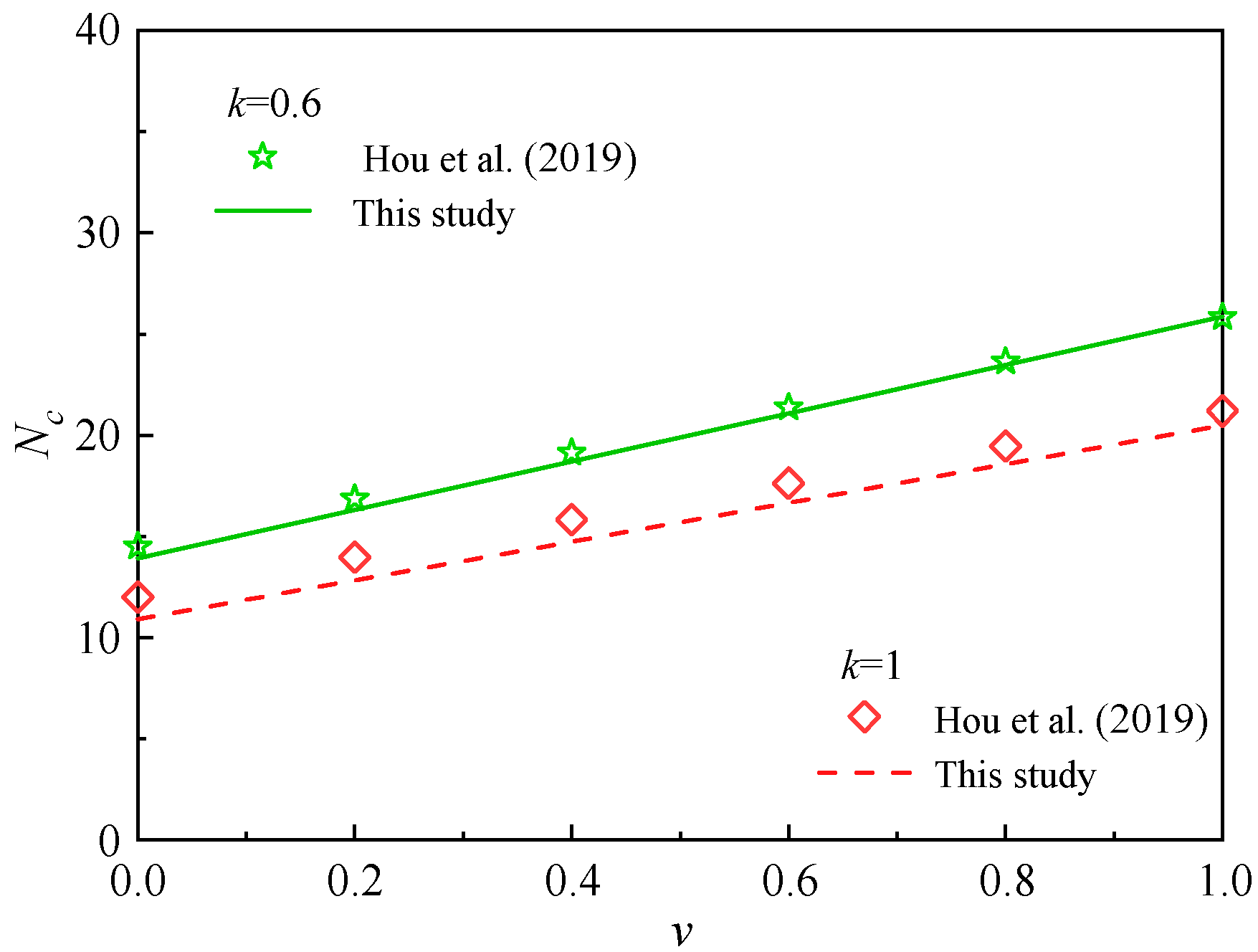

4.1.2. A Comparison with the Result of Hou et al. [40]

4.2. Comparison with Results of Model Tests

4.2.1. A Comparison with the Result of Keskin and Laman [41]

4.2.2. A Comparison with the Results of Castelli and Lentini [42]

4.3. Comparisons with Results of Numerical Simulations

5. Parametric Sensitivity Analysis

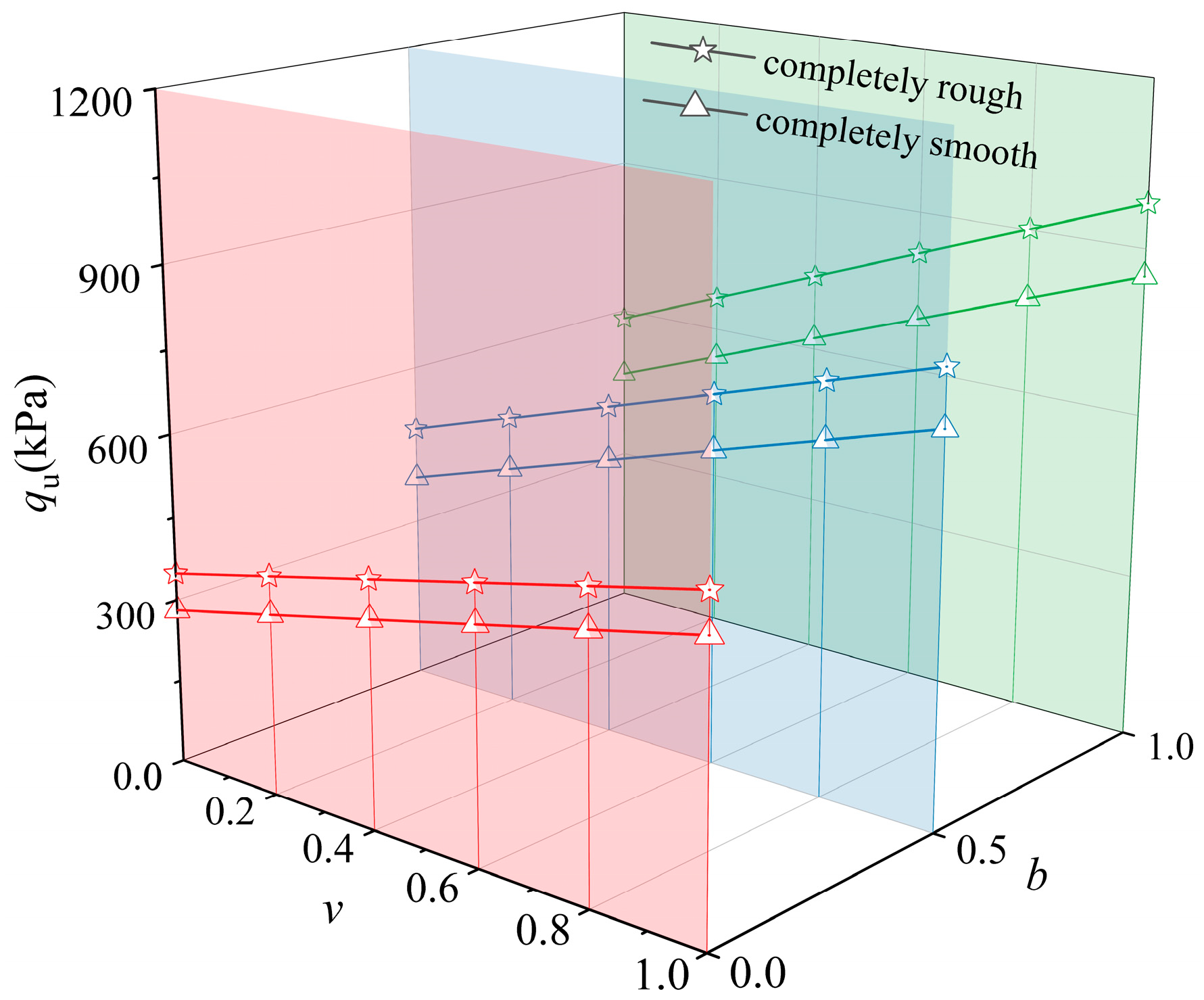

5.1. Effect of Intermediate Principal Stress

5.2. Effect of Soil Heterogeneity

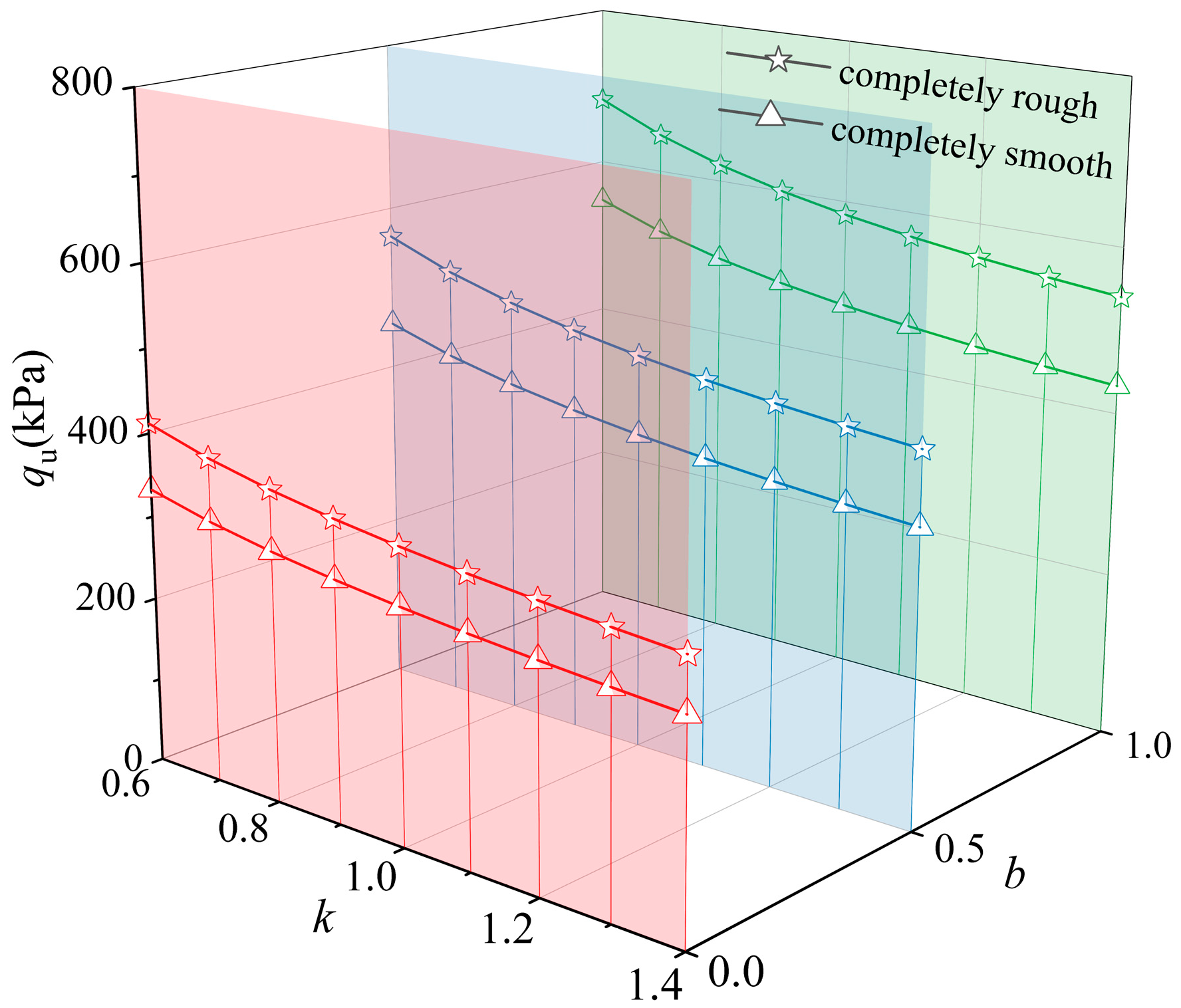

5.3. Effect of Soil Anisotropy

6. Discussions

6.1. Interpretation of Results

6.2. Limitations and Future Works

- (1)

- The parameter b plays a key role in controlling the influence of the intermediate principal stress, and its accurate determination typically relies on a series of triaxial tests. Although this study conducted a sensitivity analysis of the parameter b, a comprehensive uncertainty quantification has not yet been performed. Future research could address this limitation by introducing probabilistic or stochastic approaches. For example, Monte Carlo sampling could be employed to propagate the uncertainty of b within the analytical framework and quantitatively evaluate its effect on bearing capacity predictions.

- (2)

- The model idealizes the soil as a single-layer continuous medium with cohesion varying linearly with depth and a constant internal friction angle, thereby simplifying the natural stratification and nonlinear characteristics of real soils. Nonlinear cohesion–depth relationships, such as exponential or power-law formulations, may be introduced to more accurately describe the actual strength distribution. In addition, a piecewise heterogeneity model could be employed to extend the current theory to natural slope–foundation systems consisting of alternating layers of clay, sand, and silt.

- (3)

- The present study assumes a single-sided slip surface. Although this assumption simplifies the analysis, the adopted single-sided limit equilibrium mode represents an idealized approximation. In reality, complex slope–foundation interactions may involve multiple failure mechanisms, such as progressive failure or compound slip surfaces. Future work could integrate the analytical model based on the UST with upper-bound kinematic analysis or variational approaches to explore multiple potential failure modes and identify the most critical mechanism under specific boundary conditions.

- (4)

- The current model neglects time-dependent behaviors such as creep, consolidation, and cyclic loading, which are particularly relevant to the long-term performance evaluation of soft clays and silty soils. Future studies could incorporate viscoplastic constitutive relations or effective stress evolution equations into the UST framework to account for such time-dependent effects (e.g., creep, consolidation, and stress relaxation) and to enable the design of foundations near slopes under sustained or cyclic loading conditions.

- (5)

- The present analysis is based on rigid–plastic solid theory and the classical slip-line field method, without accounting for strain hardening, dilatancy, or warping effects. An important future direction is to relax the rigid–plastic assumption by incorporating elasto-plastic constitutive models that include strain hardening, dilatancy, and structural evolution. Within the UST framework, the use of incremental plasticity theory or non-associated flow rules could provide a more realistic representation of pre-failure deformation and post-failure response.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A unified analytical expression is derived for the single-sided limit equilibrium failure mode under a uniformly distributed surface load, where both heterogeneity and anisotropy are introduced explicitly into the unified shear strength formula under plane strain conditions. Unlike previous approaches based on the Mohr–Coulomb failure criteria, the present model accommodates multiple strength theories through a unified parameter b, representing the intermediate principal stress effect. This generalization allows existing classical solutions (such as the homogeneous, isotropic cases by Yan et al. [33]) to emerge as special cases, thus providing a comprehensive and theoretically consistent foundation for slope–foundation interaction analysis.

- (2)

- The proposed solution demonstrates high accuracy when validated against results from model tests, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.96 and a maximum deviation of only 6.2%. The results of this study are in good agreement with both theoretical solutions and numerical simulations, exhibiting a maximum discrepancy of only 5.9%. This confirms the model’s capability to capture realistic soil behavior while maintaining analytical simplicity and computational efficiency. Furthermore, this study reveals that the ultimate bearing capacity of foundations adjacent to slopes is significantly influenced by the intermediate principal stress effect, neglecting this effect leads to an approximately 64.5–67.9% underestimation.

- (3)

- The heterogeneity coefficient is found to enhance the ultimate bearing capacity adjacent to slopes by approximately 67.9–83.4%, reflecting the strengthening of deeper soil layers due to cohesion variation with depth. Conversely, an increase in the anisotropy coefficient leads to an approximately 20.8–22.3% decrease in the ultimate bearing capacity, attributed to the decrease in vertical cohesion along the sliding surface caused by anisotropy. These quantitative results confirm that coupled effects of intermediate principal stress effects, heterogeneity, and anisotropy in bearing capacity analysis. The resulting closed-form expressions enable rapid yet reliable evaluation of bearing capacity for design optimization in heterogeneous, anisotropic soil environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| b | intermediate principal stress parameter of the UST | — |

| γ | unit weight of soil | kN/m3 |

| φ | internal friction angle | degrees |

| ch0 | cohesion in the horizontal direction at the ground surface | kPa |

| χ | gradient coefficient | kN/m3 |

| H | depth of the calculation points | m |

| unified cohesion in the horizontal direction at depth H | kPa | |

| unified cohesion at any point | kPa | |

| k | anisotropy coefficient | — |

| ν | heterogeneity coefficient | — |

| B | width of the foundation | m |

| D | burial depth of the foundation | m |

| η | slope angle | degrees |

| L | horizontal distance from the foundation to the slope crest | m |

| λ | horizontal distance from the centroid of Isolator II to point B | m |

| θ1 | top angle of surface CD | degrees |

| μ | angle between σ1 and the inclination of the failure surface | degrees |

| ε | angle between surface BD and the vertical direction | degrees |

| α | angle between surface DF and the horizontal direction | degrees |

| ξ1 | angle between σ1 and the vertical direction on surface BD | degrees |

| ξ2 | angle between σ1 and the vertical direction on surface DF | degrees |

| ξ3 | angle between σ1 and the vertical direction on surface BC | degrees |

| ξ4 | angle between σ1 and the vertical direction on surface CD | degrees |

| S1 | area of Isolator I | m2 |

| S2 | area of Isolator II | m2 |

| S3 | area of Isolator III | m2 |

| ψ | angle between surfaces BC and AB | degrees |

| Nc | bearing capacity factor for cohesion | — |

| Nq | bearing capacity factor for surcharge | — |

| Nγ | bearing capacity factor for unit weight | — |

| qu | ultimate bearing capacity of the foundation | kPa |

Appendix A.3

References

- Cao, W.; Li, W.; Yi, H.; Liu, Y. Probability Analysis of Undrained Clay Slope Stability Considering Strength Anisotropy and Heterogeneous Rotated Anisotropy. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1581457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Dias, D.; Yang, X. Analysis of Earth Pressure for Shallow Square Tunnels in Anisotropic and Non-Homogeneous Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 104, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, M.; Shao, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Su, T.; Mei, X. Dynamic Response Research of Dangerous Rockfall Impact Protection Structures. Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 2025, 19, 1563–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Q. The Use of Improved Radial Movement Optimization to Calculate the Ultimate Bearing Capacity of a Nonhomogeneous Clay Foundation Adjacent to Slopes. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 118, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, L.; El Naggar, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Wu, W. A Novel Theoretical Model of Heterogeneous Soil-Pile Interaction for Investigating the Torsionally Loaded Pile. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 139, 115833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, M. Theoretical Solution for Drained Cylindrical Cavity Expansion in Sands Incorporating Fabric Anisotropy Using the SANISAND-F Model. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 186, 107380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yao, Y.-P.; Liu, H.; Liu, F. The ACUH Model: A Unified Hardening Constitutive Model for Anisotropically Consolidated Loess Considering Intermediate Principal Stress Effects. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 54, 101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Chen, J.X.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.Y. Probabilistic Analysis of Offshore Single Pile Composite Foundation Considering Rotated Anisotropy Spatial Variability of Multi-Layered Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 182, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zou, J.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, T. Three-Dimensional Seismic Bearing Capacity Assessment of Heterogeneous and Anisotropic Slopes. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Peng, Z. Stability Analyses of Shallow Rectangular Tunnels in Anisotropic and Nonhomogeneous Soils Using a Kinematic Approach. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04024127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Liu, J. Seismic Active Earth Pressure in Nonhomogeneous and Anisotropic Soils. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 170, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, K.; Chakraborty, D. Probabilistic Bearing Capacity of Strip Footing on Reinforced Soil Slope. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 116, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, N.; Ouahab, M.Y.; Mabrouki, A.; Benmeddour, D.; Mellas, M. Probabilistic Analysis of the Bearing Capacity of Inclined Loaded Strip Footings near Cohesive Slopes. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 15, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, X.; Yin, Z. Seismic Bearing Capacity of Rectangular Foundations near Slopes Using the Upper Bound Method. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 182, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Tang, H. Calculating the Bearing Capacity of Foundations near Slopes Based on the Limit Equilibrium and Limit Analysis Methods. Buildings 2025, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, H. Assessment of Undrained Bearing Capacity of Foundations on Anisotropic Clay Slope under Inclined Load. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan Kalourazi, A.; Jamshidi Chenari, R.; Veiskarami, M. Bearing Capacity of Strip Footings Adjacent to Anisotropic Slopes Using the Lower Bound Finite Element Method. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04020213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghsheno, H.; Arabani, M. Seismic Bearing Capacity of Shallow Foundations Placed on an Anisotropic and Nonhomogeneous Inclined Ground. Indian Geotech. J. 2021, 51, 1319–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, X. The Deformation and Failure of Strip Footings on Anisotropic Cohesionless Sloping Grounds. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2021, 45, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, L.; Gutierrez, M. Influence of the Intermediate Principal Stress and Principal Stress Direction on the Mechanical Behavior of Cohesionless Soils Using the Discrete Element Method. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 86, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Ma, Q.; Cai, G.; Ma, D.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H. Influence of Intermediate Principal Stress Ratio on Strength and Deformation Characteristics of Frozen Sandy Soil under Different Moisture Contents. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 213, 103909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Ye, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, F. Experimental Investigation on Mechanical Behavior of Natural Soft Clay by True Triaxial Tests. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yao, Z.; Wang, X.; Song, Z. The Mechanical Properties of Frozen Peat Soil under True Triaxial Testing and Intelligent Constitutive Modeling Based on Prior Information. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 236, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comanici, A.M.; Barsanescu, P.D. Modification of Mohr’s Criterion in Order to Consider the Effect of the Intermediate Principal Stress. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 108, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.H. Unified Strength Theory and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: Singapore; Xi’an Jiaotong University Press: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.H. Unified Strength Theory for Geomaterials and its Applications. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 1994, 16, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Fan, W.; Yu, B.; Wang, Y. Influence of the Unified Strength Theory Parameters on the Failure Characteristics and Bearing Capacity of Sand Foundation Acted by a Shallow Strip Footing. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1687814020907774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J. Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Strip Foundations in Unsaturated Soils Considering the Intermediate Principal Stress Effect. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8854552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liao, H.; Dang, F.-N. Influence of Intermediate Principal Stress on the Bearing Capacity of Strip and Circular Footings. J. Eng. Mech. 2014, 140, 4014041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Fan, W.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y. Parametric Study of the Unified Strength Theory for a Loess Foundation Supporting a Strip Footing. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, M.; Wang, S.; Cao, H.; Li, T. Closed-form Solutions of Translatory Coal Seam Bumps Considering the Intermediate Principal Stress and Gas Pressure. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2025, 49, 2695–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.H.; Wu, X.X.; Shi, J.; Zhou, G.C. A New Method for Determining Soil Failure Criteria. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 54, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C. Ultimate Bearing Capacity of a Strip Foundation near Slopes Based on the Unified Strength Theory. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xiao, S. An Upper Bound Solution to Undrained Bearing Capacity of Rigid Strip Footings near Slopes. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 18, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, J.; Lai, V.Q.; Keawsawasvong, S. Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines Analysis for 3D Slope Stability in Anisotropic and Heterogenous Clay. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, A.; Carillo, N. Shear Failure of Anisotropic Materials. J. Boston Soc. Civ. Eng. 1944, 31, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, K.; Craig, W.H. Bearing Capacity of Circular Foundations on Soft Clay of Strength Increasing with Depth. Soils Found. 1995, 35, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.S.; Rao, K.N.V. Bearing Capacity of Strip Footing on c-φ Soils Exhibiting Anisotropy and Nonhomogeneity in Cohesion. Soils Found. 1982, 22, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.Y. Stability of Slopes in Anisotropic Soils. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1965, 91, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Deng, X. Calculation of Upper Bound of Bearing Capacity of Non-homogeneous and Anisotropic Foundation Adjacent to Slope. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2019, 36, 21–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, M.S.; Laman, M. Model Studies of Bearing Capacity of Strip Footing on Sand Slope. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2013, 17, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, F.; Lentini, V. Evaluation of the Bearing Capacity of Footings on Slopes. Int. J. Phys. Model. Geotech. 2012, 12, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| B (m) | L (m) | Measured qu (kPa) | Predicted qu (kPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b = 0 | b = 0.75 | b = 1 | |||

| 0.04 | 0.14 | 65.67 | 40.14 | 66.81 | 74.05 |

| 0.04 | 0.28 | 79.00 | 67.69 | 112.71 | 124.80 |

| 0.06 | 0.13 | 88.26 | 53.39 | 89.31 | 99.14 |

| 0.06 | 0.27 | 136.37 | 82.81 | 137.63 | 152.47 |

| 0.08 | 0.12 | 125.31 | 82.77 | 138.52 | 153.84 |

| 0.08 | 0.21 | 156.88 | 106.57 | 177.05 | 196.26 |

| 0.10 | 0.11 | 162.4 | 107.56 | 180.50 | 200.63 |

| 0.10 | 0.20 | 205.5 | 133.56 | 222.39 | 246.72 |

| MRE (%) | 36.3 | 6.2 | 17.8 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Su, T.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, S. Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Vertically Uniform Loaded Strip Foundations near Slopes Considering Heterogeneity, Anisotropy, and Intermediate Principal Stress Effects. Buildings 2025, 15, 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234386

Yan Q, Wang Y, Su T, Zhang Z, Sun S. Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Vertically Uniform Loaded Strip Foundations near Slopes Considering Heterogeneity, Anisotropy, and Intermediate Principal Stress Effects. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234386

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Qing, Yuhao Wang, Tian Su, Zengzeng Zhang, and Shanshan Sun. 2025. "Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Vertically Uniform Loaded Strip Foundations near Slopes Considering Heterogeneity, Anisotropy, and Intermediate Principal Stress Effects" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234386

APA StyleYan, Q., Wang, Y., Su, T., Zhang, Z., & Sun, S. (2025). Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Vertically Uniform Loaded Strip Foundations near Slopes Considering Heterogeneity, Anisotropy, and Intermediate Principal Stress Effects. Buildings, 15(23), 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234386