Numerical Analysis on Seismic Performance of Concrete-Encased CFST Columns with Two-Stage Initial Stresses

Abstract

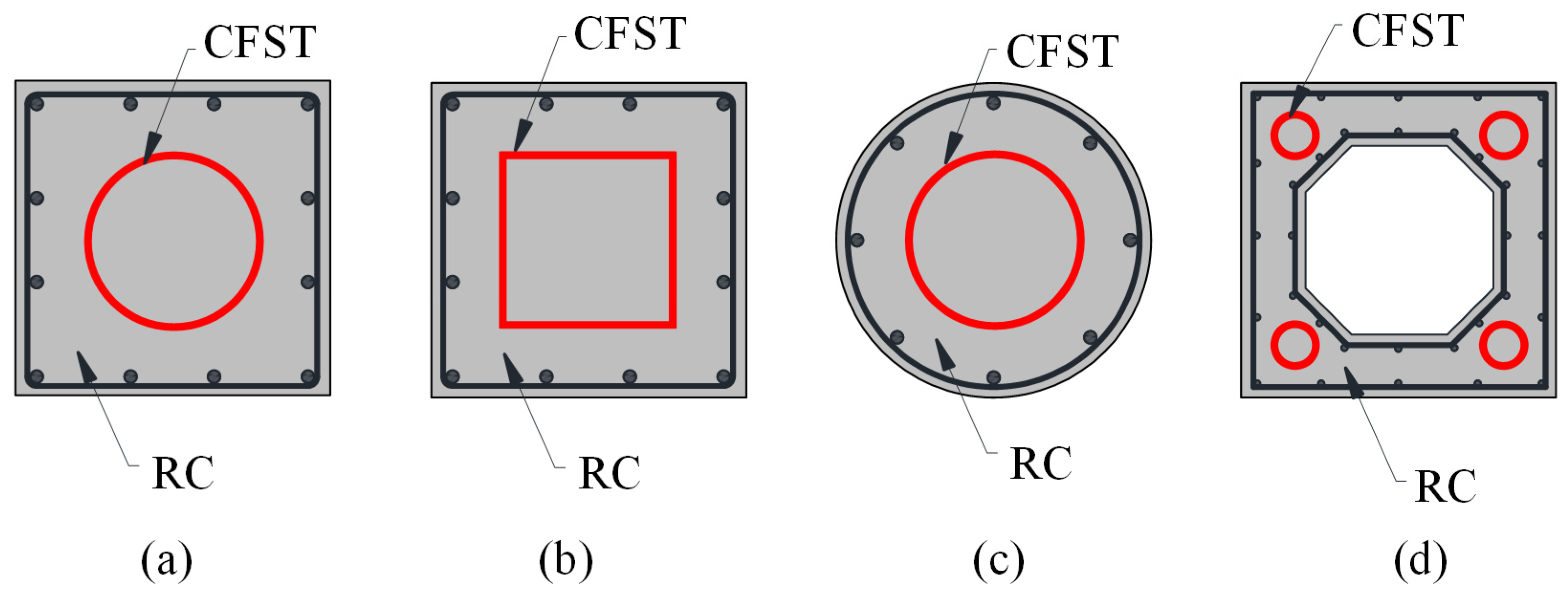

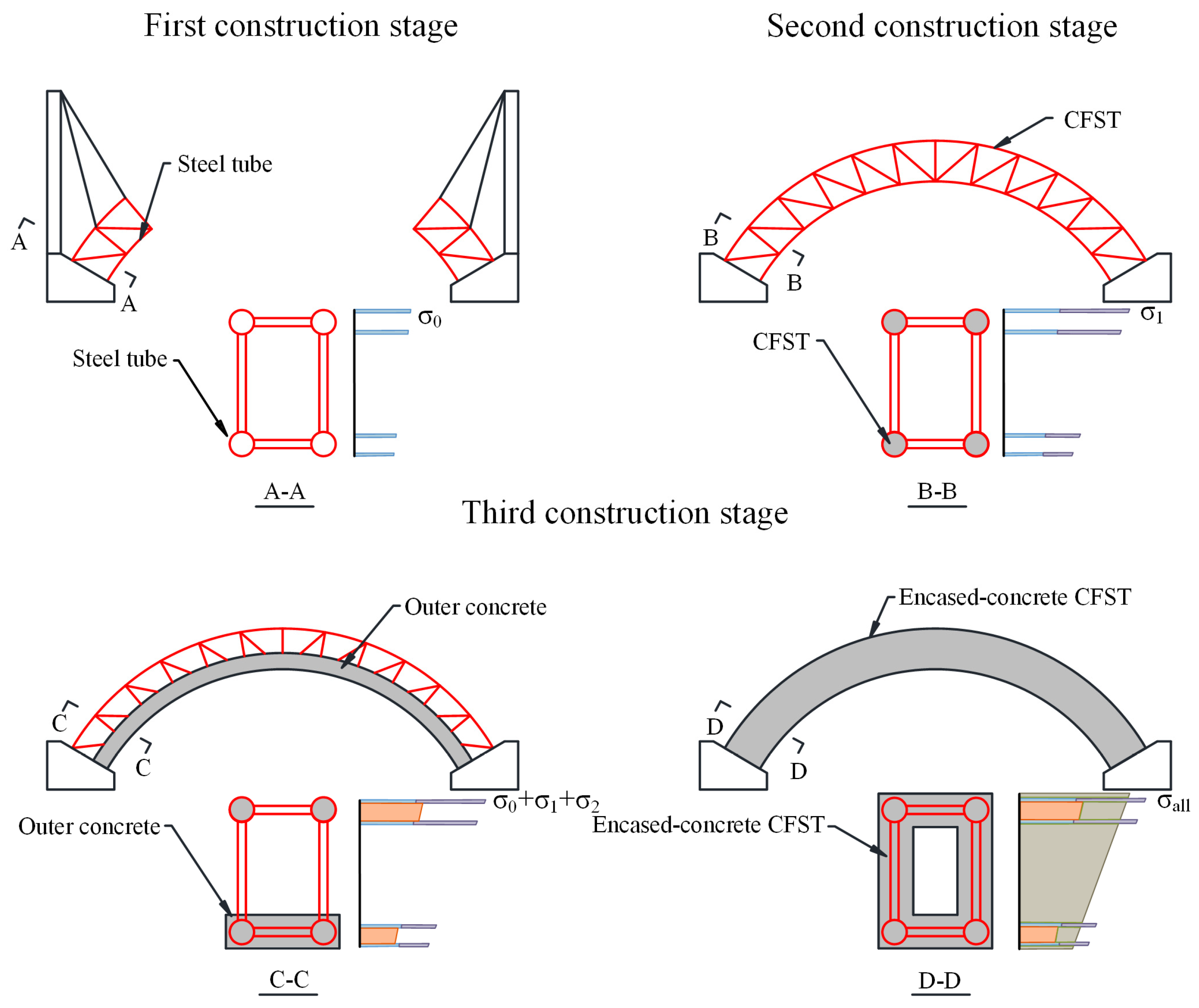

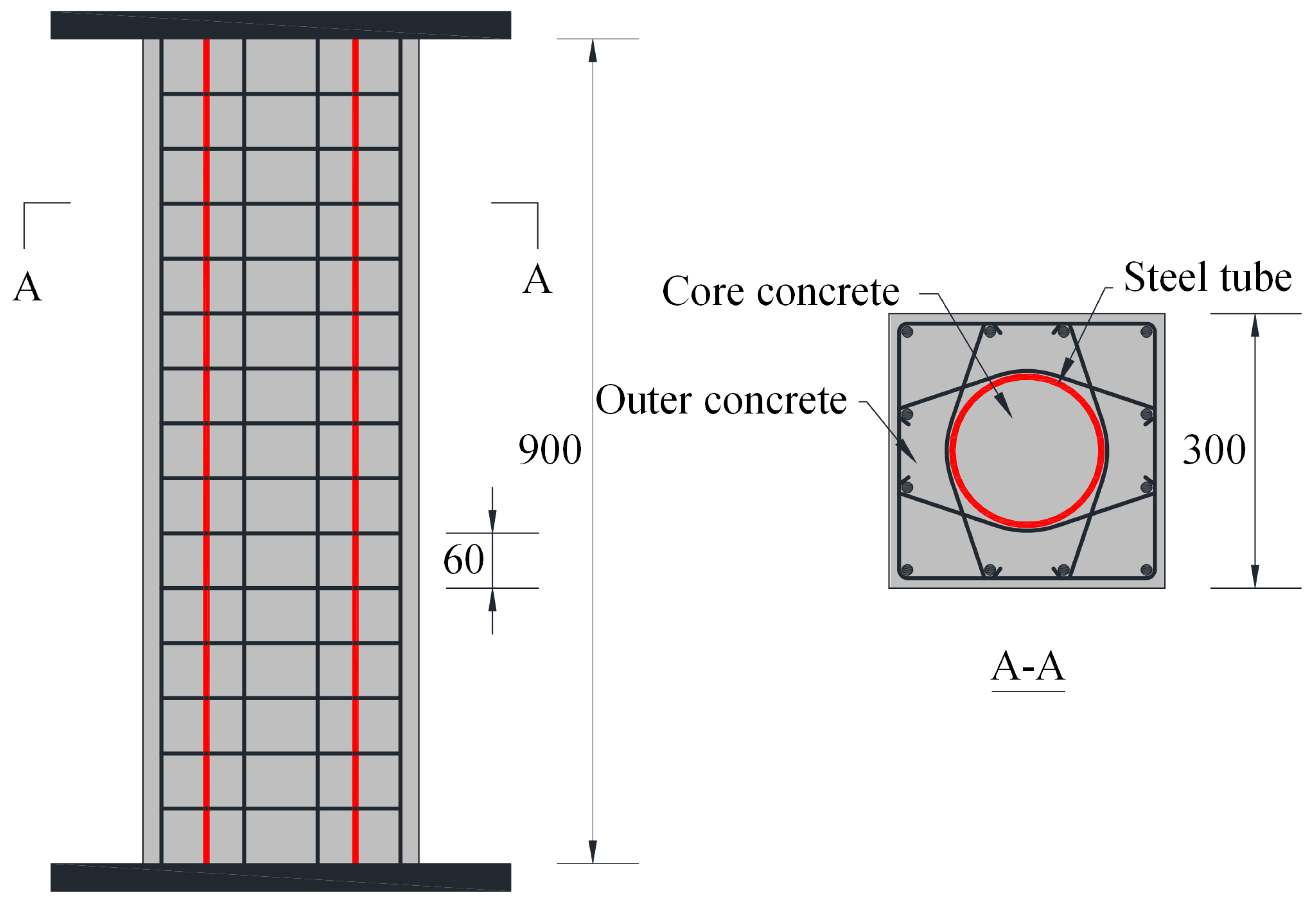

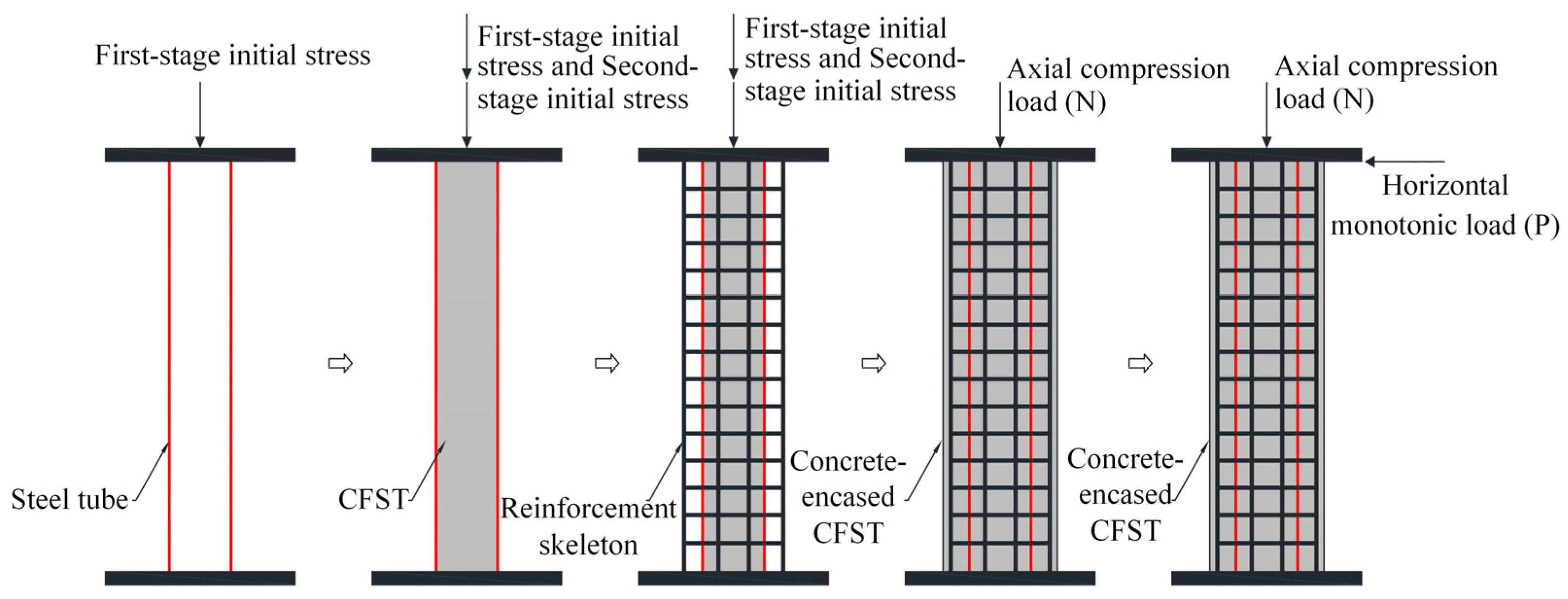

1. Introduction

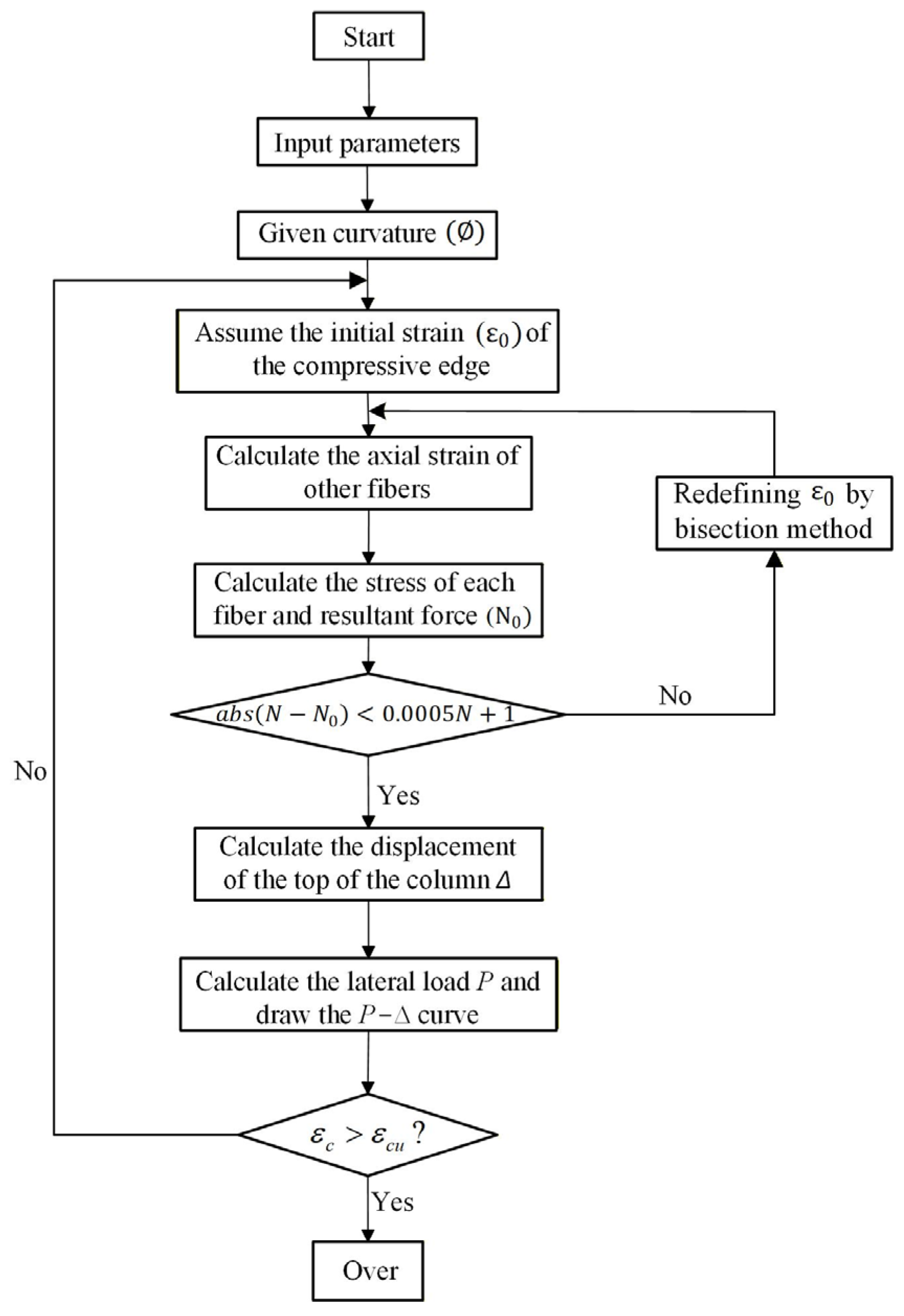

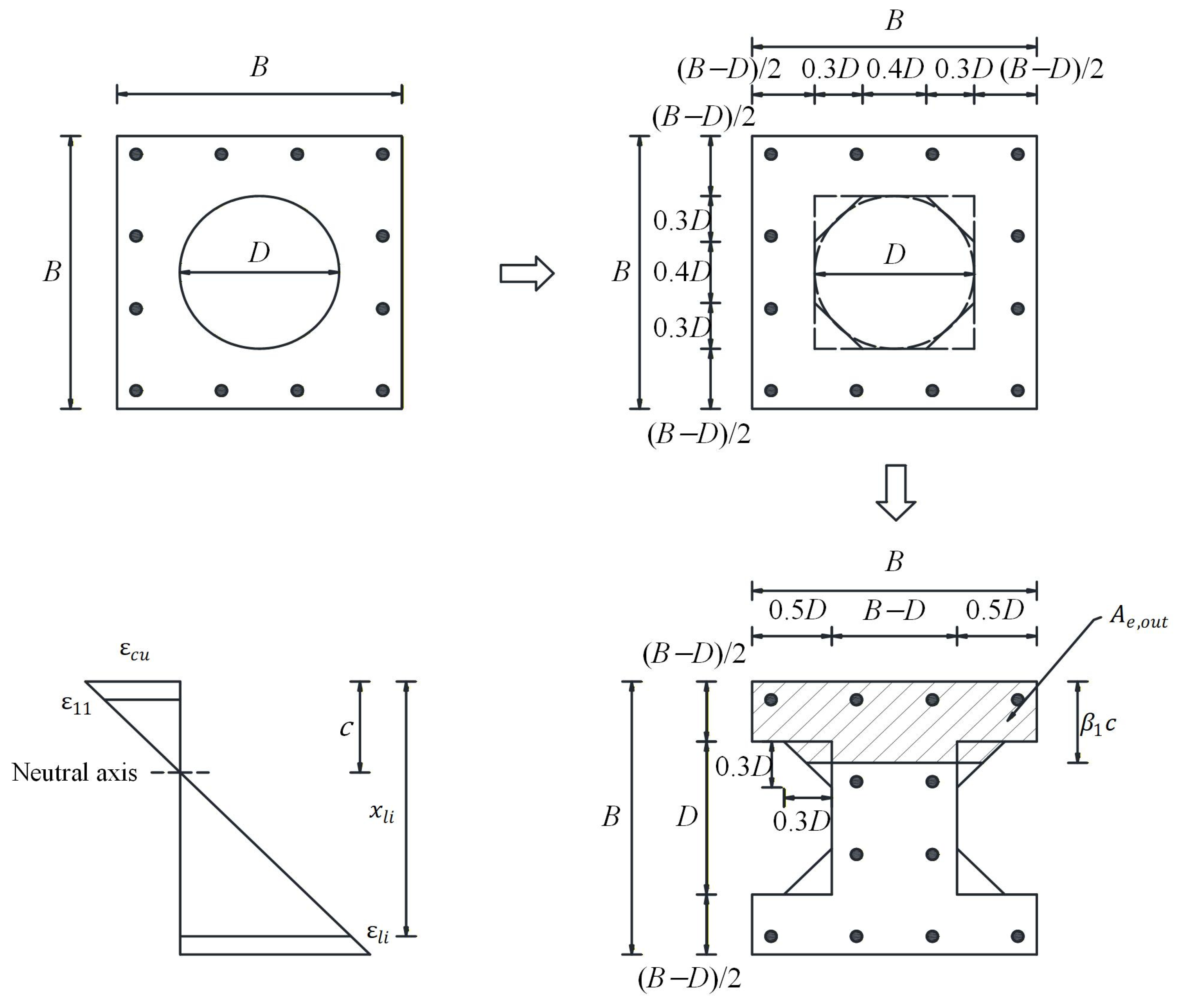

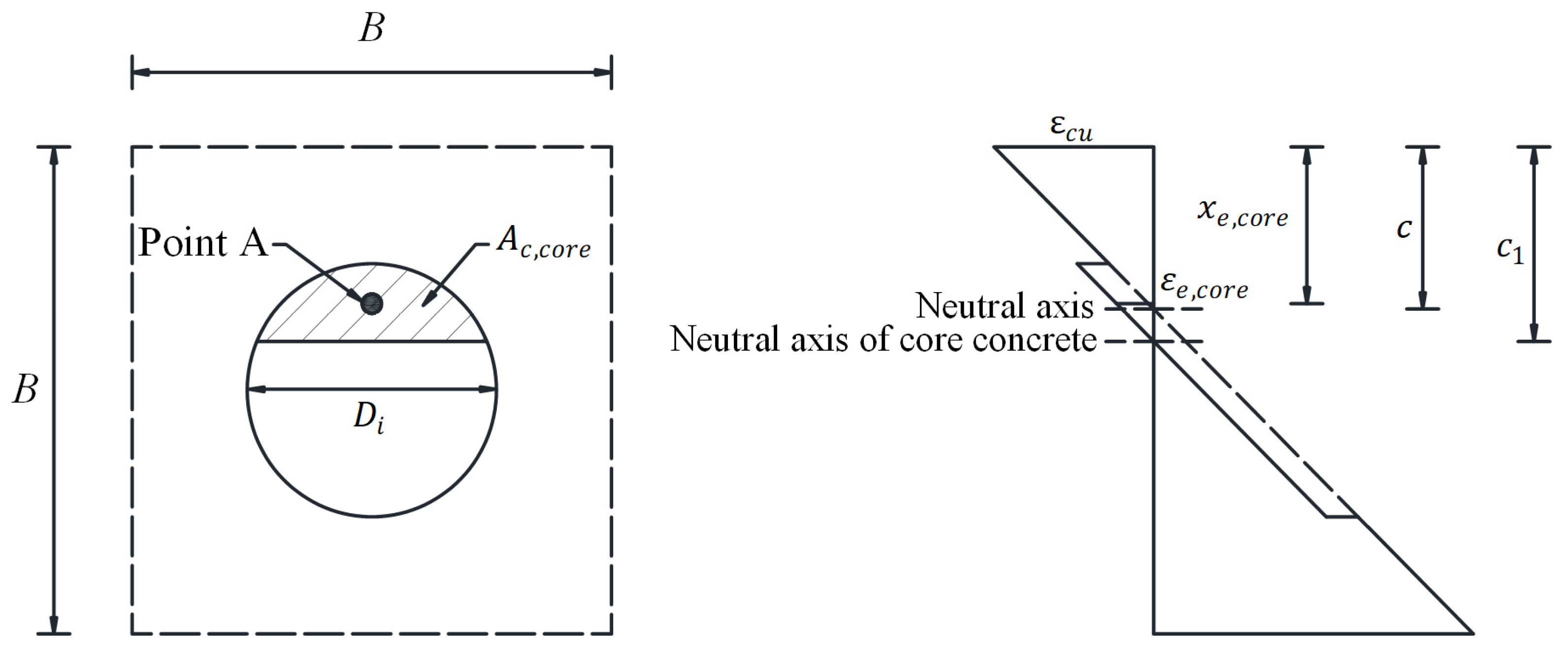

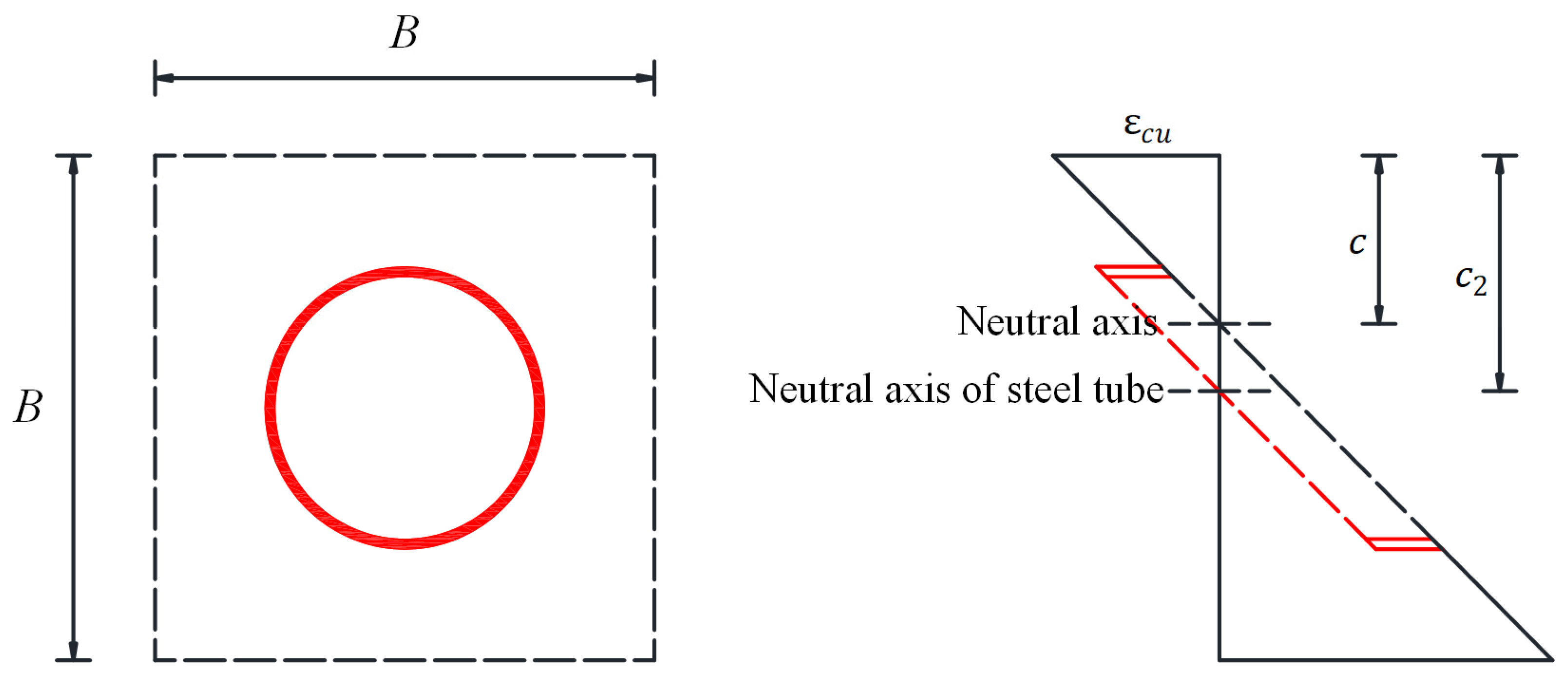

2. Fiber Element Method for Analysis of Monotonic Compression-Bending Behavior

2.1. Fundamentals and Procedures of the Fiber Element Method

- Uniform distribution of preloads: The preloads are uniform throughout the cross-sections of the steel tube and the in-tube concrete.

- Plane section assumption: Cross-sections that are plane before deformation remain plane after deformation. Accordingly, the increments of normal strain vary linearly over the cross-section height.

- Negligible shear deformation: Shear deformation is disregarded in the analysis.

- No interfacial slip: Full composite action is maintained at the steel-concrete interface, precluding any interfacial slip.

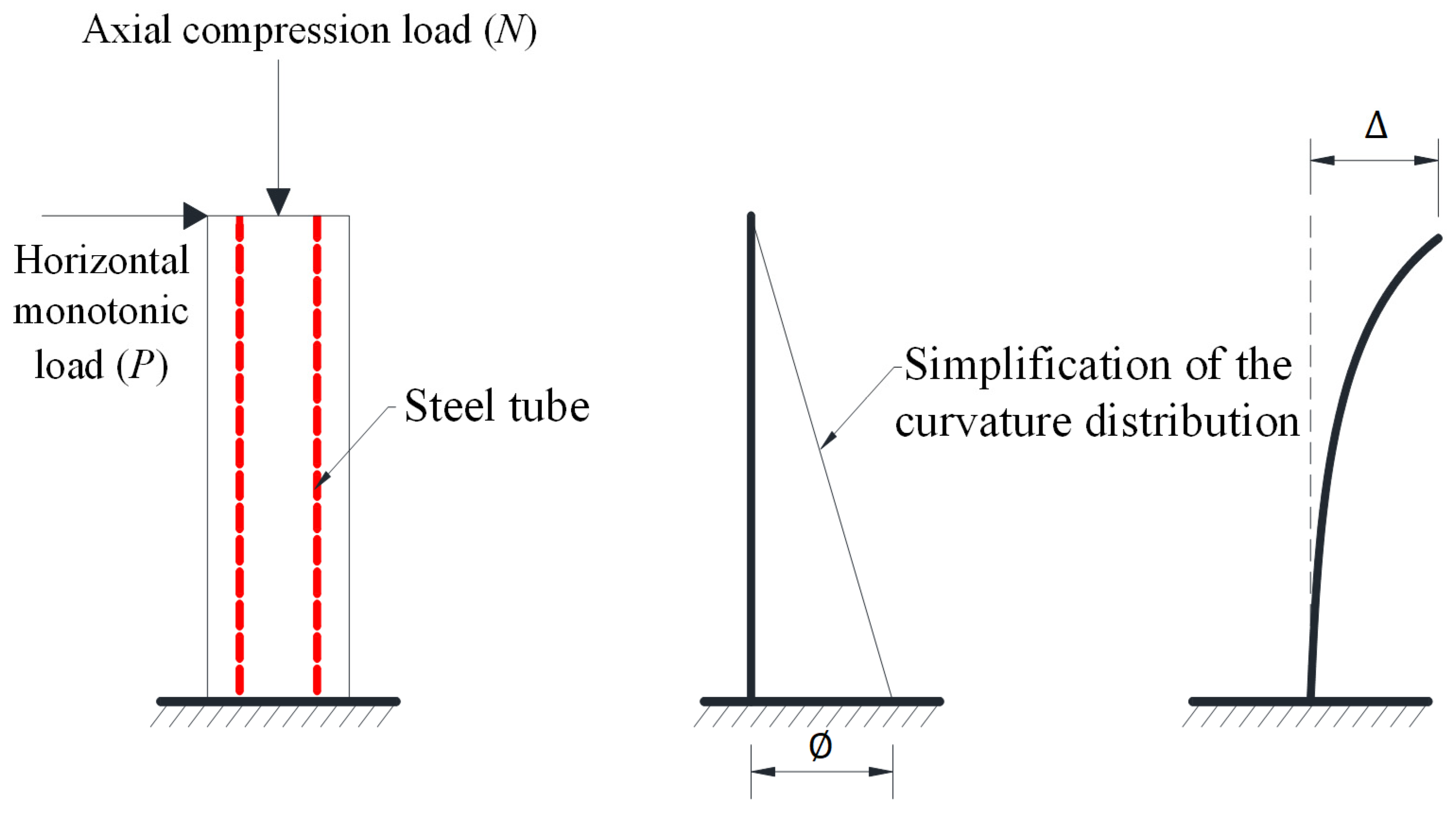

- Linear curvature distribution: The sectional curvature is postulated to vary linearly along the column height H, as schematically represented in Figure 5. The lateral displacement () at the column top is consequently governed by the curvature () at the critical bottom section through the following expression:

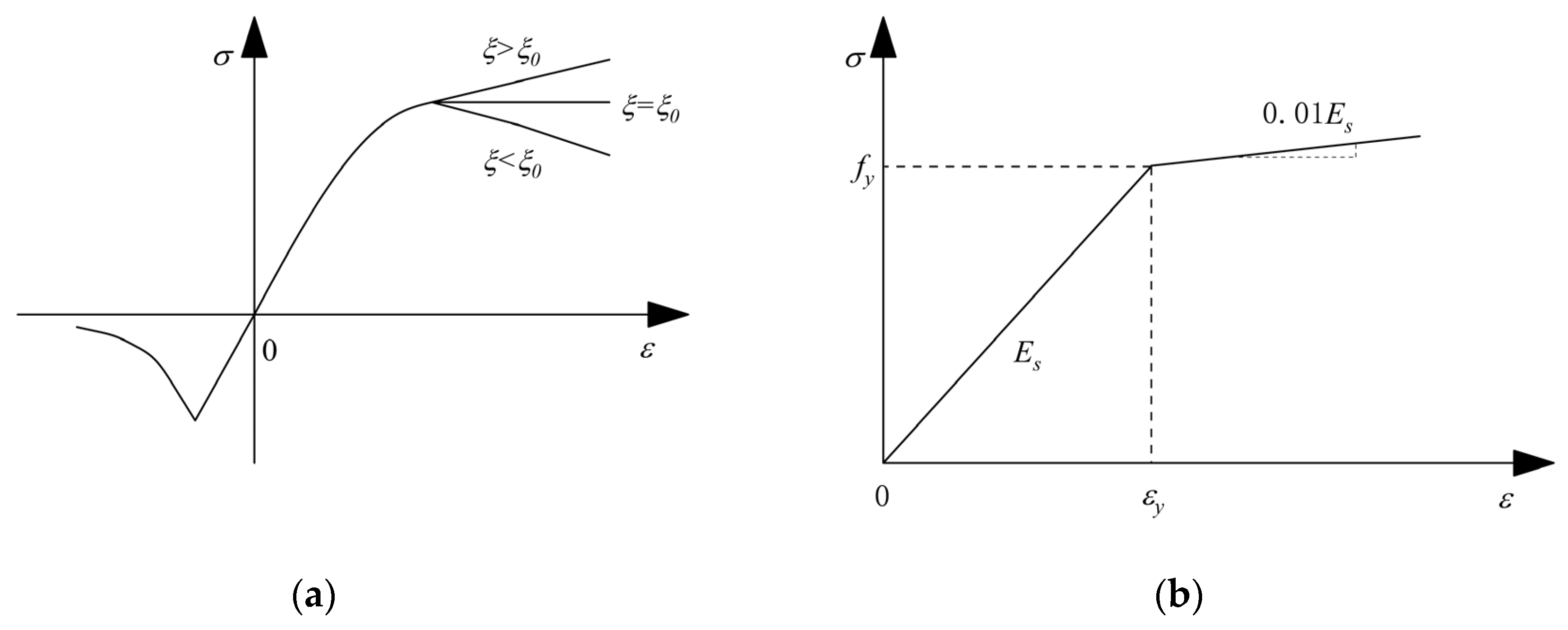

2.2. Constitutive Relationships of Materials

2.2.1. Concrete

2.2.2. Steel

2.3. Validation of the Proposed Fiber Element Method

3. Effects of Two-Stage Preloads on Monotonic Compression-Bending Behavior

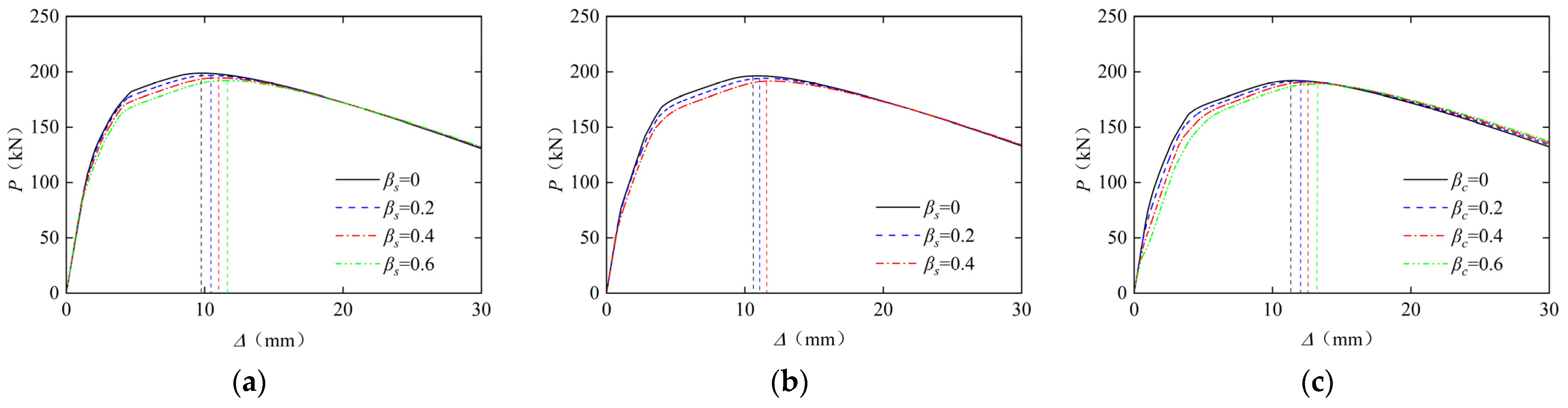

3.1. Effects of Two-Stage Preloads on Lateral Load–Displacement Relationship

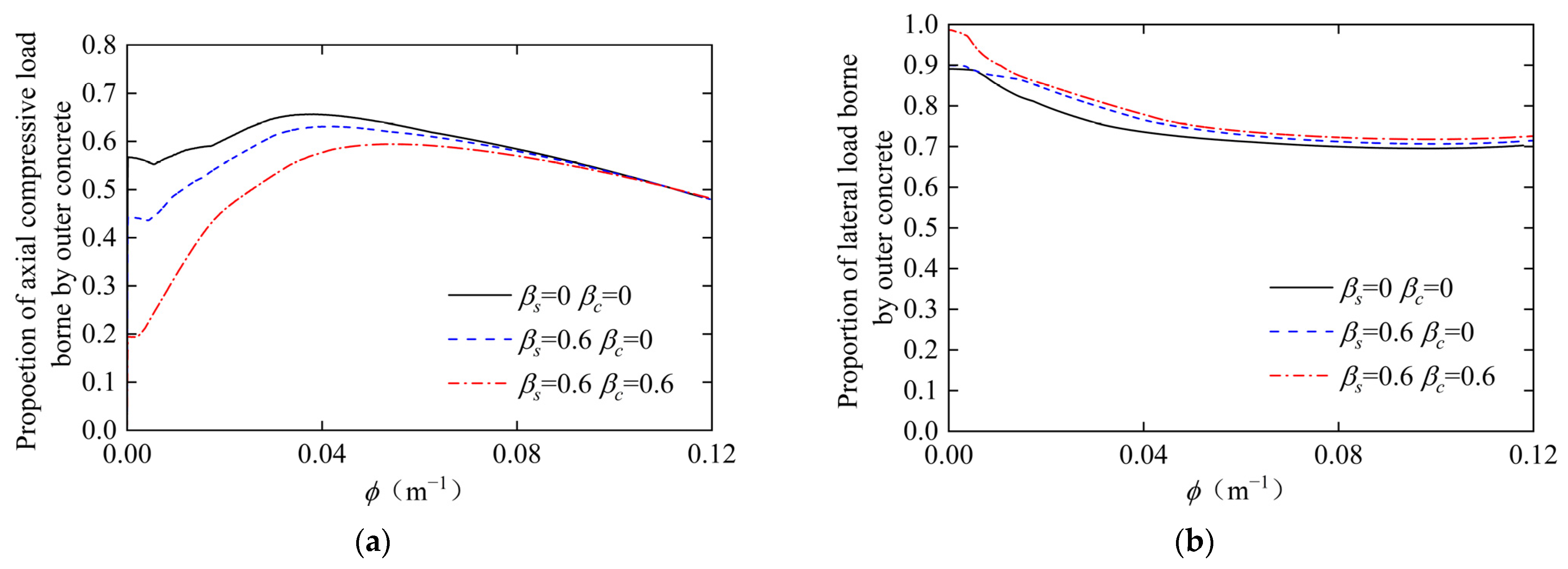

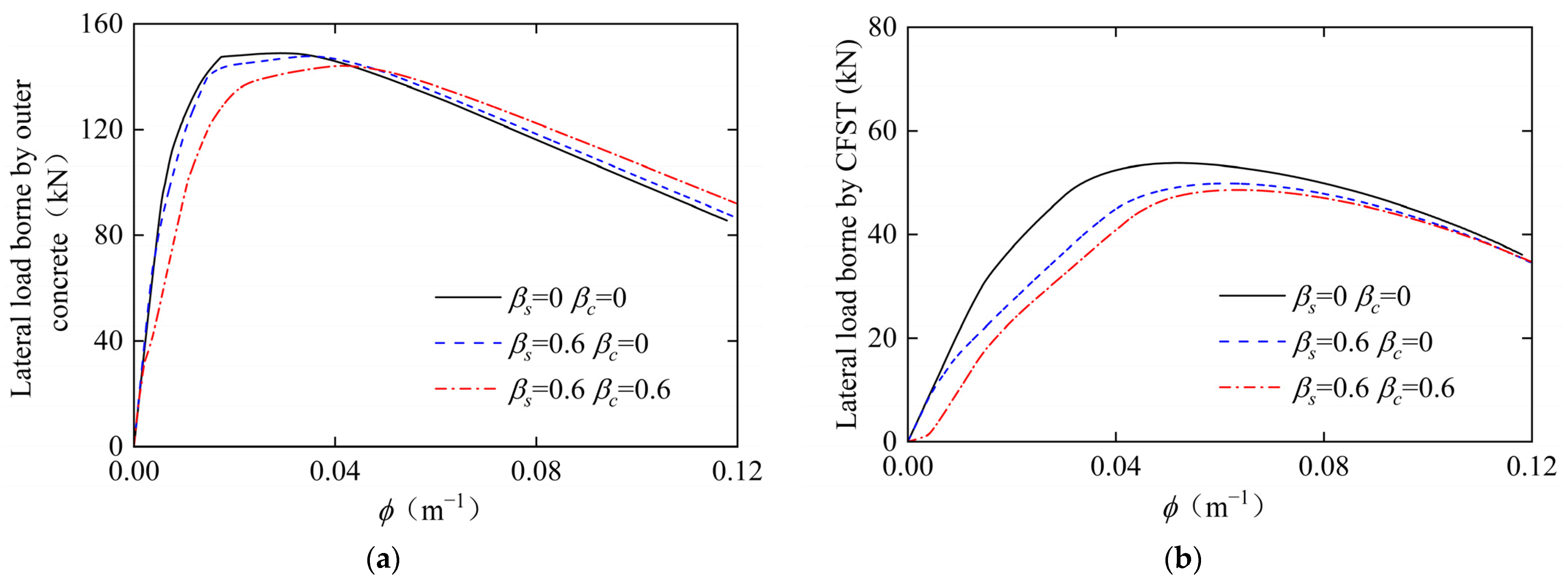

3.2. Effects of Two-Stage Preloads on Load-Bearing Mechanism

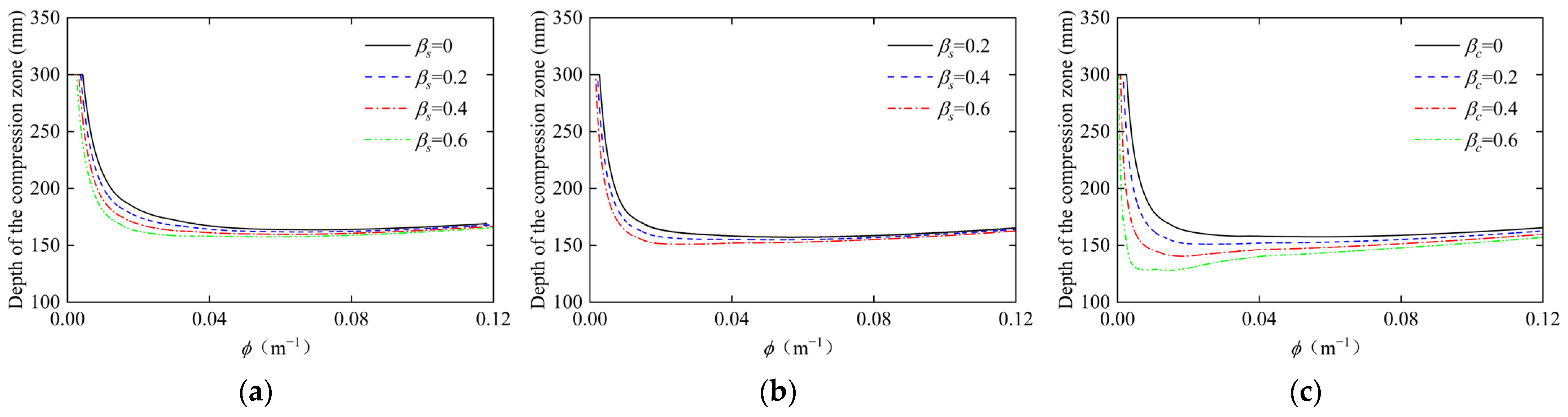

3.3. Effects of Two-Stage Preloads on Compression Zone Depth

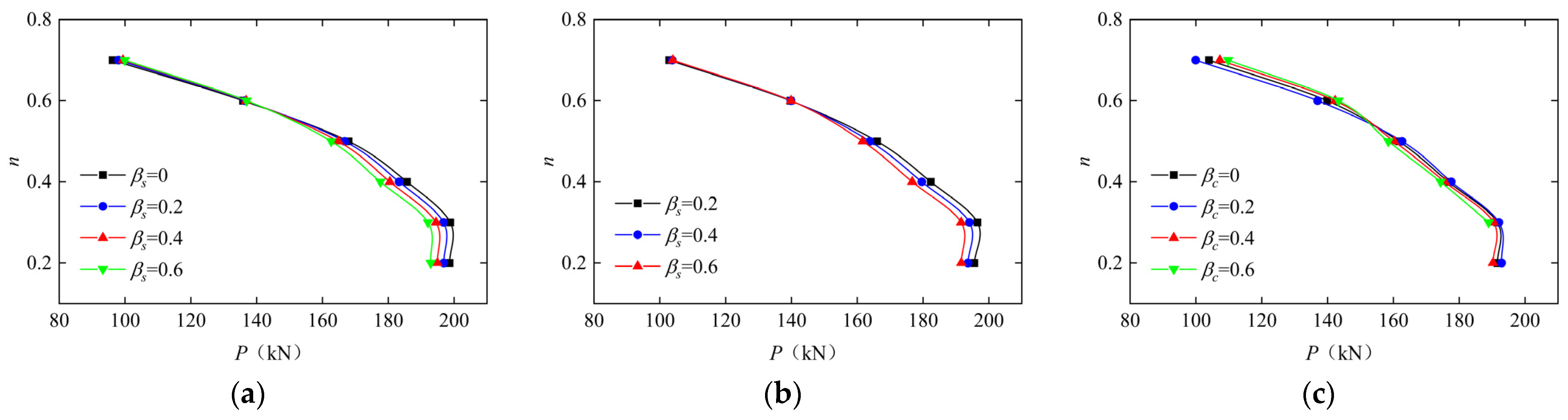

3.4. Effects of Two-Stage Preloads on n-P Relationship

4. Parametric Analysis of Monotonic Compression-Bending Behavior

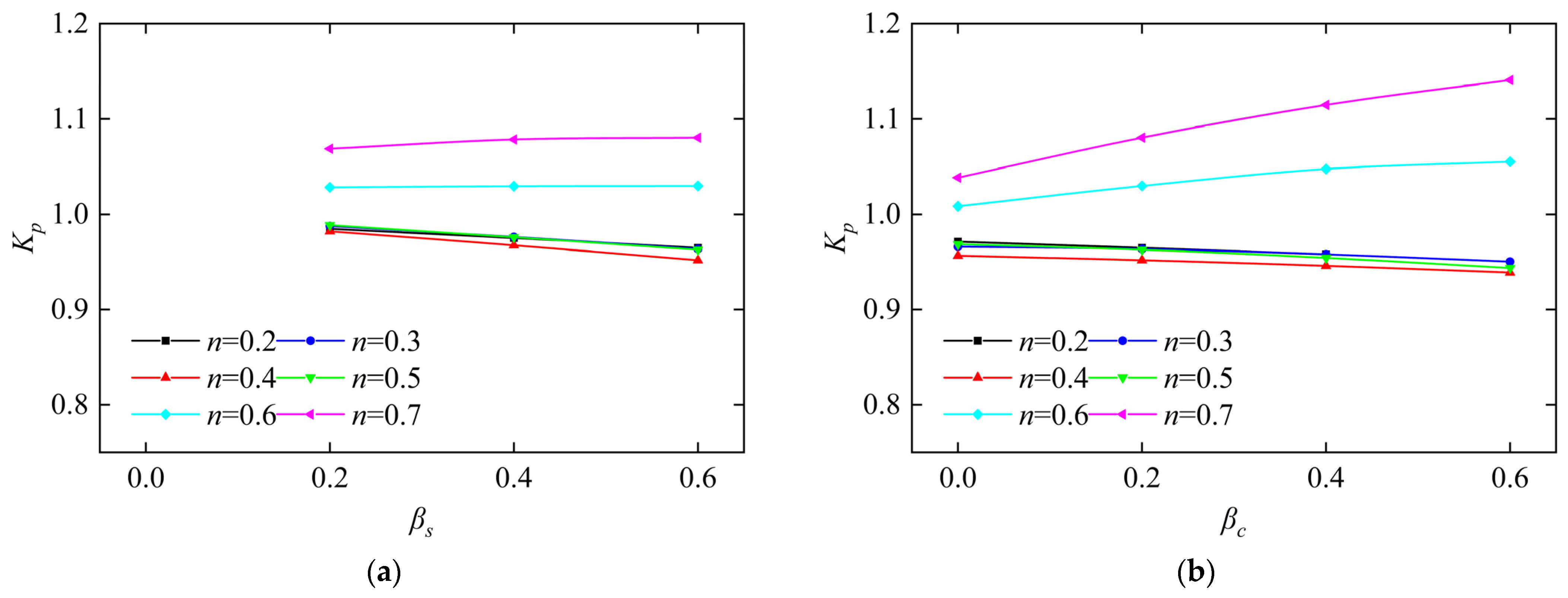

4.1. Effect of Axial Compression Ratio (n)

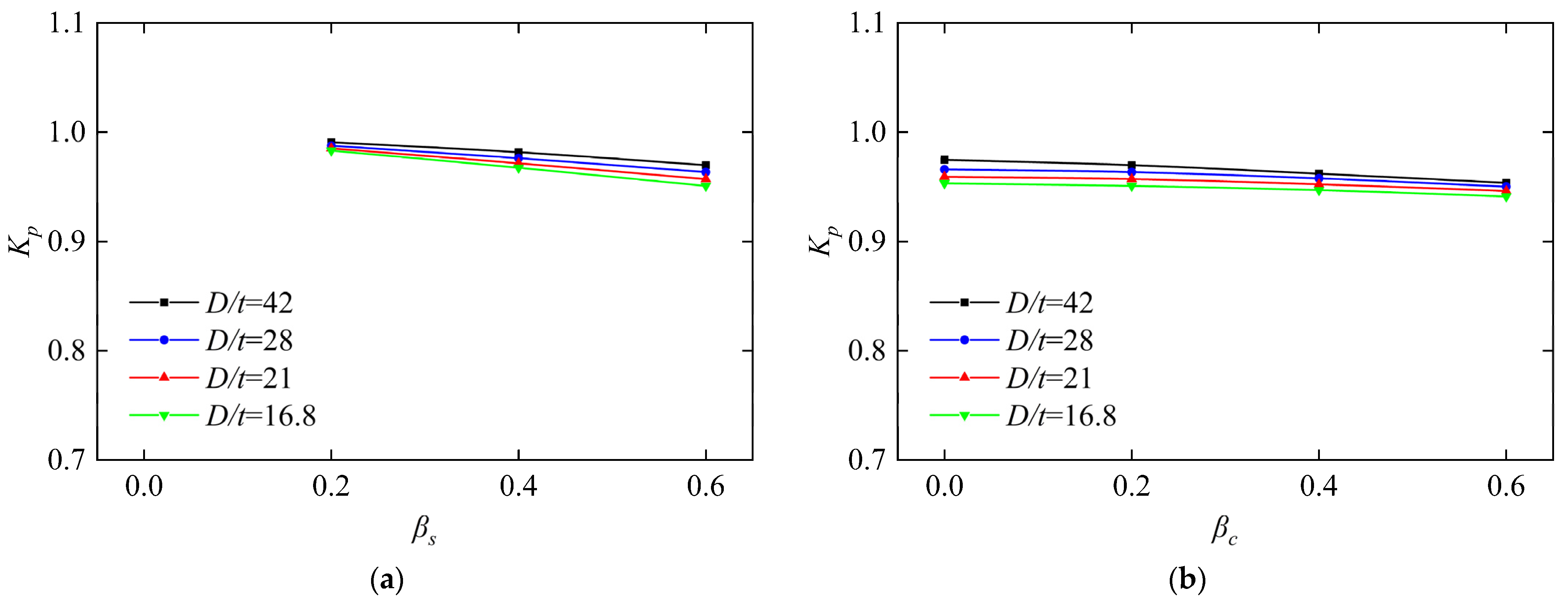

4.2. Effects of Steel Tubular Diameter-to-Thickness Ratio (D/t)

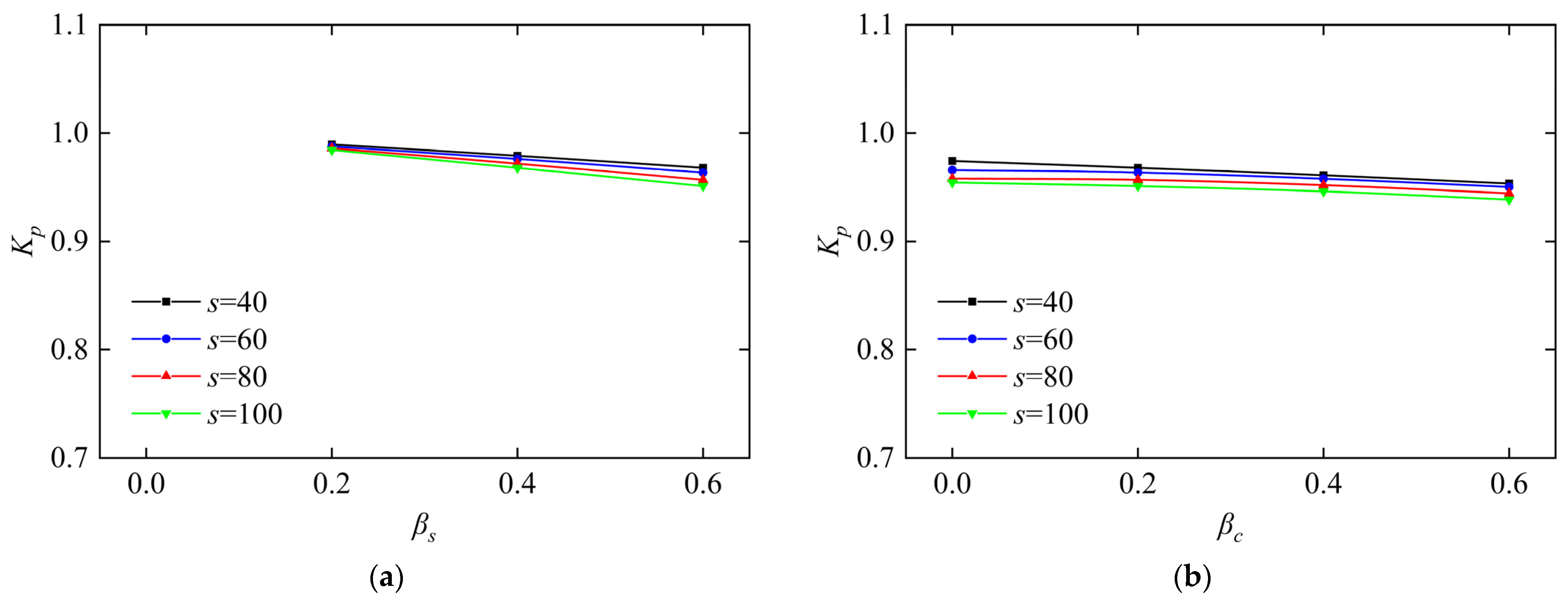

4.3. Effects of Stirrup Spacing (s)

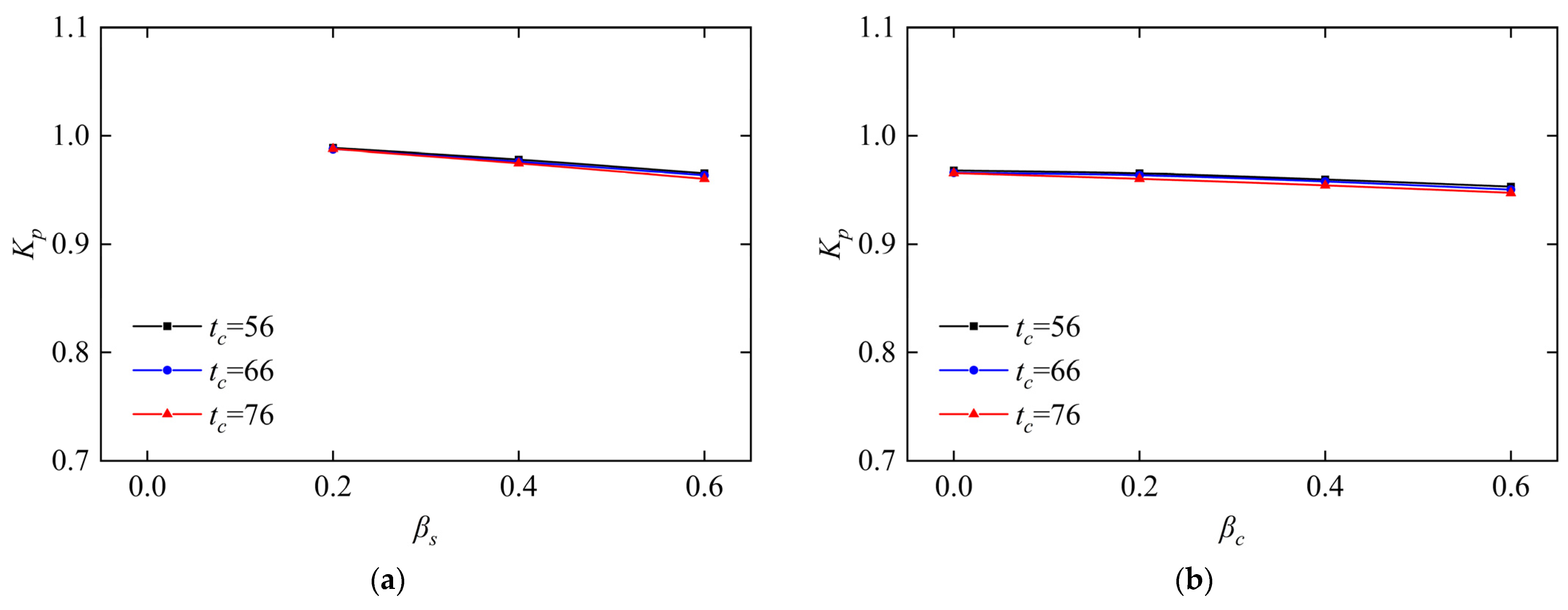

4.4. Effects of Encased Concrete Thickness ()

5. Establishment of Restoring Force Model of CE-CFST Columns with Two-Stage Preloads

5.1. Establishment of Skeleton Curve

5.1.1. Parameters Unaffected by Two-Stage Preloads

- Yield load

- 2.

- Peak displacement

- 3.

- Failure load

- 4.

- Unloading stiffness

5.1.2. Parameters Affected by Two-Stage Preloads

- Elastic stage stiffness

- 2.

- Ultimate lateral load-bearing capacity

- (a)

- Contribution of encased RC component

- (b)

- Contribution of CFST Component

- 3.

- Degradation stiffness in descending stage

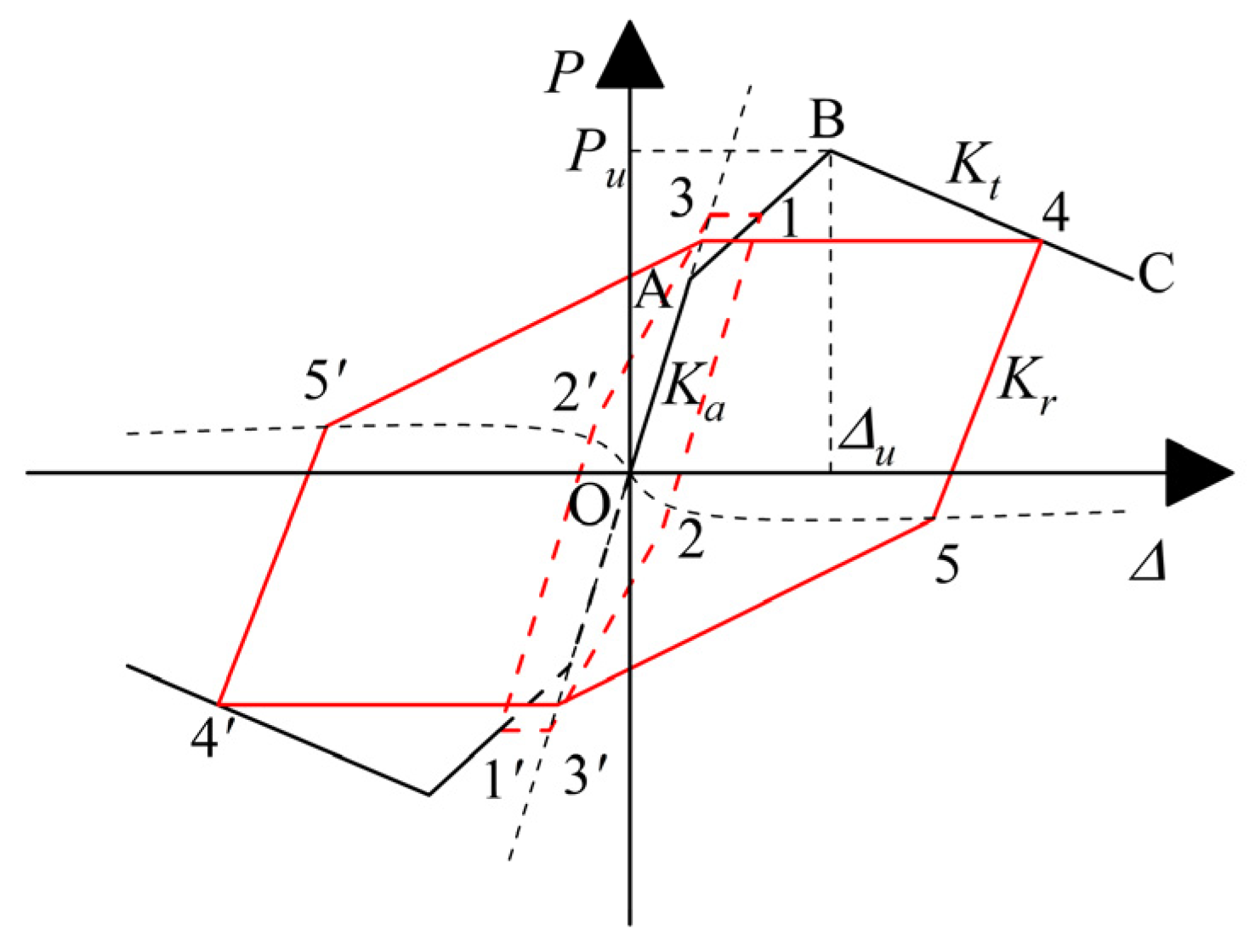

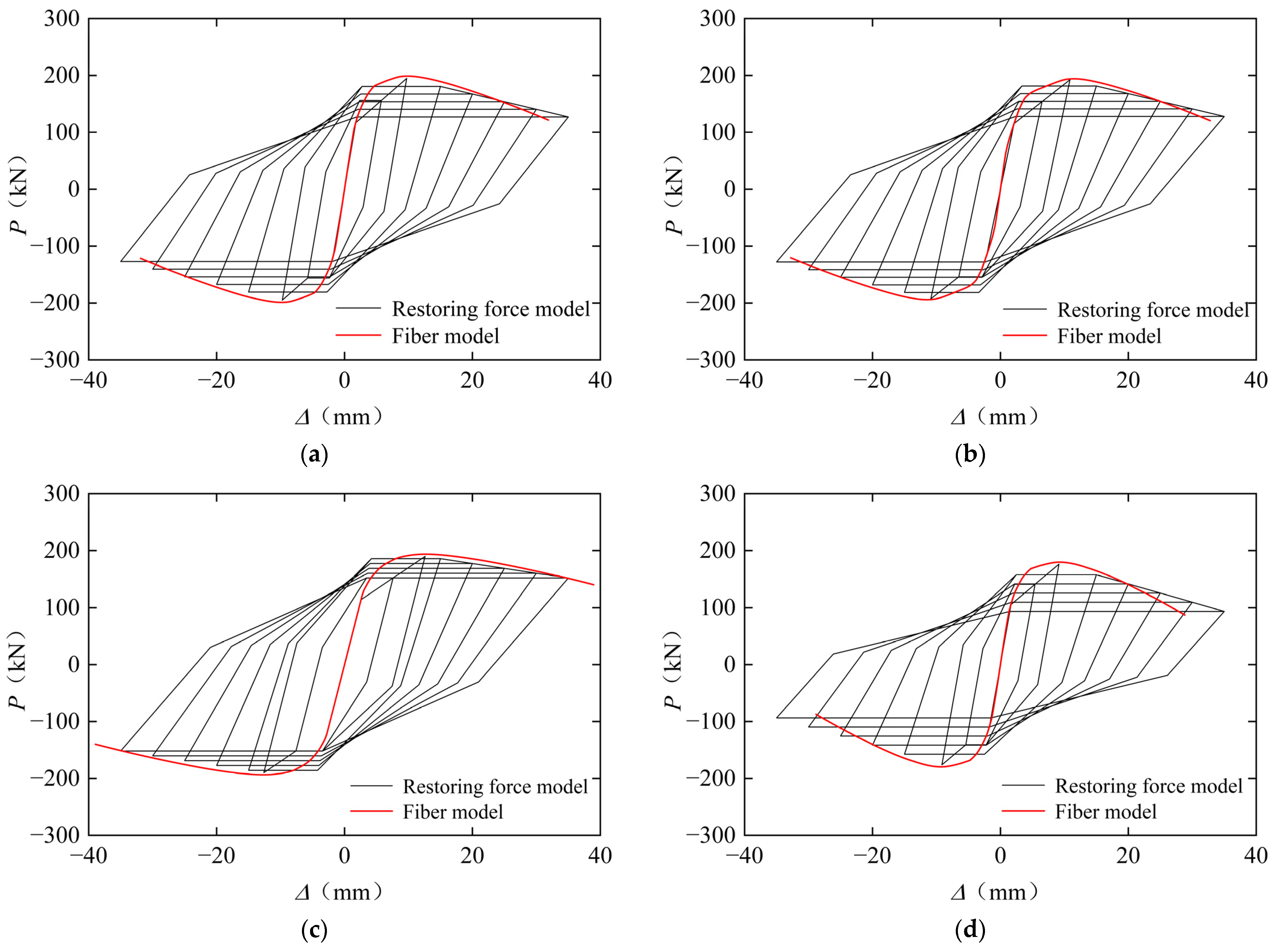

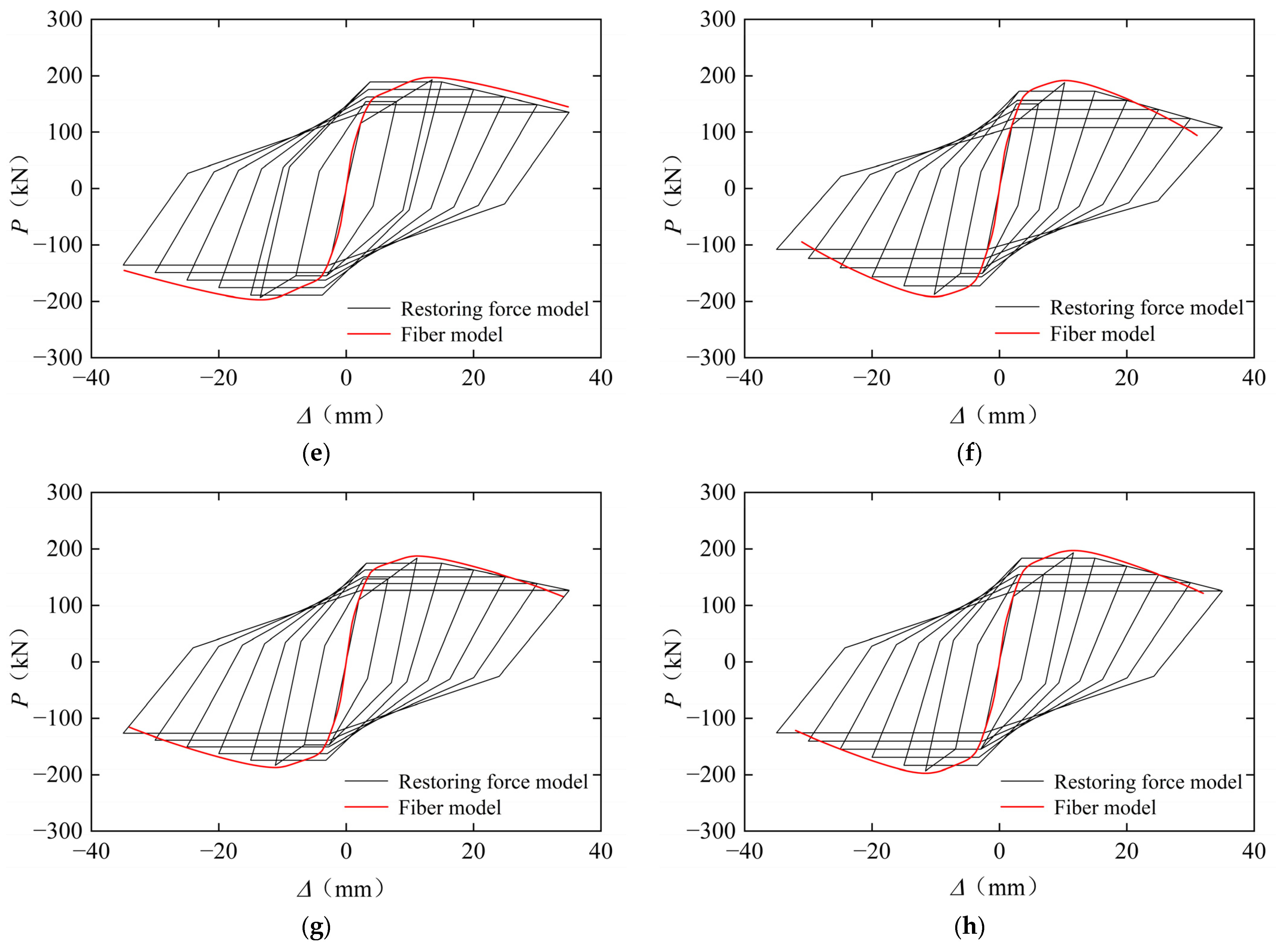

5.2. Hysteretic Rules

- Elastic stage (O–A): For loads below the yield load (), both loading and unloading are collinear along segment O–A, defining the stage of constant stiffness .

- Hardening stage (A–B): When the load exceeds but remains below the ultimate load , the loading path follows segment A–B. Unloading from any point 1 on segment A–B is directed toward point 2, with both loading and unloading stiffnesses equal to . The absolute load value at point 2 is one-fifth of that at point 1. Reloading then commences in the reverse direction from point 2 to point 3, where the absolute load value equals that at point 1. Subsequent loading continues to point 1′ on the skeleton curve. These rules are repeated analogously for forward loading, thereby completing a full hysteretic loop.

- Descending stage (B–C): Upon exceeding the peak displacement () while remaining below the failure displacement (), the loading path follows segment B–C. Unloading from any point 4 on segment B–C proceeds toward point 5 with unloading stiffness (). The absolute load value at point 5 equals one-fifth of that at point 4. Reloading then continues in the reverse direction from point 5 to point 6, where the absolute load value matches that at point 4. Subsequent loading proceeds to point 4′ on the skeleton curve, and the same rules apply for forward loading, thereby completing the hysteretic loop.

- Loop continuation: The complete restoring force model is assembled through the systematic synthesis of all hysteretic loops, each generated by the aforementioned rules, with the skeleton curve serving as the foundational backbone.

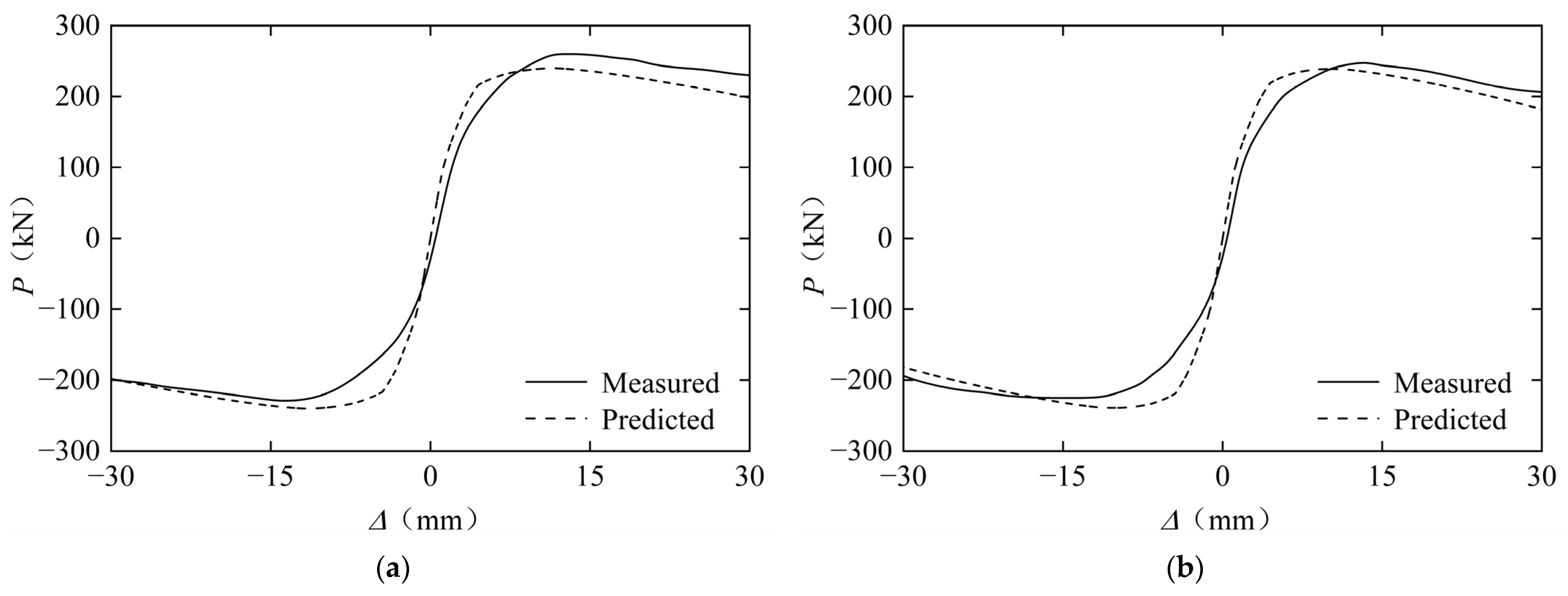

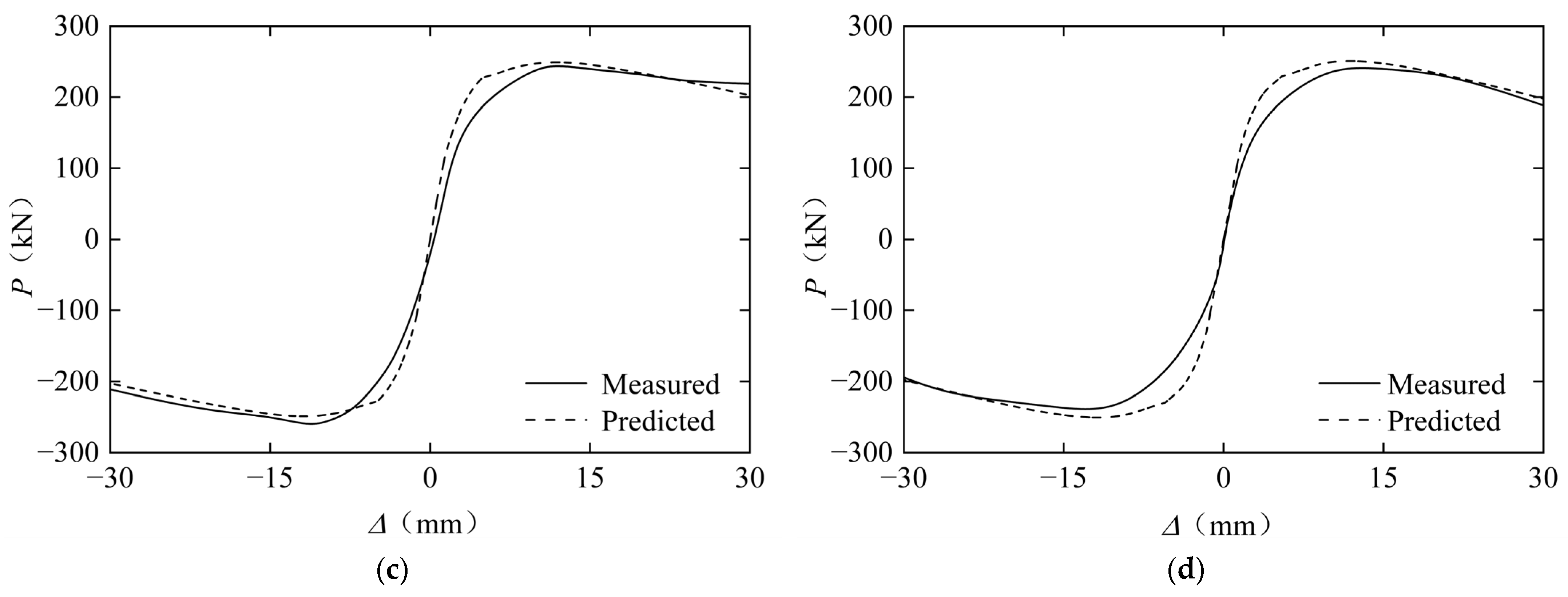

5.3. Validation of the Restoring Force Model

6. Conclusions

- Two-stage preloads significantly alter the internal force distribution by reducing the axial compression ratio (n) carried by the external reinforced concrete (RC) component and conversely increasing that borne by the internal concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) component. This redistribution alters the relationship between the axial compression ratios of these components and their respective critical axial compression ratios. This redistribution consequently exhibits a threshold behavior around n = 0.5: it enhances both the lateral ultimate bearing capacity and ductility at lower ratios (n < 0.5) but impairs them at higher ratios (n > 0.5). For the baseline columns with n = 0.3, the ultimate lateral load-bearing capacity and its corresponding displacement were maximally improved by 3.4% and 18.9%, respectively, across the investigated preload combinations.

- The preloads lead to a significant reduction in the compression zone depth of the CE-CFST section. Specifically, as the preloads increase, the transition from a fully compressed cross-section to a partially compressed cross-section occurs at an earlier stage. Moreover, both the rate and magnitude of the reduction in compression zone depth with increasing sectional curvature become more pronounced. The baseline columns show a maximum compression zone depth variation of 32 mm with changes in steel tubular preload, compared to 78 mm with in-tube concrete preload variation, demonstrating that the in-tube concrete preload has a significantly more pronounced effect on compression zone development.

- Parametric analysis reveals the axial compression ratio (n), stirrup ratio (), and diameter-to-thickness ratio (D/t) as dominant factors governing steel tubular preload effects. In comparison, in-tube concrete preload is primarily moderated by n and D/t ratios.

- Following the conventional framework for curve-type restoring force models, a specialized degenerate trilinear model was established for CE-CFST columns with two-stage preloads using parameters derived from monotonic compression-bending analysis. Consequently, it can serve as a practical sectional constitutive relationship for the seismic analysis of structures incorporating CE-CFST members with two-stage preloads.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, L.; Tao, Z. Modern Composite and Hybrid Structures: Experiments, Theories and Methods; Yang, J., Ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 1–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Liao, F. Performance of concrete filled steel tube reinforced concrete columns subjected to cyclic bending. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2009, 65, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sun, J.G. Finite Element Analysis on the Temperature Field within Steel Tube Reinforced Columns. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 163, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Han, L. Behaviour of composite joints with concrete encased CFST columns under cyclic loading: Experiments. Eng. Struct. 2014, 59, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaddiwudhipong, S.; Jiang, D. Steel-reinforced concrete joints under reversal cyclic load. Mag. Concr. Res. 2003, 55, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Mou, T. Design theory of CFST (concrete-filled steel tubular) mixed structures and its applications in bridge engineering. China Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 53, 1–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Lee, H. Concrete-filled steel tube columns encased with thin precast concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2015, 141, 4015056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.; Li, Y. Axial Compressive Behavior of Concrete-Encased CFST Stub Columns with High-Level Two-Stage Initial Stresses. J. Bridge Eng. 2022, 27, 4022116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qin, Z.; Chen, Y. Equivalent beam-column method for simplified calculation of ultimate bearing capacity of concrete filled steel tubular arch. In Proceedings of the 16th National Bridge Academic Conference, Changsha, China, 1 May 2004. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wu, Q. Equivalent beam-column method to estimate in-plane critical loads of parabolic fixed steel arches. J. Bridge Eng. 2009, 14, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, B. Equivalent beam-column method to calculate nonlinear critical load for cfst arch under compression and bending. Eng. Mech. 2010, 2010, 104–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Chen, B. Calculation of load-carrying capacity of reinforced concrete arch basing on equivalent beam-column method. J. Fuzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 2016, 110–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Kang, H. Seismic behavior and strength capacity of steel tube-reinforced concrete composite columns. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 43, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Kang, H. Experimental study on seismic behavior of high-strength concrete-filled steel tube composite columns. J. Build. Struct. 2009, 30, 85–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wu, B. Study on seismic performance of steel tube high strength concrete composite column. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 1998, 1998, 45–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z. Experimental research on mechanism and seismic performance of laminated column with steel tube filled with high-strength concrete. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 1999, 1999, 27–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Huang, Y. Study on seismic ductility of steel tube-reinforced concrete column. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2016, 36, 207–214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, D. Seismic performance limit states of steel tube-reinforced concrete columns. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2018, 38, 157–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Chen, K. Seismic behavior of concrete-filled circular steel tubular columns considering initial stress. J. Build. Struct. 2019, 40 (Suppl. S1), 234–240. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Shi, Q. Study on restoring force model of concrete-filled circular steel tubular columns under axial reciprocating load. Eng. Mech. 2021, 38, 170–179+198. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, X.; Yang, T. Restoring force model of high-strength concrete-encased CFST composite columns. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2021, 30, e1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shen, P. Present situation of nonlinear seismic response analysis of reinforced concrete high-rise structures. World Inf. Earthq. Eng. 1998, 14, 8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Zheng, C. A new method for dealing with the stiffness critical point in restoring force models. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2020, 2, 171–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 19–27. (In Chinese)

- CECS 188-2005; Technical Specification for Steel Tube-Reinforced Concrete Column Structure. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 17–26. (In Chinese)

- Han, L. Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Structures-Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Tong, A., Ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 67–273. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- T/CECS 663-2020; Technical Specification for Concrete-Encased Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 12–36. (In Chinese)

- Shen, J.; Wang, C. Finite Element and Shell Limit Analysis of Reinforced Concrete; Yao, M., Ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1993; pp. 36–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D. Researches on Behavior of Steel Tube-Reinforced Concrete Column. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Hunan, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.Y.; Han, L.H. Seismic performance of concrete-encased CFST piers: Analysis. J. Bridge Eng. 2018, 23, 04017119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y. Performance and Design Method of Square Concrete-Encased CFST Members Under Combined Compression and Bending. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X. Cyclic behavior of steel tube-reinforced high-strength concrete composite columns with high-strength steel bars. Eng. Struct. 2019, 189, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, W. Experimental Study of Hysteretic Behavior of Damage Controllability in Steel-Tube-Reinforced High-Strength Concrete Columns. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2021, 54, 144–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Han, L. Behaviour of concrete-encased CFST columns under combined compression and bending. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 101, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen Type | Specimen | D (mm) × t (mm) | B (mm) | fy (MPa) | fc,out/fc,core (MPa) | N (KN) | Stirrups | β1 | β2 | Pexp (kN) | Pfib (kN) | Pfib/Pexp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE-CFST column without preload | CCS1 [14] | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 53.0/72.2 | 1038 | 6@63 | - | - | 268.2 | 233.4 | 0.87 |

| CCS2 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 53.0/72.2 | 1025 | 6@80 | - | - | 266.5 | 233.6 | 0.88 | |

| CCS3 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 54.0/67.3 | 1377 | 6@47 | - | - | 242.7 | 240.0 | 0.99 | |

| CCS4 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 54.0/67.3 | 1365 | 6@60 | - | - | 233.5 | 239.0 | 1.02 | |

| CCS5 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 58.3/68.7 | 1708 | 8@65 | - | - | 252.2 | 248.9 | 0.99 | |

| CCS6 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 58.3/68.7 | 1697 | 6@65 | - | - | 249.7 | 246.4 | 0.99 | |

| CCS7 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 59.4/74.1 | 2045 | 8@56 | - | - | 242.2 | 250.7 | 1.04 | |

| CCS8 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 59.4/74.1 | 2040 | 6@50 | - | - | 260.7 | 247.5 | 0.95 | |

| CCS9 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 57.1/73.1 | 2201 | 8@48 | - | - | 262.7 | 245.9 | 0.94 | |

| CCS10 | 168 × 5.76 | 300 | 354 | 57.1/73.1 | 2188 | 6@44 | - | - | 280.7 | 241.5 | 0.86 | |

| CE-CFST column without preload | SC1 [2] | 60 × 2 | 150 | 353 | 33.6/52.4 | 0 | 6@100 | - | - | 42.6 | 46.5 | 1.09 |

| SC2 | 60 × 2 | 150 | 353 | 33.6/52.4 | 282 | 6@100 | - | - | 55.8 | 50.8 | 0.91 | |

| SC3 | 60 × 2 | 150 | 353 | 33.6/52.4 | 564 | 6@100 | - | - | 61.8 | 42.6 | 0.69 | |

| CFST column with first-stage preload | M1 [19] | 219 × 4 | - | 316 | -/22.3 | 900 | - | 0 | - | 76 | 66.3 | 0.87 |

| M2 | 219 × 4 | - | 316 | -/22.3 | 900 | - | 0.4 | - | 55 | 64.7 | 1.18 | |

| M3 | 219 × 4 | - | 316 | -/22.3 | 900 | - | 0.6 | - | 72 | 63.9 | 0.89 | |

| CE-CFST column with second-stage preload | S-1 [16] | 84.4 × 2.5 | 202 × 205 | 274 | 42.1/85.5 | 670 | 5@50 | - | 0.3 | 97 | 115.2 | 1.19 |

| S-2 | 84.4 × 2.5 | 200 | 274 | 53.8/85.5 | 870 | 5@50 | - | 0.31 | 146 | 145.8 | 1.00 | |

| S-3 | 84.4 × 2.5 | 200 | 274 | 53.2/85.5 | 1063 | 5@50 | - | 0.28 | 166 | 142.8 | 0.86 | |

| S-4 | 89 × 5 | 200 | 274 | 72.0/85.5 | 1081 | 5@50 | - | 0.3 | 169 | 164.2 | 0.97 |

| Specimen | n | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 198.8 | 194.8 | 0.98 |

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 193.9 | 193.9 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 193.6 | 189.8 | 0.98 |

| 4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 179.6 | 176.04 | 0.98 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 197.1 | 193.1 | 0.98 |

| 6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.016 | 0.034 | 191.7 | 187.9 | 0.98 |

| 7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 187.4 | 183.6 | 0.98 |

| 8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.022 | 0.045 | 197.2 | 193.3 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, M.; Tu, B.; Mao, E. Numerical Analysis on Seismic Performance of Concrete-Encased CFST Columns with Two-Stage Initial Stresses. Buildings 2025, 15, 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234379

Zheng M, Tu B, Mao E. Numerical Analysis on Seismic Performance of Concrete-Encased CFST Columns with Two-Stage Initial Stresses. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234379

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Min, Bing Tu, and Enyu Mao. 2025. "Numerical Analysis on Seismic Performance of Concrete-Encased CFST Columns with Two-Stage Initial Stresses" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234379

APA StyleZheng, M., Tu, B., & Mao, E. (2025). Numerical Analysis on Seismic Performance of Concrete-Encased CFST Columns with Two-Stage Initial Stresses. Buildings, 15(23), 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234379