Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance Instability of an Arch-Type Structure Under a Vertical Base-Excitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

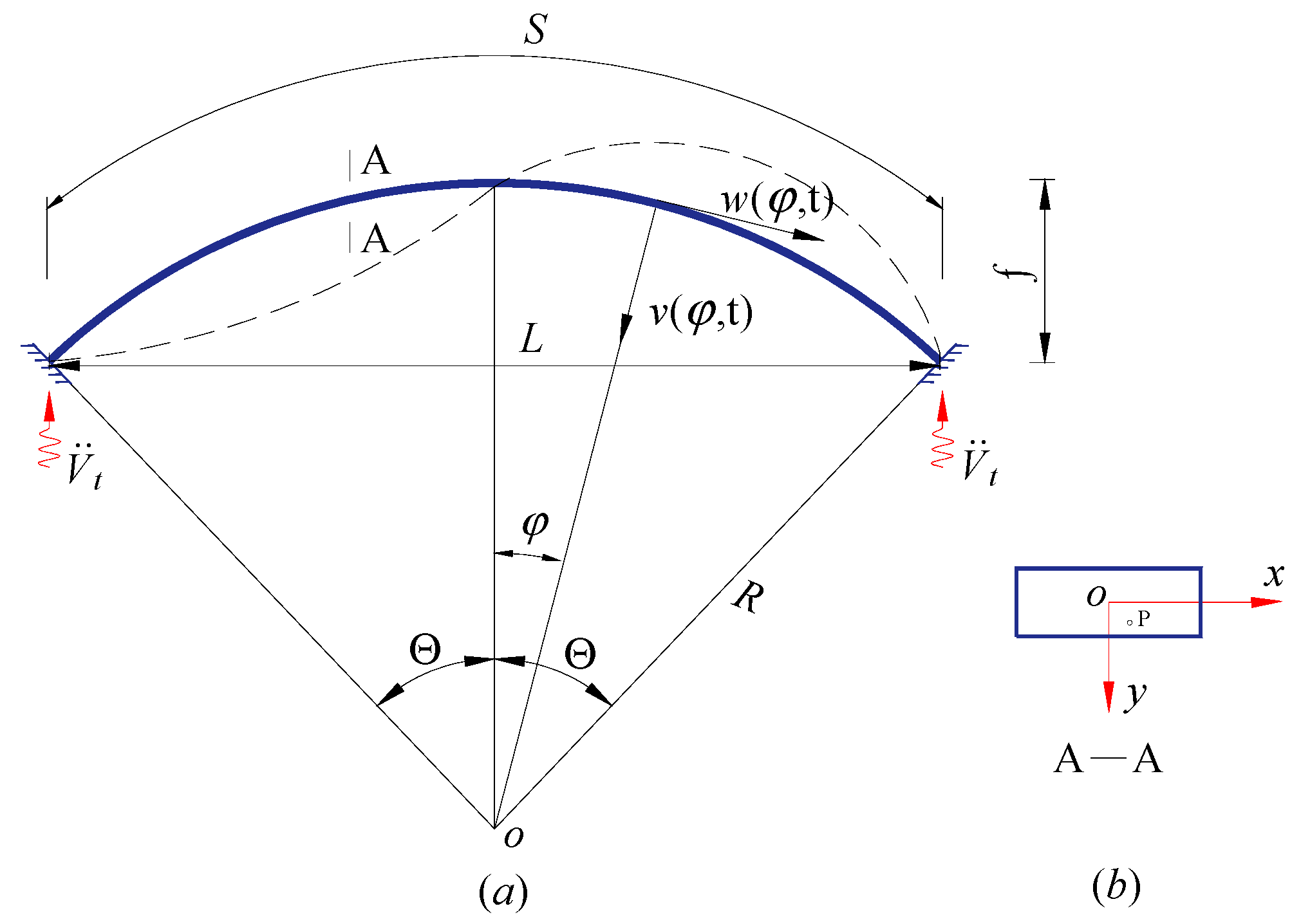

2. Mathematical Formulations

2.1. In-Plane Kinematic Equation

2.2. Solution to the Kinematic Equation

2.3. Instability of Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance

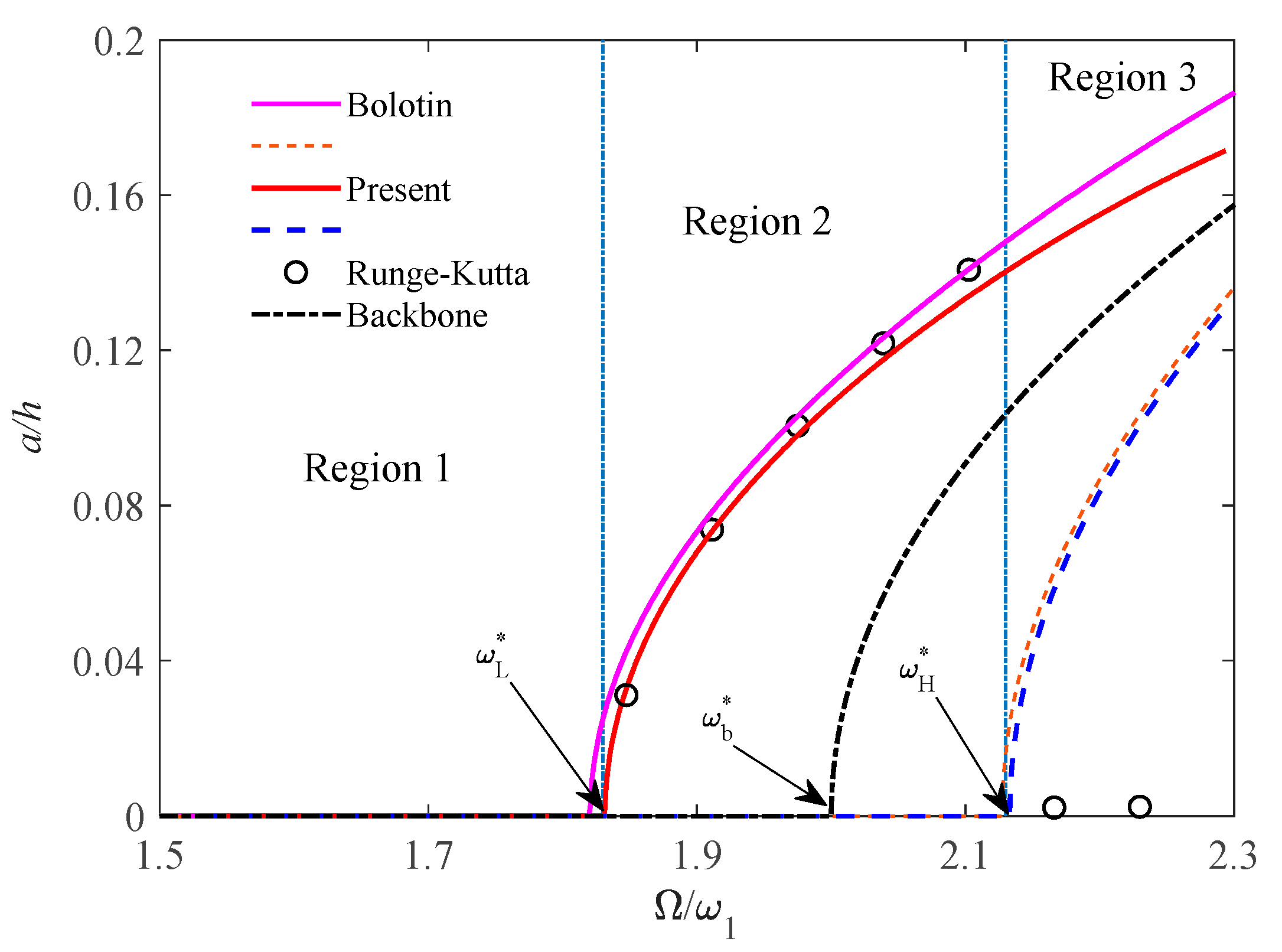

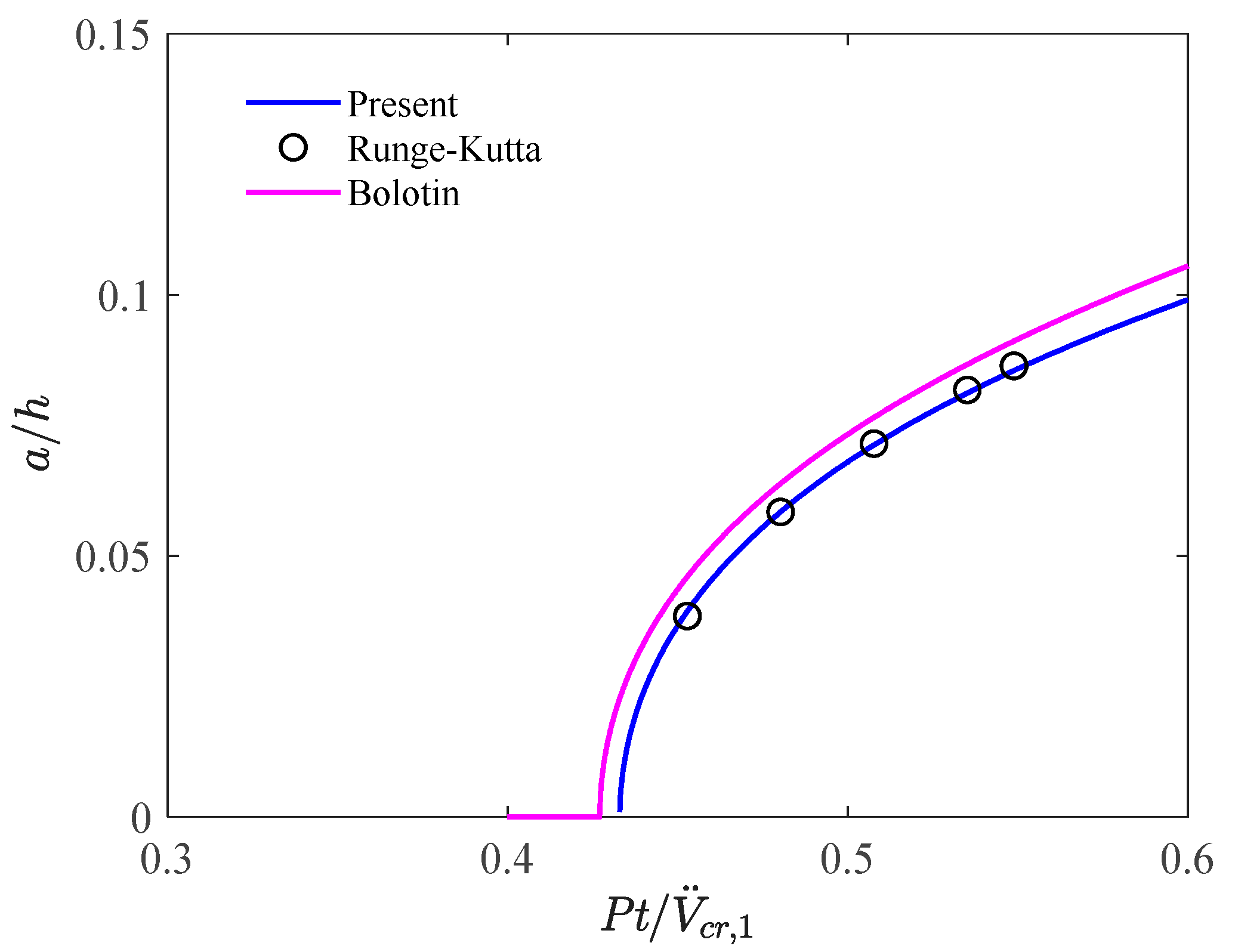

3. Validation

3.1. Fundamental Frequency

3.2. Frequency– and Force–Response Curves

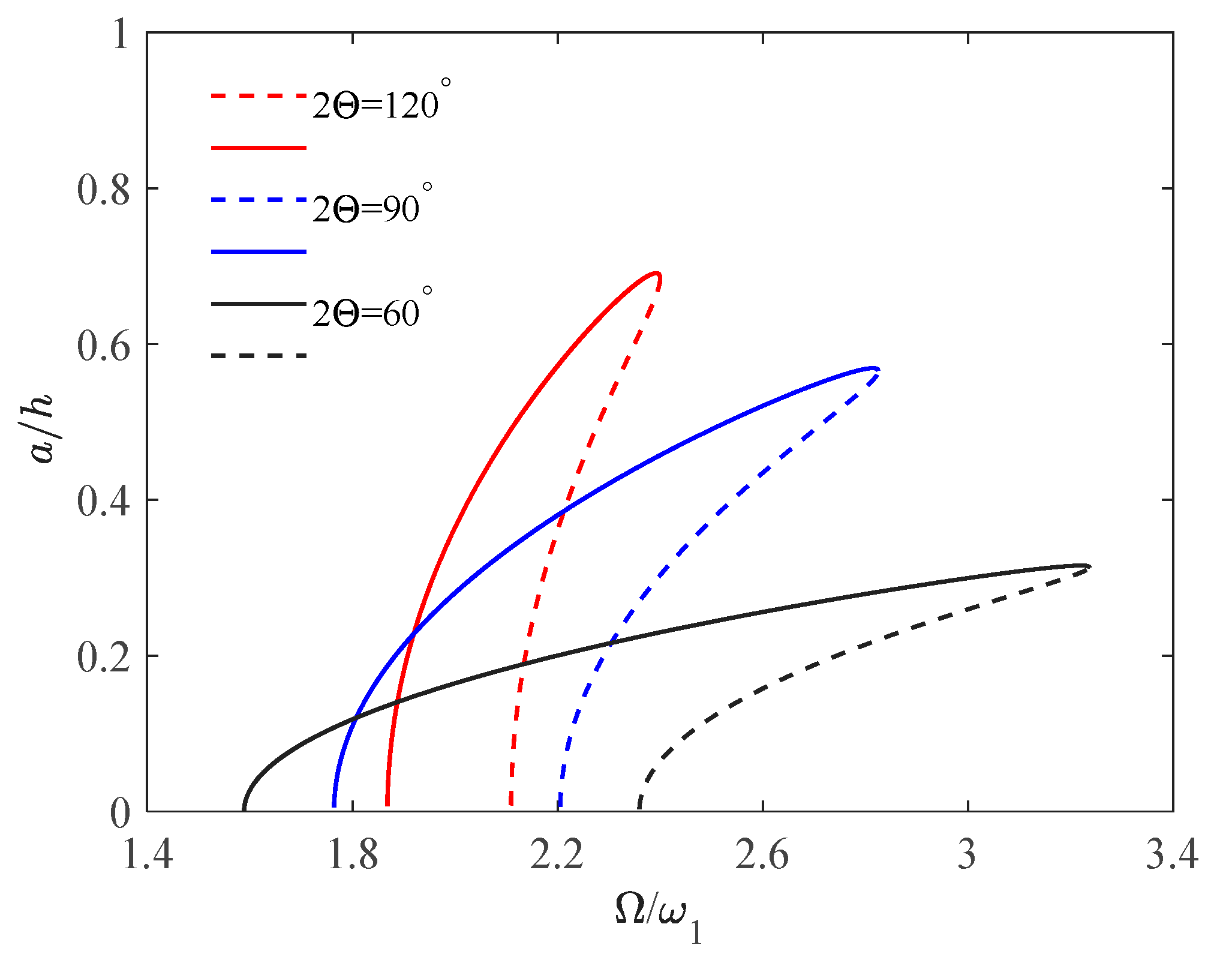

4. Discussion

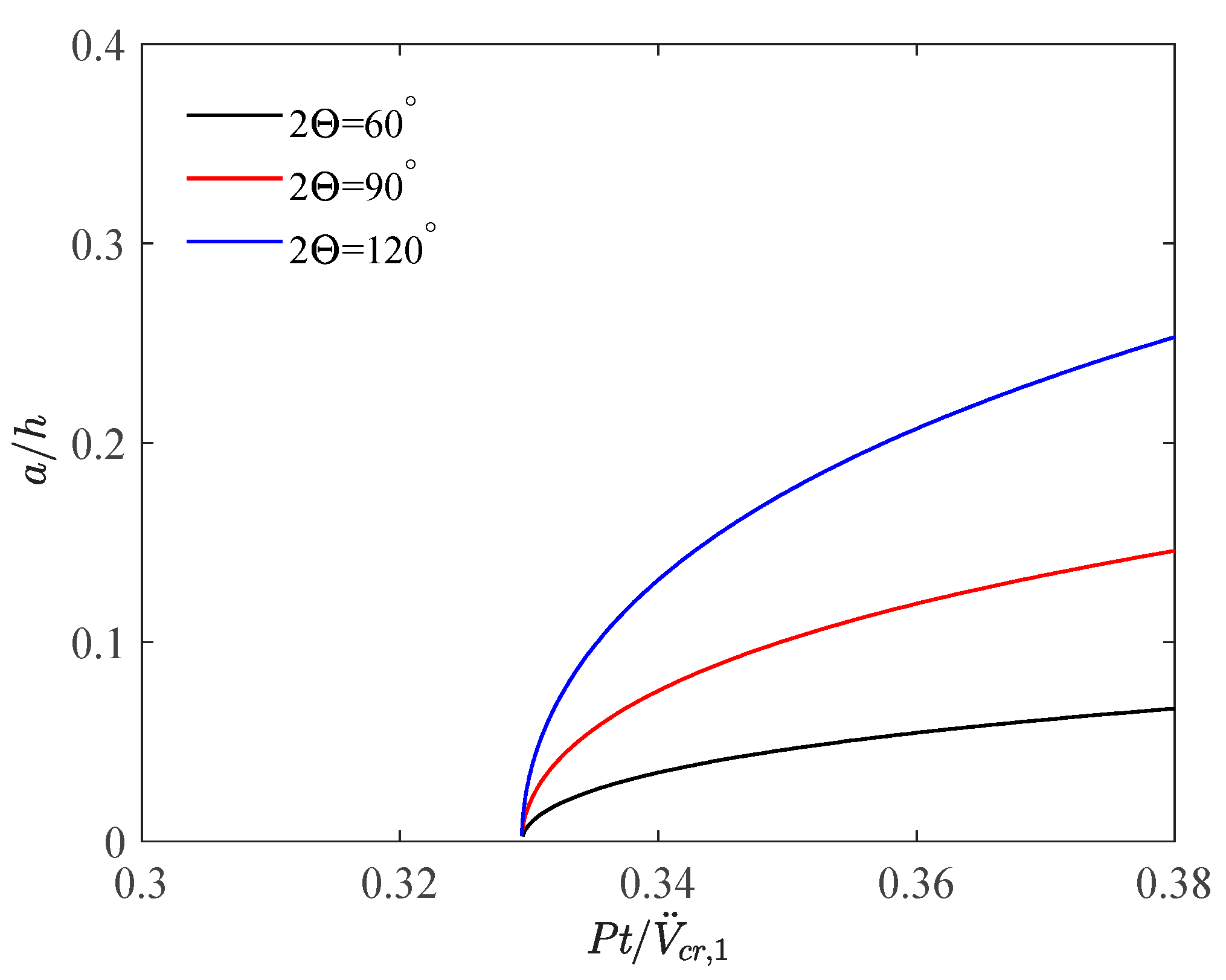

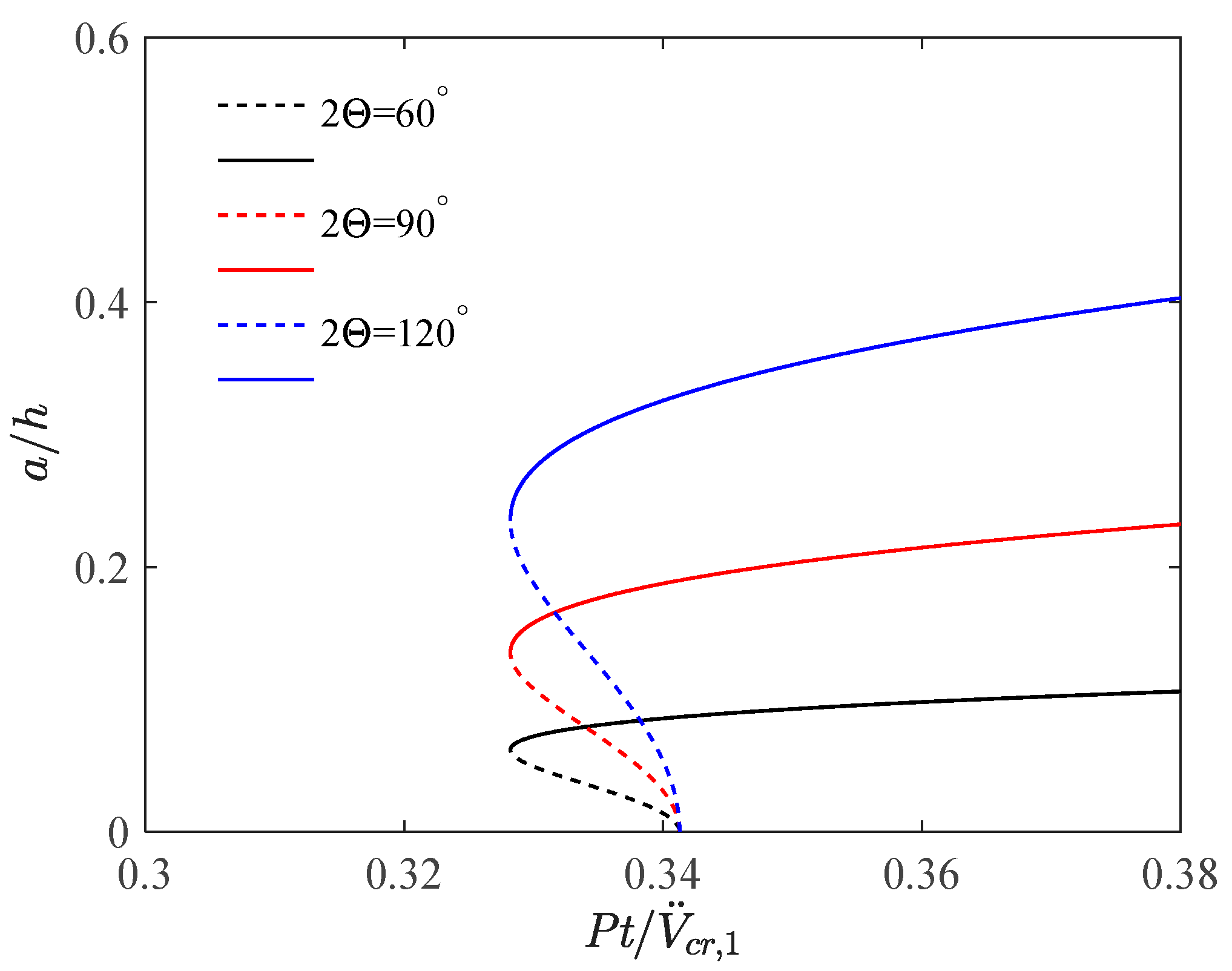

4.1. Effect of Included Angle

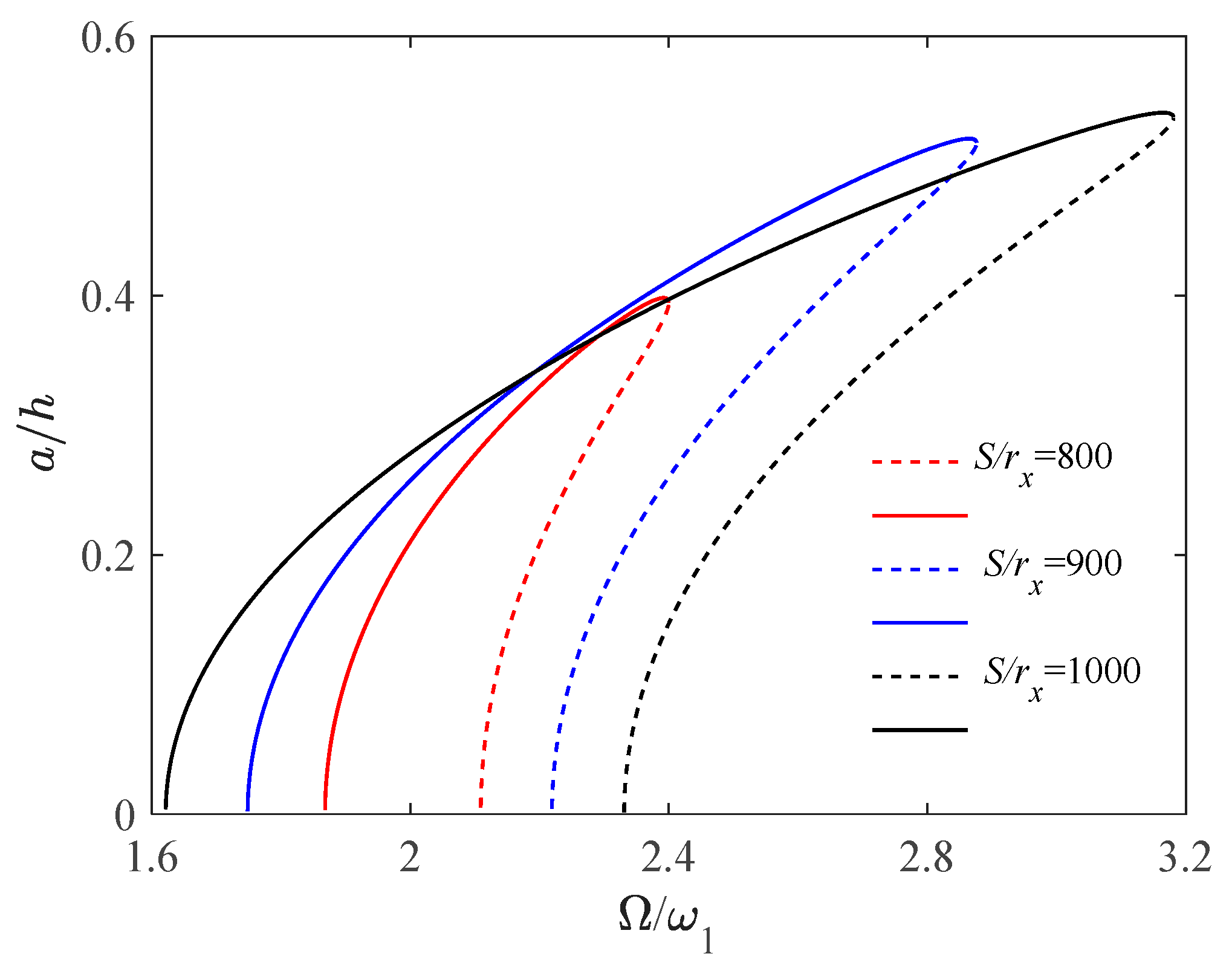

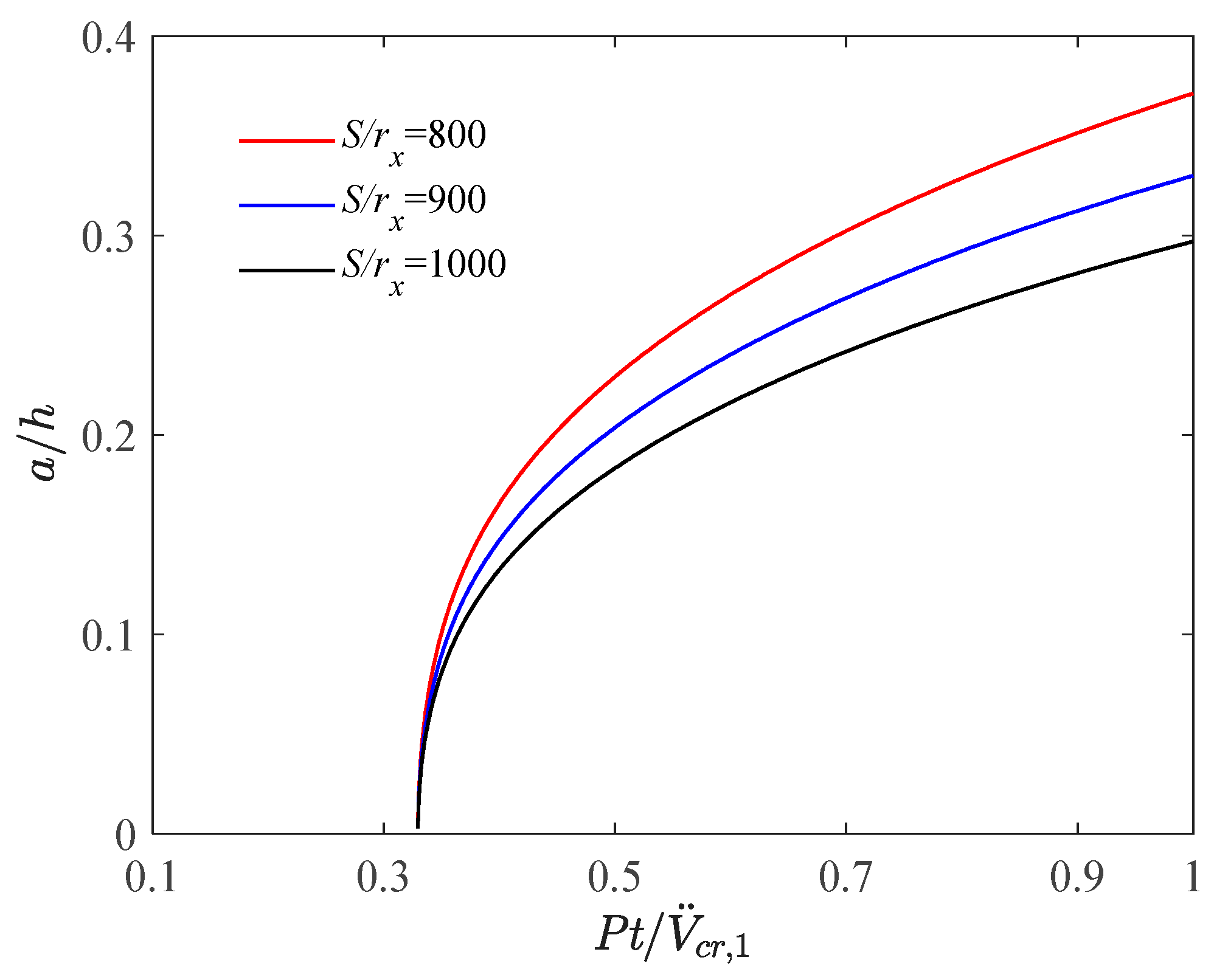

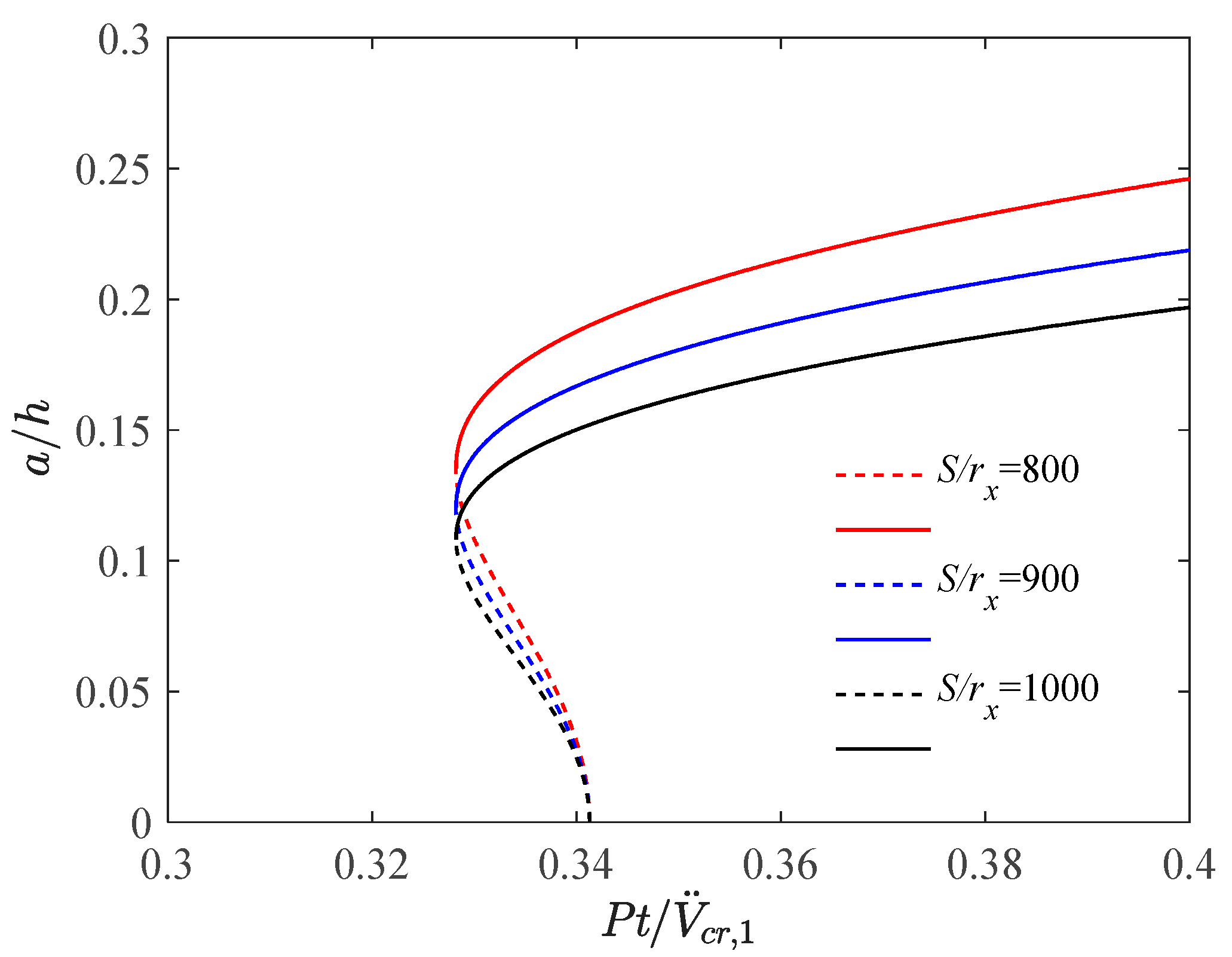

4.2. Effect of Slenderness Ratio

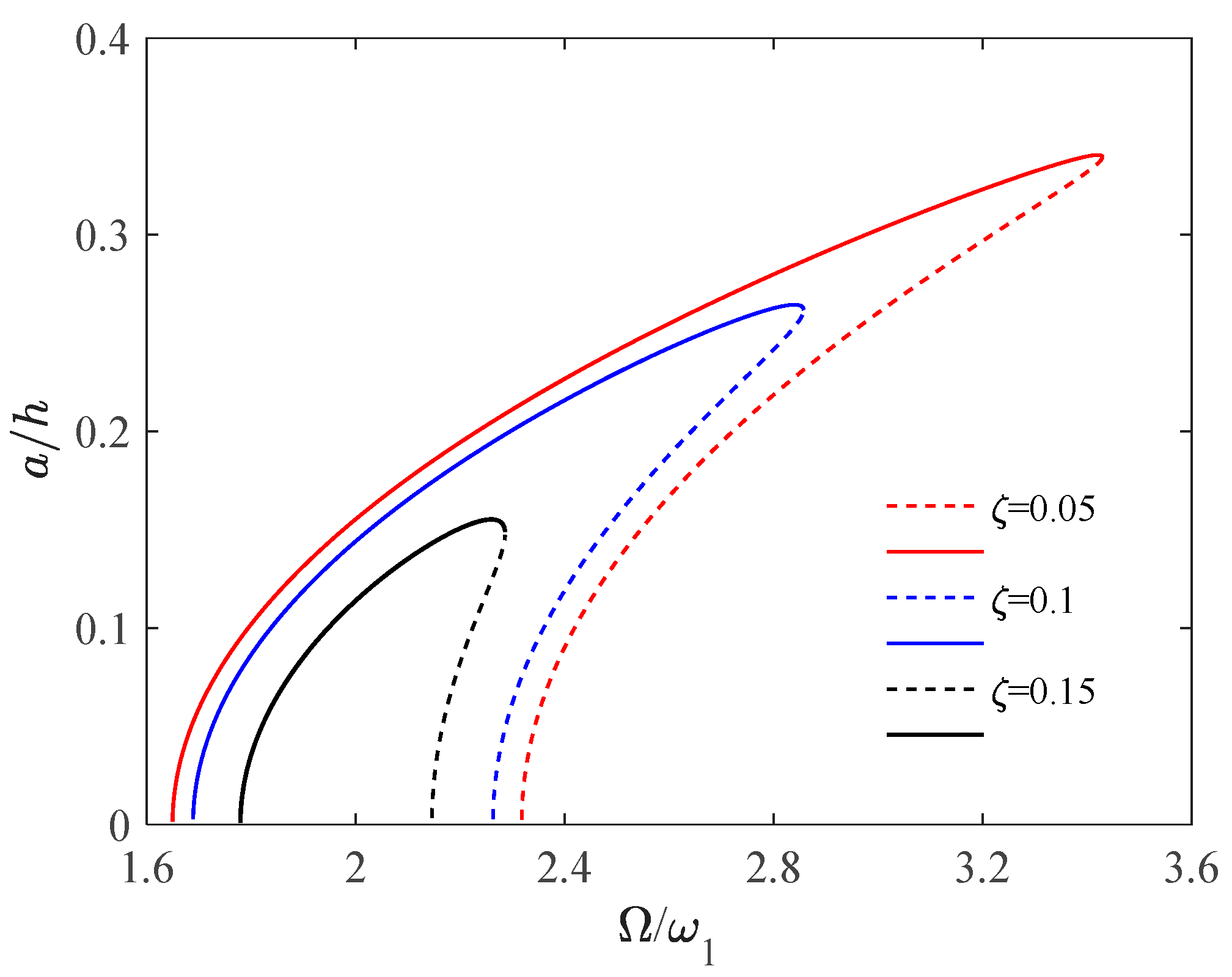

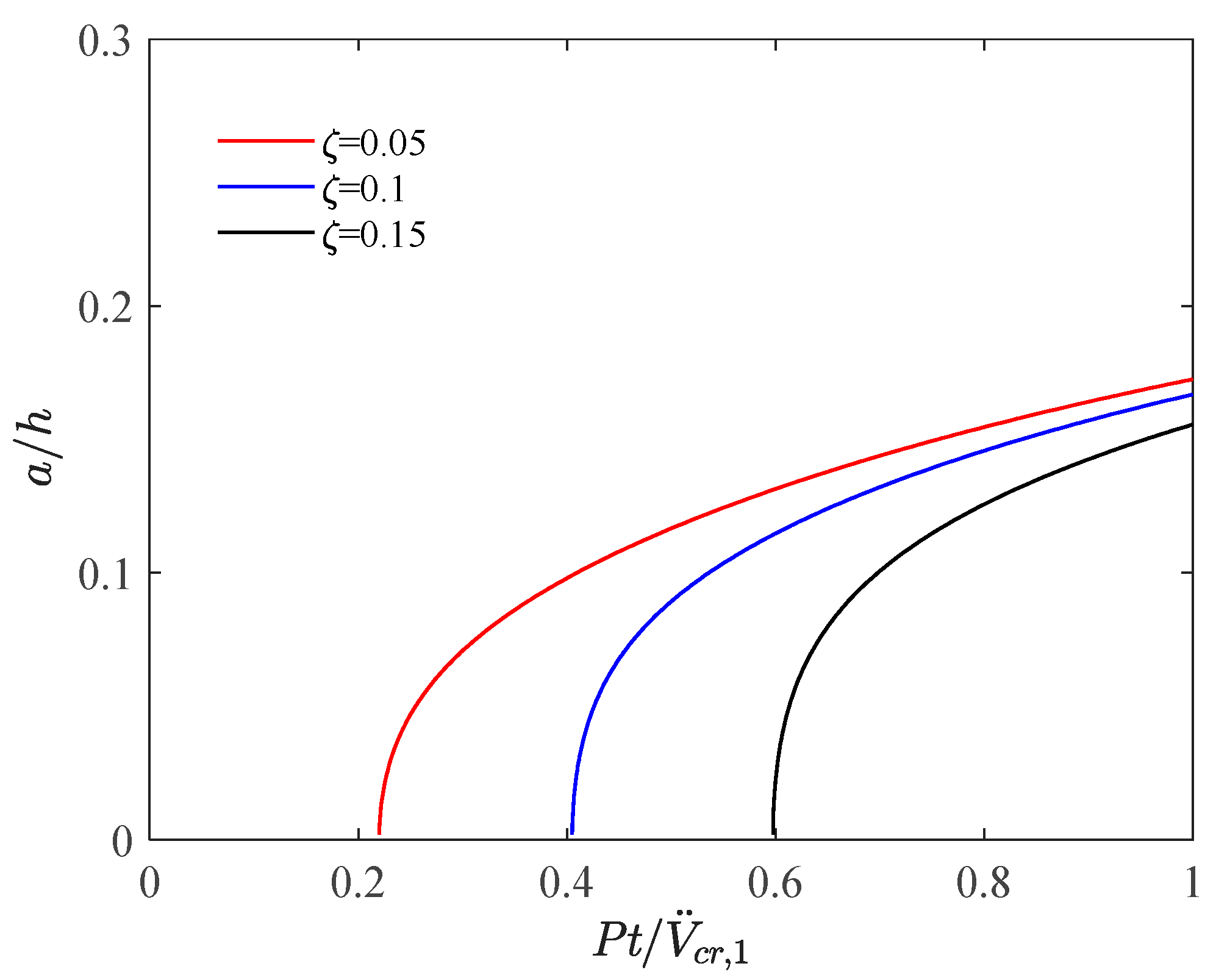

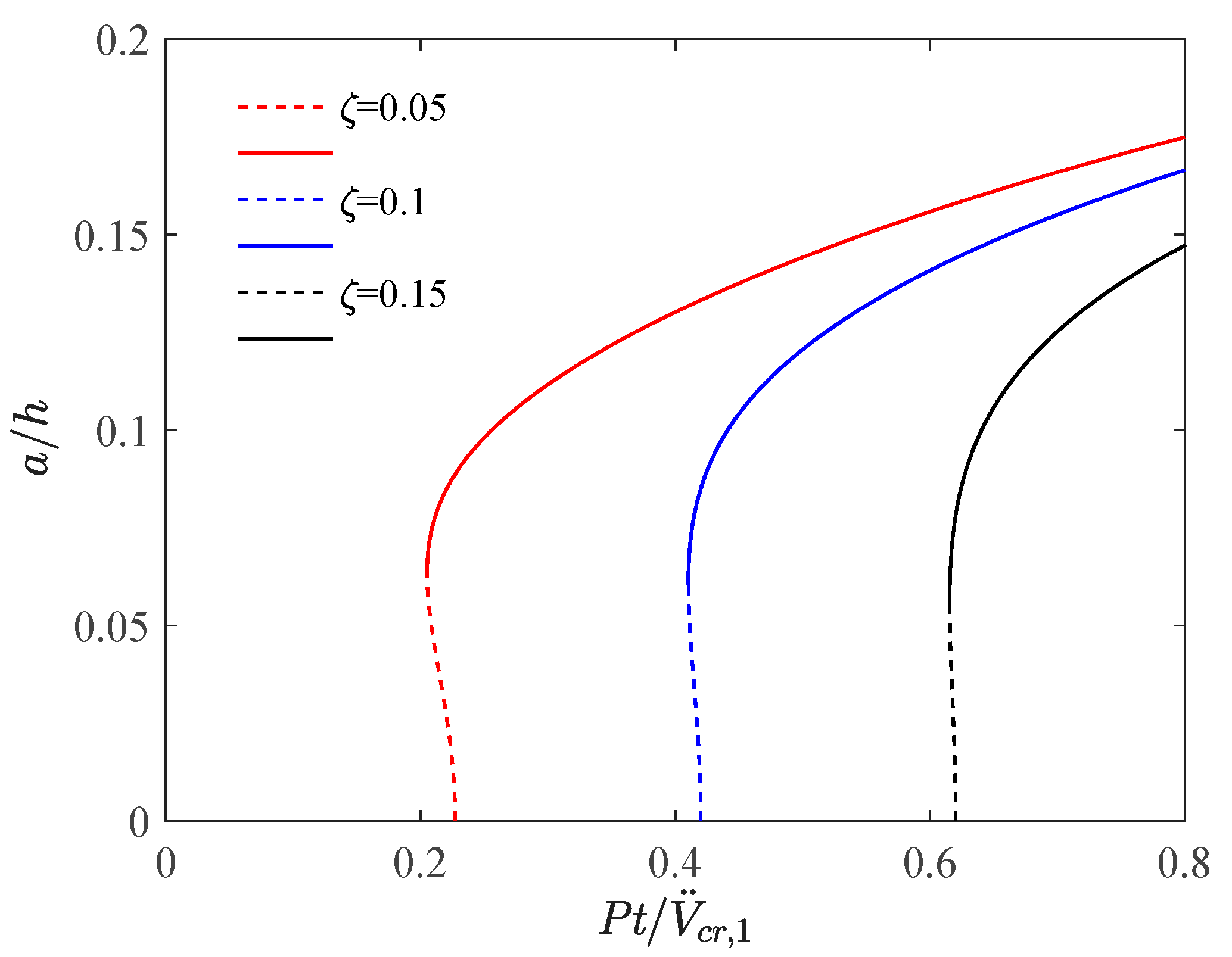

4.3. Effect of Damping Ratio

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, H.W.; Liu, L.L.; Liu, A.R.; Pi, Y.L.; Bradford, M.A.; Huang, Y.H. Effects of movement and rotation of supports on nonlinear instability of fixed shallow arches. Thin Wall. Struct. 2020, 155, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alneamy, A.M. Dynamic snap-through motion and chaotic attractor of electrostatic shallow arch micro-beams. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 182, 114777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Zheng, J.X.; Sun, Q.; He, H.T. Nonlinear structural stability performance of pressurized thin-walled FGM arches under temperature variation field. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2019, 113, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.C.; Liu, A.R.; Pi, Y.L.; Fu, J.Y.; Gao, Z.K. Nonlinear dynamic buckling of fixed shallow arches under impact loading: An analytical and experimental study. J. Sound Vib. 2020, 487, 115622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, A.R.; Zhang, Z.X.; Bradford, M.A.; Yang, J. Nonlinear vibration of pinned FGP-GPLRC arches under a transverse harmonic excitation: A theoretical study. Thin Wall. Struct. 2023, 192, 111099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.L.; Bradford, M.A. Nonlinear dynamic buckling of pinned–fixed shallow arches under a sudden central concentrated load. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 73, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.L.; Bradford, M.A. Multiple unstable equilibrium branches and non-linear dynamic buckling of shallow arches. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2014, 60, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Yang, Z.C.; Bradford, M.A.; Pi, Y.L. Nonlinear dynamic buckling of fixed shallow arches under an arbitrary step radial point load. J. Eng. Mech. 2018, 144, 04018012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Exploration of the encased nanocomposites functionally graded porous arches: Nonlinear analysis and stability behavior. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 82, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.H.; Bu, G.B.; Ou, Z.H.; Li, Z.H. Nonlinear in-plane instability of the confined FGP arches with nanocomposites reinforcement under radially-directed uniform pressure. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, L.P. Nonlinear stability analysis of FGM shallow arches under an arbitrary concentrated radial force. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2020, 16, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Babaei, H. Nonlinear vibration and buckling analyses of sandwich arch with titanium alloy face sheets and a porosity-dependent GPLRC core. Acta Mech. 2024, 235, 5431–5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.C.; Barbaros, I.; Sahmani, S.; Abdussalam Nuhu, A.; Safaei, B. Size-dependent nonlinear thermomechanical in-plane stability of shallow arches at micro/nano-scale including nonlocal and couple stress tensors. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 52, 3229–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.C.; Liu, A.R.; Yang, J.; Lai, S.K.; Lv, J.G.; Fu, J.Y. Analytical prediction for nonlinear buckling of elastically supported fg-gplrc arches under a central point load. Materials 2021, 14, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaei, H.; Eslami, M.R. Study on nonlinear vibrations of temperature-and size-dependent FG porous arches on elastic foundation using nonlocal strain gradient theory. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.Z.; Guo, T.D.; Kang, H.J.; Zhao, Y.Y. Nonlinear vibration analysis of a shallow arch coupled with an elastically constrained rigid body. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 10769–10789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.L.; Liu, A.R.; Fu, J.Y.; Pi, Y.L.; Deng, J.; Xie, Z.Y. Analytical and experimental studies on out-of-plane dynamic parametric instability of a circular arch under a vertical harmonic base excitation. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 500, 116011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.X.; Liu, A.R.; Deng, J.; Fu, J.Y. Out-of-plane dynamic parametric instability of circular arches with elastic rotational restraints under a localized uniform radial periodic load. Eng. Struct. 2023, 276, 115347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Lu, H.W.; Fu, J.Y.; Pi, Y.L.; Huang, Y.Q.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.W. Analytical and experimental studies on out-of-plane dynamic instability of shallow circular arch based on parametric resonance. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 87, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.L.; Liu, A.R.; Pi, Y.L.; Deng, J.; Fu, J.Y.; Gao, W. In-plane dynamic instability of a shallow circular arch under a vertical-periodic uniformly distributed load along the arch axis. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 189, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, A.R.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Wu, T.B.; Yang, J. A theoretical and experimental study on in-plane parametric resonance of laminated composite circular arches under a vertical base excitation. Compos. Struct. 2023, 304, 116398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, A.R.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhong, Z.L. In-plane dynamic instability of functionally graded porous arches reinforced by graphene platelet under a vertical base excitation. Compos. Struct. 2022, 293, 115705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Yang, Z.C.; Lu, H.W.; Pi, Y.L. Experimental and analytical investigation on the in-plane dynamic instability of arches owing to parametric resonance. J. Vib. Control 2018, 24, 4419–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Y.; Yang, Z.C.; Kitipornchai, S.; Yang, J. Dynamic instability of functionally graded porous arches reinforced by graphene platelets. Thin. Wall. Struct. 2020, 147, 106491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.Q.; Mao, X.Y.; Ding, H.; Ji, J.C.; Chen, L.Q. Nonlinear vibrations of a slightly curved beam with nonlinear boundary conditions. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 168, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedettini, F.; Alaggio, R.; Zulli, D. Nonlinear coupling and instability in the forced dynamics of a non-shallow arch: Theory and experiments. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 68, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakad, H.M.; Sedighi, H.M.; Younis, M.I. One-to-one and three-to-one internal resonances in MEMS shallow arches. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 12, 051025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.Q.; Chen, Y.S.; Chen, F.Q. Global bifurcation analysis and chaos of an arch structure with parametric and forced excitation. Mech. Res. Commun. 2010, 37, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.Q.; Chen, F.Q. Homoclinic orbits in a shallow arch subjected to periodic excitation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 78, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtouki, A.; Lakrad, F.; Belhaq, M. Quasi-periodic bursters and chaotic dynamics in a shallow arch subject to a fast–slow parametric excitation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 99, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakrad, F.; Chtouki, A.; Belhaq, M. Nonlinear vibrations of a shallow arch under a low frequency and a resonant harmonic excitations. Meccanica 2016, 51, 2577–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.; Su, K.L.R.; Lee, Y.Y.R.; Chen, S. Various bifurcation phenomena in a nonlinear curved beam subjected to base harmonic excitation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2018, 28, 1830023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotin, V.V. The Dynamic Stability of Elastic Systems, 1st ed.; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK,, 1964; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.L.; Liu, A.R.; Guo, Y.H.; Xu, X.B.; Deng, J.; Yang, J. Sub-harmonic and simultaneous resonance instability of a thin-walled arch under a vertical base excitation at two frequencies. Thin Wall. Struct. 2023, 191, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.L.; Zhong, Z.L.; Xu, X.B.; Li, J.H.; Dong, Q.X.; Deng, J. In-plane simultaneous resonance instability behaviors of a fixed arch under a two-frequency radial uniformly distributed excitation. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2025, 174, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.L.; Trahair, N.S. Non-linear buckling and postbuckling of elastic arches. Eng. Struct. 1998, 20, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, S.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Non-linear response of buckled beams to 1:1 and 3:1 internal resonances. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2013, 52, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.L.; Bradford, M.A.; Uy, B. In-plane stability of arches. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2002, 39, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Present | FEM | Error | Present | FEM | Error | Present | FEM | Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Θ () | 53.740 | 53.740 | 0% | 53.740 | 53.740 | 0% | 53.740 | 53.740 | 0% | |

| 2Θ () | 22.625 | 22.628 | 0.01% | 22.625 | 22.628 | 0.01% | 22.625 | 22.628 | 0.01% | |

| 2Θ () | 11.848 | 11.851 | 0.03% | 11.848 | 11.851 | 0.03% | 11.848 | 11.851 | 0.03% | |

| Present | FEM | Error | Present | FEM | Error | Present | FEM | Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Θ () | 717.29 | 700.96 | 2.33% | 716.89 | 700.56 | 2.33% | 716.75 | 700.45 | 2.33% | |

| 2Θ () | 925.35 | 904.56 | 2.30% | 925.14 | 904.37 | 2.30% | 925.06 | 904.26 | 2.30% | |

| 2Θ () | 976.96 | 956.85 | 2.10% | 976.84 | 956.73 | 2.10% | 976.80 | 956.71 | 2.10% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, Z.; Xu, X.; Shen, F.; Yao, Z.; Xiao, W. Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance Instability of an Arch-Type Structure Under a Vertical Base-Excitation. Buildings 2025, 15, 4356. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234356

Zhong Z, Xu X, Shen F, Yao Z, Xiao W. Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance Instability of an Arch-Type Structure Under a Vertical Base-Excitation. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4356. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234356

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Zilin, Xiaobin Xu, Fulin Shen, Zhiyong Yao, and Weiguo Xiao. 2025. "Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance Instability of an Arch-Type Structure Under a Vertical Base-Excitation" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4356. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234356

APA StyleZhong, Z., Xu, X., Shen, F., Yao, Z., & Xiao, W. (2025). Nonlinear Subharmonic Resonance Instability of an Arch-Type Structure Under a Vertical Base-Excitation. Buildings, 15(23), 4356. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234356