Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods for the Mechanical Performance of SFRC Segments

2.1. Experimental Analysis

| Experiment Subject | Test Type/Method | AE | DIC | Researcher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single SFRC segment | Settlement response test/Punching test | Abbas et al. [23] | ||

| Crack test | Zhang et al. [43] | |||

| Thrust load test | Nehdi et al. [44] | |||

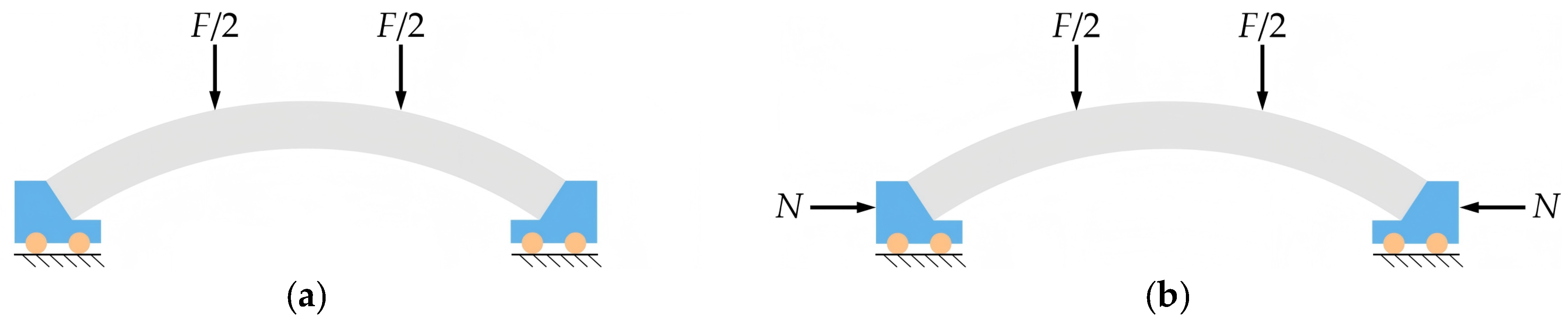

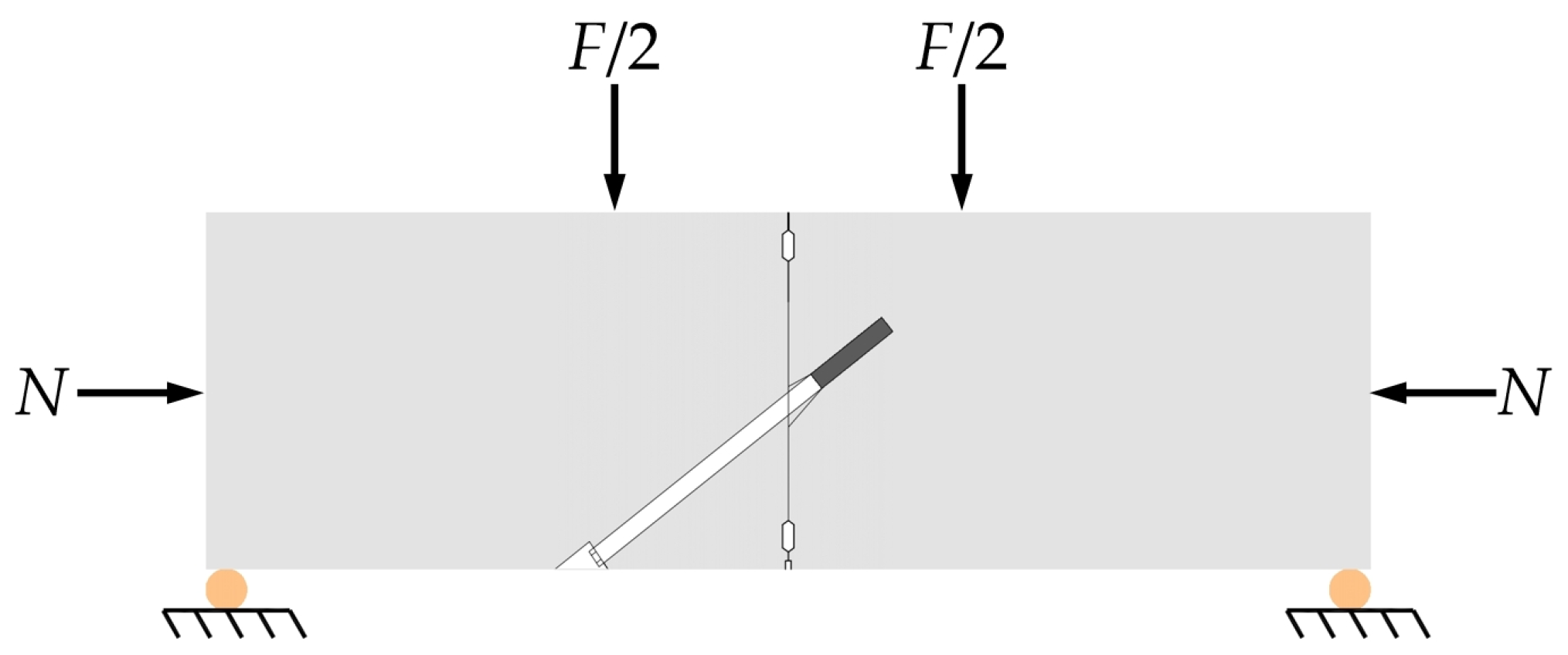

| Biaxial loading method | Meng et al. [21] | |||

| SFRC segment joints | Biaxial loading joint bending test | Feng et al. [25] | ||

| Biaxial loading joint bending test | Gong et al. [26] | |||

| Biaxial loading joint bending test | Yan et al. [28] | |||

| Biaxial loading joint bending test | Zhou et al. [29] | |||

| Radial joint test | Caratelli et al. [27] | |||

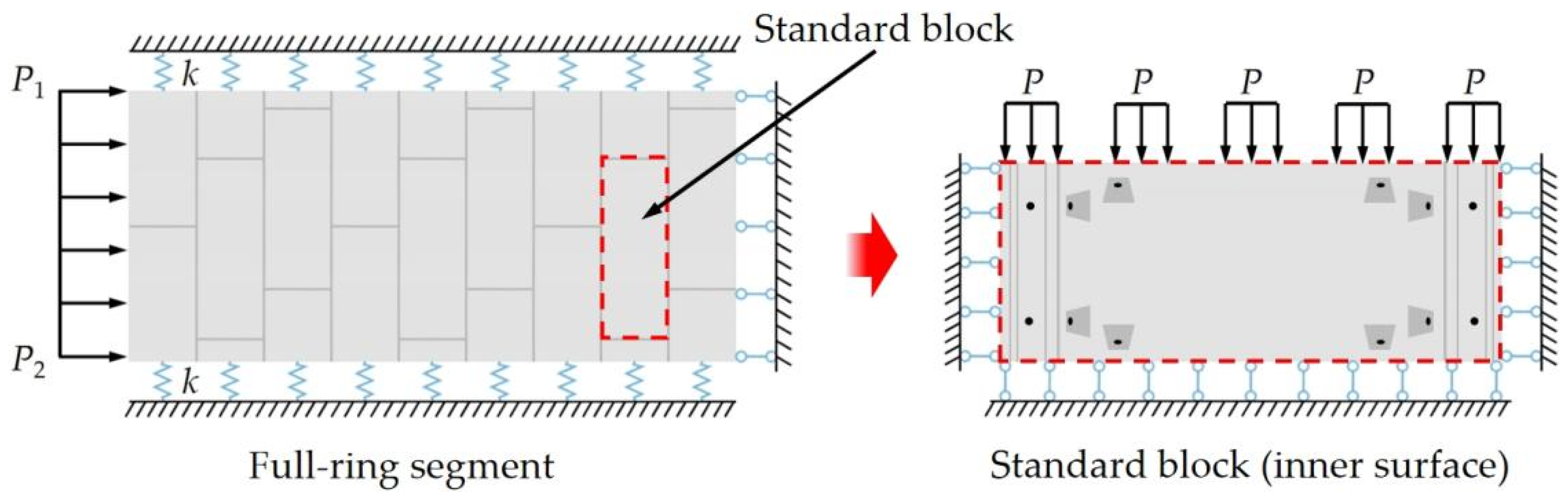

| Full ring SFRC segment | Full-scale loading test | Zhang et al. [30] | ||

| SFRC beam | Four-point bending test | √ | Aggelis et al. [42] | |

| Four-point bending test | √ | Li et al. [45] | ||

| Four-point bending test | √ | Cardoso et al. [36] | ||

| Four-point bending test | Li et al. [46] | |||

| Four-point bending test | Venkateshwaran et al. [47] | |||

| Four-point bending test | √ | √ | Zhou et al. [38] | |

| Four-point bending test | Zhang et al. [48] | |||

| Three-point bending test | √ | √ | Ashraf et al. [37] | |

| Three-point bending test | √ | Yue et al. [49] | ||

| Three-point bending test | √ | Yue et al. [50] | ||

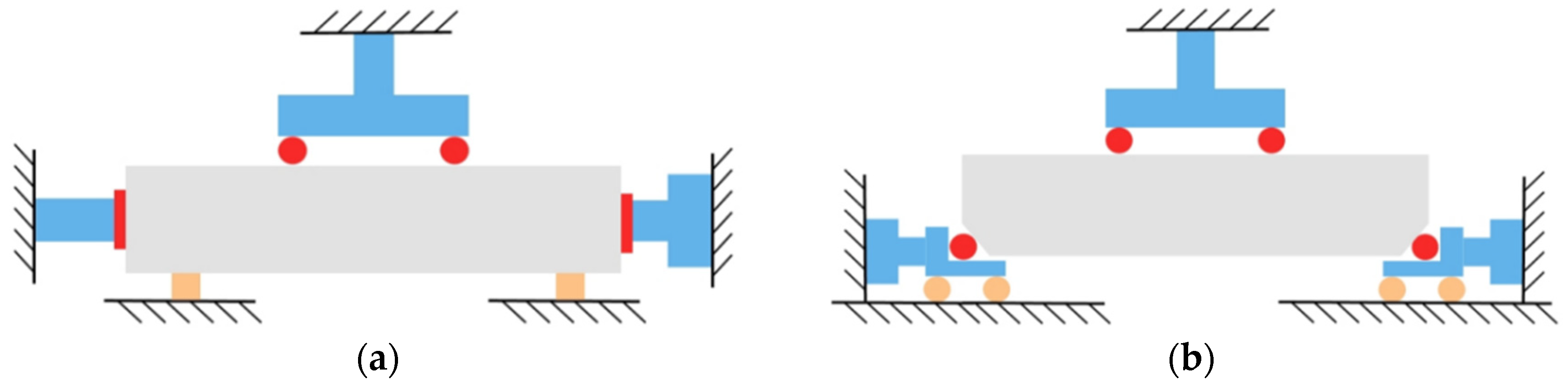

| Axially loaded simply supported beam method | Xu et al. [34] | |||

| Symmetric-inclination beam loading method | Ding et al. [35] |

2.2. Numerical Methods

2.2.1. Finite Element Method

| Researcher | Finite Element Software | Research Object | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAQUS | MIDAS GTS | FLAC 3D | DIANA 9.4.4 | ADINA | Single Segment | Segment Joints | Full Ring Segment | |

| Yang et al. [12] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Nogales et al. [16] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Avanaki et al. [17] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Yan et al. [52] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Liao et al. [51] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Zhang et al. [53] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Zhang et al. [54] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Qi et al. [55] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Mo et al. [57] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Yang et al. [56] | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Xu et al. [58] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Deng et al. [59] | √ | √ | ||||||

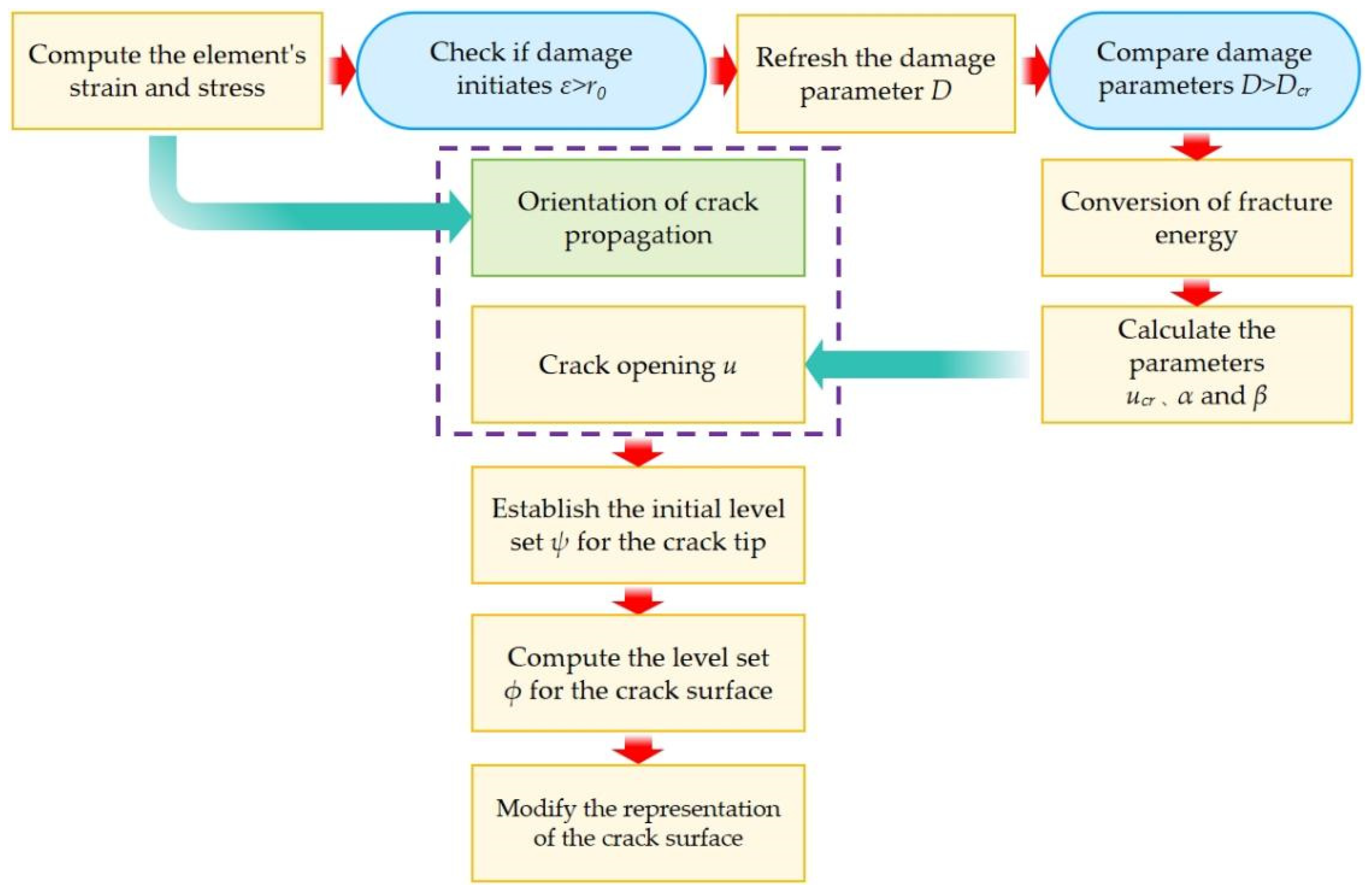

2.2.2. Extended Finite Element Method

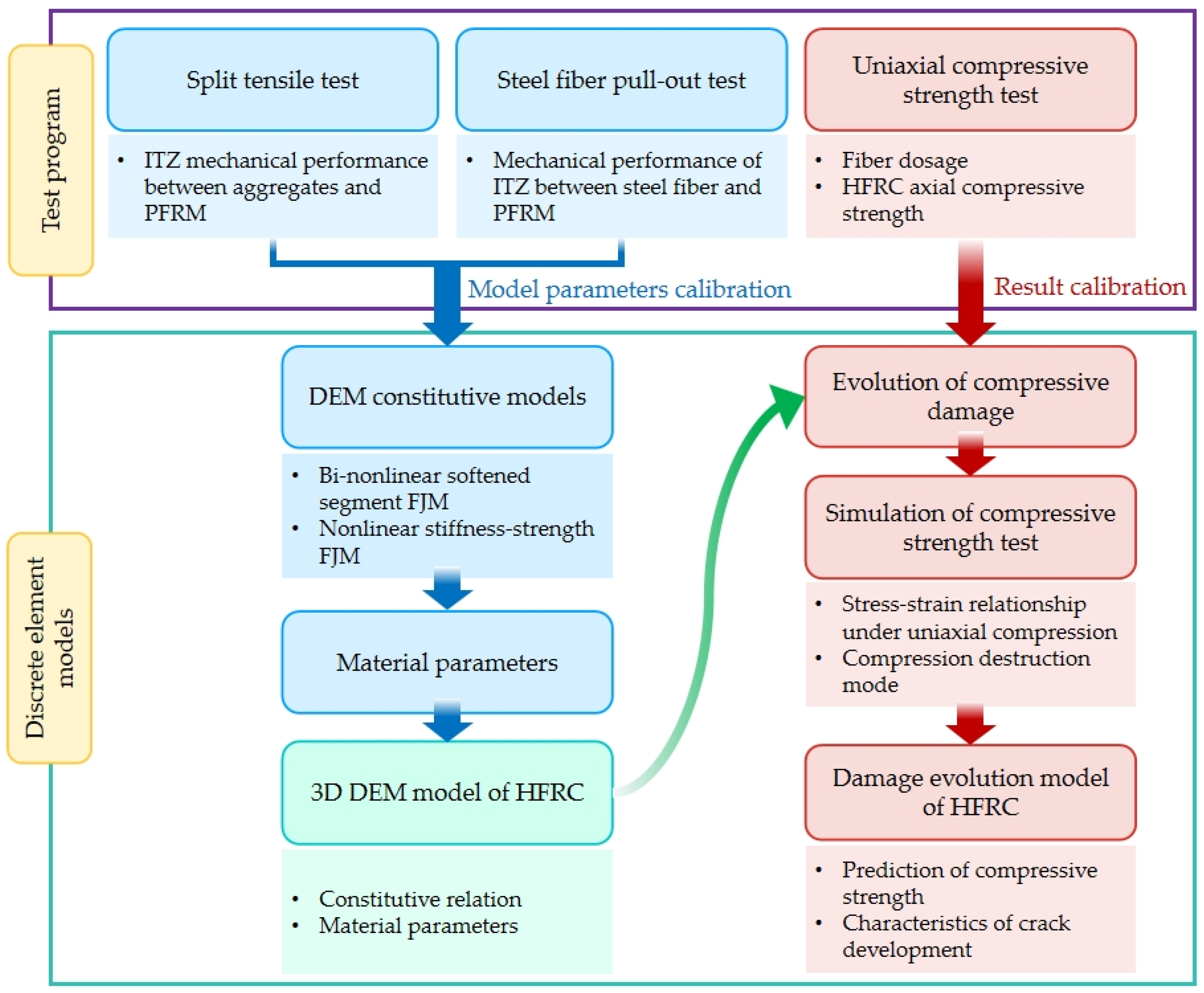

2.2.3. Discrete Element Method

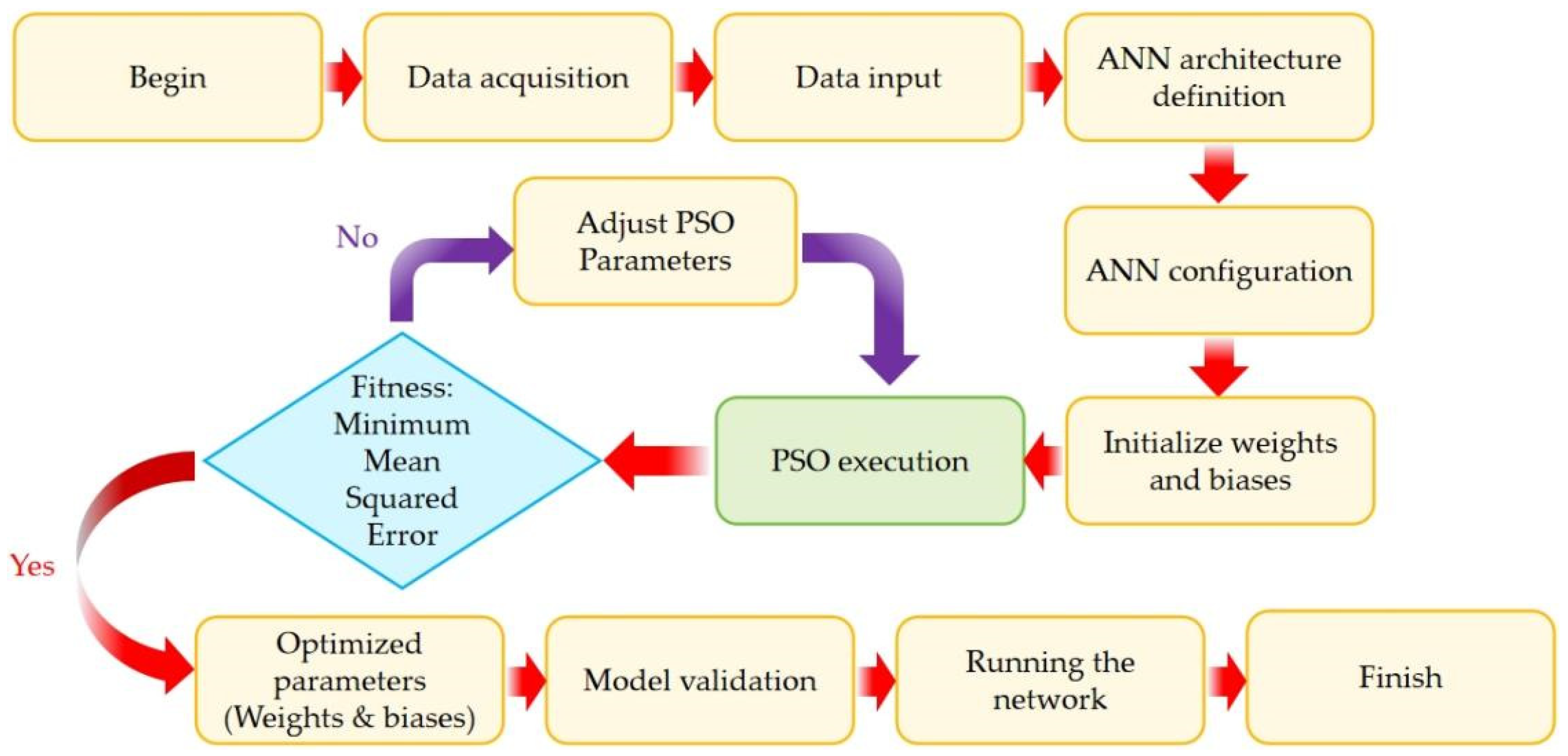

2.3. Application of Artificial Intelligence

3. Calculation Methods for SFRC Segment Structures

3.1. Bearing Capacity Calculation

3.1.1. Calculation Method of Normal Section Bearing Capacity

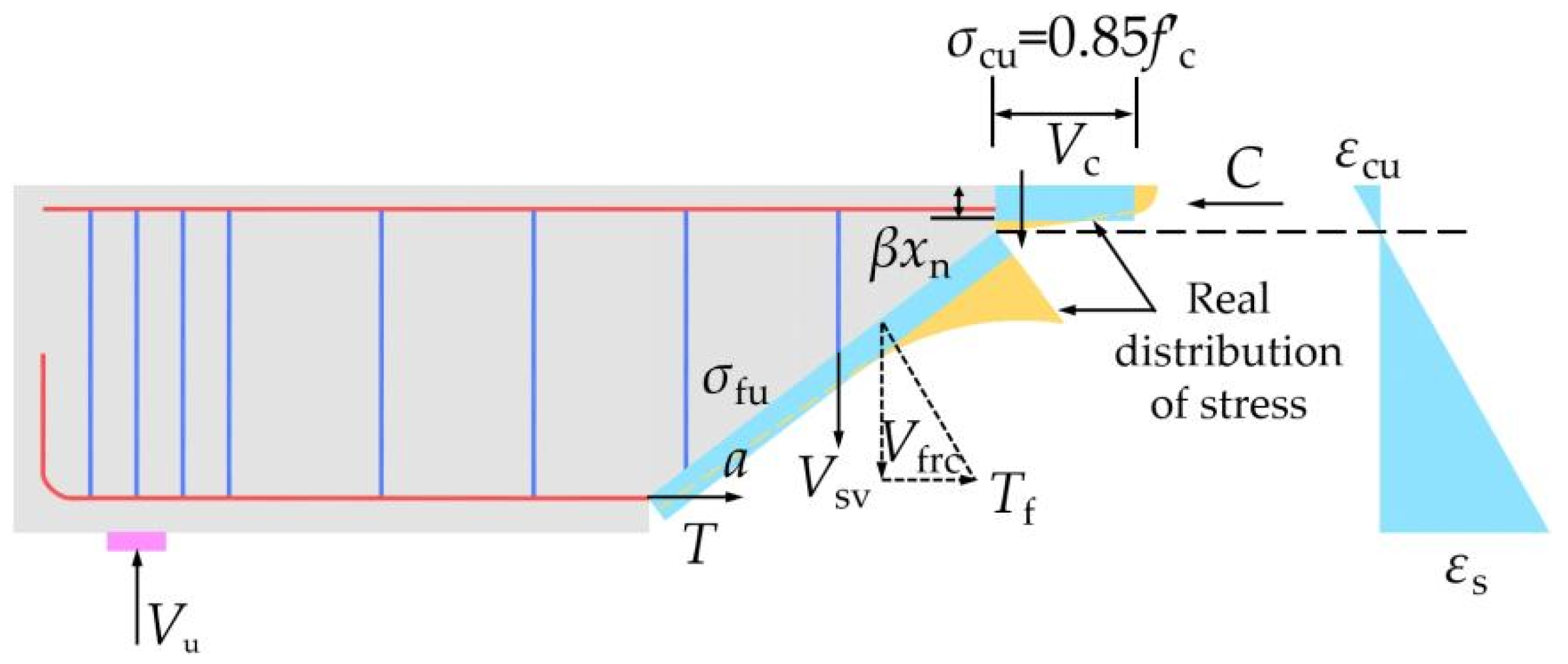

3.1.2. Calculation Method of Inclined Section Bearing Capacity

3.2. Calculation of Crack Width

4. Mechanical Performance Characteristics of SFRC Segments

4.1. Deformation and Failure Modes

4.2. Crack Development Characteristics

5. Factors Influencing Mechanical Performance

5.1. Matrix Strength

5.2. Steel Fibers

5.2.1. Steel Fiber Type

5.2.2. Steel Fiber Dosage

5.2.3. Steel Fiber Aspect Ratio

6. Conclusions and Future Research Trends

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Experiments, numerical simulations, and artificial intelligence methods each have their own advantages and complement each other. The combination of advanced monitoring technologies such as DIC and AE in experiments can accurately capture the mechanisms of segment damage. Numerical methods are suitable for simulating multiple working conditions such as material nonlinearity and crack propagation, with both economy and flexibility. AI methods have achieved efficient and high-precision performance prediction and material design. The collaboration of the three has constructed a systematic research system from micro mechanisms to macro performance.

- (2)

- Compared with traditional RC segments, SFRC segments (especially R-SFRC segments) change their failure mode from brittle shear to ductile bending under the synergistic effect of steel rebars and steel fibers, significantly improving their bearing capacity, deformation capacity, and energy dissipation performance. The failure of the full-ring segments follows the three-stage evolution law of “elastic stage local plastic hinge formation overall mechanism development”. The bridging effect of steel fibers effectively suppresses the development of crack width and promotes the transformation of crack morphology from a single main crack to a distributed microcrack system.

- (3)

- Among the existing design methods, the coefficient correction method based on specifications (e.g., JGJ/T 465-2019) is simple to calculate but tends to be conservative. The mechanical modeling method based on material constitutive theory (e.g., Model Code 2010) is theoretically rigorous and can better reflect the contribution of steel fibers after cracking, but the parameters are complex and the computational cost is high. The current core challenge is how to develop a practical design model that integrates the random distribution of steel fibers and bridging effects while ensuring accuracy.

- (4)

- Matrix strength and steel fiber characteristics (type, dosage, aspect ratio) jointly affect the mechanical performance of SFRC segments, with the order of influence being matrix strength > steel fiber type > steel fiber aspect ratio > steel fiber dosage. The hooked-end and corrugated steel fibers exhibit excellent performance in shear resistance, crack control, and toughening. There is a reasonable range for the dosage and aspect ratio, and excessive dosage can easily lead to steel fiber aggregation and weaken the reinforcement effect.

6.2. Future Research Trends

- (1)

- Research on corrosion resistance and high durability of SFRC segments should be systematically advanced. SFRC segments exhibit better chloride and carbonation resistance than ordinary RC segments in an uncracked state, thanks to the inhibitory effect of three-dimensional discrete distribution of steel fibers on macroscopic battery corrosion, as well as the higher critical chloride ion threshold given to them by cold drawing process [133]. Experimental studies [134] have shown that even when high concentration NaCl solutions (such as 9%) are used during the preparation process, SFRC specimens can still maintain their basic mechanical and corrosion resistance performance. The recent research [135] on the performance of steel fiber reinforced materials in corrosive environments also provides a reference for the long-term performance evaluation of SFRC segments in harsh environments. In the future, the long-term performance of SFRC segments in corrosive environments should be systematically evaluated to promote their application in tunnel engineering in highly corrosive formations.

- (2)

- SFRC-based repair and reinforcement technology for existing tunnel segments warrants focused development. SFRC materials have good crack control and toughness recovery capabilities, making them suitable for the repair and reinforcement of existing tunnel segments. Research has shown that using steel fiber reinforced cement-based materials to reinforce concrete components can effectively change their failure modes and significantly improve their bearing capacity [136]. The advantages of fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete in terms of repair layer performance and interface bonding [137] also provide technical references for the application of SFRC materials in segment repair. In the future, the focus should be on studying the interface behavior, collaborative working mechanism, and long-term service performance between SFRC repair materials and existing concrete segments, and developing SFRC materials and construction processes suitable for tunnel segment repair.

- (3)

- Intelligent design and performance prediction methods for SFRC segments need to be established. Machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies provide a new approach for the refined design and performance prediction of SFRC segments. At present, AI methods such as artificial neural networks and deep learning have demonstrated advantages in SFRC material design, performance prediction, and damage identification [65,66,67,69]. In particular, the intelligent recognition technology based on sound signals and visual data [66,69] provides innovative solutions for non-destructive testing and performance evaluation of SFRC segments. In the future, an intelligent design system specifically designed for SFRC segments should be developed, and a performance prediction model that integrates multi-scale mechanisms should be established to accurately predict the long-term behavior of SFRC segments under complex load and environmental coupling effects, promoting the development of SFRC segments segment design towards intelligence and refinement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of SFRC Segment Structural Calculation Methods

| Ref. | Computing Formula | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| GB 50010-2010 [79] | N = α1 fc b x + fy′ As′ − fy As N e = α1 fc b x (h0 − x/2) + fy’ As’ (h0 − as’) | fc is the axial compressive design value of concrete. fy’ is the design value of compressive strength of ordinary steel rebar. fy is the design value of tensile strength of ordinary steel rebar. As is the cross-sectional area of the longitudinal ordinary steel rebar in the tension zone. As’ is the cross-sectional area of longitudinal ordinary steel rebar in compression zone. αs’ is the distance from the resultant force point of the longitudinal ordinary steel rebar in the compression zone to the compression edge of the section. |

| JGJ/T 465-2019 [78] | Nfu = ffc b x + fy’ As’ − fy As − fftu b xt Nfu e = ffc b x (h0 − x/2) + fy’ As’ (h0 − as’) − fftu b x (hx/2 − as) | Nfu is the design value of axial compressive bearing capacity of SFRC segments. ffc is the design value of axial compressive strength of SFRC. fftu is the tensile strength of equivalent rectangular stress pattern of SFRC in tension zone. xt is the height of the tension zone of the component. αs is the distance from the resultant point of longitudinal tensile non-prestressed steel rebar to the near side of the section. |

| Model code 2010 [81] | Nfu = η ffc λ x b/2 − ffc (h − x) b Mfu = ηffc λ x b/2 (h/2 − λx/2) + ffts (h − x) b (x/2) | Nfu is the design value of axial compression bearing capacity. η is a coefficient, when the concrete strength grade ≤ C50, take 0.8. ffc is the design value of axial compressive strength of SFRC. λ is a coefficient, when the concrete strength grade ≤ C50, take 1.0. Mfu is the design value of bending moment bearing capacity. ffts is slenderness ratio. |

| ACI 318R-14 [80] | Nfu = ϕ Nn = 0.7 [0.85 ffc x b/2 − σp xt b] Mfu = ϕ Mn = 0.7 [0.85 ffc (x/2) (h/2 − x/3) b + σp xt b (h − xt)/2] | ϕ is the influence coefficient considering the size effect and the uneven material of the component. Nn is the nominal of axial compression of SFRC. Mn is the nominal resistance of SFRC. σp is the ultimate tensile strength of SFRC bearing capacity limit state. |

| Xu et al. [34] | Nfu ≤ α ffc b x/2 − ffts b xt Nfu (e1 + h/2 − xt) ≤ α1 ffc b x (x/β1 − x/2) + ffts b xt (xt/2) ei = e0 + ea | ffc is the standard value of axial compressive strength of SFRC. ffts is the tensile strength characteristic value of SFRC segments under ultimate bearing capacity state. xt is the height of the tension zone of the component. ei is initial eccentricity. e0 is the distance from the point of axial force to the center of gravity of the section. ea is the additional eccentricity, which should be selected according to 6.2.5 of GB 50010-2010. |

| Li et al. [138] | Nu = α1 ffc b xc − σsf b xft + 0.87 fy’ As’ − fy As Nu e = α1 ffc b xc (h0 − x/2) + 0.87 fy’ As’ (h0 − as’) − αsf b xft (xft/2 − as) xft = (h − xc)/β1 e = ηns,u e0 + h/2 − as | α1 is the coefficient influenced by the compressive strength. fy’ is yield strength of the compressive steel rebar. xc is the depth of the compressive zone of concrete. xft is the depth of the tensile zone of concrete. β1 is the coefficient related to the depth of compression. |

| Zhou et al. [139] | Nfu ≤ fc b x/2 − σ3 b xt/2 Nfu (ei − h/2 + x) ≤ fc b x2/3 + σ3 b xt2/3 fc = Esc Ɛftu (x/xt) | fc is the actual compressive stress of concrete in compression zone. Esc is the elastic modulus of SFRC. Ɛftu is the ultimate state of bearing capacity under tension. |

| Ref. | Computing Formula | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| GB 50010-2010 [79] | Vfcs = Vfc + Vsv + 0.07 N Vfc = Vc (1 + βcw λf) Vc = 0.7 ft b h | Vfc is the design value of shear bearing capacity of SFRC. Vc is the shear bearing capacity of matrix concrete. Vsv is the design value of shear bearing capacity related to stirrups. βcw is the influence coefficient of steel fiber on the shear bearing capacity of concrete, the recommended value is 0.668. |

| JGJ/T 465-2019 [78] | Vfcs = Vfc + Vsv Vfc = Vc (1 + βv λf) | Vc is the design value of shear bearing capacity related to concrete. Vsv is the design value of shear bearing capacity mainly related to stirrups. Vfc is the design value of shear bearing capacity related to SFRC considering the influence of steel fiber. βv is the influence coefficient of steel fiber on the shear bearing capacity related to concrete on the inclined plane of SFRC segments. λf is the characteristic value of steel fiber dosage. |

| Model code 2010 [81] | VRk,4 = Vcd + Vfd + Vvd Vcd = (0.12 k (100 r1 fck)1/3 + 0.15 scp) (b h0) Vfd = 0.7 kf k τfd b h0 Vvd = 0.9 fyv h0 (Asv/s) | VRk,4 is the standard value of residual flexural tensile strength corresponding to the notch displacement of 3.5 mm SFRC. Vcd is the design value of the shear bearing capacity of ordinary reinforced concrete members without considering the effect of steel fiber and shear steel rebar. Vvd is the increased shear capacity of the section under the action of stirrups. ρ1 is the reinforcement ratio of steel rebars in the tensile zone. σcp is equivalent compressive stress of concrete. kf is the influence coefficient of the cross-section shape, and the rectangular cross-section takes 1. k is the influence coefficient of section height. τfd is the design shear strength of SFRC. |

| Gandomi et al. [140] | Vfcs = ((2/λ) (ρ fc + 0.41 τ F) + (1/2λ) (ρ/(288 ρ − 11)4) + 2) (b h0) | ρ is the reinforcement ratio in the tensile zone. τ is average steel fiber matrix interfacial bond stress, taken as 4.15 MPa. F is steel fiber factor. |

| Bi et al. [141] | Vu = Vc + Vf + Va + Vd | Vc is the shear bearing capacity provided by the concrete in the compression zone. Vf is the shear bearing capacity provided by the oblique crack section steel fiber. Va is the shear bearing capacity provided by aggregate bite force. Vd is the shear bearing capacity provided by the dowel action of longitudinal steel rebar. |

| Yakoub [142] | Vfcs = 2.5 β (fc’)1/2 (1 + 0.70 Vf (Lf/Df) Rg) (dv/a), for a/dv ≤ 2.5 Vfcs = β (fc’)1/2 (1+ 0.70 Vf (Lf/Df) Rg), for a/dv > 2.5 | fc’ is cylinder compressive strength; Vf is volume fraction of steel fiber. Lf/Df is aspect ratio of the steel fiber. dv is beam effective depth. a is shear span. |

| Zhang et al. [48] | V = Vcc + Vsv + Vfrc | V is the shear bearing capacity of flexural members with web steel rebar. Vcc is the shear bearing capacity of the compression zone of the member. Vsv is the shear capacity provided by stirrups. Vfrc is the shear bearing capacity provided by steel fiber. |

| Ref. | Computing Formula | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| GB 50010-2010 [79] | wmax = αcr ψ (σsk/Es) (1.9 Cs + 0.08 (deq/ρte)) | αcr is the force characteristic coefficient of the component. ψ is the strain in homogeneity coefficient of longitudinal tensile steel rebar between cracks. σsk is the equivalent stress of longitudinal tensile steel rebar of prestressed concrete members. Es is the elastic modulus of steel rebar. Cs is the distance from the outer edge of the outermost longitudinal tensile steel rebar to the bottom of the tensile zone. deq is the equivalent diameter of longitudinal steel rebar in tension zone. ρte is the reinforcement ratio of longitudinal tensile steel rebar calculated according to the effective tensile concrete cross-sectional area. |

| JGJ/T 465-2019 [78] | wfmax = wmax (1 − βcw λf) | wfmax is the maximum crack width of SFRC segments. wmax is the maximum crack width of ordinary reinforced concrete members. βcw is the influence coefficient of steel fiber on crack width. λf is the characteristic value of steel fiber dosage. |

| Model Code 2010 [81] | wf = 2 ls,max (εsm − εcm − εcs) | wf is the crack width of SFRC under serviceability limit state. ls,max is the area where the relative slip between steel rebar and concrete is the largest. εsm is the average strain of steel rebar in the maximum slip region. εcm is the average strain of concrete in the maximum slip region. εcs is the strain caused by the shrinkage of concrete. |

| DafStb Technical Rule on Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete [87] | wk = Sr,max (εfsm − εcm) | wk is the characteristic crack width of the tensile zone of steel fiber structure. Sr,max is the maximum crack spacing in the tensile zone of steel fiber structure. εfsm is the average strain of steel rebar in the range of concrete crack spacing under the condition of related load combination. εcm is the average strain in the range of concrete crack spacing. |

| Gao et al. [89] | wnfmax = ν (a + b lgN) wmax (1 − βcw λf) | wnfmax is the maximum crack width of SFRC beam under fatigue load. v is the comprehensive correction coefficient of crack width of SFRC segments under fatigue load, v = 1.4, a = −1.2518, b = 0.5458. wmax is the maximum crack width is calculated according to GB 50010-2010 without considering the influence of steel fiber. λf is the characteristic parameter of steel fiber. βcw is the crack width influence coefficient of R-SFRC specimen. |

| Wang et al. [90] | wfmax = wmax (1 − βcw λf) | wfmax is the maximum crack width of SFRC flexural members. wmax is the maximum crack width of SFRC member. βcw is the influence coefficient of SFRC crack width. λf is the characteristic value of steel fiber dosage. |

| Ning et al. [91] | wmax = 1.66 wm | wmax is the maximum crack width of steel fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete beams. wm is the average crack width of steel fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete beams. |

References

- Han, B.; Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Lu, F.; Hu, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; Feng, F.; et al. Statistical analysis of urban rail transit operations worldwide in 2024: A review. Urban Rapid Rail Transit. 2025, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liang, S.; Feng, A. Statistics and development analysis of urban rail transit in China in 2024. Tunn. Constr. 2025, 45, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Feng, K.; Fang, Y. Review and prospects on constructing technologies of metro tunnels using shield tunnelling method. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2015, 50, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Feng, K.; Sun, Q.; Wang, S. Consideration on issues about structural durability of shield tunnels. Tunn. Constr. 2017, 37, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.-Y.; Yoon, Y.-S. Structural performance of ultra-high-performance concrete beams with different steel fibers. Eng. Struct. 2015, 102, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroughsabet, V.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Mechanical and durability properties of high-strength concrete containing steel and polypropylene fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. Development trends in world tunneling technology: Safe, economical, green and artistic. Tunn. Constr. 2021, 41, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulekbache, B.; Hamrat, M.; Chemrouk, M.; Amziane, S. Influence of yield stress and compressive strength on direct shear behaviour of steel fibre-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Jiang, L.; Bai, M.; Miao, Y. Study of the performance of steel fiber reinforced concrete to water and salt freezing condition. Mater. Des. 2013, 44, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holschemacher, K.; Mueller, T.; Ribakov, Y. Effect of steel fibres on mechanical properties of high-strength concrete. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 2604–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberti, G.; Minelli, F.; Plizzari, G. Reinforcement optimization of fiber reinforced concrete linings for conventional tunnels. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, C. Three-dimensional mesoscale numerical study on the mechanical behaviors of SFRC tunnel lining segments. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 113, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, N.; Ferracuti, B.; Savoia, M. Concrete crack reduction in tunnel linings by steel fibre-reinforced concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Li, Y.; Becque, J.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, S. Axial compressive behavior of circular stainless steel tube confined UHPC stub columns under monotonic and cyclic loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 208, 112830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, J.-P.; Desmettre, C.; Androuët, C. Flexural and shear behaviors of steel and synthetic fiber reinforced concretes under quasi-static and pseudo-dynamic loadings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, A.; Fuente, A.D.L. Crack width design approach for fibre reinforced concrete tunnel segments for TBM thrust loads. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 98, 103342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanaki, M.J.; Hoseini, A.; Vahdani, S.; Santos, C.D.; Fuente, A.D.L. Seismic fragility curves for vulnerability assessment of steel fiber reinforced concrete segmental tunnel linings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 78, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, T.; Edvardsen, C.; Wittneben, G.; Neumann, D. Lining design for the district heating tunnel in Copenhagen with steel fibre reinforced concrete segments. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2008, 23, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Feng, K.; Li, M.; Xing, W.; Deng, X.; Chao, C. Performance optimisation of alkali-activated slag ultra-low carbon concrete (AAS-ULCC) for shield tunnel segments by steel fibres. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, C.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y. Mechanical, fracture and environmental performance evaluation of steel fiber reinforced industrial solid wastes based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 143038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Gao, B.; Zhou, J.; Cao, G.; Zhang, Q. Experimental investigation of the mechanical behavior of the steel fiber reinforced concrete tunnel segment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Liu, X. A full-scale experimental study on bearing capacity of fiber reinforced concrete segments. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2019, 15, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.; Soliman, A.M.; Nehdi, M.L. Experimental study on settlement and punching behavior of full-scale RC and SFRC precast tunnel lining segments. Eng. Struct. 2014, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Research on shear performance of non-constant resistance and slip anchor joint of shield tunnels. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 51, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; He, C.; Xiao, M. Bending tests of segment joint with complex interface for shield tunnel under high axial pressure. China Civ. Eng. J. 2016, 49, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ding, W. Experimental investigation on ultimate bearing capacity of steel fiber reinforced concrete segment joints in shield tunnels. China J. Highw. Transport. 2017, 30, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caratelli, A.; Meda, A.; Rinaldi, Z.; Giuliani-Leonardi, S.; Renault, F. On the behavior of radial joints in segmental tunnel linings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 71, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, H.; Shen, Y. Experimental study on behavior of ductile-iron joint panels for high-stiffness segmental joints of deep-buried drainage shield tunnels. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2019, 47, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Shen, Y.; Guan, L.; Wen, Z.; Li, Y. Experimental study on mechanical characteristics of high stiffness segmental joint with steel fibers for deep-buried drainage shield tunnels. J. Build. Struct. 2020, 41, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Xu, X.; Liu, X. Mechanical properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete segment lining. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 3463–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Fu, Y.; Jian, Y.; Lu, X. Critical state analysis of instability of shield tunnel segment lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 96, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Yao, C. The progressive failure features of shield tunnel lining with large section. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 164, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Feng, F.; Huang, S.; Xu, T.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. Full-scale loading test for shield tunnel segments: Load-bearing performance and failure patterns of lining structures. Undergr. Space 2025, 20, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Jin, H.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Cai, L. Experimental study on crack features of steel fiber reinforced concrete tunnel segments subjected to eccentric compression. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, H.; Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Jalali, S. Experimental investigation on the mechanical behaviour of the fiber reinforced high-performance concrete tunnel segment. Compos. Struct. 2011, 93, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.C.T.; Pereira, G.B.S.; Silva, F.A.; Filho, J.J.H.S.; Pereira, E.V. Influence of steel fibers on the flexural behavior of RC beams with low reinforcing ratios: Analytical and experimental investigation. Compos. Struct. 2019, 222, 110926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Rucka, M. Microcrack monitoring and fracture evolution of polyolefin and steel fibre concrete beams using integrated acoustic emission and digital image correlation techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 395, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jiang, Z.; Ou, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, C. Analysis on flexural toughness of steel fiber reinforced concrete based on acoustic emission and digital image correlation techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 143039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Gao, D.; Ding, C.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Whole process analysis on splitting tensile behavior and damage mechanism of 3D/4D/5D steel fiber reinforced concrete using DIC and AE techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelis, D.G.; Soulioti, D.V.; Sapouridis, N.; Barkoula, N.M.; Paipetis, A.S.; Matikas, T.E. Acoustic emission characterization of the fracture process in fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 4126–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelis, D.G.; Soulioti, D.V.; Barkoula, N.M.; Paipetis, A.S.; Matikas, T.E. Influence of fiber chemical coating on the acoustic emission behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelis, D.G.; Soulioti, D.V.; Gatselou, E.A.; Barkoula, N.-M.; Matikas, T.E. Monitoring of the mechanical behavior of concrete with chemically treated steel fibers by acoustic emission. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 48, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, H.; Yu, S.; Bi, X.; Zhou, S. Analysis of bending deflection of tunnel segment under load- and corrosion-induced cracks by improved XFEM. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehdi, M.L.; Abbas, S.; Soliman, A.M. Exploratory study of ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete tunnel lining segments with varying steel fiber lengths and dosages. Eng. Struct. 2015, 101, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Chi, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, C. Effects of fiber type, volume fraction and aspect ratio on the flexural and acoustic emission behaviors of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhen, X.; Wen, C.; Chen, G. Effects of steel fiber on the flexural behavior and ductility of concrete beams reinforced with BFRP rebars under repeated loading. Compos. Struct. 2021, 270, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshwaran, A.; Lai, B.; Liew, J.Y.R. Design of Steel Fiber-Reinforced High-Strength Concrete-Encased Steel Short Columns and Beams. ACI Struct. J. 2021, 118, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, Y.; Ding, Y. Influence of toughness on shear behavior of steel fiber reinforced self-consolidating concrete beams. J. Build. Mater. 2015, 18, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Xia, Y.; Fang, H. Experimental study on fracture mechanism and tension damage constitutiverelationship of steel fiber reinforced concrete. China Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 54, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.G.; Wang, Y.N.; Beskos, D.E. Uniaxial tension damage mechanics of steel fiber reinforced concrete using acoustic emission and machine learning crack mode classification. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 123, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Yan, Z.; Song, B.; Zhu, H.; Liu, F. Numerical modeling tests on local stress of SFRC tunnel segment joints. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2006, 28, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Liao, S.; Liu, F. A study on performance of steel fiber reinforced segment. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2006, 25, 2888–2893. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Niu, R.; Qi, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; He, L.; Lyu, J. Impact of jack thrust on force and deformation of segment linings for shallow-buried shield tunnel with super large diameter. Tunn. Constr. 2022, 42, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, W. Mechanical and waterproof performances of joints of shield tunnels with large cross-section under earthquakes. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 43, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Feng, K.; Guo, W.; Lu, X.; He, C. Study on the influence of bolt failure on bending strength of longitudinal joint of shield tunnel segments. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2023, 60, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, X. Breaking mechanism of segmented lining in shield tunnel based on fracture mechanics. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Chen, J.; Liang, S.; Yang, Y.; Su, Y. Improvement of local mechanical properties of concrete segment by steel-fiber reinforcement. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 35, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, P.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Tang, L.; Li, R. Eccentric compression model test of steel fiber reinforced concrete lining segments. J. Build. Struct. 2018, 39, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, D. Mechanical response test of SFRC segment under jacking construction. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 41, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, H.; Sun, K. Multiscale simulation of debonding in fiber-reinforced composites by a combination of MsFEM and XFEM. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 306, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, C.; Wei, B.; Li, Y. 3D mesoscale discrete element modeling of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 138006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Deformation and crack propagation characteristics of carbon fiber reinforced concrete shield segments based on particle discrete element. Urban Mass Transit. 2024, 27, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Research on the deformation and failure mechanism of prefabricated segments under the action of hierarchical loading based on microstructure. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 45, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lyu, W.; Wang, Y. Simulation study of shield tunneling based on the block-based discrete element method and deformation of the surrounding rock and liner. Urban Rapid Rail Transit. 2024, 37, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zeng, S.; Han, W.; Su, D. Review and prospect of machine learning method in shieldtunnel construction. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2024, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.; Xu, G.; He, Z. Nondestructive detection of fiber content in steel fiber reinforced concrete through percussion method coordinated with a hybrid deep learning network. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Tan, J. Intelligent mix design of steel fiber reinforced concrete using a particle swarm algorithm based on a multi-objective optimization model. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarani, N.; Sharifi, H.; Sharifi, Y. Prediction of shear capacity of slender SFRC beams without stirrup through combination of particle swarm optimization and neural network. Structures 2024, 68, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, F.; Tan, D.; Yang, A. A deep learning informed-mesoscale cohesive numerical model for investigating the mechanical behavior of shield tunnels with crack damage. Structures 2024, 66, 106902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttignol, T.E.T.; Santos, A.C.D.; Bitencourt, L.A.G. 3D DEWS digital parametric modeling and manufacturing for obtaining the post-cracking parameters of SFRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, V.; Moradi, M.J.; Daneshvar, K.; Hajiloo, H. Application of artificial intelligence in predicting the residual mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) after high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabene, W.B.; Nehdi, M.L. Genetic programming based symbolic regression for shear capacity prediction of SFRC beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Demartino, C.; Chen, W.; Yu, Y. Mechanical properties of SFRC: Database construction and model prediction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olalusi, O.B.; Awoyera, P.O. Shear capacity prediction of slender reinforced concrete structures with steel fibers using machine learning. Eng. Struct. 2021, 227, 111470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Y.M.; Khan, M.I. Efficacious application of data-driven machine learning models for predicting and optimizing the flexural tensile strength of fiber-reinforced concrete. Structures 2024, 64, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasabha, G.; Al-Shboul, K.F.; Shehadeh, A.; Alshboul, O. Machine learning-based models for predicting the shear strength of synthetic fiber reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. Structures 2023, 52, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, K.; Liang, X.; Lian, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Bearing capacity evaluation method for segment lining structure of shield tunnel. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 51, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T 465-2019; Standard for Design of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Structures. China Architecture and Building Press, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- ACI 318-14; Building Code Requirement for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-14) Andcommentary (ACI 318R-14). ACl Committee 318: Detroit, MI, USA, 2014.

- fib. Model Code 2010; International Federation for Structural Concrete: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, G.; Wu, B.; Xu, S.; Huang, J. Modelling and experimental validation of flexural tensile properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, Z.; Wen, S.; Deng, Y. Research on the application of steel fiber reinforced concrete segment in shield tunnelling based on the post-cracking linear softening model. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2021, 58, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, B.; Zhou, J.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, H. Study on shearbearing capacity design of SFRC shield segment. Concrete 2014, 3, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Feng, K.; Yang, R.; Xie, J.; Gou, C. Comparative study on applicability of normal section design method for steel fiber-reinforced concrete segment. Tunn. Constr. 2021, 41, 1530–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.H.-K.; Kim, W.; Kwak, Y.-K.; Hong, S.-G. Shear testing of steel fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete beams without web reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 2011, 108, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAfStb. Technical Rule on Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete-EC2 Version; German Committee for Reinforced Concrete (DAfStb): Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J.; Wang, Z.; Huo, L.; Zhao, Y. Calculation method of bending moments and crack openings of steel fiber reinforced concrete beams with longitudinal reinforcement. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2021, 40, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J. Calculating method for crack width of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete beams under fatigue loads. China Civ. Eng. J. 2013, 46, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P. Experimental research on the influence factor of crack width of steel fiber reinforced concrete. J. Railw. Eng. Soc. 2019, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, X.; Ding, Y. Experimental research on crack width of steel fibers reinforced self-consolidating concrete beams. Eng. Mech. 2017, 34, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, L.; Chi, Y.; Huang, B.; Li, C. Experimental investigation on the stress-strain behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete subjected to uniaxial cyclic compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ding, W.; Mosalam, K.M.; Günay, S.; Soga, K. Comparison of the structural behavior of reinforced concrete and steel fiber reinforced concrete tunnel segmental joints. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 68, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bai, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Mang, H.A. Experimental investigation of the ultimate bearing capacity of continuously jointed segmental tunnel linings. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2015, 12, 1364–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Luo, J.; Fan, K.; Chen, J.; Zhu, M.; Gao, Y. Meso-compressive fracture simulation and performance analysis of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 42, 3884–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shao, X.; Zhu, P. Direct tensile behaviors of steel-bar reinforced ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete: Effects of steel fibers and steel rebars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, H.; Bao, H. Experimental research and theoretical analysis of mechanical behaviorsof fiber reinforced concrete segments. Mod. Tunneling Technol. 2018, 55, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Research on the bending strength of shield segment by steel fiber reinforced concrete. Build. Struct. 2022, 52, 1417–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Gao, D.; Ding, Z. An exper imental study on the flexur al per for mances of SFRC beamsr eplacing composition RC beams. China Civ. Eng. J. 2006, 39, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Z. Research on crack development of unreinforced steel fiber concrete compression-bending beam. Build. Struct. 2020, 50, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Sun, X.; Li, C.; Gou, Y. Flexural toughness of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2003, 6, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Influence of concrete strength combined with fiber content in the residual flexural strengths of fiber reinforced concrete. Compos. Struct. 2017, 168, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Huang, C. Study on stress strain curve of high strength steel fiber reinforced concrete under uniaxial tension. China Civ. Eng. J. 2006, 39, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.; Gesoğlu, M.; Akoi, A.O.M.; Mermerdaş, K. Combined effect of steel fiber and metakaolin incorporation on mechanical properties of concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, E.; Saatçioğlu, Ö.; Turanli, L. Parameter optimization on compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2837–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; He, W.; Wu, L. Effects of steel fiber content and shape on mechanical properties of ultra high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 103, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Lebdeh, T.; Hamoush, S.; Heard, W.; Zornig, B. Effect of matrix strength on pullout behavior of steel fiber reinforced very-high strength concrete composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Design of steel fiber reinforced concrete based on stress crack opening relationship. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Research on the experiment of the bonding strength between deformed steel fiber and concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2007, 10, 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, J.; Li, T.; Chen, D.; Shang, L.; Li, W.; Zhu, Q. Mechanical properties of concrete reinforced with corrugated steel fiber under uniaxial compression and tension. Structures 2021, 34, 1890–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ren, Y.; Lian, D.; Jin, L.; Li, L.; He, D. Experiment on shear performance of different types of steel fiber UHPC beams without stirrups. J. Guilin Univ. Technol. 2024, 44, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Park, P.; Rew, Y.; Huang, K.; Sim, C. Constitutive behaviors of steel fiber reinforced concrete under uniaxial compression and tension. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, D.L.; Sharma, A.; Chada, R.R.; Kiran, R.; Sirotiak, T. Modified pullout test for indirect characterization of natural fiber and cementitious matrix interface properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 208, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; Khayat, K.H. Influence of silica fume content on microstructure development and bond to steel fiber in ultra-high strength cement-based materials (UHSC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 71, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Huang, X.; Huang, Q.; Shiau, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, J.; Fahimizadeh, M.; Sabri, M.M. Effects of particle size on properties of engineering muck-based geopolymers: Optimization through sieving treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareiro, W.G.; Silva, F.D.A.; Sotelino, E.D. Thermo-mechanical behavior of stainless steel fiber reinforced refractory concrete: Experimental and numerical analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, J.; Geng, G.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X. Effect of fiber types on creep behavior of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.; Zhao, X.; Lu, R. Experimental investigation on shear performance of fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete dry joints. China J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhu, H.; Yan, D.; Yuan, S.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y. Experimental study on the effect of steel fiber embedment depth and type on the interfacial bonding properties of steel fiber-UHPC matrix. Mater. Rep. 2023, 37, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, D.-Y.; Park, J.-J.; Kim, S.-W. Fiber pullout behavior of HPFRCC: Effects of matrix strength and fiber type. Compos. Struct. 2017, 174, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Liao, L. Investigation on the relationship between the steel fibre distribution and the post-cracking behaviour of SFRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 200, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X. Experimental and numerical study of hooked-end steel fiber-reinforced concrete based on the meso- and macro-models. Compos. Struct. 2023, 309, 116750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Q.; Bai, W. Parametric characteristic analysis of steel fiber concrete under complex dynamic loads. China Civ. Eng. J. 2010, 43, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Geng, J.; Yang, R.; Xiao, M.; Gong, Y.; Xie, J.; Gou, C. Study on bearing capacity degradation model for corroded steel fiber reinforeed concrete segments on tension side. China Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 55, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on compressive properties of SFRC under high strain rate with different fiber content and aspect ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Chi, Y.; Yi, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, X. Influence of hybrid steel fibers on interfacial bond performance between steel fiber and ultrahigh-performance concrete. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 48, 1669–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, G.; Yan, Q.; Ma, M. Study on mechanical properties and flexural toughness of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Railw. Stand. Des. 2017, 61, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, G.; Wang, M. Experimental study on flexural properties and fiber distribution of steel fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2020, 23, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Ali, M.; Xie, T.; Visintin, P.; Sheikh, A.H. The influence of steel fibre properties on the shrinkage of ultra-high performance fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.G. Experimental and numerical analysis on effect of fibre aspect ratio on mechanical properties of SRFC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, Ş.; İnan, G.; Tabak, V. Effect of aspect ratio and volume fraction of steel fiber on the mechanical properties of SFRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, L. Shear behavior of hybrid fiber reinforced high performance concrete deep beams. China Civ. Eng. J. 2013, 46, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Meson, V.; Michel, A.; Solgaard, A.; Fischer, G.; Edvardsen, C.; Skovhus, T.L. Corrosion resistance of steel fibre reinforced concrete—A literature review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 103, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, X.; Cao, Z.; Yang, L.; Xu, W.; Gao, D. Mechanical properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) mixed with NaCl solutions of varying concentrations. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Lv, M.; Zhu, H.; Zhan, Z.; Su, Q. Flexural behaviour of concrete beams repaired by hybrid fibre reinforced cementitious composites (HFRCCs) and subjected to simulated seawater dry-wet cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 480, 141543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Shi, J. Application of steel fiber-reinforced cement-based grouting material in strengthening reinforced concrete beams exhibiting insufficient shear strength in historical buildings. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Khayat, K.H. Effect of shrinkage-mitigating materials, fiber type, and repair thickness on flexural behavior of beams repaired with fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 156, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Geng, H.; Deng, C.; Li, B.; Zhao, S. Experimental investigation on columns of steel fiber reinforced concrete with recycled aggregates under large eccentric compression load. Materials 2019, 12, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y. Design method of normal section bearing capacity of steel fiber reinforced concrete without reinforcement. Build. Struct. 2023, 53, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.H.; Alavi, A.H.; Yun, G.J. Nonlinear modeling of shear strength of SFRC beams using linear genetic programming. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2011, 38, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huo, L.; Wang, G. Analysis on sear bearing capacity of SFRC beams without web reinforcements based on ductile shear failure mechanism. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2021, 54, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakoub, H.E. Shear stress prediction: Steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams without stirrups. ACI Struct. J. 2011, 108, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Researcher | Method | Research Direction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFRC Material | SFRC Mechanical Performance | Tunnel Segment | ||

| Zhang et al. [66] | Hybrid model | √ | ||

| Buttignol et al. [70] | Pull-out analytical model | √ | ||

| Sun et al. [67] | Back propagation neural network | √ | √ | |

| Farhangi et al. [71] | AI-based model | √ | ||

| Zafarani et al. [68] | Hybrid model | √ | ||

| Chaabene et al. [72] | Genetic-programming-based symbolic regression model | √ | ||

| Wang et al. [73] | Bayesian model updating | √ | ||

| Olalusi et al. [74] | Hybrid model | √ | ||

| Abbas et al. [75] | Hybrid model | √ | ||

| Almasabha et al. [76] | Extreme gradient boosting | √ | ||

| Light gradient boosting machine | ||||

| Gene expression programming | ||||

| Zhao et al. [69] | Mask-region-based hybrid attention convolutional neural network | √ | ||

| Researcher | Fiber Shape | Variables Investigated | Fiber Geometry | Mechanical Performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l (mm) | d (mm) | l/d | CS | ATS | FS | EM | BS | |||

| Yang et al. [103] | Hooked-end/ Straight | SFAR, SFT, COS, W/C | 30/ 32/ 32/ 30.31 | 0.54/ 0.94/ 0.58/ 0.67 | 55.56/ 34.04/ 55.17/ 45.24 | √ | ||||

| Güneyisi et al. [104] | Hooked-end | APS, AT, COS, SFAR, W/B | 60/ 30 | 0.75/ 0.75 | 80/ 40 | √ | √ | |||

| Ayan et al. [105] | Straight | APS, ATA, SFVF | 6 | 0.16 | 37.5 | √ | ||||

| Zhao et al. [101] | Hooked-end/ Corrugated/ Big head straight/ Indentation belt end | COS, W/C, SFV, SFAR, SFT | 32/ 31/ 31/ 31 | 0.77/ 0.82/ 0.78/ 0.82 | 41.5/ 38.5/ 39.7/ 37.7 | √ | ||||

| Wu et al. [106] | Straight/ Corrugated/ Hooked-end | APS, AT, SFAR, W/B, SFT | 13 | 0.2 | 65 | √ | √ | |||

| Abu-Lebdeh et al. [107] | Hooked-end/ Flattened-end/ Helix/ Hooked-end | COS, APS, AT, SFAR, W/B, SFT | 30/ 50/ 25/ 30 | 0.56/ 1.17/ 0.49/ 0.38 | 53.57/ 42.74/ 51.02/ 78.95 | √ | ||||

| Zhang et al. [108] | Hooked-end | COS, AZ, AT, SFAR, W/B, SFVF | 30/ 35 | 0.6/ 0.45 | 50/ 77.78 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Tian et al. [109] | Hooked-end/ Straight | COS, SAR, SFVF | 35/ 33.71 | 0.5/ 1.08 | 70/ 31.21 | √ | ||||

| Ran et al. [110] | Corrugated | APS, COS, SFVF, SFAR, SFT | 36.44 | 1.04 | 35.04 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Cao et al. [111] | Smooth straight/ Hooked-end/ Corrugated | SFAR, SFT | 13/ 22/ 35 | 0.22/ 0.3/ 0.8 | 59.09/ 73.33/ 43.75 | √ | ||||

| Li et al. [45] | Straight/ Hooked-end/ Corrugated | SFVF, SFAR, SFT | 12/ 30/ 45/ 60 | 0.2/ 0.5/ 0.75/ 0.75 | 40/ 60/ 80/ 80 | √ | ||||

| Shi et al. [112] | Straight/ Hooked-end | SFAR, SFT | 13/ 33 | 0.2/ 0.55 | 65/ 60 | √ | √ | √ | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, G.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234354

Meng G, Li H, Liu G, Han Y, Zhang Y, Huang C. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234354

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Guowang, Hongting Li, Guangyang Liu, Yu Han, Yuanyuan Zhang, and Chuan Huang. 2025. "Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234354

APA StyleMeng, G., Li, H., Liu, G., Han, Y., Zhang, Y., & Huang, C. (2025). Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions. Buildings, 15(23), 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234354