Abstract

Urban residents and especially children have limited contact with nature and are not sufficiently informed about the main problems of its protection and preservation. One of the aspects of increasing the environmental awareness of urban children is to familiarize them with the specifics of agricultural production. A significant problem in organizing agricultural-themed children’s gaming complexes is the creation of an appropriate infrastructure for exhibiting natural and agricultural processes and servicing visitors. One of the possible solutions to this problem is the use of used sea containers for facilities of educational and gaming infrastructure. An important characteristic of such containers is the ability to use them both individually and in various quantitative and combinatorial ways, forming the buildings necessary for exhibiting and servicing. The use of combined container groups makes it possible to organize appropriate temporary or permanent educational and gaming complexes in free territories within cities or suburbs, bringing them as close to consumers as possible. The children’s educational and game complex with agricultural themes is a set of organizationally and spatially interconnected buildings and structures that ensure the display of agricultural production processes based on the active participation of visitors.

1. Introduction

In modern cities, residents (and especially children) for the most part have no direct contact with agricultural production (except for the final product). Raising children’s awareness of environmentally optimal agricultural production is an urgent task in the field of sustainable development. Educational and playful agro-tourism for children, which forms environmentally responsible behavior, is one of the promising areas of modern recreation and a healthy lifestyle. In general, this phenomenon is considered a mini trip involving recreation and entertainment combined with environmental education, which was conducted at a site where a demonstration of agricultural work is organized.

The problem of children’s environmental education is very relevant. Various aspects of this problem are discussed in the works of N.M. Ardoin and A.W. Bowers [1], N. Mousavi, S. Ahmadi, M.S. Sani, S.F. Irandoost, M.A.M. Gharehghani and Z. [2], N. Silo, N. Mswela and G. Seetso [3], C.A. Grimberg and A. Cortazar [4], S. Stavreva Veselinovska [5] and others [6].

An interesting example is the peculiar type of “non-travel” agro-tourism in the office space. It is assumed that periodic crop and animal husbandry activities increase the productivity of office workers; therefore, in the office of the “Pasona” company there are plantations of rice, vegetables, fruits, cacti, rooms for animals and birds, which employees take care of during breaks. The harvested crops are used in local canteens. This formed a kind of “urban ranch” which hosts seminars on nutrition education, cooking classes, seminars on plant and animal husbandry, and other activities that allow participants to interact with animals and plants. The target audience of this project is not only adults, but also children [7,8,9].

The process of playing is one of the most effective forms of the education of various skills in children. Accordingly, an interesting demonstration of agricultural production processes and the feasible participation of children in these processes under the guidance of instructors and educators will help to form a responsible attitude towards nature among children.

Agricultural tourism is a multifaceted activity, various types of which are considered with varying degrees of detail in a large number of works. Thus, rural tourism as a strategy for the development of territories is considered in the work of C. Yesid Aranda, G. Juliana Combariza and B. Alvaro Parrado [10]. An example of the analysis of the environmental component is provided in the work by P. Valentine [11].

The multidimensional social component, including the family component, has been highlighted in several studies. L. Minnaert demonstrates that the travel experience and the associated level of uncertainty play a key role in determining the most appropriate travel product for certain groups of beneficiaries of social tourism. Accordingly, a decrease in the level of uncertainty may be associated with a decrease in anxiety levels and, as a result, with the choice of more “complex” tourism options in terms of duration and level of support [12]. H.A. Schänzel and I. Yeoman consider the features and prospects of family tourism [13]. J.G. Ferrer, M.F. Sanz, E.D. Ferrandis, S. McCabe and J.S. García discuss the impact of tourism activity of the elderly on their health study. The analysis was carried out using a model of structural equations. The results of this study allow us to draw preliminary conclusions about the causal relationships between tourism and indicators of physical and mental health [14]. H. Kim, E. Woo and M. Uysal analyze the features of the tourist experience of pensioners related to trip satisfaction, quality of service, the uniqueness of tourist programs, etc. The combination of these factors is considered as the basis for the formation of the need for a repeat trip [15]. J. Jablonska, M. Jaremko and G.M. Timčák consider the specifics of “social tourism” as a specific activity; the definition of “social tourism” is given: it provides comfortable travel opportunities for low-income categories of citizens and socially protected groups of the population; the prospects for the development of “social tourism” are shown using the example of their country [16].

A separate aspect is agrarian tourism as an integral part of sustainable development. Here, the works of E. Cater, G. Lowman, S. Ross, G. Wall, M. Honey, S. Wearing, and S. Schweinsberg stand out. In the study by E. Cater and G. Lowman with co-authors, eco-tourism is considered as an aspect of sustainable development [17]. S. Ross and G. Wall indicate that ecotourism can contribute to both conservation and development and presupposes, at a minimum, positive synergetic relations between tourism, biodiversity and the local population, which are facilitated by proper management [18]. M. Honey discusses the issue of ecotourism’s compliance with the prospects of sustainable development [19]. Ecotourism as a promising model of behavior in the next century is analyzed by S. Wearing and S. Schweinsberg [20].

It is interesting that the modularity of services in tourism activities, considered in the work of V. Avlonitis and J. Hsuan [21], can correspond to the modularity of the structure of tourist complexes. This leads to the idea of using the modularity inherent in sea containers, which is indicated, for example, by E. Mohamed: “Usage of modular containers could be suitable for limited projects which need limited space dimensions according to its structural features which eliminate the height and remove side walls” [22]. Modularity opens up the possibility of forming agro-information complexes in free territories inside cities. Such complexes can be permanent or temporary (for example, movable from one site to another within one city or in different cities).

In several of the following studies, the theoretical and practical aspects of the reuse of shipping containers are considered from different points of view. Thus, general issues of design and construction are analyzed in a large number of studies [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. The feasibility of such an approach is emphasized by L.F.A. Bernardo, L.A.P. Oliveira, M.C.S. Nepomuceno, and J.M.A. Andrade: “The feasibility of this construction system, based on the use of refurbished shipping containers as construction modules for buildings, should be recognized” [26]. K.M. Ismail, A.M.A. Al-Obaidi, and M.I. Ahmad draw attention to the significant potential: “The container building has huge potential to be one of the major architectural types that can offer durable, practical, cheaper and comfortable living space in a shorter construction period” [31]. The possibilities of strength parameters with increasing stacking height are discussed by S. Martin, J. Martin and P. Lai: “Increasing stack heights on container ships and growing volumes of high-density cargo have increased the loads and stresses placed on containers, requiring an assessment of current container strength specifications” [39].

The problems of energy efficiency with different roofing and wall covering materials are considered by H. Taleb, M. Elsebaei and M. El-Attar, who indicate that “the most effective strategy was the use of green roofs and green walls as these reduce energy consumptions by 13.5%” [40]. Interesting results pointed out by D. Satola, A.B. Kristiansen, A. Houlhan-Wiberg, A. Gustavsen, T. Ma and R.Z. Wang are the following: “The life-cycle assessment results indicate that the net-zero energy design strategy has the lowest life-cycle impacts in all categories, with 26% reduction in water consumption and up to 86% reduction in terms of global warming potential with respect to the convectional, baseline design” [34]. The specificity of thermal insulation is emphasized by J. Shen, B. Copertaro, X. Zhang, J. Koke, P. Kaufmann and S. Krause: “As for repurposing container buildings, it means higher demands in improving both thermal resistance and hygro-thermal capacity of the container. For instance, the weakness in air tightness can be improved by applying a closed insulation enhancement throughout the whole enclosure. Such processing meanwhile can assist in lowering thermal bridge” [44].

The aspect of sustainable architecture in the field of container application is indicated in several works [47,48,49,50,51,52]. For example, H-Y. Chen, H-H. Lin and H-L. Hsu point out that “The transformation of container architecture which combined with new materials and new technologies is easy to create a poetic atmosphere for spatial users. It is easy to touch the public’s sensory and experience. The kind of container architecture contains not only the existing purpose of containers, but also the ideas about the transformation of the catalyst of economic development. It can be seen not only as an assemblage of spatial material, but also as a course of sustainable development” [47]. The significant duration of operation is indicated by H. Islam, G. Zhang, S. Setunge and M.A. Bhuiyan: “For all the impact categories, the overall contributions of the whole life cycle impacts have increased significantly if the design life of a building is increased to 100 years” [51].

The problem of reusing sea containers, including in the production of agricultural products, has attracted considerable attention from researchers [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. For example, the following is indicated: “Urban farming–growing crops inside shipping containers. Freight Farms have found a way to grow crops inside shipping containers. Their hydroponic farming system called The Leafy Green Machine uses hi-tech growing technology to transform discarded shipping containers into mobile farm units. Each farm can produce as much food as a two-acre plot of land on a much smaller plot than is required by traditional crops. As the outdoor climate has no impact on the conditions inside the container, food can be produced throughout the year and in any location. The project truly taps into the growing trend for urban farming and reduces the ecological footprint of food production” [63]. Or, for example, “Urban Farming. As urban spaces become more crowded, finding room for traditional farming becomes a challenge. Shipping containers are perfect for converting into self-contained vertical farms or hydroponic systems. This would not only make efficient use of space but also provide a local source of fresh produce, reducing the carbon footprint associated with long-distance transportation of food. The steel structure and sustainability of a shipping container make it ideal for maintaining controlled conditions necessary for such farming methods” [64]; “the choice of this construction system is directly based on what’s known as the blue economy, that is, the economy that’s linked to the sustainable development of the sea” [65].

The benefits of reusing packaging are considered separately [73,74].

Despite the significant number of works on agricultural tourism, most of them are devoted to organizational and economic aspects. At the same time, the actual issues of volumetric and planning solutions for the exposition and related service buildings are considered quite rarely and mainly in terms of usage of existing buildings and structures on site, which are adapted in one way or another for tourist needs.

However, the existing range of buildings is clearly insufficient for the active development of tourist potential. In addition, assume the very display of agricultural production to be within the framework of the standard work of an agricultural enterprise, which is ineffective in terms of creating an attractive display scenario, and a number of techno-logical processes are generally inappropriate for children. In addition, most agricultural enterprises are located at a considerable distance from cities. That is, their visit can take almost a whole day. This limits the possibility of visiting them on weekends and holidays. Therefore, it is advisable to consider the possibility of organizing a game agro-exposition both in the structure of urban public spaces (separate thematic pavilions for daily visits) and in close proximity to cities (pavilions of various themes with a complex of service units for targeted “weekend trips”). Naturally, pavilions of various subjects are located at a distance from residential, public buildings and from each other in accordance with state sanitary standards.

Accordingly, there is a need to form a relatively independent complex of buildings and structures focused specifically on exhibiting agricultural activities in combination with related visitor services. That is, the problem of accelerated, almost simultaneous construction of a large number of objects that has arisen at this stage of development of tourist services puts forward a number of unique tasks that have not yet received appropriate research development.

Based on previous special studies in the field of agricultural tourism organization (I. Ostapenko [75]) and the formation of children’s play spaces (E. Schneider [76]), the need has been identified and the possibility of creating children’s educational and gaming complexes of agricultural themes based on modular collapsible complexes has been identified. The various combinations of containers proposed by the authors (with a layout based on specific technological requirements) make it possible to solve these problems.

The rapid construction of a large number of typologically different objects, technologically linked into a children’s agricultural tourism complex, suggests the possibility of using end-to-end modularity. However, a large number of studies on the use of containers do not cover the sphere of tourism activities.

Several studies have addressed the design of play spaces for children [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. The work by J. Schipperijn, C.D. Madsen, M. Toftager, D.N. Johansen, I. Lousen, T.T. Amholt and C.S. Pawlowski provides a review of all studies devoted to the use of playgrounds and their health benefits for children [79]. For example, M. Jansson emphasizes that children’s participation in playground management activities is considered a way to make playgrounds more responsive to children’s needs and views [80]. S. Xu presents ideas and schemes for designing child-friendly play spaces that combine beauty and entertainment [84].

The analysis so far revealed no studies on the use of shipping containers for children’s play structures. This indicates the lack of research on this topic and demonstrates the novelty of the presented study.

Several preliminary studies conducted by the authors of this article highlighted the existing possibilities in the field of modular approach in general [87] and using containers in particular [88,89].

The basis of the presented research is a complex of problems that are in varying degrees of study:

- -

- Children’s play spaces as places of active recreation and education of interpersonal communication skills;

- -

- Environmental education of children;

- -

- Rural tourism as a basis for sustainable development of territories;

- -

- Tourism as the basis of physical and psychological health;

- -

- Social tourism for low-income segments of the population;

- -

- The formation of urban mini farms for the production of certain types of agricultural products;

- -

- Advantages of modularity in construction when reusing shipping containers;

- -

- Advantages of collapsible construction in the reuse of shipping containers.

Based on the conducted research on the degree of study of the problem, the following conclusions can be drawn. The problem has three main aspects: parenting, agro-tourism, and container reuse.

The works on child rearing considered in the aspect of the issue under study focus on the specifics of the formation of play spaces, the benefits of their mass distribution for children’s health and their full development. The expediency of feasible participation of children in the formation of play spaces is highlighted separately. Special attention is paid to the expediency of creating inclusive play spaces that take into account the specifics of the behavior of children with special needs. The planning features of such spaces are not considered.

The analyzed research on agro-tourism is mainly focused on organizational and economic issues. Rural tourism is considered as the basis for the sustainable development of territories. Some works highlight the specifics of tourism in general and agro-tourism in particular as the basis of physical and psychological health. An important part of the problem is considered to be informing the population about environmentally adequate methods of production of agricultural products and the expediency of environmental protection measures. The researchers emphasize the social importance of agro-tourism in the field of caring for low-income segments of the population. Spatial and planning solutions for agro-tourism facilities are not considered.

Studies on the use of urban mini farms for the production of certain types of agricultural products indicate their low prevalence. The analysis showed that these mini farms are not focused on exposing production processes. There is no possibility of active participation of citizens in the production processes.

Studies in the field of combining containers of various types and the advantages of reuse of containers for buildings of various purposes fully reveal this aspect. However, the scope of using containers for children’s play complexes has not been studied and it is necessary to increase the knowledge.

The combined consideration of the issues of the formation of full-fledged children’s educational and play spaces based on the exhibition of agricultural production determines the originality of the presented research.

Accordingly, the authors’ proposed use of a module based on a sea container as a basis for the formation of various objects for the implementation of recreational and educational services has the quality of novelty.

The purpose of the presented study is to demonstrate the fundamental possibility of using modular sea containers to create collapsible children’s educational and play complexes with agricultural themes. The purpose of this article is to specifically outline the possibilities for creating a multi-thematic agricultural exhibition with a full range of auxiliary facilities. Detailed descriptions of individual facilities are necessary to substantiate the author’s concept. These descriptions and drawings demonstrate the spatial organization of individual facilities.

At the next stage (this may be the topic of a separate study), the number of sea containers of various types is determined depending on the specific theme of the complex (general agricultural or narrowly focused), location, frequency of assembly/disassembly and movement assumed by the business plan. At this stage, the depreciation period of individual containers, the need for their phased replacement, etc., will be determined.

The analysis of the theory and practice of educating modern children on environmentally responsible behavior and raising children’s awareness of environmental protection techniques revealed the following aspects:

- -

- Children do not have enough information about the specifics of environmental protection activities and the formation of a healthy lifestyle;

- -

- To compensate for this disadvantage, it is advisable to use gaming methods more widely;

- -

- In order to improve gaming methods, it is necessary to increase the information saturation of gaming spaces in the aspect of agricultural production;

- -

- In order to improve the understanding of the specifics of agricultural production, it is necessary to ensure the active involvement of children in the production processes;

- -

- To ensure the solution of these tasks, it is advisable to form children’s educational and gaming complexes for the exhibition of agricultural subjects;

- -

- To ensure maximum accessibility, such children’s complexes should be located in various areas of cities and suburbs (in the courtyards of apartment buildings, in the courtyards of kindergartens, in the courtyards of schools, in urban squares, in urban parks, in suburban recreation areas);

- -

- To maintain constant interest, children’s complexes should periodically change the theme of games;

- -

- To change the theme, children’s complexes must be prefabricated; for the convenience of rapid construction and reconstruction, children’s complexes should have modularity; for the formation of children’s complexes, it is advisable to use sea containers that are modular, durable and interchangeable;

- -

- The modern practice of reuse of shipping containers demonstrates the possibility of building buildings for various purposes;

- -

- All the processes of modern agricultural production are demonstrated in an educational and attractive way in buildings made of containers.

Based on this, the authors hypothesize that the improvement of modern methods of educating children on environmentally responsible behavior is ensured by the construction of children’s educational and play complexes with agricultural themes. The optimal architectural and constructive solution is the use of shipping containers. A conceptual solution for urban and suburban children’s educational and play complexes with agricultural themes are presented in this article. The article describes a specific case in which the logic of designing children’s play agro-complexes is documented and analyzed; the educational value of these facilities and the consequences of the widespread use of a modular approach in the field of construction design for sustainable development are indicated.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the general scientific method of sequential multidimensional and narrowly thematic selection and analysis of literary sources, collection of data on projects of their implementation by construction, differentiation of examples by various criteria, analysis and subsequent integration of the results obtained, the conceptual design of the objects of the children’s educational and game complex of agricultural subjects were carried out. Marine containers of various types were selected as the basis (module).

The reason for choosing shipping containers is their modularity, interchangeability, spatial rigidity, waterproofing, relatively low cost, ease of delivery and installation.

Spatial combinations of containers and planning solutions are determined by the nomenclature of objects of the children’s educational and gaming complex of agricultural subjects; thematic features of individual pavilions; technological features of displaying various types of agricultural production; ergonomic parameters of visitors; organizational features of ensuring convenience and safety of operation; and fire-prevention and sanitary-epidemiological regulations.

The field of conceptual research is limited by the specifics of the spatial organization of tourist sites with a playful organization of the exhibition of agricultural production processes. The research focuses on the spatial planning solutions of individual facilities. The number of objects of various functional attributes included in the complex can be determined at the design research stage. Such a study is possible at the next stage when determining the specific theme of the exhibition (universal or highly specialized), determining the nature of the complex’s work (permanent or seasonal). The selected site of the proposed construction will allow determining the specifics of the spatial location of individual facilities of the complex. The estimated number of visitors will determine the need for auxiliary buildings and facilities of the complex.

The determination of the need to create children’s cognitive and gaming complexes was carried out based on sociological research conducted in the previously mentioned studies by the co-authors of the article [75,76]: I. Ostapenko (agricultural tourism complexes) and E. Schneider (children’s play complexes). As part of this work, relevant sociological surveys were conducted, demonstrating the relevance of developing agricultural tourism in general and educational play complexes in particular.

Schoolteachers showed particular interest. In their opinion, the massive construction of children’s educational and play complexes with agricultural themes in cities and suburbs will be of great educational importance. Children will acquire new knowledge and practical skills in the field of biology and environmentally responsible behavior.

As part of this research, corresponding modeling was conducted, demonstrating the feasibility of implementing this idea. These studies also included surveys of the organizational and spatial structure of several dozen existing agro-eco-tourism complexes and children’s play complexes. The results of these studies are the context of the concept of a children’s educational and game complex of agricultural subjects proposed in this work.

The proposed concept is based on the following structure:

- -

- Fostering environmentally responsible behavior is an important aspect of working with modern children;

- -

- The game is an effective way of learning and education;

- -

- Themed games enhance educational activities;

- -

- The variety and occasional change in game themes ensure constant interest and attractiveness;

- -

- Agricultural production has a wide variety of processes that make it possible to form interesting expositions;

- -

- The agricultural theme of the game shapes environmentally responsible behavior;

- -

- Feasible participation in agricultural production improves the educational process;

- -

- The creation of urban and suburban agricultural-themed play complexes ensures the education of environmentally responsible behavior of children;

- -

- The optimal construction solution for urban and suburban children’s complexes ensures the use of shipping containers.

3. Case Description and Design Context

To determine the need for the formation of urban and suburban children’s play complexes with agricultural themes, the co-authors of the article conducted relevant sociological studies in the process of preparing their scientific papers [75,76]. The personal express survey method is used for this purpose. Groups of students conducted the surveys during an educational orientation internship led by I. Ostapenko and E. Schneider. The research was conducted in the largest agglomerations of Kazakhstan: Almaty, Astana, and Shymkent. The following results were obtained (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11).

Table 1.

Playgrounds with biological themes in the courtyard or on the adjacent territory (Astana city, population 1,612,512 people, 500 respondents).

Table 2.

Playgrounds with biological themes in the courtyard or on the adjacent territory (Almaty city, population 2,314,929 people, 750 respondents).

Table 3.

Playgrounds with biological themes in the courtyard or on the adjacent territory (Shymkent city, population 1,274,296 people, 350 respondents).

Table 4.

Playgrounds with biological themes on school grounds (Astana city, 206 schools, 310,000 schoolchildren, 8240 teachers, 270 respondents).

Table 5.

Playgrounds with biological themes on school grounds (Almaty city, 348 schools, 337,083 schoolchildren, 25,747 teachers, 420 respondents).

Table 6.

Playgrounds with biological themes on school grounds (Shymkent city, 245 schools, 249,748 schoolchildren, 19,000 teachers, 220 respondents).

Table 7.

Playgrounds with biological themes on the territory of the kindergarten (Astana city, 532 kindergartens, 66,119 children, 200 respondents).

Table 8.

Playgrounds with biological themes on the territory of the kindergarten (Almaty city, 824 kindergartens, 65,080 children, 250 respondents).

Table 9.

Playgrounds with biological themes on the territory of the kindergarten (Shymkent city, 526 kindergartens, 78,628 children, 190 respondents).

Table 10.

The common interest in the development of agro-educational activities through the development of agro-tourism complexes.

Table 11.

The interest of city residents in improving children’s playgrounds.

The data obtained showed great interest in the construction of children’s educational and play complexes with agricultural themes.

The interest of focus groups in the formation of children’s educational and play complexes on agricultural topics, revealed based on these surveys, determined the development of an appropriate project proposal. This conceptual solution illustrates the possibility of building modular complexes of various sizes, depending on a specific urban planning context.

4. Results

The concept of forming an agricultural-themed children’s educational and gaming complex based in shipping containers is founded on several prerequisites. The first is the modularity of shipping containers. This allows you to form almost any set of containers for various purposes. The dimensional parameters of sea containers make it possible to take into account almost any technological features of the exposure of agricultural production processes, as well as ergonomic requirements. The modularity of shipping containers makes it possible to replace a damaged unit relatively quickly.

This aspect is part of the adaptability of the proposed system. This is the second premise. Adaptability allows, firstly, adjusting the number of blocks in a particular set depending on organizational and technological changes. Secondly, adaptability ensures the interchangeability of blocks. Thirdly, it is possible to move the pavilion to another site due to administrative and organizational changes. At the same time, modularity allows you to change the number of blocks for various purposes at the new location of the pavilion.

The third prerequisite is the educational function. Play is one of the most effective forms of learning. A playful form of participation in the processes of agricultural production, the opportunity to achieve a real result of their efforts to care for plants and animals is of great educational importance. In the process of observing and participating in agricultural production, children gain knowledge from school courses in botany, zoology, and natural sciences. At the same time, environmentally responsible behavior is being formed.

Examples from global practice show the possibility of solving a large complex of spatial planning and architectural and artistic tasks by reusing marine containers [90,91,92,93,94,95].

The modern practice of reusing shipping containers demonstrates a successful solution for the challenges of effective thermal and sound insulation and adequate ventilation systems for various facilities. The basic configuration of a shipping container ensures reliable protection against corrosion. Technical and technological maintenance is, in most cases, regulated by industry or state standards.

Weather-resistant paints allow for virtually any color scheme for a structure constructed from shipping containers. International practice offers numerous interesting examples of such solutions. Accordingly, agricultural-themed children’s educational play complexes can be designed to reflect the cultural and historical preferences of their users. Specific urban contexts can also be taken into account.

The spatial rigidity of the container allows them to be arranged not only horizontally, but also in vertical or inclined positions. The structural features of containers allow them to be built with different types of transformability of individual surfaces and the entire volume. Usually, the container is installed on four corner supports, for example, made of reinforced concrete or steel elements. In this case, both single-level and multi-level arrangements are used (taking into account the technical characteristics of the loading equipment and the strength of the containers themselves—up to six levels). It is possible to cantilever containers (maximum two in succession) along the long side based on a welded or bolted connection. In addition, the container itself can have a cantilever overhang of up to half its length. World practice provides numerous examples of such solutions. The layout features are provided in numerous works, for example: Connecting containers to each other and Strength characteristics and installation features [96], and Interlocking Experience for Various Objects [97,98,99].

The internal height of sea containers (20-foot and 40-foot) is 2.393 m. This corresponds to state height standards for temporary mobile buildings and structures in most countries of the world. To ensure technological height requirements for some agricultural processes, containers are positioned vertically. These are 5.905 m (20-foot) and 12.032 m (40-foot).

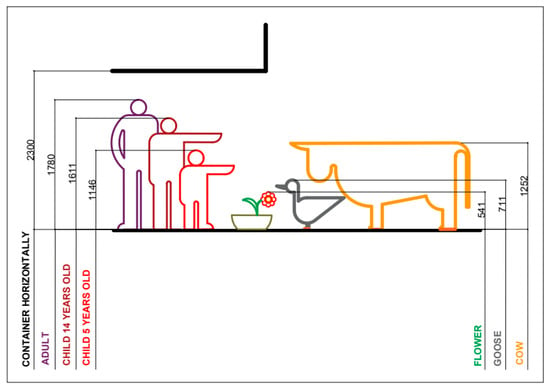

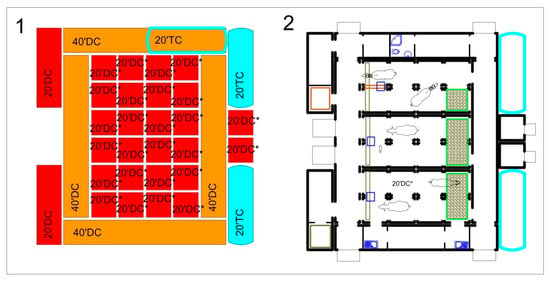

The formation of the exposition and the arrangement of furniture and equipment is carried out based on the ergonomic parameters of visitors and service personnel [100]. Mobile catwalks and ramps are provided in the necessary places for younger children. Figure 1 shows the main parameters (vertical dimensions) of visitors and expositions.

Figure 1.

Main parameters of visitors and expositions. Dimensions given in mm.

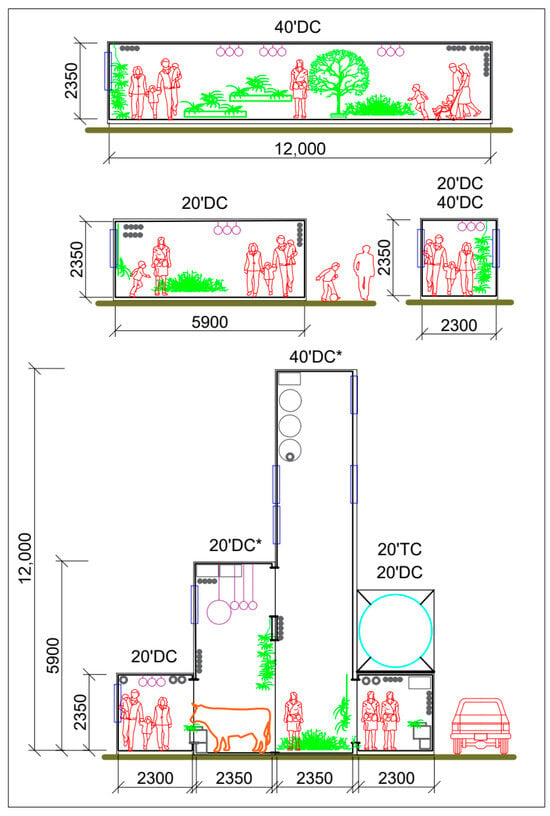

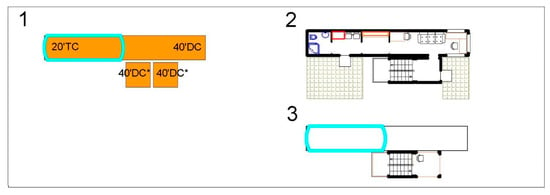

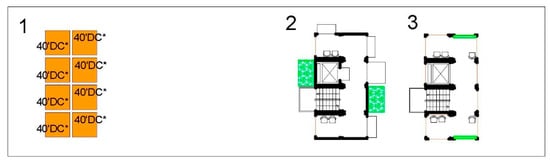

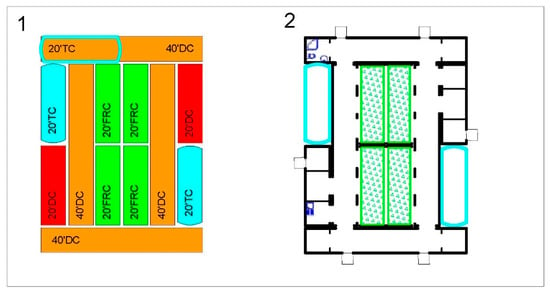

Figure 2 schematically shows longitudinal and cross-sectional views of 20’DC, 20’TC and 40’DS containers, positioned horizontally and vertically. To demonstrate the parametric ease of use, the silhouettes of children and accompanying adults are included in the diagrams.

Figure 2.

Diagrams of 20DC, 20TC and 40DC containers cut (in horizontal and vertical positions). The internal dimensions are given taking into account technologically sound finishes. Dimensions are given in mm. Container combinations are shown conditionally. The asterisk indicates the vertical position of the container.

All proposed spatial solutions are implemented in accordance with current regulations and industry standards. These solutions ensure compliance with agricultural production technology, adequate display of production processes, sanitary and epidemiological control, and the safety of visitors and service personnel.

A complex for children’s educational and recreational agro-tourism may consist of the following blocks for various purposes (this is a complete set of blocks for suburban complexes of autonomous operation; for inner-city complexes, separate groups of blocks are selected that correspond to the subject and context).

Blocks for engineering, technical and auxiliary personnel: an administrative block; a block of rooms for the work of the staff on duty serving visitors; a block of rooms for the rest of the staff on duty; a block of household rooms for staff; a block of a guard post; a checkpoint.

Visitor service blocks: a tour desk; hotels; family cottages; a dining room; a grocery store; a gift shop; a high-rise observation deck; a children’s play block; a club; a relaxation complex; a picnic complex; complexes with reservoirs for entertainment fishing with a fishing rod and a net in combination with demonstration aquariums; a complex for visitors’ dogs; wardrobes at sports grounds; a covered parking for visitors’ cars; a maintenance complex for visitors’ cars; a public bathroom (toilets + showers); a self-service kitchen; a self-service laundry; a room for heating and drying clothes; a medical center.

Blocks for exhibiting agricultural production: keeping horses, ponies, camels, cows, pigs, sheep, goats, rabbits, nutria, fighting dogs, guard dogs, hunting dogs, chickens, ducks, pheasants, ostriches, hunting birds, songbirds and ornamental birds; breeding mushrooms, vegetables, fruits, berries, flowers, snails, fish, crayfish, frogs, turtles, and insects.

Blocks for exhibiting the processing of agricultural products: preparation of carbonated beverages, juices, jams, compotes; smoking and drying of fish and meat; drying of mushrooms, berries, fruits, herbs and flowers; cheese preparation; preparation of animal feed, fish, shellfish, and insects.

Blocks for the exhibition of regional cuisine and crafts: preparation of dairy, meat and fish products; the production of leather, wood, clay, metals, wool; and a manufacture of parts for a traditional dwelling.

Warehouses: furniture; tableware; cutlery; technological equipment; firefighting, technical, cleaning, fishing, hunting, sports, entertainment and relaxation equipment; clean uniforms; dirty uniforms; clean bed linen; dirty bed linen; reagents and detergents for laundry; dry products, spices, containers and packaging; firewood, coal, fuel briquettes; feed, fertilizers, and solid household waste.

Refrigerating chambers: meat, fish, dairy products and semi-finished products; confectionery; vegetables, fruits, berries, mushrooms, canned food, beverages, and food waste.

Engineering and technical premises: pumping, transformers, aggregates, boiler rooms, server rooms, wind and solar-electric generators; carpentry and locksmith workshops, workshop for minor repairs; tanks for liquid fuels, biofuels, gas, drinking water, recycled water supply, water treatment for fisheries, and filtration equipment.

The nomenclature of sea containers allows forming all the necessary blocks using containers directly or with appropriate transformation. The containers’ structure (with the exception of platform containers) provides the possibility of arranging containers in one or more tiers. Containers can be located both on the ground and in a semi-underground or underground position, depending on the technological process in which they are used. This is especially true for tank containers, which, in order to provide additional pressure in the domestic water supply system and ease of emptying, can be located at the next level above the room in which their contents are used. If they used a water tower or firefighting tanks as reservoirs, they could have independent supports or be placed at a higher point of the surrounding landscape. The storage of gas fuel implies a strictly ground-based arrangement of tanks, and it is advisable to organize the storage of liquid fuel in an underground version. In addition, the underground location is typical for atmospheric wastewater storage tanks and components of the circulating water supply system.

However, most services and activities in tourist complexes require varying degrees of container transformation. It is necessary to install window and door openings; special interior decoration is necessary, corresponding to technological processes. A separate issue is pipelines and cables of engineering support systems. Combinatory, unlike singly located containers, requires the installation of a common pitched, quick-mounted roof.

The modern practice of adapting containers as separate WC and bathrooms is widespread. However, their layout, based on minimizing the parameters of the main premises and amenities, is unacceptable for use in children’s tourist complexes, as it does not provide a sufficient level of comfort. In addition, the requirements for accessibility of low-mobility groups of the population are usually not taken into account. The same problems occur with the layout of residential premises.

Examples of container farms often used in cities for the cultivation of plants, fungi, edible insects and fish are unsuitable as demonstration and entertainment material due to spatial limitations. These technological solutions do not imply the possibility of conducting excursions and demonstrations and cognitive observation of the process by visitors, and even more so exclude the participation of anyone other than specially trained personnel. Such decisions cannot be elements of an exhibition—an educational and playful attraction [101,102,103,104].

Premises for plant disease control, veterinary services for fish, birds and animals, and slaughter of livestock do not belong to the sphere of demonstration to children at all. Their modular solution of containers can only be an addition to the range of objects of the tourist complex. This kit also includes modular container gas stations, which in the structure of the tourist complex are designed to service passenger cars and buses on which parents with children or organized groups of children with instructors arrived.

In the context of organizing an entertainment and educational program for agricultural tourism, ensuring its attractiveness, and the need to create a sufficient level of comfort for visitors and staff of tourist enterprises, massively used layouts are unacceptable. A high level of comfort of stay and the maximum possible provision of an educational and entertainment component is an essential part of the economic success of these enterprises.

Depending on the specific conditions of placement, the thematic orientation of the Children’s educational and gaming complex (crop growing, poultry farming, livestock farming, fish farming, mixed-use, combined-use), seasonality (seasonal use, year-round use), its capacity, availability of certain capacities of engineering support systems, and the proposed planning solutions can be adjusted and supplemented with a block containers of aggregates, transformers, boilers, pumps, warehouses, and reservoirs.

In layouts presented below, the size of the seam between the blocked containers is shown conditionally. Its width depends on the specifics of the layout of containers located in horizontal and vertical positions.

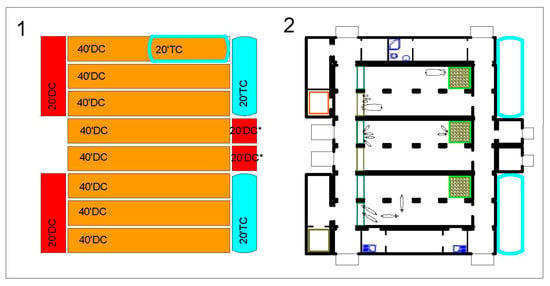

It is proposed to use several types of shipping containers individually and in various combinations to organize a Children’s educational and entertainment complex with agricultural themes.

A container 40’DC (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 12.192 × 2.438 m: a warehouse of dishes, furniture, equipment, tools, inventory, bedding, work clothes, dry food, dry products, detergents, consumables, fuel briquettes, firewood, fertilizers; a wind generator; a solar generator; a gas-diesel electric generator; a gas-diesel boiler house; and a temporary isolation unit for animals and birds. A container 40’RF (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 2.192 × 2.438 m: a refrigerator for meat, dairy, fish, vegetable, fruit semi-finished products, beverages, ice cream; a refrigerated chamber for food waste.

A container 20’DC (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 6.058 × 2.438 m: an aggregate; a pumping station; a transformer; a furniture warehouse, household and entertainment equipment, and consumables.

A container 20’OTC (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 6.058 × 2.438 m: a swimming tank; a demonstration and fishing aquarium; a pond for geese and ducks; a temporary container for bulk building materials, and coal.

A container 20’FRC (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 6.058 × 2.438 m: a block of greenhouses, temporary storage, temporary housing of animals and birds, placement of special fire-fighting equipment and materials, and used containers and packaging.

A container 20’TC (in single and in complete, in the basic configuration and adapted) 6.058 × 2.438 m: a container for storing: drinking water, water from the recycling water supply system, fire water supply, liquid fuel, gaseous fuel, and filtration tank for water treatment for fisheries.

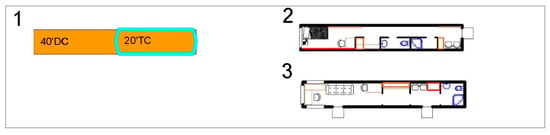

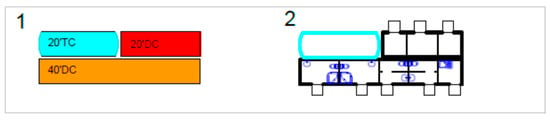

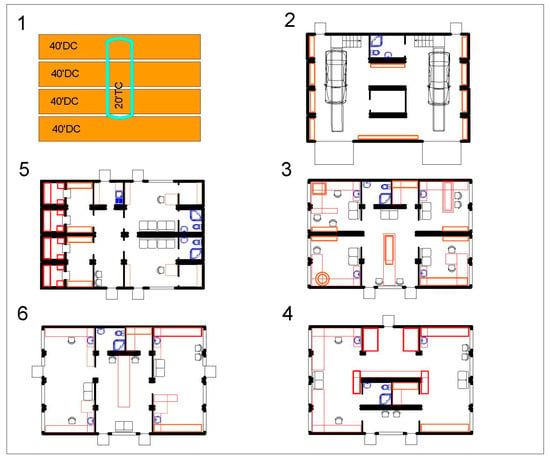

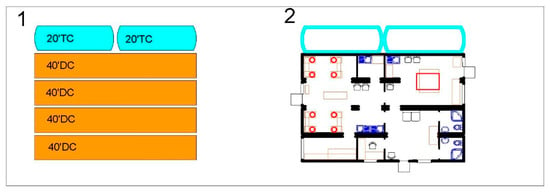

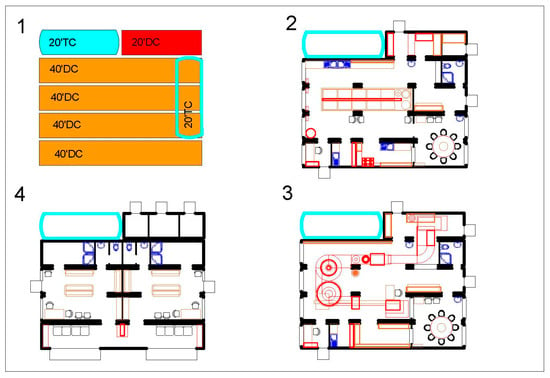

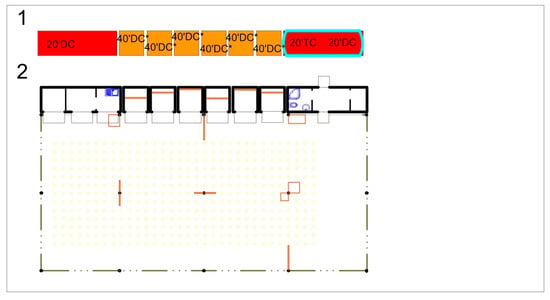

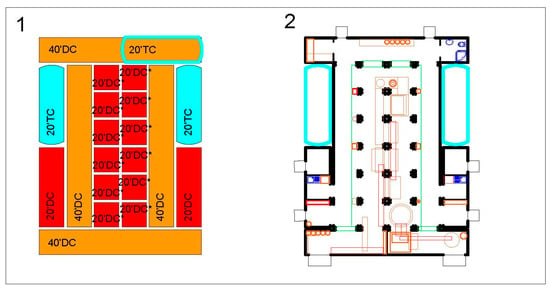

Set 1 (Figure 3): a Single hotel room and a Checkpoint. The pavilion of the Single hotel room: an entrance hall of 4.5 sq. m; a corridor of 5.0 sq. m; a toilet of 2.0 sq. m; a shower room of 2.0 sq. m; a storage room of 2.5 sq. m; a bedroom of 11.0 sq. m. The furniture includes a single bed with a bedside table, cupboards, shelves, table and chairs. Cooking not provided in the room. The Checkpoint pavilion: a staff room of 13.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 4.5 sq. m; a hallway of 5.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.0 sq. m. The pavilion is designed for the simultaneous stay of two employees of the duty shift who control access to the territory of the Complex.

Figure 3.

Set 1: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Single hotel room; 3—the plan of a Checkpoint. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

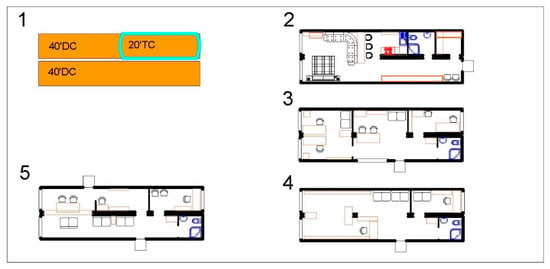

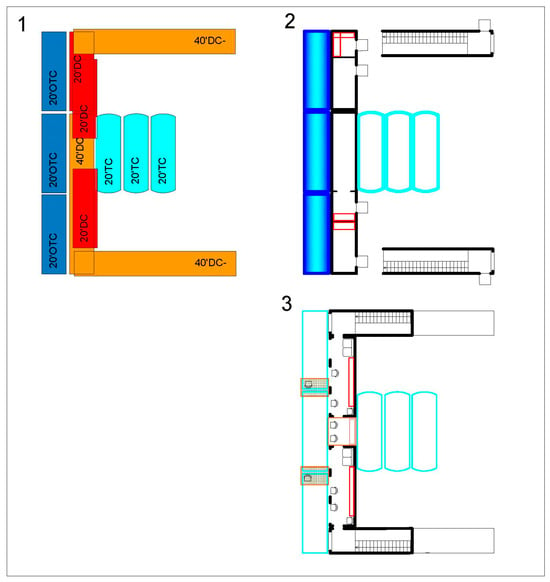

The Set 2 (Figure 4): a Double hotel room, an Administrative premise, a Souvenir shop and a Tour desk. The Pavilion of the Single-double hotel room: an entrance hall of 13.5 sq. m; a storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a kitchen niche of 4.5 sq. m; a bedroom of 27.0 sq. m. The furniture includes a double bed with bedside tables, a corner sofa, a dining table, cupboards, shelves, chairs. The Administrative pavilion: a reception area of 22.5 sq. m; an office of the head of 9.0 sq. m; a staff office of 18.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m. The pavilion is designed for five office staff members. The Souvenir shop pavilion: a lobby of 5.0 sq. m; a sales hall of 36.0 sq. m; an office of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.0 sq. m. The pavilion is designed to sell souvenirs to visitors, thematically related to the specifics of this Complex. The Tour desk pavilion: a reception area of 13.5 sq. m; a tour registration area of 18.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; an office of 9.0 sq. m; a utility room of 9.0 sq. m. The pavilion is designed for the work of three office staff members who carry out the registration of the visitors’ stay in the Complex, forming their individual or group excursion program.

Figure 4.

Set 2: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Double hotel room; 3—the plan of a Block of administrative premises; 4—the plan of a Souvenir shop; 5—the plan of a Tour desk. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

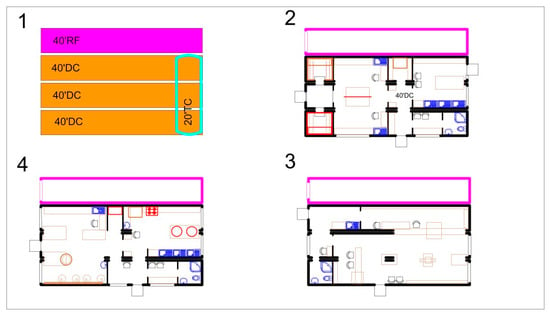

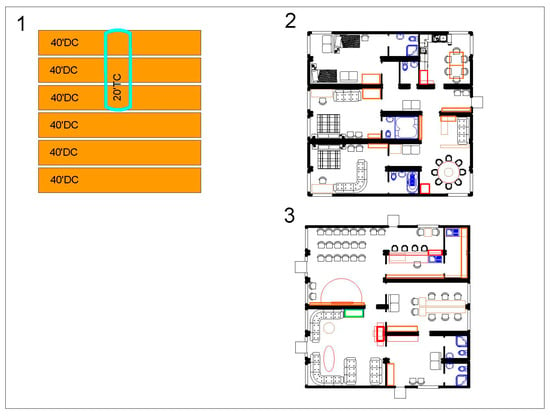

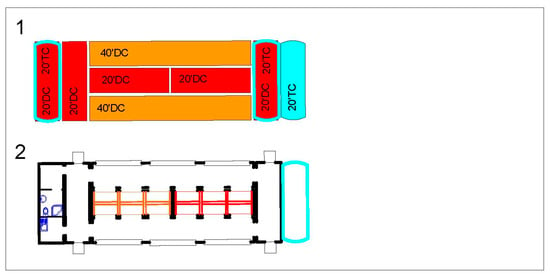

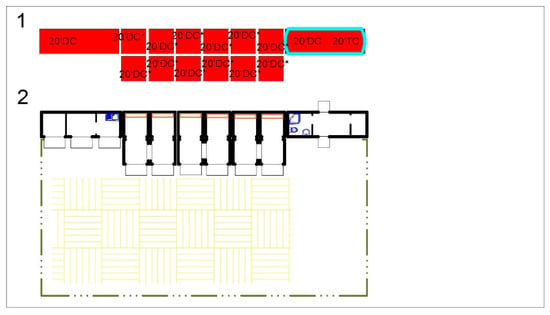

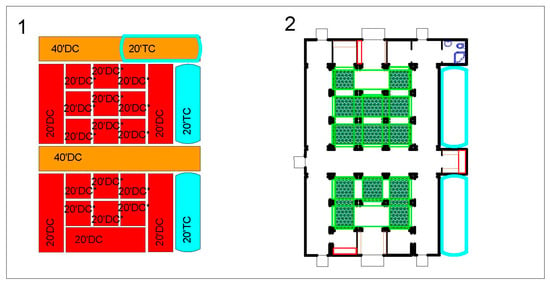

Set 3 (Figure 5): a Territory guard post. The Security pavilion: a staff room of 13.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 4.5 sq. m; a hallway of 5.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.0 sq. m; an observation tower with a stairwell and observation platforms of 4.5 sq. m each at heights of 2.8 m, 5.6 m, and 8.4 m. Staircases have remote intermediate platforms. The pavilion is designed for the simultaneous stay of three duty shift staff members who carry out visual and instrumental control of the Complex from observation decks located at various heights of the observation tower.

Figure 5.

Set 3: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Territory guard post (first level); 3—the plan of a Territory guard post (second level). The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment. The asterisk indicates the vertical position of the container.

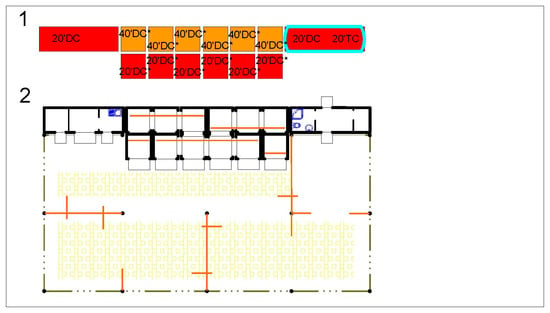

Set 4 (Figure 6): a public toilet unit. The Public toilet pavilion: two bathrooms for low-mobility groups of 6.0 sq. m each; two toilets of 5.0 sq. m each; a storage room for cleaning equipment of 5.0 sq. m; an aggregate of 4.0 sq. m; an inventory of 5.5 sq. m; a utility room of 4.0 sq. m; and a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m.

Figure 6.

Set 4: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—plan of a Public toilet. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

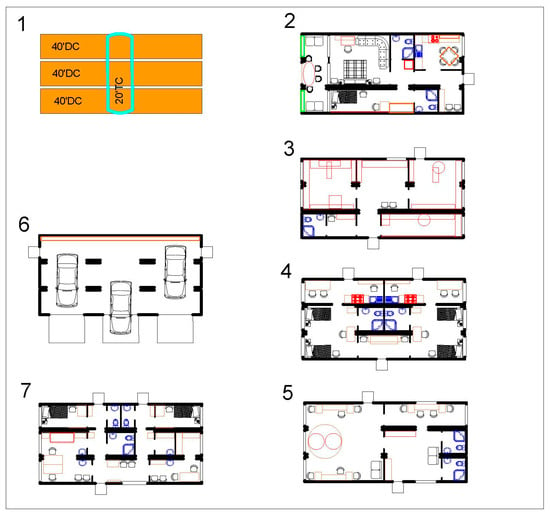

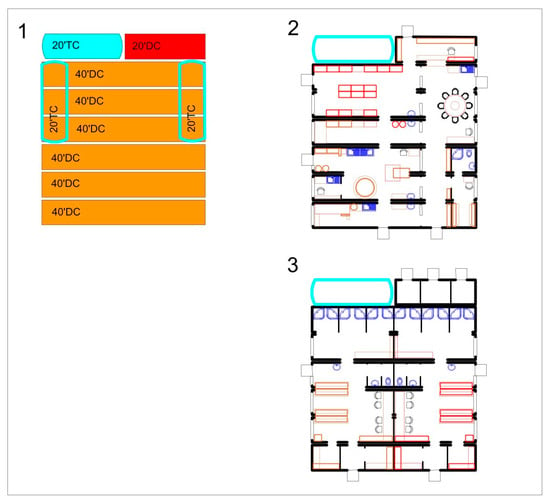

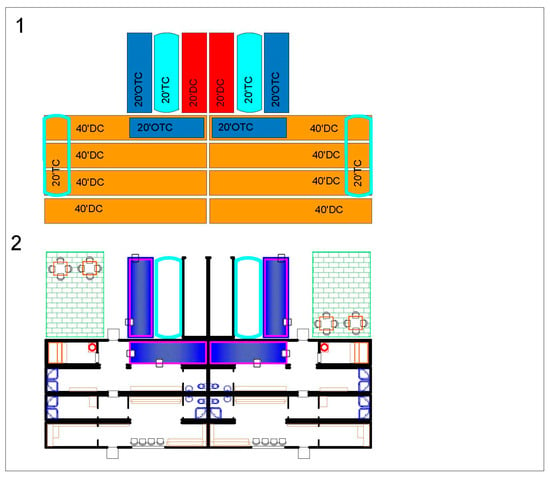

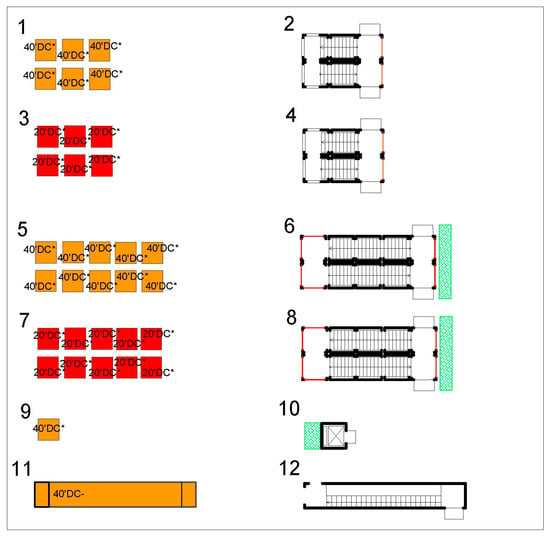

Set 5 (Figure 7): a Covered parking for visitors’ cars, a medical center, a Triple hotel room, workshops (carpentry, locksmithing, minor repair workshop), Recreation rooms for staff on duty and a Pavilion for children’s games. The Pavilion of the two- and three-bed hotel room: an entrance hall of 10.5 sq. m; a kitchen of 12.0 sq. m; a hall of 4.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a bedroom of 18.0 sq. m; a bedroom of 11.0 sq. m.; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; and a loggia of 13.5 sq. m. The furniture includes single and double beds with bedside tables, a corner sofa, a dining table for four people in the kitchen, tables, cabinets, shelves, chairs, garden sofas and a table with chairs on the loggia. The pavilion of a carpentry or locksmith workshop, a workshop for minor repairs: a distribution area of 4.5 sq. m; a staff room of 5.0 sq. m with a bathroom of 4.0 sq. m; three adjacent workshop rooms of 18.0 sq. m each. The pavilion is designed for routine repairs of furniture, equipment and inventory used in the Complex. The number of employees is seven people. Recreation pavilion for staff on duty: a lobby of 9.0 sq. m; two rest rooms of 18.0 sq. m with bathrooms of 4.5 sq. m; two meal rooms of 13.5 sq. m. The pavilion is planned as two symmetrical compartments with the same set of rooms providing rest and meals for eight (4 + 4) staff members on duty.

Figure 7.

Set 5: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan for a Triple hotel room; 3—plans of a Carpentry workshop, a Locksmith workshop or a Workshop for minor repairs; 4—the plan of Rest rooms for staff on duty; 5—the plan of a Block for children’s games; 6—the plan for an Indoor parking of visitors’ cars; 7—the plan for a Medical center. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

The Children’s play pavilion: a lobby of 18.0 sq. m.; two bathrooms of 4.5 sq. m each; a game room of 13.5 sq. m; a game room of 40.5 sq. m. The pavilion is designed for organizing play activities for children of primary and secondary school age from the families of visitors in the presence of three tutors on duty. The Covered parking for visitors’ cars: a room with three open parking spaces of 81.0 sq. m. It is possible to store some of the brought items on open shelves. The Pavilion of the medical center: a lobby of 9.0 sq. m; an office of 9.0 sq. m with a medicine storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; an office of 16.0 sq. m; two corridors of 2.5 sq. m each; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a storage room of 3.0 sq. m; two chambers of 13.5 sq. m each with toilets. The pavilion is designed to provide emergency and preventive medical care to visitors and employees of the Complex. The staff on duty consists of four people (one general practitioner, one trauma surgeon, two procedural nurses). Two isolated rooms with independent entrances are designed for patients waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

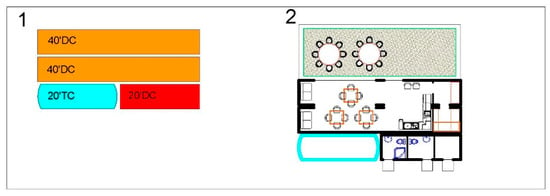

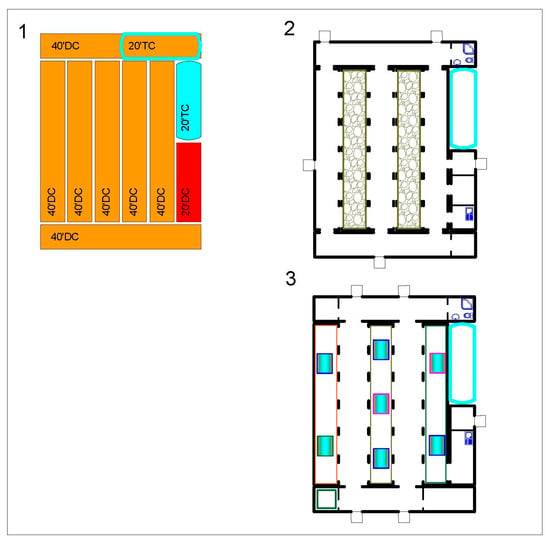

Set 6 (Figure 8): a Picnic unit. The Picnic pavilion: a covered recreation area of 45.0 sq. m; adjacent storerooms of equipment and inventory of 4.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a toilet of 4.5 sq. m, planned while taking into account the needs of low-mobility groups of the population; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m; and an outdoor area of 60.0 sq. m. Having preordered the delivery of the necessary products and semi-finished products, visitors can prepare the necessary dishes for a picnic on their own or with the help of staff and serve them appropriately (rented or one-time dishes and cutlery) on tables of various capacities placed in the pavilion or on an outdoor area (platform, lawn, ground).

Figure 8.

Set 6: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Picnic block. The black lines indicate the design of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

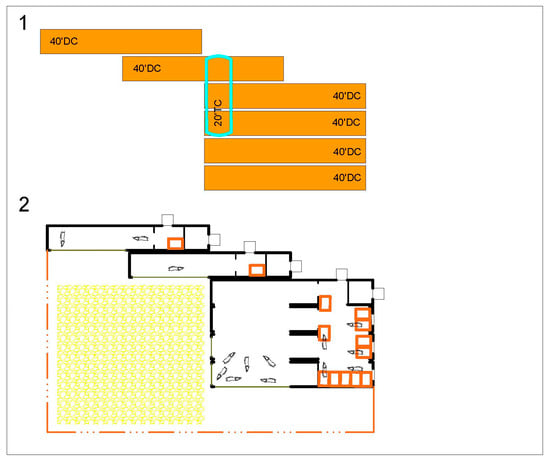

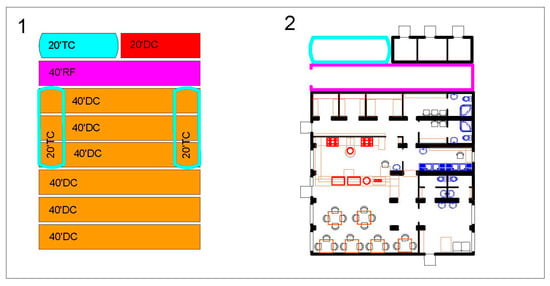

Set 7 (Figure 9): a Service station for visitors’ cars, an Exhibit of the traditional processing of materials (leather, wood, metals and clay), Household premises (heating, drying clothes and shoes) and a Manufacturing elements of a traditional dwelling, a Traditional weaving and wool processing area. The Visitors’ car maintenance station: two interconnected repair rooms of 40.0 sq. m with observation pits; two repair and distribution areas of 7.0 sq. m; an inventory of 7.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 7.0 sq. m. Visitors can either order certain types of repairs, or, after consulting, independently carry out a number of maintenance activities. The Pavilion for the demonstration of traditional leather, wood, clay and metal processing: distribution area of 27.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a workshop for the production of leather goods of 18.0 sq. m; a workshop for the production of wood products of 18.0 sq. m; a workshop for the production of clay products of 18.0 sq. m; a workshop for the production of metal products of 18.0 sq. m. Through a distribution area in which samples of the work of folk craftsmen are put up for sale, visitors can enter the workshops for the manufacture of leather, wood, clay and metal products. Here they can observe the work of artisans and, after donning overalls and being instructed, take a direct part in the production.

Figure 9.

Set 7: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Visitors’ car service station; 3—the plan of a Block for exhibiting traditional leather, wood, metals and clay processing; 4—the plan of a Block for the manufacture of elements of a traditional dwelling; 5—the plan of a Block for heating, drying clothes and shoes; 6—the plan of a Block for traditional weaving and wool processing. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

The Pavilion for demonstrating the manufacture of traditional dwellings (an izba, an yurt, a hut, a wigwam, a chum, a yaranga, a saklya, an urasa, etc.): a distribution area of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a workshop for preparing bars of 36.0 sq. m; a storage area for blanks and a complete set of products of 36.0 sq. m. Through the distribution area, visitors enter the workshops where they can observe and, after a briefing and putting on work clothes, take part in the manufacture of elements. The Pavilion for heating and drying clothes and shoes: a distribution area of 13.5 sq. m; a cleaning equipment room of 4.5 sq. m; two adjacent drying rooms of 18.0 sq. m with four drying chambers; two adjacent heating rooms of 18.0 sq. m with bathrooms of 4.5 sq. m and utility rooms of 4.5 sq. m. The pavilion is designed for heating and drying clothes and shoes of visitors walking around the Complex. The heating room is divided into male and female parts with independent entrances from opposite sides. These planning areas are connected. The capacity of each unit is seven people staying at the same time. The Pavilion for the demonstration of traditional weaving and wool processing: a distribution area of 27.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a storage room of 4.5 sq. m; a felt workshop of 36.0 sq. m; and a weaving workshop of 36.0 sq. m. The products of weaving and felt crafts are on sale in the distribution area. From there, visitors can enter the workshops for creating felt products and weaving production. After the briefing, they can participate in the product-shaping process.

Set 8 (Figure 10): a Shop for the exhibition of drying and smoking fish or meat, a Local grocery store, a Kitchen for the exhibition of cooking of local dishes. The Pavilion for the demonstration of drying and smoking fish or meat: a vestibule of 4.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 5.0 sq. m with a bathroom of 4.0 sq. m; a distribution area of 4.5 sq. m; a cutting room of 18.0 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a preparation room of 27.0 sq. m; a vestibule of 4.5 sq. m; two drying/smoking chambers of 4.5 sq. m each; refrigerated chambers for meat and fish of 27.0 sq. m. Guided by a guide and dressed in disposable protective robes and gloves, visitors can observe and take part in cutting food, preparing semi-finished products for the drying and smoking processes, loading and unloading the smoking and drying chambers under the guidance of specialists.

Figure 10.

Set 8: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Shop for the exhibition of drying and smoking fish or meat; 3—plan of the Local grocery store; 4—the plan of a Kitchen for the exhibition of cooking of local dishes. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

The Pavilion of the local food store: a sales hall of 63.0 sq. m; a goods preparation room of 9.0 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a refrigerator of 27.0 sq. m. The pavilion is designed to sell a range of locally produced products and related products to visitors. Visitors can choose packaged goods on the shelves in the self-service hall or ask for a hanging product from a refrigerated counter or from a rack. The store staff consists of four people. The Pavilion for the demonstration of cooking traditional cuisine: a distribution area of 6.0 sq. m; a cloakroom of 5.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a storage room of 2.0 sq. m; a meat and fish shop of 27.0 sq. m; a dairy of 26.5 sq. m. Visitors in the distribution area wear disposable protective gowns and hats. Then, under the guidance of a guide, they go to the workshops for the production of products from milk, meat, fish, vegetables and fruits. Here they can observe the production process and personally participate in the preparation of products under the guidance of specialists.

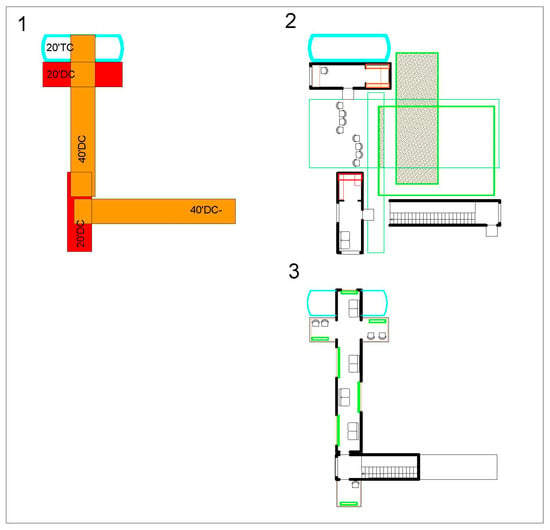

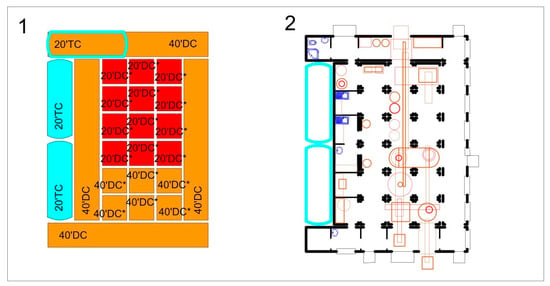

Set 9 (Figure 11): an Individual or group relaxation unit. The Relaxation pavilion: a recreation room of 9.0 sq. m; an inventory storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a staff room of 9.0 sq. m; a furniture storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a sloping gallery of 27.0 sq. m with stairs and a ramp leading to the second level. On the second level, there is a relaxation pavilion of 27.0 sq. m, three outdoor areas of 4.5 sq. m each. Visitors can sit comfortably on sun loungers, armchairs, sofas, chairs or mats, spend time relaxing, meditating, observing the surroundings in various directions, in outdoor and indoor areas or in pavilions located on two levels. A covered staircase with a ramp leads to the second level, taking into account the needs of low-mobility groups of the population.

Figure 11.

Set 9: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of an Individual or group relaxation unit (first level); 3—the plan of an Individual or group relaxation unit (second level). The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Set 10 (Figure 12): a Self-service kitchen unit. The Self-service kitchen pavilion: a distribution area of 9.0 sq. m; a hot food preparation room of 40.5 sq. m; a cold food preparation room of 18.0 sq. m; an utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 4.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; an aggregate of 4.5 sq. m; an inventory of 9.0 sq. m; a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m. The pavilion is designed so that visitors can, if desired, change their clothes in the cloakroom, prepare their own food for themselves and, packaged in containers and thermoses, take it to their hotel rooms or outdoor areas. Four four-burner gas stoves provide the possibility of eight people working simultaneously. There are consultants in the rooms for cooking hot and cold dishes. A separate service is the provision of culinary master classes by specialists for visitors, where the peculiarities of cooking and serving locally produced products are demonstrated.

Figure 12.

Set 10: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Self-service kitchen. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Set 11 (Figure 13): an Exposure unit for breeding chickens or pheasants. The Demonstration pavilion for keeping chickens or pheasants: two poultry houses (outdoor) of 9.0 sq. m; two feed rooms of 6.8 sq. m; two feed preparation rooms of 4.5 sq. m; two inventory rooms of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a staff room of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; two outdoor enclosures of 140.0 sq. m fenced off with a 2.5 m high net. Visitors pass through the staff room, where they receive instructions, to the aviaries, where they can inspect the poultry houses, observe the collection of eggs, walk among the birds, take part in their feeding and cleaning of the aviaries.

Figure 13.

Set 11: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Display unit for breeding chickens or pheasants. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Set 12 (Figure 14): a Self-service laundry unit. The Self-service laundry pavilion: a hall of 24.0 sq. m; two bathrooms of 5.8 sq. m each; duty room of 5.8 sq. m; laundry room of 52.0 sq. m (8 washing machines); a soap and detergent warehouse of 11.6 sq. m; a utility room of 5.8 sq. m; an ironing room of 34.8 sq. m; two water tanks of 25.0 cubic m. The unit is intended for visitors and staff who want to do their own laundry.

Figure 14.

Set 12: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Self-service laundry. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

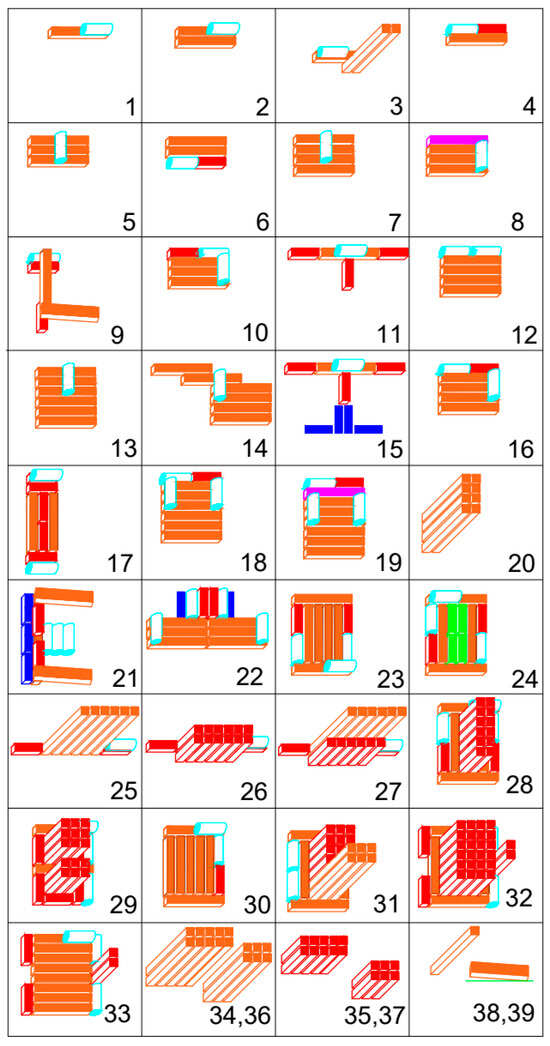

Set 13 (Figure 15): units of a Family cottage and a Leisure Club. The Family cottage: an entrance hall of 9.0 sq. m; a kitchen of 18.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 2.5 sq. m; a corridor of 8.0 sq. m; a living room of 33.0 sq. m; a bedroom of 27.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 5.0 sq. m; a bedroom of 20.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 6.0 sq. m; a bedroom of 22.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m. The Pavilion is furnished with single and double beds with bedside tables, upholstered furniture, tables, shelves, cupboards, chairs, a kitchen table for six people, and a dining table for eight people in the living room. A single pavilion location is possible, as well as a multi-level solution with an additional staircase and elevator nodes.

Figure 15.

Set 13: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Family cottage; 3—the plan of a Leisure club. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

The Leisure pavilion-club: a lobby of 18.0 sq. m with two bathrooms of 4.5 sq. m each; a recreation room of 40.5 sq. m; a computer room of 27.0 sq. m; a concert hall of 40.5 sq. m; a buffet-bar of 18.0 sq. m; a buffet utility room of 9.0 sq. m. Visitors enter the lobby, which houses seating areas and closets. Bathrooms are also located here. From the lobby there is an entrance to the computer room for eight visitors and a quiet relaxation room with a fireplace and an aquarium, furnished with sofas. The hall is designed for the simultaneous stay of twelve to fifteen people. The passage leads to a cinema and concert hall with a variety podium and seats for eighteen spectators. Adjacent to it is a buffet bar with six seats and a utility room. The number of service personnel is six people. Visitors entering the distribution area get acquainted with the layout of the pavilion, which shows the locations of various technological processes, receive a brief briefing from the guide and, accompanied by him, go to the central part, observing the automated process on the conveyor (loading, washing, inspection, crushing, pulp processing, pressing, straining, juice collection, heating, cooling, separation, blending, sweetening, filtration, de-aeration, heating, preparation of containers and lids, packing, sterilization, labeling, warehousing).

Set 14 (Figure 16): an Exhibition block for breeding hunting and service dogs or the temporary accommodation of visitors’ dogs. The Pavilion for the demonstration of dog breeding or temporary accommodation of dogs brought by visitors: partially open on one side and having a mesh fence, a pavilion for single keeping of fighting dogs of 27.0 sq. m with a booth and a utility room; partially open on one side and having a mesh fence, a pavilion for paired keeping of guard dogs of 27.0 sq. m with a booth, a platform and a utility room; the pavilion for keeping hunting dogs (hounds, greyhounds, burrows, cops, retrievers, spaniels, huskies, setters), partially open on both sides and with a mesh fence, is 108.0 sq. m with booths, platforms and a utility room. The open parts of the pavilions are visually isolated from each other to reduce the anxiety of the inhabitants of neighboring pavilions. Visitors, instructed and accompanied by a guide, can approach the open part of the pavilion to observe the maintenance of dogs of various species, take part in feeding animals and cleaning enclosures. Separate entertainment may include participation in dog walking in an open area, training guard dogs at a training ground, and recreational dog hunting on foot or horseback with appropriate equipment. Visitors who come with their dogs can rent an appropriate free, pre-prepared pavilion for them, conduct training at the training ground under the guidance of dog handlers, and receive advice from a trainer and veterinarian.

Figure 16.

Set 14: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—The plan of a Display unit for breeding of hunting and service dogs or temporary maintenance of visitors’ dogs. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Set 15 (Figure 17): an Exposure unit for breeding ducks or geese. The Pavilion for the demonstration of ducks or geese: two poultry houses (outdoor) of 9.0 sq. m, two feed rooms of 6.8 sq. m, two feed preparation rooms of 4.5 sq. m, two inventory rooms of 4.5 sq. m, a utility room of 4.5 sq. m, a staff room of 9.0 sq. m, a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m, two open-air enclosures of 140.0 sq. m each with four reservoirs of 12.0 sq. m of open surface, fenced with a 2.5 m high grid. Visitors pass through the staff room, where they receive instructions, to the aviaries, where they can inspect the poultry houses, observe the collection of eggs, carefully, together with a guide to avoid aggressive behavior of geese, walk among the birds, take part in their feeding at reservoirs and cleaning the aviaries.

Figure 17.

Set 15: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Display unit for breeding ducks or geese. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

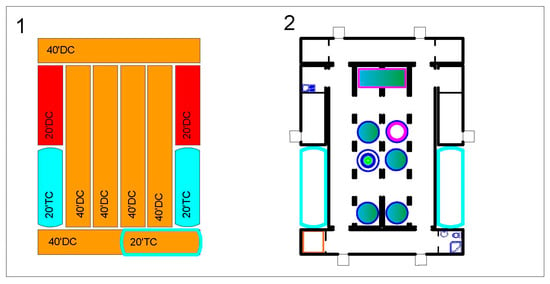

Set 16 (Figure 18): units for the Exhibition of juice production, the Cultivation of edible insects, and the Wardrobe of the sports grounds. The Edible insect breeding demonstration pavilion: distribution area of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a raw materials reception and waste disposal room of 13.5 sq. m; a production room of 58.5 sq. m; a laboratory of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a warehouse of finished products and cooking of 9.0 sq. m; a tasting room of 18.0 sq. m; a water preparation tank of 25.0 cubic m.

Figure 18.

Set 16: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of an Edible insect cultivation unit; 3—the plan of a Juice production unit; 4—the plan of a Wardrobe for sports grounds. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Visitors entering the distribution area are acquainted with the layout of the pavilion, which shows the locations of various technological processes, receive a brief briefing from the guide and, accompanied by him, go to the central part, examining the tiered boxes with cultivated insects (silkworms, lacquer worms, crickets, wax worms, cockroaches). The route leads along the outside of the racks. Next, you can familiarize yourself with the sorting and packing process. Visitors may participate in the production process. The final stage is product tasting. The Pavilion for the demonstration of production and tasting of juices: a distribution area of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a reception room for raw materials of 13.5 sq. m; a production room of 58.5 sq. m; a laboratory of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a finished goods warehouse of 9.0 sq. m; a tasting room of 18.0 sq. m; a water treatment tank of 25.0 cubic m. The route leads along the inside of the conveyor. Direct participation of visitors in the production process is not provided. The final stage is product tasting. The Sports grounds cloakroom pavilion (two adjacent complexes of rooms): locker room of 13.5 sq. m; a toilet of 4.5 sq. m; a shower room of 9.0 sq. m. A semi-open gallery of 27.0 sq. m is connected to the complexes; an aggregate of 4.5 sq. m; a sports equipment storeroom of 5.5 sq. m; a cleaning equipment storeroom of 3.0 sq. m; a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m. The pavilion is designed for changing clothes of teams participating in physical culture and sports events. The simultaneous capacity is thirty (15 + 15) people.

Set 17 (Figure 19): an Exposure unit for breeding rabbits or nutria. The Rabbit or nutria demonstration pavilion: two distribution zones of 13.5 sq. m; two galleries of 27.0 sq. m; two interlocked animal holding areas of 13.5 sq. m; utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room with bathroom of 9.0 sq. m; a water treatment tank of 25.0 cubic m. Visitors entering the distribution area get acquainted with the layout of the pavilion, which indicates the locations of various areas. They put on disposable protective robes, hats, shoe covers, gloves, receive a brief briefing from a tour guide and, accompanied by him, walk through the galleries, and if desired, participate with the staff in the production processes of feeding and cleaning aviaries that come along the way. The circular route leads along a three-level system of thirty-six aviaries with side natural and overhead special artificial lighting.

Figure 19.

Set 17: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Display unit for breeding of rabbits or nutrias. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Set 18 (Figure 20): units of Household premises for staff and Cheese production exhibits. The Cheese production and tasting pavilion: a gallery of 13.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 9.0 sq. m; a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a tasting room of 27.0 sq. m; a camera storage of finished products of 13.5 sq. m; a maturation chamber of 36.0 sq. m; a salt department of 18.0 sq. m; a production room of 30.0 sq. m; a laboratory of 6.0 sq. m; a reception department of 18.0 sq. m. Visitors entering the distribution area get acquainted with the layout of the pavilion, which shows the locations of various technological processes; they put on disposable protective robes, hats, shoe covers, gloves, receive a brief briefing from the guide and, accompanied by him, go to the production facilities.

Figure 20.

Set 18: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Block of cheese production; 3—the plan of a Block of household premises for staff. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

Here they can observe the entire technological chain of production: milk production, maturation, normalization, pasteurization, coagulation, rennet processing, molding, pressing, salting, maturation, pre-sale preparation. In the final distribution area of the circular route, visitors can take part in a tasting of the drinks produced (the capacity of the tasting room is ten seats). Household premises for staff (two adjacent complexes of rooms): a vestibule of 4.0 sq. m; a dirty uniform storeroom of 5.0 sq. m; a clean uniform storeroom of 4.5 sq. m; a dressing room of 36.0 sq. m; a toilet of 4.5 sq. m; a shower room of 27.0 sq. m. The aggregate area of 4.5 sq. m is interconnected with the complexes; a pumping station of 3.5 sq. m; a utility room of 5.5 sq. m; a tank of clean water of 25.0 cubic m. The pavilion is planned to be symmetrical, having men’s and women’s departments. The capacity of the pavilion is forty (20+20) people staying at the same time. The furniture includes wardrobes with two compartments for each visitor, tables, chairs, benches, linen closets, and chests for dirty work clothes. Both a single-level pavilion layout and a multi-level solution are possible.

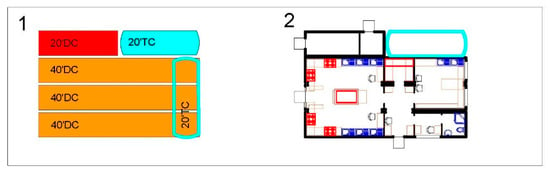

Set 19 (Figure 21): a Dining room unit. The Dining room pavilion: a lobby of 18.0 sq. m; two toilets of 4.5 sq. m; a dining room of 54.0 sq. m; a kitchen of 17.0 sq. m; a dishwasher of 12.0 sq. m; a wardrobe of 5.0 sq. m with a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a wardrobe of 7.0 sq. m with a bathroom of 4.5 sq. m; a corridor of 11.0 sq. m; two food pantries of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 6.0 sq. m; a refrigerator of 27.0 sq. m; an aggregate of 4.5 sq. m; a utility room of 3.5 sq. m; a food waste storage of 5.5 sq. m; a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m. The pavilion is designed to provide three to four hot meals a day to visitors of the Complex and part of the staff. The simultaneous capacity is twenty people; the kitchen staff is six people. It is possible to organize events for tasting local products. The kitchen also fulfills the orders of the visitors to the Complex, preparing and delivering food to hotel rooms, cottages, picnic areas, and recreation pavilions. Food is also delivered to the premises of entry and exit security, territory security, and the rest of the staff on duty.

Figure 21.

Set 19: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Dining room. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

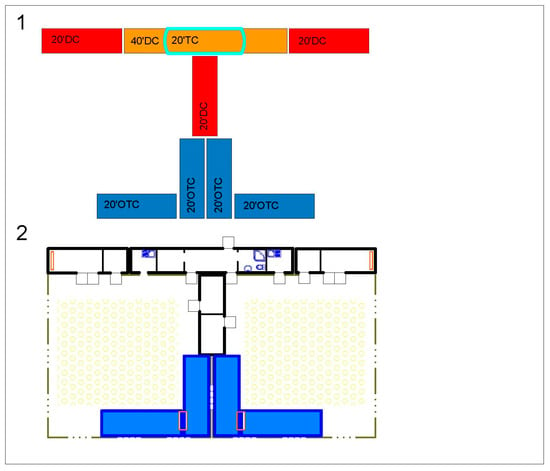

Set 20 (Figure 22): a Unit with a four-level observation deck with stairwells and an elevator. Observation deck pavilion: three observation decks with an area of 27.0 sq. m at heights of 2.8 m, 5.6 m, 8.4 m; tower blocks of 4.5 sq. m each with stairwells and an elevator. The pavilion is designed for visitors who enjoy observing the surroundings from three levels, furnished with semi-chairs. The elevator provides access to these levels for people belonging to low-mobility groups of the population. Staircases have portable intermediate platforms. A staff member on duty at the Complex is constantly present at the facility.

Figure 22.

Set 20: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Four-level observation deck (first level); 3—the plan of a Four-level observation deck (second/third/fourth levels). The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment. The asterisk indicates the vertical position of the container.

Set 21 (Figure 23): a Fish watching and a recreational fishing unit. The Pavilion for recreational fishing and fish watching: three aquariums with a glazed side surface and a surface area of 13.5 sq. m each; three water treatment tanks of 25.0 cubic m; a feed storage room of 9.0 sq. m; a filtration room of 13.5 sq. m with equipment for cleaning, a disinfection, temperature control, oxygen saturation room; a utility room of 4.5 sq. m; a storeroom of rented fishing equipment of 4.5 sq. m.; an aggregate of 9.0 sq. m.; two sloping galleries of 27.0 sq. m with stairs and ramps inside leading to the second level.

Figure 23.

Set 21: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Fish watching and recreational fishing unit (first level); 3—the plan of a Fish watching and recreational fishing unit (second level). The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.

On the second level there are two fishing pavilions of 13.5 sq. m each; an outdoor observation area of 4.5 sq. m; two fishing platforms of 3.0 sq. m each. Visitors from the ground level can spend time observing fish and crayfish through the glazed surfaces of three 20’OTC containers turned into aquariums. After renting fishing equipment (fishing rods, cages, nets, scoop-nets) and feed, visitors ascend to the second level using covered stairs and ramps adapted for low-mobility groups of the population. At this level, you can sit in pavilions, outdoor areas or platforms above the edges of aquariums, spend time having fun fishing, catching crayfish, watching them or feeding fish and crayfish. The staff present can advise the visitors.

Set 22 (Figure 24): a Sauna. The Sauna (symmetrically arranged identical complexes): a lobby of 3.5 sq. m; a linen pantry of 10.0 sq. m; a changing room of 13.5 sq. m; a bathroom of 3/0 sq. m; a vestibule of 3.0 sq. m; a shower room of 10.0 sq. m; a steam room of 10.0 sq. m; a swimming pool with a surface area of 12.5 sq. m; a toilet of 4.5 sq. m; a washing room of 36.5 sq. m, an outdoor tank with a surface area of 12.5 sq. m; a utility room of 13.5 sq. m; a clean water tank of 25.0 cubic m, an outdoor area of 36.0 sq. m. The pavilion, which is divided into men’s and women’s halves, offers bath treatments with the possibility of using indoor and outdoor pools. In the outdoor areas by the pools, it is possible to organize a short rest between treatments. There are two on-duty personnel from the Complex constantly present in each department. The simultaneous number of visitors using the services of this pavilion is 8 people in each department.

Figure 24.

Set 22: 1—The scheme and the kit; 2—the plan of a Sauna. The black lines indicate the constructions of the container; the colored lines indicate the furniture and technological equipment.