Influence of Key Paraments on the Compressive Behaviour of Concrete-Filled Multi-Cell Pultruded Square Columns Reinforced with Lattice-Webs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

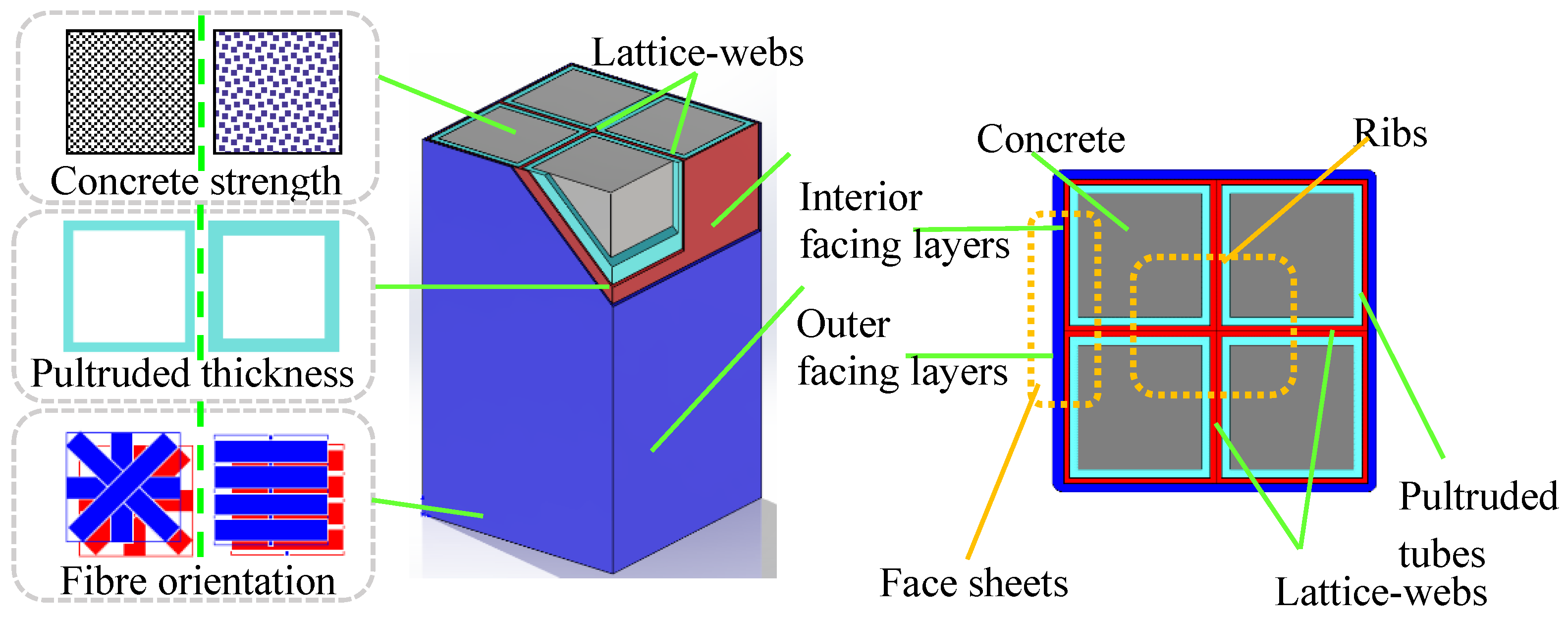

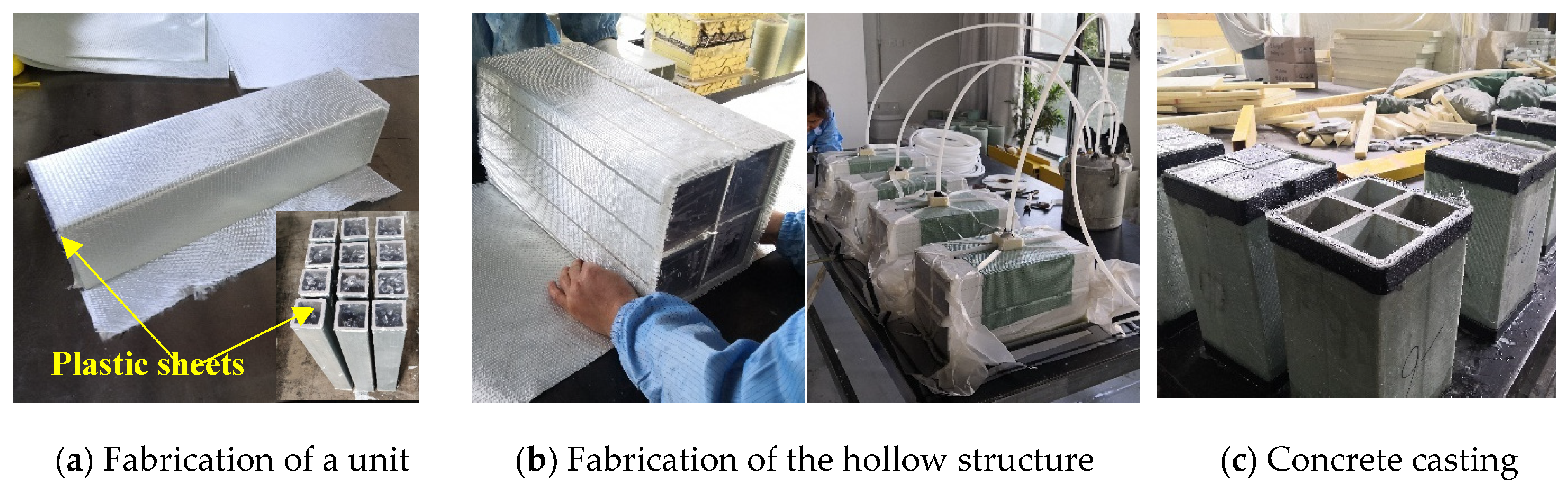

2.1. Specimens and Materials

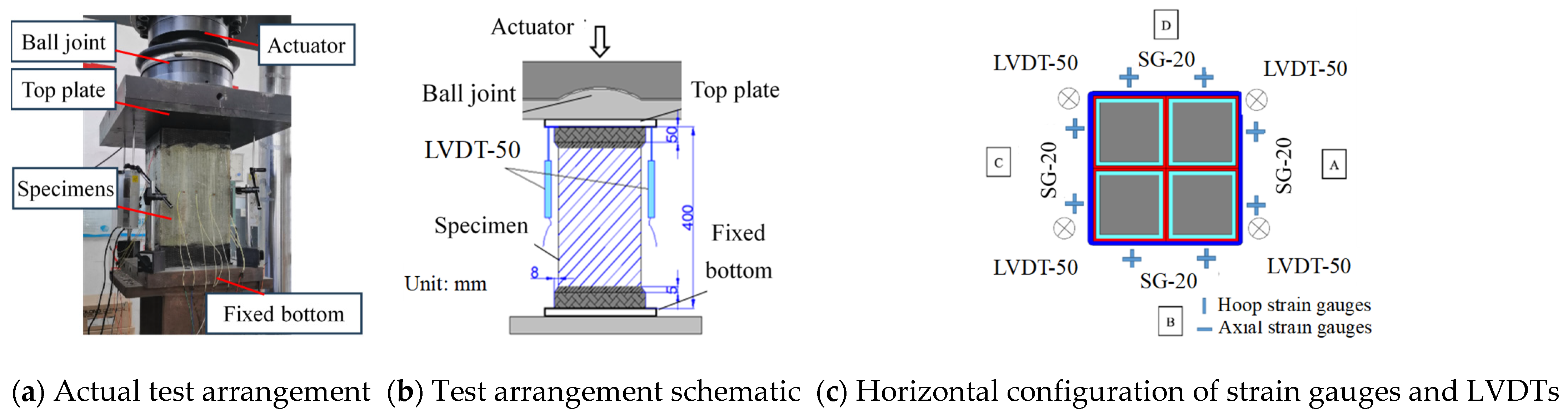

2.2. Loading Process and Instruments

3. Results and Discussion

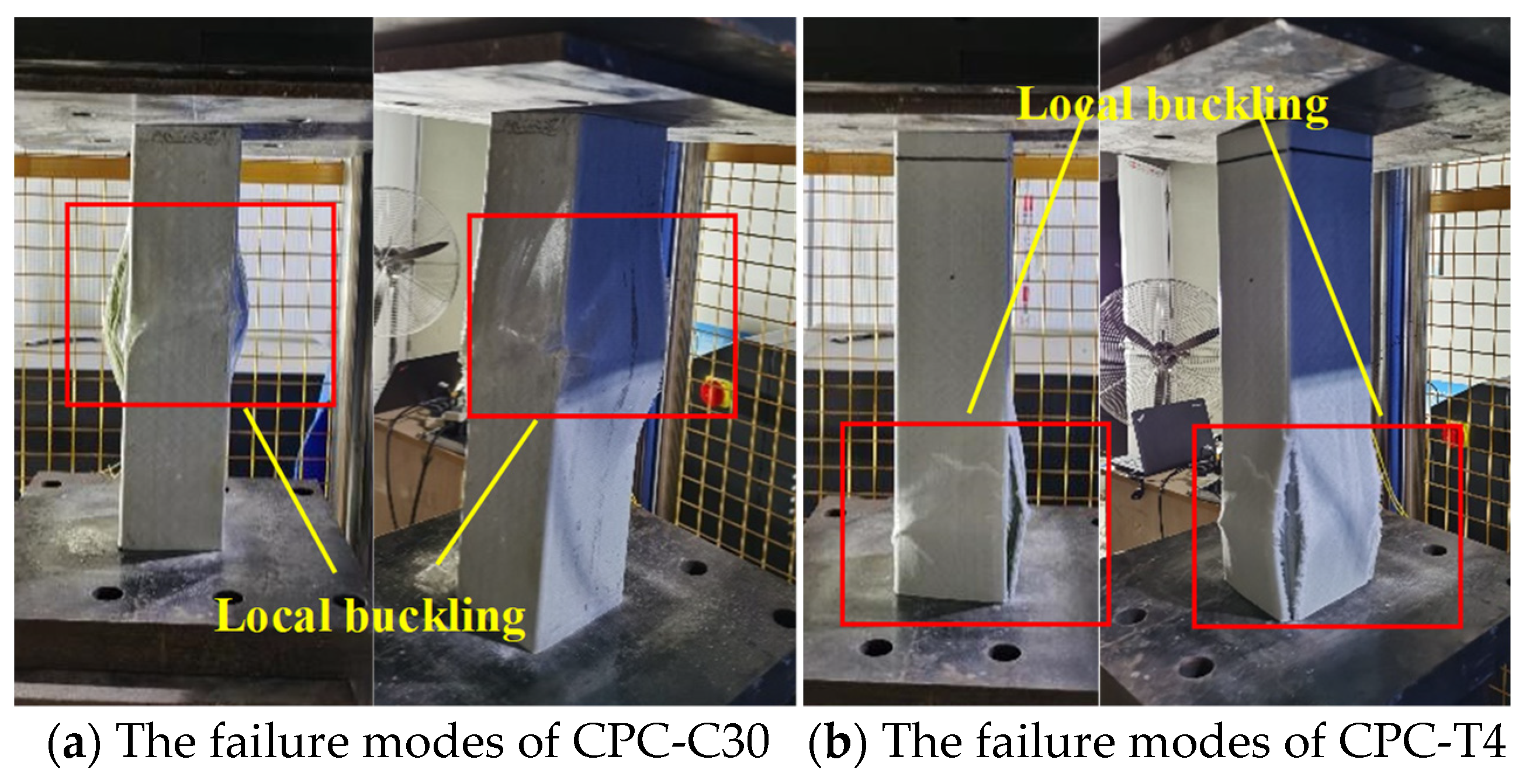

3.1. Failure Modes

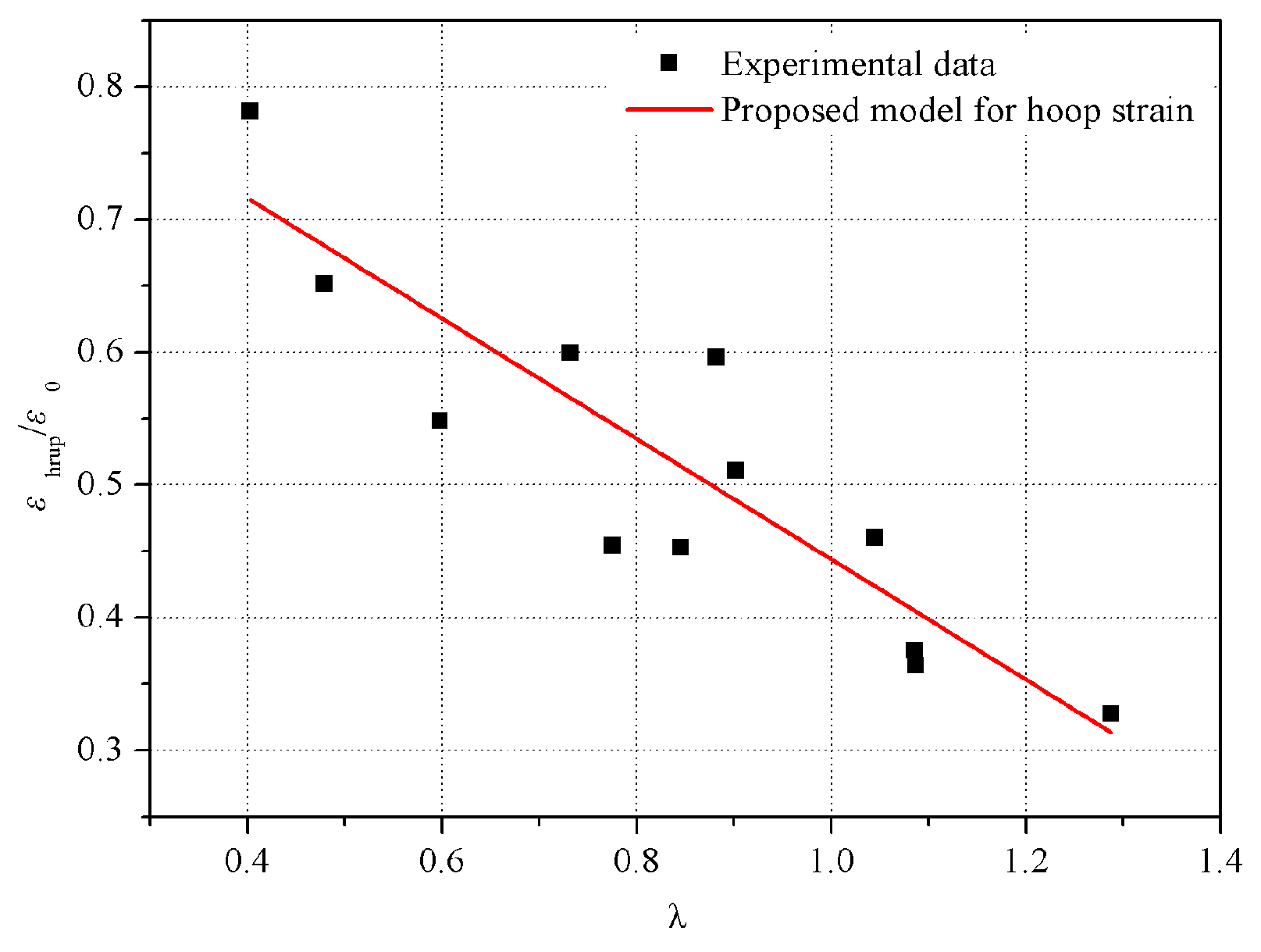

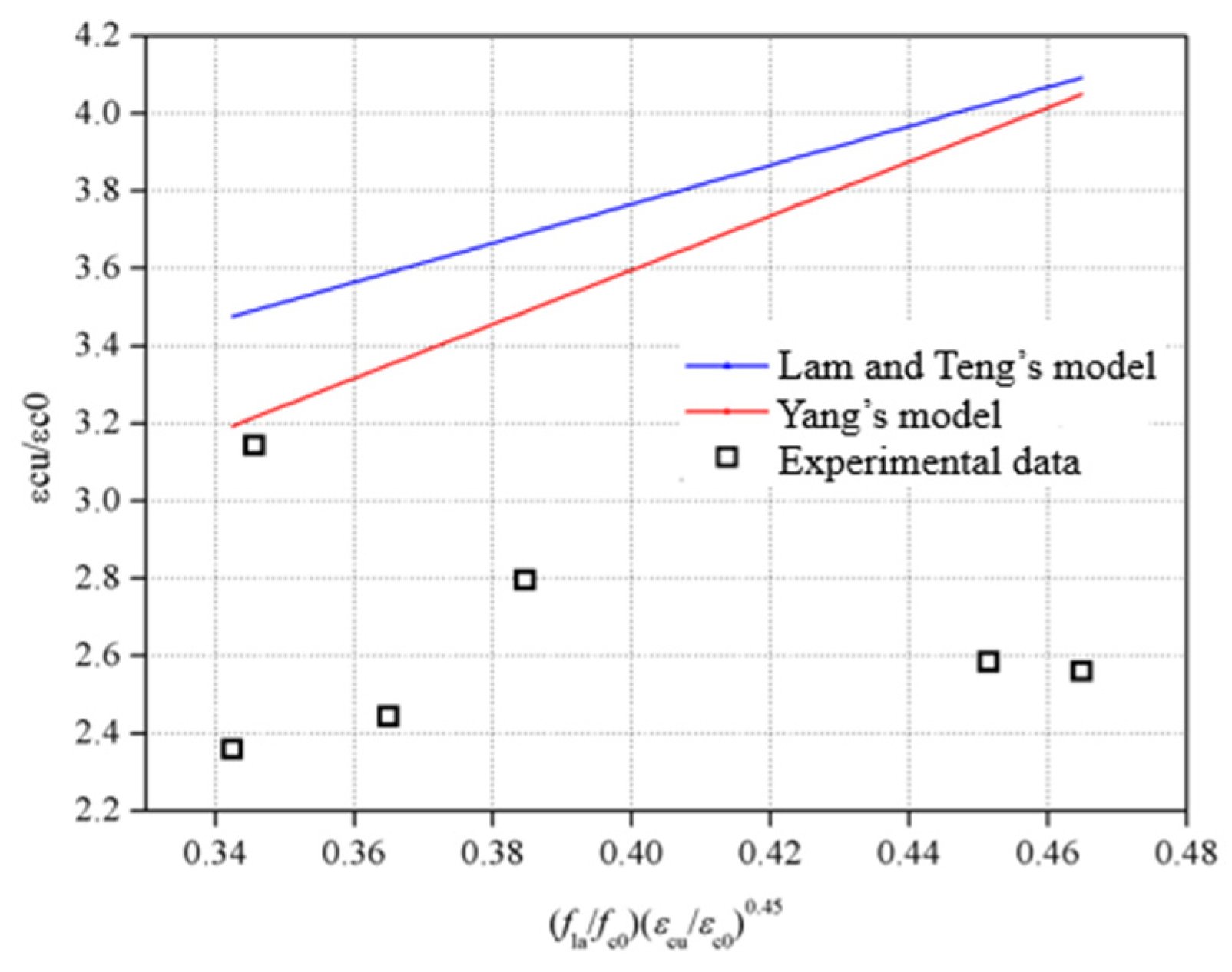

3.2. Dilation Behaviour of MCPLs

3.3. Load–Axial Strain Curves

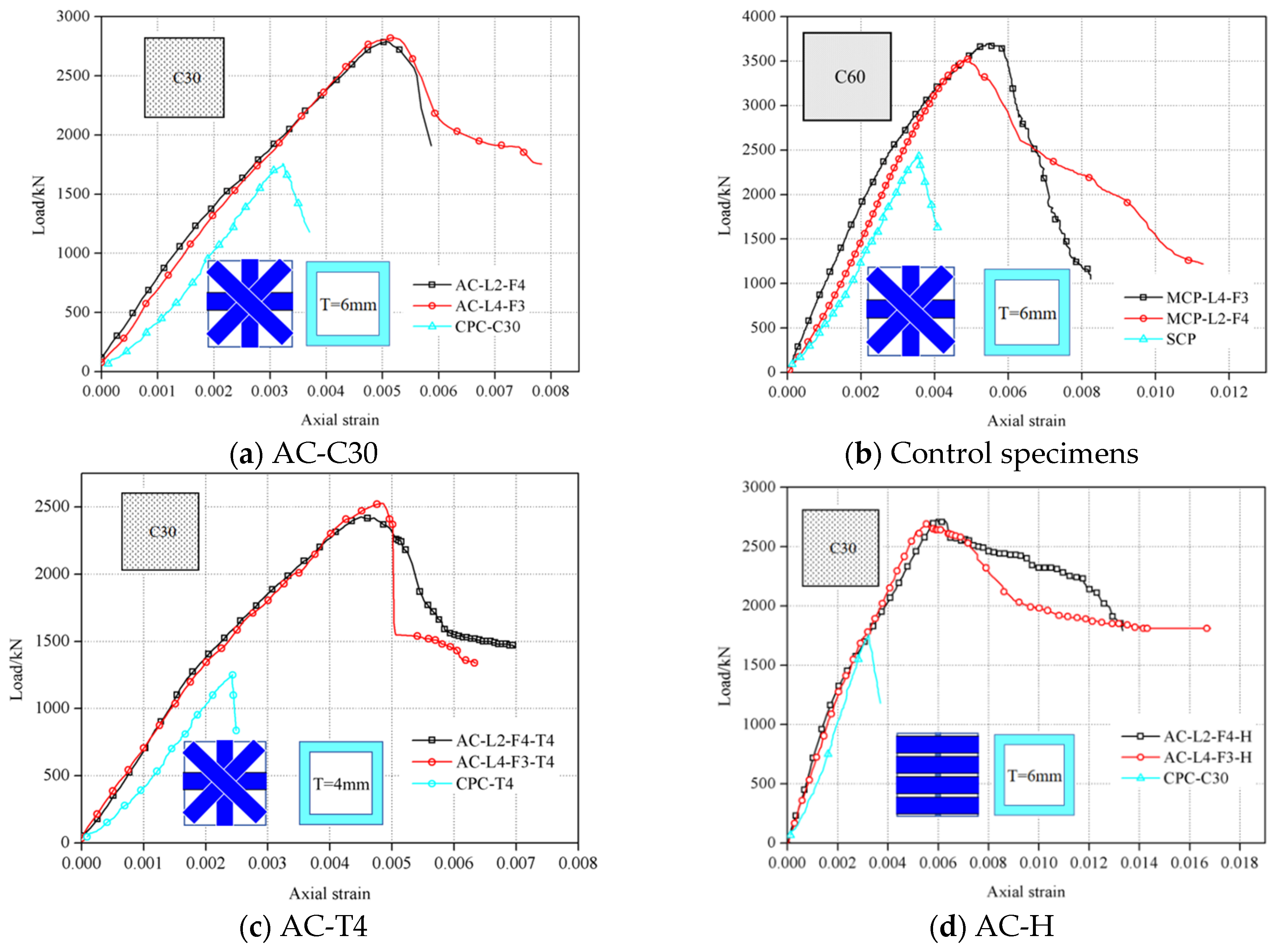

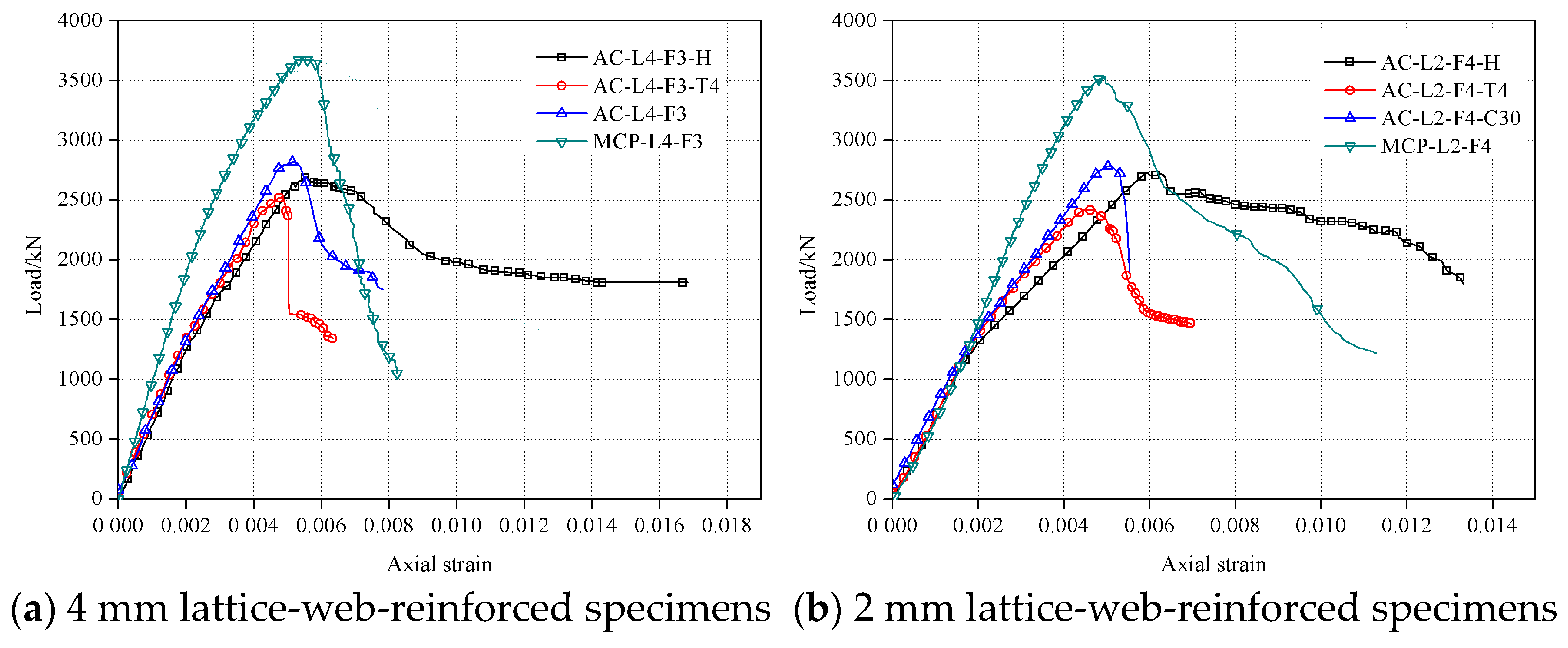

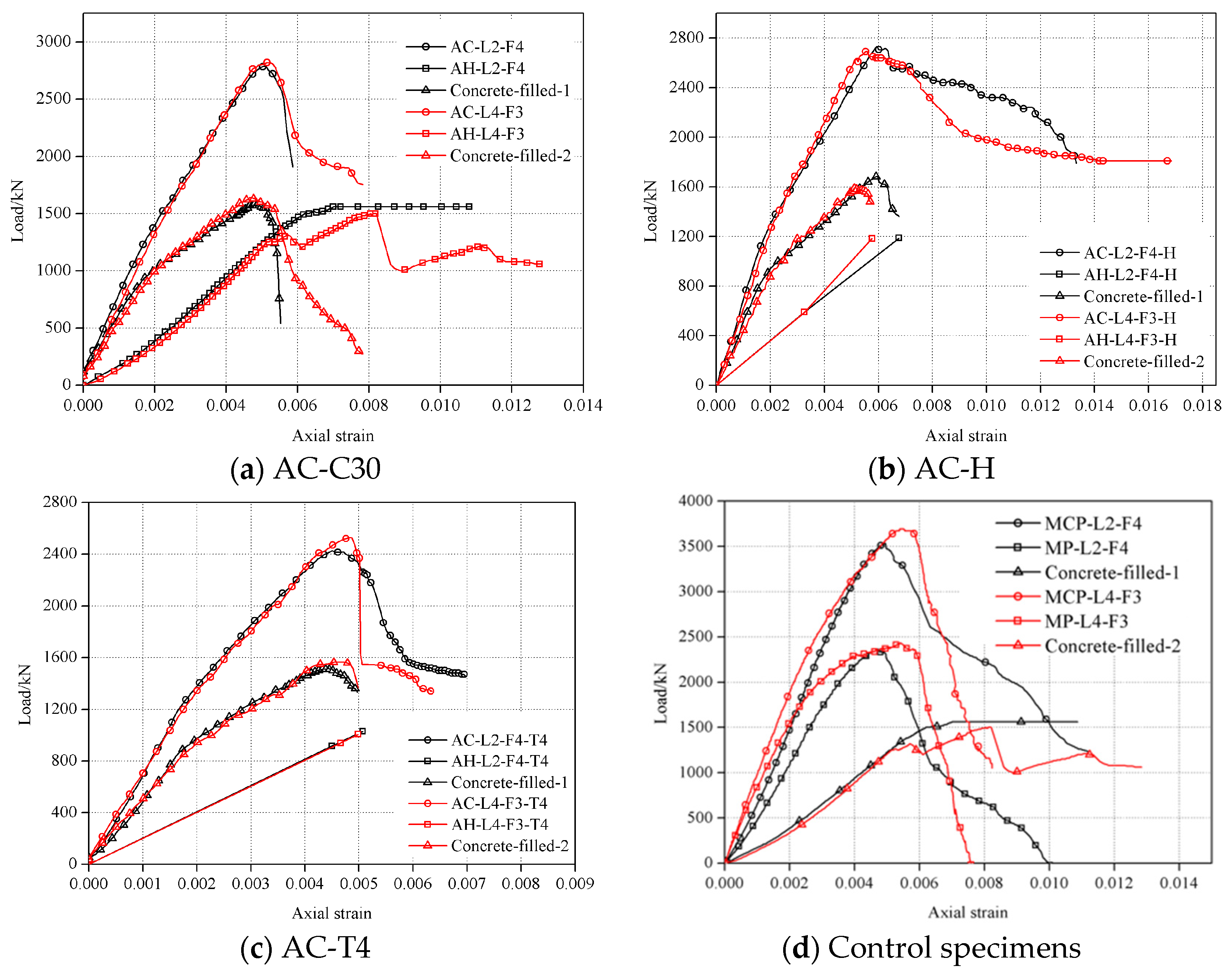

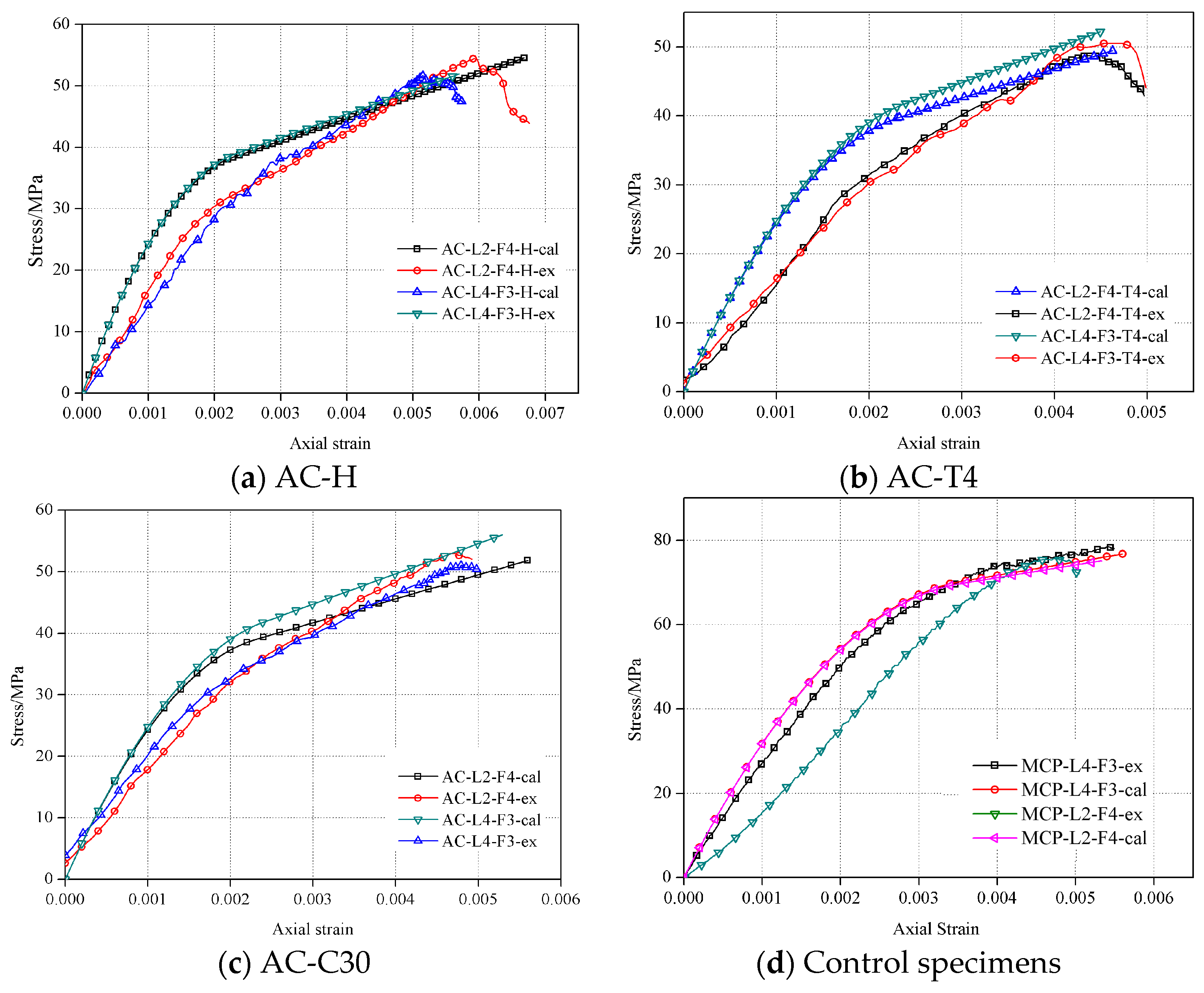

3.3.1. Influence of the Concrete Strength

3.3.2. Influence of the Pultruded Tube Thickness

3.3.3. Influence of Fibre Orientations

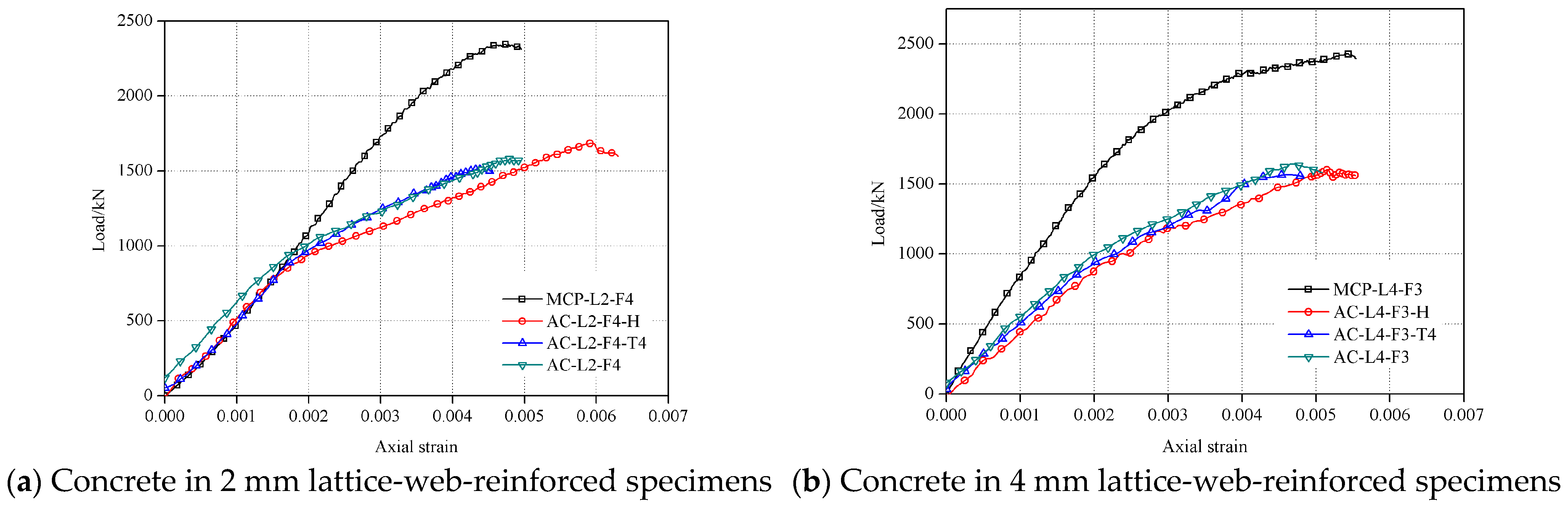

3.4. Load–Strain Responses of the Confined Concrete

4. Theoretical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vanevenhoven, L.M.; Shield, C.K.; Bank, L.C. LRFD Factors for Pultruded Wide-Flange Columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2010, 136, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Antwi, M.; De Castro, J.; Vassilopoulos, A.P.; Keller, T. Structural limits of FRP-balsa sandwich decks in bridge construction. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 63, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.N.S.; Hasan, H.A.; Sheikh, M.N. Experimental Investigation of Circular High-Strength Concrete Columns Reinforced with Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Bars and Helices under Different Loading Conditions. J. Compos. Constr. 2017, 21, 04017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Li, F.; Zhang, D.; Tao, J. Effect of Joint Stiffness on Deformation of a Novel Hybrid FRP–Aluminum Space Truss System. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Geng, P.; Yang, T. Stress and deformation of multiple winding angle hybrid filament-wound thick cylinder under axial loading and internal and external pressure. Compos. Struct. 2015, 131, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Fang, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, C.; Han, J.; Chen, C. Flexural property study of multiaxial fiber reinforced polymer sandwich panels with pultruded profile cores. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 189, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wei, X.; Fang, H.; Yang, C.; Tang, B. Shear behavior of multi-axial fiber reinforced composite sandwich structures with pultruded profile core. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Fang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S. Ship collision performance of a flexible anti-collision device designed with fiber-reinforced rubber composites. Eng. Struct. 2024, 302, 117472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, D.V. Reliability of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer-Confined Reinforced Concrete Columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.S.; Sheikh, M.N.; Hadi, M.N.S. Axial-Flexural Interactions of GFRP-CFFT Columns with and without Reinforcing GFRP Bars. J. Compos. Constr. 2017, 21, 04016109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, T.; Teng, J.G. Behavior of Concrete-Filled FRP Tubes under Cyclic Axial Compression. J. Compos. Constr. 2015, 19, 04014060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Dou, M. Axial Compression Behaviour and Modelling of Pultruded Basalt-Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (BFRP) Tubes. Buildings 2023, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Kong, W.; Guo, Z.; Xing, Z.; Chen, Y. Axial compression failure analysis of seawater sea-sand recycled aggregate concrete filled pultruded GFRP tubular column. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Influence of fiber orientation and specimen end condition on axial compressive behavior of FRP-confined concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T. Compressive behavior of concrete-filled FRP tube columns: Assessment of critical column parameters. Eng. Struct. 2013, 51, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.C.; Jiang, C.; Yu, T.; Teng, J.G. Compressive behaviour of elliptical FRP tube-confined concrete columns. Compos. Struct. 2023, 303, 116301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, R.; Abouzied, A. Flexural Performance and Deflection Prediction of Rectangular FRP-Tube Beams Fully or Partially Filled with Reinforced Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Maricherla, D.; Singh, K.; Pang, S.S.; John, M. Effect of fiber orientation on the structural behavior of FRP wrapped concrete cylinders. Compos. Struct. 2006, 74, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Lin, C.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Compressive behaviors of steel fiber-reinforced geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete-filled GFRP tube columns. Structures 2024, 66, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Fam, A. Modeling of Prestressed Concrete-Filled Circular Composite Tubes Subjected to Bending and Axial Loads. J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Novel joint for pultruded FRP beams and concrete-filled FRP columns: Conceptual and experimental investigations. Compos. Struct. 2022, 287, 115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennane, A. Filament winding processes in the manufacture of advanced fibre-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites. Adv. Fibre-Reinf. Polym. Compos. Struct. Appl. 2013, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.X.; Wang, J.Q. Experimental study on joints and flexural behavior of FRP truss-UHPC hybrid bridge. Compos. Struct. 2018, 203, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Tian, J.; Ding, Y.; Feng, P. Axial compression behavior of pultruded GFRP channel sections. Compos. Struct. 2022, 289, 115438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Z.; Fang, H.; Qi, Y.; Song, W. Bearing Capacity and Reinforced Measures of Bolted Joints for Pultruded Composite Square Tubes. Materials 2025, 18, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gribniak, V.; Ding, C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, B. The Material Heterogeneity Effect on the Local Resistance of Pultruded GFRP Columns. Mater. 2024, 17, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-saadi, A.U.; Aravinthan, T.; Lokuge, W. Effects of fibre orientation and layup on the mechanical properties of the pultruded glass fibre reinforced polymer tubes. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Bai, Y.; Qi, Y.; Caprani, C.; Wang, H. Effect of width-thickness ratio on capacity of pultruded square hollow polymer columns. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 2018, 171, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawamdeh, M.; Alajarmeh, O.; Aravinthan, T.; Shelley, T.; Schubel, P.; Mohammad, A.; Zeng, X. Modelling flexural performance of hollow pultruded FRP profiles. Compos. Struct. 2021, 276, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poodts, E.; Minak, G.; Dolcini, E.; Donati, L. FE analysis and production experience of a sandwich structure component manufactured by means of vacuum assisted resin infusion process. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 53, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Keller, T. Shear Failure of Pultruded Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites under Axial Compression. J. Compos. Constr. 2009, 13, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xia, L.; Lin, Q.; Chen, Y. Test on mechanical behavior of pultruded concrete-filled GFRP tubular short columns after elevated temperatures. Compos. Struct. 2021, 257, 113163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xue, X.; Ye, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z. Experimental research on pultruded concrete-filled GFRP tubular short columns externally strengthened with CFRP. Compos. Struct. 2021, 255, 112943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.M.; Wu, Y.F. Effect of corner radius on the performance of CFRP-confined square concrete columns: Test. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Gao, Y.; Fang, J.; Feng, Z.; Sun, G.; Li, Q. Crashworthiness analysis and design of multi-cell hexagonal columns under multiple loading cases. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2015, 104, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Oehlers, D.J. Manufacture and testing of a novel FRP tube confinement system. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 2448–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.S. FRP-Confined concrete-encased cross-shaped steel columns: Effects of key parameters. Compos. Struct. 2021, 272, 114252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.S.; Wang, Z.Y. FRP-confined concrete-encased cross-shaped steel columns: Concept and behaviour. Eng. Struct. 2017, 152, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fang, H.; Xie, H.; Li, B. Compressive behaviour of concrete-filled multi-cell GFRP pultruded square columns reinforced with lattice-webs. Eng. Struct. 2023, 279, 115584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Fang, H.; Liu, W.; Hong, J.; Hui, D.; Gaff, M. Compressive behaviour of wood-filled GFRP square columns with lattice-web reinforcements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 310, 125129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Fang, H.; Bai, Y.; Hui, D. Flexural responses and pseudo-ductile performance of lattice-web reinforced GFRP-wood sandwich beams. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 108, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Shen, Z.; He, W. Lateral compressive behavior of multi-layer lattice-web reinforced composite cylinders. Eng. Struct. 2024, 306, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Teng, J.G. Design-oriented stress-strain model for FRP-confined concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttashar, M.; Manalo, A.; Karunasena, W.; Lokuge, W. Influence of infill concrete strength on the flexural behaviour of pultruded GFRP square beams. Compos. Struct. 2016, 145, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Test on residual ultimate strength of pultruded concrete-filled GFRP tubular short columns after lateral impact. Compos. Struct. 2021, 260, 113520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D 3039/D 3039M–14; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM:D5379; Standard Test Method for Shear Properties of Composite Materials by the V-Notched Beam Method. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM D695; Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Rigid Plastics. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Khalilabad, E.H.; Emparanza, A.R.; De Caso, F.; Roghani, H.; Khodadadi, N.; Nanni, A. Characterization Specifications for FRP Pultruded Materials: From Constituents to Pultruded Profiles. Fibers 2023, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, A.; Flisak, B.; Rizkalla, S. Experimental and analytical modeling of concrete-filled fiber-reinforced polymer tubes subjected to combined bending and axial loads. ACI Struct. J. 2003, 100, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Fang, H.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Hui, D. Compressive behaviour of multi-cell GFRP pultruded square columns reinforced with lattice-webs. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 184, 110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovics, S. A numerical approach to the complete stress-strain curveof concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1973, 3, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Label | Dimension (mm) | Interior Facing Layers | Outer Facing Layers | Concrete | Section Configuration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | L | r | T | ||||||

| CPC | CPC-C30 | 400 | 100 | 3 | 6 | C30 |  | ||

| CPC-T4 | 400 | 100 | 3 | 4 | - | - | C30 | ||

| Control Specimens | SCP | 400 | 100 | 3 | 6 | - | - | C30 | |

| MCP-L2-F4 | 400 | 210 | 3 | 6 | (±45°)2 | [(0, 90°)2/(±45°)]2 | C60 |  | |

| MCP-L4-F3 | 400 | 210 | 3 | [(±45°)2/(0°/90°)2] | (±45°)2 | C60 | |||

| AC-C30 | AC-L2-F4-C30 | 400 | 210 | 3 | (±45°)2 | [(0, 90°)2/(±45°)]2 | C30 |  | |

| AC-L4-F3-C30 | 400 | 210 | 3 | [(±45°)2/(0°/90°)2] | (±45°)2 | C30 | |||

| AC-H | AC-L2-F4-H | 400 | 210 | 3 | (0)2 | (0)6 | C30 | ||

| AC-L4-F3-H | 400 | 210 | 3 | (0)4 | (0)2 | C30 | |||

| AC-T4 | AC-L2-F4-T4 | 400 | 210 | 3 | 4 | (±45°)2 | [(0, 90°)2/(±45°)]2 | C30 | |

| AC-L4-F3-T4 | 400 | 210 | 3 | [(±45°)2/(0°/90°)2] | (±45°)2 | C30 | |||

| Properties | (0°) | Concrete C30 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

| Axial compression | Strength (MPa) | 9.88 | 1.02 | 31.86 | 1.13 |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 3.15 | 0.63 | 31.15 | 0.81 | |

| Transverse compression | Strength (MPa) | 181.22 | 8.26 | - | - |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 26.16 | 4.63 | - | - | |

| Axial tensile strength (MPa) | 50.41 | 2.94 | - | - | |

| Transverse tensile strength (MPa) | 330.51 | 11.63 | - | - | |

| Shear modulus (GPa) | 6.51 | 0.83 | - | - | |

| Poisson’s ratio | υ12 | 0.03 | 0.20 | ||

| υ21 | 0.30 | 0.20 | |||

| Label | σc (MPa) | Ψ (%) | Favp (kN) | εavp (10−6) | Favu (kN) | εavu (10−6) | Favy (kN) | εavy (10−6) | μ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCP | 60.11 | 0.1812 | 609.7 | 3564 | 518.3 | 3773 | 582.5 | 3431 | 1.091 |

| CPC-C30 | 28.53 | −4.900 | 437.53 | 3156 | 371.9 | 3358 | 415.65 | 3137 | 1.070 |

| CPC-T4 | 29.53 | −1.567 | 308.9 | 2415 | 266.5 | 2366 | 298.3 | 2299 | 1.020 |

| AC-L2-F4-C30 | 48.96 | 63.20 | 2790 | 5121 | 2371 | 5654 | 2728 | 4778 | 1.183 |

| AC-L4-F3-C30 | 52.94 | 76.47 | 2824 | 5168 | 2400 | 5773 | 2623 | 4455 | 1.296 |

| MCP-L2-F4 | 77.29 | 29.83 | 3485 | 4983 | 2962 | 5721 | 3350 | 4297 | 1.331 |

| MCP-L4-F3 | 80.16 | 34.65 | 3682 | 5692 | 3130 | 6978 | 2973 | 3662 | 1.906 |

| AC-L2-F4-H | 54.35 | 81.17 | 2723 | 6043 | 2315 | 10,681 | 2599 | 5543 | 1.926 |

| AC-L4-F3-H | 51.52 | 71.73 | 2696 | 5515 | 2289 | 8128 | 2635 | 5265 | 1.543 |

| AC-L2-F4-T4 | 48.74 | 62.47 | 2426 | 4544 | 2092 | 5358 | 2285 | 4192 | 1.278 |

| AC-L4-F3-T4 | 50.58 | 68.60 | 2529 | 4825 | 2272 | 5020 | 2091 | 3786 | 1.326 |

| Label | ε(w=1) x (10−6) | F(w=1) (kN) | ε(w=2) x (10−6) | F(w=2) (kN) | ε(w=3) x (10−6) | F(w=3) (kN) | ε(w=4) x (10−6) | F(w=4) (kN) | Fpcr (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH-L2-F4-H | 3250 | 590 | 3254 | 592 | 6760 | 1188 | 1487 | ||

| AH-L4-F3-H | 3254 | 589.65 | 3257 | 589.90 | 5760 | 1184 | - | - | 1522 |

| AH-L2-F4-T4 | 5069 | 1029 | 5214 | 1056 | 6713 | 1228 | 6803 | 1237 | 493.38 |

| AH-L4-F3-T4 | 4987 | 1007 | 5436 | 1071 | 5991 | 1119 | - | - | 501.47 |

| Label | E2 (MPa) | εt | εh0 | εh,rup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC-L2-F4-T4 | 4941.23 | 0.0023944 | 0.008812 | 0.004810 |

| AC-L4-F3-T4 | 4207.58 | 0.0023263 | 0.007800 | 0.005305 |

| AC-L2-F4-H | 3679.54 | 0.0022796 | 0.009842 | 0.003987 |

| AC-L4-F3-H | 3856.58 | 0.0022950 | 0.009229 | 0.004367 |

| AC-L2-F4-C30 | 4911.88 | 0.0023916 | 0.007982 | 0.004998 |

| AC-L4-F3-C30 | 3898.61 | 0.0022987 | 0.007182 | 0.005133 |

| MCP-L2-F4 | 3247.09 | 0.0035464 | 0.007982 | 0.003320 |

| MCP-L4-F3 | 3084.61 | 0.0035292 | 0.007182 | 0.004060 |

| Label | Actual Hoop Rupture Strain (10−6) | Ultimate Axial Strain (10−6) | Ultimate Stress of Concrete (MPa) | Peak Loads of MCPLs (kN) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| εca | εex | (εca − εex)/εex | εca | εex | (εca − εex)/εex | σca | σex | (σca − σex)/σex | Pca | Pex | (Fca − Fex)/Fex | |

| AC-L2-F4-T4 | 4810 | 4035 | 19.2% | 4509 | 4718 | 4.43% | 52.28 | 48.74 | −7.26% | 2648 | 2426 | −9.17% |

| AC-L4-F3-T4 | 5305 | 5082 | 4.39% | 4644 | 4886 | 4.95% | 49.54 | 50.58 | 2.06% | 2541 | 2529 | −0.500% |

| AC-L2-F4-H | 3987 | 3689 | 8.08% | 6759 | 6287 | −7.51% | 54.87 | 54.35 | −0.960% | 2887 | 2723 | −6.05% |

| AC-L4-F3-H | 4367 | 4177 | 4.55% | 5759 | 5592 | −2.99% | 52.21 | 51.52 | −1.34% | 2801 | 2696 | −3.90% |

| AC-L2-F4-C30 | 4998 | 4580 | 9.13% | 5334 | 5121 | −4.16% | 56.20 | 48.96 | −14.8% | 3145 | 2790 | −12.7% |

| AC-L4-F3-C30 | 5133 | 5612 | −8.54% | 5602 | 5168 | −8.40% | 51.84 | 52.94 | 2.08% | 3016 | 2824 | −6.79% |

| MCP-L2-F4 | 3320 | 2988 | 11.1% | 5334 | 4983 | −7.04% | 76.32 | 77.29 | 0.0900% | 3768 | 3485 | −8.12% |

| MCP-L4-F3 | 4060 | 4304 | −5.67% | 5602 | 5692 | 1.58% | 76.28 | 80.16 | −4.26% | 3773 | 3682 | −2.47% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Fang, H.; Song, Y.; Xie, H.; Chen, C. Influence of Key Paraments on the Compressive Behaviour of Concrete-Filled Multi-Cell Pultruded Square Columns Reinforced with Lattice-Webs. Buildings 2025, 15, 4352. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234352

Yang L, Wang S, Fang H, Song Y, Xie H, Chen C. Influence of Key Paraments on the Compressive Behaviour of Concrete-Filled Multi-Cell Pultruded Square Columns Reinforced with Lattice-Webs. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4352. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234352

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Laiyun, Shiao Wang, Hai Fang, Yongsheng Song, Honglei Xie, and Chen Chen. 2025. "Influence of Key Paraments on the Compressive Behaviour of Concrete-Filled Multi-Cell Pultruded Square Columns Reinforced with Lattice-Webs" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4352. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234352

APA StyleYang, L., Wang, S., Fang, H., Song, Y., Xie, H., & Chen, C. (2025). Influence of Key Paraments on the Compressive Behaviour of Concrete-Filled Multi-Cell Pultruded Square Columns Reinforced with Lattice-Webs. Buildings, 15(23), 4352. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234352