Seismic Damage Assessment of Minarets: Insights from the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, Türkiye

Abstract

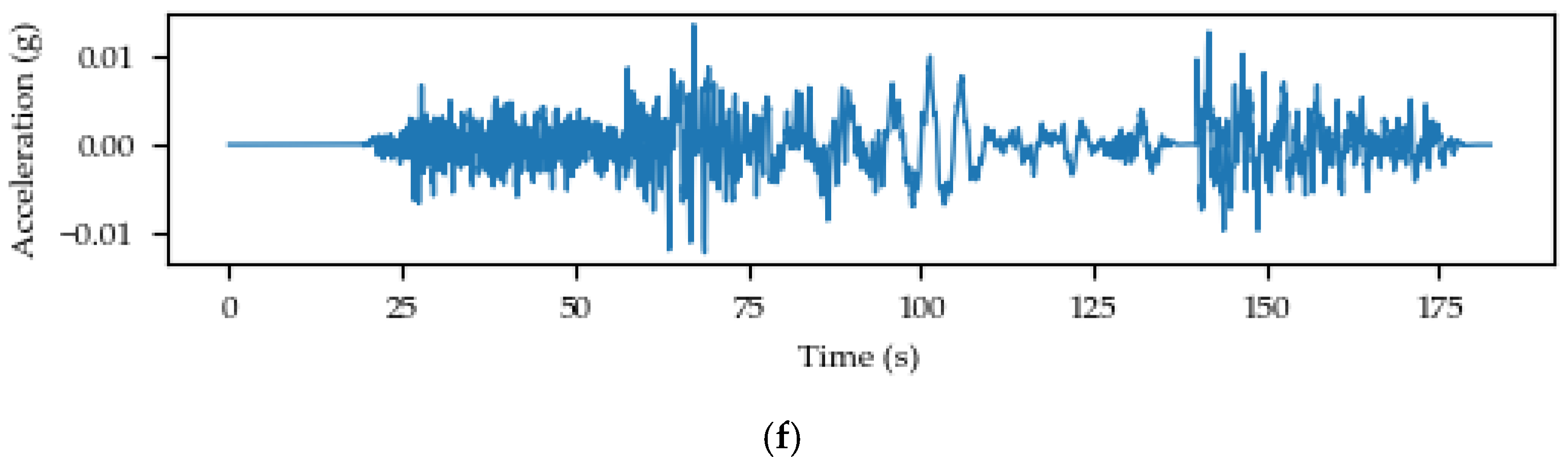

1. Introduction

2. Effects of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş (Türkiye) Earthquakes on Minarets

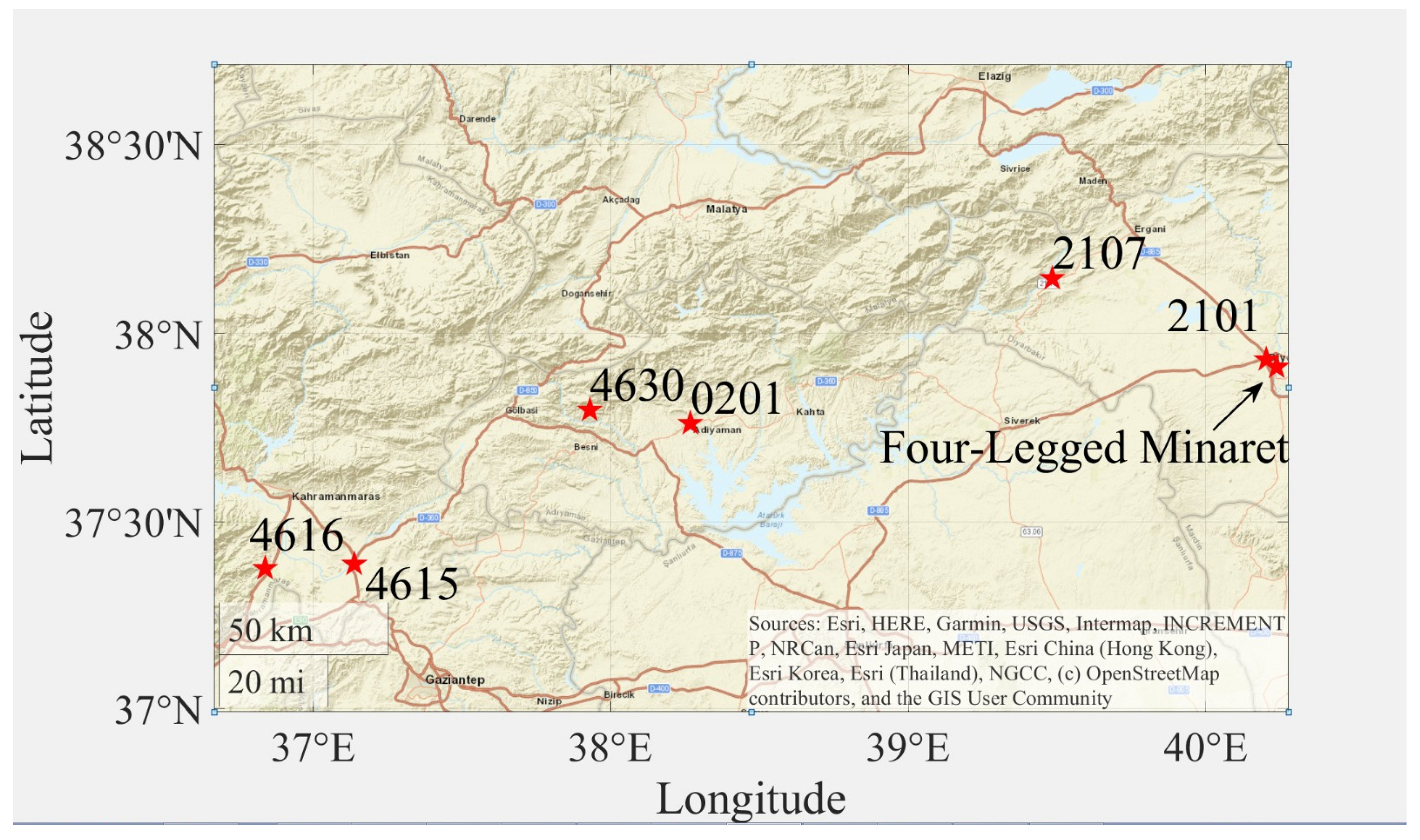

3. Numerical Modeling of the Selected Minaret

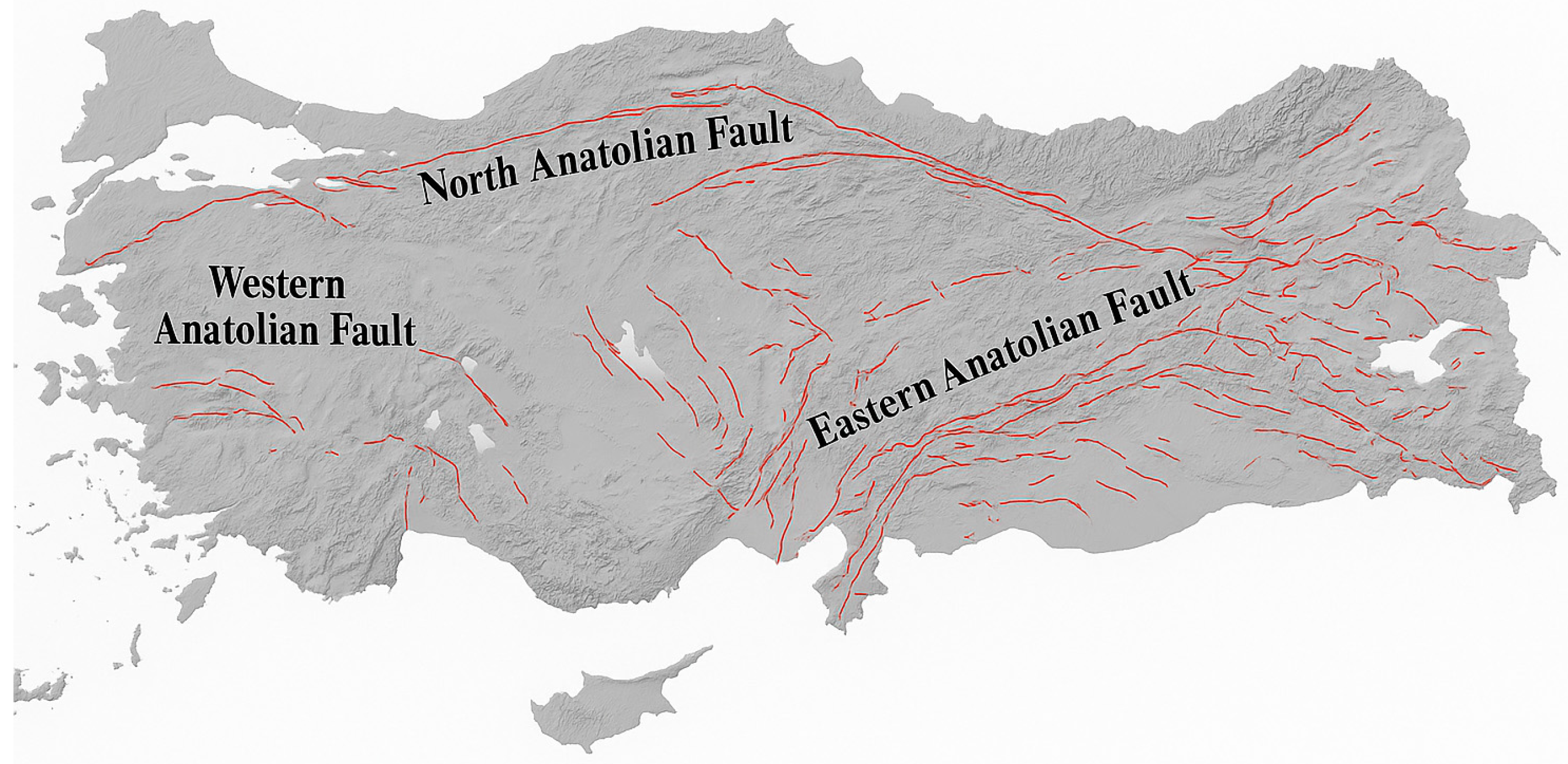

3.1. Case Study: The Four-Legged Minaret

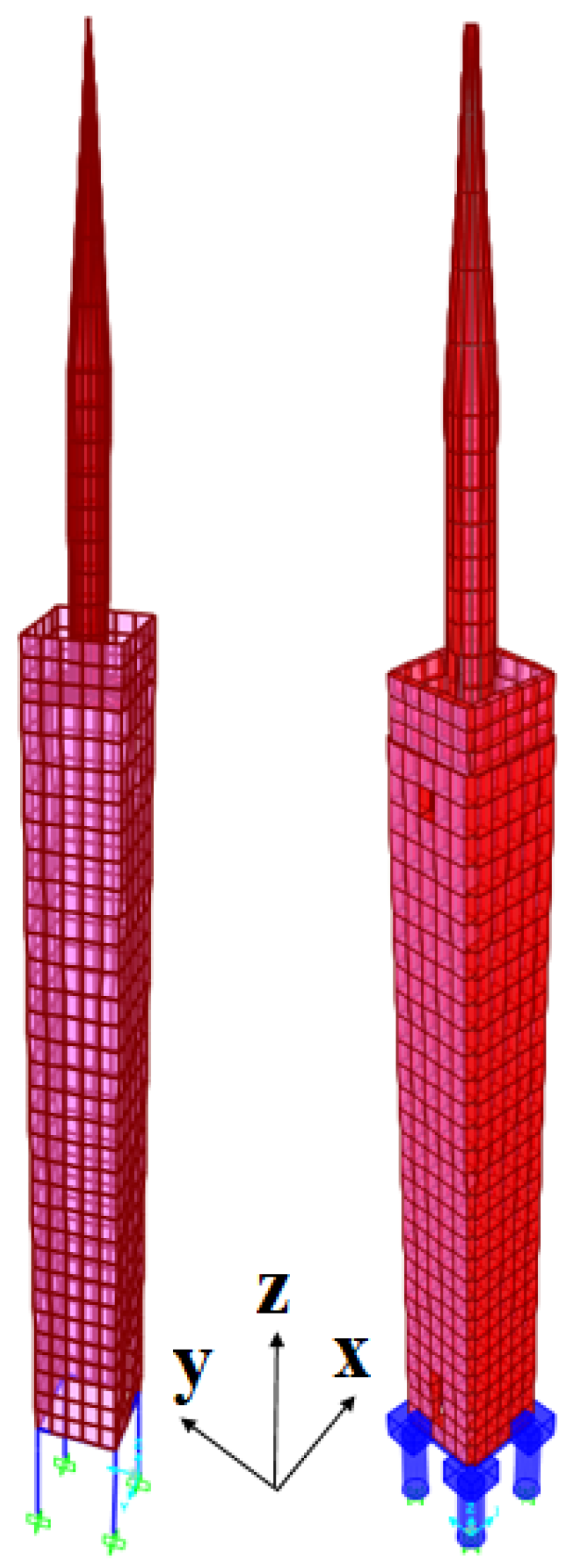

3.2. Finite Element Modeling of the Minaret

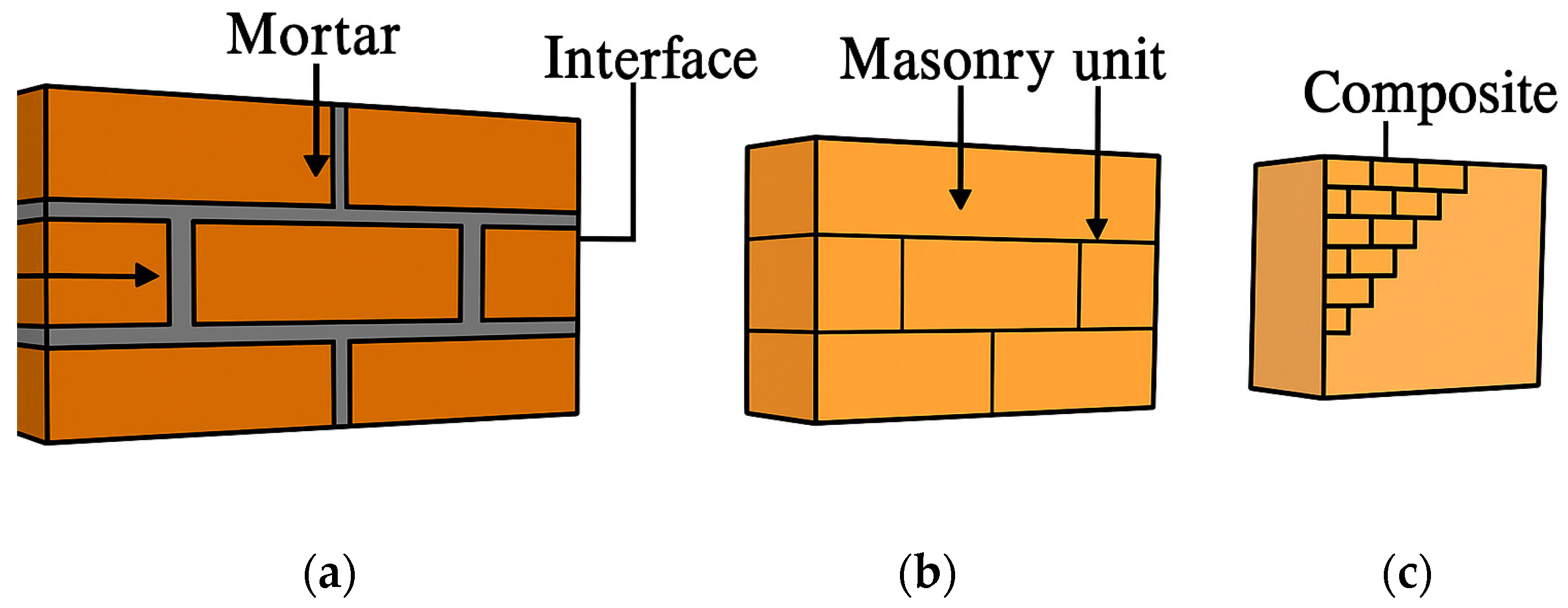

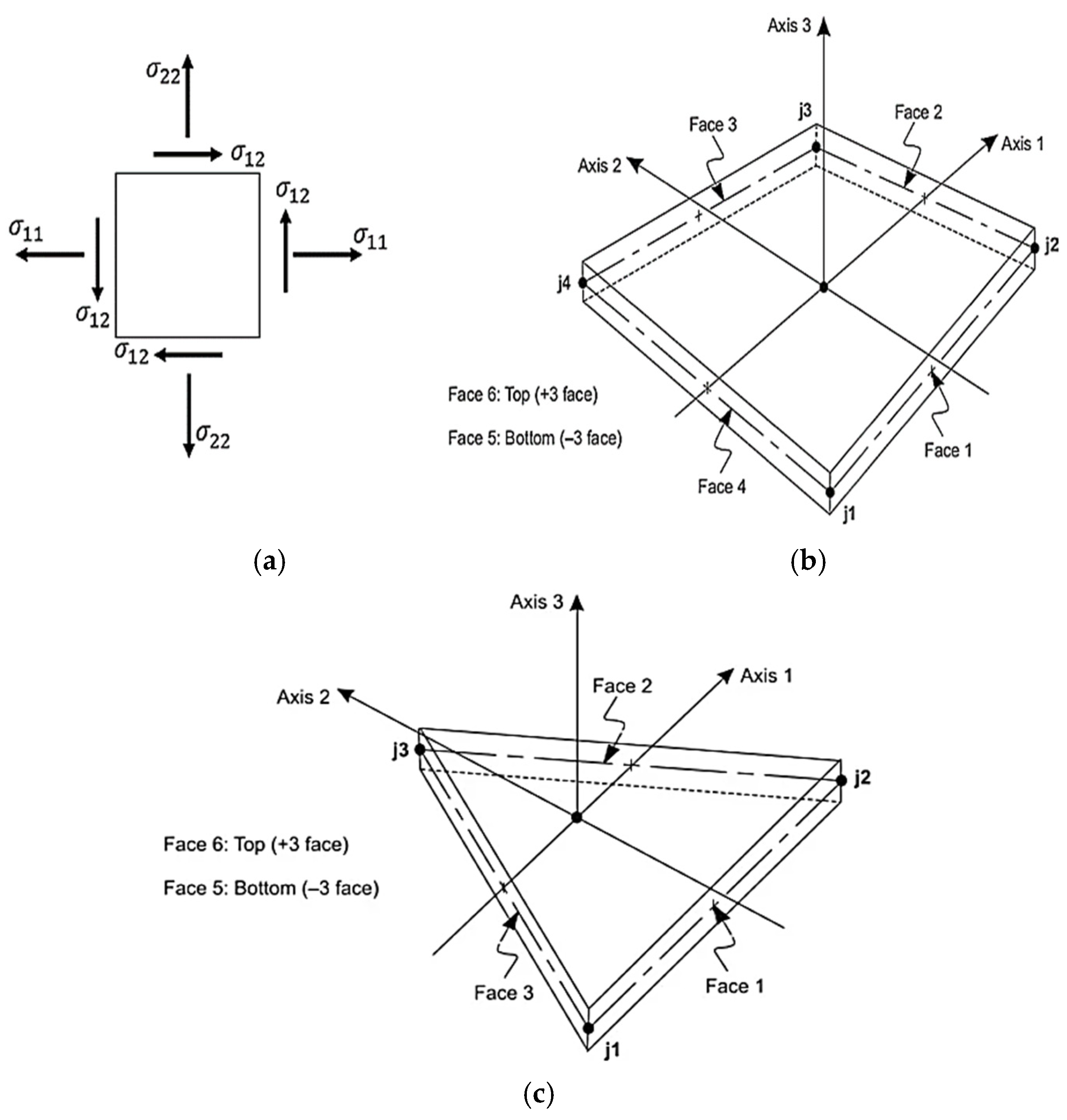

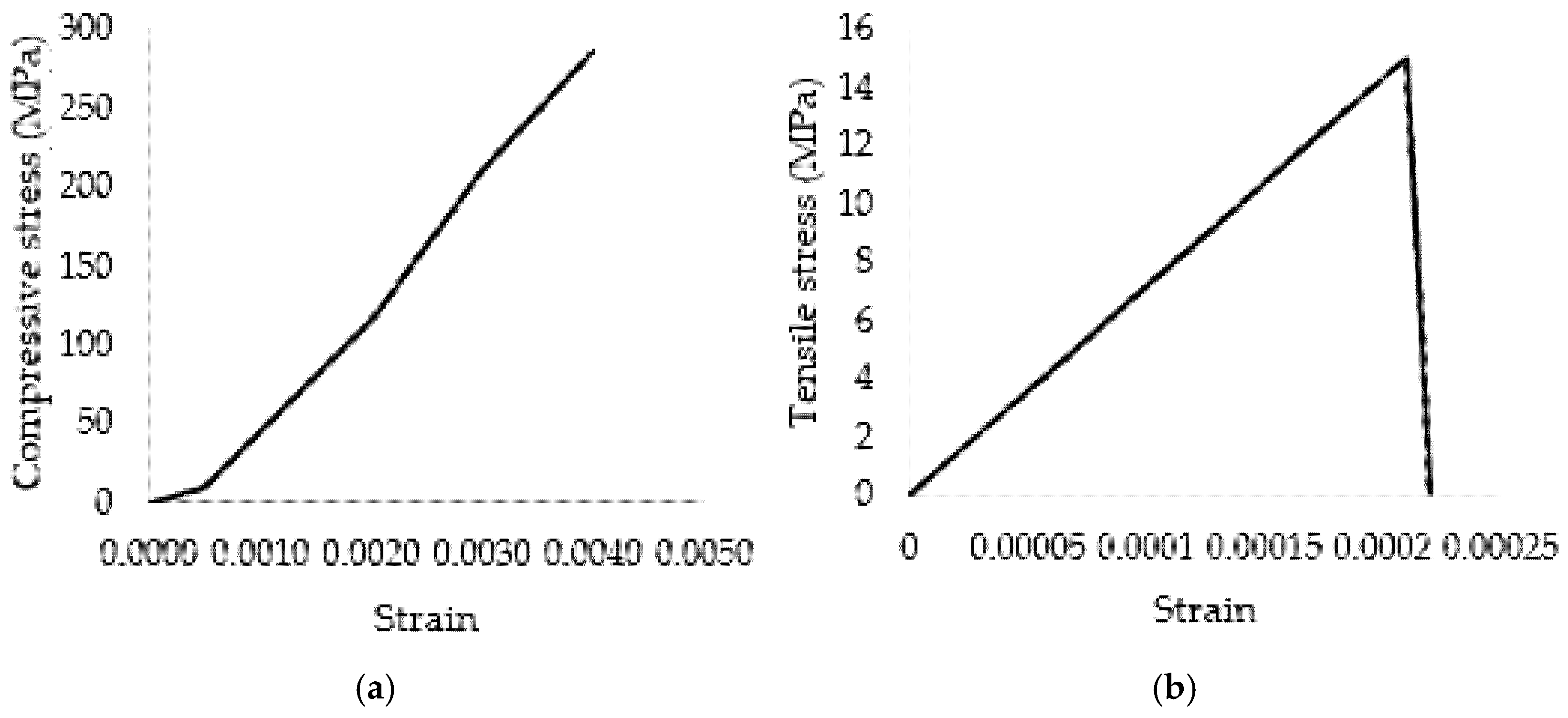

3.2.1. Material Properties

| Material | Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Unit Weight (kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basalt stone | 71,400 | 0.15 | 25 |

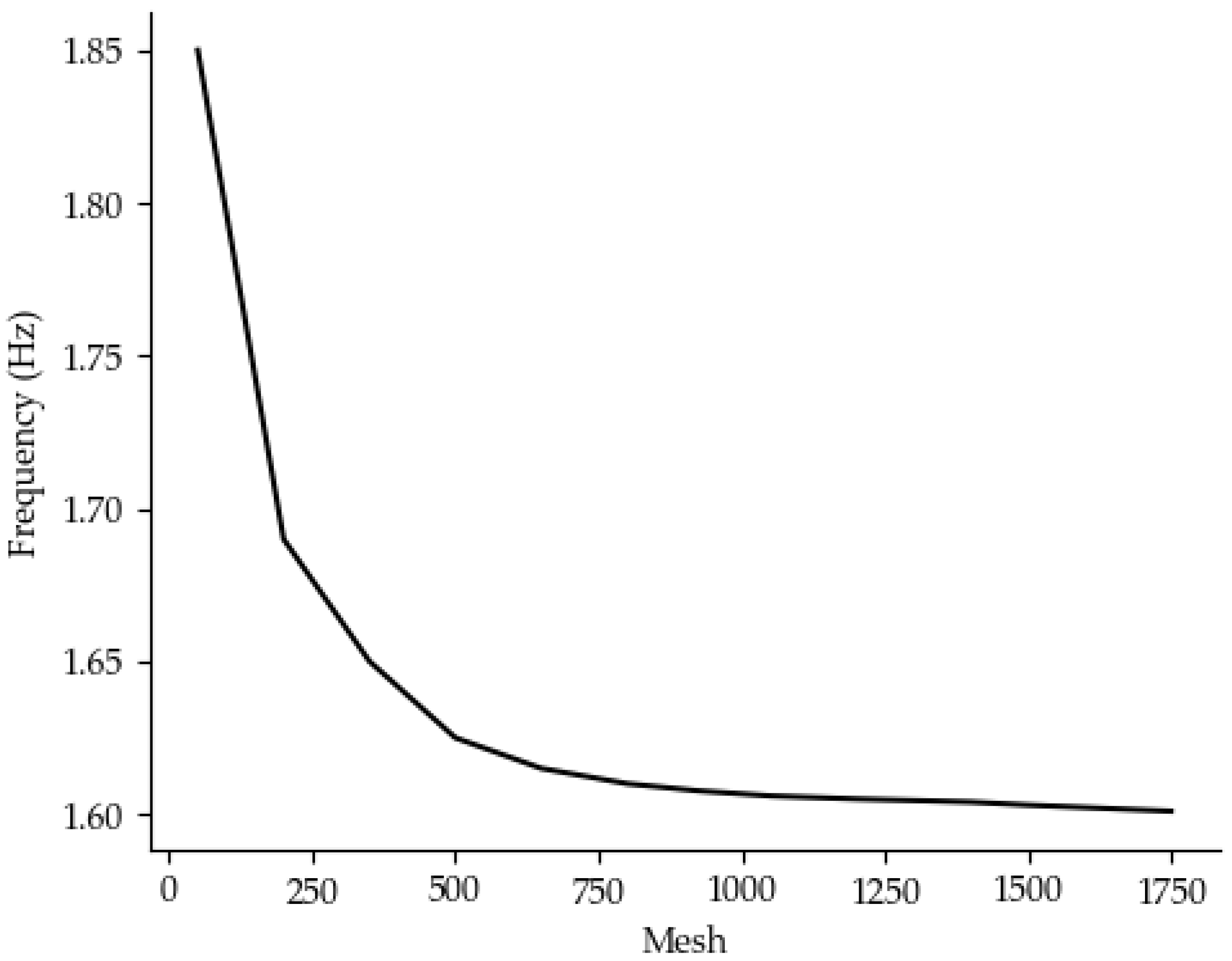

3.2.2. Finite Element Meshing

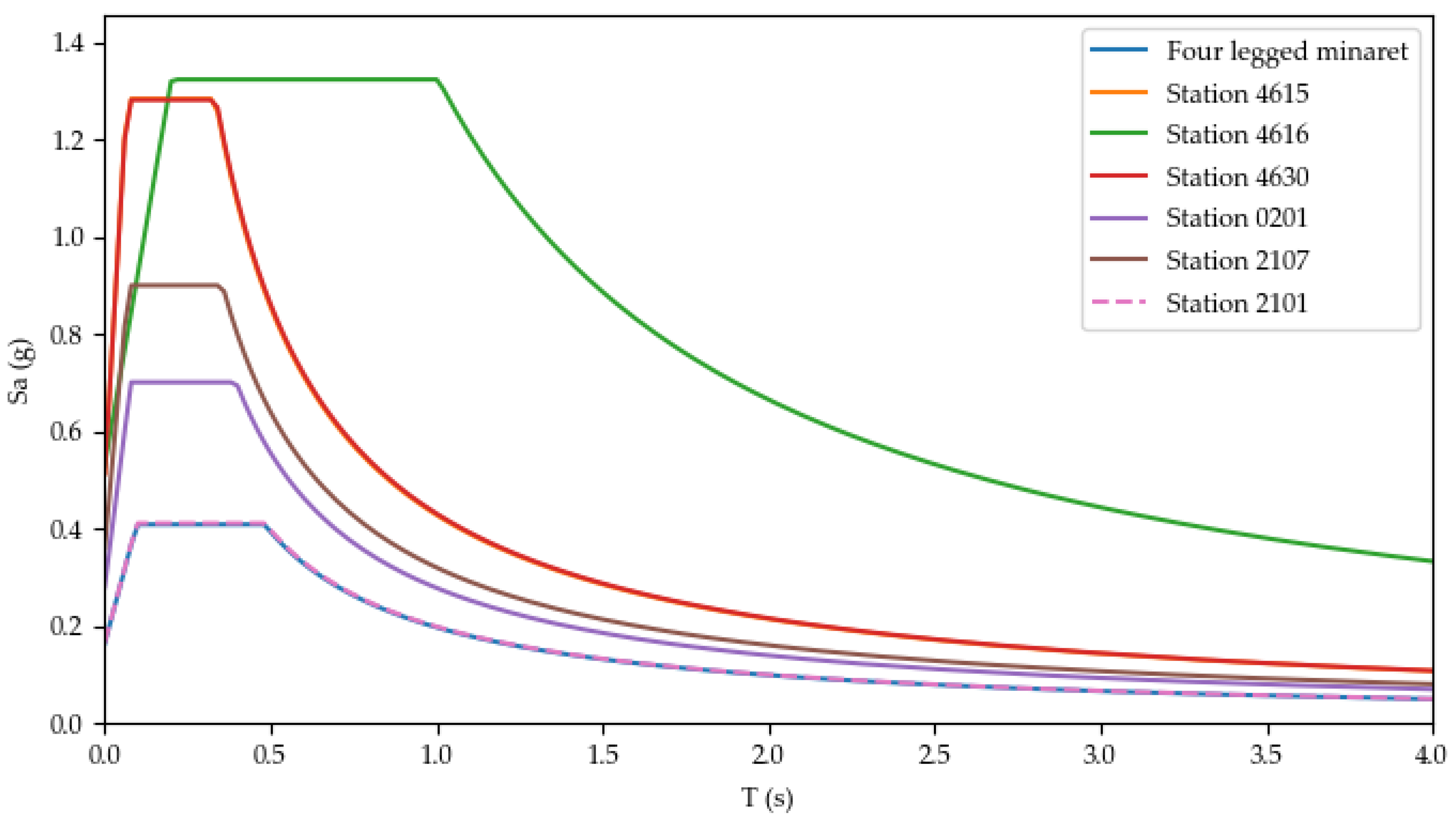

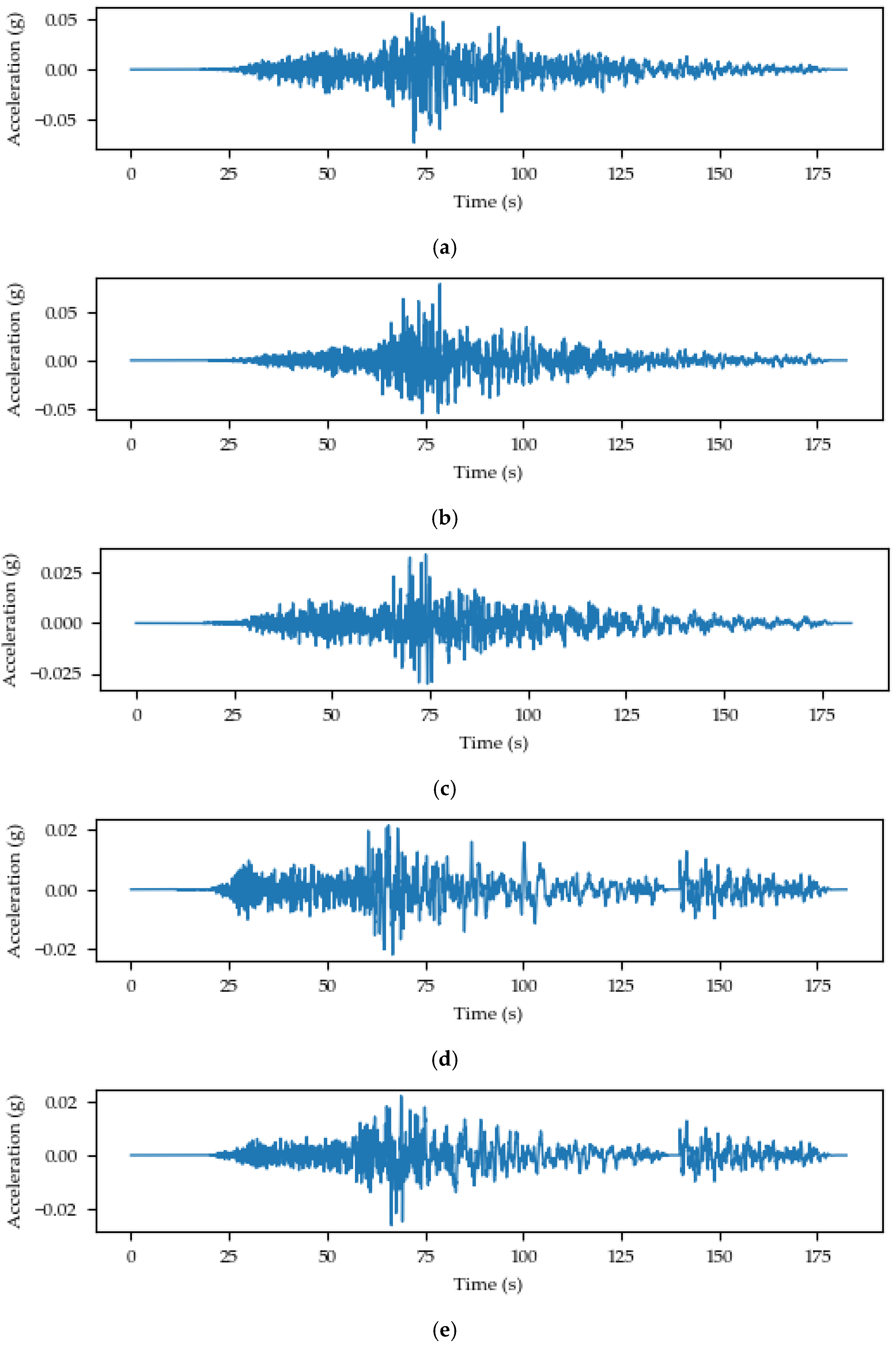

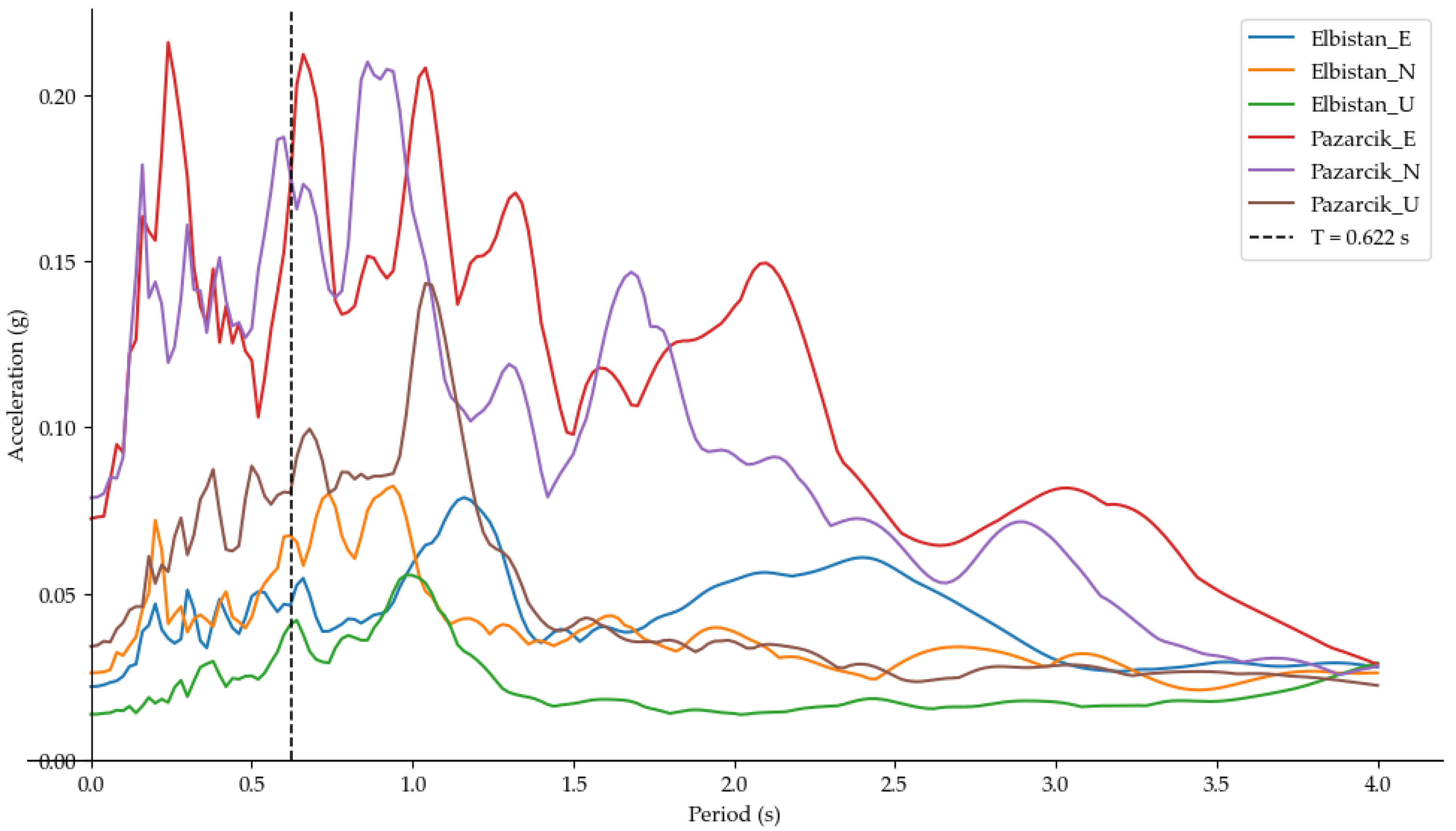

4. Input Ground Motion Dataset

5. Results and Discussion

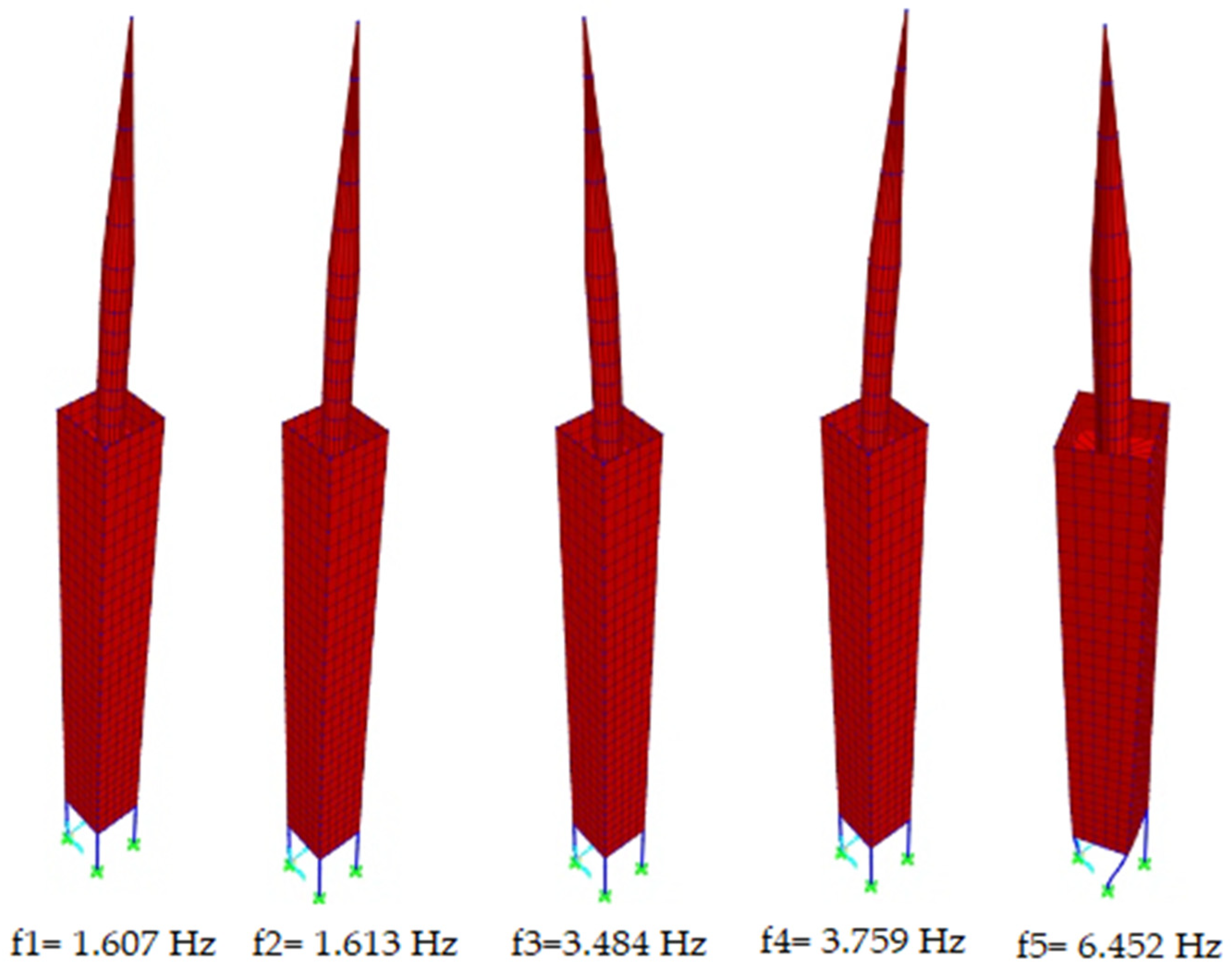

5.1. Modal Analysis

| Reference | Suggested Formula | Estimated Fundamental Frequency, f* (Hz) | f1/f* |

|---|---|---|---|

| NTC08 [45] | f (H) = | 1.911 | 0.84 |

| Shakya et al. [46] | f (H) = | 2.251 | 0.71 |

| Ranieri and Fabbrocino [47] | f (H) = | 2.493 | 0.64 |

| Faccio et al. [48] | f (H) = | 2.335 | 0.69 |

| Testa [49] | f (H) = 42.12 | 2.571 | 0.63 |

| Diaferio et al. [50] | f (H) = 28.35 | 2.108 | 0.76 |

| f (H) = 135.343 | 2.170 | 0.74 |

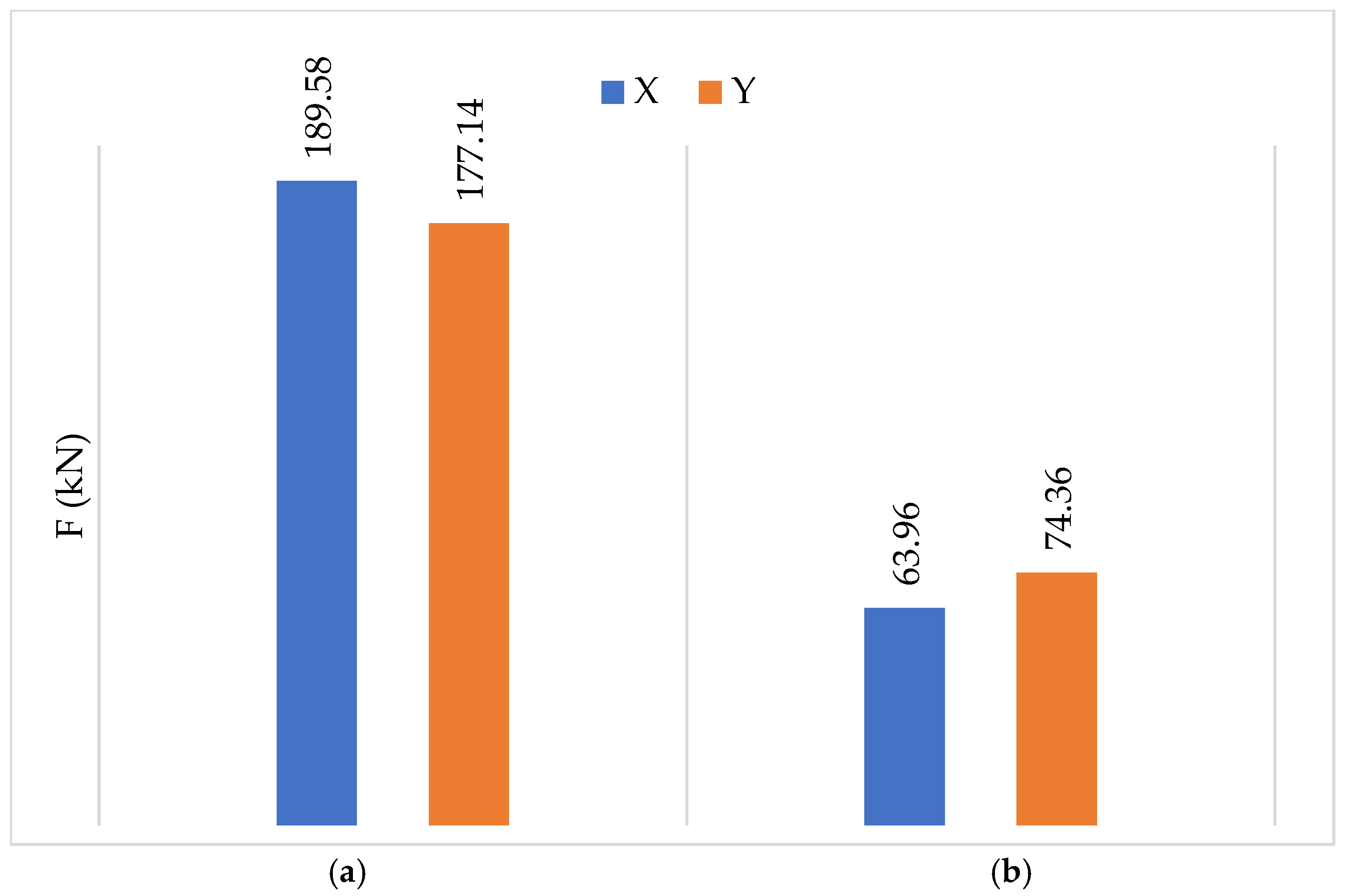

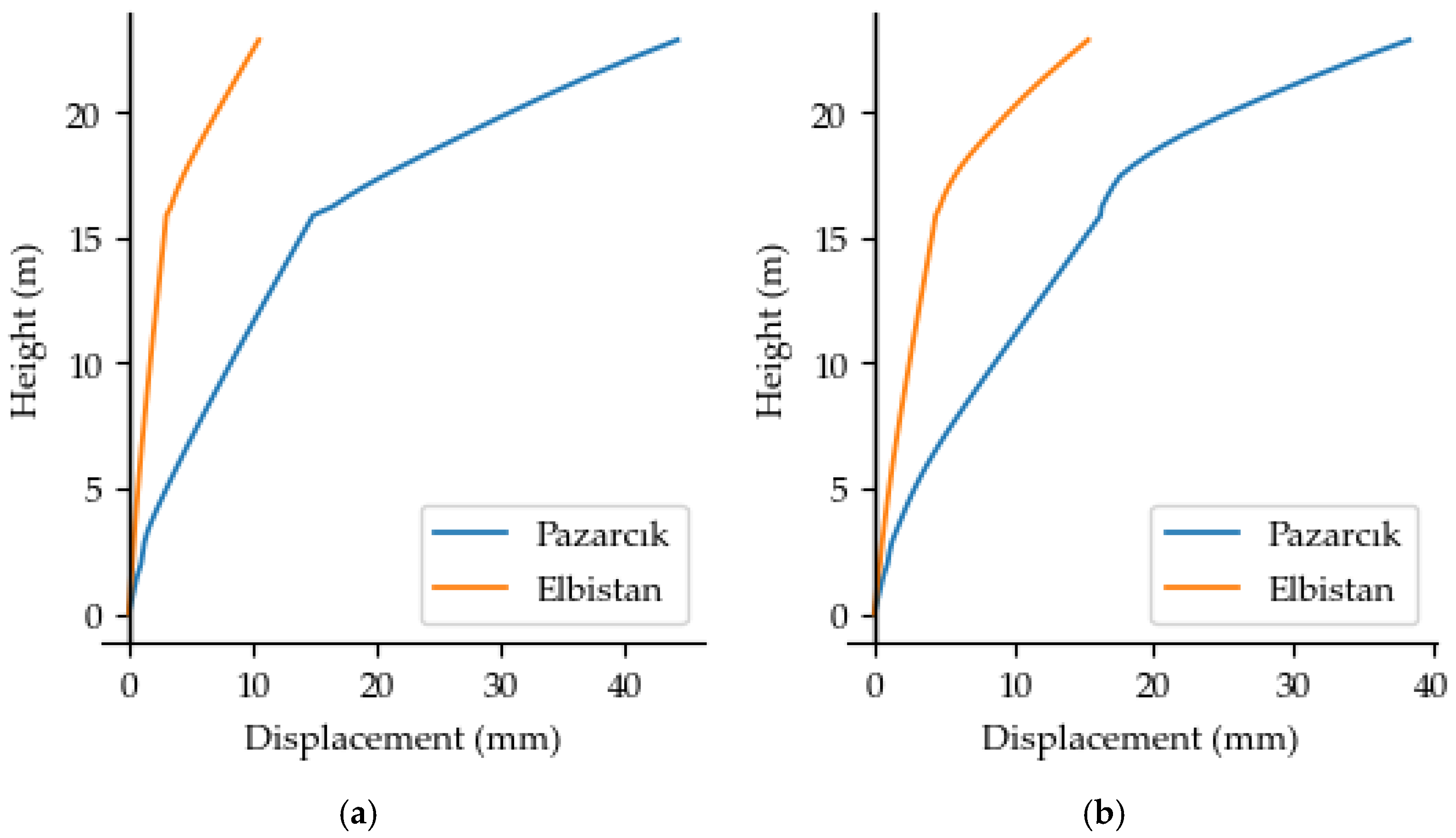

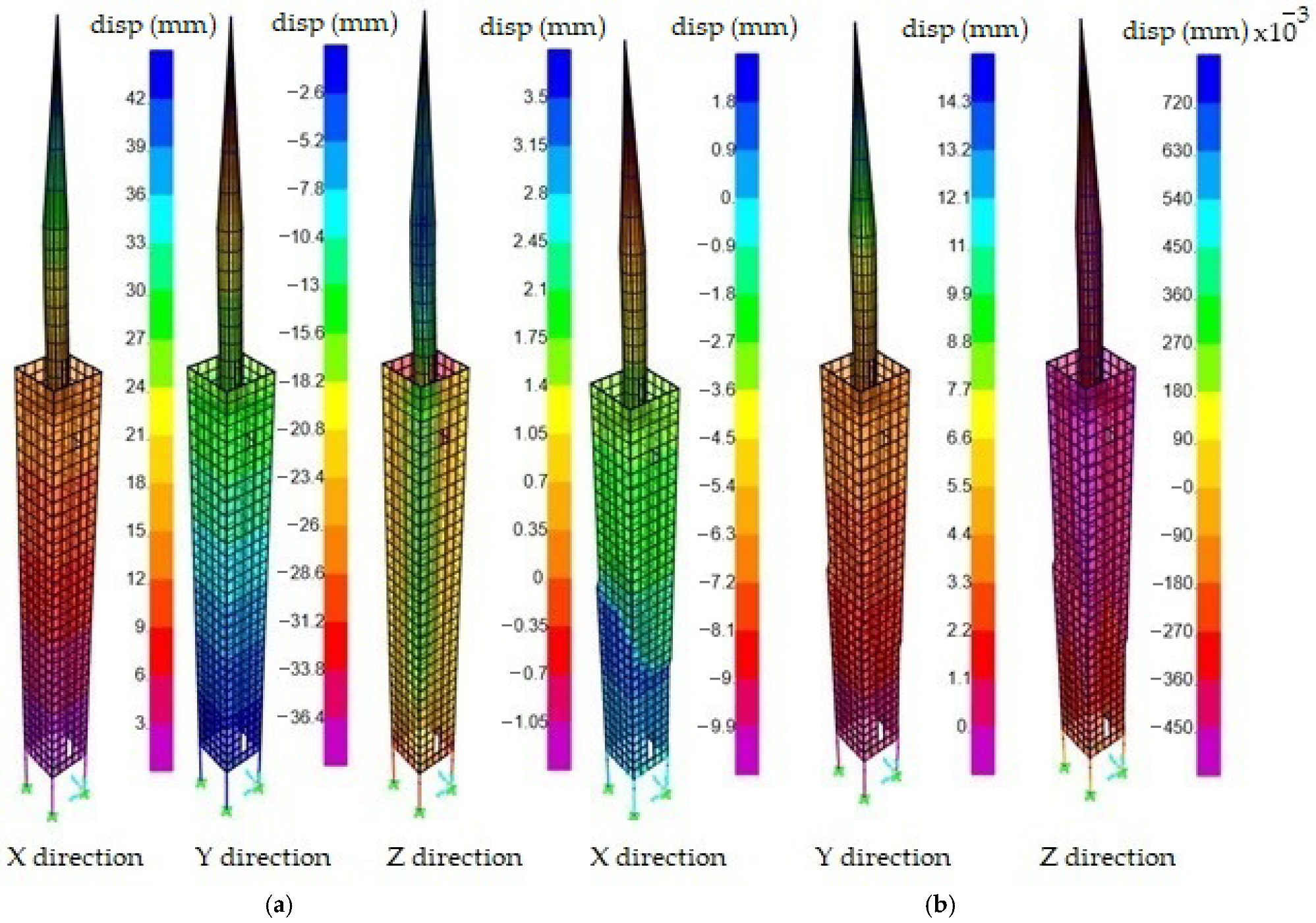

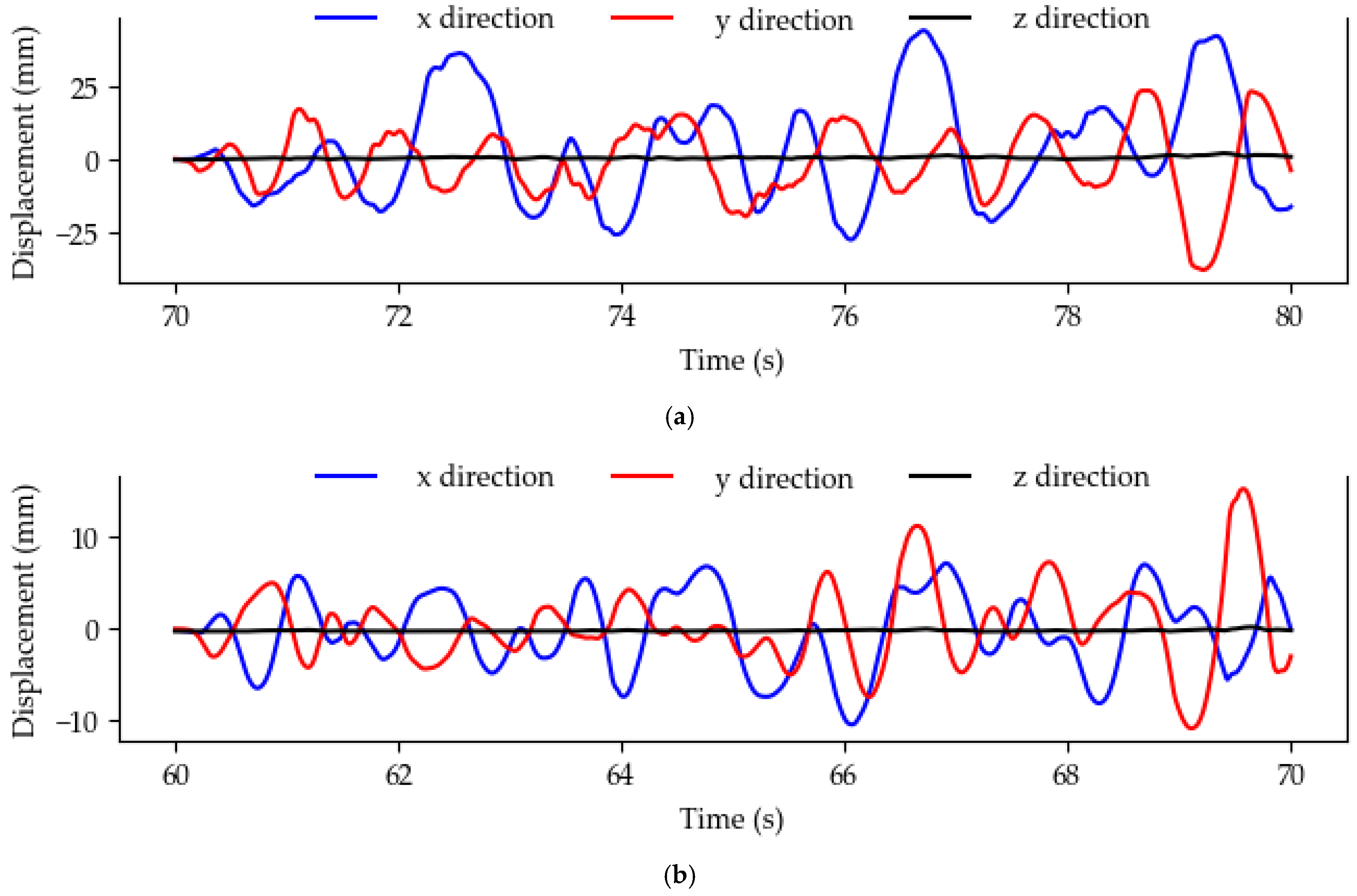

5.2. Nonlinear Time History Analysis

6. Conclusions

- Modal analysis showed a fundamental period of 0.622 s, consistent with the slender and flexible structure of the minaret. Nonlinear dynamic analyses revealed that the Pazarcık record generated significantly higher horizontal demands than the Elbistan record. Horizontal displacements increased along the height, with the largest values occurring at the top. Displacements in the X and Y directions were similar, while vertical values remained lower.

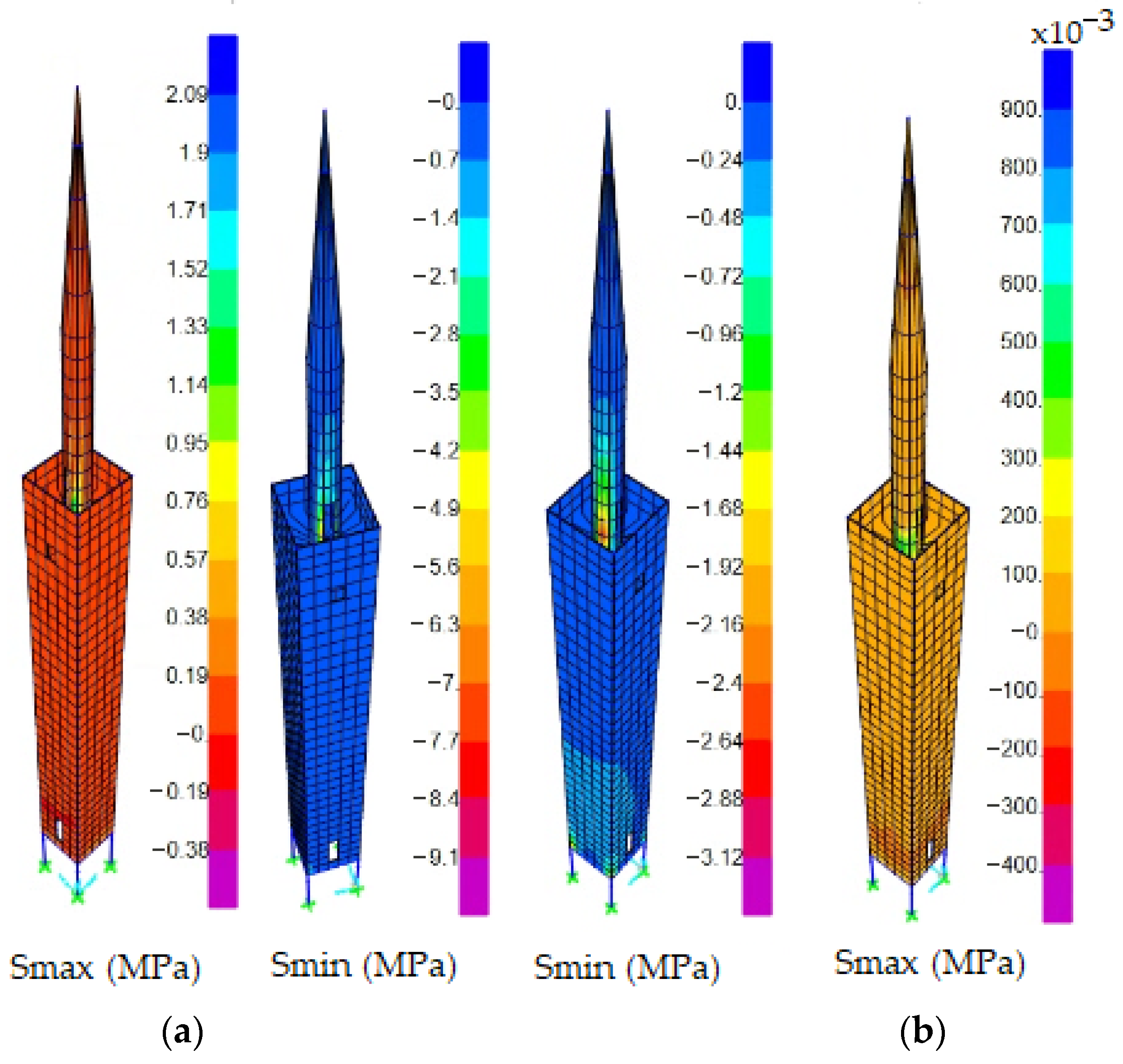

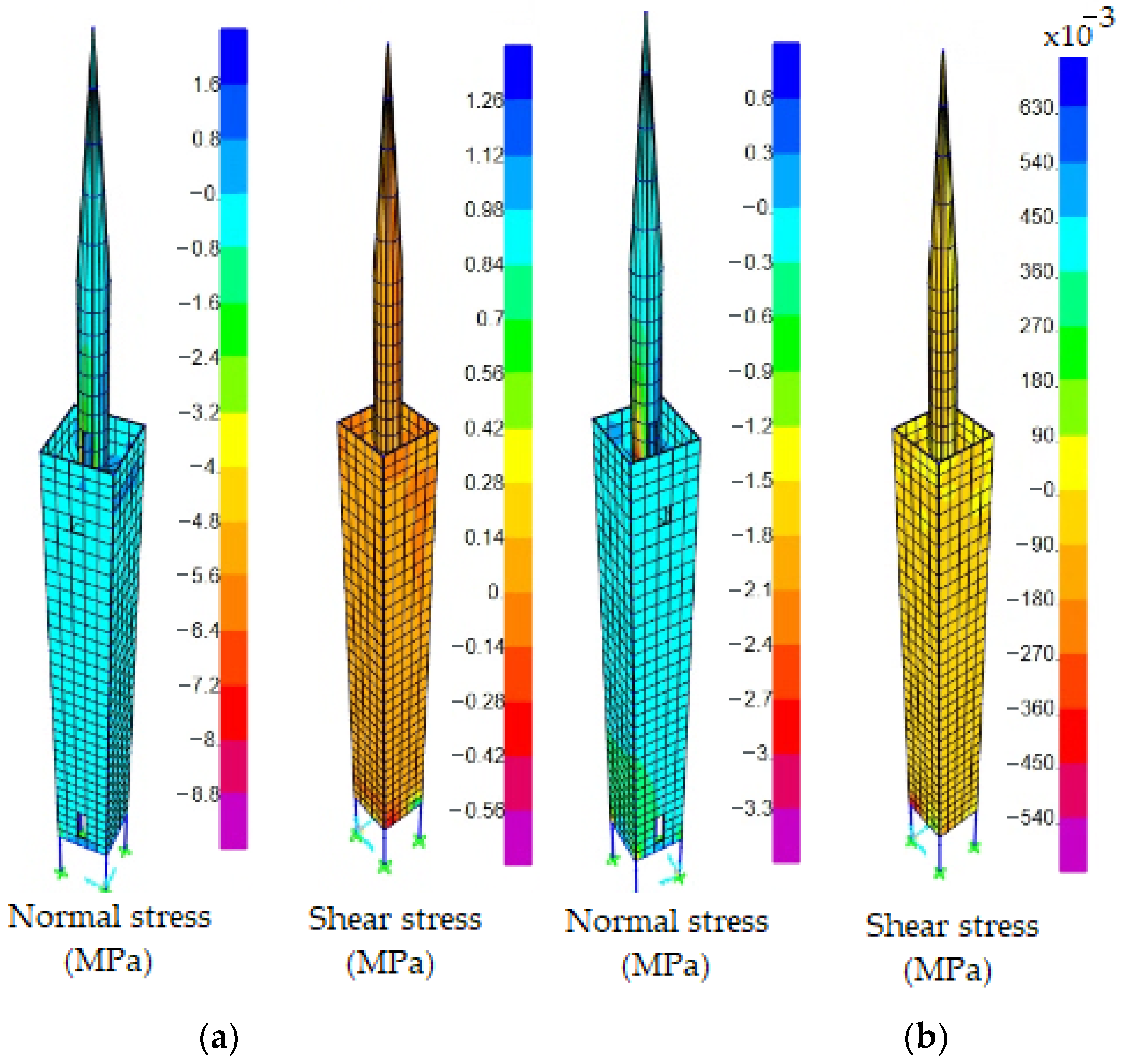

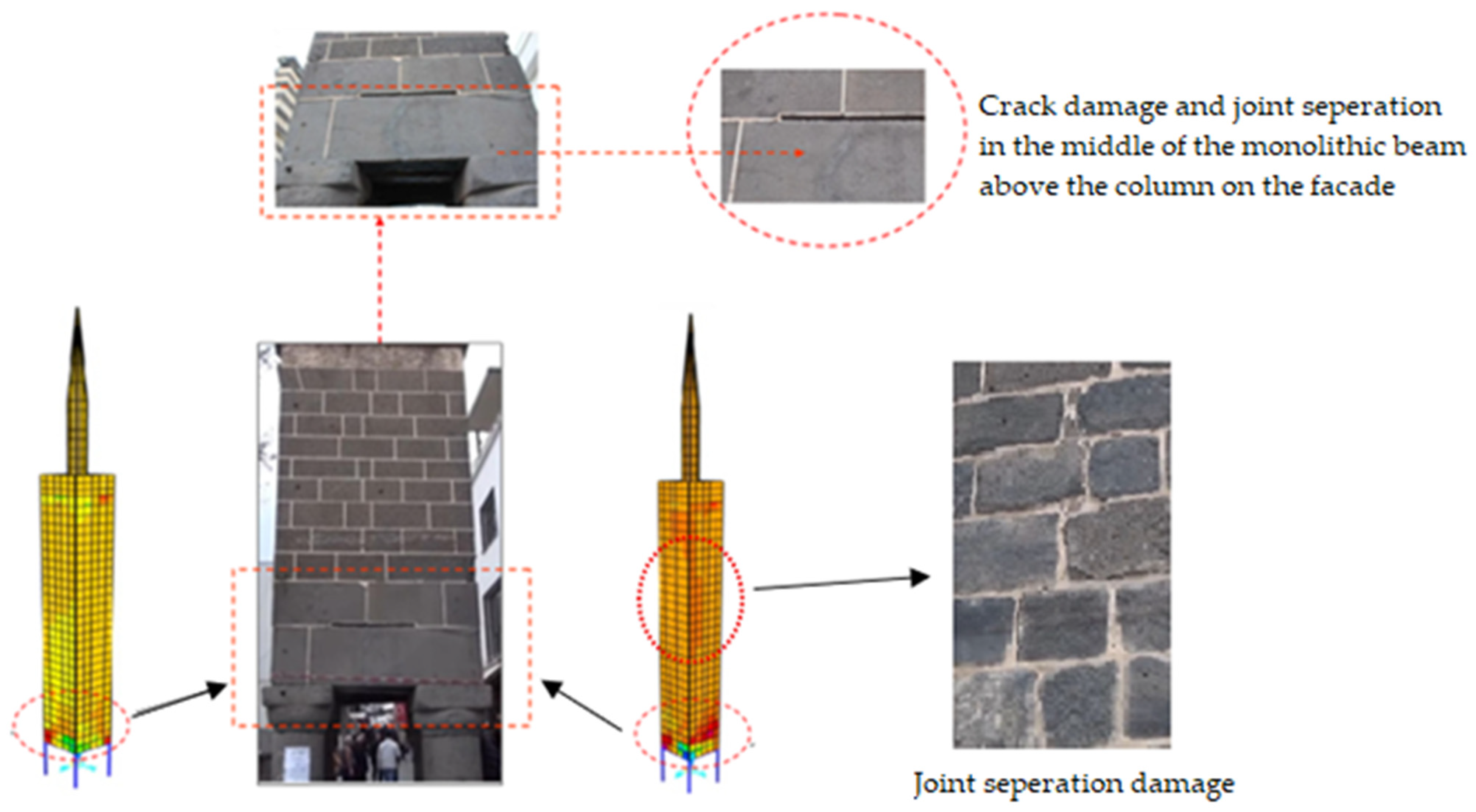

- The regions with the highest normal and shear stresses are the transition zones, particularly at the beginning of the cylindrical body. These regions are prime targets for strengthening because they coincide with the damage observed in the field; the principal stresses are also concentrated in the same region.

- Damage patterns obtained from numerical analyses showed high agreement with field observations and validated the representativeness of the used modeling approach and the selected ground motions.

- The transition from the square base to the cylindrical upper body created a distinct geometric discontinuity, leading to stress accumulation and joint separation under earthquake effects. This behavior was clearly evident both in the analyses and in the field damage.

- The monolithic beam supported by four stone columns acted as a stress amplifier under dynamic loads, creating a local stiffness discontinuity at the base. This explains the root cause of the cracks observed on the beam after the earthquake.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAFZ | North Anatolian Fault Zone |

| EAFZ | East Anatolian Fault Zone |

| WAFZ | West Anatolian Fault Zone |

| JAXA | Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency |

| ALOS-2 | Advanced Land Observation Satellite-2 |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| Caltech | California Institute of Technology |

| AFAD | Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency |

| SAP2000 | Structural Analysis Program 2000 |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| PGV | Peak Ground Velocity |

| M | Moment Magnitude |

| Vs30 | Average Shear Wave Velocity in the top 30 m of the soil |

| ZC | Local Soil Class |

| RJB | Joyner and Boore Distance |

| Sa | Spectral Acceleration |

| Smax | Maximum Principal Stress |

| Smin | Minimum Principal Stress |

References

- Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency. Earthquake. 2023. Available online: https://tadas.afad.gov.tr/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Pamukçu, O.A.; Çırmık, A.; Gönenç, T.; Uluğtekin, M. Bölüm I Yerfiziği Anabilim Dali Deprem Ön Değerlendirme Raporu; Dokuz Eylül University: Konak, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- NASA Earth Observatory. Earthquake Damage in Turkey. Available online: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/150949/earthquake-damage-in-turkiye (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA); Japan. Available online: https://global.jaxa.jp/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Singapore Earth Observatory—Remote Sensing Laboratory; Singapore. Available online: https://earthobservatory.sg/research/centres-labs/eos-rs (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change; Türkiye. Available online: https://csb.gov.tr/en (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Hasar Tespit Sistemi. Available online: https://hasartespit.csb.gov.tr/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey; General Directorate of Foundations of the Republic of Turkey. Earthquake Special; Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Ankara, Turkey, 2023.

- Ersoy, S. Evaluation of the Cultural Heritage Buildings in an Ancient District of Antakya after the Kahramanmaras Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6). J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Celebi, E.; Ozturk, H.; Ozcan, Z.; Ozocak, A.; Bol, E.; Sert, S.; Sahin, F.Z.; Arslan, E.; Yaman, Z.D.; et al. Destructive Impact of Successive High Magnitude Earthquakes Occurred in Türkiye’s Kahramanmaraş on February 6, 2023. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 893–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcil, F.; Işık, E.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Arkan, E.; Arslan, M.H.; Aksoylu, C.; Eyisüren, O.; Harirchian, E. Effects of the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaraş Earthquake on Structures in Kahramanmaraş City. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 2953–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çambay, E. Damage Assessment of Masonry Structures in Adyaman Province After Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (February 6, 2023). Firat Univ. J. Exp. Comput. Eng. 2023, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercimek, Ö. Seismic Failure Modes of Masonry Structures Exposed to Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and 7.6) on February 6, 2023. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, A. Kahramanmaraş Depreminin Yığma Yapılar Üzerindeki Etkilerinin Araştırılması. Gazi J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 9, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkan, E.; Işik, E.; Avcil, F.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A. Seismic Damages in Masonry Structural Walls and Solution Suggestions. Acad. Platf. J. Nat. Hazards Disaster Manag. 2023, 4, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, İ. The Effect of the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6) on Historical Masonry Mosques and Minarets. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 149, 107225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, O.; Deniz, F.; Özmen, A.; Özdemir, E.; Sayın, E. Performance Evaluation and Damage Assessment of Historical Yusuf Ziya Pasha Mosque after February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquakes. Structures 2023, 58, 105415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, İ.Ö.; Yetkin, M.; Erkek, H.; Calayır, Y. Nonlinear Earthquake Response of the Historic Ahi Musa Masjid. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Civil Engineering and Architecture Congress, Trabzon, Turkey, 12–14 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nasery, M.M. Investigating of the Reasons for the Collapse on the Entrance Arches of the Harran Grand Mosque (Ulu Cami) During the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6). Civ. Eng. Beyond Limits 2023, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşlu, M. Assessing Seismic Crack Performance of Diyarbakır Çüngüş Masonry Stone Bridge Considering 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, Malatya, Gaziantep Earthquakes. Bitlis Eren Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Derg. 2023, 12, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, V.; Genç, A.F.; Sunca, F.; Roudane, B.; Altunişik, A.C.; Yilmaz, S.; Günaydin, M.; Dok, G.; Kirtel, O.; Demir, A.; et al. Evaluation of Earthquake-Related Damages on Masonry Structures Due to the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş-Türkiye Earthquakes: A Case Study for Hatay Governorship Building. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 156, 107855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouraminian, M. Multi-hazard reliability assessment of historical brick minarets. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2022, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouraminian, M.; Pourbakhshian, S.; Noroozinejad Farsangi, E.; Berenji, S.; Keyani Borujeni, S.; Moosavi Asl, M.; Mohammad Hosseini, M. Reliability-based safety evaluation of the BISTOON historic masonry arch bridge. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2020, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, İ.; Gülkan, P.; Kazaz, E. Numerical Assessment of Cracks on a Freestanding Masonry Minaret. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, M.A.; Karasin, A. Evaluation of the Structural Damages of the Four-Legged Minaret. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on Advances in Civil Engineering, İstanbul, Turkey, 21–23 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kazaz, İ.; Akansel, V.; Gülkan, P.; Kazaz, E. Seismic Behavior of a Four-Legged Masonry Minaret. In Proceedings of the 15th World Congress on Earthquake Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Computers and Structures, Inc. SAP2000: Integrated Finite Element Analysis and Design of Structures—Basic Analysis Reference Manual; Computers and Structures, Inc.: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Earthquake Database. 2023. Available online: https://earthquakedatabase.com/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Erkek, H.; Yetkin, M. Assessment of the Performance of a Historic Minaret during the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6). Structures 2023, 58, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasery, M.M. Post-Earthquake Damage Assessment of Inaccessible Areas in the Harran Grand Mosque (Ulu Cami) Minaret Using Digital Twin Modeling. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Civil Engineering and Architecture Congress, Trabzon, Turkey, 12–14 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Arkan, E.; Büyüksaraç, A.; İzol, R.; Topalan, M. Structural Damage Evaluation of Mosques and Minarets in Adıyaman Due to the 06 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medyascope Deprem Bölgesinde—Ferit Aslan Diyarbakır’dan Bildiriyor: Surlar, Dört Ayaklı Minare ve Tarihi İki Cami Depremde Zarar Gördü. Available online: https://medyascope.tv/2023/03/01/medyascope-deprem-bolgesinde-ferit-aslan-diyarbakirdan-bildiriyor-surlar-dort-ayakli-minare-ve-tarihi-iki-cami-depremde-zarar-gordu/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Sözen, M. Anadoluʾda Akkoyunlu Mimarisi; Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu: Istanbul, Turkey, 1981.

- Lourenço, P.B. Computational Strategy for Masonry Structures; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hoveidae, N.; Fathi, A.; Karimzadeh, S. Seismic Damage Assessment of a Historic Masonry Building under Simulated Scenario Earthquakes: A Case Study for Arge-Tabriz. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 147, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, S.; Funari, M.F.; Szabó, S.; Hussaini, S.M.S.; Rezaeian, S.; Lourenço, P.B. Stochastic Simulation of Earthquake Ground Motions for the Seismic Assessment of Monumental Masonry Structures: Source-Based vs Site-Based Approaches. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 53, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, D.; Tomić, I.; Karimzadeh, S.; Bernardo, V.; Beyer, K.; Lourenço, P.B. Collapse Fragility Analysis of Historical Masonry Buildings Considering In-Plane and out-of-Plane Response of Masonry Walls. Eng. Struct. 2024, 319, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, S. Nonlinear Seismic Response of a Masonry Arch Bridge. Earthq. Struct. 2016, 10, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, P.; Zanini, M.A.; Modena, C. Simplified Seismic Assessment of Multi-Span Masonry Arch Bridges. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 2629–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, A.; Sayın, E. Seismic Assessment of a Historical Masonry Arch Bridge. J. Struct. Eng. Appl. Mech. 2018, 1, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, A.; Sayın, E. Seismic Response of a Historical Masonry Bridge under near and Far-Fault Ground Motions. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2021, 65, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, A.; Sayin, E. Tarihi Yiğma Bir Köprünün Deprem Davranişinin Değerlendirilmesi. Nigde Omer Halisdemir Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 9, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Research on Brittleness and Rockburst Proneness of Three Kinds of Hard Rocks under Uniaxial Compression. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8891633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disaster; Presidency, E.M. Turkey Building Earthquake Regulation; 2018. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/03/20180318M1-2.htm (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Ministero delle Infrastrutture. Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni; D.M. 14/01/2008, Gazzetta Ufficiale 2008, 29 (04.02.2008), Suppl. Ord. 30; Ministero delle Infrastrutture: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Shakya, M.; Varum, H.; Vicente, R.; Costa, A. Empirical formulation for estimating the fundamental frequency of slender masonry structures. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2016, 10, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, C.; Fabbrocino, G. Il periodo elastico delle torri in muratura: Correlazioni empiriche per la previsione. In Proceedings of the XIV Convegno ANIDIS, L’Ingegneria Sismica in Italia, Bari, Italy, 8–12 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faccio, P.; Podestà, S.; Saetta, A. Campanile della Chiesa di Sant’Antonin, Esempio 5. In Linee Guida per la Valutazione e Riduzione del Rischio Sismico del Patrimonio Culturale Allineate Alle Nuove Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni (D.M. 14/01/2008); Gangemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F.; Barontini, A.; Lourenço, P.B. Development and validation of empirical formulations for predicting the frequency of historic masonry towers. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 18, 1164–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferio, M.; Foti, D.; Potenza, F. Prediction of the fundamental frequencies and modal shapes of historic masonry towers by empirical equations based on experimental data. Eng. Struct. 2018, 156, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Pazarcık-EW | Pazarcık-NS | Pazarcık-UD | Elbistan-EW | Elbistan-NS | Elbistan-UD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station Code | 2101 | |||||

| VS30 (m/s) | 519 | |||||

| Local Soil Class | ZC | |||||

| RJB (km) | 216.91 | 255.40 | ||||

| PGA (g) | 0.072 | 0.078 | 0.034 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.0136 |

| PGV (cm/s) | 13.27 | 17.81 | 5.63 | 7.76 | 8.17 | 5.72 |

| Mode | Frequency (Hz) | Cumulative Mass Participation Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X Direction | Y Direction | Z Direction | ||

| 1 | 1.607 | 0.726 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 1.613 | 0.726 | 0.733 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 3.484 | 0.775 | 0.733 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 3.759 | 0.775 | 0.781 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 6.452 | 0.775 | 0.781 | 0.000 |

| 6 | 7.937 | 0.775 | 0.982 | 0.000 |

| 7 | 8.000 | 0.983 | 0.982 | 0.000 |

| 8 | 15.873 | 0.983 | 0.985 | 0.000 |

| 9 | 16.393 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.000 |

| 10 | 20.000 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.950 |

| 11 | 20.833 | 0.997 | 0.985 | 0.955 |

| 12 | 20.833 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.955 |

| Stress | Pazarcık | Elbistan |

|---|---|---|

| Smax (MPa) | 2.252 | 0.862 |

| Smin (MPa) | 9.104 | 3.352 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Usta Evci, P.; Sever, A.E.; Şakalak, E.; Karimzadeh, S.; Lourenço, P.B. Seismic Damage Assessment of Minarets: Insights from the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, Türkiye. Buildings 2025, 15, 4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234358

Usta Evci P, Sever AE, Şakalak E, Karimzadeh S, Lourenço PB. Seismic Damage Assessment of Minarets: Insights from the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, Türkiye. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234358

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsta Evci, Pınar, Ali Ekber Sever, Elifnur Şakalak, Shaghayegh Karimzadeh, and Paulo B. Lourenço. 2025. "Seismic Damage Assessment of Minarets: Insights from the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, Türkiye" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234358

APA StyleUsta Evci, P., Sever, A. E., Şakalak, E., Karimzadeh, S., & Lourenço, P. B. (2025). Seismic Damage Assessment of Minarets: Insights from the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, Türkiye. Buildings, 15(23), 4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234358