1. Introduction

The growing demand for sustainable construction materials has led to increased interest in utilizing recycled industrial waste in concrete, both to mitigate environmental pollution and to conserve natural resources. Among various sources of waste, cathode-ray tube (CRT) glass from obsolete televisions and monitors presents a serious disposal problem due to its high content of lead and other heavy metals. Conventional landfilling of CRT glass poses risks of leaching and long-term environmental degradation. Therefore, the reuse of CRT glass in concrete production offers a promising dual-purpose solution—addressing both solid waste management and material sustainability [

1,

2,

3].

A significant body of research has examined the use of CRT glass as a partial replacement for natural aggregate or cement in concrete. CRT glass is typically divided into panel (low lead content) and funnel (high lead content) components, each with distinct chemical and physical properties [

4,

5]. Panel glass was selected in this study due to its substantially lower lead content (typically below 2 wt%) compared with funnel glass, which may contain up to about 20–25 wt% PbO [

3,

6]. This selection minimizes the potential for heavy-metal leaching and enables safer reuse in structural concrete applications. When incorporated into concrete, CRT glass can improve workability due to its smooth surface texture and has shown enhancements in compressive strength at low replacement levels (up to 10–15%) [

6,

7,

8], though higher dosages may lead to reduced mechanical performance and increased porosity. Moreover, previous studies have indicated that environmental and durability concerns related to CRT glass, such as alkali–silica reaction (ASR) and lead leaching, can be mitigated through the use of pozzolanic materials or protective surface coatings [

9,

10,

11].

In addition, the ASR susceptibility of CRT panel glass is inherently low due to its distinct chemical composition. Panel glass contains substantially lower alkali contents (Na

2O, K

2O) and higher proportions of stabilizing oxides such as BaO, SrO, and ZnO compared with conventional soda–lime glass, resulting in reduced reactivity with cement alkalis. Previous studies have reported that mortar bars containing CRT panel glass exhibit very small expansions—well below commonly accepted AMBT thresholds of 0.10% at 14 days—confirming its low alkali–silica reactivity [

12,

13]. Although AMBT/CPT tests were not performed in this study, these findings justify the selection of panel glass as a safer and more durable recycled aggregate option.

Beyond fresh and hardened concrete properties, durability aspects—such as resistance to chloride penetration, freeze–thaw cycles, and gas permeability—have also been investigated. Treated CRT glass aggregates have demonstrated improved bonding and long-term performance, especially when integrated into geopolymer or blended binder systems [

14,

15,

16]. Scientometric reviews confirm a rising global interest in CRT-based concretes, particularly in Asia, with increasing focus on durability and microstructural characterization [

17].

While the majority of CRT studies have focused on mortar cubes or standard concrete prisms, a smaller but growing number have evaluated CRT use in structural reinforced concrete (RC) beams. One key study showed that partial replacement of natural sand with 10% CRT panel glass significantly improved the load-carrying capacity, stiffness, and crack control of RC beams [

18]. The experimental program confirmed these findings through comprehensive testing of reinforced concrete beams, where measured load-deflection curves and crack propagation trends were in close agreement with reported experimental observations. However, the performance diminished at higher CRT replacement levels, and ductility was modestly affected [

18].

In recent years, several experimental studies have combined Digital Image Correlation (DIC) with mechanical testing to evaluate the flexural and shear performance of reinforced concrete beams incorporating waste glass materials. These works investigated the use of DIC together with theoretical and experimental approaches to assess load capacity, crack propagation, and deformation behavior in beams containing recycled glass as aggregate or as partial cement replacement [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Their results confirmed the capability of DIC to capture strain distribution and crack evolution in glass-modified concrete members, providing a valuable methodological background for the present study. This research further expands that approach by integrating DIC with Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) techniques for comprehensive non-destructive assessment of CRT-modified concretes.

A related domain of CRT research has focused on its application in radiation shielding, particularly due to its high content of lead, barium, and strontium oxides. CRT funnel glass has been shown to outperform traditional aggregates in gamma and neutron attenuation, making it a viable candidate for concrete shielding in nuclear, industrial, and medical facilities [

23,

24]. Enhancements such as Bi

2O

3 and TiO

2 doping, or treatment with sodium carbonate, have been found to significantly boost attenuation capacity without compromising mechanical strength [

25,

26,

27]. These developments illustrate the versatility of CRT waste beyond structural concrete and underscore its broader sustainability impact.

To contextualize CRT in structural concrete applications, it is important to review benchmark studies on RC beams using other types of recycled or alternative materials. Bamboo reinforcement, for example, has been shown to enhance shear resistance in beams, especially when optimally spaced [

28,

29]. Similarly, concrete incorporating municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash or cable waste has shown improved ductility and environmental performance, albeit sometimes at the cost of compressive strength [

30,

31]. Advances in non-destructive testing (NDT), particularly ultrasound diffusion techniques, have provided more sensitive tools for evaluating stiffness degradation and microcracking in beams [

32]. These methods complement traditional destructive testing in offering a more complete understanding of structural behavior.

Finite element simulations and nonlinear load–deflection modeling have also become common tools for predicting crack development, deflection profiles, and residual strength in RC members [

33,

34]. Several studies have combined acoustic emission and vibration analysis for real-time condition monitoring, while others have examined the impact of unconventional stirrups or alternative cementitious materials on flexural and shear performance [

35,

36]. These insights provide a comprehensive reference point against which CRT-modified RC beams can be evaluated.

Further support for CRT integration into concrete comes from studies on bituminous mixes and ceramic tiles. In asphalt mixtures, CRT glass has improved rutting resistance and Marshall stability, while in ceramics, TiO

2-doped CRT glass has demonstrated enhanced shielding and hardness properties [

37,

38,

39,

40]. These applications highlight CRT’s compatibility with diverse binders and its performance-enhancing potential across industries.

More broadly, the use of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs)—such as fly ash, slag, and metakaolin—has become central to the development of low-carbon concrete systems. SCMs can reduce the embodied energy and CO

2 emissions of concrete production while improving strength and durability [

41]. In parallel, the use of non-traditional waste streams, including plastics, nanoclays, and recycled aggregates, has proven viable in enhancing mechanical, thermal, and sustainability metrics [

42,

43].

Despite the abundance of research on CRT integration in concrete, previous beam studies have rarely combined a full suite of non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques—particularly ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR)—with digital image correlation (DIC) for comprehensive structural evaluation. Furthermore, no prior studies have simultaneously compared multiple cement types across a 0–10% CRT replacement range to assess their combined influence on mechanical performance, crack propagation, and dielectric response. This study addresses that gap by coupling DIC, GPR, and destructive testing (DT) in a unified experimental program on concrete and reinforced concrete beams made with three cement types and varying CRT contents, providing a more complete understanding of structural and material-scale behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mix Design

Three different concrete mixtures were prepared for each of the three cement types used in this study, resulting in a total of nine distinct mixes. The cement types included Normal 42.5 N, PC 50M(S-V-L) 42.5 N; Profi 42.5 R, PC 20M(S-L) 42.5 R; and Cement without additions, all produced by “Lafarge” from Beočin, Serbia. In each series, CRT panel glass (

Figure 1) was incorporated as a partial replacement for natural aggregate in three levels: 0%, 5%, and 10%, designated as M1, M2, and M3, respectively. The recycled glass was sourced from the material recycling center “SET Reciklaža” d.o.o. in Belgrade, Serbia, a company specialized in the recycling of electronic and electrical waste. Selected CRT panel components (

Figure 1a) were crushed, ground, sieved, and physically separated into two fractions (0/4 and 4/8 mm). The particle size distribution curve of the mixed CRT fractions is shown in

Figure 2. The bulk density of CRT glass particles was determined as 3000 kg/m

3, consistent with values reported for panel-type CRT glass in the literature.

Prior to crushing, the CRT panel components were manually separated from the funnel parts to avoid high-lead contamination. All panels were thoroughly cleaned to remove dust, coatings, and any remaining electronic residues. After cleaning, the glass was mechanically crushed and ground, and metallic particles, phosphor coatings, and non-glass contaminants were removed through magnetic separation and manual inspection. The processed material was then sieved into the target 0/4 mm and 4/8 mm fractions to ensure grading compatibility with the replaced natural aggregates.

The reference mix (M1) contained only natural aggregates divided into three fractions: 0/4 mm (50.4%), 4/8 mm (25.9%), and 8/16 mm (23.7%). In M2, 5% of the fine aggregate (0/4 mm) was replaced by crushed CRT glass, while in M3, 10% of the fine aggregate (0/4 mm) and 10% of the medium fraction (4/8 mm) were substituted with CRT glass.

All mixes had the same water-to-cement ratio of 0.526, with a cement content of 360.7 kg/m3, total natural aggregate mass of 1682.0 kg/m3, and water content of 189.7 kg/m3. The mix proportion by mass was approximately 1:4.66 (cement–natural aggregate). No chemical admixtures were used in order to maintain comparable mix behavior and isolate the effect of CRT glass replacement.

The saturated surface-dry (SSD) moisture condition of all aggregates and CRT glass was accounted for when determining mix proportions to ensure consistent effective water content. Although the angular CRT particles slightly reduced workability—particularly at 10% replacement—the mixtures retained acceptable flow and compaction properties, confirming that uniform casting could be achieved without the use of plasticizing admixtures.

The detailed mix composition for all nine mixtures, including CRT replacement routes, aggregate fractions, and mass per cubic meter, is summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Concrete Specimens

A total of 126 concrete specimens were fabricated, comprising 9 reinforced concrete beam specimens (10 × 10 × 50 cm) and 117 additional non-reinforced specimens for destructive and non-destructive material testing (

Table 2).

To ensure consistent curing for all specimens, the following curing regime was applied. All concrete specimens—including cubes, prisms, and reinforced concrete beams—were demolded after 24 h and subsequently water-cured at 20 ± 2 °C for 28 days in a controlled curing room maintained at relative humidity above 95%, in accordance with EN 12390 recommendations.

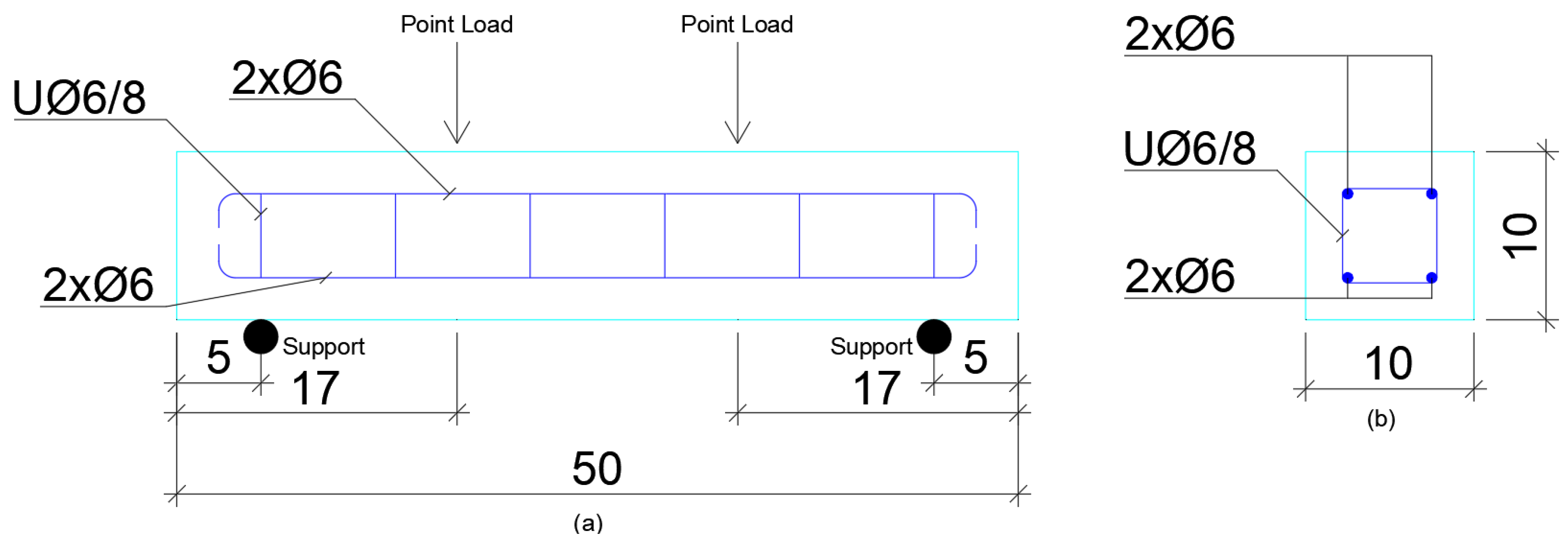

2.3. Reinforced Concrete Beams Details

The concrete beams were reinforced with 6 mm diameter ribbed steel bars, arranged with two bars at the bottom and two at the top, while 6 mm stirrups were spaced at 80 mm along the beam length. The reinforcement configuration and loading setup are illustrated in

Figure 3a,b.

The beams had a 100 × 100 mm rectangular cross-section with two Ø6 mm B500B bars in the bottom tension zone and nominal concrete cover of approximately 20 mm. This corresponds to an effective depth of about from the extreme compression fiber to the centroid of the tension reinforcement. The total area of the bottom reinforcement was , giving a tensile reinforcement ratio of (≈0.71%). Tensile tests on the B500B reinforcement, performed in accordance with EN ISO 15630-1, yielded a mean steel yield strength of .

The beams were reinforced with Ø6 mm closed stirrups at 80 mm spacing along the span. Using the measured steel yield strength and an effective depth of approximately 80 mm, a simple shear-capacity check according to EN 1992-1-1 [

44] gives a design shear resistance of about

per shear span. This value exceeds the maximum applied shear at the loading points (≈29 kN for the highest recorded peak load), confirming that the specimens were shear-safe and that the tests were governed by flexural behavior.

2.4. Experimental Testing

Natural aggregates were tested for key physical properties to ensure their suitability for concrete production. The particle size distribution was determined by dry and wet sieving methods in accordance with EN 933-1 and EN 933-8 [

45,

46]. Loose and compacted bulk density and specific gravity were measured following EN 1097-3 and EN 1097-6 [

47,

48], while water absorption was also determined in accordance with EN 1097-6 [

49]. The particle shape was characterized using the calliper method as specified in EN 933-3 [

49].

Mortar prisms made from the three types of cement were tested for density, flexural strength, and compressive strength according to EN 196-1 and EN 1015-10 [

50,

51]. All specimens were tested at standard curing times to evaluate both early and long-term performance.

Concrete in the fresh state was characterized by measuring density, slump, and flow spread according to EN 12350-6, EN 12350-2, and EN 12350-5, respectively [

52,

53,

54]. The temperature was recorded immediately after mixing, following the general best practices outlined in SRPS U.M1.032 [

55].

For hardened concrete, tests included density measurements on days 1, 28, and 90 in accordance with EN 12390-7 [

56]. Compressive strength was determined at 1, 28, and 90 days, while flexural strength was measured at 28 and 90 days following EN 12390-3 and EN 12390-5 [

57,

58]. Splitting tensile strength was tested at 28 days as per EN 12390-6 [

59]. Pull-off strength was evaluated at 30 and 90 days according to EN 1542 [

60]. Water absorption and impermeability were determined at 31 days following EN 13057 and EN 12390-8 [

61,

62], and carbonation depth was measured to assess durability. Carbonation depth was measured on 10 × 10 × 10 cm cubes following a conditioning and exposure regime consistent with fib Bulletin 34 (conceptually aligned with EN 12390-10) [

63]. Specimens were water-cured for 28 days and then pre-conditioned for 14 days at 20 °C and 65% RH before being placed in a carbonation chamber for 28 days at 20 °C, 65% RH, and elevated CO

2 concentration. After exposure, samples were split and sprayed with a 1% phenolphthalein solution to determine carbonation depth.

Nondestructive testing (NDT) of hardened concrete included rebound hammer (Schmidt hammer) tests performed at 1, 28, and 90 days in accordance with EN 12504-2 [

64], and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) testing conducted on days 1, 7, 28, and 90 following EN 12504-4 [

65].

The mechanical properties of the reinforcement were determined through destructive tensile testing, conducted in accordance with EN ISO 15630-1 [

66].

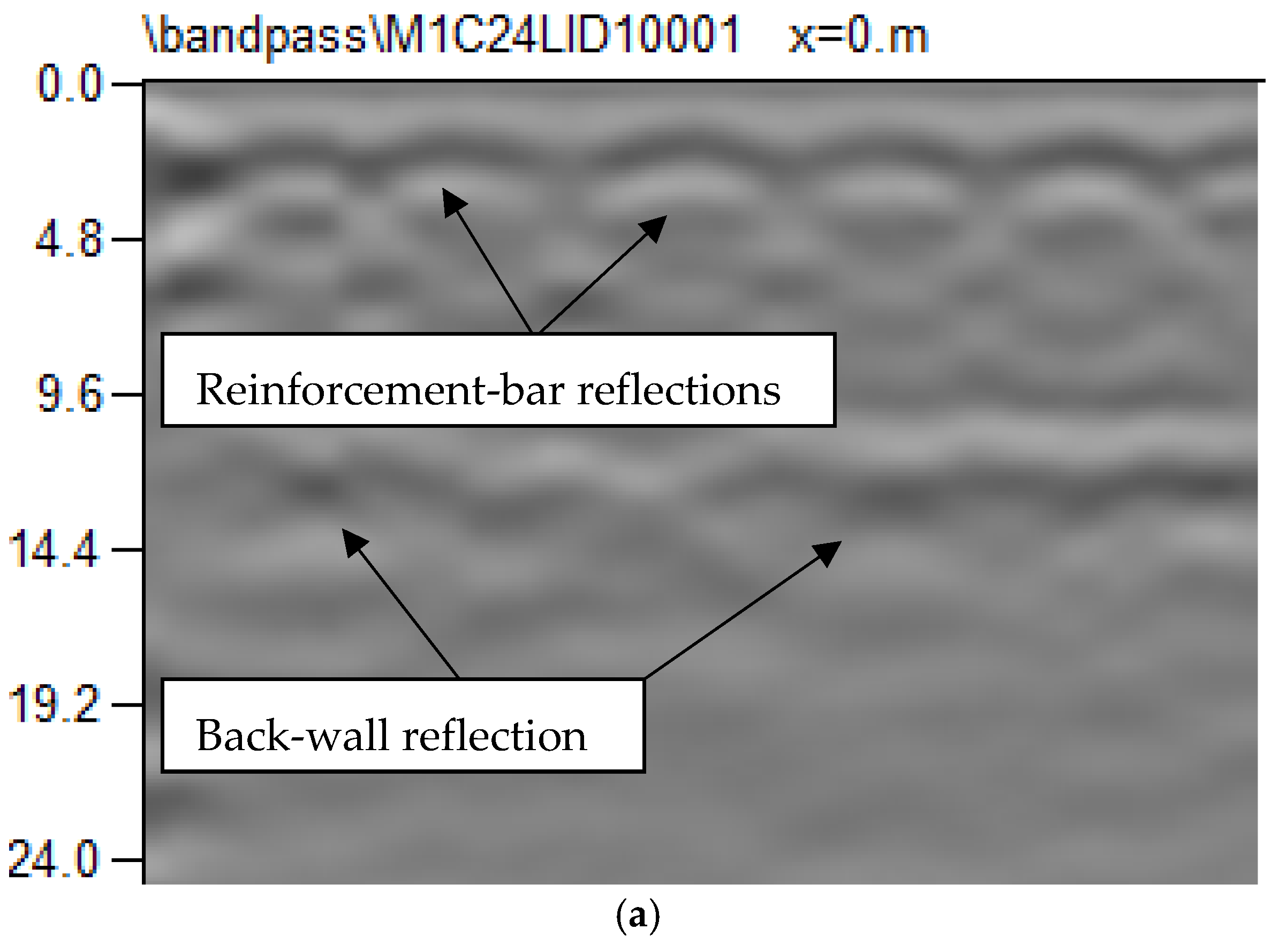

Additionally, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) testing was performed as part of the non-destructive evaluation of the reinforced concrete beams. Two antenna systems with central frequencies of 2 GHz and 3 GHz were employed to assess internal integrity and to estimate the effective dielectric constant (ε) and corresponding electromagnetic wave velocity (v). The radar data were processed using a standard sequence consisting of band-pass filtering (1.0–5.0 GHz and 1.0–4.0 GHz), background removal, whitening, and Hilbert envelope transformation to enhance reflector visibility. Distinct reflections corresponding to the reinforcement and layer interfaces were recorded across all beams, ensuring the accuracy of the internal structure prior to flexural testing.

Two ground-coupled GPR antennas were used: an IDS Aladdin bipolar antenna (2 GHz) and an IDS TR HF antenna (3 GHz). For the 2 GHz antenna, the Tx offset was −3 cm (horizontal) and +3 cm (vertical), and the Rx offset was +3 cm and −3 cm relative to the housing center, with automatic correction applied during processing. Trace spacing was 0.01 m, and the time window was 32 ns (512 samples). For the 3 GHz antenna, the Tx offset was −9 cm (horizontal and vertical), and the Rx offset was −2 cm and −2 cm, with trace spacing 0.006 m and a time window of 16 ns (512 samples). Both antennas were operated in ground-coupled mode, and any air gap was removed during processing in GPR Slice. Radar velocity was calibrated using the 3-point hyperbola-fitting method on rebar reflections, and the corresponding relative permittivity was computed. Repeated fits indicated only minor variability (uncertainty within a few percent).

A four-point bending test was conducted to determine the flexural behavior of the reinforced concrete beams (

Figure 4). During the test, the beams were subjected to an increasing load, while structural strain and displacement were continuously monitored using the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system on both sides. The DIC method was employed due to its non-contact nature, which allows for precise and full-field measurement of strain and displacement without interfering with the specimen’s surface or behavior. In addition, an LVDT was placed at midspan to measure the vertical deflection. The load at first crack was recorded, and the loading continued until failure.

A two-camera X-Sight M16 DIC system was used, consisting of two 16.1 MP Basler ace 2 cameras (Basler AG, headquartered in Ahrensburg, Germany) with Computar 25 mm Ultra Low Distortion lenses (Computar, Tokyo, Japan). The system was operated in a 2 × 2 D configuration over an approximate 500 mm field of view and complies with ISO 9513 Class 1 requirements. Calibration was performed using the X-Sight calibration grid, and all acquisition and post-processing were performed in X-Sight’s Alpha DIC software (2024 edition), X-Sight s.r.o., Brno, Czech Republic.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Concrete Mixtures with Different Cement Types and CRT Glass Content

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the results obtained for all three cement types: Normal 42.5 N, Profi 42.5 R, and Cement without additions 42.5 R—each with 0%, 5%, and 10% CRT glass replacement levels. The table summarizes the measured properties of concrete in both fresh and hardened states, including results from non-destructive and destructive testing, as well as key durability indicators and carbonation depth.

The experimental results demonstrated that the incorporation of recycled cathode-ray tube (CRT) panel glass as a partial replacement for natural aggregate did not significantly affect the fresh or hardened properties of concrete, regardless of the cement type used (Normal 42.5 N, Profi 42.5 R, or Without additions 42.5 R).

All mixtures showed similar workability and density in the fresh state. In the hardened state, density, ultrasonic pulse velocity, and surface hardness values remained nearly constant across mixes. Compressive and tensile strengths either slightly increased or remained unchanged with CRT addition, confirming that glass particles can improve interlocking and maintain mechanical integrity. Water absorption and permeability generally decreased, while carbonation depth was reduced in concretes containing CRT glass, indicating improved durability.

3.2. Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) Results

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) measurements were conducted on all reinforced concrete beams to evaluate their internal structure and dielectric properties. Two antenna frequencies (2 GHz and 3 GHz) were used, providing high-resolution radargrams that revealed consistent reflector patterns corresponding to the embedded reinforcement and layer boundaries. Signal processing included band-pass filtering, background removal, whitening, and Hilbert envelope analysis, which significantly improved reflector contrast and identification.

The effective dielectric constants (ε) and calculated propagation velocities (v) are summarized in

Table 4. For the 3 GHz antenna, ε ranged between 7.5–9.2, while for the 2 GHz antenna it ranged between 9.8–11.95, corresponding to propagation velocities from 0.087 m/ns to 0.110 m/ns.

The obtained results indicate a consistent trend in which beams with higher CRT content exhibited slightly higher relative permittivity and, correspondingly, lower inferred radar velocities. This behavior is likely associated with the intrinsic dielectric properties of the CRT-containing composite, as also reported in previous studies. Since moisture content was not explicitly measured in this study, the potential influence of moisture retention is discussed as a possible contributing factor rather than a quantified mechanism.

These findings confirm that the GPR method can effectively detect reinforcement layout, assess concrete uniformity, and indirectly indicate changes in material composition caused by CRT incorporation. The radargrams demonstrated good homogeneity and strong reflections from steel bars, validating both the construction quality and the suitability of GPR for nondestructive evaluation of small-scale reinforced concrete beams.

Figure 5a–c show representative processed B-scans for the C, P, and S series, respectively, with annotated reinforcement-bar reflections and major layer interfaces.

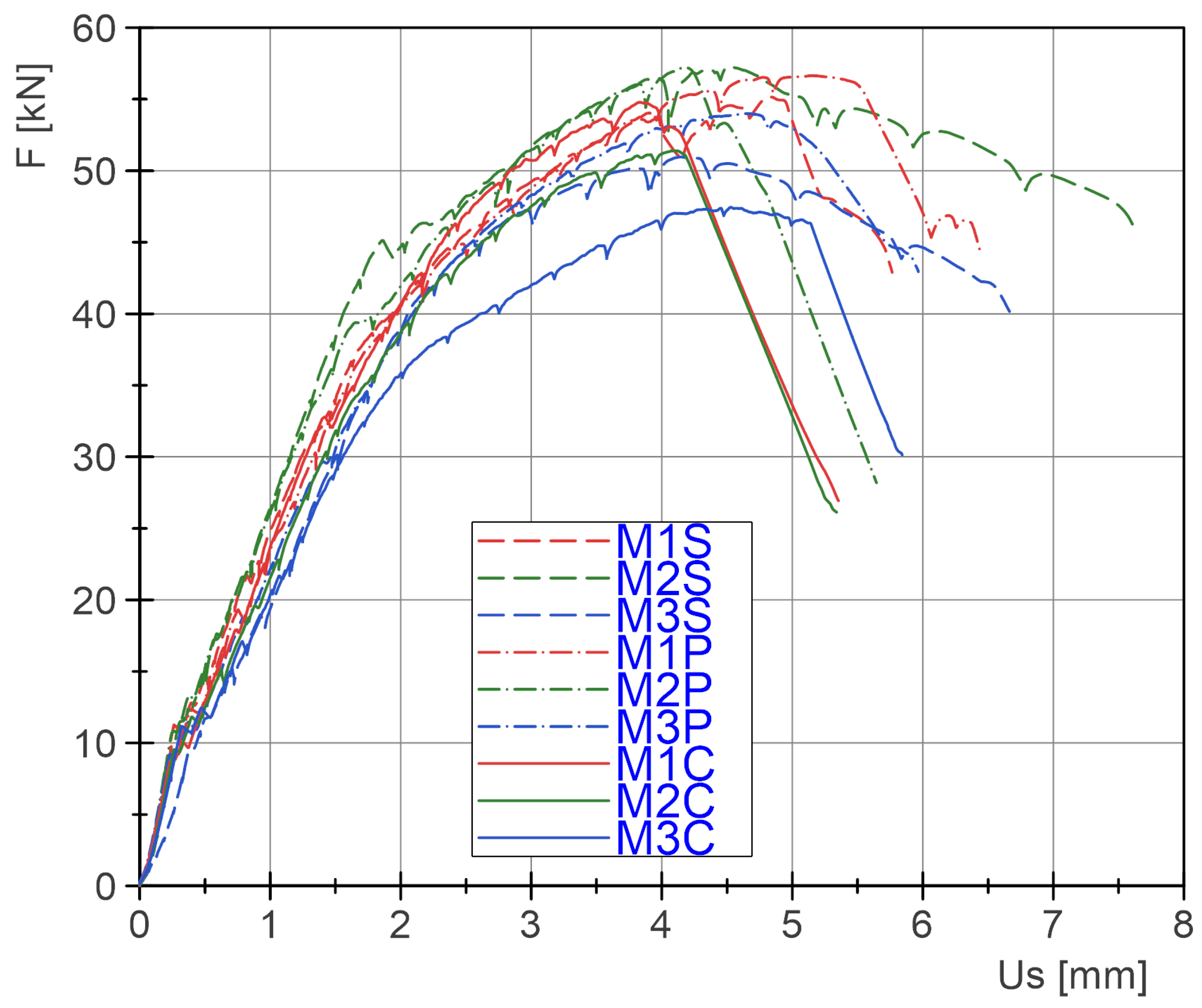

3.3. Load–Deflection Behavior

The load–deflection response of the reinforced concrete beams is shown in

Figure 6, which compiles representative curves for beams produced with Normal (S), Profi (P), and Without additions (C) cement and with CRT glass contents of 0%, 5%, and 10%. Mid-span deflection was recorded concurrently by an LVDT and a DIC system during four-point bending; the curves overlap closely, confirming consistent measurements across both methods.

All beams display an initial nearly linear segment (uncracked elastic stage), followed by a deviation from linearity marking first cracking and a progressive stiffness reduction. Post-yield, deflection accelerates until failure.

The reference beam (M1S, 0% CRT) exhibits the lowest ultimate deflection among the S-series, whereas the 5% CRT beam (M2S) shows the highest deformation capacity. The 10% CRT beam (M3S) reaches an ultimate deflection comparable to M1S but earlier in the test, indicating slightly higher initial stiffness and earlier crack development.

Profi cement (P). Curves for the P-series are tightly grouped. A moderate CRT addition (M2P, 5%) produces a marginally more ductile response than the control (M1P), while the 10% CRT beam (M3P) terminates at a somewhat lower deflection, suggesting a subtle shift toward a stiffer/brittle response at higher CRT content.

The control beam (M1C) attains the largest overall deflection within the C-series. Introducing CRT (M2C, M3C) reduces the terminal deflection and steepens the post-cracking slope, consistent with a stiffer response and more localized damage evolution as CRT content increases.

Across all three cement types, a 5% CRT replacement generally enhances deformability (greater or more sustained deflection before failure), while 10% CRT tends to decrease ductility and promote a stiffer, more brittle behavior. Differences among binders are modest in shape but systematic: the P-series shows the most uniform, balanced curves; the C-series exhibits the strongest tendency toward stiffness at higher CRT contents; and the S-series clearly displays the ductility peak at 5% CRT.

Table 5 reports peak load (Pmax) and ductility index (μΔ = Δu/Δy), with percentage changes relative to the 0% CRT control within each binder series. For the Normal cement (S), 5% CRT yielded modest gains in Pmax (~+5%) and μΔ (~+5%), whereas 10% CRT slightly reduced Pmax (~−5%) and maintained μΔ near the control. For the Profi cement (P), both 5% and 10% CRT showed similar Pmax to a mild decrease (0 to ~−9%), together with a reduction in μΔ (~−15%), indicating a more brittle response. For the binder without additions (C), 5% and 10% CRT led to small decreases in Pmax (~−5 to −7%) and μΔ (~−5 to −10%). As one beam was tested per condition (n = 1), inferential statistics (

p-values) are not applicable for the beam results; thus we report effect sizes (percent changes) and document this limitation. Multiple specimens were tested at the material level (e.g., compressive, flexural, and tensile strength), and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation with

p-values provided where applicable.

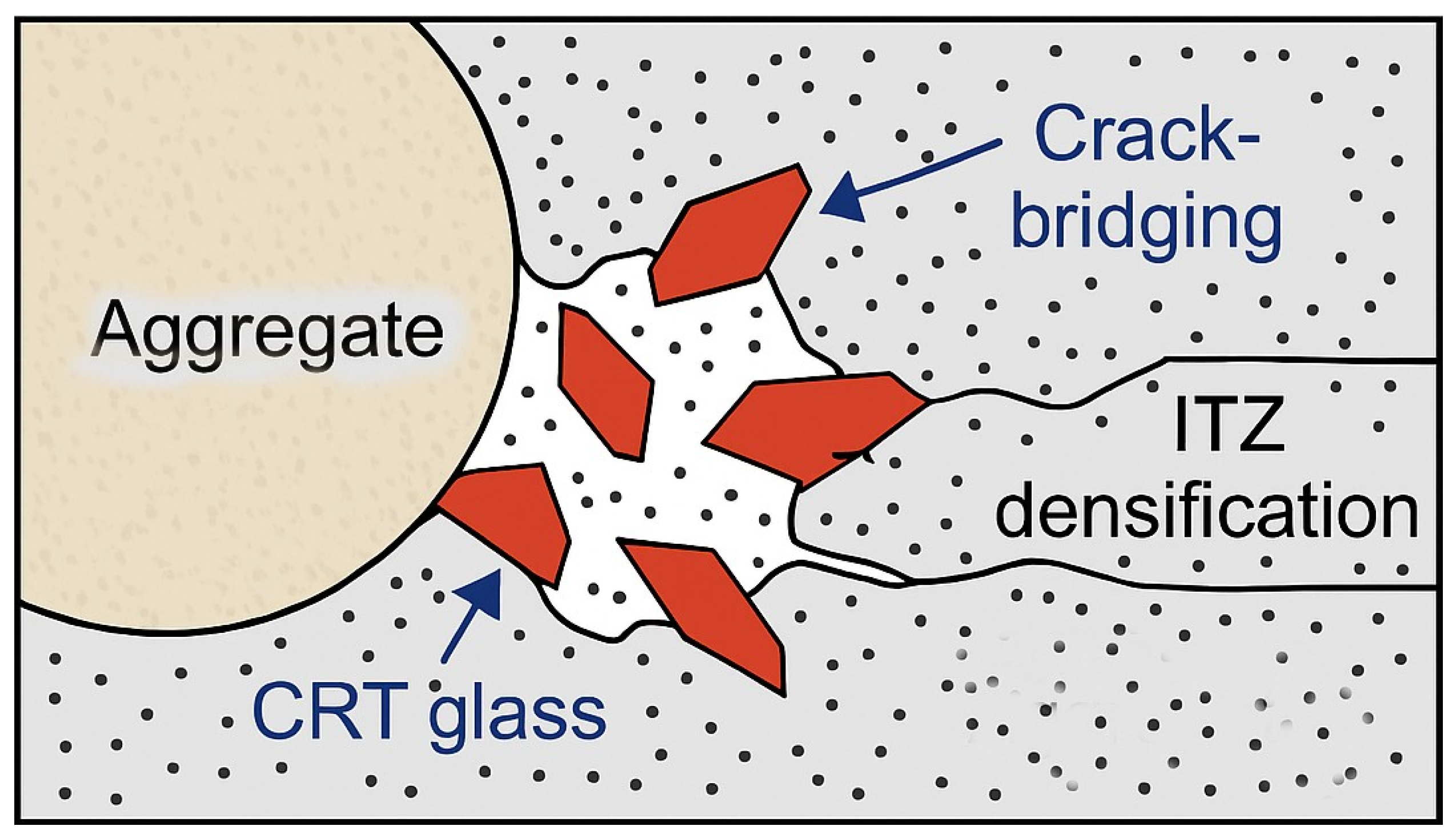

The observed improvement in ductility at 5% CRT content can be attributed to microstructural effects within the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), as illustrated in

Figure 7. At this moderate replacement level, the presence of angular CRT glass particles enhances ITZ packing by filling voids and refining the local particle distribution, which improves bond quality and stress transfer between the cement paste and aggregate. Additionally, the angular morphology of the glass particles promotes localized crack-bridging, delaying crack propagation and allowing greater deformation prior to failure. At higher CRT contents (10%), these beneficial effects diminish as particle agglomeration and increased porosity weaken the matrix, producing a stiffer and more brittle behavior. This explanation aligns with previously reported microstructural evidence for concretes incorporating recycled glass [

6,

7,

9,

16].

3.4. Crack Pattern and Failure Mode

The cracking behavior and failure mechanisms of the reinforced concrete beams were examined using Digital Image Correlation (DIC). The analysis provided displacement and strain fields that revealed the initiation, propagation, and localization of cracks under four-point bending. For each beam, two DIC outputs are presented: the vertical displacement field (DY), illustrating global deformation and deflection shape, and the principal strain field (E1), which identifies zones of maximum tensile strain corresponding to crack formation.

3.4.1. Beams with Cement Without Additions (C)

Figure 8a–f show the DIC results for beams produced with Cement without additions (C) and CRT glass contents of 0%, 5%, and 10%.

The control beam (M1C, 0% CRT) exhibits a single dominant flexural crack near the midspan, with high vertical displacement concentrated in the central loading zone. The corresponding strain map reveals a clearly localized tension band at the bottom fiber, confirming a typical flexural failure pattern.

For M2C (5% CRT), the DY map displays a slightly wider deflection shape, while the E1 field shows several fine cracks distributed along the tensile zone. This indicates a more gradual stiffness degradation and improved strain redistribution compared to M1C.

In contrast, the beam with 10% CRT (M3C) demonstrates a stiffer global response, as evident from the DY field, and a pronounced strain localization along one major crack in the E1 field, suggesting a brittle failure mode with limited post-cracking ductility.

3.4.2. Beams with Profi Cement (P)

Figure 9a–f present the DIC maps for beams with Profi cement (P).

The control specimen (M1P) shows a uniform curvature and moderate crack opening along the span, confirming a balanced stiffness–ductility response. In the DY map, deflection increases gradually toward midspan, while the E1 map displays several fine, parallel cracks without abrupt localization, indicating a ductile flexural behavior.

When 5% CRT glass was introduced (M2P), the DY field reveals slightly higher deformation and a smoother deflection curve. The strain map shows dispersed microcracks along the tensile region, implying enhanced energy dissipation and improved crack distribution due to the inclusion of CRT particles.

The beam containing 10% CRT (M3P) shows a steeper gradient in the DY field and a narrower strain concentration in the E1 field, pointing to reduced ductility and more localized damage compared to M2P.

3.4.3. Beams with Normal Cement (S)

The DIC results for the Normal cement series (S) are shown in

Figure 10a–f.

The reference beam (M1S) displays a typical flexural crack at the midspan, with peak deflection localized in the central zone, as evident from the DY field. The strain map reveals one distinct principal crack and smaller secondary cracks near the supports.

For the mixture with 5% CRT glass (M2S), the DY map indicates a slightly higher deformation profile, while the E1 field highlights multiple fine cracks across the span, suggesting a more distributed cracking pattern and improved ductility relative to the control beam.

Finally, M3S (10% CRT) exhibits a steeper vertical displacement gradient and dominant strain localization, consistent with a stiffer and more brittle fracture behavior similar to that observed in the M3C beam.

Failure classification and DIC–photo mapping. Based on DIC principal-strain (E

1) hot-spots and post-test photographs, all nine beams were classified according to the dominant failure mechanism.

Table 6 summarizes this classification, including DIC hot-spot positions, photographic evidence (front/reverse:

Figure 11 and

Figure 12), and remarks on rebar strain. Flexural-tension failure was identified when vertical crack bands initiated in the constant-moment region and localized toward midspan, with stable curvature growth and no diagonal macro-cracks in the shear spans. Shear–flexure interaction was flagged when diagonal cracking in the shear spans co-existed with midspan flexural cracks and contributed to stiffness loss. Bar slip was considered when crack opening localized at the anchorage zones with visible rib impressions and a rapid load drop without extensive flexural cracking.

The governing mechanism in all cases was flexural-tension cracking in the constant-moment region, with ductility sensitive to CRT content and binder type.

Reinforcement strain remark. No strain gauges were installed on the rebars in this series. Steel yielding was therefore inferred indirectly from the bilinear approximation of the load–deflection curves (yield deflection Δy) and the corresponding change in secant stiffness, cross-checked with DIC-observed crack development. This limitation and recommendation for future work were added to

Section 4.

4. Discussion

The experimental findings confirmed that the inclusion of cathode-ray tube (CRT) glass alters the mechanical and cracking behavior of reinforced concrete beams. Across all cement series, the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) analysis revealed that the addition of 5% CRT glass resulted in more finely distributed cracks, smoother strain transitions, and improved deformation capacity, indicating enhanced ductility and energy absorption. Conversely, at 10% CRT content, the strain fields were dominated by one major localized crack, reflecting reduced deformability and a more brittle response.

Among the cement types, beams with Profi cement (P) demonstrated the most balanced behavior, combining uniform crack distribution with moderate stiffness and ductility. Beams made with Cement without additions (C) exhibited the stiffest and most localized failures, while the Normal cement (S) series displayed the most pronounced ductility improvement at 5% CRT incorporation. The observed variation in response can be attributed to the differences in clinker composition, fineness, and hydration kinetics of the employed cement types. The balanced mechanical response observed in beams produced with Profi cement (CEM II/A-M 42.5 R) can be attributed to its optimized fineness and mixed clinker mineralogy, typically characterized by a moderate C3S/C2S ratio and the presence of finely ground limestone and slag components. The higher specific surface area of this cement promotes faster early hydration and denser microstructure formation, which improves bond development within the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and enhances energy dissipation under flexural loading. In contrast, the pure clinker cement displayed higher stiffness but lower strain tolerance, while the Normal 42.5 N type exhibited greater deformation capacity but less uniform crack propagation. These results indicate that blended binders with controlled fineness and supplementary mineral additions provide better compatibility with CRT glass aggregates by mitigating potential alkali–silica reactivity and maintaining a balanced stiffness–ductility ratio. Therefore, for mixtures incorporating CRT glass, the use of moderately blended CEM II-type cements with enhanced fineness is recommended to ensure binder–aggregate synergy and long-term durability.

The photographs of the fractured beams (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) corroborate the DIC strain maps, with visible surface cracks coinciding with strain concentration zones. This alignment validates the precision of non-contact optical measurements and emphasizes the suitability of DIC for assessing strain distribution and crack evolution in small-scale beams.

The Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) measurements further supported these findings by confirming internal uniformity and consistent dielectric behavior among beams. A systematic increase in the effective dielectric constant with higher CRT content was observed, consistent with the higher permittivity and moisture retention of glass particles. These results demonstrate that GPR can effectively detect reinforcement, assess material uniformity, and identify subtle compositional changes due to recycled additions—making it a valuable complementary tool to mechanical testing and DIC.

When compared with previous research on CRT-modified concretes, the results of this study align well with trends reported for mixes containing up to 10–15% recycled glass, where low-level incorporation typically enhances or maintains compressive strength while improving flexural behavior and crack control [

6,

7,

8,

9,

16]. The consistent improvement in flexural tensile strength observed here reinforces the notion that CRT glass contributes to better particle packing and interfacial transition zone (ITZ) performance, while excessive contents tend to disrupt the matrix continuity, leading to brittleness.

From a sustainability perspective, these results underscore the dual benefit of CRT use—mitigating electronic waste disposal and reducing natural aggregate consumption. However, further optimization of glass particle gradation, surface roughness, and cement compatibility could improve the balance between strength, ductility, and durability. Additionally, the potential influence of alkali–silica reactivity (ASR) should be examined to ensure long-term stability.

In summary, the combination of DIC, GPR, and mechanical testing provided a comprehensive understanding of the structural response of CRT-modified beams. The integrated results confirm that a 5% CRT addition enhances ductility without compromising strength, while higher replacements promote stiffness and brittleness. These insights provide a reliable foundation for future research and the practical adoption of recycled CRT glass in sustainable structural concretes.

A limitation of this study concerns the absence of direct rebar strain measurements. While rebar strain was not directly recorded in this campaign, yielding was inferred from bilinear fits of the load–deflection response and corroborated by DIC crack evolution; future studies will include embedded strain gauges or optical-fiber sensors to directly quantify steel strain and bar-slip onset.