A Machine Learning Approach for Factor Analysis and Scenario-Based Prediction of Construction Accidents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

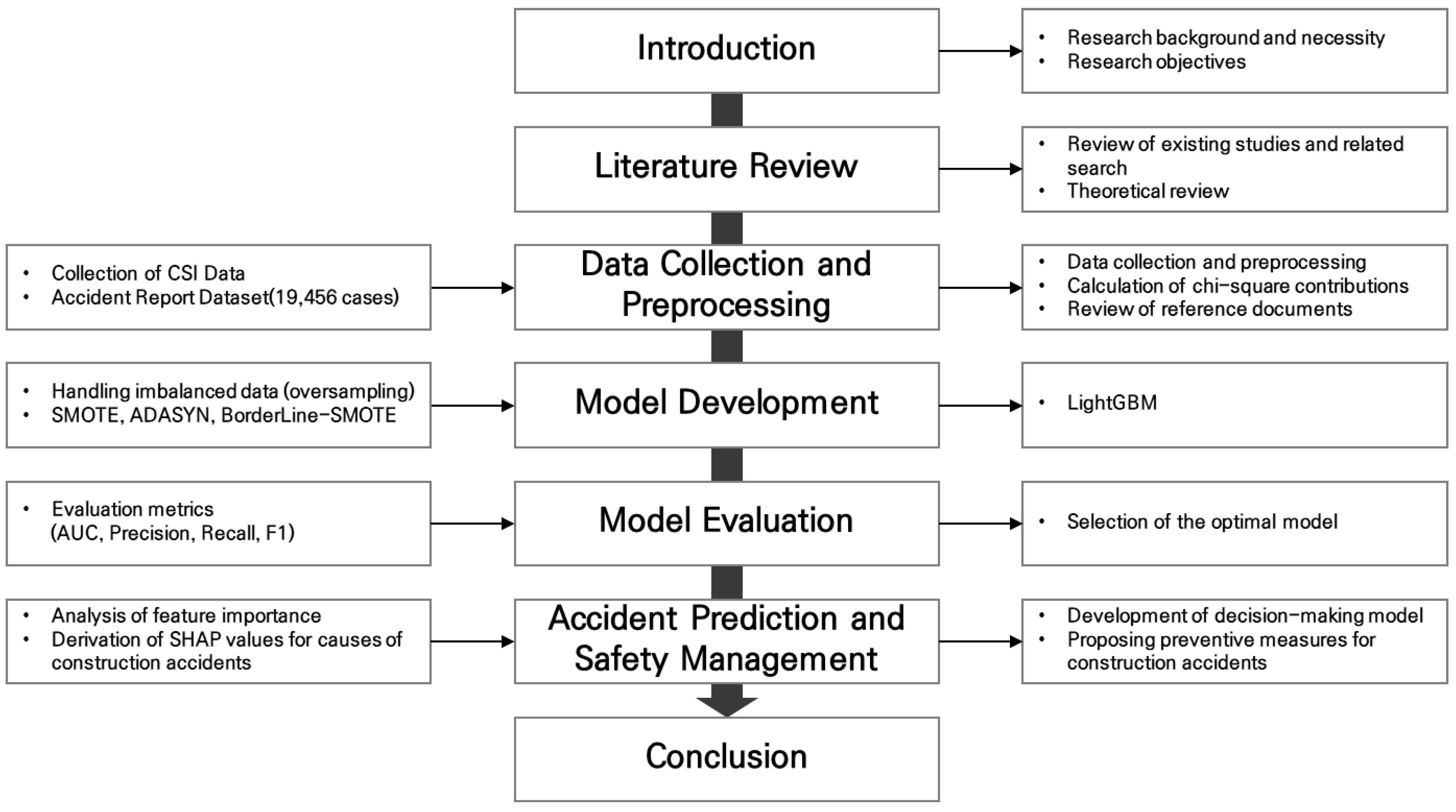

3. Materials and Methods

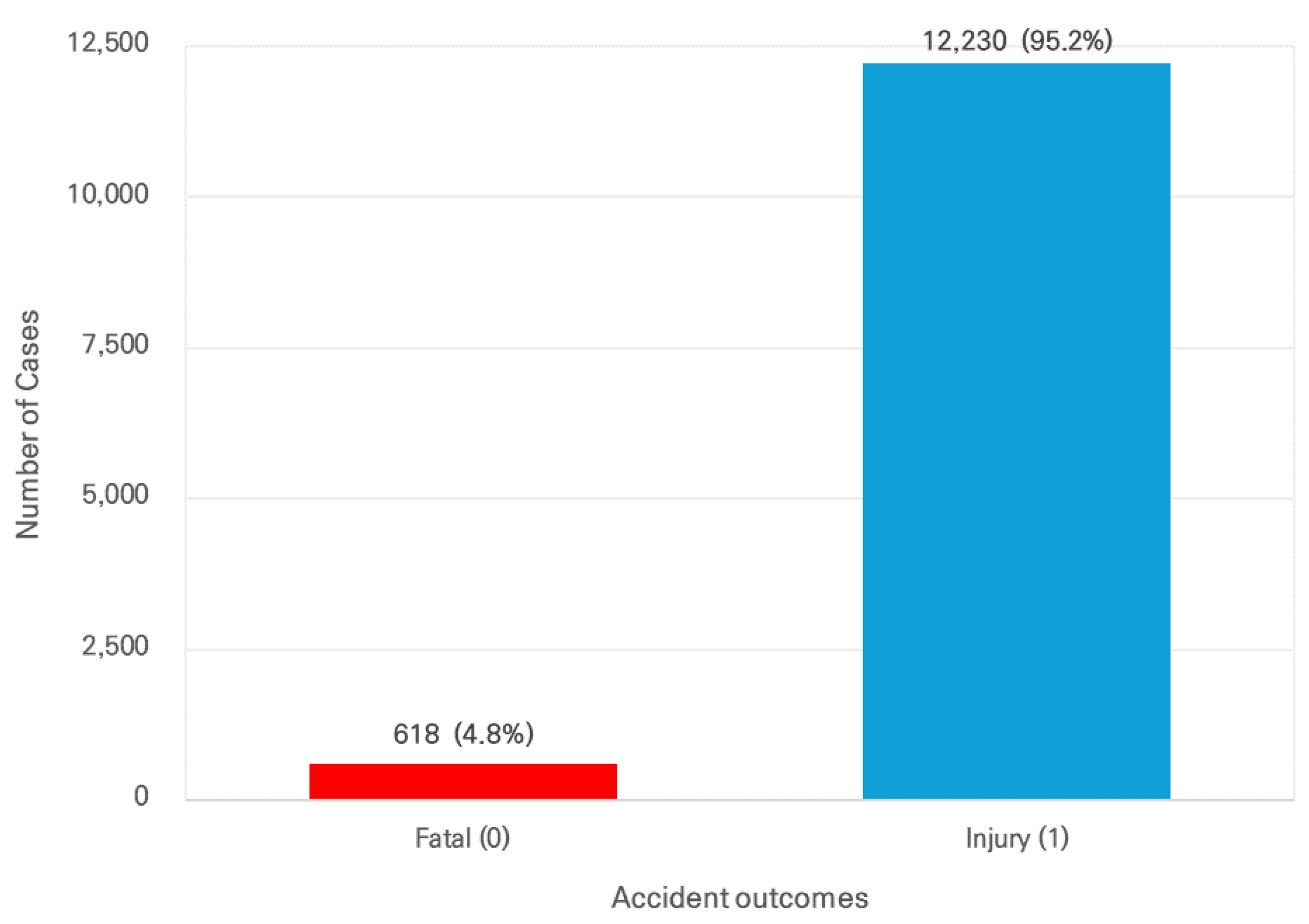

3.1. Dataset Overview

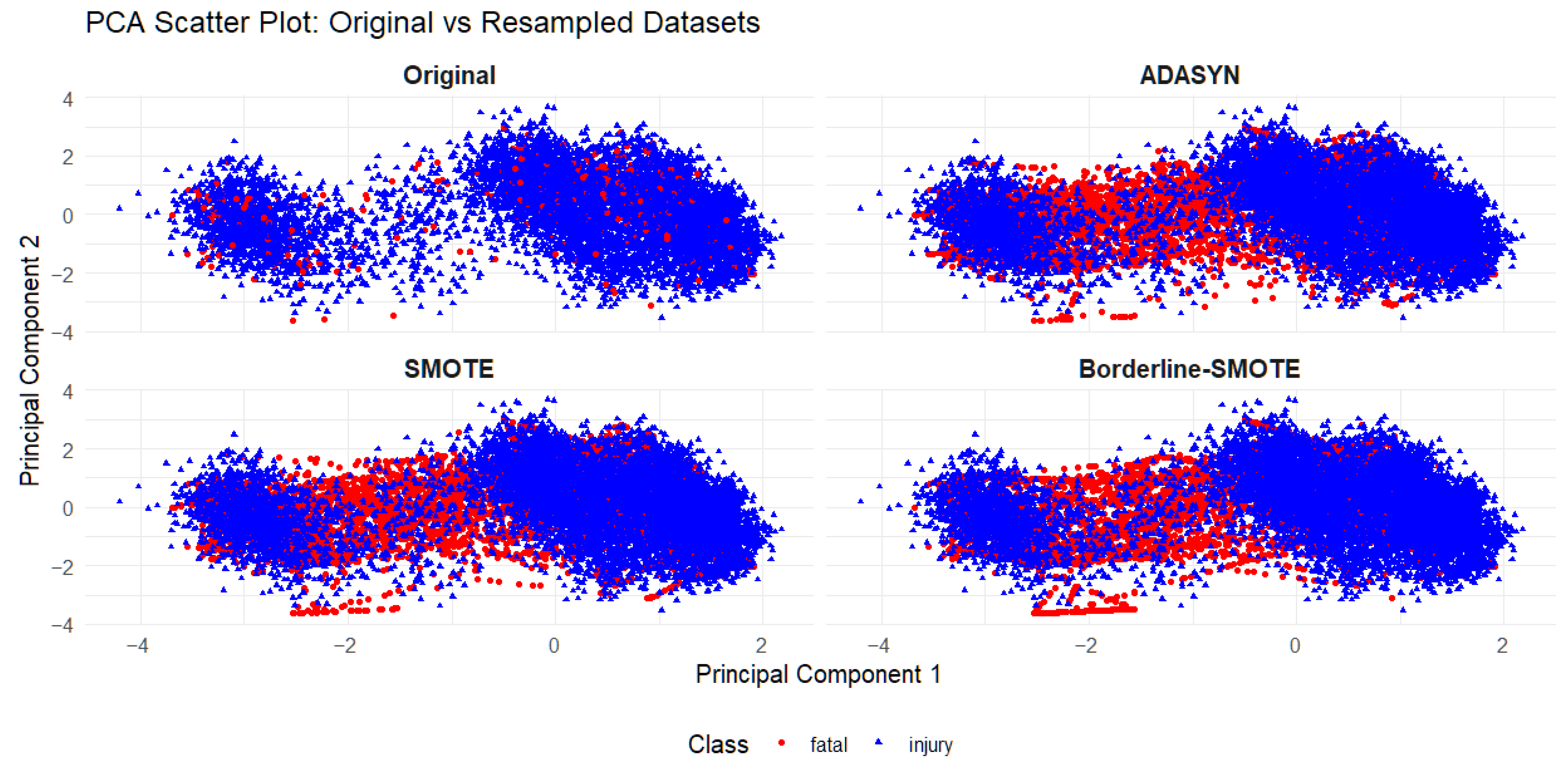

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Class Imbalance Handling

3.3. Model Design

4. Results

4.1. Oversampling and Data Distribution

4.2. Model Performance Evaluation

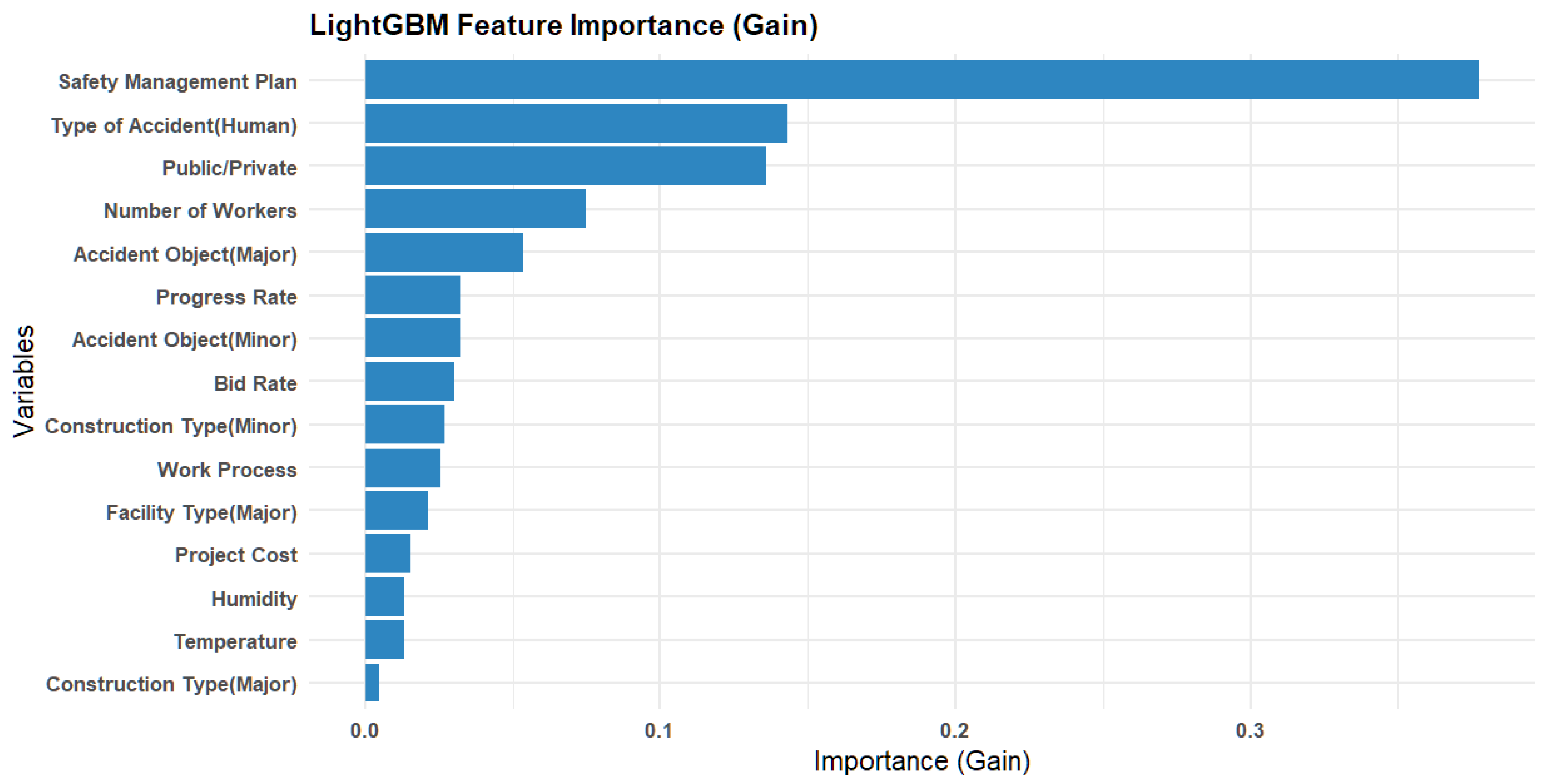

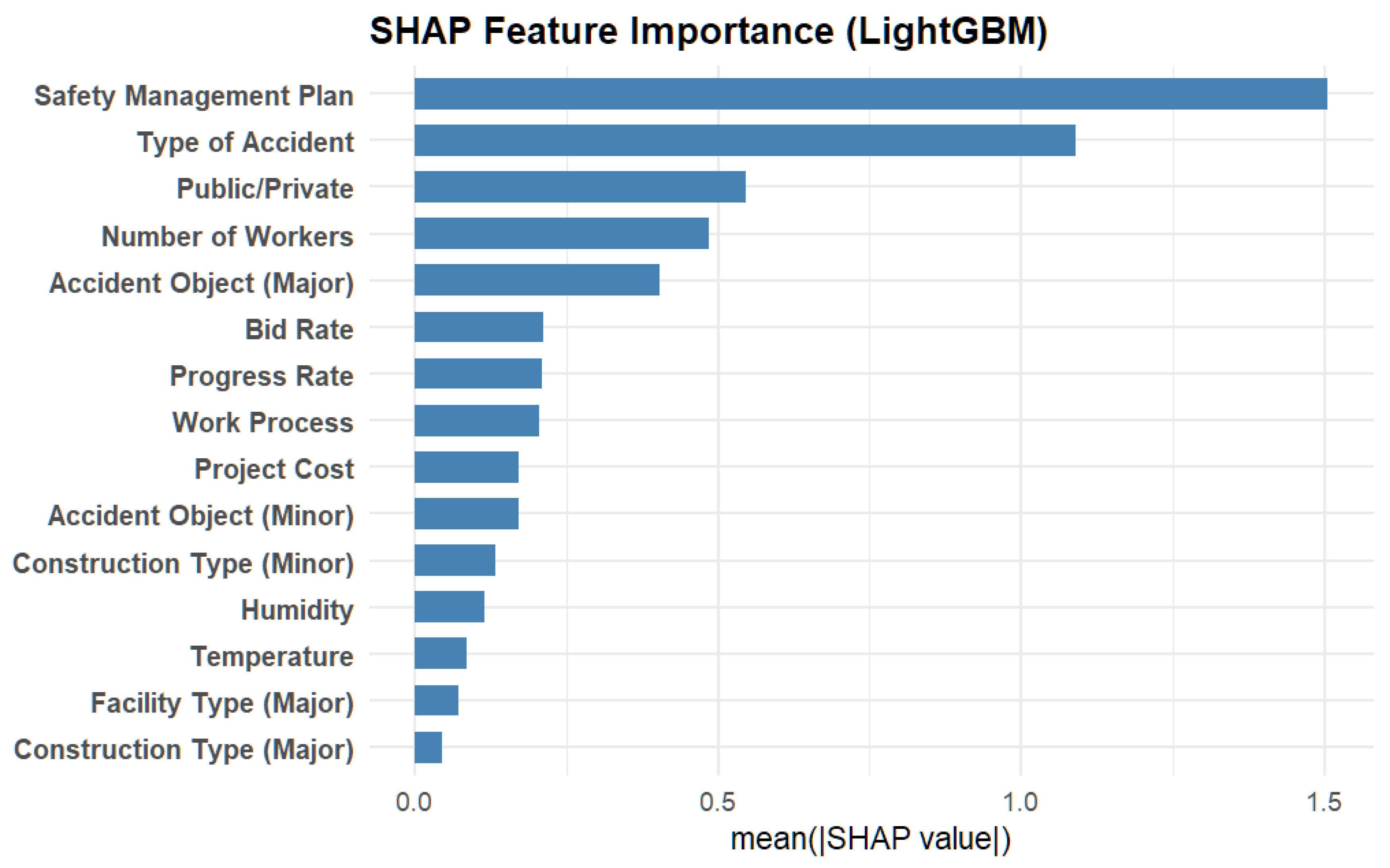

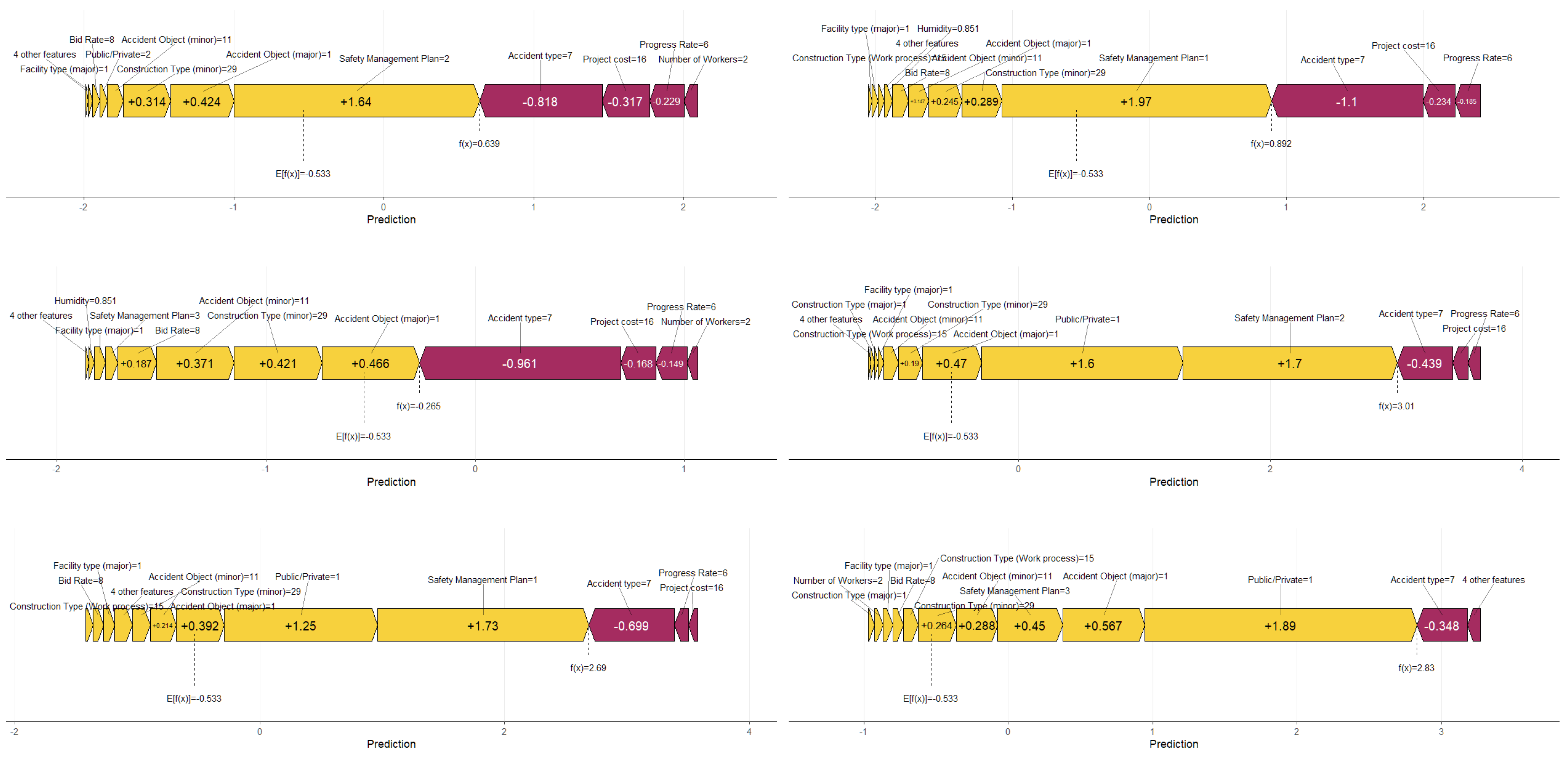

4.3. Variable Importance

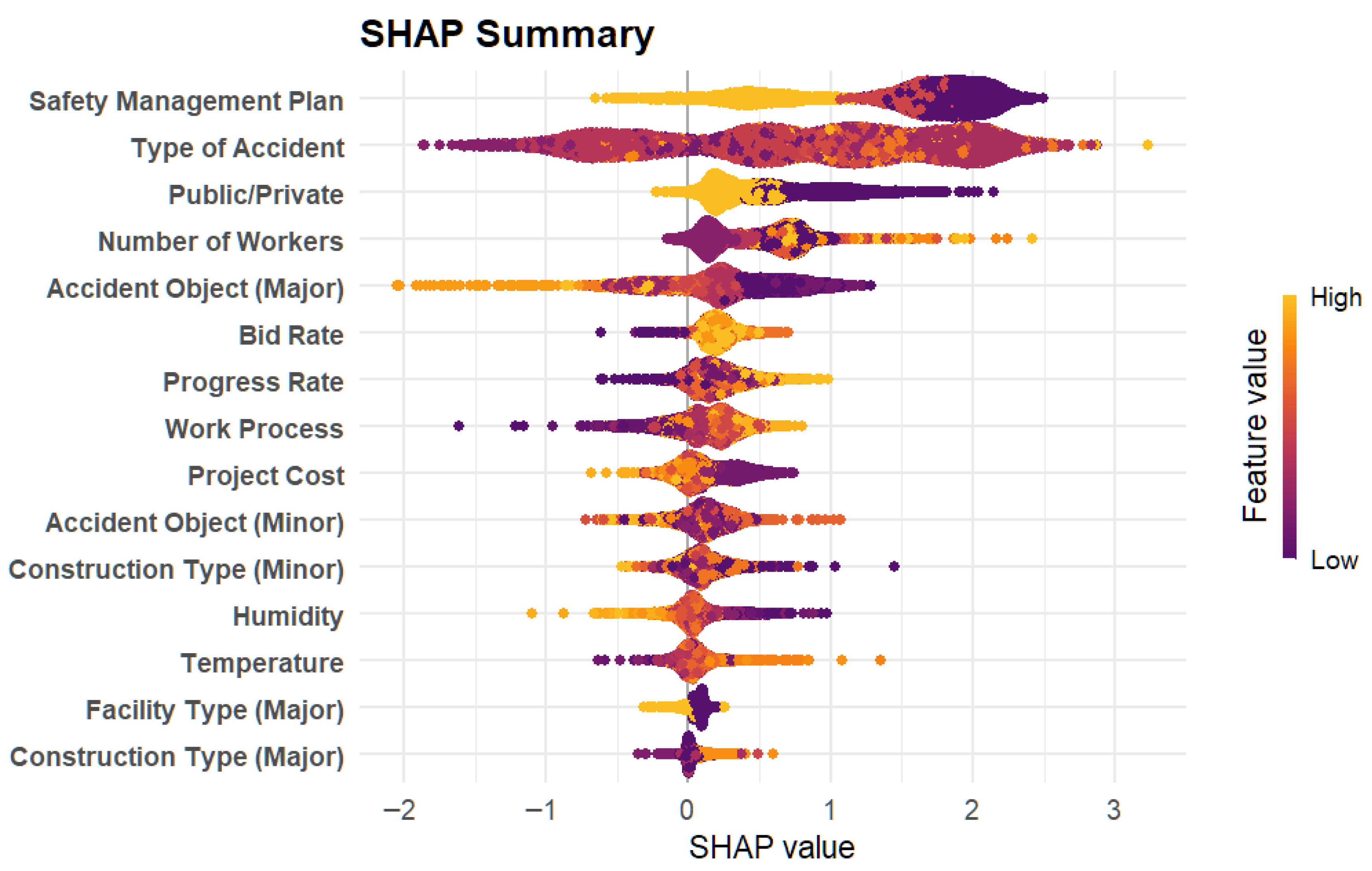

4.4. SHAP-Based Interpretation

4.5. Interpretation of Variables

4.5.1. Safety Management Plan

4.5.2. Type of Accident

4.5.3. Accident Object

4.5.4. Integrated Discussion

5. Discussion

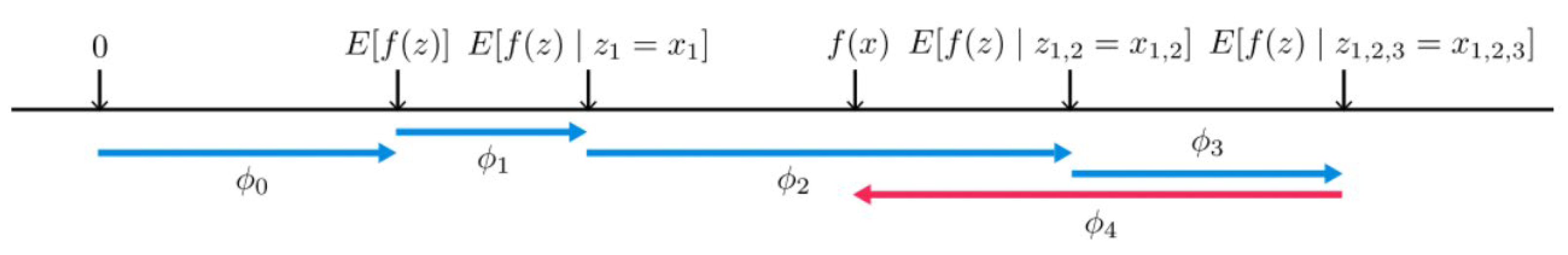

5.1. Scenario-Based Evaluation and Interpretation

5.2. Variable Importance and SHAP Interpretation

5.2.1. Scenario Design

5.2.2. Scenario-Based Interpretation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ADASYN | Adaptive synthetic sampling |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CSI | Construction Safety Management Integrated Information system |

| DL | Deep learning |

| GBDT | Gradient boosting decision tree |

| HFACS | Human Factors Analysis and Classification System |

| KISTEC | Korea Infrastructure and Technology Corporation |

| ML | Machine learning |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SHAP | Shapley additive explanations |

| SMOTE | Synthetic minority oversampling technique |

| XAI | Explainable artificial intelligence |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

References

- Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA). Annual Report on Occupational Accidents and Fatalities in Korea; KOSHA: Ulsan, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Teizer, J. Real-time resource location data collection and visualization technology for construction safety and activity monitoring applications. Autom. Constr. 2013, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.G.; Lunt, C.C.; Pew, T.; Warr, R.L. Using complementary intersection and segment analyses to identify crash hot spots. Saf. Sci. 2023, 163, 106121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Rowlinson, S. Development of a classification framework for construction personnel’s safety behavior based on machine learning. Buildings 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortey, L.; Edwards, D.J.; Roberts, C.; Rille, I. Hidden in plain sight: A data-driven approach to safety risk management for highway traffic officers. Buildings 2024, 14, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Park, J.; Park, H. Enhancing safety of construction workers in Korea: An integrated text mining and machine learning framework for predicting accident types. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2024, 31, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Na, Y.; Han, B. Assessment of risk priorities by cause of construction safety accidents: A case study of falling accidents in South Korea. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, H.; Geng, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Analysis of the causes of falling accidents on building construction sites in China based on the HFACS model. Buildings 2025, 15, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; García de Soto, B. Cyber risk assessment framework for the construction industry using machine learning techniques. Buildings 2024, 14, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-N.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, M.-J. Analysis of building construction jobsite accident scenarios based on big data association analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Infrastructure and Technology Corporation (KISTEC). Construction Safety Management Integrated Information (CSI) System Overview; KISTEC: Jinju, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Um, K.S. An Analysis on Fall Accidents at the Apartment Construction Site by Making Up Questionaires for Employee. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Son, C.B.; Kim, K.Y.; Lee, J.Y. A study on the influence of climate factors on construction accidents. J. Korean Soc. Saf. 2005, 20, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Jeong, J.; Kumi, L.; Mun, H. Analysis of the effect of outdoor thermal comfort on construction accidents by subcontractor types. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Garcia, E.A.; Li, S.A. ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), Hong Kong, China, 1–8 June 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, W.-Y.; Mao, B.-H.; Borderline, S. Borderline-SMOTE: A new over-sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Hefei, China, 23–26 August 2005; Huang, D.-S., Zhang, X.-P., Huang, G.-B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Garcia, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for learning from imbalanced data: Progress and challenges, marking the 15-year anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. A survey of predictive modeling on imbalanced domains. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 49, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błazik-Borowa, E.; Geryło, R.; Wielgos, P. The probability of a scaffolding failure on a construction site. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Chang, T.; Chi, S. Developing an integrated construction safety management system for accident prevention. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40, 04024051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning, 2nd ed.; Leanpub: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Type | Elements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public/Private | Categorical | 2 | |

| Facility Type (Major) | Categorical | 4 | |

| Construction Type | Major | Categorical | 7 |

| Minor | Categorical | 39 | |

| Work Process | Categorical | 41 | |

| Project Cost | Categorical | 18 | |

| Progress Rate | Categorical | 10 | |

| Bid Rate | Categorical | 8 | |

| Number of Workers | Categorical | 6 | |

| Variable | Type | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Numeric | −16~38 |

| Humidity | Numeric | 0~100 |

| Variable | Type | Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Management Plan | Categorical | 3 |

| Type of Accident (Human) | Categorical | 16 |

| Accident Object (Major) | Categorical | 9 |

| Accident Object (Minor) | Categorical | 117 |

| Presence of Fatalities and Injuries | Binary | 2 |

| Parameter | Value | Tuning | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| learning-rate | 0.05 | 0.01 | Learning rate |

| num-leaves | 31 | 64 | Number of leaf nodes |

| feature-fraction | 0.9 | 0.8 | Proportion of features used per iteration |

| bagging-fraction | 0.8 | 0.8 | Proportion of samples used per iteration |

| min_data_in_leaf | 10 | 10 | Minimum number of data per leaf |

| metric | AUC | AUC | Evaluation metric |

| Method | AUC | F1-Score | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMOTE | 0.879 | 0.877 | 0.989 | 0.788 |

| Borderline-SMOTE | 0.875 | 0.855 | 0.988 | 0.753 |

| ADASYN | 0.879 | 0.905 | 0.987 | 0.836 |

| Method | AUC | F1-Score | Recall | Precision | Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.687 | 0.887 | 0.817 | 0.969 | 0.649 |

| Random Forest | 0.843 | 0.901 | 0.831 | 0.982 | 0.769 |

| XGBoost | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.805 | 0.989 | 0.814 |

| LightGBM | 0.879 | 0.905 | 0.836 | 0.987 | 0.806 |

| Scenario | Ownership/ Plan Condition | Predicted Output f(x) | Dominant SHAP Contributors | Interpretation Summary | Final Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Private—Other regulated facility—Fall | +0.64 | Safety Plan (+), Type of Accident (−), Project Cost (−) | Private site without plan → partial mitigation; risk remains high. | Fatal |

| S2 | Private—Type 1/2 facility—Fall | +0.89 | Safety Plan (+), Work Process (+), Accident Object (−) | Formal plan increases injury tendency. | Fatal |

| S3 | Private—Non-regulated facility—Fall | −0.27 | Type of Accident (–), Project Cost (−), Work Process (−) | Lack of plan and low resources → fatal outcome likely. | Fatal |

| S4 | Public—Non-regulated facility—Fall | +0.89 | Public/Private (+), Safety Plan (+), Type of Accident (−) | Public oversight partially offsets missing plan. | Fatal |

| S5 | Public—Type 1/2 facility—Fall | +2.69 | Safety Plan (+), Public/Private (+), Work Process (+) | Full plan + public supervision → lowest fatality risk. | Injury |

| S6 | Public—Other regulated facility—Fall | +2.83 | Public/Private (+), Type of Accident (−), Safety Plan (+) | Public project mitigates fatal risk despite weak plan. | Injury |

| Category | Major Variables | SHAP Direction | Role Type | Interpretation Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Drivers | Type of Accident Accident Object (Major) Work Process | Negative (−) → Fatal direction | Physical/ Operational factors | These variables drive the model output toward the fatal direction. High negative SHAP values indicate strong contributions to fatal outcomes, representing direct causes such as fall-from-height or collapse-related processes. |

| Mitigating Factors | Safety Management Plan Public/Private | Positive (+) → injury direction | Managerial/ Institutional factors | Management-related variables reduce the predicted fatality risk. The existence of a safety plan and public-sector supervision acts as a mitigating elements that shift predictions toward injury outcomes. |

| Contextual/Interactive Factors | Project Cost Progress Rate Number of Workers | Mainly negative (−), partly positive (+) depending on conditions | Site-operational factors | Operational characteristics such as project scale, progress rate, and workforce size show consistent directional effects and interact with work process variables, influencing the severity level of predicted accidents. |

| Environmental Factors | Temperature Humidity | Weak impact | Weak impact |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K.-n.; Cho, D.-g.; Lee, M.-j. A Machine Learning Approach for Factor Analysis and Scenario-Based Prediction of Construction Accidents. Buildings 2025, 15, 4343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234343

Kim K-n, Cho D-g, Lee M-j. A Machine Learning Approach for Factor Analysis and Scenario-Based Prediction of Construction Accidents. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234343

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ki-nam, Dae-gu Cho, and Min-jae Lee. 2025. "A Machine Learning Approach for Factor Analysis and Scenario-Based Prediction of Construction Accidents" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234343

APA StyleKim, K.-n., Cho, D.-g., & Lee, M.-j. (2025). A Machine Learning Approach for Factor Analysis and Scenario-Based Prediction of Construction Accidents. Buildings, 15(23), 4343. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234343