Influence of Bolt Arrangement on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-Large Cross-Section Shield Tunnels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Simulation

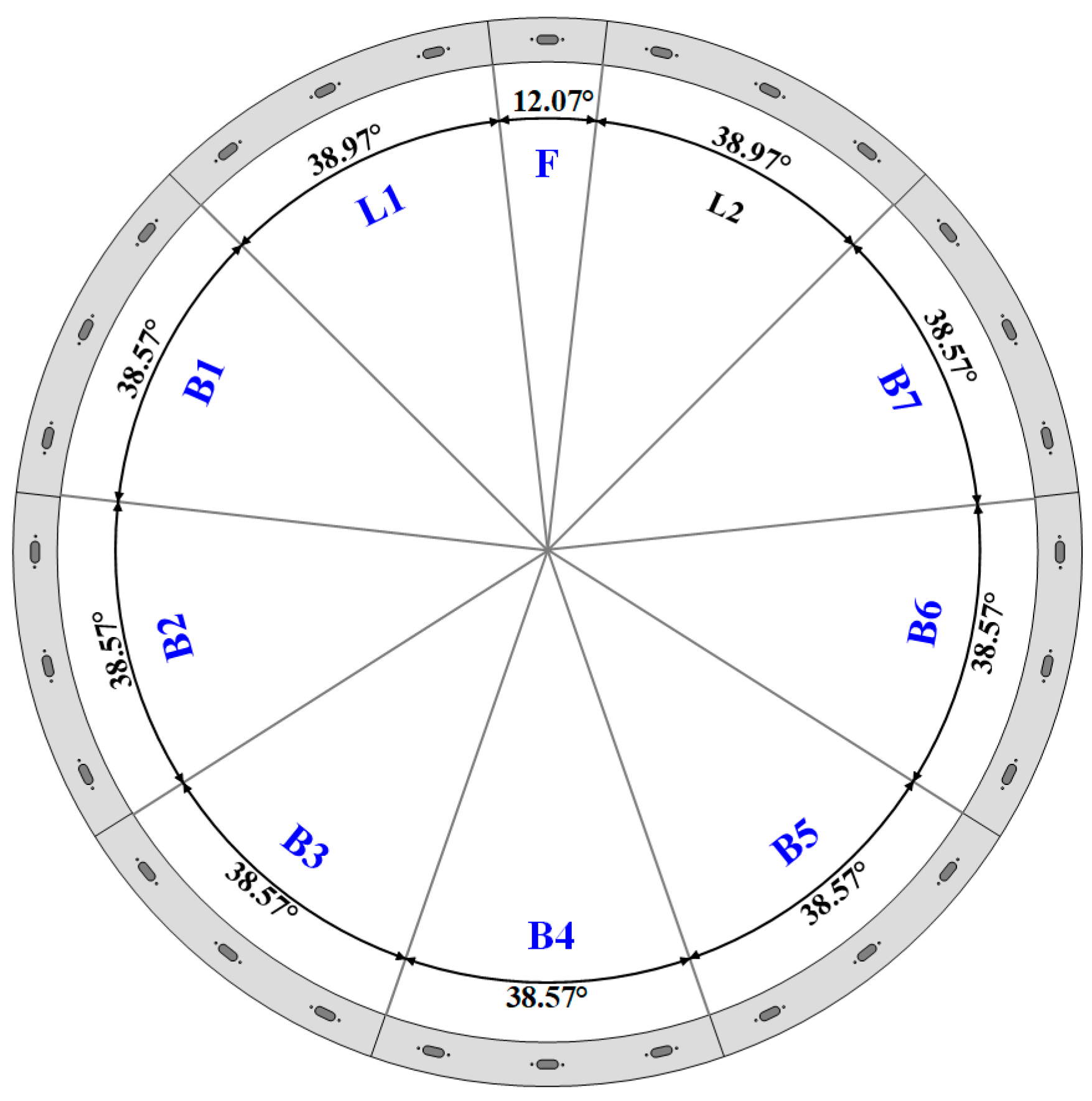

2.1. Project Background

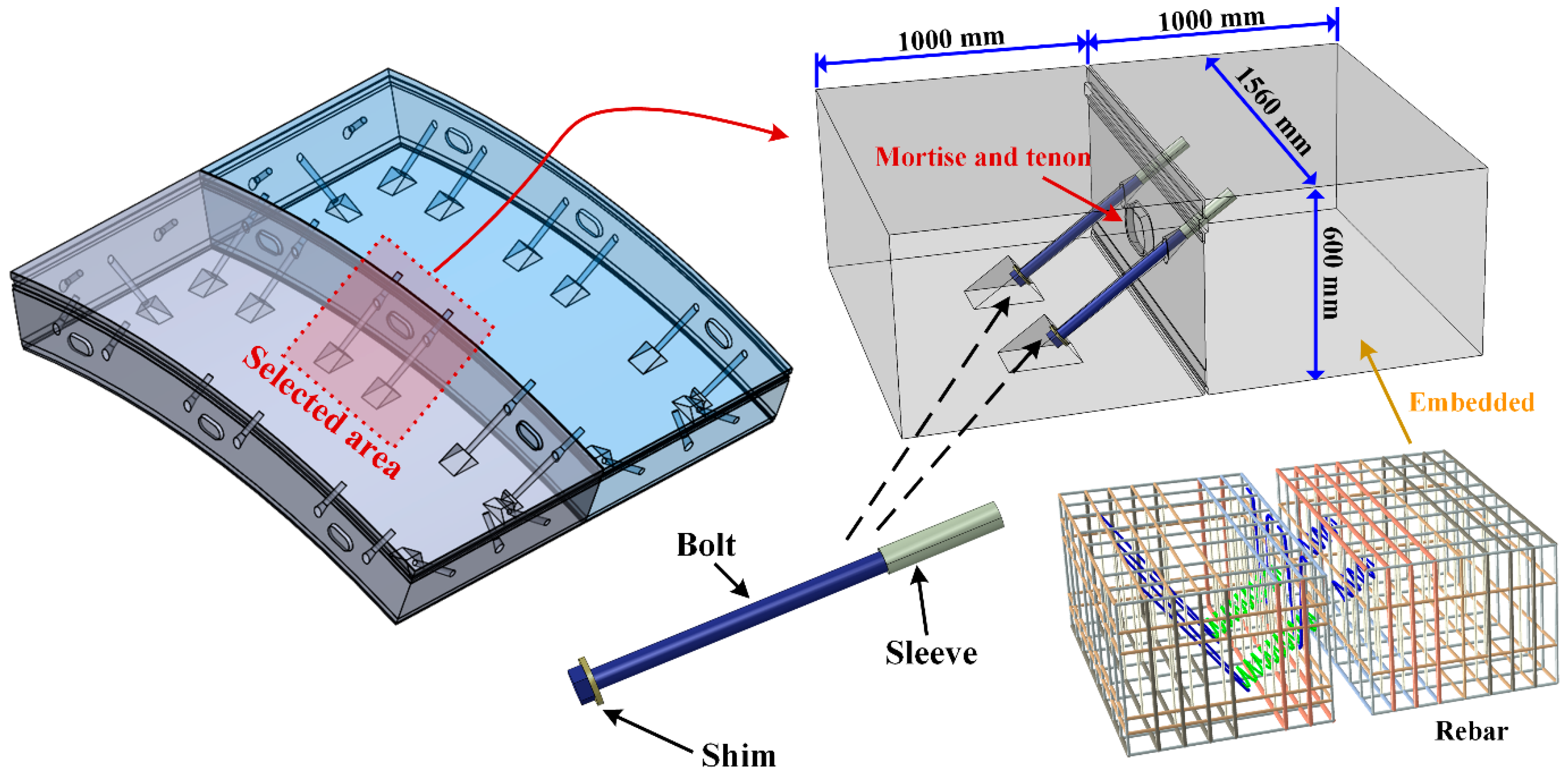

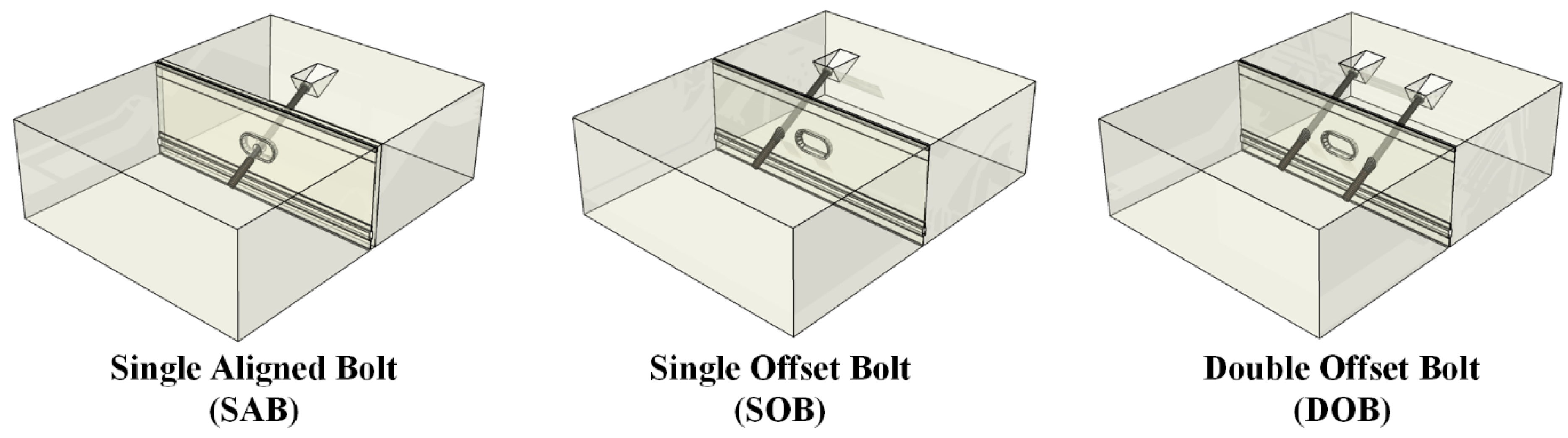

2.2. Overview of the Numerical Model

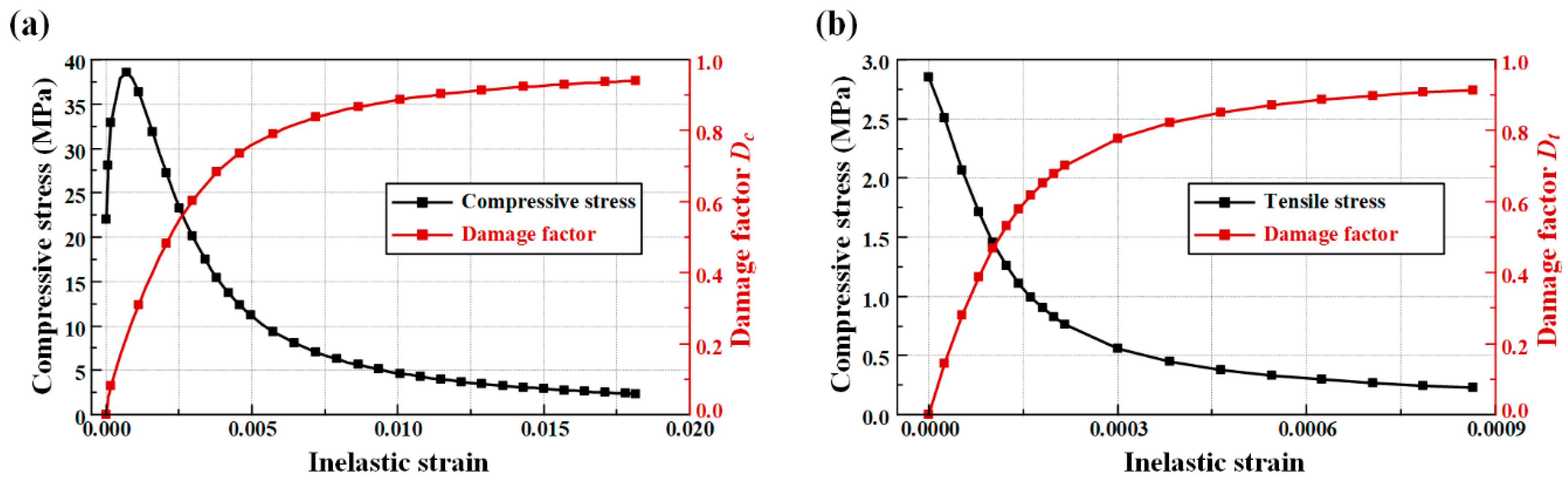

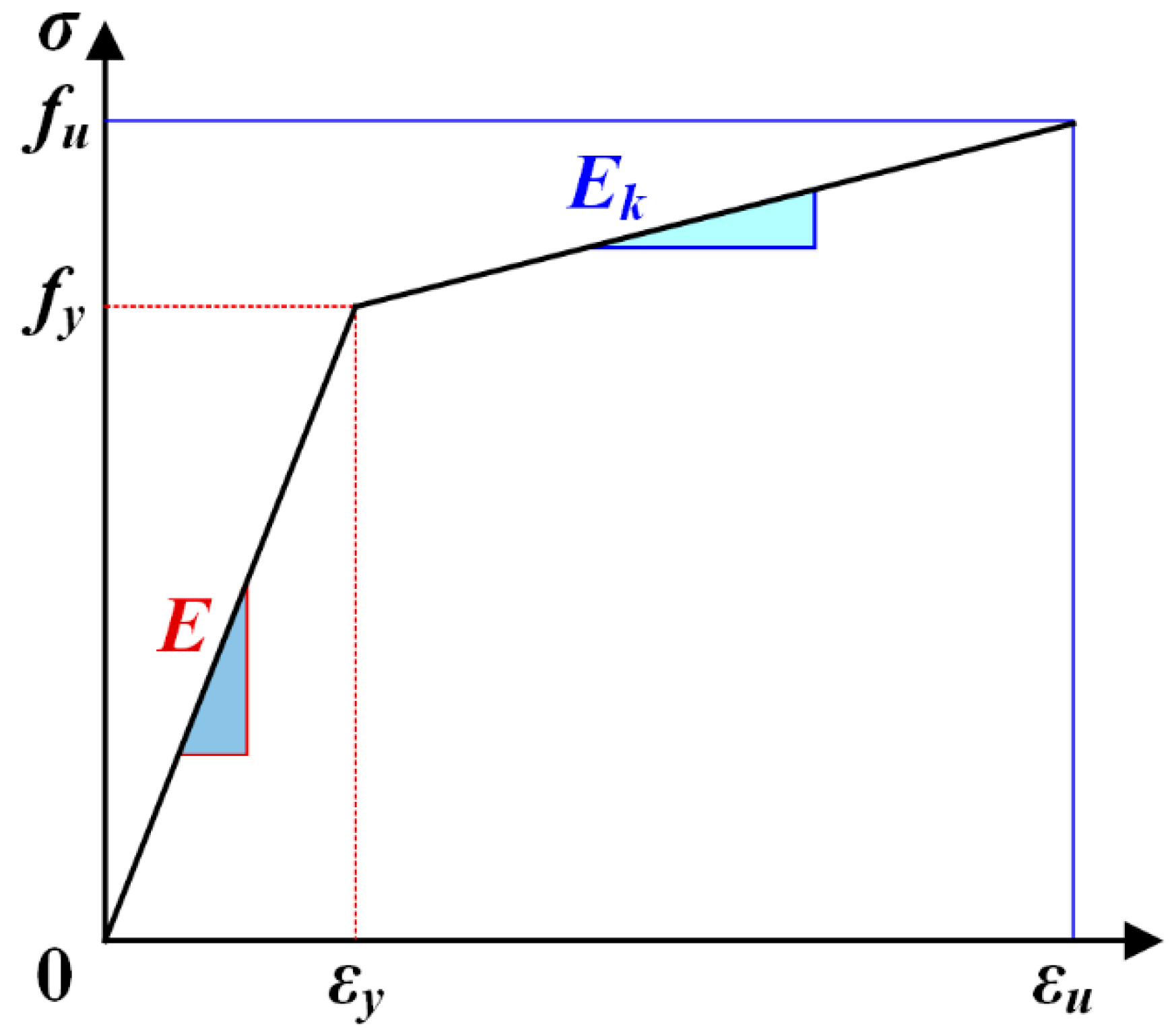

2.3. Material Properties

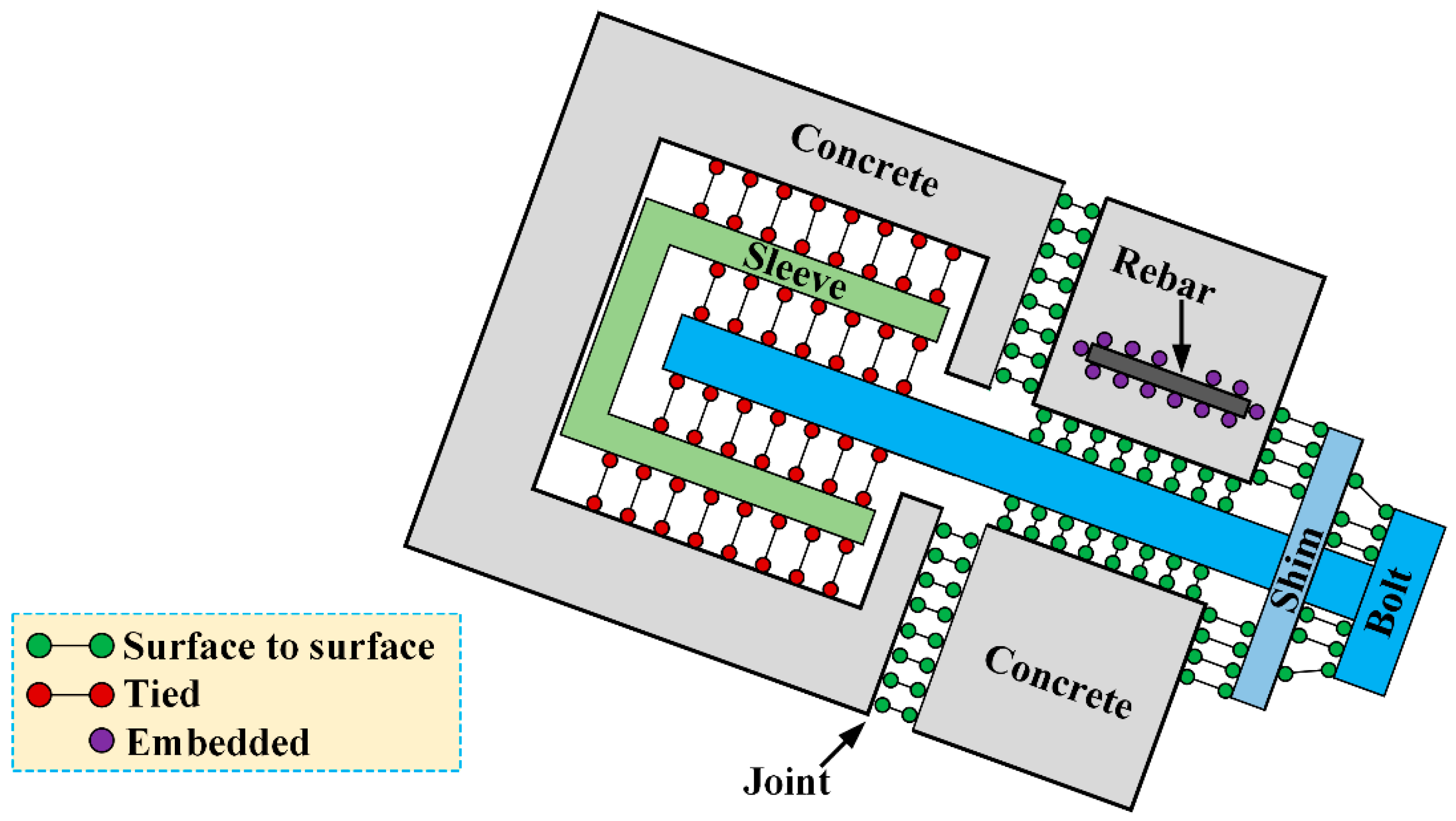

2.4. Interactions

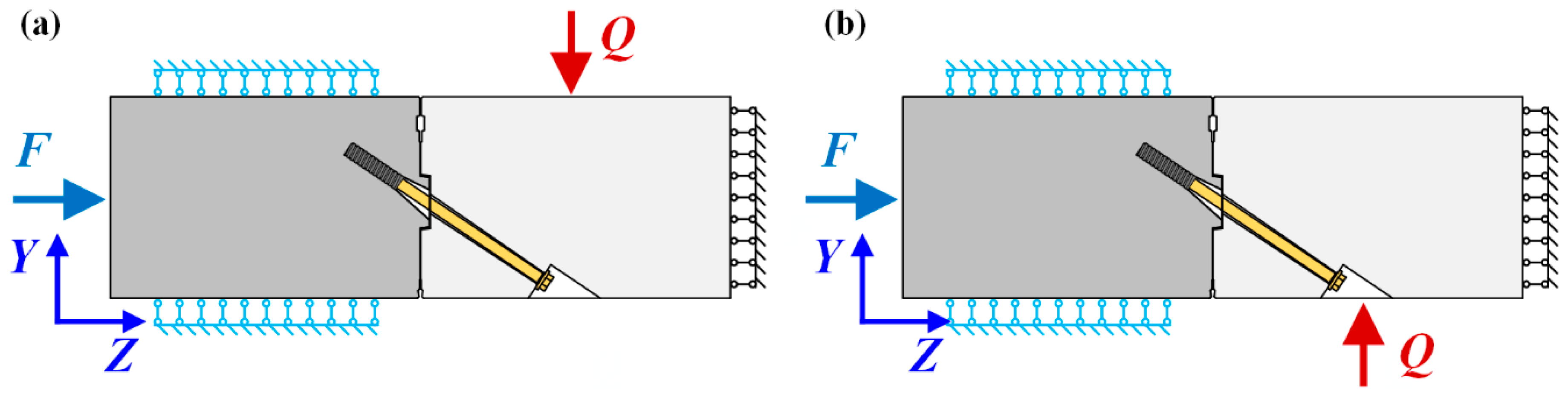

2.5. Boundary and Loading Conditions

3. Result Analysis

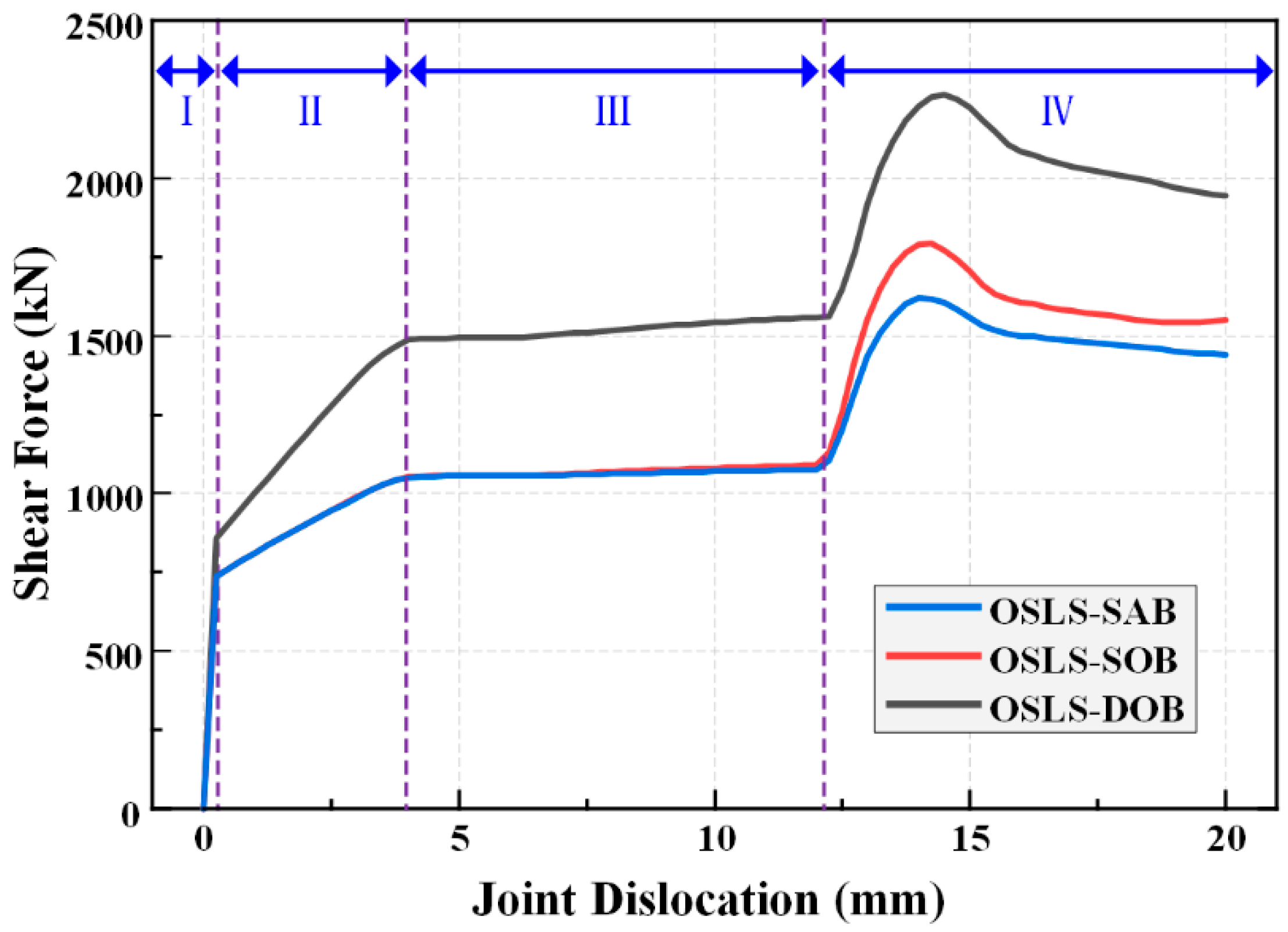

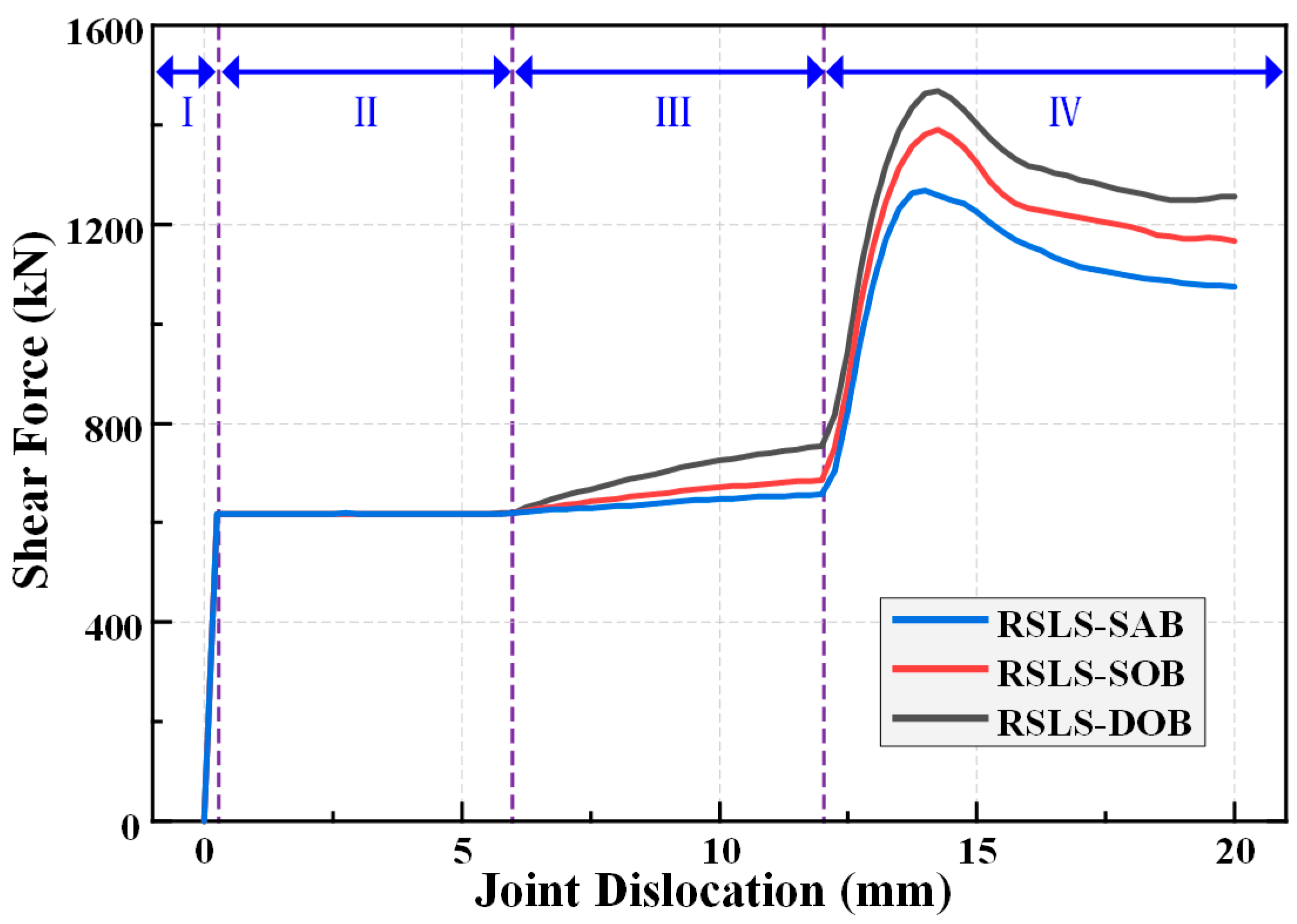

3.1. Correlation Between Shear Force and Joint Dislocation

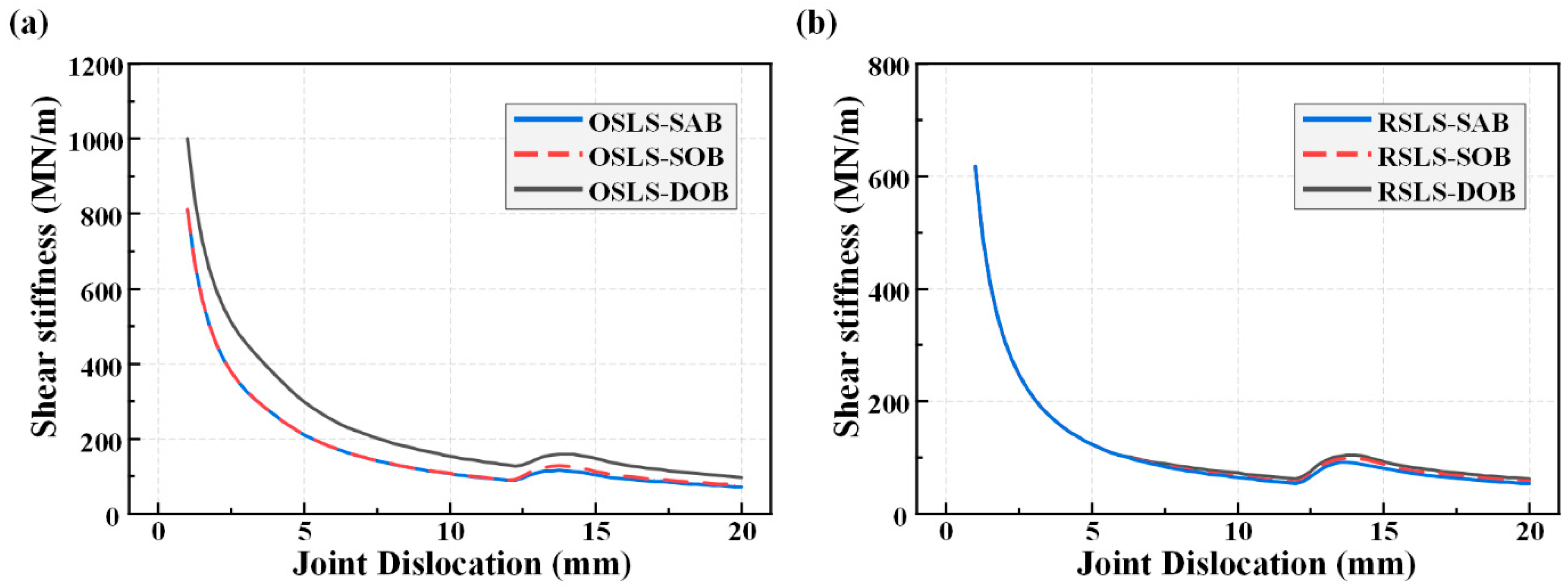

3.2. Shear Stiffness Analysis

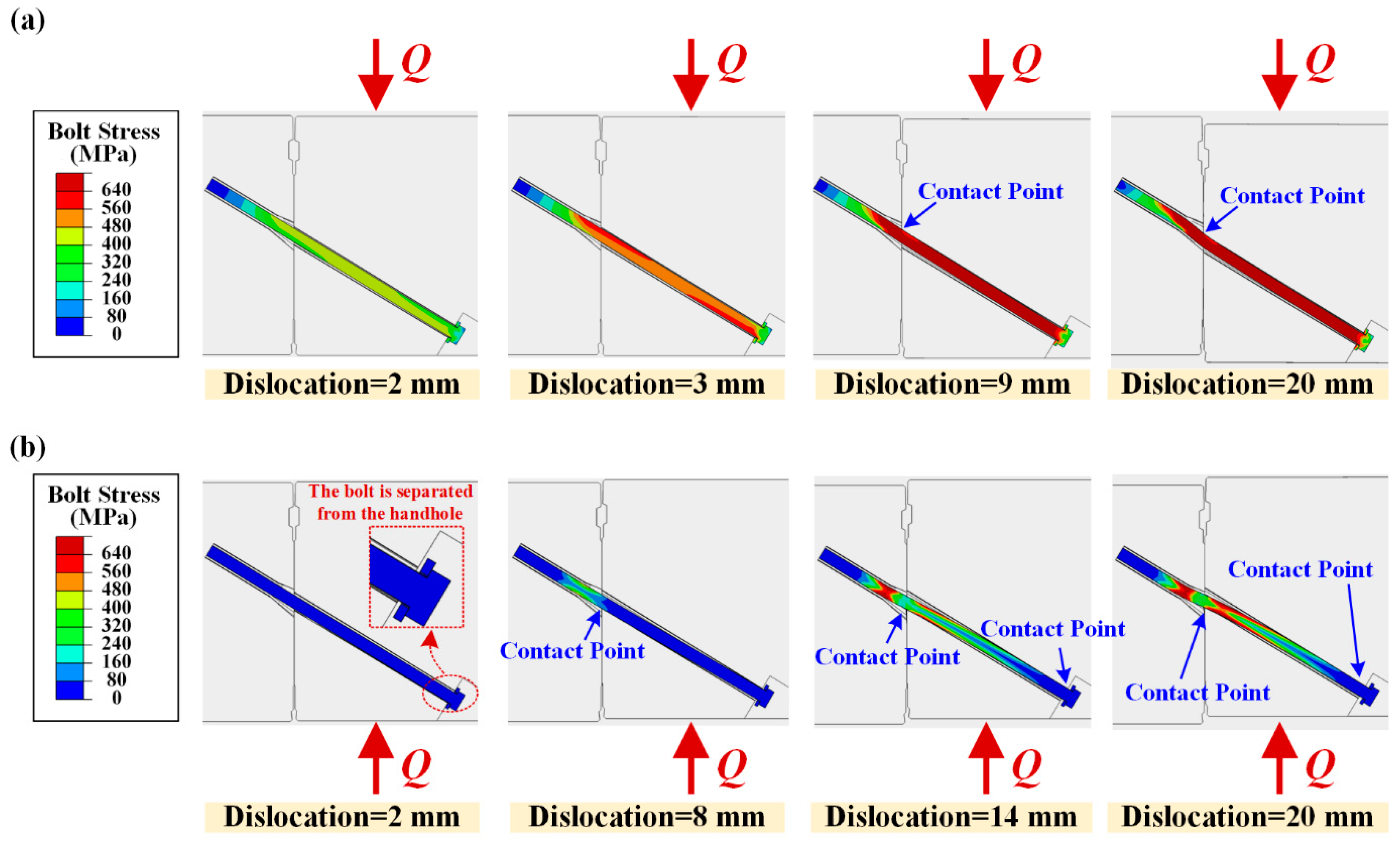

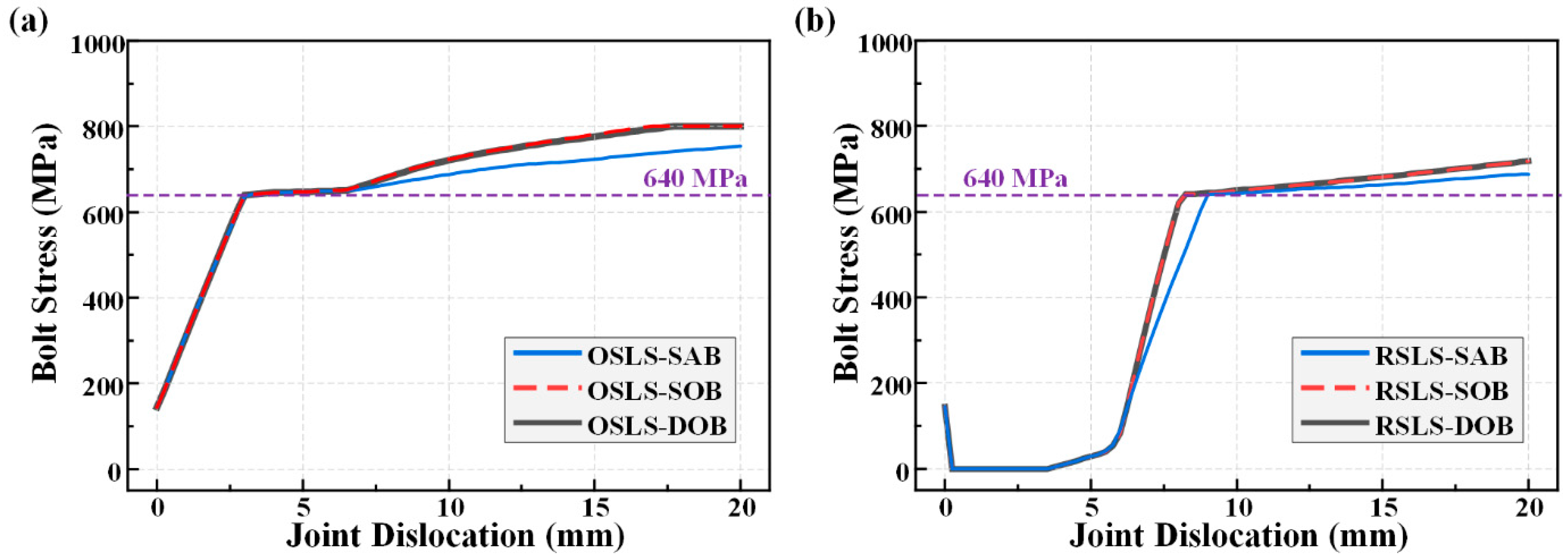

3.3. Bolt Stress

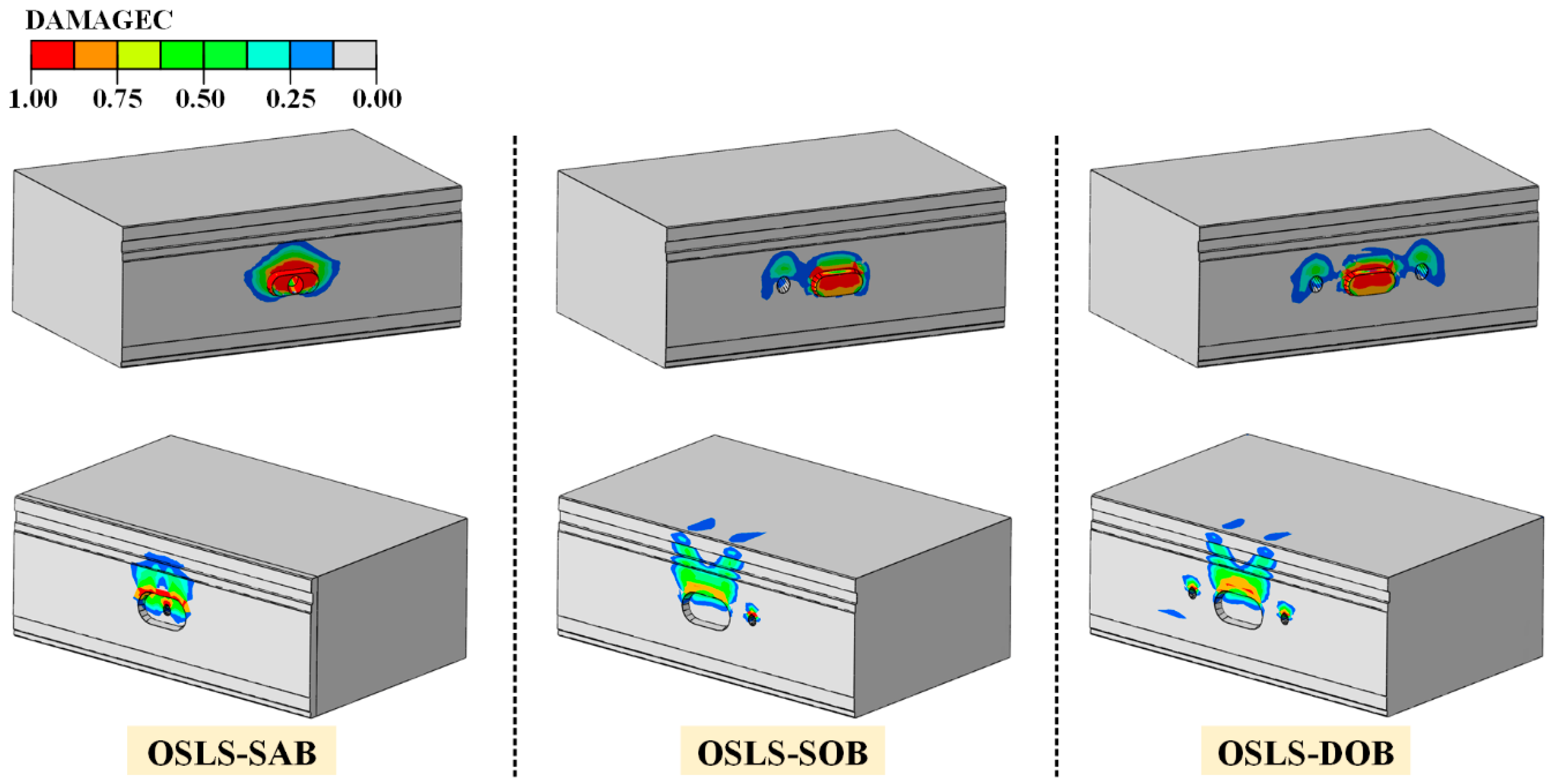

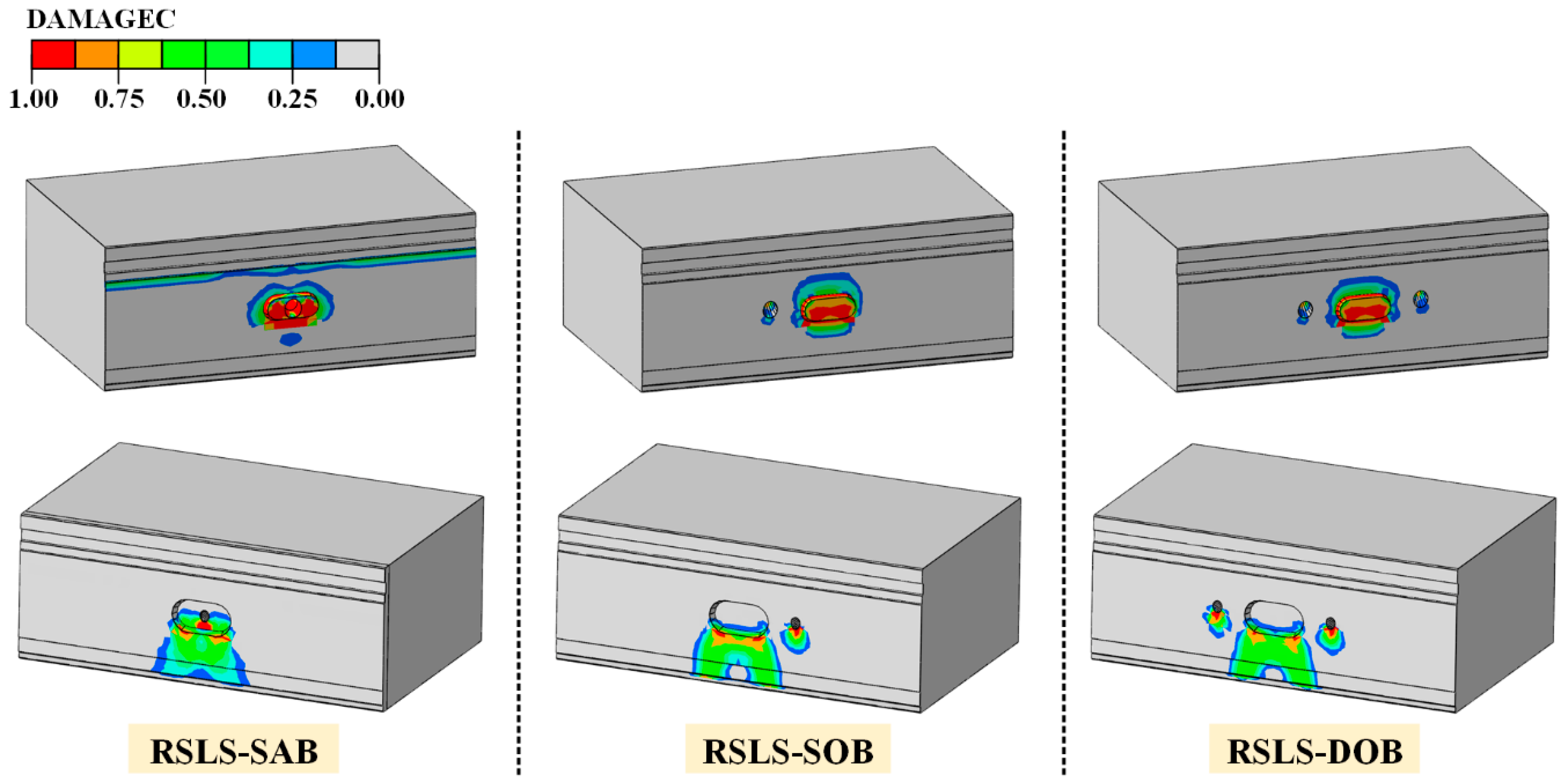

3.4. Failure Characteristics of Joints

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- When subjected to consistent loading patterns, joints with different bolt arrangements undergo identical force stages with corresponding dislocations. Under OSLS, the joints experience static friction, slow sliding, rapid sliding, and mortise-tenon contact as dislocation increases. Under RSLS, the stages are static friction, rapid sliding, bolt bearing, and mortise-tenon contact.

- (2)

- Under OSLS, bolts provide significant load-bearing capacity, resulting in DOB having superior shear performance compared to SAB and SOB. Due to the weakening of mortises by bolt holes in SAB, its shear resistance in the later deformation stage is weaker than SOB. Under RSLS, bolts exhibit extraction, and the shear-dislocation curves of the three configurations are similar in the early stages, with only minor differences as deformation progresses.

- (3)

- DOB demonstrates clearly higher shear performance than SAB and SOB under OSLS, but this difference is less pronounced under RSLS. The ultimate capacities of SAB and SOB are 71.5% and 79.1% of DOB under OSLS and 86.2% and 94.6% of DOB under RSLS.

- (4)

- The mechanical behavior of bolts is largely consistent across different arrangements. For the same dislocation, the force states, stress distributions, and maximum stresses of bolts in SAB, SOB, and DOB show minimal differences.

- (5)

- In SAB, bolt holes passing through the mortises weaken the structure, leading to further damage due to contact failure between bolts and bolt holes. As a result, SAB joints suffer more severe shear failure, whereas the failure modes of SOB and DOB joints are nearly identical and less detrimental.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, X. Mechanical Responses in the Construction Process of Super-Large Cross-Section Tunnel: A Case Study of Gongbei Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-N.; Huang, R.-Q.; Sun, W.-J.; Shen, S.-L.; Xu, Y.-S.; Liu, Y.-B.; Du, S.-J. Leaking Behavior of Shield Tunnels under the Huangpu River of Shanghai with Induced Hazards. Nat. Hazards 2014, 70, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Feng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, L. Investigation on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-large Cross-section Shield Tunnels. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 4978–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, B.-L.; Zhang, D.-M.; Huang, Z.-K.; Zheng, F.-Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, W. Ontology-Driven Knowledge Graph for Decision-Making in Resilience Enhancement of Underground Structures: Framework and Application. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 163, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Zhong, Y. Shearing Behavior of Circumferential Joints with Oblique Bolts in Large Diameter Shield Tunnel. China J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, L.; Zhang, J.; Feng, K.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; He, C. Experimental Study on Inter-Ring Joint Shearing Characteristics of Gas Transmission Shield Tunnel with Bent Bolt and Tenon. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 130, 104732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Deformation Behavior of Shield Segment Joint Controlled by Bolt and Positioning Tenon. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 11241–11251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, Q.; Li, W.; Su, L.; Sun, M.; Yao, C. Failure Analysis of a New-Type Shield Tunnel Based on Distributed Optical Fiber Sensing Technology. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 142, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Feng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, X.; Qi, M.; He, C.; Xiao, M. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the Shear Behavior and Damage Mechanism of Segmental Joint under Compression-Shear Load. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 139, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Feng, K.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Lin, G.; He, C. Experimental Study on the Compression-Shear Performance of a New-Type Circumferential Joint of Shield Tunnel. Undergr. Space 2024, 14, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Oreste, P.; Ye, F. The Influence of the Nonlinear Behaviour of Connecting Bolts on the Shear Stiffness of Circular Joints in a Tunnel Segmental Lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 146, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Q. Study on the Applicability of Load Calculation Method for Large-Diameter Shield Tunnel in Argillaceous Sandstone Stratum under High Water Pressure. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 5401–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Feng, K.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Su, A.; Guo, W. Failure Mechanism of Underwater Shield Tunnel: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 137, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, C.; Feng, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, M. Investigation on the Mechanical Behavior of Segment Lining Structure Based on Three-Dimensional Refined Numerical Model. Structures 2023, 58, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 3098.1-2010; Mechanical Properties of Fasteners—Bolts, Screws and Studs. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Taerwe, L. Comparison of the Structural Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Tunnel Segments with Steel Fiber and Synthetic Fiber Addition. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 103, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Chen, X.; Jin, Y.; Qiao, Y. Flexural Behavior of Segmental Joint Containing Double Rows of Bolts: Experiment and Simulation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 112, 103940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, C.; Wang, Z.; Lei, M.; Zhao, D.; Cao, C. Damage Mechanism Modelling of Shield Tunnel with Longitudinal Differential Deformation Based on Elastoplastic Damage Model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 113, 103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, C.; Gong, C.; Lei, M.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Cao, C. Investigation of Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Shield Tunnel Based on Concrete Damage Model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 125, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Sidoroff, F. Description of Anisotropic Damage Application to Elasticity. In Physical Non-Linearities in Structural Analysis; Hult, J., Lemaitre, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 237–244. ISBN 978-3-642-81584-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, K.; Xu, P.; He, C.; Zhang, H. Refined Three-dimensional Numerical Model for Segmental Joint and Its Application. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 1612–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.-L.; Ma, S.-K.; Zhang, J.-B.; Zhu, Q.-X. Study of the Mechanical Behaviour and Damage Characteristics of Three New Types of Joints for Fabricated Rectangular Tunnels Using a Numerical Approach. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 118, 104184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G. Finite Element Model to Predict Structural Response of Predamaged RC Beams Reinforced by Toughness-Improved UHPC under Unloading Status. Eng. Struct. 2021, 235, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ye, H.; Sun, L. Experimental Study on Seismic Behavior of T-shaped Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Columns. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 612–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K. Full-Scale Tests on Bending Behavior of Segmental Joints for Large Underwater Shield Tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 75, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete (Class C60) | 0.04 | 0.20 | —— | —— |

| Bolt (Grade 8.8) | 0.16 | 0.30 | 640 | 800 |

| Reinforcement (HPB300) | 210 | 0.30 | 300 | 400 |

| Reinforcement (HRB400) | 200 | 0.30 | 400 | 540 |

| Sleeve | 2 | 0.35 | —— | —— |

| Shim | 210 | 0.33 | —— | —— |

| Loading Condition | Ultimate Shear Load-Bearing Capacity (kN) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SAB | SOB | DOB | |

| OSLS | 1618.76 | 1791.83 | 2265.2 |

| RSLS | 1266.76 | 1389.51 | 1469.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Qiu, W.; Su, L.; Yang, S.; Xie, Y.; Wu, B.; Wu, L. Influence of Bolt Arrangement on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-Large Cross-Section Shield Tunnels. Buildings 2025, 15, 4322. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234322

Wang H, Qiu W, Su L, Yang S, Xie Y, Wu B, Wu L. Influence of Bolt Arrangement on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-Large Cross-Section Shield Tunnels. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4322. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234322

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haijun, Wei Qiu, Linjian Su, Shaoyi Yang, Yi Xie, Bohan Wu, and Luxiang Wu. 2025. "Influence of Bolt Arrangement on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-Large Cross-Section Shield Tunnels" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4322. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234322

APA StyleWang, H., Qiu, W., Su, L., Yang, S., Xie, Y., Wu, B., & Wu, L. (2025). Influence of Bolt Arrangement on the Shear Performance of Circumferential Joints of Segments in Super-Large Cross-Section Shield Tunnels. Buildings, 15(23), 4322. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234322