Orientational Metaphors of Megastructure Worship: Optimization Perspectives on Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Aim and Contribution

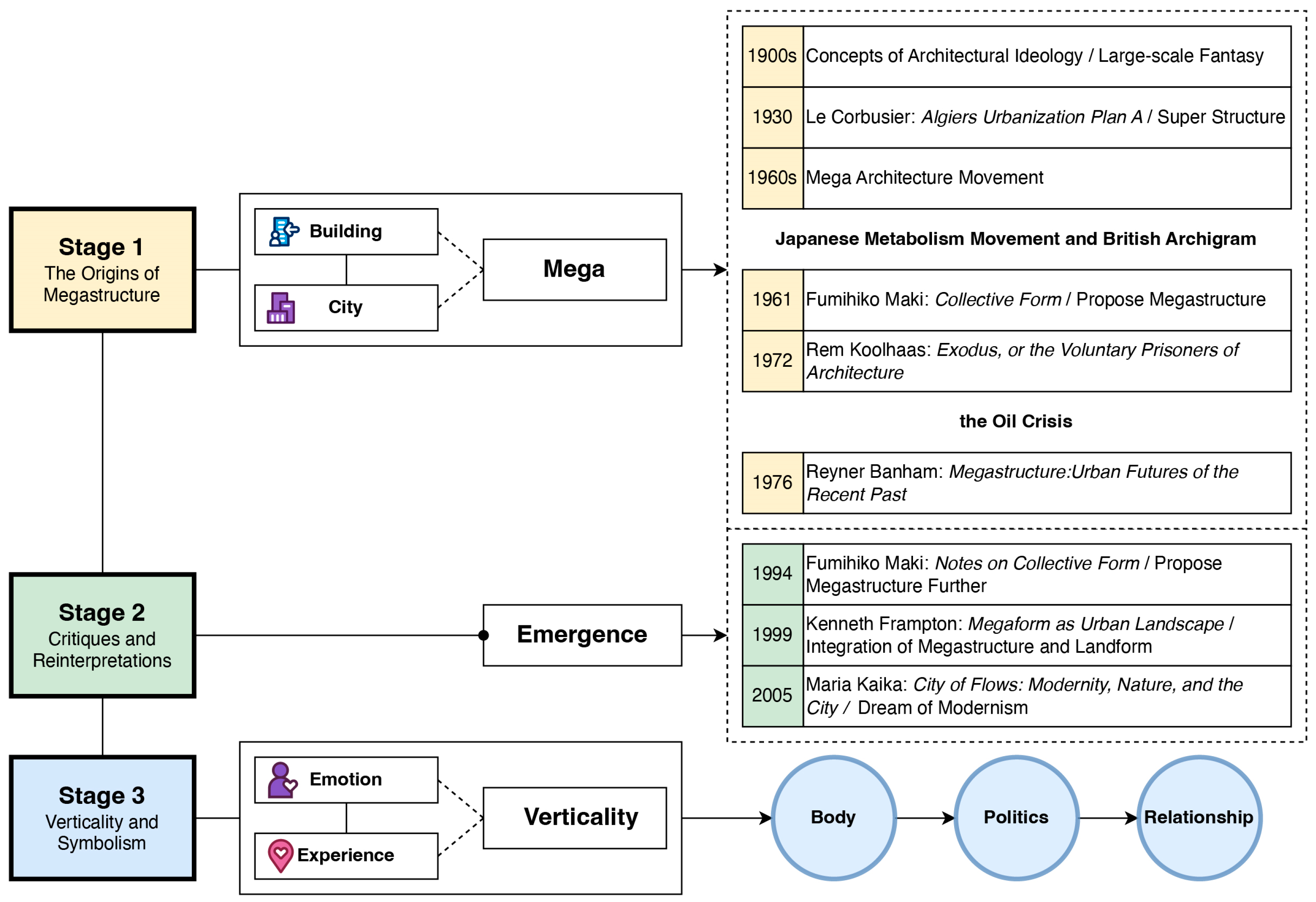

2. Literature Review: The Overview of Megastructure

2.1. The Origins of Megastructure

2.2. Critiques and Reinterpretations of Megastructures in the Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century

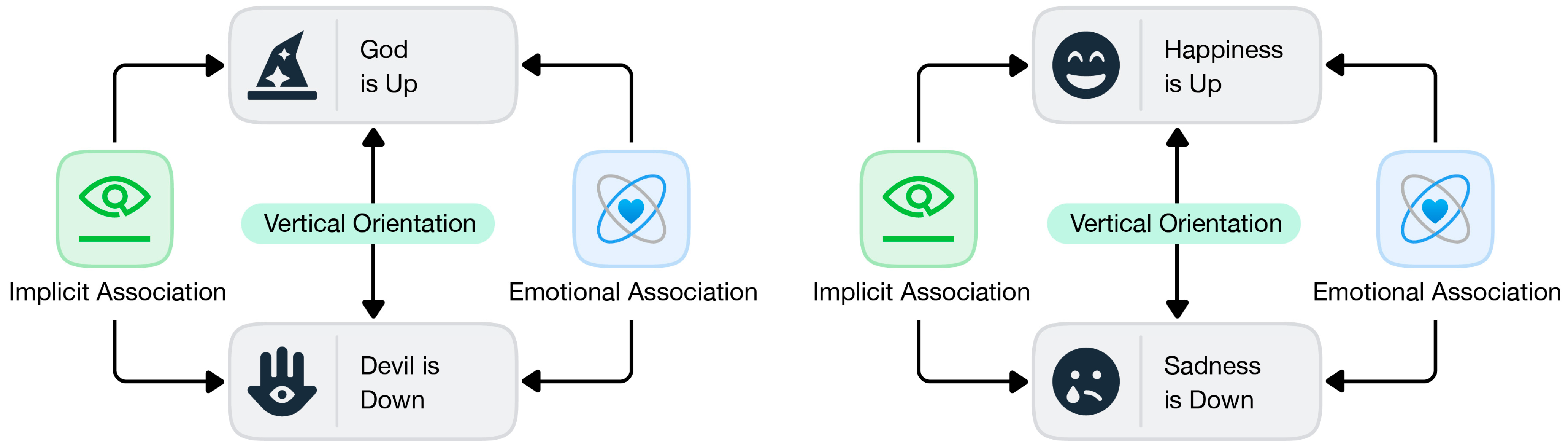

2.3. Verticality and Symbolism: Their Influence on Megastructures

- Megastructure and science fiction: The vertical stratification within their sci-fi cities served not only as a visual symbol of future imagination but also as an allegorical expression of class, power, technology, and spatial inequality in contemporary urban landscapes. Simultaneously, this fictional megastructure imagery influenced the architecture and planning of real cities, forming a bidirectional constructive relationship between “fiction” and “reality” [31];

- Megastructure, photography, and climbing: The style of visual representation shifted from a picturesque, detached landscape appreciation to a dynamic, embodied, immersive experience documentation. Natural mountain ranges (such as the Alps) and man-made megastructures (such as skyscrapers and the Eiffel Tower) were equated through climbing practices and photographic perspectives, forming the metaphor “the city is a mountain”. The modern body sought and constructed meaning in vertical space through technology, treating climbing as a performance for the camera. The value of megastructures relied on photographic visual dissemination [32];

- Megastructure and postwar thought: In post-World War II architectural education, two major schools of thought emerged—monoliths and mountains. Megastructure, rooted in systems thinking, emphasized architectural technical rationality, quantitative analysis, functional optimization, and universal typologies. The mountain emerged from phenomenology, emphasizing the sensory experience of architecture, the spirit of place, humanistic meaning, and handcrafted construction, pursuing an “authentic” existence connected to history and nature. Together, these divisions formed the complex terrain of postwar architectural thought, and the tension between them continued to shape architects’ ways of thinking to this day [33];

- Megastructure and human endeavor: Human activities—particularly within megastructures—attained the power to reshape the Earth’s surface. Man-made environments and natural landscapes converged in scale and form, giving rise to new, hybrid geological strata. This approach rejected the notion of architecture as discrete objects, emphasizing instead that buildings and landscapes formed a fluid, organic, and tension-filled network of relationships. Megastructures resonated with the scientific concept of the “critical zone”, focusing on the dynamic interconnections between rock, air, architecture, and atmosphere [34].

3. O-ACL Methodology: The New Construction Process from ACL to Orientational Metaphors

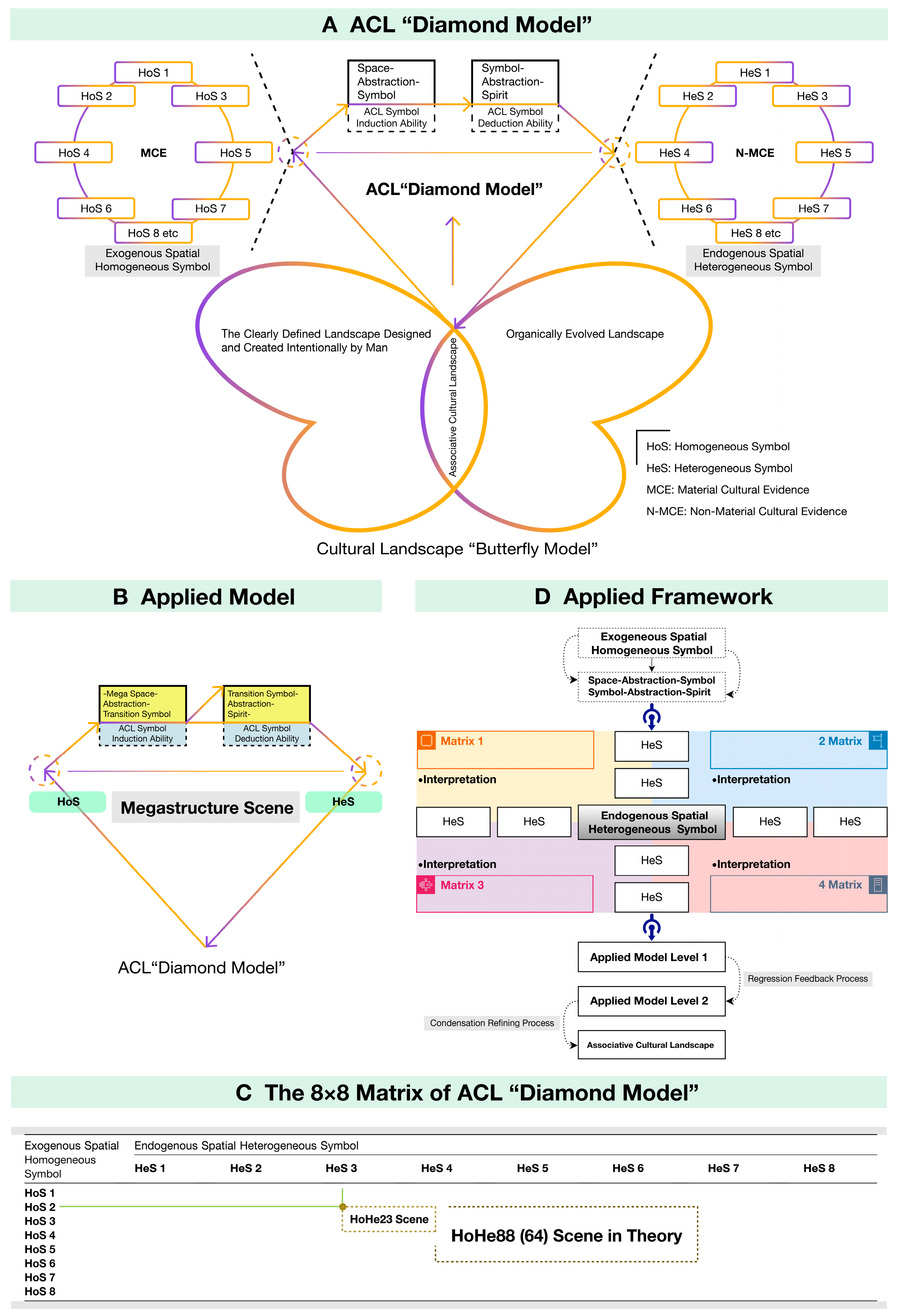

3.1. ACL Methodology

3.2. Explaining the Feasibility of Megastructure Worship Utilizing ACL Methodology

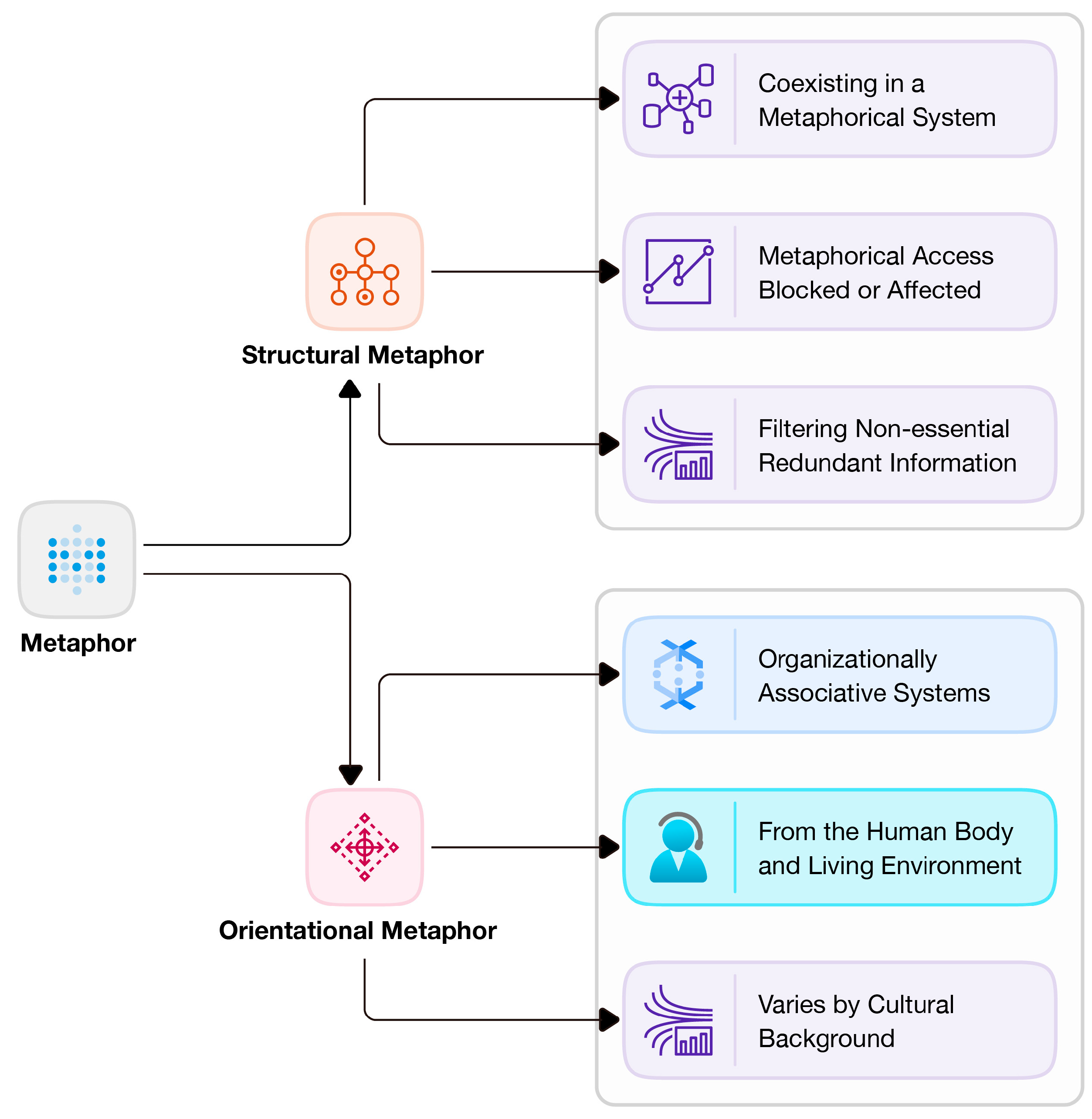

3.3. Optimization Based on ACL Methodology: Orientational Metaphors–Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology

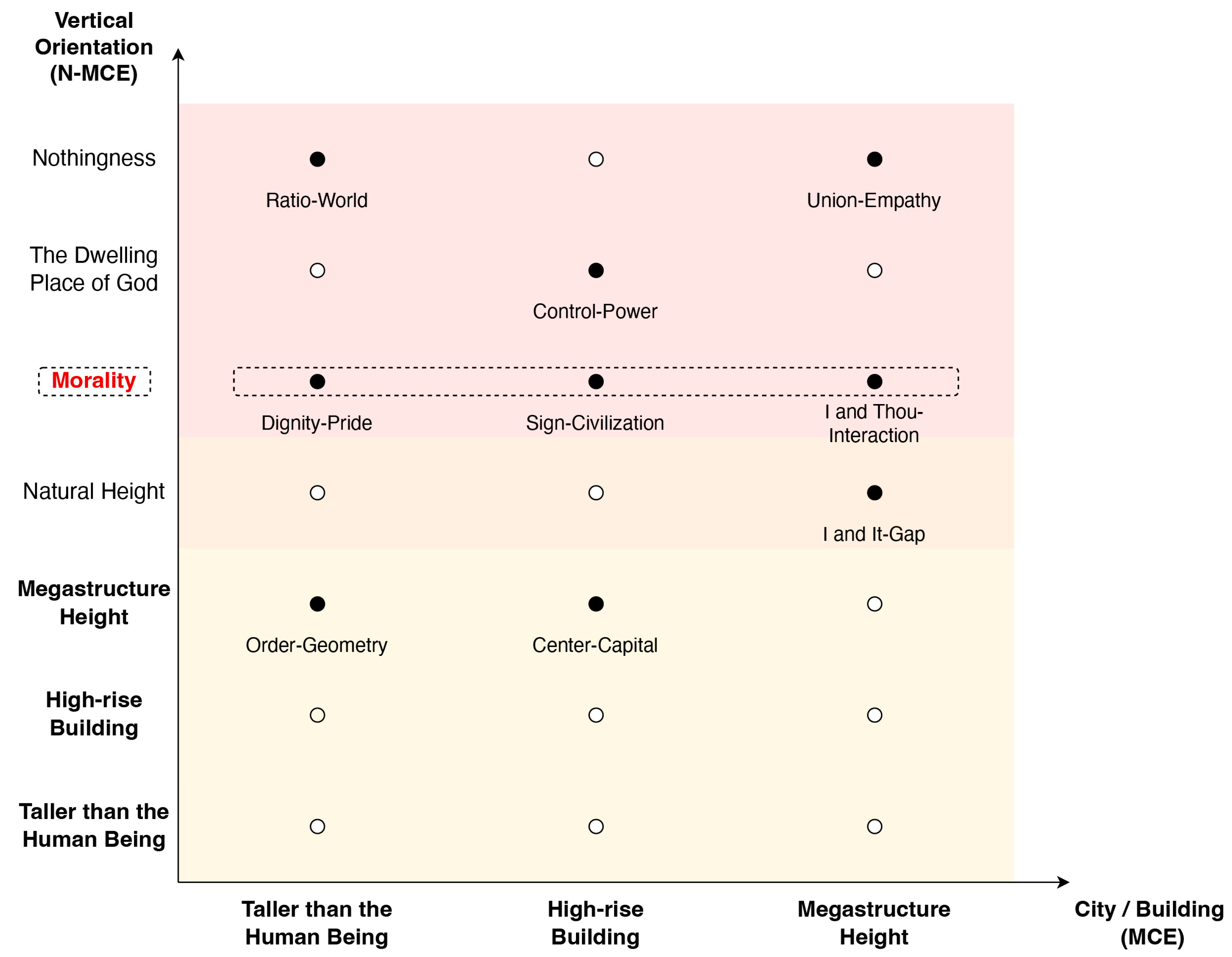

- O-ACL methodology is derived from ACL methodology, is a sub-division of the ACL methodology, and is a targeted methodology for the “verticality” of a specific domain: megastructure worship;

- The “verticality” of the megastructure corresponds to the vertical spatial orientation of the orientational metaphors. The “verticality” of the megastructure and the orientational metaphors are both related to “spiritual relevance”;

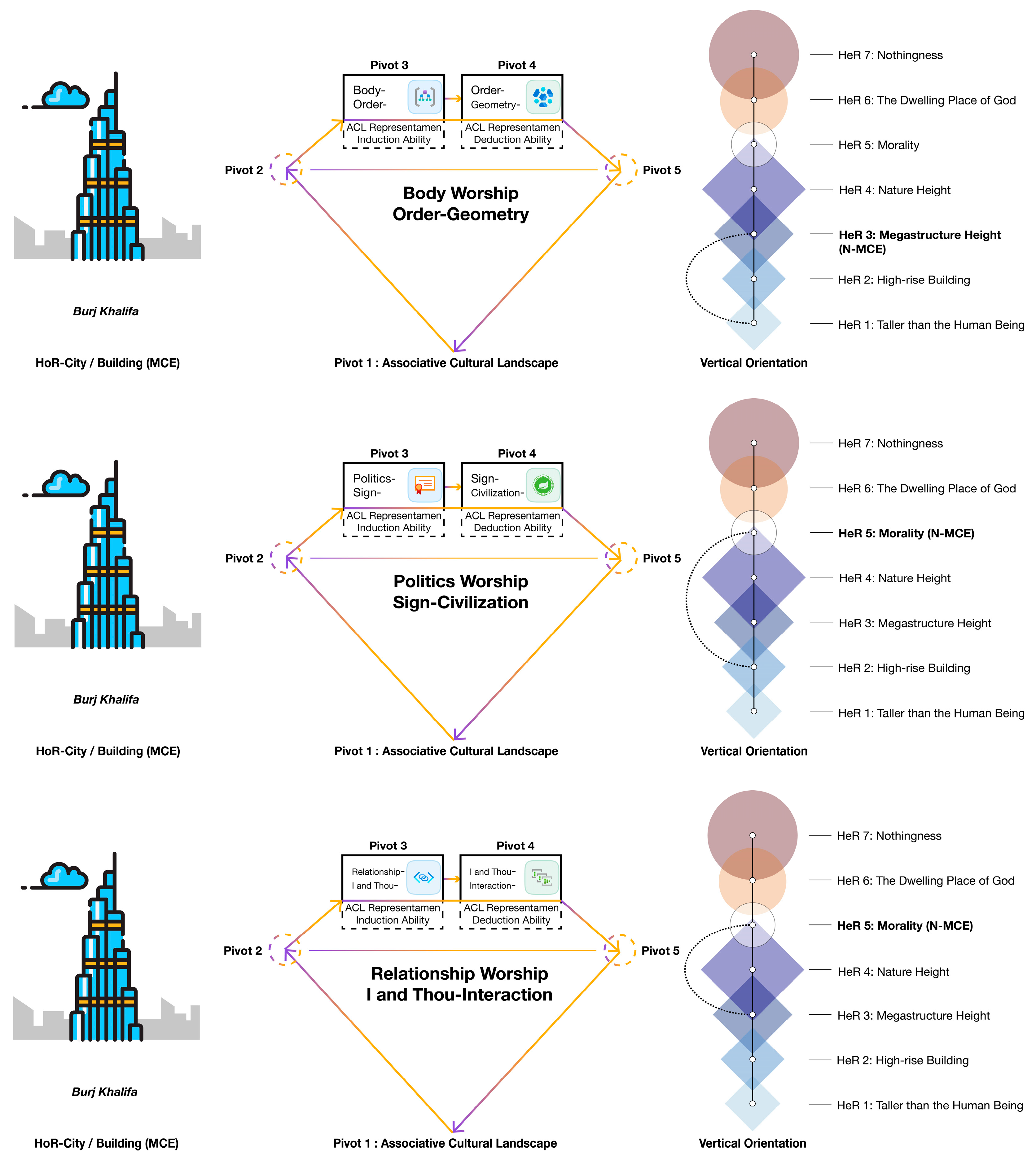

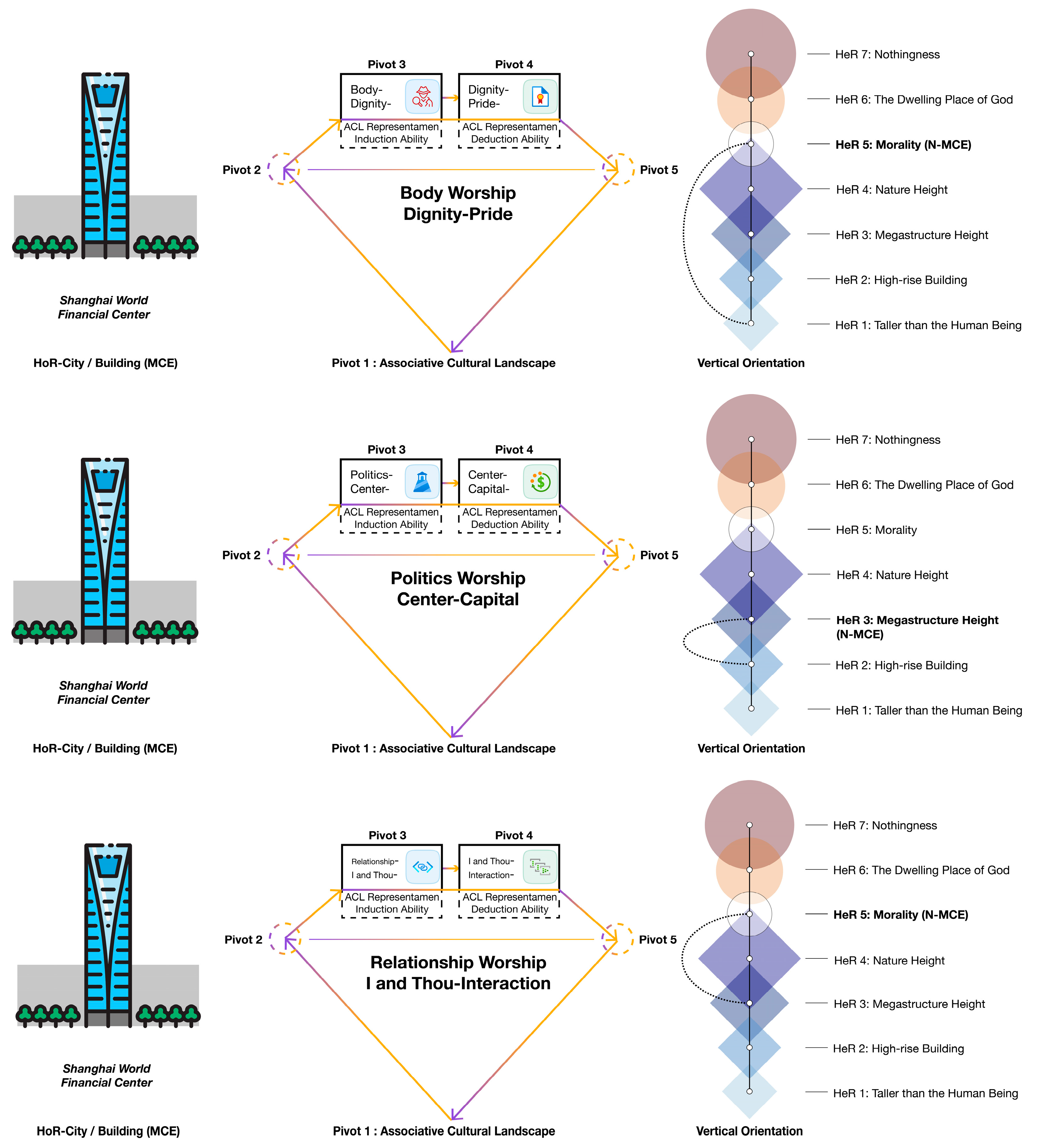

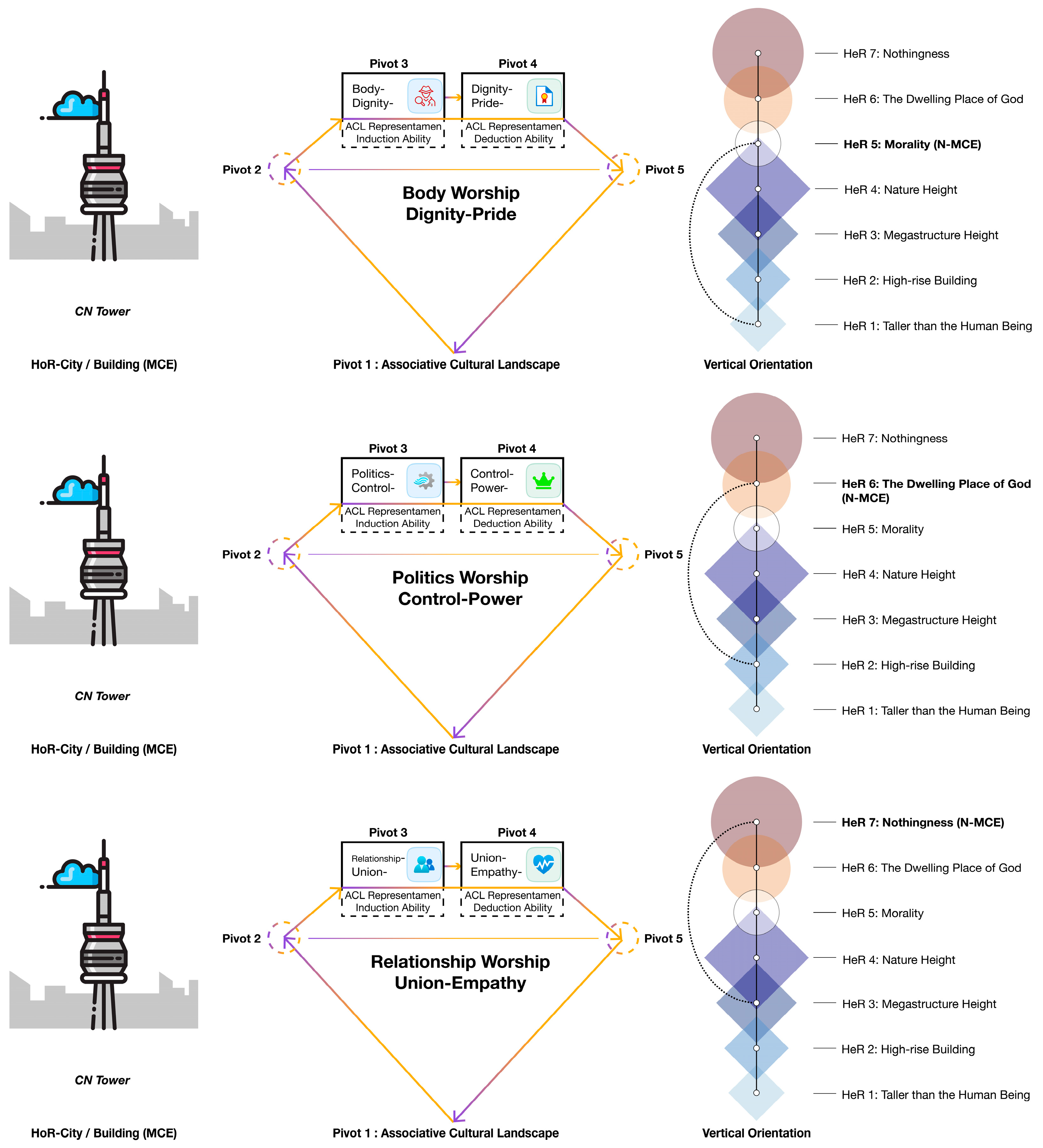

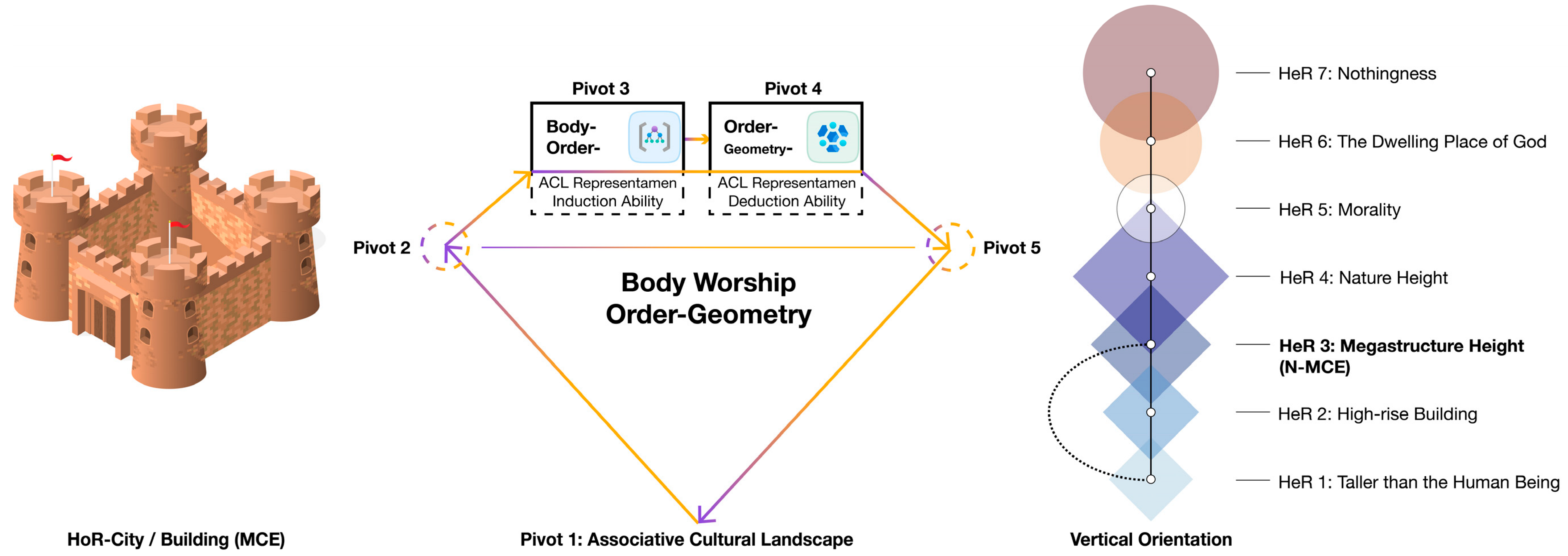

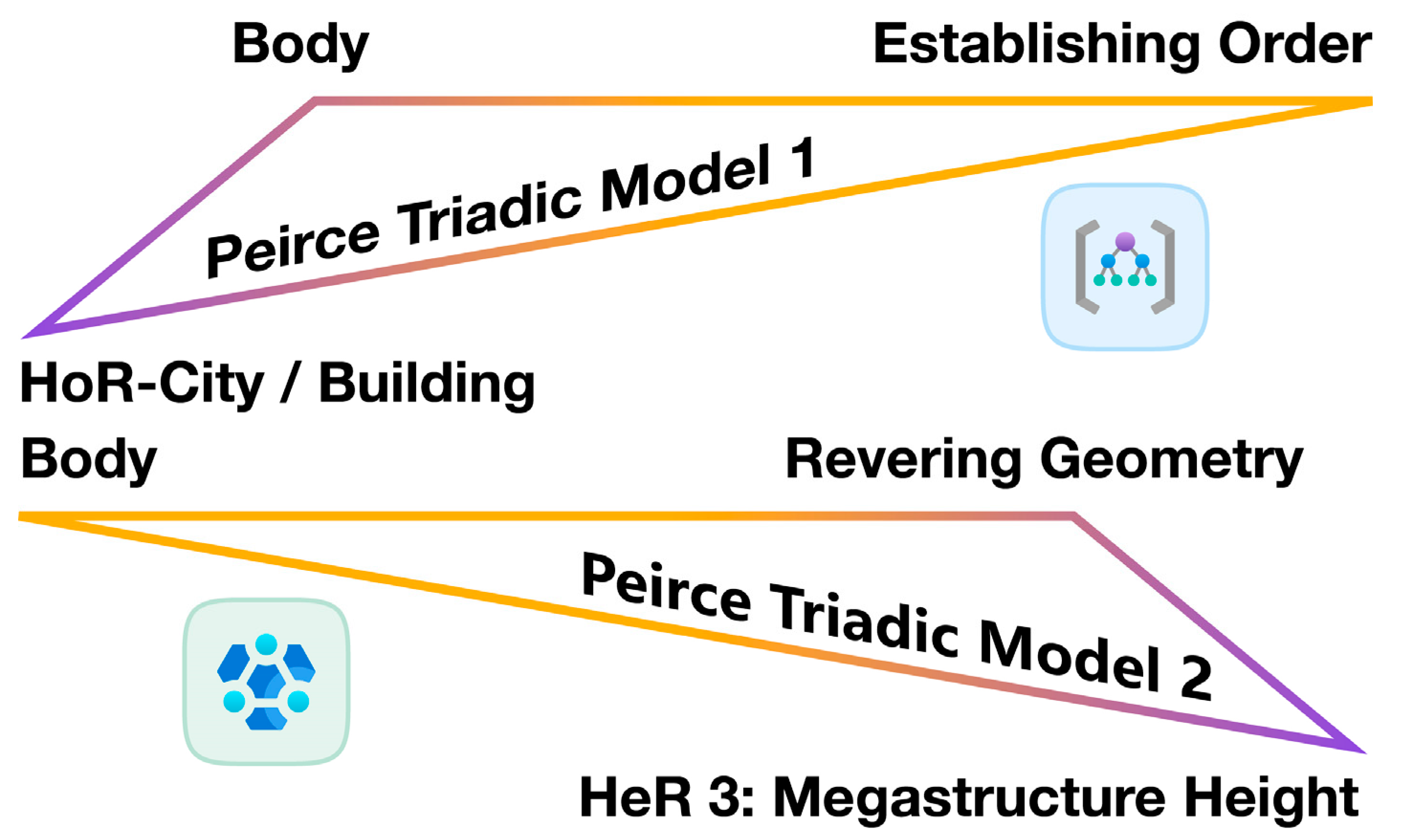

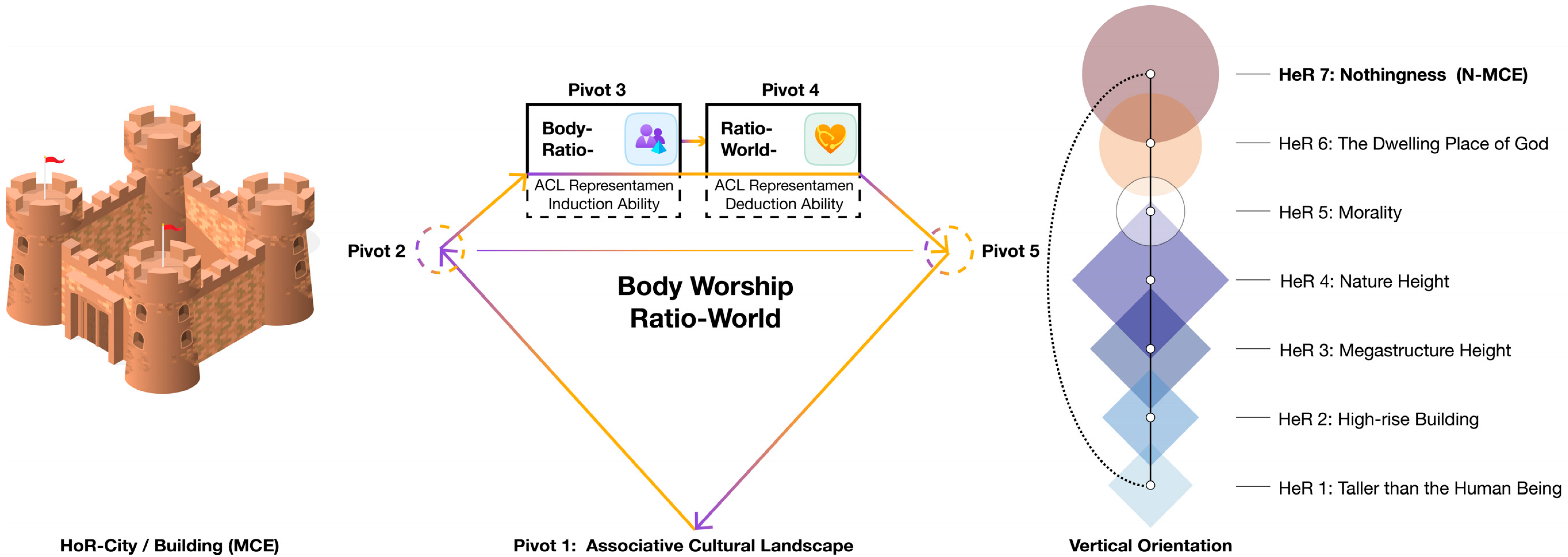

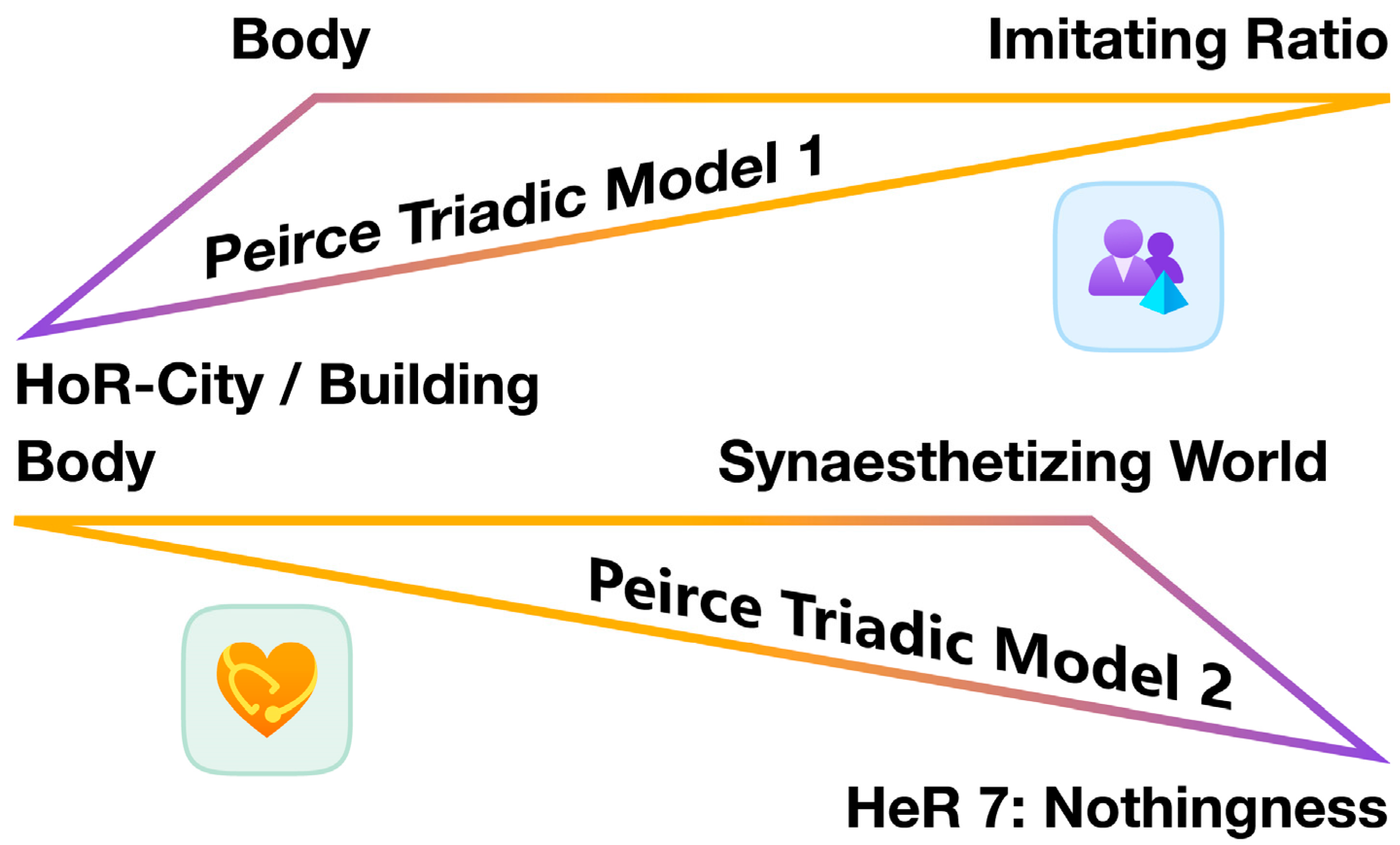

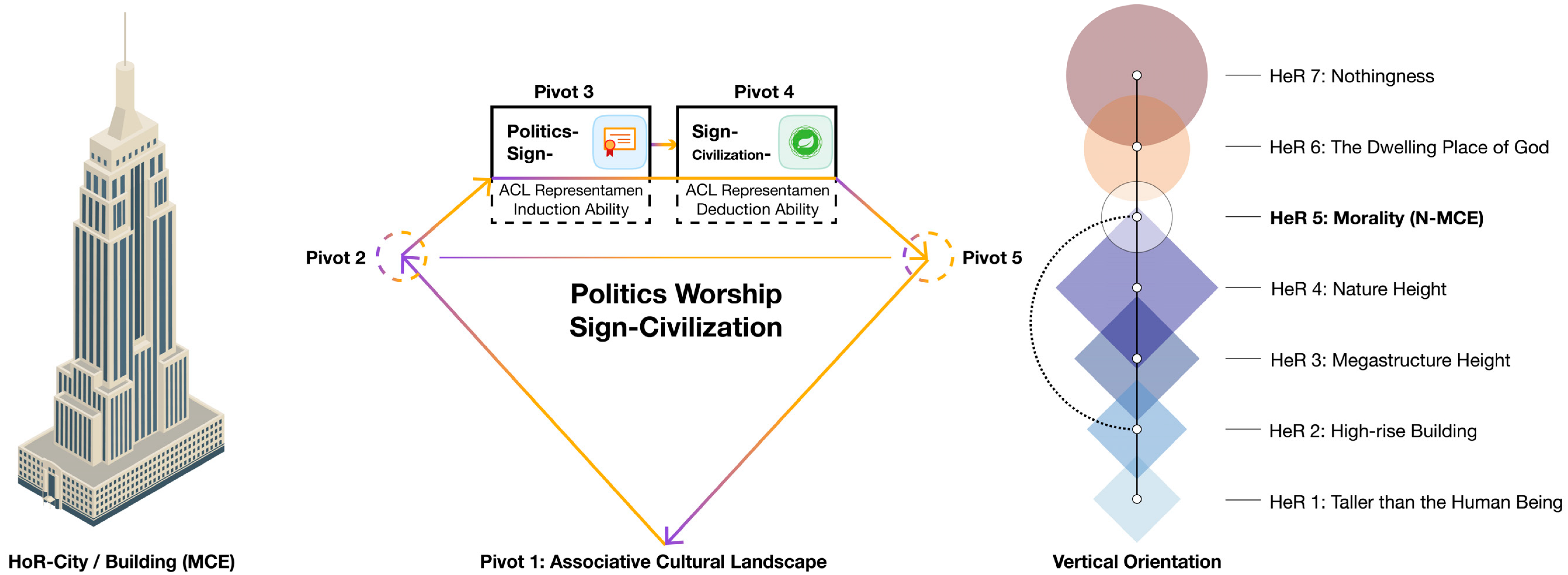

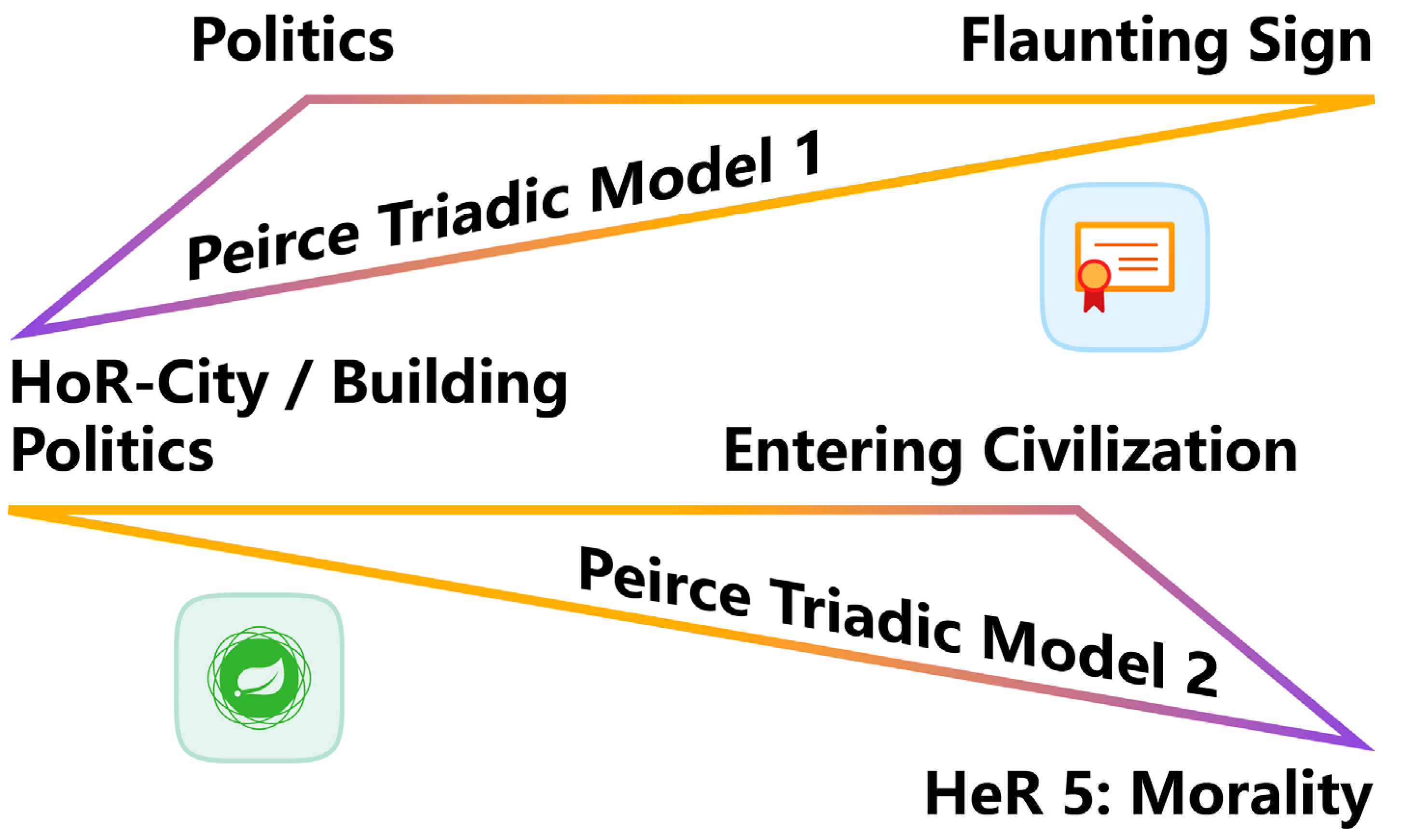

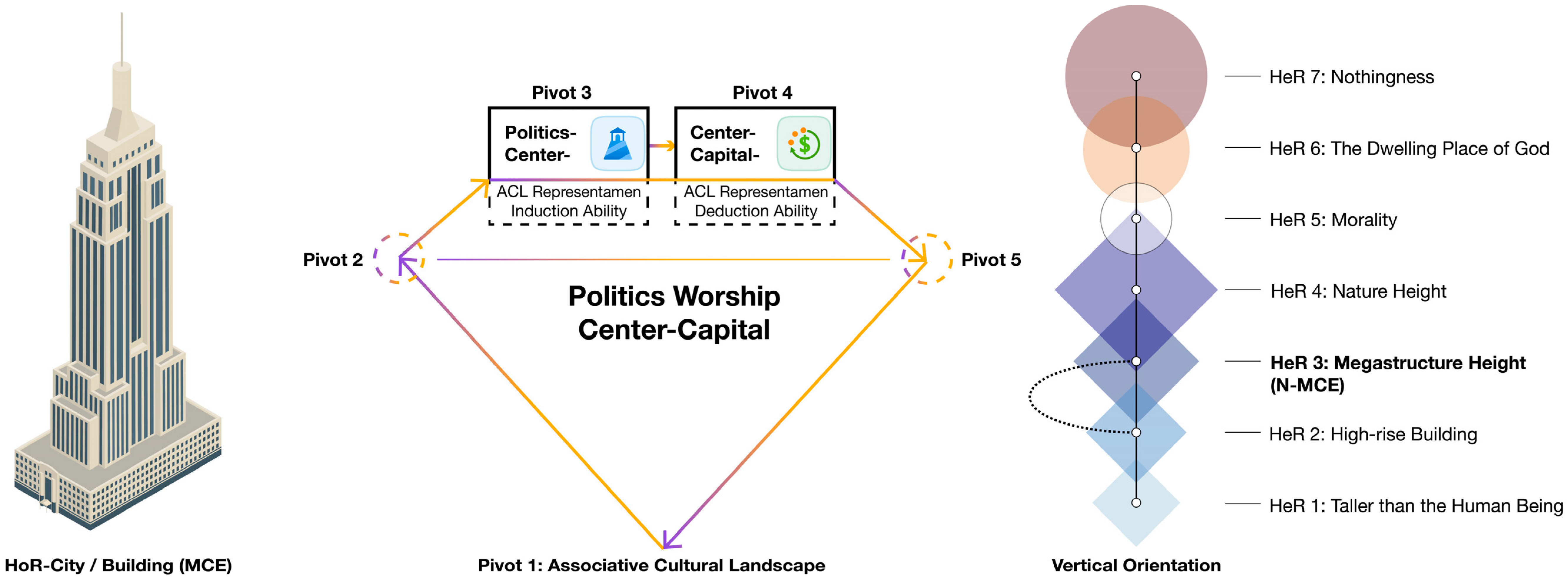

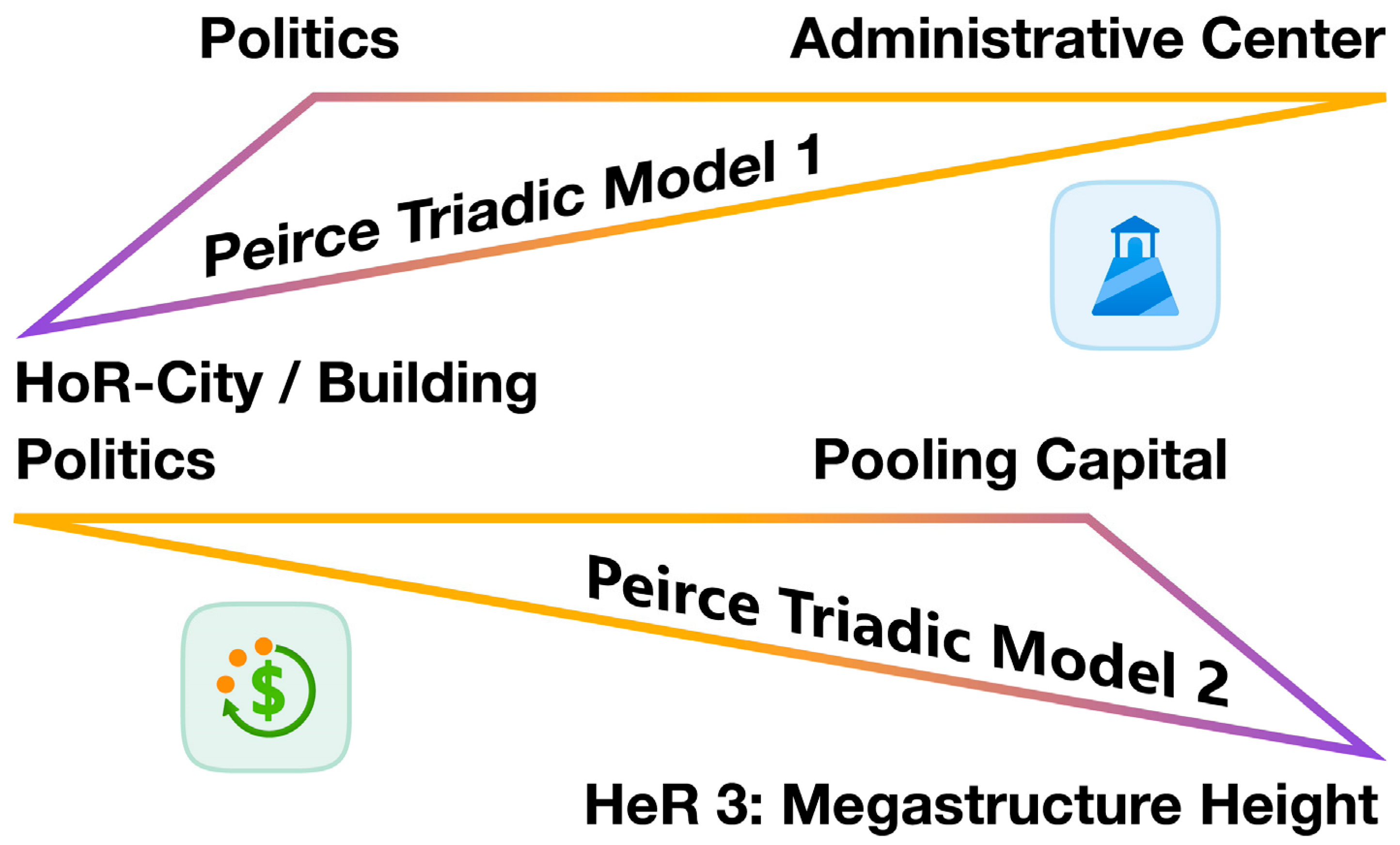

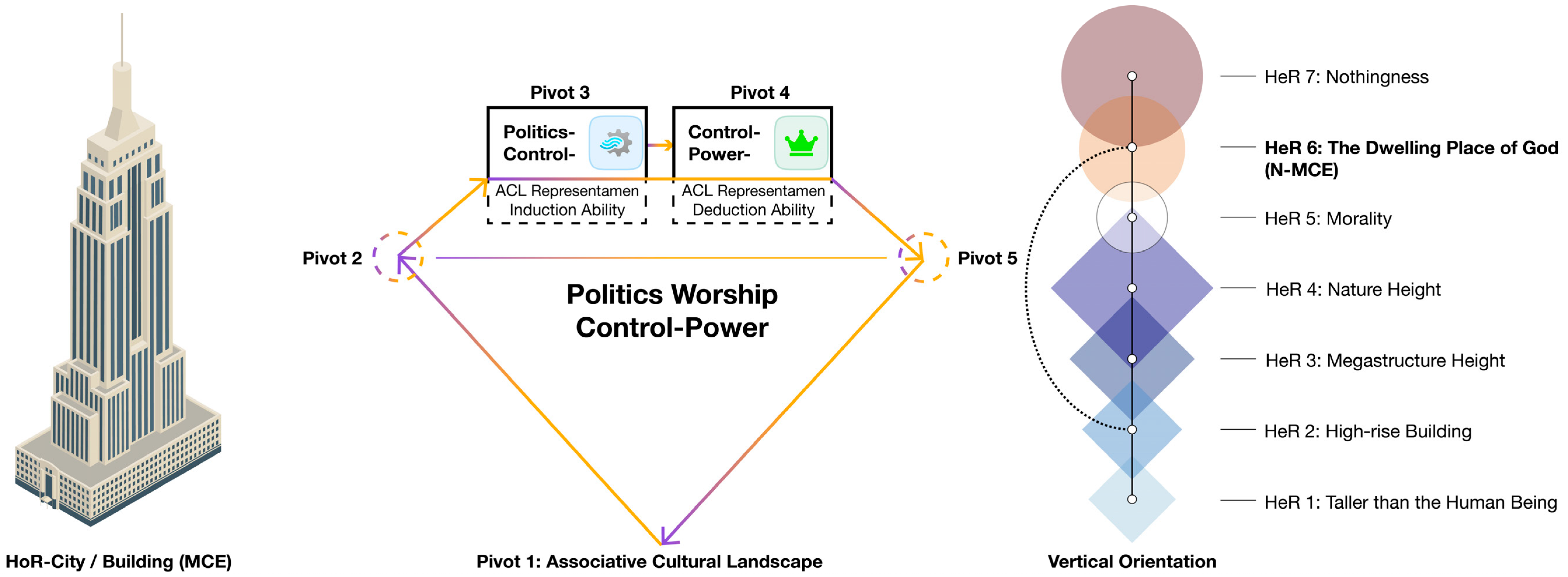

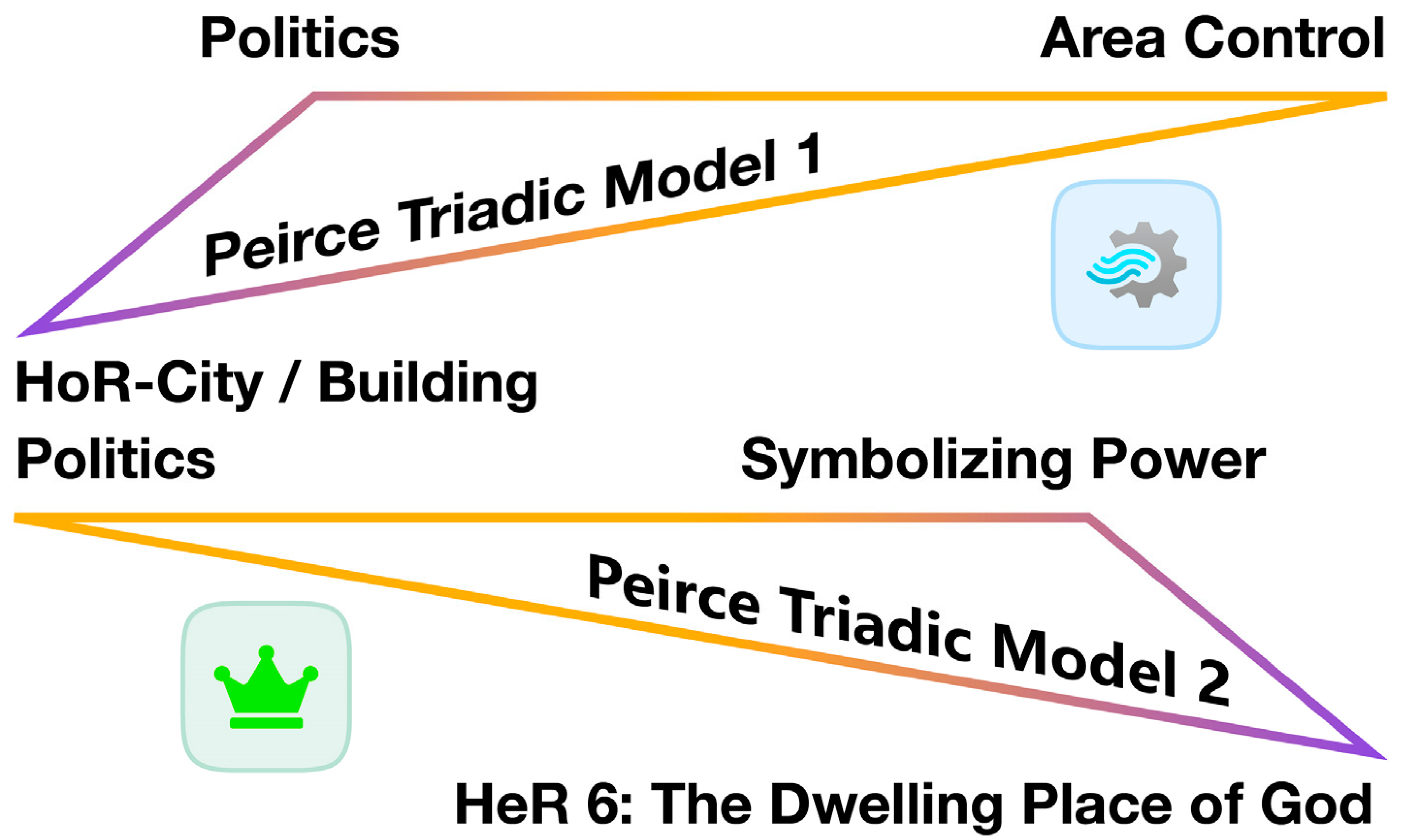

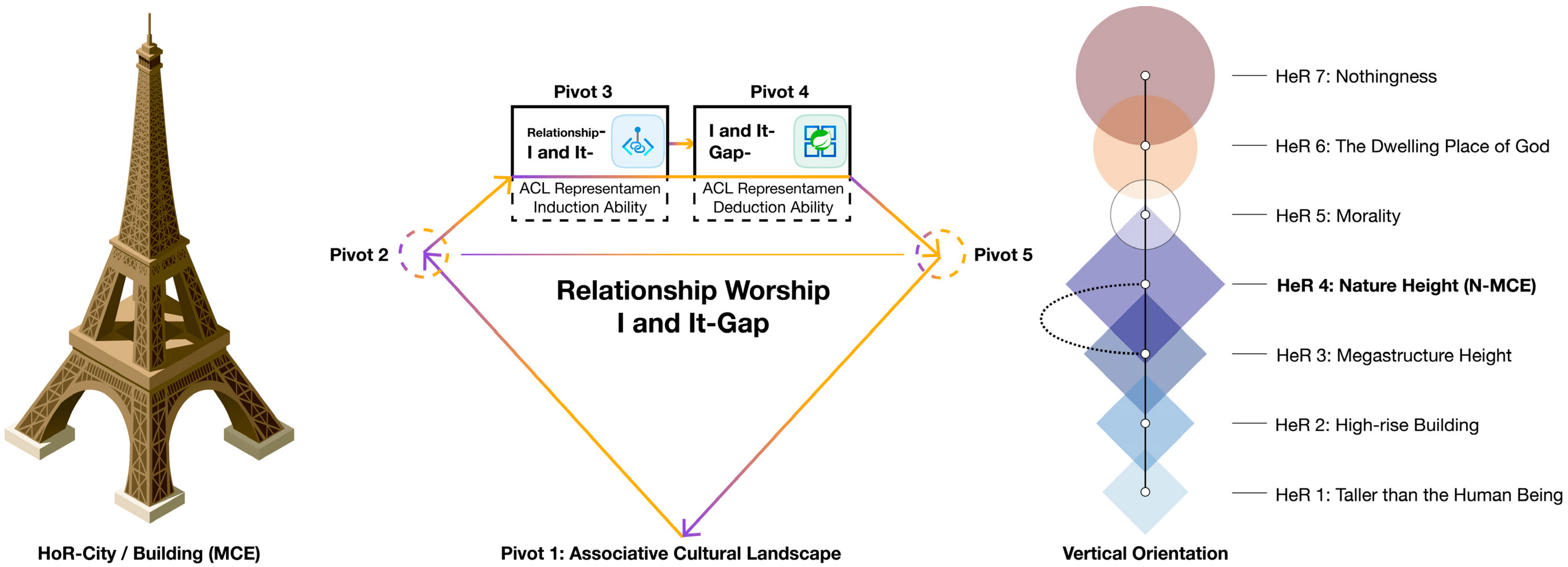

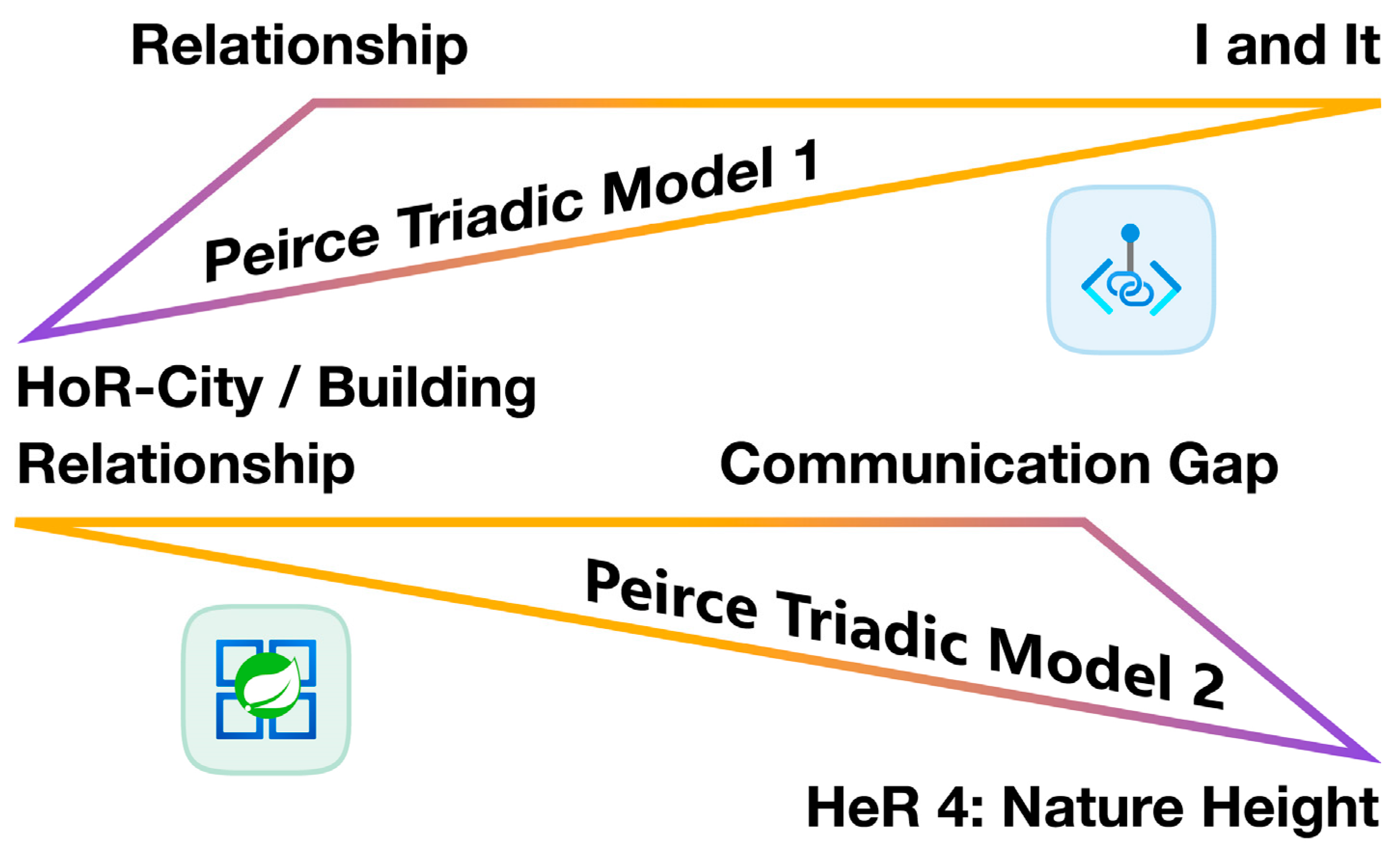

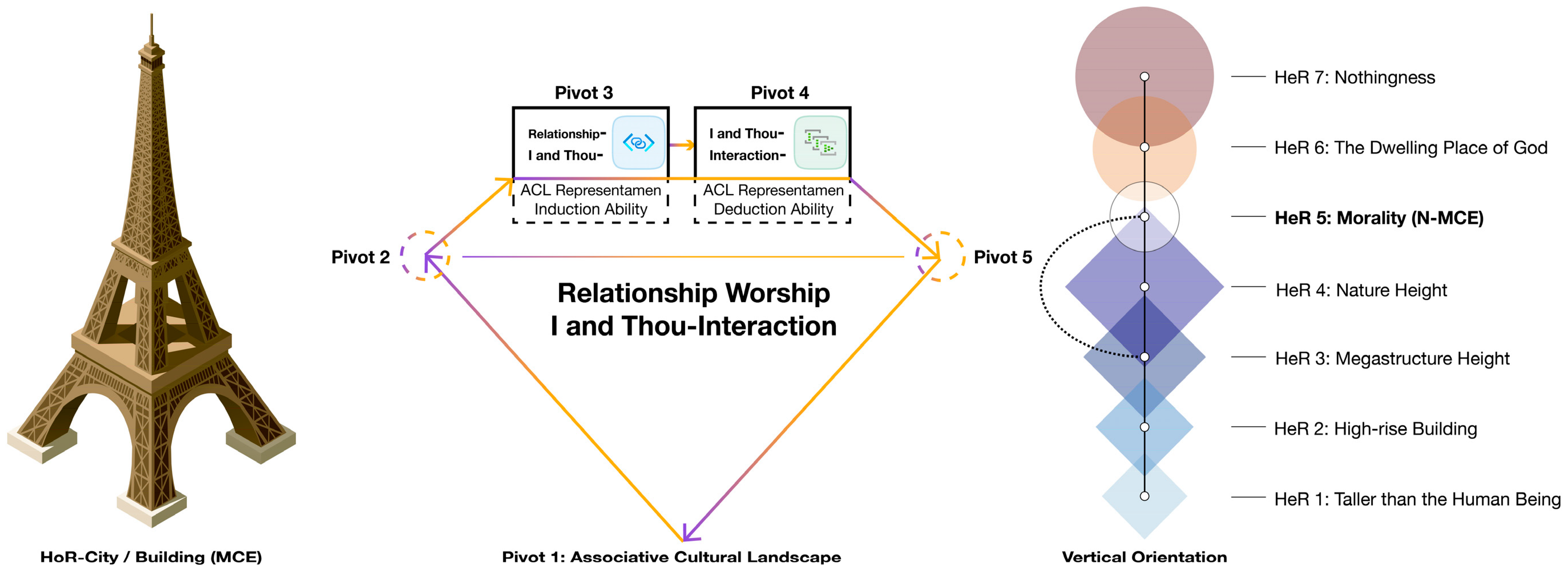

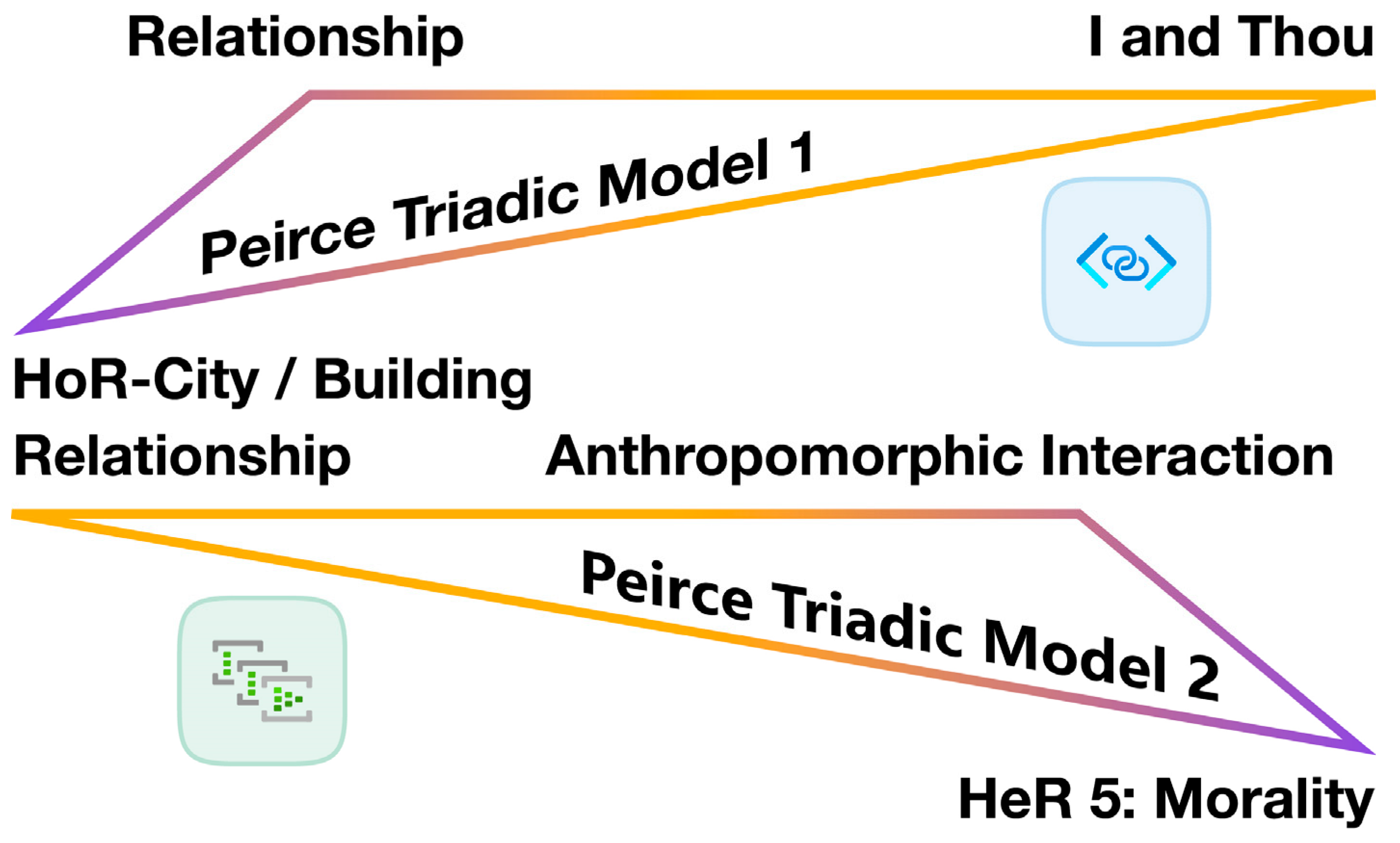

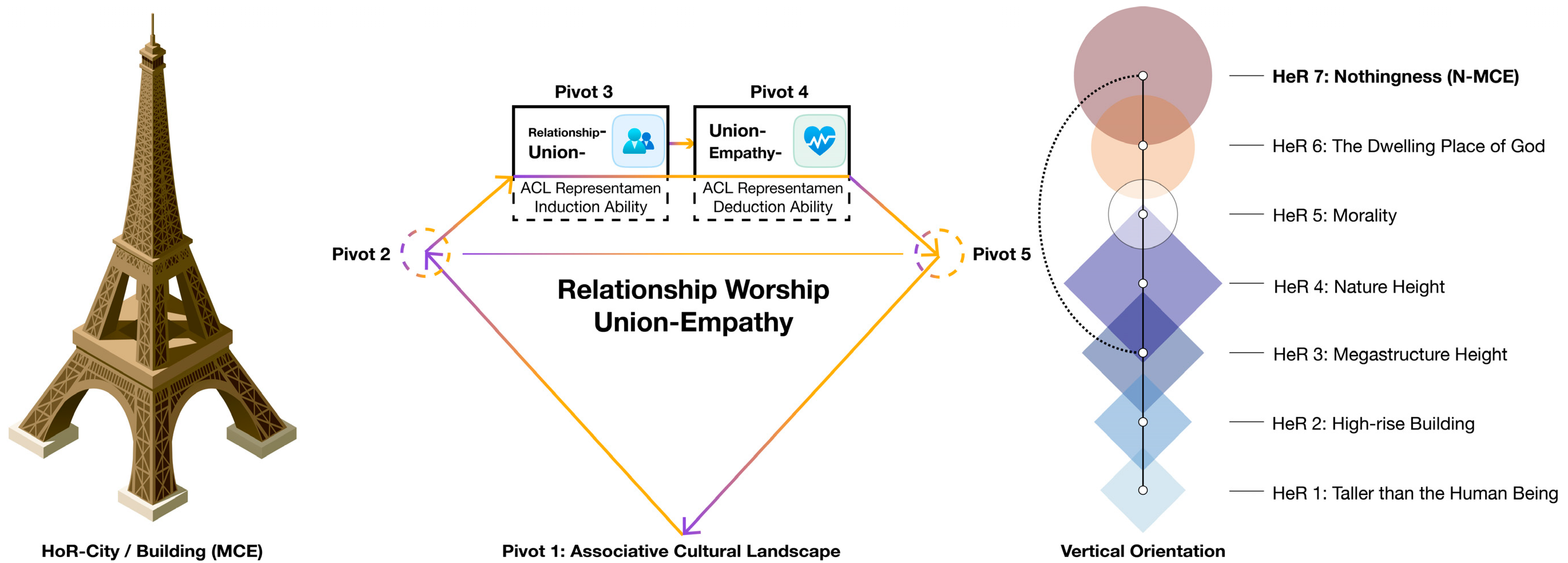

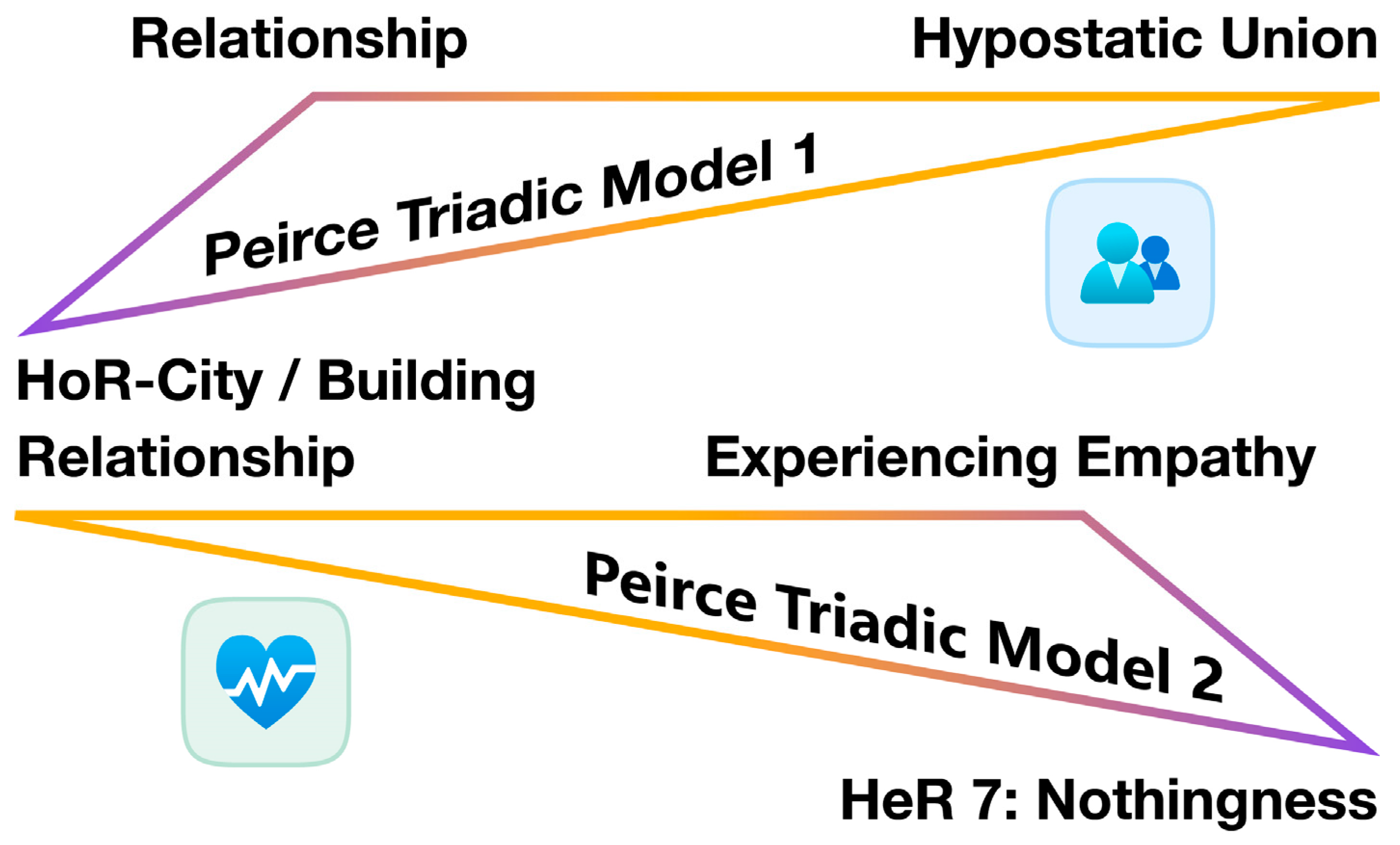

- From Pivot 2 to Pivot 5, two symbolic triadic models are formed through Peirce Triadic Model [61];

- The megastructure “verticality” is MCE (corresponding to HeR1, HeR2, HeR3 of vertical orientation), and the orientational metaphor is N-MCE (corresponding to the process of connecting two HeRs of the vertical orientation, such as “HeR1-HeR7”);

- Therefore, megastructure worship utilizes the interpretive power of the orientational metaphors within the specific problem of “verticality”, to form the methodology of this study—O-ACL methodology (Figure 5).

4. O-ACL Methodology: The Interpretation Methodology of Megastructure Worship

4.1. Applying the Arbor Porphyriana: The Ontology of Megastructure

4.2. Three Interpretation Perspectives of Megastructure Worship

4.2.1. Body Worship

4.2.2. Politics Worship

4.2.3. Relationship Worship

4.3. The Nine Applied Models of O-ACL Methodology: The Interpretation Models of Megastructure Worship

- Dignity–Pride (HeR1–HeR5): The ancient Athenians derived their dignity from the act of exposing their bodies, and they integrated embodied actions into urban development and architectural construction. The individual’s physical body was expanded and satisfied by the scale of the cities and the buildings, and they flaunted their egos in the naked forms of the cities and the buildings, thereby gaining pride from relying on the cities and the buildings.

- Order–Geometry (HeR1–HeR3): When the Roman emperor Hadrian built the Pantheon, he used visual order to control the stones and light, extending the geometry of the human body according to human body proportions, and establishing a subtle balance between visual order and body geometry. This balance connected the geometric relationship between the body and the building, and promoted people’s worship of cities and buildings, formed under the control of body geometry.

- Ratio–World (HeR1–HeR7): The builders of the Notre Dame Cathedral in the Middle Ages established a way of constructing the relationship between human beings and the value of the world by carving sculptures of real people. By carving sculptures of real people, they attached personal emotions, happiness, and pain to the building. They used the universal value recognition of the building in the world to achieve religious worship involving more people and a wider range of people, and ultimately, to return to the worship of cities and buildings.

- Sign–Civilization (HeR2–HeR5): Cities and buildings are symbols of political identity. They have the nature of transitional detachment from the barbaric environment, and at different points in time, they constantly deepen the process of civilization by highlighting their status. Cities and buildings are used as important symbols of the progress of various civilizations, highlighting the political propaganda, attitude and breadth of each major civilization. A macroscopic image is used to form a cluster of symbols using giant structures.

- Center–Capital (HeR2–HeR3): Ancient Chinese cities with unnatural population agglomerations gradually became a political heart in a political network. The concentrated construction of cities and buildings presupposes the imminent formation of a political center, the collection of productive capital and means of production, and, ultimately, the clustering of cities and buildings to form nodes and capital supply points in a larger political network to serve higher-level political rule.

- Control–Power (HeR2–HeR6): The imperial clans of ancient Chinese dynasties established new, relatively centralized regimes in new regions, using cities and buildings to divide the areas under their control and rule, highlighting them as the supreme embodiment of political power in the new region and symbolizing imperial power and the power to control land.

- I and It–Gap (HeR3–HeR4): The mutual perception of humans and megastructures experiences the process of going from barbarism to rational observation. When there is insufficient production data or knowledge reserves, humans’ perception of cities and buildings is relatively exclusionary and taciturn, and the handling of relationships is weak: that is, humans are unable to perceive and respond to the external image of cities and buildings.

- I and Thou–Interaction (HeR3–HeR5): Cities and buildings gradually become anthropomorphic in the process of human civilization, becoming huge objects in human society that transcend ontological existence and meet human emotional needs. They are closely related to human daily life in terms of psychology, physiology, emotional value, safety, and other aspects.

- Union–Empathy (HeR3–HeR7): Cities and buildings are anthropomorphized, becoming communities that humans can emotionally connect with and participate in. After establishing a subconscious and stable relationship with the human soul, cities and buildings are no longer just giant objects that are removed from the human experience. Instead, they become megastructures that humans can empathize with on a vertical scale, in terms of their emotions and psychological feelings.

4.4. Building the Matrix of O-ACL Methodology

4.5. The Empirical Analysis

4.5.1. Empirical Application of O-ACL Methodology: Burj Khalifa

“When we developed Burj Khalifa, we had a clearly articulated vision of not just delivering an icon that underlines the ambitions and spirit of global collaboration that defines Dubai, but also to maximize the value of the land by creating a truly “vertical city”.”—Mohamed Ali Alabbar [79]

4.5.2. Empirical Application of O-ACL Methodology: Shanghai World Financial Center

4.5.3. Empirical Application of O-ACL Methodology: CN Tower

4.6. The Framework of O-ACL Methodology

5. Discussion

- Exogenous spatial homogeneous symbol is replaced with HoR;

- Endogenous spatial heterogeneous symbol is replaced with HeR;

- Space-abstraction-symbol is replaced with Peirce Triadic Model 1;

- Symbol-abstraction-spirit is replaced with Peirce Triadic Model 2.

6. Conclusions

- Body worship: Emphasizing that megastructures are an extension of the human body and a support for emotions, and that the human body is the mold for megastructure design;

- Political worship: Megastructures are symbols and representations of human authoritarian organizations, representing the ability to control the land and the people;

- Relationship worship: Removing megastructures from the category of commodities and establishing an intimate psychological relationship between people and megastructures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

References

- SkyscraperPage. Available online: https://skyscraperpage.com/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Hertzberger, H. Lessons for Students in Architecture; Uitgeverij 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Megaform as Urban Landscape. J. Delta Urban. 2012, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algiers Project. Available online: https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/21261 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Maki, F. Investigations in Collective Form; Washington University, The School of Architecture: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1964; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, F. On Collective Form. Docomomo 2015, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolhaas, R. Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture; Architectural Association School of Architecture: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Böck, I. Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas: Essays on the History of Ideas; Jovis Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R.; Mau, B. S, M, L, XL; The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Deyong, S.J. The Creative Simulacrum in Architecture: Megastructure 1953–1972. Ph.D. Thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Banham, R. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past; The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Megaform as Urban Landscape: 1999 Raoul Wallenberg Lecture; The University of Michigan A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture+ Urban Planning: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1999; ISBN 1-891197-08-8. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 5th ed.; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Seven Milestones for the Third Millennium—An Untimely Manifesto. Archit. J. 1998, 5, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Y. Research on Megastructure Evolution and its Contemporary Practice. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaika, M. City of Flows: Modernity, Nature, and the City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, D. Skyscraper Geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politakis, C. Architectural Colossi and the Human Body: Buildings and Metaphors; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. Buildings 2022, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M. Everyday Verticality: Migrant Experiences of High-rise Living in Santiago, Chile. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardenberg, W.G.V.; Mahony, M. Introduction—Up, Down, Round and Round: Verticalities in the History of Science. Centaurus 2020, 62, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, M.S. The Most Recent Orogeny: Verticality and Why Mountains Matter. Hist. Stud. Nat. Sci. 2017, 47, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. Urban Verticality Shaped by a Vertical Terrain: Lessons From Chongqing, China. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roast, A. Towards Weird Verticality: The Spectacle of Vertical Spaces in Chongqing. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastrow, C. DIY Verticality: The Politics of Materiality in Luanda. City Soc. 2020, 32, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R. The High-Rise Home: Verticality as Practice in London. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M. Interpreting Art through Metaphors. Int. J. Art Des. Ed. 2010, 29, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.; Ferrè, E.R. The Aesthetics of Verticality: A Gravitational Contribution to Aesthetic Preference. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2018, 71, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.E.; Schloss, K.B.; Sammartino, J. Visual Aesthetics and Human Preference. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepian, M.L.; Masicampo, E.J.; Ambady, N. Cognition from on High and Down Low: Verticality and Construal Level. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. Verticalities of the Imagination: Futurity and the Contemporary in Urban Science Fiction. In Mountains and Megastructures: Neo-Geologic Landscapes of Human Endeavour; Beattie, M., Kakalis, C., Ozga-Lawn, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I. From Picturesque Detachment to Bodily Engagement: The Entwined Histories of Photography, Architecture and Climbing. In Mountains and Megastructures: Neo-Geologic Landscapes of Human Endeavour; Beattie, M., Kakalis, C., Ozga-Lawn, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Private Limited: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sharr, A. A Megastructure and a Mountain: Two Ways of Thinking About Architecture. In Mountains and Megastructures: Neo-Geologic Landscapes of Human Endeavour; Beattie, M., Kakalis, C., Ozga-Lawn, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, M.; Kakalis, C.; Ozga-Lawn, M. Mountains and Megastructures: Neo-Geologic Landscapes of Human Endeavour. In Mountains and Megastructures: Neo-Geologic Landscapes of Human Endeavour; Beattie, M., Kakalis, C., Ozga-Lawn, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, H.K. An Incomplete Megastructure: The Golden Mile Complex, Global Planning Education, and the Pedestrianised City. J. Archit. 2020, 25, 472–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, L. Megastructures: A Great-size Solution for Affordable Housing. Hist. Postwar Archit. 2018, 1, 72–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Muñoz, A. From the High-Rise Housing Block to the Megastructure in the Air: A Critical Reflection on the Contemporary Vertical City. Rita Rev. Indexada Textos Acad. 2020, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Muñoz, A. Vertical Urbanization: The Territorial Crisis of a Universal Model. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1203, 022123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, V. The Tragedy of the Megastructure. Hist. Postwar Archit. 2018, 1, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooyen, X.V. Megaform Versus Open Structure or the Legacy of Megastructure. Hist. Postwar Archit. 2018, 1, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.S. Evolution of Tall Building Structures with Perimeter Diagonals for Sustainable Vertical Built Environments. Int. J. High-Rise Build. 2023, 12, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. Luxified Skies: How Vertical Urban Housing Became an Elite Preserve. City 2015, 19, 618–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Cultural Landscapes. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Zhang, P.; Han, F.; Du, S. From The Philosophical Tree to “The Philosophical Tree”: An Approach to Interpret the Symbolic Meaning of Natural Archetypes of Associative Cultural Landscape. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y. From the Perspective of Huangdi-Neijing to “Five Elements of Qi”: Examining the Formation Principle of Urban-Rural “Skin” Landscape. Archit. Cult. 2023, 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulos, D.; Wallenwein, F.; Mildenberger, G.; Schimpf, G.-C. A Dialogue between the Humanities and Social Sciences: Cultural Landscapes and Their Transformative Potential for Social Innovation. Heritage 2023, 6, 7674–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Landscape and Meaning: Context for a Global Discourse on Cultural Landscape Values. In Managing Cultural Landscapes; Taylor, K., Lennon, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. Cultural Landscapes: A Bridge Between Culture and Nature? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Cultural Landscapes and Asia: Reconciling International and Southeast Asian Regional Values. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, B.; McKinnon, S. Movie Tourism—A New Form of Cultural Landscape? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössler, M. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A UNESCO Flagship Programme 1992–2006. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Xi, X.; Zhang, G.; Liang, S. Interpretation of Associative Cultural Landscape Based on Text Mining of Poetry: Taking Tianmu Mountain on the Road of Tang Poetry in Eastern Zhejiang as an Example. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C.; Rățulea, G.G. The Culture-centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania). Land 2022, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, S. Associative Cultural Landscape Approach to Interpreting Traditional Ecological Wisdom: A Case of Inuit Habitat. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, R.; Snodgrass, A.; Martin, D. Metaphors in the Design Studio. J Archit. Educ. 1994, 48, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Stimulating Architects’ Mental Imagery Reaching Innovation: Lessons from Urban History in Using Analogies and Metaphors. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, B.P.; Hauser, D.J.; Robinson, M.D.; Friesen, C.K.; Schjeldahl, K. What’s “Up” with God? Vertical Space as a Representation of the Divine. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, J.M.; Elsner, B.; Pollatos, O. Good is Up—Spatial Metaphors in Action Observation. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, N. Peirce, Phenomenology and Semiotics. In The Routledge Companion to Semiotics; Cobley, P., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. From the Tree to the Labyrinth: Historical Studies on the Sign and Interpretation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects; Harcourt Brace Janovich, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell, R. The Theoretical Attitude Towards Space in the Middle Ages. Speculum 1946, 21, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.F. State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan; Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, J.; Wang, L.; Lu, G.-D. Civil Engineering and Nautics (Pt. 3). In Science and Civilization in China: Physics and Physical Technology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1971; Volume 4, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.-C. Art, Myth and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.-C. The Archaeology of Ancient China; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, M. I and Thou; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E. Zum Problem der Einfühlung; Verlag Herder GmbH: Freiburg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan; The Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, L. The Icon Project: Architecture, Cities and Capitalist Globalization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bagaeen, S. Brand Dubai: The Instant City; or the Instantly Recognizable City. Int. Plan. Stud. 2007, 12, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Sagir, A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Yakubu, A.; Zakari, A.T.; Usman, A.M.; Nashe, A.S.; Hamma, A.S. A Review of Conceptual Design and Self Health Monitoring Program in a Vertical City: A Case of Burj Khalifa, U.A.E. Buildings 2023, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N. Beyond the Veil of Form: Developing a Transformative Approach toward Islamic Sacred Architecture Through Designing a Contemporary Sufi Centre. Religions 2022, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuto, M. High-rise Dubai Urban Entrepreneurialism and the Technology of Symbolic Power. Cities 2010, 27, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbar, M.A.; Safarik, D. Talking Tall: His Excellency Mohamed Ali Alabbar: Towering Aspirations in Dubai and Beyond. CTBUH J. 2018, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kodmany, K.; Ali, M.M. Skyscrapers and Placemaking: Supporting Local Culture and Identity. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2012, 6, 43. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Name | Location | Height (m) | Floors | Year | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Burj Khalifa | Dubai | 828 | 163 | 2010 | Mixed use |

| (b) | Merdeka PNB118 | Kuala Lumpur | 678.9 | 118 | 2023 | Mixed use |

| (c) | Tokyo Sky Tree | Tokyo | 634 | 32 | 2012 | Communication |

| (d) | Shanghai Tower | Shanghai | 632 | 128 | 2015 | Office |

| (e) | Canton Tower | Guangzhou | 604 | 37 | 2010 | Observation |

| (f) | Abraj Al Bait | Mecca | 601 | 120 | 2012 | Hotel |

| (g) | Ping An International Finance Centre | Shenzhen | 599.1 | 115 | 2017 | Office |

| (h) | Lotte World Tower | Seoul | 555 | 123 | 2017 | Mixed use |

| (i) | CN Tower | Toronto | 553.3 | 147 | 1976 | Communication |

| (j) | One World Trade Center | New York | 546.2 | 94 | 2014 | Office |

| ||||||

| No. | Considerations | ACL | Megastructure | Megastructure Worship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cultural Landscape | Strong | √ | × | |

| Weak | √ | √ | |||

| 2 | The Co-Work of Man and Nature | √ | √ | √ | |

| 3 | Material Cultural Evidence | √ | √ | √ | |

| 4 | Non-Material Cultural Evidence | √ | √ | √ | |

| 5 | Spiritual Relevance | √ | √ | √ | |

| 6 | Interaction of Culture and Nature | √ | √ | √ | |

| 7 | Sustainable Land Use | √ | × | × | |

| 8 | Biocultural Diversity | √ | × | × | |

| 9 | Definition of Landscape | √ | √ | √ | |

| 10 | Relative Permanence | √ | √ | √ | |

| Event/Time | Human Body/Organ | Reasons for Body Worship |

|---|---|---|

| Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (BC431) | Ancient Athenians exposed their bodies | The artist Clark observes that the naked and exposed body represents strength and civilization, rather than weakness [65]. People realize that it is a symbol of affirmation of their dignity as citizens and pride in their city. |

| The period of the construction of the New Pantheon by the Roman Emperor Hadrian (Campus Martius, AC118) | The Romans were obsessed with using the geometry of the body to construct a set of orders imposed on the world | The Roman Empire brings visual order and power together, and the combination of stone and light in buildings with an ingenious geometric feeling allows people to transfer from their own bodies to an urban design, to generate image worship. |

| Cathédrale Notre Dame de Paris entered its final phase (AC1250) | Church builders tried to carve life-size portraits—“Body Politics” | The use of sympathy serves as a means of bonding the body to the stone and the suffering of the body to religious worship [66]. |

| Core Stage | Derivation Stage |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Xue, B. Orientational Metaphors of Megastructure Worship: Optimization Perspectives on Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology. Buildings 2025, 15, 4321. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234321

Zhang P, Li S, Xue B. Orientational Metaphors of Megastructure Worship: Optimization Perspectives on Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4321. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234321

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peng, Shuai Li, and Binxia Xue. 2025. "Orientational Metaphors of Megastructure Worship: Optimization Perspectives on Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4321. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234321

APA StyleZhang, P., Li, S., & Xue, B. (2025). Orientational Metaphors of Megastructure Worship: Optimization Perspectives on Associative Cultural Landscape Methodology. Buildings, 15(23), 4321. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234321