An Elastoplastic Theory-Based Load-Transfer Model for Axially Loaded Pile in Soft Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Modeling

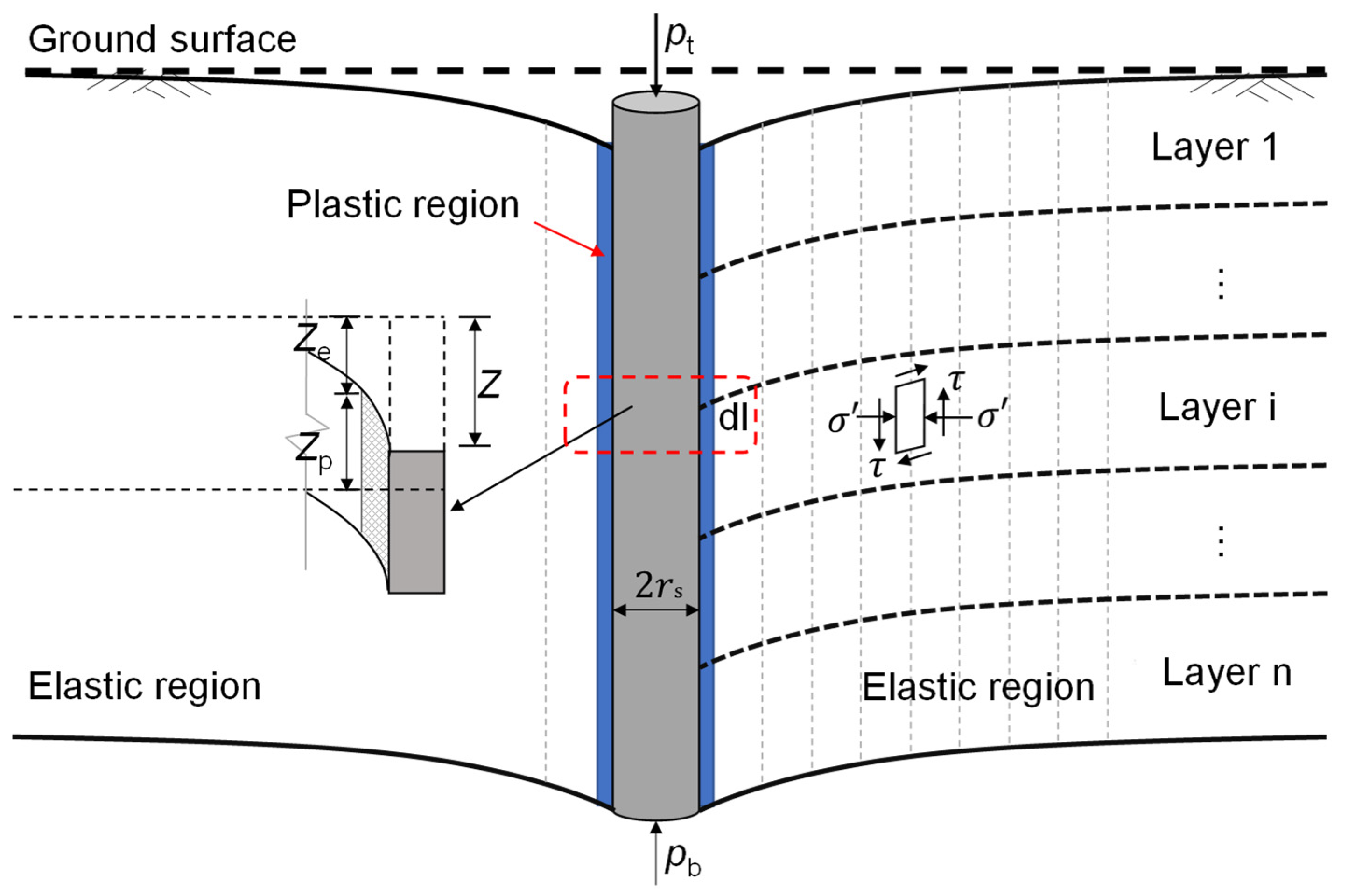

2.1. Pile–Soil Interaction Analysis

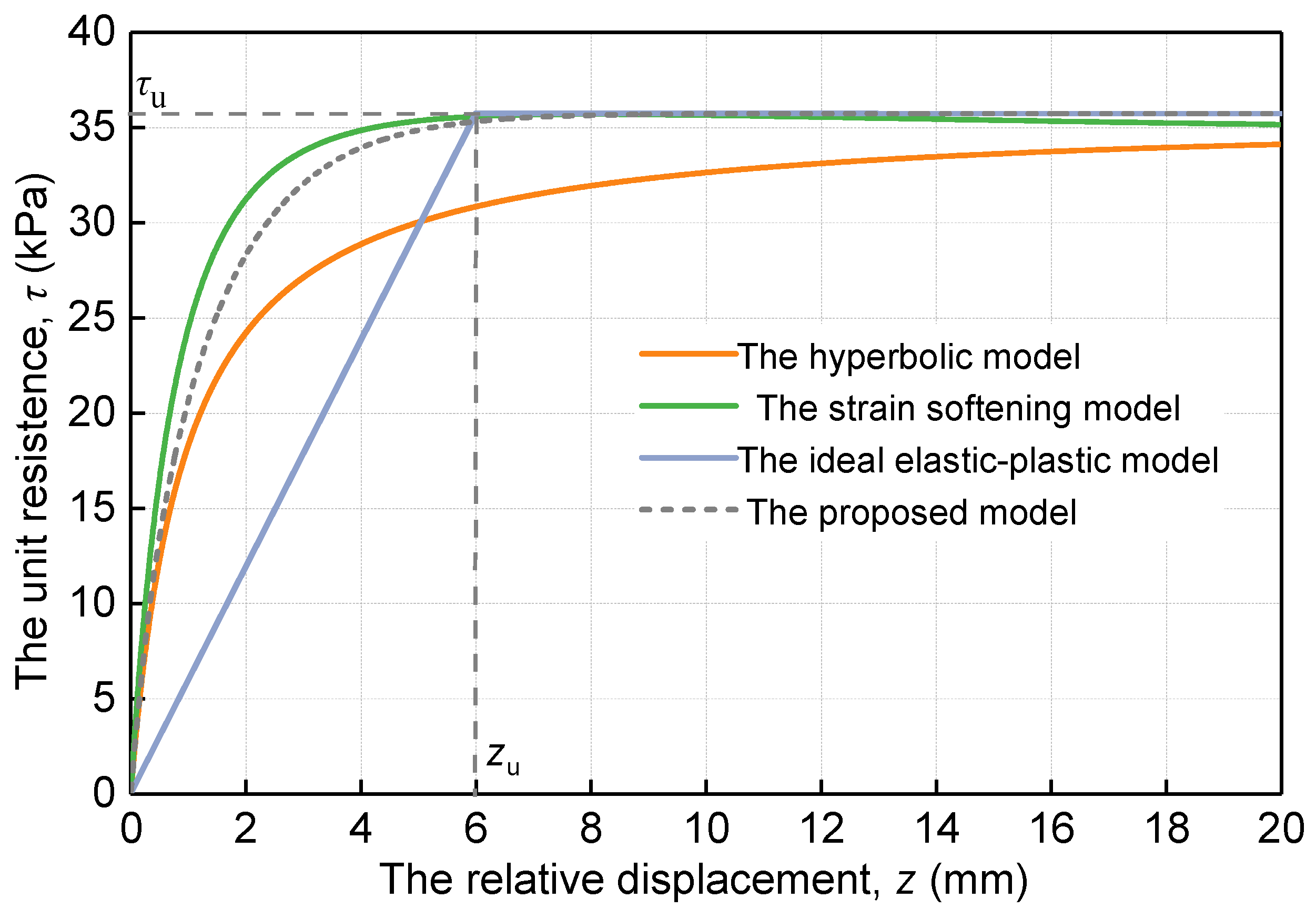

2.2. Load-Transfer Model Development

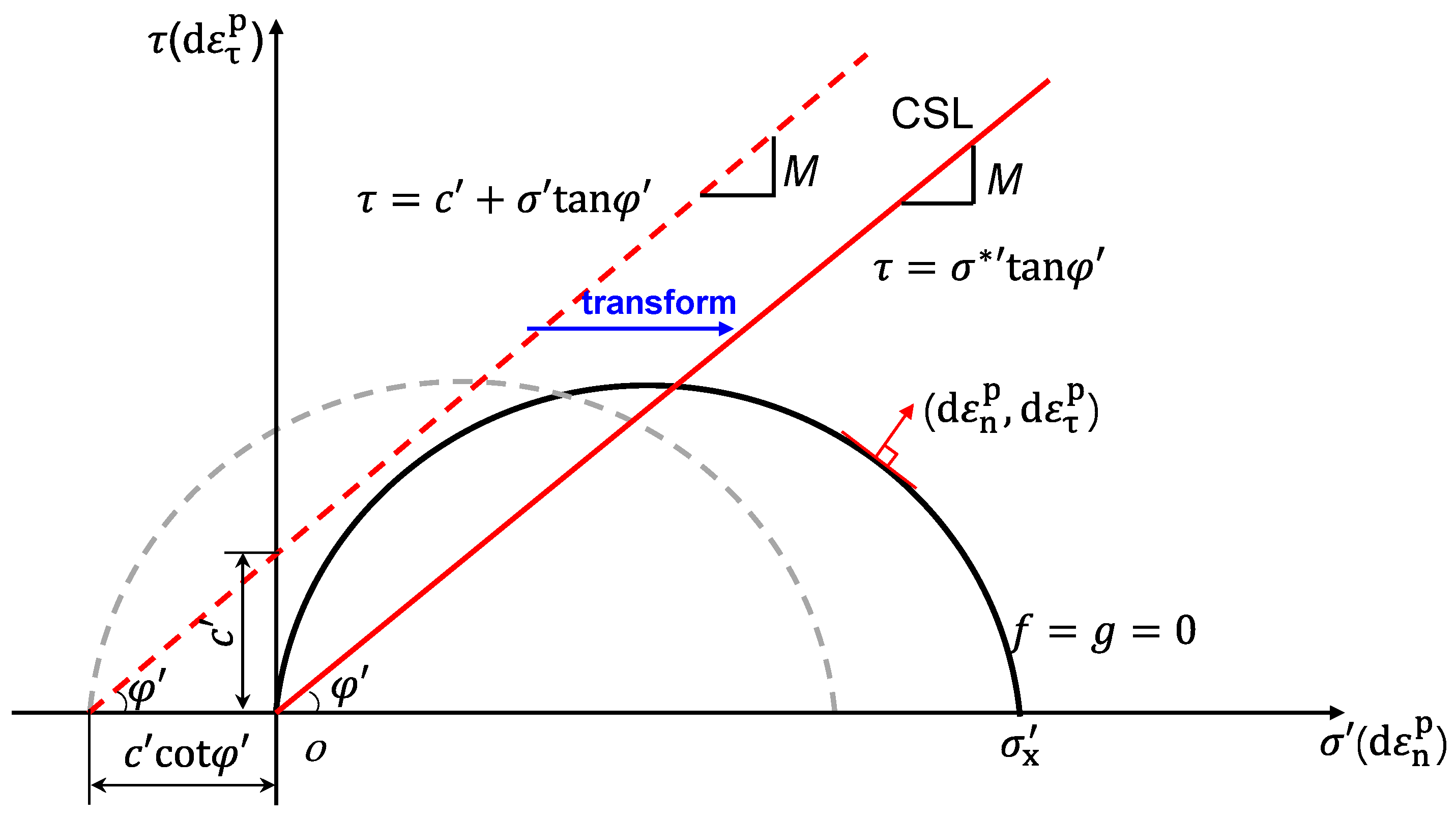

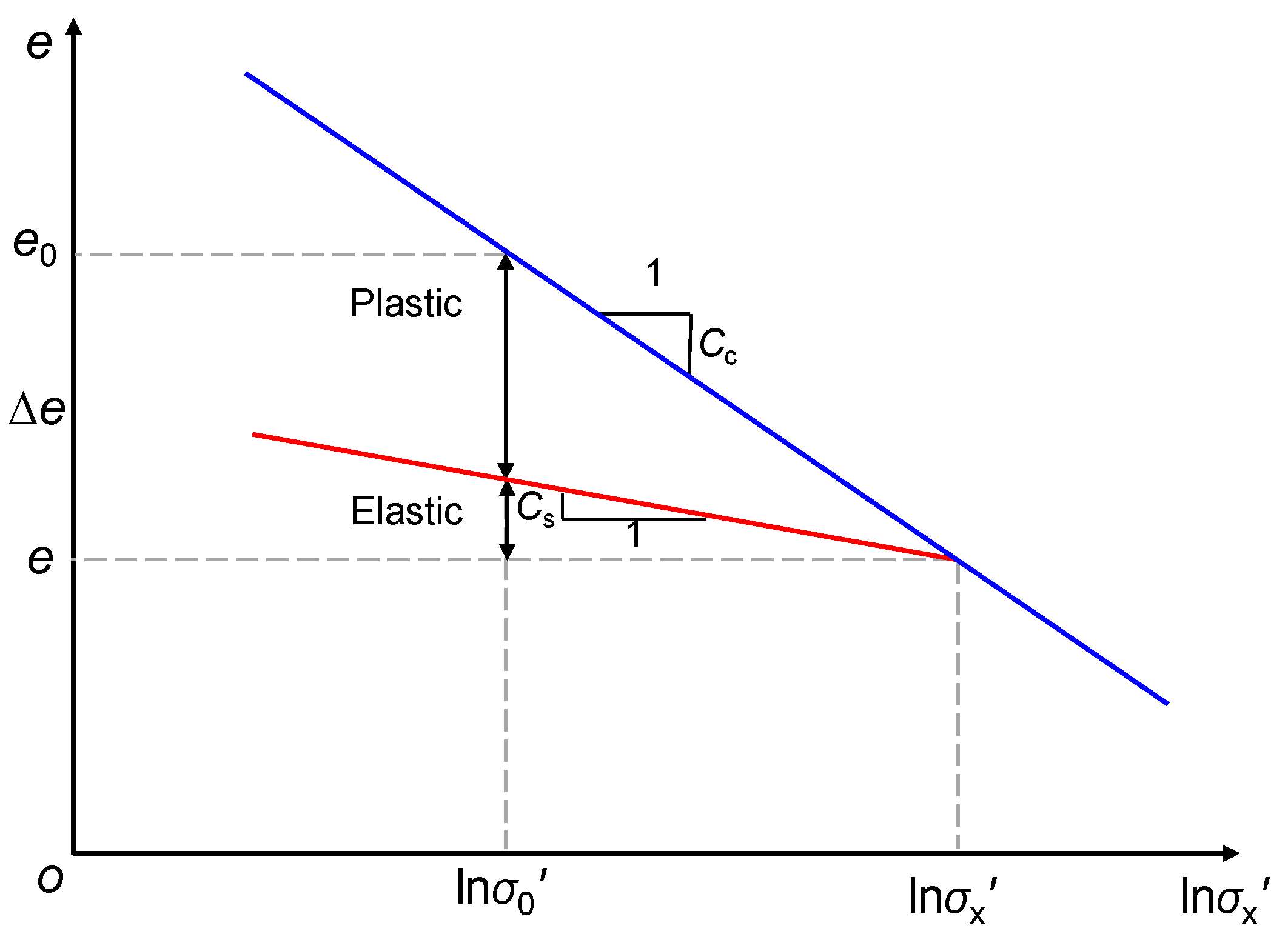

2.2.1. Elastoplastic Deformation in Plastic Zone

2.2.2. Shear Deformation in Elastic Zone

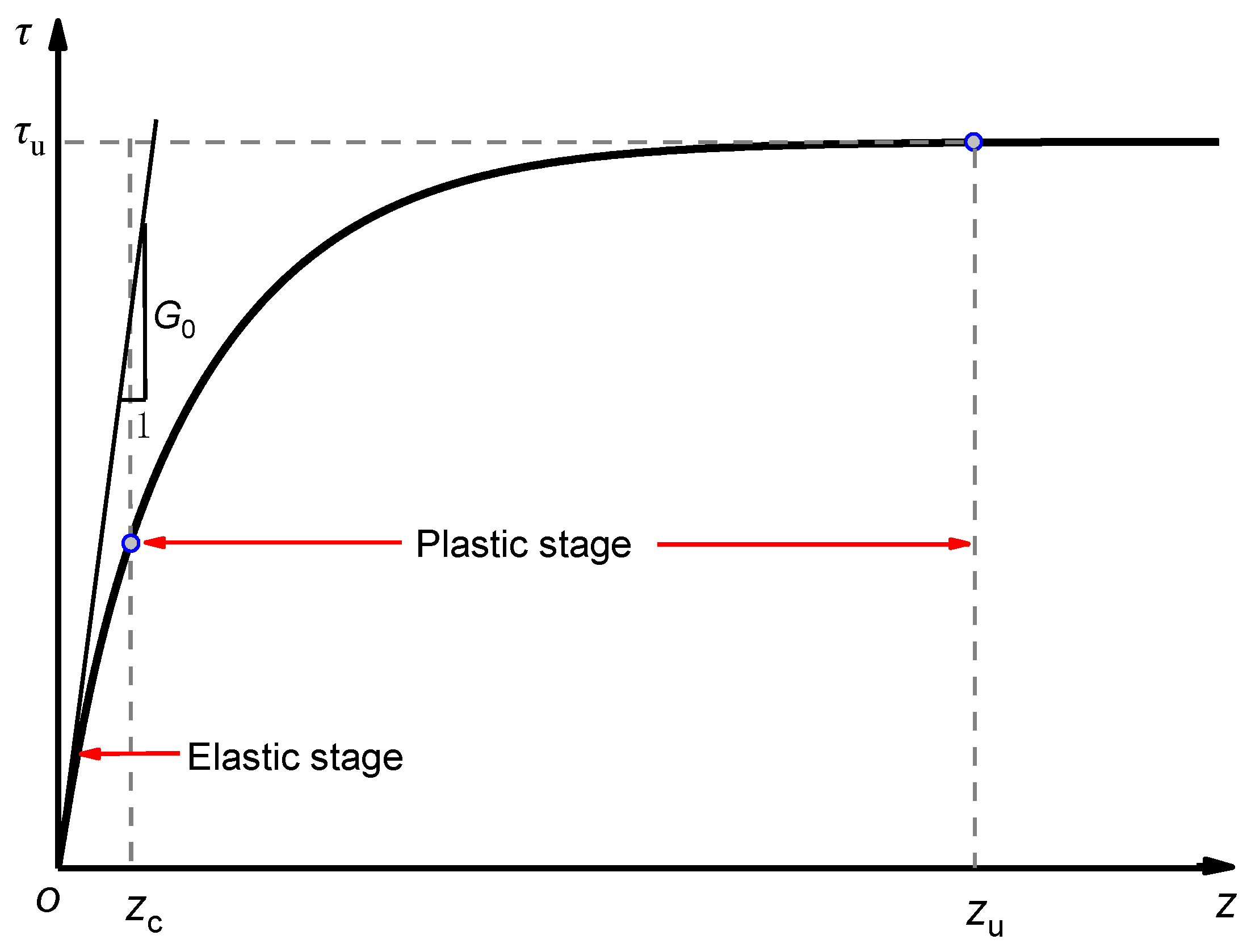

3. Load-Transfer Function Along Pile Side and Parameter Analysis

3.1. Load-Transfer Function Along Pile Side

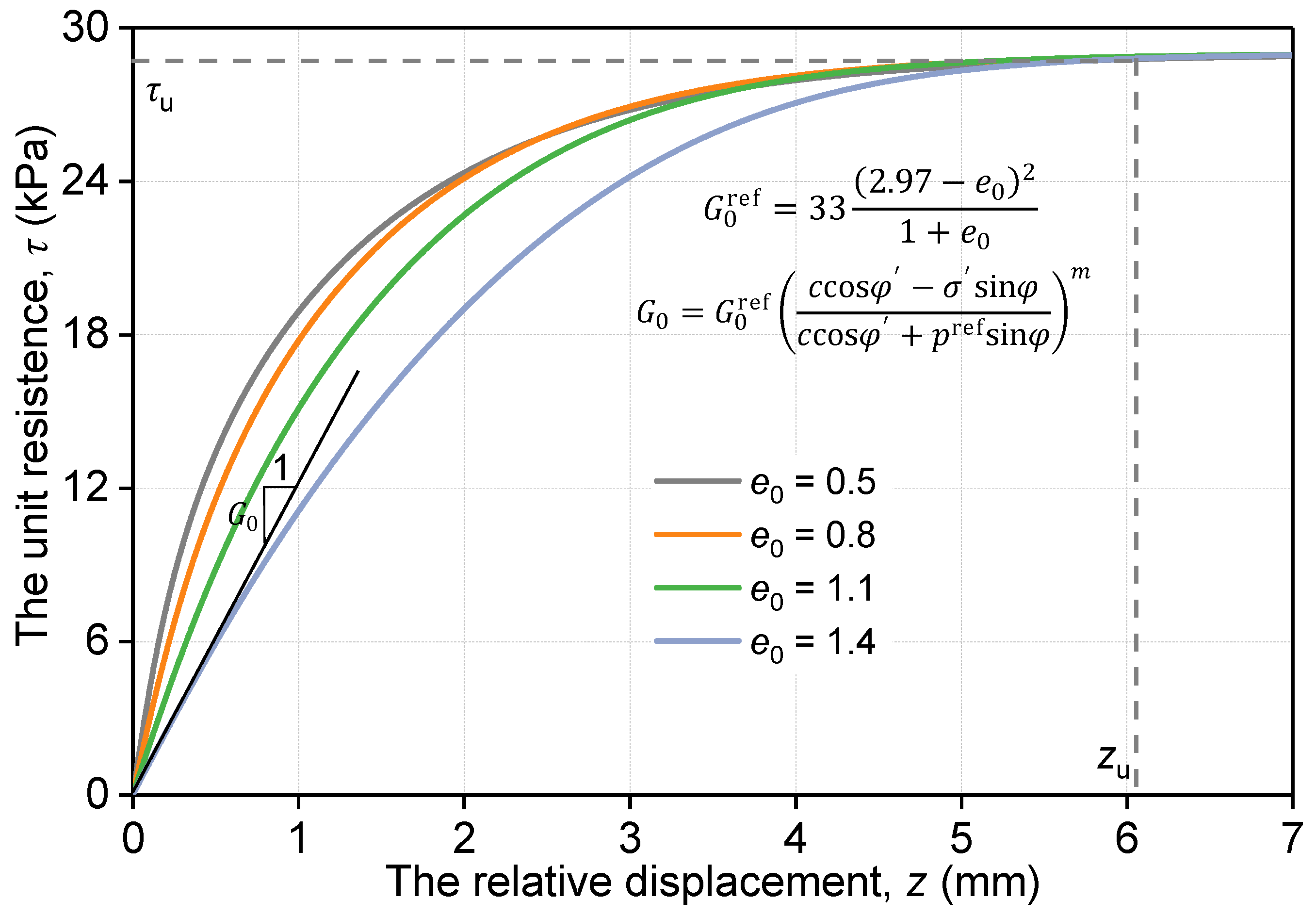

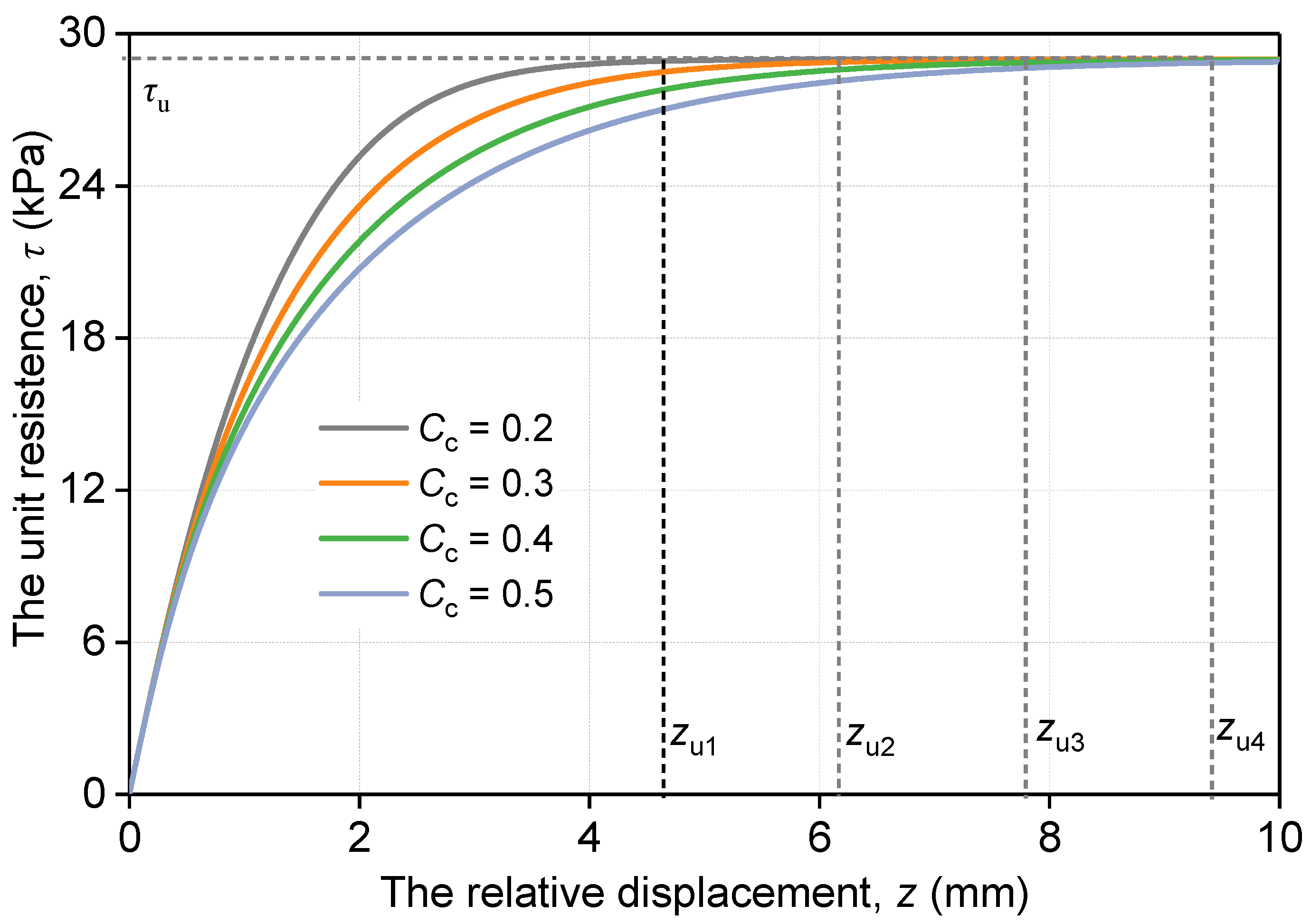

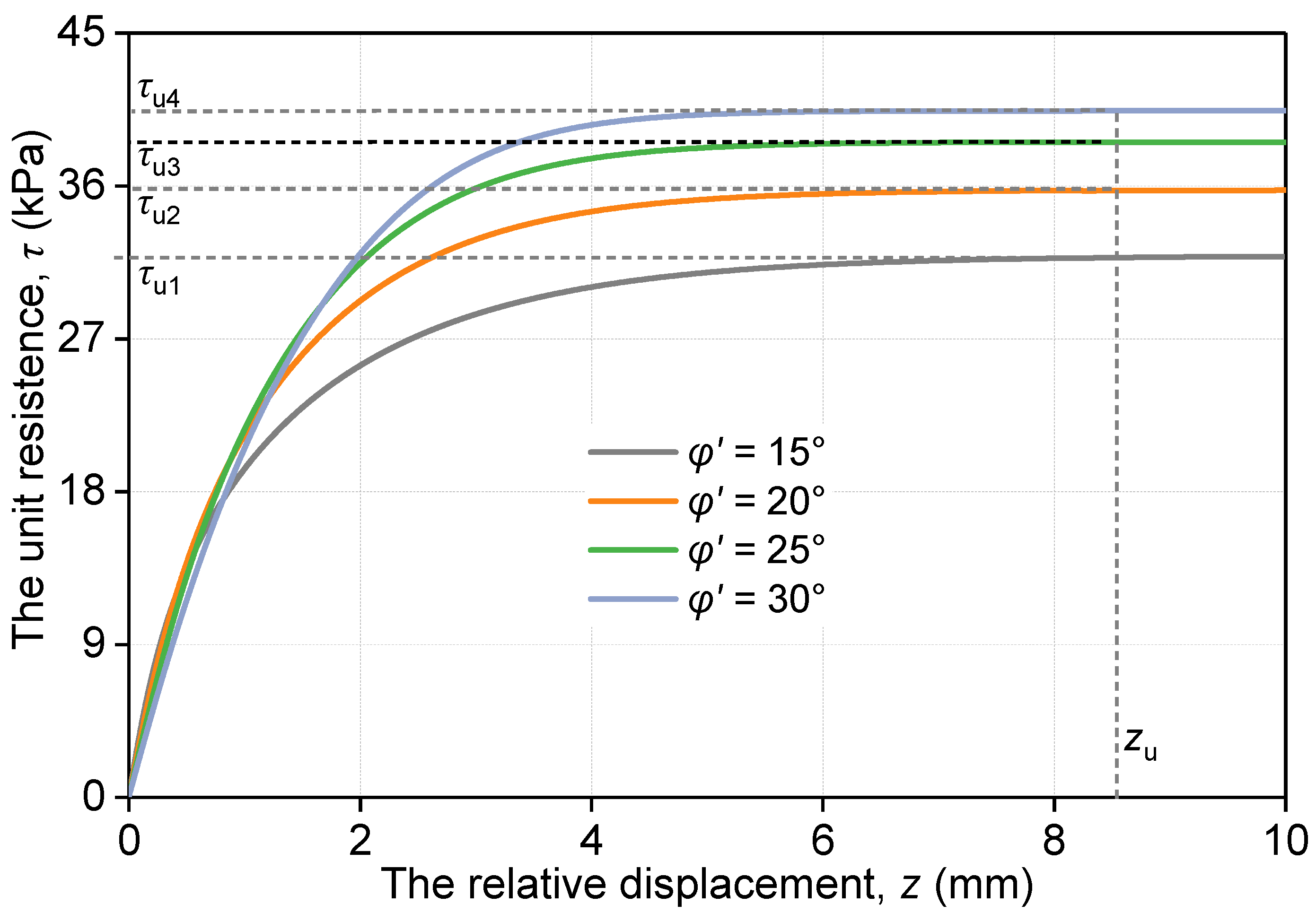

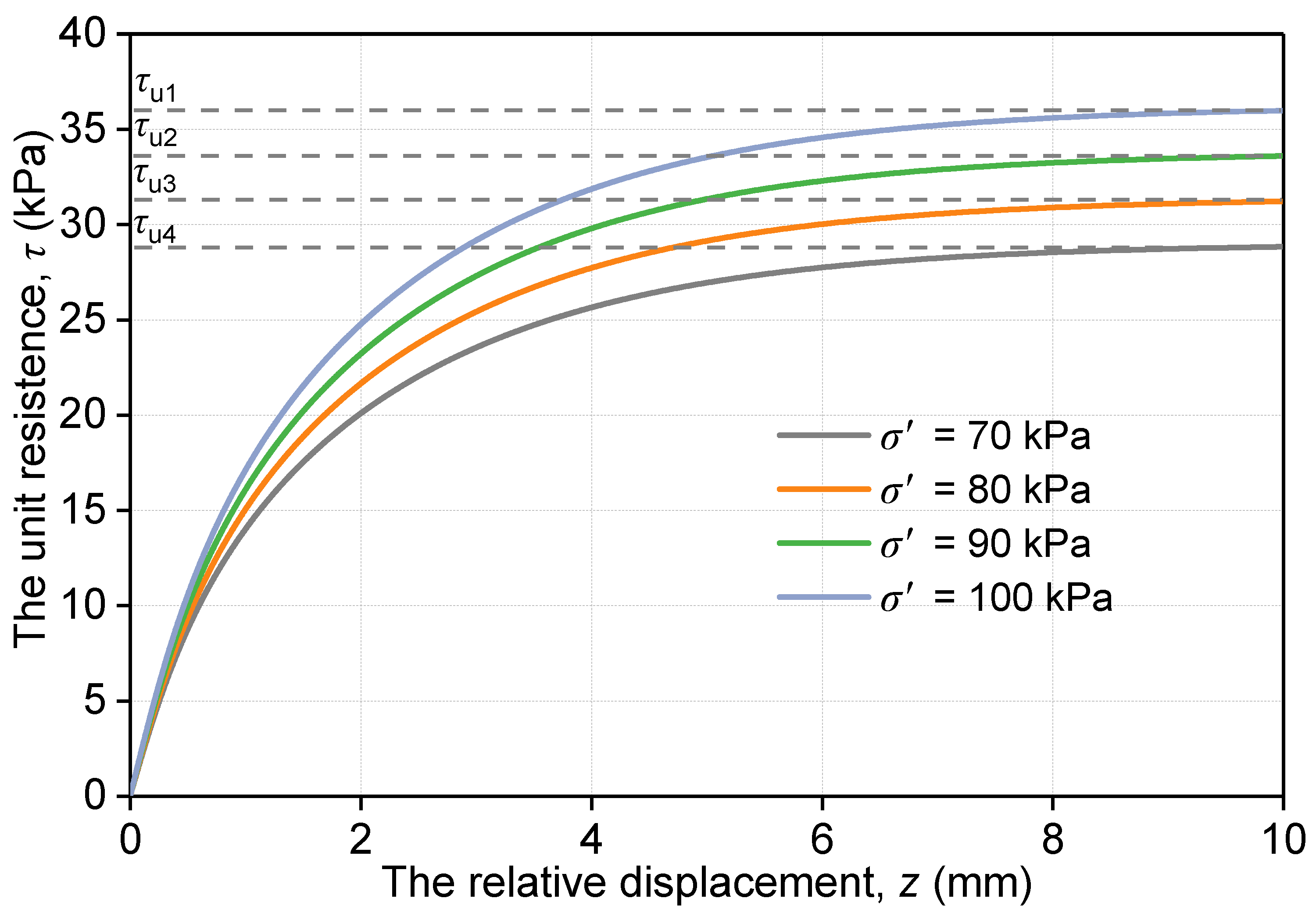

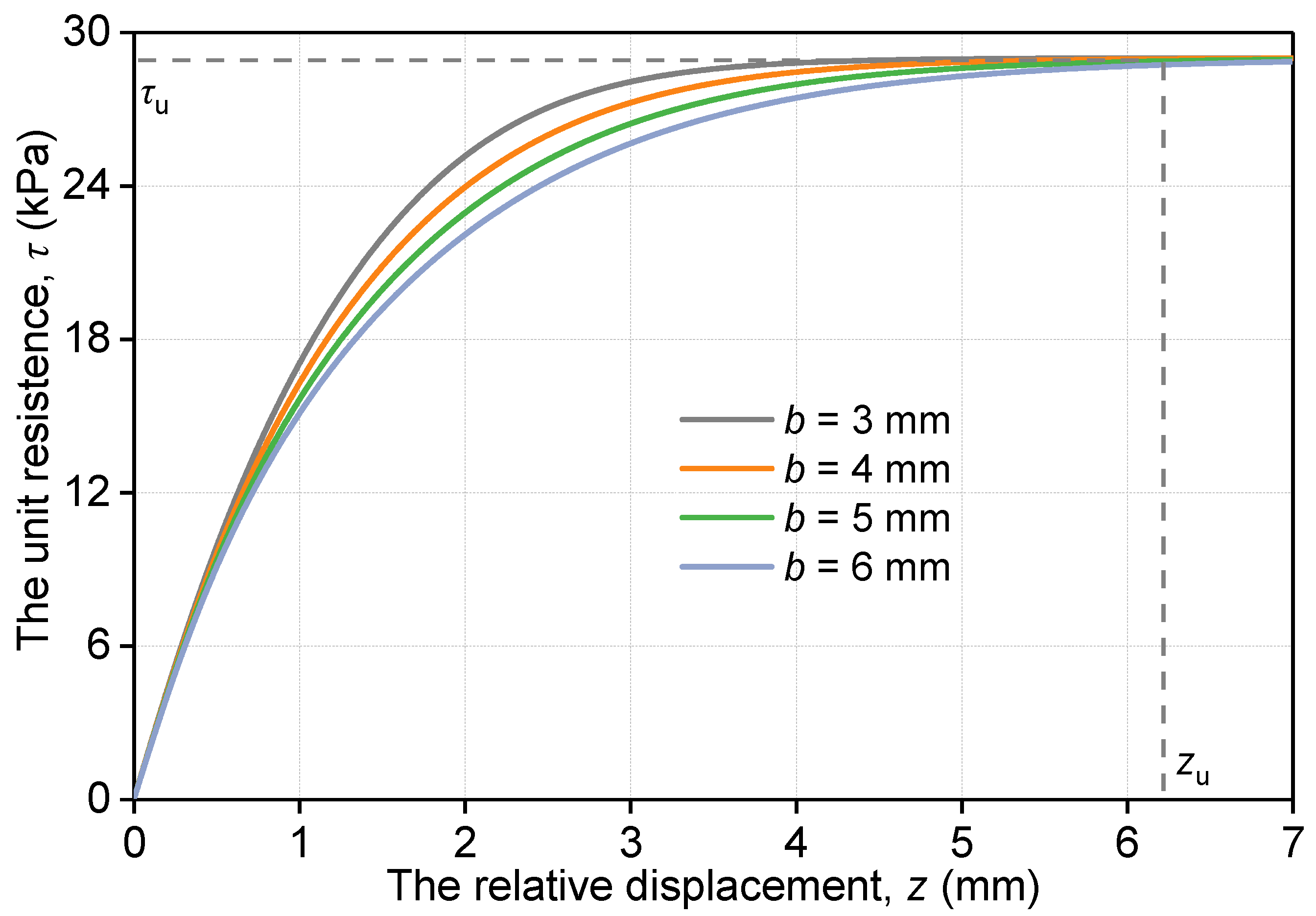

3.2. Parameter Analysis

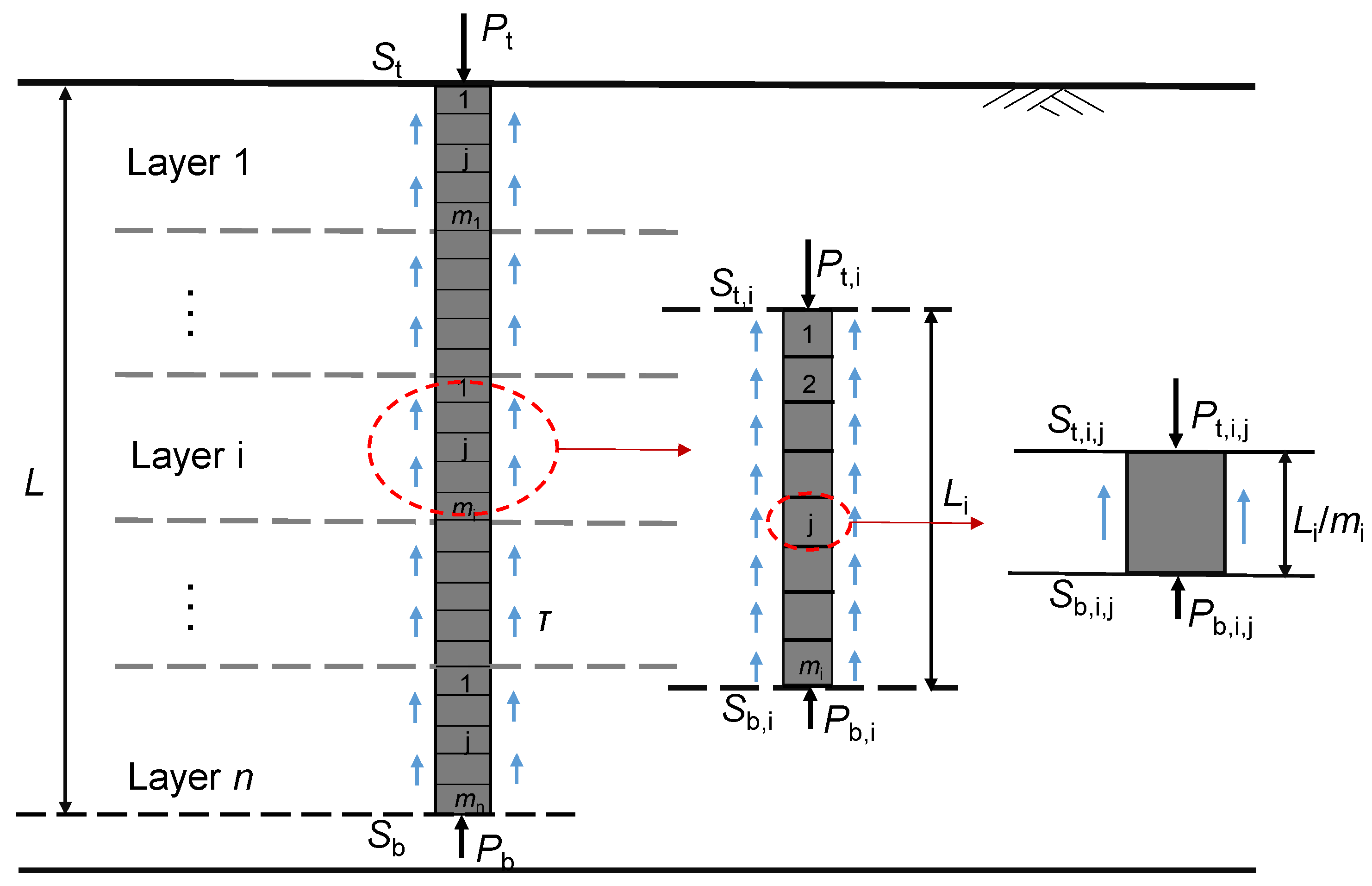

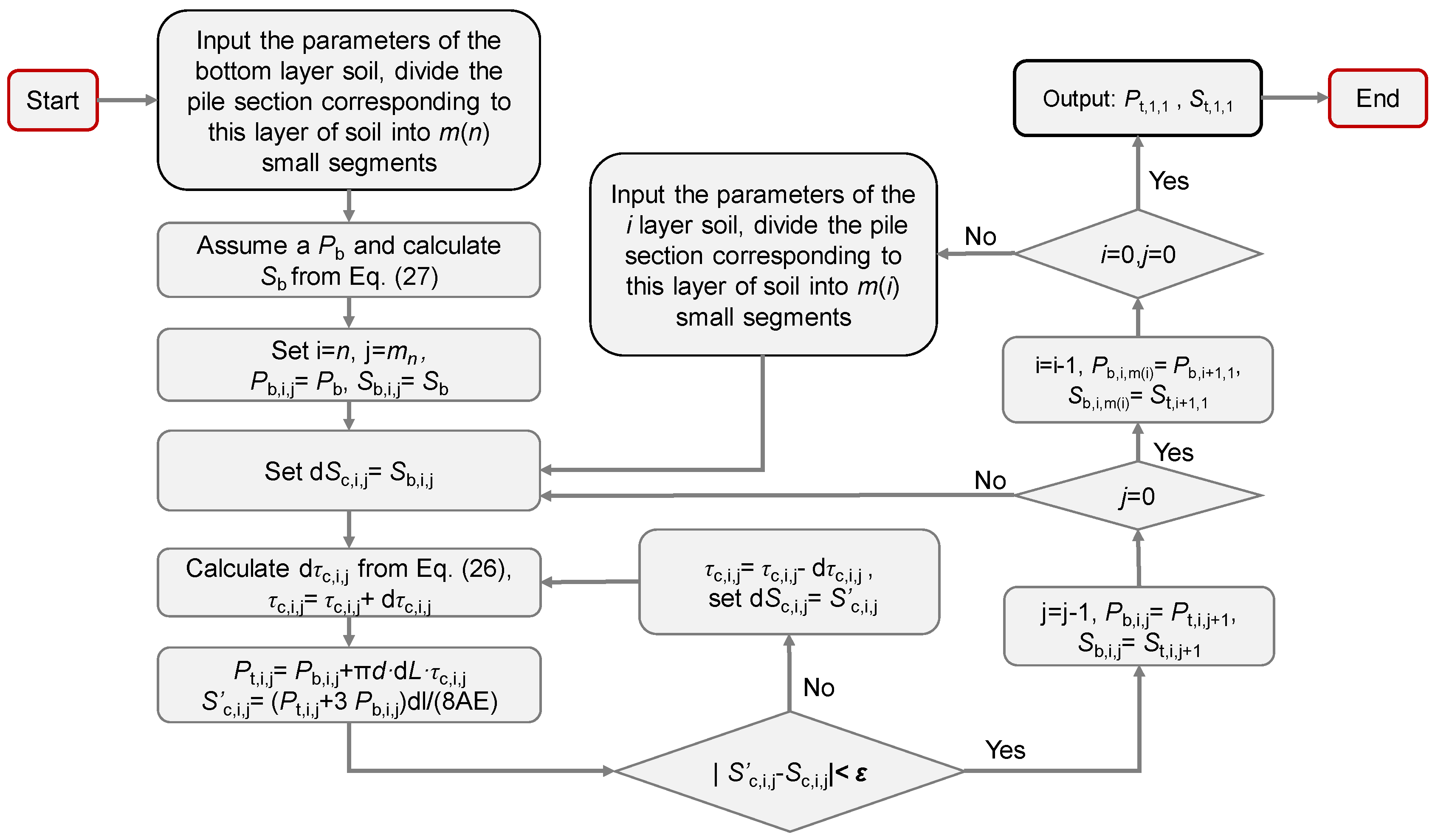

4. Iterative Algorithms for Load–Displacement Response of Single Pile

- Input the soil parameters of the lowest layer, and divide the pile segment corresponding to the lowest layer into n equal segments with the length of . If mn is large enough, the accuracy of the result can be guaranteed. The soil in the elastic zone is divided into x blocks along the radial direction, with the length of ;

- Assume a Pb and calculate Sb from Equation (27);

- Set , , , .

- Calculate the shear modulus and shear displacement corresponding to each small strip in the elastic zone from Equations (19)–(24);

- Set . Where represents the vertical displacement increment occurring at the midpoint of the j pile segment corresponding to the i layer of soil

- Calculate from Equation (26). and update the shear stress at the middle point of the pile section:

- Calculate the load at the top of the pile segment and the displacement at the middle point of the pile segment according to the load on the top and bottom of the pile segment and the elastic modulus of the pile shaft: ,

- Check if , where is an allowable error, e.g., m. If the discrepancy exceeds the specified tolerance, reset , repeat steps 6–8

- Update , and check if , set , repeat steps 5–9.

- Update , and check if , set , input the soil parameters of the i layer soil, and divide the pile segment corresponding to the i layer soil into n equal segments with the length of Limi. Repeat steps 5–10.

- Output , , set = , =

- Repeat steps 1–11 with a group of Pb to obtain the load–displacement curve of a single pile.

5. Model Validation

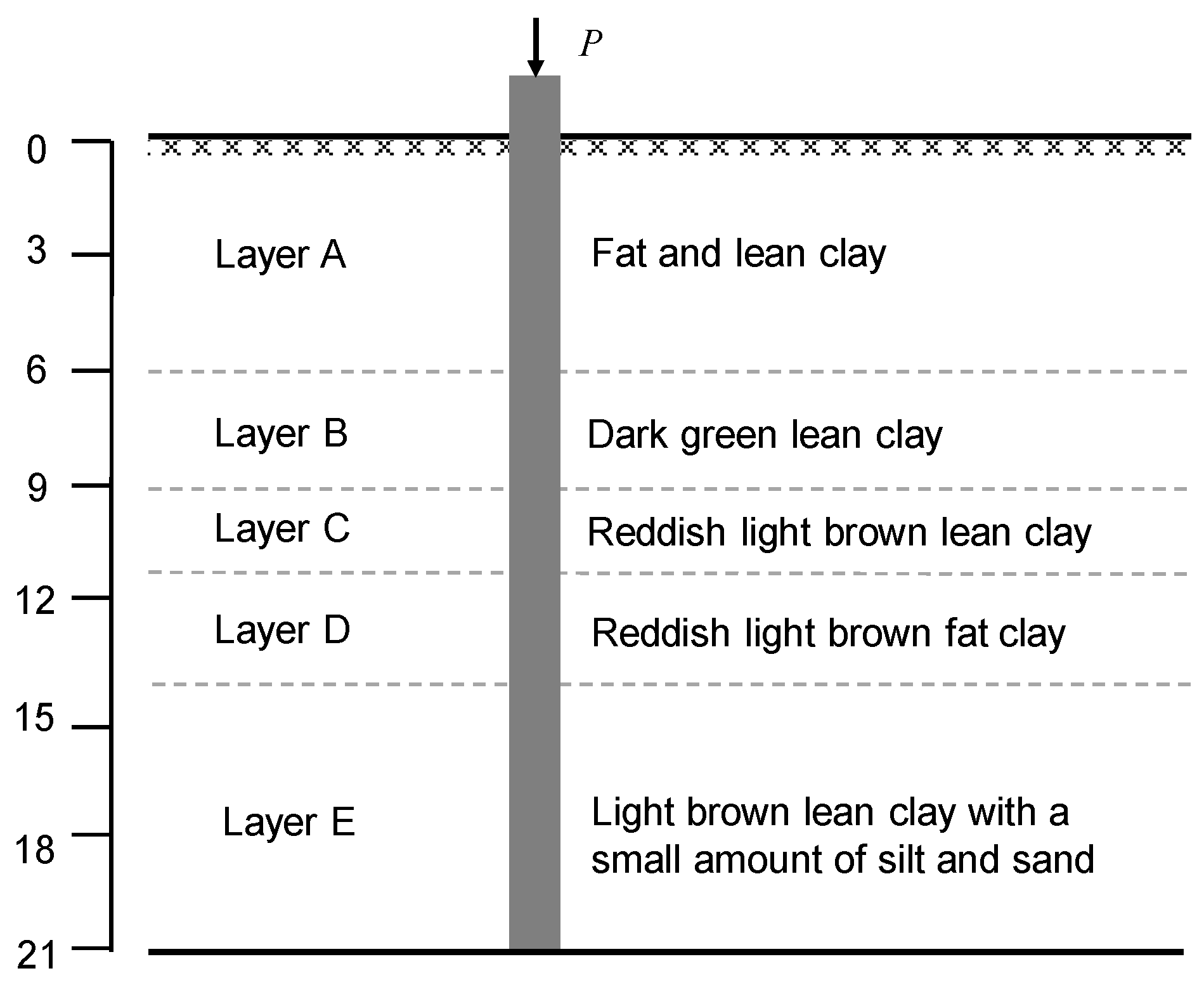

5.1. Case 1: Pile in Louisiana Soft Soil

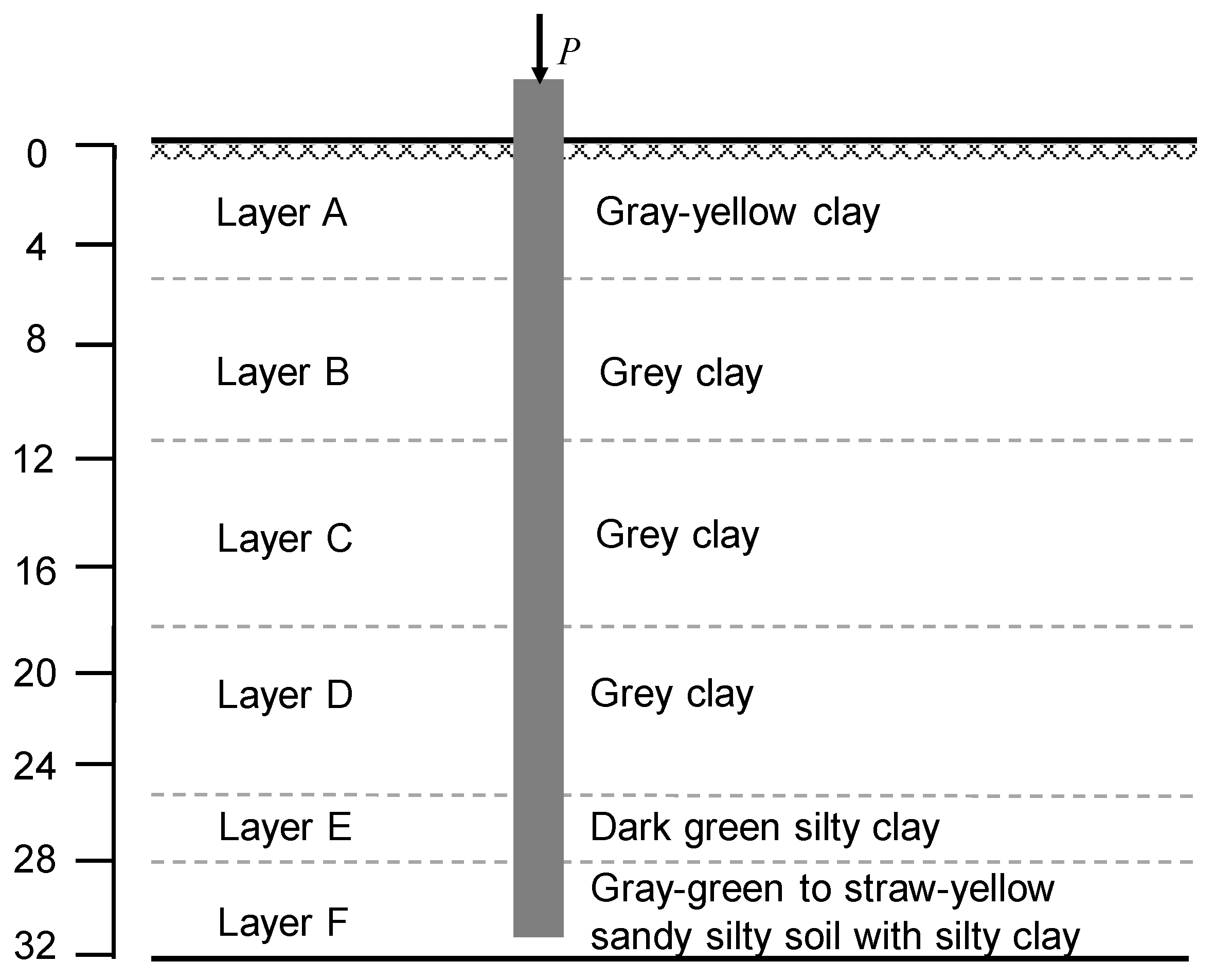

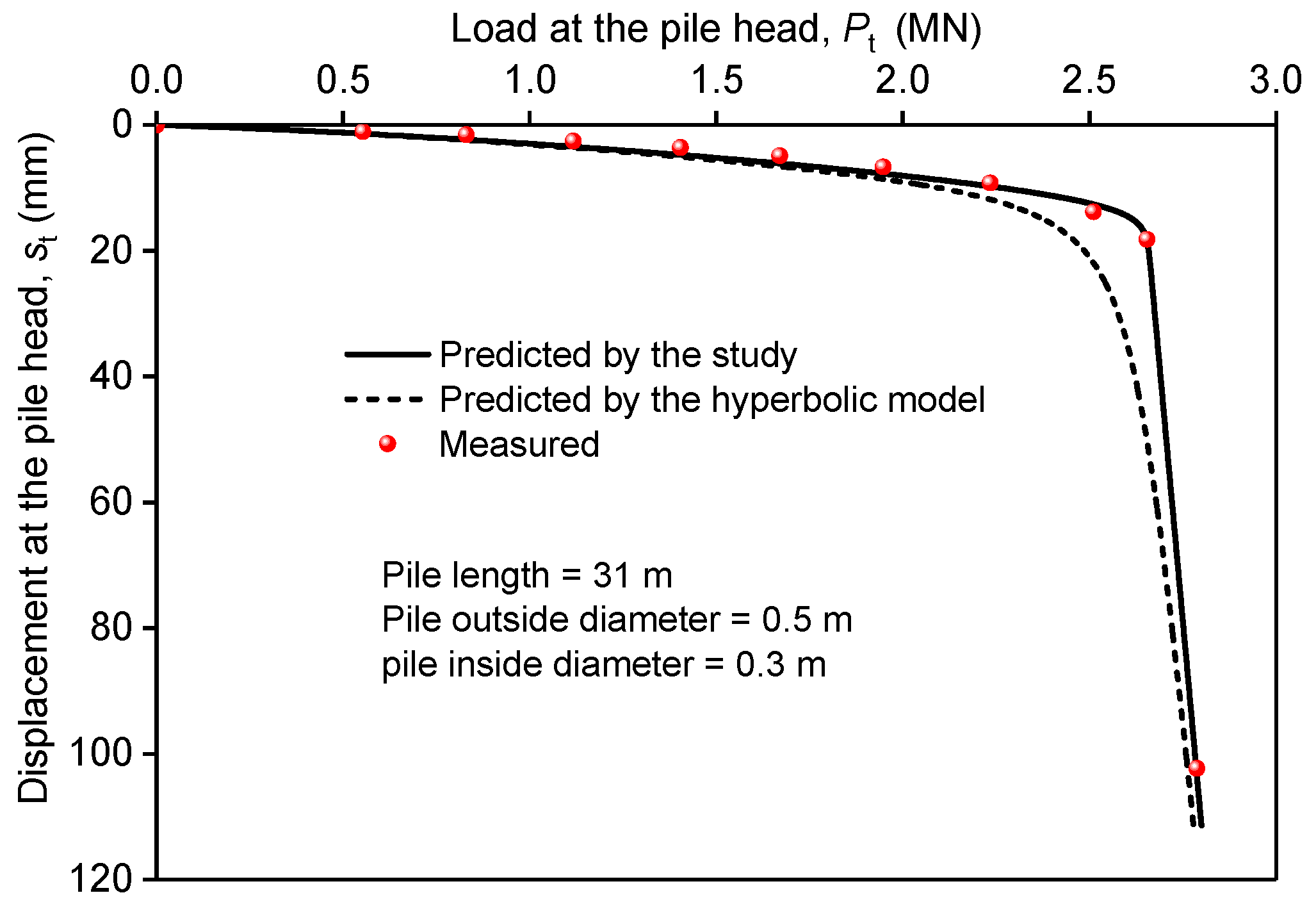

5.2. Case 2: Pile in Shanghai Soft Soil

6. Summary and Conclusions

- The parameter φ′ primarily influences the ultimate unit resistance, while the parameters Cc, Cs, and b mainly influence the phase of rising shear stress in the τ − z curve.

- The Parameter e0, by influencing G0, has a significant effect on the initial slope of the τ − z curve. The validating results indicated that the model can represent the elastoplastic load–displacement curve of a single pile very well.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivations for the Scalar Multiplier Λ and the Determination of dεne and dετe

References

- Coyle Harry, M.; Reese Lymon, C. Load Transfer for Axially Loaded Piles in Clay. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1966, 92, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Prezzi, M.; Salgado, R.; Chakraborty, T. Shaft resistance and setup factors for piles jacked in clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2014, 140, 04013026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, M.Y.; Rosti, F.; Souri, A. Evaluating pile installation and subsequent thixotropic and consolidation effects on setup by numerical simulation for full scale pile load tests. Can. Geotech. J. 2015, 52, 1734–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z. A numerical study on installation effects and long-term shaft resistance of pre-bored piles in cohesive soils. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zhong, H.; Zhu, Z. Development of a large shaking table test for sand liquefaction analysis. Lithosphere 2024, 2024, lithosphere_2024_137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, H.G.; Davis, E.H. Pile Foundation Analysis and Design; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 397, pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mandolini, A.; Viggiani, C. Displacement of piled foundations. Géotechnique 1997, 47, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.Y.; Cheng, Y.C. Analysis of vertically loaded piles in multilayered transversely isotropic soils by BEM. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2013, 37, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.Y.; Han, J. Boundary element analysis of axially loaded piles embedded in a multi-layered soil. Comput. Geotech. 2009, 36, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basack, S.; Sen, S. Numerical solution of single pile subjected to simultaneous torsional and axial loads. Int. J. Geomech. 2014, 14, 06014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Song, Z. BEM analysis of the interaction factor for vertically loaded dissimilar piles in saturated poroelastic soil. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 62, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.G.K. A new method for single pile settlement prediction and analysis. Géotechnique 1992, 42, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; XIao, Z.R. A simplified nonlinear approach for pile group settlement analysis in multilayered soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Zhang, Z.M.; He, J.Y. A simplified approach for settlement analysis of single pile and pile groups considering interaction between identical piles in multilayered soils. Comput. Geotech. 2010, 37, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.F.; Zhang, J.X.; Liu, X.; Geng, H.S.; Li, K.L.; Yang, Y.H. Analytical Model and Back-Analysis for Pile-Soil System Behavior under Axial Loading. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1369348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Wu, K.; Lu, T. Analysis on response of a single pile subjected to tension load considering excavation effects. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Zhang, Z.M. A simplified nonlinear approach for single pile settlement analysis. Can. Geotech. J. 2012, 49, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Sun, D.A.; Gong, W. Semi-analytical approach for time-dependent load-settlement response of a jacked pile in clay strata. Can. Geotech. J. 2017, 54, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.W. The settlement of friction pile foundations. In Proceedings of the Conference on Tall Buildings, Jakarta, Indonesia, 9–11 December 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph, M.F.; Wroth, C.P. Analysis of deformation of vertically loaded piles. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1978, 104, 1465–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, L.M., Jr.; Ray, R.P.; Kagawa, T. Theoretical t-z curves. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1981, 107, 1543–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.D.; Randolph, M.F. Vertically loaded piles in non-homogeneous media. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1997, 21, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.D. Vertically loaded single piles in Gibson soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2000, 126, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, G.; Gazetas, G. Settlement and additional internal forces of grouped piles in layered soil. Géotechnique 1998, 48, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; Wang, J. A new nonlinear method for vertical settlement prediction of a single pile and pile groups in layered soils. Comput. Geotech. 2012, 45, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chang, M.F. Load transfer curves along bored piles considering modulus degradation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2002, 128, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Chen, Q.; Huang, M.; Basack, S. Hybrid approach for rigid piled-raft foundations subjected to coupled loads in layered soils. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibreza, Z.; Ghazavi, M.; El Naggar, M.H. Load-Settlement Analysis of Axially Loaded Piles in Unsaturated Soils. Water 2024, 16, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Gu, X.; Zhang, X. Coupling fabric evolution with critical state in DEM simulations of sand liquefaction. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2026, 200, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, F.S.; Han, F.; Salgado, R.; Prezzi, M.; Tovar, R.D.; Castro, A.G. Effect of surface roughness on the shaft resistance of non-displacement piles embedded in sand. Géotechnique 2016, 66, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejong, J.T.; White, D.J.; Randolph, M.F. Microscale observation and modeling of soil-structure interface behavior using particle image velocimetry. Soils Found. 2006, 46, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lai, N.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, T.; Su, Z. A generalized elastoplastic load-transfer model for axially loaded piles in clay: Incorporation of modulus degradation and skin friction softening. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, N.R.; Tchalenko, J.S. Microscopic structures in kaolin subjected to direct shear. Géotechnique 1967, 17, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V. Strain Localization in Sensitive Soft Clays. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine, R.J.; Potts, D.M.; Fourie, A.B.; Burland, J.B. Studies of the influence of non-linear stress–strain characteristics in soil–structure interaction. Géotechnique 1986, 36, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.J.M. Assessment of ground stiffness from field and laboratory tests. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on SMFE, Florence, Italy, 26–30 May 1991; Volume 1, pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, C.S.; Abramento, M. Pressuremeter tests on gneissic residual soil in Sao Paulo 1999, Brazil. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Hamburg, Germany, 8–12 August 1999; pp. 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkgreve, R.B.J.; Kumarswamy, S.; Swolfs, W.M.; Waterman, D.; Chesaru, A.; Bonnier, P.G. PLAXIS 2016; PLAXIS BV: Delft, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y. Displacement of pile group-practical approach. J. Geotech. Eng. 1993, 119, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Abu-Farsakh, M.Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z. Case study on instrumenting and testing full-scale test piles for evaluating setup phenomenon. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2462, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Method Category | Assumption |

|---|---|---|

| Coyle & Reese [1] | Load-transfer method | Elastic pile discretization, nonlinear soil springs |

| Randolph & Wroth [20] | Theoretical derivation | Concentric cylinder idealization, elastic soil deformation |

| Kraft et al. [21] | Theoretical derivation | Elastic–plastic transition, tangent modulus correction |

| Zhu & Chang [26] | Theoretical and Curve fitting | Modulus degradation, nonlinear elasticity |

| Wang et al. [25] | Curve fitting | Elastic soil deformation, exponential friction–displacement relation |

| Layer | Depth (m) | C′ (kPa) | φ′ (°) | Cc | Cs | e0 | OCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0–6 | 10 | 24 | 0.1798 | 0.0300 | 0.74 | 2.3 |

| B | 6–9 | 9 | 26 | 0.1798 | 0.0300 | 0.57 | 2.0 |

| C | 9–11 | 9 | 28 | 0.1798 | 0.0300 | 0.65 | 1.8 |

| D | 11–14 | 10 | 23 | 0.1291 | 0.0437 | 0.60 | 1.4 |

| E | 14–21 | 9 | 20 | 0.2143 | 0.0322 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| Layer | Depth (m) | c’ (kPa) | φ’ (°) | Cc | γ’ (kN/m3) | Cs | e0 | OCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–5.3 | 14 | 24 | 0.2399 | 9.49 | 0.0310 | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| 2 | 5.3–11.2 | 12 | 25 | 0.2533 | 8 | 0.0327 | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| 3 | 11.2–18 | 9 | 20 | 0.2287 | 6.7 | 0.0325 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| 4 | 18–25.6 | 11 | 26 | 0.2917 | 8.1 | 0.0332 | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| 5 | 25.6–28 | 12 | 23 | 0.2291 | 7.9 | 0.0331 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| 6 | 28–31 | 10 | 22 | 0.2328 | 8.2 | 0.0290 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Li, L. An Elastoplastic Theory-Based Load-Transfer Model for Axially Loaded Pile in Soft Soils. Buildings 2025, 15, 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234300

Xiu Y, Liu H, Zhang D, Han X, Li L. An Elastoplastic Theory-Based Load-Transfer Model for Axially Loaded Pile in Soft Soils. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234300

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiu, Yijun, Haoyu Liu, Denghong Zhang, Xingbo Han, and Lin Li. 2025. "An Elastoplastic Theory-Based Load-Transfer Model for Axially Loaded Pile in Soft Soils" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234300

APA StyleXiu, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, D., Han, X., & Li, L. (2025). An Elastoplastic Theory-Based Load-Transfer Model for Axially Loaded Pile in Soft Soils. Buildings, 15(23), 4300. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234300