Data-Driven Assessment and Renewal Strategies for Public Space Vitality in Aged Residential Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Technical Weaknesses in Diagnostic Tools: Inefficient, Manual Data Collection: The quantification of spatial elements relies on labor-intensive manual interpretation, which is not easily replicable for large-area studies. Over-reliance on Subjective Evaluation: Prevailing assessment frameworks lack objectivity, being prone to perceptual biases that obscure the root causes of spatial problems. Isolated, Non-Systemic Analysis: The prevailing approach focuses on renovating individual spaces in isolation, lacking a systematic logic for district-wide prioritization and intervention.

- (2)

- Resulting Practical Problems: These technical weaknesses indirectly lead to the persistent, on-the-ground issues observed in aged residential areas: a general lack of spatial vitality, an imbalance in functional configuration, and systematic deficiencies in critical areas such as accessibility and ecological quality. The core challenge is a fundamental disconnect between outdated diagnostic methods and the complex, systemic nature of the problems they are meant to solve.

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

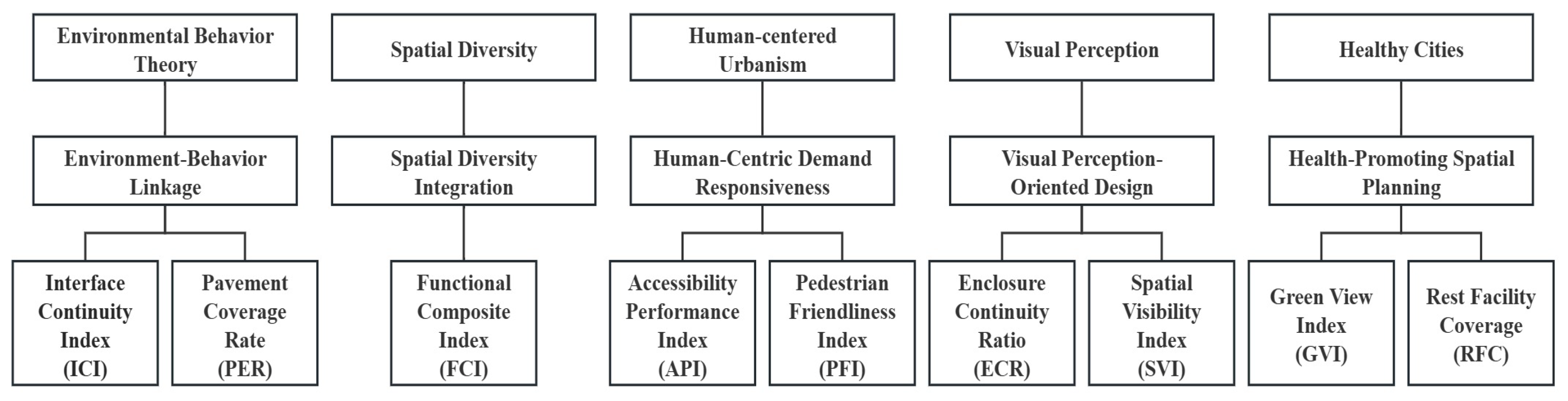

3.1. Spatial Quality Evaluation Indicator System

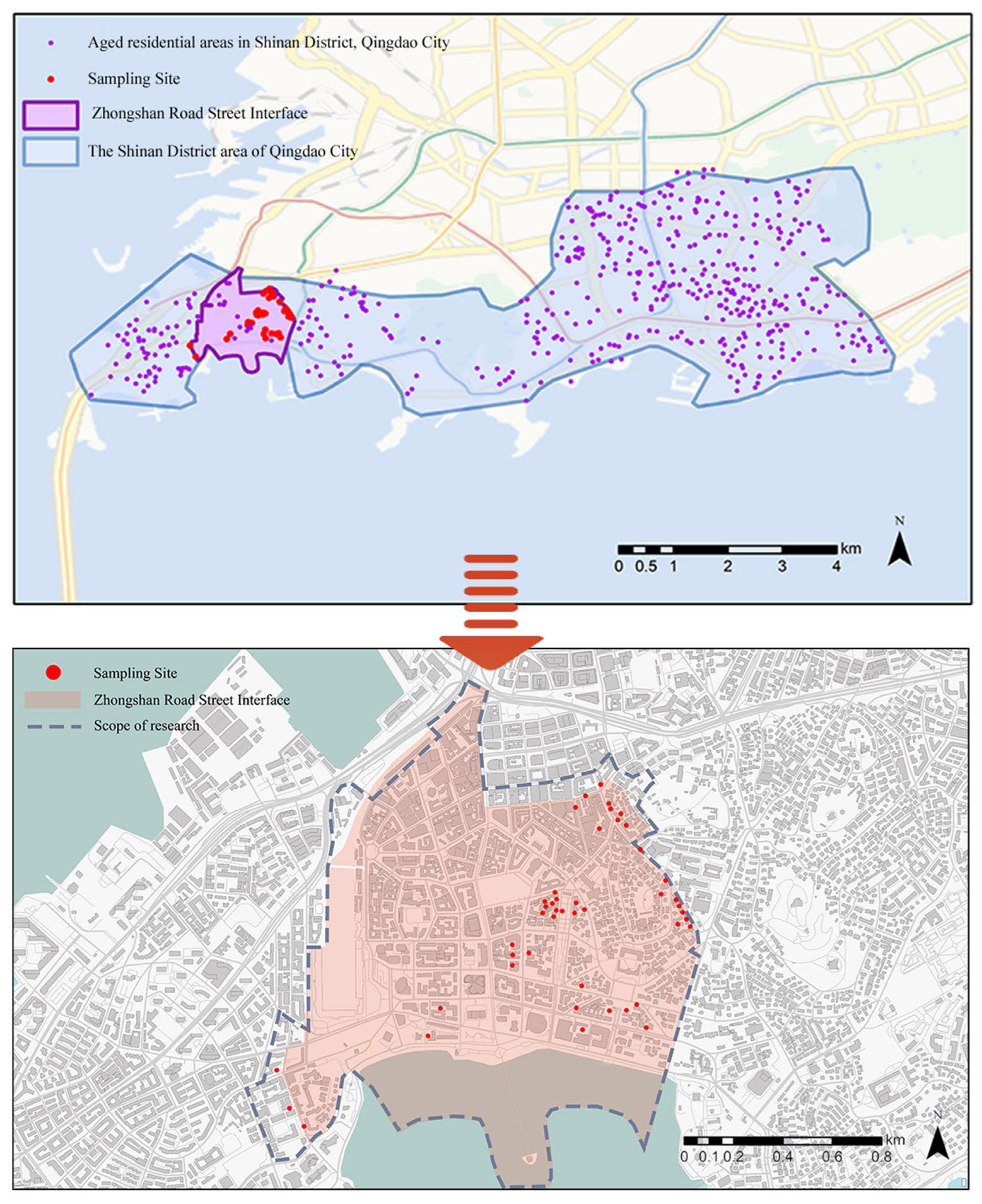

3.2. Study Area and Data Source

3.3. Technical Workflow

- (1)

- Panoramic data collection

- (2)

- FCN-based semantic segmentation

- (3)

- Quantitative calculation of public space quality

- (4)

- Analysis of spatial quality indicator results

4. Results

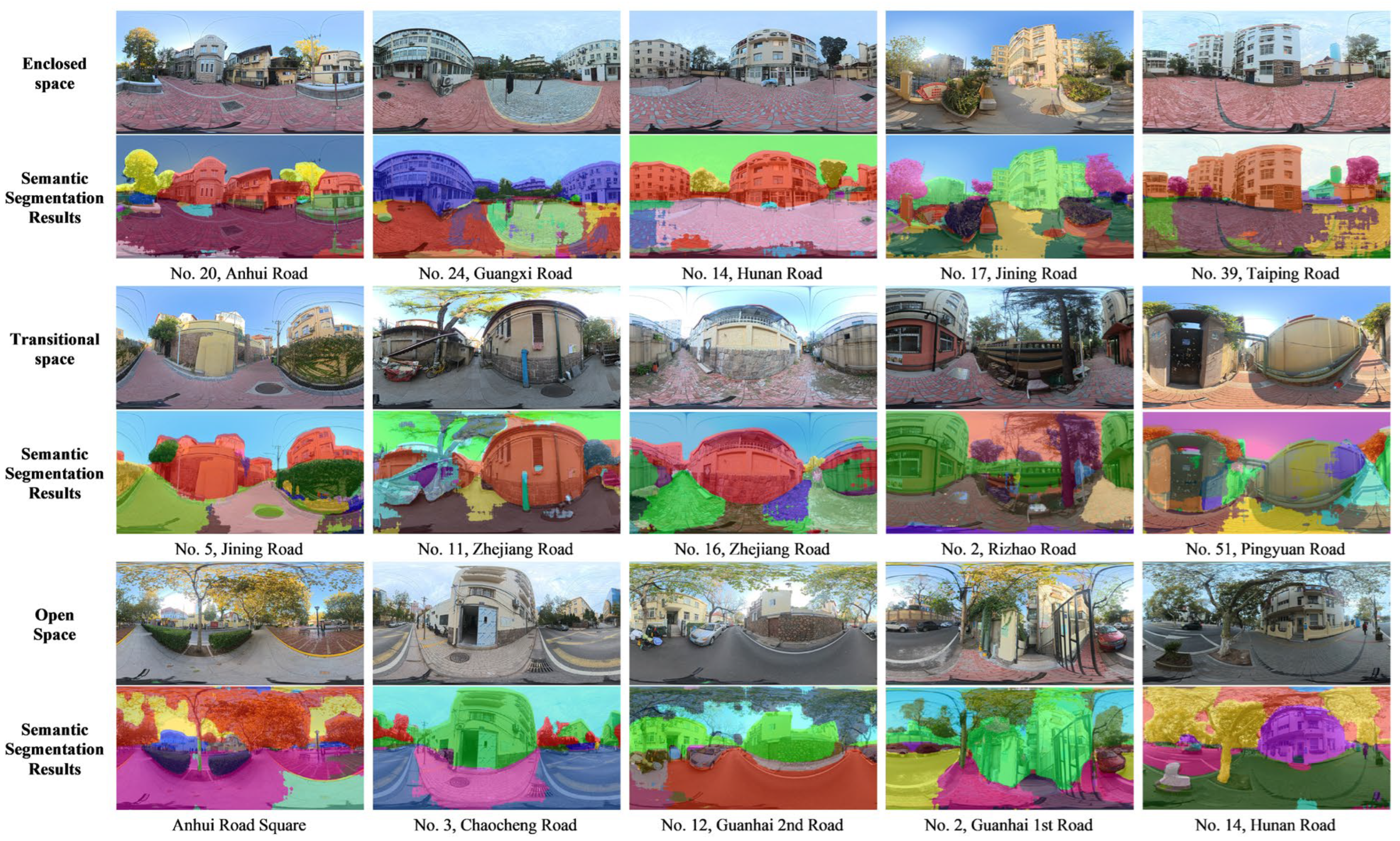

4.1. Characterization of Public Space Forms

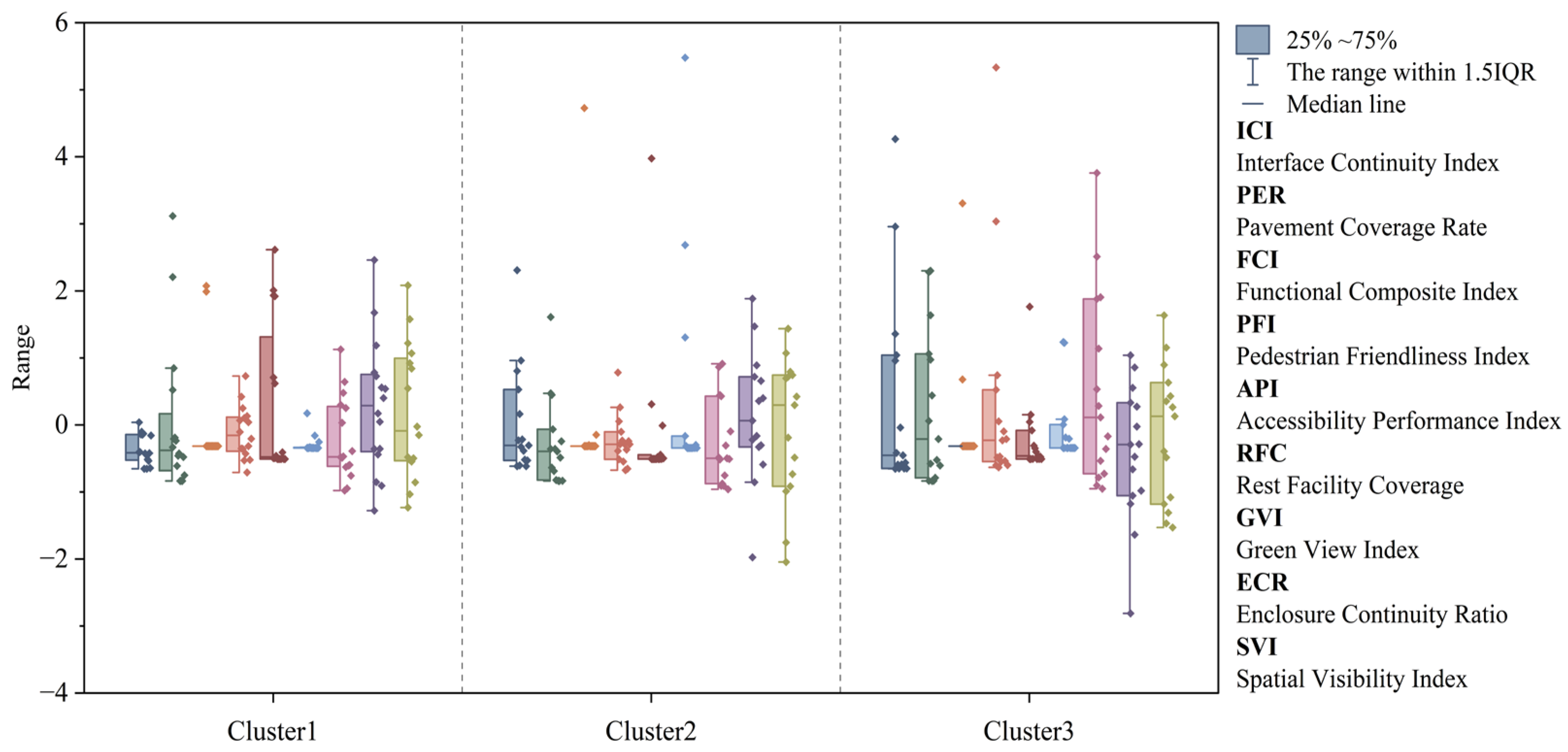

- (1)

- Enclosed Spaces were characterized by high ECR and low RFC. API performance was also notable.

- (2)

- Transitional Spaces demonstrated high RFC, but low GVI and the lowest API among the three types.

- (3)

- Open Spaces showed high PFI and GVI, but low API and the lowest ECR.

4.2. Public Space Quality Evaluation Model

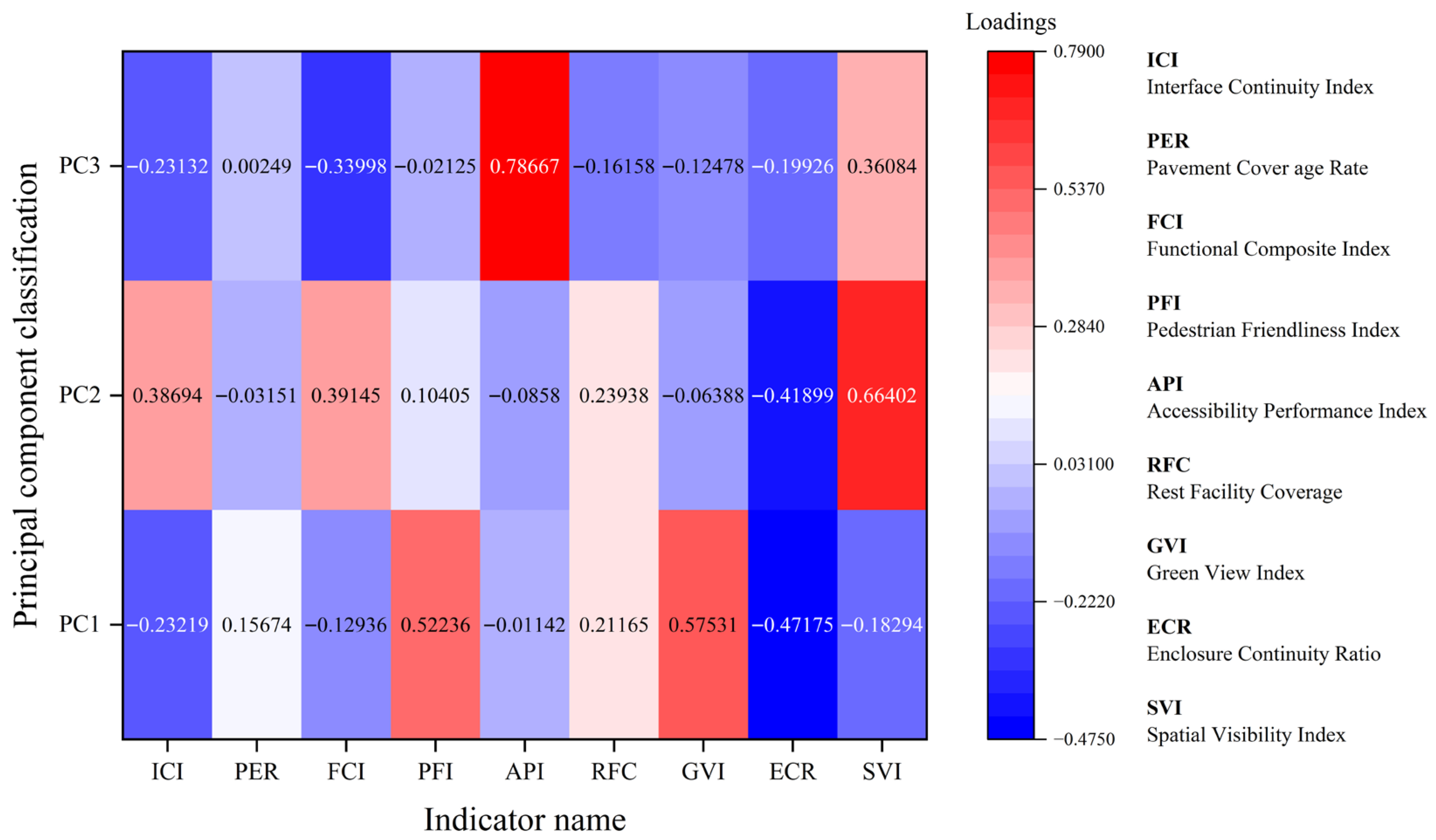

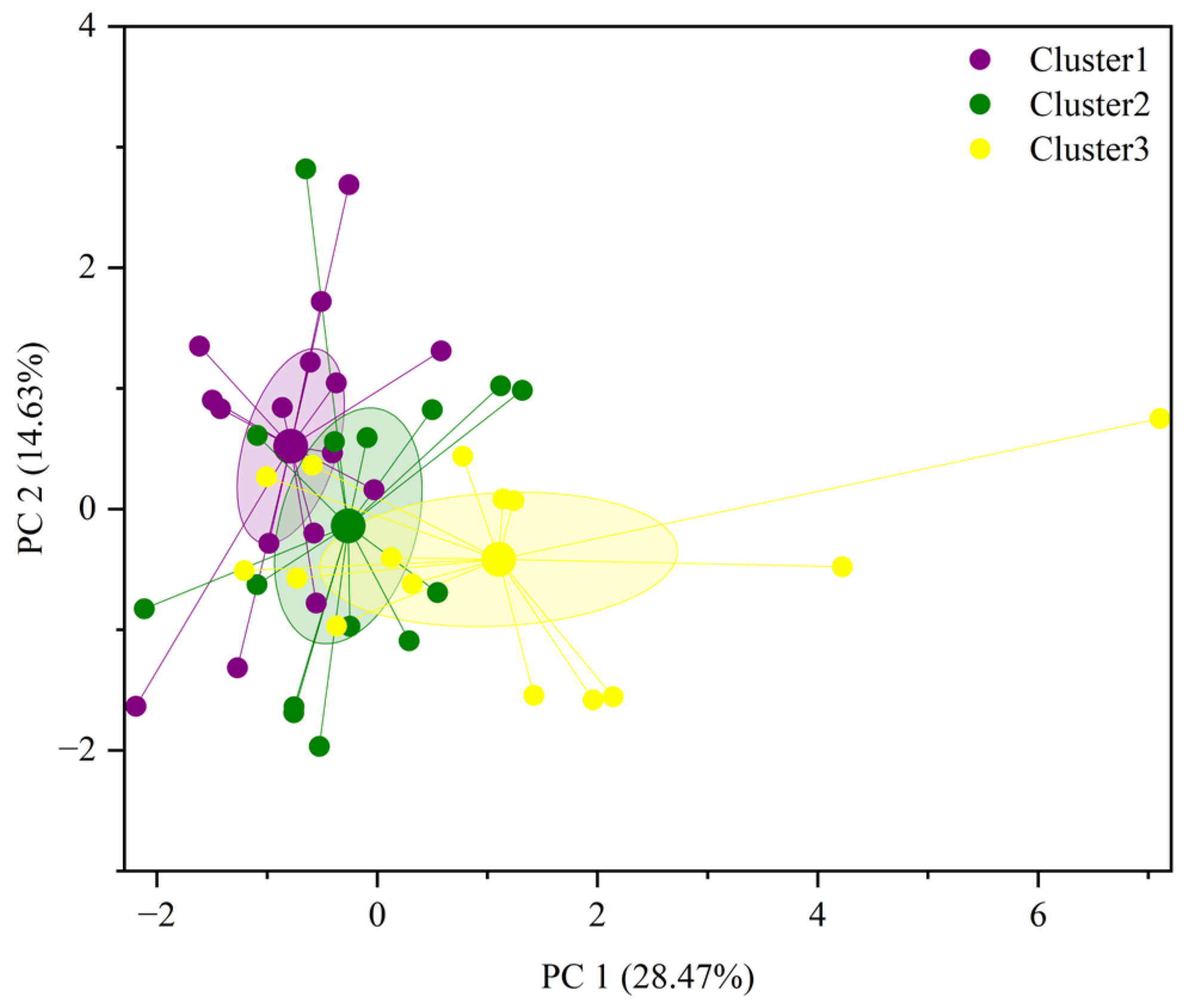

4.2.1. Principal Component Analysis

- (1)

- PC1 (27.3% of variance) was characterized by positive loadings on ECR and negative loadings on GVI, framing a primary axis of variation between spatial enclosure and ecological elements.

- (2)

- PC2 (14.9% of variance) was defined by a positive loading on the SVI, corresponding to a dimension of visual openness.

- (3)

- PC3 (12.7% of variance) was marked by a positive loading on the API, highlighting a dimension of age-friendly accessibility.

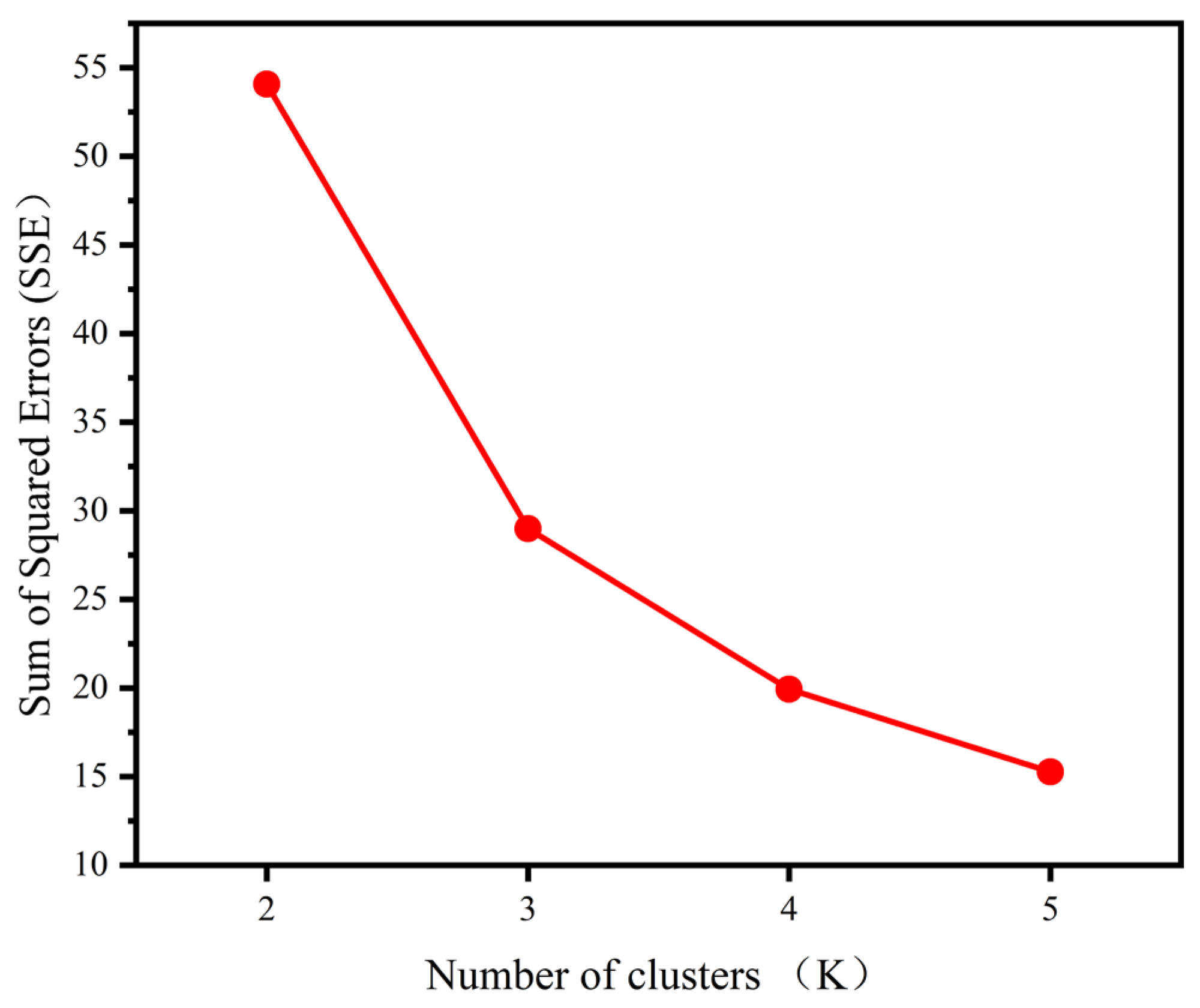

4.2.2. K-Means Clustering

5. Discussion

5.1. The Interplay Between Morphological Classification and Data-Driven Analytics

5.2. Interpreting Core Structural Contradictions

5.2.1. The Ecological-Enclosure Trade-Off (PC1)

5.2.2. The Domain Perception Imbalance (PC2)

5.2.3. Systemic Deficits in Age-Friendliness (PC3)

5.3. Informing Differentiated Renewal Strategies

5.4. Synthesis and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The multi-dimensionality of contradictions requires classified governance. The public spaces in aged residential areas generally have complex problems, such as an imbalance between ecological benefits and functional allocation, insufficient age-friendly facilities, and a decline in spatial vitality. Systematic diagnosis is needed to achieve precise governance. For Enclosed Spaces, priority should be given to addressing ecological isolation and mitigating heat island effects through vertical greening and the use of high-albedo materials. For Open Spaces, a balance between openness and a sense of belonging should be maintained, coupled with the installation of shade structures and permeable paving to enhance thermal comfort. For Transitional Spaces, the focus should be on making up for the facilities’ shortcomings and improving microclimatic conditions by introducing ventilation corridors and shade-providing vegetation.

- (2)

- Human–machine collaboration enhances the scientific nature of decision-making. The semantic segmentation of FCN, the analysis of spatial contradictions by PCA and K-means clustering are integrated for verification to construct a full-chain framework of “data collection-element interpretation-strategy generation”, which improves the diagnostic efficiency compared with traditional methods, breaks through the subjective limitations of traditional evaluation, and provides a humanized basis for the improvement of spatial quality.

- (3)

- The practical framework can be replicated and promoted. The research results support the renewal practice of Zhongshan Road Sub-district in Qingdao City, verify the feasibility of data-driven technology in urban renewal, and provide standardized analysis tools and differentiated renewal paths for the public spaces renovation of aged residential areas in similar cities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Z.; Yan, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wei, R.; Wu, T.; Geng, X. Top Ten Key Issues in Urban and Rural Planning Discipline Development (2024–2025). Urban Plan. Forum 2024, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Jin, Y. Performance Evaluation of Public Open Spaces in Community Life Circles: A Case Study of Central Shanghai. Mod. Urban Res. 2018, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning. (2023, March 10). Qingdao Urban Renewal Special Plan (2021–2035). Available online: http://zrzygh.qingdao.gov.cn/zxfw/zrzyghggzyxx/ghgl/ghcajpzjg/zxgh/202303/t20230310_7043945.shtml (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Qingdao Municipal People’s Government. (2025, January 7). Qingdao 2025 List of Old Residential Area Renovation Projects (Notice No. 1). Available online: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/cxjs/gkml/gwfg/202501/P020250107406057641930.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism. (2025, January 6). The 14th Five-Year Plan for Cultural and Tourism Development of Qingdao (2021–2025). Available online: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/whly/gkml/ghjh/202501/t20250106_8786501.shtml (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Kelly, C.M.; Wilson, J.S.; Baker, E.A.; Miller, D.K.; Schootman, M. Using Google Street View to audit the built environment: Inter-rater reliability results. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45 (Suppl. S1), 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.S.; Kelly, C.M.; Schootman, M.; Baker, E.A.; Banerjee, A.; Clennin, M.; Miller, D.K. Assessing the built environment using omnidirectional imagery. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, P.; Dong, J.; Wang, T. Decoding urban green spaces: Deep learning and Google Street View measure greening structures. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 87, 128028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, L.; Seo, S.H.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring perceived psychological stress in urban built environments using Google Street View and deep learning. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 891736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yabuki, N.; Fukuda, T. Measuring visual walkability perception using panoramic street view images, virtual reality, and deep learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Biljecki, F.; Ito, K. Street view imagery in urban analytics and GIS: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A.S.; Ekroos, J.; Olsson, P.; Smith, H.G. Wild bees and hoverflies respond differently to urbanisation, human population density and urban form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Gao, S.; Lin, H.; Liu, Y. A review of urban physical environment sensing using street view imagery in public health studies. Ann. GIS 2020, 26, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, K. Rethinking Dubai’s urbanism: Generating sustainable form-based codes. Cities 2017, 60, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zhou, Y. Image Urbanism: A New Approach to Human-Scale Urban Morphology Research. Plan. Stud. 2017, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Che, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, S.; Li, H. Extracting Green View Index from Street View Images Using DeepLabv3+: A Case Study within Beijing’s Third Ring Road. Bull. Surv. Map. 2024, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S. Spatial Effects of Street Age-Friendliness Using Street View Images and Machine Learning. J. Geo.-Inf. Sci. 2024, 26, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Lu, H. Associations Between Recreational Patterns and Spatial Characteristics of Community Parks: A Case Study of Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Streetscape Reconstruction: Creating Vibrant Public Spaces. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, S. Current Research on Urban Green Spaces from a Public Health Perspective. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 34, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C. Everyday Public Life in Urban Public Spaces: Case Studies of Yangpu Creative Market, Xuhui Riverside, and Hongkou Civic Station. City Plan. Rev. 2021, 45, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.; Zhang, B.; Li, J. Property Rights, Public Spaces, and Urban Design. Urban Plan. Int. 2008, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, C. Community Social Organizations and the Production of Community Public Spaces. Urban Probl. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. Evaluating Community Planning Implementation from a Public Space Perspective: An Empirical Study of Caoyang New Village. Urban Plan. Forum 2013, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Inclusive Design: Public Space Renewal Strategies for All-Age Communities. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Introduction to Environmental Behavior Theory; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fu, C. Creating Vibrant Public Spaces Guided by Environmental Behavior Theory. Huazhong Archit. 2010, 28, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W.H. City: Rediscovering the Center; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.H. Behavior and the psychophysical methods: An analysis of some recent experiments. Psychol. Rev. 1952, 59, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Wei, W.; Hong, M. The Impact of Spatial Visual Elements on Community Public Space Satisfaction: A Case Study of Wuhan. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Wuhan, China, 23–27 June 2022; Wuhan University: Wuhan, China, 2023; pp. 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W. Landscape Perception and Design of Outdoor Activity Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Ye, D.; Ye, Y. Large-Scale Measurement of Street Interface Permeability Using Street View Data and Deep Learning: A Case Study of Shanghai. Urban Plan. Int. 2023, 38, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, P.; Bie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Guan, Q. A human-machine adversarial scoring framework for urban perception assessment using street-view images. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 2363–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T. Restorative qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yung, E.H.K.; Qian, Q.K.; Lam, P.T.I. A Policy Framework for Producing Age-Friendly Communities from the Perspective of Production of Space. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathy, B.; Patricia, O. Assessing Age-Friendly Community Progress: What Have We Learned? Gerontol. 2021, 62, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Warner, M.E. Cross-Agency Collaboration to Address Rural Aging: The Role of County Government. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2024, 36, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rémillard-Boilard, S.; Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Developing Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Eleven Case Studies from around the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arentshorst, M.E.; Peine, A. From niche level innovations to age-friendly homes and neighbourhoods: A multi-level analysis of challenges, barriers and solutions. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 30, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.R.; Lane, A.P.; Moogoor, A.; Močnik, Š.; Yuen, B. Meaning of age-friendly neighbourhood: An exploratory study with older adults and key informants in Singapore. Cities 2020, 107, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoof, J.V.; Marston, H.R.; Kazak, J.K.; Buffel, T. Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 199, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, E.; Sourbati, M.; Behrendt, F. The Role of Mobility Digital Ecosystems for Age-Friendly Urban Public Transport: A Narrative Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Zhang, L.; Chang, Q. Nature-based solutions for urban heat mitigation in historical and cultural block: The case of Beijing Old City. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Vertical greening for public buildings retrofitting and urban carbon neutrality: A nature-based solution and design practice in China. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 216, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Liu, M.; Yu, Z. Quantifying Ecological Landscape Quality of Urban Street by Open Street View Images: A Case Study of Xiamen Island, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duivenvoorden, E.; Hartmann, T.; Brinkhuijsen, M.; Hesselmans, T. Managing public space—A blind spot of urban planning and design. Cities 2021, 109, 103032.1–103032.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y. Urban spatial growth and driving mechanisms under different urban morphologies: An empirical analysis of 287 Chinese cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 248, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rob, K. The ethics of smart cities and urban science. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20160115. [Google Scholar]

- So, W. Reparative Urban Science: Challenging the Myth of Neutrality and Crafting Data-Driven Narratives. Plan. Theory Pract. 2024, 25, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Caro, P.; Ferrara, P.L. Introduction to Urban Science: Evidence and Theory of Cities as Complex Systems. J. Reg. Sci. 2022, 63, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Acquisition Device | Technical Specifications | Post-Processing Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial panoramic imagery | Insta360 0NE RS panoramic camera | Resolution: 8192 × 4096 px, F0V: 360° × 180°, HDR mode enabled | Auto-stitching via PTGui Pro 12 Chromatic aberration compensation coefficient: 0.73 |

| Principal Component Number | Eigenvalue | Percentage of Variance (%) | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.4547 | 27.2745 | 27.2745 |

| 2 | 1.33825 | 14.86945 | 42.14394 |

| 3 | 1.14575 | 12.73058 | 54.87452 |

| Morphological Classification | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enclosed Space | 16 | 2 | 0 | 18 |

| Transitional Space | 0 | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Open Space | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 16 | 15 | 15 | 46 |

| Morphological Classification | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enclosed Space | 88.89% | 11.11% | 0.00% |

| Transitional Space | 0.00% | 72.22% | 27.78% |

| Open Space | 0.00% | 0.00% | 100.00% |

| summation | 34.78% | 32.61% | 32.61% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y. Data-Driven Assessment and Renewal Strategies for Public Space Vitality in Aged Residential Areas. Buildings 2025, 15, 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234299

Sheng Y, Zhou T, Wang J, Zhao Y. Data-Driven Assessment and Renewal Strategies for Public Space Vitality in Aged Residential Areas. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234299

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheng, Yi, Tong Zhou, Jiabin Wang, and Yaning Zhao. 2025. "Data-Driven Assessment and Renewal Strategies for Public Space Vitality in Aged Residential Areas" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234299

APA StyleSheng, Y., Zhou, T., Wang, J., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Data-Driven Assessment and Renewal Strategies for Public Space Vitality in Aged Residential Areas. Buildings, 15(23), 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234299