Abstract

To clarify the load transfer mechanism of the asphalt mixture skeleton, the discrete element method simulation analysis was conducted to investigate the evolution of the morphological characteristics of the main force chain (MFC) and the mechanical composition of the skeleton. Results indicate that AC-type asphalt mixtures form a greater number of force chains compared with SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures. Although AC-type asphalt mixtures exhibit more MFC, both SMA and OGFC have a higher proportion of MFC (PMFC) throughout the loading process, which is beneficial to transfer external loading effectively. In AC-type asphalt mixtures, the skeleton undergoes reorganization during the initial loading stage, especially in the case of small NMAS. This makes it easy to form MFC with a longer length, some of which exhibit a relatively low alignment coefficient. Consequently, the MFC network of AC is more complex and less efficient for transferring external loading compared with SMA and OGFC. For all asphalt mixtures, the MFC structure evolves in a manner that facilitates load transfer. For skeleton mechanical composition, aggregate within 1.18~2.36 mm is mainly used to fill the void space of the skeleton and has a small amount of participation in the formation of the skeleton. Aggregates within 2.36~9.5 mm mainly participate in the skeleton composition and make a small contribution to filling the void of the skeleton. Aggregates larger than 9.5 mm are fully incorporated into the skeleton composition.

1. Introduction

Asphalt mixture consists of the skeleton structure, asphalt mortar, and air voids. The aggregate skeleton serves two primary functions: firstly, to resist external loading, and secondly, to transfer external loading to other pavement structure layers [1]. With the continuous growth in traffic volume, the load borne by the asphalt mixture has become increasingly heavy. Hence, more and more researchers are paying attention to the composition mechanism of the skeleton and attempting to propose various methods to design a more stable skeleton structure. To evaluate the mechanical properties of the aggregate skeleton, researchers have employed a variety of experimental and numerical simulation methods. Wang et al. [2] used the penetration test to analyze the skeleton strength of porous asphalt concrete (PAC), and proposed the lower and upper limits of percent passing of 9.5 mm to optimize the aggregate gradation. Sun et al. [3] investigated the slip behavior between aggregates using an interface contact-slip tester, finding that the maximum slip shear stress correlates strongly with skeleton stability. In another study, Sun et al. [4] investigated skeleton failure via a custom slip shear device, concluding that aggregate migration is a primary cause of instability for the skeleton. Shi et al. [5] developed a novel test approach to evaluate the shear properties of the asphalt mixture skeleton under varying compaction conditions, demonstrating that shear failure strength effectively reflects the instability of the skeleton under traffic loading. Ding et al. [6] proposed a new method to reconstruct the aggregate skeleton DEM model, and studied the distribution of contact forces within the skeleton. Through DEM simulations, Liu et al. [7] revealed how coarse aggregate morphology affects the mechanical characteristics of PAC, highlighting the significant influence of the 4.75–13.2 mm size range on the strength of PAC-13. Li et al. [8] optimized the aggregate gradation of large stone porous asphalt mixtures to enhance skeleton stability, identifying the 26.5 mm sieve as critical for improving load transfer capacity. Niu et al. [9] studied the role of aggregate contact characteristics in load transfer efficiency and recommended an optimal aggregate content range. A common objective across these studies is to establish the relationship between mineral aggregate gradation and skeleton stability through the statistical analysis of contact force, ultimately guiding gradation design [10,11].

In addition to the statistical analysis of the contact forces, some researchers have begun to apply force chain theory to study the load transfer behavior of aggregate skeletons. Wang et al. [12] conducted photoelastic experiments to analyze load transfer within mixtures by adopting the polycarbonate disks to simulate mineral aggregates. The results confirmed that contact forces inside the skeleton are distributed in the form of chains. In a further study, Wang et al. [13] proposed the concept of an “aggregate contact chain” to evaluate the meso-structural skeleton contacts in asphalt mixtures, discovering that load transfer pathways exhibit a tree-like distribution. Chang et al. [14] investigated force chains in asphalt mixtures with different skeleton structures using the DEM, providing additional validation that the force chain theory applies to the study of asphalt mixture skeletons. Liu et al. [15] reviewed existing force chain identification criteria in granular materials and recommended that such criteria should incorporate three aspects: (1) a normal contact force threshold, (2) a contact angle threshold, and (3) a minimum number of particles in a force chain. Both Liu et al. [16] and Yu et al. [17] analyzed force chain characteristics in various asphalt mixtures using DEM, and consistently observed that mixtures with more stable skeleton structures exhibit longer force chains to transfer load. Jin et al. [18,19] developed an adaptive approach to construct 3D virtual asphalt mixture samples for analyzing the extent and depth of force chains, finding that samples compacted with a Superpave gyratory compactor (SGC) generate more force chains than those prepared by the Marshall method. Furthermore, Liu et al. [20] classified force chains into four types and defined the concept of main force chains (MFCs) in asphalt mixtures.

The above discussion demonstrates that the force chain theory offers a promising approach for revealing the load transfer mechanism within the skeleton of the asphalt mixture. However, existing research has primarily focused on force chain formation criteria, quantitative characterization, and experimental validation. In contrast, few studies have addressed the evolution of force chain characteristics, which is crucial for understanding the load transfer behavior of the skeleton. Therefore, this study attempts to investigate the evolution behavior of MFCs in asphalt mixtures and to further analyze the mechanical composition of the skeleton.

2. Numerical Modeling of Asphalt Mixture Using the Discrete Element Model

2.1. Aggregate Gradation and Micromechanical Parameters

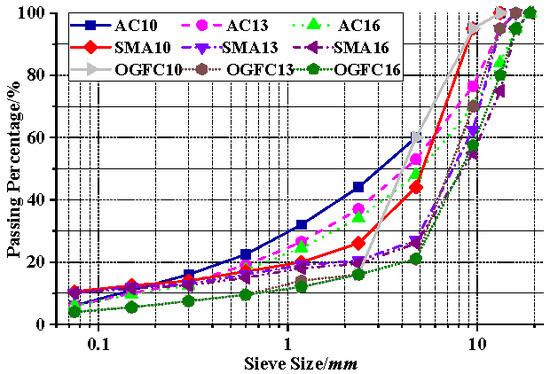

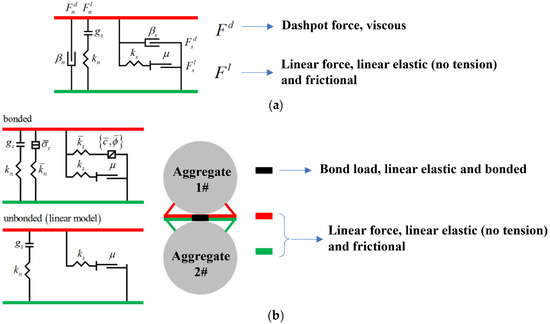

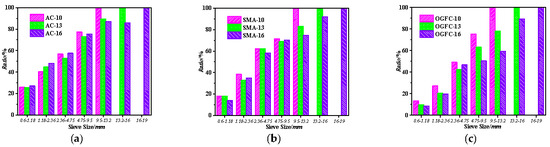

To comprehensively investigate the evolution of the MFC characteristics in different types of asphalt mixtures under external load, DEM models were developed for three typical mixtures: asphalt concrete (AC), stone mastic asphalt (SMA), and open-graded asphalt friction course (OGFC). The aggregate gradations for all mixtures are presented in Figure 1. In the DEM models, aggregates were idealized as round particles. To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, only aggregates larger than 0.6 mm were explicitly modeled. Finer particles (smaller than 0.6 mm) combined with asphalt binder were treated as asphalt mortar, which acts as a bonding agent between coarse aggregates and is represented through micromechanical parameters [21,22,23]. According to the literature research, the linear parallel bond model is appropriate for the analysis of asphalt mixture micromechanical behavior [24,25,26]. Hence, the linear model and linear parallel bond model were adopted in the DEM models of this study, as shown in Figure 2. As illustrated in Figure 2, the linear parallel bond model consists of a linear component and a parallel bond component. The linear component captures the elastic behavior of mineral aggregates, while the parallel bond component represents the cohesive behavior of the asphalt mortar. When the parallel bond fails, the model reverts to a linear contact model. In this study, contacts between aggregates and all walls were modeled using the linear model.

Figure 1.

Different aggregate gradations of asphalt mixtures.

Figure 2.

Linear and linear parallel bond models. (a) Linear model. (b) Linear parallel bond model.

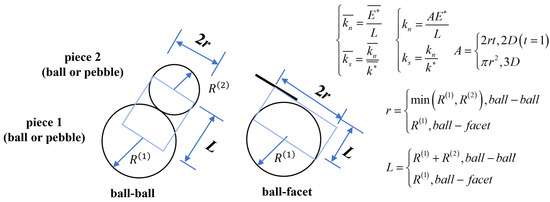

In DEM simulations, the micromechanical parameters of asphalt mixtures are typically calibrated based on macroscopic mechanical tests. A relationship between micromechanical parameters and macroscopic mechanical parameters, such as elastic moduli and so on, can be established by deformation and strength, as illustrated in Figure 3. In this study, macroscopic mechanical data were obtained from references [27,28,29,30]. The micromechanical parameters used to represent the behavior of the asphalt mixture were determined through iterative calibration against experimental results. To ensure the virtual loading plate could successfully compress the asphalt mixture DEM model, the normal and shear stiffness between aggregates and the wall were increased by a factor of 1000 compared to those between aggregates, as provided in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Relationship between micromechanical parameters and macroscopic properties.

Table 1.

Micromechanical parameters for asphalt mixture DEM models.

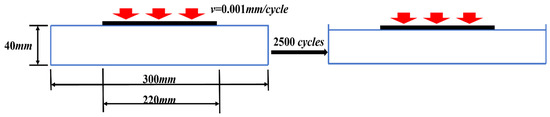

2.2. Virtual Bearing Plate Tests

The virtual bearing plate (VBP) test was designed to investigate the evolution behavior of MFC characteristics in asphalt mixtures under external loading. The test was simulated using PFC2D 5.0. According to the Chinese specifications for the design of highway asphalt pavement [31], the standard axle load consists of a single axle with dual wheels. The loading imprint of each wheel can be represented using either a single-circle or double-circle model, with diameters of 302 mm and 213 mm, respectively. Accordingly, the length of all asphalt mixture DEM models was set to 300 mm, and the bearing plate length was set to 220 mm. Given that the typical thickness of an asphalt surface layer in China is 40 mm, the model height was also set to 40 mm. The VBP test is referred to from the California bearing ratio (CBR) test of soils [32], where the standard penetration depth is 2.5 mm; thus, the same penetration depth was adopted in this simulation. To prevent aggregate particles from escaping the model due to excessive loading speed, the penetration rate of the bearing plate was set to 0.001 mm/cycle. Data on aggregate particles and contact information were recorded every 250 cycles. A schematic diagram of the VBP test is presented in Figure 4. Using AC10 as an example, the state of aggregate particles and force chains at different loading stages is shown in Figure 5. The corresponding results for SMA10 and OGFC10 mixtures are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of VBP test.

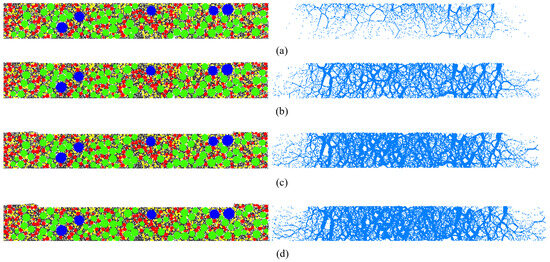

Figure 5.

Force chain evolution behavior of AC10. (a) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-250cycle; (b) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1000cycle; (c) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1750cycle; (d) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-2500cycle.

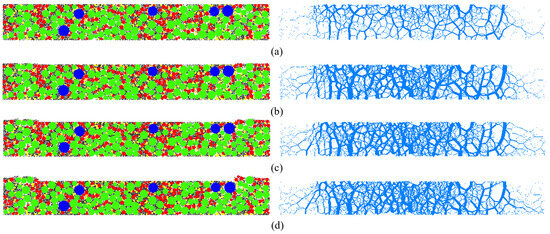

Figure 6.

Force chain evolution behavior of SMA10. (a) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-250cycle; (b) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1000cycle; (c) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1750cycle; (d) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-2500cycle.

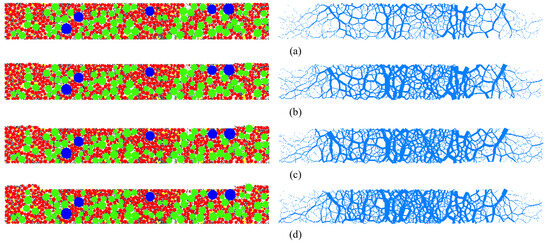

Figure 7.

Force chain evolution behavior of OGFC10. (a) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-250cycle; (b) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1000cycle; (c) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-1750cycle; (d) Aggregate Particle and Force Chain-2500cycle.

3. Force Chain Formation Rules and Evaluation Indices

3.1. Force Chain Formation Rules and Identification Algorithm

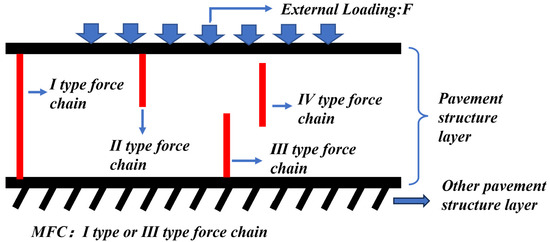

Under external loading, asphalt mixtures develop complex force chains to transfer the applied loads. These force chains vary significantly in their load-bearing roles and transmission paths depending on their type and location. Based on our previous studies [20,33], the force chains within asphalt mixtures can be broadly categorized into four types, as illustrated by Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Different types of force chains for asphalt mixture.

- Type I:

- The load is directly applied from the upper pavement layer, and this type of force chain transfers external loading to other structural layers.

- Type II:

- Although the load also comes directly from the upper pavement layer, this type of force chain only transfers loads within the same layer and does not transfer them to other layers.

- Type III:

- The load originates from within the same pavement layer, and this type can transfer external loading to the lower pavement structure.

- Type IV:

- The load is also derived from within the same layer, but this type only transmits loads internally, with no transfer to other pavement layers.

Among these, Type I and Type III force chains are defined as the main force chains (MFCs), as they effectively transfer external loads to lower pavement layers.

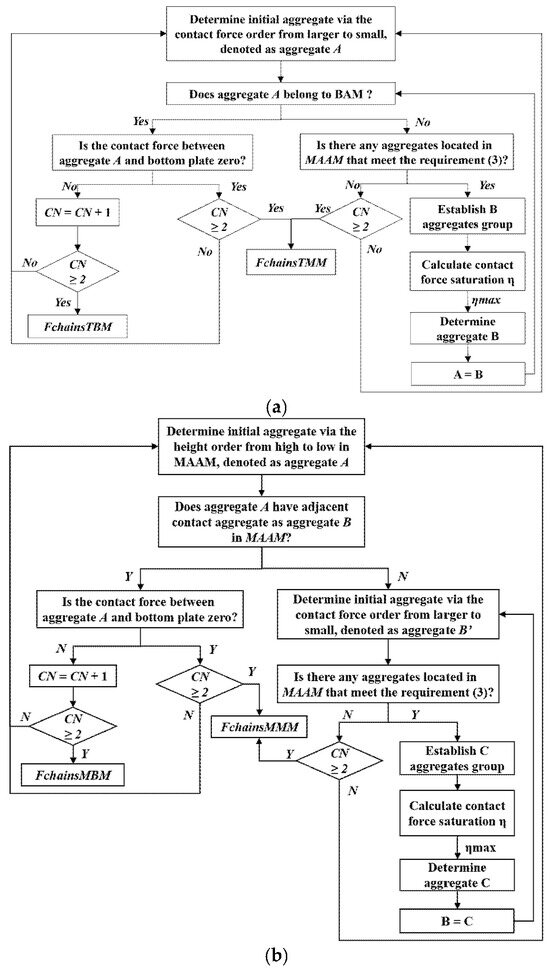

Currently, there is no universally accepted standard for defining force chain formation in asphalt mixtures. Liu et al. [15] proposed that a force chain is formed when inter-aggregate contacts satisfy three conditions: a normal contact force threshold, a contact angle threshold, and a minimum number of particles. However, these criteria often lead to the repeated identification of the same force chains. Moreover, the use of a contact angle threshold to determine force chain extension remains contentious. To address these limitations, Liu et al. [20] proposed normal contact force saturation η and real-time updating of normal contact force. Based on these studies, the present study adopts a set of five criteria to identify the four types of force chains described earlier: ① Normal contact force threshold , ② Normal contact force saturation η, ③ Aggregate location requirement, ④ Number of contacts, and ⑤ Real-time updating of normal contact force. Detailed explanations of these criteria can be found in our previous research study [33], and are not explained in detail here. Based on these formation rules, a recognition algorithm was developed, as outlined in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Flow diagram of single force chain identification. (a) I and II types of force chains (FchainsTBM and FchainsTBM represent I and II type force chains, respectively). (b) III and IV types of force chains (FchainsMMM and FchainsMBM represent III and IV type force chains, respectively).

3.2. Evaluation Indices for MFC

The force chain total number, the total number of MFCs, and the proportion of MFCs can be calculated by Equations (1)–(3), respectively. Under the same external loading, a higher total number of force chains indicates that more load transfer paths are formed within the asphalt mixture. A greater number of MFCs reflects an increase in the number of effective load transfer paths. However, this also leads to greater complexity in the load transfer process, which may reduce overall transfer efficiency. The proportion of MFCs represents the percentage of force chains that can effectively transfer loads relative to the total number of force chains. A higher value of this proportion indicates that the MFC structure possesses better load transfer capability.

where represents the force chain total number. expresses the total number of MFCs. denotes the proportion of MFCs in all types of force chains. , , , and represent I type force chain, II type force chain, III type force chain, and IV type force chain number.

The total length of the MFC and the average length of the MFC are calculated via Equations (4) and (5), respectively. A larger total length of the MFC suggests a more complex network structure, which is associated with reduced efficiency in effective load transfer. Conversely, a greater average length of the MFC indicates an increasing proportion of type I force chains within the MFC network, which corresponds to improved efficiency in load transfer.

where LMFC expresses the total length of the MFC. li denotes the length of the ith MFC. ALMFC represents the average length of the MFC. The meaning of other parameters can be found in the above.

The stability of the asphalt mixture skeleton is determined by the state of the main force chains (MFCs), which can be characterized by their tortuosity. In this study, the tortuosity of the MFC is quantified using an alignment coefficient, and the average alignment coefficient of the main force chain (MFCAC) can be calculated via Equation (6). The direction angle of the main force chain (MFCDA) is defined as the vector direction of the MFC, and the detailed explanation of the MFCDA can be found in references [33,34]. The deviation degree of all main force chains (MFCDADD), calculated via Equation (7), is associated with the efficiency of load transfer.

where represents the average MFCAC. α denotes the average deviation degree of MFC, average MFCDADD. and express the alignment coefficient of the ith MFC and direction angle of the ith MFC, respectively. The detailed definitions and expressions of and can be found in references [33,34], and are not explained in detail here.

4. Evolution Behavior of MFCs

Under external loads, the evolution behavior of the MFC in asphalt mixtures varies significantly with different aggregate gradations. As a result, aggregate particles produce different migration patterns. Investigating how the MFC evolves under different conditions sheds light on the fundamental mechanisms governing load transfer and skeletal composition from a mechanical perspective. These are conducive to establishing the correlation model between aggregate gradation and MFC characteristics, thereby integrating aggregate gradation design with the mechanical properties of the skeleton. Therefore, this study investigates the evolution laws of MFCs in asphalt mixtures under different gradations. To reveal the evolution laws of asphalt mixture MFCs, force chain total number, MFC number, MFC number proportion, MFC total length, average MFC length, average MFCAC, and average MFCDADD were analyzed as shown in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, respectively.

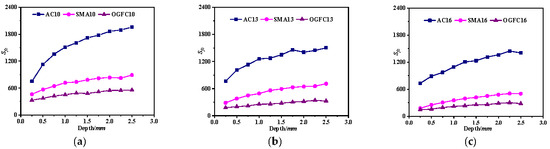

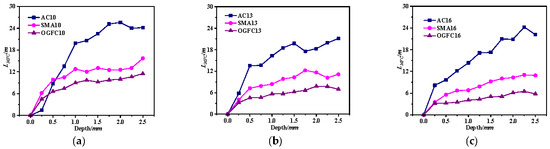

Figure 10.

Asphalt mixture force chain total number. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

Figure 11.

Asphalt mixture MFC total number. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

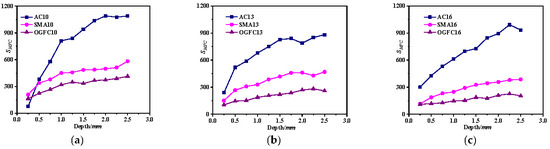

Figure 12.

Asphalt mixture MFC proportion. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

Figure 13.

Asphalt mixture MFC total length. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

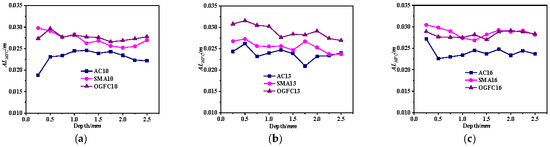

Figure 14.

Asphalt mixture MFC average length. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

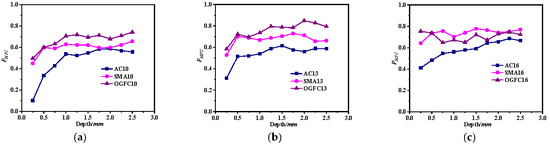

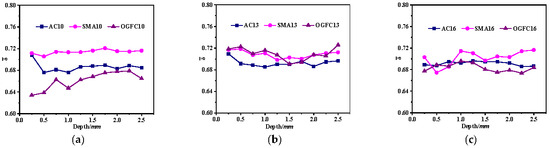

Figure 15.

Asphalt mixture average MFCAC. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

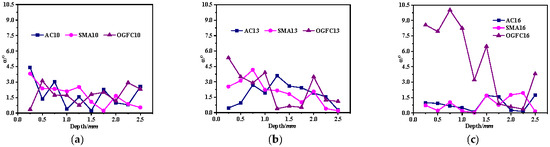

Figure 16.

Asphalt mixture average MFCDADD. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

Figure 10 shows the Sfc of different asphalt mixtures. As force chains serve as the primary pathways for transferring external loads within asphalt mixtures, statistical analysis of Sfc offers insight into the evolution laws of external loading transfer paths in asphalt mixtures during the loading process. From Figure 10a, it can be observed that for AC-type asphalt mixtures, Sfc increases rapidly during the initial loading stage and subsequently rises linearly with greater penetration depth. In contrast, both SMA and OGFC asphalt mixtures exhibit an approximately linear increase in Sfc throughout the loading process. These trends suggest that the asphalt mixture becomes progressively denser as the penetration depth increases. At the same penetration depth, SMA and OGFC require more external load to achieve further deformation, leading to the formation of additional force chains for load transfer. Data in Figure 10 further support that AC mixtures develop more force chains compared to skeleton-type mixtures such as SMA and OGFC under the same NAMS.

MFCs serve as critical pathways for transferring external loads to other pavement structural layers within the asphalt mixture’s force chain network. Analyzing the evolution of SMFC helps elucidate how the MFC network develops under external loading. It can be seen from Figure 11 that SMFC generally increases with an increase in penetration depth. Notably, the SMFC of AC-type asphalt mixtures rises more rapidly with the increase in penetration depth compared with skeleton-type asphalt mixtures such as SMA and OGFC. Under external loading, aggregate particles in AC asphalt mixtures are more prone to migration, leading to more significant reorganization within the MFC network. In contrast, skeleton-type asphalt mixtures have better skeleton stability, and aggregate particles are relatively difficult to migrate under the action of external loading. The reorganization degree of the MFC network structure of skeleton-type asphalt mixtures is lower than that of AC. Therefore, the SMFC of AC-type asphalt mixtures increases faster with an increase in penetration depth compared with SMA- or OGFC-type asphalt mixtures under the same penetration conditions.

Figure 12 shows the MFC number proportion (PMFC) in the asphalt mixture’s force chain network. A larger PMFC indicates a stronger capacity of the skeleton to transfer loads effectively. As shown in Figure 12, for AC-type asphalt mixtures, MFC takes up a small proportion during the initial loading stage, especially under small NMAS, where PMFC is only around 10%. However, PMFC increases significantly with the increase in loading depth and eventually stabilizes at approximately 60%. It can also be observed from Figure 12 that PMFC gradually increases with larger NMAS early in the loading process. Furthermore, although AC-type asphalt mixtures develop a greater number of MFCs, both SMA and OGFC exhibit a higher PMFC during the whole loading process. Consequently, SMA and OGFC show better efficiency in transferring external loading effectively.

As shown in Figure 13, the LMFC in AC-type asphalt mixtures increases rapidly during the initial loading stage as penetration depth increases, with the growth rate slowing in the mid and late stages. SMA and OGFC asphalt mixtures have a similar change trend in LMFC development. However, their growth rates remain lower than those of AC-type asphalt mixtures throughout all stages. The SMFC of AC is substantially higher than that of SMA and OGFC asphalt mixtures, and so the LMFC of skeleton-type asphalt mixtures is significantly shorter than that of suspended-dense asphalt mixtures. During the initial loading stage, the contact between aggregates increases with an increase in penetration depth due to the presence of certain voids inside the asphalt mixture, leading to rapid growth in LMFC. In the middle and late loading stages, the asphalt mixture has become dense, and although external load continues to increase, the LMFC grows slowly. At the same penetration depth, the LMFC of AC-type asphalt mixtures is longer than that of SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures in the middle and late loading stages. These results indicate that the MFC network of AC is more complex than that of SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures under equivalent loading conditions, resulting in lower load transfer efficiency and inferior skeleton performance.

It can be found in Figure 14 that the average length of MFC (ALMFC) is less than the thickness of the corresponding pavement structure for all types of asphalt mixtures. This suggests that most MFCs belong to type III force chains. It can also be identified from Figure 14 that for AC-type asphalt mixtures, ALMFC of some specimens initially increases and then maintains a relatively stable trend with the increase in penetration depth, and that of others decreases first and then remains relatively stable with the increase in penetration depth. These results indicate that the ALMFC does not follow a consistent trend among different AC-type asphalt mixtures during the initial loading stage, instead exhibiting disordered variation. In the initial loading stage, the migration behavior of aggregate particles is different in various AC-type asphalt mixtures. In contrast, during later stages, the behavior becomes more uniform, and the ALMFC stabilizes. Compared with AC-type asphalt mixtures, SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures possess more stable skeleton structures. Consequently, the average length of its MFC remains relatively consistent throughout the loading process. Figure 14 also illustrates that the ALMFC of the skeleton-type asphalt mixtures is generally longer than that of AC-type asphalt mixtures, although the difference among various skeleton-type asphalt mixtures is relatively smaller in the whole loading stage. Hence, skeleton-type asphalt mixtures have better transferring external loading.

The alignment coefficient serves as an indicator of the linearity of MFCs. A higher value indicates that the MFC more closely approximates a straight line. A straight MFC exhibits greater stability when transferring external loads, which is closely associated with the stability of the skeleton structure. Hence, analyzing the evolution of the MFCAC helps evaluate the stability of the skeleton. As shown in Figure 15, the is generally greater than 0.5. From a physical perspective, this suggests that the force chain formation criteria adopted in this study effectively capture the quasi-linear nature of the MFC. This observation is consistent with granular mechanics principles, wherein force chains tend to transmit loads along nearly straight paths.

For AC-type asphalt mixtures, the average MFCAC of AC10 and AC13 initially decreases slightly and then stabilizes with an increase in penetration depth. However, that of AC16 remains relatively stable throughout the entire loading process. These results suggest that the skeleton structure of AC-type asphalt mixtures undergoes reorganization during the initial loading stage, especially in the case of small NMAS. This will make it easy to form MFCs with a longer length, some of which exhibit a relatively small alignment coefficient. With further loading, the skeleton structure is relatively stable after the asphalt mixture is compacted, so the remains relatively stable. For the SMA-type asphalt mixture, the of SMA10 and SMA13 remains relatively stable across all loading stages. However, the fluctuation range of of SMA16 is large at the initial loading stage, followed by a slight increasing trend in the later stage. This indicates that SMA mixtures with larger NMAS may have difficulty effectively contributing to load transfer when the pavement structure is relatively thin. For the OGFC-type asphalt mixture, the of OGFC10 increases slightly during the initial loading stage, and it remains relatively steady at the middle and late loading stages. The of OGFC13 and OGFC16 remains relatively stable during the whole loading process.

Figure 16 shows that for AC-type asphalt mixture, the average MFCDADD shows a fluctuation in the range of 0°~4°. This value gradually decreases with the increase in the loading depth, indicating that the MFC structure evolves in a manner that is conducive to the transfer of external loading. For SMA-type asphalt mixtures, the deviation degree of SMA10 and SMA13 generally decreases with an increase in loading depth, and the average MFCDADD is close to zero in the later loading stage. Throughout the entire loading process, the average MFCDADD of SMA16 fluctuates within a narrow range of 0°~1.5°, and its value is also close to zero in the later loading stage. These results suggest that the MFC evolves in a direction conducive to transfer external loading in the whole loading stage for SMA-type asphalt mixtures. The average MFCDADD of OGFC-type asphalt mixtures exhibits a trend similar to that of SMA. Compared with AC-, SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures show slightly smaller average MFCDADD values, indicating that external loads are transferred more vertically. This is beneficial to transfer external loading, contributing to the superior stability of the skeleton in SMA and OGFC.

5. Mechanical Composition of Asphalt Mixture Skeleton

The skeleton structure is the main body to bear and transfer external loading in the asphalt mixture. Within the force chain network of the mixture, only the MFC can transfer external loading to the underlying structural layers. Consequently, the aggregates located in these MFCs can be regarded as participating in the composition of the skeleton structure. In this study, a parameter termed “Ratio” is proposed to evaluate the contribution of aggregates at each sieve size to the skeleton function, as detailed in the following section.

where Ratio is the functional index for every sieve size aggregate, %. represents the area of the ith sieve size aggregate located in the main force chains in a certain asphalt mixture DEM model, m2. expresses the total area of the ith sieve size aggregate in a certain asphalt mixture DEM model, m2.

- Ratio < 25%: All of the ith sieve size aggregate is to fill the void of the skeleton structure.

- 25% ≤ Ratio < 50%: The ith sieve size aggregate mainly fills voids, with a minor contribution to the skeleton composition.

- 50% ≤ Ratio < 75%: The ith sieve size aggregate predominantly participates in skeleton composition, with a limited void-filling function.

- Ratio ≥ 75%: All of the ith sieve size aggregate fully contributes to the skeleton composition.

Figure 17 shows the proportion of aggregate participating in skeleton composition in different asphalt mixtures. It can be seen from Figure 17a that the Ratio for aggregates in the 0.6–1.18 mm range is about 25%. This means that these aggregates only play a role in filling the void within the skeleton for the AC-type asphalt mixture. For aggregates within 1.18–2.36 mm, the Ratio is close to 45%, suggesting that these aggregates are mainly used for void filling while also contributing slightly to skeleton formation. The Ratio for aggregate within 2.36–4.75 mm and 4.75–9.5 mm is approximately 50% and 80%, respectively. This implies that aggregates within these size ranges play a major role in skeleton composition, with only a minor contribution to filling the void. For aggregates larger than 9.5 mm, the Ratio exceeds 80%, indicating that nearly all such particles participate in skeleton formation. Similar trends are observed in SMA- and OGFC-type asphalt mixtures.

Figure 17.

Skeleton mechanical composition of different asphalt mixtures. (a) NMAS-9.5 mm. (b) NMAS-13.2 mm. (c) NMAS-16 mm.

6. Conclusions

Based on the above results and discussions, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- Compared with SMA and OGFC, AC-type asphalt mixtures have a greater number of force chains under the same NAMS. Although AC-type asphalt mixtures have more MFCs, both SMA and OGFC show a higher PMFC throughout the entire loading process.

- (2)

- In AC-type asphalt mixtures, the skeleton undergoes structural reorganization during the initial loading stage, especially in the case of small NMAS. This makes it easy to form MFCs with a longer length, which in turn leads to a relatively small alignment coefficient in a portion of the MFC.

- (3)

- Compared to SMA and OGFC, the MFC network in AC mixtures exhibits greater complexity and lower efficiency in transferring external loads. For all asphalt mixtures, the MFC structure evolves in a direction that is conducive to the transfer of external loading.

- (4)

- Aggregates within the 1.18–2.36 mm range primarily serve to fill voids in the skeleton, with only minor participation in skeleton formation. Those between 2.36–4.75 mm and 4.75–9.5 mm contribute mainly to skeleton composition, while playing a limited role in void filling. Aggregates larger than 9.5 mm participate almost entirely in skeleton construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; Methodology, G.L.; Software, C.Y.; Writing—original draft, K.L.; Writing—review & editing, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: ① National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 52208448], ② Double Innovation Doctor of Jiangsu [No. JSSCBS20221503] and ③ Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [No. 2022QN1020]. The authors gratefully acknowledge their financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, D.; Xi, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y. 3D Virtual reconstruction of asphalt mixture microstructure based on rigid body dynamic simulation. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2165654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gu, X.; Jiang, J.; Deng, H. Experimental analysis of skeleton strength of porous asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, P.; Akhtar, J.; Su, J.; Dong, C. Analysis of deformation behavior and microscopic characteristics of asphalt mixture based on interface contact-slip test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, P.; Niu, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Structure stability and shear failure behaviors of asphalt mixtures from the perspective of aggregate particle migration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qian, G.; Hu, C.; Yu, H.; Gong, X.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Li, T. Experimental study of aggregate skeleton shear properties for asphalt mixture under different compaction stages. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Ma, T.; Huang, X. Discrete-Element Contour-Filling Modeling Method for Micromechanical and Macromechanical Analysis of Aggregate Skeleton of Asphalt Mixture. J. Transp. Eng. Part B-Pavements 2019, 145, 04018056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, Z.; Zheng, D. Influence of coarse aggregate morphology on the mechanical characteristics of skeleton in porous asphalt concrete. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2252158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, D.; Zhao, Y. Stress analysis and optimization of coarse aggregate of large stone porous asphalt mixture based on discrete element method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Shi, W.; Wang, C.; Xie, X.; Niu, Y. Effect of coordination number of particle contact force on rutting resistance of asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zou, S.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Y.; Shao, L.; Yuan, J.; Gou, X.; Jin, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Clinically applicable histopathological diagnosis system for gastric cancer detection using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Miao, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of grain size composition on mechanical performance requirement for particles in aggregate blend based on photoelastic method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Xu, R.; Wang, D. Meso-structural evaluation of asphalt mixture skeleton contact based on Voronoi diagram. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Pei, J.; Zhang, J.; Xing, X.; Xu, S.; Xiong, R.; Sun, J. Quantitative distribution characteristics of force chains for asphalt mixtures with three skeleton structures using discrete element method. Granul. Matter 2020, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Han, D. Research on Asphalt Mixture Force Chains Identification Criteria Based on Computational Granular Mechanics. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 48, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Han, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of Asphalt Mixture Structure Types on Force Chains Characteristics Based on Computational Granular Mechanics. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 23, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Miao, Y. Characterizing force-chain network in aggregate blend using discrete element method and complex network theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Xing, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Li, S. Adaptive construction approach for virtual samples of hot mix asphalt based on 3-D structural characterization of laboratory compact specimens. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, P.; Yang, X.; Oeser, M. Virtual modeling of asphalt mixture beam using density and distributional controls of aggregate contact. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. 2023, 38, 2242–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Han, D.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, Y. Asphalt mixture skeleton main force chains composition criteria and characteristics evaluation based on discrete element methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.D.; Feng, K.; Xing, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhao, Y.L. Synchronous strain and modulus sensing in asphalt layers via inclusion-matrix deformation mapping. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Ran, J.; Gao, F.C.; Zhang, N.T.; Zhao, Y.L. Study on the formation mechanism of reflective cracks in semi-rigid base asphalt pavement based on energy evolution mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.Y.; Han, D.D.; Ma, Y.C.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y.L. Macroscopic properties and microscopic characterisation of an optimally designed anti-cracking stone base course filled with cement stabilised macadam. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 26, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. Micro-damage characteristics of cold recycled mixture under freeze-thaw cycles based on discrete-element modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Duan, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y. Numerical simulation of effect of reclaimed asphalt pavement on damage evolution behavior of self-compacting concrete under compressive loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 395, 132323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, H.; Qian, G.; Yao, D.; Dai, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhong, H. Evaluation of asphalt mixture micromechanical behavior evolution in the failure process based on Discrete Element Method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, X. Simulation of uniaxial compression test for asphalt mixture with discrete element method. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2009, 37, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Xu, C.; Liang, H. Investigation into meso performance of asphalt mixture skeleton based on discrete element method. J. South China Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2015, 43, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Ma, C.H.; Mok, C.M.B. Experimental characterization and 3D DEM simulation of bond breakages in artificially cemented sands with different bond strengths when subjected to triaxial shearing. Acta Geotech. 2017, 12, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Li, Z.F.; Tai, P.; Zeng, Q.; Bai, Q.S. Numerical Investigation of Triaxial Shear Behaviors of Cemented Sands with Different Sampling Conditions Using Discrete Element Method. Materials 2022, 15, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Specifications for Design of Highway Asphalt Pavement; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Huang, T.; Lyu, L.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C. Effective Load Transfer Capacity Analysis for Asphalt Mixture Skeleton Based on Main Force Chain Characteristics and Discrete Element Method. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, C.; Han, D.; Zhao, Y. Asphalt mixture force chains morphological characteristics and bearing capacities investigation using discrete element method. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2168660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).