A Global Performance-Based Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Hospital Building Equipped with Dissipative Bracing Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Type A: metallic panels designed to dissipate energy through shear yielding, activated by relative interstory displacements induced by seismic loading;

- Type B: passive dissipation devices embedded within infill walls, incorporating shear connections that enable controlled sliding between partitions during earthquakes.

2. Methodology

- Data collection and structural characterization: compilation of original design documentation, in situ inspection data, and material test results, which formed the basis for defining geometry, reinforcement details, and mechanical properties of both existing and retrofitted structural components.

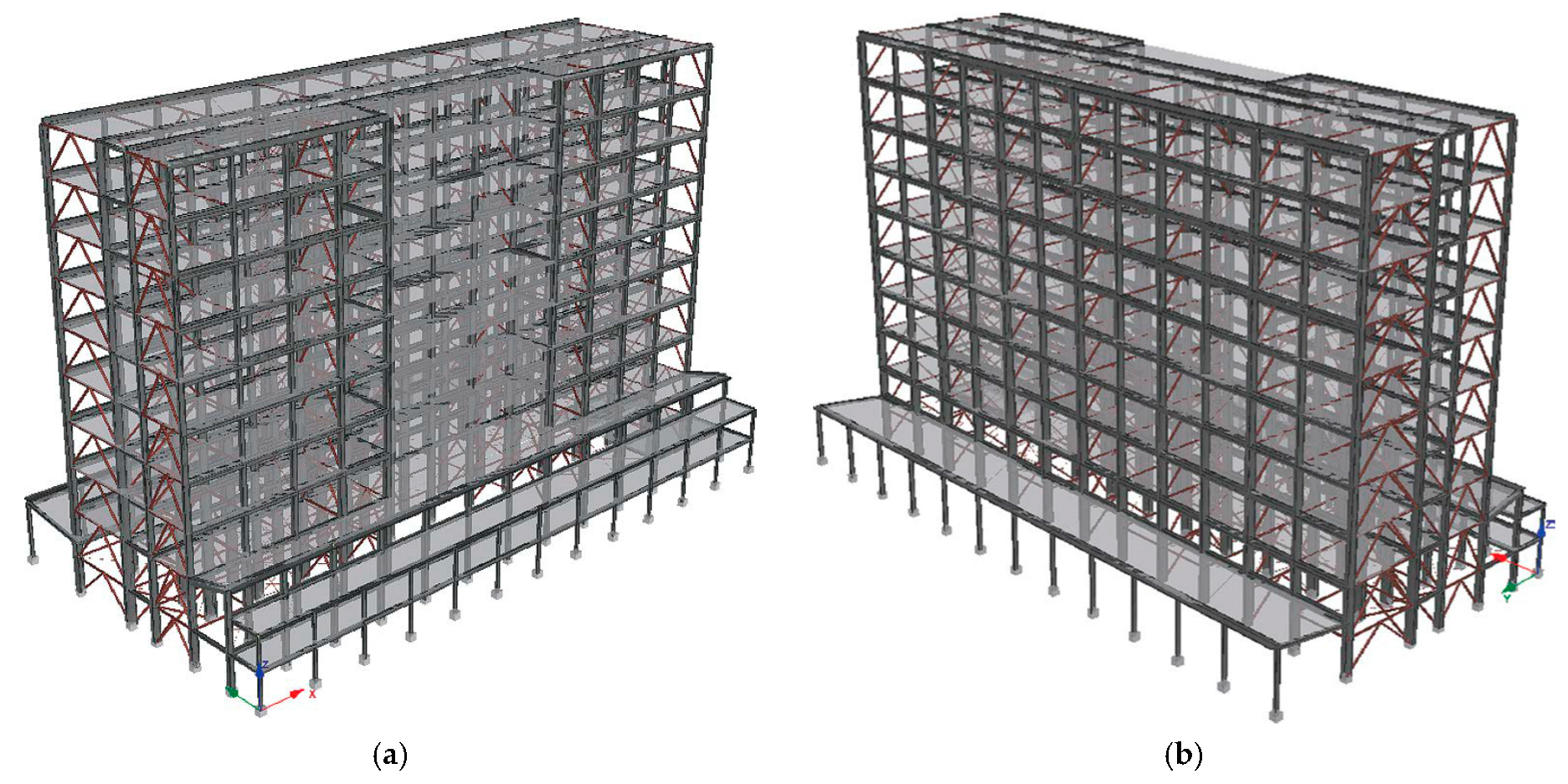

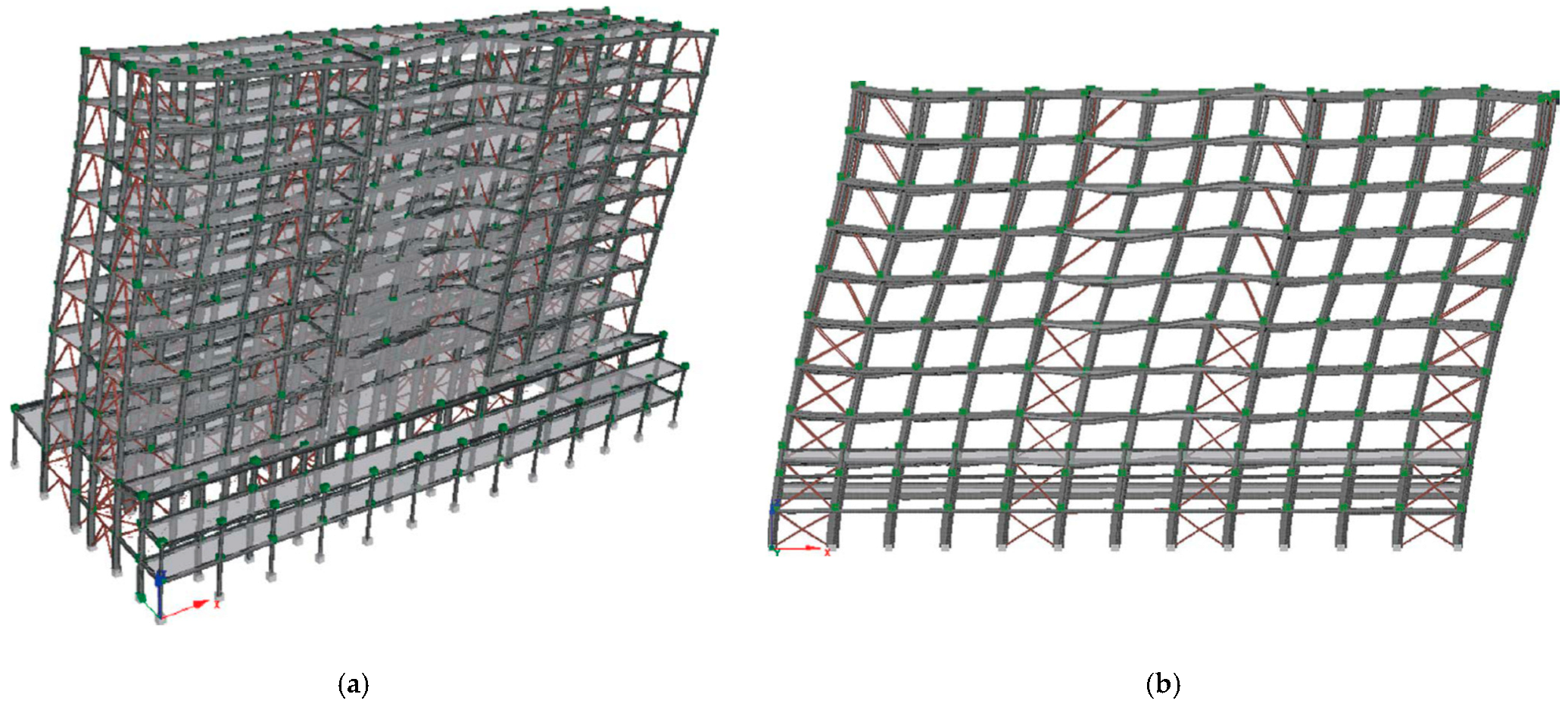

- Development of the numerical model: creation of three-dimensional finite element models of Blocks H and C using SeismoStruct, accounting for geometric and material nonlinearities, as well as previously implemented strengthening interventions (steel bracing and jacketing).

- Definition of seismic input: determination of design spectra for the Life Safety and Near Collapse limit states according to the Italian Building Code (NTC 2018), considering local site effects, soil category, and topographic amplification.

- Nonlinear static (pushover) analyses: performance evaluation of the retrofitted structures under monotonic lateral load distributions in both principal directions, following the displacement-based procedure outlined in NTC 2018 §C8.7.1.2.

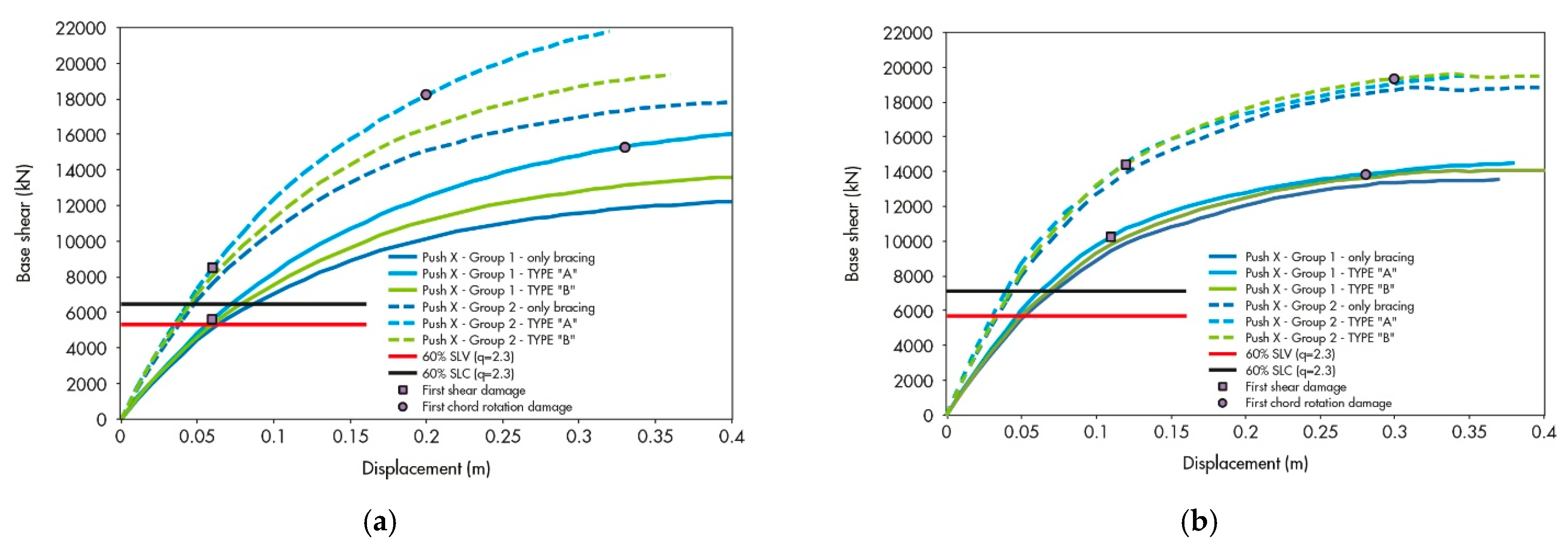

- Comparative assessment of retrofitting solutions: evaluation of three dissipative systems (Types A, B, and C), with emphasis on base shear capacity, equivalent damping, and global displacement demand, to verify compliance with the target seismic safety level of 60% required for existing hospital buildings.

- Interpretation and validation of results: critical analysis of the obtained capacity curves, equivalent viscous damping ratios, and performance indices, followed by discussion of the implications for practical design and future research.

3. Structural Description

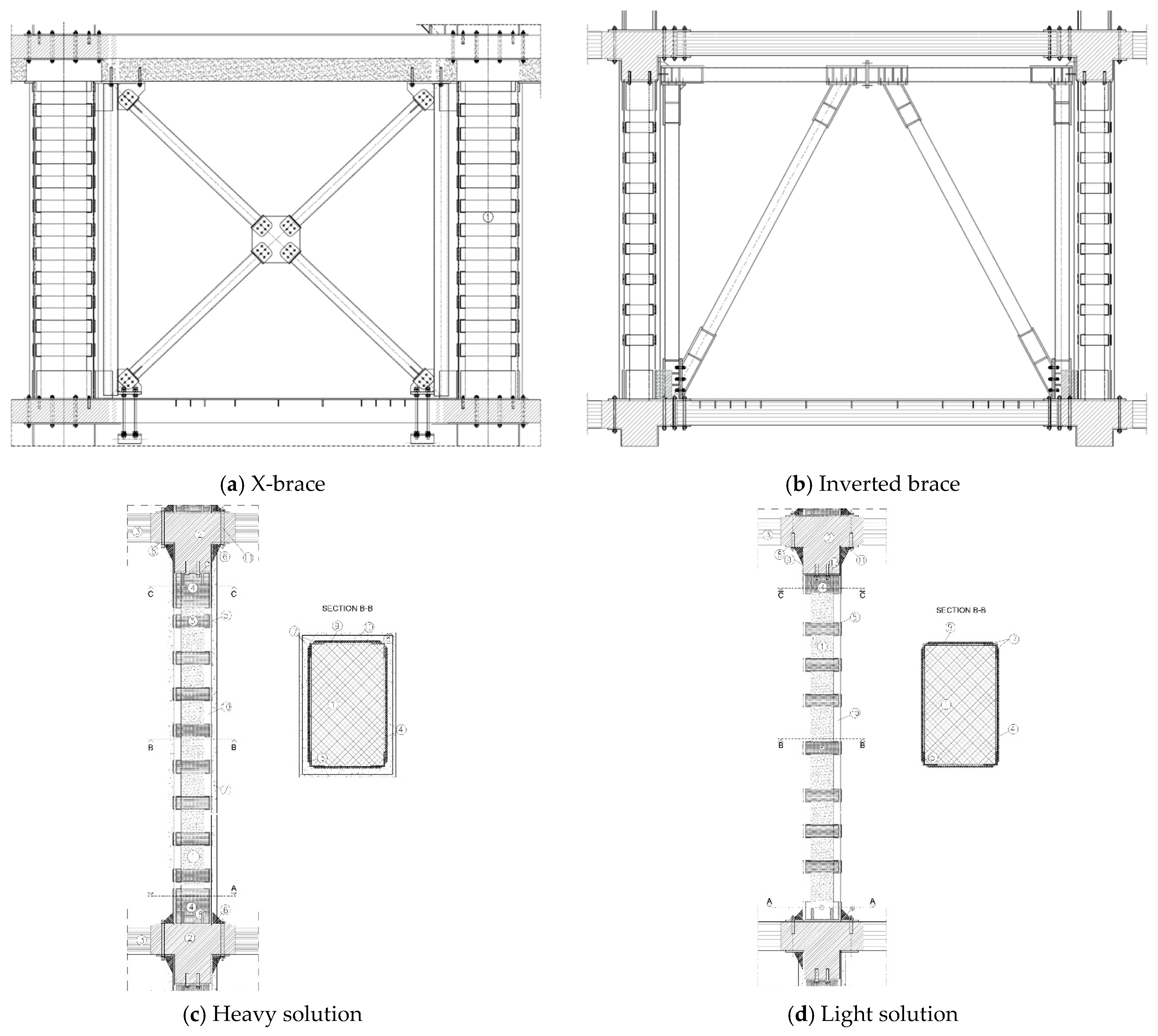

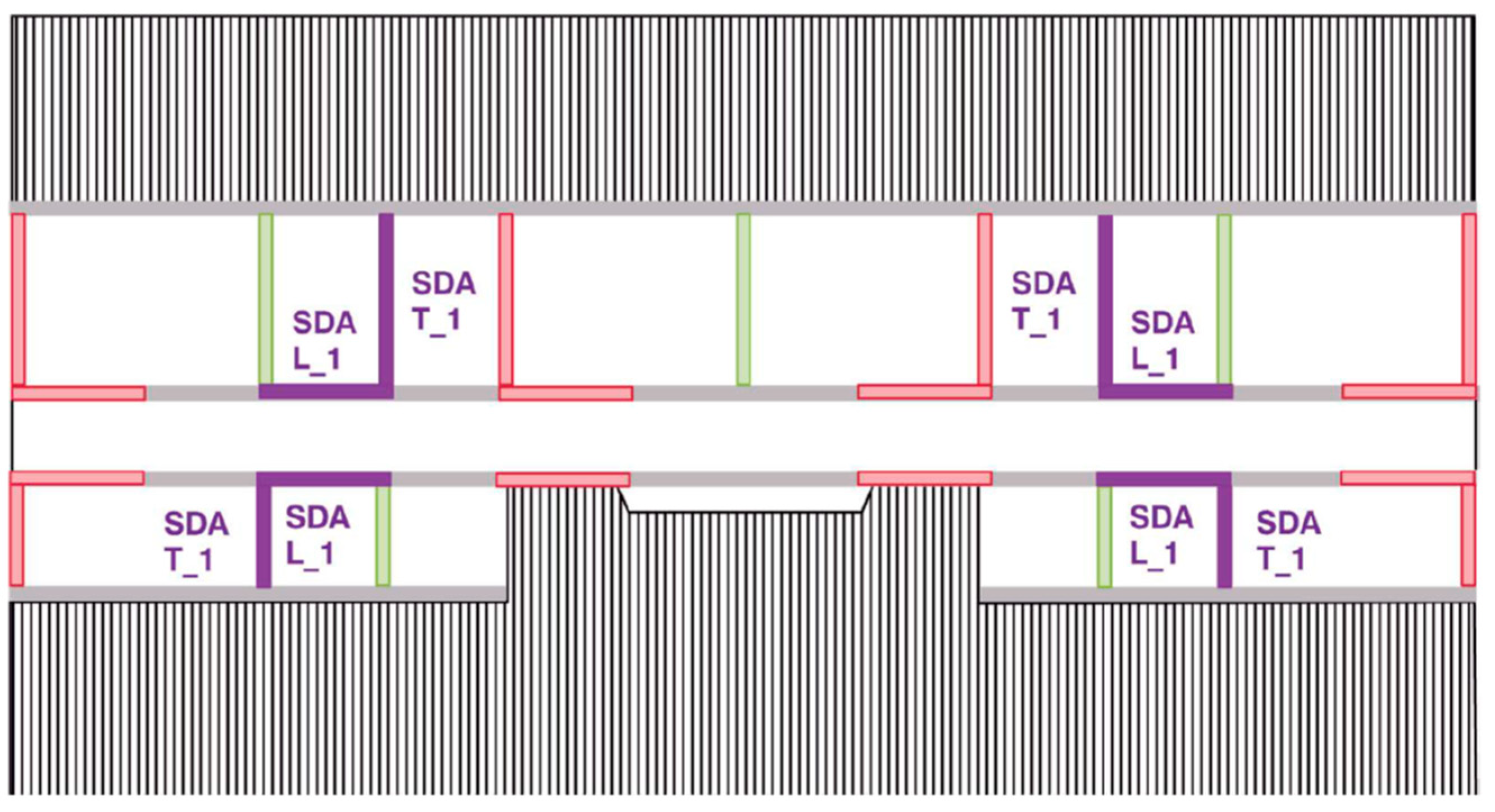

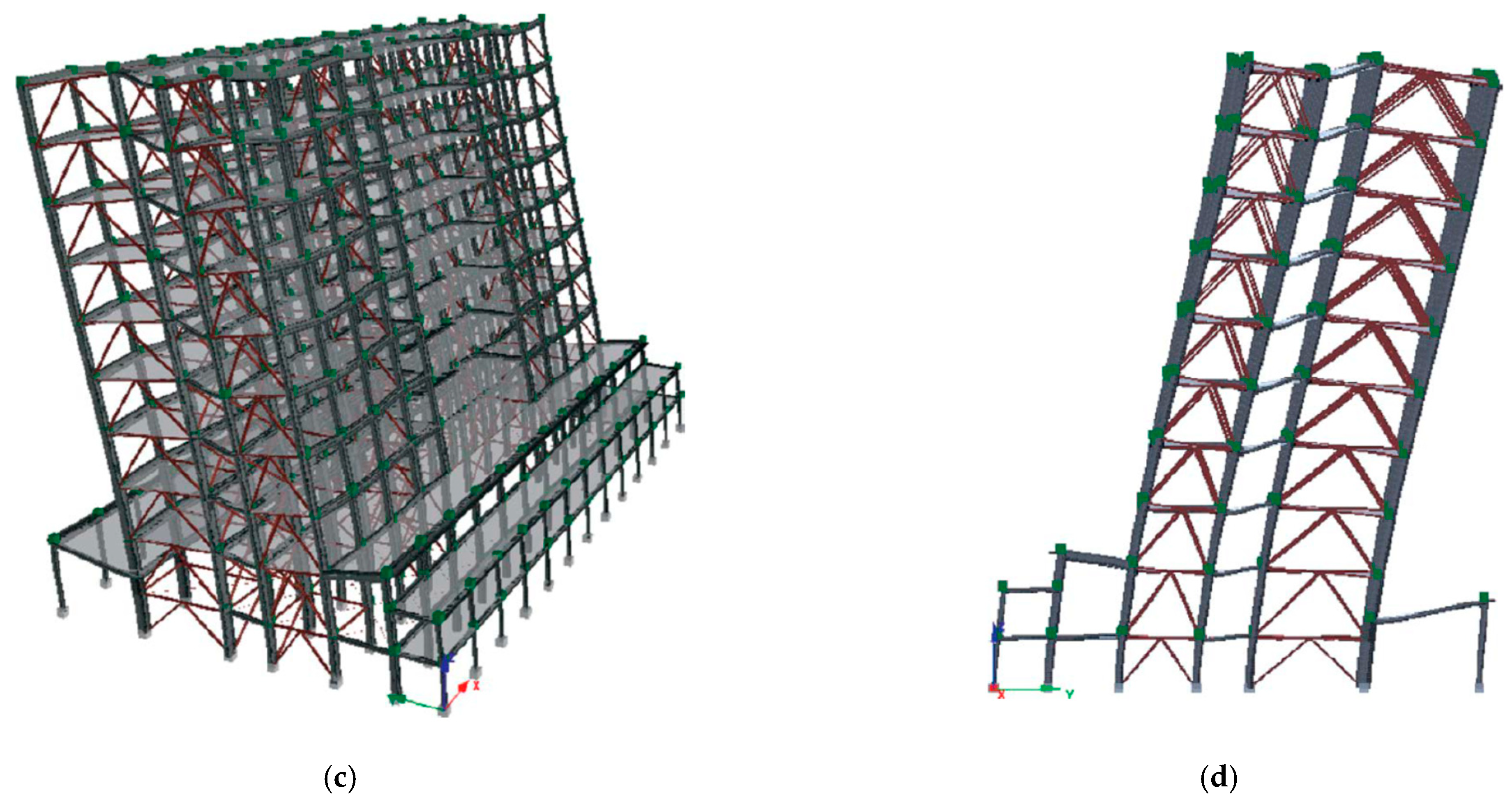

- Integration of Bracing Systems: steel bracing systems were incorporated within the existing frame bays to enhance lateral resistance in both (Figure 2a) and (Figure 2b) orthogonal directions. Concentric braces were installed along the direction and inverted V-bracing was employed along the direction. In both cases, the bracing elements were connected to steel columns and beams, which were firmly anchored to the existing RC frame using specialized connectors to ensure proper load transfer.

- Column Jacketing for Enhanced Load Capacity: to strengthen the reinforced concrete columns, two types of steel jacketing methods were adopted: “Light reinforcement” steel jackets (Figure 2d), designed to provide moderate confinement and stiffness; “Heavy reinforcement” (Figure 2c) steel jackets, further enhanced with fiber-reinforced concrete layers to significantly increase structural ductility and strength.

- Insertion of Horizontal Bracing Systems: to improve the global stability of the structure, horizontal bracing systems were integrated into the double-height floors through the use of steel tie rods, ensuring effective load distribution under seismic excitation.

4. Selected Seismic Action

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Phase 1: Application of Two Dissipative Systems (Type A and Type B)

5.1.1. Overview of the Added Energy Dissipation Devices

5.1.2. Structural Modeling and Analysis

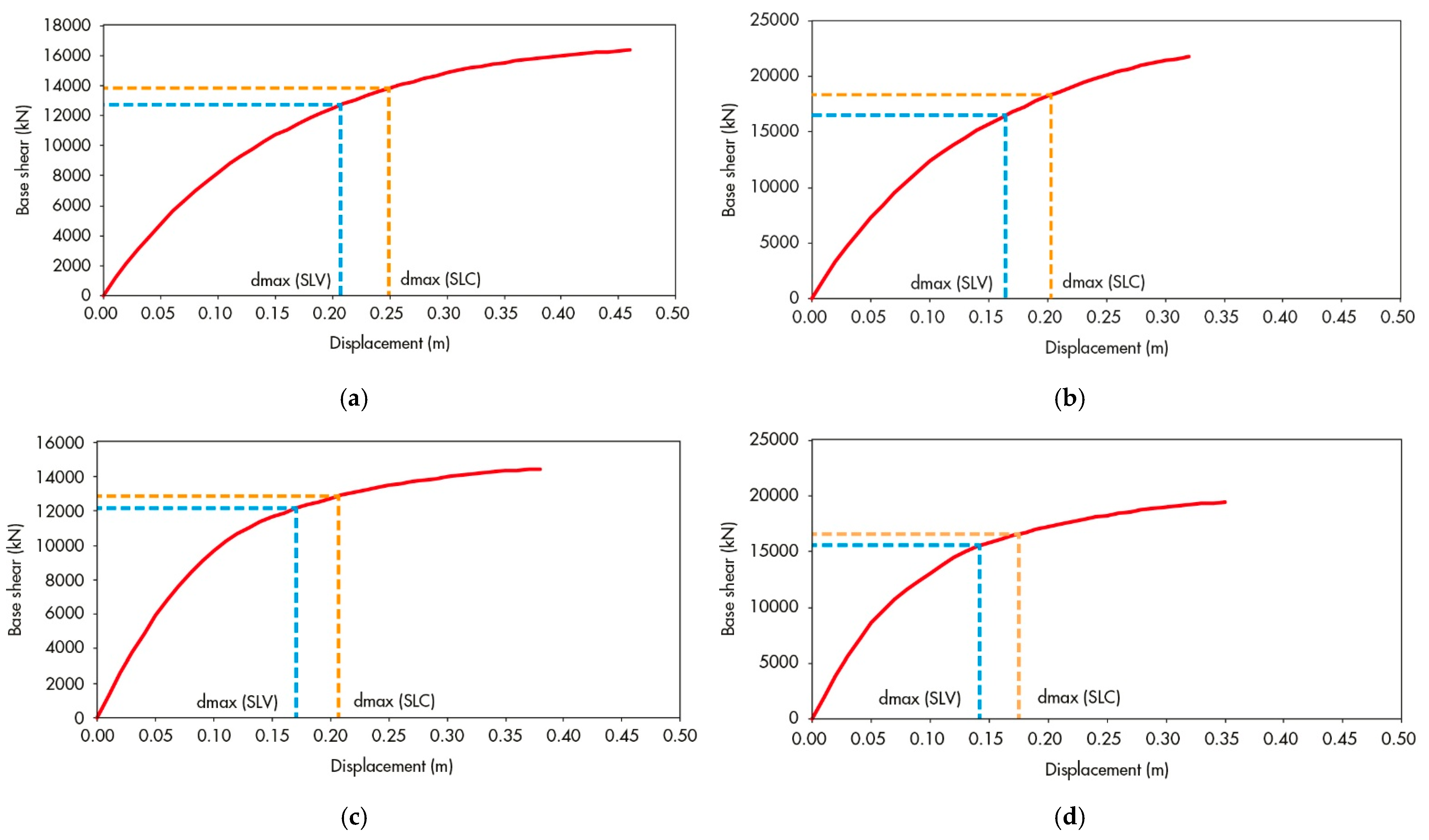

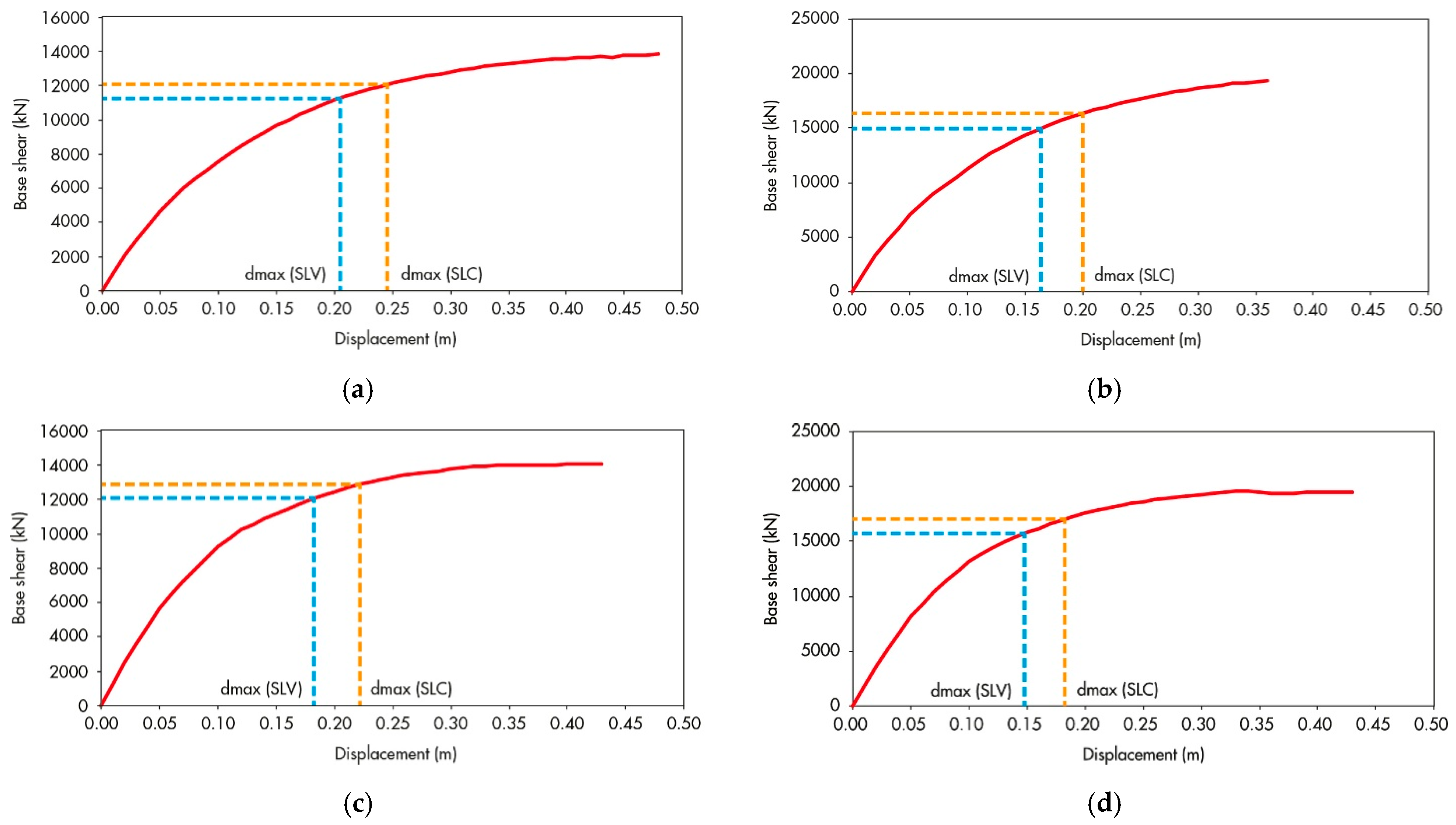

- Definition of a generalized force–displacement relationship between the resultant of applied forces (base shear, ) and the displacement () at the control point, located at the center of mass of the top floor;

- Derivation of an equivalent bilinear single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) system representing the global response;

- Evaluation of the maximum displacement of the equivalent SDOF system using the displacement spectrum corresponding to the considered limit state;

- Conversion of the SDOF displacement to the actual displacement configuration of the structure;

- Verification of displacement compatibility (for ductile elements/mechanisms) and strength capacity (for brittle elements/mechanisms).

- Intrinsic structural damping (): the inherent damping of a structure in the elastic range, typically assumed to be 5%.

- Hysteretic damping (): related to the plastic behavior of the structure. This component is zero in the case of purely elastic response.

- Additional viscous damping (): provided by the viscous dissipation systems installed in the structure. This component is zero when the structure is equipped with hysteretic or friction-based dissipative devices.

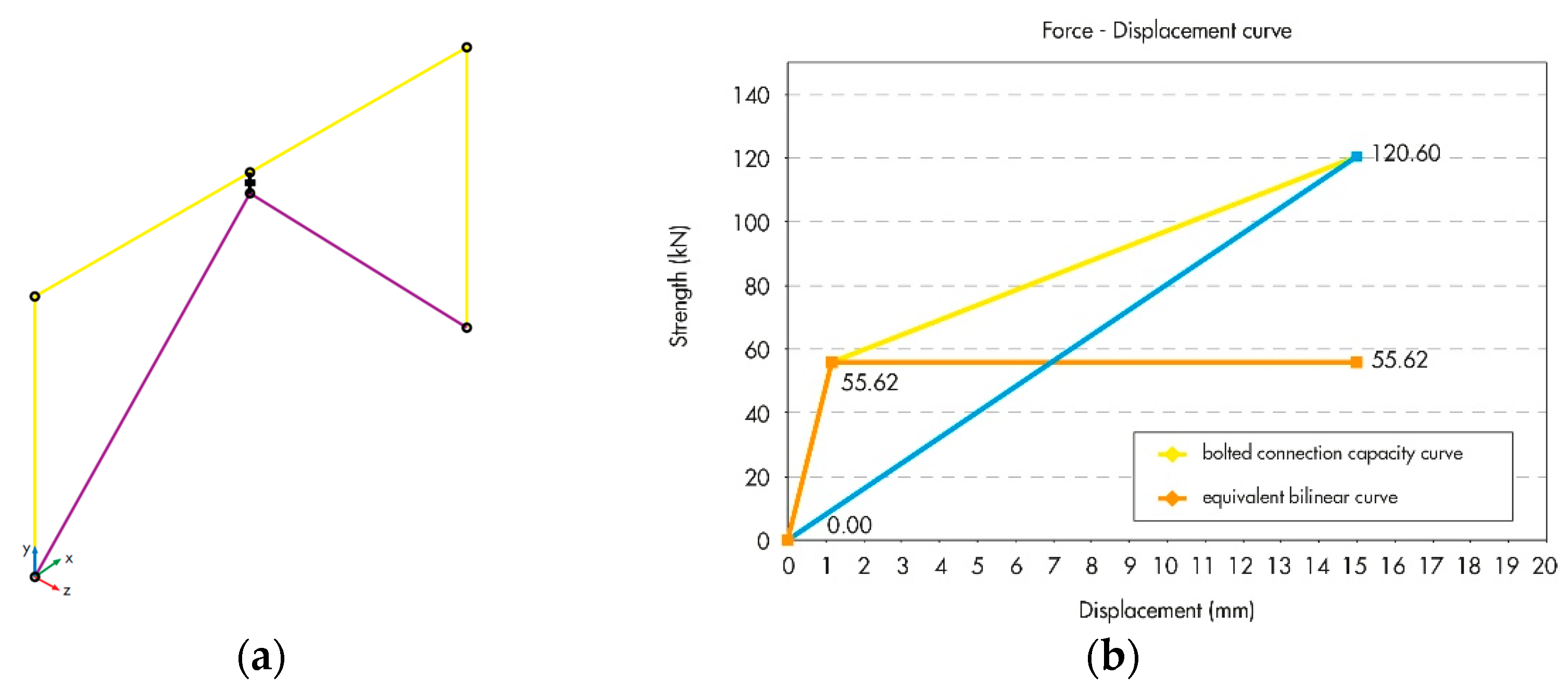

5.2. Phase 2: Innovative Dissipative System

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omidvar, B.; Golestaneh, M.A.; Abdollahi, Y. A framework for post-earthquake rapid damage assessment of hospitals. Case study: Rasoul-e-Akram Hospital (Tehran, Iran). Environ. Hazards 2014, 13, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Noori, M. Seismic Resilience Assessment of Hospital Infrastructure, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lupoi, A.; Cavalieri, F.; Franchin, P. Component Fragilities and System Performance of Health Care Facilities. In SYNER-G: Typology Definition and Fragility Functions for Physical Elements at Seismic Risk; Pitilakis, K., Crowley, H., Kaynia, A., Eds.; Geotechnical, Geological and Earthquake Engineering; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirekar, J.; Badge, A.; Bandre, G.R.; Shahu, S. Disaster Preparedness in Hospitals. Cureus 2023, 15, e50073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.A.; Lin, L. Impact of Facility Damages on Hospital Capacities for Decision Support in Disaster Response Planning for an Earthquake. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2009, 24, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, S.; Kulatunga, U.; Udeaja, C.; Valadi, S. Implementing GIS to improve hospital efficiency in natural disasters. ISPRS—Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-3/W4, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayas, V.; Mokha, A.; Low, S. Constructing Hospitals for Functionality after Earthquakes: Saves Lives and Costs! Buildings 2023, 13, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokha, A. Seismic Isolation Design for Achieving Post-Earthquake Functionality. In Proceedings of the IABSE Congress New Delhi 2023 on “Engineering for Sustainable Development”, New Delhi, India, 20–22 September 2023; p. 1331. [Google Scholar]

- Boroschek, R.L. Seismic vulnerability of the healthcare system in El Salvador and recovery after the 2001 earthquakes. In Natural Hazards in El Salvador; Rose, W.I., Bommer, J.J., López, D.L., Carr, M.J., Major, J.J., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004; Volume 375. [Google Scholar]

- Tokas, C. Nonstructural Components and Systems-Designing Hospitals for Post-Earthquake Functionality. In Proceedings of the Architectural Engineering Conference (AEI), Oakland, CA, USA, 30 March–2 April 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbianelli, G.; Perrone, D.; Brunesi, E.; Monteiro, R. Seismic acceleration and displacement demand profiles of non-structural elements in hospital buildings. Buildings 2020, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Reinhorn, A. Exploring the concept of seismic resilience for acutecare facilities. Earthq. Spectra 2007, 23, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.J.; Dickerson, A.; Lindell, M.K. Nonstructural seismic preparedness of Southern California hospitals. Earthq. Spectra 2001, 17, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalarca, B.; Perrone, D.; Filiatrault, A.; Nascimbene, R.; Blasi, G.; Aiello, M.A. Braceless Seismic Restraint for Suspended Nonstructural Elements: Concept, Design, and Numerical and Experimental Assessment. J. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.J.; Rodriguez, D.; Peloso, S.; Brunesi, E.; Perrone, D.; Filiatrault, A.; Nascimbene, R. Experimentally Calibrated Numerical Modeling for Performance-Based Seismic Design of Low-Frequency Rocking Electrical Cabinets. J. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.J.; Perrone, D.; Nascimbene, R.; Filiatrault, A. Performance-based seismic classification of acceleration-sensitive non-structural elements. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 4222–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R. Investigation of seismic damage to existing buildings by using remotely observed images. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 161, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Arkan, E.; Radu, D.; Özcan, Z. Seismic Performance and Failure Mechanisms of Reinforced Concrete Structures Subject to the Earthquakes in Türkiye. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocakaplan Sezgin, S.; Sakcalı, G.B.; Özen, S.; Yıldırım, E.; Avcı, E.; Bayhan, B.; Çağlar, N. Reconnaissance report on damage caused by the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes in reinforced-concrete structures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Bilgin, H.; Harirchian, E.; Arkan, E. Field Reconnaissance and Earthquake Vulnerability of the RC Buildings in Adıyaman during 2023 Türkiye Earthquakes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, M.; Baballëku, M.; Isufi, B.; Blagojević, N.; Milićević, I.; Brzev, S. Performance of RC cast-in-place buildings during the November 26, 2019 Albania earthquake. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 5427–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R.; Brunesi, E.; Sisti, A. Expeditious numerical capacity assessment in precast structures via inelastic performance-based spectra. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, G.; Ercolino, M.; Petrone, C.; Coppola, O.; Manfredi, G. The Emilia earthquake: Seismic performance of precast reinforced concrete buildings. Earthq. Spectra 2014, 30, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Arêde, A.; Varum, H. A review of the performance of infilled rc structures in recent earthquakes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavese, A.; Lanese, I.; Nascimbene, R. Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of an Infilled Reinforced Concrete Frame Structure Designed for Gravity Loads. J. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 21, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Pavese, A. Mechanical model for seismic response assessment of lightly reinforced concrete walls. Earthq. Struct. 2016, 11, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, T. Field Observations and Assessment of Performance Level of Steel Structures After the Kahramanmaras Earthquake Sequence of 2023. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Behaviour of Steel Structures in Seismic Areas, STESSA 2024, Salerno, Italy, 10 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Iyama, J.; Matsuo, S.; Kishiki, S.; Ishida, T.; Azuma, K.; Kido, M.; Iwashita, T.; Sawada, K.; Yamada, S.; Seike, T. Outline of reconnaissance of damaged steel school buildings due to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. AIJ J. Technol. Des. 2018, 24, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Koyama, T.; Yamada, S.; Iyama, J.; Kishiki, S.; Shimada, Y. Seismic damage to roof and non-structural components in steel school buildings due to the 2011 tohoku earthquake. AIJ J. Technol. Des. 2014, 20, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DMLP Decreto del Ministro dei Lavori Pubblici. Norme tecniche per la progettazione, esecuzione e collaudo degli edifici in muratura e per il loro consolidamento. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana 5 dicembre 1987 n.285. (In Italian)

- DMLP Decreto del Ministro dei Lavori Pubblici del 16 gennaio 1996. Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni in Zone Sismiche. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, 5 febbraio 1996, n. 19. (In Italian)

- Goretti, A.; Inukai, M. Post-Earthquake Usability and Damage Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete Buildings Designed Not According to Modern Seismic Codes. JSPS Short Term Fellowship; Final Report; Servizio Sismico Nazionale, Dipartimento di Protezione Civile: Roma, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Symans, M.D.; Charney, F.A.; Whittaker, A.S.; Constantinou, M.C.; Kircher, C.A.; Johnson, M.; McNamara, R. Energy dissipation systems for seismic applications: Current practice and recent developments. J. Struct. Eng. 2008, 134, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, D.S.; Cinitha, A.; Umesha, P.K.; Iyer, N.R. Enhancing the Seismic Response of Buildings with Energy Dissipation Methods—An Overview. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 2014, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mohankar, M.R. Retrofitting Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 08, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.; Begum, M.; Nasrin, S. Fiber reinforced polymers for structural retrofitting: A review. J. Civ. Eng. 2011, 39, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri, F.; Bellotti, D.; Caruso, M.; Nascimbene, R. Comparative evaluation of seismic performance and environmental impact of traditional and dissipation-based retrofitting solutions for precast structures. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Liu, W.; Masuda, K.; Wang, S.; Huan, S. A comparative study of seismic isolation codes worldwide, part 1 Design Spectrum. In Proceedings of the First European Conference on Earthquake Engineering and Seismology, Geneva, Switzerland, 3–8 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Phung, B.T.; Nguyen, X.D. Comparative Analysis Between the Bridge Standards of USA, EU, Canada, and Vietnam in the Preliminary Design of Seismic Base Isolation. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2024, 482, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Aviram, A.; Trifunovic, M.; Zayas, V.; Mokha, A.; Low, S. Recommended Design Criteria and Implementation Strategies for Seismic Isolation. In Proceedings of the IABSE Congress 2024: Beyond Structural Engineering in a Changing World, San Jose, CA, USA, 25 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sivasubramanian, P.; Manimaran, M.; Vijay, U.P. Implementation of Base-Isolation Technique in the Design of Mega Hospital Building. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2024, 440, 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ademović, N.; Farsangi, E.N. Review of Novel Seismic Energy Dissipating Techniques Toward Resilient Construction. In Automation in Construction Toward Resilience: Robotics, Smart Materials, and Intelligent Systems, 1st ed.; Noroozinejad, E.F., Noori, M., Yang, T., Lourenço, P.B., Gardoni, P., Takewaki, I., Chatzi, E., Li, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 551–5671. [Google Scholar]

- Yaacoub, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Furinghetti, M.; Pavese, A. Evaluating Seismic Isolation Design: Simplified Linear Methods vs. Nonlinear Time-History Analysis. Designs 2025, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, D.; Nascimbene, R.; Marioni, A.; Banfi, M. A Comparative Analysis of International Standards on Curved Surface Isolators for Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteis, G.D.; Mazzolani, F.M.; Panico, S. Seismic Protection of Steel Buildings by Pure Aluminium Shear Panels. In Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–6 August 2004; p. 2704. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, D.; Diaferio, M.; Nobile, R. Optimal design of a new seismic passive protection device made in aluminium and steel. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2010, 35, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualla, I.H.; Nielsen, L.O.; Chouw, N.; Belev, B.; Liao, W.; Loh, C.; Agrawal, A. Enhanced response through supplementary friction damper devices. In Wave 2002: Wave Propagation—Moving Load—Vibration Reduction, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zizi, M.; Bencivenga, P.; Di Lauro, G.; Laezza, G.; Crisci, P.; Frattolillo, C.; De Matteis, G. Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Existing Italian Hospitals: The Case Study of the National Cancer Institute “G. Pascale Foundation” of Naples. Open Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 15, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokas, C.; Lobo, R.M. Risk Based Seismic Evaluation of Pre-1973 Hospital Buildings Using the HAZUS Methodology. In Proceedings of the ATC and SEI Conference on Improving the Seismic Performance of Existing Buildings and Other Structures, San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysiriwardena, T.M.; Wijesundara, K.K.; Nascimbene, R. Seismic Risk Assessment of Typical Reinforced Concrete Frame School Buildings in Sri Lanka. Buildings 2023, 13, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguardia, R.; Gigliotti, R.; Braga, F. Multi-Performance Design of Dissipative Bracing Systems Through Intervention Cost Optimization. In Proceedings of the COMPDYN 2019, 7th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Crete, Greece, 24–26 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gandelli, E.; Taras, A.; Distl, J.; Quaglini, V. Seismic Retrofit of Hospitals by Means of Hysteretic Braces: Influence on Acceleration-Sensitive Non-structural Components. Front. Built Environ. 2019, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucuzza, R.; Aloisio, A.; Domaneschi, M.; Nascimbene, R. Multimodal seismic assessment of infrastructures retrofitted with exoskeletons: Insights from the Foggia Airport case study. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 22, 3323–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torunbalcı, N. Seismic Isolation and Energy Dissipating Systems in Earthquake Resistant Design. In Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–6 August 2004; p. 3273. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, E.; Constantinou, M.C. Open-Space Damping System Description, Theory, and Verification. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04016201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Pagani, M.; Beilic, D. Seismic performance of storage steel tanks during the May 2012 Emilia, Italy, Earthquakes. J. Perf. Constr. Facil. 2015, 29, 04014137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretti, A.; Di Pasquale, G. Building inspection and damage data for the 2002 Molise, Italy, earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2004, 20, S167–S190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenti, N.; Cosenza, E.; Dolce, M.; Manfredi, G.; Masi, A.; Samela, L. Performance of school buildings during the 2002 Molise, Italy, earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2004, 20, S257–S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenti, N.; Parisi, F. Learning from construction failures due to the 2009 L’Aquila, Italy, earthquake. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2010, 24, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, A.; Lagomarsino, S.; Mannella, A.; Martinelli, A.; Milano, L.; Parodi, S.; Troffaes, M. Forecasting seismic damage scenarios of residential buildings from rough inventories: A case-study in the Abruzzo Region (Italy). Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2010, 224, 279–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collura, D.; Nascimbene, R. Comparative Assessment of Variable Loads and Seismic Actions on Bridges: A Case Study in Italy Using a Multimodal Approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, D.; Cavalieri, F.; Nascimbene, R. Classification of Italian precast concrete structures. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, R.; Marques, M.; Monteiro, R.; Casarotti, C.; Delgado, R. Evaluation of nonlinear static procedures in the assessment of building frames. Earthq. Spectra 2013, 29, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical Stress-Strain Model for Confined Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegotto, M.; Pinto, P.E. Method of analysis of cyclically loaded RC plane frames including changes in geometry and non-elastic behavior of elements under normal force and bending. In Preliminary Report IABSE; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 1973; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Belleri, A.; Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Pagani, M.; Riva, P. Seismic performance of precast industrial facilities following major earthquakes in the Italian territory. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2015, 29, 04014135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, A.; Morandi, P.; Rota, M.; Manzini, C.F.; da Porto, F.; Magenes, G. Performance of masonry buildings during the Emilia, 2012 earthquake. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 12, 2255–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Chiauzzi, L.; Santarsiero, G.; Liuzzi, M.; Tramutoli, V. Seismic damage recognition based on field survey and remote sensing: General remarks and examples from the 2016 Central Italy earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ludovico, M.; Digrisolo, A.; Graziotti, F.; Moroni, C.; Belleri, A.; Caprili, S.; Carocci, C.; Dall’Asta, A.; De Martino, G.; De Santis, S.; et al. The contribution of ReLUIS to the usability assessment of school buildings following the 2016 central Italy earthquake. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Ed Appl. 2017, 58, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, M.; Di Bucci, D. The 2016–2017 central behavior seismic sequence: Analogies and differences with recent Italian earthquakes. Geotech. Geol. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 46, 603–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M.; Nascimbene, R.; Dubini, P.; D’Angela, D.; Magliulo, G. Experimental Seismic Assessment of Nonstructural Elements: Testing Protocols and Novel Perspectives. Buildings 2022, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slejko, D.; Valensise, G.; Meletti, C.; Stucchi, M. The assessment of earthquake hazard in Italy: A review. Ann. Geophys. 2022, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPCM Ordinanza del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri n. 3274 del 20 marzo 2003. Primi elementi in materia di criteri generali per la classificazione sismica del territorio nazionale e di normative tecniche per le costruzioni in zona sismica. Gazzetta Ufficiale, 8 maggio 2003, n. 105. (In Italian)

- NTC Decreto del Ministro delle Infrastrutture 17 gennaio 2018. Approvazione delle nuove norme tecniche per le costruzioni. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, 20 febbraio 2018, Supplemento Ordinario n. 8. (In Italian)

- DECRETO-LEGGE 6 giugno 2012, n. 74, Interventi urgenti in favore delle popolazioni colpite dagli eventi sismici che hanno interessato il territorio delle province di Bologna, Modena, Ferrara, Mantova, Reggio Emilia e Rovigo, il 20 e il 29 maggio 2012. (In Italian)

- Berman, J.W.; Bruneau, M. Experimental Investigation of Light—Gauge Steel Plate Shear Walls. J. Struct. Eng. 2005, 131, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Akrami, V. An engineered infilled frame: Behavior and calibration. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seismosoft SeismoStruct—A Computer Program for Static and Dynamic Nonlinear Analysis of Framed Structures. 2024. Available online: www.seismosoft.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Spacone, E.; Filippou, F.C.; Taucer, F.F. Fibre beam–column model for non-linear analysis of r/c frames: Part i. formulation. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1996, 25, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spacone, E.; Filippou, F.C.; Taucer, F.F. Fibre beam–column model for non-linear analysis of r/c frames: Part ii. applications. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1996, 25, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, R.M.C.M.; Wijesundara, K.K.; Nascimbene, R.; Bandara, C.S.; Dissanayake, R. Accounting axial-moment-shear interaction for force-based fiber modeling of RC frames. Eng. Struct. 2019, 184, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung-Chan, H.; Yu-Syuan, C. Innovative ECC jacketing for retrofitting shear-deficient RC members. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung-Chan, H.; Chia-Wei, K.; Yi, S. Cast-in-place and prefabricated UHPC jackets for retrofitting shear-deficient RC columns with different axial load levels. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R. An arbitrary cross section, locking free shear-flexible curved beam finite element. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 2013, 14, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency, Fema 356, Prestandard and commentary for the seismic rehabilitation of buildings, ASCE, American Society of Civil Engineers, 1801 Alexander Bell Drive, Reston, Virginia, November 2000.

- EN-1998-3 (2005); Eurocode 8, Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance, Part 3: Assessment and Retrofitting of Buildings. European Committee for Standardization, CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Di Sarno, L.; Di Ludovico, M.; Prota, A. Aspetti di analisi e Progettazione di controventi dissipative per l’adeguamento sismico di strutture esistenti in calcestruzzo armato. Progett. Sismica 2012, 2. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Priestley, M.J.N.; Calvi, G.M.; Kowalsky, M.J. Displacement-Based Seismic Design of Structures; IUSS Press: Pavia, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Concrete | Original | Retrofitted |

|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength [MPa] | 12.97 | 21.20 |

| Tensile strength [MPa] | 1.30 | 2.10 |

| Elastic modulus [MPa] | 122 | 125 |

| Strain at peak stress [m/m] | 1.6927 × 104 | 2.1640 × 104 |

| Unit weight [kN/m3] | 24 | 24 |

| Steel | Existing | New |

| Elastic modulus [MPa] | 2.10 × 105 | 2.10 × 105 |

| Yield strength [MPa] | 371 | 355 |

| Strain hardening parameter | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Initial curvature parameter of the transition curve | 20 | 20 |

| Transition curve coefficient A1 (isotropic hardening in compression parameter) | 18.5 | 18.5 |

| Transition curve coefficient A2 A1 (isotropic hardening in compression parameter) | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Transition curve coefficient A3 (isotropic hardening in tension parameter) | 0 | 0 |

| Transition curve coefficient A4 (isotropic hardening in tension parameter) | 1 | 1 |

| Ultimate strain (or buckling strain) | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Unit weight [kN/m3] | 78 | 78 |

| Type A | Value |

|---|---|

| Initial stiffness in the positive quadrant [kPa] | 93,750 |

| Yield force in the positive quadrant [kNa] | 500 |

| Post-yield hardening ratio in the positive quadrant | 0.01 |

| Initial stiffness in the negative quadrant [kPa] | 93,750 |

| Yield force in the negative quadrant [kN] | −500 |

| Post-yield hardening ratio in the negative quadrant | 0.01 |

| Type B | Value |

| Initial stiffness in the positive quadrant [kPa] | 8000 |

| Yield force in the positive quadrant [kNa] | 100 |

| Post-yield hardening ratio in the positive quadrant | 0.01 |

| Initial stiffness in the negative quadrant [kPa] | 8000 |

| Yield force in the negative quadrant [kN] | −160 |

| Post-yield hardening ratio in the negative quadrant | 0.01 |

| Pushover Curve | (Braces) [%] | (Type A) [%] | (Type B) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pushover fundamental mode | 24.17 | 31.32 | 23.60 |

| Pushover uniform mode | 23.21 | 26.73 | 21.63 |

| Pushover fundamental mode | 23.96 | 37.44 | 25.30 |

| Pushover uniform mode | 25.85 | 36.51 | 25.66 |

| Pushover Curve | Unitary Energy [kN/mm] | Number of Grids | Number of Floors | Total Energy Dissipated [kN/mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transverse direction | 1383.3 | 8 | 10 | 110,667 |

| Longitudinal direction | 1282.1 | 4 | 10 | 51,282 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nascimbene, R.; Bianchi, F.; Brunesi, E.; Bellotti, D. A Global Performance-Based Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Hospital Building Equipped with Dissipative Bracing Systems. Buildings 2025, 15, 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224022

Nascimbene R, Bianchi F, Brunesi E, Bellotti D. A Global Performance-Based Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Hospital Building Equipped with Dissipative Bracing Systems. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224022

Chicago/Turabian StyleNascimbene, Roberto, Federica Bianchi, Emanuele Brunesi, and Davide Bellotti. 2025. "A Global Performance-Based Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Hospital Building Equipped with Dissipative Bracing Systems" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224022

APA StyleNascimbene, R., Bianchi, F., Brunesi, E., & Bellotti, D. (2025). A Global Performance-Based Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Hospital Building Equipped with Dissipative Bracing Systems. Buildings, 15(22), 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224022