Integrated Construction Process Monitoring and Stability Assessment of a Geometrically Complex Large-Span Spatial Tubular Truss System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Overview

3. Detailed Design of Trusses and End-Support Herringbone Column

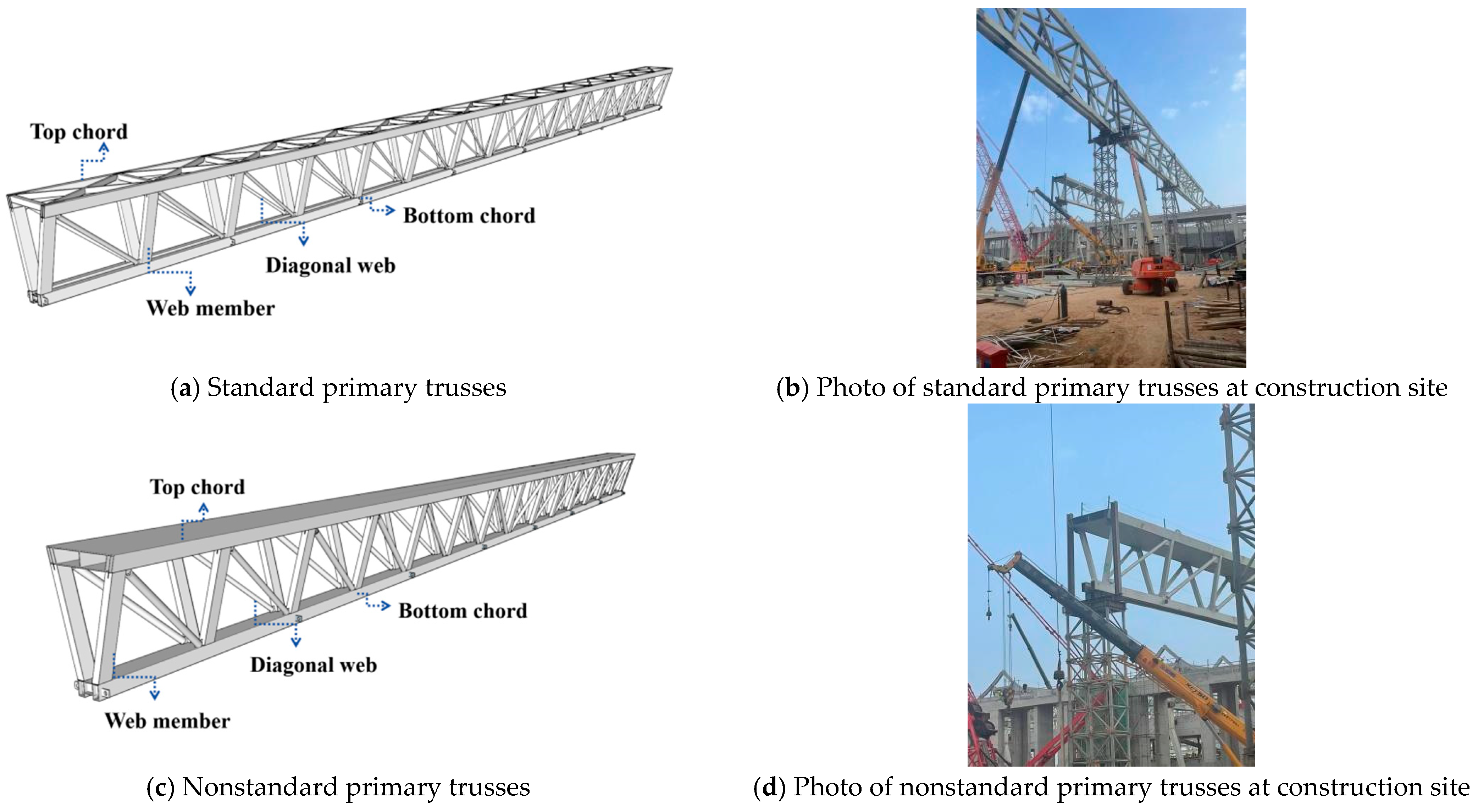

3.1. Design of Standard and Nonstandard Primary Trusses

3.1.1. Standard Primary Truss

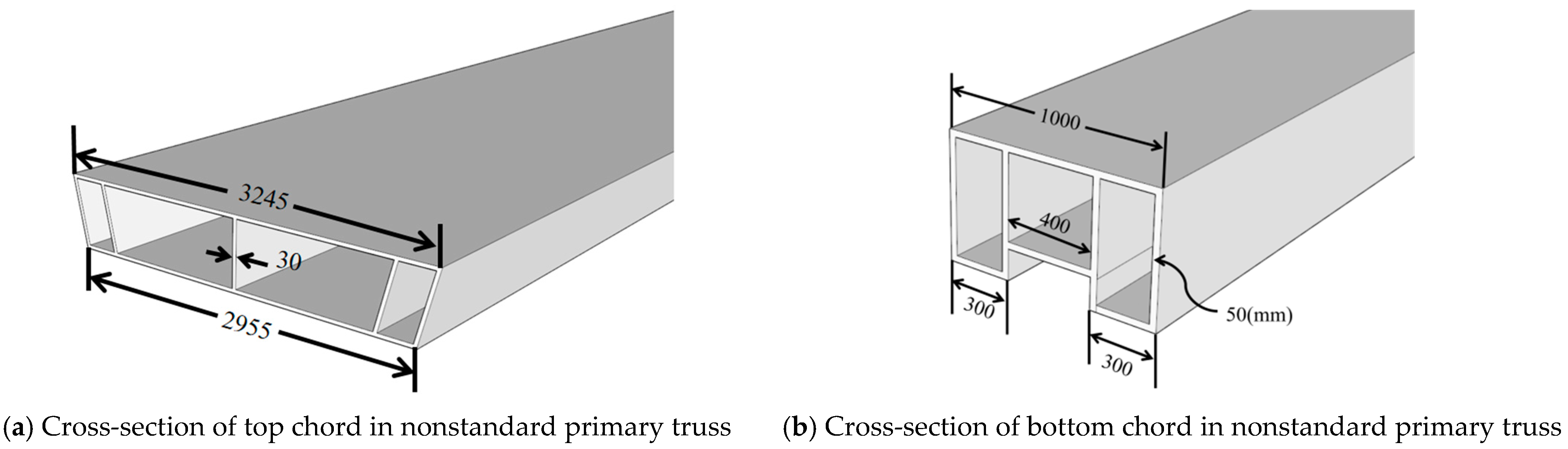

3.1.2. Nonstandard Primary Truss

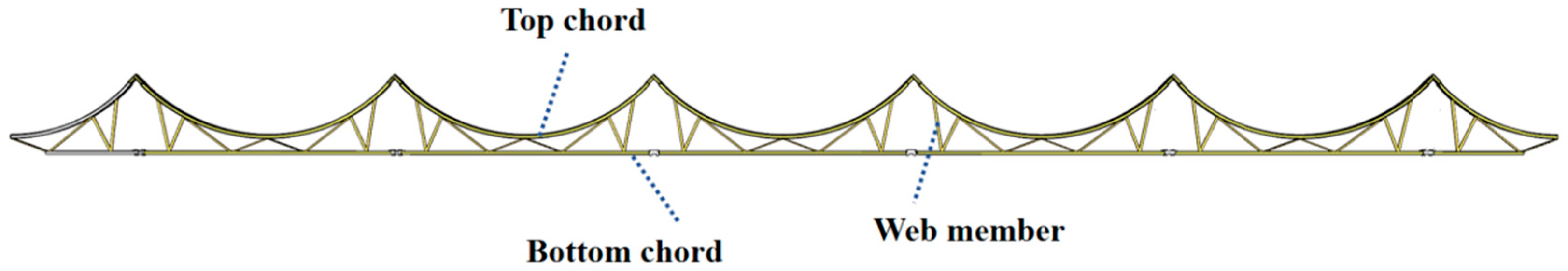

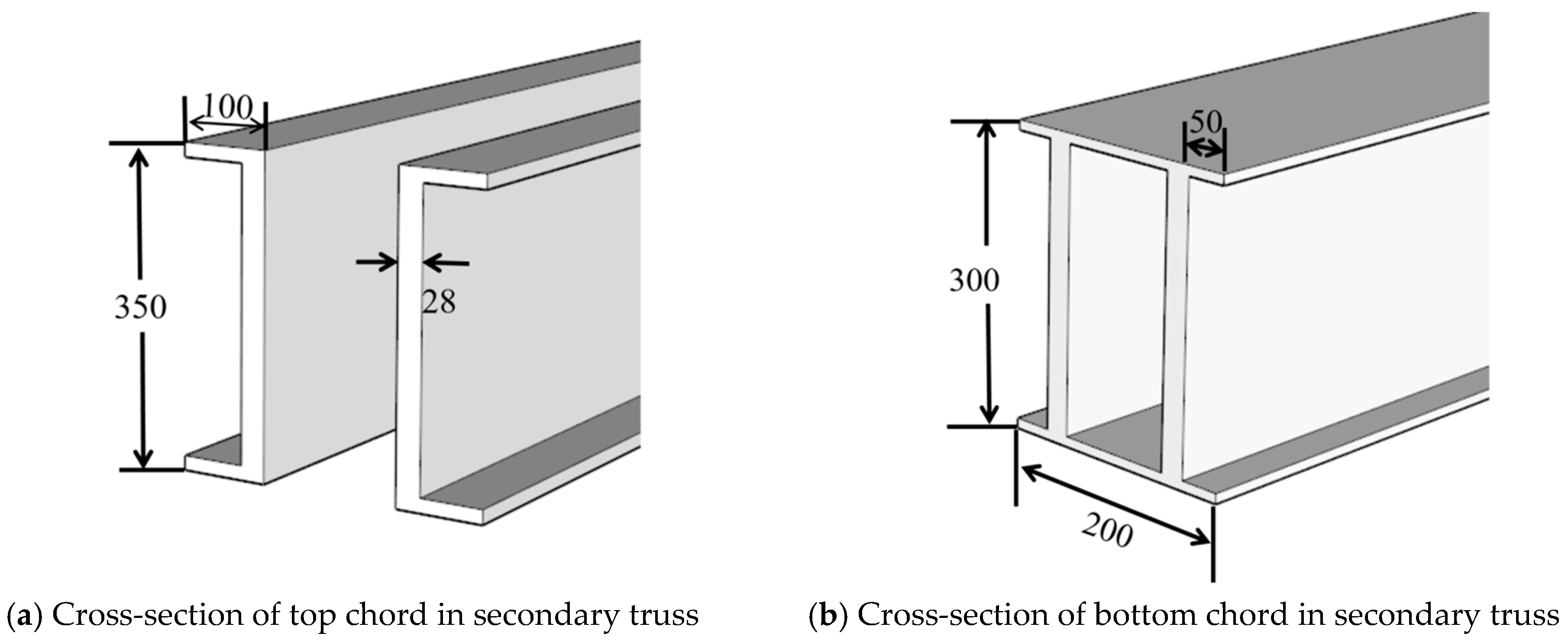

3.2. Design of Secondary Trusses

3.3. Design of End-Support Herringbone Column

4. Steel Structure Installation Procedures

5. Full-Process Numerical Simulation of Construction

5.1. Establishment of Numerical Models

5.2. Dynamic Simulation of Construction Processes

6. Instrumentation Layout and Monitoring Strategy

6.1. Layout of Measurement Points

6.2. Description of Monitoring Instrumentation

6.3. Construction Monitoring Protocol

- (1)

- Installation of RMC-01 photogrammetric systems on observation platforms atop the herringbone column of critical nonstandard trusses No.3 and No.4, ensuring an unobstructed field of view;

- (2)

- Mounting of high-contrast retroreflective targets at predetermined measurement points on the bottom chord surfaces.

7. Validation of Construction Simulation Against Field Monitoring Data

8. Truss Stability Analysis

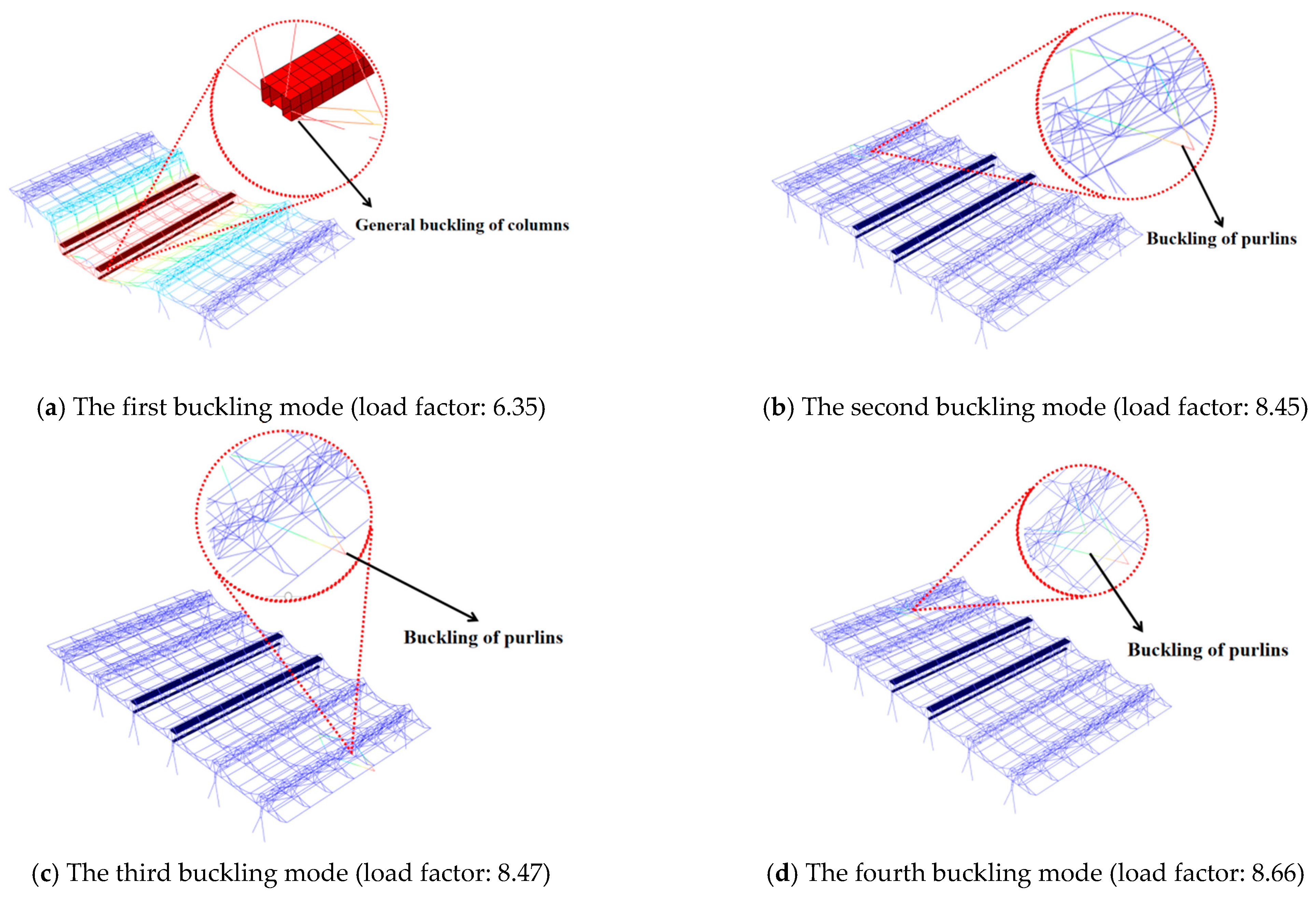

8.1. Eigenvalue Buckling Analysis

- (1)

- Global stability enhancement: Mode 1 (Figure 17a) indicates that nonstandard primary truss end columns initiate destabilization. It is recommended to strengthen lateral restraint systems at the herringbone columns’ upper ends under ultimate load.

- (2)

- Local buckling mitigation: Thin-walled purlins (6 mm thick 350 mm × 200 mm box-sections) require increased sectional stiffness to reduce stress concentrations from welding constraints, accommodate differential truss deflections, and suppress premature local buckling (Modes 2~4).

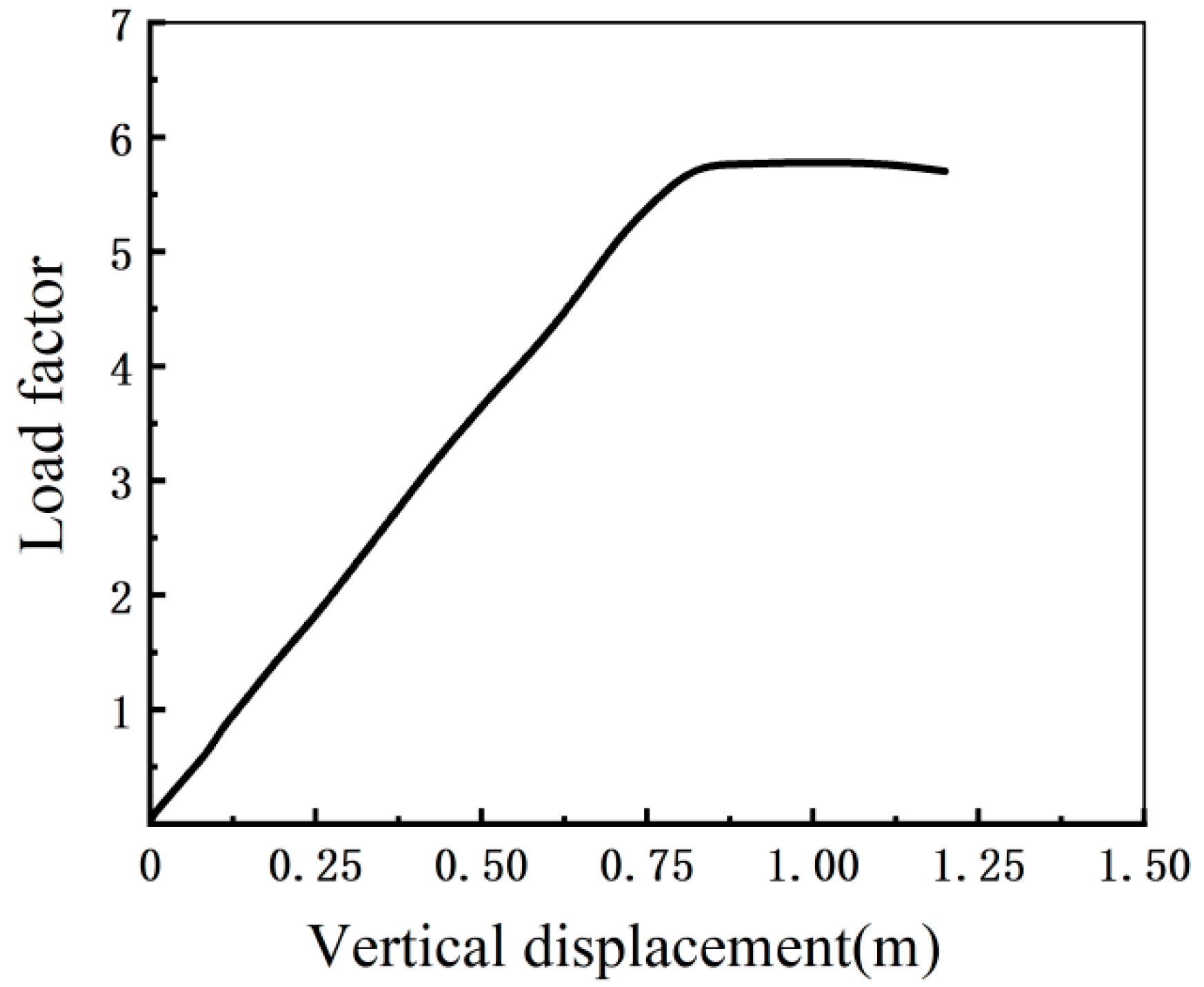

8.2. Geometrically Nonlinear Stability Analysis

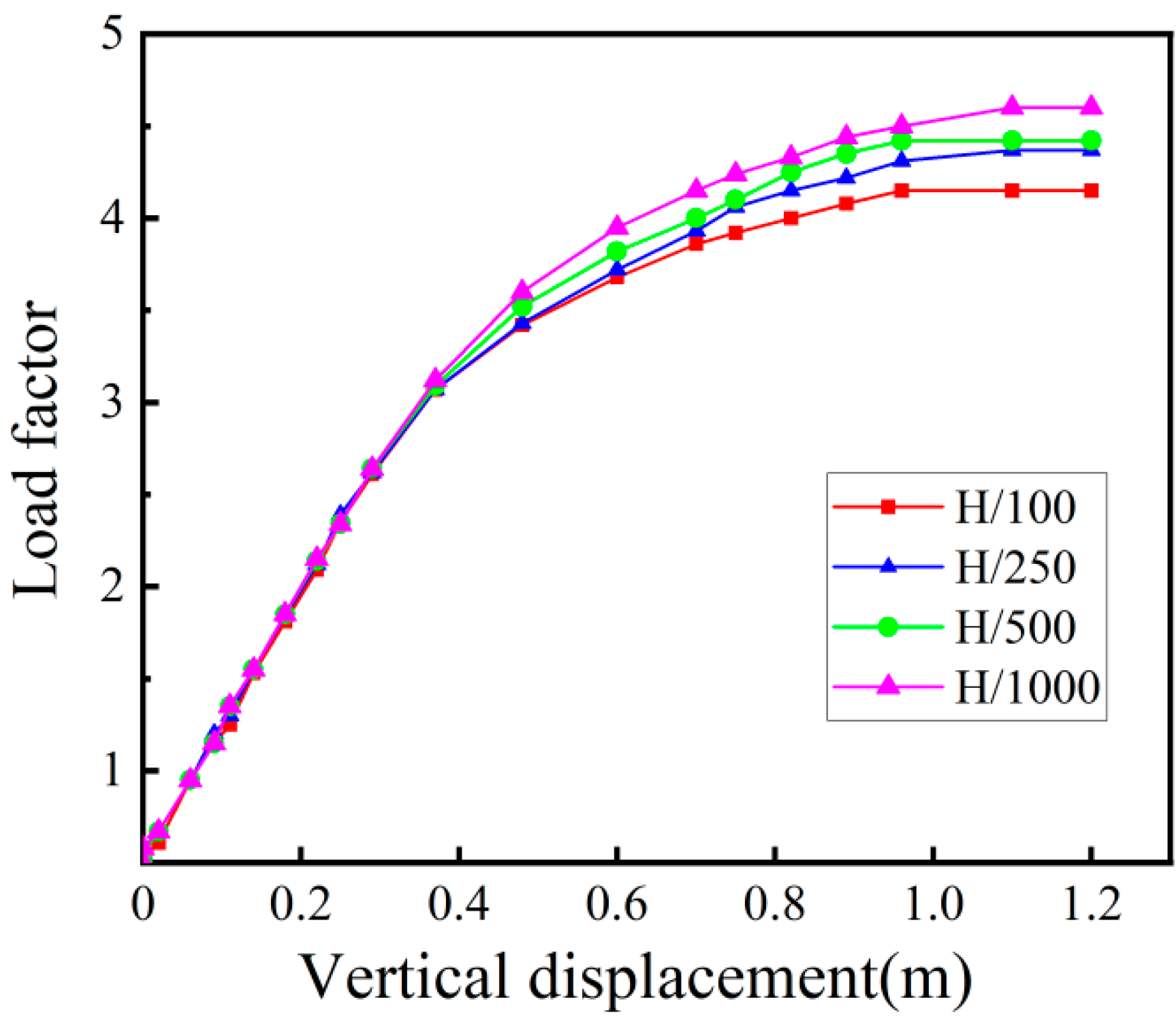

8.3. Analysis of the Effect of Initial Geometric Imperfections

9. Conclusions

- (1)

- The developed structural health monitoring system enables real-time tracking of vertical displacements at critical nodes of nonstandard primary trusses. Close agreement between monitoring data and FEM simulations confirms the accuracy of the numerical model and validates the reliability of the construction scheme. The results provide a robust technical foundation for optimizing the construction and simulation of similar truss structures.

- (2)

- Construction monitoring reveals that primary trusses under long-span and heavy-load conditions exhibit symmetrically parabolic vertical displacement profiles, with mid-span maxima reaching 93 mm and end supports stabilizing at 2–3 mm. This underscores the criticality of mid-span vertical displacement control in such structures. To mitigate deformation, pre-camber adjustments are recommended for comparable projects to achieve targeted compensation.

- (3)

- Linear buckling analysis yields a first-order critical load factor of 6.35, surpassing the minimum threshold of 4.2 and confirming baseline stability. Nonlinear analysis incorporating geometric imperfections of H/100 reduces the buckling load factor to 3.65, showing a 10.9% reduction from the linear result, which still complies with codified stability requirements, demonstrating sufficient safety margins post-construction.

- (4)

- The core methodology of this study—real-time comparison of full-field monitoring data with finite element predictions—constitutes a universally applicable paradigm for large-scale structural control. While specific monitoring metrics may vary across structures (e.g., displacement in roofs, stress in bridge cables, or settlement in stadium foundations), the integrated monitoring system adapts to diverse geometries, and the analytical framework of model validation and updating through real-time data remains consistently applicable. This “monitor-model-compare” logic ensures the direct transferability of our approach to other long-span structures such as stadium roofs and bridges.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, J.D.; Wei, Y.B.; Qiao, M.W. Stress monitoring of long-span steel truss during construction stage in Hangzhou International Expo Center. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 319, 09001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Yu, S.L.; Zhang, X.W.; Yan, J.S.; Chen, X.X. Construction Process Simulation and In Situ Monitoring of Dendritic Structure on Nanjing Niushou Mountain. Shock. Vib. 2019, 1873479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Hao, J.; Wei, J.; Zheng, J. Integral lifting simulation of long-span spatial steel structures during construction. Autom. Constr. 2016, 70, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Chen, B.S.; Bai, R.; Liu, Y.P. Non-Linear Behavior and Design of Steel Structures: Review and Outlook. Buildings 2023, 13, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Lu, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, R. Temperature and Displacement Monitoring to Steel Roof Construction of Shenzhen Bay Stadium. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2016, 16, 1640020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wei, Y.; Qiao, M. Construction monitoring on the unloading process of steel roof for Guilin Liangjiang International Airport Terminal T2. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 319, 09001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Liao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, C. Real-Time Structural Monitoring of the Multi-Point Hoisting of a Long-Span Converter Station Steel Structure. Sensors 2021, 21, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, M.; Kumar, V.; Pal, J.; Sikdar, S.; Banerjee, S.; Banerji, P. A comprehensive review on health monitoring of joints in steel structures. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 073004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Li, R.; Yang, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lei, T. Analysis of Mechanical Properties During Construction Stages Reflecting the Construction Sequence for Long-Span Spatial Steel Structures. Buildings 2024, 14, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabsafa, M.; Fakhimi, R.; Lei, W.; He, S.; Martins, J.R.; Terlaky, T.; Zuluaga, L.F. Truss topology design and sizing optimization with guaranteed kinematic stability. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 63, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Feng, R.; Zhang, Z. Topology optimization of truss structure considering nodal stability and local buckling stability. Structures 2022, 40, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Yu, S.; Luan, W.; Chen, X.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z. The Key Construction Technology Research on the Intercontinental Shanghai Wonderland. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8890282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zeng, F.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, T. Construction Simulation and Monitoring of the Jacking Steel Truss and Main Column of a Super High-Rise Building. Buildings 2024, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.N.; Qin, Z.C.; Guan, C.C.; Feng, D.C.; Wu, G. Bayesian model updating of super high-rise building for construction simulation. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2024, 33, e2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Design and structural analysis of a 70-m metal space-frame radome. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2020, 29, e1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekdaş, G.; Ocak, A.; Nigdeli, S.M.; Toklu, Y.C. A metaheuristic-based method for analysis of tensegrity structures. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2024, 33, e2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, T.; Fan, X.; Zhao, L. Simulation analysis on steel structure erection procedure of the National Stadium. J. Build. Struct. 2007, 28, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, X.L. Simulation and Monitoring of Whole Construction Process of BengbuStadium Large Cantilevered Prestressed Steel Awning Structure. Prog. Steel Build. Struct. 2020, 22, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Xing, G.; Wu, M.; Li, J. Monitoring and simulation analysis of construction process for large spanspatial spoke chord supported truss structure. J. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2023, 40, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Z. Design and whole process simulation analysis for large-span roof steel structure of Xi an SilkRoad International Convention and Exhibition Center. Build. Struct. 2025, 55, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.L.; He, Z.R.; Zhao, J.S. Investigation of internal forces of a truss structure. Structures 2024, 71, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, S. Digital Twin Model and Its Establishment Method for Steel Structure Construction Processes. Buildings 2024, 14, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50017-2017; Standard for Design of Steel Structures. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- AISC 360-10; Specification for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC): Chicago, IL, USA, 2010.

- JGJ 7-2010; Ministry of Housing and Urban—Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Specification for Space Frame Structures. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

| Measurement Points Data | Construction Stage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S13 | S15 | S16 | S17 | S18 | ||

| STL-2 | Simulated Values/mm | −1.8426 | −2.3363 | −63.367 | −80.574 | −78.1374 |

| Measured values/mm | −1.6669 | −2.7162 | −70.569 | −79.6275 | −82.6381 | |

| Deviation/% | 18.07% | −14.81% | −10.3% | 1.19% | −5.48% | |

| STR-2 | Simulated Values/mm | −1.8354 | −64.2866 | −82.1174 | −79.1754 | −78.4462 |

| Measured values/mm | −1.7536 | −66.0528 | −82.7360 | −77.6251 | −76.2787 | |

| Deviation/% | 4.57% | −2.8% | −0.75% | 2.09% | 2.97% | |

| STR-3 | Simulated Values/mm | −3.1080 | −73.0572 | −93.6086 | −90.2246 | −89.3865 |

| Measured values/mm | −2.9181 | −72.9853 | −92.0445 | −85.8273 | −79.5429 | |

| Deviation/% | 6.52% | 0.95% | 1.69% | 5.12% | 12.42% | |

| STL-5 | Simulated Values/mm | −3.9930 | −4.7810 | −37.2473 | −47.6281 | −47.0906 |

| Measured values/mm | −3.3802 | −4.3467 | −32.8419 | −43.5200 | −43.9540 | |

| Deviation/% | 18.04% | 10.13% | 13.39% | 9.42% | 7.14% | |

| GB 50017-2017 | AISC 360-10 | Eurocode | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deflection limits | L/250 | L/240 | No specific regulations. Satisfy serviceability requirements |

| Initial Imperfection Amplitude | H/1000 | H/500 | H/250 | H/100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckling load factors | 4.1 | 3.92 | 3.87 | 3.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Xian, Q. Integrated Construction Process Monitoring and Stability Assessment of a Geometrically Complex Large-Span Spatial Tubular Truss System. Buildings 2025, 15, 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15214000

Hou R, Li H, Zhang H, Wang H, Chen L, Xian Q. Integrated Construction Process Monitoring and Stability Assessment of a Geometrically Complex Large-Span Spatial Tubular Truss System. Buildings. 2025; 15(21):4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15214000

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Ruiheng, Henghui Li, Hao Zhang, Haoliang Wang, Lei Chen, and Qingjun Xian. 2025. "Integrated Construction Process Monitoring and Stability Assessment of a Geometrically Complex Large-Span Spatial Tubular Truss System" Buildings 15, no. 21: 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15214000

APA StyleHou, R., Li, H., Zhang, H., Wang, H., Chen, L., & Xian, Q. (2025). Integrated Construction Process Monitoring and Stability Assessment of a Geometrically Complex Large-Span Spatial Tubular Truss System. Buildings, 15(21), 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15214000