Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Historic Brickwork Masonry with Weak and Degraded Joints: Failure Mechanisms Under Compression and Shear

Abstract

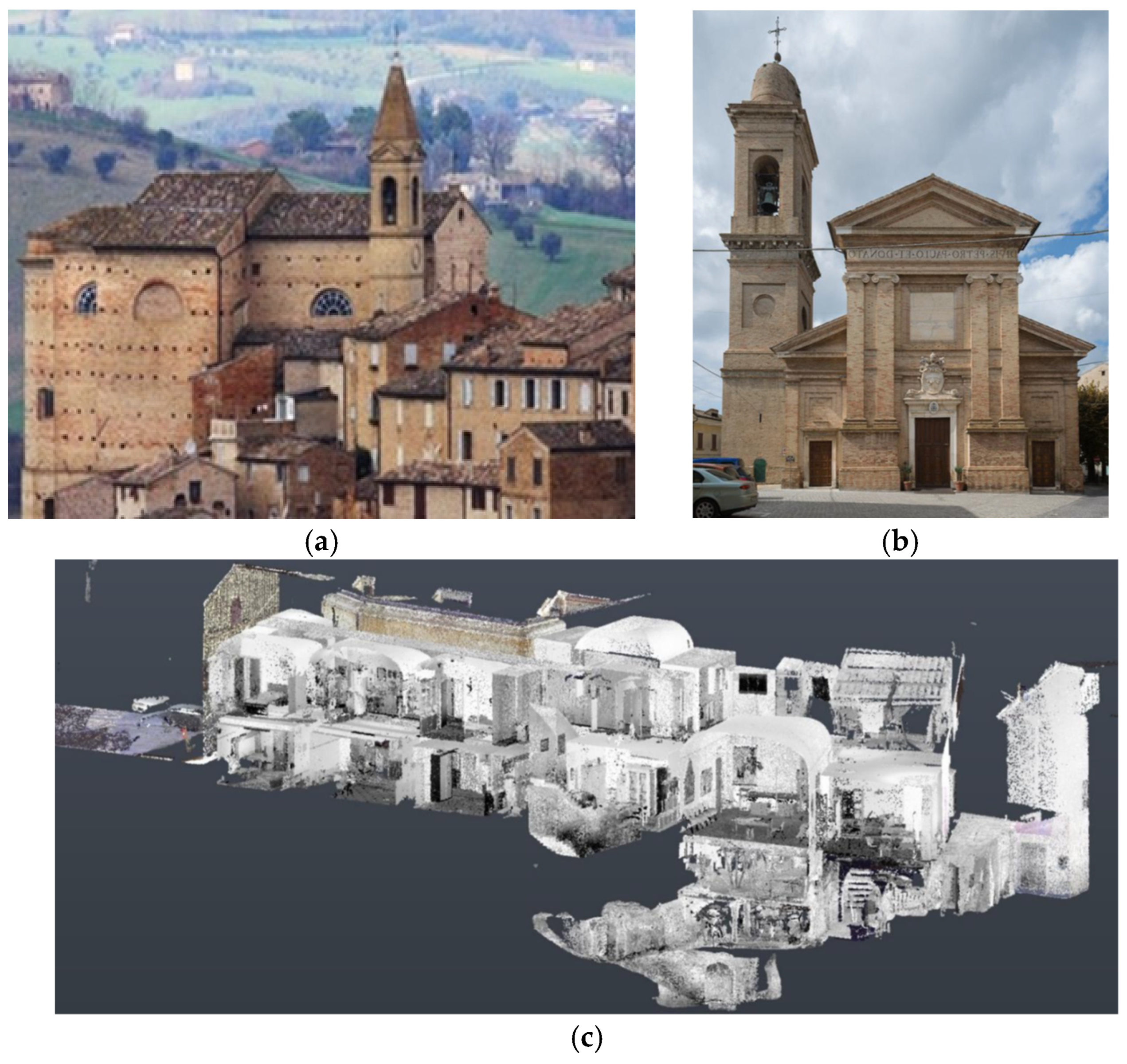

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methodology

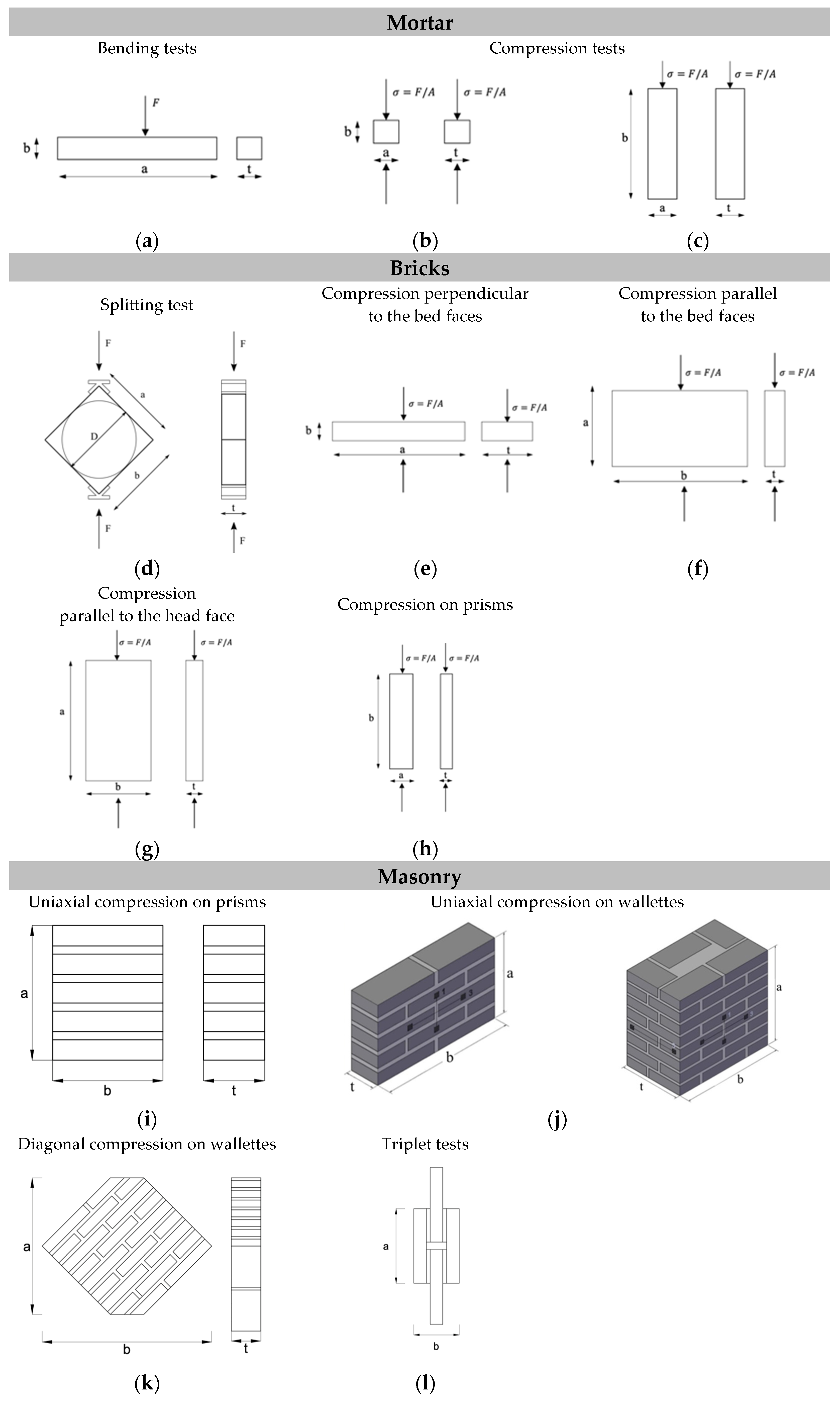

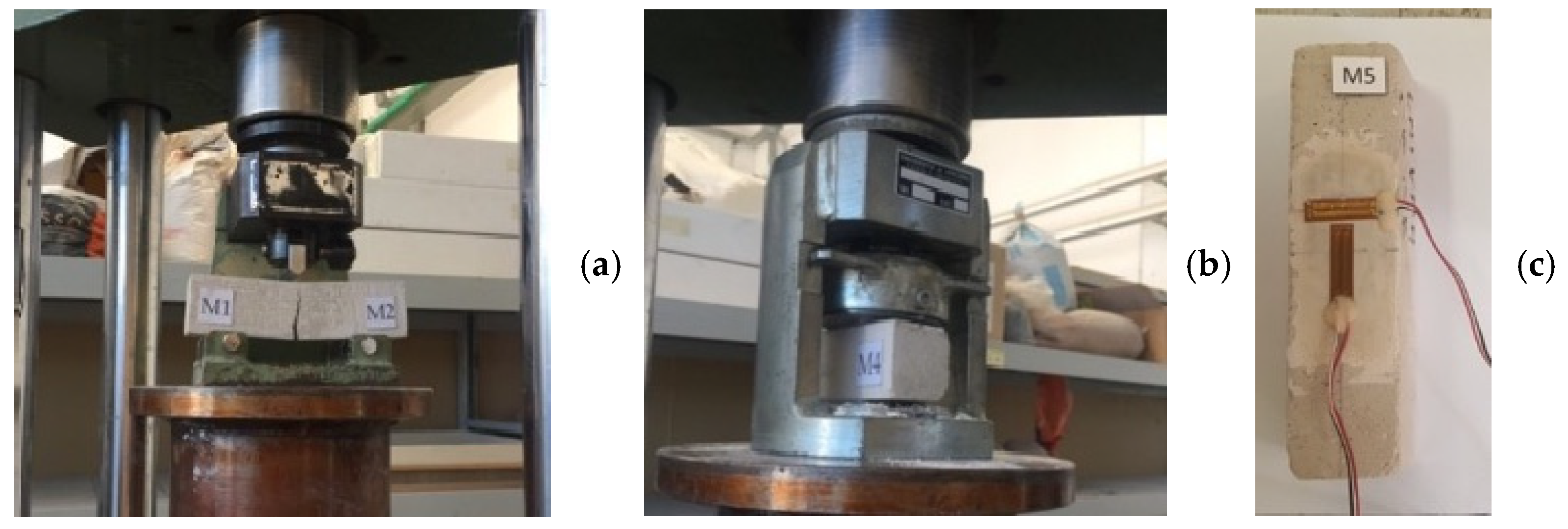

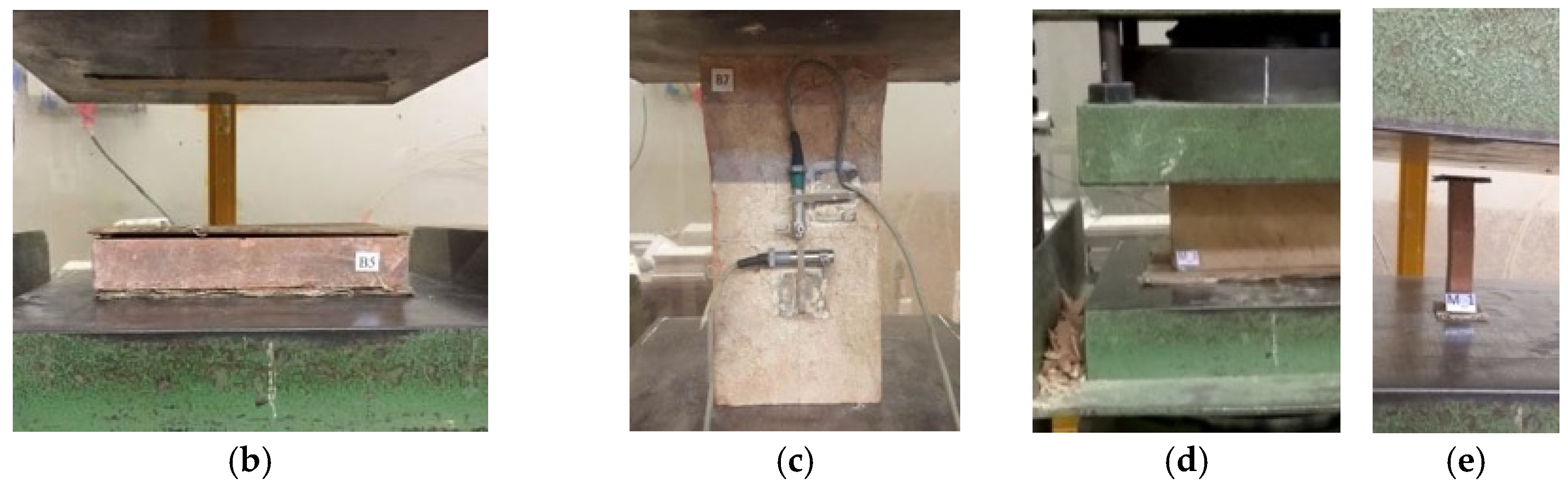

2.1. Experimental Test on Mortars and Bricks

2.2. Compression Tests on Prisms and Wallettes

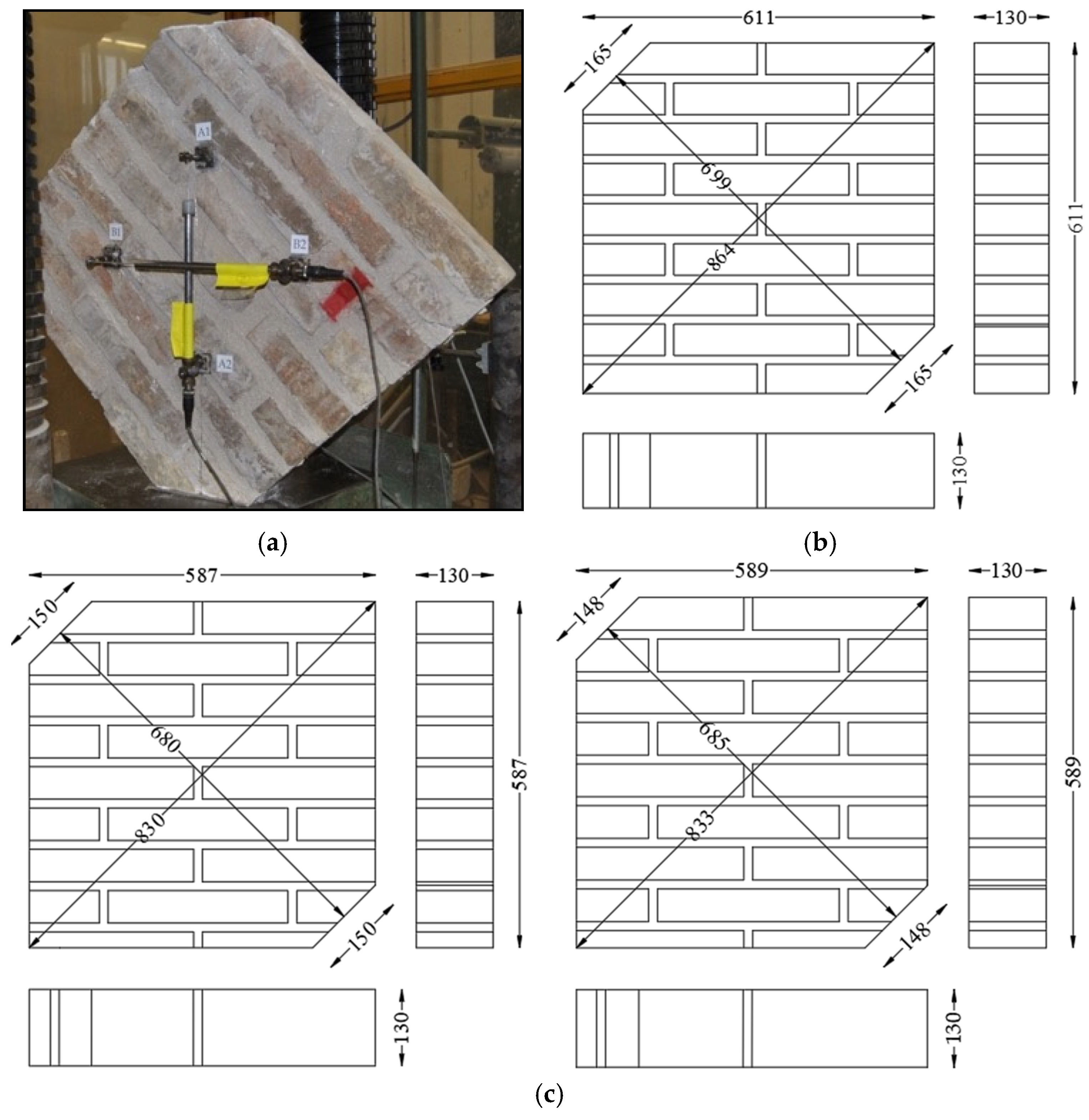

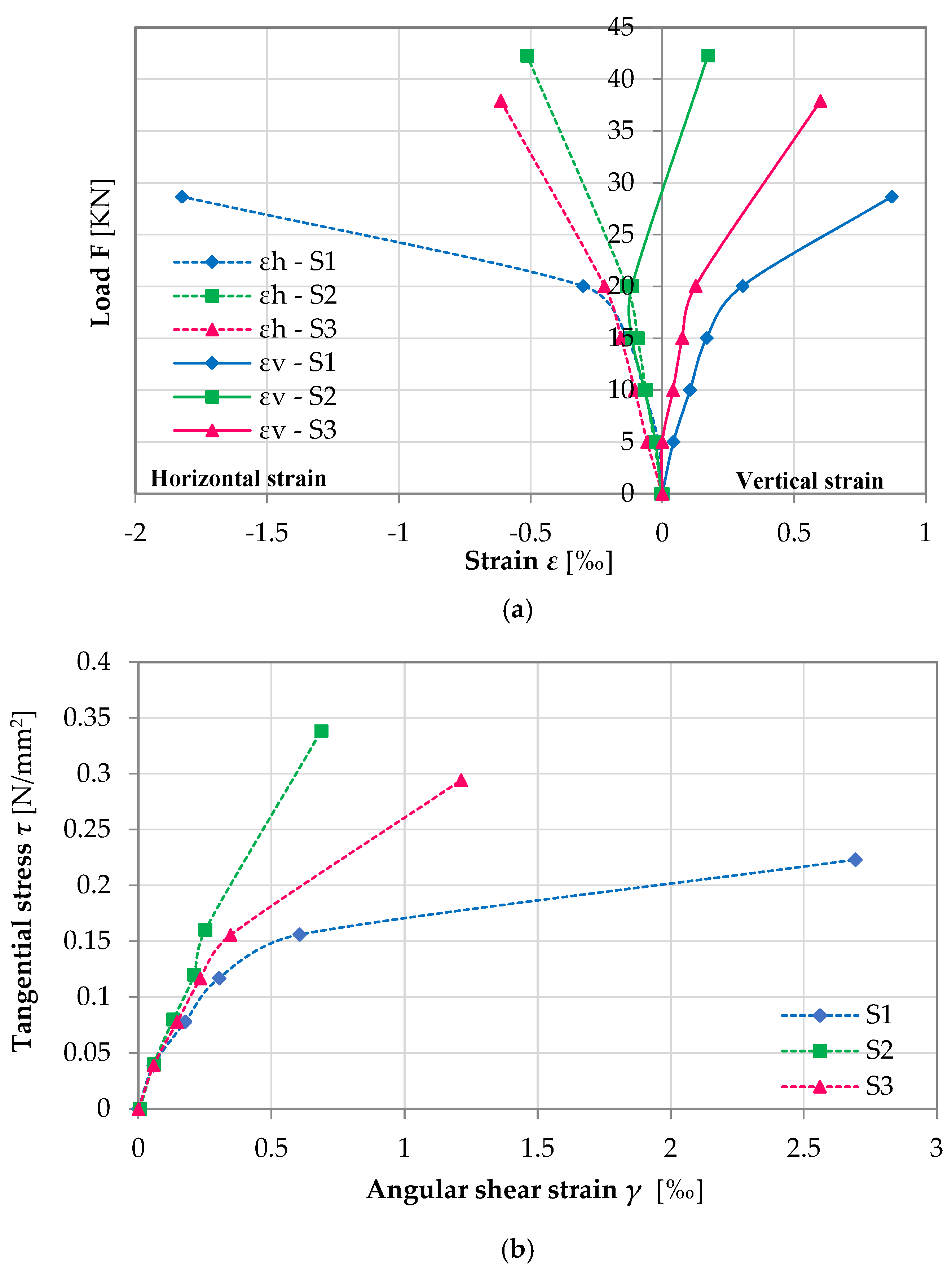

2.3. Diagonal Compression Tests on Brickwork

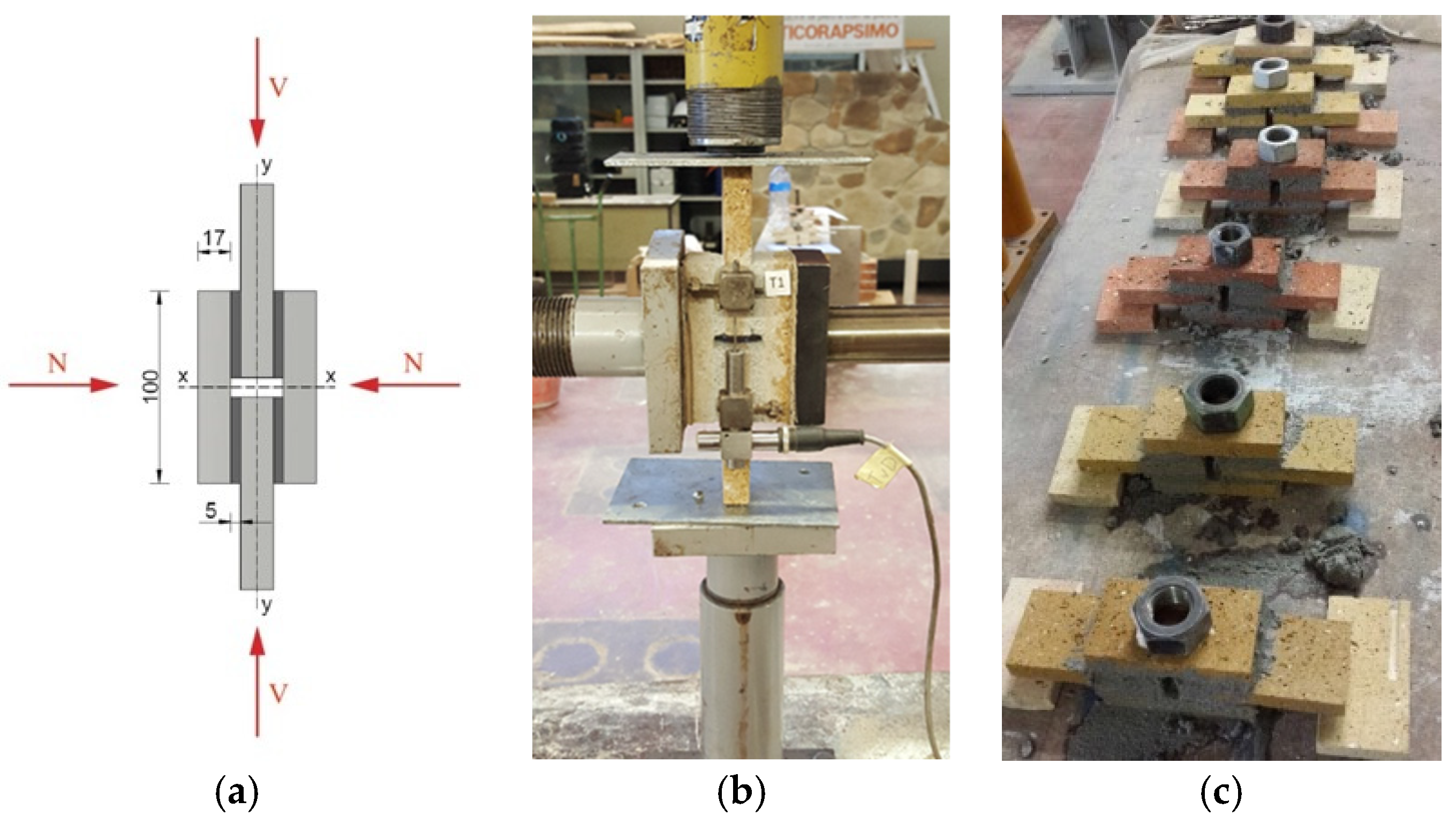

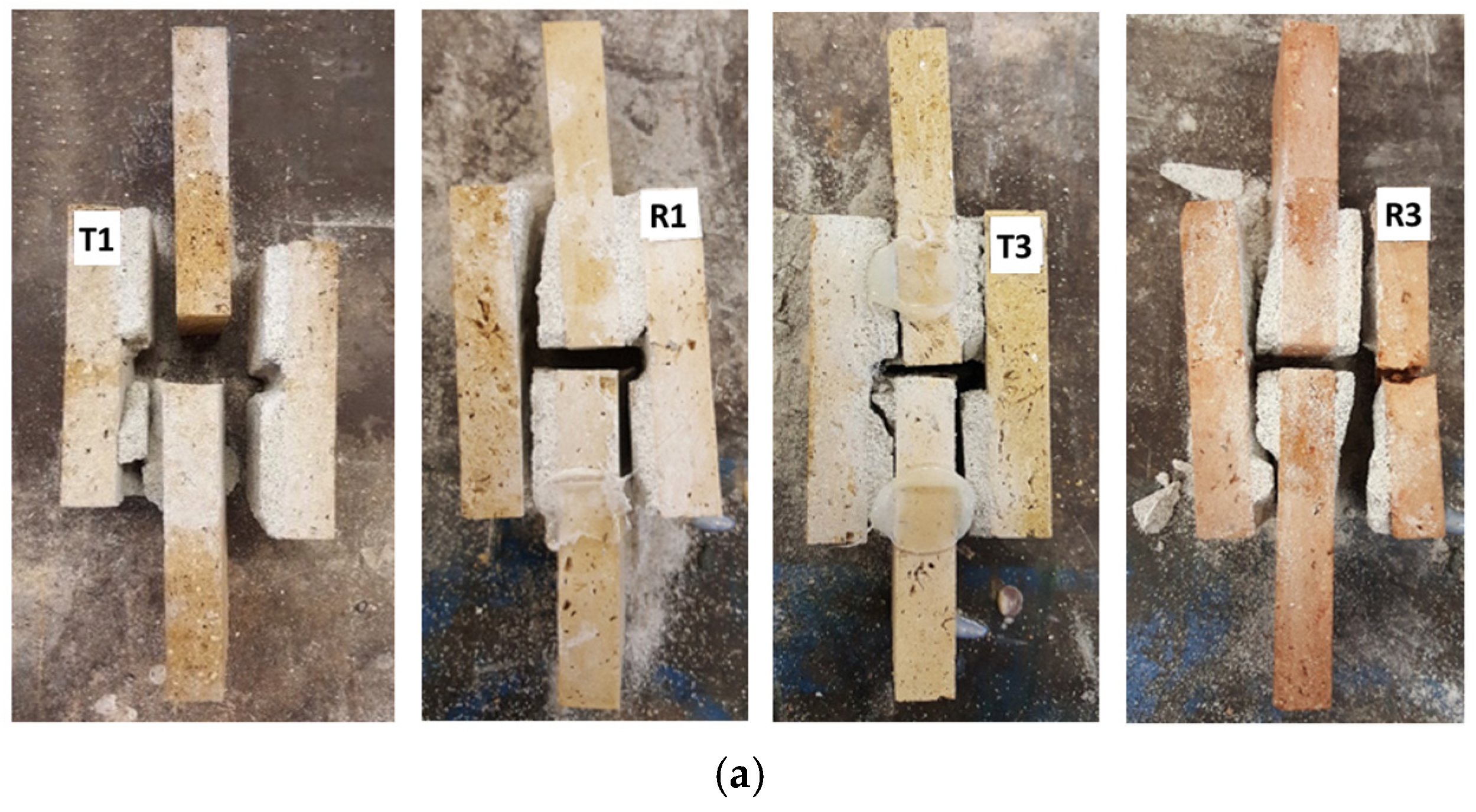

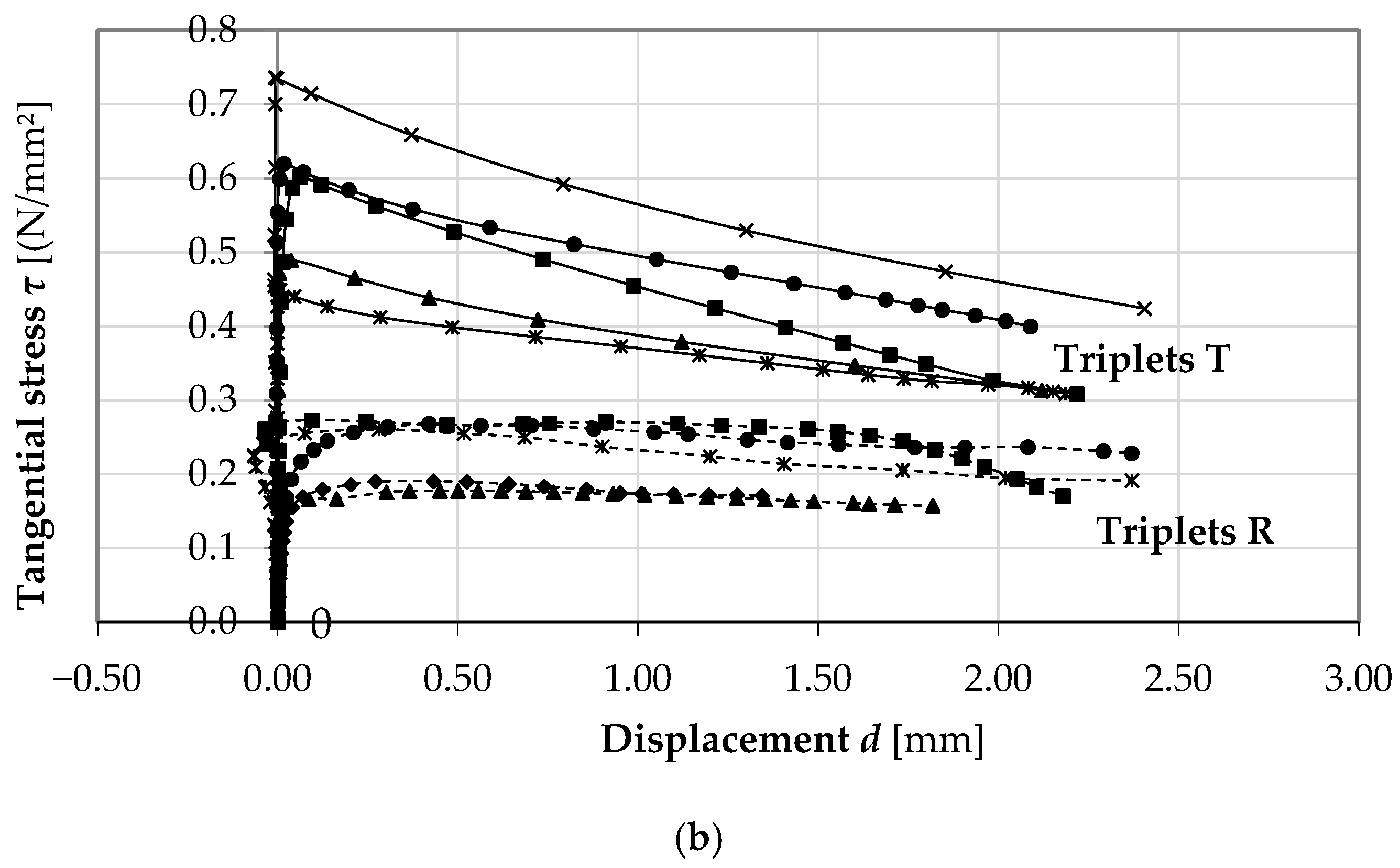

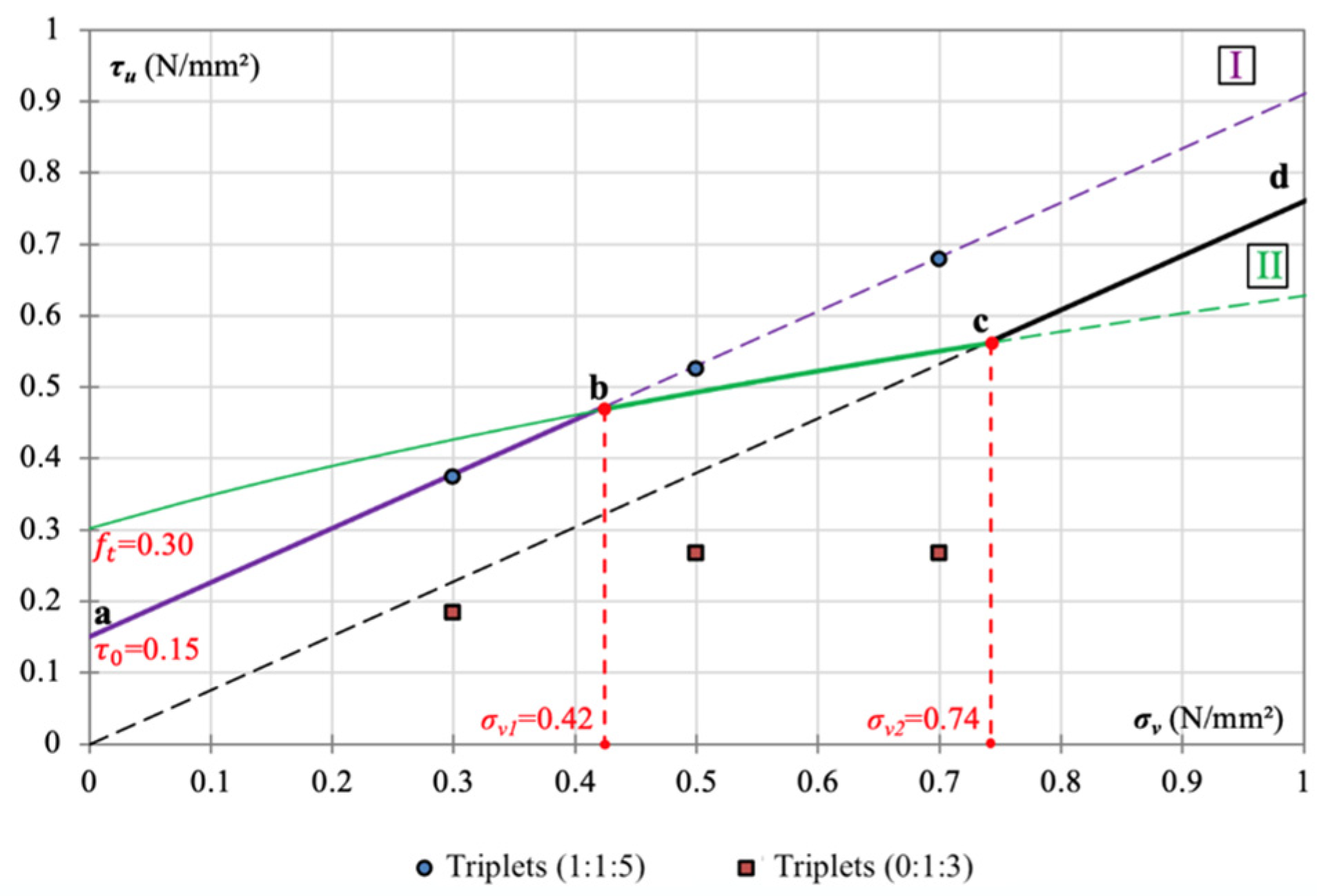

2.4. Triplet Tests

2.5. Summary of Experimental Tests

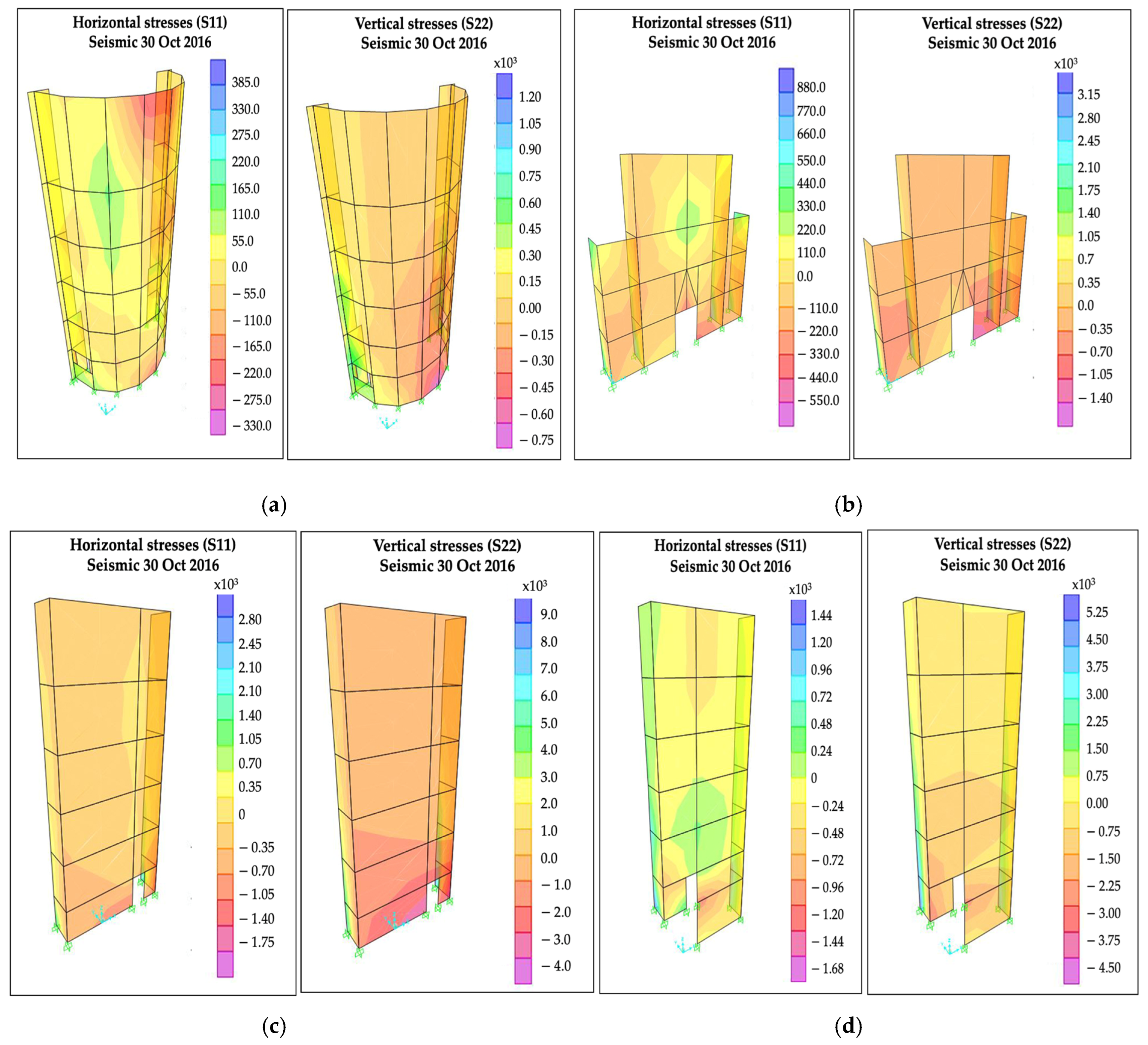

3. Finite Element Modelling Analysis

- Seismic 10%—the seismic action applied at a given point corresponds to 10% of the dead and super dead loads acting at that point;

- Seismic NTC—the magnitude of the forces is derived from the ordinate of the design spectrum corresponding to the fundamental period T1, while their distribution over the structure follows the shape of the fundamental vibration mode in the considered direction, following the procedure given by the Italian Technical Code [30,31];

- Seismic 30 October 2016—the magnitude of the forces is determined as in the previous case, but using the ordinate of the design spectrum obtained from the elastic spectrum of the 30 October 2016 earthquake recorded in Norcia. In this case, the spectral acceleration corresponding to the fundamental period of the structure was extracted from the recorded ground motion and used to define the equivalent static horizontal loads distributed along the height of the structure with a constant vertical step; the corresponding spectral ordinates were adopted to maintain consistency with the linear elastic framework and to enable a direct comparison with the design spectrum of the Seismic NTC case.

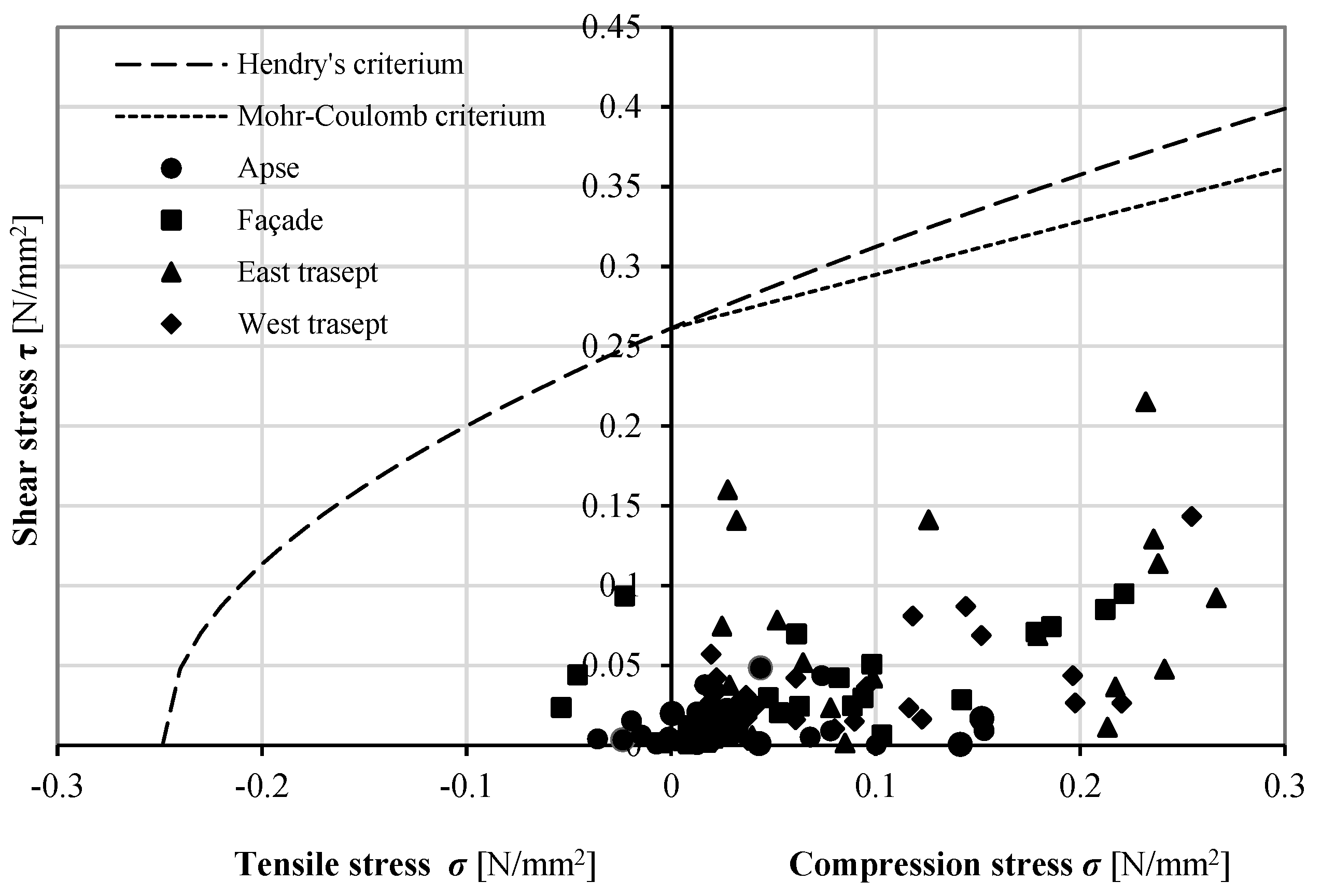

4. Discussion on Failure Mechanisms

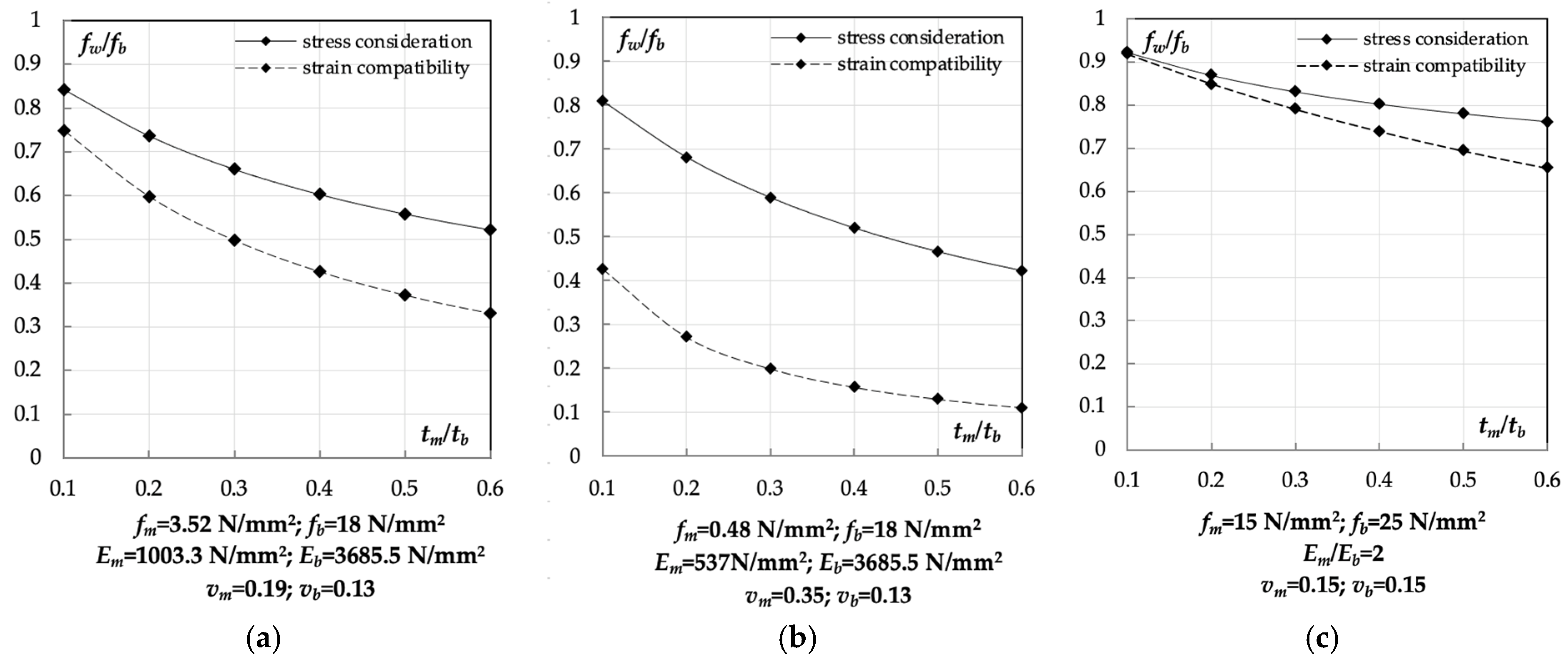

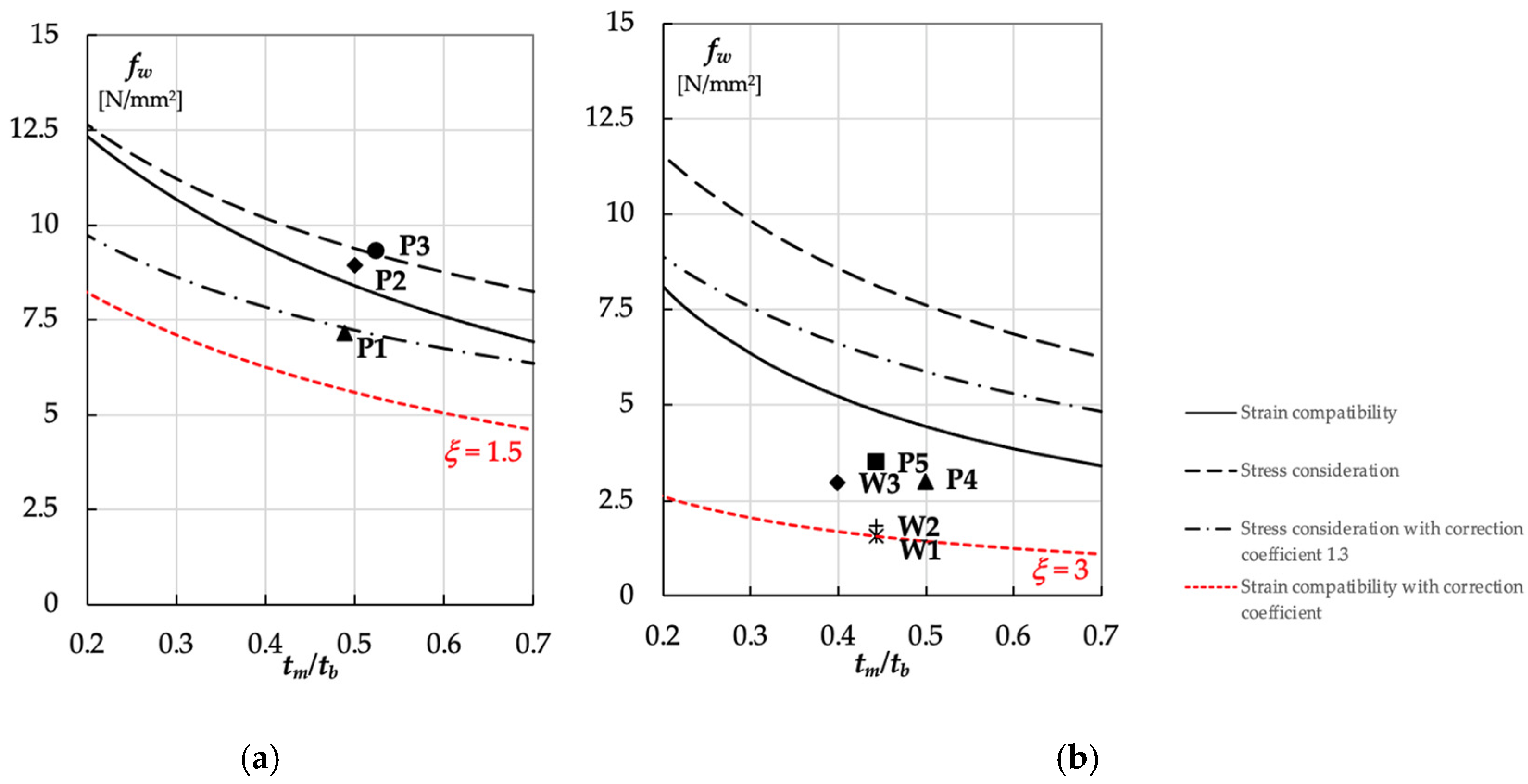

4.1. Tensile and Compressive Mechanisms

4.2. Shear Mechanisms

5. Conclusions

- Historic masonry made with low-strength lime-based mortars exhibits significantly reduced compressive and shear capacity compared to modern brickwork. Joint irregularities and poor mortar cohesion are the main contributors to its vulnerability.

- Compression tests on prisms and wallettes highlighted typical vertical splitting and cracking, confirming the brittle response of masonry with degraded mortar joints.

- Shear triplet tests indicated a three-phase failure criterion (sliding, diagonal cracking, and frictional resistance), which better represents the behaviour of historic masonry than conventional Mohr–Coulomb or Hendry formulations.

- Analytical stress- and strain-based models tend to overestimate the compressive strength of historic masonry. Corrective factors or modified formulations, as proposed in this study, are needed for realistic and conservative predictions.

- Comparison of stress states obtained by FEM with shear failure domains indicated satisfactory safety margins against shear; compressive failure and out-of-plane kinematic mechanisms remain the primary risks for masonry with weak, irregular mortar joints.

- These findings offer practical guidance for engineers and conservation practitioners involved in the assessment and strengthening of historic unreinforced masonry (URM) buildings. The experimentally validated adjustments to classical failure criteria provide more reliable parameters for safety evaluations, while the combined use of laboratory tests, in-situ measurements, and numerical simulations enables a more accurate characterization of mechanical properties and failure mechanisms. This knowledge supports targeted retrofitting solutions—such as mortar joint improvement, compatible grouting, and reinforcement of critical wall connections—aimed at enhancing seismic performance while preserving architectural authenticity.

- Although the FEM modelling approach adopts linear-elastic assumptions and therefore represents a simplification of the structural response, it is consistent with strategies commonly employed in professional practice for large-scale seismic assessment. Moreover, the restricted size of the experimental dataset reflects the limited availability of historic materials. Nonetheless, the integrated experimental–numerical framework establishes a robust foundation for future advancements. Ongoing research will extend the investigation to larger-scale specimens and incorporate cyclic and dynamic testing to more realistically capture seismic effects and degradation processes. These developments are expected to improve predictive seismic modelling and provide a stronger basis for the design of minimally invasive reinforcement interventions. Further efforts will also focus on validating the proposed formulation for compressive strength assessment across a broader dataset, considering material weaknesses, mortar degradation, and variability in masonry textures and bonding patterns.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shabani, A.; Kioumarsi, M.; Zucconi, M. State of the art of simplified analytical methods for seismic vulnerability assessment of unreinforced masonry buildings. Eng. Struct. 2021, 239, 112280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynau, R.; Bru, D.; Ivorra, S. Influence of masonry bonding patterns on the diagonal compressive strength of brick walls. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 179, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzani, A.; Garavaglia, E.; Binda, L. Long-term damage of historic masonry: A probabilistic model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, A.; Corradi, M.; Castori, G.; De Maria, A. A method for the analysis and classification of historic masonry. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 2647–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, F.; Parisi, F.; Lignola, G.P. Material aging effects on the in-plane lateral capacity of tuff stone masonry walls: A numerical investigation. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoni, A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Mattiacci, M.; García-Macías, E.; Saviano, F.; Parisi, F.; Lignola, G.P.; Ubertini, F. Structural performance assessment of full-scale masonry wall systems using operational modal analysis: Laboratory testing and numerical simulations. Eng. Struct. 2024, 304, 117663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, F.; Lignola, G.P.; Parisi, F. Experimental compressive and shear behaviour of clay brick masonry with degraded joints. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 138880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iasio, A.; Briganti, R.; Milani, G.; Ghiassi, B. Numerical and analytical modelling of masonry walls failure under waterborne debris impacts. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluzzi, M.R.; Sbrogiò, L. Vulnerability of Architectural Heritage in Seismic Areas: Constructive Aspects and Effect of Interventions. In Cultural Landscape in Practice; Amoruso, G., Salerno, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Borri, A.; Corradi, M.; De Maria, A. The Failure of Masonry Walls by Disaggregation and the Masonry Quality Index. Heritage 2020, 3, 1162–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, E.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Avcil, F.; Arkan, E.; Ayd, M.C. Damage evaluation of masonry buildings during Kahramanmaraş (Türkiye) earthquakes on February 06, 2023. Earthq. Struct. 2023, 25, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Bilgin, H.; Avcil, F.; İzol, R.; Arkan, E.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Harirchian, E.; Hysenlliu, M. Seismic Performances of Masonry Educational Buildings during the 2023 Türkiye (Kahramanmaraş) Earthquakes. GeoHazards 2024, 5, 700–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, R.; Di Ludovico, M.; Borri, A.; Prota, A. Damage assessment and the effectiveness of prevention: The response of ordinary unreinforced masonry buildings in Norcia during the Central Italy 2016–2017 seismic sequence. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 5609–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis, G.; Vlachaki, E.; Lourenço, P.B. Learning from failure: Damage and failure of masonry structures, after the 2017 Lesvos earthquake (Greece). Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 113, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, D.; Doglioni, C.; AlShawa, O.; Atzori, S.; Sorrentino, L. Effects of coseismic ground vertical motion on masonry constructions damage during the 2016 Amatrice–Norcia (Central Italy) earthquakes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 120, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haladin, I.; Bogut, M.; Lakušić, S. Analysis of Tram Traffic-Induced Vibration Influence on Earthquake Damaged Buildings. Buildings 2021, 11, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, E.E.; Genç, A.F.; Altunişik, A.C.; Günaydin, M.; Sevim, B. Numerical Simulation of Severe Damage to a Historical Masonry Building by Soil Settlement. Buildings 2023, 13, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif-Khouri, E.; Lozano-Martínez, A.; de Rego, J.I.L.; López-Gallego, B.; Forjan-Castro, R. Capillary Rise and Salt Weathering in Spain: Impacts on the Degradation of Calcareous Materials in Historic Monuments. Buildings 2025, 15, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandemeulebroucke, I.; Caluwaerts, S.; Van Den Bossche, N. Factorial Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Freeze-Thaw Damage, Mould Growth and Wood Decay in Solid Masonry Walls in Brussels. Buildings 2021, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhong, W.; Cui, J. Damage assessment method of clay brick masonry load-bearing walls under intense explosions with long duration. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 166, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildorf, H.K. An investigation into the failure mechanism of brick masonry loaded in axial compression. In Designing, Engineering and Constructing with Masonry Products; Gulf Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 1969; pp. 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, B.P.; Hendry, A.W. The behaviour of brickwork in compression. Struct. Eng. 1966, 44, 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Anthoine, A.; Magenes, G.; Magonette, G. Shear-compression testing and analysis of brick masonry walls. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vienna, Austria, 28 August–2 September 1994; pp. 1657–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Calderini, C.; Cattari, S.; Lagomarsino, S. In-plane strength of unreinforced masonry piers. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2009, 38, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.-L.; Shen, J.-X.; Zhong, Z.-L.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.-D.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Damage evolution and failure mechanism of masonry walls under in-plane cyclic loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 161, 108240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medić, S.; Hrasnica, M. In-Plane Seismic Response of Unreinforced and Jacketed Masonry Walls. Buildings 2021, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magenes, G.; Calvi, M. In-plane seismic response of brick masonry walls. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1997, 26, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnsek, Y.; Cacovic, F. Some experimental results on the strength of brick masonry walls. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Brick Masonry Conference, Stoke-on-Trent, UK, 12–15 April 1970; pp. 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, W.; Müller, H. Failure of shear-stressed masonry. Proc. Br. Ceram. Soc. 1980, 27, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- D.M. 14.01.2008; Nuove Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni. Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Circolare n. 617 02.02.2019; Istruzioni per l’Applicazione delle “Nuove Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni”. Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti: Rome, Italy, 2009.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Eurocode 6: Design of Masonry Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules for Reinforced and Unreinforced Masonry Structures; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Acito, M.; Buzzetti, M.; Chesi, C.; Magrinelli, E.; Milani, G. Failures and damages of historical masonry structures induced by 2012 northern and 2016–17 central Italy seismic sequences: Critical issues and new perspectives towards seismic prevention. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 149, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Harirchian, E.; Arkan, E.; Bilgin, H.; Özmen, H.B. Architectural Characteristics and Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of a Historical Masonry Minaret under Different Seismic Risks and Probabilities of Exceedance. Buildings 2022, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Milani, G. Damage assessment and collapse investigation of three historical masonry palaces under seismic actions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 98, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieffo, N.; Formisano, A. The Influence of Geo-Hazard Effects on the Physical Vulnerability Assessment of the Built Heritage: An Application in a District of Naples. Buildings 2019, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceroni, F.; Pecce, M.; Sica, S.; Garofano, A. Assessment of Seismic Vulnerability of a Historical Masonry Building. Buildings 2012, 2, 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gara, F.; Nicoletti, V.; Arezzo, D.; Cipriani, L.; Leoni, G. Model Updating of Cultural Heritage Buildings Through Swarm Intelligence Algorithms. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2023, 19, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezzo, D.; Quarchioni, S.; Nicoletti, V.; Carbonari, S.; Gara, F.; Leonardo, C.; Leoni, G. SHM of historical buildings: The case study of Santa Maria in Via church in Camerino (Italy). Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 44, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivori, D.; Ierimonti, L.; Venanzi, I.; Ubertini, F.; Cattari, S. An Equivalent Frame Digital Twin for the Seismic Monitoring of Historic Structures: A Case Study on the Consoli Palace in Gubbio, Italy. Buildings 2023, 13, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krentowski, J.R.; Knyziak, P.; Pawłowicz, J.A.; Gavardashvili, G. Historical masonry buildings’ condition assessment by non-destructive and destructive testing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 146, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1052-1; Methods of Test for Masonry—Part 1: Determination of Compressive Strength. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- EN 1052-3; Methods of Test for Masonry—Part 3: Determination of Initial Shear Strength. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

- Veiga, M.R. Air lime mortars: What else do we need to know to apply them in conservation and rehabilitation works? Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Bisbikou, K. Investigation of the technology of historic mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, K.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Pardo, E.S.; Hansen, E.; Cazalla, O. Lime mortars for the conservation of historic buildings. Stud. Conserv. 2002, 47, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, P.B.; van Hees, R.; Fernandes, F.; Lubelli, B. Structural Rehabilitation of Old Buildings. In Building Pathology and Rehabilitation; Chapter: Characterization and Damage of Brick Masonry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Thamboo, J.A.; Dhanasekar, M. Correlation between the performance of solid masonry prisms and wallettes under compression. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E111-04; Standard Test Method for Young’s Modulus, Tangent Modulus, and Chord Modulus. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1981.

- ASTM E519-10; Standard Test Method for Diagonal Tension (Shear) in Masonry Assemblages. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Frocht, M.M. Recent advances in photoelasticity. ASME Trans. 1931, 55, 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- RILEM TC 127-MS. Test for masonry materials and structures. Mater. Struct. 1996, 29, 459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, P.B. Computational Strategies for Masonry Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gambarotta, L.; Lagomarsino, S. Damage models for the seismic response of brick masonry shear walls. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1997, 26, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G. Simple homogenization model for the non-linear analysis of in-plane loaded masonry walls. Comput. Struct. 2009, 87, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computers and Structures Inc. SAP2000 Integrated Finite Element Analysis and Design of Structures, Version 25; Computers and Structures Inc.: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023.

- Hendry, A.W.; Sinha, B.P. Mechanical properties of modern masonry materials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 1970, 47, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Capozucca, R. Experimental analysis of bond strength in masonry. Constr. Build. Mater. 2005, 19, 572–578. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1996-1-1; Eurocode 6: Design of Masonry Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules for Reinforced and Unreinforced Masonry Structures. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Sýkora, M.; Diamantidis, D.; Holický, M.; Marková, J.; Rózsás, Á. Assessment of compressive strength of historic masonry using non-destructive and destructive techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymiotis, C.; Gutlederer, B.M. Allowing for uncertainties in the modelling of masonry compressive strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2002, 16, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzany, J.; Cejka, T.; Sykora, M.; Holicky, M. Strength assessment of historic brick masonry. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2016, 22, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozucca, R. Experimental response of historic brick masonry under biaxial loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozucca, R. Shear Behaviour of Historic Masonry Made of Clay Bricks. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 2011, 5 (Suppl. 1-M6), 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, A.W. A note on the strength of brickwork in combined racking shear and compression. Proc. Br. Ceram. Soc. 1978, 27, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

| Specimen | No. | Test Type | Name | Dimensions [mm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | t | ||||

| A 1:1:5 cement:lime:sand | 2 | Bending tests—Figure 2a | MA,BENDING | 160 | 40 | 40 |

| 4 | Compression tests—Figure 2b | MA,COMPRESSION. | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| 1 | Compression tests—Figure 2c | MA,COMPR. PRISMS | 40 | 160 | 40 | |

| B 1:3 lime:sand | 2 | Bending tests—Figure 2a | MB,BENDING | 160 | 40 | 40 |

| 4 | Compression tests—Figure 2b | MB,COMPRESSION | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| 1 | Compression tests—Figure 2c | MB,COMPR. PRISMS | 40 | 160 | 40 | |

| No. | Test Type | Name | Dimensions [mm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | t | |||

| 11 | Splitting test—Figure 2d | B1 | 100 | 100 | 53 |

| B2 | 100 | 100 | 57 | ||

| B3 | 100 | 100 | 55 | ||

| Compression perpendicular to the bed faces—Figure 2e | B4 | 296 | 55 | 147 | |

| B5 | 283 | 50 | 155 | ||

| Compression parallel to the bed faces—Figure 2f | B6 | 148 | 311 | 50 | |

| B7 | 137 | 280 | 44 | ||

| Compression parallel to the head face—Figure 2g | B8 | 240 | 110 | 50 | |

| B9 | 240 | 110 | 50 | ||

| Compression on prisms Figure 2h | B10 | 40 | 100 | 20 | |

| B11 | 40 | 100 | 20 | ||

| No. | Test Type | Name | Dimensions [mm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | t | |||

| 8 | Uniaxial compression on prisms Figure 2i | P1 | 268 | 300 | 150 |

| P2 | 268 | 310 | 155 | ||

| P3 | 293 | 300 | 150 | ||

| P4 | 275 | 305 | 120 | ||

| P5 | 270 | 305 | 122 | ||

| Uniaxial compression on wallettes Figure 2j | W1 | 350 | 580 | 130 | |

| W2 | 350 | 580 | 130 | ||

| W3 | 540 | 580 | 350 | ||

| 3 | Diagonal compression on wallettes Figure 2k | S1 | 699 | 864 | 130 |

| S2 | 680 | 830 | 130 | ||

| S3 | 685 | 833 | 130 | ||

| 11 | Triplet tests Figure 2l Type T mortar 1:1:5 (cement:lime:sand) Type R mortar 1:3 (lime:sand) Y = yellow bricks R = red bricks | T1 (Y) | 100 | 61 | 25 |

| T2 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| T3 (Y) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| T4 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| T5 (Y) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| T6 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| R1 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| R2 (Y) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| R3 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| R4 (Y) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| R5 (R) | 100 | 61 | 25 | ||

| Specimen | Test Type | Mechanical Parameters | Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortar | Bending test | Tensile strength () | EN 1015-11 |

| Compression test | Compressive strength () | ||

| Compressive Young’s modulus () | EN 1926 | ||

| Poisson’s coefficient () | |||

| Brick | Splitting test | Tensile strength () | EN 12390-6 |

| Compression test | Compressive strength () | EN 1015-11 | |

| Compressive Young’s modulus () | EN 1926 | ||

| Poisson’s coefficient () | |||

| Masonry | Compression test Diagonal compression test | Compressive strength () | EN 1052-1 |

| Compressive Young’s modulus () | |||

| Poisson’s coefficient () | |||

| Tensile strength () | EN 1052-3 | ||

| Triplet test | Shear strength () | RILEM TC 127-MS |

| Mortar Types | Aggregate | Binder | Binder: Aggregate Ratios (by Volume) | Water: Binder Ratios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Siliceous sand (grain size 0–0.6 mm) | Portland Cement CEMII 32.5 R Hydraulic lime CL-90 S | 1:1:5 | 0.50 |

| Type B | Siliceous sand (grain size 0–0.6 mm) | Natural hydraulic lime NHL 2 | 1:3 | 0.55 |

| Mortar Type | Tensile Strength [N/mm2] | Compressive Strength [N/mm2] | Young’s Modulus [N/mm2] | Poisson’s Coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min ÷ Max | Average | Min ÷ Max | Average | |||

| MA 1:1:5 | 1.73 ÷ 1.85 | 1.79 (4.75%) | 3.07 ÷ 3.99 2 3.42 3 | 3.52 (9.47%) | 1003.34 | 0.19 |

| MB 1:3 | - 1 | - 1 | 0.43 ÷ 0.65 2 0.33 3 | 0.48 (28.15%) | 537.00 | 0.35 |

| Compressive Strength [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | Young’s Modulus [N/mm2] | Poisson’s Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. value ÷ max value | 24.2 ÷ 31.1 1 | 16.2 ÷ 24.1 2 | 11.2 ÷ 17.7 3 | 17.2 ÷ 18.8 4 | 1.08 ÷ 1.45 | 2769 ÷ 4602 | 0.126 ÷ 0.124 |

| Average value | 27.65 (17.64%) | 20.15 (27.72%) | 14.45 (31.79%) | 18.00 (6.28%) | 1.27 (20.68%) | 3685.5 (35.17%) | 0.13 (1.13%) |

| Specimen | Mortar | a [mm] | b [mm] | t [mm] | Average Mortar Joint’s Thickness [mm] | [mm] | Cross-Section’s Area [mm2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1:1:5 | 268 | 300 | 150 | 20 | 40 | 45,000 |

| P2 | 1:1:5 | 268 | 310 | 155 | 21 | 40 | 48,050 |

| P3 | 1:1:5 | 293 | 300 | 150 | 22 | 45 | 45,000 |

| P4 | 1:3 | 275 | 295 | 120 | 20 | 40 | 35,400 |

| P5 | 1:3 | 270 | 300 | 122 | 20 | 45 | 36,600 |

| W1 | 1:3 | 350 | 580 | 130 | 18 | 45 | 75,400 |

| W2 | 1:3 | 350 | 580 | 130 | 18 | 45 | 75,400 |

| W3 | 1:3 | 540 | 580 | 350 | 18 | 45 | 203,000 |

| Specimen | Mortar | [N/mm2] | [‰] | [‰] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1:1:5 | 8.93 | 1.69 | - | 2961 | 3271 | - |

| P2 | 1:1:5 | 9.30 | 7.49 | 0.43 | 2092 | 2500 | 0.14 |

| P3 | 1:1:5 | 7.14 | 7.10 | 0.58 | 2037 | 1976 | 0.15 |

| P4 | 1:3 | 3.00 | 2.64 | - | 1076 | 1140 | - |

| P5 | 1:3 | 3.50 | 2.99 | - | 778 | 687 | - |

| W1 | 1:3 | 1.56 | 2.29 | 0.25 | 981 | 906 | 0.22 |

| W2 | 1:3 | 1.83 | 2.57 | 0.22 | 892 | 1100 | 0.18 |

| W3 | 1:3 | 2.96 | 3.01 | 0.20 | 1752 | 1567 | 0.24 |

| [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MP1 | 3.50 | 2998.00 | 0.28 |

| MP2 | 1.00 | 800.00 | 0.22 |

| S1 Wallette | S2 Wallette | S3 Wallette | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load [N] | [‰] | [‰] | [N/mm2] | [‰] | Load [N] | [‰] | [‰] | [N/mm2] | [‰] | Load [N] | [‰] | [‰] | [N/mm2] | [‰] |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 5010 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 5010 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 5010 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 10,030 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 10,030 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 10,030 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| 15,040 | −0.14 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 15,040 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 15,040 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| 20,060 | −0.30 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 20,060 | −0.14 | −0.12 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 20,060 | −0.22 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.35 |

| 28,670 | −1.82 | 0.87 | 0.22 | 2.69 | 42,300 | −0.51 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.69 | 37,930 | −0.61 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 1.21 |

| 27,000 | −2.01 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 2.88 | 41,530 | −0.61 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.81 | 37,670 | −0.70 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 1.36 |

| Specimen | First Cracking Load [N] | Ultimate Load [N] | Ultimate Shear Strength [N/mm2] | Shear Modulus of First Cracking [N/mm2] | Shear Modulus [N/mm2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (2) | Equation (3) | |||||

| S1 | 15,040 | 28,670 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 385.71 | 81.66 |

| S2 | 20,060 | 42,300 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 637.37 | 495.00 |

| S3 | 20,060 | 37,930 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 449.56 | 239.02 |

| Average | 18,390 (15.78%) | 36,300 (19.17%) | 0.28 (21.16%) | 0.13 (22.87%) | 490.88 (26.67%) | 271.89 (76.77%) |

| Specimen | Diameter [mm] | Thickness [mm] | Ultimate Load [N] | Tensile Strength [N/mm2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 611 | 130 | 28,670 | 0.24 |

| S2 | 587 | 130 | 42,300 | 0.35 |

| S3 | 589 | 130 | 37,930 | 0.31 |

| Average | - | - | 36,300 (19.17%) | 0.30 (18.57%) |

| Compression Load N | Specimen | Ultimate | Cohesion | Friction Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [N/mm2] | [N] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | |||

| Triplets T (mortar 1:1:5) | 0.30 | 1350.00 | T1 (Y) | 0.26 | 0.37 (40.7%) | 0.15 | 0.76 |

| 1350.00 | T2® | 0.47 | |||||

| 0.50 | 2250.00 | T3 (Y) | 0.59 | 0.51 (22.16%) | |||

| 2250.00 | ®(R) | 0.43 | |||||

| 0.70 | 3150.00 | T5 (Y) | 0.60 | 0.67 (14.78%) | |||

| 3150.00 | T6 (R) | 0.74 | |||||

| Triplets R (mortar 1:3) | 0.30 | 1350.00 | R1 (R) | 0.19 | 0.185 (3.82%) | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| 1350.00 | R2 (Y) | 0.18 | |||||

| 0.50 | 2250.00 | R3 (R) | 0.27 | 0.265 (2.67%) | |||

| 2250.00 | R4 (Y) | 0.26 | |||||

| 0.7 | 3150.00 | R5 (R) | 0.26 | 0.26 |

[N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory destructive tests | ||||||

| Masonry with 1:1:5 mortar | 4.43 (13.6%) | 0.3 (18.6%) | 2363 (21.9%) | 490.88 (26.65%) | 0.15 | 0.76 |

| Masonry with 1:3 mortar | 1.7 (11.3%) | - | 936.5 (6.7%) | - | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| In situ tests | ||||||

| Masonry with good quality materials | 3.50 | - | 2998 | - | - | - |

| Masonry with degraded materials | 1.00 | - | 800 | - | - | - |

| Type of Masonry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [N/mm2] | [kN/m3] | |

| Min-Max | Min-Max | Min-Max | Min-Max | ||

| Caotic stone masonry (pebbles, erratic and irregular stones) | 1 | 0.018 | 690 | 230 | 19 |

| 2 | 0.032 | 1050 | 350 | ||

| Masonry with rough-hewn ashlars, with leaf of limited thickness and internal core | 2 | 0.035 | 1020 | 340 | 20 |

| 0.051 | 1440 | 480 | |||

| Split stone masonry with good texture | 2.60 | 0.056 | 1500 | 500 | 21 |

| 3.80 | 0.074 | 1980 | 660 | ||

| Irregular masonry made of soft stone (tuff, calcarenite, etc.) | 1.4 | 0.028 | 900 | 300 | 13 |

| 2.2 | 0.042 | 1260 | 420 | 16 | |

| Masonry made of regular blocks of soft stone (tuff, calcarenite, etc.) | 2.0 | 0.04 | 1200 | 400 | 13 |

| 3.2 | 0.08 | 1620 | 500 | 16 | |

| Masonry made of squared stone blocks | 5.8 | 0.09 | 2400 | 800 | 13 |

| 8.2 | 0.12 | 3300 | 1100 | 16 | |

| Masonry with solid clay brick and lime mortar | 2.6 | 0.05 | 1200 | 400 | 18 |

| 4.3 | 0.13 | 1800 | 600 | ||

| Masonry with semi-perforated clay block with cement mortar (e.g.: double UNI volume of holes ≤ 40%) | 5.0 | 0.08 | 3500 | 875 | 15 |

| 8.0 | 0.17 | 5600 | 1400 |

| Observations | R2 | Root Mean Square Error | Cross-Validation | Confidence Intervals of the Exponents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.9975 | 0.029 | - 1 | x1: 1.24 ÷1.81 x2: −1.05 ÷ 0.36 |

| [N/mm2] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Tests | Stress Consideration (Equation (8)) | Strain Compatibility (Equation (26)) | Formulation EC6 (Equation (27)) | Proposed Formulation (Equation (28)) |

| 3.00 | 5.26 | 4.32 | 3.21 | 3.01 |

| 3.50 | 6.18 | 4.83 | 3.34 | 3.47 |

| 1.56 | 4.78 | 4.22 | 2.23 | 1.53 |

| 1.83 | 5.18 | 4.46 | 2.49 | 1.88 |

| 2.96 | 6.08 | 4.96 | 3.05 | 2.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magagnini, E.; Nicoletti, V.; Gara, F. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Historic Brickwork Masonry with Weak and Degraded Joints: Failure Mechanisms Under Compression and Shear. Buildings 2025, 15, 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213993

Magagnini E, Nicoletti V, Gara F. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Historic Brickwork Masonry with Weak and Degraded Joints: Failure Mechanisms Under Compression and Shear. Buildings. 2025; 15(21):3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213993

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagagnini, Erica, Vanni Nicoletti, and Fabrizio Gara. 2025. "Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Historic Brickwork Masonry with Weak and Degraded Joints: Failure Mechanisms Under Compression and Shear" Buildings 15, no. 21: 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213993

APA StyleMagagnini, E., Nicoletti, V., & Gara, F. (2025). Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Historic Brickwork Masonry with Weak and Degraded Joints: Failure Mechanisms Under Compression and Shear. Buildings, 15(21), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213993