1. Introduction

Museums have evolved from static guardians of cultural heritage into participatory cultural spaces that, while preserving, interpreting, and disseminating heritage, actively contribute to public education, cultural communication, collective memory, and identity formation in the digital age [

1,

2,

3]. In the digital context, digital cultural experience has become an important means of achieving cultural communication [

4,

5]. Digital culture, characterized by virtualization, interactivity, and data-driven approaches, is reshaping the presentation and dissemination of museum cultural content [

6,

7,

8]. Emerging technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence further break the boundaries of physical exhibitions [

5,

9,

10], driving museums toward immersive and personalized experiences [

11]. Interactive visitor experience design is becoming a key direction for the innovative integration of digital culture and museums.

Although digital transformation brings new opportunities for museum experiences, the diversity of museum types means that interactive visitor experiences in various museums still have significant room for improvement. Archaeological site museums, in particular, face challenges in their digital transformation, including weakened local identity, insufficient emotional resonance, and limited spatial development [

12,

13]. Existing research on physical experiences focuses on optimizing circulation routes in exhibition spaces, creating immersive environments through lighting and sound effects, and on-site delivery of cultural information [

14,

15]. In terms of virtual experiences, research primarily concentrates on technical implementations such as three-dimensional digital modeling, immersive interactions, and virtual tours [

16,

17,

18]. However, the narrative linkage between the two remains insufficient, with virtual experiences often operating independently from physical spaces, lacking systematic correspondence with physical circulation routes and narrative pacing. Some studies attempt to combine physical and virtual elements through mixed reality or digital twin exhibition narrative design [

19,

20,

21], but practical applications still suffer from asynchronization between virtual and physical experiences in temporal and plot progression, as well as insufficient overall narrative continuity. For instance, a comparative study of the physical and virtual exhibitions at the Pitt Rivers Museum revealed that 3D virtual exhibits often become disconnected from the spatial logic and narrative coherence of their physical counterparts, resulting in fragmented visitor experiences [

22]. In the recently developed dual-mode virtual museum of Sanxingdui, researchers acknowledged that although virtual reality museums provide immersive environments, they still lack opportunities for deeper user engagement and cultural learning activities [

23]. Furthermore, Pietroni’s research on multisensory museums pointed out that while several mixed-reality projects excel in enhancing visual and interactive dimensions, they continue to struggle with synchronizing virtual and physical narratives in terms of temporal rhythm and plot progression [

24]. Existing studies and practices therefore indicate persistent challenges in achieving temporal and narrative synchronization between virtual and physical experiences, as well as maintaining overall narrative continuity.

Building upon the above background, this study proposes a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience model for site museums. Based on traditional spatial narrative theory and incorporating Lefebvre’s triadic concept of spatial production, the model extends both temporal and spatial dimensions to construct a narrative experience framework encompassing historical time, virtual time, and real time, as well as physical space, virtual space, and hybrid space. Through spatiotemporal overlapping narratives, the model establishes a deep correspondence between physical environments and virtual experiences, enabling visitors to obtain continuous and semantically coherent cultural experiences within space. The Panlongcheng Site Museum serves as the practical case for this study. The proposed method integrates FAHP weight analysis, space syntax optimization, and FCE feedback. Through design practice, the adaptability and feasibility of the model are validated in optimizing cultural identity and emotional resonance experiences, offering insights into the digital and experiential transformation of site museums. This research focuses on localized cultural experiences, spatiotemporal overlapping narrative pathways, and virtual-physical integration approaches in site museums, addressing the following key questions:

How can deep integration between virtual and physical narratives be achieved in the digital and experiential transformation of site museums?

How can a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience model be constructed to enhance the digital cultural experience of site museums?

How can the connection between physical space and virtual experience be strengthened to realize deep synchronization between narrative and experience?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Museum Experience Design in the Context of Digital Culture

Digital culture drives the diversification of museum media forms, making cultural content expression more multidimensional, immersive, and personalized. Parry [

25] notes that the introduction of digital media transforms museums from static information transmission to dynamic situational simulation, generating multimodal, cross-media perception mechanisms. Giannini and Bowen [

26] further propose the concept of “cultural experience systems,” where immersive media, AR/VR systems, visual databases, and other tools not only enhance the accessibility of artifact information but also drive audiences from passive recipients to active explorers, even becoming reproducers of cultural narratives. In this context, cultural experience design based on digital means has become an important direction for contemporary museums to reconstruct communication pathways and audience relationships.

Current museum digital experience design faces multifaceted challenges. In practical applications, virtual systems are often added as additional layers onto physical spaces, lacking deep integration with physical exhibition spaces, visitor pathways, and cultural contexts. Furthermore, some museums still center on exhibits or exhibition items, neglecting user-centered interactive behaviors and perceptual psychology, resulting in fragmented and superficial digital cultural experiences. Archaeological site museums often face additional difficulties such as weakened regional cultural identity, difficulty in inspiring emotional resonance among users, and limited spatial development. Digital design often fails to effectively restore spatial context, exhibiting superficial tendencies while ignoring users’ behavioral pathways, psychological changes, and cognitive rhythms, making it difficult to inspire deep cultural experiences and affecting users’ cultural cognition and emotional connection.

In the current digital cultural context, museum experience design urgently needs to integrate more structural and culturally logical narrative approaches beyond technological application, constructing an experience design system with virtual-physical integration as its strategy. This study focuses on archaeological site museums, exploring collaborative pathways between physical and virtual elements in digital cultural experiences.

2.2. Spatial Narrative and Cultural Construction of Museum Physical Experience

Museum space serves as a comprehensive medium for cultural meaning production and emotional experience [

27], not only carrying physical display functions but also requiring narrative logic and cultural symbolism to enable visitors to form deep cultural understanding and emotional resonance during their visits. The introduction of spatial narrative theory provides important theoretical support for extending museum physical experience toward cultural construction functions. Spatial narrative theory originates from the intersection of narratology and spatial theory, emphasizing space as a medium and structural framework for narrative expression [

28,

29]. Through elements such as exhibition layout, environmental atmosphere, and interactive design, story content is embedded into perceivable, walkable spaces [

30]. Narrative is no longer limited to temporal sequence development but forms synergy with spatial layout, making cultural information transmission occur simultaneously in both temporal and spatial dimensions.

The core characteristic of spatial narrative lies in the synchronous integration of temporality and spatiality [

31]. Temporality encompasses both the chronological sequence of historical events and the control of narrative rhythm during visitors’ tours [

6], such as guiding cognitive focus and emotional transformation through rhythmic variation patterns (e.g., fast-slow-fast). Spatiality manifests in the supportive role of physical structure for narrative pathways, including structural attributes such as accessibility, connectivity, and visibility, which directly influence visitors’ behavioral flow and information reception sequence [

32]. Methods such as space syntax are widely used to reveal correlations between spatial structure and visiting behavior, providing methodological basis for narrative pathway optimization [

33].

Existing research systematically categorizes the constituent elements of spatial narrative [

29,

34,

35]. Spatial narrative typically consists of five core elements: people, events, objects, time, and place. “People” refers to the behavioral subjects of narrative experience (such as visitors); “events” refers to the events and plots that constitute the narrative chain (such as historical stories and archaeological processes); “objects” refers to artifacts and digital media that carry information; “time” encompasses historical time sequences and visiting rhythm; and “place” includes exhibition pathways, narrative nodes, and spatial atmosphere among other physical contexts. These elements interact to collectively shape the semantic network and emotional environment of cultural narrative.

Meanwhile, the development of digital technology injects new expressive means into spatial narrative while expanding the expressiveness and narrative depth of spatial information. For example, Dima et al. combined augmented reality with live performance, enabling visitors to obtain extended narrative dimensions and immersive perception within the physical space of archaeological sites [

36]. The physical realm serves as the foundation for providing cultural information and contextual experience and is also a key link connecting the authenticity of historical sites, local cultural contexts, and visitor immersion, making it crucial in the spatial narrative of archaeological site museums.

2.3. Museum Virtual Experience and Serious Games Research

With the maturation of digital media technology, virtual experience has become an important means of museum cultural communication. In virtual experience design, audiences can obtain immersive cultural cognition and spatial perception in non-site environments. This exhibition form that breaks physical boundaries is particularly suitable for reconstructing irreproducible scenes in archaeological site museums, enriching information expression dimensions and enhancing audiences’ sense of presence and cultural understanding. However, as museums rooted in specific geographical and historical contexts, site museums must place greater emphasis on locality and contextual responsiveness in digital cultural experience design [

37,

38,

39]. At present, the development of site museums faces three major challenges:

Weakening of regional cultural identity: As immovable cultural heritage, archaeological sites often struggle to concretize their historical temporality due to static display methods, making it difficult for visitors to develop an authentic perception of historical evolution.

Lack of emotional resonance: Traditional exhibition models focus primarily on the transmission of information while neglecting situational engagement, resulting in limited emotional immersion and empathy among visitors.

Spatial development constraints: Limited physical space, a small number of artifacts, and fragmented exhibition paths hinder visitors from experiencing a coherent spatial narrative.

The core of these issues lies in the absence of a narrative mechanism that achieves deep synchronization and emotional resonance between physical space and virtual experience. Single virtual experiences still have limitations in contextual authenticity, emotional resonance, and cultural depth communication. Recent research increasingly emphasizes the integration of physical elements. For example, Champion proposes the concept of “hybrid narrative environments” [

40], and Rzeszewski proposes “literary place-making” methods [

41]. Serious games can combine virtual technology to construct archaeological scenes, spatiotemporal events, and multiple roles, compensating for the limitations of traditional exhibitions while strengthening audiences’ understanding and memory construction of site cultural connotations.

Therefore, this research introduces the concept of serious games, combining game mechanisms with educational objectives to explore more interactive and participatory digital cultural experience models [

42]. Serious games center on education and cultural dissemination [

43], constructing virtual environments with learning objectives through task-driven approaches, role immersion, and situational construction [

44], not only enhancing audiences’ initiative and participation but also reconstructing the narrative pathways of cultural knowledge [

45]. Virtual experiences in serious games reconstruct archaeological scenes through serious games, guiding audiences through time and space to generate individualized cultural memories, compensating for the limitations of on-site displays. The integration of virtual experience and serious games provides a promising innovative pathway for museum digital cultural communication.

2.4. Research Trends in Virtual-Physical Integration and Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative

With the advancement of digitalization, integrated virtual-physical experience models have become a significant trend in spatial narrative and audience interaction design. This approach not only addresses contemporary audiences’ needs for immersive and diversified experiences but also extends the expressive capacity of cultural narratives across multiple temporal and spatial dimensions.

Traditional research has extensively applied spatial narrative theory to the design of virtual museum experiences. While these studies have made progress in emphasizing the narrative function of physical space and extending virtual experiences based on real-world contexts, they often overlook the alignment between virtual experiences and physical settings [

46]. As a result, issues such as insufficient virtual-physical integration and weak emotional resonance remain prevalent. Fundamentally, this reflects a lack of analysis regarding whether the virtual experience truly meets the needs of the real spatial context. Lefebvre’s triadic theory of spatial production emphasizes the interaction among conceived space, perceived space, and lived space, revealing that space is not only a product of practice but also a synthesis of ideology and social relations [

47]. This theory provides spatial theoretical support for the virtual-physical integrated experience design of archaeological site museums. Therefore, this study adopts the triadic theory of spatial production to interpret how spatial narratives are constructed within digital cultural environments.

However, site spaces carry layered histories and collective memories; their narratives are not merely the reproduction of physical structures but rather the composite expression of temporality, events, and emotions [

48]. Traditional applications of the triadic theory mainly focus on the social construction of space [

49], where temporal information is often implicit, making it difficult to fully address the temporal layering and emotional transmission intrinsic to archaeological sites. In the experiential process of site museums, historical context, virtual content, and real-world experience must be temporally aligned to achieve holistic virtual-physical integration. Accordingly, this study extends the traditional spatial narrative framework by incorporating three temporal dimensions—historical time, virtual time, and real time—corresponding to physical space, virtual space, and hybrid space, as summarized in

Table 1. It further introduces the concept of spatiotemporal overlapping, referring to the interweaving of multiple temporal-spatial threads within the museum environment. Through the collaborative construction of physical and virtual elements, this approach enhances the sense of immersion and establishes a continuous, emotionally resonant experience that bridges virtual narratives and physical spaces.

Although existing studies have proposed various narrative models and frameworks for virtual-physical integrated experiences, such as the Contextual Model of Learning [

50], the Interactive Experiential Model [

51], the VR Exhibition Experience Model [

52], and the Chronotopic Narratives Model [

53], each focusing on aspects such as audience participation, contextual guidance, or immersive experience (

Table 2), these models are primarily suited to traditional museums and digital environments. They fail to effectively address the unique challenges currently faced by archaeological site museums. To this end, the present study develops a Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience (SONE) Model, which aims to resolve issues of temporal asynchrony, narrative discontinuity, and virtual-physical fragmentation in current museum experiences. By synchronizing narrative rhythms across temporal and spatial dimensions, this model strengthens the virtual-physical connection, stimulates cultural identity and emotional resonance, and directly responds to the core challenges in the digital and experiential transformation of site museums.

3. Methodology

3.1. Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience Model

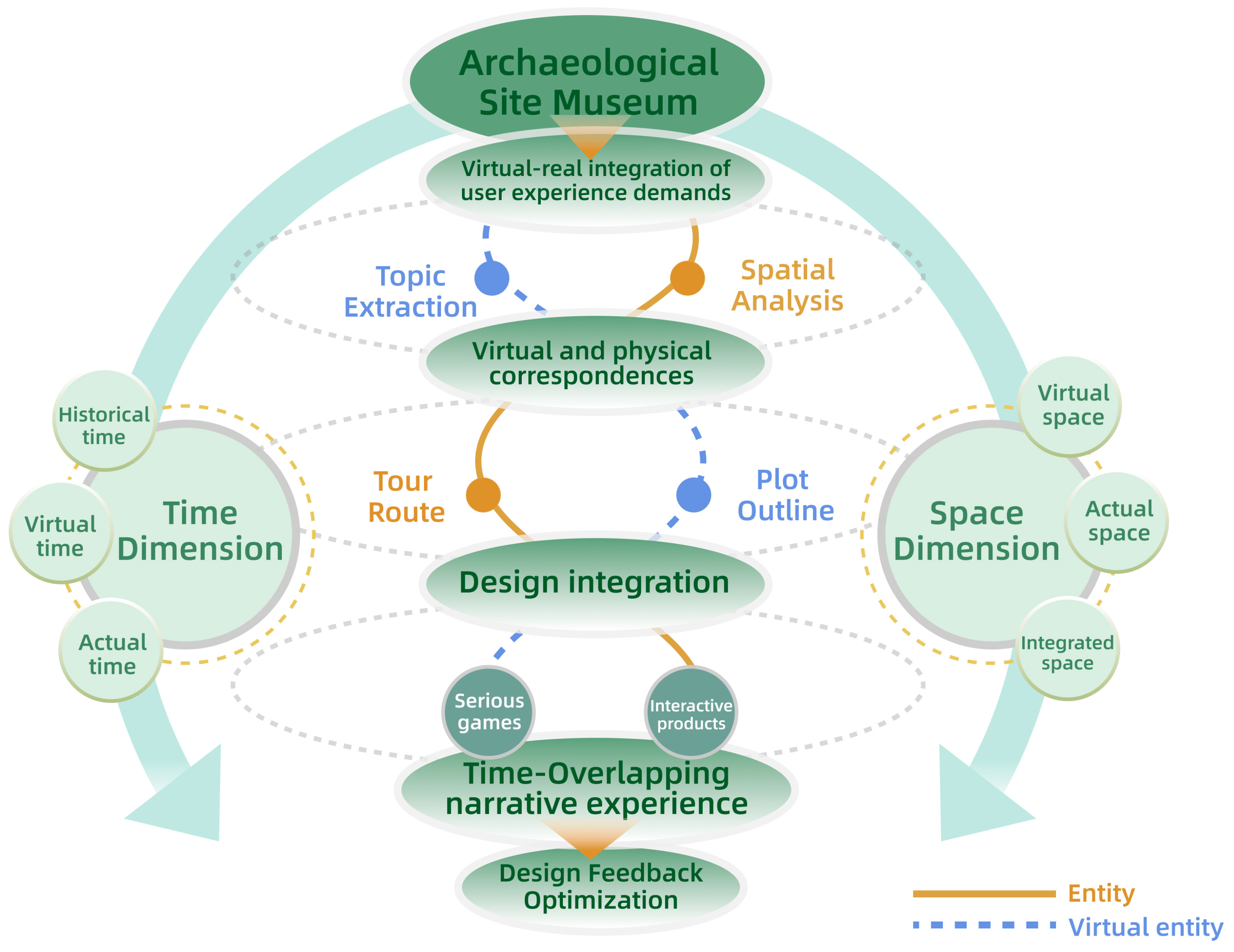

In the context of museum digitalization, scholars have proposed various experience design models to address the dual needs of enhancing audience engagement and promoting cultural dissemination. Compared with other models, although each has its own advantages, they fail to meet the requirements of cross-temporal narrative continuity and deep virtual-physical integration in site museums. Therefore, this paper proposes a Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience Model for site museums (

Figure 1). This model is based on spatial narrative theory, incorporates Lefebvre’s triadic theory of spatial production, and extends its temporal and spatial dimensions to form a narrative experience framework combining three temporal dimensions, three spatial dimensions, and virtual-physical integration. The temporal dimensions include historical time, virtual time, and real time, while the spatial dimensions include physical space, virtual space, and hybrid space. Historical time and physical space carry the authentic reproduction of cultural contexts, forming the foundation of narrative construction; virtual time and virtual space extend historical plots and enhance the expressiveness of information through digital means, providing visitors with immersive exploratory experiences; real time and hybrid space enable the real-time interweaving of virtual and physical realms, where digital content dynamically adjusts according to visitors’ behaviors, locations, and contexts. Through synchronized mapping between physical space and virtual experience, rhythmic alignment and semantic complementarity are achieved in the narrative process. Ultimately, a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience is formed, enhancing the connection between physical and virtual experiences and evoking visitors’ cultural identity and emotional resonance.

Specific research approach: First, experience design should be user-centered [

54], extracting the core needs of museum visitors and transforming them into methods for virtual-physical integrated design. Then, to strengthen the connection between physical space and virtual experience, the virtual and physical components should be analyzed separately before integration. Since the virtual layer is based on the physical one, the physical space is analyzed first to provide the basis for virtual touring routes. Next, the virtual part is analyzed using the three-layer model of culture theory to sort out the cultural characteristics of the site and extract cultural themes and elements. Afterwards, the correspondence between the touring routes and narrative plots is established to realize virtual-physical synchronization, and the design is integrated with visual and game scripts, including serious games and physical interaction practices. Finally, the design practice is evaluated.

3.2. Method Selection

To systematically investigate the virtual-physical integration experience in site museums, this study constructs a combined methodological framework of FAHP1-Space Syntax-FAHP2-FCE based on the theoretical path of the Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Model, forming a closed-loop logic that connects users, space, culture, and experience. The rationale for each methodological choice is as follows:

FAHP (Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process): This study aims to identify user experience needs and narrative cultural themes that influence immersive experiences. Therefore, a weighting method capable of handling subjective judgments and suitable for multi-level hierarchical structures is required. Compared with traditional AHP, Fuzzy Delphi, or Semantic Network Analysis, FAHP demonstrates stronger capabilities in managing uncertainty and fuzziness, making it particularly suitable for calculating relative weights among multi-dimensional indicators [

55]. In this study, FAHP1 is used to extract user experience needs, while FAHP2 is used to identify narrative themes and cultural elements.

Space Syntax: To explore how exhibition space structure affects narrative rhythm, this study introduces space syntax to quantitatively analyze the visual and spatial attributes of physical exhibition halls, providing structural data support for virtual experience design. Compared with qualitative observation or behavioral tracking methods, space syntax is more generalizable and computational, making it applicable to analyzing site museum spaces characterized by both exhibition functions and narrative logic [

56].

FCE (Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation): The evaluation of virtual-physical integrated experiences involves multiple dimensions and hierarchical indicators, requiring a comprehensive evaluation method that can accommodate multi-factor systems. Compared with traditional scoring methods, weighted average methods, or TOPSIS, FCE offers greater flexibility in handling subjective fuzzy data, nonlinear indicator combinations, and normalization across dimensions, making it highly suitable for evaluating complex cultural experience systems [

57].

These three methods are complementary and synergistic, jointly addressing the three critical layers of subjective cognition, spatial structure, and comprehensive fuzzy assessment. This integrated approach ensures systematicness and interpretability of results. Compared with a single-path method such as user surveys or spatial analysis, the combined FAHP-Space Syntax-FCE framework maintains quantitative rigor while integrating multi-source data and expert knowledge, making it particularly effective for narrative-, spatial-, and experience-oriented research in site museum design.

3.3. Data Collection

Data collection combined quantitative and qualitative approaches, encompassing three data sources: user questionnaires, expert ratings, and spatial quantitative analysis.

To assess visitors’ museum experience needs, a quantitative questionnaire grounded in user-perception theory was designed, covering five experience dimensions: perception, cognition, emotion, interaction, and immersion. The questionnaire comprised 50 items. Respondents were recruited via social platforms and museum visitor communities to ensure participants had actual visiting experience and relevant background knowledge. A total of 213 questionnaires were distributed; after removing invalid responses using trap questions, 191 valid questionnaires were recovered. Frequency analysis and indicator consolidation extracted 22 secondary indicators, which served as the basis for constructing the user experience needs analysis system and supporting the FCE evaluation.

The study organized three rounds of expert scoring, corresponding to: user experience needs analysis (FAHP1), cultural element extraction (FAHP2), and virtual-physical integration experience evaluation (FCE). Considering the objectives of each round, experts and target users from diverse but related fields—such as museum spatial design, interaction design, and industrial design—were widely invited to participate. The scoring panel was composed to balance theoretical expertise, practical experience, and the perspective of target users. During scoring, the research team provided standardized scoring instructions, explained the methodology, scoring criteria, and objectives in detail, and conducted feedback clarification and follow-up after each round to enhance data reliability and validity.

Physical spatial data were obtained from the official floor plans of the Panlongcheng Site Museum and existing literature. Standardized floor plans were reconstructed in AutoCAD 2017 (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA), and isovist (visibility) analysis was conducted in DepthmapX 0.6.0 (University College London, London, UK) to calculate the spatial visibility metrics Visual Integration and Visual Clustering Coefficient. Visual Integration was used to identify key narrative nodes, while the Visual Clustering Coefficient was applied to locate zones of emotional immersion, providing a structural basis for virtual-physical content allocation and the design of immersive rhythm.

Method implementation procedure: (1) Summarize questionnaire results and perform weighted analysis of user experience needs using FAHP, then translate core experience needs into virtual-physical integration design requirements. (2) Apply space-syntax isovist analysis to identify key narrative nodes and regions of emotional immersion within the museum exhibition, thereby establishing the basis for narrative routes and spatial layout. (3) Construct a cultural-element evaluation system based on the three-layer model of culture, extract cultural narrative priorities via FAHP, and draft narrative plots corresponding to physical loci. (4) Align spatial structure with narrative plots, integrate user requirements, and develop game scripts to carry out design practice. (5) Introduce expert scoring into a FCE to perform a comprehensive assessment of experiential outcomes.

3.4. Research Subject

The Panlongcheng Site Museum is located in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China and primarily displays archaeological achievements and Shang Dynasty civilization history of the Panlongcheng site. It represents an important early urban center in the Yangtze River basin, witnessing the formation of the north-south bronze civilization dual-core system, carrying multiple values including national governance, cultural exchange, and archaeological research [

58]. The current indoor exhibitions follow the main narrative thread of site excavation processes, artifacts, and historical background, containing three permanent exhibition halls and one temporary exhibition hall that, respectively, present archaeological processes, unearthed artifacts, historical significance, and cultural value. However, constrained by the fact that the museum was not built directly on the core site area, exhibition formats tend toward information transmission, and virtual-physical display integration is insufficient, the existing viewing pathways are generally linear and static, with insufficient immersive and contextual guidance, making it difficult to fully reproduce historical scenes and inspire cultural resonance among visitors.

This study selects the Panlongcheng Site Museum as the case study for the following reasons: the site possesses a well-preserved cultural context and rich archaeological findings, providing a solid historical foundation for site culture. Its static information displays and linear exhibition characteristics align with the study’s focus on museum digitalization and experiential design challenges. The lack of continuity and contextual extension between virtual content and physical narratives presents a typical scenario for applying the proposed model. In addition, the availability of comprehensive baseline data facilitates spatial analysis and experimental validation. Therefore, this case provides an ideal setting for the validation and practical application of the SONE Model.

4. Research Process of Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience at Panlongcheng Site Museum

This study implements the Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience Model in the virtual-physical integrated experience design of the Panlongcheng Site Museum, encompassing seven core stages: (1) Virtual-physical integration transformation guided by user experience needs. (2) Quantitative analysis of physical space. (3) Formulation of narrative themes and plots. (4) Virtual-physical correspondence. (5) Design implementation. (6) Description of the immersive experience of virtual-physical integration. (7) Design validation and evaluation.

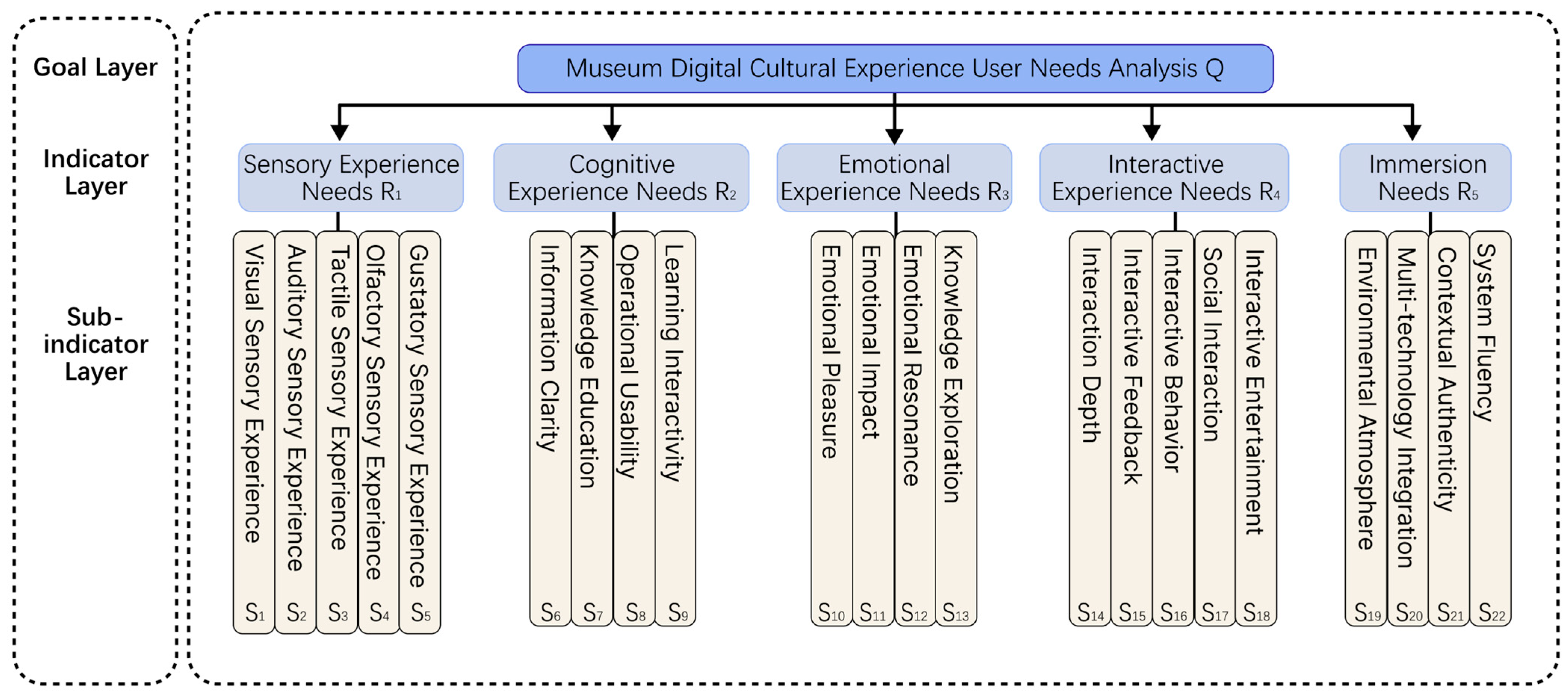

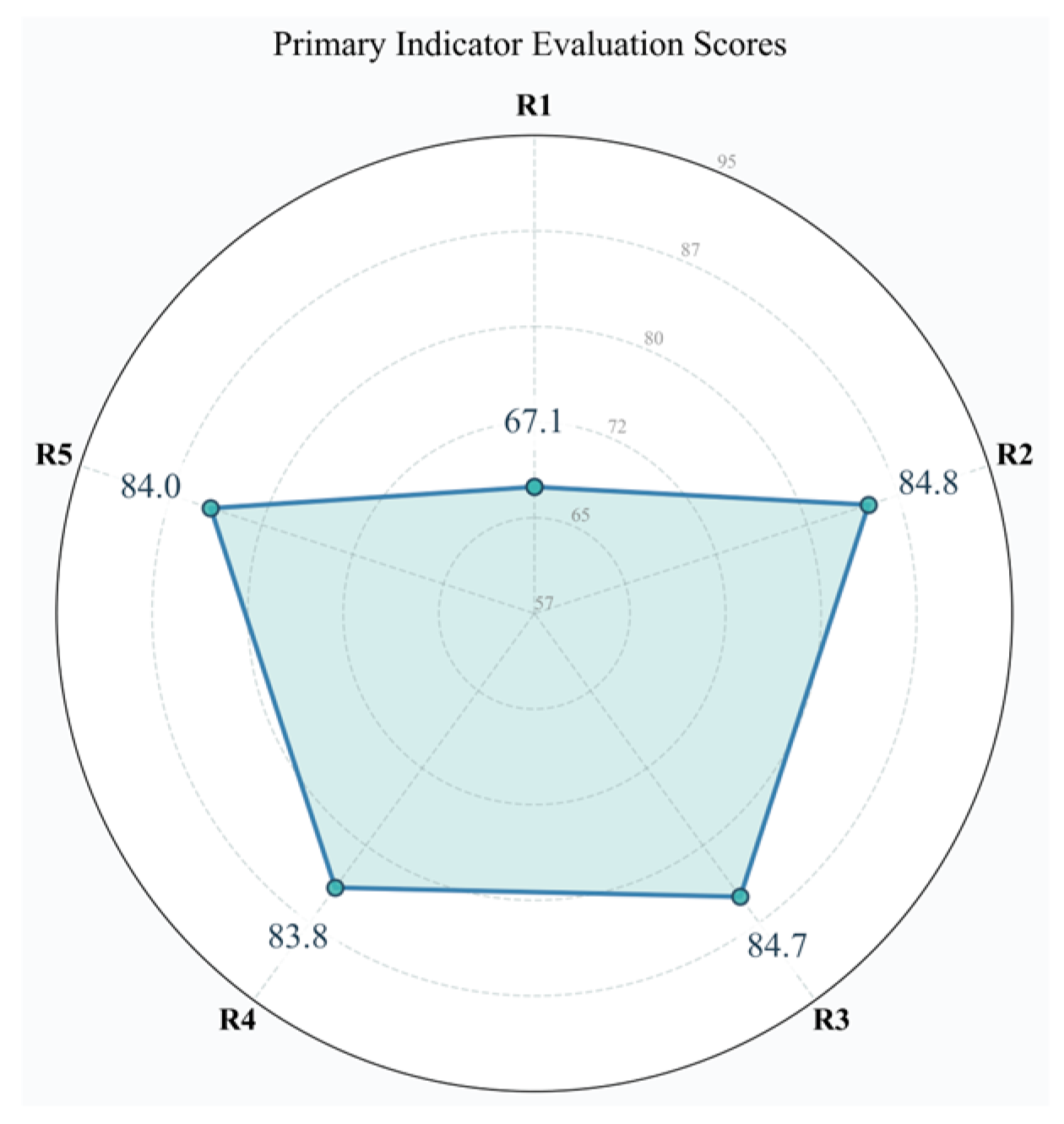

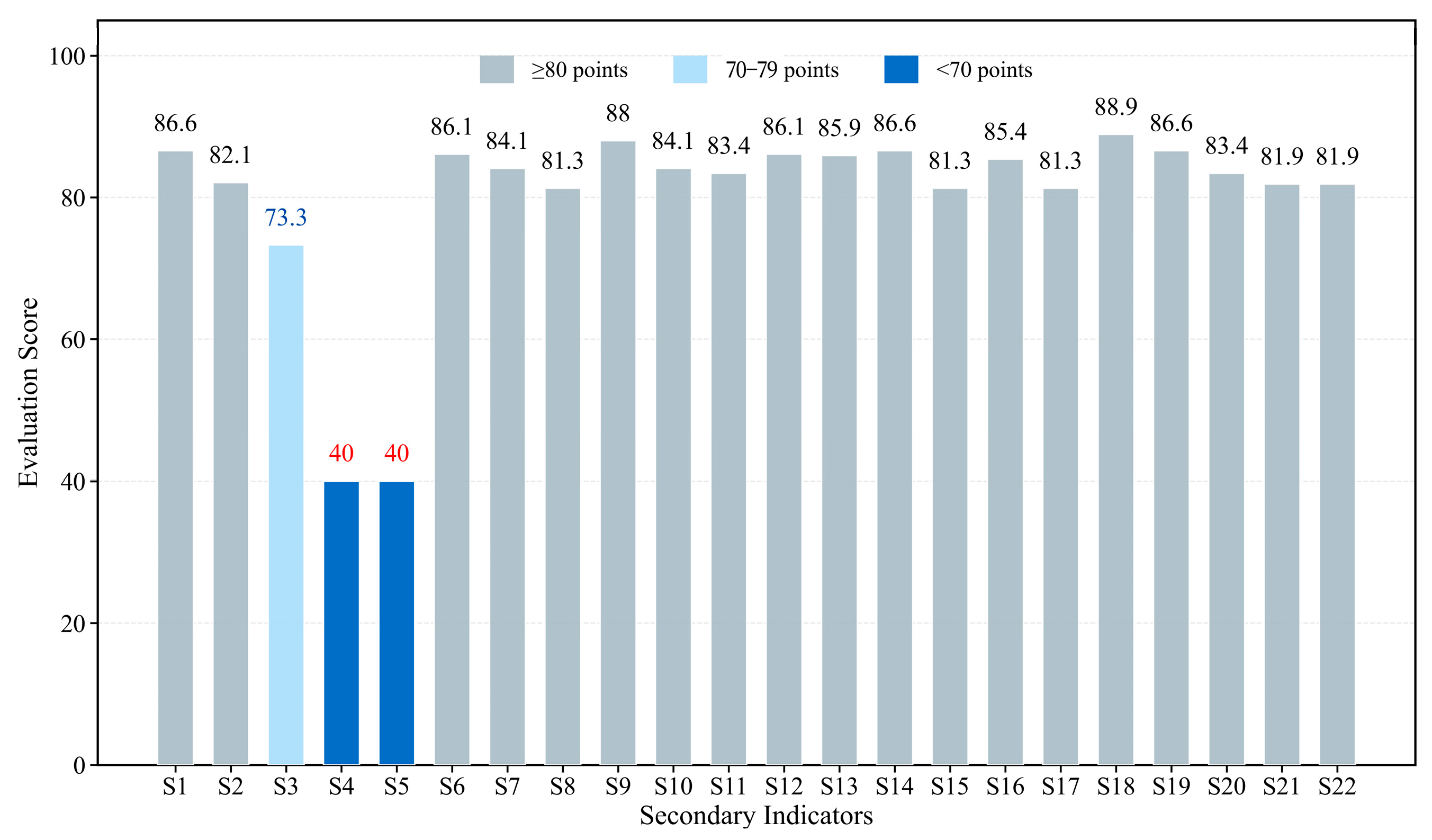

4.1. User Experience Need-Oriented Virtual-Physical Integration Transformation

User experience need analysis is a crucial component in transforming archaeological site cultural content into immersive interactive experiences. To precisely identify core demands of audiences in spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experiences, this paper constructs five primary indicators based on user perception theory (sensory experience, cognitive experience, emotional experience, interactive experience, and immersion). A total of 213 questionnaires were distributed online, and 191 valid responses were obtained after filtering with trap questions. Based on the high-frequency options in the survey results, 22 secondary indicators were extracted to establish the analytical framework of museum user experience requirements (

Figure 2).

To ensure the scientific rigor of weight allocation, an evaluation panel was formed consisting of 4 museum spatial design experts, 6 interaction design graduate students, and 11 visitors. A fuzzy complementary judgment matrix was established using the 0.1–0.9 scale method (

Table 3) and consistency testing was conducted. Based on the museum user experience needs analysis system Q, an evaluation framework is constructed that includes five primary indicator categories: sensory experience needs R

1, cognitive experience needs R

2, emotional experience needs R

3, interactive experience needs R

4, and immersion needs R

5. Analysis using SPSSAU 25.0 (Beijing Qingsi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) shows that learning interactivity, visual sensory experience, and emotional resonance ranked as the top three weights (

Table 4).

The weight vector of the indicator layer is calculated as follows:

The characteristic matrix is calculated as follows:

The compatibility index is calculated as follows:

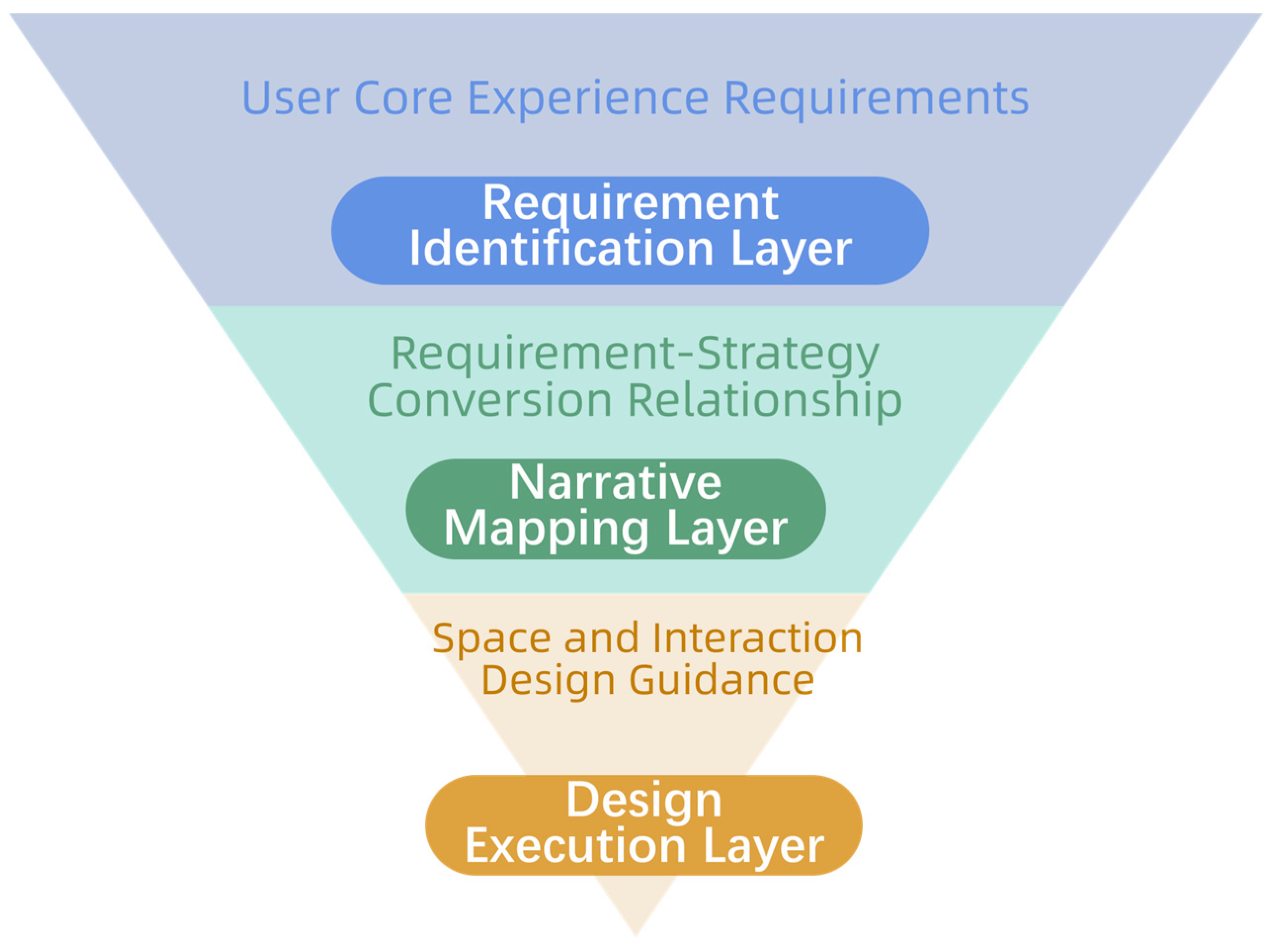

To respond to users’ multiple experience needs in learning interactivity, visual sensory experience, and emotional resonance, based on user-centered design principles and spatial narrative theory, this paper constructs a User Experience Need Virtual-Physical Integration Transformation model (

Figure 3), encompassing a complete pathway from user experience needs to content strategy, then to spatial narrative and virtual-physical integrated experience design. The model consists of three layers: the need identification layer, which identifies key user demands; the narrative mapping layer, which maps needs onto narrative node strategies; and the design execution layer, which specifically guides spatial positioning, virtual interaction, and rhythm design. Based on this model, analysis of user experience need results yields narrative strategies and design methods for archaeological site museums (

Table 5), providing structured support for subsequent virtual-physical integrated design and ensuring high alignment between design and audience needs.

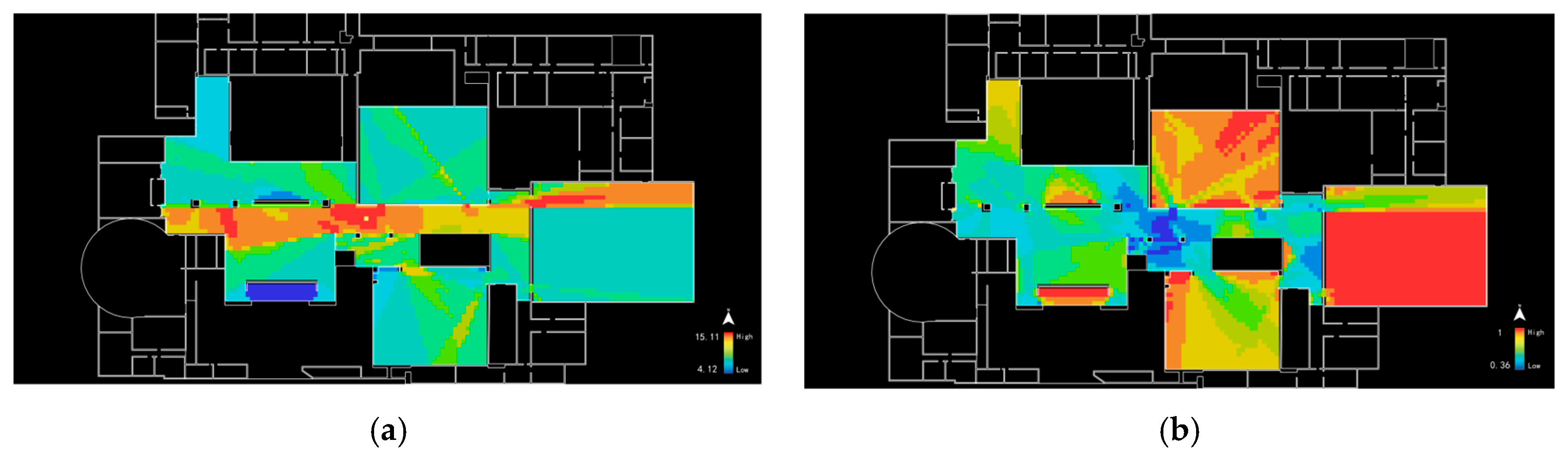

4.2. Quantitative Analysis of Physical Space

Rational spatial organization not only carries artifact exhibitions but also undertakes the task of physical mapping of the narrative rhythm. Particularly in archaeological site museums, spatial structure itself serves as a medium for historical narrative. Based on the analysis results from

Section 4.1 (

Table 5), this section reconstructs functional node configurations in physical space to strengthen the synergistic relationship between spatial structure and narrative content.

To identify key nodes that can support temporal flow and immersive dwelling, this paper employs the visual field analysis method of space syntax to quantitatively model the main exhibition line of the Panlongcheng Site Museum. Space syntax, proposed by Hillier and Hanson, uses graph theory and topological structure to characterize spatial visibility and connectivity, revealing relationships between spatial form and behavioral patterns [

59]. In this study, Depthmap X0.6.0 software is used to conduct visibility analysis of exhibition spaces. Visual integration is used to identify open areas with high visual accessibility suitable for linking multiple narrative segments [

60]. Visual clustering coefficients is used to determine closed spatial nodes suitable for emotional immersion and story transitions [

61].

Results show that the central axis area of the museum has significant integration (

Figure 4a), possessing advantages for guiding linear narrative and suitable as the main axis for linear narrative, achieving comprehensive learning interactivity throughout. The visual clustering coefficients inside exhibition halls are prominent (

Figure 4b), with relatively enclosed spaces suitable for creating immersive atmospheres and emotional resonance fields, achieving emotional resonance. In response to users’ attention to visual sensory experience, dynamic visual media and color enhancement devices are embedded in nodes to create visual impact fields with rhythmic undulations. The overall spatial layout follows four narrative rhythm stages of beginning, development, climax, and ending. Through plot supplementation, eight suitable areas are finally determined to support layered transformation of user experience needs and rhythmic configuration of experience pathways in structural organization and functional distribution.

The overall spatial layout follows the classic four-stage narrative rhythm: introduction, development, climax, and conclusion. To enrich the narrative progression, an additional plot was incorporated into each stage, resulting in a total of eight designated zones. Based on isovist (visibility) analysis, the key loci were connected to form a visitor circulation route (

Figure 5a). Subsequently, the functional roles of each locus within the physical exhibition layout were analyzed (

Figure 5b), providing structural support for the correspondence between virtual and physical narrative plots.

4.3. Narrative Theme and Plot Formulation

Space is not a physical container but a medium carrying cultural information [

62]. This study integrates the Three Levels of Culture Theory to systematically analyze the cultural connotations of the Panlongcheng archaeological site [

63]. From the three dimensions of material culture, institutional culture, and spiritual culture, nine core elements were extracted (

Table 6), forming the evaluation framework of cultural narrative elements for the Panlongcheng site (

Figure 6).

To determine the importance of each element, fuzzy analytic hierarchy process is employed for evaluation. The evaluation panel includes 6 industrial design experts, 5 design graduate students, and 5 target users. The 0.1–0.9 scale method is used to construct judgment matrices, and through consistency testing, effective weight vectors and rankings are obtained. The top three themes from the analysis results (

Table 7) are selected for design integration. Narrative theme construction adopts spiritual belief as the main axis of spatiotemporal overlapping narrative, based on nature worship and spiritual faith, linking ritual behaviors and cultural symbols from different historical periods to strengthen emotional resonance. Ritual institutions form the task-driven part of narrative structure, embedding interactive tasks and knowledge cards through material culture such as bronze ritual vessels and jade systems, responding to learning interactivity needs. Artistic expression serves as a narrative auxiliary line with symbolic aesthetics, maintaining unified stylistic language throughout spatial visuals and virtual media, enhancing the impact and cognitive depth of visual sensory experience.

To strengthen the connection between physical space and virtual experience, the functional roles of the spatial loci identified in the physical space analysis were combined with the extracted spiritual and belief-related narrative themes, and plots were assigned according to the exhibition context of each node. Specifically: Locus 1: Preparation for ritual. Locus 2: Bronze sacrificial ritual. Locus 3: Evolution of royal authority symbolism. Locus 4: Jade ritual. Locus 5: Tortoise-shell divination. Locus 6: Significance of royal power. Locus 7: Speculation on the conclusion of Panlongcheng. Locus 8: Collective development of civilization.

4.4. Virtual-Physical Correspondence

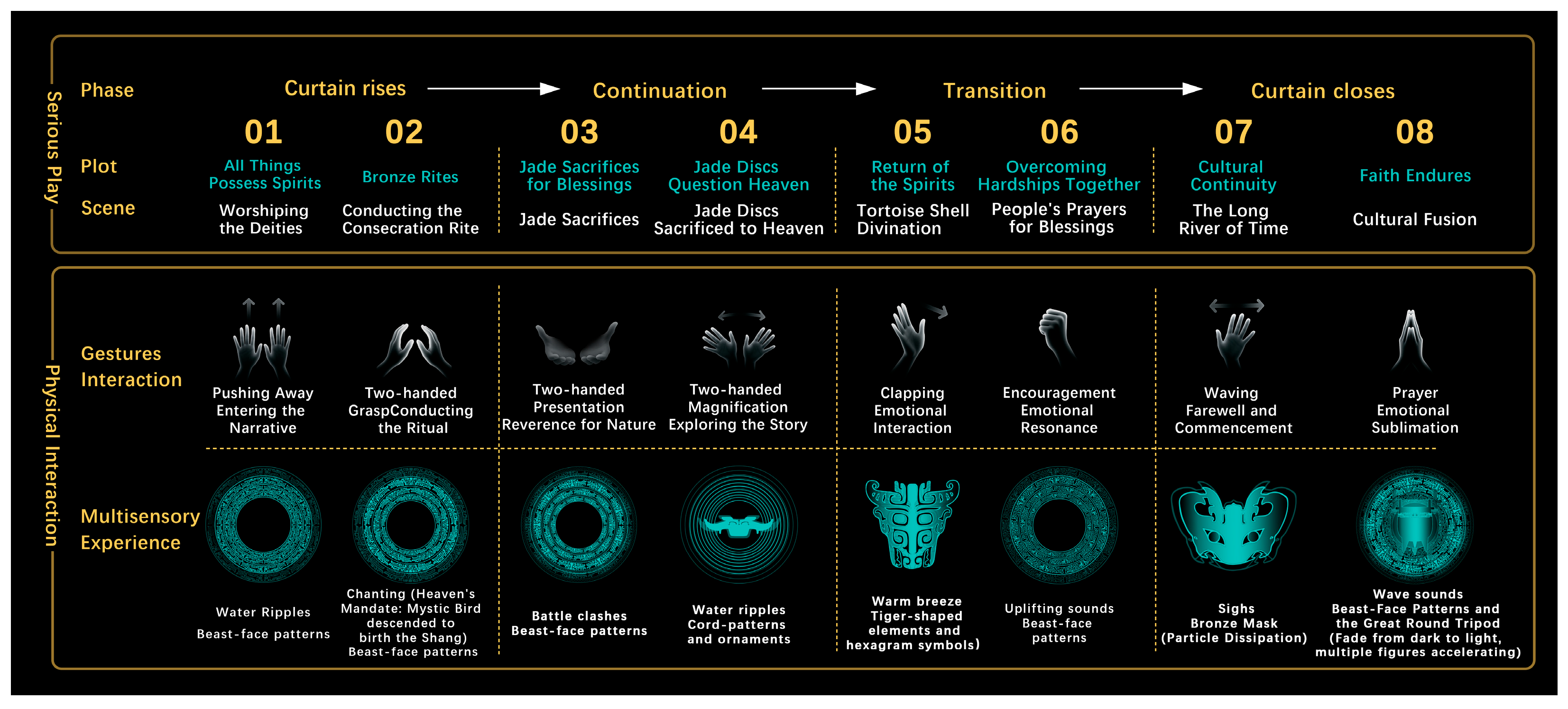

Based on the core user experience needs derived from virtual-physical integration, the sequence of visitation generated by space syntax analysis was matched with the temporal rhythm of cultural events, and an interactive experience script based on serious games was designed as the basis for the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience.

According to the narrative themes and plot formulation of the Panlongcheng Site, a virtual narrative script centered on spiritual beliefs was constructed (

Table 8). The overall game is titled “Nantu Huanghuang” (Splendor of the Southern Land). To enhance immersion, a first-person perspective (as a Shang dynasty ritual practitioner) was adopted to guide users into the scenario and advance the narrative. Introduction stage: Establishes user identity, introduces the motivations of natural worship, triggers the first task, and stimulates emotional connection. Development stage: Recreates ritual procedures according to ceremonial systems, incorporates artifact-driven tasks, and promotes knowledge acquisition and interactive participation. Turning stage: Sudden disasters and divination increase game tension, while multi-branch narratives and ritual behaviors evoke collective emotional resonance. Conclusion stage: Integrates blessing nodes in physical space with virtual feedback outcomes, completing bidirectional mapping and reinforcing the significance of cultural heritage. Within the overall spatiotemporal context: historical time reconstructs the events of Panlongcheng’s evolution; virtual time advances the role-based experience; and the hybrid phase integrates serious games, interactive installations, and physical exhibits, forming a coherent spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience structure.

4.5. Design Implementation

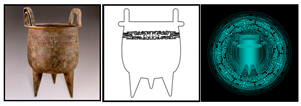

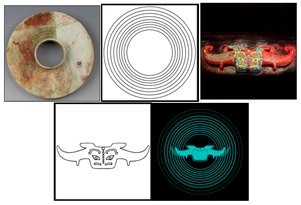

Based on the plot of the game script and the analyzed physical exhibit loci, typical forms, patterns, totem elements, and colors were extracted from key unearthed artifacts such as Panlongcheng bronzes and jade objects to construct the visual system for the virtual-physical integrated experience. The game script, visual system, and core user experience needs were then combined to design the “Nantu Huanghuang” serious game.

In terms of visual design, the symbolic meanings of the artifacts within the Shang dynasty ritual system were analyzed, translating cultural connotations into graphic language and texture patterns, thereby establishing a visual factor library of Panlongcheng’s site culture (

Table 9). For color, the material tones of the excavated artifacts were continued, extracting factors such as verdigris green bronze and golden ornament yellow, forming a color system dominated by warm-cool contrasts. This visual system was applied throughout the experience to ensure stylistic consistency of symbols and colors, providing a unified perceptual context and cultural resonance mechanism for the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience.

By integrating the interactive experience script, visual system, and the virtual-physical transformation of user experience needs, the final game interface was developed (

Figure 7). Through diverse interactions in the serious game—such as task triggers, branching choices, perspective shifts, and knowledge pop-ups—users’ understanding of Panlongcheng’s historical changes and engagement with cultural narrative cues were strengthened, enabling emotional immersion, cultural comprehension, and identity formation, ultimately achieving emotional resonance.

4.6. Description of the Immersive Experience of Virtual–Physical Integration

In the virtual-physical integration practice at the Panlongcheng Site Museum, starting from user experience needs and centered on the “Nantu Huanghuang” theme, the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative method was applied to achieve synchronized design of physical spatial routes and virtual experiences.

The overall virtual-physical integrated experience is constructed through a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative, creating a cross-temporal context that strengthens the connection between physical and virtual elements. Physical locations are synchronized with narrative plots to produce a continuous virtual-physical experience. The implementation of the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative is reflected in two dimensions. In the temporal dimension, historical timelines are constructed through the physical exhibition narrative. The virtual path extends historical time from the perspective of ritual participation, forming virtual time. Hybrid time is realized through task-linked interactions between virtual and physical spaces, with feedback mechanisms that enable the interweaving of temporal layers and drive the narrative rhythm of “Nantu Huanghuang”. In the spatial dimension, the analysis of physical space provides a foundation for virtual-physical integration. Virtual plots and interactive products follow this analysis to construct synchronized paths (

Figure 8). In virtual space, serious games supplement historical information that cannot be displayed by artifacts alone. In the hybrid space, users experience the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative through synchronized virtual-physical interactions, enhancing cultural identity and emotional resonance.

The complete integrated experience process is as follows: In the physical space, interactive products are set at each physical locus as media for synchronized narrative experiences between serious games and physical exhibits. These interactive products are combined with the assigned plots of each locus, through methods such as gesture interaction, dynamic projection, multisensory interaction, and group participation, to enhance engagement and guide users through a continuous narrative experience (

Figure 9). For example, at the “Perpetual Faith” locus, visitors trigger panoramic visual projections and environmental audio through prayer gestures, which are overlaid with mechanisms enabling synchronous multi-user participation, thereby creating emotional resonance. By overlapping multiple temporal and spatial layers within the narrative space, this practice strengthens users’ cultural identity and emotional engagement. As the virtual experience carrier, the serious game guides users through continuous exploration of the physical space, while the unified narrative context formed by the serious game, interactive products, and physical artifacts compensate for the contextual limitations of physical exhibitions, enhancing cultural understanding and emotional resonance. For instance, during the Bronze Ritual experience, users employ gesture interactions to trigger multisensory cultural perception, then complete ritual tasks in the game to gain knowledge and finally return to the physical bronze artifacts to deepen cultural understanding—guiding visitors step by step from perception to comprehension (

Figure 10).

4.7. Design Validation and Evaluation

Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is employed to assess the Nan Tu Huang Huang experience design proposal at Panlongcheng Site Museum, using the previously established user needs analysis system as the evaluation indicator framework for design proposal assessment. Eight interaction design instructors and seven museum design experts were invited to participate in the evaluation. The specific evaluation process is as follows:

Establish the evaluation set for the Nan Tu Huang Huang spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience design and assign values

Obtain evaluation indicator weight vectors. According to previous analysis (

Table 3). The weighting vectors for primary and secondary indicators are as follows:

- 3.

Construct secondary indicator evaluation matrices. Based on scoring by 15 experts, fuzzy comprehensive evaluation matrices for the Nan Tu Huang Huang design proposal are constructed, with results shown in Equations (11)–(15).

Setting the fuzzy evaluation set as

, the fuzzy evaluation sets obtained are

= (0.3073 0.2416 0.1013 0.3499),

= (0.7041 0.2011 0.0791 0.0158),

= (0.6691 0.2331 0.0978 0.0000),

= (0.6786 0.2012 0.0934 0.0268),

= (0.6245 0.2615 0.1140 0.0000). This constructs the secondary evaluation matrix R, with results shown in Equation (16).

Setting the comprehensive evaluation vector for the Nan Tu Huang Huang spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience design proposal as

(0.5917 0.2258 0.0963 0.0862), then the comprehensive evaluation weight vector is calculated; the design practice total score is

80.543, corresponding to a “Good” evaluation level, indicating good performance of this design in digital cultural experience. Through calculation of primary indicator scores and secondary sub-indicator scores (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12), user feedback shows overall satisfaction levels above average, but certain key dimensions still display some disadvantages. Further optimization of experience design should focus on tactile, olfactory, and gustatory sensory experience components.

To obtain subjective user feedback, the study conducted a follow-up survey with participants of the experience, comprising five questions covering narrative continuity (

Table 10), virtual-physical synchronization, cultural identity, emotional resonance, and overall satisfaction. A five-point Likert scale was used, and a total of 18 follow-up questionnaires were collected. The results indicated generally positive user feedback, with high overall satisfaction, further supporting the effectiveness of the design model in practical experience.

5. Discussion

The design practice at the Panlongcheng Site Museum validated the effectiveness of the spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience model in improving virtual–physical integrated experiences in site museums. Centered on virtual–physical synchronization, the model coordinates the rhythms of historical time, virtual time, real time, physical space, virtual space, and hybrid space to achieve spatiotemporal overlapping narrative. This approach strengthens the connection between virtual and physical elements, enhances the contextuality and continuity of narrative experiences, and fosters cultural identity and emotional resonance among visitors.

At the theoretical level, the model is grounded in spatial narrative theory and incorporates Lefebvre’s triad of spatial production, which is adaptively extended to include explicit temporal dimensions, thereby constructing a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience model. Compared with existing studies—such as the Contextual Model of Learning [

50], which focuses on learning paths in physical contexts with limited consideration of virtual media—and unified models of immersive experience [

64], which explore immersion mechanisms in virtual environments but lack structural integration strategies at the spatial narrative level, this model offers a more comprehensive framework. Some studies have attempted to guide narratives through physical space. For instance, Chen et al. [

65] proposed using spatial layouts to guide narrative theme selection and emphasized the mapping between space and theme, yet they did not integrate temporal synchronization mechanisms. In contrast, the current model positions virtual-physical synchronization as its core mechanism, by embedding virtual experiences within physical trajectories and providing a novel theoretical pathway for narrative construction in site-based cultural spaces.

At the methodological level, the FAHP1-space syntax-FAHP2-FCE combination was applied, integrating user experience analysis, spatial structure quantification, cultural theme identification, and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation feedback. This approach addresses the interrelated elements of users, space, culture, and experience, achieving enhanced virtual-physical narrative integration. The combination forms a closed-loop path from needs analysis to design and feedback. Unlike Dai et al. [

66], who focused on spatial structure and individual physiological responses in art exhibition spaces, this study extends spatial analysis to the cultural narrative dimension. Compared with Hu Yukun et al. [

67], who primarily applied FAHP to extract traditional cultural design elements from artifact images, the current method achieves integration across space, narrative, and culture.

At the application level, unlike traditional static exhibition modes, the design practice combines serious games, interactive products, and physical exhibits to realize dynamic cultural narrative generation, spatial path organization, and user experience feedback. This allows for the dynamic unfolding of spatiotemporal overlapping narratives within limited physical spaces. The model’s framework and methodological approach provide a reference for narrative, experiential, and digital transformation of site museums.

6. Model Limitations and Research Prospects

The spatiotemporal overlapping narrative model has achieved positive results in practice, but several limitations remain and should be addressed in future research:

Sample limitation: This study validated the design method using the Panlongcheng Site Museum as a case. While effective in this context, the single-case nature limits generalizability. Future research should select diverse types of cultural heritage museums to examine the model’s stability and applicability across different contexts.

Spatial type limitation: The current case primarily involves linear exhibition layouts. For open or nonlinear exhibition spaces, further validation by other research teams is needed. Future studies should include a variety of spatial configurations to explore the adaptation boundaries of the model.

Cultural adaptability: This study focuses on a Chinese cultural context. The model’s universality across different cultural backgrounds remains untested. Variations in how different cultures interpret historical narratives and interactive experiences may affect applicability. Cross-cultural comparative studies are recommended to enhance the model’s international adaptability.

Technical and environmental interference: Virtual-physical integrated experiences rely heavily on equipment performance and environmental conditions. Factors such as the processing capability of mobile devices, positioning accuracy, museum lighting, and ambient noise may affect the synchronization of virtual-physical narratives and the emotional resonance of the experience.

7. Conclusions

This study proposes a spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience model aimed at enhancing cultural identity and emotional resonance in site museums and applies it to the design practice of the Panlongcheng Site Museum. Grounded in spatial narrative theory and incorporating Lefebvre’s triad of spatial production, the model is further extended along temporal and spatial dimensions to construct a framework for spatiotemporal overlapping narrative experience. The design practice demonstrates that this model strengthens the connection between physical space and virtual experience, creating a hybrid, cross-temporal narrative environment through the synchronization of physical and virtual storytelling, thereby enhancing users’ cultural identity and emotional resonance.

Methodologically, the study employs a combination of FAHP, space syntax, and FCE, starting from user needs, informing design through physical space analysis, constructing virtual narratives based on cultural themes and elements, and concluding with virtual-physical integration and evaluation feedback. Compared to traditional single-method approaches, this combination systematically integrates users, space, culture, and experience. In practice at the Panlongcheng Site Museum, serious games and interactive physical products guide users through multisensory interactions, facilitating cross-temporal cultural perception. Results indicate that the proposed model effectively enhances narrative continuity, visitor immersion, and cultural engagement, providing valuable insights for designing virtual-physical integrated experiences in site museums.

However, this study has certain limitations. Validation was conducted solely at the Panlongcheng Site Museum. Future research should include different types, scales, and cultural themes of site museums to further test the model’s applicability. The case study focuses on a linear exhibition, while validation in open or nonlinear exhibition spaces is still required. Additionally, dynamic environmental and equipment factors may affect user experiences. To address these limitations, future studies could employ cross-cultural case comparisons, physiological feedback analyses, and multidimensional immersion evaluation methods to further refine the model’s applicability and rigor. Overall, the study provides new theoretical support and practical insights for the digital and experiential transformation of site museums.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and Q.H.; methodology, Q.H., X.H. and T.W.; software, X.H.; validation, X.H. and Q.H.; formal analysis, X.H. and Q.H.; investigation, X.H. and Y.Y.; resources, Q.H.; data curation, X.H. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.H. and X.H.; writing—review and editing, Q.H.; visualization, X.H. and T.W.; supervision, Q.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Doctoral Research Startup Fund of Hubei University of Technology (BSQD2020071).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The human study protocol was approved by the Human Study Ethics Committee of Hubei University of Technology (protocol code: HBUT20250028, approved date: 31 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within this article. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SONE | Spatiotemporal Overlapping Narrative Experience |

| FAHP | Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| FCE | Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Sun, X.; Ch’ng, E. Evaluating the management of ethnic minority heritage and the use of digital technologies for learning. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Lucia, M.D.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Innovating the cultural heritage museum service model through virtual reality and augmented reality: The effects on the overall visitor experience and satisfaction. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council of Museums. ICOM Announces a New Museum Definition. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Nikolakopoulou, V.; Printezis, P.; Maniatis, V.; Kontizas, D.; Vosinakis, S.; Chatzigrigoriou, P.; Koutsabasis, P. Conveying Intangible Cultural Heritage in Museums with Interactive Storytelling and Projection Mapping: The Case of the Mastic Villages. Heritage 2022, 5, 1024–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, C.; Pittarello, F. Svevo tour: The design and the experimentation of an augmented reality application for engaging visitors of a literary museum. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2018, 114, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvic, S.; Boskovic, D.; Mijatovic, B. Advanced interactive digital storytelling in digital heritage applications. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 33, e00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulopoulos, V.; Wallace, M. Digital Technologies and the Role of Data in Cultural Heritage: The Past, the Present, and the Future. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liritzis, I.; Al-Otaibi, F.; Volonakis, P. Digital technologies and trends in cultural heritage. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2015, 15, 313. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, L.; Champion, E. Evaluating presence in cultural heritage projects. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, L. The poetics of augmented space. Vis. Commun. 2006, 5, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A.; Liu, Y.; Loo, P.T. Transforming museums with technology and digital innovations: A scoping review of research literature. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furferi, R.; Di Angelo, L.; Bertini, M.; Mazzanti, P.; De Vecchis, K.; Biffi, M. Enhancing traditional museum fruition: Current state and emerging tendencies. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, R.G.; Băutu, E.; Gîrbacia, F.; Popovici, N.; Popovici, D.-M. Augmented reality in cultural heritage: An overview of the last decade of applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, S.; Cesta, A.; Cortellessa, G.; De Benedictis, R.; Fracasso, F.; Leopardi, L.; Ligios, L.; Lombardi, E.; Malatesta, S.G.; Oddi, A. Evaluating visitors’ experience in museum: Comparing artificial intelligence and multi-partitioned analysis. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 33, e00340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, C.; Yilmazer, S. Harmony of context and the built environment: Soundscapes in museum environments via GT. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 173, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; Rizzi, A. Reality-based 3D documentation of natural and cultural heritage sites—Techniques, problems, and examples. Appl. Geomat. 2010, 2, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaz, X.; Garcia, R.; Ortiz, A.; Marichal, S.; Villadangos, J.; Ardaiz, O.; Marzo, A. An interdisciplinary design of an interactive cultural heritage visit for in-situ, mixed reality and affective experiences. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Mania, K.; Karoulis, A.; White, M. Exploring the relationship between presence and enjoyment in a virtual museum. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2010, 68, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroni, E. Experience design, virtual reality and media hybridization for the digital communication inside museums. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, W.; Baloian, N.; Biella, D.; Sacher, D. Digital twins and enabling technologies in museums and cultural heritage: An overview. Sensors 2023, 23, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.H.; Kim, H.S. User experience research, experience design, and evaluation methods for museum mixed reality experience. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2021, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hale, J.; Hanks, L. Archive or exhibition?: A comparative case study of the real and virtual Pitt Rivers Museum. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 32, e00305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Li, K.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Y. An empirical study of virtual museum based on dual-mode mixed visualization: The Sanxingdui bronzes. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroni, E. Multisensory Museums, Hybrid Realities, Narration, and Technological Innovation: A Discussion Around New Perspectives in Experience Design and Sense of Authenticity. Heritage 2025, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. Recoding the Museum: Digital Heritage and the Technologies of Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, T. Narrative Environments and Experience Design: Space as a Medium of Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Puxan-Oliva, M. Assessing Narrative Space: From Setting to Narrative Environments. Poet. Today 2024, 45, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaryahu, M.; Foote, K.E. Historical space as narrative medium: On the configuration of spatial narratives of time at historical sites. GeoJournal 2008, 73, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lan, L. Museum as multisensorial site: Story co-making and the affective interrelationship between museum visitors, heritage space, and digital storytelling. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2021, 36, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Spatial narrative in fiction:“Spatialization” of fiction narrative. In Spatial Literary Studies in China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Tzortzi, K. Space syntax: The language of museum space. In A Companion to Museum Studies; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 282–301. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, L. From functional space to experience space: Applying space syntax analysis to a museum in China. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaan, R.A. Situation models, mental simulations, and abstract concepts in discourse comprehension. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2016, 23, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, B. Narratives of space, time, and life. Mind Lang. 2004, 19, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, M.; Daylamani-Zad, D.; Lympouridis, V. Mixed reality heritage performance as a decolonising tool for heritage sites. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.07348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, K. High tech or high touch? Heritage encounters and the power of presence. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liao, J.; Xiao, H. How do tourists’ heritage spatial perceptions affect place identity? A case study of Quanzhou, China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, D.; Meng, Y.; Deng, C.; Li, Q.; Chaudhary, S. Digitalizing cultural heritage through metaverse applications: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E. Mixed histories, augmented pasts. In Playing with the Past: Into the Future; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rzeszewski, M.; Naji, J. Literary placemaking and narrative immersion in extended reality virtual geographic environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Hu, C. Application Model of Museum Cultural Heritage Educational Game Based on Embodied Cognition and Immerse Experience. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaCosta, B.; Kinsell, C. Serious games in cultural heritage: A review of practices and considerations in the design of location-based games. Educ. Sci. 2022, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, N. A mixed-methods study of cultural heritage learning through playing a serious game. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-Y.; Park, J.; Engberg, M.; MacIntyre, B.; Bolter, J.D. RealityMedia: Immersive technology and narrative space. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1155700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. From the production of space. In Theatre and Performance Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.P.; Carter, P.L.; Potter, A.E.; Bright, C.F.; Alderman, D.A.; Modlin, E.A.; Butler, D.L. Following the story: Narrative mapping as a mobile method for tracking and interrogating spatial narratives. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lanen, S.; Meij, E. Producing space through social work: Lefebvre’s social production of space and the history of social work in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Jo, Y.; Kang, Y.; Lee, H.-K. Interactive experiential model: Insights from shadowing students’ exhibitory footprints. J. Mus. Educ. 2023, 48, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Suh, J. The Impact of VR Exhibition Experiences on Presence, Interaction, Immersion, and Satisfaction: Focusing on the Experience Economy Theory (4Es). Systems 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Jia, C.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. Identifying key factors influencing immersive experiences in virtual reality enhanced museums. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmidt, E.; Kacprzyk, J. A consensus-reaching process under intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2003, 18, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Xian, Z.; Takeda, S.; Zhang, J.; Xing, S. Interpreting the space characteristics of everyday heritage gardens of Suzhou, China, through a space syntax approach. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 3471–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zheng, X.; Heath, T. Research on the Design of Community Museums Based on the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. The Role of Panlongcheng in the Process of Chinese Civilization. Jianghan Archaeol. 2025, 1, 95–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bill, H.; Julienne, H. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Y.; Abd Malek, M.I.; Jaafar, N.H.; Sima, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Z. Unveiling the potential of space syntax approach for revitalizing historic urban areas: A case study of Yushan Historic District, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacar, Ö.Ö.; Gülgen, F.; Bilgi, S. Evaluation of the Space Syntax Measures Affecting Pedestrian Density through Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, P.M. Toward an anthropological understanding of space and place. In Place, Space and Hermeneutics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. A Scientific Theory of Culture and Other Essays: [1944]; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Makransky, G.; Petersen, G.B. The cognitive affective model of immersive learning (CAMIL): A theoretical research-based model of learning in immersive virtual reality. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, T.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X. VirtuNarrator: Crafting museum narratives via spatial layout in creating customized virtual museums. Vis. Inform. 2025, 9, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, M. Evaluating Art Exhibition Spaces Through Space Syntax and Multimodal Physiological Data. Buildings 2025, 15, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, S.; Qin, S.; Chen, D.; Chu, J.; Yang, Y. How to extract traditional cultural design elements from a set of images of cultural relics based on F-AHP and entropy. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 5833–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Spatiotemporal overlapping narrative model.

Figure 1.

Spatiotemporal overlapping narrative model.

Figure 2.

Museum user experience requirements analysis framework.

Figure 2.

Museum user experience requirements analysis framework.

Figure 3.

Virtual-physical integration model for user experience requirements transformation.

Figure 3.

Virtual-physical integration model for user experience requirements transformation.

Figure 4.

(a) Visual integration analysis; (b) visual clustering coefficient analysis.

Figure 4.

(a) Visual integration analysis; (b) visual clustering coefficient analysis.

Figure 5.

(a) Physical tour route; (b) entity site function.

Figure 5.

(a) Physical tour route; (b) entity site function.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of cultural narrative elements at the Panlongcheng site.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of cultural narrative elements at the Panlongcheng site.

Figure 7.

Partial interface display of some serious games.

Figure 7.

Partial interface display of some serious games.

Figure 8.

Virtual-physical synchronization path.

Figure 8.

Virtual-physical synchronization path.

Figure 9.

Product interaction experience.

Figure 9.

Product interaction experience.

Figure 10.

Virtual-physical hybrid interaction.

Figure 10.

Virtual-physical hybrid interaction.

Figure 11.

Scores of primary indicators.

Figure 11.

Scores of primary indicators.

Figure 12.

Secondary indicators.

Figure 12.

Secondary indicators.

Table 1.

Spatiotemporal dimensional extension of the triadic theory of space production.

Table 1.

Spatiotemporal dimensional extension of the triadic theory of space production.

| Triadic Theory of Space Production | Temporal Dimension | Spatial Dimension | Primary Experience Characteristics |

|---|

| Perceived Space | Historical Time | Physical Space | Primary Experience Characteristics |

| Conceived Space | Virtual Time | Virtual Space | Spatiotemporal exploration beyond reality |

| Conceived Space | Real Time | Hybrid Space | Emotional resonance and meaning generation |

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of virtual-physical narrative models.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of virtual-physical narrative models.

| Model Name | Core Mechanism | Applicable Context | Limitations |

|---|

| Contextual Model of Learning | Contextualized learning cycle | Educational museums | Neglects spatial structure and multidimensional temporal narratives |

| Interactive Experiential Model | Audience interaction and feedback loop mechanism | VR exhibitions, digital museums | Emphasizes interactivity but lacks control over narrative rhythm |

| VR Exhibition Experience Model | Immersive VR spatial narrative | VR exhibitions, online exhibitions | Difficult to integrate with the structure of physical spaces |

| Chronotopic Narratives ModelR Exhibition Experience Model | Narrative construction and virtual reconstruction of historical spatiotemporal scenes | Digital heritage, virtual historical reconstruction | Lacks a synchronization mechanism between virtual and physical spaces; fails to establish a closed loop integrating user needs, spatial context, and cultural expression |

Table 3.

A 0.1–0.9 scale method and its meanings.

Table 3.

A 0.1–0.9 scale method and its meanings.

| Scale | Definition | Explanation |

|---|

| 0.5 | equally important | When comparing two factors, they are equally important |

| 0.6 | slightly important | When comparing two factors, the row factor is slightly more important than the column factor |

| 0.7 | obviously important | When comparing two factors, the row factor is obviously more important than the column factor |

| 0.8 | much more important | When comparing two factors, the row factor is much more important than the column factor |

| 0.9 | extremely important | When comparing two factors, the row factor is extremely more important than the column factor |

| 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 | inverse comparison | If factor ri compared to factor rj receives judgment rij, then factor rj compared to factor ri receives judgment |

Table 4.

Weight ranking of museum user experience needs analysis.

Table 4.

Weight ranking of museum user experience needs analysis.

| Indicator Layer | Primary Weight | Sub-Indicator Layer | Secondary Weight | Comprehensive Weight | Weight Ranking |

|---|

| Sensory Experience Needs R1 | 0.22000 | Visual Sensory Experience S1 | 0.24500 | 0.05390 | 2 |

| Auditory Sensory Experience S2 | 0.20500 | 0.04510 | 9 |

| Tactile Sensory Experience S3 | 0.21500 | 0.04730 | 7 |

| Olfactory Sensory Experience S4 | 0.16500 | 0.03630 | 18 |

| Gustatory Sensory Experience S5 | 0.17000 | 0.03740 | 17 |

| Cognitive Experience Needs R2 | 0.20500 | Information Clarity S6 | 0.25000 | 0.05125 | 5 |

| Knowledge Education S7 | 0.25000 | 0.05125 | 5 |

| Operational Usability S8 | 0.22500 | 0.04613 | 8 |

| Learning Interactivity S9 | 0.27500 | 0.05638 | 1 |

| Emotional Experience Needs R3 | 0.19000 | Emotional Pleasure S10 | 0.25833 | 0.04908 | 6 |

| Emotional Impact S11 | 0.20833 | 0.03958 | 15 |

| Emotional Resonance S12 | 0.27500 | 0.05225 | 3 |

| Knowledge Exploration S13 | 0.25833 | 0.04908 | 6 |

| Interactive Experience Needs R4 | 0.22500 | Interaction Depth S14 | 0.18000 | 0.04050 | 14 |

| Interactive Feedback S15 | 0.19000 | 0.04275 | 12 |

| Interactive Behavior S16 | 0.20500 | 0.04613 | 9 |

| Social Interaction S17 | 0.19500 | 0.04388 | 11 |

| Interactive Entertainment S18 | 0.23000 | 0.05175 | 4 |

| Immersion Needs R5 | 0.16000 | Environmental Atmosphere S19 | 0.27500 | 0.04400 | 10 |

| Multi-technology Integration S20 | 0.24167 | 0.03867 | 16 |

| Contextual Authenticity S21 | 0.25833 | 0.04133 | 13 |

| System Fluency S22 | 0.21667 | 0.03467 | 19 |

Table 5.

Virtual-physical integration transformation of user experience needs.

Table 5.

Virtual-physical integration transformation of user experience needs.

| User Experience Needs | Narrative Mapping Strategy | Spatial and Interactive Design Methods |

|---|

| Learning Interactivity | Virtual-Physical Task Design | Virtual: Task-driven, knowledge card pop-ups

Physical: Artifact information points, trigger devices

Integration: Task completion triggers physical space verification or achievements |

| Visual Sensory Experience | Spatial Node Integration | Virtual: Dynamic narrative scene rendering, lighting, sound effects

Physical: Visual integration with high focal enhancement display, unified color scheme

Integration: Unified visual style across virtual and physical realms |

| Emotional Resonance | Collective Emotional Resonance | Virtual: Character empathy, ritual interactive storylines

Physical: Immersive node arrangement

Integration: Multi-person collaborative interaction |

Table 6.

Cultural hierarchical classification of Panlongcheng site.

Table 6.

Cultural hierarchical classification of Panlongcheng site.

| Cultural Level | Type | Corresponding Content | Specific Elements |

|---|

| Material Culture | Settlement Remains | Wangjiazui | Secondary core area where early nobles or craftsmen gathered |

| Lijiazui | Noble burial area during the flourishing period |

| Yangjiawan | Latest period high-ranking noble burial area of Panlongcheng |

| Palace Architecture | Palace Foundation Sites 1, 2, and 3 of Panlongcheng | Site 1: Four-bay rear chamber building; Site 2: Hall-style front court building; Site 3: Forms front court-rear chamber pattern with Sites 1 and 2 |

| Civilian Architecture | Stilt-style wooden frame houses | Building style and techniques adapted to climate by Panlongcheng ancestors |

| Post-hole construction | A process in building construction |

| Urban Production | Bronze artifacts

Jade objects

Pottery

Stone tools | Wine vessels, food vessels, weapons, miscellaneous items