Abstract

The influence of traditional Chinese ritual culture on courtyard spatial sequences is widely acknowledged. However, quantitative analytical methods, such as space syntax, have rarely been applied in studies of ritual–residential space relations. This study uses space syntax, specifically Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) and axial maps, to conduct a quantitative study of the spatial relationship between ritual and residential areas in Prince Kung’s Mansion. The VGA results indicate a distinct gradient of visual integration, which decreases progressively from the outward-oriented ritual areas, such as the palace gate and halls, through the transitional domestic ritual areas to the inward-oriented residential areas, such as Xijin Zhai and Ledao Tang. This pattern demonstrates a positive correlation between spatial visibility and ritual hierarchy. The axial map results confirm that the central axis and core ritual spaces exhibit the highest spatial connectivity, reflecting their supreme ritual status. More importantly, spatial connectivity is intensified during ritual activities compared to in daily life, indicating that enhanced spatial connectivity is required during rituals. Ritual spaces are characterized by extroversion, high visibility, and connectivity, while residential spaces prioritize introversion and minimal exposure. The deliberately designed ritual–residential architectural spatial sequence of Prince Kung’s Mansion articulates Confucian ideological principles, such as centrality as orthodoxy, gender segregation, and hierarchy. This study visually and quantitatively illustrates the harmony between ritual and residential spaces in Prince Kung’s Mansion. It enhances our understanding of the mechanisms of expression of courtyard ritual cultural spaces, providing evidence-based guidance for functional adaptive transformations in heritage conservation practices. It also offers a fresh perspective on the analysis of courtyard ritual spaces.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Influence of Ritual Culture on Traditional Chinese Courtyards

Ritual has been an integral part of Chinese traditional culture for millennia, playing a significant role in shaping the layout of ancient residential courtyards. As stated in Book of Rites: Records of Music, rituals are the order of heaven and earth [1].

The traditional courtyard, influenced by ancient ritual systems and architectural regulations, follows a specific ritual layout that embodies Confucian ideological principles, such as centrality as orthodoxy, prioritization of the eastern orientation, gender segregation, and hierarchy. In this context, the courtyard of Prince Kung’s Mansion was laid out to integrate ritual propriety with daily life, becoming a paradigm of traditional courtyards influenced by ritual culture.

Scholars have conducted multi-dimensional and in-depth explorations of the interplay between ritual culture and courtyard architecture. These studies can be broadly categorized into the following three types.

- (1)

- Research on ancient architectural rules and regulations

These studies explore how ritual systems and architectural regulations shape the form, scale, and layout of courtyards.

Fu Xinian summarized ancient Chinese architectural engineering management and hierarchical systems (2012) [2]. Liu Yuting compiled architectural regulations and institutions across successive Chinese dynasties (2010) [3]. These works have become essential reference works in the study of ancient Chinese architectural systems.

Hou Youbin, within his theoretical system, proposed the dual theory of “Order of Rites” and “Order of Harmony”, explaining how these factors jointly shaped the esthetic principles and spatial conception of traditional courtyard layouts (1997) [4]. Wu Hong, through interdisciplinary research, explained that the spatial layout of ancestral temples and palaces is a core of power and ritual, defining the construction logic of “ritual preceding residence” (2009) [5].

- (2)

- Research on spatial paradigms of traditional courtyards

These studies concentrate on extracting the ritual spatial layout of traditional courtyards and elucidating the underlying ritual culture.

Based on classical texts from the Han Dynasties, Liu Dunzhen clearly delineated public and private functions with “external areas for administrative affairs, internal areas for living quarters”, thus establishing the basic paradigm for later courtyards (1980) [6]. Ruitenbeek, adopting a cross-cultural perspective, argued that the square and regular forms of Chinese housing are the material manifestation of a cosmological view and ritual pursuit of order and harmony (1996) [7]. Wang Lumin specifically analyzed how, constrained by architectural codes, the forms of princely and official Ming Dynasty residences evolved from corridor style to courtyard style and their underlying hierarchical symbolism (2012) [8]. Li Yunhe formalized a ritual-centric analytical framework and pioneered the Gate–Hall Separation theory (2005) [9]. Wang Lumin conducted a classification study on the characteristics of traditional Chinese courtyard layouts featuring central-axis symmetry, in which the ritual characteristics embodied in ancient courtyards were analyzed (2012) [10]. Zhu Gejing investigates the time of emergence and layout evolution of the concepts of public and family halls in ancient China, highlighting courtyard layout development during the Song Dynasty (2016) [11].

- (3)

- Research on ritual activities in ancient courtyard spaces

These studies analyze the characteristics of ritual spatial patterns by examining the processes of ancient ritual activities conducted within the courtyard.

Zhao Xiaofeng et al. examined the “Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial·Capping Ceremony for Officers” in combination with archeological sites, reconstructing how ritual processes unfolded in spaces such as halls and courtyards and summarizing the scale and ritual circulation characteristics of Western Zhou ancestral temple architecture (2021) [12]. Based on records of orientation and procedure for capping and wedding ceremonies in the “Kaiyuan Rites of the Tang Dynasty”, Wang Hui et al. reverse-engineered the possible layout of the “main hall” in Tang Dynasty official residences (2020) [13].

1.2. Space Syntax in Architectural Heritage Studies

Space syntax, proposed in the late 1970s by Bill Hillier and his team, emerged from explorations into the social logics of urban and architectural spaces [14]. Space syntax has a well-established theoretical framework, a mature research methodology, and dedicated analysis software. Space syntax effectively reveals topological relationships, accessibility, visual perception, and clustering or dispersal patterns within complex spatial configurations. Initially prevalent in urban planning, its application has since expanded to include villages, classical gardens, and traditional courtyards. Space syntax provides a quantitative framework to transcend descriptive analyses and rigorously investigate the spatial logic of these environments.

Many studies have underscored the value of space syntax in addressing critical challenges for heritage conservation. The existing literature primarily addresses the following six themes.

- (1)

- Research on ritual systems and traditional cultural embedding

These studies examine the traditional culture embedded in various architectural heritage sites through space syntax, with some focusing specifically on ritual culture.

Zhang D et al. analyzed the spatial features of the Beijing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Imperial Palace and revealed the similarities and differences between the office space, living space, and recreational space in these two palaces in terms of spatial enclosure and accessibility (2023) [15]. Chen H et al. revealed that the Humble Administrator’s Garden, an archetype of Chinese classical gardens, synthesizes literary narratives (“stories within a story”) with its multi-layered spatial configuration (“gardens within a garden”). It transformed physical spaces into narrative vehicles, creating an intertextual dialog between architectural topology and cultural semiotics (2023) [16]. Lü Mingyang, in a case study of the Wang Residence in Suzhou, combined the concepts of inside and outside from ritual culture with space syntax, exploring its spatial structure and control patterns, representing a new trend of introducing quantitative methods into traditional spatial culture research (2020) [17]. Cao Wei et al. explored the spatial organization characteristics of the classical private garden Heyuan (2018) [18]. In their comparative study of Tulou and Weilong Houses, Hu et al. analyzed the spatial configurations of these traditional dwellings, uncovering the substantial differences in social–spatial adaptability between the two architectural typologies (2023) [19].

- (2)

- Research on spatial configuration and historical evolution

These studies employ space syntax to explore the spatial patterns and diachronic evolutionary features of traditional courtyards and towns.

Hu C et al. demonstrated Jin Ancestral Temple’s balance between functionality and landscape value, as well as the dynamic adjustment of different architectural functions in its historical context (2025) [20]. Zhou K et al. studied the spaces of Daming Temple, Yangzhou City, in three different periods and explored its spatio-temporal characteristics and changes in the temple–residence–garden inter-relationship. Their results indicated that the dynamic spatio-temporal characteristics of the temple have been changing chronically (2023) [21]. Through a quantitative analysis of historical maps of the Huainan Salt Area (Jiangsu Province, China), Lu et al. revealed the details of production, transportation, and life in salt settlements, which differ greatly from the official perspective (2024) [22]. Pan Liao et al. explored the spatial patterns of Chinese historic towns by studying four well-preserved historic towns. They studied the differences between historical and current layouts, as well as the influence of Confucianism and Feng Shui culture (2021) [23]. Using space syntax, Dai Xiaoling et al. found that Jiangnan villages ensure social interaction through highly integrated public spaces and maintain privacy through local segregation, employing a “dual-efficient” structure (2020) [24]. Yan Chuqian et al., by analyzing configurational changes in Harbin residential spaces, revealed how the transformation from courtyard houses to apartments reflects the evolution of social structure and family concepts (2020) [25].

- (3)

- Research on functional adaptation and spatial perception

These studies employ space syntax to explore the functional adaptability and spatial perception characteristics of traditional courtyard layouts.

An Y. et al. analyzed the spatial configuration of Tibetan vernacular dwellings in Gannan’s agro-pastoral transition zone, China. Their study illustrated the cultural connotation and cultural essence conveyed by the vernacular residences and provided a scientific basis for the inheritance and development of Tibetan dwellings in Gannan (2023) [26]. Xu K et al. conducted a typological study of vernacular dwellings in Jinhua and Quzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, contrasting four core spatial elements: courtyard, central hall, principal chamber, and exterior space. Their study revealed distinctive spatial configurations shaped by geo-cultural particularities, demonstrating how local environmental adaptations result in divergent socio-spatial patterns in traditional settlements (2023) [27]. Saeid and Ghazaleh conducted a comparative analysis of traditional and modern residential dwellings in Hamedan, Iran, revealing a gradual erosion of domestic privacy in modern houses (2016) [28]. Lin Zhang et al. proposed spatial analytical methods for fire protection renovation in historic districts, enhancing safety through road network optimization, demonstrating the potential of space syntax for addressing complex functional challenges within heritage conservation (2023) [29]. Zhang Binghua et al. revealed that Nanjing Tulou (Fujian) simultaneously meets the needs of clan cohabitation and ritual order through a spatial organization centered on an ancestral hall with circulating corridors (2021) [30].

- (4)

- Research on conservation and sustainable development

These studies employ space syntax to explore conservation and sustainable development strategies for historic buildings and districts.

Wang G et al. developed an adaptability evaluation framework for historic buildings using complex adaptive system theory, proposing evidence-based adaptive reuse strategies (2021) [31]. Fu J-M et al. explored the spatial morphological characteristics of Fuzhou’s ShuiXiLin Historic District and proposed targeted strategies to enhance tourists’ spatial experiences (2025) [32]. Yuyan Lyu et al. studied Qingdao’s Yushan Historic District, revealing key spatial elements of vitality, identifying intervention priorities via urban vitality assessment, and proposing revitalization strategies (2023) [33]. Geng S et al. explored the street layout of Melbourne’s Chinatown and proposed urban design interventions to preserve heritage and advance sustainable cultural preservation practices (2022) [34]. Eldiasty et al. evaluated the conservation of the Historic Centre of Rosetta, Egypt, to support its potential UNESCO listing (2021) [35].

The above studies demonstrate that space syntax enables the visualization and quantification of spatial relationships within courtyards, villages, and other such spaces, and also elucidates the characteristics of human spatial behavior and cognition, thereby enhancing our understanding of the spatial layout mechanisms underlying architectural heritage.

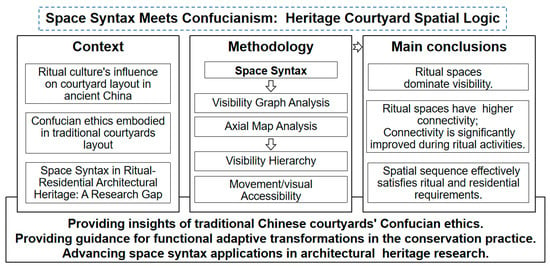

Despite recent advancements, a systematic and precise quantitative analysis of the spatial logic governing the ritual–residential dynamics of traditional courtyards remains lacking. This study applies space syntax to investigate the ritual–residential spatial organization of Prince Kung’s Mansion. The insights derived can provide valuable theoretical support for the protection and sustainable development of this architectural heritage, while enhancing our comprehension of the organizational structures within traditional Chinese courtyards in the context of ritual culture. The research framework is as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Object

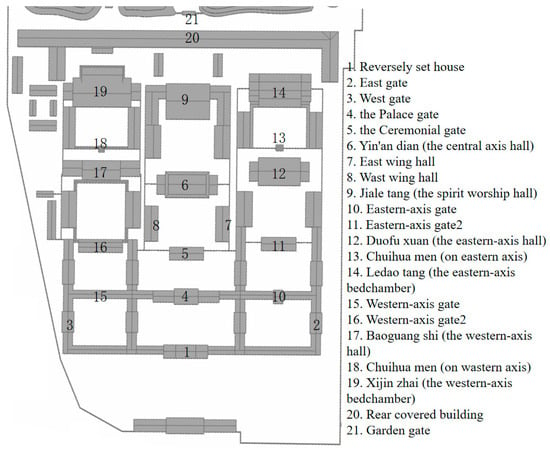

Prince Kung’s Mansion is situated in the northwestern part of Beijing’s Old City Inner City. It is arranged along three principal axes, which are subdivided into five rows (Figure 2). Originally, this site served as the residence of Emperor Qianlong’s tenth princess. As documented in the Records of the Qing Dynasty, Gaozong Chun (Qianlong) Huangdi Shilu, juan 1109, Qianlong 45th year, June, Part 2: “The former residence of Grand Secretary Li Shiyao was granted to the official Heshen to serve as the residence of the tenth princess.” Following Heshen’s conviction and the imperial order to commit suicide in the fourth year of the Jiaqing reign (1799), the Jiaqing Emperor bestowed Heshen’s residence upon his brother, Prince Qing (Yonglin), whereupon it was designated Prince Qing’s Mansion. Subsequently, in the thirtieth year of the Daoguang reign (1850), the Xianfeng Emperor granted Prince Qing’s Mansion to his brother, Prince Kung (Yixin). Prince Kung Yixin formally took residence on April 22nd of the second year of the Xianfeng reign (1852), establishing the mansion as Prince Kung’s Mansion (1852–1937).

Figure 2.

Plan layout of Prince Kung’s Mansion.

The three axes of the mansion consist of a central axis serving as a public ritualistic main axis and eastern and western axes that function as familial living quarters—front halls for reception and rear chambers for private residence.

The front two courtyard houses of the central axis are the palace gate and the ceremonial gate, which serve as a hierarchical forecourt space positioned at the front of the central axis. These gates were crucial spaces for official receptions and farewell ceremonies in ancient times. According to I Li, detailing the Zhou dynasty’s rituals and ceremonies, the host performed the ritual of “three bows with three deferrals” at the gate and in the courtyard before the hall when receiving guests. The courtyard where the main gate is located served as the preliminary space within the mansion’s ritual spatial sequence.

The third and fourth courtyard houses of the central axis, Yin’an Dian (the main hall) and Jiale Tang (the spirit worship hall), were the highest-ranking ritual halls within the entire compound. The central axis featured the greatest front width. Service lanes, which provide access to the main houses, were added along the eastern and western sides of the third and fourth courtyards. A Yuetai (a broad raised platform) and Danbi (a north–south-aligned imperial ramp) were situated in front of Yin’an Dian. Together, these ritual elements accentuated the supreme ritual status of the Yin’an Dian. Furthermore, the Yin’an Dian and its courtyard were positioned at the geometric center of the mansion compound, embodying the characteristic layout principle of placing the highest ritual space at the center of the site.

The third and fourth courtyards along both the eastern and western axes feature residences arranged according to the “front hall, rear bedchamber” principle. The front halls, structures like the Duofu Xuan and Baoguang Shi, functioned as ritual spaces for receiving guests and conducting rites. These areas exhibit an outward-oriented character. The Ledao Tang and Xijin Zhai constitute the rear bedchambers. Enclosed within independent courtyards accessed through distinctive chuihua gates (pendant flower gates, which partitioning courtyard spaces into inward- and outward-oriented areas), they form strongly inward-oriented residential compounds. The separation created by the chuihua gates distinctly demarcates inner and outer spaces, embodying the ancient Confucian ideological principles of gender segregation. Furthermore, adhering to the ancient Chinese tradition of revering the east over the west, the architectural complex on the eastern axis was of higher status than the complex on the western axis. This hierarchy manifested during the period when the estate functioned as the Residence of the Gulun Princess, with the Princess—who occupied a superior social rank—residing along the eastern axis, while Heshen (the father of the Princess’s husband)—who had the status of a subject—resided along the western axis. The fifth courtyard is the two-story, east–west-oriented rear service building. (Table 1)

Table 1.

The spatial functional classification of Prince Kung’s Mansion.

Within the mansion complex, the differentiation of circulation paths based on occupant status embodies the Confucian ideological principle of “hierarchy and distinction” between masters and servants. This is further manifested in the distinction between routes traveled for ritual activities versus daily life. The primary divergence in paths for masters and servants lies in the walking route: masters traverse along the central axis through the main gates, while servants utilize service passageways located along the four sides, accessing courtyards through side doors. Major service passageways flank the mansion on both the eastern and western sides. Furthermore, secondary service passageways are situated laterally to the central ceremonial halls—the Yin’an Dian and the Jiale Tang—facilitating servant circulation. The implementation of these secondary passageways achieves a dual purpose: (1) it fulfills essential service access requirements and (2) it accentuates the relatively independent spatial sequence of the central ceremonial courtyards arranged along the axis, reinforcing their symbolic central positioning.

There are side doors on both sides of the ceremonial gates (Yimen) along the central and east axes. When daily routines are carried out, these ceremonial gates remain closed, with passage allowed through the side doors. During ritual activities, however, the ceremonial gates are opened, allowing movement along the central axis. Additionally, movable screens are installed at three locations: inside the ceremonial gate along the west axis and inside the Chuihua gates leading to the rear residential courtyards of both the east and west axes. During daily routines, entering through these gates brings one face-to-face with these screens; passage into the courtyards requires a detour around either side of the screen. These screens function to delineate spatial areas and provide visual cover. During ritual activities, the screens are removed, which creates an unimpeded, direct passage route along the axis, thereby significantly enhancing the atmosphere of the ritual activities.

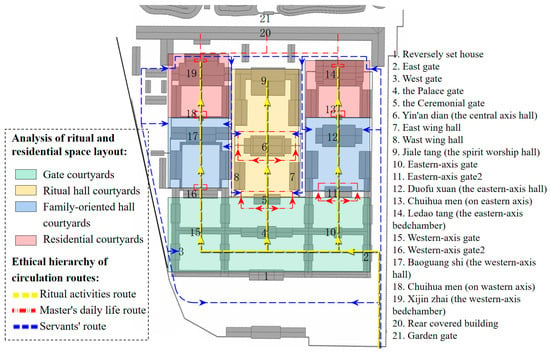

The ritual passage route, which is aligned with the central axis, enhances the accessibility of the ritual space. The daily passage route meanders along the axis. The service passage route used by servants avoids the main gate and central axis, primarily utilizing peripheral lanes and side courtyard gates, resulting in a circuitous and concealed path. These three passage routes exhibit distinct spatial connectivity patterns (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of spatial layout (Ritual vs. Residential) and hierarchical access in Prince Kung’s Mansion.

2.2. Methods and Process

- (1)

- Selection of analysis models

Space syntax is a theory and methodology based on mathematical graph theory, which is used to describe and explain the relationship between spatial configuration and social function. Depthmap 10 is a widely adopted software for spatial syntax analysis. This software converts spatial systems into topological graphs and automatically calculates the connections between spatial units. Its built-in models include Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA), Convex Maps, Axial Maps, and Segment Maps.

VGA reflects spatial connectivity and turning points in terms of visual perception. By applying VGA, visual integration and depth can be calculated, revealing levels of visibility in ritual and residential spaces. Axial map analysis identifies the maximum number of potential routes within a spatial system, where each route follows the principle of maximizing line length. A higher number of axial lines corresponds to greater movement and visual accessibility within the space, revealing levels of connectivity between ritual and residential spaces. Therefore, VGA and axial maps were selected as analytical models for this study, as they can be used to compute a series of core variables such as visual integration, visual depth, and axial integration. The specific variables used are described below.

Visual Integration Value (VIV): This specific numerical value indicates the strength of a point’s visual centrality. A high value identifies a visual focus area, whereas a low value indicates a visually marginal area or dead spot.

Visual Depth: The minimum number of visual steps (changes in direction) required to see a target from an observation point, measuring visual permeability. A higher value indicates a more concealed and less visually accessible location.

Mean Depth: The average of the depth values from one space to all other spaces. A lower value indicates higher overall accessibility.

Axial Integration: Integration based on the axial map, measuring the degree of connection and centrality of an axial line within the spatial system. A higher value indicates higher integration and stronger accessibility; a lower value indicates the opposite.

- (2)

- Research data preparation and base map construction

A plan was created in AutoCAD 2013 based on field measurement data and satellite imagery of Prince Kung’s Mansion. It was exported in DXF format and then imported into Depthmap 10 software to form the base map for this study.

- (3)

- VAG calculation and analysis procedures

- ①

- Import the base map into Depthmap.

- ②

- Generate the grid point map set: Set the grid spacing to 0.55 m, which aligns with the human perceptual scale, thus ensuring the validity of the analysis results.

- ③

- Calculate visibility: To reveal the spatial circulation structure and hierarchy, calculate and visualize axial integration.

- ④

- Calculate metrics: Select visual-based metrics in the analysis type; the software then automatically calculates metrics such as visual integration and mean depth for each point.

- ⑤

- Visualize outputs: Select different metrics (e.g., connectivity value, depth value) in the properties panel to obtain diverse analytical results.

- (4)

- Calculation and analysis of axial maps

- ①

- Import the spatial base map and draw axial lines using the toolbar.

- ②

- Construct the topological graph by connecting the axial lines.

- ③

- Calculate axial integration to reveal the spatial circulation structure and hierarchy.

- ④

- Visualize outputs: axial integration is achieved.

- (5)

- Analytical logic and research objectives

- ①

- The aim of this study was to verify the logical relationship between spatial ritual hierarchy and spatial visibility level. Using the visibility level of each space in Prince Kung’s Mansion, as determined by VGA, this study aimed to verify the outward–inward progression from public ritual spaces to family ritual spaces and further to residential spaces.

- ②

- By quantifying the connectivity of each space in Prince Kung’s Mansion using axial maps, this study sought to verify the relationship between spatial ritual hierarchy and spatial connectivity level and that ritual axes and ritual spaces require higher connectivity than residential spaces.

- ③

- To verify differences in spatial performance under different functional modes, a comparison of axial maps was designed, with entrance/exit control as the key variable, to quantify the differences in accessibility between ritual activity and daily life spaces, thereby revealing the adaptive regulation mechanism of spatial performance.

3. Results

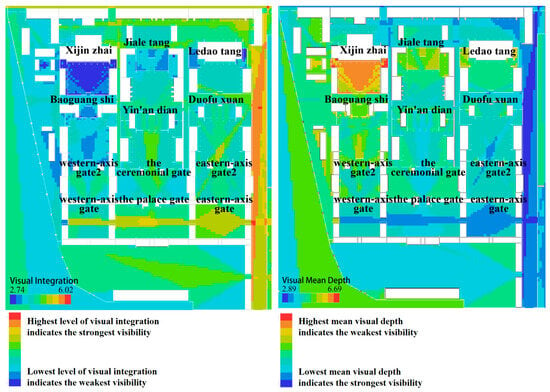

3.1. VGA

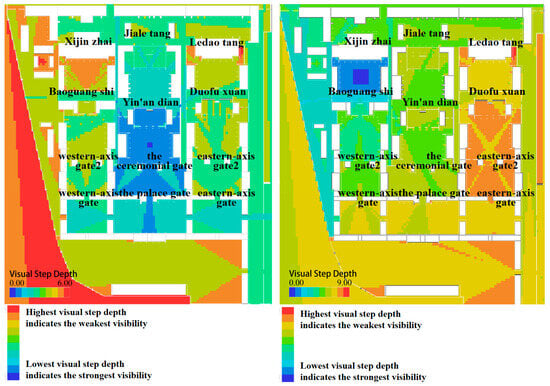

The VGA for Prince Kung’s Mansion yielded the visual integration and visual mean depth (Figure 4). As a public and externally oriented ritual space, the courtyard of the Yin’an Dian was subjected to a separate visibility analysis to examine its visual depth distribution (Figure 5 left). In contrast, the Xijin Zhai, representing the most internally focused and spatially enclosed house, had its courtyard analyzed separately for visual depth distribution (Figure 5 right). A comparative analysis of the visual depth distributions between these two functionally distinct spaces was then conducted.

Figure 4.

Visual integration of Prince Kung’s Mansion (left). Visual mean depth of Prince Kung’s Mansion (right).

Figure 5.

Visual step depth of Yin’an Dian (left). Visual step depth of Xijin Zhai (right).

VGA of Prince Kung’s Mansion revealed the following visual integration distribution for both ritual and residential areas: palace gate courtyard > Danbi (elevated ritual path) and Yuetai (the broad raised platform) before the Yin’an Dian (central axis hall) > the ceremonial gate courtyard > Duofu Xuan (eastern-axis hall) courtyard > Jiale Tang (spirit worship hall) courtyard > Ledao Tang (eastern-axis bedchamber) courtyard > Baoguang Shi (western-axis hall) courtyard > Xijin Zhai (western-axis bedchamber) courtyard. Overall, the highest Visual Integration Values (VIVs) were found for the first three courtyards preceding the palace gate, followed by the Danbi and Yuetai before the Yin’an Dian and then the Duofu Xuan Courtyard. The Xijin Zhai Courtyard in the western residential area demonstrated the lowest integration. Visual integration is inversely proportional to visual depth (Table 2).

Table 2.

The average VIVs of ritual and residential spaces.

The VGA of the Yin’an Dian and Xijin Zhai revealed significant differences. The Yin’an Dian, the geometric center with the highest ritual status, exhibits a visual depth of 6.00. This is notably less than the Xijin Zhai’s depth of 9.00, which demonstrates the strongest inward orientation and optimal enclosure. Moreover, the Yin’an Dian’s visual depth shows a relatively uniform distribution across viewing directions, whereas the visual depths from the Xijin Zhai to the palace gate and to the houses in the East Road are considerable.

3.2. Axial Map Analysis

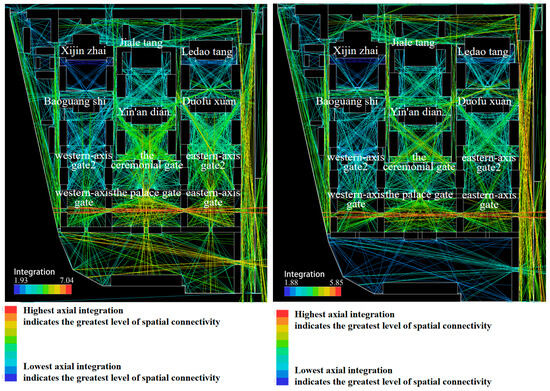

There were notable differences in circulation routes between daily life and ritual activities at Prince Kung’s Mansion. To compare the differences between these two contexts, axial map calculations were conducted separately for each circulation scenario. Based on historical documents detailing gate-opening arrangements for daily life and ceremonies, the daily circulation was configured as follows: the ceremonial gates on the central and east axes were closed, with only the doors located to their east and west remaining open. The ritual activity circulation state was configured as follows: all openable central gates along the route were opened, and three removable screen walls located behind the west axis ceremonial gate and behind the two chuihua gates were removed, enabling direct axial movement along the route. Axial map calculations were performed according to these two defined circulation states, yielding the integration values (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Axial map integration during daily life in Prince Kung’s Mansion (left). Axial map integration during ritual activities in Prince Kung’s Mansion (right).

During daily life, the integration values ranged from 1.88 to 5.85. During ritual activities, these values ranged from 1.93 to 7.04. The distribution of integration values remains largely consistent for both daily life and ritual activities. Overall, the mean integration values of the axial maps, ranked from highest to lowest, were as follows: palace gate courtyard > Yin’an Dian courtyard > Duofu Xuan courtyard > Jiale Tang courtyard > Ledao Tang courtyard > Baoguang Shi courtyard > Xijin Zhai courtyard.

During ritual activities, the axis integration values of the courtyards, with a peak of 7.04, were significantly higher than those during daily life periods, the latter peaking at 5.85. Compared to daily life periods, the integration values of both the palace gate courtyard and the Yin’an Dian courtyard increased significantly, indicating enhanced connectivity during ritual activities.

4. Discussion

4.1. VGA Reveals Ritual–Residential Spatial Logic by Visibility Level

VGA elucidates the hierarchical visibility of ritual and residential spaces: (1) The outermost forecourt preceding the palace gate, functioning as a circulation and ritual space, exhibits the highest VIV. This reflects its role as the primary space for receiving and seeing off guests in historical protocols, demonstrating exceptional spatial visibility as a front buffer area. Its prominence provides strong visual guidance within the overall courtyard space. (2) The Yin’an Dian, as the highest-ranking ritual space, features a prominent VIV along its central north–south Danbi. This superior VIV signifies excellent visual control and panoramic sight lines within this ceremonial node. During major public rituals, the movement of hosts and guests along the central axis via the Danbi ensured that this space maintained significant visual prominence and oversight. (3) The Duofu Xuan and Baoguang Shi, as semi-private transitional family–ritual areas, have an intermediate VIV, as they are positioned between the highly public spaces (Yin’an Dian) and the private residential spaces (Xijin Zhai and Ledao Tang). This intermediate VIV reflects their role as family–ritual spaces for receiving guests, embodying their nature as transitional spaces between public and private areas. (4) The inward residential spaces, the Ledao Tang and Xijin Zhai courtyards, have low VIVs. Positioned along the west route, the Xijin Zhai displays the lowest VIV, signifying its seclusion as a private unit. Although the Ledao Tang also features an independent courtyard, its higher VIV relative to the Xijin Zhai stems from its proximity to the east lane, which increases its visual permeability.

VGA indicates a significant difference in visibility between the Yin’an Dian and Xijin Zhai: (1) The visual control scope of the Yin’an Dian (ceremonial core) courtyard primarily encompasses the interior hall space and its immediate courtyard. It extends significantly to include most of the courtyard outside the ceremonial gate and forms a linear corridor along the central axis extending beyond the palace gate. This results in a large effective area of visual control. (2) In contrast, the visual control scope of the Xijin Zhai (residential core) courtyard is confined to its own courtyard space. Consequently, it exhibits a significantly smaller effective area of visual control.

These findings demonstrate that there is a positive correlation between spatial visibility level and ritual hierarchy, where spatial areas higher in the ritual hierarchy have higher visibility. The visibility level is epitomized through spatial segregation, which manifests in two primary ways. First, the palace gate and ceremonial gate establish a clear distinction between the external and internal areas. These gated courtyards, functioning as outward-oriented spaces, exhibit high visibility. Second, the Chuihua gates located at the front of the eastern and western bedchamber courtyards, further enclose the residential quarters, creating distinct inward-oriented spaces. The spatial harmony between ritual and residential areas in Prince Kung’s Mansion is thus established. It embodies traditional Confucian ideological principles, including gender segregation and hierarchy.

4.2. Axial Maps Reveal Spatial Etiquette Hierarchy by Connectivity Level

Axial map analysis reveals both commonalities and partial divergences between daily life and ritual activities in Prince Kung’s Mansion.

The commonalities are reflected in the following aspects: (1) There is a hierarchy of connectivity among the three primary axes. The central axis exhibits the highest integration value, followed by the eastern axis, while the western axis ranks the lowest. The central axis, designated exclusively for ceremonial functions, achieves optimal connectivity, reflecting its supreme ritual status within the spatial hierarchy. (2) The eastern axis shows significantly higher integration than the western axis due to two key factors. First, it has three direct exits linked to the highly accessible eastern service lane. Second, the ceremonial gate on the eastern axis is flanked by side gates, unlike the western axis, which only has a central gate. The greater integration of the eastern axis aligns with traditional Chinese principles, which prioritize eastern orientation for elevated status. (3) The Yin’an Dian, the centrally located hall, exhibits a higher level of integration compared to the surrounding houses, affirming its role as the preeminent ritual space with optimal connectivity.

These differences manifest in the following aspects: (1) During ritual activities, the opening of the central passageways at the ceremonial gates on both the central and eastern axes significantly increased the integration of the Yin’an Dian and Duofu Xuan. This resulted in a marked increase in potential movement paths, thus heightening the connectivity of these halls during rituals. (2) Removing the three removable screen walls increased movement paths and enhanced direct connectivity along the axes during ritual activities. These differences in connectivity between ritual activities and daily life highlight the enhanced connectivity required during rituals.

Furthermore, because axial map calculations adhere to the principle of longest and fewest lines, paths that are perpendicular to the axis direction are not the longest lines and are not explicitly represented. Consequently, the model fails to directly depict straight-line movements along the axes that would occur during rituals, lacking a more intuitive visualization of the primary axial pathways. It can be inferred that there were more vertically accessible routes along the ritual axis during ceremonial activities.

These results demonstrate that the selection of the central axis for ritual activities and the geometric center for core ritual spaces aligns with the ancient Chinese principle of centrality as orthodoxy. This ensures that higher-status ritual spaces exhibit superior connectivity.

5. Conclusions

This study employs space syntax to demonstrate the spatial harmony between ritual and residential spaces and reveal the ancient Confucian ideological principles embedded in traditional Chinese courtyards. The conclusions are as follows:

(1) VGA elucidates the ritual–residential spatial logic in Prince Kung’s Mansion through the spatial visibility gradients. Visibility progressively decreases from public ritual areas to familial ritual areas and finally to residential areas. This gradation is achieved through physical segregation elements, such as the palace gates and chuihua gates, achieving spatial harmony between ritual and residential functions. These patterns demonstrate the Confucian principle of delineating interior and exterior domains and gender segregation.

(2) The axial maps demonstrate a positive correlation between spatial connectivity level and ritual hierarchy in Prince Kung’s Mansion. The central ritualistic axis exhibits greater connectivity compared to the residential axes located in the east and west wings, and the east axis exhibits significantly higher connectivity than the west axis. Furthermore, centrally located halls exhibit higher connectivity compared to bedchambers in peripheral areas. This spatial arrangement embodies the Confucian ideological principles of centrality as orthodoxy and prioritization of the eastern orientation. Additionally, comparative analysis of ritual activities and daily life highlights the significance of enhancing spatial connectivity during rituals.

(3) The convex space maps confirm a positive correlation between ritual hierarchy and spatial accessibility in Prince Kung’s Mansion. This was demonstrated in the author’s previously published conference paper [36]. The results reveal a progressive reduction in accessibility from the palace gate through the ceremonial halls and family halls to the private bedchambers. This gradient in topological depth further elucidates the mansion’s spatial hierarchy, which is characterized by graded transitions between extroversion and introversion and between publicness and privacy.

This study enhances our understanding of the organizational mechanisms governing ritual–residential spaces in traditional Chinese courtyards. Numerous traditional courtyards dating from the Ming and Qing dynasties survive in China today and urgently require conservation and appropriate functional retrofitting. Focusing on Prince Kung’s Mansion as a case study, this research provides scientific and historical evidence to inform their spatial transformation. It also presents a methodological framework applicable to similar studies focusing on the ritual–residential spaces of historic courtyards.

It is important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of this research. This study focused solely on Prince Kung’s Mansion, potentially restricting its broader applicability. To develop a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between ritual and residential spaces across various societal strata, future research should expand the scope to include official residences and commoner dwellings. A comparative analysis of courtyard spaces across various social strata will reveal a broader range of traditional courtyard patterns integrating ritual and residential functions, providing empirical evidence of their variability and universality for informed heritage preservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and T.L. (Tingfeng Liu); methodology, P.G., T.L. (Taifeng Lyu) and T.L. (Tingfeng Liu); software, P.G., F.L. and Y.S.; validation, P.G. and T.L. (Taifeng Lyu); formal analysis, P.G., F.L. and Y.S.; investigation, P.G., T.L. (Tingfeng Liu) and T.L. (Taifeng Lyu); resources, P.G. and F.L.; data curation, P.G. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G.; writing—review and editing, T.L. (Taifeng Lyu); visualization, T.L. (Taifeng Lyu); supervision, T.L. (Tingfeng Liu); project administration, P.G.; funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Later-stage Funding Project of the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 24FYSB028; the Doctoral Startup Fund of Qingdao Agricultural University, grant number 663/1123004; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32301653; and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China, grant number ZR2023QE079.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the investigation and field experiment, Zhuang Zhang, affiliated with Prince Kung’s Mansion Museum, provided us with considerable support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu, P.S.; Zhang, M. Trans. & Annot. In Li Ji (Book of Rites) [Annotated edition]; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.N. A Study on Ancient Chinese Construction Engineering Management and Architectural Hierarchy System; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.T. (Ed.) Institutional Regulations of Chinese Architectural History Through the Dynasties (Vol. 1 & Vol. 2); Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. Chinese Architectural Aesthetics; Heilongjiang Science and Technology Press: Harbin, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2009. Original work published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Collected Theses on the History of Chinese Architecture; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ruitenbeek, K. Chinese Housing, Shelter and Society: Theory, Research, and Policy for Vernacular Architecture; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WL, USA, 1996; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, X. The choice of official residence forms and the spread of courtyard-style dwellings in the Ming Dynasty. In Collected Essays on Chinese Architectural History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H. Huaxia Yijiang: Analysis of Design Principles of Chinese Classical Architecture; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2005; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Layout Principles and Major Types of Traditional Chinese Axially Symmetrical Courtyards: A Preliminary Research Proposal. Architect 2012, 156, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G. Architectural Typology: From Hall to Chamber—A Series of Studies on Traditional Chinese Residential Architecture. Architect 2016, 182, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, N.; Yan, X. Ritual Behavior at the Coronation Ceremony in the Zhouyuan Fufeng Yuntang Site during the Western Zhou Dynasty. Garden Archit. Technol. 2021, 4, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L. The Hall and Chamber Layout of Tang Dynasty Officials as Seen in the Great Rituals of the Kaiyuan Era. Architect 2020, 207, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Shan, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y. Spatial Feature Analysis of the Beijing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Imperial Palace Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, L. Analysis of Narrative Space in the Chinese Classical Garden Based on Narratology and Space Syntax—Taking the Humble Administrator’s Garden as an Example. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, M. Spatial Layout of the Wang Residence in Suzhou: A Study Based on Space Syntax. Archit. J. 2020, 620, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Xue, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, L.H. Analysis of spatial organization characteristics of He Garden in Yangzhou using space syntax. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, T. Landed and Rooted: A Comparative Study of Traditional Hakka Dwellings (Tulous and Weilong Houses) Based on the Methodology of Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Qi, Y.; Wang, C. An Analysis of the Spatial Characteristics of Jin Ancestral Temple Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2025, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wu, W.; Dai, X.; Li, T. Quantitative Estimation of the Internal Spatio–Temporal Characteristics of Ancient Temple Heritage Space with Space Syntax Models: A Case Study of Daming Temple. Buildings 2023, 13, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Li, X.; Liao, Y. Neglected vertical linkage: A study on the form of the canal network in the Huainan Salt Area during the Ming and Qing dynasties using space syntax measurements. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Gu, N.; Yu, R.; Brisbin, C. Exploring the spatial pattern of historic Chinese towns and cities: A syntactical approach. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Pu, X.; Dong, Q. Exploring the deep spatial structure of traditional villages using space syntax methods. China Landsc. 2020, 36, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.Q.; Ma, H.; Liu, D.P. Interpretation of Harbin modern residential culture based on space syntax. Archit. J. 2020, 22, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, P. An Analysis of the Isomerism of Tibetan Vernacular Dwellings Based on Space Syntax: A Case Study of the Semi-Agricultural and Semi-Pastoral District in Gannan Prefecture. Buildings 2023, 13, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chai, X.; Jiang, R.; Chen, Y. Quantitative Comparison of Space Syntax in Regional Characteristics of Rural Architecture: A Study of Traditional Rural Houses in Jinhua and Quzhou, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitajer, S.; Nojoumi, G.M. Privacy at home: Analysis of behavioral patterns in the spatial configuration of traditional and modern houses in the city of Hamedan based on the notion of space syntax. Front. Archit. Res. 2016, 5, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, F.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Z. Spatial configuration of fire protection for historical streets in China using space syntax. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 59, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.H.; Wang, Z.Q.; Chen, J.W. Analysis of the Ethical Function of “Space-Path” in Fujian Nanjing Tulou. J. China Cult. Herit. 2021, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Liu, S. Adaptability evaluation of historic buildings as an approach to propose adaptive reuse strategies based on complex adaptive system theory. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 52, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-M.; Tang, Y.-F.; Zeng, Y.-K.; Feng, L.-Y.; Wu, Z.-G. Sustainable Historic Districts: Vitality Analysis and Optimization Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2025, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Malek, M.I.A.; Ja, N.H.; Sima, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Z. Unveiling the potential of space syntax approach for revitalizing historic urban areas: A case study of Yushan Historic District, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Understanding the Street Layout of Melbourne’s Chinatown as an Urban Heritage Precinct in a Grid System Using Space Syntax Methods and Field Observation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldiasty, A.; Hegazi, Y.S.; El-khouly, T. Using Space Syntax and Topsis to Evaluate the Conservation of Urban Heritage Sites for Possible Unesco Listing the Case Study of the Historic Centre of Rosetta, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 4233–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, T.; Lyu, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, F. Study on the ritual layout of Prince Kung’s Mansion: Space syntaxtheory as evidence. In Proceedings of the 8th Tianjin University Academic Conference on Architectural Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2025; pp. 118–125. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).