Abstract

With accelerated population aging, the importance of older adults’ self-rated health is constantly increasing. Self-rated health is influenced by complex relationships between the built environment and psychosocial factors. Therefore, this study constructs a pathway framework of “material (housing quality and environmental pollution)–psychological (depression and social capital)–self-rated health” elements to explore the influencing mechanism of older adults’ self-rated health. This study utilized the 2018 China Labor Force Dynamics Survey Database to explore the relationship between built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution), depression, social capital, and older adults’ self-rated health, using structural equation modeling. The heterogeneity between urban and rural areas is also analyzed. Better housing quality and less environmental pollution were found to be related to higher levels of self-rated health. Depression and social capital were important mediators in the relationship between housing quality, environmental pollution, and self-rated health. Regarding urban–rural heterogeneity, the direct impact of environmental pollution on self-rated health was only significant among urban older adults. Secondly, the multiple mediating roles of social capital were only reflected among rural older adults. The government and relevant entities should promote improvements in housing quality and reduce environmental pollution to achieve a healthy and livable environment.

1. Introduction

The global population is aging at a constantly accelerating pace. According to a United Nations report, by the mid-2030s, the global population of people over 80 years of age will reach 265 million, exceeding the number of infants. Globally, older adults aged 65 years and above are expected to exceed the number of children under the age of 18, reaching 2.2 billion [1]. Chinese statistics show that in 2024, 15.6% of the total national population was aged 65 years and above [2]. Moreover, the population of adults aged 60 years and above in China is estimated to reach 500 million by 2050 [3]. With the prominent issue of population aging, older adults are increasingly playing an indispensable role in future development. The health condition of older adults has become a key area of governments and academic research in various countries, receiving sustained and extensive attention. However, there is relevant evidence indicating that the health condition of older adults in China is not ideal. According to a 2019 report, the number of adults aged 60 years and above in China reached 249 million, among whom nearly 180 million older adults experience chronic disease [4]. Furthermore, subclinical depression was reported by nearly two-fifths of older adults [5]. Faced with the enormous challenges of aging, the UN General Assembly emphasizes that health is at the heart of older adult experience and opportunities and promotes healthy aging for the decade between 2020 and 2030 [1]. The “14th Five-Year Plan for Healthy Aging” of the Chinese government proposes the implementation of comprehensive and systematic intervention measures to meet the health needs of older adults. This policy recognizes the need to improve older adults’ health by creating healthy and livable environments [6].

For older adults, health is the solid foundation for achieving a high-quality life. As an effective, simple, and easy evaluation method, self-rated health is of great significance in comprehensively reflecting the physical and mental health conditions of older adults [7,8]. Previous studies have indicated that self-rated health is influenced by material, psychosocial, and behavioral pathways [9]. According to the theory of health ecology, health is the result of interactions between innate factors, medical and health services, the physical built environment, and the social environment [10,11]. As a material pathway, a high-quality built environment positively contributes to self-rated health status [12]. The built environment is an important space for daily activities and living, and components such as housing quality and environmental pollution play a key role in individual health. Especially for older adults, the functional weakening brought about by aging often results in older adults spending more time in their homes and the surrounding environment, making them more vulnerable to the influence of related factors [13]. Specifically, low-quality housing (e.g., dampness, crowding, darkness, and poor ventilation) leads to poor health in older adults [14,15]. Older adults perceive that environmental pollution may have a negative impact on their cognitive functions and is not conducive to the health of older adults [16]. Regarding psychosocial approaches, factors such as depression, stress, and social capital affect self-rated health [17,18,19]. Behavioral pathways include factors such as substance use, physical activity, and diet, which can affect self-rated health [20]. The material pathway may also be associated with self-rated health by influencing the psychosocial factors. Improvements in the built environment may alleviate individual depressive symptoms [21] and promote trust among neighbors [22], which may affect older adults’ self-rated health. Furthermore, the urban–rural disparity is a key factor that should be considered in exploring the influence mechanism of self-rated health and has received long-term attention from the academic community. Most of the early studies were concentrated in Western countries, and there is not yet a unified conclusion on the issue of urban–rural disparities in residents’ health. A study in the United States shows that due to public health, diet, and other reasons, residents in rural areas tend to have poorer health indicators than their peers living in cities [23]. Some other Western studies have produced different results. With the increase in urbanization, the deterioration of urban physical and social factors has occurred, making urban residents more prone to mental illness [24]. This phenomenon seldom occurs in developing countries. This is because Western countries have already reached the stage of counter-urbanization. The extensive development patterns of early cities resulted in a series of issues, including overcrowding, inadequate provision of public services, and insufficient infrastructure. These adverse conditions prompted socioeconomically advantaged groups to relocate to suburban or rural areas with superior environments, while urban areas have become gathering places for low-income populations [25]. However, significant differences exist between China and Western developed countries in social background, including economic, cultural, and institutional domains. Owing to the continuous influence of the household registration system, urban–rural dual structure, and unbalanced level of socioeconomic development, Chinese urban areas exhibit greater advantages of public health services, employment opportunities, and social structural conditions compared to rural areas. Moreover, the long-term restrictions of the household registration system make the transformation from rural household registration to urban household registration quite difficult [26], and non-urban household registration makes it hard to enjoy complete urban public services. This makes the urban–rural heterogeneity influencing mechanism of self-rated health of older adults in China unique, and current studies have not fully analyzed this.

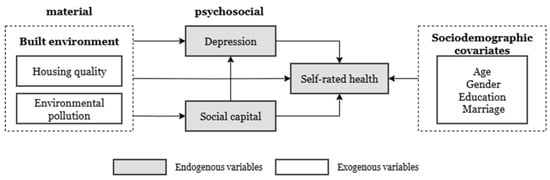

An existing study classifies the main influencing pathways of self-rated health into three types: material (built environment), psychological (social capital, depression, etc.), and behavioral (smoking, drinking, etc.) [9]. Meanwhile, the theory of health ecology emphasizes that the influencing factors at all levels of health have the important characteristic of interaction [27]. Many prior studies have also discovered the influence relationship between material–built environment factors and psychosocial factors. This indicates that the three pathways not only have a direct impact on self-rated health but there may also be an indirect interrelationship among the pathways. However, although most current studies support the role of building environmental factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) in older adults’ self-rated health, the interaction mechanisms among the different influence pathways have not been fully explored. Therefore, this study theoretically constructed a research framework of “material (built environment)–psychological (depression and social capital)–self-rated health” elements (Figure 1) to explore the impact path of older adults’ self-rated health. Furthermore, existing studies predominantly focus on urban–rural disparities in residents’ health in Western developed countries. Against the background of China’s special household registration system and dual urban–rural structure, this perspective cannot be fully applicable to explaining the distinct mechanisms of older adults’ self-rated health in urban and rural areas of China. Thus, this study will also explore the heterogeneity of the self-rated health impact pathways of older adults that may be caused by the urban–rural disparity in China. In conclusion, based on the 2018 China Labor Dynamics Survey (CLDS), this study adopted structural equation modeling to analyze the relationship between built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) and older adults’ self-rated health. It also considered the mediating role of depression and social capital in this relationship, as well as possible urban–rural heterogeneity.

Figure 1.

Framework.

1.1. Self-Rated Health and Its Influencing Pathways

Self-rated health can be understood as “a summary statement combining many aspects of health, including the subjective and objective aspects, within the perceptual framework of the responder”. It originates from active cognitive processes and is not guided by formal rules or definitions. Self-rated health is a common method of measuring individuals’ subjective perceptions of their health. It provides an individual’s overall health status, including their physical and psychosocial health, and is related to future health outcomes [28,29]. Several studies have shown that self-rated health can strongly predict the mortality rate of various diseases [30,31,32]. Moreover, compared with objective health indicators, self-rated health has a stronger connection with an individual’s actual individual health outcomes [28,33]. As a single health indicator, self-rated health is generally measured using the following question: How do you evaluate your health? Respondents rate their current health status on a 4- or 5-point scale, ranging from poor to excellent. Self-rated health has received extensive attention from the academic community owing to its simple measurement and significant predictive ability for individuals’ future health. Especially for older adults, declining physiological function may affect their willingness to participate in the assessment as well as the validity of the assessment and may increase survey costs. Therefore, for research related to older adults, it is crucial to find simple and effective methods to measure health conditions [8].

Research on the health of older adults has recently increased substantially. Studies on the various determinants of self-rated health have also received more attention. According to Moor et al. [9], differences and inequalities in self-rated health are mainly affected by material, social, and behavioral pathways. Regarding the material pathway, the materialist/structuralist explanation of health disparities and inequalities stems from the effects of physical and structural conditions, including housing conditions, neighborhood, work conditions, and financial conditions [34,35,36]. A German study reported the connection between homeownership and self-rated health [37]. People living in poor-quality housing are more likely to have poor health conditions [12]. At the same time, studies have shown that communities with outdoor spaces and convenience help improve the self-rated health of older adults [38]. Secondly, poor working environments and long working hours negatively affect individual health and well-being [39,40], and this effect may vary among professionals [39]. Extending commuting time can induce stress [41], and the experience of stress can be affected by different commuting methods [42]. Additionally, socioeconomic conditions are regarded as key factors underlying differences in individual health status. People with a lower socioeconomic status are more likely than other socioeconomic groups to experience adverse health outcomes such as increased rates of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health problems [43,44].

Regarding the psychological pathway, the association between psychosocial factors, including perceived stress, depression, and social capital, and self-rated health becomes more significant as age increases [45]. A study on Asian immigrants showed that cultural adaptation stress is associated with poor self-rated health, with social support mediating this relationship [46]. Longitudinal studies on older adults suggest that depression may be a risk factor for self-evaluated health, independent of physical illness and dysfunction [17]. Furthermore, regarding social capital, experts from different research fields have defined it from different perspectives. The most frequently adopted definition of social capital originated from Putnam, who defined social capital from the perspective of social cohesion as “features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions” [47]. Social capital, as an individual’s asset, represents an individual’s ability to gain benefits through membership in social networks and other social structures. Through social capital, individuals can obtain certain benefits and resources that exist in the structure of their social networks, and these benefits and resources would be impossible to obtain without social networks [48]. Compared with lower social capital, having higher social capital usually means that an individual establishes stronger social connections with others [49] and obtains more social resources and benefits through contact with others. Social capital can influence health in older age through several channels [18]. The resource hypothesis holds that an individual’s subjective evaluation of their health is influenced not only by diseases and family history but also by the external environment of the family and community [33,50]. For instance, social capital can enhance older adults’ self-rated health through conveying health-related information and encouraging healthier lifestyles [18]. Meanwhile, enhancing social capital can also improve the access of older adults to better health care services and comprehensive support services, to optimize the health of older adults [19].

Finally, regarding behavioral pathways, differences in substance use (e.g., smoking and drinking), physical activity, and diet are generally considered to affect self-rated health [20]. Low levels of self-rated health later in life are associated with smoking [51]. Additionally, there is a more complex influence relationship between alcohol consumption and self-rated health among older adults. A longitudinal study of older adults in the United Kingdom reported that non-drinkers had a higher chance of poor self-rated health. The results ten years later showed that individuals who stopped drinking alcohol early were more likely to report future improvements in their self-rated health [52]. Additionally, older adults with a higher level of physical activity and healthy eating habits are associated with a higher self-rated health level [53,54]. Thus, material, psychosocial, and behavioral pathways are of great significance in exploring the determinants of older adults’ self-rated health.

1.2. The Relationship Between Housing Quality, Environmental Pollution, and Self-Rated Health

The theory of health ecology posits that health is the result of interactions between innate factors, medical, and health services, the physical built environment, and the social environment [10,11]. Meanwhile, the theory of social determinants of health holds that, apart from the factors that directly cause disease, the decisive social conditions and basic structures in people’s living and working environments are “underlying factors” that influence health, including income, education, and the living environment [55]. Both theories emphasize that the environment, especially the built environment, is an important determinant of individual health. According to Sallis (2009) [56], the “built environment” refers to all buildings, spaces, and objects created or transformed by humans, including residences, schools, and workplaces [56]. The connection between the built environment and health has been broadly explored in academia [14,15]. As a part of the material pathway, the built environment has an important influence on individual health [57].

Housing and pollution are important components of the built environment and significant public health issues [58]. The impact of housing on health can be described based on four factors: stability, quality, affordability, and neighborhood [59]. Specifically, stable housing can reduce stress and anxiety and support health [60]. Affordable housing costs, such as house prices, positively affect self-rated health, and this impact intensifies with age [61]. Regarding housing quality and conditions, the results of a panel data study in the United Kingdom showed that housing conditions such as overcrowding, lack of indoor bathrooms, lack of access to hot water, and absence of gardens lead to poor health [14]. Living in a damp and moldy housing environment is likely to cause respiratory problems [15]. Odgerel et al. [62] found that individuals who did not encounter housing problems, such as temperature, acoustics, lighting, sanitation, and safety, had a better quality of life than those who did encounter problems, which in turn is conducive to their physical and mental health. A study in China indicated that the improvement of housing conditions can reduce the possibility of poor self-rated health status and can have a sustained and beneficial impact on self-rated health [63]. The deterioration in health caused by aging often makes older adults vulnerable to the negative impact of low-level housing [64]. Moreover, a lack of employment increases the time that older adults spend in their homes, making it easier for them to be exposed to poor housing conditions for longer periods [13]. Additionally, the neighborhood aspects of housing are mainly concentrated outdoors [59]. Environmental pollution, an important component of the outdoor environment, has a meaningful impact on self-rated health. Perceived environmental quality, which is related to factors such as air quality, noise, and olfactory pollution, plays an important role in self-rated health [65]. Studies have shown that both indoor and outdoor air pollution are significantly associated with the health of older adults [66]. Older adults often experience higher levels of environmental pollution, such as air, water, and noise pollution, which affect their cognitive functions and leads to poor health [16].

The built environment is related to depression and social capital. Regarding the relationship between the built environment and depression, current research generally holds that exposure to poor-quality housing negatively affects physical and mental health [67]. A study on the impact of the living environment on depressive mood found that built environment factors such as housing quality, parks, and air/noise pollution are related to depression [21]. Crowded and shared spaces may escalate poor contact and stimulation, leading to poor interpersonal relationships and stress [68]. Older adults living in leaky houses have a higher incidence of mental illness. A well-ventilated environment is conducive to improving symptoms of depression and anxiety in older adults [69]. Poor housing air quality caused by cooking fuels, indoor smoke products, and second-hand smoke is likely to cause sleep disorders and depressive symptoms in older adults [70].

Social capital is the collective interest derived from developing and maintaining a powerful social network. The built environment and social capital share an important and complex connection [71]. Specifically, factors such as population density, degree of land-use mix, street design, and destination accessibility are related to social capital [72]. The built environment of communities is also considered an important link in encouraging social capital formation and promoting healthier lifestyles [73]. Relatively few studies have been conducted on the relationship between housing quality and social capital, with a greater focus placed on exploring housing ownership. Studies have found that homeowners are more involved in local social networks [74] and have stronger community cohesion than renters [75]. However, studies still suggest that a better internal housing environment may help increase trust among neighbors. A well-designed and well-equipped housing environment is crucial for social trust and health [22]. Furthermore, environmental pollution hinders social capital development. Some studies have shown that air pollution can restrict face-to-face social interactions between neighbors, which may lead to poor mental health [76]. Social capital can serve as a buffer between environmental hazards and individual health status [77]. Therefore, depression and social capital, as psychosocial pathways affecting self-rated health, may be influenced by the material built environment.

Owing to the typical urban–rural separation in Chinese society, older adults living in rural and urban areas are exposed to different built environments, which may lead to different health conditions [78]. Existing studies have shown that compared with the rural population, the urban population has a significantly better self-rated health status [79]. Improvements in built environment factors can promote the health level of older adults in both urban and rural regions, while promoting green spaces is even more important for the health of urban older adults [78]. Due to the dense population and active industry in urban areas, the concentration of air pollution and air circulation are lower than those in rural areas, making the negative impact of air pollution on health more significant for urban residents [80]. However, studies have shown that urban residents’ prolonged exposure to environmental pollution alleviates anxiety through diversified social support networks and reduces the adverse health effects of environmental pollution. Owing to their limited social support networks, rural residents are more vulnerable to the negative effects of environmental pollution [81]. From the perspective of urban–rural differences, the impact of environmental pollution on health requires further exploration. Furthermore, improvements in housing conditions have obvious health benefits in both urban and rural areas [55]. The profound disparity in social and economic development between urban and rural areas in China makes the built environment in urban areas significantly better than that in rural areas [82]. This spatial differentiation urgently requires the study of the different health impact mechanisms it may have in urban and rural areas.

Self-rated health is influenced by material, psychological, and behavioral pathways. Material pathways include built environment factors, whereas psychological pathways include factors related to depression and social capital. However, few studies have explored the influence of material–built environment factors on older adults’ self-rated health through depression and social capital. Furthermore, the regional differences brought about by China’s special urban–rural dual structure may create heterogeneity in the influence mechanism of older adults’ self-rated health. Therefore, this study constructed a mediating effect model of “material (built environment)—psychological (depression, social capital)—self-rated health” elements. The indirect effects of depression and social capital were considered in the influence path of the built environment and older adults’ self-rated health. A structural equation model was used to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) directly affect older adults’ self-rated health.

Hypothesis 2.

Depression and social capital mediate the relationship between built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) and older adults’ self-rated health.

Hypothesis 3.

Built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) are associated with depression through social capital and thereby indirectly affect older adults’ self-rated health.

Hypothesis 4.

The direct and indirect effects of built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) on older adults’ self-rated health show urban–rural heterogeneity.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

The data for this study were obtained from the open-access 2018 wave of the China Labor Force Dynamics Survey (2018 CLDS). This nationally authoritative survey was published by the Centre for Social Survey at Sun Yat-sen University. The CLDS employed a multi-stage, cluster and stratified Probability-Proportional-to-Size (PPS) sampling method to select participants covering 29 provinces and municipalities. To examine the influencing mechanism of adults’ self-rated health, males over 60 years and females over 55 years were defined as older adults based on the Seventh National Population Census [83]. After eliminating samples with missing and extreme values, a valid sample of 3685 participants was used in this study.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, self-rated health, is a subjective self-assessment of an individual’s overall health [33]. In accordance with prior studies, self-rated health is a reliable indicator of health and has been used extensively [84,85]. Participants were asked to evaluate their physical health with the following question: “How do you assess your overall health status compared to that of your peers?” We reverse-coded the question and recoded all the responses as follows: “1 = very unhealthy, 2 = unhealthy, 3 = fair, 4 = healthy, 5 = very healthy”.

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Housing quality was operationalized using four different 0-to-10 opinion scales: (1) “cleanliness”, i.e., the condition of sanitation and cleanliness (higher value, better condition); (2) “overcrowding”, i.e., the indoor overcrowding condition (higher value, less overcrowding); (3) “daylight”, i.e., the condition of the architectural daylight in dwellings (higher value, better condition); and (4) “ventilation”, i.e., the condition of the natural ventilation inside the house (higher value, better ventilation). The variables related to environmental pollution assessed air, water, noise, and soil pollution [86,87,88]. Respondents were asked to assess the pollution levels in the area where they lived, with each item ranging from 1 to 4. Lower scores indicated more severe pollution.

2.2.3. Mediator Variables

Putnam’s definition of social capital has been extensively applied in research on health [25,89,90,91,92]. According to Putnam, the value of social capital is derived from social networks and the norms and trust arising from them [93]. Therefore, in this study, social capital consisted of four aspects: social network, social trust, neighbor familiarity, and neighbor trust. Social network was assessed using a single item: “How often does mutual help occur between you and your neighbors and other residents of your community?” The response values ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Social trust was assessed using five items. The respondents were asked to assess their levels of trust in family members, neighbors, schoolmates, fellow villagers, and colleagues. The response value for each item was measured on a five-point scale (1 = very distrustful, 2 = not very trusting, 3 = general, 4 = trusting, 5 = very trusting) with total social trust scores ranging from 5 to 25. A single item was used to assess neighbor familiarity: “How well do you know your neighbors, neighborhood, and other residents in your community (village)?” The response values were scored from 1 (very unfamiliar) to 5 (very familiar). A single item was used to assess neighbor trust: “Do you trust the neighbors, neighborhoods, and other residents in your community (village)?” The response values were on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (very distrustful) to 5 (very trusting). Depression was assessed using a self-assessment scale (CES-D20) that has been extensively used to assess depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the validity and reliability of the CES-D have been shown in prior studies [94,95,96]. The CES-D contains 20 items used to measure the frequency of 20 depressive symptoms during the past week. Each item was coded on a four-point reverse scale (1 = almost always or 5–7 days, 2 = often or 3–4 days, 3 = rarely or 1–2 days, and 4 = never or <1 day). The total scores range from 20 to 80, with lower scores reflecting higher levels of depression. The cut-off score for depression is 65, which has been extensively used [97,98]. Thus, respondents scoring ≥ 65 were considered not to have depression.

2.2.4. Control Variables

Demographic characteristics were used as covariates, which included age, gender, marital status, and educational attainment. Age was a continuous variable. Gender and marital status were converted into dummy variables representing men and married individuals, respectively. Educational attainment was categorized into four options (1 = uneducated, 2 = primary school, 3 = high school, and 4 = college or above).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) refers to a combination of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis to test theoretical models consisting of latent variables [99]. SEM is extensively applied in research on public health and urban studies. It allowed us to access the effects of direct and indirect paths among different variables. This study used SEM to identify the relationship between built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution), depression, social capital, and older adults’ self-rated health and shed light on the potential influencing mechanism of older adults’ health outcomes in our study. Furthermore, the heterogeneity between urban and rural areas was analyzed using multigroup analysis.

SPSS version 26 and STATA 18 were used for basic pre-analysis, data cleaning, and descriptive statistical analysis. In line with the research purpose, AMOS 27 software was used to establish and analyze both the measurement and structural model. First, CFA was conducted to check the convergent validity of the established model, including three latent variables: housing quality, environmental pollution, and social capital. Factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were computed to assess convergent validity. Furthermore, the square root of the AVE was computed to test discriminant validity [100]. Second, a structural equation model was constructed to identify the relationships among housing quality, environmental pollution, social capital, depression, and self-rated health. Six fit indices were used to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit: the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI > 0.90), increased fit index (IFI > 0.90), normalized fit index (NFI > 0.90), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI > 0.90), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08) [93,94]. Third, 5000 bootstrapping samples with 95% bias-validated confidence intervals (CIs) were computed to evaluate the significance and strength of the indirect effects [101,102]. Finally, multigroup analysis was performed according to the type of community (urban and rural). The baseline model was an unconstrained model with all parameters estimated freely. Three constrained models were constructed in which the measurement weights, structural weights, and structural covariance were constrained to be equal across groups. Specifically, the difference in the CFI was used to evaluate the invariance because the χ2 difference test would be overly sensitive to sample size [103,104] and ΔCFI is not influenced by sample size [105,106]. If the CFI difference (ΔCFI) was less than 0.01, the construct of the model was considered reasonably invariant [106,107,108,109].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Participants

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants. Of the total sample of 3685 older adults, 1158 were from urban communities, and 2527 were from rural communities. The mean age of the participants in this study was 62.35, and the sample included more women than men. Only 3.0% of the respondents were single. The proportion of respondents with a high school degree was the highest (39.9%). In terms of self-rated health, the mean value was higher than the median, and the urban participants had a higher mean score than the rural participants. The same was true for depression.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study participants.

3.2. Measurement Model

CFA was used to evaluate goodness-of-fit. The model included three latent variables: housing quality, environmental pollution, and social capital. The results demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data: TLI = 0.9852, IFI = 0.9890, NFI = 0.9865, AGFI = 0.9809, CFI = 0.9890, and RMSEA = 0.0345. The convergent validity of the indicators were supported as all the factor loadings showed statistical significance [110]. Furthermore, the factor loadings of housing quality, environmental pollution, and social capital indicators ranged from 0.7395 to 0.9384, 0.6887 to 0.8065, and 0.2181 to 0.8405, respectively (Table 2). The CR values of the latent constructs were 0.9051, 0.8402, and 0.7220, respectively, which were greater than the threshold value of 0.7, whereas the AVE values were 0.7068, 0.5687, and 0.4272, respectively, which were all close to 0.5. The square root of the AVE was higher than all the correlation coefficients of the paths (Table 3). CFA was used to test the hypothetical structural model, and the fit parameters indicated acceptable convergent validity.

Table 2.

Convergent validity of the measurement model.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity of the measurement model.

3.3. Structural Equation Model Analysis of the Total Sample

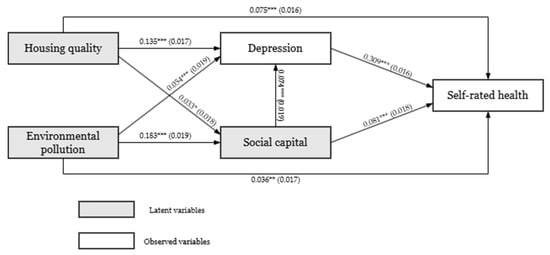

Figure 2 graphically shows the hypothesized model for the entire sample in this study, where all the standardized regression weights are presented. The fit indices were TLI = 0.9100, IFI = 0.9271, NFI = 0.9219, AGFI = 0.9376, CFI = 0.9271, and RMSEA = 0.0588, indicating an acceptable fit for the total sample. Table 4 shows the results of the structural equation model, for which housing quality and environmental pollution had significant positive direct effects on self-rated health (0.075, p < 0.01; 0.036, p < 0.05). These findings supported H1 and showed that residents who lived in good-quality housing (adequate space, daylight, cleanliness, adequate daylight, and good ventilation) and with less environmental pollution tended to have better health outcomes. Furthermore, housing quality and environmental pollution had significant positive direct effects on social capital (0.033, p < 0.1; 0.183, p < 0.01). Better housing quality and less environmental pollution were related to greater levels of social capital. Regarding depression, as expected, better housing quality, less environmental pollution, and greater social capital contributed to lower levels of depression (0.135, p < 0.01; 0.054, p < 0.01; 0.074, p < 0.01, respectively). These findings are consistent with existing studies [77,111,112,113]. In addition, depression and social capital had significant direct positive effects on self-rated health (0.309, p < 0.01; 0.081, p < 0.01). Lower levels of depression and greater social capital contributed to positive evaluations of self-rated health. Thus, depression and social capital were confirmed as important mediators of the relationship between housing quality, environmental pollution, and self-rated health.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model for the total sample. Significance * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; Model fit indices: TLI = 0.9100, IFI = 0.9271, NFI = 0.9219, AGFI = 0.9376, CFI = 0.9271, RMSEA = 0.0588.

Table 4.

Results of the structural equation model for the total, urban, and rural samples.

To test H2 and H3, the mediating effects were estimated using the maximum likelihood method through bootstrapping with 5000 resamples under 95% CIs [114]. The direct effect was statistically significant when the confidence interval excluded zero. Table 5 presents the estimated results. Housing quality can indirectly influence self-rated health through depression (Coef. = 0.041, bootstrapping CI [0.030, 0.053]). Housing quality did not indirectly influence self-rated health through social capital (Coef. = 0.002, bootstrapping CI [−0.000, 0.006]). Additionally, depression and social capital mediated the relationship between environmental pollution and self-rated health, with indirect effect coefficients of 0.016 (bootstrapping CI [0.005, 0.029]) and 0.014 (bootstrapping CI [0.008, 0.023]), respectively. Therefore, H2 was partially supported. Regarding chain-mediating effects, housing quality indirectly influenced self-rated health through the mediating roles of social capital and depression (Coef. = 0.000, bootstrapping CI [0.000, 0.002]). Similarly, environmental pollution indirectly influenced self-rated health through the mediating roles of social capital and depression (Coef. = 0.004, bootstrapping CI [0.002, 0.006]). Therefore, H3 was supported. These results revealed that social capital plays an important mediating role in the relationship between housing quality, environmental pollution, and self-rated health, which could also influence self-rated health through depression.

Table 5.

The direct, indirect, and total effects for the total sample.

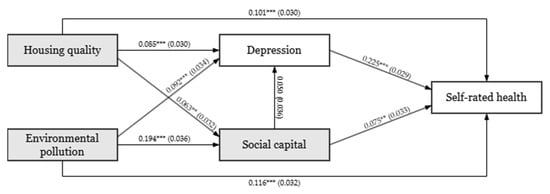

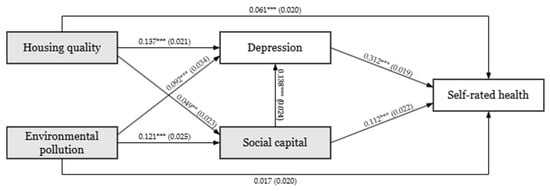

3.4. Multiple Group Analysis

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the hypothesized models for the urban and rural samples, respectively, presenting all the standardized regression weights. The fit indices were good for both the urban and rural samples (TLI = 0.9264, IFI = 0.9406, NFI = 0.9232, AGFI = 0.9388, CFI = 0.9404, RMSEA = 0.0522, and TLI = 0.9139, IFI = 0.9303, NFI = 0.9225, AGFI = 0.9414, CFI = 0.9302, RMSEA = 0.0569, respectively). A multigroup structural equation model was used to examine the stability of the model between urban and rural samples. Although the models were constrained with measurement weights, structural weights, and structural covariances, they fit the data well (Table 6). Furthermore, as shown in Table 6, the results of the chi-square test were statistically significant for the constrained models. However, the value of ΔCFI was less than 0.01. Therefore, the invariance and comparability of model constructs across the urban and rural groups were supported.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model for the urban sample. Significance, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; model fit indices: TLI = 0.9264, IFI = 0.9406, NFI = 0.9232, AGFI = 0.9388, CFI = 0.9404, RMSEA = 0.0522.

Figure 4.

Structural equation model for the rural sample. Significance, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; model fit indices: TLI = 0.9139, IFI = 0.9303, NFI = 0.9225, AGFI = 0.9414, CFI = 0.9302, RMSEA = 0.0569.

Table 6.

Invariance test of the multigroup analysis.

The multigroup structural equation model analysis (Table 7) indicated that the direct effect of environmental pollution on self-rated health was significant in the urban sample (Coef. = 0.116, bootstrapping CI [0.055, 0.181]) but not in the rural sample (Coef. = 0.017, bootstrapping CI [−0.025, 0.057]). In accordance with previous studies, the relationship between self-rated health and environmental pollution presented different results across the urban and rural groups [87]. The path from housing quality to self-rated health was positive and statistically significant for both the urban and rural groups, whereas the coefficient in the urban group was larger than that in the rural group. In addition, for the urban sample, neither housing quality nor environmental pollution showed significant indirect effects on self-rated health, mediated by depression and social capital (Coef. = 0.002, bootstrapping CI [−0.000, 0.007]; Coef. = 0.000, bootstrapping CI [−0.000, 0.003], respectively), whereas the rural sample demonstrated significant direct effects (Coef. = 0.005, bootstrapping CI [0.003, 0.008]; Coef. = 0.002, bootstrapping CI [0.000, 0.004], respectively). Therefore, H4 could be supported partially.

Table 7.

The direct, indirect, and total effects in the multigroup analysis.

4. Discussion

Over the last 30 years, rapid socioeconomic development has resulted in dramatic changes in the living environments of older adults in China. The significant influence of the built environment on self-rated health has been extensively acknowledged by the academic community. However, relatively few studies have evaluated nationally representative samples in China. Moreover, the self-rated health influence path of “material–psychological–self-rated health” elements has not been fully considered. In particular, the influence paths of housing and surrounding environmental pollution factors closely related to individual lives remain unclear. Furthermore, regional variations caused by China’s urban–rural dual structure have resulted in differing levels of quality of housing and environmental pollution between urban and rural regions, which may lead to variations in the self-rated health impact mechanisms of older adults in these regions. Nevertheless, previous researches have overlooked this possible urban–rural heterogeneity. In order to enhance our comprehension of the relationship between the built environment and older adults’ self-rated health, this study considered depression and social capital factors in the psychological pathway as mediator variables to investigate the influence of the built environment on the self-rated health of older adults. The results will be helpful for more systematic examinations of the significance of built environment factors associated with housing quality and surrounding environmental pollution on the self-rated health status of older adults and can help promote healthy aging.

4.1. Direct Impact of Built Environment Factors on Older Adults’ Self-Rated Health

The theory of health ecology emphasizes the importance of the built environment for individual health. The results of this study further support this theory. The results showed that built environment factors related to housing quality and environmental pollution can directly influence older adults’ self-rated health. Improved housing quality and decreased environmental pollution levels around housing help reduce the probability of poor self-rated health among older adults. These findings conform to the most recent evidence [12,115,116]. Notably, housing quality was not evaluated using a single standard. A series of conditions are required to jointly influence individual health status, as Cartwright et al. [117] have also acknowledged. Living in a crowded environment is likely to result in poor interpersonal relationships [68]. A well-designed lighting environment is conducive to the effective daily activities of older adults [118], as well as improving their eyesight and alleviating depression [119]. Housing with better ventilation contributes to good indoor air quality [120]. Older adults who live in clean housing environments are less likely to fall [121]. Improvement of these factors related to housing quality may help older adults perceive better self-rated health status. In particular, the decline in physiological function and increase in unemployment among older adults increases the time they spend at home [13], which significantly enhances the influence of housing quality on self-rated health.

Evidence suggests that environmental pollution in a community can cause a decline in physical activity among older adults, bringing about several physical and mental health problems [116]. Inhaling fine particulate matter from air pollution may cause systemic oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to physical health problems [122]. Higher noise pollution in neighborhood streets can also lead to negative health quality and older adults’ self-rated health [21]. Weakened mobility limits the range of activities that older adults can perform in contrast to younger individuals, and they are more prone to be active around their homes. Moreover, to respect the living habits of older adults in their long-term residence, home-based treatment aligns more closely with the deeply rooted concepts of older adults in China and is accepted by the majority [123]. Therefore, poor housing quality and higher environmental pollution are likely to harm older adults’ health.

4.2. Potential Influence Mechanism Between the Built Environment and Older Adults’ Self-Rated Health

Several complex relationships could potentially influence the influence of the built environment on the self-rated health of older adults. The results of this study offer evidence and explanations for the influence path of “material–psychological–self-rated health” elements. The mediation analysis results indicated that housing quality can indirectly improve older adults’ self-rated health by reducing depressive symptoms. Low levels of housing quality could strengthen older adults’ depressive symptoms [21,69]. Older adults living in clean, well-ventilated, spacious, and bright high-quality housing are more probable to have lower levels of depression and better self-rated health. Regarding environmental contamination around housing, as expected, improved environmental pollution was linked to a decrease in depression symptoms and enhanced social capital, which indirectly promoted older adults’ self-rated health. These findings further demonstrate the significance of the environment around housing for the health of older adults. Being exposed to high air pollution levels raises the probability of symptoms of depression in older adults [124]. At the same time, exposure to toxic air pollution negatively affects social trust [125]. Furthermore, a higher perceived level of environmental pollution may increase older adults’ willingness to remain in their houses, weaken their willingness to travel, and reduce their communication with the outside world. Air pollution can limit individuals’ face-to-face social engagement and have an impact on social capital [76]. These factors may all affect the self-rated health of older adults.

Given the prospective interwoven relationship between built environment factors and older adults’ self-rated health, this research posited that built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution) affect depression in older adults through social capital, indirectly influencing their self-rated health. Both approaches were aligned with the anticipated results. In the housing quality–social capital–depression–self-rated health pathway, housing quality was found to decrease depression in older adults through its positive impact on social capital and enhance the self-rated health of them. Previous studies have generally argued that one’s neighborhood is an important environment that promotes the development of social capital [73]. However, housing and the family environment have been found to be essential in encouraging residents to engage in informal and formal networks and social interactions. Housing environment that are well-designed and furnished are critical for both social trust and health [22]. Meanwhile, relevant factors of social capital can promote positive emotions in individuals to cope with depressive symptoms. Studies have indicated that social capital, which is relevant to trust, reciprocity, and social networks, is markedly correlated with depression in older adults. Trust and mutual benefits among older adults can generate a positive psychological state, and the emotional support obtained can alleviate depression [126]. The diversity of social networks generates positive emotions through core relationships and regulates the neuroendocrine system to reduce the risk of depression [127]. Notably, this study did not find a mediation effect of social capital on the relationship between housing quality and self-rated health among older adults. It appears from these results that reducing depression is an essential part of building social capital to improve home quality and the self-rated health of older adults.

In the environmental pollution–social capital–depression–self-rated health pathway, the results of this research indicate that decreased environmental pollution facilitates the accumulation of social capital, thereby alleviating depressive symptoms and promoting self-rated health among older adults. Low levels of social capital, for instance, poor social networks [128] and severe social isolation [129], are correlated with elevated levels of depression. Research have indicated that neighborhood social capital exerts a protective influence and can weaken the effect of air pollution on depressive symptoms [129]. Furthermore, environmental pollution around housing reduces residents’ willingness to go outside for activities [116], which affects the chances for older adults to engage with their neighbors and reduces the channels for them to obtain emotional support. This may lead to loneliness and depression among older adults and reduce their self-rated health.

4.3. Urban–Rural Heterogeneity in the Impact Mechanism of the Housing Quality and Environmental Pollution

Imbalances between urban and rural development in China have resulted in significant distinctions in the built environments of urban and rural areas. Older adults living in various regions may have different pathways of influence on self-rated health. Therefore, a heterogeneity analysis was performed. The results revealed that environmental pollution around housing in urban areas was related to older adults’ self-rated health, whereas no such relationship was found in rural areas. This is aligned with the results of former research [87]. Urban areas are more severely affected by environmental pollution, and urban residents are more aware of the health risks of environmental pollution, which may make it easier for them to associate health outcomes with environmental pollution. Rural residents have a relatively weak awareness of the health hazards caused by environmental contamination.

In this study, the multiple mediation analysis implied that the influence path of built environment factors (housing quality and environmental pollution), social capital, depression, and self-rated health for urban older adults was not significant, which was in contrast to the results for rural areas. One potential interpretation for this is the variations in the role of social capital between urban and rural areas. As rural areas have less access to formal services and have higher levels of isolation, social capital factors are of more significance in these areas [130]. In comparison to urban older adults, those in rural areas might be more deeply influenced by traditional concepts and more susceptible to the influence of social capital. Furthermore, rural areas in China are still described as a “society of acquaintances”. Relatives, friends, and neighbors are closely linked to social interactions through mutually beneficial cultural rules. Housing is a symbol of identity and status and plays an important role in rural areas. Dilapidated houses are often associated with discrimination and disgrace. Better housing is an exterior sign of success and wealth that may increase the social capital and social status of older adults [131]. As a result, for rural older adults, the positive or negative impacts of the built environment can influence social capital more extensively and jointly affect self-rated health through depression. In contrast, although the built environment also affects urban older adults’ social capital, the diverse channels for obtaining help and relatively shallow social connections in cities as alternative resources may dilute the health effects of social capital. Specifically, urban areas have superior conditions such as social security, health care, and public transportation compared to rural areas. Urban older adults have more diverse health promotion services and are more likely to obtain public service support. Urban older adults are less dependent on social contacts to obtain health care services [132]. Meanwhile, research has indicated that the social capital of urban residents is relatively low [133], and they are usually regarded as having weak social connections, insufficient levels of social support, and low social trust [134,135]. Their social networks are more dispersed and are mostly supported by friends, with relatively low familiarity with their neighbors [136]. Social ties with neighbors do not necessarily lead to closer interpersonal interactions and trust [137]. This may contribute to the limited effect of the improvement of social capital brought by the improvement of the built environment on alleviating the depression of the urban older adults, thereby making the indirect impact of housing conditions and environmental pollution on the urban older adults’ self-rated health insignificant.

There were restrictions on this study. Firstly, the data from 2018 were cross-sectional, and the temporal variations in built environment factors could not be captured. During data collection, there may have been an absence of variables or unobservable distinctions among individuals. Secondly, due to data availability issues, the measurement indicators of housing quality and environmental pollution selected for this study were limited. Other built environment indicators related to housing and pollution may not have been observed. Third, the dependent variable was self-rated health. Although it can predict objective health outcomes, it lacks the support of objective health indicators. Future research should start from a longitudinal temporal and spatial perspective to explore the influence of changes in built environment factors on older adults’ health more systematically. Furthermore, future research on housing quality and environmental pollution should incorporate a richer set of built environment indicators. Based on health indicators that combine subjectivity and objectivity, future research should analyze how the built environment affects older adults’ health through more compressive psychological approaches.

5. Conclusions

Using structural equation modeling, this study utilized the nationally representative 2018 CLDS database to conduct an analysis of the relationship between built environment factors (housing and environmental pollution) and older adults’ self-rated health, with particular attention paid to the influence of the multiple mediating effects of social capital and depression. Meanwhile, the urban–rural heterogeneity in these effects was analyzed. The results show that housing quality and environmental pollution are correlated with to older adults’ self-rated health. High-quality housing and low levels of environmental pollution help improve the self-rated health condition of older adults. Secondly, the results of the mediation analysis show that housing quality and environmental pollution can indirectly improve older adults’ self-rated health through positive effects on social capital and depression. Moreover, social capital can mediate the effect of built environment factors on older adults’ self-rated health by improving depressive symptoms. Additionally, the impact path regarding the self-rated health of older adults is heterogeneous between urban and rural areas. Rural older adults are influenced by the path of the built environment–social capital–self-rated health. However, similar results among older adults in urban areas were not observed.

The results of this research are significant for achieving healthy aging and building a healthy and livable environment. First, a high level of built environment factors can promote older adults’ self-rated health. Those formulating housing improvement policies should focus on housing quality for older adults, such as a well-ventilated, bright, and clean indoor environment. Furthermore, the problem of crowded housing must be solved from multiple perspectives, such as the availability of reasonably priced housing and housing costs. The government should formulate appropriate environmental pollution control policies and encourage the development of green technologies to reduce environmental pollution. Second, the government and residential area builders should communicate directly with older adults regarding their health and environmental needs and enhance their trust in other social entities. Reducing environmental pollution through technological innovation, emission restrictions, and green spaces will encourage older adults to take part in social engagement and promote the accumulation of social capital. Older adults should also be provided with better emotional support to alleviate their depressive symptoms. Furthermore, regional and cultural differences must be considered. The government and other relevant entities should formulate precise built environment improvement measures for older adults in both urban and rural areas to maximize environmental health benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and W.Z.; methodology, J.S. and W.Z.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S. and W.Z.; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, J.S. and W.Z.; resources, X.Z. and R.W.; data curation, J.S.; writing-original draft preparation, J.S., W.Z., X.Z. and R.W.; supervision, X.Z. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Province Natural Science Fund (Grant No. 2022A1515011728).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the absence of sensitive data and to the processing of data with the assurance of the confidentiality and anonymization of the personal information of all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the members who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2024 National Economic and Social Development; National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2025.

- China Development Research Foundation China. Development Report 2020: Trends and Policies of Population Aging in China; China Development Research Foundation China: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China Healthy China Action Plan (2019–30). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Lei, X.; Sun, X.; Strauss, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y. Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study national baseline. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission. The 14th Five-Year Plan for Healthy Ageing; National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-03/01/content_5676342.htm (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Lu, N.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J. Community social capital, family social capital, and self-rated health among older rural Chinese adults: Empirical evidence from rural northeastern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Hsu, N.-W.; Chou, P. Validation of global self-rated health and happiness measures among older people in the Yilan study, Taiwan. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, I.; Spallek, J.; Richter, M. Explaining socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health: A systematic review of the relative contribution of material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapport, D.J.; Howard, J.; Lannigan, R.; McCauley, W. Linking health and ecology in the medical curriculum. Environ. Int. 2003, 29, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.; Fossa, A.; Steiner, A.S.; Kane, J.; Levy, J.I.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Bennett-Fripp, W.M.; Reid, M. Housing quality and mental health: The association between pest infestation and depressive symptoms among public housing residents. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N.; Aydin, E. The impact of housing conditions on health outcomes. Real Estate Econ. 2021, 49, 1172–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.; Gordon, D.; Heslop, P.; Pantazis, C. Housing deprivation and health: A longitudinal analysis. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.; Platt, S.D. Housing conditions and ill health. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1987, 294, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Kim, G.; Liu, D.; Bardo, A.R. Associations between perceived environmental pollution and mental health in middle-aged and older adults in East Asia. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2021, 33, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B. Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Zhang, J. Social Capital and Self-Rated Health among Older Adults Living in Urban China: A Mediation Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Dunstan, F.D.; Fone, D.L. Neighbourhood deprivation and self-rated health: The role of perceptions of the neighbourhood and of housing problems. Health Place 2008, 14, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, K.N.; Droomers, M.; Robinson, W.R.; Carnethon, M.R.; Daviglus, M.L.; Monique Verschuren, W. Quantifying the contributions of behavioral and biological risk factors to socioeconomic disparities in coronary heart disease incidence: The MORGEN study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 28, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, N.; Filatova, S.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Miettunen, J. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: A systematic review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Lee, J.-S. Impact of residential environments on social capital and health outcomes among public rental housing residents in Seoul, South Korea. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.J.; Saman, D.M.; Lipsky, M.S.; Lutfiyya, M.N. A cross-sectional study on health differences between rural and non-rural US counties using the County Health Rankings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Os, J.; Hanssen, M.; Bijl, R.V.; Vollebergh, W. Prevalence of psychotic disorder and community level of psychotic symptoms: An urban-rural comparison. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Song, J.; Zuo, W.; Wu, R. Deciphering the Mechanism of Women’s Mental Health: A Perspective of Urban–Rural Differences. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-L. Organizing Through Division and Exclusion: China’s Hukou System; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-8047-6748-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.; Kaplan, G. What Does Self Rated Mental Health Represent. J. Public Health Res. 2014, 3, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, A.; Bosma, H.; Grabauskas, V.; Gostautas, A.; Sturmans, F. Self-rated health and mortality in a Lithuanian and a Dutch population. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 42, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, E.L.; Angel, R.J. Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am. J. Public Health 1990, 80, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamins, M.R.; Hummer, R.A.; Eberstein, I.W.; Nam, C.B. Self-reported health and adult mortality risk: An analysis of cause-specific mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambler, G. Health inequalities. Sociol. Health Illn. 2012, 34, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, F.; Molarius, A.; Garvin, P.; Elo, S.; Feldman, I.; Kristenson, M. Exploring trends in and determinants of educational inequalities in self-rated health. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.W.; Smith, G.D.; Kaplan, G.A.; House, J.S. Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 2000, 320, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.E.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Siegrist, J. Housing and health in Germany. J. Community Health 2004, 58, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Ge, S.; Du, B. 1 km of living area: Age differences in the association between neighborhood environment perception and self-rated health among Chinese people. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Stephens, M.; Liu, Y. Long working hours and self-rated health: Evidence from Beijing, China. Cities 2019, 95, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Ma, X.; Lin, L.; Qin, X.; Guo, D.; Jin, X.; Tian, L. The association of harsh working environment and poor behavior habits with neck health. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2023, 97, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaco, R.W.; Collier, C. Commuting Stress, Ridesharing, and Gender: Analyses from the 1993 State of the Commute Study in Southern California; University of California, Irvine: Irvine, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Novaco, R.W.; Stokols, D.; Milanesi, L. Objective and Subjective Dimensions of Travel Impedance as Determinants of Commuting Stress; University of California, Irvine: Irvine, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Bos, V.; Andersen, O.; Cardano, M.; Costa, G.; Harding, S.; Reid, A.; Hemström, Ö.; Valkonen, T.; Kunst, A.E. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in six Western European countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 32, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.; Rachet, B.; Woods, L.; Mitry, E.; Riga, M.; Cooper, N.; Quinn, M.; Brenner, H.; Estève, J. Trends and socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England and Wales Up to 2001. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spuling, S.M.; Wurm, S.; Tesch-Römer, C.; Huxhold, O. Changing predictors of self-rated health: Disentangling age and cohort effects. Psychol. Aging 2015, 30, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.Y. Acculturative stress and self-rated mental health among Asian immigrants: Mediation role of social support. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2024, 30, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Nanetti, R.Y.; Leonardi, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M. Social capital and health—Implications for health promotion. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoom, M.R. Social capital and health beliefs: Exploring the effect of bridging and bonding social capital on health locus of control among women in Dhaka. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinsky, F.D.; Tierney, W.M. Self-rated health and adverse health outcomes: An exploration and refinement of the trajectory hypothesis. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1998, 53, S336–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, J.C.; Schoenfeld, D.E.; Blazer, D.G. Determinants of poor self-rated health in late life. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1996, 4, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisher, M.; Mendonça, M.; Shelton, N.; Pikhart, H.; de Oliveira, C.; Holdsworth, C. Is alcohol consumption in older adults associated with poor self-rated health? Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, J.; Guan, C. Diet and self-rated health among oldest-old Chinese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 76, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Cross-lagged associations between physical activity, self-rated health, and psychological resilience among older American adults: A 3-wave study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2023, 20, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; Discussion paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F. Measuring Physical Activity Environments. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S86–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Basic Information About the Built Environment. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/smm/basic-information-about-built-environment (accessed on 13 May 2025).[Green Version]

- Molinsky, J.; Forsyth, A. Housing, the built environment, and the good life. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2018, 48, S50–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, C.B.; Hernández, D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 243, 112571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M.; Gershenson, C. Housing and employment insecurity among the working poor. Soc. Probl. 2016, 63, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhuang, X. Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being. Buildings 2024, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed-Ochir, O.; Ikaga, T.; Ando, S.; Ishimaru, T.; Kubo, T.; Murakami, S.; Fujino, Y. Effect of housing condition on quality of life. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A. Housing conditions and health: New evidence from urban China. Cities 2024, 152, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Smith, J.C.; Popkin, B.M. Understanding community context and adult health changes in China: Development of an urbanicity scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifin, E.N.; Hoon, C.-Y.; Slesman, L.; Tan, A. Self-rated health and perceived environmental quality in Brunei Darussalam: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, I.; Zhang, S.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Osborn, D.P.; Hayes, J.F. Air pollution (particulate matter) exposure and associations with depression, anxiety, bipolar, psychosis and suicide risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 126002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M. Housing and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 25, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, C.; Lai, K.Y.; Kumari, S.; Leung, G.M.; Webster, C.; Ni, M.Y. Characteristics of the Residential Environment and Their Association With Depression in Hong Kong. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2130777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wu, S.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, N. Association of residential environment with depression and anxiety symptoms among older adults in China: A cross-sectional population-based study. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Kundu, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Rao, S. Indoor air pollution and cognitive function among older adults in India: A multiple mediation approach through depression and sleep disorders. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Learnihan, V.; Cochrane, T.; Davey, R. The Built Environment and Social Capital: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Lin, J.; Yin, C. Impacts of the built environment on social capital in China: Mediating effects of commuting time and perceived neighborhood safety. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, A.; Frumkin, H.; Jackson, R. Making Healthy Places: A Built Environment for Health. In Traffic Calming Device Painted Pedestrian Crossin g Basketball Court Playground Bus Stop Rubbish Bins Postbox Surveillance Cameras; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ditkovsky, O.; Van Vliet, W. Housing tenure and community participation. Ekistics 1984, 51, 345–348. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A. Neighbourhood cohesion and health in socially contrasting neighbourhoods: Implications for the social exclusion and public health agendas. Health Bull.-Scott. Off. Dep. Health 2000, 58, 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.-Z.; Li, L.; Song, Y.-F.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Shen, S.-Q.; Ou, C.-Q. The impact of ambient air pollution on suicide mortality: A case-crossover study in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Xue, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, H. The Relationship between Air Pollution and Depression in China: Is Neighbourhood Social Capital Protective? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Ma, J. Urban-Rural Disparity in the Relationship Between Geographic Environment and the Health of the Elderly. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2024, 17, 1335–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboz, P.; Boetsch, G.; Gueye, L.; Macia, E. Self-rated health in Senegal: A comparison between urban and rural areas. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Sun, S.; Chen, T.; Pan, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H. Impacts of Social Inequality, Air Pollution, Rural–Urban Divides, and Insufficient Green Space on Residents’ Health in China: Insight from Chinese General Social Survey Data Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Yang, J.; Ke, X. The impact of neighborhood environment on the mental health: Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1452744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, J. Differences in Housing Conditions between Urban and Rural Households and the Influencing Factors in China. Sci. Decis. Mak. 2024, 11, 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J. Main data of the seventh national population census. China Stat. 2021, 5, 4–5. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817185.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Chen, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G. Social Change and Socioeconomic Disparities in Health over the Life Course in China: A Cohort Analysis. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 126–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I. Commentary: Reconciling the three accounts of social capital. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Chen, N.; Liang, H.; Gao, X. The Effect of Built Environment on Physical Health and Mental Health of Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. Association between perceived environmental pollution and health among urban and rural residents-a Chinese national study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, C.; Hughes, R.M.; Davis, W.S. China’s new environmental protection regulatory regime: Effects and gaps. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 187, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlier, M.; Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Babiak, K.; Willem, A. Interrelation of Sport Participation, Physical Activity, Social Capital and Mental Health in Disadvantaged Communities: A SEM-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Lu, N. Community-based cognitive social capital and self-rated health among older Chinese adults: The moderating effects of education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Social integration as mediator and age as moderator in social capital affecting mental health of internal migrant workers: A multi-group structural equation modeling approach. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 865061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderblom, D. The limits to bridging social capital: Power, social context and the theory of Robert Putnam. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 66, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling Alone|Proceedings of the 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/358916.361990 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yang, F. Accompanying your children: Living without parents at different stages of pre-adulthood and individual physical and mental health in adulthood. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 992539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]