1. Introduction

In 2018, in a landmark reform initiative that aimed to fundamentally change how procurement and purchasing decisions were made in connection with major infrastructure investments, the Government of the Australian State of Victoria introduced an innovative Social Procurement Framework. The Framework aimed to create social value and achieve significant cultural change by capitalising on what was said to be the “once-in-a-generation opportunity” of the State’s “Big Build”, a term which referred to a plan for investment of more than AUD 100 billion in transport and civic infrastructure projects by Federal and State governments over the subsequent twenty years [

1].

Procurement by the Victorian Government had become one of the largest drivers of economic activity in the State of Victoria. In 2022, annual State Government infrastructure investment was projected to average AUD 21.3 billion per year over the 2022–23 budget year and subsequent years to deliver the Government’s announced capital investment pipeline [

2].

The scheme of the Social Procurement Framework required buyers such as government authorities and “Tier-One/Tier-Two” construction companies to use their purchasing power to deliver social and sustainable outcomes by ensuring that value-for-money calculations were not limited to the transactional price of the goods and services procured. The aim of the Framework was said to be to address the past lack of participation in major projects, as well as high unemployment rates, among Indigenous and immigrant communities and other disadvantaged groups at a time when annual government spending in the Victorian economy amounted to billions of dollars in the construction industry alone [

2]. The Government’s framework targeted outcomes for priority groups: Aboriginal Victorians, Victorians with disabilities, and ”disadvantaged” Victorians, a category which includes disengaged youth, long-term unemployed people, migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, single parents, and workers in transition [

3].

The term social procurement refers to the

ability of governments, corporations, and not-for-profits to leverage their purchasing power to deliver value above and beyond the goods and services they are seeking to purchase. It differs from traditional procurement in that it uses the acquisition of products and services to create social value in local communities, which exceeds the economic contribution represented by their basic purchase [

4,

5]. This value can be achieved by facilitating employment, creating meaningful economic opportunities, contributing to environmental sustainability and ethical supply chain management, and increasing diversity in the procurement supply chain [

6]. According to an alternative definition, the term refers to the

acquisition of a range of assets and services, with the aim of intentionally creating social outcomes, both directly and indirectly [

7]. The Victorian Government has defined social procurement as occurring “

when organisations use their buying power to generate social value above and beyond the value of the goods, services, or construction being procured” [

8].

Social procurement in construction projects can take various forms; however, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

9] states, there are two principal ways in which it is typically accomplished: by encouraging the large-scale production and consumption of environmentally and socially conscious goods, services, and works, and by creating employment opportunities for job seekers experiencing disadvantages.

Social value-creating policies such as those embodied in Victoria’s Social Procurement Framework have an idealistic aim: to distribute the value associated with large-scale infrastructure expenditures in different patterns, delivering benefits for particular communities such as local employment, economic inclusion, and the stimulation of local economies [

1]. This is argued to distribute benefits more equitably than in preceding decades, where the economic value created by government investment in infrastructure tended to be concentrated into the balance sheets of large corporations. Social procurement is a potential lever by which social justice-minded governments can deploy their planned infrastructure investment to achieve positive social value outcomes.

Advocates of social procurement contend that social procurement converges social and economic policy objectives in a new assemblage that prioritises social outcomes as critical to infrastructure provision, not just as tacked-on, nice-to-have policy concerns. This promises a new articulation of value in the marketplace, seeking to leverage government and private spending as a force multiplier for positive social and environmental change. The benefits anticipated range from increased value for money and greater employability of historically disadvantaged groups to the promotion of the social benefit supplier ecosystem [

10]. In launching its new framework, the Government “sermonised” about the social importance of delivering these benefits.

Loosemore [

11] described the long lineage of social procurement practices but, in its current incarnation, this form of procurement—propelled by government-driven systems which encourage it—is a relatively new and largely unproven phenomenon. In Victoria, considerable effort has been expended, in a principled manner and within a relatively short period of time, to fundamentally revamp the systems of public sector procurement. The apportionment of work that forms part of the State’s massive spending on transportation and construction infrastructure has given rise to significant new areas of contractual activity. The Government’s own announcements state that Victoria is currently in a transport construction boom, with a AUS 90 billion investment delivering over 165 major road and rail projects across the State. It has been anticipated that, over the course of the “Big Build” programme, there will be expenditure on social procurement of AUS 1.8 to 2.7 billion. This dollar range can be arrived at by the expedient of applying the Government’s “2–3% of overall expenditure” benchmark [

12]. Viewed from an international perspective, the level of ambition and sheer scale of Victoria’s social procurement experiment is breathtaking. There is significant potential for social procurement to achieve meaningful outcomes around the world.

As Lou et al. [

13] pointed out in their systematic literature review on social procurement, most of the existing research in this area tends to be descriptive in nature instead of focusing on theoretical development, citing a lack of conceptualisation and theoretical investigation. They add that the main theories typically employed in social procurement are new institutional theory and organisational theory, which focus on social value and social impact. Their review identified the need for investigations to measure the real-world impacts of social procurement policies and the gains delivered, along with a call for more research into regulatory frameworks as there is, as yet, no international social procurement regulatory scheme that could be regarded as “best practice”. To address these gaps, this paper reviews the social procurement regulatory system by employing Sheehy and Feaver’s [

14] grounded theory framework, which focuses on regulatory system coherence.

Thus, whilst a number of studies undertaken in recent years have examined the local impacts of social procurement in Victoria, (e.g., [

15,

16]), no study, to date, has questioned the efficacy of the State’s regulatory system by assessing its coherence. This is a significant omission as poorly designed policies can lead, over time, to negative social impacts and result in perverse market conduct such as tokenistic actions, community resentment, or unethical behaviors [

17].

Lou et al. [

13] and Natoli et al. [

18] have expressed concern that social procurement’s potential to contribute to enhanced social value creation has been under-theorised, and that the lens of theory could be better applied in future analysis of social procurement. This study seeks to follow through on those insights by applying grounded theory to the issues under study here.

This article makes three contributions. First, it surfaces and investigates concerns regarding the efficacy of the regulatory regime that applied from 2018 to 2022, as conveyed by key stakeholders. The deficiencies they pinpointed highlight some gaps and incoherence in the design of Victoria’s regulatory regime. Second, this study offers ideas as to how that regulatory regime might be strengthened. Third, by drawing on pertinent theoretical perspectives, particularly Sheehy and Feaver’s theory of regulatory coherence, this paper extends the debate on aspects of regulatory coherence, especially relating to decentered and distributed structural configurations.

The article is divided into eight sections, beginning with this Introduction.

Section 2 outlines the research methods deployed in our study. In

Section 3, we briefly explain the dimensions of regulatory coherence delineated by Sheehy and Feaver.

Section 4 describes the mechanisms contained within the Victorian Social Procurement Framework under study, covering its legislative and contractual facets.

Section 5 then summarises the stakeholder perspectives on aspects of regulation that we encountered during our research project.

Section 6 discusses our key findings, while

Section 7 highlights some limitations of our study. Finally, in

Section 8, we offer concluding remarks and recommendations, detailing their practical and theoretical implications.

3. The Dimensions of Regulatory Coherence: Structural, Governance, and Operational

To appreciate and interpret the essence of the concerns expressed by stakeholders regarding the efficacy of Victoria’s system of regulation of social procurement, it is necessary to understand the notion of regulatory coherence. It is useful to utilise an analytical framework that can help articulate the attributes of a particular system of regulation in a mechanistic way, focusing on actors in that system and their behaviours.

Sheehy and Feaver’s theoretical framework posited that a regulatory regime consists of both “normative” and “positive” dimensions. The normative dimension is directed towards addressing the question of how to respond to the social effects of some social issue or problem, which they termed an “organising problem”, encapsulated in the plaintive cry “something should be done about X” [

14] (p. 401).

The selection of a particular regulatory approach as a response to a social issue requires a series of normative policy choices: it must be acknowledged that an organising problem exists, a decision must be made to resolve that problem, and the measures to be put in place to address it need to be chosen [

19] (p. 962). Thus, the normative dimension of regulation consists of four components: “the perception of the organising problem, the characterisation of the organising problem, policy framing and the choice of approach” [

14] (p. 401).

A regulatory system’s positive dimension, on the other hand, is directed towards operationalising methods of addressing the behavioural interactions of social players (which Sheehy and Feaver termed “social practices”) in a way that generates a desired social effect—the normative objective as per

Figure 2 below [

19] (p. 993). Our concern in developing this paper has been to assess the coherence of the regulatory regime under study, including its legal architecture. This pertains to Sheehy and Feaver’s positive axis.

Sheehy and Feaver conceptualised the positive architecture of a regulatory system as having three levels of order (structural, governance, and operational), each comprised of two components. The structural dimension sets out relationships between actors including power dynamics and consists of “control” and “accountability” components. The governance level specifies the legal content of relationships connecting actors and comprises “substantive” and “powers and functions” components. At the operational level, there are “compliance” and “enforcement” components. In practice, the components that effect changes in actor behaviour tend to be found at the operational level [

19] (p. 965).

The premise of Sheehy and Feaver was that regulation is likely to fail when the linkages between the components of a regulatory system are incoherently aligned: “aligning a change in social practice with the operational aspects of a regulatory system requires coherence between the selected method of altering a social practice and the psychological levers and legal devices employed to effect the change” [

19] (p. 994). They noted that scholarship regarding the articulation of good design principles for regulation had not, as of 2015, moved much beyond a high-level principle set out in 1984, i.e., that “policymakers should endeavour to coherently match the method of achieving the objective of the regulation to the problem it is intended to solve” [

14,

25] (p. 408), and that, apart from the work of Black [

26], the new methods of regulation that had emerged remained relatively untested with regard to their effectiveness over the long term [

14] (p. 420). These observations have ongoing validity.

The shaping of a regulatory response requires policymakers to determine whether the organising problem is a social coordination problem (a social issue), a collective action problem (a risk), or some sort of social enabler (an opportunity). Characterisation of an organising problem occurs through the public discourse inherent in political processes; thus, policymaking is not confined to addressing harm and perceived undesirable social effects. Opportunities can also be grasped.

The Victorian social procurement regulatory regime that applied from 2018 to 2022 was an example of what Sheehy and Feaver termed a “social opportunity enabler”, occurring when a State grants a “privilege, permission, incentive or licence, usually regulated by contract, as a means of facilitating and coordinating the production, distribution and consumption of a public or private good to further a broader social policy objective” [

14] (p. 408). In general, when the state seeks to act as an “opportunity-enabler” by sanctioning specified social practices, where its change objective is to encourage specific groups to begin engaging in those social practices, it creates wealth-capture opportunities for private sector players [

14] (pp. 407, 421–422).

3.1. Structure and the Role of the Regulator: Control and Accountability

Social practices are formed by institutional arrangements, both formal and informal, and “other psychological phenomena that influence how actors think and interact” [

19,

27] (p. 966). These elements can influence the behaviour of social actors, potentially driving the desired alterations in social practices.

There are, according to theory, five distinct ways by which social practices may be altered or encouraged by regulation: mandating, prohibiting, modifying, guiding, and disciplining [

19] (p. 965). Policymakers make choices about which of these different ways of adjusting social practices to embed inside the positive legal architecture of a regulatory system.

Certain social practices are amenable to traditional command-and-control models. Although such models can be criticised as punitive and rigid, they are well suited to circumstances where an organising problem is either highly complex or so “ubiquitous, salient and urgent” that behaviours need to be mandated or prohibited and social actors need to be commanded to do something specific. Criminal penalties under occupational health and safety laws that are universally applicable to all businesses are an example of a situation where prohibition is warranted, given that death or serious injury may result from non-compliance. A further illustration of this point can be seen in the way climate change has increasingly come to be viewed in modern society as warranting immediate commanded action as a political choice [

19] (pp. 961, 989).

In other circumstances, instead of mandating completely different practices, attempts at modifying prevailing social practices may be judged appropriate. This may result in approaches that set behavioural standards, where a legislator enacts general obligations while allowing a regulator to prescribe additional, more specific obligations. This kind of approach was utilised during the early stages of the environmental regulation of corporations [

19] (p. 991).

There are also a range of potential approaches which focus, instead, on guiding and disciplining conduct. Over recent decades, a range of innovative, more flexible forms of regulation and ways of addressing social problems have emerged as alternatives to traditional approaches: co-regulation, which might encompass economic operators, social partners, and NGOs [

28]; management-based regulation; and industry self-regulation, sometimes called meta-regulation [

29]. Other approaches seek to use persuasion or inducement to encourage compliance. These newer approaches tend to be less prescriptive and less operationally rigorous than traditional command-and-control or risk-based methods. Some recent models of public regulation have been characterised by the delegation of control powers not only to regulators but also to regulatees, who can be permitted to devise “their own standards, procedures and evaluative mechanisms” [

30].

3.2. Governance: Delegation of Powers and Functions

The governance level of a regulatory system specifies the content of the legal relationships linking the actors within the system. In Sheehy and Feaver’s conception, there are two interdependent components. First, the substantive component—the “actual body of rules that govern and can change the conduct of a regulatee” [

19] (pp. 965, 974–975). Social practices are strongly influenced by formal and informal institutional settings and also by psychological factors that affect the ways actors interact and think [

27] (Elder-Vass, 2008).

Second, there is the powers and functions component by which a regulator is empowered. The term “legal governance power” describes “the legal authority to make decisions, and to create rules” [

19] (p. 975).

Sheehy and Feaver observed that it is increasingly common for the relationship between a regulator’s functions and powers to be inadequately articulated in statutes, with ambiguity around the boundary of the regulator’s authority. They outlined, in a series of tables and figures, some options for mapping powers to be delegated to regulators under various structural configurations. How an organising problem is characterised, the juridical relations put in place, and the type of rules created need to correlate with one another. The degree of centralisation of control power is a key factor in designing accountability relationships; if a decentralised model of regulation is deployed and a variety of different actors have to exercise control powers, this creates complexity in holding multiple actors accountable [

19] (p. 971).

3.3. The Operational Dimension: Compliance and Enforcement

At the operational level, key elements that can affect the behavior of actors and have the potential to create alterations in social practices are compliance and enforcement [

31] (Heyes, 1998). These are highly visible aspects of any system of regulation. Compliance is the responsibility of the regulatee, whereas enforcement is the responsibility of the regulator, and successful regulation depends on coherence between the levers and devices selected to achieve the desired social effect [

19] (pp. 983–985).

If well designed, compliance should have the effect of motivating social practices that conform to the behaviours a statute seeks to encourage on the part of regulatees. It will do this via a combination of rewards and punishments, in recognition that human behaviour is both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated. Intrinsic motivators “appeal to a person’s internal desire to engage in a social practice”—including the human need to seek acknowledgement—and can be triggered by the promise of “reward for good behaviour” or “opportunities that lead to social acknowledgements” [

19] (p. 984). In appropriate cases, “principles-based” regulation can be employed to guide behaviour.

Extrinsically, actors are highly likely to be responsive to threats that cause fear. Therefore, the legal tools employed in compliance include devices such as prison sentences, fines, taxes, and audits, as well as positive aspects such as licences and subsidies. Where fear is the chosen lever, legal devices will generally command a specific change in behaviour. Social institutions such as markets and the media can also be effective in disciplining behaviour. Standards-based regulation (which may provide for inspections or audits and is typically directed towards modifying behaviour) similarly tends to rely on anxiety.

Enforcement is a function performed by a regulator in response to compliance or non-compliance. Effective enforcement improves compliance. The administration of enforcement is the act of determining compliance and allocating consequences amongst regulatees—either rewarding those who comply or punishing those whose social practices fall outside of the parameters of the social practice that is the objective of the regulation. Actions may be taken to encourage or force regulatees to comply (or to punish them for past non-compliance) with a view to avoiding future non-compliance. The tools of government (authority, treasure, and organisation) are available to enable the deployment of psychological levers (fear, anxiety, persuasion, and incentive) to deliver the prioritised, desired behavioural outcomes [

19] (pp. 983, 988–989).

Sheehy and Feaver observed that when governments choose particular devices as their means of operationalising desired changes in social practices, the choice should be based on “clear understanding of psychology and the relationship psychology has to the human behaviour underlying compliance” [

19] (p. 987).

4. Victoria’s System of Social Procurement Regulation

The new system for regulating social procurement that the Victorian State Government put in place in 2018, as it pertained to construction sector activity, had three distinctive features. First, the State Government placed obligations on its own bureaucracy to participate in social procurement. Second, the provisions of the Local Jobs First Act 2003 (hereinafter referred to as the LJF Act) and its associated “Social Procurement Framework” and “Victorian Industry Participation Policy” documents were applied to organisations competing for Government projects. These key documents were supported by an array of general instruments that already applied to agencies of the State Government when undertaking purchasing and procurement activity in the field of construction. These were summarised on a Victorian Government website [

8]. Third, a range of commercial contracting practices were deployed to advance the Government’s social procurement agenda.

The LJF Act (previously titled, from 2003 to 2018, the Victorian Industry Participation Policy Act 2003) required all State Government departments and agencies subject to the Financial Management Act 1994, to report on their implementation of a “Local Jobs First Policy”, in two ways. First, a detailed report on Local Jobs First implementation was required as part of departments’ and agencies’ annual reporting arrangements. Second, there was a requirement for a consolidated report to responsible Ministers to enable the Ministers to report annually to Parliament on the outcomes of Local Jobs First across government [

32,

33,

34,

35] (s 1.1, p. 8).

The SPF applied to all Victorian Government departments and agencies whenever they procured goods, services and construction at certain threshold conditions [

36]. Each Victorian Department and agency was additionally required to prepare a “Social Procurement Strategy” covering planning, stakeholder communication, supplier communication/education, and measurement and reporting. Internally, within the Government, reporting was required for individual contracts at the department and agency level.

The Social Procurement Framework was designed to operate in conjunction with the State Government’s “Local Jobs First” policy, administered by the office of the Local Jobs First Commissioner. This Commissioner role was established by amendments to the LJF Act introduced in 2018, which changed some key administrative arrangements under the Act. The responsibilities of this office were diverse, including a “Major Projects Skills Guarantee” focus relating to the training of apprentices, trainees, and cadets working on large scale government projects. The majority of the Commissioner’s prescribed functions were collaborative and advisory to promote the Local Jobs First Policy across agencies and local industries, to work with agencies to improve industry access to opportunities, to advocate for local procurement, to build skills development, and to advise on Government procurement policies and initiatives (sections 18 (a), (c), (d), (e), and (f)).

The Social Procurement Framework addressed a range of separate and complementary Victorian Government mandates and laws. This included the “Tharamba Bugheen: Victorian Aboriginal Business Strategy 2017–2021” through which the Government endorsed a 1% whole-of-the-Victorian-Government procurement target to access services from Victorian Aboriginal businesses. The aim of the target was to use government procurement to increase opportunities for Victorian Aboriginal businesses, Traditional Owner Group entities, and Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations to participate in the economy.

Potentially punitive functions were also introduced into sections 18 (h) and (i) of the LJF Act in 2018 to monitor and report on compliance with the Policy and Development Plans and to take enforcement action in relation to breaches of the Policy and Plans. Associated with the latter set of functions were nominal powers to request information from agencies, to issue compliance notices, and to recommend to agencies that they seek injunctions or take other enforcement actions (sections 24, 26, and 30 of the LJF Act).

There was perceived to be a need for an entity capable of supporting the Department of Jobs, Precincts, and Regions with the implementation of Local Jobs First in a way which “assists Victorian Government departments, agencies and businesses to comply with the conditions of the Policy”. This led to the creation under statute, in 2018, of the Industry Capability Network (ICN), a not-for-profit organisation tasked with “providing support to businesses to complete their Local Industry Development Plans” (s 2.3 at p 12).

The Local Jobs First Policy had mandatory elements in that it required all Victorian Government departments and agencies, as well as contractors engaged in projects that fell within the scope of the policy, to encourage participation by local small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in infrastructure projects.

It can be seen that to the extent that they were required by legislation at all, the most significant of the legislative provisions regulating social procurement in Victoria were situated not in a piece of legislation focused on social procurement but in an Act primarily focused on the maximisation of local industry participation in development projects undertaken or funded by the State—the LJF Act. The purposes of that Act, as set out in its section 1, included providing for the development and implementation of a Local Jobs First Policy, attending to “compliance with and enforcement of the Local Jobs First Policy and Local Industry Development Plans”, and conferring functions on a Local Jobs First Commissioner. In its section 5, the Act required attention to be paid to an overarching objective of promoting employment and business growth by expanding market opportunities for local industry.

The design of Victoria’s social procurement regime announced in 2018 stopped short of delegating powers to make technical standards and other technical rules to the Local Jobs First Commissioner. One way in which incoherent delegation of powers can occur, identified by Sheehy and Feaver, is under-delegation, which can result in anaemic regulatory bodies and weak regulatory efficiency [

19,

37] (p. 981).

As a practical matter, the most influential mechanisms for the Victorian Government to advance its social procurement goals lie not in its legislation but in the content of a range of agreements Government agencies enter into with commercial entities. These include Franchise Agreements and Grant Agreements and therefore involve a more market-led approach.

It is possible to discern the nature of the content of agreements the Victorian Government has entered into from publicly available “Request for Tender” documents issued by agencies such as the Department of Transport. An illustration of the Victorian Government’s contracting processes can be seen in its “Invitation for Expression of Interest—Melbourne Bus Franchise”, issued in early 2021. This stated that one of the evaluation criteria for bidders would be the “Ability to further the social procurement goals of the Victorian Government.” Respondents were required to outline their approach to priority job seekers, gender equality, social benefit suppliers, Aboriginal businesses, sustainability, and reporting. It was proposed that any Franchise Agreement entered into would incorporate a reporting obligation requiring contracting parties to gather data and report on their progress made towards specified social procurement goals, and the social benefit supplier obligation would require contracting parties to track and record their approach to procuring non-labour goods and services from Victorian social enterprises and disability enterprises.

It is unclear what assessment weightings were given to responses to these criteria relative to hard financial metrics or responses to other prescribed “returnables” such as capability in managing industrial relations, workforce planning, change management, expertise in managing fleets, and depots management expertise.

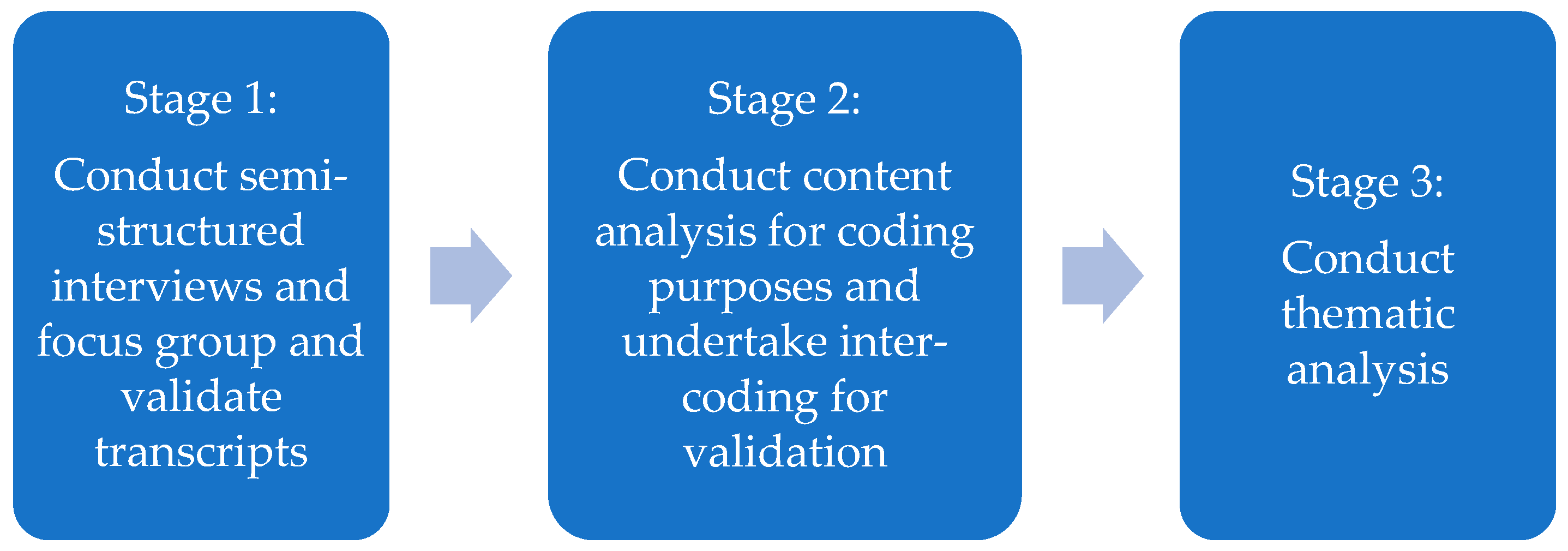

5. Stakeholder Perspectives

A feature of the research project that underpins this article was consultation with key stakeholders in the social procurement ecosystem relating to Victoria’s transport and construction industries, with the aim of pinpointing the barriers preventing the effective implementation of social procurement. During the semi-structured interviews that took place as part of our study, stakeholders suggested a need for enhancements to the Victorian regulatory system to support the more effective implementation of social procurement. A number of criticisms were made of the existing regime. These concerns have not previously been outlined in the academic literature.

The interviewees agreed that the overwhelming driver of the uplift in social procurement occurring in Victoria over recent years was its mandatory requirement in procurement contracts. This had buttressed the expansion and standardisation of social procurement practice across government procurement activities: “there would certainly not be as many opportunities if it wasn’t for government initiatives to mandate the use of social enterprise” [P3].

Some viewed social procurement as a means to transform corporate social responsibility into a core business activity delivering real social outcomes:

“social procurement has existed for a long time, but it only really gets weighed when there is a mandate or some sort of requirement around people looking at it … Corporate social responsibility, where there is no policy mandate, is a key example of an ineffective use of social and sustainable principles … without much social value really being brought back to the community”

[P10].

Some interviewees perceived the voluntary nature of social procurement mandates emanating from the State Government as creating a risk of private sector contractors not achieving the commitments they expressed at the point of tendering for contract:

“Everyone promises the world to win a contract. And some people who have never done a social procurement in their life are talking about 10% [of procurement spend] outcomes that they’ll deliver through a contract. And then you’ll get someone who’s done it many times before and have a deep track record and they’ll say, we’ll get you a 4% outcome. And quite often, the person who says 10% wins that contract, and you kind of go, you’ve got the wrong metrics in place, because they will never deliver on that 10%. So you won’t get the social outcome that you were hoping for”

[P2].

Accordingly, some participants favoured a more prescriptive and contractual obligation-based regulatory approach:

“What we’ve found is that some people haven’t translated things into the contract … there’s no schedule to say what they’ve actually committed to. So that’s why we (State Government) need to work with as many Government buyers as we can, internally, to make sure that … making a commitment in the tender process translates through to being in a contract”

[P36].

With social procurement becoming an increasingly important feature of government projects, there was a growing anticipation of commercial gain from engaging in social procurement practices, with participants experiencing increased business activity and resultant commercial outcomes, including opportunities to scale social outcomes: “the competitive nature of many industries means that, if the competitors are doing it, they’ll look to do it too” [P24].

Both social benefit suppliers and Tier-One firms anticipated reputational and employer-of-choice gains from involvement in social procurement: “they’re [the next generation of workers] looking for companies that actually do broader things, have a legacy and actually bring some value to it” [P26]. Potentially, this could translate into building a positive corporate brand image (helpful in appeasing stakeholder pressures). This could be achieved without spending money on advertising, attracting better-suited employees, and also creating the potential for those deciding to join the industry to leave a meaningful legacy.

Many interviewees had a strong impression of the sporadic enforcement of mandates and an absence of consequences for those objectively judged to have failed to meet commitments. A number of well-informed interviewees gave great weight to the positive effects of compliance behaviour. One interviewee [P22] described the regulatory environment as “the true key driver”, observing that “the policy environment plays a really key role to push people and motivate people to overcome … barriers”. Another [P23] observed that “your tier-two, -three, and -fours … have no other reason to do social procurement apart from that it is a compliance issue”.

It was seen that contractors who had expressed targets but not met them could escape sanctions: “We (State Government) don’t stipulate what that (penalty for non-compliance) is because each agency and department will have its own appetite, in terms of what they are wanting to put into a contract for breach” [P36]. This was part of a general concern about a lack of a compliance culture in connection with social procurement:

“There is not a lot of importance post contract to ensure that the contractors are actually meeting everything that’s in their tenders … when they have to cut X% on negotiation of their project, it’s the social procurement that’s cut … if it’s not actually followed up post tender to make sure that they are meeting those obligations, then we’re still going to keep going round and round in circles”

[P23].

Low levels of internal monitoring were seen as inhibiting social procurement reporting and measurement and the ability to capture the full impact of social procurement on communities, a problem compounded by a lack of standardisation in reporting and data quality issues. Interviewees were concerned about the absence of external monitoring and financial penalties for non-compliance with commitments, which some stakeholders thought gave rise to a pressing need for a thorough audit process.

Aspects of these concerns related to incentives (referred to by some interviewees as “carrots”) and penalties (“sticks”). Many of the participants in social procurement who were interviewed considered that accountability for delivering social procurement outcomes needed to be built-in as a distinctive feature of Victoria’s system:

“The monitoring has to be ongoing … so when they start to see it’s going off track midway, you can put in the plans before the end of the contract (but) it has to start at the tender and has to be monitored all the way and then reported at the end to say tick, yes, they actually achieved what they thought they would, or no, they didn’t deliver the social value they intended and these are the reasons why. This is essential to improving over time and creating better outcomes in the future”

[P20].

There was seen to be an absence of centrally maintained auditable records and publicly available data. One representative of a state Government agency [P10] said “we [the Agency] do have a reporting solution. But at the moment I would say our data quality is quite poor so it’s a work in progress.” This concern essentially reflected the absence of an agency specifically tasked with carrying out monitoring oversight and a communications function.

A heightened level of policy-making sophistication and capability was seen to be required at the Government level. For example, one interviewee said: “From a policy and a leadership perspective there could be a little bit more on the how to, just … some guideline type principles” [P24]. This extended to the provision of guidance on conformity to Government expectations:

“Okay, this is what you need to do for your local jobs first policy, this is what you need to do for your social procurement. This is what you need to do for your gender equality, this is what you need to do for your environmental footprint. This is exactly, step by step, what you need to do”

[P4].

Interviewees perceived a need for a well-resourced central agency of Government focused specifically on social procurement and not corollary functions (such as administration of the LJF Act), charged with responsibility for performing a compliance-oriented monitoring and assurance role. The absence of the compliance function was seen to be a key gap. Such an agency might be charged with responsibility for performing a compliance-oriented monitoring and assurance role directed at participants in the social procurement ecosystem.

There was no annual report authoritatively disclosing commitments entered into within a reporting period by contractors, or the extent to which commitments had been met. Interviewees felt this could occur at an aggregate (State-wide) level, or by requiring individual private sector organisations to make disclosures in their own public reporting in accordance with delineated standards, and with an emphasis on reporting outcomes rather than inputs.

Participants in the social procurement ecosystem were aware of the future potential for “whistleblowers” or external not-for-profits (or, indeed, quasi-regulators such as ombudsmen) to highlight and “name and shame” those falling short of their obligations. They noted that these dynamics often occur in connection with fully mature regulatory systems but felt social procurement had not yet reached that point.

It was observed that this kind of informed scrutiny could potentially bring credit to those who meet obligations and pursue a values-based, committed approach. One interviewee made the following observation:

“both compliance, but also a recognition that this is a potential competitive advantage for major contractors to be good at this [are driving activity]. There’s usually a mix of motivations … And there’s other pressures on companies as well, from shareholders, investors, consumers. It’s not only regulatory pressure but also to be able to demonstrate that they’re about more than profit”

[P21].

6. Discussion

Victoria’s approach to social procurement has been pioneering. It was the first State in Australia mandating social and sustainable objectives into government procurement [

15] (p. 15). In the other Australian States, until recently, there had been an absence of regulatory systems to govern social procurement. Subsequently, the Victorian model began to be used as something of a template by other jurisdictions. In 2021, Western Australia released a revised Social Procurement Framework, modelled on the Victorian precedent, which extended existing Western Australian procurement policies. This included, for example, applying graduated increases over three financial years in the percentage of total contracts to be awarded to registered Aboriginal businesses, rising to 4% of the value of contracts awarded in 2023/24.

In that same year, New South Wales updated its Procurement Policy Framework document, setting out a consolidated view of its Government procurement objectives and making this a defined “policy” under the State’s Public Works and Procurement Act, 1912. One of that policy’s five primary objectives pertained to “economic development, social outcomes, and sustainability” and it expressed the purpose of utilising procurement to support SMEs, Aboriginal businesses, disability employment organisations, and social enterprises. New innovative features coming into effect on 5 April 2022 included amendments to the 1912 Act to set obligations for agencies to take reasonable steps to ensure that the goods and services they procure are not the products of modern slavery, as well as requirements that agencies must use local SMEs in providing support for flood-affected communities.

If fully developed and rendered more coherent, the Victorian regulatory mechanisms could potentially serve as a valuable template for other jurisdictions, not only in Australia but around the Asia–Pacific.

To reach a conclusion as to whether the regulatory system under study in this article is coherent, applying Sheehy and Feaver’s theory, we need to work through three stages of analysis. In doing so, we will attend to the stakeholder concerns summarised in

Section 5 above, which highlight structural, governance, and operational incoherence concerns and have implications for regulatory coherence theory. Sheehy and Feaver (in their article [

19] at p. 966) conceptualised three levels of order, as per

Figure 3 below:

The first stage involves consideration of the structural dimension. The structures employed by the Victorian Government sought to adjust past patterns of expenditure on public infrastructure in quite radical ways. They were intended to dramatically increase participation by “disadvantaged Victorians” in the largesse of public infrastructure spending, with a hoped-for uplift in skills development. Organisations contracting to undertake infrastructure-related Government-funded work have a natural preference to experience low levels of external scrutiny of their performance in delivering against social procurement undertakings. This was affirmed in the interviews we conducted with market players. Psychological factors at play on the part of market participants concern potential for accountability via the courts or political processes; criticisms by non-government organisations, community groups, and the media; and the possibility of responsive market mechanism impacts, e.g., upon stock exchange share prices [

19] (pp. 971–972).

In the case of social procurement, the State has granted a privilege, by direct contractual means, to certain market players, namely, the ability to earn substantial amounts of money by participating in its “Big Build” infrastructure programs and delivering services and/or materials on-time in accordance with contractual requirements. Contracts issued spell out commitments as well as potential contract variations and financial penalties. In addition, the State has indicated to participating commercial entities its expectation of changed social behaviour, namely, the systematic propagation of social procurement practices. This has been expressed in the Invitation for Expression of Interest documentation on Government websites and in various ministerial pronouncements. Delivering on this expected changed general social behaviour is a clearly understood expectation of participation in the “Big Build”.

A system such as this remains vulnerable to non-performance by contracting private sector players, who may fail to meet commitments that were expressed in order to win the business, but who, some years into the life of a long-term contract, may be so integral to completion of the project that they cannot be simply dismissed from it.

In this context, given the substantial amounts of money at stake in the Victorian Government’s social procurement program, it might be expected that regulatees would be subject to specific accountability obligations, that there would be high levels of public disclosure, and that a subject matter specific regulator would be in place with the capability to exercise control powers (delegated to it by the State) to address the risk of non-compliances [

38]. The absence of these regulatory features inhibits the effectiveness of the system.

The State Government’s decision in its initial formulation of its Social Procurement Framework in 2018 to introduce a light-handed administrative function via the office of the Local Jobs First Commissioner, rather than an entity that would conform to generally understood conceptions of an empowered regulator, may at the time have been a pragmatic choice driven by a desire to expedite new approaches to contracting and not wait for the set-up of new administrative structures. With hindsight, this was unnecessarily generous and was too prolonged.

The LJF Act, in its section 18, did provide for potentially punitive functions on the part of the Local Jobs First Commissioner: the Commissioner could monitor and report on compliance with the “Policy” and “Development Plans” and take enforcement action in relation to breaches of the Policy and Plans. Associated with the latter set of functions were powers, set out in sections 24, 26, and 30 of the Act, to request information from agencies, issue compliance notices, and recommend to agencies that they seek injunctions or take other enforcement actions. However, as at 30 June 2024, after six years of operation of the adjusted regulatory regime, there has been no evidence in the public reporting of social procurement enforcement actions having actually been initiated by the Commissioner. Whilst, technically, the capacity to instigate enforcement actions has existed, there may be a question of the priority attached to these functions by a regulator whose primary focus is “local jobs”.

The second stage of analysis to consider when assessing a system’s regulatory coherence is its governance dimension, which is concerned with the legal content of linkages between actors. To date, in the design of Victoria’s Social Procurement regulatory scheme, there has been insufficient attention to the full range of levers and devices that can motivate regulatees to change their behaviour and social practices.

The potential levers classified by Sheehy and Feaver—persuasion, inducement, incentives, fear and anxiety—are intrinsic motivators that align with common conceptions of “sermons, carrots, and sticks” [

39]. Psychologically, sermons correspond to persuasion, carrots to inducements, and sticks to fear [

19] (p. 985) [

40].

As was seen in

Section 1 above, “sermon”-style approaches have been widely deployed in Victoria’s efforts to promote the uptake of social procurement. Deploying argument and principled debate, numerous governmental communications have emphasised the inherent virtue of redistributing social value to disadvantaged sub-groups in society. This positive motivator relies upon persuasion, which has been described as “an activity or process in which a communicator attempts to induce a change in the belief, attitude, or behavior of another person … through the transmission of a message in a context in which the persuadee has some degree of free choice” [

41] (p. 562).

Carrot-oriented approaches—a key element of the Victorian Government’s approach to date—hinge on the motivating effect of self-interest. This can take the straightforward form of paying a regulatee to engage in the desired behaviour [

42]. Incentive-driven or rewards-based compliance strategies can also take more sophisticated forms linked to market-oriented devices [

19] (p. 986). A concrete example of a carrot was given in

Section 5 of this article, i.e., social procurement being a mandatory requirement in order to win Government procurement contracts. The potentially greater use of sticks—anxiety and fear-based instruments—is discussed below.

The third stage of analysis required by Sheehy and Feaver’s framework is consideration of the operational dimension—the compliance and enforcement structures in place and whether they are best-fit for the particular social opportunity being regulated. In the case of social procurement, control powers were delegated to non-public economic actors (Tier-One contractor participants in infrastructure projects and, in turn, SMEs) who have the opportunity to participate in large-scale works projects in return for contractual commitments to meet “Local Jobs First” and other obligations. This is an instance of publicly sanctioned licences being granted to regulatees—the contractual outcomes occurring cannot be explained by “value for money” considerations alone.

The social procurement regulatory approach that has been employed to date in Victoria has conformed to the “distributed” configuration, depicted by Sheehy and Feaver in a tabular form, which we have reproduced in the (adapted)

Table 1 below.

The sequence of relationships requiring coherent alignment begins with the definition of a social problem and, in particular, the type of organising problem. In the case of social procurement, the starting point problem was to enable a societal opportunity—the leveraging of purchasing power resulting from infrastructure projects to create social value—and to guide this. Over time, however, as new practices have become established, the problem has shifted. There are now needs for both modifying and disciplining social practices, priorities which were considered adjacent to the “pure” distributed principles-based approach Sheehy and Feaver theorised as optimal in an early opportunity-enabling “guidance” phase. Modifying tends to require the prescription of technical and performance standards, which may be associated with creation of specific liabilities. Disciplining actions can include the application of market-based measures and the involvement of the media.

In our initial reflection on the viewpoints expressed to us by the stakeholders we engaged with in the course of this study, we were concerned by indications of a mismatch between the general principles inherent in Sheehy and Feaver’s conception of “good” regulatory design and the recent lived experience of practitioners of social procurement in the State of Victoria. For example, there was a consensus amongst the stakeholders we interviewed that there are needs to prescribe performance standards and to create information access that could enable market and media interventions. Developments along these lines seemed to be out of step with a distributed structural configuration.

Upon reflection, we have concluded that the issues at play are temporal ones. The regulatory system we have examined involved the opportunity-enabling establishment of a State-wide culture receptive to large-scale social procurement in construction and transportation infrastructure projects, and this was fostered by a distributed, principles-based approach. But there is an innate tendency for the requirements of a designed system, which is well-suited to a distributed structural configuration at its inception, to give way, over time, to a need for new disciplines and adaptations. This tendency for the optimal configuration of regulatory design to adjust and adapt over time is an area for further exploration in other studies in the future, whether in connection with social procurement or otherwise.

Victoria’s system of regulation of social procurement, having become established, is in the process of moving to a new phase of maturation, which should inevitably involve sanctions for the non-achievement of pledged targets.

We conclude that, moving forward, Victoria’s social procurement regime should not be built entirely around a distributed structural configuration. The characteristics of a decentred configuration have become appropriate to the context of social procurement in Victoria, with a pressing need for the existing regulatory system to be reinforced by stronger sanctions for the reasons outlined below.

The traditional conception of compliance was that it is best accomplished by emphasising and resourcing the enforcement function, but in recent times, there has been—at least in the context of social procurement—heightened emphasis on incentives and inducements as alternative means of modifying behaviour [

19] (pp. 984, 986, 988). There is, nevertheless, an important continuing role for “negative” compliance strategies, which create “oversight anxiety” and generate psychological unease. This is often associated with audit mechanisms. When regulatory systems are put in place that depend on threatening punishment for failure to comply, using devices which command specific changes in behaviour, this demonstrates belief in the disciplining effect of fear.

Consideration could be given to the imposition of additional mandatory disclosure requirements. This is an example of the creative use of incentives. A more creative incentive structure could be put in place that heightens the pressure on firms to alter their behaviour by increasing levels of disclosure, leading to the possibility of information impacts (either positive or negative) on share prices. Negative share market performance creates strong incentives for a firm to change behaviour, whereas the psychological assumption underpinning mandatory disclosure mechanisms is that “positive share prices will “re-enforce” desired behaviour” [

19] (pp. 986–987).

Sheehy and Feaver identified that when an organising problem can be characterised as a risk, a decentralised regulatory model (with control powers being delegated to specific regulatees) may be appropriate. Rules can mainly take the form of general principles rather than prescriptive rules, with regulatees given powers to delineate more specific rules in the form of “their own standards, procedures, and evaluative mechanisms”. In such instances, a “principles-based approach” may be adopted; inducement and persuasion are likely to be the most effective psychological levers, with surrounding systems able to be designed to effect changes in social practice by the use of guiding (rather than disciplining) behaviours [

19] (pp. 976–979, 992).

However, Sheehy and Feaver found that where the organising problem presents as an opportunity to advance society by generating a positive social effect, a decentred structural configuration is usually the best match. A decentred approach sees the State granting greater delegation of control powers to the regulator, including rule-making and adjudicative powers. Two of the key axioms they identified were that “the more general the primary obligation, the greater the need for the delegation of a secondary rule-making function” to a regulator, and that “the more general the rule, the more sophisticated the adjudicative and enforcement functions required” [

19] (pp. 969–970, 982–983).

Informed by this theoretical understanding, as well as the practical experience of the stakeholders interviewed in the course of our study, we concur with the stakeholder viewpoint that a lack of enforcement “muscle” has been a deficiency of Victoria’s regulatory framework. In effect, interviewees said to us that the effectiveness of Victoria’s Social Procurement Framework was at risk due to the inadequacy of compliance and enforcement mechanisms in place. We conclude that in the design of Victoria’s scheme, there was limited attention paid to the matching of the framework with the nature of the social opportunity being pursued. Going forward, Victoria’s social procurement regulatory regime should not be built around a distributed structural configuration, introducing elements of a decentred configuration is now appropriate. It follows that the structural configuration needs to be reinforced by stronger sanctions.

It is evident from our and other research that in order to fully operationalise a coherent ecosystem of new social procurement practices, attention needs to be given to four primary dimensions of strategy implementation: first, a contractual focus, involving the effective use of social procurement clauses in major contracts and their sub-contracts [

43] (Loosemore & Lim, 2018); second, a supplier focus, which involves direct engagement with social benefit organisations already active in the construction and transportation ecosystems; third, a market development focus where emphasis needs to be given to more fully developing the social enterprise sector; and fourth, a policy focus, i.e., the ongoing development and implementation of social procurement policies and regulations, driven by the Government [

5,

44]. These dimensions are all attended to in Victoria’s current regulatory approach.

The Victorian experience suggests that there are three critical requirements for a social procurement scheme driven by Government-funded purchasing to gain traction: (a) a large-scale public infrastructure procurement program; (b) a Government that is oriented towards “social justice”, i.e., the perspective that “everyone deserves equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities” [

45]; and (c) the presence of an effective system of regulation that transforms behaviour in purchasing and contracting processes. In Victoria’s case, the first two prerequisites were satisfied with the election of the Andrews Labor Government in 2014, followed by, in 2018, the promulgation of the State’s Social Procurement Framework, which made an effort to achieve the third objective.

However, as is evident from our analysis above, our view is that the regulatory system that was implemented is not fully effective. Legislative reform is warranted in Victoria, given its Government’s lofty goals for using social procurement to achieve societal transformation and the key role infrastructure provision for the transport and construction industries is intended to play in the achievement of those goals. A review and redesign of the regulatory scheme governing social procurement aspects of its “Big Build” is overdue. It seems likely that the regulatory system put in place in 2018 was intended to operate only as an interim or preliminary regulatory construct ahead of the intended design and implementation of a regulatory system tailored to the specific requirements for social procurement to flourish in the State. For whatever reason, that redesign had not occurred by the time of publication of this article.

A refreshed and enhanced regulatory scheme might encompass the following: (a) a revised definition of the role of the regulating body, ideally to be re-fashioned as Social Procurement Commissioner, with functions focused specifically on social procurement aspects of Big Build contracting; (b) a new fit-for-purpose Social Procurement Act separated out from the Local Jobs First regime; (c) granting the Commissioner rule-making powers; (d) granting the Commissioner the ability to make and enforce technical standards; (e) the provision of strengthened inquisitorial and intervention powers to the Commissioner; and (f) heightened disclosure obligations on regulatees, with more expressive articulations of the duties they owe.

Although some enforcement powers were (in a technical sense) granted to the Local Jobs First Commissioner via legislative amendments made in 2018, the Commissioner has, in practice, tended not to intervene in the marketplace dynamics surrounding public sector procurement. This is apparent from a review of the Local Jobs First Annual Reports, covering the period 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2024 [

32,

33,

34,

35]. The establishment of a special-purpose regulator specifically focused on social procurement issues is quite an obvious opportunity for the enhancement of the current system.

Legislation could give broader powers to monitor or audit compliance with undertakings given. A strengthened oversight and compliance program would hinge on enhanced public reporting and information transparency.

Additional “next-level” accountability mechanisms could potentially be brought to bear. In addition to the conventional mechanisms of political and legal accountability, steps could be taken to foster social accountability mechanisms (constituency relations to the media or community groups) and economic accountability through market mechanisms [

19] (pp. 971–972). These mechanisms hinge on information availability and would logically be linked to enhanced public reporting. This could see private sector players finding themselves answerable to “the market” or to representative interest groups for any non-compliance or misdeeds. Traditionally, the term “market-based accountability” has referred to stock-market responses [

46]. Increasingly, a source of pressure that has a real transformative effect is the dissemination of information by informed parties, including activist not-for-profits, which is critical of market players.

Amongst the factors that impede transparency are agreements around confidentiality risk, particularly in connection with litigation settlements. A behavioural adjustment needed on the part of regulatory agencies would be a willingness to engage in the “naming and shaming” of parties failing to meet their social procurement commitments.

The enhancements of Victoria’s Social Procurement Framework recommended in this article are summarised in

Table 2 below.