1. Introduction

Vernacular dwellings embody cultural heritage, revealing how natural setting, social change, and history interact. In China’s frontier zones, fortified settlements long served as residential–military hubs that protected local communities and encouraged cultural exchange [

1]. Over centuries of coexistence, these settlements also became focal points of cultural fusion. Guomari fortress, with its rich history, was established under distinctive historical circumstances. The eastern gate of the fortress featured a large red copper door, from which the name “Guomari” derives—meaning “red gate” in Tibetan [

2]. In 2007, Guomari village, the location of the fortress, was designated as one of the third batch of China’s Historic and Cultural Villages by the Ministry of Construction and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage [

3]. Guomari fortress is celebrated as a living fossil of China’s 2000-year-old fortified settlement architecture. Shaped by a complex natural environment and a culturally diverse human environment, the fortress exhibits distinct characteristics in its overall layout, street and courtyard organization, the distribution of single compounds, and architectural forms. These elements reflect a strong sense of regional and ethnic identity.

This study documents Guomari’s spatial structure, courtyard typologies, and layered defense through field survey and architectural analysis. The study enriches discussion of vernacular resilience and cultural hybridity in western borderlands.

Section 2 reviews Chinese and international work on vernacular fortifications and ethnic space;

Section 3 describes data and methods;

Section 4 reports results, including two courtyard cases;

Section 5 interprets the implications; and

Section 6 gives the conclusions.

1.1. Geographical and Cultural Environment

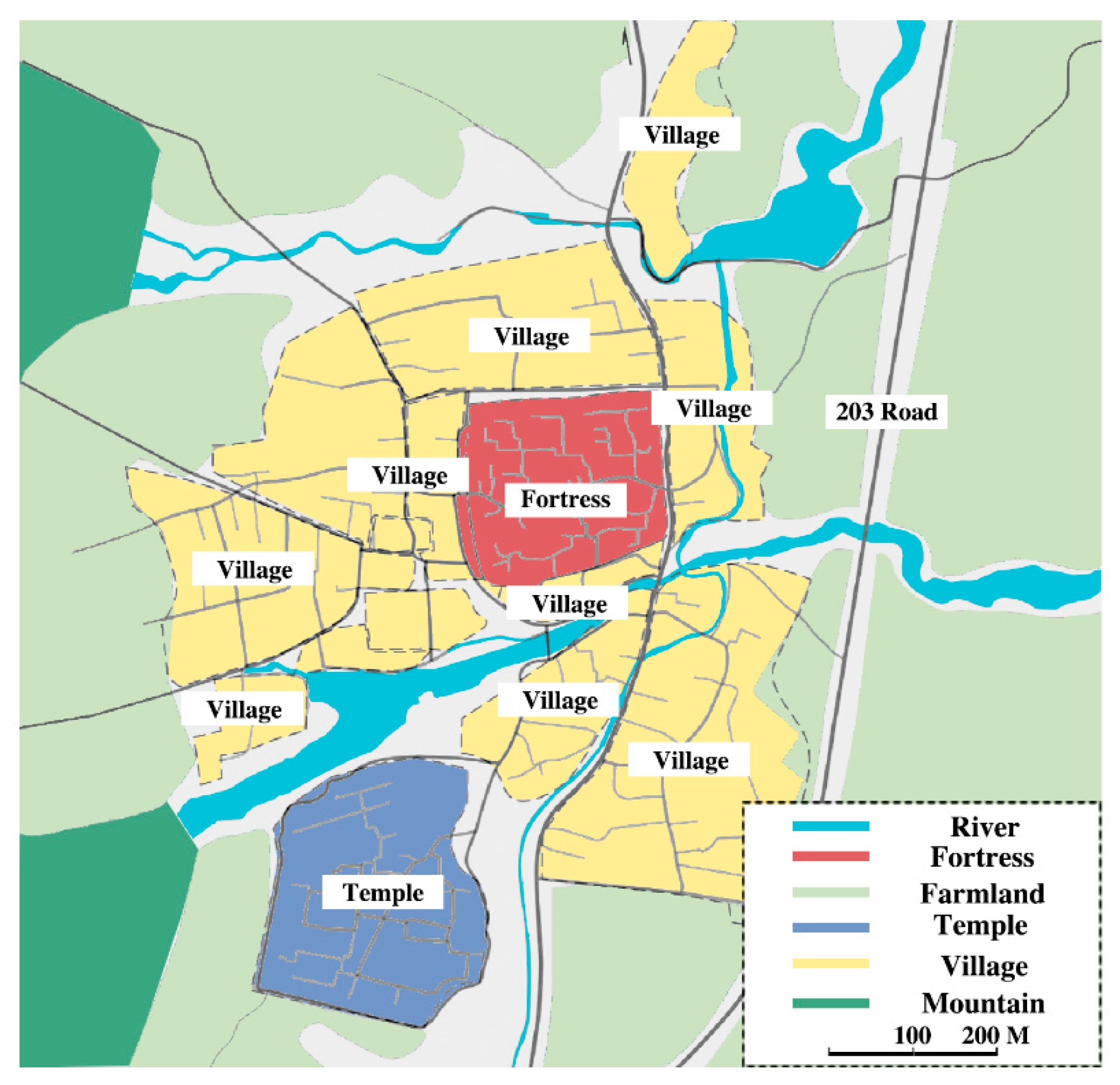

As illustrated in

Figure 1, Guomari fortress is situated in Guomari village, Tongren County, within the Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Qinghai Province, China. The Longwu River passes through Tongren and flows into the Yellow River, forming a broad and level valley with favorable natural conditions. Tongren lies at the transitional zone between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Loess Plateau, serving as a strategic junction where the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan converge. During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD), the imperial court recognized the military importance of this region and deployed troops to defend Hezhou and secure key transportation corridors [

4].

Tongren’s continental, semi-arid climate is windy and dry. Instead of pitched roofs for drainage, local buildings adopt broad, flat terraces better suited to these conditions [

5].

As

Figure 2 shows, vernacular dwellings line the west bank of the Longwu River, backing onto mountains and facing the water. Houses, temples, fields, and water sources cluster tightly with the terrain, creating an integrated setting that supports both everyday life and farming [

6].

Eastern Qinghai hosts a mix of ethnic groups whose interwoven cultures and beliefs create a distinct regional landscape. The area gave rise to the celebrated Regong art tradition, now a national treasure. Guomari village is a long-standing Tu settlement where Tibetan and Han practices blend in work, housing, dress, and diet, while the community follows Tibetan Buddhism.

1.2. Historical Development of the Fortress

The instinct for self-preservation is universal across species, and humans are no exception. In ancient times, communities in remote and inaccessible regions of China constructed fortress-style settlements to protect their homes, property, and lives. These fortified settlements integrated residential and defensive functions, enclosing villages with robust outer structures made of earth, timber, and stone, thus providing physical security for their inhabitants [

7]. The area where Guomari fortress stands has historically served as a military outpost along China’s western frontier. Historically, it hosted permanent garrisons tasked with defending against external threats. The fortress complex was constructed during the early Ming Dynasty under the national policy of establishing military-agricultural colonies for frontier defense. It is regarded as a “living fossil” of frontier military settlements, with historical roots tracing back to the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) [

1].

Completed in 1332, the fortress has a history spanning nearly 700 years and is the oldest and best-preserved fortress in the Tongren region [

8]. Originally established as one of the Li Garrisons (Li Tun) during the Ming Dynasty, it was part of the “Bao’an Four Garrisons” system, serving both strategic military and agricultural colonization functions. With the dissolution of the military colony system in the late Qing Dynasty, the fortress gradually shifted from a military stronghold to a permanent residential settlement passed down through generations [

9]. During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 AD), as religious influence—particularly from Longwu Monastery—expanded, Guomari was incorporated into the theocratic governance structure of Tongren. Han-style courtyard compounds became increasingly common, reflecting the gradual integration and fusion of diverse ethnic cultures.

During the Republic of China (1912–1949), better trade links and roads left Guomari’s walled plan intact but increased contact with nearby Tibetan and Tu groups. Han, Tibetan, and Tu households soon lived side-by-side inside and outside the walls, creating a mixed architectural fabric. After 1949 the fortress still retained its Ming–Qing structure [

10]. Rising prosperity let residents add living and work space, yet the core fortress and adjacent hamlets continue to follow their early patterns. Guomari thus offers a rare, continuous record of Tu–Han–Tibetan integration and a reference for the evolution of frontier garrison villages in Tongren (

Figure 3).

2. Literature Review

A comprehensive review of existing scholarship was conducted to position this study within the broader academic discourse on fortified vernacular settlements.

In China, numerous studies have examined the defensive layouts, spatial typologies, and cultural significance of traditional fort-type villages, particularly those located in the northern and northwestern regions [

1,

2]. Among these, Fujian’s Tulou have received significant scholarly attention as emblematic examples of fortified vernacular architecture. Researchers have highlighted their circular or square forms, collective living patterns, and integrated defense systems that reflect a strong correlation between spatial design and social organization [

12].

At the regional level, scholars have explored the historical geography and strategic functions of the four major fortress settlements in the Tongren region of Qinghai Province, identifying Guomari fortress as one of the key case studies [

4]. Further investigations in Shaanxi Province have documented the clustered spatial distribution of traditional fortified villages, shedding light on the broader organizational logics of defensive settlements in northwestern China [

13]. Bibliometric analyses have revealed a growing international interest in China’s fortified heritage, particularly in terms of spatial planning, cultural hybridity, and conservation frameworks [

14]. However, most of these studies have focused on eastern and central regions, leaving frontier areas such as Qinghai relatively underexplored.

In particular, limited scholarly attention has been paid to the vernacular traditions of the Tu ethnic group, despite their significant influence on local architecture and spatial practice. Studies concerning their belief systems and decorative arts remain scarce, even though these elements play a crucial role in shaping built environments in the Huangnan region [

15,

16].

Comparative work shows that fortified settlements worldwide blend civic life with defense. Roman frontier forts in Wales, for example, used topography, resources, and transport links to secure territorial control [

17]. Similarly, fortified cities in early modern Europe have been described as urban spaces where war was embedded into everyday life through compressed street grids, multifunctional bastions, and ritualized defense practices [

18].

Studies of other regions reveal comparable spatial logics. Alley intersections in Saudi settlements create transitional pockets that host layered, informal activity [

19]. In Matera, Italy, the cave city Sassi and its modern quarter hold distinct yet interwoven identities; integrated surveys and participatory mapping suggest design strategies for renewed social cohesion [

20]. Network analysis of Amasra, Turkey, shows fortress walls and gates still anchor pedestrian flow as enduring social nodes rather than barriers [

21].

These cases offer a cross-cultural lens for Guomari: its maze-like alleys, rooftop linkages, and ritual features likewise fuse household life with collective defense, forming a hybrid system where architectural form, religious order, and security are inseparable.

3. Study Materials and Methods

This study adopted a structured, multi-method research design that integrated literature analysis, field investigation, geospatial modeling, architectural documentation, and interpretive synthesis. Data were collected and processed through seven sequential modules, as visualized in

Figure 4.

To establish the research context, a review of national and regional studies on fortified settlements was conducted. Emphasis was placed on identifying underexplored areas in Qinghai Province and the architectural traditions of the Tu ethnic group, which are seldom addressed in mainstream vernacular architecture literature.

- 2.

Field Survey

On-site data collection took place in 2023. Courtyard layouts, wall dimensions, and structural elements were systematically measured using Bosch GLM4000 (Manufacturer: Bosch (China) Investment Ltd., bought in Xi’an, China) laser rangefinders (±2 mm accuracy) and cross-verified with 50-m steel tape measures (±1 cm accuracy). Accuracy was controlled within ±5 cm by resurveying key architectural nodes.

In parallel, high-resolution photographs of façades, rooftop structures, and decorative elements were captured using a Nikon D800 (Manufacturer: Nikon Sendai Co., Ltd., bought in Xi’an, China) and DJI Mavic Air (Manufacturer: Shenzhen DJI Sciences and Technologies Ltd., bought in Xi’an, China) to support spatial documentation and later illustration.

- 3.

Data Processing and Visualization

Building outlines and courtyard footprints were digitized in ArcGIS Pro 3.3 using MapWorld (1 m resolution) and OpenStreetMap (No specific version) (5 m resolution) basemaps. Terrain modeling was conducted using Copernicus and Copernicus DEM Version 5.0 (30 m resolution) to generate contextual 3D surfaces.

Spatial analysis—such as area measurements, network patterns, and topological configurations—was performed using ArcGIS Pro 3.3 and R 4.5.0. Final figures, including architectural plans, elevations, and 3D terrain visualizations, were refined in Adobe Illustrator 2024 and Photoshop 2024.

- 4.

Validation

To ensure data reliability, 10% of key architectural measurements were re-checked against CAD-generated outputs. Cross-verification with field sketches was conducted to confirm dimensional consistency.

- 5.

Case Study Analysis

A typological framework for courtyard classification—derived from broader analysis of traditional settlements—was applied to Guomari fortress. The fortress’s spatial organization, defensive layering, and architectural forms were interpreted to uncover underlying cultural and spatial logics, including the integration of Tu, Han, and Tibetan influences. In addition to physical surveys, insights were drawn from oral histories and secondary literature on Regong culture, enriching the interpretation of Guomari’s hybrid architectural identity.

- 6.

Discussion and Conclusion

The study concludes with interpretive reflections on Guomari’s hybrid spatial patterns, multi-ethnic symbolism, and implications for the conservation of vernacular fortified heritage under modernization pressures.

All figures and architectural drawings presented in this study were collaboratively produced by the author and the research team. Liyue Wu was responsible for organizing and processing the final outputs, while field drawings, architectural surveys, and diagram editing were completed through joint efforts. Textual interpretation incorporated both local oral histories and secondary literature on fortress settlements and Regong culture.

In this study, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were used only for language enhancement purposes, such as grammar and punctuation correction. No GenAI tools were used for content generation, data analysis, figure creation, or interpretation of findings.

4. Results

The spatial organization of Guomari fortress reveals a hierarchical defensive logic structured around three interrelated layers: (1) natural terrain and enclosing walls, (2) labyrinthine alley networks with variable-width paths and irregular intersections, and (3) interconnected rooftops and courtyard-based defense units. This multi-tiered layout reflects both military rationality and local adaptations to environmental and cultural constraints [

22].

4.1. Defensive System and Spatial Structure of the Guomari Fortress

The following subsections examine in detail the three-tiered defensive system of Guomari fortress, as defined by its topographical setting, internal alley network, and courtyard-level architectural strategies.

4.1.1. First Tier: Natural Terrain and Enclosing Walls

The external defense system of Guomari fortress addresses security at a comprehensive and macro scale. It integrates the advantages of natural topography with man-made fortifications and strategic nodes to establish a robust defensive barrier.

To fulfill its role as a military garrison, Guomari Ancient fortress was strategically sited to maximize the defensive benefits of the surrounding landscape. Constructed amidst steep mountains and ravines, the fortress backs onto the mountainous terrain and faces the Longwu River, with only a single access road—an arrangement that made it easy to defend and difficult to attack. Located on the western terrace formed by sediment from the Longwu River, the fortress occupies elevated terrain, enabling wide-range surveillance of the surrounding environment from atop the walls. Natural elements—including mountains to the east, rivers to the north and south, and the protective western ridgeline—collectively serve as physical barriers against invasion and shield the village from prevailing cold winds and sandstorms brought by the westerlies [

23] (

Figure 5).

Enclosing the settlement with tall rammed-earth walls on all four sides was a common defensive strategy in ancient, fortified villages, intended to repel invasions and mitigate regional threats. Guomari fortress forms a nearly rectangular enclosure measuring approximately 200 m from east to west and 170 m from north to south, covering a total area of around 34,000 square meters. The outer base of the walls is constructed from river cobblestones, while the inner core consists of densely compacted rammed earth. The structure stands approximately 11 m high, with a base width of about 4 m tapering to 1.5 m at the top. These massive, solid walls not only present an imposing and fortified image but also serve as both a psychological deterrent and tangible protective structure for the inhabitants [

24].

4.1.2. Second Tier: Labyrinthine Alley Networks with Variable-Width Paths and Irregular Intersections

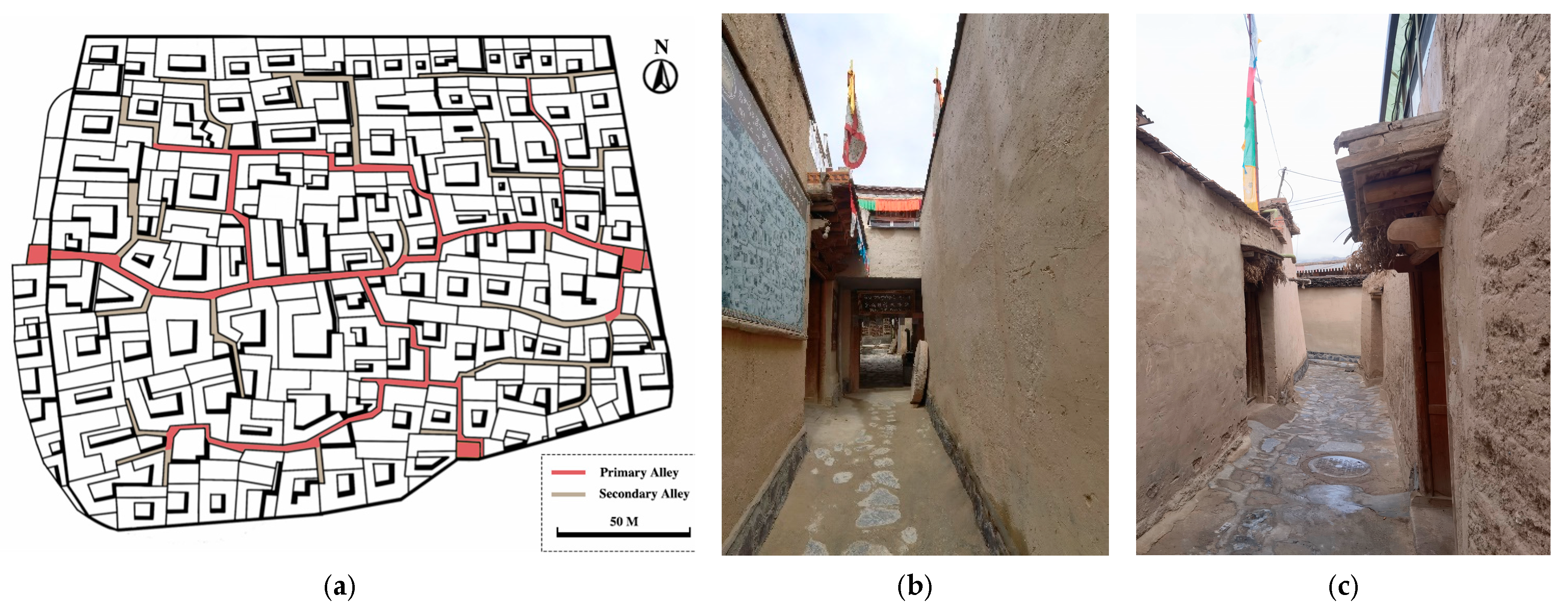

The second defensive layer of Guomari fortress consists of its internal circulation system, composed of gates, alleys, and courtyard configurations. This internal structure functions as a supplementary yet critical layer within the broader spatial defense network. When the fortress was originally constructed, three gates were installed on the east, south, and west sides.

The eastern gate tower consists of a two-story, three-bay structure. On the ground floor, the northern bay serves as the entrance, connecting directly to a narrow alley. The two southern bays are enclosed by rammed-earth walls and equipped with small doors, functioning as guardrooms. The upper floor forms a watchtower, offering elevated views of both the interior and surrounding terrain.

Internally, the fortress is structured around a primary east–west axis, linked to a southern gate and extended by three secondary alleys that branch out in both north–south and east–west directions (

Figure 6a). This forms a layered and hierarchical network. Although seemingly irregular, the layout is deliberately structured, with narrower secondary alleys creating complexity and reducing the efficiency of movement for unfamiliar entrants. The resulting alley system is spatially tight and enclosed, with height-to-width ratios often reaching 1:4.5 (

Figure 6b). This complex, narrow, and labyrinthine alley network offers long visual corridors, limited width, and poor overall accessibility—characteristics that enhance defensive capability [

25].

In Guomari fortress, intersection spaces function not only as traffic nodes but also as multifunctional venues for socialization, rest, and production activities.

Table 1 and

Figure 7 summarize the classification of these intersection types and their corresponding spatial locations. Given the dense, web-like pattern of alleyways within the fortress, these intersections serve as crucial hubs connecting main pathways with secondary alleys. Characterized by their relatively open layout, they act as micro-plazas that enrich village life by facilitating interpersonal interactions and community engagement. Beyond their practical functions, these spaces also embody symbolic meanings, often reflecting the village’s social structure, ethical relationships, and traditional feng shui beliefs [

26]. This aligns with findings in Amasra (Turkey), where network analysis shows that fortress gates and walls have consistently high centrality and function as enduring social hubs [

21], similar to how L- and T-shaped intersections in Guomari mediate defensive layouts and community interaction.

One example is shown in

Figure 6c, where three residential entrances are located within a short L-shaped alley of less than 10 m. Although tightly spaced, the doorways are deliberately staggered rather than directly aligned. This spatial arrangement reflects the Han Chinese belief that opposing doors may cause interpersonal tension or disputes—an idea deeply rooted in vernacular feng shui practice. Despite the narrowness of most alleyways in the fortress, some larger intersections were observed to host small gatherings of residents. These slightly more open nodes, while not formal public spaces, serve as transitional areas that support informal communication and spontaneous interaction, consistent with spatial behaviors documented in traditional settlements in other countries and regions [

19,

20].

Buildings within the fortress typically have blank façades facing the streets, with no windows along the alleys. The spatial interfaces are uniform, and courtyard entrances are often discreetly placed at the ends of alleys or on recessed sides. As residents gradually adapted the streets to suit everyday needs, an organic aesthetic emerged—rooted in local use and regional culture [

27].

From a tactical standpoint, these narrow, high-walled alleys create psychological pressure and restrict the field of vision. Their irregular forms, dead-ends, and alternating openness create disorientation. Even if an intruder breaches the outer gate, the probability of navigating this maze-like network is low.

4.1.3. Third Tier: Interconnected Rooftops and Courtyard-Based Defense Units

As the innermost layer in Guomari fortress’s defensive system, courtyard compounds are not merely residential units but strategic architectural components. Each compound is enclosed by tall perimeter walls that clearly demarcate exterior from interior space. These walls are solid, smooth, and thick—difficult to climb without equipment, even after breaching the outer defenses.

Although the courtyards appear independent, they are in fact interconnected via rooftop pathways, forming a tightly linked elevated network among adjacent households.

Figure 8a presents an aerial view of this rooftop connectivity system, illustrating movement paths along wall alignments. The enclosing courtyard walls typically extend 0.5 to 1 m above the residential rooflines. Between neighboring compounds, short parapet walls allow residents to traverse across rooftops while maintaining separation under normal conditions, as shown in

Figure 8b.

In times of crisis or armed conflict, this rooftop network enables a decentralized and flexible response. Residents can navigate the fortress from above, shielded by the parapets, thereby providing mutual assistance and maintaining mobility even under siege conditions. The system thus represents a vernacular form of distributed defense embedded in household architecture.

Courtyard entrances are typically equipped with standardized wooden plank doors, 50–80 mm thick and approximately 1.6 to 1.8 m in height. Their uniform, unadorned appearance serves a defensive purpose: it prevents intruders from identifying specific households based on visual cues. Additionally, the small entry size restricts the number of people who can enter simultaneously, reinforcing the architectural emphasis on controlled access and defensive containment.

4.2. Courtyard Layouts and Architectural Characteristics Within the Fortress

The establishment of Guomari Ancient fortress was closely linked to its strategic location as a gateway to the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Historically, this site attracted a multiethnic population—including Tibetans, Han Chinese, and the Tu ethnic group—whose prolonged coexistence fostered complex patterns of cultural integration.

In its contemporary form, the fortress is predominantly inhabited by the Tu ethnic group. The architectural forms and interior decorations of the traditional dwellings reflect a fusion of Han construction techniques and spatial organization with the practical living habits of the Tu people. Culturally, the local identity has evolved around Tibetan Buddhism, while folk customs are primarily shaped by the traditions of the Tibetan, Tu, and Han populations.

4.2.1. Basic Layouts of Courtyards Within the Fortress

The Zhuangkuo-style courtyard, characterized by its rammed-earth enclosures and compact U-shaped configuration, represents a vernacular adaptation to the arid plateau climate of Qinghai. Unlike the more open Siheyuan compounds found in northern China, the high walls and limited fenestration of Zhuangkuo courtyards reflect a dual response to climatic extremes and historical security concerns [

8]. These traditional dwellings are enclosed on all four sides by rammed-earth walls. The foundations are constructed from river stones sourced from the Longwu River and covered with a surface layer of loess. Wall thickness ranges from approximately 0.6–0.7 m at the base, tapering to around 0.4 m at the top, with an overall height ranging from 3 to 5 m.

Inside the courtyard, flat-roofed buildings made of timber and earth form a compact Siheyuan configuration. Due to spatial constraints within the fortress, dwellings are relatively compact. To expand usable space, many dwellings incorporate a second floor above the main hall, constructed in timber. This vertical expansion reflects vernacular strategies for passive climate control, including improved envelope insulation and internal heat retention [

28].

The internal layout of the dwellings is shaped by long-term adaptation to residential and production needs. A typical courtyard includes a main gate, main room, side rooms, kitchen, toilet, storage rooms, livestock pens, and a small interior garden (

Figure 9). Influenced by local religious beliefs, many homes also include a prayer room or meditation chamber for Buddhist practices. In local culture, spatial hierarchy is clearly emphasized. Ground floors generally serve as kitchens, reception areas, storage, and livestock shelters, creating multifunctional zones with cohabitation of humans and animals. The second-floor corridor rooms are typically used as bedrooms, prayer areas, and, in some cases, meditation spaces. These layouts are highly compact and functionally efficient, with zones densely arranged within limited space.

Compared to Zhuangkuo-style dwellings in other areas of eastern Qinghai, courtyard gates within Guomari fortress tend to be smaller in size. Gate ornamentation varies by the status of the household but remains generally modest and restrained.

The internal layout of each residential compound is flexibly adapted based on household size, functional needs, and production activities. Courtyard layouts within the fortress are primarily categorized into four types: Single-line-shape, L-shaped, U-shaped, and Enclosed-courtyard-shape (

Table 2). While these configurations maintain the core architectural characteristics of Zhuangkuo-style courtyards of eastern Qinghai, their specific forms exhibit site-responsive variations.

To maximize use of the constrained space within the fortress, many courtyards evolved from traditional layouts into irregular forms adapted to the narrow alleys and fragmented lots. These spatial adaptations reflect practical compromises made between architectural tradition and the defensive geometry of the settlement.

Table 2.

Examples of courtyard layout types in Guomari fortress, including single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and enclosed-courtyard shape, and their spatial configurations within the fortress with corresponding locations in

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Locations of the example courtyards in Guomari fortress, with single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and enclosed-courtyard layouts. Source: drawn by the author.

Figure 10.

Locations of the example courtyards in Guomari fortress, with single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and enclosed-courtyard layouts. Source: drawn by the author.

4.2.2. Case Study: Courtyard No. 090

Guomari fortress is home to numerous folk craftsmen and artisans engaged in Regong art. Among them is Mr. Sangjie, the owner of Courtyard No. 090 in Guomari fortress. His residence possesses a rich collection of traditional artworks, including Regong-style woodcarvings, scripture-printing wooden blocks, appliqué embroidery, and Thangka paintings—each representing distinctive forms of vernacular artistic expression. Immersed in this environment, one can fully appreciate the charm and cultural depth of the Regong artistic tradition.

Courtyard Layout:

The Sangjie residence is enclosed on all four sides by tall courtyard walls, forming a rectangular footprint. The internal building arrangement follows a U-shaped configuration, which is characteristic of Zhuangkuo-style courtyards commonly associated with the Tu ethnic group. As with most compounds within the fortress, the layout is relatively compact, measuring approximately 15.5 m in width and 12 m in depth, with enclosing walls rising to about 5.5 m in height (

Figure 11).

The western wing preserves the original two-story structure. The ground floor is organized into a grid of three bays in depth by three bays in width, with each bay measuring approximately 1.6 m deep and 2 m wide. The upper floor contains two bays in depth and four bays in width, featuring an open-eave corridor used for daily activities such as drying crops and household chores.

Figure 6 illustrates the floor plan of this double-story residence.

Due to the generally shorter stature of local inhabitants, the interior spaces and story heights are lower than those typically found in the Central Plains of China. This compact vertical layout also enhances thermal performance by conserving heat in the region’s cold climate [

29].

In response to evolving residential needs, the homeowner later renovated the eastern and southern wing rooms. While the new additions adhere to traditional construction techniques, they feature increased ceiling heights and improved interior volume to meet contemporary comfort standards.

The Architectural Features:

The courtyard buildings are constructed using a timber–earth structural system. Exterior façades are decorated with wooden lattice windows carved in floral patterns, while five-colored wind horse prayer flags hang beneath the eaves—symbolizing local ethnic identity and reflecting Tibetan Buddhist influence. Interior partitions are composed of wooden panels approximately 1.1 m in height. These are modest in form and sparsely ornamented, serving primarily to subdivide interior spaces. Three of the interior walls feature recessed niches used for the organized display of kitchen utensils and ritual objects. These niches fulfill both decorative and functional purposes and are commonly found in the domestic architecture of both Tibetan and Tu communities (

Figure 12a).

Folk decorative elements with strong regional character are widely present throughout the interior, adding color and visual vitality to the otherwise restrained architectural forms. In the western bay of the main room’s first floor, a finely crafted appliqué Thangka depicting White Tara is hung on the wall (

Figure 12b). The deity is shown with a white jade-like body, jet-black hair, a third eye on her forehead, and eyes on each of her palms and soles—earning her the title “Seven-Eyed Buddha Mother,” a figure associated with longevity and blessings [

30]. The Thangka is rendered with intricate detail and a serene facial expression. Her eyes, vividly painted, give the impression of following the viewer from any angle. This work exemplifies the artisanal excellence of Regong appliqué art in Tongren. Most Regong Thangkas center on themes drawn from Tibetan Buddhist cosmology and narratives.

In terms of door and window decoration, the architectural style in these courtyard dwellings remains modest and function-oriented. The courtyard entrance typically consists of double-leaf wooden plank doors embedded within thick earthen walls, topped by projecting eaves for protection. Traditional Han-style structural components—such as door beams, wind boards, door pins, frames, and thresholds—are retained and clearly visible (

Figure 12c). In certain compounds, the door beams and pins are intricately carved with Tibetan motifs, serving as symbols of the homeowner’s economic status and cultural affiliation.

A local folk custom involves inserting willow branches into the door beam as a talisman to drive away evil and pray for a good harvest [

15]. Each year at the Dragon Boat Festival, residents bathe in the Longwu River at dawn. The male head of household collects willow branches and wildflowers, weaving them into floral belts worn by children to convey wishes for health and protection.

Within the courtyard, doors and windows are generally designed with restraint. Single-leaf doors are common and are often adorned with auspicious patterns painted using

tsampa, a local material made from roasted barley flour. The windows are side-hinged and exhibit a variety of decorative styles, including vertical lattice patterns with three evenly spaced muntins per panel, as well as traditional motifs such as tortoiseshell patterns and the Buddhist endless knot [

31] (

Figure 13a–c).

In the cold and windy climate of northwest China, door curtains are essential features of everyday life (

Figure 13d). Most courtyard doorways are fitted with coarse linen curtains, ranging from 5 to 15 mm in thickness. These curtains serve both functional and symbolic purposes. Their main bodies are adorned with traditional Tibetan geometric patterns, while the upper sections are decorated with the Eight Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism, produced using duixiu, an appliqué technique. These motifs are among the most commonly used decorative elements in local Tibetan Buddhist architecture [

11]. In addition to providing insulation and windproofing, the curtains add color and visual richness, infusing the domestic environment with spiritual significance and aesthetic vibrancy.

The Sangjie’s residence contains a large collection of finely crafted wooden artifacts, including woodblocks used for printing Buddhist scriptures (

Figure 14). These blocks are intricately carved with motifs commonly associated with Tibetan and Tu religious practices, such as prayer flags and Buddhist mantras. The carving lines are smooth yet powerful, demonstrating both aesthetic precision and spiritual significance.

Displayed prominently within the residential interior, these artifacts exemplify the fusion of artistic practice and domestic life. They reflect the integration of Tibetan and Tu craftsmanship into the architectural environment of Guomari fortress. Beyond their material beauty, these woodblocks serve to deepen the spiritual atmosphere of the space and connect the everyday functions of the household with enduring cultural rituals. As such, they enhance spatial experience and reinforce the idea that artistic expression is not peripheral but integral to the fortress’ architectural identity.

The local woodblock carving process is complex and highly specialized. Artisans typically use birchwood harvested from the nearby arid, high-altitude regions. The raw wood is first cut into appropriately sized blocks and then subjected to a series of treatments, including soaking, boiling, drying, and planning, carried out before carving begins [

32]. Throughout the engraving process, skilled craftsmen carefully check both the textual and visual content to ensure accuracy and fidelity to the original design.

Once a woodblock is completed, it undergoes a preservation treatment. The block is soaked in melted butter for a full day and then cleansed using a solution made from boiling the root of a local plant known as Suba. This final process enhances the durability of the block by protecting it from moisture, wear, and insect damage. Woodblocks treated in this way are known for their longevity and reliability: they can produce high-quality prints over extended periods and resist both physical deterioration and biological decay [

33].

These woodblocks embody the precision, accumulated knowledge, and aesthetic sensibility of local craftsmanship. As tangible expressions of intangible cultural heritage, they illustrate how technical mastery and spiritual devotion are interwoven in the everyday lives of fortress residents.

4.2.3. Case Study: Courtyard No. 039

Among the traditional dwellings preserved within Guomari fortress, the Danbu residence, located at No. 039 in Guomari fortress, stands out for its strong regional character and intact architectural features. This dwelling retains clear traces of earlier modes of production and daily life, serving as a spatial repository of intergenerational memory and emotional continuity for the local community. It reflects not only the lived experiences of successive generations but also the evolving customs and lifestyles of the Tu people across historical periods.

According to accounts from village elders, the residence was built over 600 years ago and also remembered as the birthplace of Danbu Laoye, a revered local folk hero celebrated for his moral integrity and chivalric spirit. Oral narratives recount his defense of the vulnerable and his fearless opposition to injustice. These stories remain actively circulated among the village population, reinforcing communal identity and values through the preservation of place-based memory.

Courtyard Layout:

The residence exemplifies the Tu-style Zhuangkuo courtyard dwelling. Its perimeter walls exhibit a distinctive construction. The foundation is constructed from local stone, while the upper sections are made of rammed earth reinforced with plant fibers. The wall base is approximately 1 m thick and tapers upward at a gradient of 1:12 to 1:15, reaching a total height of about 5.6 m. These walls are solid and heavy, offering not only physical protection from environmental threats and historical conflict but also a strong sense of psychological security for the inhabitants [

34] (

Figure 15).

The courtyard follows an L-shaped spatial layout. Upon entering the narrow courtyard, one encounters a two-story building located on the northern side, arranged in a single-line configuration (

Figure 16). This linear courtyard layout is typical of Tu residential architecture. Owing to the region’s harsh climate and limited construction resources, the overall scale of the structure is compact. Thick external walls help insulate the interior, retaining heat and maintaining indoor thermal stability.

The ground floor is organized into four bays, accommodating key domestic functions such as the kitchen, storage, and animal shelter. A wooden staircase on the west side leads to the upper level, which contains three bays. The timber-framed flat-roof structure features a design known locally as the “tiger embracing its head,” in which the central bay serves both as the elder’s bedroom and a storage area for grain and daily essentials.

A prayer room was established by Danbu Laoye in the western bay of the upper floor, where he enshrined a statue of Lord Zhenwu, the mountain deity, to whom he remained devoted throughout his life. A separate chamber on the southern side was designated for meditation—an enclosed, insulated space lined with animal hides and blankets, containing only a low table. The open platform adjacent to the second floor compensates for the limited courtyard footprint, serving as a drying terrace during harvest season thanks to its unshaded, sunlit exposure.

Due to the harsh natural environment and availability of residential and productive resources, local residents have developed the habit of stockpiling daily necessities. Agricultural tools and harvested grains require designated storage areas, which are systematically integrated into the domestic space. In traditional Tu dwellings, storage generally takes two forms: enclosed and open. Enclosed storage refers to interior rooms specifically designated for this purpose, typically located in the southern section of the west wing or within the south room of the compound. In contrast, open storage areas are often situated near the main entrance, allowing for accessibility and ventilation.

The storage system in the Danbu residence is relatively distinctive. Given the constraints of limited interior space, the residence optimizes its layout by integrating storage and productive functions within the main building. This results in a multifunctional spatial configuration that accommodates both everyday living and household operations. The storage areas are densely filled with a variety of items used in daily life and agricultural production, including kitchenware, tableware, farming tools, and herding implements (

Figure 17a).

Located on the eastern side of the living room are two pens designed to house cattle and sheep. These animal enclosures are integrated into the residential layout, coexisting with storage and living spaces under the same roof (

Figure 17b).

The Architectural Features:

The building façade is simple and unadorned, in keeping with the minimalist aesthetic of Tu vernacular architecture. Certain segments of the outer wall are constructed using a traditional lattice-wall technique, in which locally sourced willow branches are woven into a structural grid and then coated on the exterior with a thick layer of raw earth. This construction method is commonly found in the libalou, a lattice wall tower dwelling associated with the Salar ethnic group in Qinghai (

Figure 18a).

These woven earth-and-branch walls provide sufficient load-bearing capacity while remaining lightweight, thereby reducing stress on the overall structure. The outer surfaces are finished with an additional layer of mud plaster, which enhances both thermal insulation and weather resistance. This technique yields a wall surface that is simultaneously practical in function and modestly aesthetic in appearance.

The interior wooden framework is minimally decorated, reflecting the utilitarian approach typical of Tu dwellings. The timber is either darkened by prolonged smoke exposure or coated in black pigment, then polished with linseed oil or ghee to achieve a smooth, slightly glossy surface. This treatment not only enhances visual uniformity but also protects the wood from insect damage and improves resistance to moisture infiltration.

In terms of interior furnishings, the western section of the ground floor functions as the primary living room. The walls are clad in thin wooden panels coated with a clear varnish. Select sections feature built-in wall niches framed with carved decorative borders. These niches vary in size and shape to accommodate different household items, which are neatly arranged to create a visually layered and orderly display (

Figure 18b).

A kang, a heated earthen bed platform approximately 0.6 m in height, occupies a central position in the living room and serves as the family’s primary activity space during winter. Constructed from raw earth, the kang is valued for its thermal conductivity. Multiple layers of felt are laid on top to provide insulation and comfort, while its bright colors and geometric patterns add decorative richness.

A distinctive spatial feature of traditional Tu and Tibetan dwellings is the integration of kitchen and living room functions within a single room. The stove is structurally connected to the kang, enabling residual heat from cooking to be channeled into the bed platform, thus providing space heating in a highly energy-efficient manner (

Figure 19a).

Both the Tu and Han ethnic groups share beliefs in the Kitchen Deity, though their associated rituals differ. In Tu households, the stove’s ritual zone lacks a portrait of the deity. Instead, a thin layer of white clay or flour is applied directly to the sacred stove surface. A wooden offering board is placed beneath, where steamed buns and butter lamps are arranged as offerings (

Figure 19b). During the ritual of sending off the Kitchen Deity, residents light incense and sprinkle aromatic smoke over the stove. The white clay is then covered with yellow clay to symbolize the deity’s departure. When welcoming the deity’s return, a fresh layer of white clay is applied, signifying renewal and spiritual cleansing [

16].

As Kitchen Deity culture evolved, a range of auspicious symbols—associated with blessings, harvest, and well-being—began to appear on stoves and surrounding kitchen walls. These motifs, traditionally drawn with tsampa, include the swastika, the Eight Auspicious Symbols, flaming mani jewels, white conch shells, and scorpions (

Figure 19c). During the Chinese New Year, each household decorates its kitchen walls with these tsampa-based images as spiritual offerings. These practices are believed to attract good fortune, ensure a continuous fire source, secure abundant harvests, and promote household prosperity. Together, they form a sacred and enduring ritual system rooted in Kitchen Deity worship.

A covered corridor connects the main gate of the Danbu residence to the inner courtyard. The corridor is enclosed by smoothly plastered earthen walls, finished with raw mud, presenting a simple and unembellished aesthetic. The courtyard ground is fully paved with locally sourced river stones, providing a hard surface treatment that facilitates cleaning and maintenance. This paving also prevents wetting of shoes and socks during rainy or snowy weather while adding modest visual texture.

The main gate itself is simple and unornamented, standing at approximately 1.7 m in height. Its relatively small scale enhances wind protection and thermal insulation, while also functioning as a physical deterrent to unauthorized entry (

Figure 20a). The lintel above the entrance bears a newly installed plaque, and the only decorative element is a wind horse motif affixed above the door, symbolizing favorable weather and continued family prosperity.

Windows inside the residence are few in number and modest in size yet constructed with careful craftsmanship. A particularly notable example is located above the kang in the main room. It features a fully enclosed, double-leaf, inward-opening structure made from thick, solid wooden panels. A cylindrical interior latch allows the window to be opened or closed by rotation, ensuring secure closure even during strong wind conditions (

Figure 20b,c).

In summary, the Danbu residence embodies a deeply localized form of architectural knowledge, one shaped by environmental adaptation, multi-functional spatial organization, and embedded ritual practices. From its compact L-shaped layout and multifunctional living-storage areas to its symbolic stove rituals and structural innovations such as lattice walls and kang systems, the residence offers a holistic expression of Tu vernacular dwelling culture. Its integration of religious belief, environmental pragmatism, and ethnic identity—along with oral histories tied to figures such as Danbu Laoye—demonstrates how domestic space in Guomari fortress operates as a living archive of social memory, intergenerational continuity, and cultural resilience.

A concise overview of the two selected courtyard compounds—#090 and #039—is presented in

Table 3. By setting their spatial configuration, functional zoning, craft features, and defensive logic side-by-side, the table highlights the range of vernacular adaptations within Guomari fortress and frames the detailed plans and photographs that follow.

5. Discussion

This study directly responds to the research gap identified in earlier scholarship concerning the vernacular defense settlements of Qinghai and the under-documented architectural practices of the Tu ethnic group [

15,

16]. Through empirical analysis of Guomari fortress, the research provides new spatial and cultural evidence that enriches understanding of multi-ethnic architectural integration in frontier regions.

Guomari fortress exemplifies how vernacular architecture in frontier regions integrates defense, ecology, and cultural symbolism. Its spatial organization reflects a three-tiered defensive system composed of:

Natural terrain and a continuous rammed earth wall that leverages valley topography for surveillance and wind shielding;

Labyrinthine alley networks with compressed proportions, incorporating three junction types—L-shaped, T-shaped, and cross-shaped—that enhance spatial control and visibility;

Interconnected flat rooftops, forming a tactical secondary circulation layer—functioning as both an elevated “second street” for daily movement and a fallback defensive route during conflict.

Unlike the hierarchical, state-administered fortress systems of the Han Empire’s northern zone [

35], Guomari reflects a vernacular defensive adaptation shaped by religious cosmology and localized spatial intelligence.

This spatial logic transcends militaristic function and embodies a Tu cosmological worldview that sacralizes the environment—mountains are perceived as divine guardians, and rivers as ritual boundaries. Comparative analysis shares a hierarchical logic with Fujian tulou yet diverges significantly in spatial form and cultural encoding: tulou employ concentric clan-based structures, while Guomari adopts linear progression and rooftop connectivity shaped by Tibetan Buddhist spatial thought.

Climate adaptation is deeply embedded in Guomari’s construction. Thick rammed-earth walls, ranging from 0.6 to 4 m, and minimal window openings provide thermal mass and insulation against Qinghai’s cold, arid climate. The flat earthen rooftops, reinforced by compacted loess, resist strong winds and store daytime heat. Short-span timber beams support accessible terraces that serve both communal and defensive purposes, demonstrating the functional integration of local building techniques with environmental needs. These strategies are consistent with broader observations on the spatial organization and environmental adaptation patterns of Guomari village [

36].

Spatial measurement data further support Guomari’s defensive logic. The observed alley height-to-width ratio (~4.5:1) exceeds the 1:3 defensible space threshold [

37], reinforcing psychological deterrence. Courtyard forms—categorized into single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and fully-enclosed layouts—reflect local adaptations to terrain, ritual requirements, and livestock integration. For example, U-shaped courtyards with elevated prayer spaces echo Amdo monastic syntax, while integrated animal pens function as both pastoral spaces and early-warning systems. This form echoes the monastic spatial logic found in Amdo Tibetan dwellings, where U-shaped configurations structure both ritual access and enclosure [

38].

The fortress also displays pronounced material hybridity, illustrating negotiated identity at the frontier. Han-style timber frames support Tibetan prayer halls; Tu rammed-earth walls incorporate Salar lattice methods; and kitchen markings made with tsampa flour merge Han domestic rituals with Tibetan iconography. Interior tsampa-based wall murals and carved wooden components not only bear aesthetic and symbolic meaning but also serve functional purposes, repelling moisture and protecting earthen surfaces. These material layers reveal that Guomari is not merely a military site but a socio-cultural palimpsest where defense, ritual, and multiethnic symbolism converge. Among them, the carved woodblocks used for Buddhist scripture printing, along with appliqué Thangka and duixiu textiles, exemplify how traditional craftsmanship is spatially embedded within both domestic and sacred architecture—maintaining a living continuity between artistic expression, religious practice, and vernacular construction.

To ensure methodological transparency, the following measurements were adopted: architectural surveys used Bosch GLM4000 laser rangefinders (±5 cm); spatial data were digitized from MapWorld imagery (0.5 m resolution, ±1 m accuracy) and OpenStreetMap basemaps (approx. ±5 m accuracy); terrain analysis used the NASA SRTMGL1 DEM (30 m resolution). Key dimensions were cross-checked on-site, with a 10% validation sample confirming internal consistency between field data and CAD outputs.

These findings collectively demonstrate that Guomari fortress operates as a defensively resilient, climatically responsive, and culturally hybrid architectural system. Its spatial logic and material strategies provide a valuable framework for understanding how frontier communities negotiated security, ecology, and identity—offering practical reference for the conservation of other multiethnic fortified settlements in western China.

Overall, the architectural logic of Guomari fortress offers a paradigmatic case of how vernacular knowledge, spiritual symbolism, and embodied craft traditions converge in the spatial practices of frontier communities.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted detailed field surveys of two representative courtyard compounds in Guomari fortress and developed a typological framework of both defensive networks and courtyard forms. We identified a three-tiered defensive system: (1) natural terrain and enclosing walls; (2) labyrinthine alley networks with variable-width paths and irregular intersections; and (3) interconnected rooftops and courtyard-based defense units. In addition, we categorized all courtyards into four principal layouts—single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and fully-enclosed—each reflecting specific responses to spatial constraints, climatic conditions, and ritual practices. Together, these findings reveal how ecological adaptation—such as insulating rammed-earth walls and flat wind-resistant roofs—and Tu Buddhist cosmology—including mandala-like spatial organization and the ritual use of prayer flags—coalesce into a uniquely hybrid fortress architecture.

Implications for conservation include:

Technical: Retrofit rammed-earth walls with fiber-reinforced loam and monitor thermal performance;

Cultural: Document remaining oral traditions of courtyard defense and spiritual life.

Policy: Nominate Guomari for UNESCO’s Silk Roads serial listing to recognize its multi-ethnic heritage;

Stewardship: Establish routine maintenance protocols under local government oversight;

Digital Preservation: Develop a digital twin combining 3D terrain, CAD drawings, and material data for ongoing monitoring and virtual restoration.

However, this study is limited by its focus on two representative courtyard compounds within a single fortress, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Comparative analyses of the other three fortified settlements in Tongren County and neighboring regions are needed to evaluate the broader applicability of the three-tiered defensive model and typological framework. In addition, while four major courtyard types were identified earlier in the paper (single-line, L-shaped, U-shaped, and fully enclosed), the current research lacks sufficient empirical sampling across these categories to support a comparative typological matrix. Future work will involve field documentation of multiple examples from each courtyard type, allowing for the construction of a systematic table that includes spatial organization, elevation structure, and functional usage.

Furthermore, detailed quantitative structural assessments (e.g., load-bearing metrics, long-term material degradation) and thermal performance testing were not undertaken due to scope constraints. Subsequent research should incorporate these quantitative methods, as well as comparative metrics such as wall-thickness indices, alley-network connectivity ratios, and courtyard-function zoning schemes. Finally, the development of a dynamic digital-twin platform—integrating 3D terrain data, CAD drawings, and material properties—will allow simulation of environmental and structural stresses over time and support proactive conservation planning.

Guomari thus stands not only as an architectural relic but as a living archive of ecological defense, religious spatiality, traditional craftsmanship, and multiethnic adaptation—offering valuable insights for future heritage conservation in geopolitically sensitive regions.