1. Introduction

China’s rapid socio-economic growth is accompanied by an equally rapid—and spatially uneven—demographic shift toward old age. According to the Seventh National Population Census (2020), older adults (≥60 years) already account for 23.81% of the rural population and 15.82% of the urban population; the rural–urban gap widened from 1.2 percentage points in 2000 to 8.0 points in 2020 [

1]. This divergence is expected to grow, deepening the disparities in resources, services and infrastructure and putting disproportionate pressure on the public-space provisions in peri-urban villages [

2]. Many such villages now face hollowing-out, out-migration and functional imbalance, all of which erode the everyday living environment—particularly for older residents.

In the World Health Organization’s Age-Friendly Cities and Communities (AFCC) framework, accessible, safe and inclusive public space is a core condition for active ageing [

3]. The international scholarship has accordingly moved from macro-level indicator systems [

4] to micro-scale walkability audits [

5], co-creation design protocols [

6] and participatory “photo-voice” methods [

7], calling for evidence-based, replicable design guidelines [

8]. In the high-density East Asian setting, limited open space and rapidly shifting family structures subject older adults to “hidden exclusion” [

9] and intensify the need to retrofit transit nodes and large public buildings [

10].

Here, age-friendly public space is defined as a network of places that enable older people to participate in public life safely, decently and proactively through barrier-free access, convenient amenities, comfortable environments and socio-psychological support. The aim is not merely to remove physical barriers but also to satisfy social, recreational and empowerment needs.

The Chinese research initially concentrated on inclusive design in urban parks and squares [

11]. More recently, the attention has shifted to urban fringe villages, hybrid settlement units located at the urban–rural interface and characterised by fluid land use, population mixes and functional layouts [

12]. These villages absorb urban spill-over while retaining rural social networks, creating highly complex and uncertain demand–supply patterns in public space.

At the village scale, Su and Zhang proposed square retrofits based on behavioural observations [

13]; Wang explored the age-friendliness of village lanes using a need–ability model [

14]; and Liu and Wu designed a multi-tier open-space network for the “younger-old” [

15]. Yet most studies have been single-case and qualitative, lacking systematic spatial diagnostics or cross-case comparisons.

Space syntax quantifies configurational properties such as integration and intelligibility to explain pedestrian movement [

16]; its strong correlation with footfall has been confirmed through meta-analyses [

17] and applied to rural layout optimisations [

18], tourist village morphologies [

19] and historic settlement connectivity [

20]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) extracts the latent demand structures from questionnaire data and has been used for village landscape appraisals [

21], tourism-oriented planning [

22], green infrastructure evaluations [

23] and public service audits [

24]. However, very few studies have combined space syntax with an EFA to expose mismatches between older adults’ needs and spatial form—particularly in peri-urban contexts [

25,

26,

27].

As a result, three research gaps have emerged: gap 1 is the limited empirical evidence on the ageability of villages on the urban fringe; gap 2 is the lack of an integrated Spatial Syntax + Education for All (EFA) methodology linking the needs of older people to spatial form; and gap 3 is the lack of a complete workflow from the quantitative diagnosis to the design strategy.

To address these gaps, we propose an integrated analytical framework that couples space-syntax metrics (global integration and choice) with an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of residents’ perceptions. Space syntax provides the objective, network-scale measures that past single-case studies have lacked (gap 1), while the EFA converts subjective survey items into statistically validated latent constructs, overcoming the descriptive nature of earlier qualitative work (gap 2). By applying both tools to the same neighbourhood, we establish a data-driven link between the spatial configuration and perceived age-friendliness, thereby filling the empirical–conceptual disconnect identified in gap 3.

4. Discussion

4.1. Topological Restructuring Strategies

4.1.1. Multilevel Network Permeation

The multilevel permeation strategy raises the integration values of low-connectivity areas through micro-scale interventions, thereby improving their overall accessibility. In Liulin’s side alleys, poor connectivity restricts elders’ activity. Introducing short axial links to break visual and physical dead ends could significantly enhance reachability. These measures include inserting small connector paths or pedestrian walkways between alleys, shortening the travel distances between elderly activity nodes and ensuring that new links are fully barrier-free.

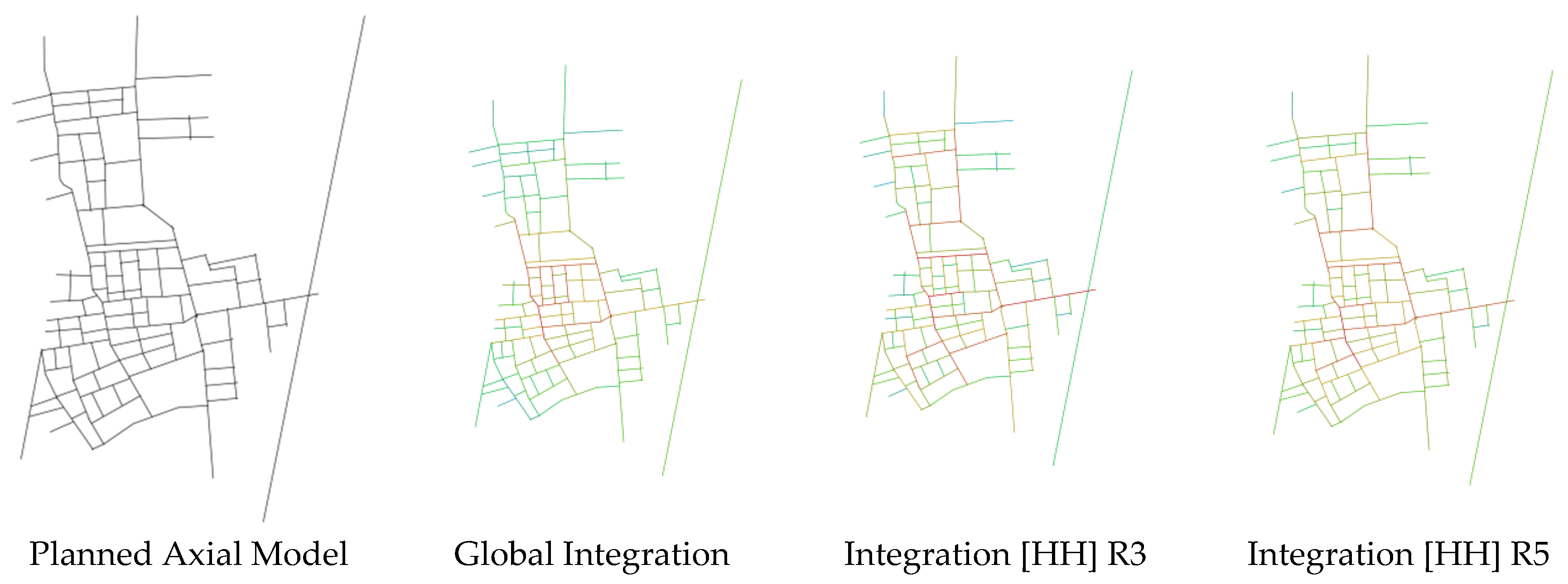

The post-plan analysis shows an across-the-board rise in integration (

Figure 7), with the main street and the secondary lanes improving most. The committee square now anchors a larger catchment, while the redesigned southern main street and the northern gateway exhibit higher centrality. The integration around the public car park has also increased, confirming the effectiveness of tying this node more tightly into the street grid (

Figure 8).

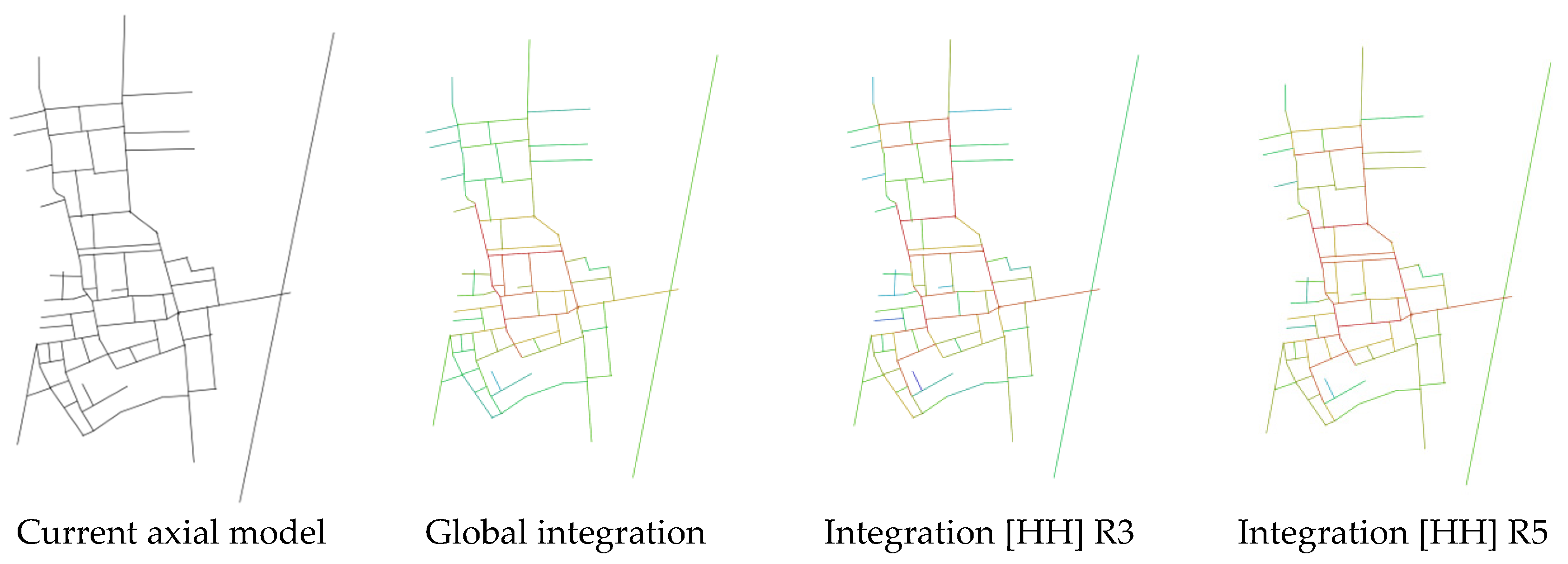

To enable a direct comparison between the pre- and post-intervention conditions, we applied the same spatial-syntax metrics (global integration and selectivity) to both time points: the current spatial integration analysis (

Figure 5) and the planned spatial integration analysis (

Figure 8). Concretely, the plan inserts four new pedestrian connectors with a total length of ≈180 m—about 7% of Liulin’s 2.5 km local street network—and adds roughly 420 m

2 of paved surface (≈3% of the existing public-space area). The output results are presented to allow readers to see how the intervention enhances the overall integration values.

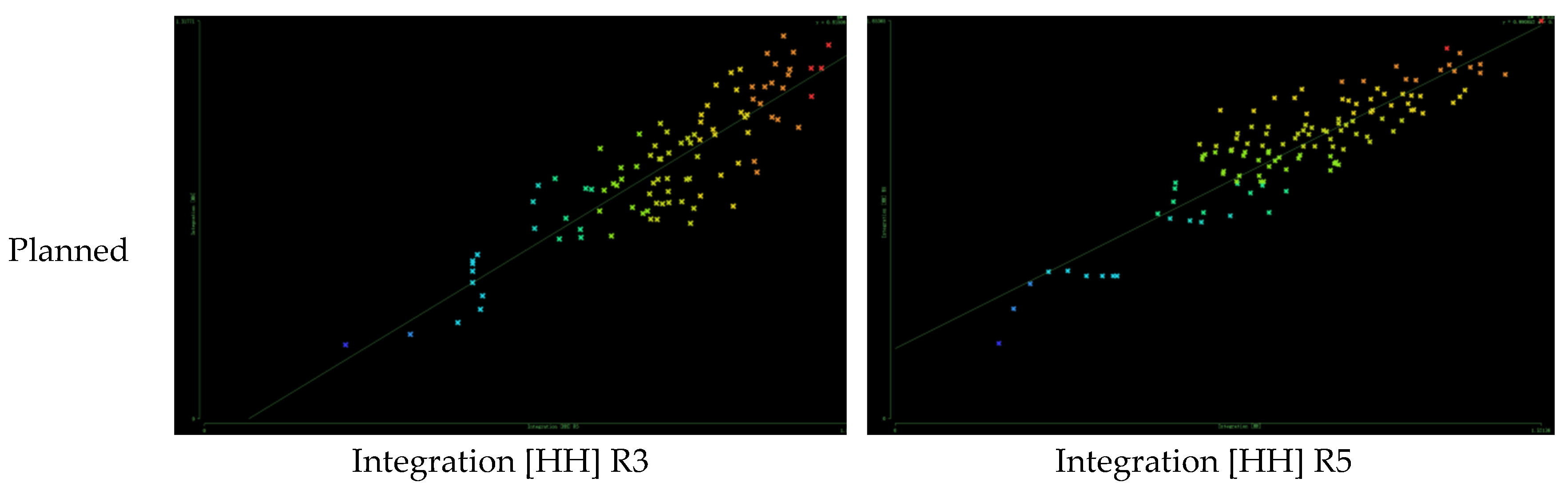

Strengthening the internal pedestrian links—especially between the main spine and the side lanes—significantly boosts the intelligibility (

Figure 9): the R

2 value for the global versus local integration (R3) climbs to 0.701, more than a 10% gain, and the R5–Rn fit reaches 0.815. Although still lower than the vehicle-oriented baseline, the walk-network logic is markedly clearer, signalling a shift toward pedestrian priority and improved age-friendliness.

In sum, Liulin’s pre-retrofit layout offered low intelligibility and fell short of older residents’ requirements for convenience, legibility and perceived security. The optimised scheme, by contrast, delivers a coherent, multi-scalar pedestrian hierarchy that privileges slow movement, shortens the trip chains and opens latent social micro-spaces along the way. These physical upgrades constitute the spatial bedrock upon which subsequent functional and programmatic layers of an age-friendly, sustainability-oriented public realm can be confidently assembled.

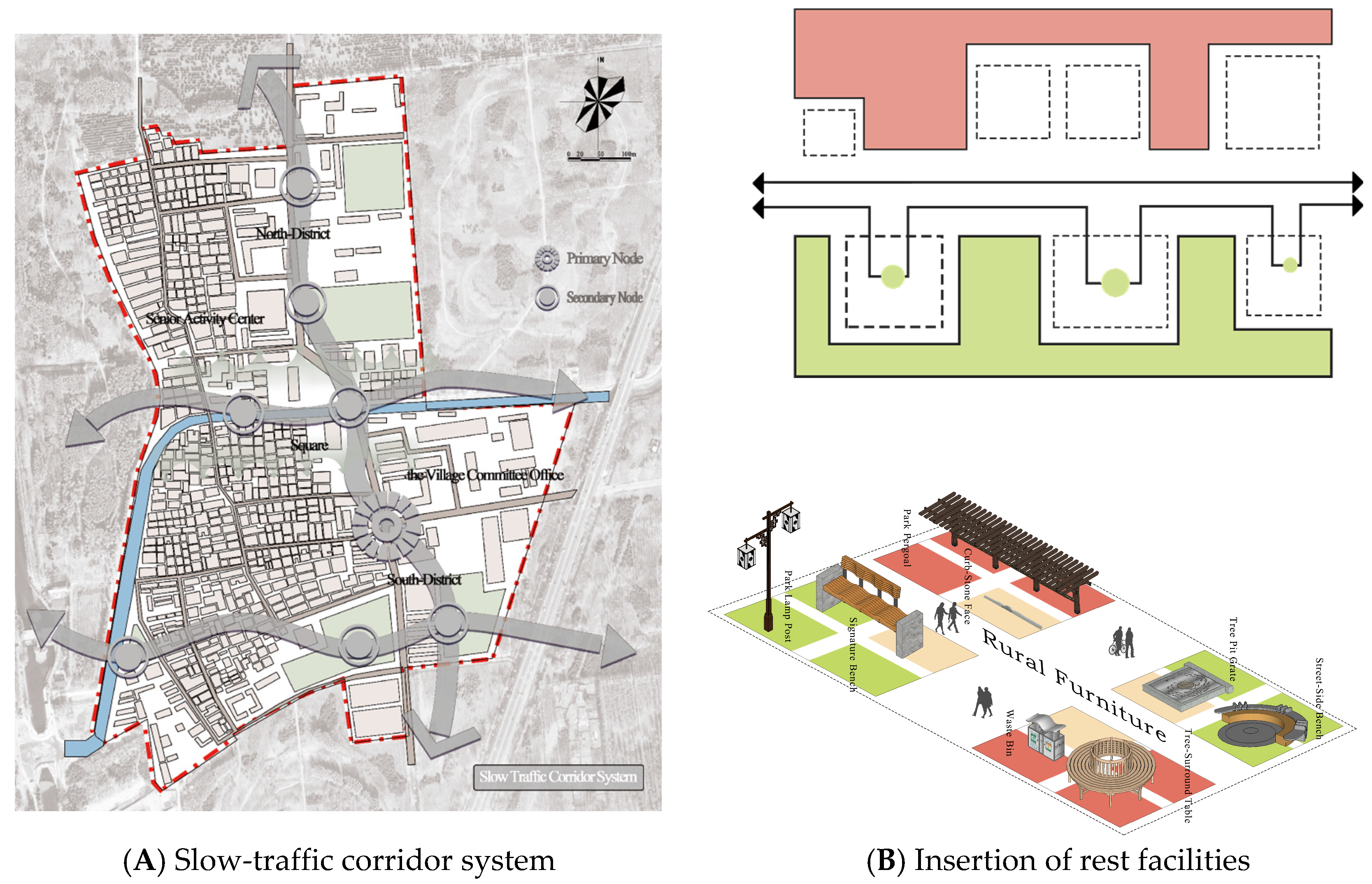

4.1.2. Corridor + Core Reinforcement

The “corridor-and-core” strategy centres on creating an elder-priority slow-movement network that stitches together scattered public-activity nodes into a safe, efficient pathway system. Because extended walking can be taxing for older adults, these gentle-pace corridors improve the mobility while offering ample rest areas and opportunities for social interaction (

Figure 10). In Liulin, key nodes—the village committee, the central plaza and the senior-activity centre—are linked by such slow-walk corridors, which are lined with benches, shade structures and other comfort features so that elders can move in a pleasant micro-climate. All routes are designed with low gradients and full barrier-free specifications to meet seniors’ mobility needs.

Scaling the corridor system faces three issues: (i) the mixed land tenure—memoranda with frontage tenants secure the rest node sites; (ii) upkeep—with 3% of kiosks requiring funds for cleaning and lamp replacements; and (iii) governance—a resident committee receives a one-page inspection checklist and a small annual grant to oversee maintenance.

To turn the “Corridor + Core” concept into an actionable design, four repeatable modules are proposed (as summarised in

Table 8):

(1) Rest nodes (every 80 m): L-shaped bench clusters with armrests, 1.5 m wheelchair clearance, a low drinking fountain and solar-powered USB outlets;

(2) Social pockets (≈60 m2 in a widened verge): Chess tables, a community notice board and a raised planter that residents can adopt for herbs/flowers;

(3) Micro-gym bays (≈40 m2): Senior-friendly steppers, two tai-chi wheels and a stretching rail, surfaced with permeable rubber;

(4) Pop-up kiosk pads (≈25 m2, modular power points): These host seasonal activities—tea stalls in summer, calligraphy booths during festivals and vaccination vans in winter.

Spacing these modules along the 420 m east–west corridor and at the two “cores” supplies rhythm, rest and programmed sociability.

4.2. Functional Adaptation Strategies

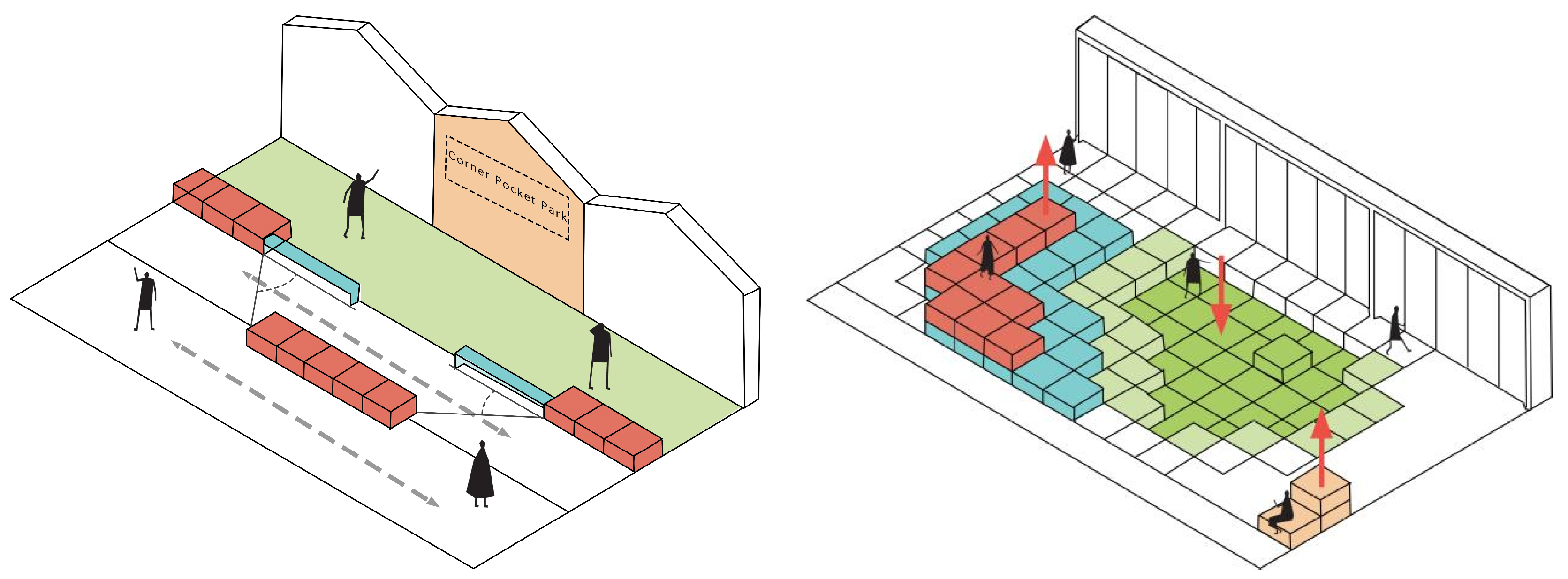

4.2.1. Modular Spatial Design

The modular space concept is guided by the principle of “care and enjoyment”. New health monitoring kiosks and rehabilitation rooms offer convenient medical management and therapy for older residents. Sunrooms are introduced as key functional spaces, supplying abundant daylight and a comfortable setting for everyday relaxation. Staggered building volumes allow different programme areas to be interlocked spatially, preserving functional independence while adding depth and usability to the plan. A preliminary bill-of-quantities shows that 60% off-site prefabrication cuts the on-site labour by about one-third compared with that for a masonry kiosk of an equal floor area.

Functional expansion enhances the versatility further by diversifying building forms, broadening public service offerings and activating courtyard spaces. Dedicated zones for social interaction, cultural events and elder health services ensure that the environment meets basic daily needs while also providing rich social and cultural experiences. By maximising variety and flexibility, the modular strategy raises the age-friendliness of public space, safeguards quality of life and supports social participation. Purpose-built subareas increase the operational efficiency and accommodate seniors’ health, social and leisure requirements better, thereby strengthening their reliance on—and engagement with—the public realm (

Figure 11). Each 3 m × 6 m module uses light-gauge steel frames and dry joints, allowing for on-site assembly or removal within one working day.

Such modularity amplifies every arm of sustainability. Socially, it safeguards dignity by letting seniors choose between quiet retreat and lively engagement; economically, it minimises sunk costs because modules can be added, re-skinned or relocated as needs evolve; and environmentally, it favours lightweight timber or recycled steel frames, demountable joints and photovoltaic shading canopies, reducing embodied carbon and facilitating end-of-life reuse. Purpose-built sub-areas—clearly zoned yet flexibly furnished—thus raise the overall age-friendliness of the public realm, boost the operational efficiency and strengthen older residents’ daily reliance on, and emotional attachment to, their neighbourhood open spaces. Each module is a bolt-on steel frame with plug-in panels that can be re-skinned or repurposed (e.g., tea kiosk → reading nook) in under two hours.

The modular space design solution is a conceptual top-level prototype based on spatial syntactic diagnostics and has not yet been validated on site with elderly residents. In the next phase, the programme will be evaluated and iterated through two co-creation workshops with ≥20 residents over 60 years old and immersive VR roaming.

We conclude by noting that the modular space’s design remains untested by its end users. Future work will conduct the planned workshops and VR evaluations to assess its usability and perceived benefits and improve the programme accordingly.

Scaling these modular units to other peri-urban villages will face at least three hurdles: (1) the heterogeneity of land tenure—the plot boundaries and informal add-ons differ widely, so the modules must be flexible between 2 m and 4 m widths and sit on both collective and privately leased land; (2) the local governance capacity—village committees vary in their technical skills and budget, calling for a simplified “tool-kit” manual and a phased co-funding model; (3) life-cycle operation and maintenance—cleaning, lighting and minor repairs require an agreed caretaker scheme, which could be covered by user committees or micro-contracts with retiree residents.

Three lines of enquiry are planned: (1) a multi-site pilot deploying three prototype modules in at least two additional peri-urban villages and comparing the pre/post scores; (2) adaptability studies, documenting the seasonal re-purposing of modules (e.g., vegetable swaps in spring, calligraphy booths at festival time) and noting design tweaks that aid or hinder such changes; and (3) a cost–benefit analysis, weighing the capital and maintenance outlays against the measured social gains to build an investment case for wider rollout.

4.2.2. Dynamic Mixed Use

Dynamic mixed use is vital to Liulin’s public-space scheme. By shifting their functions over the day, spaces can meet elders’ emotional and social needs better while boosting their utilisation and cultural identity. The programming begins with the real, everyday requirements and aims to foster a sense of belonging. During daylight hours, plazas can operate as marketplaces or service hubs, offering fresh produce, household goods and pop-up information or health-check stations—basic supports that also reinforce mutual aid and security.

The village committee should act not only as spatial manager but also as social catalyst, organising periodic events that strengthen cohesion and cultural recognition, thereby deepening residents’ attachment to the community.

After dark, the same areas can be converted into dance plazas. Group dancing is both exercise and a key social outlet; a designated area lets elders keep fit while nurturing ties and inter-generational exchange. Additional nighttime zones can host dancing, singing or small gatherings, enriching the social options and encouraging participation.

Such time-based flexibility heightens spatial efficiency and more fully addresses emotional needs. By dynamically adjusting its functions, older residents experience stronger cultural affiliation and greater social engagement, ultimately enhancing their quality of life and delivering comprehensive, age-responsive care (

Figure 12).

4.3. Transferability of the Findings

Liulin Village is representative in three respects: (1) “morphological type”, a grid-cum-alley layout inherited from pre-urban farmland consolidation; (2) the “socio-economic mix”, ageing long-term residents plus an influx of migrant renters; and (3) the “policy environment”, where the village is subject to the same “incremental improvement” funding scheme applied across Beijing’s urban fringe. For these reasons, the diagnostic workflow (space syntax + EFA) and the “corridor + core”/modular interventions are likely to translate to many peri-urban settings in North China.

Two factors could limit their direct transfer: the “local governance capacity”, where weaker village committees might struggle with maintenance-heavy features, and the “demographic mix”, since a younger or tourism-oriented settlement would prioritise different activity programmes. Future applications should therefore (i) adapt the governance toolkit to the local institutional strengths and (ii) re-run the EFA using site-specific survey items before finalising the design modules. Comparative studies in other Chinese provinces, as well as in rapidly peri-urbanising regions of Southeast Asia and Latin America, would be invaluable for testing the framework’s broader applicability.

In practical terms, the transferability depends on the following:

Factors that help adoption: The similar grid-plus-alley morphology common in North China fringe villages; nationwide “incremental improvement” funding that supports small plug-in modules; and the rapid population ageing (≥20% aged 60+) in many peri-urban areas;

Factors that may constrain adoption: Weaker local governance, where maintenance budgets and resident committees are harder to sustain, and differing land-tenure patterns (e.g., scattered private plots) that limit corridor continuity.

Future applications should therefore adapt the governance toolkit to the institutional capacity and secure tenure agreements before the selection of the final layout.

5. Conclusions

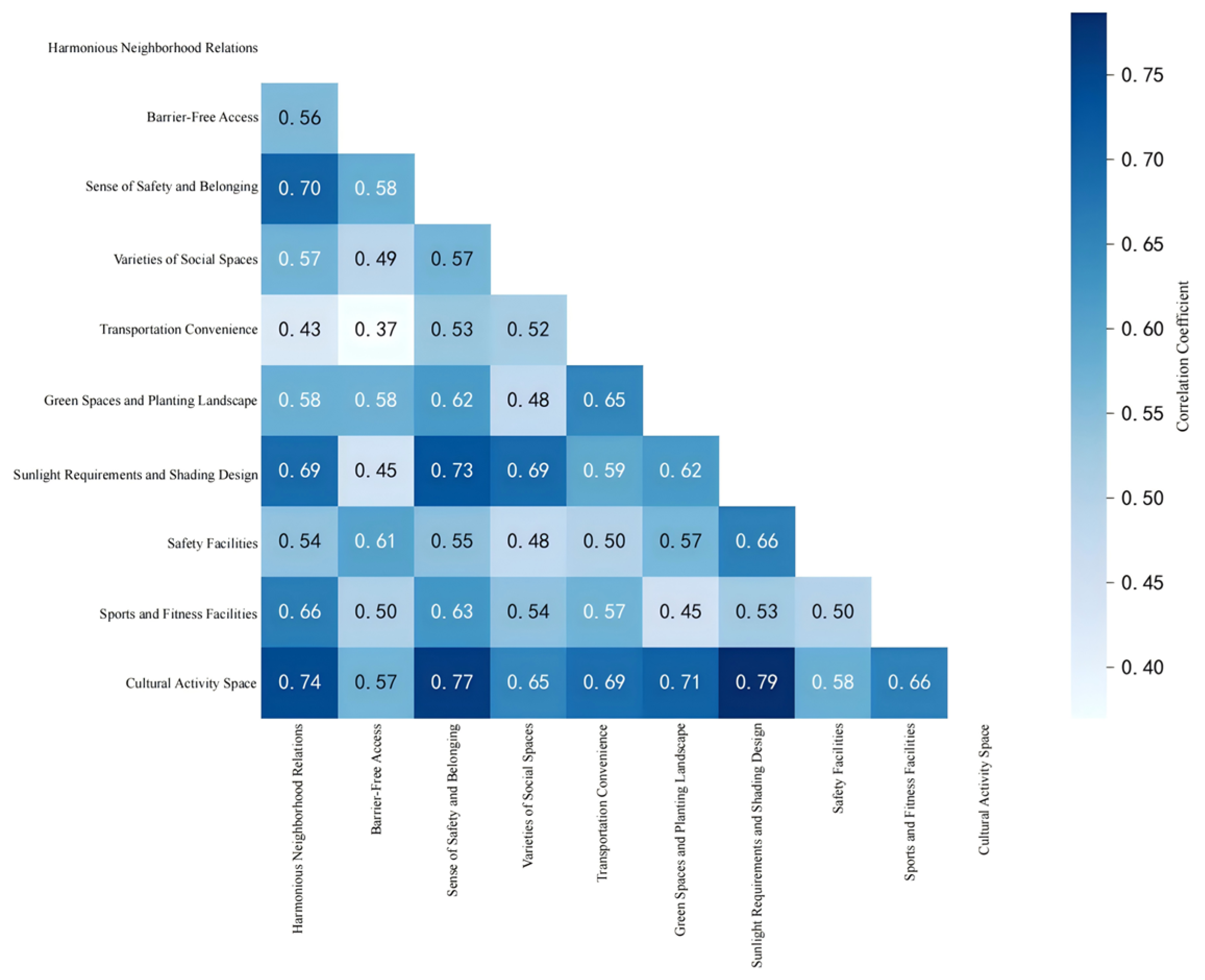

Using space syntax and an exploratory factor analysis, this study identified the principal shortcomings in the age-friendliness of Liulin Village’s public realm. The space-syntax results show a clear mismatch between the spatial layout and elders’ needs: high-integration zones are functionally mono-used—the supermarket frontage displaces seating and rest areas—while low-connectivity alleys suffer from visual enclosure and safety deficits that suppress activity. The factor analysis further reveals four coupled dimensions—personal convenience; socialisation and belonging; environmental and landscape; and activity function—with personal convenience exerting the greatest influence on elders’ behaviour. Together, these findings indicate that age-friendly retrofitting at the urban fringe must advance along two tracks: spatial repair, aimed at improving accessibility and connectivity, and functional optimisation, aimed at diversifying its uses and raising its age-responsive quality.

Building on these insights, this research also highlights broader sustainability dividends. Spatial repair through additional micro-links and shaded “corridor–core” loops shortens walking distances and encourages active mobility, thereby lowering transport-related emissions and reinforcing climate-adaptation goals. Functional diversification—particularly time-shared programming of plazas for morning markets, midday health services and evening leisure—maximises the land use efficiency and catalyses community micro-economies without new land uptake. By converting under-utilised edges into socially animated fronts, the proposed interventions strengthen weak-tie social capital and enhance perceived safety, advancing the social sustainability pillar alongside environmental and economic gains.

This study has several limitations. First, it does not differentiate between the needs of the “older-old” and “younger-old”, who vary markedly in their health, mobility and social demands. Future work should disaggregate these cohorts and integrate physiological data—such as gait speed or heat stress tolerance—to refine the design guidance. Second, the analysis centres on the spatial layout and function, giving limited attention to external factors such as social policy, land-tenure arrangements and cultural practices. Subsequent research should therefore incorporate institutional and ethnographic perspectives, as well as longitudinal monitoring, to achieve more holistic and durable upgrading of age-friendly spaces across diverse peri-urban contexts.