1. Introduction

The housing challenges faced by cities around the world are deeply rooted in historical economic and social processes that exacerbate inequality in access to housing. In urban contexts marked by rapid growth, economic crises, and fragmented public policies, the struggle for decent housing becomes a central issue in both urban planning and social policymaking. Social movements emerge as a response to these crises, coordinating demands for housing justice and the Right to the City—a concept widely debated and reaffirmed in contemporary urban theory [

1,

2].

Originally introduced by Henri Lefebvre in 1968 [

1], the concept of the Right to the City redefines urban space as a social product that should be accessible and collectively shaped by all citizens, particularly marginalized groups. This right goes beyond physical access to embrace active participation in the production and appropriation of urban space, challenging the exclusionary logic of capitalism [

1]. The Right to the City and the pursuit of spatial justice are closely linked to the equitable redistribution of resources, infrastructure, and opportunities to meet collective needs and promote a more just and inclusive society [

3].

The municipality of Diadema, located in the São Paulo Metropolitan Region (RMSP), stands out as one of the most pioneering experiences in Brazil in terms of addressing socio-spatial inequalities through participatory urban policies. Beginning in the 1990s, in response to the proliferation of informal settlements and growing demands from housing movements, the city implemented the Special Zones of Social Interest (AEIS)—a local initiative that anticipated key urban planning instruments later institutionalized by the City Statute in 2001.

This municipal policy not only recognized the social function of property but also enabled the allocation of underutilized urban land for self-managed social housing initiatives, promoting a model of planning led by grassroots associations.

The aim of this study is to analyze the role of housing movement associations in Diadema, focusing on the development of social interest housing developments (LHISs). These projects, financed by the member families themselves and organized autonomously, emerged as a response to the lack of public investment in housing, constituting an innovative and transformative model. The study also assesses the impact of the AEIS instrument in promoting housing inclusion and spatial justice.

While there is extensive literature on housing policy in Brazil, few studies provide an in-depth empirical analysis of the concrete application of AEIS in self-managed housing projects led by community associations. This study seeks to fill that gap by documenting and analyzing how the AEIS tool was used in Diadema to implement participatory planning and realize the Right to the City in practice.

The central research question guiding this study is: how did housing movement associations in Diadema use participatory planning instruments, particularly the AEIS, to claim and materialize the Right to the City? This question frames the empirical analysis and is anchored in critical urban theory, particularly the works of Lefebvre, Harvey, and Soja, which address the spatial dynamics of power, justice, and resistance.

The article is structured into six sections. The Introduction contextualizes the study and outlines its main objectives and contributions. The Materials and Methods section details the mixed-methods approach adopted, which combines documentary analysis, archival research, and geospatial techniques. The Results section explores the case of Diadema, focusing on the implementation of AEIS and the development of LHISs between 1996 and 2013, highlighting both achievements and ongoing challenges. In the Discussion, these findings are critically examined in light of theoretical frameworks and participatory urban policies. The Final Considerations synthesize key lessons from the Diadema experience, emphasizing the role of social movements in fostering more inclusive and equitable urban environments. Lastly, the References section provides the bibliographic foundation that supports the study.

The analysis furthers the debate on inclusive urbanization and underscores the transformative potential of social movements for constructing just and equitable cities.

2. Materials and Methods

This research adopts a qualitative case study approach, centered on the analysis of documentary, visual, and empirical materials. Rather than offering a descriptive or technical account, the study seeks to interpret how bottom-up planning practices, supported by institutional innovations, contributed to the realization of the Right to the City in Diadema between 1996 and 2013.

The methodological procedures are structured as follows:

- i.

Bibliographic Review:

A review of the academic and technical literature was conducted to provide the theoretical and historical grounding for the research. Key references in critical urban theory and housing policy—including Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey, Edward Soja, Raquel Rolnik, and Nabil Bonduki—were mobilized to frame the Diadema case within broader debates on spatial justice, collective action, and urban governance.

- ii.

Documentary and Archival Research:

The core of the methodology consists of a systematic analysis of unpublished and previously unsystematized documents, including municipal archives and internal materials from housing movement associations. From the city government, the research examined urban development plans, zoning laws, technical reports, legal instruments, and administrative records. From the associations, materials such as meeting minutes, internal communications, project documentation, and self-management records were analyzed. These documents were selected based on their relevance to the legal, institutional, and operational dimensions of AEIS-1 and LHIS implementation. Access to some documents was limited by incomplete or deteriorated archives, particularly in older administrative records. In these cases, data triangulation was conducted using secondary sources and interviews with key actors involved in the projects.

- iii.

Visual and Iconographic Survey:

Visual materials were employed not only for illustrative purposes but as analytical tools to reconstruct the spatial and temporal dimensions of the urban transformation. Aerial photographs, cartographic material, and on-site photographs were used to generate schematic diagrams and comparative images of the LHIS territories. The research utilized QGIS software (version 3.40.7) for visual data processing, including georeferencing and overlay of aerial imagery (Google Earth) and official orthophotos from the municipality of Diadema for the years 1996, 2000, 2009, and 2013. The selection of these years aimed to capture key stages in the evolution of the housing projects. Despite resolution limitations in some older images, this visual survey allowed for a diachronic analysis of spatial occupation patterns and urban form.

This integrated methodology, grounded in documentary reconstruction, visual intepretation, and spatial comparison, offers analytical depth and interpretive clarity. By connecting institutional processes, community practices, and spatial transfomations, the study contributes to the understanding of how grassroots urbanism can shape housing policy and spatial justice agendas in contexts of limited state capacity.

3. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in the perspective of critical urban theory, particularly the concept of the Right to the City as developed by Henri Lefebvre and later expanded by David Harvey [

2,

3]. According to this framework, the city is not merely a physical space, but a social product shaped by power relations and collective struggles. Harvey emphasizes the right to shape the processes of urbanization, positioning grassroots movements as key actors in resisting the commodification of urban space.

The notion of spatial justice, as articulated by Edward Soja [

4], also informs this analysis. This author argues that spatial organization reflects and reinforces social hierarchies, and that urban space is both a medium and outcome of political struggle. These perspectives frame urban planning not as a neutral or technical process, but as a contested field shaped by political interests and social agency.

In the Brazilian context, this study engages with the contributions of scholars such as Raquel Rolnik [

5], Erminia Maricato [

6], and Nabil Bonduki [

7,

8,

9]. These authors have examined the contradictions of housing policies in Brazil, emphasizing the role of self-managed housing initiatives and the persistent inequalities in access to land and urban infrastructure. Their work underscores the importance of understanding how institutional tools interact with grassroots mobilization to produce more inclusive urban spaces.

This theoretical foundation informs both the methodological approach and the interpretation of the empirical findings presented in this article, particularly in analyzing the political dynamics behind social interest housing developments (LHISs) and the application of Special Zones of Social Interest (AEISs) in the city of Diadema.

This discussion can also be expanded through the lens of land inequality and social justice. Spatial justice is a key element for achieving urban equity [

4]. The Right to the City may also be interpreted as a political movement that challenges existing power structures and seeks to democratize urban life by promoting the inclusion of all populations in decision-making processes and in the use and production of urban space [

10]. Another perspective suggests that the Right to the City should function as a form of resistance against the commodification of urban space, advancing practices that prioritize collective interests over market logics [

11]. These theoretical perspectives offer a solid framework for understanding contemporary urban dynamics and guiding practices that reduce social and spatial inequalities.

At the international level, the concept of the Right to the City has inspired a wide range of initiatives, particularly in Latin America and the Global South, where traditions of social mobilization have contributed to innovative planning strategies. In Uruguay, housing cooperatives organized through self-management and mutual aid, such as those developed under the FUCVAM model, have promoted inclusive and sustainable access to housing through collective action, and have been internationally recognized as a successful model of social production of habitat. In Colombia, the Program for Integral Neighborhood Improvement (PMIB) in Medellín exemplifies participatory approaches to slum upgrading and integration of informal settlements into the formal urban fabric. In Ecuador, regularization programs combined with community participation also offer valuable lessons in legal–spatial integration [

12]. UN-Habitat’s Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme (PSUP) highlights these Latin American experiences as leading examples of inclusive urban policy in contexts of inequality. In Africa, programs such as the slum upgrading efforts in Kibera, Kenya, demonstrate how bottom-up urban regeneration can contribute to spatial justice despite limited institutional capacity [

13]. The resilience literature has emphasized the need for multiscale and multicriteria approaches to understand complex urban systems and their vulnerabilities, particularly in planning for informal urbanization and social housing [

14]. In Europe, movements such as the Right to the City Alliance in Berlin and municipal housing programs in Barcelona reflect similar concerns with democratic urban governance and housing justice. Despite their differences, all of these experiences highlight the persistent challenges of financialization, fragmented governance, and insufficient public investment—reaffirming the urgency of coordinated strategies among grassroots organizations, professionals, and governments.

In Brazil, the struggle for the Right to the City has been led by popular housing movements that emerged in response to systemic exclusion from land and decent housing. Before the emergence of Diadema as a reference in self-managed housing policy, important precedents in participatory urban planning and land regularization had already shaped Brazil’s policy landscape. One of the most emblematic cases is the PREZEIS (Special Zones of Social Interest Plans) initiated in Recife in the early 1980s. These plans institutionalized community participation in land use regulation and became a national reference for integrating informal settlements into the legal and urban fabric [

15], and showed how the PREZEIS challenged technocratic planning approaches and acknowledged the role of popular agency in shaping urban territories. Other pioneering experiences include the slum upgrading programs in Belo Horizonte and early zoning initiatives in São Paulo that introduced special zones for social housing before the AEISs were formalized. These cases built a technical, legal, and political repertoire that influenced later programs like those implemented in Diadema.

Since the 1980s, these movements have achieved significant victories, culminating in the 1988 Federal Constitution, which for the first time introduced a chapter on urban policy (Articles 182 and 183). These articles established the principles of the social function of property and the city, consolidating the legal foundation for inclusive and participatory planning. Research [

5,

16] has demonstrated how these movements have influenced the creation of urban instruments that combine land regularization with social justice. Self-management is seen as an essential element for guaranteeing the Right to the City, enabling housing projects led by communities without relying solely on public investment [

6,

7,

8].

Self-management and self-building also play a central role in this process [

17,

18]. These practices reinforce the autonomy of residents in shaping their living environments, promoting not only access to housing but also social and spatial integration. In addition to responding to the limitations of state housing provision, these processes foster community empowerment and urban transformation, allowing residents to adapt living spaces to their specific needs. As such, this approach constitutes more than a technical alternative —it represents a political strategy of resistance and social transformation. These experiences illustrate how community organization can address the gaps left by the state and create alternative solutions to mitigate the housing deficit and strengthen the social fabric.

It is within this broader historical and theoretical context that the case of Diadema is situated. The following section presents the political and institutional trajectory that led to the implementation of AEIS in the municipality, as well as the strategic role played by housing associations in advancing self-managed and self-financed LHIS projects.

4. Results: Collective Production of Urban Space in Diadema, Brazil

The implementation of the Special Areas of Social Interest (AEISs) in Diadema in the 1990s gave rise to an innovative experience of collectively producing urban space in Brazil, where civil society organizations assumed central roles in housing production. This case reflects broader dynamics of participatory urbanism and grassroots planning in Latin America. As social movements reorganized into formalized associations, they gained legal autonomy to deal with land, run projects, and oversee housing developments.

4.1. Diadema, Social Mobilization, and Movement for Decent Housing

Diadema, located in the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (RMSP), is an integral part of the urban conglomerate known as ABCD Paulista (

Figure 1). This subregion, situated within the RMSP, comprises seven cities—Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, São Caetano do Sul, Diadema, Mauá, Ribeirão Pires, and Rio Grande da Serra—and has a combined population of approximately 2 million. The region is a key industrial hub in Brazil, particularly noted for its strong presence in automobile manufacturing. Covering an area of 30.7 km

2, of which 7 km

2 is designated as a protected area of mangroves along the Billings Reservoir, the city of Diadema has a total population of 393,237 [

19] and a demographic density of 12,795.69 residents per km

2, making it one of the most densely populated cities in the country.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Diadema attracted hundreds of workers due to local industrial expansion and the growth of neighboring cities such as São Bernardo do Campo and Santo André. However, this rapid increase in the local population was not accompanied by adequate housing policies, resulting in the spread of favelas.

The zoning policies implemented in the 1960s and 1970s prioritized the use of land for industrial purposes, relegating low-income housing to secondary importance. Only a few small residential areas were dedicated to high-income families in Diadema, leaving the newly arrived low-income population with no formal housing options [

20]. This situation led families to settle public and private areas, worsening the housing deficit and exacerbating social tensions in the city. Between 1960 and 1990, the population of Diadema soared from 12,038 to 300,000 people, a growth rate directly matched by the process of urban sprawl [

21].

The lack of essential infrastructure, such as mains water, sewage, and electricity, contributed to the spread of irregular settlements, leading to a scenario of housing vulnerability. The 1970s and 80s marked a period of peak urban expansion for Diadema, with the city becoming a hub of mobilization for decent housing in the RMSP.

The 1980s was a milestone decade for the organization and strengthening of housing movement associations in Diadema. These grassroots groups emerged as a direct response to the precarious conditions faced by populations in informal areas and the lack of inclusive public policies. Drawing on principles of community organization, the movements pressured public authorities for housing policies that secured the Right to the City, defining paths for collective demographic access to the benefits of the urban space [

1].

One of the most representative episodes of this mobilization was the “Battle of the Socialist Vila” in 1990. Amid the settlement of a land plot covering 2400 m

2 in the district of Inamar, around 2000 families were subjected to violent eviction by the Military Police. The clash ended with two deaths and numerous injuries, resulting in the housing movements stepping up political efforts to press city authorities into devising urban policies to address the housing shortage [

21].

Besides fighting for land tenure regularization and the urbanization of favelas, the housing movements broadened their agendas in the 1980s. Demands such as the need for permanent housing for tenant families were prioritized, exposing the complexity of the city’s housing problem. This transition was accompanied by the creation of new organizational strategies, such as the establishment of housing associations to oversee the planning and execution of housing projects. Bolstering these associations was essential to enabling the development of social interest housing (HIS) in Diadema, promoting self-management and self-financing as practical solutions to the housing crisis. These movements not only catered to more immediate housing needs but also played a crucial role in transforming the urban fabric. The struggle for housing in Diadema, symbolized by episodes like the ‘Battle of the Socialist Neighborhood’, represents a prime example of social mobilization to achieve spatial justice.

4.2. Special Areas of Social Interest (AEIS) and Development of Housing Projects by Associations

Special Areas of Social Interest (AEISs), implemented in Diadema from 1994 onwards, constituted a major milestone in local urban planning, and were directly driven by the mobilization of housing movement associations that had been growing since the 1980s. These organizations played an essential role in devising innovative housing policies, such as the Program for Urbanizing Favelas and Granting of Rights to Land Use (CDRU), which secured the rights of favela dwellers to occupy the site of their settlements through the granting of land use concessions of up to 90 years [

22].

Inspired by earlier experiences in other Brazilian cities, including the creation of the Program for Regularizing Special Zones of Social Interest (PREZEIS) in Recife in the early 1980s and the implementation of the Program for Regularizing Favelas (PRO-FAVELA) in Belo Horizonte shortly thereafter, which sought to regularize existing favela settlements, the AEISs in Diadema went a step further by including vacant and underutilized land plots in the urban policy, creating a strategic land reserve for developing social interest housing.

The process of drawing up the 1994 Master Plan was highly participatory, involving over 100 meetings throughout 1993 between representatives of the city authorities, social movements, and community leaders [

12]. The proposed text for the 1994 Master Plan defined AEIS-1 as: vacant, underutilized or unused lands necessary for implementing social interest housing developments and with areas set aside for community facilities in accordance with the Urbanization Plan [

23].

During these discussions, the land plots identified as vacant or underutilized areas were demarcated as AEIS-1, earmarked solely for developing social interest housing (HIS). Throughout the course of the participatory process which gave rise to the 1994 Master Plan, 2.85% of the total Diadema land area was designated as AEIS-1, corresponding to 0.87 km

2 dedicated to these housing developments [

24].

Besides creating a reserve of land plots for social housing, the AEIS introduced specific parameters governing the use and occupation of the land. This innovative approach was grounded in the Lehmann Law (Federal Law no. 6.766/79), which sets forth guidelines for specific urban projects, allowing higher density housing and infrastructure cost savings. Direct negotiation between housing associations, public authorities, and land owners resulted in sale values up to 35% below market rates, making the land affordable for low-income families.

The first housing project implemented under the AEIS-1 model was the Rosa Luxemburgo LHIS, developed by the Oeste de Diadema Association in 1996. This development project, akin to many others, was characterized by self-management and self-financing, with all stages funded directly by the member families.

4.3. Development of Self-Financed LHISs in Diadema

The scope of the present study extends only to those associations which developed LHISs in Diadema following the introduction of AEIS-1 in 1994 and the establishment of housing movement associations in the city. In total, 27 social interest housing developments (LHISs) were implemented between 1996 and 2013, comprising 5244 lots. Execution was led by housing movement associations through the adoption of self-management and self-financing. The number of LHISs and lots developed by the associations between 1996 and 2013 is presented in

Table 1 below:

The geospatialization of data from

Table 1 is depicted in

Figure 2, showing the LHISs developed by the associations using the self-financing model between 1996 and 2013.

Analysis of the LHIS implementation data reveals that the years spanning from 1996 to 2009 marked a period of intense execution for the associations in Diadema, driven by the high demand of members and a lack of public funding for building vertical social interest housing developments (EHISvs).

The 1996–2009 period can be divided into two: the first period, from 1996 to 2000, corresponds to a phase in which Diadema was the only city in Brazil to have demarcated AEISs on vacant or underutilized land. This policy instrument was defined in the 1994 Master Plan, refined in the revised plan in 1998, and again in the revised Zoning Law in 1999, underscoring the pioneering nature and experience of Diadema. A total of 13 LHISs were implemented over the period.

The second period, from 2001 to 2009, was marked by the consolidation of the Special Zones of Social Interest (ZEISs)—denominated AEISs in Diadema—under the City Statute, Law no. 10.257, of July 2001. In this context, the cities of São Paulo, Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, among others, incorporated this instrument into their Master Plans for application to vacant or underutilized properties. From 2010 onwards, there was a significant decline in the implementation of housing developments from 25 LHISs during 1996–2009, to only 2 between 2010 and 2013. This drop can be explained by two main factors.

The first factor involved the depletion of large land plots from the stock within AEIS-1 in the city. The second factor pertained to the introduction of the “Minha Casa, Minha Vida” (My House, My Life) program in 2009, which created conditions for associations to access lines of credit for property in the “entities” modality, thereby enabling the financing and construction of multi-story developments.

The program allowed associations to negotiate and acquire smaller land plots and focus on building apartment blocks within condominiums, replicating the build model of Minha Casa, Minha Vida throughout Brazil. The LHIS developed during each of the cited time periods. Between 1996 and 2000, 13 self-managed social interest housing (LHIS) projects were developed: Rosa Luxemburgo, Jardim Rosinha, Antônio Piranga, José Bonifácio I & II, Vera Cruz, Júpiter, Ana Rosa, Vila Santa, AMUHADI I and II, Afonso Monteiro, Nova Conceição, and AMAPRE—Caramuru. In the following period, from 2001 to 2009, 12 additional projects were implemented: Divina Pereira, Inamar, Karl Huller (Canhema I), Henrique de Léo, Bororós, Fagundes de Oliveira, Bilac, Centro, Recanto Feliz (Gema), Ana Maria, Álvares Cabral, and Caramuru. Between 2010 and 2013, two new developments were built: Nossa Senhora das Graças and Canhema II.

This chronological distribution highlights the continued role of housing associations and the flexibility of the self-managed model to respond to shifting urban dynamics and public housing policies. The different LHIS produced over the period are listed in

Figure 3. The map was elaborated by the author based on data obtained from building permits and from comparative analysis of aerial and historical photographs.

4.3.1. Design and Built Environment in LHIS

The involvement of professionals from the fields of architecture and engineering was fundamental for implementing the social interest housing developments (LHISs). These professionals engaged by the associations were charged with developing designs for parceling the land and implementing the LHIS. The professionals also devised architectural designs for the housing units, each design discussed and adapted to the needs of the families, who subsequently constructed their dwellings through the model of self-build with technical assistance. Reports present the AMAPRE experience of implementing the AMAPRE I LHIS where “the association engaged the architect Selma Scarambone to draw up the design” [

25].

The LHIS projects in Diadema were developed through a combination of assisted self-construction and community-led design. Most units followed a modular system, with reinforced foundations to allow for vertical expansion up to three stories. Lot sizes were standardized at approximately 42 m2, promoting compact and dense occupation compatible with existing infrastructure. Construction techniques prioritized low-cost materials and incremental building strategies, enabling residents to adapt homes according to evolving family needs. Compared to informal settlements, these developments exhibit improved alignment of streets, better access to light and ventilation, and a more regular urban morphology, albeit with great diversity in architectural outcomes.

The Recanto Feliz LHIS is an example of the role of these professionals. This LHIS was developed by Selma in collaboration with the architect Roberto Neri, with Selma overseeing the project for implementing the LHIS while Roberto designed the housing units.

Figure 4 depicts the design plan of the Recanto Feliz LHIS, covering a land area of 24,805.00 m

2 which, up until the 2000s, had housed a commercial enterprise. Following negotiation for and purchase of the land by the Pró Moradia e Liberdade Association, the area was subdivided into 220 lots, including 02 green spaces, 01 institutional area, and 01 leisure space.

The smaller size lots of 42 m

2, as opposed to the 125 m

2 stipulated by Federal Law and in other areas of the city, allowed higher density housing for the LHIS and the implementation of a larger number of lots. Consequently, the associations were able to house more families per housing block, with commensurately lower land and infrastructure costs for member families served. One of the formats of the housing units designed for the Recanto Feliz LHIS is shown in

Figure 5.

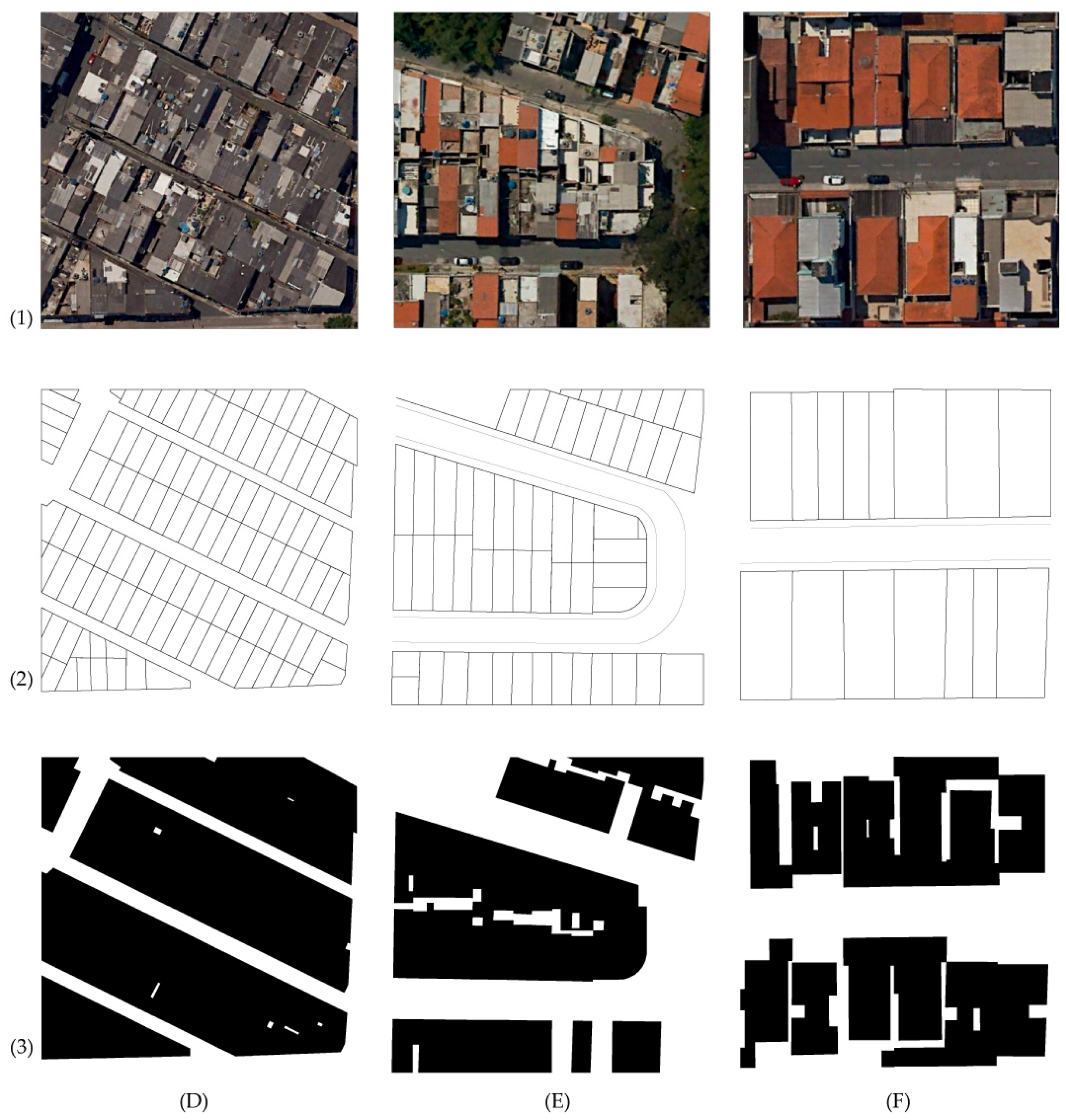

Scheme 1, developed by the authors, provides an urban fabric analysis comparing sections of the city of Diadema and the built environment of the LHIS (Low-Income Housing Scheme). The scheme is divided into three rows (1, 2, and 3) and three columns (D, E, and F). For greater accuracy, all sections were cropped to 60 × 60 m, with the same altitude and framing used for image extraction, and a uniform project scale was applied.

The rows in the scheme represent the different layers used for urban fabric analysis: Row (1) displays aerial photographs of the sections; Row (2) presents the division of plots, blocks, and the road system; Row (3) illustrates the relationship between built and open spaces.

In

Scheme 1, (D) depicts the disaggregation of a section of the Vila Olinda Favela, urbanized in the 1990s with a minimum plot size of 42 m

2. Part of the urbanization works in the central area was carried out through a coordinated mutual aid system. The houses were self-built by residents, some of whom received qualified technical assistance. The area exhibits high-density construction, with nearly 100% of buildings lacking adequate space for ventilation or natural lighting. Another notable feature is the road system, consisting of narrow alleys with closely spaced buildings, no sidewalks, and limited access for larger motorized vehicles, such as garbage trucks. (E) shows the disaggregation of a section of the Caramuru Urban Integration Project (LHIS), promoted by the Associação Oeste de Diadema in 2008. The project includes plots ranging from 42 m

2 to 75 m

2. In this LHIS, houses were self-built based on a supported design with technical assistance. Unlike Vila Olinda Favela (D), the built density in Caramuru LHIS is lower, allowing open spaces within the plots. These spaces provide ventilation and natural lighting inside the buildings. A strategy was adopted to reserve the edges of the plots as open areas, creating a corridor-like space between buildings. The road system consists of wider streets than those found in most urbanized centers of Diadema, ensuring greater spacing between buildings, sidewalks on both sides, and access for larger road vehicles. Finally, (F) presents the disaggregation of a section of the Conceição neighborhood, part of the Vila Conceição housing complex implemented in the late 1950s. The analysis reveals land subdivision into 250 m

2 plots, some of which were further divided into 125 m

2 units—a common occurrence during the expansion and occupation of underprivileged peripheral areas in the RMSP.

While the buildings present in the section are outside the build parameters stipulated in city laws, the build density is lower than that of both the Vila Olinda Slum (D) and Caramuru LHIS (F). The build process is unclear because, at the time when the housing development was implemented, the buildings were typically self-built or constructed using unskilled labor.

The road system comprises broader streets than those in the other sections, allowing sufficiently wide public walkways for tree-planting and installation of electrical lines on both sides of the road, as well as parking spots and circulation of large vehicles.

Comparison of the sections shows that the laxer urban parameters in LHIS for formal housing developments adopted by Diadema city, coupled with the support of professionals from the fields of architecture and urbanism in 100% of the projects, contributed to an increase in density. As a result, a higher number of families were accommodated without an associated decrease in the quality of the built environment found in informal areas.

Favela urbanization projects faced numerous complexities, starting with the need to carry out urbanization within already occupied favelas and, in some cases, amid a process of ongoing expansion. In the case of the LHIS developed by associations, the design project preceded the occupation of the area, allowing the implementation process to abide by the parameters stipulated by law, resulting in a higher quality built environment relative to that of informal areas.

Scheme 2 below contrasts the difference between the built urban spaces in

Scheme 1. (G) shows an alleyway of the Vila Olinda slum; (H) a street in the Caramuru LHIS; and (I) a street in Vila Conceição.

4.3.2. Self-Built Housing in LHIS

With regard to the housing, self-construction was the solution adopted by the families in the LHIS. Self-building was, and continues to be, executed in stages according to the time and financial resources available to each family.

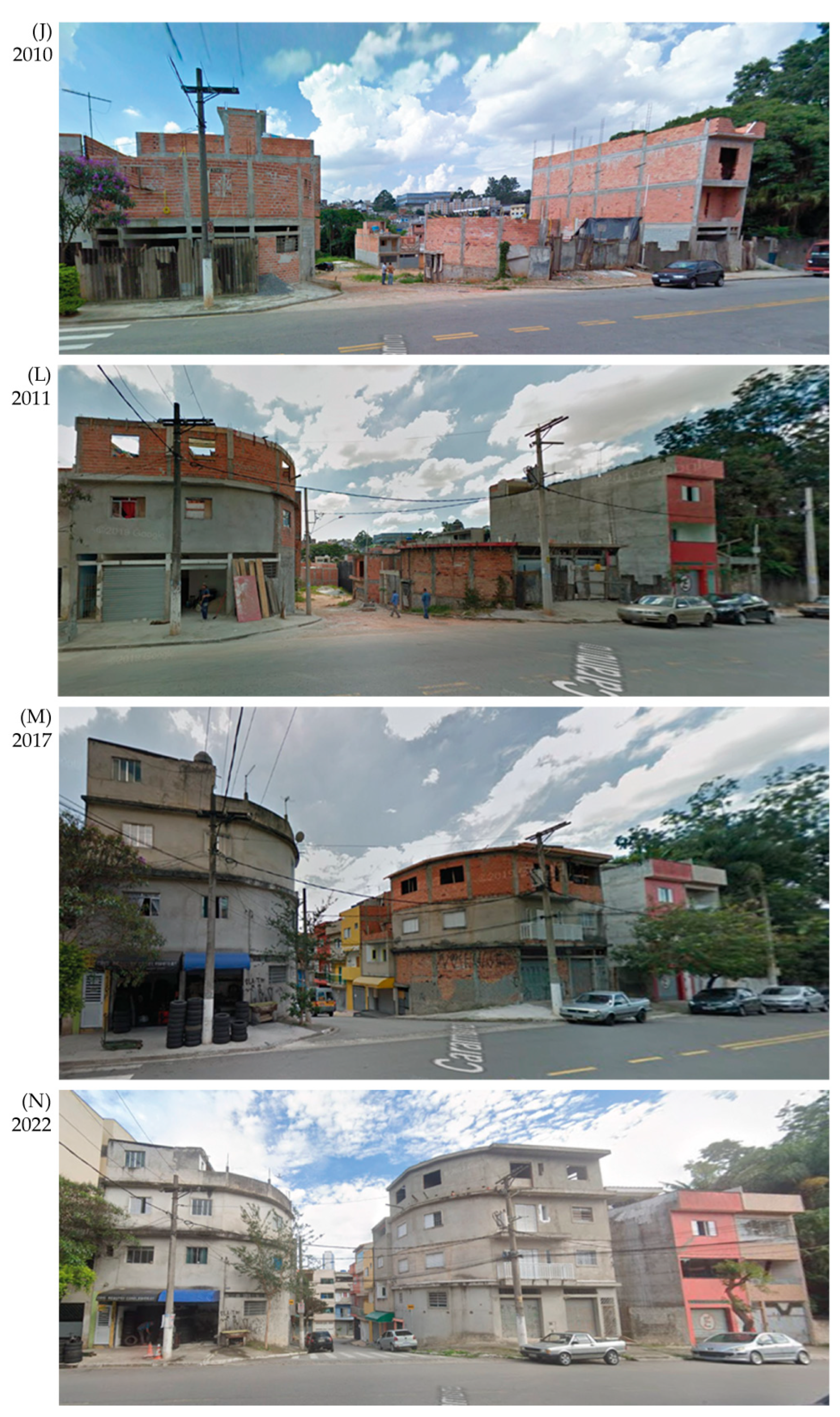

Scheme 3 shows the long self-build process and stages of construction between 2010 and 2022. Self-construction is a build modality found in most Brazilian cities. The images represent different years, namely: (J) 2010; (L) 2011; (M) 2017; and (N) 2022. It is noteworthy that, even after 12 years, parts of the buildings remain unfinished or in the process of expansion.

The protracted process of self-construction meant that many families continued building their homes without the aid of professionals who, for numerous reasons (including time) were unable to continue providing technical support and assistance.

Built by the residents or hired informal labor, the houses developed in the Diadema LHIS typically have 3 or 4 stories, with many remaining in an unfinished state, as shown in

Scheme 3.

Figure 6 shows sections of Vila Santa, produced by the Oeste Association in 1999, depicting the number of stories and the stage of completion of the houses.

5. Discussion: Social Production of Habitat and the Right to the City

The experience of Diadema illustrates how urban space can be co-produced through bottom-up processes, drawing on what Holston [

26] terms insurgent citizenship—the claim to urban rights through collective political action that challenges exclusionary state norms. The creation and implementation of AEIS-1 areas, and the housing projects developed through self-management, embody a form of social production of habitat [

27], in which residents themselves organize, plan, finance, and build their homes. These practices resonate with the “right to the city” framework proposed by Lefebvre [

1] and later expanded by Harvey [

2], affirming that access to urban resources must be collectively negotiated and not determined solely by market logics.

This theoretical lens helps us interpret Diadema not just as a case of alternative housing provision, but as an emblematic example of how grassroots movements—when equipped with institutional tools and political agency—can influence urban policy and spatial justice.

Following the implementation of the Special Areas of Social Interest (AEISs), social movements in Diadema reorganized into formalized associations, conferring them legal autonomy to deal with land, run projects, and oversee housing developments. This process gave rise to entities such as the Associação Oeste, AMAPRE, and Pró-Moradia e Liberdade, which played a central role in formulating the goals of the Master Plan.

The main activities undertaken by the associations include:

Identifying Land: Performing surveys to map areas fit for demarcation as AEIS-1.

Devising Projects: Engaging architects and engineers to plan land parceling and housing.

Community Organization: Mobilizing community aid efforts to implement basic infrastructure such as curbsides, storm drains, and green areas.

These associations were not only agents of housing delivery but also key political actors who reshaped the urban policy agenda of Diadema. By articulating technical knowledge and community practices, they managed to institutionalize alternative forms of access to land and housing, thereby redefining the role of the state and the meaning of urban citizenship.

The production model adopted by the associations was based on sharing costs among association members, who were actively involved in executing the building work through community collaborations. This strategy allowed a substantial cost saving on the implementation of infrastructure, such as paving, water and sewer systems, and planting of green areas. Collective aid also strengthened community ties and empowered residents.

While this model, underpinned by self-management and community organization, enabled the occupation of underutilized areas and expanded access to housing for vulnerable groups, it also revealed structural limitations. The reliance on self-financing and voluntary work often meant uneven outcomes, and in the absence of consistent public support, many developments faced challenges in completing infrastructure and ensuring the long-term quality of the built environment.

Figure 7 highlights Canhema I LHIS, illustrating the higher density and verticalization of the housing, made possible by the new urban parameters adopted by the Diadema associations. This housing development was implemented by the Oeste Association in the 2000s.

The present study extracted the maximum amount of information possible from the documents gathered in the documentary study in order to quantify and highlight the LHIS produced by the housing movement associations under the self-finance model in Diadema.

The case of Diadema shows that the democratization of urban policy can emerge from the bottom up, especially when anchored in strong social mobilization. However, it also demonstrates that community-based housing production cannot substitute the state’s role in guaranteeing the right to adequate housing. The sustainability of such models depends on robust public policies, technical support, and financial mechanisms that go beyond the logic of self-help.

Despite the advances made, limitations remain. The lack of financial and technical support from the authorities was a factor limiting the scope of the development initiatives promoted by the associations between 1996 and 2013, directly impacting the quality of the built environment.

6. Conclusions

The experiences reported in Diadema exemplify what Lefebvre [

1] called the “social production of space”—the collective shaping of urban territory through everyday practices, technical knowledge, and grassroots mobilization. These processes also embody what Holston and others have described as “urban insurgencies” [

26], in which localized citizenship practices challenge dominant institutional logics and exclusionary planning norms. As such, the Diadema case represents a concrete manifestation of spatial justice in action, reaffirming the critical theoretical contributions of Lefebvre, Soja, and Harvey.

Social movements played a pivotal role in the urban transformation of Diadema, strengthening a participatory model which positively impacted the construction of formal urban space in the city. The formalized associations led fundamental processes such as identifying lands, devising projects and executing housing developments, promoting both spatial justice and social inclusion, securing the Right to the City described in [

1,

2]. In addition, the efforts of housing movement associations in the acquisition of available land and in developing tools, such as self-financing and collective collaboration. These efforts represent tools of resilience countering the commodification of urban spaces and promoting practices placing collective interest over and above market-driven logic, as outlined Montaner [

11].

The creation of Special Areas of Social Interest (AEIS) in 1994 represented a turning point in urban planning for Diadema and in addressing the housing crisis. This innovative policy, the fruit of struggles to secure the Right to the City, increased the availability of affordable housing and significantly improved the quality of life of more vulnerable populations. Furthermore, the initiative affirmed the transformative role of grassroots organizations in driving public urban policymaking.

The housing movement associations were pivotal in this process. As legal entities, they were able to acquire land, incentivize self-management and self-build practices and building stronger community ties. These initiatives proved fundamental for developing housing projects and fostering more integrated and resilient communities.

Self-management and popular mobilization not only fill the vacuum left by the absence of the state, but also build alternative forms of urban regulation, based on more democratic social pacts rooted in the territories [

5,

6]. Such approaches reflect lessons specially from Latin American precedents, such as the FUCVAM cooperative housing model in Uruguay, which similarly combine community agency with institutional innovation to achieve inclusive urban development.

The study underscored the effectiveness of AEISs as an urban intervention tool which, together with efforts of housing movement associations and technical support, contributed to transforming the urban structure of Diadema.

There are lessons to be learned from the development of social interest housing development (LHIS) experience in Diadema, such as the organization of housing movement associations, which enabled the development of housing for more vulnerable populations through the creation of urban instruments by public authorities, serving as a model that can be replicated in other cities facing similar challenges. The central role of the associations and active participation of the community proved key to the success of these initiatives.

The results confirm the importance of social movement in securing the right to the city. Through local mobilization and inclusive planning tools, the case of Diadema exemplifies the transformative potential of participatory governance in producing more democratic and equitable cities.

However, despite the LHISs developed, which have undoubtedly helped reduce the housing shortage in Diadema, the initiative faced limitations. The historical background makes clear that the option of resorting to LHIS and self-build housing stemmed from a lack of resources and funding by the public authorities in supporting the associations. Greater technical and financial support from the authorities could allow associations to offer other solutions, such as the construction of high-rise blocks, improving the quality of urban spaces, and increasing the number of housing units available.

Although this study does not aim to evaluate financial feasibility models, it is important to acknowledge that questions regarding the long-term sustainability of self-financed housing deserve further research. Alternative financing mechanisms such as ethical public–private partnerships or social impact instruments could be explored in future studies, especially in cases where self-management faces financial or institutional constraints.

Another limitation in the Diadema case was the low stock of land plots demarcated as AEIS-1 for HIS. The larger land plots were all used within a 12-year period (1996–2008), forcing the associations to pursue alternative means of making more housing available.

The persistence of exclusionary sociospatial structures and the selective nature of public investment hinder the consolidation of emancipatory experiences. Without a structural redesign of housing policies and access to urban land, such initiatives risk remaining confined to exceptional enclaves within an urban fabric marked by inequality [

1,

3].

By the time public resources and financing became available via the “Minha Casa, Minha Vida” program, the stock of land earmarked for AEIS-1 was low, limiting the scale of the projects and reach of the associations.

Lastly, the case of Diadema demonstrates that, when well organized and technically supported, social movements can play a decisive role in shaping public policies and implementing long-term housing solutions. It underscores the value of integrated participatory policies as a foundation for constructing a more just, accessible, and humanized urban space—consolidating the right to the city as a central pillar of Brazilian urban development.

Beyond its immediate achievements, Diadema also raises broader questions about the scalability of community-driven housing initiatives. Although rooted in a unique socio-political context, the participatory instruments and institutional innovations analyzed here may serve as inspiration for other municipalities confronting similar challenges related to housing shortages and spatial exclusion.

A deeper understanding of this case demands attention to its specific political and institutional configurations. The strong alliance between grassroots housing movements and the municipal government, along with the strategic availability of land for social purposes, was instrumental in enabling the implementation of AEIS-1. However, such enabling conditions are not always present in other urban contexts, which may constrain the replicability of this model. Moreover, while self-managed housing promotes empowerment and social cohesion, it also encounters persistent structural barriers—such as limited access to financing, interruptions in technical assistance, and inconsistencies in construction quality. These challenges underscore the importance of hybrid approaches that combine grassroots participation with sustained public investment and support. In this sense, Diadema exemplifies both the potential and the limitations of collective urban production in the absence of a robust institutional framework.

Importantly, these findings extend beyond the Brazilian context. They offer valuable insights into inclusive housing governance in scenarios marked by limited state capacity and institutional fragmentation. The Diadema experience may inspire cities globally to explore alternatives to conventional top-down planning by harnessing the transformative potential of grassroots innovation and community engagement.

In this broader Latin American perspective, the lessons from Diadema resonate with a wider wave of urban experiments centered on participatory, community-led development. They highlight how, even under structural constraints, socially grounded urban planning can produce inclusive, resilient, and equitable outcomes.