1. Introduction

Architecture is uniquely positioned among the disciplines that shape human experience and transform our physical environment. Therefore, architectural education requires not only the transmission of technical skills and theoretical knowledge, but also the development of the students’ creative thinking, critical analysis, and visual communication skills [

1,

2]. While traditional educational methods significantly develop this multifaceted skill set, digital age innovations can create new learning paradigms in architectural education. In this context, integrating digital storytelling into the digital design studio can transform the ways in which students explore and express architectural concepts. Investigating innovative teaching methods in architectural education aims to provide students with a more interactive and participatory learning experience [

3]. Digital storytelling is an interdisciplinary approach that enhances the students’ abilities to convey and present information in a narrative format. Combining comics, which merge visual and textual elements to present complex ideas and stories in a simple and accessible format, with digital storytelling allows architecture students to express their design ideas and architectural concepts in innovative and impactful ways [

4].

Design education involves the steps of creating design knowledge, stimulating the imagination, and developing methods of seeing and thinking. The studio environment’s dialogue-based learning approach facilitates the reevaluation of preexisting knowledge in various situations through inquiry, hence stimulating cognitive processes and fostering the development of novel connections [

5]. Digital storytelling aims to reinvent items in accordance with their purpose. Retelling stories in the exact locations where they happened helps us remember them. Connecting a digital narrative to a physical location can elicit feelings and add new aspects that let people repeat their experiences [

6]. The purpose of this study was to investigate how undergraduate architecture students use digital narrative and comic creation processes within the context of a digital design studio to strengthen their design skills, creativity, and understanding and expression of architectural concepts. This process allows students to develop both their individual creativity and collaborative working skills while also allowing them to reassess the role of digital tools and visual storytelling in architectural education [

7].

It is essential for architecture students to consciously use digital storytelling technologies through educational and entertaining activities in studio education. The research question of this article is how the digital storytelling method contributes to motivation and lasting learning in studio courses. Additionally, it explores the discovery of the social constructivist learning approach in the concept development phase of students.

This study aimed to analyze the effect of digital storytelling on the design process of architecture students. In this context, the following hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Digital storytelling increases students’ creative thinking skills.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Digital storytelling improves architecture students’ conceptual thinking skills.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Digital storytelling increases students’ motivation toward the design process.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, digital storytelling has emerged as an effective pedagogical tool in education, fostering creativity, deepening conceptual thinking, and enhancing communication skills. Integrating visual, auditory, and textual components, this method facilitates the students’ ability to articulate complex ideas more clearly and meaningfully while also encouraging active participation in the learning process [

8,

9]. Particularly in architecture and design-based disciplines, digital narrative methods are notable for supporting creative thinking and unveiling multi-layered conceptual relationships.

Marín and Margallo (2016) reported that the use of digital storytelling enhances critical thinking and self-assessment skills among architecture students [

10], while Lyu (2019) emphasized its potential to stimulate creative idea generation and improve visual com munication competencies [

11]. The integration of digital technologies into architectural education has further rendered this narrative form more interactive and interdisciplinary. For instance, Song et al. (2022) highlighted that incorporating digital storytelling into design thinking processes enhanced the students’ conceptual clarity and communication abilities [

12]. Similarly, Sung et al. (2022) demonstrated that digital narratives serve as an effective medium for conveying architectural concepts [

13]. A qualitative study conducted by Ginting et al. (2024) revealed that the application of digital storytelling significantly improved the students’ conceptual thinking and creativity levels [

14]. These findings were corroborated by Tripon (2024), who further confirmed the positive impact of narrative practices on learning processes [

15]. Arefi (2024) drew attention to the supportive role of storytelling, particularly within urban design studios [

16], while Shafique (2024), in their research on architectural and engineering education, demonstrated how storytelling enhanced the students’ abilities to build conceptual integrity and solve problems [

17].

These narrative-based approaches function not only as pedagogical strategies, but also promote a holistic understanding of learning that incorporates social and environmental contexts. Sharma (2024) argued that digital storytelling fosters a socially engaging learning environment within the framework of sustainable design education [

18]. Ottaviani (2024) explored the role of storytelling as an effective learning tool in design education, and Rowe and Chung (2024) emphasized how narrative-centered learning promotes a user-oriented design perspective by foregrounding qualities such as empathy, contextual awareness, and cultural interpretation [

19,

20]. Within this framework, narrative is not merely a presentation technique, but a constitutive element that shapes the production, representation, and comprehension of design [

21].

In architecture, narrative goes beyond being a pedagogical tool; it is also a fundamental component of cultural production. Bourouiba and Iger (2024) examined how narrative structures used in architectural exhibitions contribute to the construction of disciplinary identity and the representation of cultural pluralism [

22]. In another study, Casillo (2024) demonstrated that the reconfiguration of local cultural heritage through virtual reality technologies into digital narratives enables visitors to experience spatial and cultural contexts simultaneously, thereby enhancing cultural engagement [

23].

Digital storytelling, in the context of architectural education, serves not only as a technical mode of communication, but also as a multidimensional learning environment for conceptual exploration, creative expression, and critical thinking. When combined with student-centered pedagogical approaches, narrative-based learning supports both individual and collective design processes, fostering an inclusive and transformative educational experience.

3. Digital Storytelling

The most significant development in spatial design has recently been the rapid transformation of design and design practice by computers and digital technologies, leading to new approaches, theories, and concepts. This rapid transformation has also impacted spatial design education, resulting in the continuous discussion and updating of educational programs to include digital-based methods in their curricula [

24].

The primary goal of digital storytelling, which is defined in various ways, is to empower students to take responsibility for their learning process. The components of digital storytelling include Perspective, Dramatic Question, Emotional Content, Voiceover Capability, Power of Music in the Story, Simple Content, and Progression Speed (Rhythm). The process of creating a digital story involves finding a topic, researching and studying, writing the story text, creating a storyboard, collecting or creating images, sounds, and video files, combining all files, sharing, receiving feedback, and editing [

24]. These components, identified by the Center for Digital Storytelling, aim to create compelling digital storytelling. Moreover, nearly all accepted definitions of digital storytelling describe this technology as a way to combine different multimedia types, including moving/still images, texts, video clips, voice narration, and music, to tell a short story, typically a few minutes long, about a specific topic or theme [

25].

Simultaneously, while there are ongoing explorations in the pedagogy of spatial design education, advancements accelerated by computer technologies have made accessing information more accessible. This situation, linked to our relationship with digital media, has affected the knowledge produced and used in design practices alongside the methods of making design. It has influenced the design process and the tools and environments for research and information acquisition, similar to its impact on design action and representational tools.

Initially emerging in the 1960s as a format for films and television programs, digital storytelling only reached a narrow audience. By the 1990s, however, a team that included artists began to merge traditional storytelling with digital technologies. As a result, digital storytelling, a new concept born from developments in the digital realm, gained a new dimension by incorporating technology into the traditional storytelling tradition [

25]. Digital storytelling is a narrative tool where text, images, animation, and music suitable for the story are combined and expressed using various software. According to Robin (2008) [

8], digital storytelling involves creating and presenting narratives using multimedia tools such as text, audio, images, and animation to inform about a specific topic, whether real or fictional.

The first principal component of digital storytelling is media, which indicates that this concept involves verbal as well as visual and auditory elements. Thanks to multimedia environments where graphics, text, animation, sound, and images are used together, stories are presented with richer content, making complex information more easily comprehensible through visualization [

26].

In this study, the advantages of digital storytelling were actively used to support the students’ conceptual development. In particular, it analyzed how students developed their individual creativity in the design process and how they enriched their narratives using digital tools. Digital storytelling is predicated on a story that combines text, multimedia, sound, and transient storytelling through the “creative process” of digital meaning-making [

8,

9,

24]. A short story, which can be a personal narrative, a classic fairy tale, or just a short story, is created or told using semiotic codes (e.g., visual, linguistic, graphical, aural) and logical tools (e.g., computer, video camera, audio recorder). It can take several forms, ranging from an oral history that has been recorded to intricate narrative pieces like live films or book trailers. Several components are mentioned in digital storytelling, according to Lambert (2002) [

24]:

Perspective of the author(s): The starting point of the story or the perspective of the author(s).

A dramatic issue: The issue ensures the story continues engagingly and is resolved.

Emotional content related to individually addressed topics: The issue that affects the observer or reader.

Personalization: Reviving and personalizing the story by incorporating personal interpretations.

The role of digital storytelling in education, the importance of graphical representations in visual communication, and the impact of digital technologies on the architectural design process are central to this discussion. Storytelling is a powerful tool that helps students understand and express complex ideas effectively. Through visual storytelling and textual content, comics enhance the students’ ability to communicate design ideas to various audiences. Integrating digital technologies makes design processes more flexible and offers students a broad range of tools and techniques [

10].

The conceptual foundations of digital storytelling begin with the dialogic story circle phase and conclude with another dialogic phase called the in-group performance. While dialogue plays a crucial role in executing other phases, there might be situations during the digital phases where participants need more communication. Naturally, digital storytelling can involve more discussion. Depending on the situation and theme, periods of intense shared time can occur throughout the process. After the story circle, the process involves creating the text or notes that form the basis for voice recordings, recording the voice, creating visuals, and assembling the digital story. Following the storyteller’s explanation of each digital story, participants observe during the in-group performance phase and exchange feedback regarding their final digital stories. The terms “digital phases” and “dialogue phases” refer to the stages of using computers, text/notes, voice recording, visuals, and the merging of voice and visuals [

26]. Digital storytelling transforms voice and speech into a visual narrative.

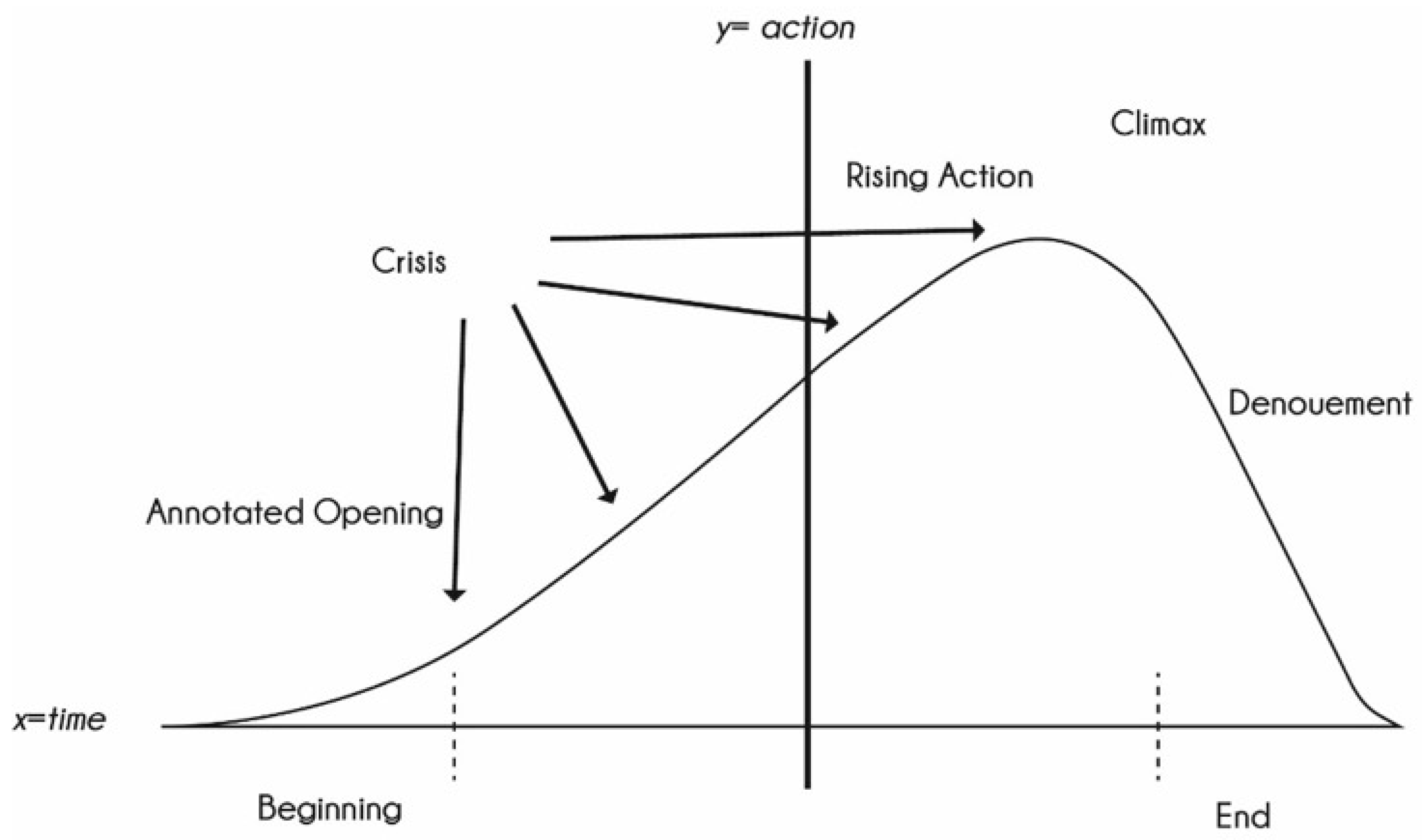

The studio instructor assists in achieving the course objectives by following the digital storytelling preparation procedures with basic computer skills. Through their creation of course materials, students have their interest piqued and enthusiasm for the subject matter. The digital story design stages presented in

Figure 1 were modeled in line with the data obtained from the digital design studio cases examined. In this process, the methods followed by the students while structuring their architectural narratives were evaluated.

Components of Digital Storytelling

Events: A story’s events ought to be structural in nature. For example, tragedies brought on by building demolition or morally dubious incidents coming from disregarding architectural design standards might both be taken into consideration.

Subject: Throughout the story, the subject should raise various questions in the minds of the students, ensuring that they follow the narrative and apply architectural solutions.

Perspective: A story should be told from the viewpoints of different actors in the architectural environment including an architect, a user, a designer, and an implementer. At various points in the narrative, these different perspectives should be incorporated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Hero: The author should make sure that the hero is dedicated to upholding professional and ethical standards including environmental consciousness, ongoing improvement, architectural distinctiveness, and all other requirements for utilizing constructed structures to save lives.

Core: The story’s central theme is the interaction between cause and consequence. An architectural narrative should include both architectural causes and their human and architectural consequences as events.

Atmosphere: Compared with other tale genres, the architecture of a space and its atmosphere are more crucial.

All of the advantages of the storytelling method can be utilized in the studio [

27].

4. Digital Storytelling in Design Studio Education

The current educational reforms, which seek to replace knowledge-based pedagogy with student-centered pedagogy, are guided by constructivist teaching/learning, which is in line with the integration of digital storytelling into the classroom [

28]. Pupils develop into subjects that reconstruct information critically [

29]. Digital storytelling thus advances in tandem with some concepts formulated within this lineage including Vygotsky’s notion of learning as a cultural process, Piaget’s perspective on the learner as a producer of meaning, and Ausubel’s insistence on meaningful learning. It is also connected to particular forms of constructivist teaching and learning, such the project-based approach that resulted from Freinet’s research, which organizes learning to provide students with the tools and agency they need to solve an issue or produce an output [

30]. Furthermore, because digital storytelling engages several talents including reading, writing, speaking, and listening, it is consistent with a competency-based approach. Pitler (2006) posited that the effectiveness of incorporating technology into education is enhanced when paired with pre-, during, and post-project scenarios that the students discuss such as collaborative and cooperative learning [

31].

Digital storytelling has been defined as a pedagogical application of the social constructivist approach, serving as a tool for acquiring and sharing knowledge [

9,

24]. It is an effective teaching strategy for motivating students and making abstract content more understandable [

9,

24,

28]. Learning is enhanced through the reflection of identity [

32] and “personal creativity” [

33]. Digital storytelling uses the discursive codes that recipients develop in everyday life (e.g., cinema, television) to tell their stories. In today’s architectural education, students use not only traditional software such as Photoshop 2023 and Illustrator 2023, but also Unity, Unreal Engine, and AI-based visualization tools [

34]. Therefore, a wider range of software should be taken into consideration when integrating digital storytelling into today’s education system.

Technological advancements and widespread use significantly impact younger generations, primarily through digital tools [

35]. Current methods of teaching digital design reveal that students drawn to this area by their fascination with virtual environments and interaction design are frequently prepared to handle challenges pertaining to made-up and virtual scenarios that have little bearing on reality. Put differently, students working on hypothetical scenarios based on digital interaction and coding might be seen as part of the teaching environment. It has been noted that student design efforts influenced by these and related methods frequently have poor structural efficiency and produce physically and perceptually unusable products. It is thought that promoting a human interaction with time and space in schooling will help lessen the negative effects of digital media. In order to comprehend how we might integrate design education with cognitive sciences in the framework of time and space, the following domains were investigated [

36].

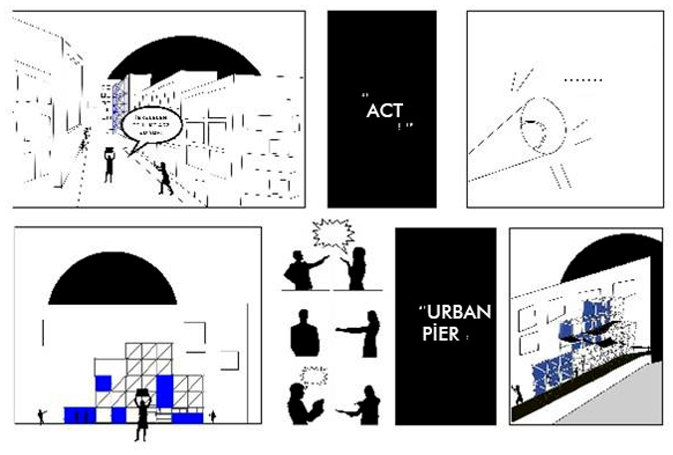

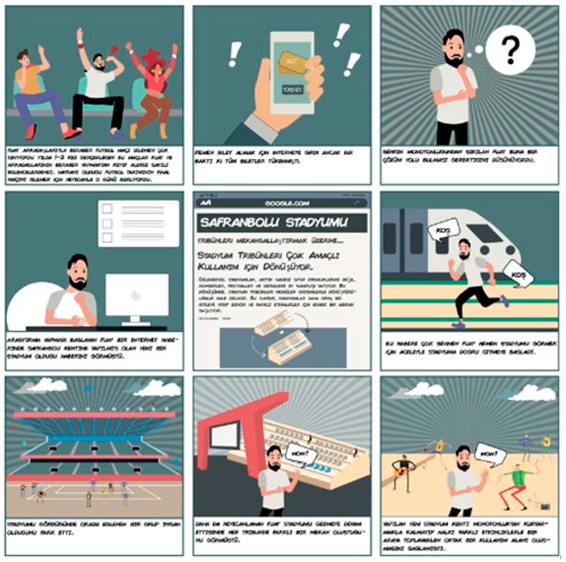

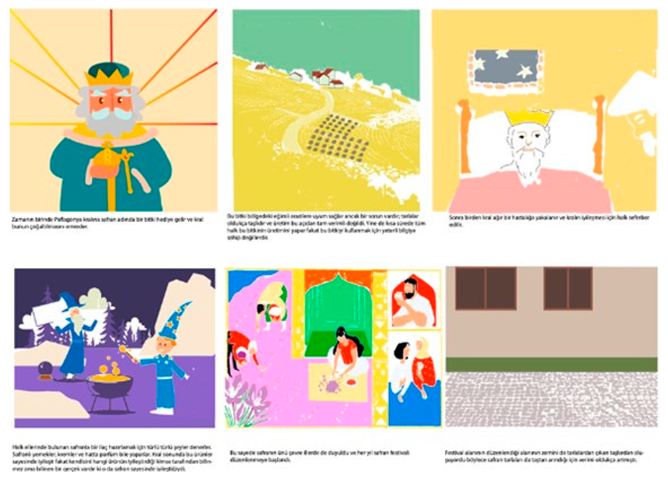

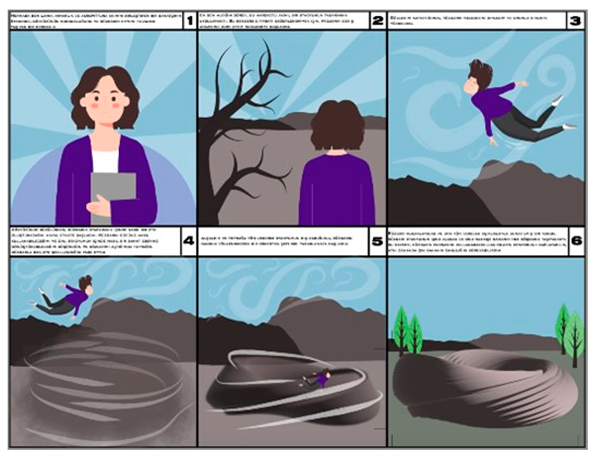

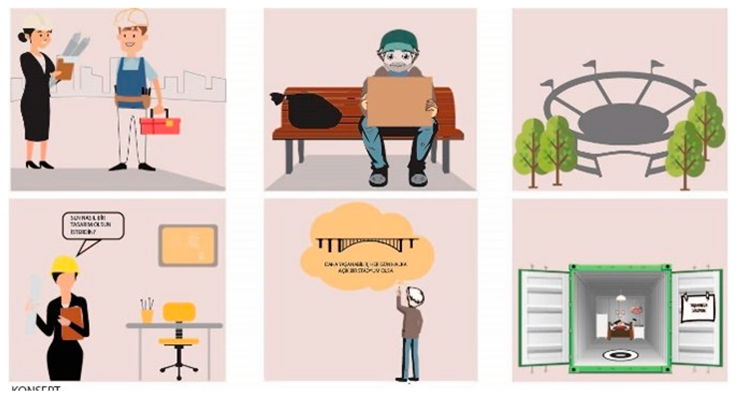

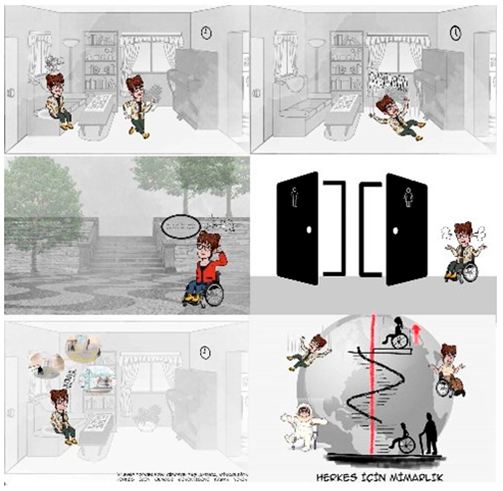

The scope of the research was limited to third-year undergraduate architecture students enrolled in a digital design studio. These students used digital tools to create original comic strips that revolved around specific students, improving their ability to convey their ideas and highlighting the potential effects of digital storytelling creation processes in architectural education. They also revealed the potential effects of these methods on the students’ creativity, design skills, comprehension, and expression of architectural concepts. Prior to engaging in the digital storytelling assignment, the third-year undergraduate architecture students had been introduced to the fundamental concepts of Visual Literacy, a conceptual approach to graphic problem-solving, during their first-semester ‘Principal Design’ course. This foundational knowledge, potentially supplemented by resources such as the work of Judith and Richard Wilde, provided a basis for their understanding of visual communication strategies and the effective use of graphic elements in conveying meaning. While students possessed this initial grounding, future iterations of the course could benefit from a more explicit review or integration of Visual Literacy principles directly preceding the digital storytelling assignment to reinforce these crucial skills.

5. Methodology

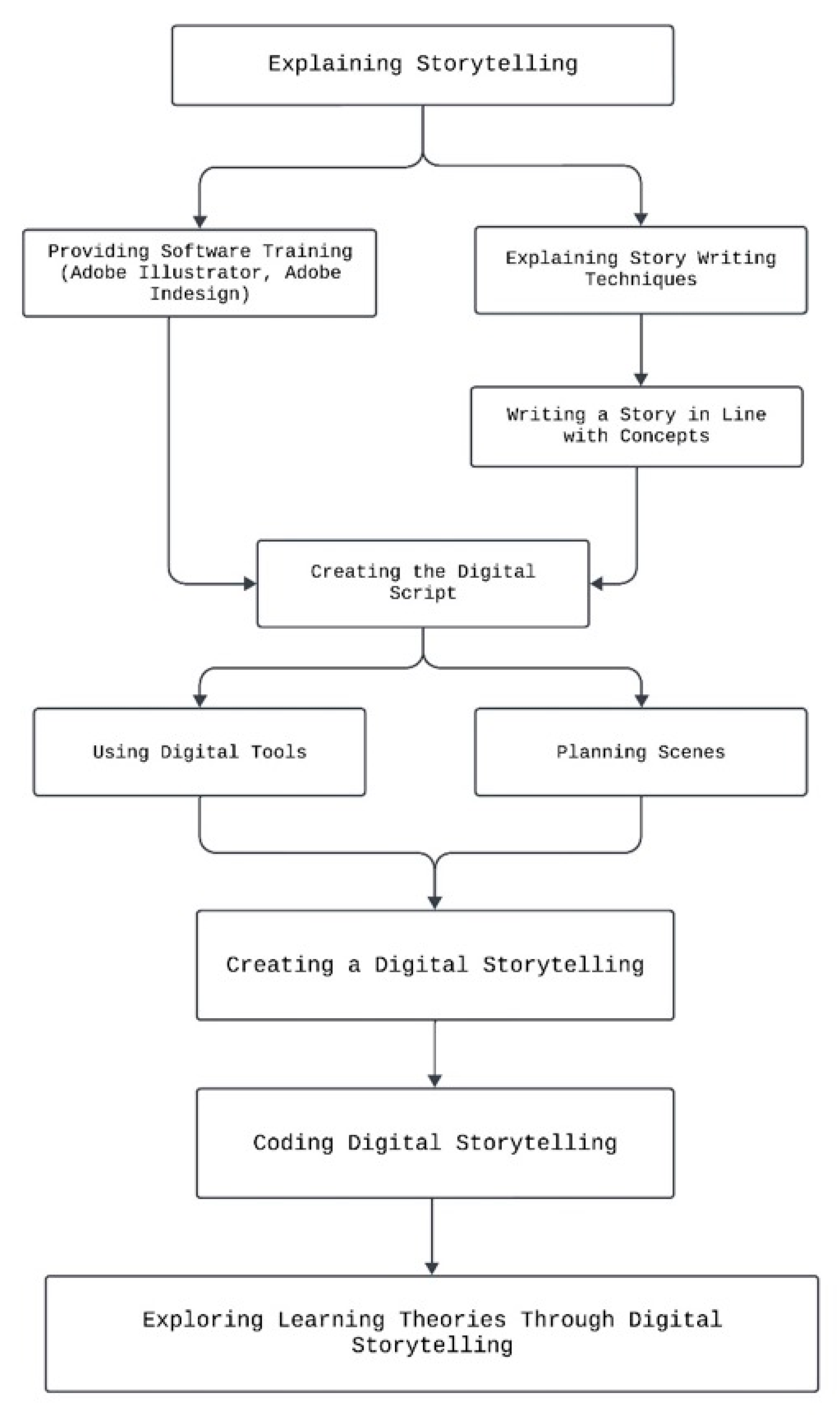

In this study, we implemented digital storytelling as a pedagogical tool within a third-year undergraduate digital design studio course. The students, organized into ten distinct teams, were tasked with creating digital storytelling projects (digital comics) to express their architectural concepts. The data for this research comprise the complete set of these ten digital storytelling projects, representing the entire output of the assignment for the academic term. It is important to note that these ten projects were produced by a total of twenty-six students participating in the course across the ten teams. While this comprehensive inclusion of all student work provided a rich dataset for our initial qualitative exploration, it is acknowledged that the sample size of ten teams (comprising twenty-six students) had limitations regarding statistical generalizability. This limitation is further discussed in the subsequent sections, and it is emphasized that this study serves as a foundational investigation into the potential of digital storytelling within this specific educational context. Future research involving larger and more diverse student populations will be necessary to further validate these initial findings. The flowchart illustrating the study’s methodology can be found in

Figure 2.

To create instructional strategies and comprehend the learning process within this framework, our method was also informed by participant feedback and real-time observations [

37]. The research process encompassed planning, creating, and presenting stories in an area where students had autonomy regarding their chosen architectural subject, alongside the acquisition of graphic design tools and storytelling techniques.

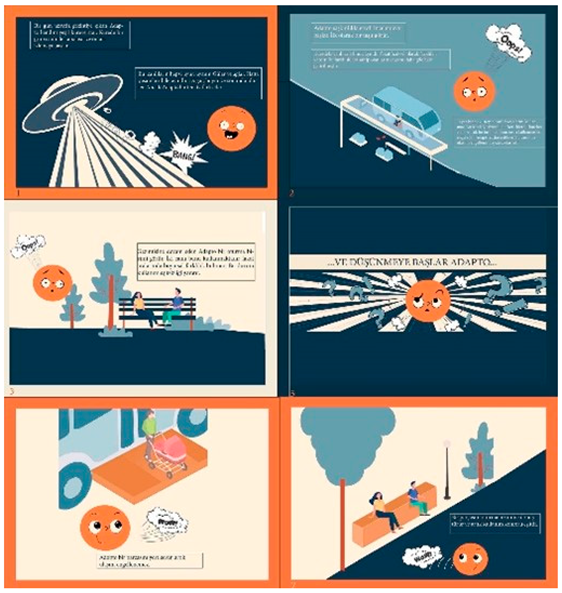

The evaluation of student work was based on specific criteria such as creativity, narrative skills, competence in expressing architectural concepts, and visual narrative quality. Both qualitative and quantitative analysis were used in the evaluation process. Students chose an architecture-related theme and created a story idea around it after completing the required instruction. Ideas for stories might focus on a variety of subjects such as sustainability, historical structures, futuristic cities, or design concepts. At this point, students bring their ideas to life through scriptwriting approaches. Visual Design: Students choose the comic style and visual language to be used to communicate their narrative. Character design, panel layout, color palette selection, and spatial drawings are all part of this process. Instructors in the course teach students how to use digital drawing tools like Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, and others to create their images. Digital Production: A digital comic format is developed from the drawings made during the visual design process. Pupils incorporate comedic features including sound effects, story boxes, speech balloons, and page layout. In this process, the students’ proficiency with digital technologies becomes crucial. Presentation and Evaluation: Completing the comics enables both instructor and peer evaluation. Creativity, narrative prowess, architectural concept expression, and visual narrative excellence are all included in the evaluation process. Pupils receives criticism on their work and can use that criticism for subsequent assignments.

The following research questions were sought within the scope of this study:

How does digital storytelling affect the students’ architectural thinking processes?

What kind of change is observed in the students’ perceptions of design processes with digital storytelling?

How are the students’ creative thinking skills developed with digital storytelling?

Table 1 represents the student work evaluation criteria where

Table 2 shows the evaluation by categories.

Despite its limitations and small sample size, this study provides a foundational basis for the development of a methodology, highlighting the need for future research with larger and more diverse samples to further refine the approach and validate the findings.

Parameters for Using Storytelling Methods in Architectural Design Studio Education

Personalizing

Design Ideas: To make their stories more interesting and relatable, students should be encouraged to personalize their design suggestions.

Creating an Architectural Storyline In Line with Studio Education Goals: Creating a narrative that supports the studio course’s learning objectives.

Producing Concept Sketches Using Digital Technologies: To make preliminary sketches that graphically convey conceptual ideas using digital technologies.

Ensuring Consistency between Feedback and Graphics: Maintaining coherence between the feedback received and the graphical representations of the design ideas.

Clarifying the Objective: Clearly define the purpose of the project and the intended outcomes.

Completing the Digital Story: Finalizing the digital story by integrating all elements into a cohesive narrative.

5.1. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the content analysis method. In this method, categories were created according to social constructivist learning principles. During the analysis process, the main themes focused on creativity in student work, the quality of visual narration, the processing of architectural concepts, and storytelling skills.

5.2. Categorization

Projects were tagged with specific codes that represented their pedagogical objectives. The students’ work was categorized to reveal the thought processes underlying the stages of architectural concept development:

Informative: (Educational-Informative)

Inspirational: (Imagination-Personal Development)

Problem-Solving: (Critical Solution)

Empathy and Understanding: (Social Sustainability)

Imitation: (Exemplification)

6. Results

The research delved deeply into how architecture students responded to digital storytelling and comic book creation and the impact of this process on their design skills, creativity, and understanding of architectural concepts. It was based on social constructivist learning methods such as the ability to use digital storytelling tools, the consistency of digital products with conceptual ideas, imagination, and the concretization of abstract ideas.

Table 3 provides an overview of the student digital stories created as part of this study.

In terms of character design, environment drawing, and color utilization, the pupils showed a great deal of inventiveness. They were able to freely explore and convey their creative ideas thanks to the storytelling format. Visual storytelling has become a valuable resource for comprehending architectural ideas and design procedures.

The students’ comprehension and application of architectural ideas and concepts have significantly increased thanks to digital tales. Students gained the capacity to explain complicated architectural ideas to a wider audience by simplifying and making these ideas accessible through comics. Students were able to strengthen their theoretical understanding and hone their practical application skills through this procedure. Notably, a student who completed the course and their team used this technique to present their ideas and win first prize in an architectural project competition.

The results of the research showed that the production of digital stories had a good effect on the students’ overall architecture education learning experience. Students were able to freely express their creativity, delve deeper into architectural topics, and hone their design talents thanks to this method. It also improved the students’ capacity to communicate architectural ideas to a wider audience in an understandable and clear manner.

Within the scope of the study, it was observed that there was a 25% increase in the students’ creative thinking skills and the students’ motivation toward the design process increased by an average of 30%.

Table 4 shows the conceptual categorization of student works.

A socially rich environment is necessary, and interacting with adults and peers who have more life experience can assist people to further improve their cognitive abilities, according to Vygotsky’s social constructivist learning theory [

38]. This theory is well-known for emphasizing the importance of social context, cultural background, and collaborative learning. An additional essential element of social constructivist learning theory in relation to digital storytelling is collaborative effort which is impacted by external circumstances. This assertion was supported by Student 1, Student 4, and Student 7. The students’ stories reflected the impact of the physical environment as a social component. Social constructivist learning continued throughout the entire process. It was also strongly associated with communication skills and decision-making. Social constructivist learning helped students develop problem-solving techniques, enhancing their creative thinking. This was strongly connected to their decision-making and problem-solving abilities, enabling students to analyze issues, perceive problems, and independently decide on the direction of their designs. The students’ critical thinking, which facilitated the progression of their design projects, also improved. The use of information and digital communication technologies in a social constructivist learning environment was beneficial in developing the students’ attitudes toward digital storytelling. Information and communication technologies also helped the students interpret, visualize, and present what they had learned, capturing their attention in a social constructivist learning environment.

For the Informative (Educational-Informative) category, Student 4 focused on the processing and storing of information. Informative content helps students interpret information accurately and effectively by presenting it. For Inspirational (Dream-Personal Development), Student 5 emphasized the importance of individuals realizing their potential and self-improvement. Inspirational content motivates students to achieve their goals and improve themselves. For Problem Solving (Critical Solution), Students 2, 9, and 10 were expected to analyze and critique the problems they encountered to solve them. Problem-solving content aims to develop critical thinking skills. For Empathy and Understanding (Social Sustainability), Students 1, 3, and 7 emphasized learning through observation and modeling. Empathy and understanding content helps individuals develop their social skills and emotional intelligence. For Imitation (Modeling), Students 6 and 8 advocated learning by observing others. Imitation content encourages adopting positive behaviors and models. Students used the social constructivist learning theory for their digital stories to research and concretize the abstract concepts they had learned. Therefore, using information and digital communication technologies in the design studio to capture the students’ attention and pique their curiosity will increase their interest in digital storytelling and help them develop a positive attitude toward the subject.

Team 2 won first place in a national competition with their design project using digital storytelling. This proves the contribution of the method to the students’ design processes.

7. Discussion

This study explored the integration of digital storytelling, specifically through the creation of digital comics, within a third-year undergraduate digital design studio to enhance the students’ visual communication skills, design thinking, engagement, creativity, and conceptual understanding. Our findings, derived from the qualitative content analysis of ten team-based digital storytelling projects (involving a total of twenty-six students) and informed by instructor observations, suggest that digital storytelling holds significant potential as a pedagogical tool in architectural education.

The emergent categories of student digital stories—informative, inspiring, problem-solving, and empathy and understanding—illustrate the diverse ways in which students engaged with architectural concepts through narrative. This aligns with the principles of social constructivist learning, where students actively construct knowledge by framing information within personally meaningful contexts [

39]. The act of developing a narrative, incorporating visual elements, and articulating architectural ideas through this medium encouraged students to critically reconstruct information and make novel connections, fostering deeper understanding [

40,

41].

Furthermore, the collaborative nature of the team-based projects likely fostered a cultural learning process [

42], where the students learned from each other through shared planning, creation, and presentation. The integration of digital tools, ranging from traditional software like Photoshop and Illustrator to potentially more advanced visualization tools mentioned by Hu and Li (2025) [

43], provided students with the agency to express their concepts in innovative ways, consistent with a project-based approach [

30]. The engagement of multiple skills—reading, writing, speaking (during presentations), and listening (during feedback)—also suggests a compatibility with a competency-based approach [

31].

The positive attitudes observed toward digital storytelling within the social constructivist learning environment underscore its potential to motivate students and make abstract architectural content more accessible [

9]. The ability to personalize their design suggestions and create compelling architectural storylines likely contributed to this enhanced engagement [

32].

However, this study also acknowledges certain limitations. The sample size of ten teams (twenty-six students) from a single institution limits the statistical generalizability of the findings to broader student populations. The primary reliance on qualitative content analysis and instructor evaluations, while providing rich insights into the nature of student engagement and conceptual articulation, could be complemented by more rigorous quantitative measures in future research. The rapidly evolving landscape of digital tools necessitates an ongoing consideration of a wider range of software and digital media that students are increasingly familiar with [

44,

45]. Addressing the potential disconnect between virtual design skills and the understanding of physical and perceptual realities in architectural design is also crucial in future applications of digital storytelling [

46,

47].

Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable initial exploration into the integration of digital storytelling in architectural education. The findings suggest that this method can indeed enhance students’ creative thinking and contribute to the development of vital conceptual design skills by providing a platform for active learning, narrative construction, and visual communication.

This study was guided by three primary hypotheses concerning the impact of digital storytelling on architectural design education. Based on the qualitative analysis of student work and observations during the course, the following conclusions were drawn in response to each hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Digital storytelling increases students’ creative thinking skills.

The results support this hypothesis. Students demonstrated enhanced creativity in developing and communicating design ideas through digital storytelling. The process of translating architectural concepts into narrative comic formats encouraged originality and imaginative thinking. By engaging with a visual storytelling medium, students explored alternative approaches and produced more inventive solutions throughout the design process. This aligns with the findings of Lyu (2019), who emphasized digital storytelling’s potential to stimulate creativity and visual expression in design students [

11]. Likewise, Robin (2008) [

8] highlighted that multimedia storytelling supports the integration of cognitive and affective domains, thereby fostering innovation and originality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Digital storytelling improves architecture students’ conceptual thinking skills.

Throughout the design process, students developed clearer and more structured conceptual frameworks. Constructing narratives encouraged them to critically reflect on the underlying ideas and values of their projects. This observation is consistent with Song et al. (2022), who found that digital storytelling promoted conceptual clarity and expressive competence in design education [

12]. Furthermore, Brophy (1998) [

48] and Cross (2023) [

49] stressed the importance of externalizing conceptual reasoning in design thinking—a function that storytelling supports by prompting students to narrate, justify, and structure their design decisions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Digital storytelling increases students’ motivation toward the design process.

The study provides compelling evidence that digital storytelling positively influences student motivation. The creative and collaborative nature of storytelling, combined with the integration of digital tools, made the learning experience more interactive and personally meaningful. These findings are in line with Sharma (2024) [

18] and Ottaviani (2024) [

19], who suggest that narrative-based pedagogies enhance student participation and foster deeper connections with both the subject matter and the learning community. Additionally, Ohler (2008) noted that the multimodal aspects of digital storytelling allowed students to draw on diverse strengths and interests, promoting a more inclusive and motivating studio environment [

9].

8. Conclusions

This research revealed that integrating digital storytelling processes in architectural education significantly impacts the crews’ design skills, creativity, and ability to understand and express architectural concepts. The results showed that by using these techniques, crews are better able to comprehend and communicate difficult architectural concepts. These techniques also helped the crews showcase their architectural designs to a larger audience and improve their visual communication abilities.

According to the study, digital storytelling fosters the creativity and design abilities of pupils. Crews were able to convey and visualize ideas or architectural concepts using comic books, which helped them come up with more original and creative solutions during the design process. Additionally, this technique helped the students improve their critical thinking abilities.

Taking into account the individual differences of the students, the effects of digital storytelling on each individual should be analyzed in detail. In particular, significant differences were observed between students with previous digital experiences and those without.

According to the study, all pupils comprehended the architectural ideas and concepts more fully when they were presented in the form of digital stories. This approach has been shown to be especially useful for comprehending and communicating abstract and complicated architectural concepts in a clear and understandable way.

The study revealed that the students utilized a variety of sources during the concept generation process, which were categorized as follows: Informative (Educational-Informative), Inspirational (Imaginative-Personal Development), Problem-Solving (Critical Solution), Empathy and Understanding (Social Sustainability), and Imitation (Example-Based). These categories reflect the diverse modes of creative thinking and problem-solving strategies employed during the design process.

This multidimensional approach to idea development aligns with established frameworks in design thinking and creativity research. As Cross (2023) and Lawson (2006) outlined, designers frequently integrate analytical reasoning, experiential learning [

49,

50], and imaginative exploration to produce innovative design outcomes. These findings are further supported by Brophy (1998), who emphasized the importance of drawing from varied cognitive sources to enhance individual creative problem-solving efforts [

48]. The emergence of categories such as empathy and social sustainability also resonates with contemporary perspectives on design thinking, particularly those that foreground user-centered and socially responsible approaches [

51,

52]. Such approaches emphasize not only the functional and aesthetic aspects of design, but also its ethical and social dimensions. Moreover, the medium of digital storytelling appears to have facilitated the students’ ability to access and synthesize these diverse conceptual sources. As Robin (2008) notes, digital storytelling serves as a powerful pedagogical tool that supports critical thinking and conceptual development through narrative construction [

8,

53]. Similarly, Ohler (2008) highlighted how digital media allows students to personalize and visualize abstract concepts, making them more accessible and meaningful within the learning process [

9]. These results suggest that educators can use digital storytelling not only as a method of communication, but also as a catalyst for conceptual thinking, enabling students to articulate architectural ideas through multiple lenses and develop more nuanced design narratives.

Effect of Social Constructivist Learning: The social environment and physical surroundings positively affected the crews’ cognitive development. These elements aided the crews in producing their digital stories and enhancing their problem-solving techniques.

Integration of Digital Technologies: As the crews continued to develop digital stories parallel to the design process, they utilized digital technologies and tools at every stage including analysis, synthesis, research, and information gathering.

We may now reevaluate the use of digital technologies in architecture education thanks to this research. The students’ enthusiasm and engagement increased as a result of the more flexible and dynamic learning environment that digital narrative creation processes have brought to the classroom. Digital tools have improved the efficiency of design processes and provided students with a vast array of tools and approaches, enabling them to freely express their creativity.

This study investigated the impact of digital storytelling on architectural design education and demonstrated that this approach contributes to both the cognitive and affective development of students. Data obtained through student projects, in-course observations, and qualitative analyses indicate that this pedagogical method plays a creative, conceptual, and motivating role within educational environments.

The findings support the validity of all three initial hypotheses. Digital storytelling encouraged the students’ originality and imaginative exploration, thereby enhancing their creative thinking skills. It also supported the structuring and expression of complex ideas, strengthening their conceptual thinking abilities. Furthermore, it significantly increased student motivation through interactive and collaborative learning experiences. These results suggest that digital storytelling can serve as a multifaceted and effective educational tool in architectural design studios.

In summary, research has shown that the use of storytelling as a teaching method improves student performance in a variety of domains including communication, creativity, problem-solving, decision-making, cognitive perception, and visualization. Digital design studios and other elective courses are important components of architectural education that supplement the primary studio courses that form the foundation of architectural education. It is recommended that educators include digital technologies and visual storytelling techniques into their architectural education to offer students a more engaged, imaginative, and collaborative learning environment.

Although the study demonstrated the potential of digital storytelling techniques in architecture education, more investigation is required in this field. Subsequent research endeavors may investigate the suitability of these techniques across diverse academic domains and interdisciplinary settings. Assessing the long-term impacts of digital storytelling techniques and looking into how these approaches might be incorporated into the students’ professional activities are also crucial.

In the future, larger scale studies should be conducted with the participation of students from different universities. In addition, the effects of new methods such as artificial intelligence-supported digital storytelling in education should be examined.