Abstract

This study delves into an investigation of urban public outdoor spaces (POSs) from a health-oriented perspective, recognizing varied health needs encompassing physical, psychological, social, and environmental aspects. In this study, POSs of two typical government service centers (GSCs) were analyzed based on their structure, user demographics, and user satisfaction, revealing several problems with the current GSC POS designs. To address these problems, principles for GSC POS design were proposed for natural, playing, and social spaces and applied to redesign the Wuchang GSC. Firstly, through on-site surveys, questionnaire surveys, and data analysis, the existing problems in promoting residents’ health in the GSC POSs were revealed, such as the insufficient greening of natural spaces, lack of interest in playing spaces, and unreasonable design of the scale of social spaces. Based on the above analysis, a health design optimization principle based on Maslow’s theory is proposed. Firstly, improvement solutions were proposed and implemented for green spaces, such as using more diversified natural elements, zone differentiation, and landscape improvements to promote the health of users. Secondly, the leisure and sports needs of different age groups can be met simultaneously by diversifying the layout and functional settings of playing spaces. Finally, public spaces suitable for social interaction were redesigned to promote the psychological health of citizens in social activities by optimizing the scale of communication spaces. The proposed design optimization strategies for GSCs not only provide theoretical support for the healthy design of POSs but also provide useful references for the healthy development of urban public spaces.

1. Introduction

The concept of public open spaces (POSs), introduced in the sociological and philosophical literature in the 1950s and subsequently integrated into urban planning and design in the 1960s, has evolved to contain a variety of social attributes and has become increasingly focused on social function and improving the quality of life of its users [1].

Residential buildings stand at the core of contemporary urban advancements according to increasing standards and requirements for healthy cities [2,3,4]. The publication of the Athens Charter in 1939 sparked extensive global deliberations on housing and health, culminating in the formulation of a 15-point guideline for a healthy housing concept by the World Health Organization in the 1990s. The health-centric urban concept revolves around the implementation of healthy structures, embodies a people-centric philosophy, and strives to meet the health requirements (encompassing physiological, psychological, social, and environmental aspects) of inhabitants [5,6]. Following the declaration of the Healthy China Initiative in the report to the Nineteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2017, the health-oriented design of POSs has received increased attention.

In the current process of urbanization, the design quality of POSs, as important places for citizens to live, directly affects the physical and mental health of citizens. However, the current design of POSs gives little consideration to health factors, neglecting the potential use of public spaces as a major tool for promoting and improving the population's health [7].

In order to make up for these shortcomings, in recent years, numerous studies have been conducted on this subject, concentrating on the functional diversity and spatial planning that caters to the needs of individuals across different age groups, genders, and abilities [8,9,10]. These studies and practices aim to create a healthier and more humane spatial environment through specific design techniques.

Previous research has advocated for urban POS design to emphasize the creation of varied spaces for local residents, introducing the concept of urban POS resilience design to adapt to evolving social norms, psychological requirements, and travel patterns [11,12,13,14]. Before proposing an optimization design, determining the factors that affect the health status of residents through data analysis is necessary. Hu et al. [15] and Li et al. [16] collected data on the built environment and epidemic trends through a generalized linear regression analysis, aiming to understand the key built environment factors that affect user health. Specifically, conducting sufficient and specific questionnaire surveys can provide effective and authentic data. For example, in the past few years, many studies have analyzed the impact of buildings and outdoor environments on COVID-19 through questionnaires to residents [17,18,19].

After identifying the factors that need to be optimized, there have been some widely adopted design methods in urban public spaces: some studies [20,21] have shown that increasing the green vegetation, water features, etc. in public spaces can provide opportunities to interact with nature, promoting user physical and mental health. Public spaces should meet the needs of different groups of people and set up diverse functional areas [22,23]. Building upon the aforementioned design principles and methodologies, Tao et al. [24] proposed a wellbeing-centric life cycle assessment framework to support decision-making and improve energy efficiency in relation to human well-being and socioeconomic considerations. Additionally, Yan et al. [25] and Reinhart et al. [26] also presented models for evaluating the health metrics of public spaces.

While the current urban spatial design underscores the functionality and aesthetics of public spaces and combines strategies to optimize the fulfillment of the daily needs of local residents, the planners paid scant attention to health considerations, thereby overlooking the potential of public spaces as a key instrument for promoting and enhancing public health. In contemporary urban developments, the POSs of government service centers (GSCs) play a crucial role as hubs for interactions between local residents and the government, serving as “city saloons” that offer city dwellers venues for social gatherings, physical activities, and relaxation.

In this paper, based on a case study of two established GSCs, the problems of GSC POS design are analyzed from a health perspective, and health perspective-based strategies and principles for the design optimization of POSs are proposed. Finally, these strategies are applied to the redesign of the Wuchang GSC, aiming to introduce a novel health-centered framework to enhance the well-being of urban POS users.

2. Methodology

The POSs of two typical GSCs, the Wuhan Citizens Home (Wuhan GSC) and the Chengdu High-Technology District GSC (Chengdu GSC), were systematically investigated to understand the design problems of existing GSCs, determine user satisfaction, and provide benchmark data for the subsequent POS design optimization of the Wuchang GSC. The investigation was conducted by combining an internet search, a site survey, and mapping. The demographic structure and user satisfaction level were investigated using a questionnaire survey, with 100 questionnaires distributed for each GSC. The users were divided into three age groups according to the latest age grade system of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022): children (0–17), the young and middle-aged (18–65), and the elderly (above 65). The same method was used to evaluate the optimization effect of the Wuchang GSC.

In 1943, the American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed the well-known behavioral science theory of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which classifies human needs into five levels, namely from most to least required, physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization [27]. POS design is generally affected by multiple factors, such as their required functions, land use planning, financial budget, climate environment, social environment, and urban development planning [28]. In this paper, a POS design approach inspired by Maslow’s hierarchy is proposed, emphasizing the health perspective and guided by the principles of promoting well-being, ecological sustainability, and long-term viability. The subsequent analysis focuses on the design principles for natural, recreational, and social spaces within POSs.

3. Investigation of Existing GSC POSs

3.1. User Demographics

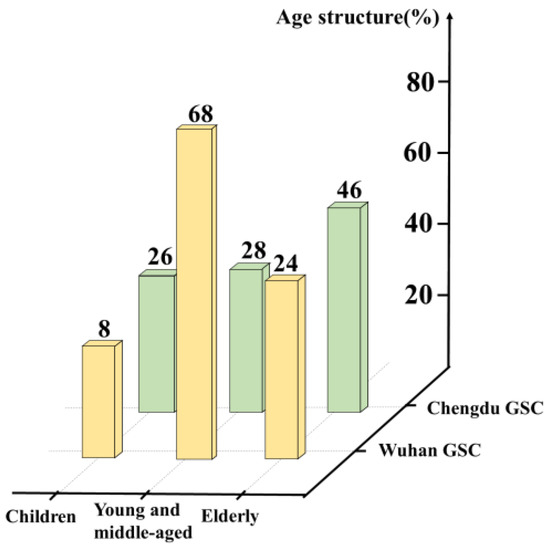

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of the user age distributions at the Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs. The predominant user demographic at the Wuhan GSC comprises young and middle-aged individuals, accounting for 68% of the total users, whereas at the Chengdu GSC, the largest user group was the elderly, constituting 46% of the user population.

Figure 1.

Age structures of users of Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs.

3.2. Spatial Structure Analysis

The Assessment Standard [29] for Healthy Building was utilized to elucidate the functionality of GSC POSs, encompassing elements such as comfort, fitness, social interaction, and service. Subsequently, the GSC POSs were categorized into four zones: nature, relaxation, social interaction, and service. These zones were further subdivided into four subzones in the questionnaire survey: hard pavement (pedestrian paths), green space (areas with vegetation and water features), utilities (parking lots, waste containers, bulletin boards, smoking booths, and other service facilities), and aesthetic structures (sculptures, pavilions, pagodas, and other artistic elements). A spatial analysis of the Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs is depicted in Figure 2, indicating that hard pavements constitute the largest proportion of the spatial layout, followed by green spaces, utilities, and aesthetic structures. The on-site investigation revealed similarities in the POS design between these two GSCs. For instance, both designs aim to portray a government accessible to the public through open spaces and to offer recreational spaces for local residents.

Figure 2.

Spatial structures of Wuhan and Chengdu GSC POSs.

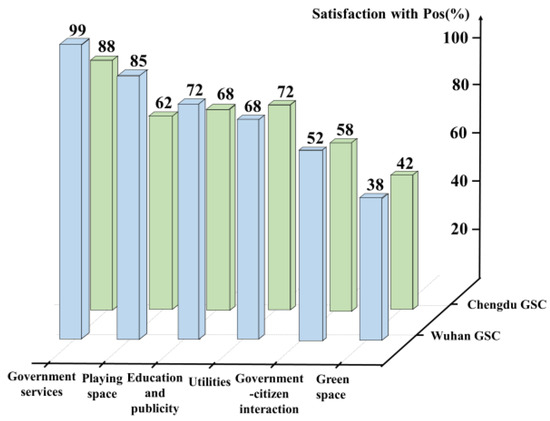

3.3. User Satisfaction Survey

User satisfaction of the two GSCs was examined from the six following aspects: government services, education and publicity, playing space, utilities, government–citizen interaction, and green space quality, as illustrated in Figure 3. The majority of the survey respondents expressed very high satisfaction levels with the government services provided at both GSCs. Education and publicity garnered the second-highest satisfaction ratings (72% and 68% for the Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs, respectively). Notably, there was a significant disparity in satisfaction ratings for playing spaces, with 85% and 62% satisfaction rates reported for the Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs, respectively. The lower user satisfaction rating for the green spaces at the Chengdu GSC may be attributed to a reduced green space proportion and distinct user demographics (children and the elderly constituted 32% and 72% of the Wuhan and Chengdu GSC POS users, respectively. Due to the significant disparity in personnel structure, the demand for fun in playing spaces had become more urgent, resulting in relatively negative evaluations). Social and green spaces at both GSCs received the lowest user satisfaction ratings, primarily due to a high prevalence of hard pavements and insufficient seating, walkways, and other structures essential for fostering social interaction, as well as limited green space allocation, which rendered the GSCs less appealing for relaxation, strolling, and cooling down.

Figure 3.

User satisfaction of Wuhan and Chengdu GSC POSs.

Based on the survey findings, the existing GSC POSs exhibited the following issues:

- (1)

- Green spaces: The availability of green spaces is closely linked to user well-being. The survey indicated that the users preferred the GSC POSs with a higher proportion of green areas, which offer a closer connection to nature.

- (2)

- Playing spaces: Approximately 50% of the GSC POS users resided nearby and utilized the POSs for leisurely activities and walking. These individuals expressed a desire for POSs with more engaging playing spaces.

- (3)

- Social spaces: The users expressed low satisfaction with the spatial layout of social areas. Therefore, the design of social spaces should take into account an appropriate spatial structure to enhance user experience.

4. Healthy Design Principles for POSs

4.1. Design Principles for Natural Spaces

Natural spaces integrate vegetation, natural terrain features, and water elements, serving as integral components of urban ecology. By providing a visually appealing landscape and a comfortable environment, these spaces can address both physiological and psychological health needs [30,31]. Furthermore, the creation of a microclimate through diverse plants not only enhances occupant well-being but also contributes to the improvement of the urban ecological system [32,33]. The design of natural spaces within a GSC POS can adopt various basic forms, such as symmetrical, open, or semi-open layouts, integrating natural elements to establish spatial boundaries that define distinct zones and contribute to the aesthetic appeal of the space (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic forms of natural spaces.

4.2. Design Principles for Playing Spaces

Playing spaces specifically refer to pedestrian paths for pedestrian traffic as well as designated sports areas, providing places and facilities for walking, exercising, and engaging in various activities, as depicted in Figure 4. Pedestrian pathways should accommodate high foot traffic, enhance access to the main structure, feature an aesthetically pleasing layout, and lead to enticing areas that inspire local residents to engage in physical activities [34,35]. By strategically situating sports fields and fitness apparatus, a comfortable and health-conscious environment for sports enthusiasts can be established, naturally encouraging exercise and bolstering user health through immunity enhancement and positive mental well-being.

Figure 4.

Different types of playing spaces.

For children, playing spaces should be designed with a spatial layout that matches the body size of children and with attractive colors. Child-friendly games that are both safe and captivating should be incorporated into the design of children’s playing spaces. For young and middle-aged individuals, whose schedules are typically packed during work hours, playing spaces should be designed to provide a spatial experience that is relaxing and can be used for different types of sports activities. Conversely, for the elderly, play spaces should be crafted with their limited mobility in mind, providing venues for gentle exercises like square dancing and tai chi. In essence, playing spaces should be thoughtfully designed to address the distinct requirements of various age groups and societal backgrounds [36], fostering a secure and inclusive setting for a wide range of communal engagements.

4.3. Design Principles for Social Spaces

Social spaces are meticulously crafted environments dedicated to fostering interpersonal communication, interaction, and relaxation. These spaces are created by harmoniously blending elements such as steps, seating areas, walkways, pavilions, and other architectural features with the natural surroundings, providing communal hubs for public gatherings and events [37,38]. By establishing expansive open areas conducive to group activities of varying sizes, the potential for collective interaction is heightened, enriching the vibrancy of local communities [39]. Social spaces should be structured in a manner that encourages healthy interpersonal connections. When the height (H) of buildings matches the spacing (D) between them, users of these public open spaces experience a sense of comfort and security; when D < H, users may feel confined, whereas if D > H, users might perceive the area as overly spacious.

5. POS Design Optimization of Wuchang GSC

5.1. Project Description and Problems

The Wuchang GSC is situated in the Wuchang District of Wuhan, in close proximity to the Xinhejie station on metro line #7. This project is a part of the Wuchang Ecological and Cultural Corridor initiative and features a collection of strategically positioned public structures. The overall site area of the project, encompassing commercial facilities and green areas, spans approximately 24,017.57 m2. The architectural design consists of a unified building complex, standing 16 stories above ground and 4 stories below ground level, with a total floor space of 141,314.97 m2. Within this complex are facilities for the GSC, administrative offices, commercial spaces, a community health service center, and the Wuchang District Information Center. The building’s POS features a ground-level plaza, a rooftop garden, and a sunken courtyard, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Wuchang GSC and the surrounding space.

Based on the above analysis, the existing POS has shortcomings in satisfying basic and reachable health needs. Specifically, the natural space has insufficient green space; for example, the roof garden has low aesthetic quality and insufficient shaded areas. These characteristics affect the aesthetic and ecological balance of the city and negatively impact the psychological and physiological health of users. Furthermore, the existing playing spaces lack diversity and fail to cater to various age groups and health conditions, thereby falling short of providing suitable venues for sports activities. As for social spaces, the current layout is congested, characterized by enclosed spatial configurations that constrain user movement and impede opportunities for social interaction.

5.2. Optimization of Natural Spaces

In order to tackle the issues related to inadequate green spaces and lack of variety, a set of enhancement strategies is proposed. Firstly, it is recommended that public green spaces be conceptualized as either partially enclosed or open areas, incorporating a layered layout featuring short trees and bushes to establish a welcoming and peaceful ambiance. The optimized design is dominated by large green trees, brightly colored small trees, and low shrubs. Furthermore, foliage and fruit-bearing trees with harmonious color schemes have been introduced to generate striking color contrasts. As an illustration, in the northern sector of the GSC, predominantly ginkgo and golden rain trees have been included, complemented by verdant tree borders predominantly consisting of young plants.

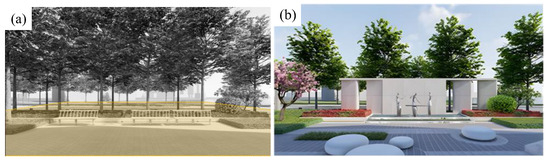

Tree planting techniques encompass clustered, sparse, and decorative forms. Clustered trees are predominantly positioned along building perimeters and corners, functioning to obstruct direct views into the structures, soften architectural lines, and establish secluded areas. Sparse tree arrangements are commonly found on lawns, offering expansive vistas and fostering an open ambiance. Decorative trees are typically situated within flower beds, tree basins, and containers. By predominantly incorporating these natural elements and a symbolic waterscape, the richness and variety of the landscape are enhanced, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Computer rendering of the entry plaza. (a) before and (b) after redesign.

The design of the green spaces incorporates a symmetrical layout to achieve a visually pleasing and well-balanced environment. Given the significance of the logo wall at the entrance of the POS for facilitating communication between the landscape facility and its users, and considering the natural surroundings of mountains and rivers in the Wuchang district, the logo wall was conceptualized with representations of these elements, utilizing curved forms. Constructed from granite, the wall is complemented by flower beds and artificial mountain features. Three layers of green borders adorn the logo wall, while symmetrical green hedges and designated parking areas for non-motorized vehicles flank its lateral sides. This new design enhances both the aesthetics and functionality of the spaces, providing users with a comprehensive understanding of the local natural landscape and traditional culture, as depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Computer rendering of the logo wall at the entry area. (a) considering the natural surroundings of mountains and (b) considering the natural surroundings of rivers.

As illustrated in Figure 8, the original roof garden lacks a contemplative area and visually appealing or shaded zones. The defining characteristic of roof gardens is that they are built on top of buildings. In contrast to conventional green spaces, inappropriately designed roof gardens can lead to serious safety hazards. Therefore, roof gardens should be planned following the safety-first principle and as natural, green, ecologically friendly, and sustainable spaces. Due to the limited soil depth available on rooftops, the design should primarily feature shrubs, flowers, and grass. This concept prioritizes structural soundness while aiming to establish an aesthetically pleasing and ecologically diverse green space. Moreover, pedestrian pathways are crafted using a blend of stepping stones and lawns. This holistic redesign notably enhances both the visual appeal and functionality of the roof garden, providing users with a healthier and more enjoyable outdoor environment. Considering that the roof garden has sufficient sunlight exposure, in order to improve the comfort of users resting or socializing in this space, shade or rain cover facilities should be added to the current optimization plan in the future.

Figure 8.

Computer rendering of roof garden (a) before and (b) after redesign.

5.3. Optimization of Playing Spaces

As outlined in Section 3, nearly half of the visitors to the Wuhan and Chengdu GSC POSs did not go there for business. They were mainly passersby, residents in the surrounding communities, and tourists. Feedback from users indicated a low satisfaction level with the GSCs, particularly regarding the availability of areas for group activities. The original design of the ground plaza at the Wuchang GSC shares similarities with the Wuhan and Chengdu GSCs, being spacious but lacking sufficient space for recreational activities. Therefore, it was optimized by focusing on providing space for healthy sports for different age groups.

For the elderly, a comfortable and safe environment has been created for recreational activities, such as tai chi, chatting over tea, and chess. For the young and middle-aged, a place is provided for them to participate in sports activities, such as power walking, jogging, and cycling, and multi-functional facilities for sports activities is also provided. For children, the playing space is designed to avoid overcrowding and facilitate the tracking of children, and bright and safe materials are used. Specifically, two open grounds of the Wuchang GSC were redesigned into two small playing grounds with grounds for sports, social, and relaxation activities and facilities for both high- and low-intensity exercises. Each playing ground faces a water-side landscape wall, which is fronted by a water pool and decorated with sculptures, thereby creating a more layered space. The attractiveness of the recreational, sports, and relaxation facilities has been improved by adding plants, thereby creating a space where users can feel close to nature. By integrating recreational facilities with a wavering green landscape, a more attractive playing space has been created. Furthermore, the pedestrian paths in the landscape are paved with dark and light grey natural stones, thereby increasing the color contrast, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Comparison of playing space (leisure area #1) (a) before and (b) after redesign.

Figure 10.

Comparison of playing space (leisure area #2) (a) before and (b) after redesign.

5.4. Optimization of Social Spaces

To rectify the issues of an unbalanced spatial layout, overcrowding, and enclosed spatial design observed in the original social spaces, a departure from traditional spatial morphology was undertaken. This transformation aims to establish a low-density open layered space, enhancing the visual appeal of the landscape and cultivating a more visually pleasing POS.

The spatial structure, encompassing both visual and functional dimensions, serves as a pivotal element in evaluating space quality and was fully considered during the redesign of the Wuchang GSC POS. The visual scale is defined based on visual perception. Generally, the vertical field of view for an average individual spans about 120°, with 50° above and 70° below the apparent horizon considered within the comfortable range, as depicted in Figure 11. A combined consideration of visual and functional scales in the design process culminated in an enhanced visual and functional experience within the Wuchang GSC POS.

Figure 11.

Illustration of comfortable spatial scale.

Figure 12 shows the array of public amenities and ornamental structures implemented within the Wuchang GSC. Essential public facilities, such as outdoor signage, communal seating, street lighting, pavilions, and other foundational elements, were strategically placed to foster social engagement. In crafting the design of directional signs, informational boards and site markers were strategically positioned at entry points and intersections along the pathways. The site markers at entry points are prominently displayed, succinct, and lucid, detailing the functions, services, departments, and pathways within the GSC.

Figure 12.

Computer rendering of public facilities and decorative structures. (a) Round seats, (b) square seats, and (c) long seats.

Public seating, a pivotal feature of outdoor communal areas, was meticulously designed with ergonomic considerations in mind. Long, square, and circular seating options have been made available to cater to different preferences. The design of the elongated seats drew inspiration from the U-shaped concrete structure, with a unique configuration mirroring the building’s form. Square seating arrangements have been integrated into the green spaces, constructed by assembling multiple granite slabs with greenery at the center. Circular seating designs, reminiscent of water droplets, have been strategically positioned in front of sculptures, offering users a vantage point to admire the surroundings and unwind in comfort. By setting up a reasonable resting stone bench, users are ensured to be at a comfortable social distance, and the form of the stone bench can be well integrated with the natural landscape, improving the interaction between users and the natural environment.

The illumination scheme of the POS encompasses a combination of road lamps and ornamental lighting fixtures. Road lamps have been strategically deployed not only as a safety measure but also to guide users along the pathways, positioned on the edges of roads, in expansive areas, and lining pedestrian walkways. On the other hand, decorative lights adorned the external façades of the building and the lawns. Given the governmental service character of the Wuchang GSC, modestly designed lamps with a height of approximately 2.5 m have been utilized, spaced at intervals of 10 m.

The decorative lights mounted on the building’s exterior walls are discreetly nestled within wall recesses, predominantly featuring a harmonious blend of cool hues in a minimalist color palette. Within the lawns, visually appealing low-level decorative lights have been incorporated to create a striking contrast against the tranquil and inviting ambiance of the rooftop garden, effectively delineating the pathways at night and bridging the transition between soft and hard landscaping elements. The optimized lighting design of social spaces has been added to meet the user’s needs for walking and resting in public spaces at night, as depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Computer rendering of lighting. (a) Decorative lights on walls, (b) road lamps, and (c) decorative lights on lawns.

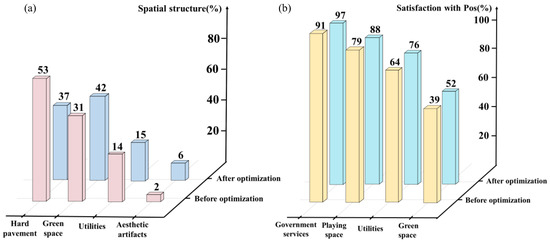

5.5. Optimization Effect and Discussion

Another questionnaire survey on the spatial design before and after optimization was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of optimization. The results are provided as follows. In the initial design, the ground plaza of the Wuchang GSC featured extended hard pavement, offering space but failing to cater to users of all ages and lacking space for social activities. Furthermore, the existing public activity spaces lacked diversity and failed to provide suitable areas for sports activities, rendering them unsuitable for users of varying ages. As for the social spaces, the original layouts have relatively enclosed spatial zones, constraining user mobility and opportunities for social interaction. The optimized survey results are shown in Figure 14. Through the optimization design of each space, the user’s satisfaction with the functionality of providing social and entertainment activities in the space is greatly increased, and the green space ratio on site is also significantly improved. As shown in Figure 14, the statistical data prove that the above design concept and implementation plan are effective and can provide references for relevant cases.

Figure 14.

The optimization effects on the Wuchang GSC: (a) spatial structure, and (b) decorative lights on lawns.

6. Conclusions

In this study, a thorough investigation and analysis of two typical GSCs revealed several key problems with the existing GSC POS designs: deficiency in green spaces, inadequate appeal and functionality of playing spaces, and unsuitable spatial configurations for social interactions. In response to these design challenges, a comprehensive set of modifications is recommended to revamp the Wuchang GSC.

- (1)

- In terms of natural space design, the problems of insufficient greenery and a monotonous landscape have been overcome. By increasing the green area and introducing diverse plant configurations, the new design not only enhances the natural atmosphere and aesthetics of the space but also provides citizens with more opportunities to get close to nature. Compared to the previous design, the new natural space places more emphasis on human experience and feelings, creating a beautiful and pleasant environment.

- (2)

- The renovation of playing spaces places greater emphasis on age-friendly design concepts. Diverse activity facilities and recreational areas according to the needs of different age groups have been set up. Compared to the originally open space that lacks vitality, the new activity space is more diverse and can meet the sports and entertainment needs of various groups of people, greatly enhancing the attractiveness and practicality of the space.

- (3)

- In the optimization of social spaces, the original closed layout has been broken and an open, low-density communication environment has been created. The new design is not only optimized for the visual and functional scales but also greatly enhances the comfort and social interaction of the space by adding humanized public facilities, such as signage and public seating.

In summary, by integrating Maslow’s theory into the comprehensive optimization of the outdoor public space of the Wuchang GSC, a healthier, more functional, and humanized public space has been created, overcoming the shortcomings of the original design. These improvements not only enhance the quality of life of citizens but also make positive contributions to the sustainable development of the city. The optimized effect was validated through user satisfaction surveys. However, the evaluation of the effectiveness of the current design concept and scheme was only based on a relatively simple scoring system. In the future, more comprehensive data analysis methods will also be used to track and investigate the psychological and health status of users in order to evaluate the feasibility of optimizing design concepts and provide a basis for the widespread promotion of this design method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P.; Formal analysis, W.P. and X.D.; Investigation, L.Z.; Project administration, Y.H.; Resources, Z.Z., Y.W. and X.D.; Software, X.W.; Supervision, T.Y.; Visualization, L.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.W., Y.H. and T.Y.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W., X.W. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research on landscape optimization and low-carbon design of urban public space: G23-12-S.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Tiancheng Yang and Xinyan Wang were employed by the company China Railway 18th Bureau Group Building and Installation Engineering Co., Ltd. Author Zhengming Zhang was employed by the company Ausspec Landscape Planning and Design Co., Ltd. Author Liang Zhu was employed by the company CITIC General Institute of Architectural Design & Research Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallie, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guite, H.F.; Clark, C.; Ackrill, G. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Publ. Health 2006, 120, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, P.; Wang, N.; Hu, M.; Roberts, J.D. Sustainable, Healthy Buildings & Communities. Build. Environ. 2020, 174, 106806. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, Y. Evaluating the disparities in urban green space provision in communities with diverse built environments: The case of a rapidly urbanizing Chinese city. Build. Environ. 2020, 183, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Ruggeri, K.; Steemers, K.; Huppert, F. Lively social space, well-being activity, and urban design: Findings from a low-cost community-led public space intervention. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Jones, D.S. Pandemic Stricken Cities on Lockdown. Where Are Our Planning and Design Professionals [Now, Then and into the Future]? Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, M. Contemporary public space, Part Two: Classification. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M. Increasing walking: How important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Badland, H.; Hooper, P. Developing indicators of public open space to promote health and wellbeing in communities. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 57, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Hooper, P.; Duckworth, A.; Bolleter, J. An evaluation of the policy and practice of designing and implementing healthy apartment design standards in three Australian cities. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluyssen, P.M. Towards new methods and ways to create healthy and comfortable buildings. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between public open space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turel, H.S.; Yigit, E.M.; Altug, I. Evaluation of elderly people’s requirements in public open spaces: A case study in Bornova District (Izmir, Turkey). Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Jiao, S.; Zhang, R. High-Density Communities and Infectious Disease Vulnerability: A Built Environment Perspective for Sustainable Health Development. Buildings 2023, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Z. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Urban Density in China and Analysis of Urban High Density Development: From 1981 to 2014. Urban Dev. Studies. 2019, 26, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Shen, M.; Musa, S.S.; Guo, Z.; Ran, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chong, M.K.C.; He, D.; Wang, M.H. Inferencing Superspreading Potential Using Zero-Truncated Negative Binomial Model: Exemplification with COVID-19. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Kashem, S.; Baker, D.M.; González, S.R.; Lee, C.A. Exploring the Nexus between Social Vulnerability, Built Environment, and the Prevalence of COVID-19: A Case Study of Chicago. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Peng, Y.; He, H.; Wang, M.; Feng, T. Built Environment and Early Infection of COVID-19 in Urban Districts: A Case Study of Huangzhou. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y. Healthy campus by open space design: Approaches and guidelines. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Yang, F. Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: Design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S. Open space: People space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.D.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health effects of viewing landscapes—Landscape types in environmental psychology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.X.; Zhu, Y.; Passe, U. Modeling and data infrastructure for human-centric design and operation of sustainable, healthy buildings through a case study. Build. Environ. 2020, 170, 106518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; O’Brien, W.; Hong, T.; Feng, X.; Gunay, H.B.; Tahmasebi, F.; Mahdavi, A. Occupant behavior modeling for building performance simulation: Current state and future challenges. Energy Build. 2015, 107, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C.; Dogan, T.; Jakubiec, J.A.; Rakha, T.; Sang, A. Umi-an urban simulation environment for building energy use, daylighting and walkability. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Chambery, France, 25–28 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, T.; Gunn, L.D.; Christian, H. Quality of public open spaces and recreational walking. Am. J. Publ. Health 2015, 105, 2490–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- T/ASC 02-2016; Health Building Evaluation Standards. The Architectural Society of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, K.; Auld, C. Leisure, public space and quality of life in the urban environment. Urban Pol. Res. 2003, 21, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Hooper, P.; Foster, S. Public green spaces and positive mental health–investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 48, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, L. Studies of thermal comfort and space use in an urban park square in cool and cold seasons in Shanghai. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Underwood, S.H.; Masters, J.L.; Manley, N.A.; Konstantzos, I.; Lau, J.; Haller, R.; Wang, L.M. Ten questions concerning smart and healthy built environments for older adults. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Chan, O.F. Understanding the long-term effects of public open space on older adults’ functional ability and mental health. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Thompson, C.W.; Alves, S. Associations between neighborhood open space attributes and quality of life for older people in Britain. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H. A path analysis of outdoor comfort in urban public spaces. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Luo, P.; Wang, T. Screening visual environment impact factors and the restorative effect of four visual environment components in large-space alternative care facilities. Build. Environ. 2023, 235, 110221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Wen, J. Experimental study and theoretical discussion of dynamic outdoor thermal comfort in walking spaces: Effect of short-term thermal history. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 109039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).