Abstract

This article focuses on the issue of the urban development of cities and their residential development from the perspective of spatial planning. Spatial planning fundamentally determines what kind of construction is feasible in cities. However, spatial plans often do not consider spatial limits, which often go against the proposed ways of using the given sites, or make their use fundamentally difficult, for example, by disproportionately increasing of the costs of residential construction, when it is necessary to remediate old burdens in the defined locality. The subject of the presented research was to examine the possibility of establishing an Index of Residential Development (IoRD), which evaluates the possibilities of residential development in the territory of urban agglomerations. The aim of the research, in the form of establishing of an Index of Residential Development (IoRD), was to assess how it is possible to consider spatial limits associated with residential construction in urban intravilanes in order to identify the objectives of further spatial development planned by cities. Subsequently, the partial aim of the research was also to create a usable tool for support in the decision making of development organizations on the location of their project in a given space. Based on the results of the research, it was deduced that the limits associated with the residential development in intravilanes based on the IoRD could be considered. Clear links were also shown between the limits in the territory and the impaired possibility of construction in cities with zoning plans, which did not respond to the limits in the territory by adding other design zones, or completely ignored them. Although the methodology for determining of the Index of Residential Development (IoRD) was verified due to the availability of data in the case study carried out in the Czech Republic city of Brno, the methodology is applicable to any urban agglomeration even outside the Czech Republic when fulfilling the conditions defined in the article.

1. Introduction

Every person or any animal on a planet either has or is looking for a place to live. In humans, we refer to this as housing. Human basic needs, in particular, are very much related to housing. Few people would say that housing does not matter, that they do not care, and that they do not have to go home and go to bed tonight. Housing as such is part of basic human needs. Human needs motivate because they are the means by which it is realized. The opinion of Abraham H. Maslow (1908–1970) was that man, because of his internal balance, must satisfy his needs from the lower, or basic, to the higher, which are connected with being and determine him as an individual being who becomes part of society. Human needs are defined from the lowest (psychological) to the highest (self-actualization), according to A. H. Maslow [1,2].

The very lowest needs include the physiological ones that arise from biological nature. All other animals on planet Earth have these needs and they include breathing air, receiving food, the need for sleep, the need for reproduction, and more. If one were to dispense with physiological needs, one simply would not be [2]. This article, however, is interested in the second level of needs, the safety, which is sometimes also referred to as safety and security. Where does one feel safe? Most people would most likely answer: at home. It is this need that relates to protecting oneself from external and unknown influences. One naturally seeks one’s security, and this is found in a familiar and inhabited environment. Man, by his nature and by the nature of his needs, wants to survive in the long term and seeks a fixed point [2]. He wants to avoid the dangers of uncertainty and the unknown, his nature tries to keep him safe from the possibility of being hurt [2].

In order to provide for oneself, one’s family and offspring, one needs to have a shelter—“home”. In our environment, this is then a human dwelling, most often a family house or flat. From the smallest human shelters to luxury villas, it is always a human dwelling, which is related to the aforementioned basic need for safety [3]. There is a really big difference between what is merely the satisfaction of the need for safety and what is already a status issue. This means the excess and presentation of the individual himself and falls subsequently into the needs of level 4—Esteem [2].

In the environment of Central Europe, e.g., in the case of the Czech Republic, where it is a republic undergoing transformation since 1989 both socially and economically, it is evident that the changes that have been taking place since 1990 have been evolving the perspective of individuals on how to provide for housing needs and have been transforming the residential property market for more than 30 years [4]. In the 1990s, a commercial housing market emerged in the Czech Republic, helped by the following facts:

- the parliament approved previously prohibited personal ownership,

- the state housing stock became largely (up to 28% is reported) the property of people (most often tenants at the time),

- since 1991, restitutions of property seized by the previous totalitarian regime have taken place,

- construction enterprises have been privatized,

- the mortgage system has become operational [4,5].

All the aforementioned elements, which were forbidden or simply did not exist under the totalitarian regime before 1990, have created a completely new, Western view of the treatment of real estate in general and residential property in particular. Since 1990, the “burden” of building new residential properties has passed from the majority to private entities, there has been a situation where, given the prices at the time, the level of inflation around 10%, and other influences, the possibility of new construction was very limited, especially the construction of affordable social housing, the boom of which was recorded, for example, in the 1980s [4]. The impact of the lack of affordable housing, whether for homeownership or rental, caused price increases in both the rental category and the sales category. Demand continued to grow with the need to live, but the supply was very limited. Along with this, a socio-economic problem arose in the form of the threat of unaffordability of housing from the perspective of family budgets [4].

In general, there has been a tendency towards private ownership in the Czech Republic since the 1990s as far as residential properties are concerned [6]. Unlike, for example, the Federal Republic of Germany, it is an established standard in the Czech environment to own an apartment or a house. Kalabiska describes it as follows: “The ownership of residential property is one of the key components of household wealth. It offers an opportunity to accumulate assets and build wealth and thus through wealth effect influences household consumption and investment decisions” [7]. In such a case, however, it is the mortgage boom that becomes a big risk. With mortgages, the ownership of the dwelling became available for low-income households. Since the possibility of owning your shelter is often the only option to have real estate in the family, this, combined with the crisis years, is a big threat to the real estate and banking market as well as to the households themselves. This manifested itself in the Czech Republic, for example, in 2005, when the most significant period of mortgage expansion occurred even among low-income households. At that time, it was possible to receive mortgages with Loan of Value up to 100% and another risk was not proving the amount of income, and thus the ability to pay the mortgage [5].

In 2023, there was a braking effect that had a major impact on the trend of private property. In particular, there was an unavailability of private property and an impossibility for the ordinary citizen to obtain a mortgage. The Loan of Value conditions (e.g., 60% today) are set up, together with other protection mechanisms, to protect low-income households on the one hand, but to prevent them from acquiring their own residential property on the other. If a person has no other way to finance the purchase of a residential property, he or she reaches the point where he or she has to put up with rental housing. A major social problem can then be the constant shortage of residential construction, which has been going on since the 1990s. This can result not only in the impossibility of obtaining one’s own home (meeting the conditions for a mortgage), but also in the face of pressure on the rental market for residential property, in the increase in rents [7,8].

Accepting that a person will not be able to afford their own housing and that their basic need for security will be met in a foreign property is one thing, but balancing on the edge of the sustainability of the family budget in terms of the level of rent and at the same time the increasing costs of housing services is another thing that can have a very negative effect on the whole society [3].

All of the above refers to the demand side, the customer, the buyer, the tenant. Its behavior is of course influenced by the other side, the supply side. The OECD’s findings also show that there has been a long-time sharp rise in prices of residential and other properties in the Czech Republic. The fact is that just as property prices are rising, so are rental prices. These, together with the high operating costs of housing, then become a problem for Czech households. The OECD points out that low supply is one of the biggest causes of the disproportion between supply and demand of residential properties [9].

Housing unaffordability is the biggest issue especially for young people and so-called “millennials”. They come to a post-socialist over-homeownership environment in which they are confronted with a housing crisis and have to look for a way out of it to meet their needs. However neoliberal today’s millennials may be, they still aspire to be the majority of owners of residential property [10].

A way out of this socio-economic problem could be found in adding a sufficient amount of accessible housing to Czech households. However, the local conditions of the Czech Republic are fundamentally opposed to this. The solution must be sought at national, but also local, level [9]. Czech laws and standards must create suitable conditions for new construction and land-use planning must work with suitable areas, in which it is possible to carry out the given residential development. Often there is a phenomenon, where a territory designated for a certain functional use (in this case housing) is practically unstoppable, because it may be such a degraded or encumbered area that its development would be so costly that it does not occur for these reasons [11].

It is necessary to look for a tool that could evaluate urban planning, or the land-use plans themselves, and that could help to municipalities to know whether their land-use plan is well prepared for the development of residential housing, and on the other hand, such a tool could help investors to know whether it is appropriate to enter a given city with their investments in the development of residential properties. Such a tool could lead to higher effectiveness of land-use plans and consequently to a reduction in the housing crisis, which spills over into a social crisis. The presented research is therefore focused on identifying the requirements for creating such a tool and, following the previously known methods, to propose and subsequently verify such a procedure that would provide the above-mentioned functions, either from the point of view of the municipality or from the point of view of the developer. The aim of this article is to present a proposal of such a tool—the index and to verify this proposal and its functionality on the case study. This tool was developed as the Index of Residential Development showing the possibility of residential development in a given land registry, which is solved by a specific land-use plan. As a part of the verification, this tool is applied to city of Brno, the second largest city in the Czech Republic, and on the basis of the results obtained, the city is analyzed and possible solutions are proposed for it leading to a reduction in the housing crisis and a greater development of affordable housing.

2. Present State References

If we are talking about a tool that would make it possible to evaluate the possibility of development from the perspective of residential construction, the closest way to this approach is an assessment from the perspective of social factors or urbanism. Tools and indexes evaluate the territory from the aspect of an urban development with the understanding that there is an assessment of the structure of the territory. Several such indexes have been developed since 1960. There was a search and evaluation of cities from the perspective of their development based on spatial expansion over time. Approaches focused on built-up areas and their gradual development, shape, fundamental changes in places, such as changes in riverbeds and the management of rivers. This evaluation is part of the so-called urban geography [12]. It focuses on different assessments from the perspective of the type of spatial development of human settlements. For example, the Index of the Fractality of Cities has been solved on this principle [13], which brings the use of fractals into the assessment of cities. However, there are other types and methods of assessment—the indexation of cities on the basis of their shape. Fractals bring new functions that have not yet been observed by other methods of monitoring of the urban shape of human dwelling. The index of the fractality of cities is useful, for example, in archaeology, in tracing sites from different periods in space and time in historical parts of cities [13]. Fractals are applicable from three aspects: degree of space filling, degree of spatial uniformity, and degree of spatial complexity. Fractals can thus be used as a space-filling index, which evaluates the replacement of urban spaces by new structures or structures. Hierarchies in cities, which often have cascading structures, can then be described using multi-fractals. Fractal geometry allows a different view of urban development in [14]. Fractals are able to consider, for example, socio-economic elements within the built-up parts of the cities and thus bring another aspect into the evaluation of cities using fractals [15]. The focus of this article is not on socio-economic benefits as it is from the point of view of the articles mentioned above. However, fractals are a very useful tool that can be focused precisely on the link between urban development from the point of view of built-up and socio-economic elements.

In Latin America, there is an uncontrolled development of urban peripheries. This takes place outside of any regulation or oversight by state authorities and institutions. Due to the rapid development and relocation of residents to large agglomerations, there is a rapid increase in new residents looking for a place to live. Quantifying and characterizing of these New Urban Peripheries is a big deal [16]. This situation of the unregulated urban sprawl has arisen on the basis of the fact that there is a great demand for residential properties and at the same time they are inaccessible to the poorest sections of the population. The only way then is the informal way of development in New Urban Peripheries, but these entail considerable problems in terms of safety and health risks, environmental destruction and also inappropriate hygiene features for local residents [17]. New Urban Peripheries evolve differently in different cities. Their tracking is carried out using GIS and Geographically weighted regression [16]. Although the data thus obtained show uncontrolled urban development without any regulation, the aim of this article is to verify ways of managing legal urban development on suitable areas and this approach is therefore not appropriate, especially due to the differences in the legal environment between Latin America and Central Europe.

When looking for a suitable development index, the reader can easily come across the social side of things. Housing is, after all, largely a social policy. Indexes created to measure social values already exist, such as the Human Development Index. This index is aimed at assessing the development of the state as a whole from the point of view of society. It does not only assess economic growth as such. This index comprehensively assesses the length and quality of life, the level of education and living standards. Housing is also a part of living standards [18]. Housing policy generally has a major impact on the development of man and human society. This is also evident in the risks arising from the wild urban development in Latin America [16]. The fundamental impact of decent housing was verified in the Impact of Employment Quality and the Housing Quality on Human Development in the European Union [19]. It assessed the impact of involuntary part-time work and housing quality on the Human Development Index. In this study, the authors concluded that there is also a low level of the Human Development Index in the countries of the European Union, where there are many involuntary part-time workers, which include: Romania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland, and others. Similar countries also have high levels of overcrowding and this study did not confirm the hypothesis that overcrowding would limit their capability to do and be what they really want [19].

However, the measurement of the Human Development Index and its modification do not correspond to the objectives of this article. The Human Development Index measures the macro-economical view of larger units. During looking for and assessing the residential development, it is necessary to focus on the lower level, optimally the level of cities and self-governing territorial units. Although the conditions for residential development are based on national norms and laws, their implementation in practice takes place at the level of cities. The objectives of this article are approximated by approaches such as those applied by Soyoung Park and collective in the article “Prediction and comparison of urban growth by land suitability index” mapping using geographic information system (GIS), frequency ration (FR), analytical hierarchy process (AHP), logistic regression (LR), and artificial neural networks (ANNs) in case study of South Korea [20], where several social, political, topographical, and geographic factors were used. These factors were used to predict the development of urban land-use. There are many models that can predict further spatial development based on past-to-present observations. However, input variables that refine such modelling are essential [21]. However, approaches based on these methods are very subjectively and unilaterally limited due to the need for accurately determined input data. In particular, quantitative methods can greatly simplify outputs and then the models thus obtained are unsuitable for predicting future land-use in urban planning [20].

S. Park in his article used the Land Suitability Index (LSI), which was supplemented by topographical, geographical, and social factors [20]. The indexation thus set was used for the whole Republic of Korea (South Korea) and data from 1985 to 2005 were used as inputs. In general, there was a 27% increase in population during this period and a significant 55% increase in residential land-use and a rise in land-use for infrastructure (roads). The results led to the selection of a suitable urban land-use grown prediction model for the whole state [20]. Again, there is a clear macro-economic use for the whole state department. The indices, which are focused on urban development at the level of cities or smaller units within states, are based primarily on inputs at a level that more objectively assess local conditions. Such indicators include the Urban Sustainability Index (USI), developed by the European Commission, which focuses on the sustainability of urban areas. Another such indicator is the City Prosperity Index (CPI), developed by the United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat) [22], or the Gross City Development Index (GCD-Index) presented by Mario Arturo Ruiz Estrada and Donghyun Park in his article entitled “The Application of the Gross City Development Index (GCD-Index) In Tokyo, Japan” [23]. These focus directly on the prosperity of cities.

In general, the sustainability of cities is an essential element of the future of human civilization as we know it. As this article focuses on the development of residential development and its evaluation within cities, there can be no neglect of basic indicators assessing of the sustainability and prosperity of cities. In the world of the 21st Century, it is really important for its inhabitants whether the place they live provides not only sufficient personal development, but also a long-time horizon for them to live happily. If one can, one tries to avoid a bad environment (pollutants, waste, green-house gas), a bad school environment, inaccessibility of employment, bad or insufficient culture, criminality, and others around their place of residence. Avoiding these problems and offering suitable places to live and to create new residential zones is something that a well-run city should aim for [24]. The European Union has an urban agenda for the EU, which is based on a focus on the sustainable development of European cities. The main objectives were set out in the New Leipzig Charter and include, for example, efforts to create cities that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. A major objective is to ensure affordable housing. Efforts to adapt urban policies to people’s daily lives are evident [25].

Indexes are often adjusted to show the observed facts more accurately, because their usability is degraded by local conditions, which are so different across (even only) Europe that without more precise indicators, very inaccurate results would be determined. For example, in the article “Urban sustainability assessment and ranking of cities”, the emphasis is on the adjusting of indicators so that they serve to evaluate cities rather than to evaluate states. For example, the City Prosperity Index (CPI) uses 17 indicators in its basis, which are compiled into six blocks: productivity, infrastructure development, quality of life, environmental and social inclusion, environmental equity, and urban governance and sustainability. The authors of this article use the approach of sensitivity analysis to search for indicators that influence most in a given city. The result is an increase in efficiency in sustainable approaches of individual cities [22]. In contrast, Arcadis has its own way of evaluating it, referring to it as the Sustainable Cities Index (SCI). The most recent publication on this topic was published by Arcadis in 2022. In its evaluation it considers three basic pillars:

- Planet Pillar (environmental factors),

- People Pillar (social performance),

- Profit Pillar (business environment).

The absolute winner for 2022 in this ranking was Oslo, which scored the most points in the ranking in Planet Pillar. The Profit ranking also includes a housing affordability rating. However, the construction options themselves are hard to read in this index [26]. A multidimensional view of urban development is provided by the aforementioned article dealing with the Gross City Development Index (GCD-Index). This index assesses socio-economic–political–technologic performance and, in a broader perspective, this index confirmed, for example, that the improvement of welfare of the city residents depend on a broader range of factors. Inputs were assessed on the main structures, which include: economic and finance, social, politics, infrastructure and housing, and the others [24]. The interdependence between urban development and housing policy is considerable. Not only must there be a balance between accessibility and sustainability, but other elements that directly influence other social and urban measures must also be monitored. School accessibility, transport connections, technical infrastructure, and others all influence how and where to develop residential development [24]. Otherwise, it can also be said that the development of human settlements has an economic, environmental, and social aspect [27].

Urban development is directly dependent on urban planning and construction. Land-use planning is often widely criticized, especially because of the very limited possibilities of its use in practice and because of the inappropriate set of conditions [28]. In the Czech Republic, there is a shortage of affordable housing on the market. There is generally little supply and big demand [7]. Moreover, developments in recent years show that house prices are rising rapidly, even disproportionately to wage growth [29]. In the urban environment, we can think of the urban plan as an intermediary, or perhaps even a supplier, of the housing system. The city thus plays a crucial role in housing market dynamics, because it creates the conditions and sets the rules through the urban plan. Today, for example, there is an obvious tendency to combine both urban densification—building up to a height and with it the creation of blue-green infrastructure. This is achieved in modern cities through high-rise construction and open spaces around buildings [30].

The nature of the land-use plan is passive, it sets criteria for the use of the land and the builder has to meet them. Especially in the case of new residential construction, the builder encounters even wider conditions for project preparation and its permit in negotiations with the local authority [28]. This wide range of conditions is then reflected in the quality and cost of the residential construction project, as well as in the costs of the construction itself.

The concept of Smart Cities is also an important approach in the planning of spatial development. For example, publication [31] presents an analysis of best practices in the construction of smart districts with a focus on the possibilities of building a specific smart district Špitálka in the Czech Republic. The publication presents both a conceptualization of smart city and theoretical approaches to smart districts [31]. Publication [32] then deals with the concept of the so-called 15-min city as an alternative for sustainable urban development, where the goal of the concept is not only the implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures in the context of climate change and the transition to low-carbon to zero solutions, but also the reduction in inequalities between different parts of cities. The “15-min city” may be defined as an ideal geography where most human needs and many desires are located within a travel distance of 15 min [33]. The model is currently being applied to major European cities such as Barcelona or Paris and is being developed as one of the possible solutions to significant decarbonization of cities. The model approaches spatial planning through a humane socio-economic dimension, thus benefiting urban communities, and can be used as a potential solution to restructure cities for greater sustainability, inclusion, and economic equity [34]. The issue of applying the 15-min city model in the context of a post-pandemic society in cities is addressed in more detail in [35]. The 15-min city principles are principles that are not primarily dependent on a zoning plan, but are principles that use a zoning plan as a cornerstone for creating a quality place to live. The very principles of a 15-min city can be applied within a zoning plan with the help of an appropriate allocation of functions within a zoning proposal. Developer projects tend to focus not only internally, but also on the external environment. A well-prepared developer project not only works with a basic function (for example, residency), but complements it so that other additional functions can be included in the project, creating an environment for a good life along with the 15-min city principle.

The process of spatial concentration within the relative deconcentration of the population, as part of intra-urban suburbanization, is subsequently presented in publication [36].

The research gap resulting from the carried-out research lies in the absence of a comprehensive tool for planning authorities and development companies focused on identifying suitable development areas with regard to territorial limits occurring in the territory. In addition to the previously defined objectives, this article aims to identify the limits that stand between the defined use of the territory for residential construction by the zoning plan and the realization of the construction, which would lead to the fulfilment of the long-time objectives of the cities in the form of adding of new residential properties—flats—to the real estate market. These are then assessed and appropriately transformed into an index, which will be usable by the municipalities for assessing whether the zoning plan is correctly set up, and from the perspective of investors, who can thus evaluate the suitability of entering the real estate market of a particular city and start investing in the development of residential properties.

In relation to the objectives and partial objectives mentioned in the previous part of the contribution, the following research question can be formulated: “How is it possible to take into account the territorial limits associated with residential construction in intravilanes of cities for the purposes of further planning of the zoning by cities and supporting the decision-making of development organizations on the location of their project in a given location?” The answer to the research question is intended to provide a solution to the identified problem. The problem was described in more detail in the introduction of the paper and consists in the current, rather complex, identification of suitable areas for development of the territory in the intravilanes of cities, both from the point of view of the municipality as the developer of the master plan and the developer.

3. Methodology

In order to monitor the possibilities of development in residential areas of land-use plans, the authors have chosen an approach in which they are based on the limits of the given area. The limits determine the level, according to which the land laid down in the land-use plan can be used in a defined way and residential buildings can be built on it. The theoretical support of the applied methodology consists in the research carried out, which identifies the current state of the issue and the methods used. The proposed methodology follows the principles of the preparation of land-use plans using GIS, including the methods of specifying the territorial limits specified in the individual land-use plans. The subsequent evaluation of the land-use limits, including the determination of their weights, is then based on structured interviews with experts on the issue.

3.1. Territory Limits

Territorial plans are currently processed as graphic information systems, which contain various information about the monitored area. Territorial plans in the Czech Republic cover the whole of its territory and are subdivided according to administrative units—territorial self-governing units. The individual layers of territorial plans most often display information about the use of the territory, which entails the subdivision of the whole territory into functional areas. These are further subdivided into areas that are already stabilized (which should not be fundamentally changed) and functional design areas (which are expected to change the use or intensity of the use). Another part of the territorial plan is the concept of transport infrastructure, which shows in itself both already functioning transport corridors and expected changes and new construction of transport infrastructure. Each of the functions incorporates other uses in order to avoid a monofunctional use that would not be suitable for the future functioning of these parts of the cities. Along with this, the master plan is also a carrier of a complete overview of technical infrastructure, which consists in particular of the management of existing and planning new engineering networks. Last but not least, the master plan also shows, for example, protective regimes, which may include, for example, old ecological burdens, protection zones of airports, and others [37]. If we want to evaluate the possibilities of residential development in a particular city, it is therefore the best to proceed to the evaluation of the limits arising from the given territory. These territories establish a basic requirement for use, which is complemented by other functions that promote appropriate development. These are the most suitable to collect through the GIS for a particular zoning plan. Like the GIS of a zoning plan, it uses, e.g., [20]. It is therefore a detailed activity in which it is necessary to go through all areas of the master plan that relate to housing and to record the relevant limits for each area.

3.2. Evaluation of Acquired Limits

Since there are many limits in land-use plans, it is necessary to mark them according to the degrees of influence on residential development. Research processors work with a three-stage scaling by including in level 1 areas that are not, or are the least, limited, and these limits do not affect them. In level 2 processors include those areas that are burdened with local limits, but according to best practice these limits do not have a fatal impact on construction. Rather, it is only a deterioration of the permitting process and an increase in construction costs within acceptable limits compared to level 1 areas. In level 3 there are included those areas that are heavily burdened with local limits. It can be either a combination of multiple level 2 limits or limits that have a large impact on the permitting process (for example, adding additional separate permits) or carry a large burden in terms of increasing construction costs. These are limits where investors strongly consider whether to enter a given location with their investment intention. An overview of the limits is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of limits.

After subtracting all data, a comprehensive database is developed, in which all areas for residential design zones have been evaluated by a specific level of limits. This database has been sorted by the processors according to smaller territorial units of individual monitored cities—cadastral territories. The database always contains a division into cadastral territories and an inventory of all areas that permit the construction of residential properties (each spatial plan may have a different name for these areas, therefore, for each city these areas are sorted by individual types), this inventory is specifically characterized by the size of the area in m2 and a description of individual types of limits obtained empirically from the GIS. The database of areas is then grouped into summary results according to the types of limits that have been basically identified as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Types of limits.

3.3. Data Evaluation and Determination of the Index of Residential Development

The authors determine the Index of Residential Development (IoRD) on the basis of the data collected on housing areas. If the authors evaluated other types of areas (industrial, commercial), they could determine the Index of Industrial Development or the Index of Commercial Development. For the calculation of the Index of Residential Development, the relation (1) is used, which considers the shares of individual areas assigned to the respective level of limit.

ArL1 … Low Limited Residential Design Area [m2]

ArL2 … Medium Limited Residential Design Area [m2]

ArL3 … High Limited Residential Design Area [m2]

Ar … Total Residential Design Area [m2]

The relationship (1) evaluates three types of limited areas and assigns them a coefficient of 1.0 for areas that are not limited, so they are fully usable. A coefficient of 0.5 is used for areas that are limited, but not fundamentally, and a coefficient of 0.0 belongs to areas that are heavily limited. IoRD results can reach values between 0.00 and 1.00, with 1.00 being the best possible value and 0.00 being the absolute worst achievable value.

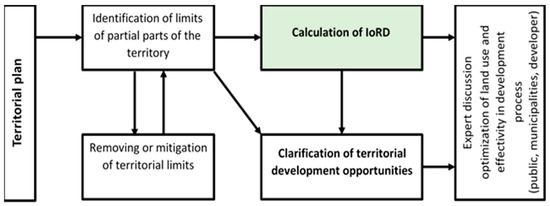

The IoRD is an indicator designed to demonstrate the development potential of a territory in relation to the territorial limits associated with a given territory. Based on the results of the IoRD, a discussion will then take place between the municipality, the developer and the public on the optimal use of the evaluated territory. The role of the IoRD in the decision-making process on the optimal use of the territory is illustrated in the following Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The role of the IoRD in the decision-making process.

The IoRD is therefore an index that simplifies the orientation in the development potential of sub-territories within municipalities and serves as a basis for optimal use of the territory with regard to the needs of all stakeholders. It can thus be concluded that the use of the IoRD in the process of identification of development potential will contribute to increasing the quality of life in the evaluated locality as it will allow a quality and objective assessment of the possibilities of the territory in terms of further development.

4. Results and Discussion

The results of the implemented research are demonstrated in the case study. For the Index of Residential Development application, suitable cities in the Morava region within the Czech Republic have been selected, although the defined methodological approach is applicable to any city, even outside the Czech Republic. The existence of a town planning plan is crucial here. The basic requirements for the suitability of a city have been defined with regard to the possibility to best capture possible variants of a town planning and thus to best verify the general functionality of the proposed approach. The key requirements are therefore the population size and the availability of GIS within town planning for the possibility of appropriate work with input data. At the same time, suitable towns have been selected for the river flow through them (not necessary condition for the Index of Residential Development application). The city of Brno, the second largest city in the Czech Republic with a total population of 382,405, was selected for the case study.

4.1. Brno—The Case Study

The city of Brno was chosen as the first and the largest of the cities assessed. This city has great development potential and it is a regional city that draws residents from a wide area into itself. This city is heavily affected by suburbanization and suffers from a lack of housing capacity. The cadastral subdivision of the city allowed its division into smaller units and the assessment of its individual cadastral territories, subsequently it was evaluated as a whole. The cadastral subdivision of the city is available in the publication [38].

The obtained data from the Brno city planning (Table 3) illustrate the results, which demonstrably describe less than half of the areas designated for residential construction without limits for development.

Table 3.

Database—Brno.

The data was then substituted into Formula (1) with the following inputs:

ArL1 = 3,144,354 m2

ArL2 = 1,489,786 m2

ArL3 = 2,241,891 m2

Ar = 6,876,031 m2

The resulting value of IoRD for the city of Brno is 0.57.

4.2. Discussion

By establishing an IoRD for the city of Brno, an insight into the quality of these territories and their spatial plans for residential development has been gained. Territorial plans are very complex tools that prepare the future development not only of cities, but also of all areas adjacent to them. However, this tool cannot always meet all ideas about spatial planning from the perspective of the construction itself. The results, which were obtained in a case study, show how the chosen residential design zones are prepared for construction, how much the selected plots of land are complicated for the permitting process, and the construction process from the perspective of costs.

The same procedure as in the case of the city of Brno was applied to two other Czech towns situated in southern Moravia, namely the city of Olomouc (100,514 inhabitants) and the city of Jihlava (51,125 inhabitants). The results of evaluated cities are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Index of residential development.

The results are surprising compared to the original assumptions. One of them was the assumption that the city of Brno would have the smallest IoRD of the monitored cities. However, this assumption was not fulfilled, as from the point of view of the monitored IoRD, the city of Brno achieved the best results. The city of Brno wins because of its vastness. Its territory is more than twice as large as the territory of Olomouc and Jihlava, as shown in Table 5. This plays into the hands of town planners in choosing much more Residential Design Zones in the peripheral parts of the city and thus preparing construction more often in greenfields.

Table 5.

Central and peripheral residential design zones.

The city of Brno has the smallest share of the Residential Design Zone Areas in the central part of the city, despite its area being twice the size. This may be the result of the already excessive use of areas and/or shortcomings in view of the age of the Brno zoning plan, which dates back to 1994 and changes only with partial changes. In contrast, the city of Olomouc has the largest amount of the Residential Design Zone Areas in the central part, and this is seen as a result of the newer and pro-development zoning plan. Thanks to this, the city of Olomouc has experienced a considerable expansion of housing construction in recent years. The city of Jihlava, the smallest of the cities, has the smallest share of the Residential Design Zones in the peripheral part of the city, but in the central part of the city it can offer to investors a larger share of the Residential Design Zone Areas than the city of Brno.

So, what does the city of Brno win? In the vastness of its peripheral part. Due to the fact that it applies almost 6.5 million m2 of the Residential Design Zone in this part, its total IoRD has increased to 0.57. This is the highest of the surveyed cities. Looking at the number of areas without Limit Level 1, we find that in the peripheral part there are 2.92 million m2 of Residential Design Zone Areas of the city of Brno, which is the absolute majority of the surveyed areas. The results therefore show that the city of Jihlava has less development potential based on IoRD, despite the fact that 22% of Residential Design Zone Areas in the city of Jihlava is in Limit Level 1. The city of Olomouc has a large number of residual development areas due to its size, but a large number of them are limited by the level of Limit 3 and in Limit Level 1 it has the smallest share of surveyed design areas.

When comparing the presented results with the information resulting from the analysis of the current situation, it can be stated that the proposed methodology provides results that are different from other existing procedures focused on regional development, be it the City Prosperity Index (CPI) [20] focused on urban sustainability assessment and ranking of cities, the Sustainable Cities Index (SCI) [26] focused on complex assessment of environmental, social and business factors or the GCD-Index [24] focused on socio-economic–political–technologic performance. The proposed methodological procedure based on IoRD is focused on the practical assessment of potential development territories, especially with regard to territorial limits that may block potential territorial development in the municipalities under consideration. However, the proposed model can be applied while respecting principles based on the 15-min city model [32,33,34], which can help to optimize the structure of future urban site use considering socio-economic aspects that are of primary interest to the IoRD. Thus, the aim of 15-min city is in synergy with urban planning, because the zoning plan and its stated functional use for the residence also includes the possibility of building other functions, most often commercial, administrative and other, that complement the main function.

5. Conclusions

The IoRD is an index that can play a crucial role in the assessment of cities, in their planning, and in the creation of spatial and spatial planning plans. If urban planners were to use the IoRD as an indicator of the preparedness of a spatial plan for the future construction of residential buildings, spatial planning and urban development could become more efficient and there could be more opportunities for construction. Such an approach from the point of view of the city government could also provide a solution to the housing crisis and the addition of sufficient capacity. Cities that would help themselves with this index could also show potential investors how prepared their cities are for residential development. Here is a hint of the second possible use. If investors, namely residential developers, were to be able to decide on entry into a particular urban market, the proposed IoRD can make it very easy for investors to decide on the choice of their target cities.

However, the results show that in order to make the IoRD more efficient, it would be advisable to always create these indices separately for central, and especially for peripheral, areas of cities. This is mainly due to the different conditions that prevail in these two parts of cities. While in peripheral areas there is more greenfield type of construction, in central areas there is more of a gap in construction within brownfields. However, these carry a much greater number of limits and risks than greenfields. However, what is the correct IoRD value, or let us say, a “healthy value”? Looking at case studies, we can conclude that the correct value could be somewhere around the level of 0.60 and above, but this needs to be verified by other case studies and practice.

The research question addressed in the presented article was formulated as follows:

“How is it possible to take into account the territorial limits associated with residential development in intravilanes of cities for the purposes of further planning of urban development by cities and to support the decision-making of development organizations on the location of their project in a given location?”

Considering the results of the discussion and subsequent conclusions, it can be concluded that the Index of Residential Development can be designed and verified on case studies in an appropriate way and ways to achieve better results of urban planning and urban development, as well as discussions between the city and developers. The results of the study can be seen as a possibility to apply new approaches when planning the development of municipalities and regions and can contribute to clearer processes of spatial planning and subsequent development of the territory, both from the point of view of the municipality and from the point of view of potential investors who will actually implement the construction development of the locality. Considering territorial limits in the case of ensuring wider awareness of the presented IoRD and in the case of application of IoRD to more municipalities in the Czech Republic and abroad can contribute to a change in the market of development projects, as it will be easier for developers to identify the optimal spatial solution of their planned project and the related site selection. This change can also be an incentive for spatial planning authorities to optimize the spatial plan in terms of the possibilities of using the territory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V. and V.H.; methodology, P.V.; software, P.V.; validation, P.V. and V.H.; formal analysis, P.V.; investigation, P.V.; resources, P.V. and V.H.; data curation, P.V. and V.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V. and V.H.; writing—review and editing, V.H.; visualization, P.V. and V.H.; supervision, V.H.; project administration, V.H.; funding acquisition, V.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper has been worked out under the project of the Specific research at Brno University of Technology “FAST-S-23-8253 Cost analysis of building objects within the life cycle” and the project of the Specific research at Brno University of Technology “FAST-J-22-8063 Methodological process of revitalization of brownfield sites as public projects based on their impacts for society”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Urban, L. Sociologie: Klíčová Témata a Pojmy (Sociology: Key Topics and Concepts); Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty, M.R. Testing Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: National Quality-of-Life across Time. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 43, 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sujith, K.M.; Biju, C.A.; Subhash, C.V.; Dili, A.S. Need based approach: A perspective for sustainable housing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1114, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musil, J. The Czech Housing System in the Middle of Transition. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.; Sunega, P. The future of housing systems after the transition—The case of the Czech Republic. Communist Post Communist Stud. 2010, 43, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Stacherzak, A.; Král, M. The Problems of Managing Municipal Housing Resources in Poland and the Czech Republic. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 032029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabiska, R.; Hlavacek, M. Regional Determinants of Housing Prices in the Czech Republic. Czech J. Econ. Financ. 2022, 72, 2–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sunega, P.; Lux, M. Systemic risks on the Czech housing market. E+M Ekon. A Manag. 2013, 16, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Housing Affordability in Cities in the Czech Republic; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M.; Kubala, P.; Sunega, P. Why so moderate? Understanding millennials’ views on the urban housing affordability crisis in the post-socialist context of the Czech Republic. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2023, 38, 1601–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Lipský, Z.; Kukla, P. Mapping and typology of unused lands in the territory of the town Kutná Hora (Czech Republic). Acta Univ. Carol. 2017, 47, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gyenizse, P.; Bognár, Z.; Czigány, S.; Elekes, T. Landscape Shape Index as a Potential Indicator of Urban Development in Hungary. Acta Geogr. Debrecina Landsc. Environ. Ser. 2014, 8, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tannier, C.; Pumain, D. Paris Fractals in urban geography: A theoretical outline and an empirical example. Cybergeo 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Fractal Modeling and Fractal Dimension Description of Urban Morphology. Entropy 2020, 22, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I.; Tannier, C.; Frankhauser, P. Is there a link between fractal dimension and residential environment at a regional level? Cybergeo 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L. Informal urban development in Latin American urban peripheries. Spatial assessment in Bogotá, Lima and Santiago de Chile. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-55844-202-3. [Google Scholar]

- Conceição, P. Human Development Report 2021/22; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Checa-Olivas, M.; de la Hoz-Rosales, B.; Cano-Guervos, R. The Impact of Employment Quality and Housing Quality on Human Development in the European Union. Sustainability 2021, 13, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, C. Prediction and comparison of urban growth by land suitability index mapping using GIS and RS in South Korea. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 99, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Lee, C.-M.; Kim, Y. Developments of cellular automata model for the urban growth. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2002, 37, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Phillis, Y.A.; Kouikoglou, V.S.; Verdugo, C. Urban sustainability assessment and ranking of cities. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M.A.R.; Park, D. The Application of the Gross City Development Index (GCD-Index) in Tokyo, Japan. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 62, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsila, P.; Anguelovski, I.; García-Lamarca, M. Injustice in Urban Sustainability: Ten Core Drivers; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781000790405. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The New Leipzig Charter. 2021. Available online: https://futurium.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/202103/new_leipzig_charter_en.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Arcadis. The Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index 2022. 2022. Available online: https://wwww.arcadis.com (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Tosics, I. European urban development: Sustainability and the role of housing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2004, 19, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J. Impact of Spatial Planning on the Pre-Investment Phase of the Development Process in the Residential Construction Field. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2017, 63, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Council Recommendation. Brussels, Belgium. Council Recommendation on the 2023 National Reform Programme of Czechia and Delivering a Council Opinion. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023H0901(03) (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Zhu, J.; Pawson, H.; Han, H.; Li, B. How can spatial planning influence housing market dynamics in a pro-growth planning regime? A case study of Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumannová, M. Smart Districts: New Phenomenon in Sustainable Urban Development. Case Study of Spitalka in Brno, Czech Republic. Folia Geogr. 2022, 64, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Mocák, P.; Matlovičová, K.; Matlovič, R.; Pénzes, J.; Pachura, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Kostilníková, K.; Demková, M. 15-Minute City Concept as a Sustainable Urban Development Alternative: A Brief Outline of Conceptual Frameworks and Slovak Cities as a Case. Folia Geogr. 2022, 64, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Steuteville, R. Defining the 15-Minute City. Public Sq. CNU J. 2021. Available online: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2021/02/08/defining-15-minute-city (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. The ‘15-Minute City’ concept can shape a net-zero urban future. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedűs, L.D.; Túri, Z.; Apáti, N.; Pénzes, J. Analysis of the Intra-Urban Suburbanization with GIS Methods. The Case of Debrecen Since the 1980s. Folia Geogr. 2023, 65, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Czech Republic. Zákon č. 197/1998 Sb., o Územním Plánování a Stavebním Řádu (Act No. 197/1998 Coll., on Town Planning and Building Regulations); Government of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 1998.

- Poznáváme Svět (Knowing the World). Available online: https://www.poznavamesvet.cz/images/obsah/Brno/velky/Brno_katastr%C3%A1ln%C3%AD%20%C3%BAzem%C3%AD.jpg (accessed on 19 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).