Abstract

This paper critically reviews the body of literature on affordances relating to the design and inhabitation of school buildings. Focusing on the influence of learning spaces on pedagogical practices, we argue that links between affordances, architecture and the action possibilities of school-based environments have largely been overlooked and that such links hold great promise for better aligning space and pedagogy—especially amidst changing expectations of what effective teaching and learning ‘looks like’. Emerging innovative learning environments (ILEs) are designed to enable a wider pedagogical repertoire than traditional classrooms. In order to transcend stereotypical understandings about how the physical environment in schools may afford teaching and learning activities, it is becoming increasingly recognised that both design and practice reconceptualisation is required for affordances of new learning environments to be effectively actualised in support of contemporary education. With a focus on the environmental perceptions of architects, educators and learners, we believe affordance theory offers a useful framework for thinking about the design and use of learning spaces. We argue that Gibson’s affordance theory should be more commonly applied to help situate conversations between designers and users about how physical learning environments are conceived, perceived and actioned for effective teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, school buildings have been designed largely to support teacher-centred instruction. However, in Australia, New Zealand and parts of northern Europe, many new learning spaces are being designed to enable a wider range of pedagogies. These may be identified as innovative learning environments (ILEs) [1].

With an emphasis on the affordances of ILEs, Cleveland [2] (p. 93) characterised these environments as “learning spaces that provide a greater degree of spatial variation, geographic freedom and access to resources for students and teachers than traditional classrooms”. Subsequently, Imms, Mahat, Byers and Murphy [3] identified ILEs as the product of innovative space designs and innovative teaching and learning practices, highlighting the importance of relations between space and behaviour. This and related discourse [4,5] reveals parallels with Gibson’s [6] affordance theory—which describes the complementarity of the environment and user in perceiving a range of action possibilities—and indicates developing recognition in the literature that learning spaces and pedagogies are intrinsically linked.

Analysing the relationships between architectural spaces and pedagogical practices is salient at a time when educational objectives are being reviewed in schools around the world amidst shifting economic, political, cultural and social agendas. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has promoted innovative learning environments [1] and innovative learning systems [7] as key components of reforms needed to support learners to thrive in the 21st century. Concurrently, educators of global influence have promoted the need for change, particularly with respect to pedagogies aimed at supporting 21st century skills development. Fullan and Langworthy [8] and Fullan, Quinn and McEachen [9] advocated for ‘deep learning’ climates that may help generate new relationships with and between learners, their families, communities and teachers and that deepen human desire to connect with others to do good—contributing to the development of the skills needed to thrive in a modern world.

Monahan’s [10] ‘built pedagogy’ construct has also aided recent interpretations of space–pedagogy relationships. He suggested that, throughout history, the creation of school spaces has been closely aligned with educational philosophies. He commented that:

“Architects, educational philosophers and teachers know well the force that spatial configurations exert on people—how they shape what actions are possible, practical, or even conceivable. Because space constrains certain actions and affords others, the design and layout of space teaches us about our proper roles and places in society”([10], p. 8).

The concept of ‘affordances’ was coined by James Gibson in the 1970s. Since then, his theory that the environment may offer ‘the animal’ a range of ‘action possibilities’ has been applied and re/interpreted by researchers from varying fields. Commonly, these have included psychology [6,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], technology/Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) design [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] and anthropology [32].

However, prior to Gibson’s development of the term and theory of ‘affordances’, the principles behind the theory can be recognised in the approaches of school architects: principally Herman Hertzberger [33,34], who promoted school typologies that varied from traditional classroom designs to enable more diverse pedagogical practices. In 1969, Hertzberger [33] specifically discussed relationships between ‘users’ and ‘things’ when describing his approach to the architectural design of the innovative Montessori Primary School in Delft. He wrote:

“The aim of the architecture is then to reach the situation where everyone’s identity is optimal, and because user and thing affirm each other, make each other more themselves, the problem is to find the right conditioning for each thing. It is a question of the right articulation, that things and people offer each other. Form makes itself, and that is less a question of invention than of listening well to what person and thing want to be”([33], p. 64).

The discourse generated by Hertzberger [33] about the relationships between the environment and users reveals synergies with Gibson’s later descriptions of affordances, including his most cited definition found in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception [6]:

“The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill.The verb to afford is found in the dictionary, but the noun affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by it something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment”([6], p. 127).

This paper critically reviews the body of literature on affordances as it relates to the design and pedagogical inhabitation of school buildings. In doing so, links between education, architectural design and affordance theory are explored within the context of shifting perspectives on what constitutes effective teaching and learning practices in schools.

By critiquing applications of affordance theory conducted by researchers from varying disciplines, contested ideas surrounding the theory are highlighted, including varying and sometimes contradictory interpretations of Gibson’s original concept [27,29,35]. Opportunities for applying Gibson’s theory to develop new insights into the relationships between space and pedagogy are also discussed, offering a foundation for future research into the action possibilities of learning spaces for school teachers and students.

To provide context, we begin by discussing recent developments in the creation of ILEs. We then explore affordance theory discourse, as interpreted through the lens’ of architecture and learning environment design. Finally, we conclude with suggestions for future research at the intersections of space, pedagogy and affordance theory.

2. Innovative Learning Environments (ILEs)

Formal schooling, as we know it, was established in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, based on a subject-focused curriculum delivered didactically in traditional classrooms [36]. Since then, school buildings have largely been designed to reflect and enable teacher-centred instruction. However, many newer learning spaces, as may be identified as ILEs, are being designed to enable a wider range of pedagogies [37].

Intended to enable a shift from teacher-centred instruction to student-centred learning [1,38,39], the pedagogies within these new socio-spatial environments are anticipated to feature collaborative, participatory, and agentic teaching and learning approaches that may help engage students as “active participants in their own learning” [40] (p. 74) and “encourage and enable students to learn in ways that allow them to attain their personal academic and social potential” [41] (p. 65).

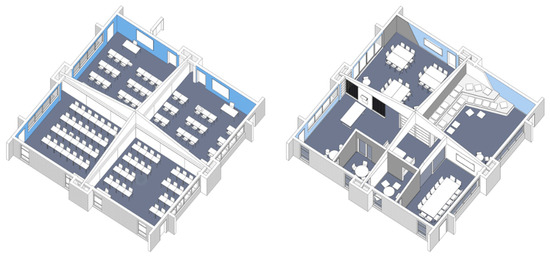

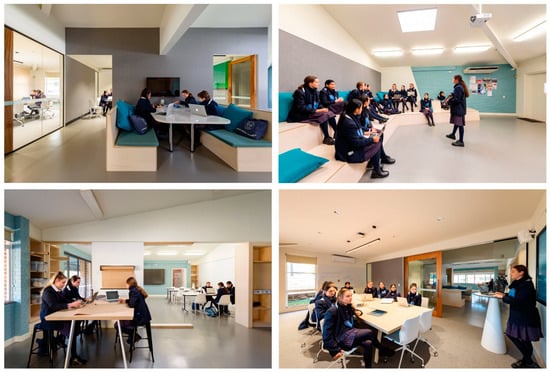

Physically, ILEs often exhibit an array of different spaces, learning materials and ways for people to interact with each other [40]. To illustrate the distinction between traditional classrooms and ILEs, an example is shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 (below). These depict a small secondary school building that was re-developed into an ILE at a school in Sydney, Australia. The re-development transformed a 1980s classroom block into an ILE featuring a variety of interconnected learning spaces or settings, each expected to afford different modes of teaching and learning.

Figure 1.

Before and after floor plans of a re-developed learning space, a school in Sydney, Australia (Image courtesy of Hayball architects) [42].

Figure 2.

Writeable walls and table-tops enable students to brainstorm and share thinking with each-other (Image courtesy of Hayball architects).

Figure 3.

A range of settings to accommodate different teaching and learning modes, and activities (Images courtesy of Hayball architects).

This new environment at the school can accommodate up the 75 students (equivalent to three classes, as opposed to the original four) and provides opportunities for the collaborative teaching of multiple classes. The building features zones for large group gatherings and explicit teaching as well as smaller areas for small group and independent work. Spaces include writeable surfaces (walls and table-tops) that enable students to work in groups and to share their thinking (see Figure 2). A range of setting types, including tiered seating areas, settings defined by high tables, booth seating areas and a boardroom-style space, provide students with options to pursue varied learning activities (see Figure 3).

As shown in this example, ILEs tend to be rich with affordances for learning. However, research suggests that these may not be well understood generally by designers or teachers [43,44]. Therefore, whilst there is widespread understanding about how traditional classrooms ‘work’, it appears that there is not common understandings about the pedagogical possibilities of ILEs [43].

Insights into the relationships between the environment and user may be considered central to how learning environments are perceived and productively used (inhabited). When writing about Gibson’s ideas about perception in Anthropology and/as education, Ingold [45] (p. 31) stated that “the perceptual system of the skilled practitioner resonates with the properties of the environment”. He suggested that an ‘education of attention’ may be undertaken as educators notice and “respond fluently to environmental variations and to the parametric invariants that underwrite them” (p. 31). As such, understandings about affordances and how they relate to school design and educational practice is needed in support of effective teaching and learning. Adopting an affordance-based approach to design is likely to help generate shared understandings between architects and users, aiding in the creation of spaces that are not only well-designed but also well-used in practice. The following critical review of the literature seeks to highlight the usefulness of affordance theory in understanding space–pedagogy relations.

3. Affordance Theory as Interpreted through the Lens’ of Architecture and Learning Environment Design

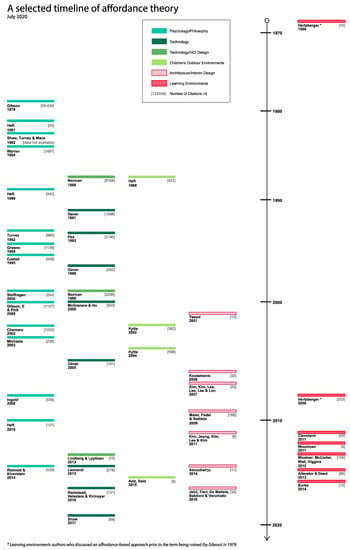

Whilst affordances have often been discussed in fields such as psychology, environmental psychology and technology (e.g., Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) design), affordance theory has been less present in architectural discourse. Figure 4 (below) depicts a selected timeline of affordance theory discourse and development. It represents parallel discourses with respect to the application and development of ‘affordance thinking’ and highlights the varied trajectories of the theory within selected domains over past decades.

Authors from psychology/philosophy, technology/HCI design, children’s outdoor environments, engineering/product design, architectural/interior design and learning environments contexts are represented. As can be deducted from the number of citations, it is clear that the discourse in psychology/philosophy and technology/HCI design is far more extensive than in other domains.

3.1. Affordance Theory in Architectural Discourse

Mention of affordance theory in architectural discourse is sparse yet not completely absent. With respect to the design of physical environments, Heft [46] suggested that there is a strong argument for a more affordance-based approach to design yet a lack of literature exists about the experience of users within spaces. He wrote:

“Designers interested in how particular environments are utilized and experienced quite reasonably might turn to the environmental psychology research literature for guidance. They are likely to be disappointed. Although there is an extensive literature addressing how individuals assess environments (or rather environmental surrogates) on rating scales, information is sorely lacking about how environments are experienced by users in the course of action”([46], p. 22).

Over recent decades, affordances have been discussed and explored within the fields of technology/HCI design [26,28,47], architecture [48,49,50,51,52], interior design [53,54] and product design [55]. However, as noted by Heft [46], affordance theory has been less present in architectural discourse than in many other design fields. This is perhaps surprising given that Gibson [6] challenged architects and designers to adopt a theory of affordances to encompass their understanding of materials into a system. Heft [56] also noted this as being curious, given that the architectural design process is based around understandings of how building elements provide function for users. Furthermore, Maier et al. [51] argued that the lack of references to affordances within architecture relates to historical separations of form and function dating back to the writings of Vitruvius, in which form (firmitas), function (utilitas) and beauty (venustas) were considered separate but competing requirements. They proposed that affordance theory could be deployed to unite the originally separate Vitruvian ideas of form and function.

Similarly, Koutamanis [50] and Sporrel, Caljouw and Withagen [57] discussed designers’ competing considerations with respect to form and function. Koutamanis [50] suggested that there is a perception that architects intuitively address affordances as part of their training and practice but noted that this is not necessarily the case as they primarily perceive design through a visual and aesthetic lens, generating differences between designer’s and user’s perspectives and perceptions. He felt that “users can be flexible, adaptable and tolerant to design limitations despite constant irritation and frustration” [50] (p. 357). This, he suggested, allows architects to be selective in what they deem important and “insensitive to practical problems that conflict with higher, usually aesthetic norms” (p. 357). Sporrel et al. [57] (p. 136), too, noted that “designers are often driven by aesthetic motives”. In discussing playground design, they concluded that designers’ motives may not always align with children’s perspectives on the playability of play equipment.

Figure 4.

A selected timeline of affordance theory application and development [58].

Koutamanis [50] argued that the adoption of an affordance perspective could help correlate designers’ and users’ perceptions, promoting opportunities for design innovation and reducing “the danger of falling back to stereotypical solutions and arrangements” [50] (p. 357). He concluded that “the main target of affordances in architectural design is the enrichment of the architects’ perception” [50] (p. 361).

Heft [59] suggested that, if design professionals better understood the nature of affordances, including the relationship between latent affordances and the actual use of environments, they may pay more attention to the ways in which environmental cues can be designed into settings to enable use. He also noted that, whilst designers do consider function as part of their work, the descriptive language they often use is largely form-oriented. He went on to suggest that this may hinder their ability to adequately incorporate function into their designs [60].

3.2. Applications of Affordances in Architecture

A small number of researchers within the architecture and interior design disciplines have suggested various ways that affordances could be understood in relation to buildings [48,51,52,53,54]. It must be said, however, that a number of these suggestions have strayed (possibly too far) from the origins of affordance theory, with its emphasis on psychological perception.

Beek and de Wit [61] classified affordances within three dimensions of architecture: organismic personal, socioeconomic and cultural aesthetic. The organismic-personal level refers to Gibson’s foundational understanding of affordances, i.e., the relationship between the environment and the user. However, the socioeconomic level refers to the interaction between humans in the realisation of common goals and the cultural-aesthetic level refers to the culturally situated aesthetic dimensions of architecture. Beek and de Wit felt that architects needed to design and connect affordances across all three levels and suggested that “architectural flaws are often the result of an emphasis on one level to the neglect of the other levels” [61] (p. 34).

Some years later, Maier et al. [51] defined both direct and indirect affordances within architecture. They suggested that artefact-user affordances (AUA) are direct affordances that reflect Gibson’s original ideas about relations between the environment and the user. However, stretching Gibson’s theory beyond what might be justified, they also proposed artefact–artefact affordances (AAA). These, they suggested, were indirect affordances related to the components required for buildings to function, e.g., walls afford support to roofs. The later (AAA) appears to be more akin to what Stoffregen [19] (p.15) identified as ‘events’, i.e., “static and dynamic properties of objects and surfaces defined without reference to behaviour”. Maier, Ezhilan and Fadel [62] also applied these definitions as part of the development of an Affordance Structure Matrix (ASM), which they proposed to enable the analysis of environments based on the AUA and AAA concepts.

Similarly, Galvao and Sato [55] developed a Function–Task Interaction Method to analyse affordances in product design. Kim et al. [53] subsequently adapted this to suit interior design contexts. They proposed three key aspects to consider:

- Space—including building components such as floors; ceilings; columns; walls; and door and window openings, which enable the flow of movement between spaces;

- Objects—including fixtures, fittings and furniture as well as technological equipment and personal belongings, such as pens and paper; and

- Social activities and tasks—including a range of diverse interactions between people (human–human interactions), including communication, socialising, discussion and presentations.

The affordance analysis framework developed by Kim et al. [53] represents perhaps the most sympathetic interpretation of Gibson’s theory with respect to a built environment. Nevertheless, the range of interpretations of affordances across multiple disciplines, including within architecture, remains a source of confusion, with some researchers even questioning the validity of the concept [29].

3.3. Affordance Theory in Learning Environment Design

Within the world of architecture, affordance theory has received perhaps more attention in educational facility design [63,64,65,66,67] than in any other built environment sector. However, its application in ‘learning environment research’ has not been immune to the uncertainty identified above, and there remains limited discourse about its suitable interpretation and application.

Of the academic papers that refer to affordances in the context of learning environments, Alterator and Deed [67] referenced Greeno [14] (p. 2) to define affordances as “aspects of an environment that enable, contribute to, or constrain the kinds of interactions that subsequently occur”. Taking their cue from the affordance analysis framework by Kim et al. [54], Young et al. [43] (p. 697) subsequently offered a definition that identified ‘learning environment affordances’ as “qualities of the environment (space, objects and people) which may be perceived to enable teaching and learning activities and behaviours”.

To aid the interpretation and application of affordance theory in learning environment research and school design, we summarise some key affordance theory concepts, or ideas, below. Our intention here is to offer accessibility and clarity to some of the key concepts, as discussed in the literature, for researchers and practitioners in the domains of architecture and education.

4. Affordance Theory—A Review of Some Key Concepts

4.1. Relationships, Perception and Action Possibilities

Foundational to the concept of affordances is the relationship between the environment and the user, and the action possibilities that may result. People’s perceptions are also fundamental to affordances. Gibson [6] suggested that an affordance needs to be perceived for an action possibility to occur yet affordances may exist regardless of whether they are used or not. He wrote:

“The affordance of something does not change as the need of the observer changes. The observer may or may not perceive or attend to the affordance, according to his needs, but the affordance, being invariant, is always there to be perceived. An affordance is not bestowed upon an object by a need of an observer and his act of perceiving it. The object offers what it does because it is the object it is”([6], p. 138).

However, the role of perception has been debated in the affordance literature. For example, Norman [28] proposed a definition of affordances from an HCI design perspective, which included both perceived and actual (or real) properties. He argued:

“... the term affordance refers to the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used … Affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things. Plates are for pushing. Knobs are for turning. Slots are for inserting things into. Balls are for throwing or bouncing. When affordances are taken advantage of, the user knows what to do just by looking: no picture, label, or instruction needed”([28], p. 9).

Norman’s interpretation of affordances diverges from the tenet of direct perception that was central to Gibson’s view. This has been the cause of some confusion, as it implies that (a) an affordance needs to be perceived in order for it to exist and (b) that an affordance might be perceived but not be real. Recognising the ambiguity of his early definition, Norman [47] revised his definition to refer to ‘perceived affordances’, noting that HCI designers care “more about what actions the user perceives to be possible than what is true” [47] (p. 39). Furthermore, Noman [28,47] and others have suggested that assisting users to perceive the affordances of computer interfaces is core to how designers should approach HCI design.

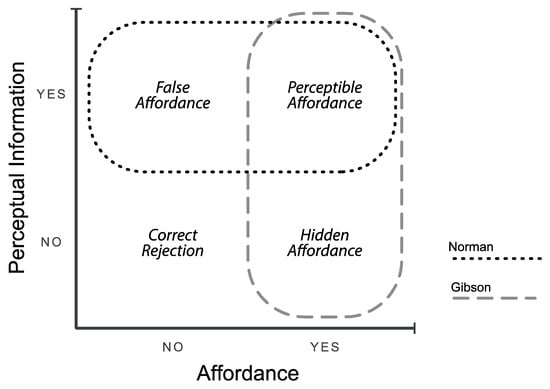

An affordances matrix developed by Gaver [23] provides some insight into how these differing affordance perspectives may be understood (see Figure 5). Relating affordances and perceptual information, it defines four categories of affordances (perceptible, hidden, false or correct rejection) and identifies whether an actual (real) affordance and/or perceptual information exists. Aligning with Gibson’s [6] definition, Gaver noted that affordances “exist whether the perceiver cares about them or not, whether they (are) perceived or not, and even whether there is perceptual information for them or not” [23] (p. 2). Norman’s definition of ‘perceived affordances’ invariably includes what Gaver [23] identified as ‘false affordances’, i.e., perceived information that, in reality, does not afford an action possibility.

Figure 5.

Gibson’s and Norman’s affordance perspectives, adapted from Gaver’s [23] affordance matrix [42].

4.2. Abilities and Intentions towards Affordances

Individuals’ abilities to perceive and subsequently use affordances is thought to relate to both their physical and mental capabilities. Warren’s [22] empirical study on the affordances of stair climbing showed that an individual’s ability to recognise affordances is body-scaled. He demonstrated that the ability to utilise affordances of stair climbing were related to the ratio between riser height and peoples’ leg length. Translating these findings into the context of schools, it would appear obvious that designers should consider the differences in scale of smaller children, as opposed to older children or adults, when designing new learning spaces.

People’s abilities may also be influenced by a range of external factors. Some prominent theorists (including Gaver [23] and Norman [47]) have suggested that observers’ cultures, social settings and experiences influence their ability and intentions towards using affordances. To this end, Kyttä [68,69] added the notion that affordances may be ‘shaped’ by a range of environmental, cultural and policy influences, helping to determine whether affordances may become available and relevant to users.

When describing objects that offer multiple affordances, Heft [56] noted that affordances do not cause behaviours. He suggested that there is a need for intentionality on the part of the perceiver to take up action possibilities by enabling them. For example, a lit candle may offer multiple affordances, including illuminating a dark space or heating a liquid. As the context in which a user and their environment co-exists may influence what a user requires (e.g., light or heat), the intentionality around which affordance is actualised may guide precedence.

Here, we begin to recognise the interconnectedness of space and practice. On one level, affordances are dependent on physical ability and body-scale. On another level, peoples’ abilities to actualise affordances are determined by their mental ability, shaped by cultures, social settings and experiences. This was recognised in the context of learning environments by Halpin [70], who noted that open-plan school designs are just as likely to “act as containers for conventional as much as for more enlightened modes of teaching and learning” (p. 251) and that the key variable for the success of such environments “is not space, but teachers’ intentions and educational aims in terms of how they go about using it” (p. 251).

4.3. Learning to Perceive Affordances and Sociocultural Contexts

Researchers in the field of children’s environments [56,60,68,69,71] differentiate between potential affordances, which may remain latent in the environment and not seen by individual users, and actualised affordances. The notion of actualisation was introduced by Heft [56], who suggested that, of all potential affordances, only some are perceived and utilised at any given time depending on individual’s intentions. He clarified that, in order for affordances to be utilised, they must first be perceived.

Eleanor Gibson (who was married to James Gibson and also a prominent psychologist) and Pick suggested that perceptual learning can help individuals discover affordances in some instances, but “may require much exploration, patience, and time” [13] (p. 17). Other researchers have also described peoples’ perceptions and understandings of affordances as being culturally specific, such as when learning how to use particular objects takes place through direct instruction or observing others [56], or when learning to actualise affordances through playful discovery [30].

Further to the discourse on learning to perceive affordances, a number of researchers have discussed the influence of socio-cultural contexts on individual’s understandings of affordances [12,17,23,25,28,47,72]. Costall [12] (p. 472) posited that we “experience objects in relation to the community within which they have meaning” and later noted that understanding affordances would “not be achieved by fixation upon the object in isolation, nor the individual-object dyad” [73] (p. 92). He suggested that objects need “to be understood within a network of relations not only among different people, but also a ’constellation’ of other objects drawn into a shared practice” [73] (p. 92). Similarly, Rietveld and Kiverstein [17] (p. 340) suggested that affordance perception may be considered relative to an individual’s abilities “acquired through training and experience in sociocultural practices”. Drawing from Wittgenstein [74] (1953), Rietveld and Kiverstein [17] introduced the concept of affordances being part of socio-cultural ‘forms of life’ and suggested the following:

“We believe it is more precise to understand abilities in the context of a form of life. In the human case, this form of life is sociocultural, hence the abilities that are acquired by participating in skilled practices are abilities to act adequately according to the norms of the practice”([17], p. 330).

Further advancing a holistic conceptualisation, Ingold [21] (p. 1805) described affordances in the context of “an ecology of threads and traces”. He suggested that Gibson’s perspective should be described as “not a network but a meshwork” (p. 1807) and positied that affordances should be considered within an ‘entanglement’ of factors.

Promoting similar ideas, Lindberg and Lyytinen [26] introduced the concept of ‘affordance ecologies’, suggesting that affordances may be comprised of three domains: infrastructure, organisation and practice. Here, the ecology metaphor invokes thinking about complexity and dynamicity [35]. Working from a technology design perspective, Lindberg and Lyytinen [26] suggested that the infrastructure domain refers to basic information technologies and associated organisational structures that provide a field of tools available for use; that the organisational domain comprises institutional arrangements that guide how technologies are understood and used; and that the practice domain refers to the practices associated with how technologies are actualised.

Additionally, in this context, Ramstead et al. [72] defined ‘cultural affordances’ as comprising ‘natural affordances’ and ‘conventional affordances’, where ‘natural affordances’ refer to direct relationships between the environment and the user, and ‘conventional affordances’ relate to possibilities for action influenced by expectations, norms, conventions and cooperative social practices. While the distinctions put forward by Ramstead et al. [72] may not align neatly with the more holistic conceptions of authors such as Ingold [32], and Lindberg and Lyytinen [26], they do highlight a trend in the literature acknowledging the influence of socio-cultural contexts on affordance perception.

5. Future Directions for Affordance Theory in Learning Environment Research and Practice

This review of the literature shows that affordance theory has been used by researchers from a range of fields with varying interpretations. Its application in learning environment research has not been immune to uncertainty. Although Gibson’s theory has received increased attention during the past decade, there remains little discourse in learning environment research around its suitable application. Here, we suggest opportunities to better appreciate and extend affordance theory to advance the design and use (inhabitation) of learning spaces and to better align space and pedagogy. We posit that affordance theory offers a useful framework for improving the action possibilities of learning spaces, and subsequent actualisation of affordances by teachers and students, especially when the environmental perceptions of designers, educators and learners are all considered.

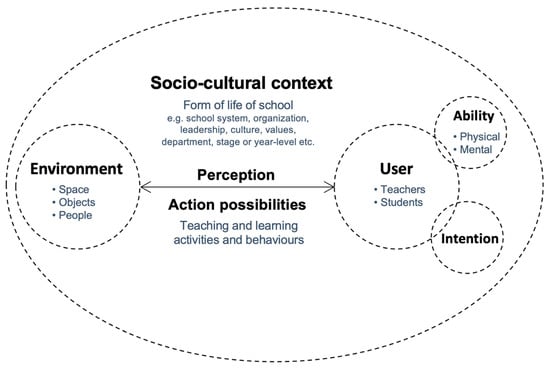

The key affordance theory concepts outlined above, i.e., environment-user relationships, perceptions, action possibilities, actualisation, abilities and intentions, learning and socio-cultural contexts, may all be translated into the learning environment context. Figure 6 (below) represents our interpretation of the relationships between these key concepts, as may be applied in the context of learning environments.

Figure 6.

Learning environment affordance framework [42].

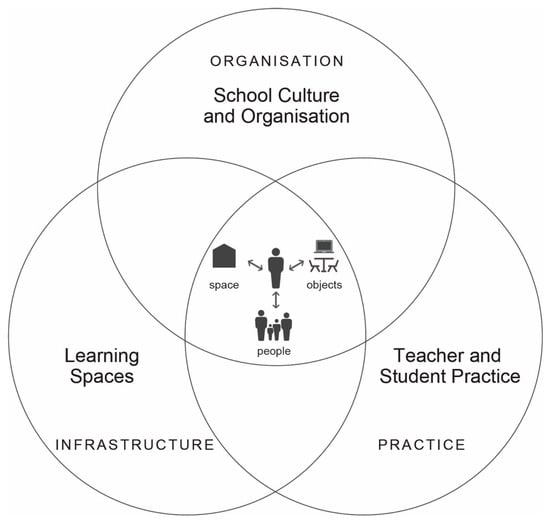

The idea of affordance ecologies [26] raises particularly interesting ways of thinking about affordances in the school context. Figure 7 (below) highlights the three interrelated domains of organisation (e.g., school organisation and culture), infrastructure (e.g., school environment–space relationship, objects and people), and practice (e.g., teacher and student practice) that Lindberg and Lyytinen [26] proposed as a framework to consider affordances within contextualised settings, again as may be applied in the context of learning environments.

Figure 7.

Learning environment affordance ecology, adapted from Lindberg and Lyytinen [25,42].

Predominantly, the discourse about affordances in learning environment research and practice has explored the relationships between the infrastructure and practice domains, focusing on direct relationships between the school environment, and teacher and student practice. Expanding this focus to attend to the organisation domain may reveal important insights into the cultural-situatedness of affordances, as influenced by the ways schools are organised and culturally led. For example, a school’s organisation and culture may contribute to its ‘form-of-life’ [17], influencing teachers’ and students’ abilities to actualise affordances within school spaces. As such, individuals’ abilities to actualise affordances may be influenced by the collective understandings about the potential and protocols of the spaces occupied. Re-visiting Gaver’s [23] categories of affordance (see Figure 5 above), an example of how the socio-cultural context of a school may influence perceptible and hidden affordances in a learning space could be understood as outlined in Table 1 (below).

Table 1.

Perceptible and hidden affordances in a learning space as influenced by socio-cultural context—the example of a pinnable wall surface.

The example in Table 1 (above) highlights the important role of perception within an affordance landscape, where multiple potential affordances may remain latent depending on the ‘form-of-life’ that governs teacher and student practice within an environment.

In the context of ILEs, in which the environment may offer greater spatial variation, geographic freedom, and access to resources for students and teachers than is common in traditional classrooms [2] (p. 93), understandings about how space can support teaching and learning requires teachers and students to ‘learn’ to perceive new affordances [13,30,56]. Designers, too, must develop deeper insights into what action possibilities should be afforded in schools during the process of their creation. Affordance theory should ‘participate’ in this discourse.

Realising the potential for space to support teaching and learning activities beyond the affordances of traditional classrooms appears certain to require an evolution of individual and collective understandings about how space can enhance pedagogic practice. The benefits of an affordance lexicon that encourages users’ perceptions to shift and evolve in order to pick-up more ‘effective’ affordances [23,26] suggests that the language used to describe and share affordances plays an important role in developing socio-cultural contexts that are supportive of the conception, perception and actualisation of affordances for teaching and learning.

With a word of warning, Norman [47] also described conventions as potential constraints on the affordances developed within communities of practice, noting that many conventions take time to be adopted and are slow to evolve. Further study of teacher and student practices in relation to affordances appears to be needed to ‘shed light’ on the influence of Lindberg and Lyytinen’s [26] organisational domain and how this may be leveraged to enable school inhabitants to take fuller advantage of their environments—particularly in ILEs.

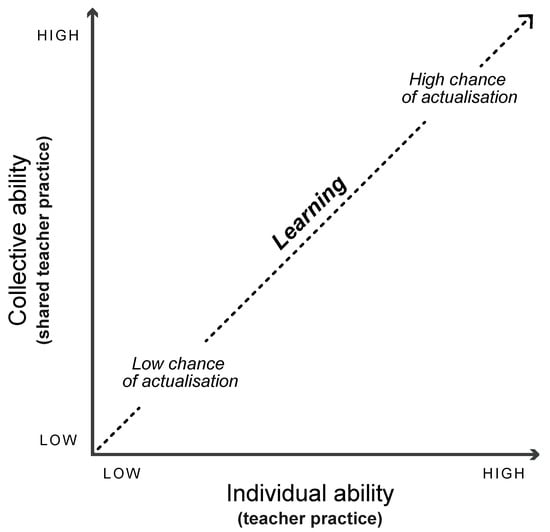

The design of ILEs is fundamentally based on the premise that broader pedagogical opportunities can be offered through the integration of more varied features within the environment. However, fulfilling the design intentions/aspirations of new learning spaces is clearly dependent on the ability of teachers (as leaders of learning activities) to perceive, utilise and shape the affordances of the environments they occupy—and to support students to act similarly. Learning through professional development may enhance teachers’ ‘individual ability’ to take advantage of the affordances around them (although further studies are required to show this), while strategies and resources that can support group understandings also appear needed to enhance the ‘collective ability’ of teachers to actualise the affordances of new environments.

Figure 8 (below) suggests a hypothesised relationship between ‘individual ability’ and ‘collective ability’, suggesting that learning in both realms will aid higher chances of actualisation of learning environment affordances by teachers.

Figure 8.

Affordance actualisation relative to individual and collective teacher practice [42].

We posit that paying attention to two key ‘moments’ in the creation of new learning environments may assist in the process of developing a shared affordance language, or lexicon:

- The architectural design process; and

- Initial inhabitation of new learning spaces.

First, the language chosen to discuss the design of new school facilities is likely to significantly influence the language that will persist as these facilities become inhabited by users. Labels applied to architectural drawings and the terminology used during design presentations may have a powerful influence on what affordances are perceived. The literature suggests that not paying attention to such matters can have unintended consequences. Heft [59] (p. 240) commented that “it must be disconcerting for professionals working on a design problem to learn (much less to believe) that the environments they are constructing are not perceived veridically by their clients”. Similarly, Koutamanis [50] promoted the use of a functional rather than form-based language in the practice of architectural design, suggesting that using an affordance-based language can maximise the likelihood that the intent of the design carries through to how inhabitants use the environment.

Second, embedding a shared language early in the ‘life’ of a new learning environment may assist in consolidating understandings of the action possibilities associated with the form and features of spaces. We posit that this can help embed a common language and understandings about how school spaces may be re/configured and actualised for teaching and learning activities.

We suggest that further research into the relationships between the descriptive language used and peoples’ perceptions of affordances should focus on these two key ‘moments’ in the creation of new school facilities. Situating such studies within the socio-cultural contexts of schools, as framed by Lindberg and Lyytinen’s [26] affordance ecologies model, may assist in the development of new affordance thinking in connection to schools and the action possibilities they offer.

6. Conclusions

This paper highlighted the relevance and value of affordance theory in relation to school-based learning environments. The review of the literature identified a number of key affordance theory concepts, helping to bring clarity to Gibson’s theory and subsequent re/interpretations. Suggestions for future research were also offered, towards developing new insights into the affordances of school-based learning environments, including generating understandings about how architects, educators and students perceive them and how the relationships between the environment and action possibilities can enhance both the design of new learning environments as well as the practices of the teachers and students inhabiting them.

In summary, we argue that the value of an affordance-based approach to learning environment design and use is beneficial for the following reasons:

- From a designers’ perspective, using an affordance-based lexicon may better align the perspectives of architects and users, promoting a greater likelihood that new learning spaces are designed to reflect and support teachers’ and students’ needs. Further to this, a shift in the use of affordance-based insights may enable more rigorous and in-depth briefing processes, helping to align the visions and expectations of educators and designers around evidence-based design features that offer the types of affordances that are genuinely useful to teachers and students in their daily practices. Further research should investigate how designers’ and educators’ perceive learning environment affordances and the language they use to articulate and communicate the design of schools.

- For school leaders, teachers and students, newly built learning environments may be considered successful when pedagogical practices align with a school’s educational aspirations and vision. For this to occur in the context of ILE’s, teachers as individuals and as members of collective groups, need to better perceive and utilise the affordances of the environments available to them. Further investigations should explore how teacher professional learning can be used to enhance educators’ spatial literacy, and their ability to individually and collectively use the action possibilities of new learning environments (i.e., spaces, objects and people) to support effective teaching and learning practices.

- Enabling a shift to new teaching and learning practices within new spaces is likely to benefit from consideration of the three interrelated domains of organisation, infrastructure and practice [26]. Facilitating ongoing and sustained actualisation of learning environment affordances, particularly in ILEs, appears to certainly require more aligned understandings between designers (architects and interior designers), users (teachers and students) and those who influence the organisation of schools (school leaders). Further research should address how best to facilitate and strengthen these interrelated and cross-disciplinary understandings.

Therefore, as Hertzberger [33] suggested, “the aim of the architecture is … to reach the situation where everyone’s identity is optimal” (p. 64). For this to occur, it appears that a return to relational thinking about the design and inhabitation of learning spaces is needed to accommodate the types of pedagogies that are believed to support learners to thrive in the 21st century. To this end, Gibson’s affordance theory and subsequent developments offers great promise for better aligning space and pedagogy—especially amidst changing expectations of what effective teaching and learning ‘looks like’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y. and B.C.; Supervision, B.C.; Visualization, F.Y.; Writing—original draft, F.Y.; Writing—review & editing, F.Y. and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Australian Research Council, grant number LP150100022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Innovative Learning Environments and Teachers Change (ILETC) ARC Linkage project and the Learning Environments Applied Research Network (LEaRN) at the University of Melbourne. We thank Wesley Imms for his leadership of this project. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Ricky Gagliardi and Hayball Architects.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- OECD. Innovative Learning Environments; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, B. Emerging methods for the evaluation of physical learning environments. In Evaluating Learning Environments: Snapshots of Emerging Issues, Methods and Knowledge; Imms, W., Cleveland, B., Fisher, K., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 8, pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Imms, W.; Mahat, M.; Byers, T.; Murphy, D. Type and Use of Innovative Learning Environments in Australasian Schools ILETC Survey No. 1; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2017; Available online: http://www.iletc.com.au/publications/reports/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Mulcahy, D.; Cleveland, B.; Aberton, H. Learning spaces and pedagogic change: Envisioned, enacted and experienced. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2015, 23, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltmarsh, S.; Chapman, A.; Campbell, M.; Drew, C. Putting ‘structure within the space’: Spatially un/responsive pedagogic practices in open-plan learning environments. Educ. Rev. 2015, 67, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton-Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M.; Langworthy, M. Towards a New End: New Pedagogies for Deep Learning; Pear Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M.; Quinn, J.; McEachen, J. Deep Learning: Engage the World, Change the World; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, T. Globalization, Technological Change, and Public Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chemero, A. An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 2003, 15, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costall, A. Socializing affordances. Theory Psychol. 1995, 5, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.J.; Pick, A. An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Greeno, J.G. Gibson’s affordances. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 2, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michaels, C.F. Affordances: Four points of debate. Ecol. Psychol. 2003, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E. Encountering the World: Toward an Ecological Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, E.; Kiverstein, J. A rich landscape of affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 2014, 26, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Turvey, M.; Mace, W. Ecological psychology: The consequence of a commitment to realism. In Cognition and the Symbolic Proceses II; Weimer, W., Palermo, D., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 159–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffregen, T.A. Affordances and events. Ecol. Psychol. 2000, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffregen, T.A. Affordances and events: Theory and research. Ecol. Psychol. 2000, 12, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turvey, M.T. Affordances and prospective control: An outline of the ontology. Ecol. Psychol. 1992, 4, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, W.H., Jr. Perceiving affordances: Visual guidance of stair climbing. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1984, 10, 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaver, W. Techology affordances. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 April–2 May 1991; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaver, W. Affordances for interaction: The social is material for design. Ecol. Psychol. 1996, 8, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. When does technology use enable network change in organizations? A comparative study of feature use and shared affordances. MIS Quaterly 2013, 3, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, A.; Lyytinen, K. Towards a theory of affordance ecologies. In Materiality and Space. Technology, Work and Globalization; de Vaujany, F., Mitev, N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- McGrenere, J.; Ho, W. Affordances: Clarifying and evolving a concept. In Proceedings of the Graphics Interface 2000 Conference, Montréal, QC, Canada, 15–17 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M. The problem with affordance. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2005, 2, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pea, R. Practices of Distributed Intelligence and Designs for Education; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, A. Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart Hall and interactive media technologies. Media Cult. Soc. 2017, 39, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Bindings against boundaries: Entanglements of life in an open world. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 1796–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hertzberger, H. Montessori primary school in Delft, Holland. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1969, 39, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzberger, H. Space and Learning: Lessons in Architecture 3; 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, S.; Hafezieh, N. ‘Affordance’—What does this mean? In 22nd UK Academy for Information Systems International Conference: Ubiquitous Information Systems: Surviving & Thriving in a Connected Society Oxford; Griffiths, M., McLean, R., Kutar, M., Eds.; St. Catherine’s College: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, C.; Grosvenor, I. School; Reaktion: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Imms, W. Can Altering Teacher Mindframes Unlock the Potential of Innovative Learning Environments? 2016. Available online: http://www.iletc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ILETCOverview-brochure-printable.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Dovey, K.; Fisher, K. Designing for adaptation: The school as socio-spatial assemblage. J. Archit. 2014, 19, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, W.; Cleveland, B.; Fisher, K. Evaluating Learning Environments: Snapshots of Emerging Issues, Methods and Knowledge; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, B. Equitable pedagogical spaces: Teaching and learning environments that support personalisation of the learning experience. Crit. Creat. Think. 2009, 1, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mahat, M.; Bradbeer, C.; Byers, T.; Imms, W. Innovative Learning Environments and Teacher Change: Defining Key Concepts; Technical Report; LEaRN; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Young, F. Learning Environment Affordances: Bridging the Gap between Potential, Perception and Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Young, F.; Cleveland, B.; Imms, W. The affordances of innovative learning environments for deep learning: Educators’ and architects’ perceptions. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019, 47, 693–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackney, J. Teacher environmental competence in elementary school environments. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Anthropology and/as Education; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the perception of landscape: An inquiry into environmental perception and aesthetics. Innov. Approaches Res. Landsc. Health Open Space People Space 2010, 2, 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions 1999, 6, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmodiwirjo, P. Space affordances, adaptive responses and sensory integration by autistic children. Int. J. Des. 2014, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jelić, A.; Tieri, G.; De Matteis, F.; Babiloni, F.; Vecchiato, G. The enactive approach to architectural experience: A neurophysiological perspective on embodiment, motivation, and affordances. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koutamanis, A. Buildings and affordances. In Design Computing and Cognition ’06; Gero, J.S., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, J.; Fadel, G.; Battisto, D. An affordance-based approach to architectural theory, design, and practice. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C. Highlighting the affordances of designs. In Computer Aided Architectural Design Futures 2001; de Vries, B., van Leeuwen, J., Achten, H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 681–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Jeong, J.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, M. Personal cognitive characteristics in affordance perception: Case study in a lobby. In Emotional Engineering: Service Development; Fukuda, S., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, C.H.; Lim, J.S. Affordances in interior design: A case study of affordances in interior design of conference room using enhanced function and task interaction. In Proceedings of the ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–7 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Galvao, A.B.; Sato, K. Affordances in product architecture: Linking technical functions and user requirements. In Proceeding of the ASME Conference on Design Theory and Methodology, Long Beach, CA, USA, 24–28 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the body: An intentional analysis of Gibson’s ecological approach to visual perception. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1989, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporrel, K.; Caljouw, S.; Withagen, R. Gap-crossing behavior in a standardized and a nonstandardized jumping stone configuration. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, F.; Cleveland, B. A Selected Timeline of Affordance Theory; The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. An examination of constructivist and Gibsonian approaches to environmental psychology. Popul. Environ. 1981, 4, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Affordances of children’s environments: A functional approach to environmental description. Child. Environ. Q. 1988, 5, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Beek, P.; de Wit, A. Affordances en architectuur/Affordances and architecture. In The Third Exile; Rutten, J.A.G.M., Semah, J., Eds.; Arti et Amicitiae: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, J.; Ezhilan, T.; Fadel, G. The affordance structure matrix: A concept exploration and attention directing tool for affordance based design. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Design Theory and Methodology, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–7 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, B. Engaging Spaces: Innovative Learning Environments, Pedagogies and Student Engagement in the Middle Years of School. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, K. Re-Placing Flexibility: An Investigation into Flexibility in Learning Spaces and Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Woolner, P.; McCarter, S.; Wall, K.; Higgins, S. Changed learning through changed space: When can a participatory approach to the learning environment challenge preconceptions and alter practice? Improv. Sch. 2012, 15, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, C. Looking back to imagine the future: Connecting with the radical past in technologies of school design. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2014, 23, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterator, S.; Deed, C. Teacher adaptation to open learning spaces. Issues Educ. Res. 2013, 23, 315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kyttä, M. Affordances of children’s environments in the context of cities, small towns, suburbs and rural villages in Finland and Belarus. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M. The extent of children’s independent mobility and the number of actualized affordances as criteria for child-friendly environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, D. Utopian spaces of “robust hope”: The architecture and nature of progressive learning environments. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2007, 35, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.F.; Said, I. Outdoor environments as children’s play spaces: Playground affordances. In Play, Recreation, Health and Well Being; Evans, B., Horton, J., Skelton, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstead, M.; Veissiere, S.; Kirmayer, L. Cultural affordances: Scaffolding local worlds through shared intentionality and regimes of attention. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costall, A. Canonical affordances in context. Avant J. Philos.-Interdiscip. Vanguard 2012, 3, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1953; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).