1. Introduction

Nowadays, stainless steel is a well-known and widely used material, characterized by its high chromium content (more than 10.5%), to which elements are added, such as molybdenum, carbon, silicon, and nickel, leading to an improvement in corrosion resistance and its mechanical properties [

1,

2]. Usually, the thickness of the passive film is 1 to 3 nm at a minimum content of Cr [

3]. Increasing the chromium percentage will improve the stability of the passive film. Bellezze et al. [

4] demonstrated this characteristic by comparing the AISI 430 and AISI 304 stainless steels. The difference in chromium content in favor of the second material proved that it has higher corrosion resistance, while AISI 430 has a lower repassivation capacity.

The surface finishing is of great importance, as highlighted by Messinese et al. [

5]. The research was carried out on five types of stainless steel, including AISI 430. The surface roughness is important in evaluating the corrosion behavior as well as the mechanical properties. It has been demonstrated that grinding generally leads to an improvement in corrosion [

5].

The corrosion of stainless steels can be classified into two main categories: high-temperature corrosion and wet corrosion. It is important to how the passive film is affected [

6]. Among the different forms of wet corrosion are crevice, pitting and uniform corrosion, stress corrosion cracking, hydrogen-induced stress cracking, environmentally assisted cracking, and sulfide stress cracking. Kim and Lee [

7] analyzed the corrosion resistance behavior of AISI 430 stainless steel in (N

2/3.1%H

2O/2.42%H

2S)-mixed gas at 600–800 °C. The results showed that it corrodes rapidly due to the formation of FeS and Cr

2S

3 sulfides both on the surface and inward. Thus, the material is susceptible to spallation, cracking, and void formation. Crevice and pitting corrosion occur when the passive film is damaged, and they are localized. Guerra et al. [

8] highlighted the good performance of AISI 430 steel when used as a medical sensor in aggressive environments such as in sweat with different chloride concentrations. Despite the good resistance, its corrosion rate increases, especially after 7 days of exposure.

One method to improve corrosion resistance is surface functionalization, which is a topic of research for specialists in various fields. Among the surface processing methods mentioned are chemical, electrochemical, mechanical machining, ion beam, laser, and so on, applicable to several types of metallic materials, polymers, ceramic and polymer coatings, etc. As previously mentioned, surface texture is very important due to its influence on the roughness and therefore the wettability of the surface. Depending on the texturing pattern and the parameters, the surface can be hydrophobic or hydrophilic [

9,

10].

Laser surface texturing (LST) has gained increasing attention because it is a predictable, controllable, fast, and highly efficient process [

11]. That is why it has been applied to numerous types of materials such as stainless steels and aluminum alloys. Cholkar et al. [

12] show that the hydrophobicity and superhydrophobicity of surfaces are closely related to the adhesion of biomolecules. Thus, texturing with differently designed patterns can be performed so that the surface energy is reduced in the case of 7075 T6 aluminum alloy. The textured surface presented a contact angle of 157°, while the non-textured one an angle of 85°, which proves the hydrophobicity of the functionalized surface and the possibility of using this process for marine applications [

12]. The same positive results regarding the increase in hydrophobicity were obtained on the same alloy with the optimization of laser parameters [

13].

Ahuir-Torres et al. [

14] studied the corrosion behavior of LST on pure aluminum. The results showed a lower pitting corrosion in the case of textured samples compared to the untextured ones, and a much more stable corrosion mechanism [

14]. Liu et al. [

15] observed that using LST in the case of an AZ31 magnesium alloy and groove texture pattern with adequate depth led to improved corrosion resistance (probably due to the reduction in defects) and good stability in aggressive environments for a duration of 100 h. Conradi et al. [

16] obtained the same positive results regarding the increase in corrosion resistance using LST (scan line separation) at texturing of a Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy.

In a similar study, Kumar et al. [

17] fabricated a laser circular pattern of diameter 100 μm and pitch varying from 200 to 70 μm on a AISI 420 stainless steel surface. Although this alloy has a lower chromium content than AISI 430, the microtexturing results are encouraging. A surface with a maximum contact angle of 158.6° was obtained after 19 days of storage under ambient conditions. Rezayat et al. [

18], by using a nanosecond pulsed laser surface texturing on AISI 301, obtained denser oxide layers at 600 °C in molten salt that have been proven to be a protective barrier against further oxidation and to reduce the corrosion rate by 20%.

Adijāns et al. [

19] demonstrated that changing the scanning speed from 20 to 200 mm/s leads to increased corrosion resistance on AISI 304 stainless steel, due to increased surface hydrophobicity through microtexturing. In a recent study, Filatov et al. [

20] investigated the possibility of increasing the pitting corrosion resistance of AISI 430 through laser surface texturing. It was found that after surface laser texturing, different oxides of iron and chromium were formed on the surface, with a beneficial role in increasing the pitting corrosion resistance. The oxides became more active upon increasing the power density. Suslov et al. [

21] analyzed the LST influence on AISI 430. It was found that it is necessary to have a well-determined ratio between iron and chromium oxides (Cr

2O

3/Fe

2O

3 = 2.2) and elements (Cr/Fe = 0.44) to obtain an increase in corrosion resistance of 10%. On the other hand, upon increasing the roughness, the corrosion resistance decreases.

Corrosion analysis of LST involves understanding how micro-scale textures enhance corrosion resistance through various mechanisms. LST creates surfaces with improved properties, such as protective oxide layers and altered surface chemistry, which are crucial for resisting corrosion. The effectiveness of these textures can be quantified through surface roughness analysis [

22,

23], which characterizes the topography and informs the optimization of LST parameters for better corrosion performance. Laser surface texturing significantly influences the corrosion resistance of ferritic stainless steel, making it a critical area of study for enhancing material performance. This enhancement in corrosion resistance can be attributed to the unique microstructural modifications induced by laser surface texturing, which not only improve the surface roughness but also influence the wettability characteristics of the steel. By creating a more hydrophobic surface, laser processing minimizes the adhesion of corrosive agents, thereby increasing the material’s lifespan in harsh environments. Moreover, precise control over the laser parameters, such as pulse width and scanning speed, allows the tuning of surface properties, which can be optimized for specific applications, potentially leading to significant advancements in industries based on stainless steel components [

24].

Using linear polarization methods allows for a detailed understanding of the corrosion rates associated with various surface textures, providing essential insights into how specific microstructural changes influence overall performance in corrosive environments [

25]. While laser surface texturing is used for its ability to enhance corrosion resistance in ferritic stainless steel, it is essential to consider the potential drawbacks and limitations of this technology. The process of laser treatment can introduce thermal stress and microstructural changes that may inadvertently compromise the mechanical integrity of the steel. For instance, the rapid heating and cooling cycles associated with laser processing can lead to residual stress, which may result in premature failure under certain loading conditions. Furthermore, while the creation of hydrophobic surfaces is often considered to be a benefit, it may not improve corrosion resistance in all environments. In fact, in some cases, the textured surfaces could trap moisture and contaminants, leading to localized corrosion rather than preventing it [

26,

27]. Improving the corrosion resistance of ferritic stainless steel is an ongoing research topic, mainly investigated using innovative surface treatment techniques [

28,

29,

30]. The unique microstructural modifications induced by laser processing can increase the wettability characteristics of the steel, rendering it more hydrophobic. To improve the repellency of complex liquids, LST can be combined with PECVD coating, as demonstrated in [

31]. Depending on the coating materials, corrosion resistance can be improved accordingly.

While previous research has established that LST can alter the surface chemistry and wettability of AISI 430 steel, the specific role of texture pattern geometry and, more critically, the number of laser repetitions on the stability of the passive film remains unclear. Many studies highlight the potential benefits but often overlook the degradation mechanisms induced by excessive laser processing. Therefore, the purpose of this work is to systematically study the influence of two distinct LST patterns and a wide range of repetition counts (1–20 passes) on the corrosion resistance of AISI 430 stainless steel, to identify the optimal processing window that avoids detrimental effects.

This paper is a continuation of our previous research, in which we studied the in-fluence of the pattern configuration and technological parameters on the geometry [

22], wettability, and surface roughness [

10], through morphological and elemental analysis [

23] of laser surface texturing on AISI 430 stainless steel.

3. Results and Discussion

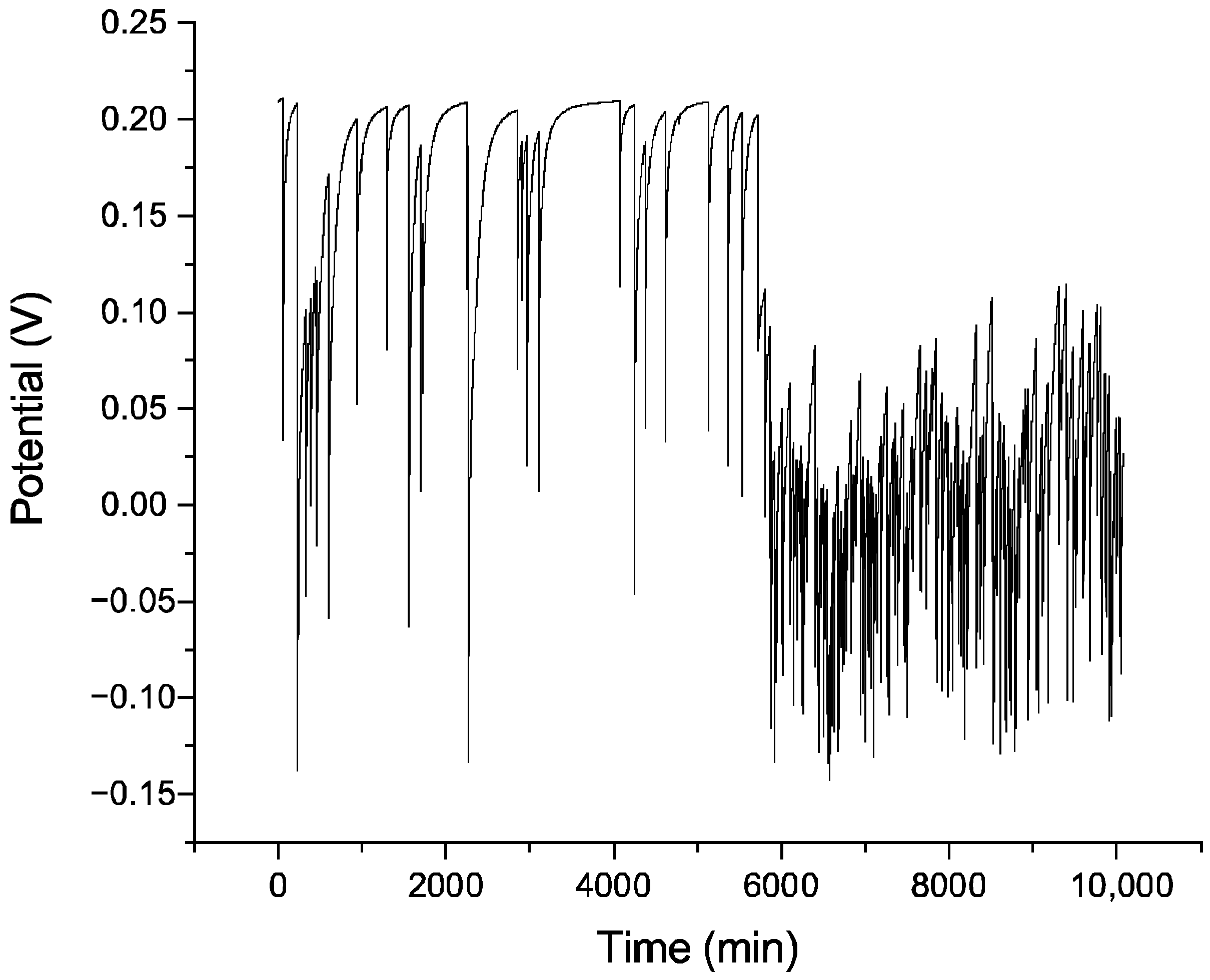

This study was performed across a 7-day testing time period to determine any significant changes in mechanical properties and corrosion rates. In

Figure 3, the graph depicts the corrosion potential during the 7-day analysis of the three concentric octo-donut pattern LST on AISI 430 stainless steel: 300 mm/s speed and 30 kHz frequency, one repetition. The current range was from 1 μA to 1 mA with the range from 10 mV to 1 V for the potential range, with 30 min as time for stabilization.

The initial potential drop is between 0 and 30 min in the analysis process, starting near −0.1 V and declining rapidly to −0.4 V, meaning an active corrosion initiation, suggesting a breakdown of the protective layer. After 30 min, the stabilization phase is observed, where the potential stabilizes at about the value of −0.4 V. The laser surface textured likely forms a non-protective layer, failing to passivate. The negative potential shift marks the increased anodic activity with the absence of potential recovery.

Figure 4 shows the corrosion potential over 7 days, with the two ellipses oriented at 90° and the overlapped-pattern LST on AISI 430 stainless steel: 300 mm/s speed and 30 kHz frequency, one repetition. The long-term evolution of corrosion potential (E

corr) provides nuanced insights into surface stability (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Both patterns exhibit a rapid initial potential drop (within ~1800 s), from approximately −0.1 V to −0.4 V vs. SCE, signifying the immediate breakdown of the native chromium-rich passive film upon immersion. This behavior confirms that even a single laser pass creates a surface more thermodynamically prone to anodic dissolution than the original, untreated steel. However, the post-breakdown behavior diverges. The ‘three octo-donut’ pattern (

Figure 3) shows a gradual potential increase after ~150,000 s, trending towards −0.3 V. This is likely not a genuine repassivation event, but rather a stifling effect caused by the accumulation of voluminous, porous corrosion products (e.g., FeOOH) that partially block the surface and limit oxygen’s diffusion to cathodic sites, consistent with a diffusion-influenced process. In contrast, the ‘two-ellipse’ pattern (

Figure 4) stabilizes at approximately −0.4 V with minimal recovery, suggesting a more sustained active dissolution state with a less obstructive corrosion product formation. This pattern-dependent difference highlights how texture geometry can influence the local retention and morphology of corrosion products, which in turn modifies the corrosion kinetics, even when the underlying cause—passive film disruption—is the same.

While the electrochemical data for both the ‘two-ellipse’ and ‘three octo-donut’ patterns exhibited similar trends of instability, subtle differences in their geometrical design may influence the initiation and progression of corrosion. The ‘two-ellipse’ pattern, with its sharp angles and perpendicular overlaps, creates a higher density of stress concentration points and more complex, confined geometries. These features can act as efficient traps for corrosive electrolytes and hinder the diffusion of oxygen, which is crucial for the self-healing of the passive film. In contrast, the more continuous and concentric nature of the ‘octo-donut’ pattern might result in a slightly less tortuous path for electrolyte penetration. However, the dominant factor governing corrosion behavior, as evidenced by the comparable potential drops in both patterns, appears to be the cumulative laser-induced damage from repetitions rather than the specific macro-geometry of the pattern itself. This suggests that while pattern design is important for other functional properties like wettability, its influence on corrosion resistance in this system is secondary to the thermal history imposed by the number of laser passes.

Since

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 revealed the inherent instability of a single laser pass, the effect of repeated texturing was systematically investigated through short-term potential measurements across 1 to 20 repetitions, as shown in

Figure 5, which presents the corrosion potential measurement for 30 min before and after 1/3/5/13/15/20 iterations of LST on AISI 430 stainless steel: speed 300 mm/s, 30 kHz frequency, two ellipses oriented at 90°, and an overlapped pattern. This data reveals a clear and critical trend: increasing the number of laser repetitions systematically shifts the corrosion potential to more negative values. The potential progresses from approximately −0.25 V for the baseline state towards −0.45 V for the highest repetition counts. This negative shift is a direct indicator of increasing thermodynamic susceptibility to corrosion. More importantly, for samples with five or more repetitions, the potential frequently falls below the critical pitting potential for stainless steels in chloride environments (typically around −0.35 V vs. SCE). This suggests that beyond a threshold of approximately five repetitions, the laser-induced damage is severe enough to not only promote general corrosion but also to significantly increase the risk of localized pitting attack. The potential traces for samples with higher repetitions (≥13) display increased noise and minor instability compared to the smoother curves of low-repetition samples. This increased electrochemical noise is indicative of a more active and heterogeneous surface, where the random breakdown and re-formation of unstable corrosion product layers or transient localized events contribute to potential fluctuations, reflecting the overall instability of the laser-damaged interface.

Our previous research [

10] has shown that the roughness of the textured surface is directly proportional to the number of repetitions, while it is inversely proportional to the processing speed. Also, the dimensions of the micro-grooves (width, depth, recast elevations, and the entire surface area) increase with the number of repetitions, as demonstrated in [

22]. This increase in roughness and geometric dimensions causes increases in the sample surface area, the thermal damage, and the electrolyte retention in the micro-grooves and on the recast material.

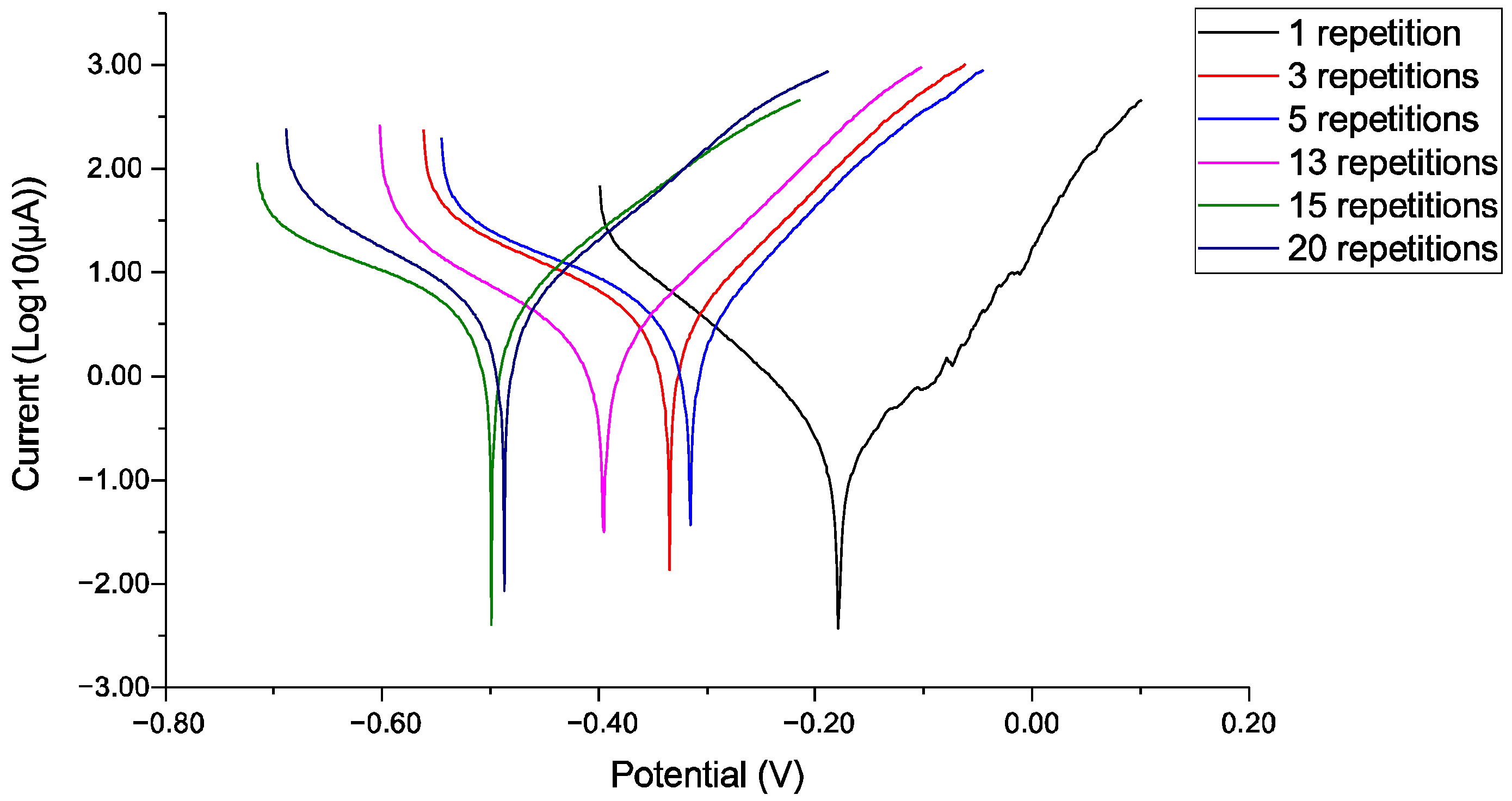

The key parameter in corrosion rate analysis is the Tafel slope (

Table 2 and

Figure 6). For fit results, the settings comprised a scan rate of 0.001 V/s with E

step of 0.001 V, with a current range selected from 10 nA to 10 mA, 5 s maximum open circuit potential time, and 0.1 mV/s stability criterion.

The evolution of the Tafel slopes (β

a and β

c) in

Table 2 provides critical insights into the changing corrosion mechanism. The sample with a single repetition shows an anomalously high anodic Tafel slope (β

a = 8.453 V/decade), which is atypical for active metal dissolution. This could indicate the formation of a highly resistive surface layer or a significant change in the anodic reaction mechanism, possibly towards transpassive dissolution or the formation of a poorly conductive corrosion product that stifles the anodic reaction. As the repetition count increases to three and five the anodic slope drops drastically to values around 0.1–0.3 V/decade, which is characteristic of an activation-controlled anodic dissolution process where the protective layer has been compromised. Concurrently, the cathodic Tafel slope (β

c) increases dramatically for samples with five or more repetitions, reaching values exceeding 11 V/decade. Such a high cathodic slope is indicative of a diffusion-limited cathodic reaction, likely due to the accumulation of porous, non-protective corrosion products (e.g., iron oxyhydroxides) that hinder the diffusion of oxygen to the cathode sites. This shift from a potentially resistive anodic control to a combination of an activation-controlled anode and diffusion-controlled cathode signifies a complete breakdown of the original protective regime.

In the case of the sample with one iteration of the LST pattern, the findings reveal an exceedingly low corrosion rate, which implies that there is a minimal amount of material that has been lost. When evaluated under the specified testing conditions, the material exhibits an impressive level of corrosion resistance. The measured value of the corrosion potential indicates a state of equilibrium where the rates of oxidation reactions and reduction reactions are balanced, thus reflecting a stable condition in the electrochemical environment of the sample. Furthermore, the anodic βa Tafel slope has been observed to be exceptionally elevated, suggesting that a substantial inhibition of the oxidation reaction occurs, which may indicate that the material exhibits enhanced protective properties against corrosion. The sample with three iterations reveals a higher value than the sample with a single iteration, particularly in terms of the corrosion analysis metrics. The corrosion potential demonstrates a modest deviation towards a more prone corrosion environment, reflecting a decline in the integrity of the oxide layer and an intensified activity resulting from polarization effects. The results for the corrosion current suggest a more rapid corrosion process, while the current density findings corroborate the escalation of corrosion activity per unit area. The Tafel slopes indicate an anodic reaction, which suggests passivation phenomena, typically associated with oxygen reduction and hydrogen evolution. However, the diminished polarization resistance in conjunction with an increased corrosion current indicates a reduction in the protective capacity of the surface sample to laser surface texture. The Tafel slope presented for the sample with five repetitions of the textured pattern has an irregularity that is inconsistent with the physical realities of standard corrosion reactions and is presumably a result of concentration polarization stemming from the depletion of reactants in proximity to the electrode, which is characterized by an unstable potential. The increased corrosion activity suggests a diminished protective environment, indicating a non-equilibrium state throughout the corrosion analysis process. For the sample that underwent 13 repetitions, any notion of “partial passivation” is overshadowed by the dominant active corrosion observed. While the corrosion rate is not the highest recorded, the electrochemical parameters reveal a compromised surface. The significantly negative potential and low polarization resistance demonstrate a weak barrier effect. The surface may temporarily abate corrosion through the formation of porous products (evidenced by the high cathodic Tafel slope), but this is a symptom of a diffusion-blocked, actively corroding system, not a robust, protective passive state. The specimen subjected to 15 iterations exhibits a markedly elevated corrosion rate, resulting in almost the total depletion of corrosion resistance. The Tafel slopes indicate an unimpeded metal dissolution process, characterized by a combination of control mechanisms, namely activation and diffusion, leading to irreversible damage that raises significant concerns for applications intended for the long term. The identified surge in corrosion indicates a regression of protective measures, implying a total disintegration of the passive film and the initiation of localized corrosion. In the case involving the sample with 20 iterations of the pattern, it has been identified that a notably low anodic slope is present, which validates the material’s tendency towards facile dissolution under the prescribed conditions. Furthermore, this sample demonstrates a diminished capacity for corrosion resistance, which is indicative of corrosion behavior that ranges from moderate to actively pronounced rates of corrosion. The examination of the sample with LST plays an instrumental role in ascertaining the efficacy of the processing technique employed for corrosion resistance.

The non-textured sample has a 0.00015 mm/year corrosion rate and negligible material loss, indicating a high corrosion resistance. An extremely low corrosion current (0.011 μA) offers an effective barrier against dissolution. The polarization resistance result (1.824 MΩ) confirms the outstanding protection with all parameters consistent (intact passive films and highly stable electrochemical behavior). For the non-textured sample, the residual stress is not present, has an excellent oxide film adhesion, and the electrochemical heterogeneity is presented as uniform. In the samples undergoing iterations of between 1 and 13 times, there is a low presence of residual stress and a partial delamination. Repeated laser surface texturing modifies surface thermodynamics, making certain regions, grain boundaries, and micro-cracks more susceptible to electrochemical attack. Additional passes can fracture or thin passive oxide films, exposing fresh metal to aggressive environments. The textured pattern creates heterogeneous microstructures, leading to localized anodic/cathodic regions. Increased passes amplify the potential differences across the surface, accelerating localized dissolution. The residual stress is extreme when the number of repetitions of the pattern increases from 13 times to 20, whereupon the oxide film adhesion becomes fully detached, and the electrochemical heterogeneity presents a severe dissolution in terms of micro-galvanic coupling between the deformed and non-deformed zones. The accumulated residual stresses and dislocation density from 15 passes create permanent high-energy sites, accelerating anodic reactions. Repeated deformation disrupts oxide layer regeneration.

The progressive deterioration of corrosion resistance with increasing laser repetitions is fundamentally a consequence of cumulative thermal damage. Each laser pulse delivers a rapid thermal cycle involving extreme heating (~107–108 K/s) and subsequent quenching. With multiple repetitions (N), this cycle is applied iteratively to the same location, leading to an accumulated energy density (Eaccum = N × Fluence) that drives several interconnected degradation pathways:

Chromium Depletion and Oxide Alteration: The high localized temperature can exceed the vaporization point of chromium oxides. This leads to the selective depletion of chromium from the melt zone, a process confirmed by the EDS results, which show reduced Cr/Fe ratios at texture edges, as can be seen below the elemental EDS distribution. The resulting surface oxide is consequently richer in less-protective iron oxides (Fe

2O

3, Fe

3O

4) [

21]. Furthermore, the rapid solidification inhibits the formation of the dense, crystalline Cr

2O

3 structure that are typical of a good passive film, favoring a more disordered, defective oxide.

Microstructural Transformation and Defect Introduction: The heat-affected zone (HAZ) experiences grain growth, and in ferritic steels, the quenching effect can induce the localized formation of martensite or other metastable phases at grain boundaries. More critically, the thermal expansion coefficient mismatch between the surface melt zone and the bulk substrate, compounded over multiple cycles, generates significant tensile residual stresses. These stresses, combined with the introduced dislocation networks, create permanent high-energy sites that are electrochemically active and serve as preferential paths for chloride ion penetration and pit initiation.

Inhibition of Repassivation: The combined effect of chromium depletion and a stressed, defect-rich microstructure severely hampers the material’s ability to self-heal. Repassivation requires chromium diffusion to the surface in order to form a new oxide layer. The laser-altered zone, with its depleted Cr reservoir and disrupted lattice, cannot supply chromium at the necessary rate, leaving fresh metal exposed at defect sites for prolonged periods, as evidenced by the lack of potential recovery in the Ecorr-t plots.

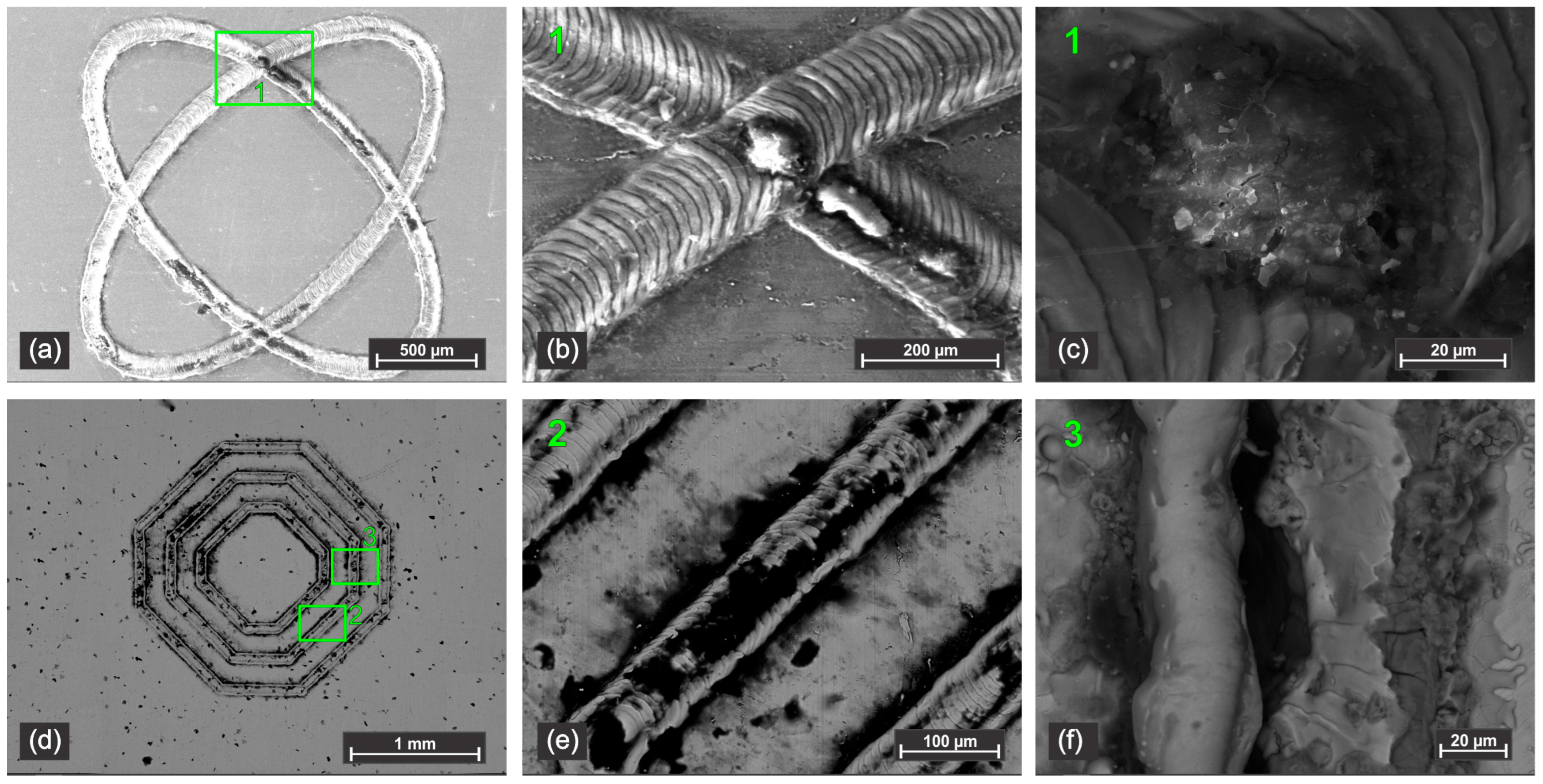

The initial stages of corrosion attack on the laser-textured surfaces are revealed in the SEM images taken after only 30 min of exposure to the NaCl electrolyte (

Figure 7). While the overall texture geometry remains visible, close inspection shows the onset of localized degradation. In both the ‘two-ellipse’ (

Figure 7a,b) and ‘three octo-donut’ (

Figure 7c,d) patterns, the edges of the laser tracks and overlapping regions appear to be the most vulnerable places. These areas, which have likely experienced the highest thermal input and resultant microstructural changes, show incipient pitting and surface roughening. This provides direct visual evidence for the electrochemical instability recorded in the first 30 min of the potential-time measurements (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), where the rapid potential drop signified the breakdown of passivity. The texture itself seems to create a topology in which certain features act as stress concentrators and the preferred sites for chloride ion adsorption, initiating the corrosion process at discrete locations rather than uniformly.

After seven days of exposure, the corrosion damage is extensive and severe, as captured in

Figure 8. The samples subjected to a higher number of laser repetitions exhibit a more pronounced surface failure. Dense populations of corrosion pits are evident across the textured areas (e.g.,

Figure 8a–c,f). The presence of widespread salt stains (likely crystallized NaCl and corrosion products such as FeO(OH) and Cr-oxychlorides) indicates prolonged and uncontrolled dissolution of the metal surface. This visual evidence aligns perfectly with the high corrosion rates calculated from the Tafel analysis (

Table 2) for samples with high repetition counts. Furthermore, the morphology of the damage supports the proposed mechanism of disrupted passivation. The laser-induced defects, such as micro-cracks and regions with delaminated oxide (visible as sharp, dark lines and crevices in

Figure 8d,e), provided direct pathways for the corrosive solution to penetrate and attack the underlying bare metal, preventing the formation of a stable, protective passive film. The ideal ‘air-trapping’ pockets theorized for superhydrophobic surfaces have been completely compromised, leading to direct and sustained contact between the electrolyte and a highly active, damaged surface.

The synergy between electrochemical metrics and microscopic evidence creates a comprehensive failure model. The negative shift in corrosion potential (E

corr) and the increase in corrosion current (I

corr) measured for high-repetition samples are the quantitative electrochemical signatures of the severe pitting and widespread dissolution observed in the SEM images. Specifically, the fluctuations in the potential-time curves (

Figure 5) for these samples, indicative of metastable pitting, find their physical manifestation in the incipient pits at the edges of laser tracks seen in

Figure 7. As the damage progresses, these metastable pits evolve into stable, deep pits and crevices visible after 7 days (

Figure 8), which accounts for the high corrosion rates recorded in

Table 2. The diffusion-limited cathodic process suggested by the high β

c Tafel slopes is visually confirmed by the extensive, crust-like salt stains that blanket the surface, physically blocking oxygen transport. Thus, the microscopy does not merely illustrate the corrosion; it validates the mechanisms inferred from the electrochemical data, showing a surface whose designed functionality has been entirely overwhelmed by its metallurgical degradation.

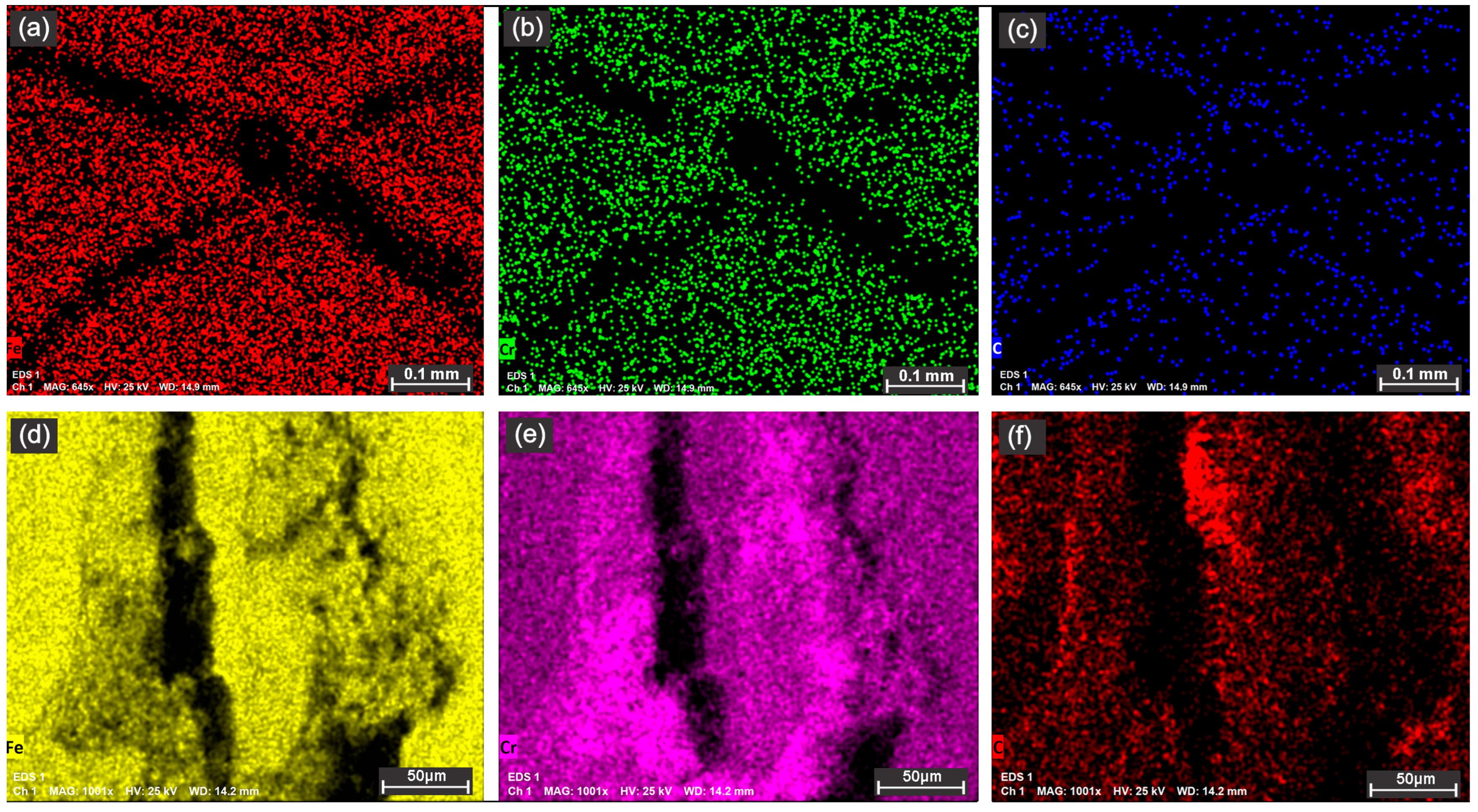

In

Figure 9a–c of the 90° overlapped ellipses, the reduction in Fe, Cr, and C content can be observed on the contour of the laser tracks, except for the intersection area of the two traces, where the content of the analyzed elements increases. In

Figure 9d–f of the concentric octo-donuts, the expulsion of Cr and C from the contour of the laser tracks on the elevation of the recast material is noted.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (

Figure 9) provides direct chemical evidence for the mechanisms proposed. The observed depletion of Fe and Cr along the contours of the laser tracks is attributed to two primary processes during laser interaction. (i) Selective Oxidation: The high-temperature melt pool is highly reactive, leading to preferential oxidation of Fe and Cr to form mixed oxides. (ii) Vaporization/Expulsion: The intense localized heating can cause the vaporization of metallic elements and oxides, with chromium having a relatively high vapor pressure at these temperatures. The expelled material often re-deposits as recast debris on the texture shoulders, explaining the increased signal at these elevations (

Figure 9d–f).

This chemical modification has direct consequences for corrosion. The protective nature of stainless steel relies on a passive film with a Cr/Fe ratio significantly higher than the bulk alloy (often Cr/Fe > 1 in the film versus ~0.44 in the bulk AISI 430) [

3]. Laser-induced Cr depletion creates subsurface zones where this ratio is reversed (Cr/Fe < 0.44), making them incapable of forming a stable, continuous Cr

2O

3 layer. These Cr-deficient zones become strongly anodic relative to the surrounding bulk material or Cr-rich oxides, establishing potent micro-galvanic couples. The resulting accelerated dissolution of these anodic sites is the chemical origin of the increased pitting susceptibility and general corrosion rates measured electrochemically.

The clear identification of a degradation threshold (~five repetitions) provides guidance for industrial process optimization. For AISI 430 components where corrosion resistance is paramount, LST should be confined to the minimal ‘safe zone’ (1–3 passes) to impart topography without catastrophic metallurgical damage. To achieve enhanced surface functionality (e.g., superhydrophobicity) beyond this zone, a hybrid surface engineering strategy is recommended. This involves using a minimal LST treatment to create the necessary micro/nano-topography for mechanical interlocking or wettability modification, followed by the application of a conformal protective coating.

For instance, a thin, hydrophobic silane-based coating could be applied post-LST. The textured surface provides increased surface area and anchor points for superior coating adhesion, while the coating itself acts as the primary corrosion barrier, isolating the laser-damaged substrate from the electrolyte. This approach effectively decouples the surface functionality from the substrate’s corrosion performance. An alternative or complementary post-processing step is stress relief annealing. A controlled thermal treatment below the alloy’s sensitization temperature could mitigate the detrimental residual stresses and promote chromium diffusion back to the surface, potentially restoring some of the inherent corrosion resistance while preserving the textured geometry.