Effect of Nitrogen Content on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of 316LN Stainless Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cavitation Erosion Tests

2.3. Microstructural and Surface Characterization

3. Results

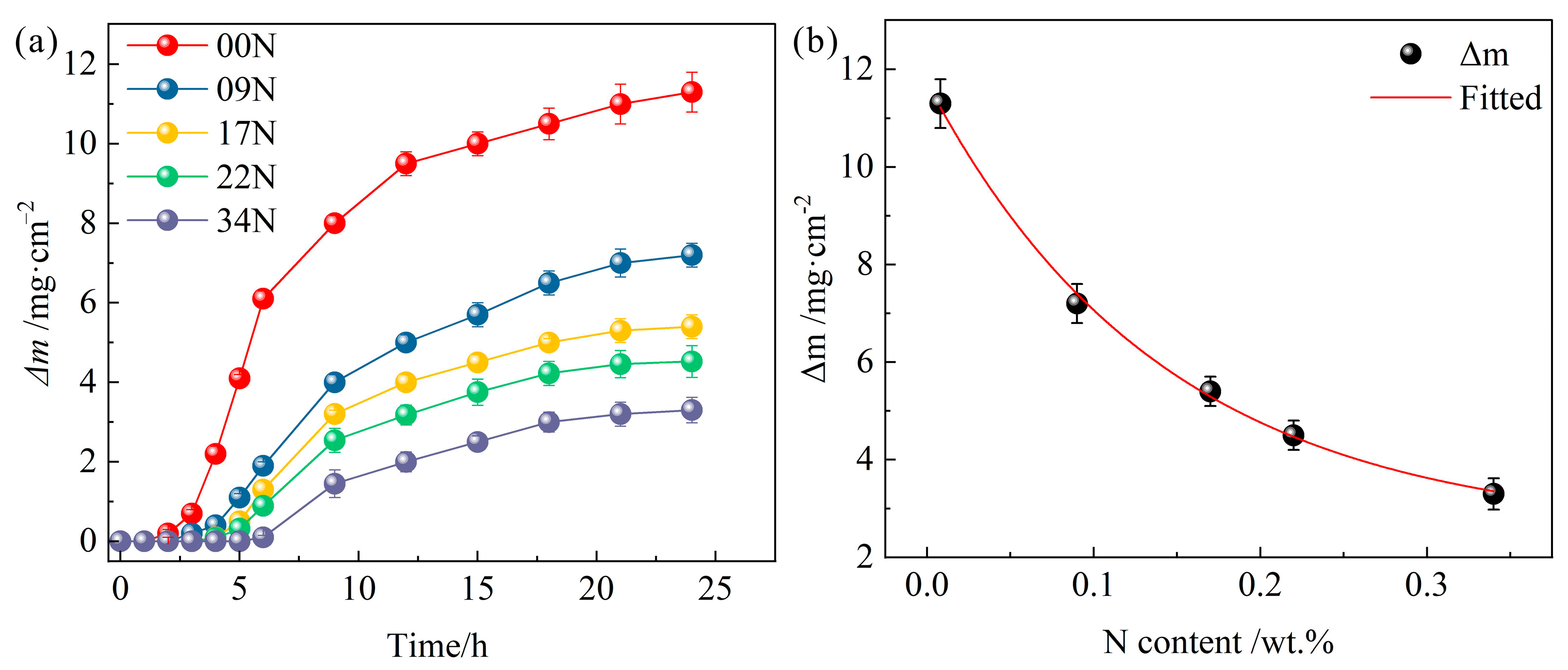

3.1. Cavitation Mass Loss

3.2. Three-Dimensional Surface Morphology and Roughness After Cavitation

3.3. Short-Term Cavitation Damage Behavior and Mechanism

3.4. Surface Morphology After 24 h Cavitation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- After 24 h of cavitation, cumulative mass loss decreased significantly with nitrogen content. Compared to 00N, 09N, 17N, 22N, and 34N steels showed reductions of 36%, 52%, 60%, and 71%, respectively. Surface roughness also decreased exponentially with increasing nitrogen.

- (2)

- Cavitation damage initiated at twin boundaries and high-angle grain boundaries and then propagated into twin interiors and intragranular deformation bands.

- (3)

- Microhardness increased from ~140 HV (00N) to ~260 HV (34N). TEM showed that dislocations evolved from disordered to dense slip bands and planar slip arrays, with stacking faults forming, indicating that nitrogen strengthens the material and enhances resistance to impact deformation.

- (4)

- The results indicate that nitrogen exists as interstitial atoms forming short-range ordered regions, which reduce SFE and promote planar slip, thereby contributing to the enhanced cavitation resistance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, U.; Ress, J.; Bosch, J.; Bastidas, D. Stress corrosion cracking mechanism of AISI 316LN stainless steel rebars in chloride contaminated concrete pore solution using the slow strain rate technique. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 335, 135565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Umezawa, O. Fracture toughness and martensitic transformation in type 316LN austenitic stainless steel extra-thick plates at 4.2 K. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 862, 144122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Kim, S.-J.; Kang, J.-H. Effects of short-range ordering and stacking fault energy on tensile behavior of nitrogen-containing austenitic stainless steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 836, 142730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, J.; Wu, X.; Han, E.-H.; Ke, W. Effects of boric acid and lithium hydroxide on the corrosion behaviors of 316LN stainless steel in simulating hot functional test high-temperature pressurized water. Corros. Sci. 2022, 198, 110157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Li, W. Effect of chloride threshold on pitting behavior of 316LN stainless steel in sour water solution by electrochemical analysis. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-H.; Cheng, P.-M.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, G.; Xin, L.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Li, D.-P.; Zhang, H.-B.; Sun, J. Dynamic strain aging-mediated temperature dependence of ratcheting behavior in a 316LN austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 862, 144503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Chi, J.; Zhou, C. Enhanced wear resistance and new insight into microstructure evolution of in-situ (Ti,Nb)C reinforced 316 L stainless steel matrix prepared via laser cladding. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2020, 128, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Martin, J. Cavitation erosion of materials. Int. Met. Rev. 1986, 31, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Hong, S.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y. The coupling effect of cavitation-erosion and corrosion for HVOF sprayed Cu-based medium-entropy alloy coating in 3.5wt.% NaCl solution. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 2936–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.F.; Silveira, L.L.; Cruz, J.R.; Pukasiewicz, A.G. Cavitation resistance of FeMnCrSi coatings processed by different thermal spray processes. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 5, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Long, J.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, K. Cavitation erosion-corrosion behaviour of Fe-10Cr martensitic steel microalloyed with Zr in 3.5% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2021, 184, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Reddy, K.M.; Wang, X. Effects of nitrogen on the microstructure and mechanical properties of an austenitic stainless steel with incomplete recrystallization annealing. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, X.; Ke, W.; Yang, K.; Jiang, Z. Cavitation erosion resistance of high nitrogen stainless steel in comparison with low N content CrMnN stainless steel. Tribol.-Mater. Surf. Interfaces 2007, 1, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.D.; Chen, R.D.; Liang, P. Enhancement of cavitation erosion resistance of 316 L stainless steel by adding molybdenum. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2017, 35, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveen, C.; Christopher, J.; Ganesan, V.; Reddy, G.P.; Albert, S.K. Influence of varying nitrogen on creep deformation behaviour of 316LN austenitic stainless steel in the framework of the state-variable approach. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 803, 140503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, H.-B.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Zhang, T.; Dong, N.; Zhang, S.-C.; Han, P.-D.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.-G. Designing for high corrosion-resistant high nitrogen martensitic stainless steel based on DFT calculation and pressurized metallurgy method. Corros. Sci. 2019, 158, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Barella, S.; Peng, Y.; Guo, S.; Liang, S.; Sun, J.; Gruttadauria, A.; Belfi, M.; Mapelli, C. Modeling and characterization of dynamic recrystallization under variable deformation states. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 238, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolantonio, M.; Hanke, S. Damage mechanisms in cavitation erosion of nitrogen-containing austenitic steels in 3.5% NaCl solution. Wear 2021, 464, 203526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, H.; Tan, L.; Yang, K. A novel biodegradable high nitrogen iron alloy with simultaneous enhancement of corrosion rate and local corrosion resistance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 152, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawers, J.; Bennett, J.; Doan, R.; Siple, J. Nitrogen solubility and nitride formation in Fe-Cr-Ni alloys. Acta Metall. Et Mater. 1992, 40, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G32-2016; Standard Test Method for Cavitation Erosion Using Vibratory Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Cavitation erosion behavior of high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel: Effect and design of grain-boundary characteristics. Mater. Des. 2021, 201, 109496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Ang, A.S.; Mahajan, D.K.; Singh, H. Cavitation erosion resistant nickel-based cermet coatings for monel K-500. Tribol. Int. 2021, 159, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saller, G.; Spiradek-Hahn, K.; Scheu, C.; Clemens, H. Microstructural evolution of Cr–Mn–N austenitic steels during cold work hardening. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 427, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerold, V.; Karnthaler, H. On the origin of planar slip in fcc alloys. Acta Metall. 1989, 37, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeraj, T.; Mills, M. Short-range order (SRO) and its effect on the primary creep behavior of a Ti–6wt.%Al alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 319, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Laplanche, G. Effects of stacking fault energy and temperature on grain boundary strengthening, intrinsic lattice strength and deformation mechanisms in CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloys with different Cr/Ni ratios. Acta Mater. 2023, 244, 118541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Han, W.; Huang, C.; Zhang, P.; Yang, G.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z. High strength and utilizable ductility of bulk ultrafine-grained Cu–Al alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 201915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Kondo, N.; Shibata, K. X-ray absorption fine structure analysis of interstitial (C, N)-substitutional (Cr) complexes in austenitic stainless steels. ISIJ Int. 1990, 30, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanini, A.S.; Audouard, J.-P.; Marcus, P. The role of nitrogen in the passivity of austenitic stainless steels. Corros. Sci. 1994, 36, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliznuk, T.; Mola, M.; Polshin, E.; Pohl, M.; Gavriljuk, V. Effect of nitrogen on shortrange atomic order in the feritic ε phase of a duplex steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 405, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, S.; Ding, J.; Chong, Y.; Jia, T.; Ophus, C.; Asta, M.; Ritchie, R.O.; Minor, A.M. Short-range order and its impact on the CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nature 2020, 581, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenarjhan, N.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J. Effects of carbon and nitrogen on austenite stability and tensile deformation behavior of 15Cr-15Mn-4Ni based austenitic stainless steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 742, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriljuk, V.; Shivanyuk, V.; Shanina, B. Change in the electron structure caused by C, N and H atoms in iron and its effect on their interaction with dislocations. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 5017–5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenfeldt, S.; Grossmann, S.; Lohse, D. A simple explanation of light emission in sonoluminescence. Nature 1999, 398, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, J.-P.; Michel, J.-M. Fundamentals of Cavitation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, L.; Soares, G.C.; Isakov, M.; Hokka, M. Effects of strain rate on strain-induced martensite nucleation and growth in 301LN metastable austenitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitzke, C.; Schröder, C.; Ullrich, C.; Mandel, M.; Krüger, L.; Volkova, O.; Wendler, M. Evaluation of strain-induced martensite formation and mechanical properties in N-alloyed austenitic stainless steels by in situ tensile tests. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 808, 140930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, H.; Vidhyashree, S.; Sudha, C.; Raju, S. Kinetics of static recrystallization and strain induced martensite formation in low carbon austenitic steels using impulse excitation technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 1962–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | C | Cr | Ni | Mo | Si | S | P | Fe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00N | 0.008 | 0.015 | 18.2 | 12.47 | 2.52 | 0.47 | 0.0055 | 0.013 | Bal. |

| 09N | 0.09 | 0.02 | 18.15 | 12.36 | 2.51 | 0.49 | 0.0044 | 0.015 | Bal. |

| 17N | 0.17 | 0.018 | 18.3 | 12.55 | 2.52 | 0.45 | 0.0039 | 0.011 | Bal. |

| 22N | 0.22 | 0.018 | 18.23 | 12.45 | 2.52 | 0.39 | 0.0045 | 0.019 | Bal. |

| 34N | 0.34 | 0.02 | 18.27 | 12.57 | 2.51 | 0.75 | 0.005 | 0.011 | Bal. |

| Alloys | 00N | 09N | 17N | 22N | 34N |

| Regimes | 1150 °C/ 150 min | 1200 °C/ 30 min | 1200 °C/ 70 min | 1200 °C/ 80 min | 1150 °C/ 95 min |

| D(μm) | 112 ± 2 | 110 ± 3 | 112 ± 3 | 115 ± 1 | 107 ± 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Q.; Yu, J.; Ji, Y.; Deng, K. Effect of Nitrogen Content on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of 316LN Stainless Steel. Metals 2025, 15, 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111270

Wang Y, Wang W, Xiao Q, Yu J, Ji Y, Deng K. Effect of Nitrogen Content on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of 316LN Stainless Steel. Metals. 2025; 15(11):1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111270

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yong, Wei Wang, Qingrui Xiao, Jinxu Yu, Yingping Ji, and Kewei Deng. 2025. "Effect of Nitrogen Content on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of 316LN Stainless Steel" Metals 15, no. 11: 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111270

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, W., Xiao, Q., Yu, J., Ji, Y., & Deng, K. (2025). Effect of Nitrogen Content on the Cavitation Erosion Resistance of 316LN Stainless Steel. Metals, 15(11), 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15111270