1. Introduction

When examining the electrochemical potentials of different structural materials, magnesium is an idealized material for scientific inquiry because it has one of the smallest electrochemical potentials, while also possessing the lowest density for a structural metal and a good strength-to-weight ratio. Of engineering significance, magnesium is of great interest to the automotive and aerospace industries. The lack of adequate corrosion resistance; however, makes the use of magnesium impractical in many potential structural applications that would require the metal to be exposed to the environment [

1]. Research shows that alloying magnesium (Mg) with aluminum (Al), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), and certain rare earth metals can greatly improve the corrosion resistance with a minimal increase in density [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The most common types of magnesium alloys are AM (Mg-Al-Mn) and AZ (Mg-Al-Zn) variations in various percentages of the secondary and tertiary elements. The addition of 2–10% aluminum to magnesium has been shown to increase the corrosion resistance [

2,

7], but other research demonstrated that a lower percentage of alloying aluminum produces the best corrosion resistance as it minimizes β-phase Mg

17Al

12 particles, which act as microgalvanic sites within the α-Mg phase [

8,

9]. Increased corrosion resistance can also be achieved through grain refinement. In other words, as the grain size decreased, the magnesium corrosion rate decreased [

10,

11]. Also, refining the β-phase to be fine and continuous creates a barrier between the α-Mg grains and hinders the propagation of corrosion [

12]. However, balancing the contrasting β-phase effects in traditional magnesium alloys can be problematic. Thus, a combination of methods, dependent upon the specific application for the magnesium alloy, is best for optimum corrosion resistance. More traditional methods of coating, painting, and lubricating the surface of magnesium are also quite effective in certain applications. Continued research on different methods to improve magnesium’s corrosion resistance is needed. However, thus far, there has not been a study on how the geometry of a structural component influences the corrosion rate of magnesium. The work herein is a study of the effects of geometry and related boundary conditions on the corrosion rate of pure magnesium. Having this baseline regarding pure magnesium sets up further experiments, whereby alloying studies can be conducted to elucidate further chemical composition effects arising from local galvanic cells. This becomes important when designing a structural component that is made of magnesium alloys.

Based on previous magnesium alloy corrosion studies, a corrosion damage model was developed by Walton et al. [

13]. and Horstemeyer et al. [

14], which considers general, intergranular, and localized corrosion mechanisms, termed “pitting” in the most general application of the term, according to the following equation:

where the total damage is additive decomposition from general corrosion (gc), intergranular corrosion (ic), and localized (pitting) corrosion (pc). The model multiplicatively decomposes pitting into pit nucleation (η), pit growth (ν), and pit coalescence (c),

the corrosion damage model includes research on magnesium alloys such as AZ31 [

15,

16], AZ61 [

17], AE44 [

18,

19,

20], AM30 [

3], and AM60 [

21], all in immersion environments. The corrosion model is used to quantify the associated damage of the pure magnesium sphere and cube. The rate forms of Equations (1) and (2) are shown by the following,

where

is the total damage rate,

is the time rate of change in the thickness or loss in surface area related to general corrosion,

is the time rate of change in the volume fraction related to intergranular corrosion, and

is the time rate of change in the volume fraction related to pitting corrosion associated with nucleation, growth, and coalescence. Herein,

is the nucleation rate of the pits (pit number density rate change),

is the growth rate of the pits (average pit volume rate change), and

is the coalescence rate of the pits (pit nearest neighbor distance rate change). The mathematical details of the corrosion model are given in Walton [

13]. This mathematical model is used to unite the different corrosion mechanisms (general, intergranular, and pitting) in terms of measurable quantities obtained from the experimental data to quantify the total corrosion damage. In Walton et al. [

13], throughout the corrosion testing period in either the immersion or salt spray environment, one mechanism (generalized, localized, or intergranular) of corrosion could dominate while the other mechanisms contribute little to the corrosion damage at a particular time. The dominance of any of the mechanism(s) can change at any given time for the material in question. However, these equations, or any corrosion model equations, do not have any functions related to the geometry of the specimen or component when used in a complex boundary value problem.

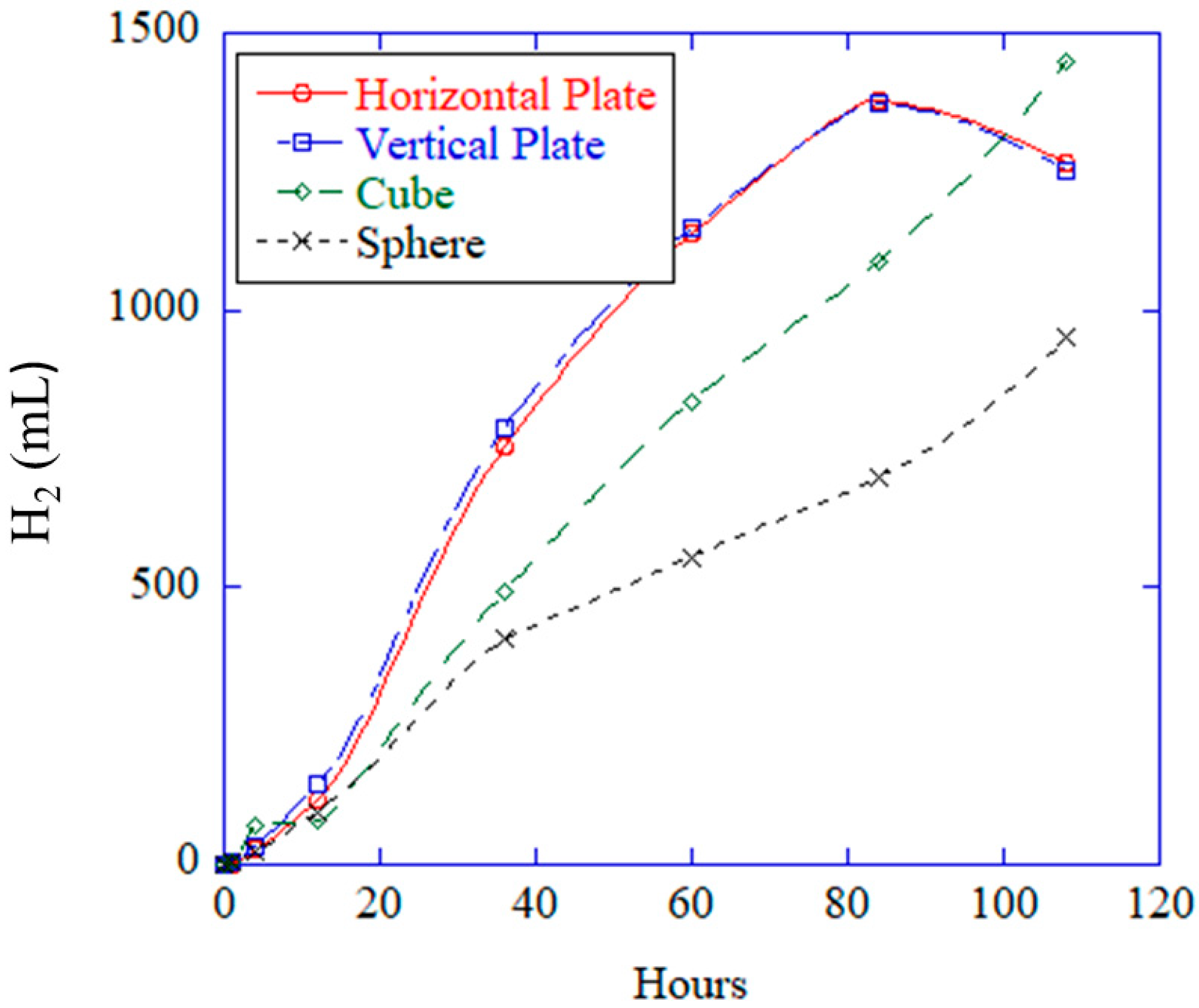

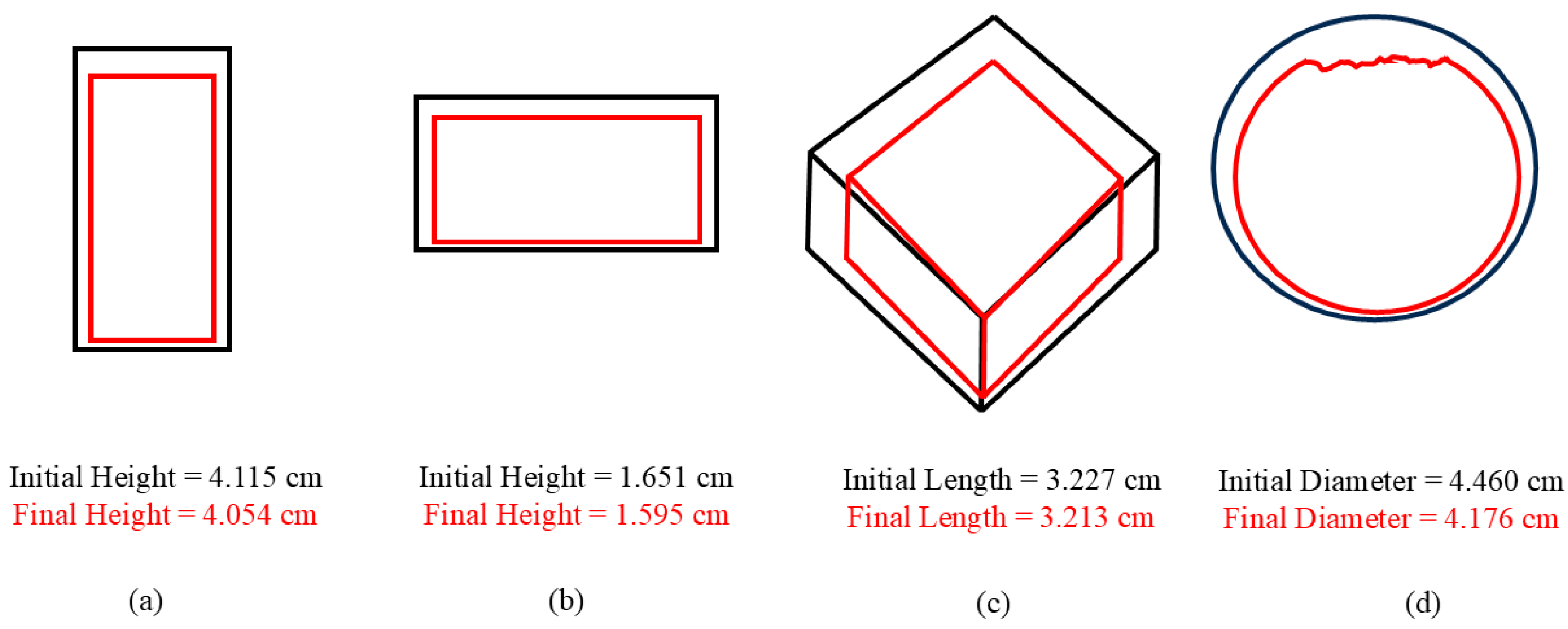

The new experimental study described in this work is the first of its kind to help assess the geometric effects on corrosion mechanisms by employing a vertical plate, a horizontal plate, a sphere, and a cube of the same surface area. Note that Equations (1)–(4) do not include geometry effects as they act only as the constitutive equations [

13,

14], where the full set of conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy is required with the geometries and the constitutive model to solve the associated boundary value problem of corrosion. If one were to ask, which geometry (cube, sphere, or rectangular plate) would allow the most corrosion with the same surface area, which would you pick? It is not obvious, so we created an immersion environment that was used to allow for evolved hydrogen gas measurements and direct observations of the samples during corrosion to distinguish the different corrosion rates from the different geometries.

The following section includes a description of the materials and methods.

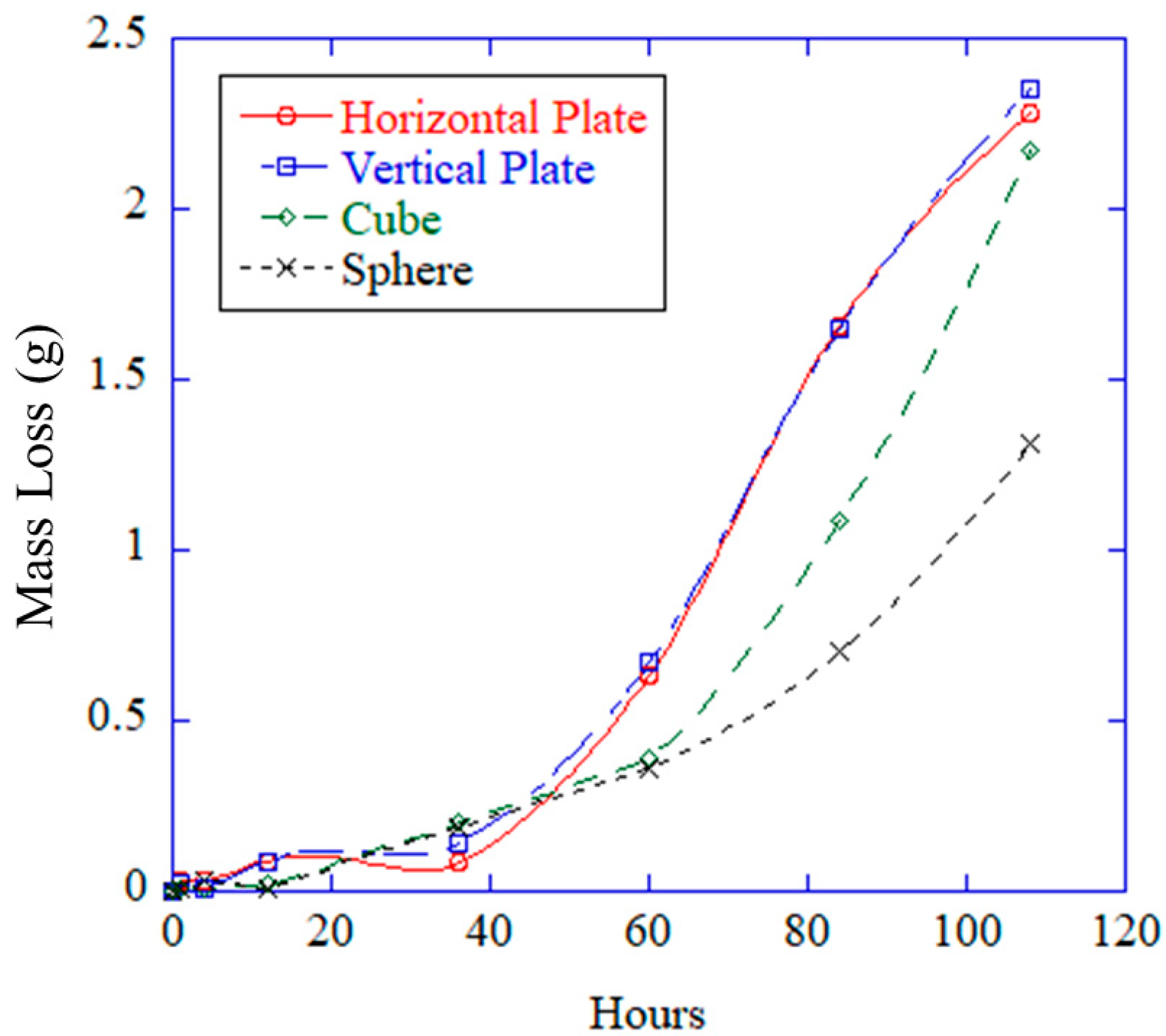

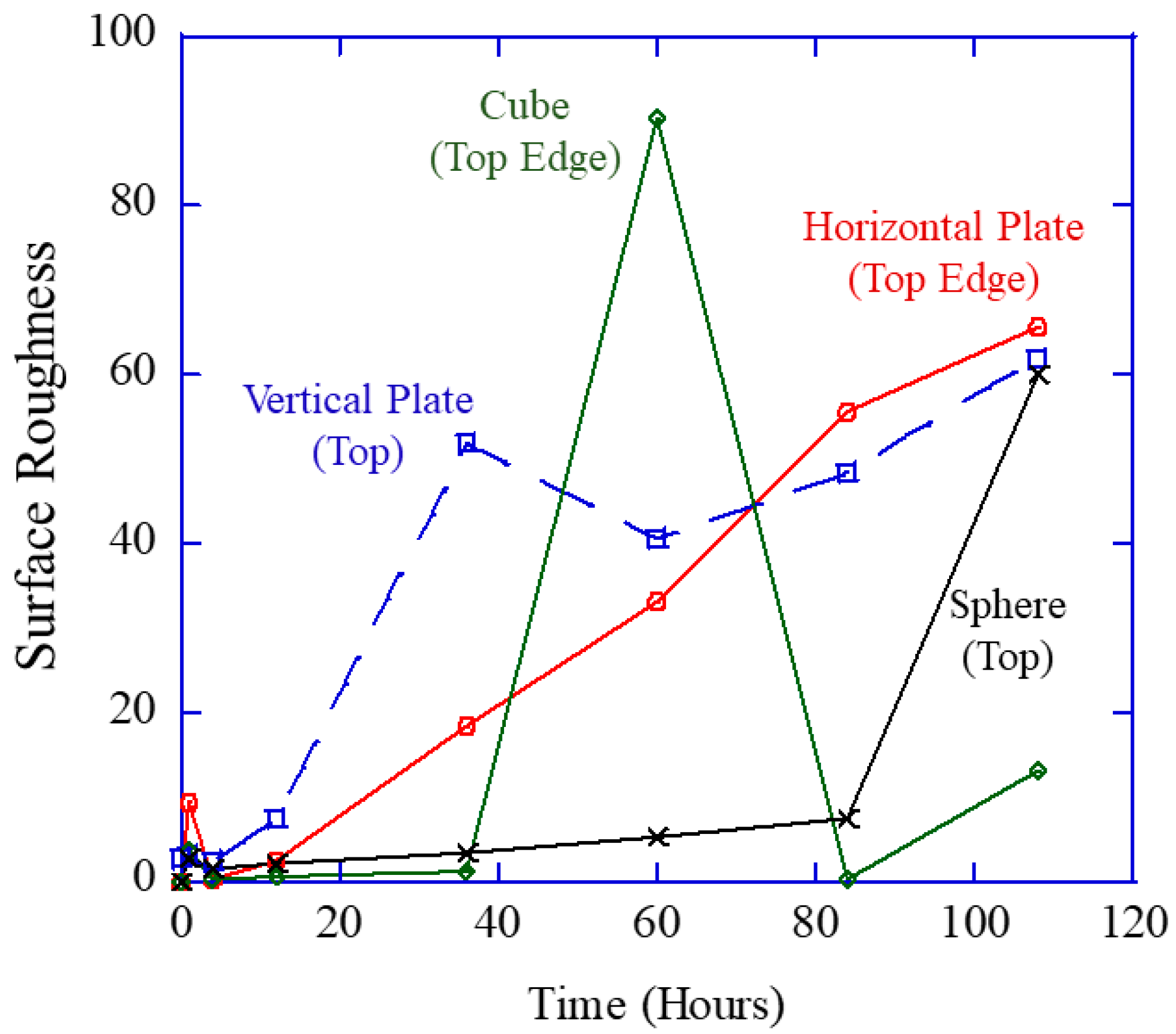

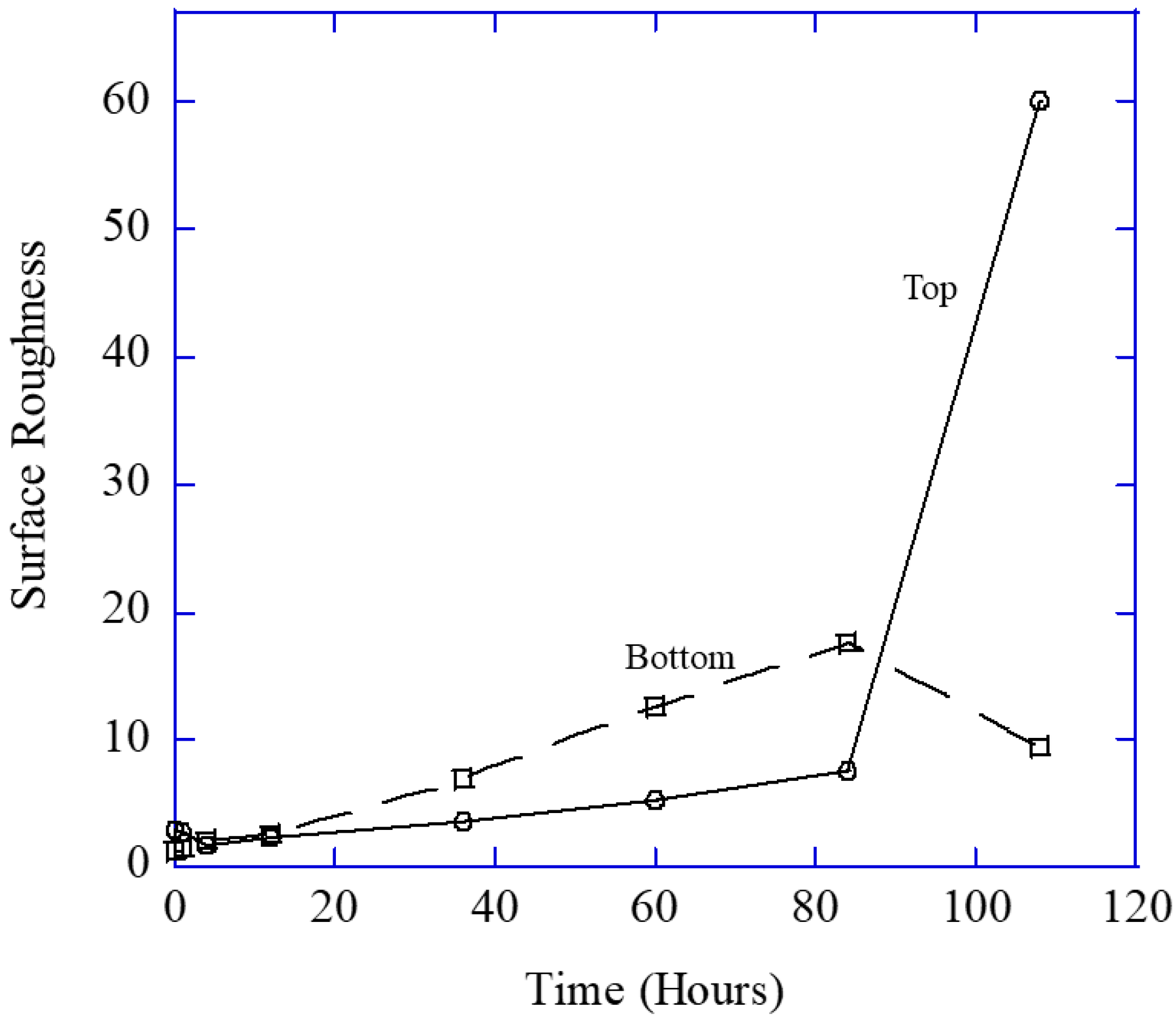

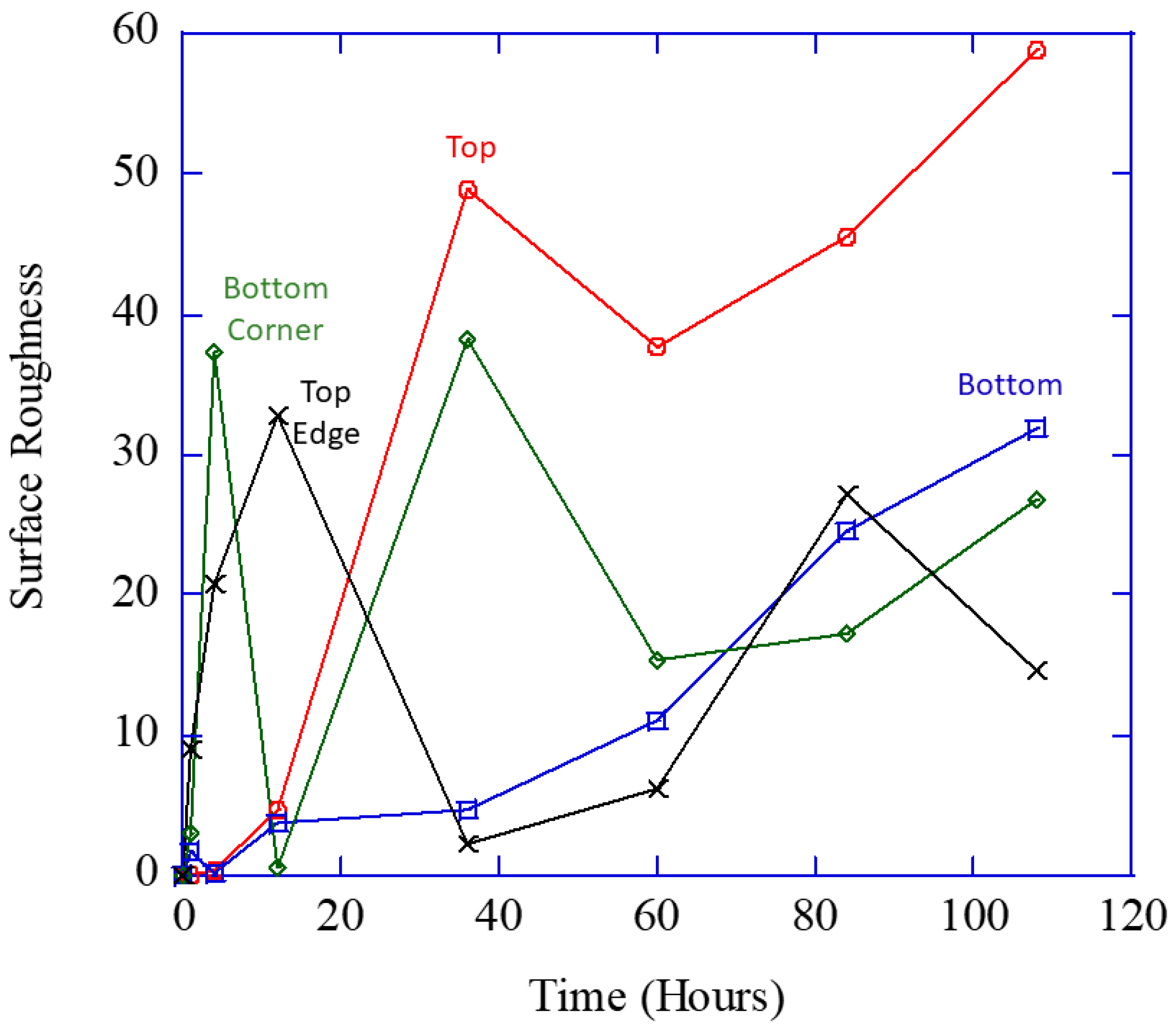

Section 3 describes a flat surface of pure magnesium over time to create a baseline for the descriptions of the different corrosion mechanisms: (1) localized pitting from surface roughness measurements, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) measurements, and Optical Microscopy analysis; (2) general corrosion from mass loss measurements; (3) intergranular corrosion from optical microscopy; and (4) overall corrosion from hydrogen capture measurements.

Section 4 then covers the different geometry effects related to localized pitting, general corrosion, and intergranular corrosion.

Section 5 summarizes the overall conclusions.

3. Results and Discussion: Corrosion Mechanisms of Pure Magnesium

Different corrosion mechanisms occur within magnesium alloys: localized “pitting” corrosion related to Equation (2), general corrosion embedded in Equation (1), and intergranular/intragranular corrosion embedded in Equation (1). Pitting was observed in all of the pure magnesium specimens, no matter the geometry.

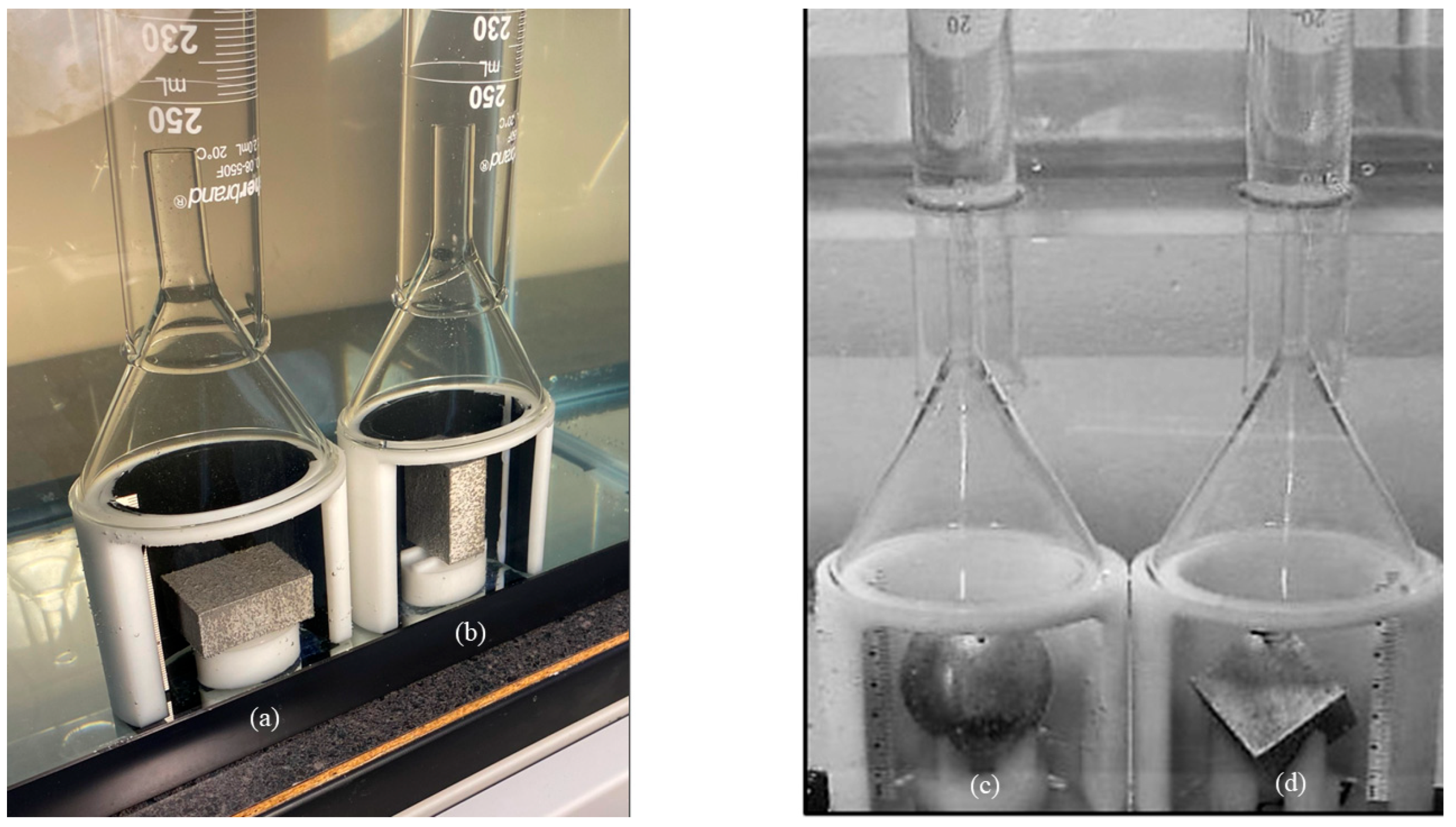

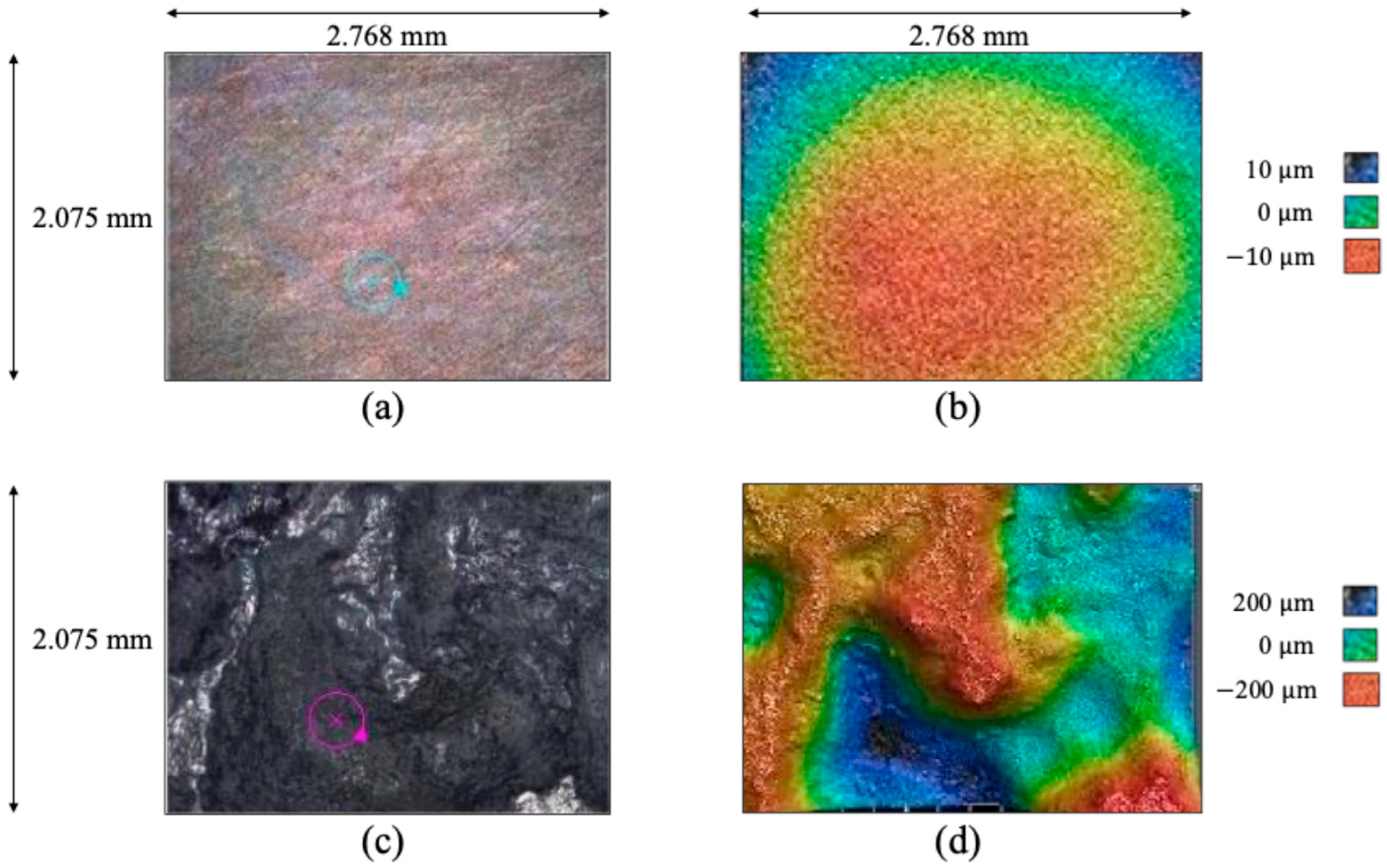

Figure 2 shows optical micrographs (a,c) with associated laser profilometry color mappings (b,d) showing a pit that nucleated and grew on the pure magnesium sphere prior to corrosion (a,b) and after 108 h of corrosion (c,d). Note that this particular pit nucleated from a region (a,b) with a surface roughness initially of 2.934 mm that grew into (c,d) a pit with a surface roughness of 108.6581 mm. The circle in (a) and (c) shows the same location where the pit nucleated and grew. The dark blue region in (d) shows the pit.

Analysis showed that the intergranular corrosion was not a significant contributor to the total corrosion of the sample. Instead, intragranular corrosion dominated as many localized regions were observed within single grains that were imaged. In addition, the remaining scratches from polishing also resulted in localized corrosion, especially demonstrated in the difference between

Figure 2b and

Figure 2c, where the scratches appear wider and darker. By

Figure 2d, the scratches are no longer as intense. Corrosion can also occur at twin boundaries and grain boundaries.

Table 1 shows the relative number of localized corrosion sites at grain boundaries, twin boundaries, and in the bulk of the sample (making allowance for previously existing surface defects). The number of localized corrosion sites at each location over the course of an hour did not show any notable preference for grain boundaries or twin boundaries compared to the bulk of the sample.

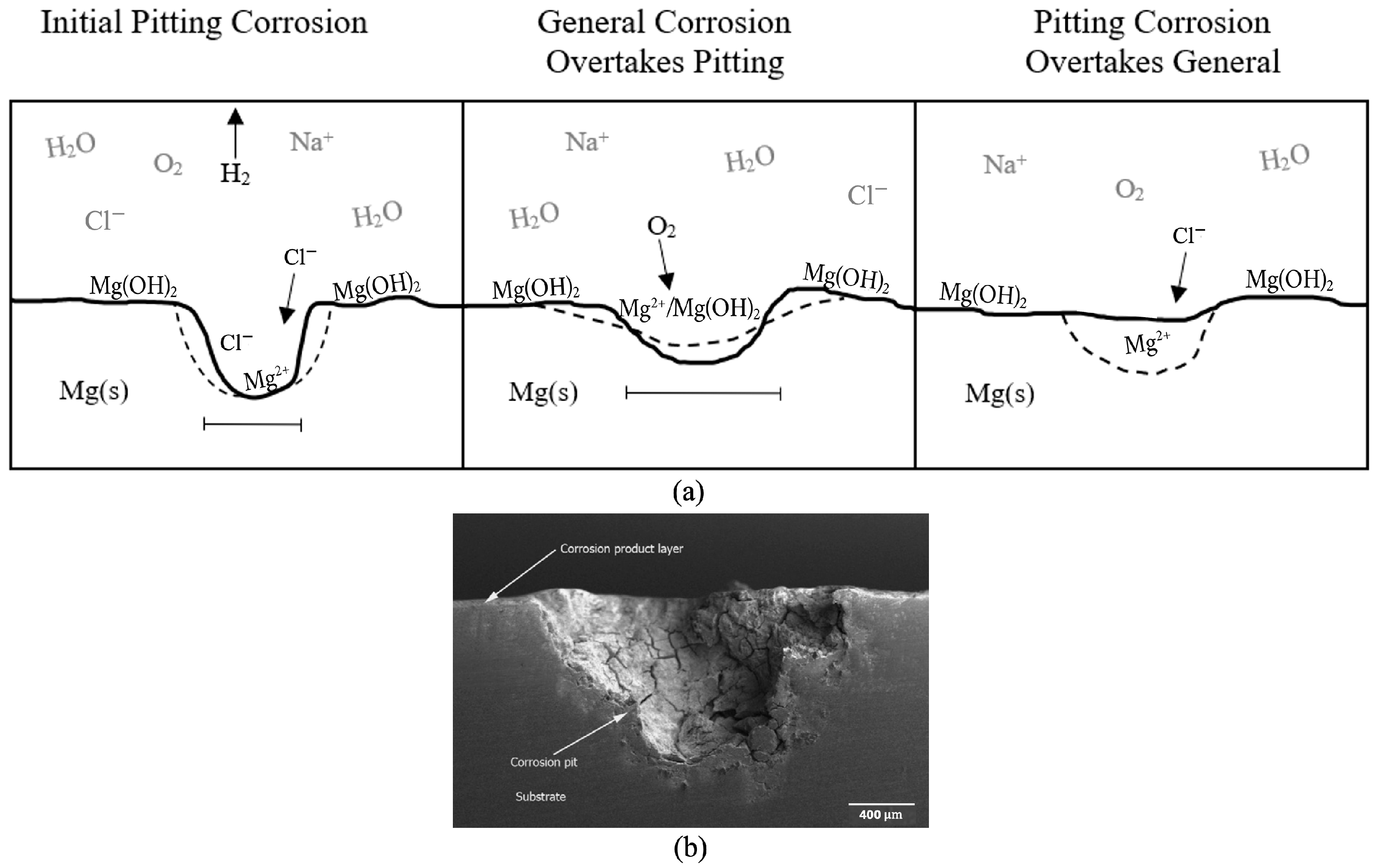

Figure 3 shows a diagram of the corrosion progression that was observed and could be expected for any geometry, and an associated pit image that was retrieved from Scanning Electron Microscopy. Magnesium does not readily maintain a protective oxide layer, or passivate, when exposed to the environment, unlike steel [

7,

22], although an insoluble, weakly bonded magnesium oxide film, MgO, can be formed. As a result, magnesium undergoes localized corrosion at a much greater rate due to the uninhibited exposure of the pure magnesium surface to the corrosive species. Chemical reactions tend to occur in the most energetically favorable way to restore equilibrium [

23,

24,

25]. This occurs on both a local and global level in a system. Because there is little sustained passivation in magnesium, there is a continual surplus of reactants (Mg metal atoms) that pushes the equilibrium towards the products via the most energetically favorable path. Therefore, the initial localized corrosion that readily occurs in magnesium is the most energetically favorable path for corrosion to occur in the early hours of testing. Therefore, the assumption is made that the localized corrosion depth observed in the surface roughness analyses (

Figure 3) is due to “pitting” effects and is not affected by added thickness from a protective oxide layer.

From

Figure 3, we ascertained that the initial pitting corrosion with chloride anion attack is pictured first (0–30 h). The chloride ions caused local breakdown of the rapidly formed protective film. These negative ions continued to draw in positive hydrogen ions that react with the available electrons and create positive magnesium ions inside the pits until the cross-sectional area was large enough for dissolved oxygen to enter and repassivate the surface of the pits. This is because magnesium hydroxide, Mg(OH)

2, is only lightly soluble in water, but is soluble in an acidic environment, which would be present in the pits due to the presence of chloride and hydrogen ions. Pictured second is the general corrosion overtaking the pitting corrosion through O

2 passivation (30–84 h), forming Mg(OH)

2 and MgO. Once the surface was lightly repassivated, general corrosion became the dominant mechanism to smooth out the surface of the sample, as the entire surface was covered with a layer of Mg(OH)

2. Pictured third is the pitting again dominating because the chloride ions once more dissolve the magnesium hydroxide film and form local pits, or the magnesium hydroxide film flakes off the surface, freeing up fresh magnesium to form pits. This increased pitting was seen from 84 to 108 h. During this time frame, the pit depth increased, signifying an increase in surface roughness and a decrease, in general, corrosion. The magnesium surface would cycle through these mechanisms until all solid metal was corroded.

One way to measure general corrosion was to quantify the thickness loss of the pure magnesium specimens, which occurred when the magnesium reacted with the aqueous environment to form a magnesium hydroxide film, according to the following equation:

While the film was protective, the aqueous chloride anions rapidly dissolved the protective film by reacting with the film to produce the following chemical reaction:

Thus, a fresh magnesium surface was exposed to the corrosive environment. Through this mechanism, the thickness and mass loss occur [

1,

7,

20,

26]. The presence of dissolved oxygen can change the equilibrium and drive the reaction to produce more Mg(OH)

2 and MgO and reform the lightly protective film [

18,

27]. General corrosion also decreased in the pitting effects, as it has a morphological smoothing effect on the surface, decreasing both the pit size and depth [

20]. As the general corrosion takes over, the pits become smaller until the surface is smoothed. Then the chloride anions dissolve the protective film to form pits, and the cycle begins again.

The intergranular corrosion for pure magnesium was negligible in the polished sample after one hour of corrosion (

Figure 2). Twins, or partial misalignments, were observed throughout the surface of the polished magnesium sample prior to corrosion. Optical images of a single pit at the different time increments showed that pit nucleation primarily occurred at twin boundaries, grain boundaries, and intragranular sites on previously existing surface defects (

Table 1). These areas are particularly susceptible to corrosive attack because of the additional space provided by the misorientation of atoms and notches or ridges on the surface. Aung et al. [

10] observed that intra-granular corrosion (general corrosion) in the α-Mg grains dominated over inter-granular corrosion in AZ31 magnesium alloy. Walton et al. [

15] expounded on this observation for AZ31 by noting that the inter-granular corrosion area fraction (ICAF) is directly related to the formation of β-phase Mg

17Al

12 on the grain boundaries. The same trend of negligible intergranular corrosion was observed in pure magnesium, though for different reasons, as there was no β-phase. Since the grain boundaries are not cathodically protected by the β-phase, a very similar pit nucleation rate was observed throughout the entire sample with no particular preference for the grain boundaries. Since we do not have the β-phase in this pure magnesium, the intergranular corrosion mechanism is considered equivalent to the pitting corrosion and is not considered a separate corrosion mechanism. Considering the large grain size of pure magnesium, as well as the rapid nucleation and growth of pits that initially occurred, followed by significant coalescence of pits and general corrosion, the expectation was that there would be only negligible intergranular corrosion, as was observed. However, another factor that must be considered is the presence of twins, which has also been shown to increase the corrosion rate [

10].

The presence of twins generally accelerates the intragranular corrosion rate in magnesium alloys [

10]. Twinning is prevalent in pure magnesium and magnesium alloys because of the constraints from the hexagonal close-packed atomic configuration. Twinning creates a partial misorientation that is vulnerable to corrosive attack by chloride anions, as there is additional space for the attack to occur. When looking at

Table 1, the pit number was comparable at all three times for the three locations, namely twin boundary, grain boundary, and within the grains, in the corrosion environment, thus signifying that pit nucleation occurs almost evenly at twin boundaries, grain boundaries, and surface defects. This data indicates that, for intergranular corrosion to preferentially occur at the twin boundaries, additional elements must be present, which causes a change in the corrosion rate.

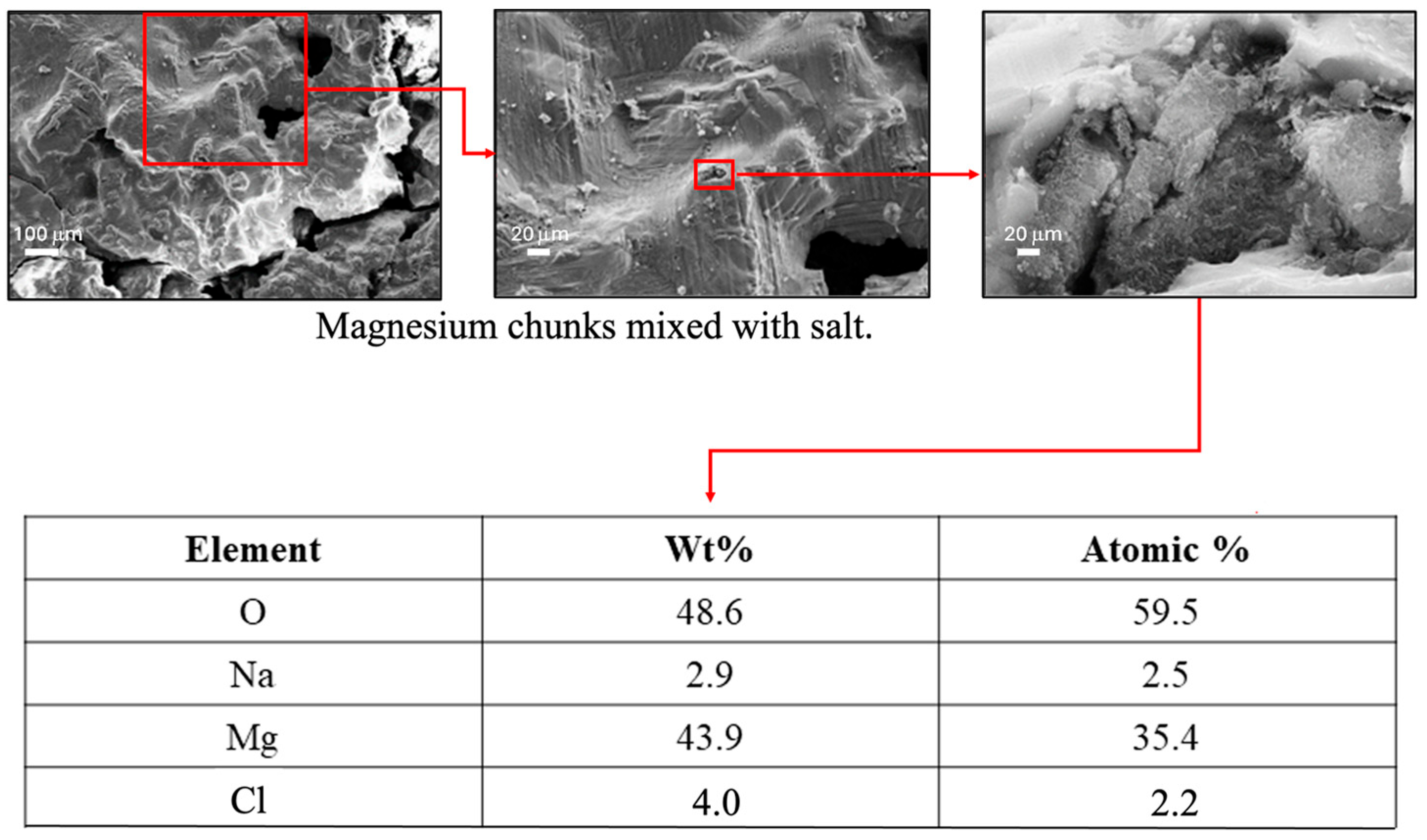

Following each increment of testing, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) were performed on the corrosion products formed during the tests to determine the precipitate’s chemical composition.

Figure 4 shows (a) the precipitate that formed during the corrosion experiments at 90×, along with SEM images of the precipitate at magnifications of (b) 250×, and (c) 4780×.

Figure 4 also shows the EDS analysis results. The sizable percentage of magnesium and oxygen denotes the presence of MgO and/or Mg(OH)

2. Since these are both corrosion by-products of water and magnesium, the presence of both would further indicate that corrosion is occurring, with the removed magnesium forming precipitates that fall out of solution.

After each increment of testing, all specimens were cleaned in DI water, sonicated for 15 min in DI water, weighed, and analyzed with the laser profilometer (Talysurf CLI 2000, Taylor Hobson Precision Ltd., Leicester, UK). As such, no solid remnants were left on the surface. Laser profilometry was performed following each corrosion increment. In general, a 1 mm by 1 mm area was scanned using a laser beam profilometer for a duration of 3 h 42 min at different locations on each specimen. The scanning speed was 500 µm/s, with a spacing of 0.5 µm and a resolution of 2001 points. For example,

Figure 5 shows results from laser profilometry measurements of the surface of the pure magnesium surface at different times: (a) t

0 = 0 h of corrosion showing distributed uniformity at the micron scale, (b) t

36 = 36 h of corrosion showing differences between 30 microns and 160 microns, and t

108 = 108 h of corrosion showing changes in surface up to 475 microns (0.475 mm). The greatest corrosion penetration occurred on the cold-mounted cube face at t

108. Upon completion of the corrosion tests, the laser profilometry 2D images were analyzed using ImageJ (

https://imagej.net/Welcome, accessed on 3 November 2025) [

28] software to determine the number of pits, average pit area, and pit area fraction.

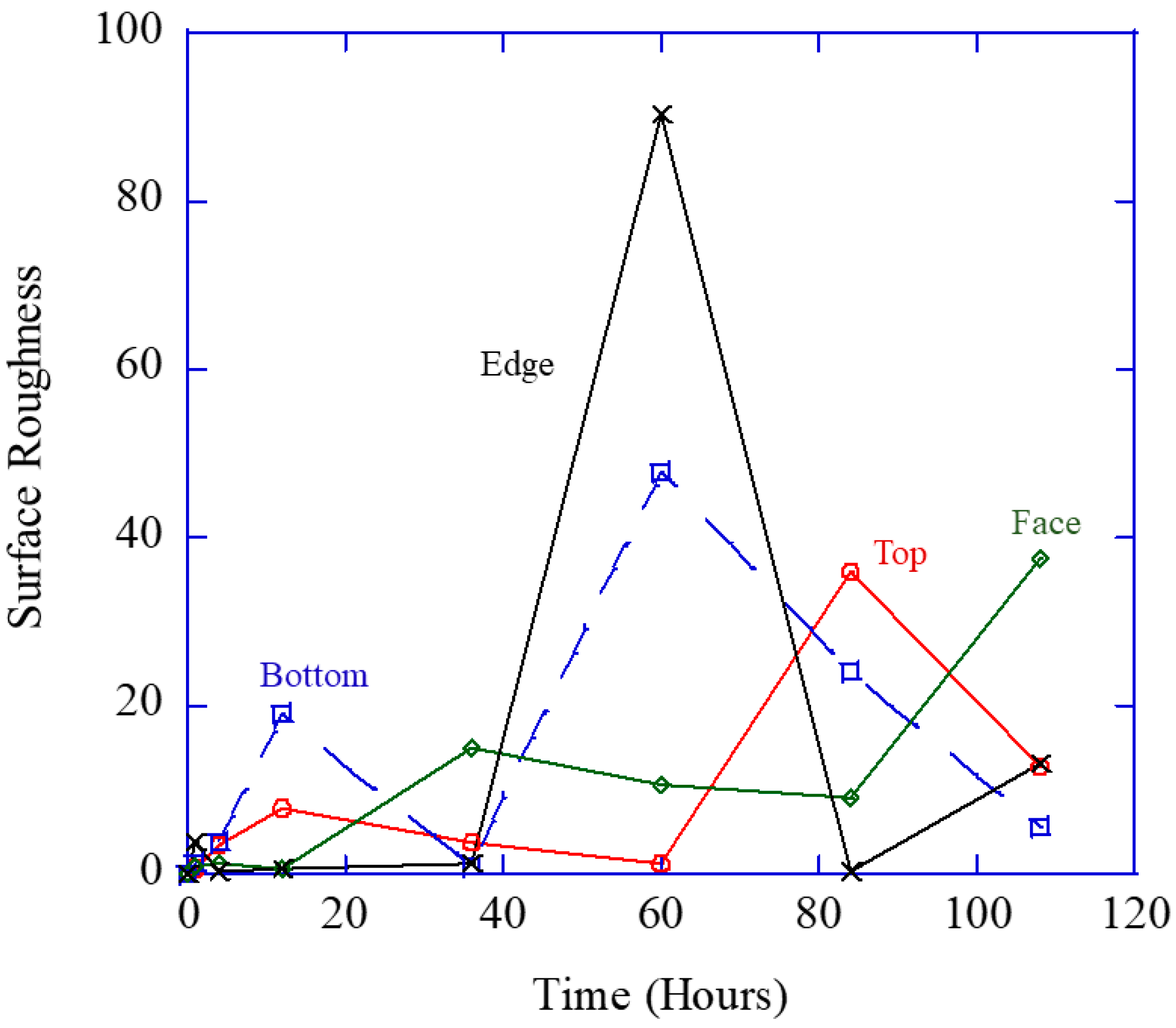

The development of the surface roughness of magnesium over the testing period can be observed in

Figure 5. The pit depth and pit area both exhibited a marked increase with time as can be qualitatively observed by the assorted colors in

Figure 5.

Figure 5a–c shows the progression of localized corrosion over time. In

Figure 5a, the range from dark blue to red-pink is 29 μm, indicating a relatively smooth surface. Slight unevenness was observed on the surfaces prior to corrosion, but the surface roughness range varied by less than 40 μm for all three regions across the 1 mm by 1 mm area that was analyzed. After 36 h (

Figure 5b), the range from dark blue to red-pink has increased to 190 μm. The dark blue areas are very wide, indicating the development of a pit, as indicated by the indented area. Where pits have not formed, the surface is red, indicating height. After 108 h (

Figure 5c), the range from dark blue to red-pink is 0.45 mm, indicating the growth of the pits into the magnesium. Looking at the pit that is present on the left side of

Figure 5c, one can see that the pit is covering a large area, denoting pit growth and coalescence. The red-pink surface on the right side of the image demonstrates that general corrosion has evened out a portion of the surface as well.

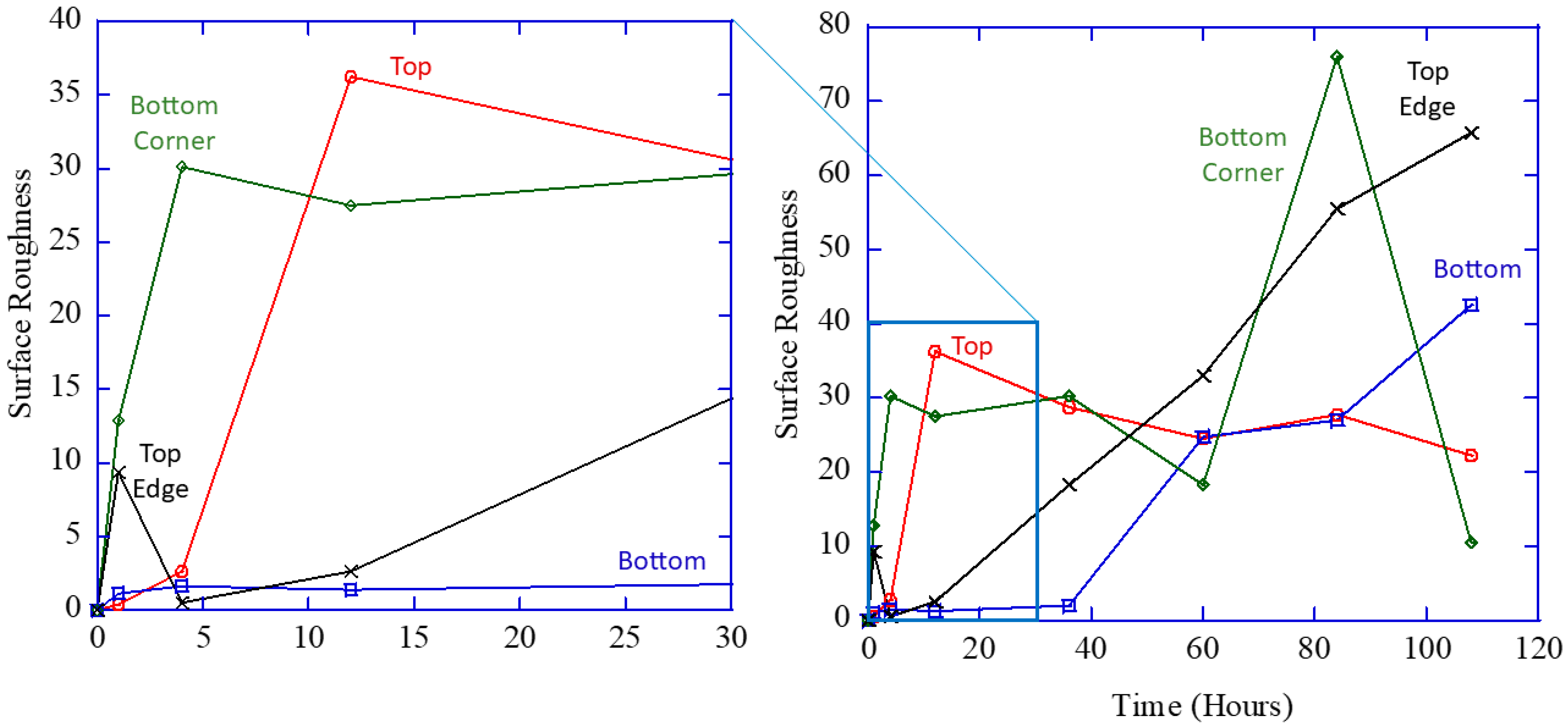

Figure 6 makes the point that the total damage (area fraction) is most related to the pit size and not the number density or pit depth.

Figure 6 shows the pit number density (

hp in Equation (2) reflecting the localized nucleation events), volume (size) changes (

vp from Equation (2)) over time, the pit depth over time, and area fraction (

fpc from Equation (2)).

Figure 6 shows a similar initial increase and then drop-off for the localized pit number density and pit depth from all three regions. The increases and decreases in pit depth in the different regions denote the mechanism change from localized to generalized corrosion.

Figure 6 shows that after 12 h, the localized pit size (

vp) and the total volume fraction (

Φpc) garnered from the ImageJ [

28] results dramatically increased, which effectively summarizes the multiplication of the number of localized corrosion sites and localized corrosion area. This experimental data shown in

Figure 6 concurs with the multiplicative decomposition of the area fraction equaling the pit number density multiplied by the pit (size) area on the surface shown in Equation (2).