Effects of Repeated Forward Versus Repeated Backward Sprint Training on Physical Fitness Measures in Youth Male Basketball Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Approach to the Problem

2.3. Linear Sprint Speed Time

2.4. Y-Agility Test

2.5. Countermovement Jump Test

2.6. Standing Long Jump Test

2.7. Repeated Sprint Ability Test

2.8. The Training Program

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

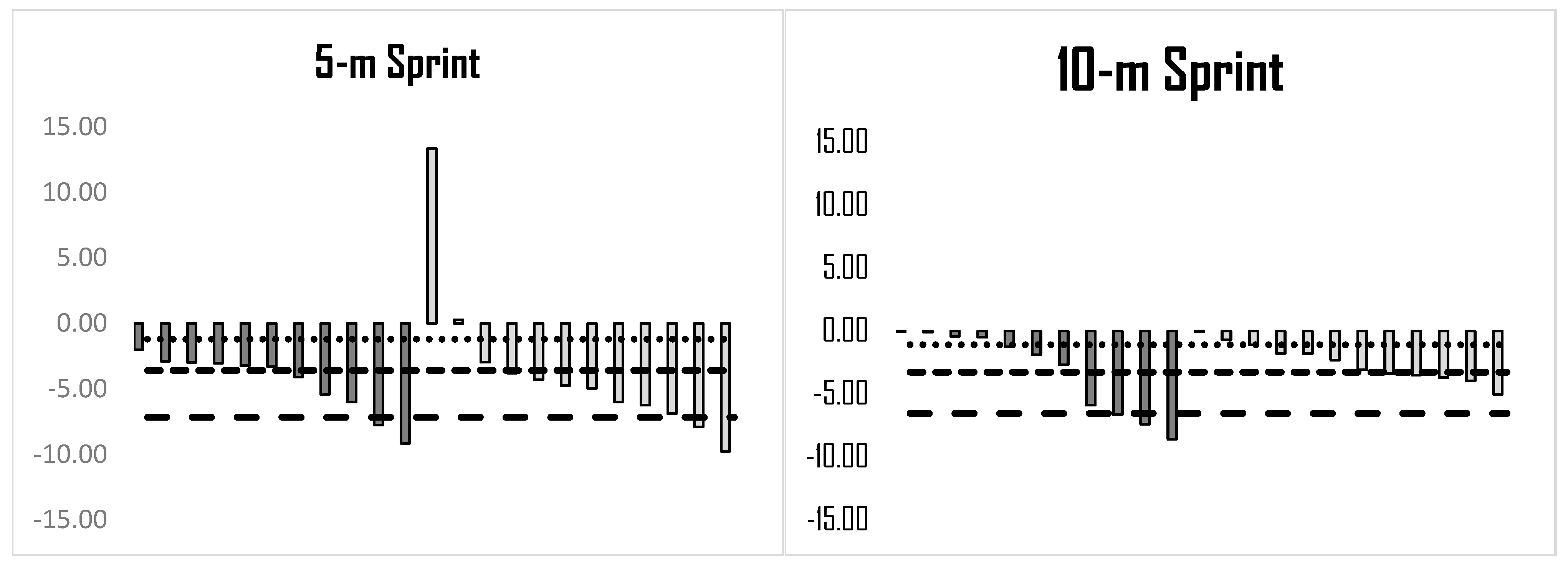

3.1. Linear Sprint

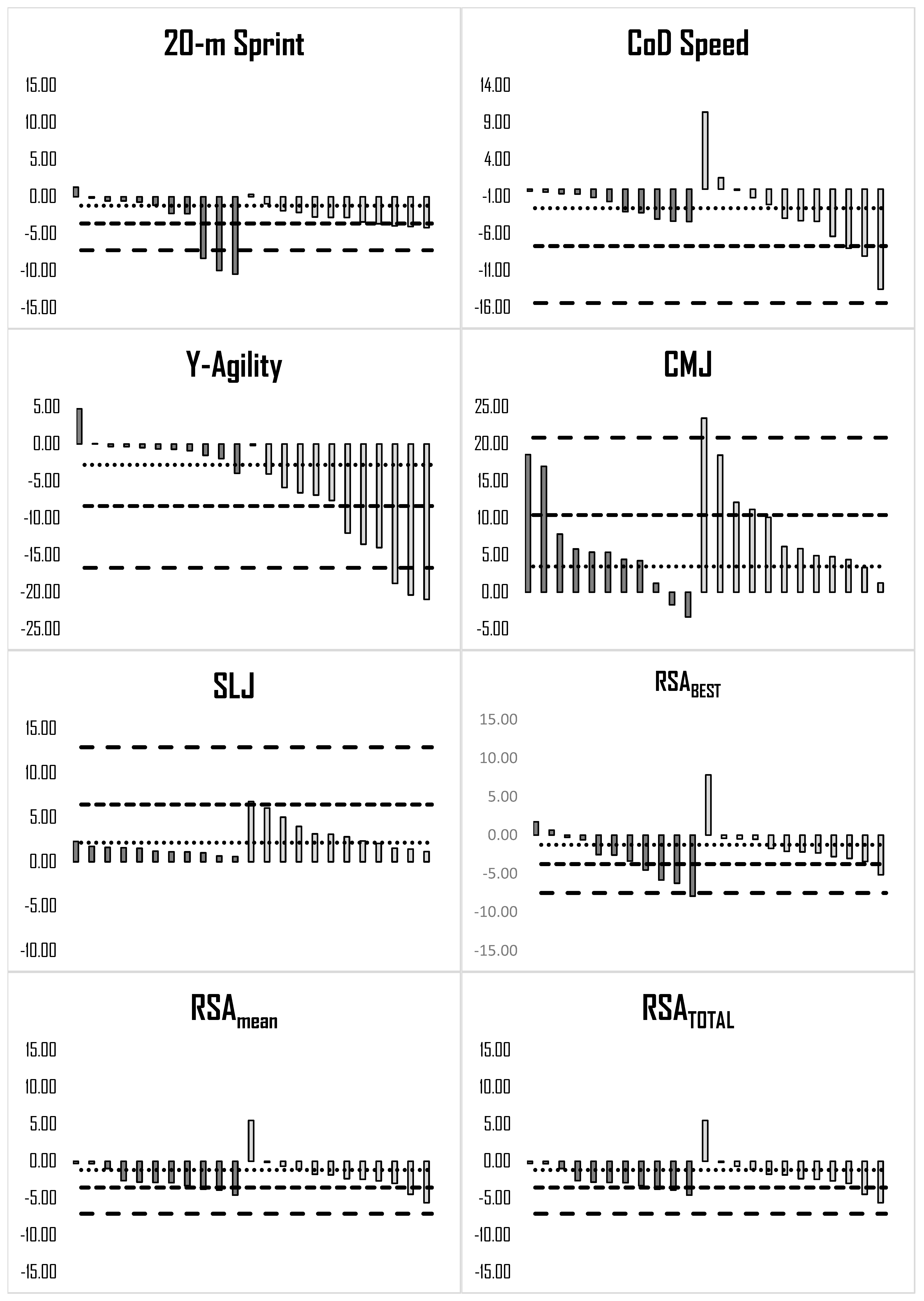

3.2. 505 Change of Direction

3.3. Y-Agility

3.4. Countermovement Jump

3.5. Standing Long Jump

3.6. Repeated Sprint Ability

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Y.; Liu, F.; Bao, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Gómez, M.Á. Key Anthropometric and Physical Determinants for Different Playing Positions During National Basketball Association Draft Combine Test. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Bishop, C. Influence of Maturation and Determinants of Repeated-Sprint Ability in Youth Basketball Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Ifrán, P.; Rial, M.; Brini, S.; Calleja-González, J.; Del Rosso, S.; Boullosa, D.; Benítez-Flores, S. Change of Direction Performance and its Physical Determinants Among Young Basketball Male Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 85, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino-Ortega, J.; Rojas-Valverde, D.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Rico-González, M. Training Design, Performance Analysis, and Talent Identification-A Systematic Review about the Most Relevant Variables through the Principal Component Analysis in Soccer, Basketball, and Rugby. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, D.G. Predicting success in junior elite basketball players—The contribution of anthropometric and physiological attributes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2000, 3, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Piñar, M.I.; García, D.; Mancha-Triguero, D. Physical Fitness as a Predictor of Performance during Competition in Professional Women’s Basketball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokou, E.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Apostolidis, N. Repeated sprinting ability in basketball players: A brief review of protocols, correlations and training interventions. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri, T.; Binetti, M.; Scanlan, A.T.; Dalbo, V.J.; Dolci, F.; Specos, C. Physical Determinants of Division 1 Collegiate Basketball, Women’s National Basketball League, and Women’s National Basketball Association Athletes: With Reference to Lower-Body Sidedness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, N.B.; El Fazaa, S.; El Ati, J. Time-motion analysis and physiological data of elite under-19-year-old basketball players during competition. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, D.; Favero, T.G.; Lupo, C.; Francioni, F.M.; Capranica, L.; Tessitore, A. Time-Motion Analysis of Italian Elite Women’s Basketball Games. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; Girard, O.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. Repeated-sprint ability—Part II: Recommendations for training. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granacher, U.; Puta, C.; Gabriel, H.W.; Behm, D.G.; Arampatzis, A. Editorial: Neuromuscular Training and Adaptations in Youth Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacot, A.; López-Ros, V.; Prats-Puig, A.; Escosa, J.; Barretina, J.; Calleja-González, J. Multidisciplinary Neuromuscular and Endurance Interventions on Youth Basketball Players: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.J.A.M.; Janeira, M.A.A.S. The Effects of Resistance Training on Explosive Strength Indicators in Adolescent Basketball Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Wierike, S.C.M.; de Jong, M.C.; Tromp, E.J.Y.; Vuijk, P.J.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M.; Malina, R.M.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Visscher, C. Development of Repeated Sprint Ability in Talented Youth Basketball Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-García, J.M.; Rodríguez-Rosell, D.; Mora-Custodio, R.; González-Badillo, J.J. Changes in Muscle Strength, Jump, and Sprint Performance in Young Elite Basketball Players: The Impact of Combined High-Speed Resistance Training and Plyometrics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Wang, X.; Hao, L.; Ran, X.W.; Wei, W. Meta-analysis of the effect of plyometric training on the athletic performance of youth basketball players. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1427291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.B. Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2006, 1, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, V. Spinal cord pattern generators for locomotion. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogkamer, W.; Meyns, P.; Duysens, J. Steps forward in understanding backward gait: From basic circuits to rehabilitation. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 42, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.; Eliakim, A.; Shalom, A.; Dello-lacono, A.; Meckel, Y. Improving anaerobic fitness in young basketball players: Plyometric vs. specific sprint training. J. Athl. Enhanc. 2014, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, P.G.; Pyne, D.B.; Minahan, C.L. The physical and physiological demands of basketball training and competition. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyes, F.R.; Barber-Westin, S.D.; Smith, S.T.; Campbell, T.; Garrison, T.T. A Training Program to Improve Neuromuscular and Performance Indices in Female High School Basketball Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnie, L.; Barratt, P.; Davids, K.; Stone, J.; Worsfold, P.; Wheat, J. Coaches’ philosophies on the transfer of strength training to elite sports performance. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 13, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthoff, A.; Oliver, J.; Cronin, J.; Harrison, C.; Winwood, P. A New Direction to Athletic Performance: Understanding the Acute and Longitudinal Responses to Backward Running. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthoff, A.; Oliver, J.; Cronin, J.; Harrison, C.; Winwood, P. Sprint-Specific Training in Youth: Backward Running vs. Forward Running Training on Speed and Power Measures in Adolescent Male Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguezzi, R.; Negra, Y.; Sammoud, S.; Uthoff, A.; Moran, J.; Behrens, M.; Chaabene, H. The Effects of Volume-Matched 1- and 2-Day Repeated Backward Sprint Training Formats on Physical Performance in Youth Male Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e587–e594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negra, Y.; Sammoud, S.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Bouguezzi, R.; Moran, J.; Chaabene, H. The effects of repeated sprint training with vs. without change of direction on measures of physical fitness in youth male soccer players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2022, 63, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sammoud, S.; Bouguezzi, R.; Uthoff, A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Moran, J.; Negra, Y.; Hachana, Y.; Chaabene, H. The effects of backward vs. forward running training on measures of physical fitness in young female handball players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1244369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagna, G.A.; Legramandi, M.A.; La Torre, A. Running backwards: Soft landing-hard takeoff, a less efficient rebound. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 2010, 278, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagna, G.A.; Legramandi, M.A.; La Torre, A. An analysis of the rebound of the body in backward human running. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasica, L.; Porcelli, S.; Minetti, A.E.; Pavei, G. Biomechanical and metabolic aspects of backward (and forward) running on uphill gradients: Another clue towards an almost inelastic rebound. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negra, Y.; Sammoud, S.; Uthoff, A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Moran, J.; Chaabene, H. The effects of repeated backward running training on measures of physical fitness in youth male soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 40, 2688–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; McKay, H.A.; Macdonald, H.; Nettlefold, L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Cameron, N.; Brasher, P.M.A. Enhancing a Somatic Maturity Prediction Model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Jeffriess, M.D.; McGann, T.S.; Callaghan, S.J.; Schultz, A.B. Planned and reactive agility performance in semiprofessional and amateur basketball players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Delhomel, G.; Brughelli, M.; Ahmaidi, S. Improving repeated sprint ability in young elite soccer players: Repeated shuttle sprints vs. explosive strength training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2715–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. The Analysis of Variance. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge Academic: London, UK, 1988; pp. 273–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G. Linear models and effect magnitudes for research, clinical and practical applications. Sportsscience 2010, 14, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chtara, M.; Rouissi, M.; Haddad, M.; Chtara, H.; Chaalali, A.; Owen, A.; Chamari, K. Specific physical trainability in elite young soccer players: Efficiency over 6 weeks’ in-season training. Biol. Sport 2017, 34, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.G.; Schultz, A.B.; Callaghan, S.J.; Jeffriess, M.D.; Berry, S.P. Reliability and validity of a new test of change-of-direction speed for field-based sports: The change-of-direction and acceleration test (CODAT). J. Sports Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh, S.; Arshi, A.R.; Davids, K. Quantifying coordination and coordination variability in backward versus forward running: Implications for control of motion. Gait Posture 2015, 42, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, S.J.; Poggensee, K.L.; Sánchez, N.; Simha, S.N.; Finley, J.M.; Collins, S.H.; Maxwell Donelan, J. General variability leads to specific adaptation toward optimal movement policies. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 2222–2232.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.W.; Soutas-Little, R.W. Mechanical power and muscle action during forward and backward running. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1993, 17, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Weyand, P.G. The application of ground force explains the energetic cost of running backward and forward. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikołajec, K.; Arede, J.; Gryko, K. Examining physical and technical performance among youth basketball national team development program players: A multidimensional approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVita, P.; Stribling, J. Lower extremity joint kinetics and energetics during backward running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthoff, A.; Oliver, J.; Cronin, J.; Winwood, P.; Harrison, C. Backward Running: The Why and How to Program for Better Athleticism. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Bishop, D. Repeated-Sprint Ability—Part I. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

SWC;

SWC;  MWC;

MWC;  LWC;

LWC;  RFST group;

RFST group;  RBST group.

RBST group.

SWC;

SWC;  MWC;

MWC;  LWC;

LWC;  RFST group;

RFST group;  RBST group.

RBST group.

| RFST Group (n = 11) | RBST Group (n = 12) | p Value | t de Student (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.36 ± 0.63 | 15.20 ± 0.54 | 0.513 | 0.66 (−0.34 to 0.67) |

| Body height (cm) | 177.36 ± 13.25 | 177.36 ± 11.02 | 0.992 | −0.01 (−10.58 to 10.47) |

| Body mass (kg) | 65.73 ± 13.98 | 62.42 ± 8.03 | 0.489 | −0.70 (−6.46 to 13.08) |

| Maturity offset (years) * | 1.86 ± 1.01 | 1.74 ± 0.68 | 0.743 | 0.33 (−0.62 to 0.85) |

| APHV | 13.50 ± 0.61 | 13.46 ± 0.64 | 0.879 | 0.15 (−0.49 to 0.57) |

| RFST Sets × Reps × Distance (m) (Per Session) | RBST Sets × Reps × Distance (m) (Per Session) | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 3 × 7 × 20 | 3 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 2 | 3 × 7 × 20 | 3 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 3 | 3 × 7 × 20 | 3 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 4 | 2 × 7 × 20 | 2 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 5 | 4 × 7 × 20 | 4 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 6 | 4 × 7 × 20 | 4 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 7 | 4 × 7 × 20 | 4 × 7 × 20 |

| Week 8 | 3 × 7 × 20 | 3 × 7 × 20 |

| Group | Pre (μ ± SD) | Post (μ ± SD) | Post-Pre % Difference (95% CL) | Post-Pre Training Effect Size | Difference RBST—RFST (μ ± SE) | RBST—RFST Effect Size (95% CL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 m sprint (s) | RBST RFST | 1.17 ± 0.07 1.20 ± 0.07 | 1.10 ± 0.07 * 1.15 ± 0.06 | −5.32 (−9.50 to −1.14) −4.58 (−5.92 to −3.23) | 1.05 0.80 | −0.01 ± 0.03 | −0.10 (−0.92 to 0.72) |

| 10 m sprint (s) | RBST RFST | 1.93 ± 0.08 2.03 ± 0.11 | 1.86 ± 0.07 ◊ 1.96 ± 0.12 ◊ | −3.53 (−4.89 to −2.17) −3.24 (−5.16 to −1.31) | 0.98 −0.64 | 0.00 ± 0.02 | −0.02 (−0.84 to 0.79) |

| 20 m sprint (s) | RBST RFST | 3.35 ± 0.16 3.49 ± 0.28 | 3.22 ± 0.14 ◊ 3.38 ± 0.23 | −3.98 (−6.02 to −1.94) −3.27 (−5.78 to −0.77) | 0.89 0.50 | −0.02 ± 0.06 | −0.10 (−0.92 to 0.72) |

| 505 CoD (s) | RBST RFST | 2.60 ± 0.32 2.78 ± 0.36 | 2.43 ± 0.25 * 2.72 ± 0.35 | −6.48 (−11.46 to −1.50) −2.18 (−3.16 to −1.20) | 0.62 0.18 | −0.11 ± 0.96 | −0.32 (−1.14 to 0.51) B |

| Y-Agility (s) | RBST RFST | 1.83 ± 0.22 1.63 ± 0.23 | 1.58 ± 0.17 † 1.62 ± 0.22 | −13.27 (−18.03 to −8.52) −0.68 (−1.91 to 0.55) | 1.33 0.05 | −0.23 ± 0.05 ◊ | −1.03 (−1.90 to −0.16) B |

| CMJ (m) | RBST RFST | 0.33 ± 0.05 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.06 * 0.30 ± 0.06 | 6.11 (1.81 to 10.39) 6.25 (2.24 to 10.39) | −0.34 −0.39 | 0.00 ± 0.08 | 0.05 (−0.77 to 0.87) |

| SLJ (cm) | RBST RFST | 2.02 ± 0.17 1.83 ± 0.21 | 2.07 ± 0.18 † 1.86 ± 0.22 * | 2.69 (1.72 to 3.65) 1.34 (2.04 to 1.63) | −0.12 −0.32 | 0.03 ± 0.08 * | 0.16 (−0.66 to 0.98) B |

| RSAbest (s) | RBST RFST | 7.70 ± 0.33 8.15 ± 0.55 | 7.57 ± 0.29 7.92 ± 0.53 * | −1.74 (−3.70 to 0.22) −2.91 (−4.72 to −1.09) | 0.44 0.45 | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 0.23 (−0.59 to 1.05) F |

| RSAmean (s) | RBST RFST | 7.99 ± 0.32 8.48 ± 0.52 | 7.82 ± 0.25 * 8.26 ± 0.53 ◊ | −2.16 (−3.92 to −0.39) −2.58 (−3.43 to −1.73) | 0.62 0.43 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.11 (−0.71 to 0.93) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arbi, G.; Negra, Y.; Uthoff, A.; Sammoud, S.; Müller, P.; Chaabene, H.; Hachana, Y. Effects of Repeated Forward Versus Repeated Backward Sprint Training on Physical Fitness Measures in Youth Male Basketball Players. Sports 2026, 14, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010016

Arbi G, Negra Y, Uthoff A, Sammoud S, Müller P, Chaabene H, Hachana Y. Effects of Repeated Forward Versus Repeated Backward Sprint Training on Physical Fitness Measures in Youth Male Basketball Players. Sports. 2026; 14(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleArbi, Ghofrane, Yassine Negra, Aaron Uthoff, Senda Sammoud, Patrick Müller, Helmi Chaabene, and Younes Hachana. 2026. "Effects of Repeated Forward Versus Repeated Backward Sprint Training on Physical Fitness Measures in Youth Male Basketball Players" Sports 14, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010016

APA StyleArbi, G., Negra, Y., Uthoff, A., Sammoud, S., Müller, P., Chaabene, H., & Hachana, Y. (2026). Effects of Repeated Forward Versus Repeated Backward Sprint Training on Physical Fitness Measures in Youth Male Basketball Players. Sports, 14(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010016