1. Introduction

In recent years, global and national health authorities have intensified their efforts to promote sports participation for health benefits [

1,

2,

3]. Despite these initiatives, however, the rates of unhealthy or unsuccessful aging continue to climb [

4,

5]. This trend is significantly influenced by technological advancements and the increasing prevalence of sedentary lifestyles.

Understanding the role of sports participation in promoting healthier aging has become increasingly significant. Aging is a lifelong process that commences at birth and is characterized by physical, emotional, and mental regression. This process encompasses the period during which the human lifespan approaches completion, vital functions progressively decline, and the quality of life diminishes over time. Successful aging is defined as the process of developing and maintaining functional abilities that enable older individuals to perform tasks of personal importance, despite unforeseen medical conditions and accidents, while preserving independence, vitality, and quality of life [

1,

6].

According to the literature, several factors of human life can contribute to successful aging, such as physiological, psychological, and social domains [

7], as well as additional lifestyle factors [

8]. According to the framework by Rowe and Kahn [

9,

10], successful aging is defined by three key criteria: (1) avoiding disease and disability; (2) maintaining high cognitive and physical function; (3) sustaining meaningful engagement with life.

To age successfully, individuals should develop regular physical activity and exercise habits early in life, as these form the foundation for successful aging in both the short and long term [

11,

12]. It has been reported that regular exercise enhances insulin sensitivity and offers protective benefits for lipid metabolism [

13]. Notably, endurance exercises help maintain vascular function in older age and reduce mortality [

14,

15,

16]. Recent research indicates that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is another effective method for preventing coronary heart disease, boosting cardiorespiratory fitness, and improving the cardiovascular risk profile in older adults [

17].

Tennis is a widely enjoyed sport that attracts players of all ages worldwide. Its widespread appeal is bolstered by the Masters Tour system, which organizes tournaments from MT100 to MT1000 across diverse age groups at the international level [

18]. As a multifaceted sport, tennis offers players physical, mental, and psychological benefits. The game’s structure, marked by short, high-intensity rallies and brief recovery periods, boosts both aerobic and anaerobic endurance [

19]. Additionally, playing tennis demands a mental framework that fosters strategic thinking, concentration, and stress-management skills [

20]. Long-term and regular engagement in tennis has been shown in the literature to promote healthy living and even extend life expectancy [

21,

22]. An epidemiological study involving 8577 individuals tracked over 25 years found that tennis players lived an average of 9.7 years longer than sedentary individuals [

23]. These benefits are attributed to the blend of aerobic, strength, balance, and flexibility components of the sport, which help mitigate the risk of falls, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and cognitive decline [

21,

22]. These effects are believed to stem from the multifaceted nature of tennis, which simultaneously supports the physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains associated with successful aging [

10].

Masters tennis players are known to participate in training and matches of this multifaceted nature during their leisure time [

18]. Leisure time involvement is characterized by factors such as “centrality,” “identity expression,” and “attraction” [

24], as well as “social bonding” and “identity affirmation” [

25]. Kyle et al. [

25,

26] explained these factors as follows: Attraction refers to the perceived interest in an activity and the pleasure derived from participation [

25,

26]. Centrality examines the centrality of an activity in an individual’s life. Social bonding refers to the social ties that provide attachment to activities. Identity affirmation provides opportunities for self-affirmation through engaging in leisure activities. Identity expression provides opportunities for individuals to express themselves through leisure activities [

24,

25,

26].

Considering this conceptual framework, tennis involvement (attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, and identity expression) is thought to be directly related to the components of Reker’s [

27] successful aging model. The attraction (hedonic value) and importance of tennis motivate individuals to maintain a healthy lifestyle by engaging in regular physical activity [

28]. The social relationships inherently fostered by tennis create a strong social support network, providing a critical psychological resource for tackling the challenges of aging [

17,

29]. Deep identification with tennis and its use as a means of expression (identity expression) provides individuals with a meaningful identity and life purpose well into later life; this is directly linked to personal growth and life satisfaction, which are the cornerstones of successful aging [

19,

20].

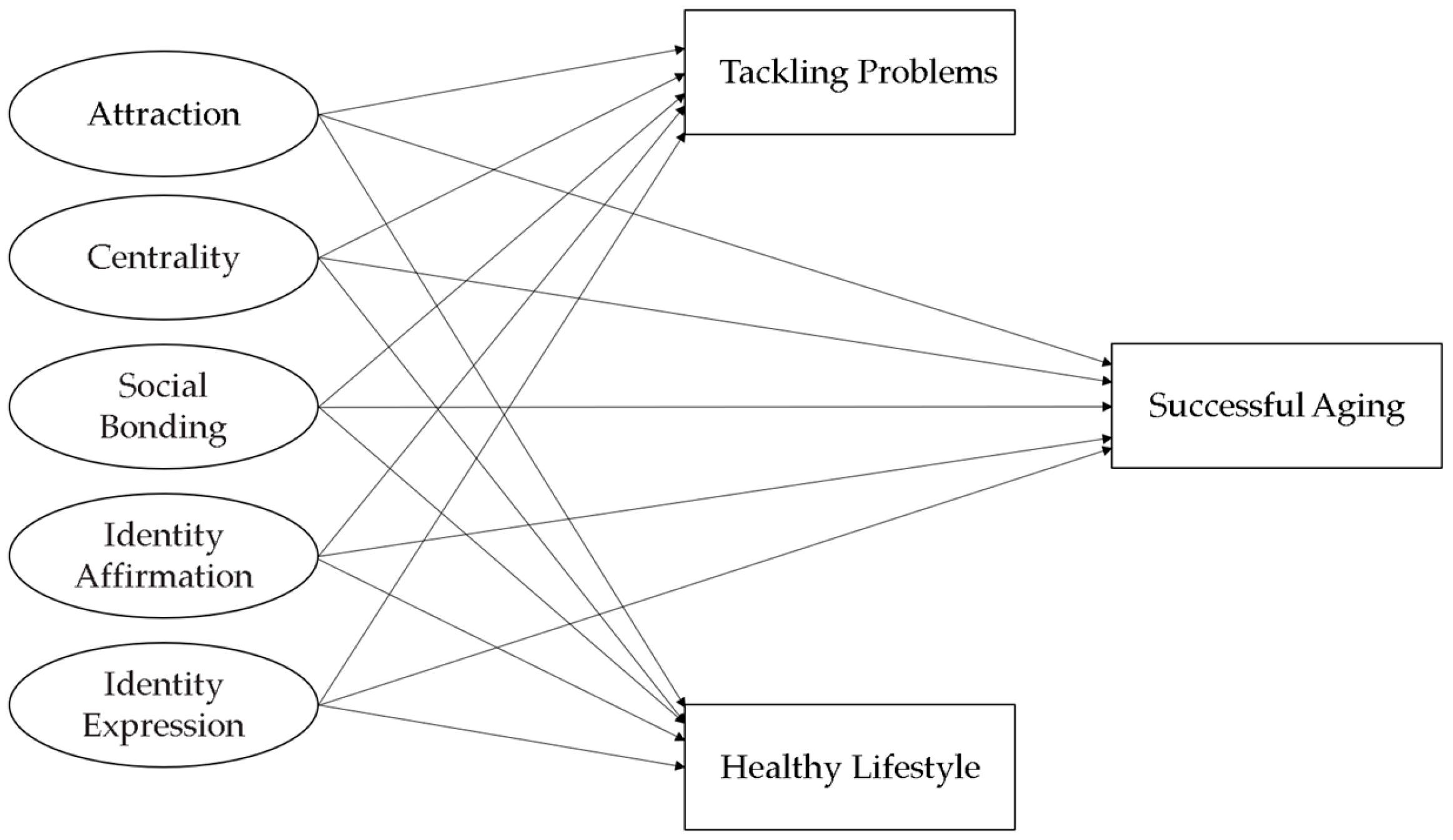

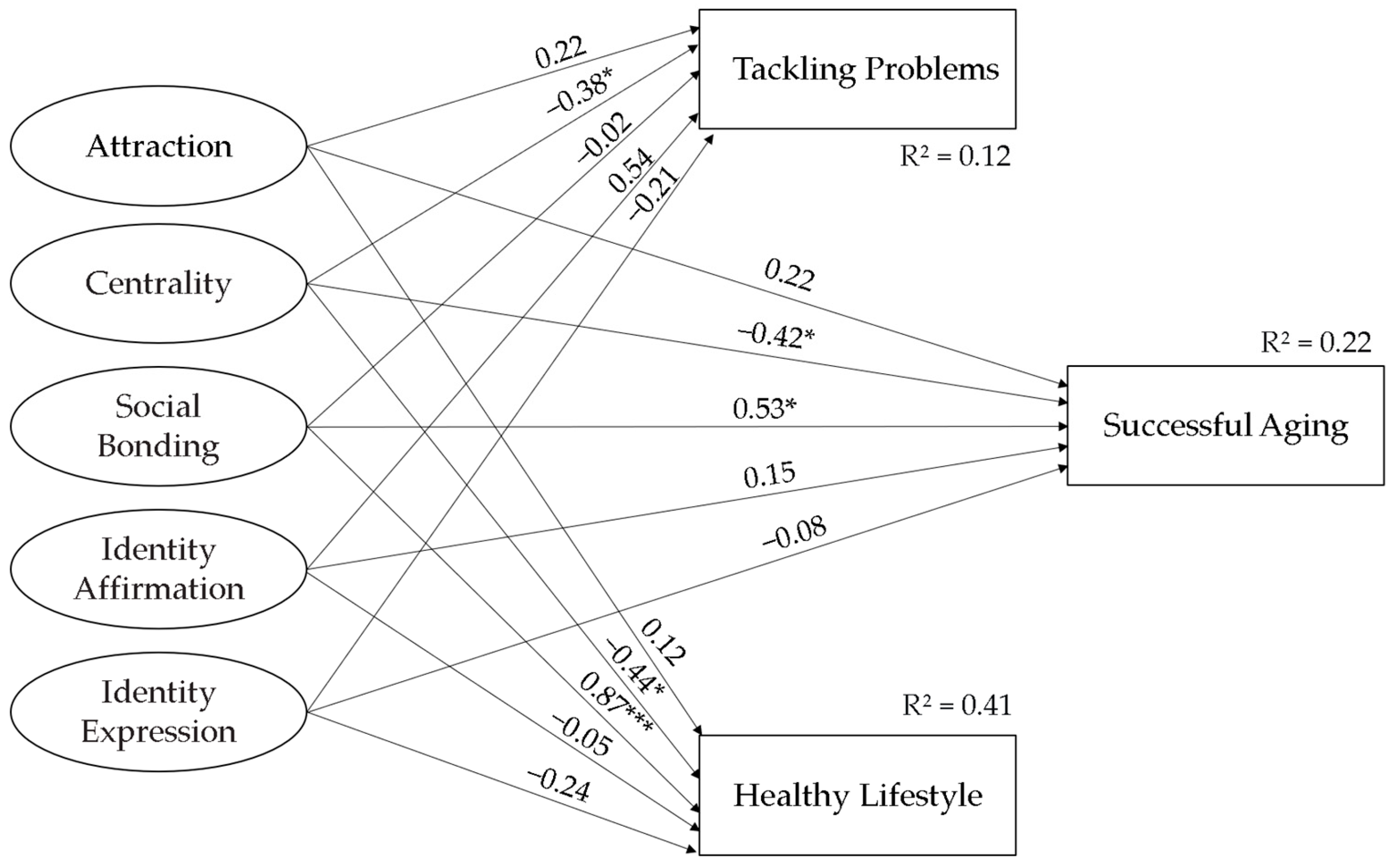

In recent years, it has become evident that many individuals are focusing on various activities and lifestyle changes to enhance their quality of life and achieve a longer, healthier existence. This study aims to illuminate academic research on masters tennis players aged 40 and above, contributing to sports literature by examining health, psychological, and social relationships collectively. Consequently, this study explores the connection between tennis involvement and successful aging, with a particular focus on how regular tennis participation and competitive tournament engagement contribute to key aspects of successful aging. Based on this premise, we developed a model to investigate the relationship between tennis involvement and successful aging, as outlined in the theoretical framework presented above (

Figure 1). In this context, the following hypotheses were formulated to test the model.

H1a. There are significant and positive relationships between attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, and identity expression and successful aging.

H1b. There are significant and positive relationships between attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, and identity expression and tackling problems.

H1c. There are significant and positive relationships between attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, and identity expression and a healthy lifestyle.

H2. There are significant correlations between the participants’ age, weekly training days and hours, and tennis involvement/subscales and successful aging/subscales.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

In Türkiye, the Turkish Tennis Federation organizes official Masters Tennis competitions. Athletes must possess a valid license to participate in these tournaments. However, holding a license does not necessarily indicate that the individual is an active tennis player. Each player creates their own tournament schedule based on their personal plans. Tournaments are hosted by clubs across various provinces that meet the federation’s standards. Athletes compete in events such as the T200, T400, T500, Turkish Individual Masters Championship, and Team Championship. Since tennis is an individual sport, reaching many masters tennis players can be quite challenging. In this study, data was collected from athletes participating in masters tennis tournaments across different provinces in 2024.

The study group consisted of masters players who participated in tournaments during their leisure time, in alignment with the research purpose. Participants were interviewed individually, face-to-face, and the study’s purpose was explained within a tournament setting. Volunteer tennis players were informed about data security measures and asked to read and consent to the “informed consent form.” Instructions for completing the data collection tools were then provided, and the dataset (survey forms and pens) was distributed. The forms were anonymous, and participants could stop completing the survey at any time. Participants did not receive financial compensation for participating in the survey. Completing the scale forms took an average of 5–10 min. The researchers addressed the participants’ questions throughout the data collection period. Forms with larger font sizes were prepared for athletes experiencing vision problems at older ages and were used if necessary. Due to the difficulty in reaching the sample, incomplete or incorrect forms were identified immediately, and participants were asked to correct them, but no pressure was imposed.

Efforts were made to ensure representativeness across age groups (e.g., 40+, 45+, 50+) and gender. However, due to the significantly lower number of participants in older age groups and among female masters players, as was the case nationwide, these criteria were not adequately met. Individuals with disabilities were not included in the study. The study group comprised licensed athletes who regularly played tennis and participated in masters tournaments. The vast majority of participants are highly educated (91% university and postgraduate graduates), and the sample is more male than female (male: 68%, female: 32%). These characteristics suggest that the sample represents a non-random and hard-to-reach subgroup (individuals participating in masters tennis tournaments with high socioeconomic and cultural resources) (

Table 1). Therefore, when interpreting the results, it is essential to consider that the relationships between successful aging and tennis involvement may be influenced by factors such as education and socioeconomic status, and that the results cannot be directly generalized to a broader and more heterogeneous elderly population. This study focuses on a specific, high-functioning group to examine the proactive processes of successful aging.

The project was approved by the Ethics Sub-Committee of Afyon Kocatepe University (date: 20 December 2023; meeting number: 18; decision no: 2023/388).

2.2. Instruments

The “Personal Information Form,” crafted by the researchers, outlined the personal and tennis-related characteristics of the participants. It includes sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, total tennis days, hours played per week, and the city where tennis is played.

2.2.1. The Modified Involvement Scale (MIS)

The MIS, developed by Kyle et al. [

25], was translated into Turkish as the “Leisure Involvement Scale” (LIS) by Gurbuz et al. [

30], who also conducted validity and reliability studies. This scale assesses the level of involvement in leisure activities. For this study, the adaptable items from the scale were tailored for tennis and utilized as the “Tennis Involvement Scale.” For example, “A1 ______ is one of the most enjoyable things I do” was changed to “A1 Tennis is one of the most enjoyable things I do”. The scale is a 5-point Likert-type scale consisting of 15 items and five subscales. The subscales consist of the factors “attraction”, “centrality”, “social bonding”, “identity affirmation”, and “identity expression”. Each factor consisted of three items.

2.2.2. The Successful Aging Scale (SAS)

The SAS was developed by Reker [

27]. The original scale consisted of three subfactors and 14 items related to “healthy lifestyle,” “adaptive coping,” and “engagement with life” related to successful aging. In the study by Hazer and Özsungur [

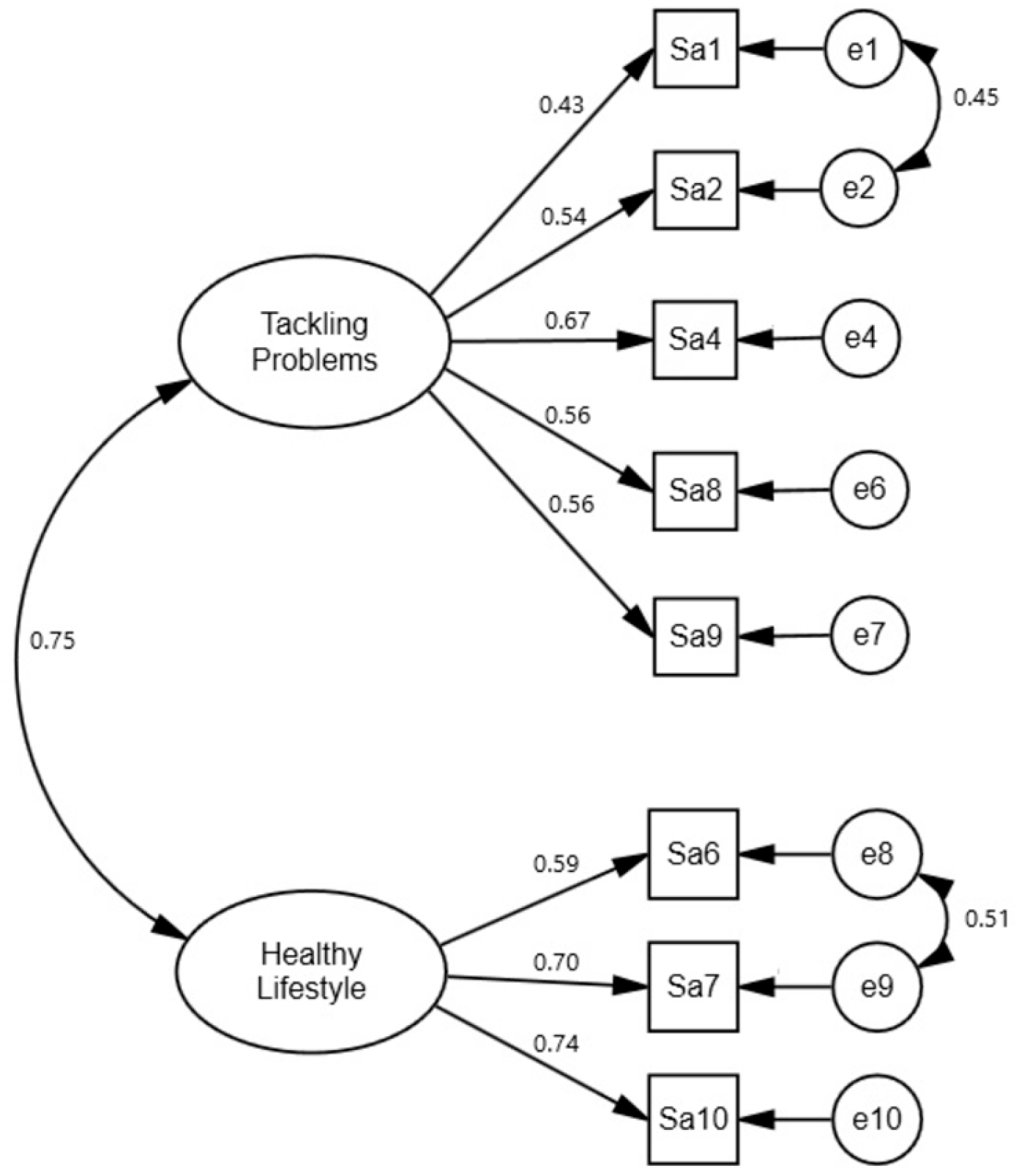

31], the scale, adapted to Turkish culture, underwent structural modifications, with non-functional items removed based on validity and reliability analyses. This scale is a 7-point Likert-type, comprising 10 items divided into two subscales: “tackling problems” and “healthy lifestyle.” The “tackling problems” subscale includes seven items, while the “healthy lifestyle” subscale contains three items.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data collected from the participants was scrutinized, with any missing or incorrect entries being removed and processed for analysis. Out of the 245 survey responses, 26 were excluded from the analysis because they either did not align with the study group characteristics or were filled out incompletely or incorrectly. Descriptive statistics were conducted to highlight the fundamental characteristics of masters tennis players (

Table 1). The normal distribution of the data was assessed using skewness-kurtosis coefficients, scatter diagrams, and Mahalanobis distances, and the mean and standard deviations of the scores were calculated.

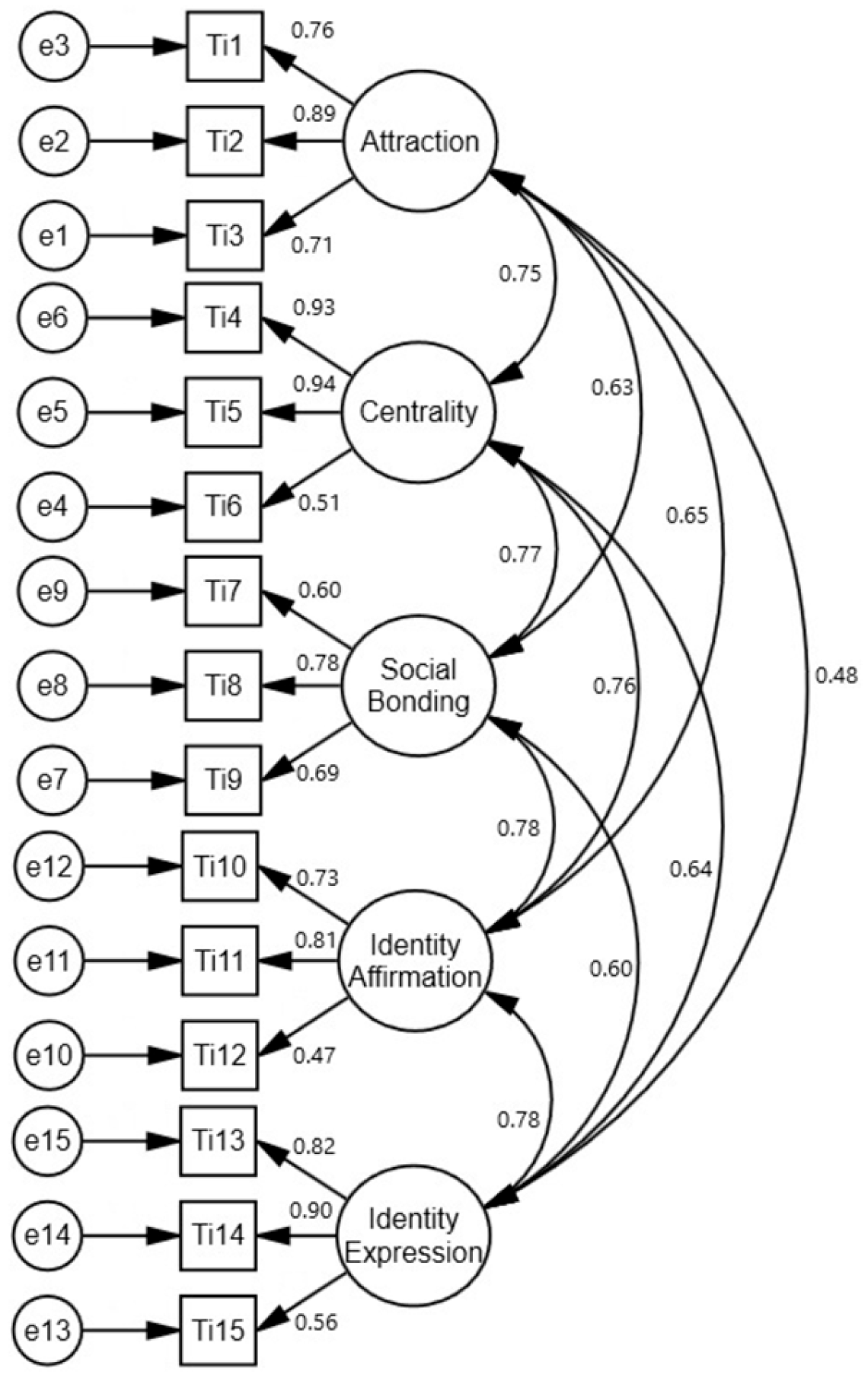

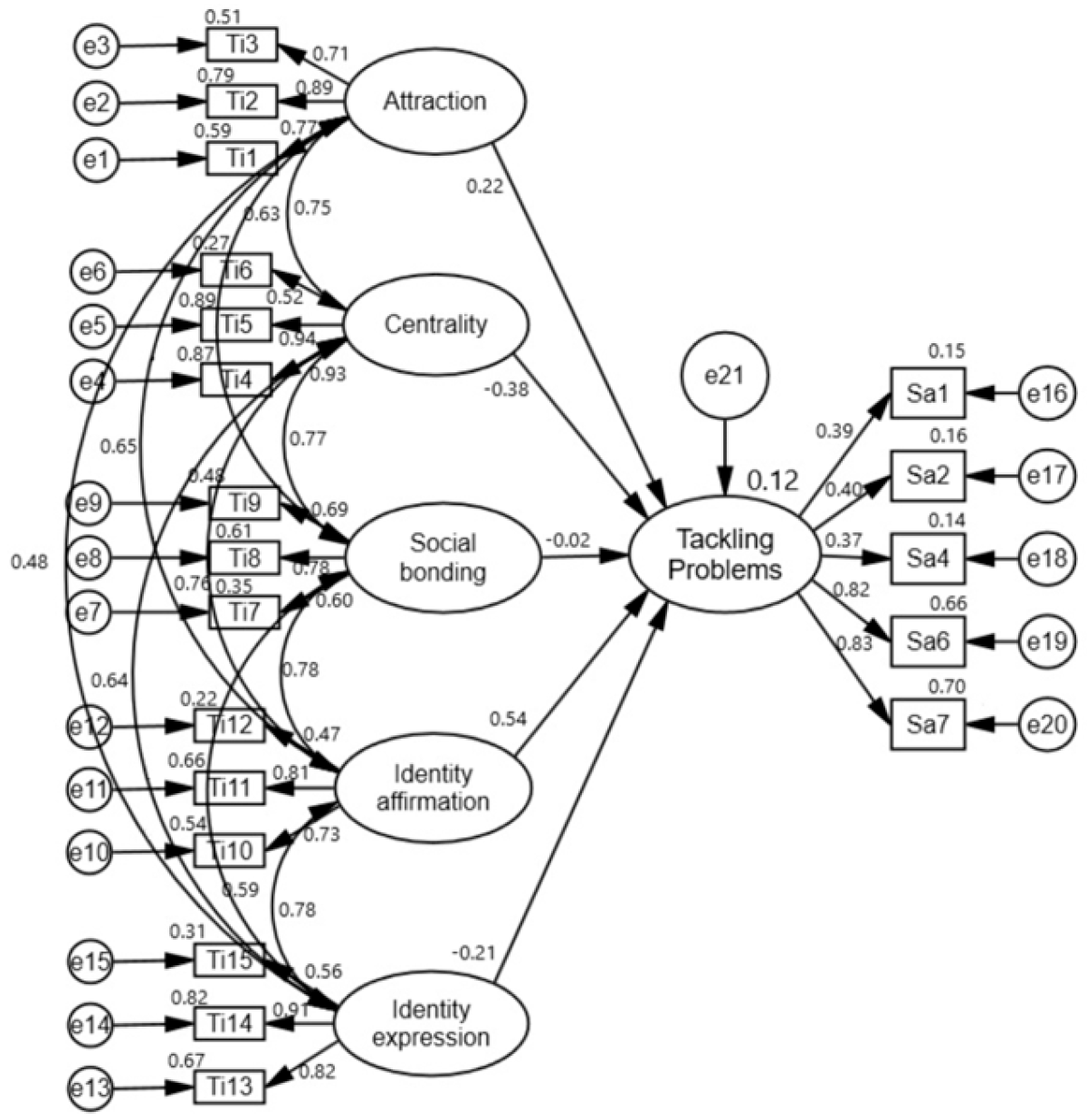

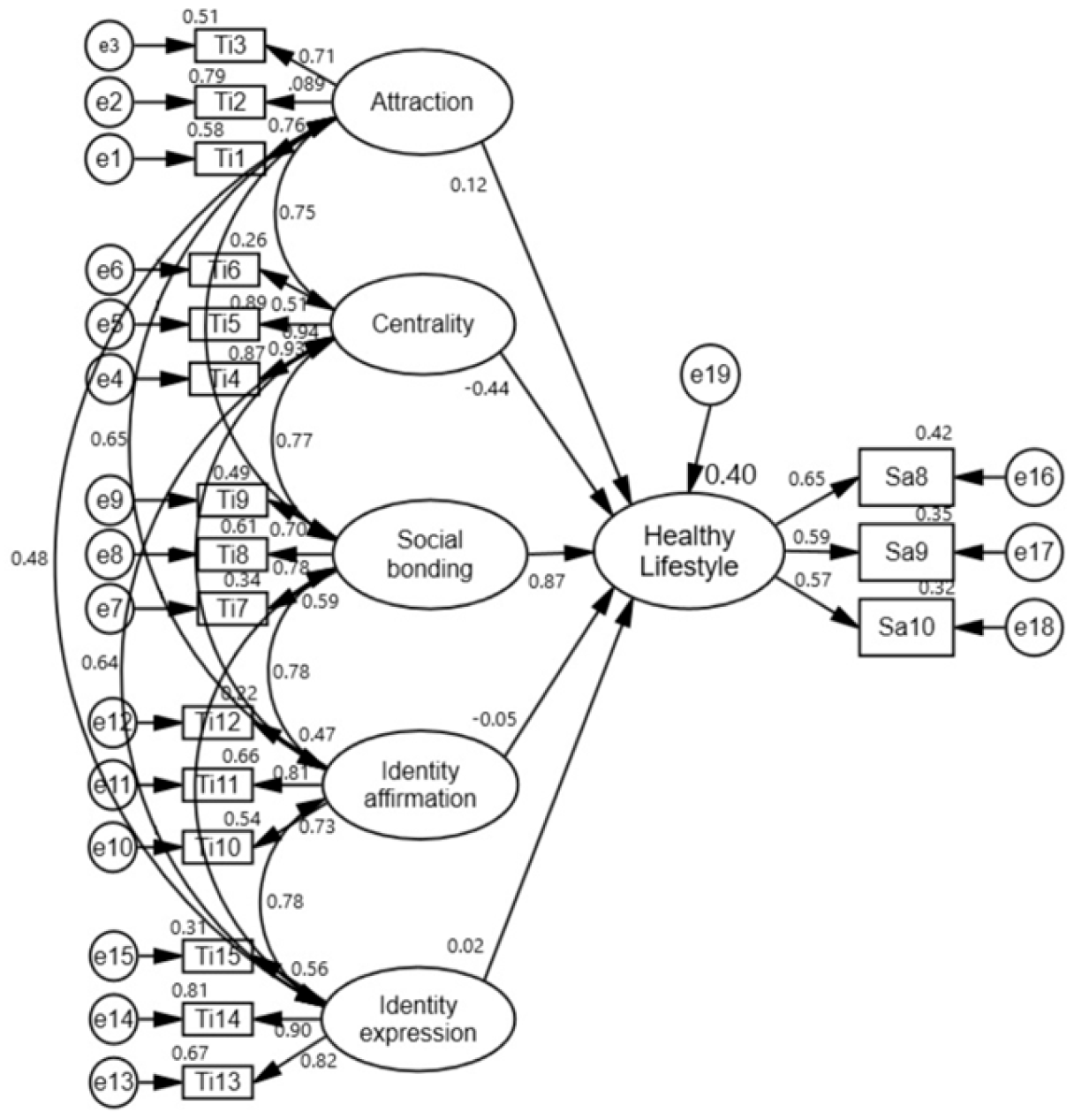

Assuming that the scales would be applied to masters tennis players for the first time, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm that tennis involvement and successful aging are valid and reliable instruments for Turkish masters tennis players, and the goodness-of-fit values were determined. Additionally, Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) values were calculated for construct reliability, while factor loading values and Average Variance Explained (AVE) values were determined for convergent validity using CFA. For the new DFA model of scales that differed in structure from the original scale, the existing data was randomly divided in SPSS using split-half cross-validation (80–20%). A k-fold cross-validation analysis was conducted for both the exploration phase (80%) and the validation phase (20%).

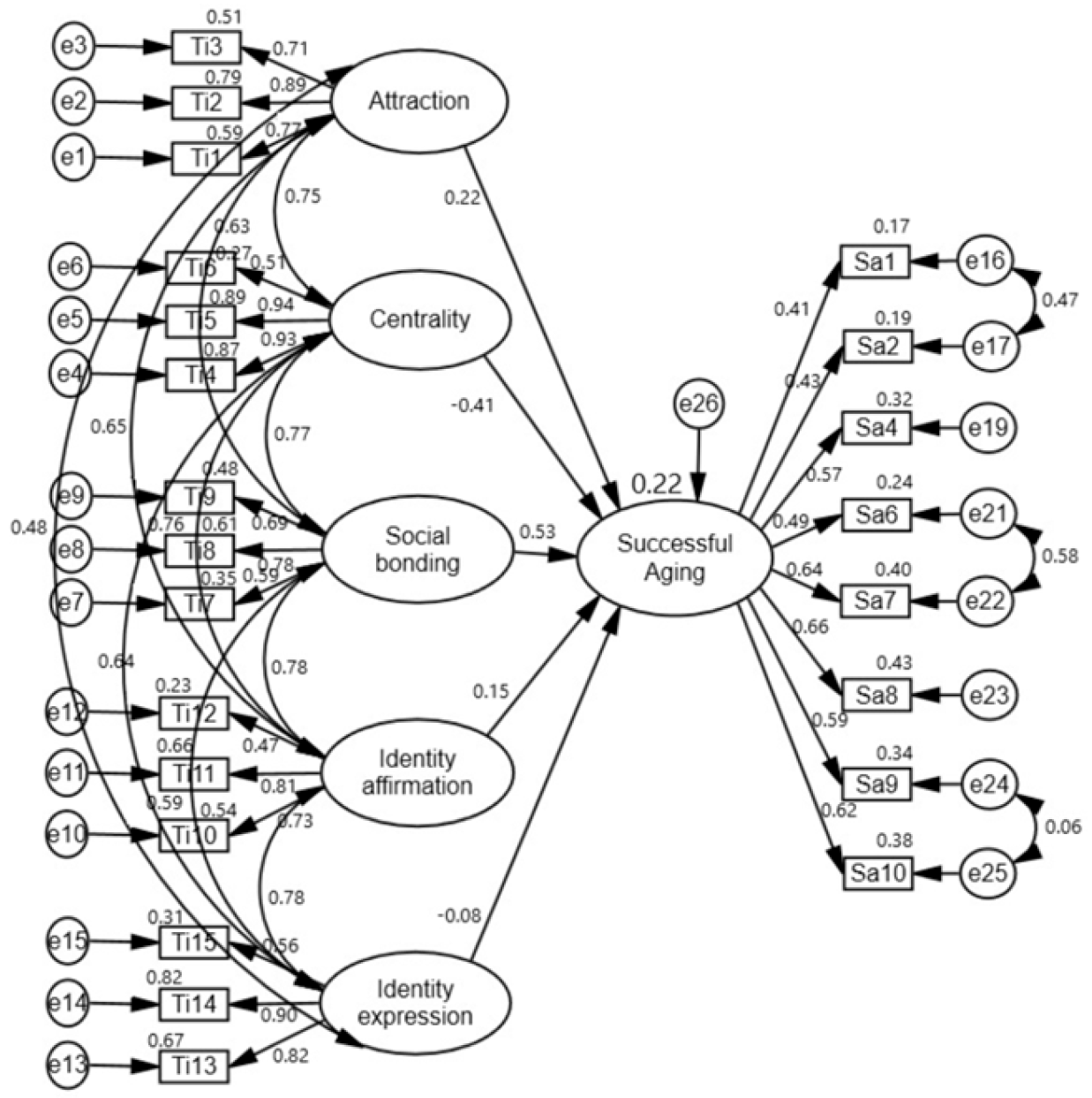

The causal relationships (H1a, H1b, H1c) between observed and latent variables were tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Pearson’s Correlation analysis was performed to determine the relationships between the variables (age, TTD, and TTH) and scale scores (H2). During the analysis, we calculated the effect size (Cohen’s d, r2) indicator for the given cases. In the statistical analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 31 was used for descriptive statistics and correlation analyses, and AMOS 22 was used for CFA and SEM analyses to test the hypotheses.

4. Discussion

This study developed and tested theoretically grounded models to examine associations between tennis involvement and orientations toward successful aging among masters tennis players. The sample, with an average age of approximately 51 years, represents middle-aged regular tennis players who differ from older adult populations typically studied in aging research. Successful aging is conceptualized here as a proactive developmental process, in which individuals adopt behavioral, psychological, and social strategies that may support well-being in later life. It is important to note that the Successful Aging Scale (SAS) in this study assesses predispositions and orientations toward successful aging, rather than measuring actual aging outcomes.

Although prior research has consistently shown that physical activity benefits health and supports successful aging [

16,

36], little is known about how variations in tennis involvement—such as frequency of play, competition participation, age, and gender—relate to successful aging strategies among masters players. By addressing this gap, the present findings advance understanding of tennis involvement as a meaningful construct and provide insight into its relevance for middle-aged athletes within a developmental perspective on successful aging.

A model was developed to examine the relationships between the subfactors of tennis participation and the components of successful aging. Because the measurement tools were applied to masters tennis players for the first time, CFA was performed on the scales for this research group. Although the structure of the Tennis Involvement Scale was found to be the same as the original scale (LIS), the original structure was not formed for the Successful Aging Scale. As a result of the analyses, the structure of the Successful Aging Scale changed. Therefore, the 8-item scale presented in this study should be considered not as a universal revision of the original Successful Aging Scale, but as a culturally and psychometrically adapted and modified version for use in a specific population (masters tennis players in Türkiye). The removal of items is related to statistical necessities as well as the fact that the “tackling problems” construct is represented in a narrower and more action-oriented way (e.g., active struggle) in this sample. Conceptually, “tackling problems” is intended to assess an individual’s active coping strategies and psychological resilience when faced with challenges. Item 3 (I maintain warm and trusting relations with significant others), which was removed from the scale, identifies a coping resource. However, unlike the other items, it does not directly refer to a coping action or mindset, such as persistence, resilience, or the ability to cope. Similarly, item 5 (I strive to remain independent for as long as possible), which was removed from the scale, while expressing a goal or intention, does not directly reflect the current coping competence, which is the focus of this dimension. Consequently, it aligns less closely with the factor structure. The fact that the removed items (“maintaining close relationships” and “striving to remain independent”) report more of a resource or intention, while the other items emphasize a direct coping action, has served to make this subfactor more consistent while preserving its essence. Thus, the resulting instrument is a measurement tool that continues to measure the core components of successful aging but has been developed with an exploratory approach and optimized for fit to the existing data.

Hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c predicted that all five dimensions of tennis participation (attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, identity expression) would be positively associated with successful aging and its subfactors. SEM analyses provided very limited and partial support for these hypotheses. The hypotheses were supported only by the Social Bonding factor: Social Bonding showed strong positive associations with Successful Aging and Healthy Lifestyle. In contrast, the centrality factor, contrary to expectations, showed consistently significant negative associations with Successful Aging, Tackling Problems, and Healthy Lifestyle. The relationships between the other factors (attraction, identity affirmation, identity expression) were not found to be significant. These results suggest that the hypotheses require significant revision. In summary, the analysis of the model partially confirmed H1a and H1c, while H1b was rejected.

The positive association between social bonding and successful aging strategies highlights the importance of social support and belonging for individuals around 51 years of age [

37], aligning with previous results on the role of social relationships in promoting healthy aging [

38,

39,

40]. Tennis clubs and doubles play may facilitate social network maintenance and engagement during midlife transitions.

Conversely, the negative correlation with centrality should be interpreted cautiously as an observed association rather than a causal effect. Excessive focus on tennis may be related to interference with other life roles and potential increases in competitive stress [

41], but this interpretation remains a theoretical hypothesis rather than a demonstrated mechanism. Alternative explanations, such as identity foreclosure or competitive pressure, may also account for these associations. Although high centrality could theoretically align with the Role Overload Theory or U-shaped activity models [

41,

42,

43,

44], these models were not directly tested in this study, and no direct measures of stress, burnout, or injury [

20,

28,

45,

46,

47] were included; therefore, implications regarding training volume or excessive involvement should not be overstated. These results also provide a nuanced view in relation to the Serious Leisure Perspective [

48], indicating that strong commitment to tennis may, under certain midlife conditions, transition from supporting identity and mastery to becoming a burdensome role.

Regarding other outcomes, the tennis involvement subfactors “attraction,” “identity affirmation,” and “identity expression” did not show significant associations with successful aging strategies among masters players. Given that participants were over 40 years old with high socioeconomic, educational, and professional status, identity-related experiences may be shaped by broader life factors beyond tennis. Additionally, as active competitors with national and ITF-level goals, these athletes may already engage in behaviors consistent with successful aging orientations, limiting the observable effects of tennis involvement. Future research could further explore these assumptions. Overall, the results suggest that promoting tennis as a social and recreational activity, rather than as a central life focus, may be most supportive of successful aging strategies during midlife.

According to the research results, no correlation was found between age and tennis involvement or successful aging strategies. Although no significant correlation was observed, positive associations emerged between weekly tennis training (both days and hours) and successful aging strategies, indicating that regular participation supports proactive orientations and behavioral strategies relevant to midlife development. These results align with literature emphasizing that regular exercise behavior, particularly in middle-aged populations, is strongly associated with intrinsic motivation (e.g., enjoyment, social connection) and behavioral intention [

49]. Furthermore, the adaptable nature of tennis as a recreational sport may account for the minimal impact of chronological age, allowing participants to adjust intensity and style to align with physical capabilities, consistent with Dionigi’s “sport for life” concept [

50].

Positive and significant correlations were also observed between weekly tennis training duration, frequency, tennis involvement, and multidimensional successful aging strategies, consistent with evidence that regular exercise benefits physical and psychosocial resources in midlife [

15,

45]. Tennis involvement may provide a structured and meaningful routine that fosters autonomy, purpose, and competence—central psychological components of successful aging orientations. Its organized nature, including goal setting, social interaction, and skill development, supports persistence and enjoyment, reinforcing the adoption of proactive strategies.

Tennis involvement was positively associated with multiple dimensions of successful aging strategies in middle-aged adults (~51 years), reinforcing the view that successful aging is a proactive, lifelong process [

51]. Midlife participation may enhance bone density, physical fitness, cognitive engagement, and social networks, building a “biopsychosocial reserve” that can support adaptive strategies later in life [

52,

53]. These results underscore the value of promoting tennis as a balanced, socially embedded activity that facilitates proactive orientations toward successful aging.

5. Limitations and Strengths

The study’s limitations, particularly in terms of its measurement tools, necessitate caution when interpreting the results. First, the size of the validation subsample is below ideal, which may limit the statistical power of the CFA results. Second, the CR and AVE values obtained for some subscales, which are at or below the recommended thresholds, may indicate that further improvement of the measurement is needed for these constructs. Therefore, claims regarding the construct validity of the scale should be treated cautiously. Finally, the validity and reliability of the scale were tested only with the sample of this study. Future studies are recommended to test this revised form in different and larger samples, to examine test–retest reliability, and to ensure criterion validity (e.g., its relationship with variables such as life satisfaction and depression).

Another limitation of the study is the occurrence of sampling bias. A random and homogeneous sample was used. The sample consisted almost entirely of highly educated individuals, predominantly male, who regularly played tennis and participated in tournaments. These demographic characteristics differ significantly from the profile of the general middle-aged and older population in Türkiye. This creates a selection bias and limits the generalizability of the results to groups with lower levels of education, individuals who do not play tennis, or females. The obtained relationships may also be partly influenced by the resources available to this high-functioning group (time, finances, health awareness).

This study makes several important contributions and presents methodological challenges to existing literature. First, it is one of the pioneering studies examining the concept of successful aging as a proactive process in middle-aged adults (average ~51 years) within the context of physical activity (tennis). This offers a new perspective that treats aging not as a period of ‘loss’ but as a process that can be shaped by active participation.

Second, data were collected from a challenging and unique sample (active masters tennis tournament players), and psychometric properties specific to this group were rigorously assessed through retesting and adaptation of the scales (TIS and SAS). A third strength is the simultaneous testing of complex and direct relationships between the multidimensional nature of tennis involvement and the subcomponents of successful aging, using SEM to examine these relationships.

The most notable result is that the social bonding factor of tennis has the most consistent and strong positive association with successful aging. This is a critical insight into how the benefits of physical activity in middle and old age may stem primarily from psychosocial mechanisms (belonging, social support), rather than purely physiological ones. Furthermore, the unexpected negative correlations of the centrality factor offer a significant practical implication: ‘balance’ and ‘flexibility’ in activity participation may be more harmonious than ‘rigid commitment’. Ultimately, this study repositions tennis not merely as an exercise, but as a meaningful context supporting biopsychosocial health in later life stages.