Reliability of the Output Sports Inertial Measurement Unit in Measuring a Reactive Strength Index from the Drop Jump and 10-5 Rebound Jump Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSC | Stretch-shortening cycle |

| GCT | Ground contact time |

| RSI | Reactive strength index |

| JH | Jump height |

| DJ | Drop Jump |

| 10-5 RJT | 10-5 rebound jump test |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| SWC | Smallest worthwhile change |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| PAR-Q | Physical activity readiness questionnaire |

| TE | Typical error |

References

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Stone, M.H. The importance of muscular strength in athletic performance. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1419–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W. Laboratory strength assessment of athletes. New Stud. Athl. 1995, 10, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Komi, P.V.; Nicol, C. Stretch-shortening cycle of muscle function. In Biomechanics in Sport: Performance Enhancement and Injury Prevention; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtbleicher, D. Training for power events. Strength Power Sport 1992, 1, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Kutz, M.R. Theoretical and practical issues for plyometric training. NSCA PT J. 2003, 2, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Potach, D.H.; Chu, D.A. Plyometric training. In Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning; Beachle, T.R., Earle, R.W., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, M.; Arampatzis, A.; Schade, F.; Brüggemann, G.P. The effect of drop jump starting height and contact time on power, work performed, and moment of force. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D.J.; Browne, D.T.; Byrne, P.J.; Richardson, N. Interday reliability of the reactive strength index and optimal drop height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwick, W.J.; Bird, S.P.; Tufano, J.J.; Seitz, L.B.; Haff, G.G. The intraday reliability of the reactive strength index calculated from a drop jump in professional men’s basketball. Inj. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.; Hobbs, S.; Moore, J. The ten to five repeated jump test: A new test for evaluation of lower body reactive strength. In Proceedings of the BASES 2011 Annual Student Conference, Chester, UK, 12–13 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Comyns, T.M.; Flanagan, E.P.; Fleming, S.; Fitzgerald, E.; Harper, D.J. Interday reliability and usefulness of a reactive strength index derived from 2 maximal rebound jump tests. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, G.; Dizdar, D.; Jukic, I.; Cardinale, M. Reliability and factorial validity of squat and countermovement jump tests. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 551–555. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, P. Reliability issues in performance analysis. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2007, 7, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Lefebvre, B.; Laursen, P.B.; Ahmaidi, S. Reliability, usefulness, and validity of the 30–15 intermittent ice test in young elite ice hockey players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Caulfield, B. A method for monitoring reactive strength index. Procedia Eng. 2010, 2, 3115–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, R.; Kenny, I.C.; Harrison, A.J. Assessing reactive strength measures in jumping and hopping using the Optojump™ system. J. Hum. Kinet. 2016, 54, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, I.C.; Cairealláin, A.Ó.; Comyns, T.M. Validation of an electronic jump mat to assess stretch-shortening cycle function. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, M.A.; Whelan, D.F.; Ward, T.E.; Delahunt, E.; Caulfield, B. Classification of lunge biomechanics with multiple and individual inertial measurement units. Sports Biomech. 2017, 16, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S.; Dopsaj, M.; Tomažič, S.; Kos, A.; Nedeljković, A.; Umek, A. Can IMU provide an accurate vertical jump height estimate? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, S.; Gonzalez, M.P.; Dietze-Hermosa, M.S.; Eggleston, J.D.; Dorgo, S. Common vertical jump and reactive strength index measuring devices: A validity and reliability analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comyns, T.M.; Murphy, J.; O’Leary, D. Reliability, Usefulness, and Validity of Field-Based Vertical Jump Measuring Devices. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 37, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro-Bombú, R.; Field, A.; Santos, A.C.; Rama, L. Validity and reliability of the Output sport device for assessing drop jump performance. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1015526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edriss, S.; Romagnoli, C.; Caprioli, L.; Zanela, A.; Panichi, E.; Campoli, F.; Padua, E.; Annino, G.; Bonaiuto, V. The role of emergent technologies in the dynamic and kinematic assessment of human movement in sport and clinical applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Reilly, T.; Malone, S.; Keane, J.; Doran, D. Science and Hurling: A Review. Sports 2022, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.; Reilly, T. Circadian variation in sports performance. Sports Med. 1996, 21, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abood, S.A.; Davids, K.; Bennett, S.J. Specificity of task constraints and effects of visual demonstrations and verbal instructions in directing learners’ search during skill acquisition. J. Mot. Behav. 2001, 33, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werstein, K.M.; Lund, R.J. The effects of two stretching protocols on the reactive strength index in female soccer and rugby players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1564–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, S.; Gonzalez, M.P.; Dietze-Hermosa, M.S.; Martinez, A.; Rodriguez, S.; Gomez, M.; Cubillos, N.; Ibarra-Mejia, G.; Tan, E.; Dorgo, S. Effects of different stretching modalities on the antagonist and agonist muscles on isokinetic strength and vertical jump performance in young men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagaduan, J.C.; Pojskić, H.; Užičanin, E.; Babajić, F. Effect of various warm-up protocols on jump performance in college football players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 35, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.P.; Ebben, W.P.; Jensen, R.L. Reliability of the reactive strength index and time to stabilization during depth jumps. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, K.; Flanagan, E.P. Establishing the reliability & meaningful change of the drop-jump reactive strength index. J. Aust. Strength Cond. 2015, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Makaruk, H.; Porter, J.M.; Czaplicki, A.; Sadowski, J.; Sacewicz, T. The role of attentional focus in plyometric training. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2012, 52, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Comyns, T.M.; Brady, C.J.; Molloy, J. Effect of attentional focus strategies on the biomechanical performance of the drop jump. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuu, S.; Musalem, L.L.; Beach, T.A. Verbal instructions acutely affect drop vertical jump biomechanics—Implications for athletic performance and injury risk assessments. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2816–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G.; Lauterbach, B.; Toole, T. The learning advantages of an external focus of attention in golf. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1999, 70, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G. Spreadsheets for analysis of validity and reliability. Sportscience 2015, 19, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G. How to interpret changes in an athletic performance test. Sportscience 2004, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, A.; O’Donoghue, P.; Cropley, B. Performance profiling in sports coaching: A review. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2013, 13, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.P.; Comyns, T.M. The use of contact time and the reactive strength index to optimize fast stretch-shortening cycle training. Strength Cond. J. 2008, 30, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, C.; Dos’Santos, T.; McMahon, J.J. A comparison between the drop jump and 10/5 repeated jumps test to measure the reactive strength index. Prof. Strength Cond. 2020, 57, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, B.; Browne, D.; Horan, D. Age-Group Differences in Reactive Strength and Measures of Intra-day Reliability in Female International Footballers. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musham, C.; Fitzpatrick, J.F. Familiarisation and reliability of the isometric mid-thigh pull in elite youth soccer players. Sports Perf. Sci. Rep. 2020, 85, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Participants | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DJ | 1.64 ± 0.26 | 1.65 ± 0.26 | 1.69 ± 0.30 |

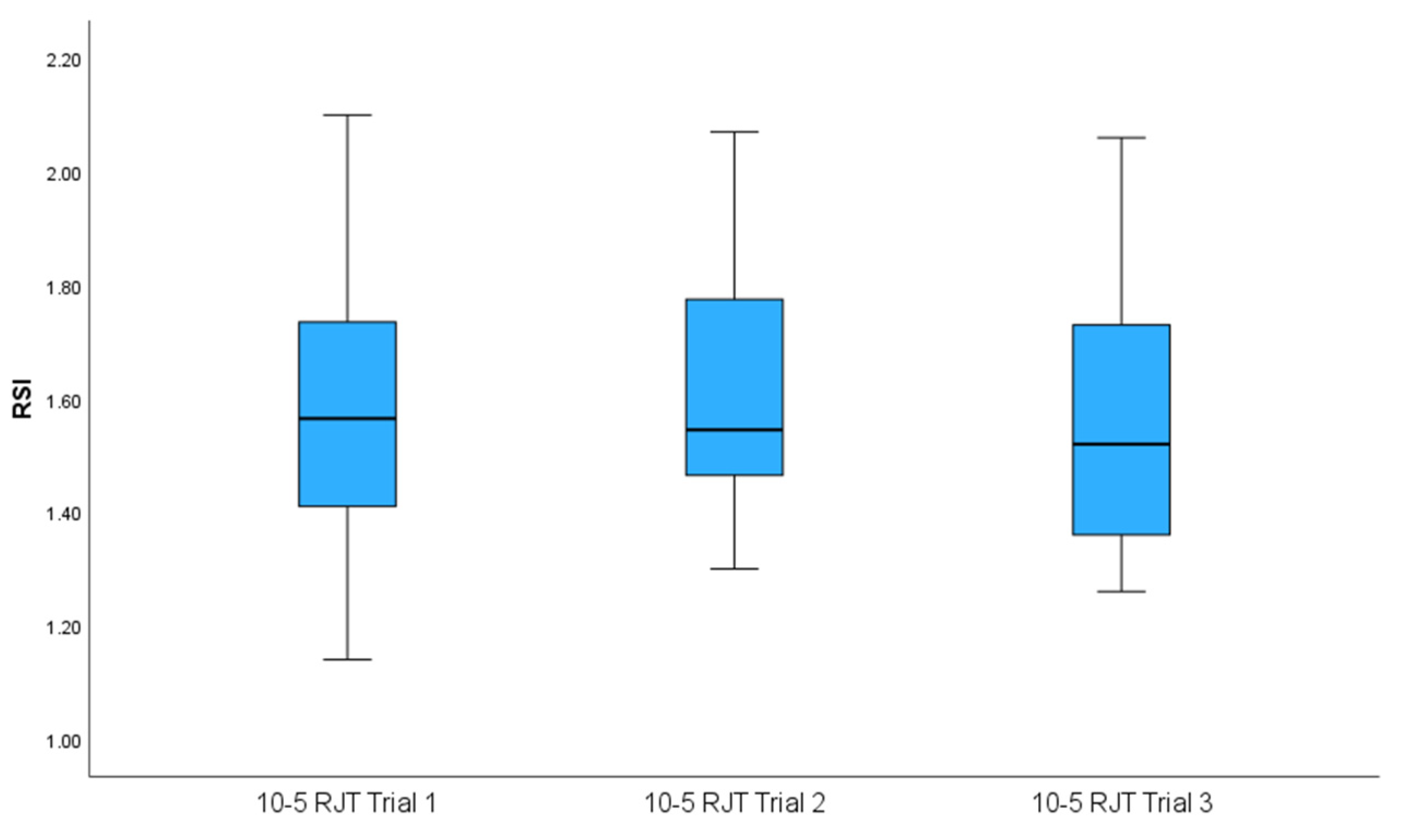

| 10-5 RJT | 1.59 ± 0.24 | 1.60 ± 0.21 | 1.56 ± 0.23 |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ICC | Lower | Higher | CV% | Lower | Higher | TE | SWC 0.2 | Rating | SWC 0.5 | Rating |

| DJ | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 0.09 | 0.05 | Marginal | 0.14 | Good |

| 10-5 RJT | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 7.2 | 0.08 | 0.04 | Marginal | 0.11 | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Clancy, C.P.; Collins, K.D.; Comyns, T.M. Reliability of the Output Sports Inertial Measurement Unit in Measuring a Reactive Strength Index from the Drop Jump and 10-5 Rebound Jump Test. Sports 2026, 14, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010015

Clancy CP, Collins KD, Comyns TM. Reliability of the Output Sports Inertial Measurement Unit in Measuring a Reactive Strength Index from the Drop Jump and 10-5 Rebound Jump Test. Sports. 2026; 14(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleClancy, Conor P., Kieran D. Collins, and Thomas M. Comyns. 2026. "Reliability of the Output Sports Inertial Measurement Unit in Measuring a Reactive Strength Index from the Drop Jump and 10-5 Rebound Jump Test" Sports 14, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010015

APA StyleClancy, C. P., Collins, K. D., & Comyns, T. M. (2026). Reliability of the Output Sports Inertial Measurement Unit in Measuring a Reactive Strength Index from the Drop Jump and 10-5 Rebound Jump Test. Sports, 14(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010015