Relationships Between Dry-Land Load—Velocity Parameters and In-Water Bioenergetic Performance in Competitive Swimmers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Load–Velocity Profile and Maximal Power Assessment Using the Bench Press

2.4. Measurement of Critical Velocity (CV) and Anaerobic Capacity (W)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandes, R.J.; Carvalho, D.D.; Figueiredo, P. Training zones in competitive swimming: A biophysical approach. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1363730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, E.; Pearson, S.; Saxby, D.; Minahan, C.; Tor, E. Stroke Kinematics, Temporal Patterns, Neuromuscular Activity, Pacing and Kinetics in Elite Breaststroke Swimming: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiyami, A.; Nuhmani, S.; Joseph, R.; Abualait, T.S.; Muaidi, Q. Efficacy of Core Training in Swimming Performance and Neuromuscular Parameters of Young Swimmers: A Randomised Control Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T.; Njøs, N.; Eriksrud, O.; Olstad, B.H. The Relationship Between Selected Load-Velocity Profile Parameters and 50 m Front Crawl Swimming Performance. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 625411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Pardos, B.; Gomez-Bruton, A.; Matute-Llorente, A.; Gonzalez-Aguero, A.; Gomez-Cabello, A.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Casajus, J.A.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G. Nonspecific Resistance Training and Swimming Performance: Strength or Power? A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J.; Mastalerz, A.; Gromisz, W. Transfer of Dry-Land Resistance Training Modalities to Swimming Performance. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 74, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.J.; Neiva, H.P.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Nunes, C.; Marinho, D.A. The effects of dry-land strength training on competitive sprinter swimmers. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2021, 19, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Lin, S.C. The methodology of resistance training is crucial for improving short-medium distance front crawl performance in competitive swimmers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1406518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samozino, P.; Peyrot, N.; Edouard, P.; Nagahara, R.; Jimenez-Reyes, P.; Vanwanseele, B.; Morin, J.B. Optimal mechanical force-velocity profile for sprint acceleration performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, J.B.; Samozino, P. Interpreting Power-Force-Velocity Profiles for Individualized and Specific Training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016, 11, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, S.; Crowley, E.; Sammoud, S.; Negra, Y.; Hammami, R.; Chortane, O.G.; Khalifa, R.; Chortane, S.G.; van den Tillaar, R. What Is the Optimal Strength Training Load to Improve Swimming Performance? A Randomized Trial of Male Competitive Swimmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacca, R.; Fernandes, R.J.; Pyne, D.B.; Castro, F.A. Swimming Training Assessment: The Critical Velocity and the 400-m Test for Age-Group Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prampero, P.E.; Dekerle, J.; Capelli, C.; Zamparo, P. The critical velocity in swimming. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 102, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakayoshi, K.; Ikuta, K.; Yoshida, T.; Udo, M.; Moritani, T.; Mutoh, Y.; Miyashita, M. Determination and validity of critical velocity as an index of swimming performance in the competitive swimmer. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1992, 64, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, H.M.; Wakayoshi, K.; Hollander, A.P.; Ogita, F. Simulated front crawl swimming performance related to critical speed and critical power. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacca, R.; Wenzel, B.M.; Piccin, J.S.; Marcilio, N.R.; Lopes, A.L.; de Souza Castro, F.A. Critical velocity, anaerobic distance capacity, maximal instantaneous velocity and aerobic inertia in sprint and endurance young swimmers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, H.P.; Fernandes, R.J.; Vilas-Boas, J.P. Anaerobic critical velocity in four swimming techniques. Int. J. Sports Med. 2011, 32, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Romero-Moraleda, B.; Díaz-Lara, F.J.; Rubia, A.; González-García, J.; Mon-López, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Differences in Mean Propulsive Velocity between Men and Women in Different Exercises. Sports 2023, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haff, G.G.; Triplett, N.T. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 4th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chalkiadakis, I.; Arsoniadis, G.G.; Toubekis, A.G. Dry-Land Force-Velocity, Power-Velocity, and Swimming-Specific Force Relation to Single and Repeated Sprint Swimming Performance. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Funai, Y.; Matsunami, M.; Taba, S.; Takahashi, S. Physiological Responses and Stroke Variables during Arm Stroke Swimming Using Critical Stroke Rate in Competitive Swimmers. Sports 2022, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morouço, P.; Neiva, H.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Garrido, N.; Marinho, D.A.; Marques, M.C. Associations between dry land strength and power measurements with swimming performance in elite athletes: A pilot study. J. Hum. Kinet. 2011, 29A, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, B.H.; Hunger, L.; Ljødal, I.; Ringhof, S.; Gonjo, T. The relationship between load-velocity profiles and 50 m breaststroke performance in national-level male swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgente, V.; Agudo-Ortega, A.; Lopez-Hernandez, A.; Santos Del Cerro, J.; Minciacchi, D.; González Ravé, J.M. Relationship between Maximum Force-Velocity Exertion and Swimming Performances among Four Strokes over Medium and Short Distances: The Stronger on Dry Land, the Faster in Water? J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.J.; Owen, N.J.; Cunningham, D.J.; Cook, C.J.; Kilduff, L.P. Strength and power predictors of swimming starts in international sprint swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llodio, I.; Yanci, J.; Usandizaga, M.; Larrea, A.; Iturricastillo, A.; Cámara, J.; Granados, C. Repeatability and Validity of Different Methods to Determine the Anaerobic Threshold Through the Maximal Multistage Test in Male Cyclists and Triathletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espada, M.; Costa, A.; Louro, H.; Conceição, A.; Pereira, A. Anaerobic critical velocity and sprint swimming performance in master swimmers. Int. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Born, D.P.; Febles-Castro, A.; Gay, A.; López-Belmonte, Ó.; Morales-Ortíz, E.; Arellano, R. Exploring the load–velocity profile with sprint swimming performance and sex differences. Int. J. Sports Med. 2025, 46, 595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, R.; Kennedy, R.; McCabe, C. Longitudinal monitoring of load-velocity variables in preferred-stroke and front-crawl with national and international swimmers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1585319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, N.; Marinho, D.A.; Barbosa, T.M.; Costa, A.M.; Silva, A.J.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Marques, M.C. Relationships between dry land strength, power variables and short sprint performance in young competitive swimmers. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2010, II, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Cuartero, C.; López-Hernández, A.; Rodríguez-Barbero, S.; González-Ravé, J.M. Swimming coaches’ perceptions and practices on periodization, performance monitoring, and training management. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1642020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| F0 (N) | 600.16 ± 22.18 |

| V0 (m/s) | 2.87 ± 0.12 |

| Pmax (W) | 430.16 ± 19.38 |

| 100 m (s) | 29.35 ± 1.43 |

| 200 m (s) | 66.30 ± 3.23 |

| 400 m (s) | 140.88 ± 6.90 |

| Critical velocity (m/s) | 2.70 ± 0.13 |

| Anaerobic capacity (m) | 21.20 ± 1.17 |

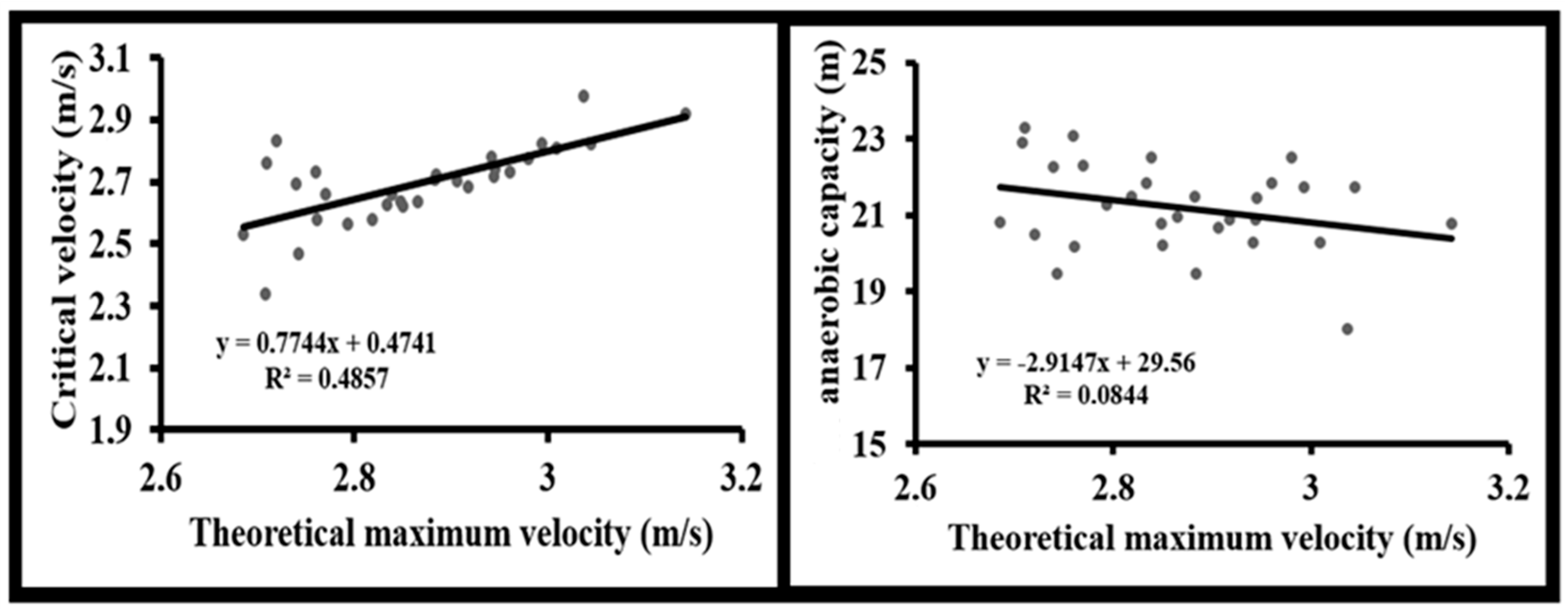

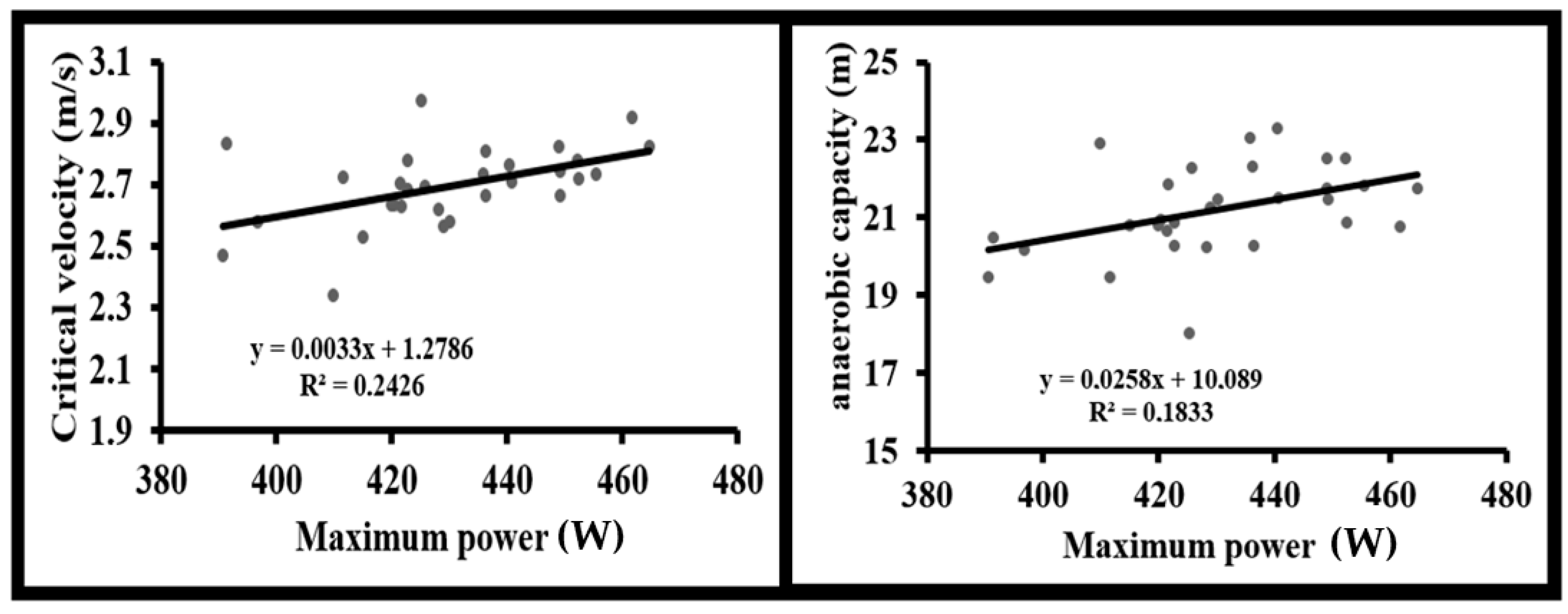

| Variable | Critical Velocity | Anaerobic Capacity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | F | p-Value | R | F | p-Value | |

| F0 | 0.152 | 0.664 | 0.422 | 0.842 | 68.001 | <0.001 |

| V0 | 0.697 | 26.446 | <0.001 | 0.291 | 2.582 | 0.119 |

| Pmax | 0.493 | 8.969 | 0.006 | 0.428 | 6.283 | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amara, S.; Bouassida, A.; Tillaar, R.v.d. Relationships Between Dry-Land Load—Velocity Parameters and In-Water Bioenergetic Performance in Competitive Swimmers. Sports 2026, 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010011

Amara S, Bouassida A, Tillaar Rvd. Relationships Between Dry-Land Load—Velocity Parameters and In-Water Bioenergetic Performance in Competitive Swimmers. Sports. 2026; 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmara, Sofiene, Anissa Bouassida, and Roland van den Tillaar. 2026. "Relationships Between Dry-Land Load—Velocity Parameters and In-Water Bioenergetic Performance in Competitive Swimmers" Sports 14, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010011

APA StyleAmara, S., Bouassida, A., & Tillaar, R. v. d. (2026). Relationships Between Dry-Land Load—Velocity Parameters and In-Water Bioenergetic Performance in Competitive Swimmers. Sports, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010011