Downhill Running-Induced Muscle Damage in Trail Runners: An Exploratory Study Regarding Training Background and Running Gait

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Overview

2.3. Cardiopulmonary Uphill Incremental Test

2.4. Downhill Running Protocol

2.5. Isometric Ankle Plantar Flexion and Half-Squat Strength Tests

2.6. Blood Sampling and Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

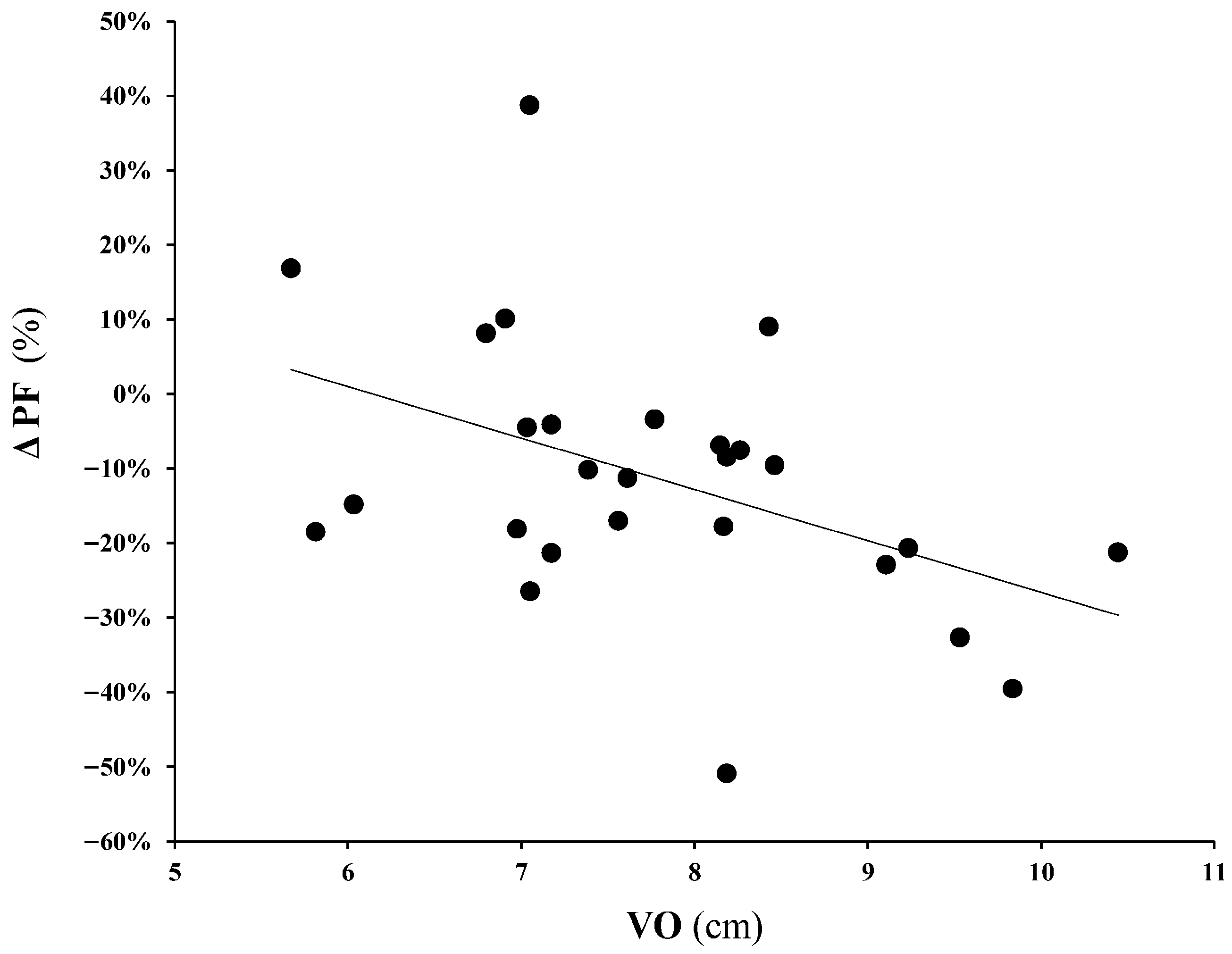

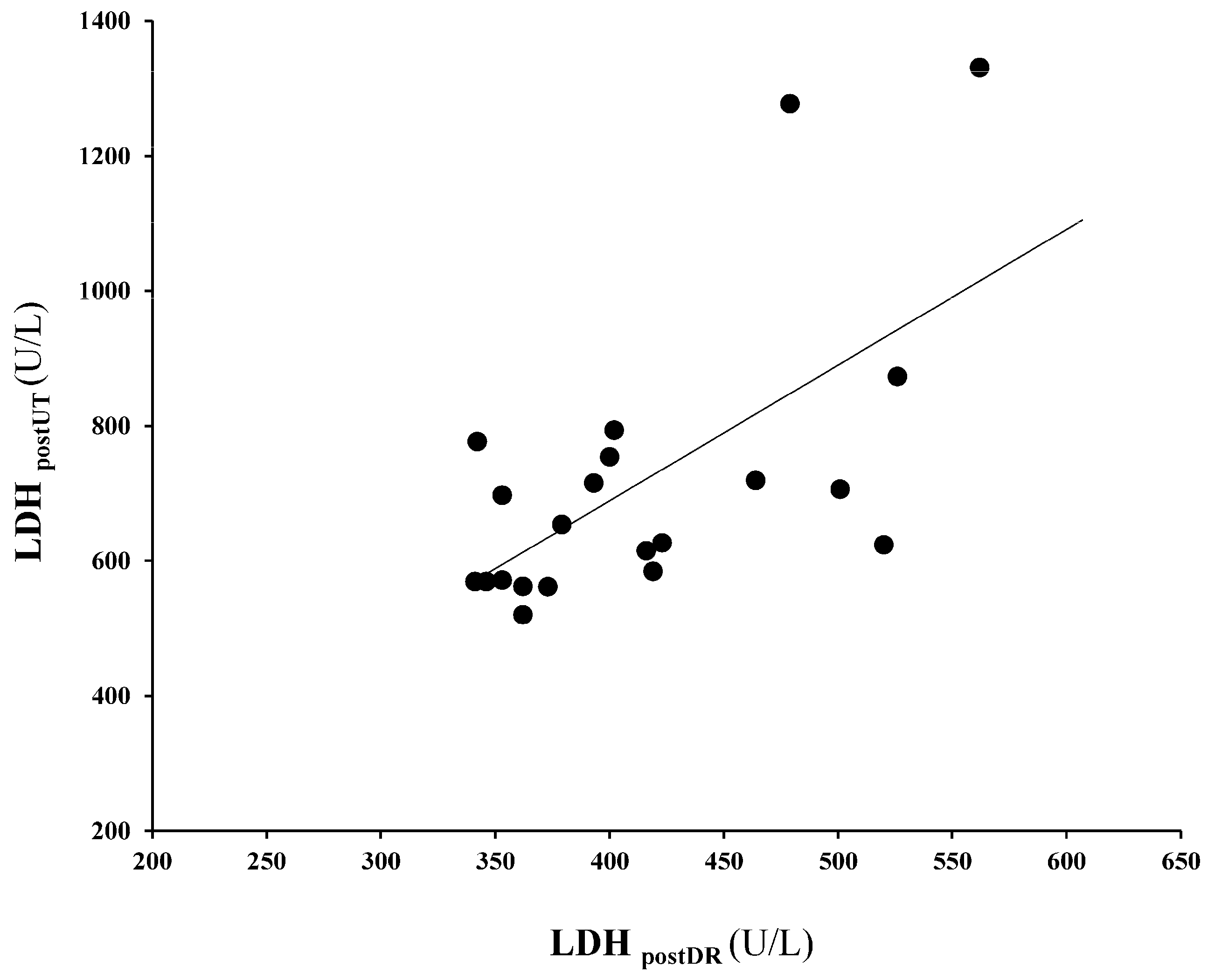

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| %FM | Percentage of fat mass |

| %LBM | Percentage of lean body mass |

| %VT1 | Percentage of VO2peak at the first ventilatory threshold |

| %VT2 | Percentage of VO2peak at the second ventilatory threshold |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise test |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| DR | Downhill running |

| EIMD | Exercise-induced muscle damage |

| GCT | Ground contact time |

| FR | Frequency of respiration |

| HR | Heart rate |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| Mb | Myoglobin |

| PF | Isometric ankle plantar flexion strength |

| SF | Step frequency |

| SL | Step length |

| RBE | Repeated bout effect |

| SQ | Isometric half-squat strength |

| TR | Trail runners |

| UT | Ultra-trail |

| UW | Uphill walking |

| VE | Minute ventilation |

| VO | Vertical oscillation |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen uptake |

| VO2peak | Peak oxygen uptake |

| VT | Tidal volume |

| VT1 | First ventilatory threshold |

| VT2 | Second ventilatory threshold |

| Vvertpeak | Peak vertical speed reached at the cardiopulmonary exercise test |

| VvertVT1 | Vertical speed at the first ventilatory threshold |

| VvertVT2 | Vertical speed at the second ventilatory threshold |

References

- Kerherve, H.A.; Cole-Hunter, T.; Wiegand, A.N.; Solomon, C. Pacing during an ultramarathon running event in hilly terrain. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genitrini, M.; Fritz, J.; Zimmermann, G.; Schwameder, H. Downhill Sections Are Crucial for Performance in Trail Running Ultramarathons-A Pacing Strategy Analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.; Pryor, J.L.; Casa, D.J.; Belval, L.N.; Vance, J.S.; DeMartini, J.K.; Maresh, C.M.; Armstrong, L.E. Bike and run pacing on downhill segments predict Ironman triathlon relative success. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.D.; Ingwerson, J.L.; Rogers, I.R.; Hew-Butler, T.; Stuempfle, K.J. Increasing creatine kinase concentrations at the 161-km Western States Endurance Run. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2012, 23, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, G.Y.; Tomazin, K.; Verges, S.; Vincent, C.; Bonnefoy, R.; Boisson, R.C.; Gergele, L.; Feasson, L.; Martin, V. Neuromuscular consequences of an extreme mountain ultra-marathon. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontemps, B.; Vercruyssen, F.; Gruet, M.; Louis, J. Downhill Running: What Are the Effects and How Can We Adapt? A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 2083–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, A.; Braun, B. Using a novel data resource to explore heart rate during mountain and road running. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, G.Y. Can neuromuscular fatigue explain running strategies and performance in ultra-marathons? The flush model. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, N.; Biasutti, L.; Salvadego, D.; Alemayehu, H.K.; Grassi, B.; Lazzer, S. Changes in Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Capacity After a Trail Running Race. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2020, 15, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Coso, J.; Fernandez de Velasco, D.; Abian-Vicen, J.; Salinero, J.J.; Gonzalez-Millan, C.; Areces, F.; Ruiz, D.; Gallo, C.; Calleja-Gonzalez, J.; Perez-Gonzalez, B. Running pace decrease during a marathon is positively related to blood markers of muscle damage. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiller, N.B.; Millet, G.Y. Decoding Ultramarathon: Muscle Damage as the Main Impediment to Performance. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.C.; Nosaka, K.; Tu, J.H. Changes in running economy following downhill running. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassetarash, A.; Vernillo, G.; Kruger, R.L.; Edwards, W.B.; Millet, G.Y. Neuromuscular, biomechanical, and energetic adjustments following repeated bouts of downhill running. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontemps, B.; Gruet, M.; Louis, J.; Owens, D.J.; Miric, S.; Erskine, R.M.; Vercruyssen, F. The time course of different neuromuscular adaptations to short-term downhill running training and their specific relationships with strength gains. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 122, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giandolini, M.; Horvais, N.; Rossi, J.; Millet, G.Y.; Morin, J.B.; Samozino, P. Acute and delayed peripheral and central neuromuscular alterations induced by a short and intense downhill trail run. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemire, M.; Remetter, R.; Hureau, T.J.; Kouassi, B.Y.L.; Lonsdorfer, E.; Geny, B.; Isner-Horobeti, M.E.; Favret, F.; Dufour, S.P. High-intensity downhill running exacerbates heart rate and muscular fatigue in trail runners. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.C.R.; Bassan, N.M.; Cardozo, A.C.; Goncalves, M.; Greco, C.C.; Denadai, B.S. Isometric pre-conditioning blunts exercise-induced muscle damage but does not attenuate changes in running economy following downhill running. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2018, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, L.; Deakin, G.B.; Devantier-Thomas, B.; Singh, U.; Doma, K. The Effects of Pre-conditioning on Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1537–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Suzuki, K.; Wilson, G.; Hordern, M.; Nosaka, K.; Mackinnon, L.; Coombes, J.S. Exercise-induced muscle damage, plasma cytokines, and markers of neutrophil activation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortenblad, N.; Zachariassen, M.; Nielsen, J.; Gejl, K.D. Substrate utilization and durability during prolonged intermittent exercise in elite road cyclists. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 2193–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucende, G.; Chamoux, M.; Defer, T.; Rissetto, C.; Mourot, L.; Cassirame, J. Specific Incremental Test for Aerobic Fitness in Trail Running: IncremenTrail. Sports 2022, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, E.M. Calibration and verification of instruments. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 1197–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.S.; McLellan, T.M. The transition from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1980, 51, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.A.; Kravchychyn, A.C.; Peserico, C.S.; da Silva, D.F.; Mezzaroba, P.V. Incremental test design, peak ‘aerobic’ running speed and endurance performance in runners. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, M.; Hureau, T.J.; Remetter, R.; Geny, B.; Kouassi, B.Y.L.; Lonsdorfer, E.; Isner-Horobeti, M.E.; Favret, F.; Dufour, S.P. Trail Runners Cannot Reach V O2max during a Maximal Incremental Downhill Test. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pinillos, F.; Roche-Seruendo, L.E.; Marcen-Cinca, N.; Marco-Contreras, L.A.; Latorre-Roman, P.A. Absolute Reliability and Concurrent Validity of the Stryd System for the Assessment of Running Stride Kinematics at Different Velocities. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.P.; Fullerton, E.; Walton, L.; Funnell, E.; Pantazis, D.; Lugo, H. The validity and reliability of wearable devices for the measurement of vertical oscillation for running. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezuela-Espejo, V.; Hernandez-Belmonte, A.; Courel-Ibanez, J.; Conesa-Ros, E.; Mora-Rodriguez, R.; Pallares, J.G. Are we ready to measure running power? Repeatability and concurrent validity of five commercial technologies. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Osorio, V.; Fuentes-Barría, H.; Sanhueza-González, S.; Sandoval-Jelves, C.; Aguilera-Eguía, R.; Rojas-Gómez, D.; Roco-Videla, Á.; Caviedes-Olmos, M. Reliability and Repeatability of the Low-Cost G-Force Load Cell System in Isometric Hip Abduction and Adduction Tests: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufner, T.J.; Iacono, A.D.; Wheeler, J.R.; Lanier, N.B.; Gillespie, G.; Proper, A.E.; Moon, J.M.; Fretti, S.K.; Stout, J.R.; Beato, M.; et al. The reliability of functional and systemic markers of muscle damage in response to a flywheel squat protocol. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 1001–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Navarro, I.; Montoya-Vieco, A.; Collado, E.; Hernando, B.; Hernando, C. Inspiratory and Lower-Limb Strength Importance in Mountain Ultramarathon Running. Sex Differences and Relationship with Performance. Sports 2020, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, V.J.; Smola, C.; Schmitt, P. Evaluation of the Beckman Coulter DxC 700 AU chemistry analyzer. Pract. Lab. Med. 2020, 18, e00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, D.B.; Costill, D.L. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J. Appl. Physiol. 1974, 37, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alis, R.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Primo-Carrau, C.; Lozano-Calve, S.; Dipalo, M.; Aloe, R.; Blesa, J.R.; Romagnoli, M.; Lippi, G. Hemoconcentration induced by exercise: Revisiting the Dill and Costill equation. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, e630–e637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.C.; Nosaka, K.; Lin, M.J.; Chen, H.L.; Wu, C.J. Changes in running economy at different intensities following downhill running. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalchat, E.; Gaston, A.F.; Charlot, K.; Penailillo, L.; Valdes, O.; Tardo-Dino, P.E.; Nosaka, K.; Martin, V.; Garcia-Vicencio, S.; Siracusa, J. Appropriateness of indirect markers of muscle damage following hih limbs eccentric-biased exercises: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saita, Y.; Hattori, K.; Hokari, A.; Ohyama, T.; Inoue, J.; Nishimura, T.; Nemoto, S.; Aoyagi, S. Plasma myoglobin indicates muscle damage associated with acceleration/deceleration during football. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2023, 63, 1337–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilidis, G.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou, A.; Krase, A.A.; Tsatalas, T.; Shum, G.; Sakkas, G.K.; Koutedakis, Y.; Karatzaferi, C. The effects of training with high-speed interval running on muscle performance are modulated by slope. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggaley, M.; Vernillo, G.; Martinez, A.; Horvais, N.; Giandolini, M.; Millet, G.Y.; Edwards, W.B. Step length and grade effects on energy absorption and impact attenuation in running. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020, 20, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, A.V.; Eston, R.G.; Tilzey, C. Effect of stride length manipulation on symptoms of exercise-induced muscle damage and the repeated bout effect. J. Sports Sci. 2001, 19, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giandolini, M.; Horvais, N.; Rossi, J.; Millet, G.Y.; Morin, J.B.; Samozino, P. Effects of the foot strike pattern on muscle activity and neuromuscular fatigue in downhill trail running. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giandolini, M.; Horvais, N.; Rossi, J.; Millet, G.Y.; Samozino, P.; Morin, J.B. Foot strike pattern differently affects the axial and transverse components of shock acceleration and attenuation in downhill trail running. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degache, F.; Guex, K.; Fourchet, F.; Morin, J.B.; Millet, G.P.; Tomazin, K.; Millet, G.Y. Changes in running mechanics and spring-mass behaviour induced by a 5-hour hilly running bout. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, G.Y.; Hoffman, M.D.; Morin, J.B. Sacrificing economy to improve running performance—a reality in the ultramarathon? J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 113, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, J.B.; Tomazin, K.; Edouard, P.; Millet, G.Y. Changes in running mechanics and spring-mass behavior induced by a mountain ultra-marathon race. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, H.V. Concept of an extracellular regulation of muscular metabolic rate during heavy exercise in humans by psychophysiological feedback. Experientia 1996, 52, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Sample (n = 36) | Males (n = 25) | Females (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45 ± 8 | 44 ± 6 | 49 ± 9 |

| Number of years running | 15 ± 8 | 14 ± 7 | 15 ± 8 |

| Number of races > 100 km | 3 ± 4 | 4 ± 5 | 2 ± 2 |

| Weekly training days | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 |

| Weekly running volume (km) | 71 ± 22 | 70 ± 22 | 74 ± 23 |

| Weekly cumulative positive/negative elevation (m) | 2514 ± 1132 | 2651 ± 1233 | 2172 ± 780 |

| Weekly training hours | 13 ± 6 | 13 ± 7 | 12 ± 4 |

| Strength training (%) | 75.7% | 76% | 75% |

| Downhill repetitions (%) | 21.6% | 24% | 16.7% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23 ± 2.4 | 23.7 ± 2.2 | 21.5 ± 2.2 |

| Height (cm) | 171 ± 8 | 177 ± 5 | 161 ± 4 |

| FM (%) | 18.5 ± 6.4 | 17.1 ± 6 | 21.8 ± 6.6 |

| LBM (%) | 78.3 ± 6 | 80 ± 5.5 | 74.3 ± 5.5 |

| VvertVT1 (m/h) | 820.8 ± 97.6 | 853.2 ± 87 | 746.9 ± 80.9 |

| %VT1 (% VO2peak) | 65.2 ± 5.7 | 63.8 ± 5.5 | 68.5 ± 5.1 |

| VvertVT2 (m/h) | 1086.9 ± 140.4 | 1135.7 ± 134.8 | 976 ± 76.6 |

| %VT2 (% VO2peak) | 82.8 ± 7.1 | 82.2 ± 7 | 84.2 ± 7.7 |

| VO2peak (ml O2/kg/min) | 57 ± 8 | 59 ± 7.9 | 52.4 ± 6.6 |

| Vvertpeak (m/h) | 1442.9 ± 182.2 | 1514.6 ± 159.7 | 1279.9 ± 113.7 |

| Pre | Post | Change from Pre, % | Cohen d; 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK (U/L) | 229 ± 168 | 261 ± 177 * | 17.4 ± 10.2% | 0.19; −0.27 to 0.65 |

| LDH (U/L) | 405 ± 78 | 428 ± 75 * | 6.4 ± 9.9% | 0.3; −0.16 to 0.77 |

| Mb (ng/mL) | 31 ± 16 | 94 ± 47 * | 247.8 ± 229.3% | 1.85; 1.3 to 2.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martinez-Navarro, I.; Vicente-Mampel, J.; López-Grueso, R.; Suarez-Alcazar, M.-P.; Vilar-Fabra, C.; Collado-Boira, E.; Hernando, C. Downhill Running-Induced Muscle Damage in Trail Runners: An Exploratory Study Regarding Training Background and Running Gait. Sports 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010012

Martinez-Navarro I, Vicente-Mampel J, López-Grueso R, Suarez-Alcazar M-P, Vilar-Fabra C, Collado-Boira E, Hernando C. Downhill Running-Induced Muscle Damage in Trail Runners: An Exploratory Study Regarding Training Background and Running Gait. Sports. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Navarro, Ignacio, Juan Vicente-Mampel, Raul López-Grueso, María-Pilar Suarez-Alcazar, Cristina Vilar-Fabra, Eladio Collado-Boira, and Carlos Hernando. 2026. "Downhill Running-Induced Muscle Damage in Trail Runners: An Exploratory Study Regarding Training Background and Running Gait" Sports 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010012

APA StyleMartinez-Navarro, I., Vicente-Mampel, J., López-Grueso, R., Suarez-Alcazar, M.-P., Vilar-Fabra, C., Collado-Boira, E., & Hernando, C. (2026). Downhill Running-Induced Muscle Damage in Trail Runners: An Exploratory Study Regarding Training Background and Running Gait. Sports, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010012