Initial Validation of the Hungarian Version of Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (ANSKQ-HU)

Abstract

1. Introduction

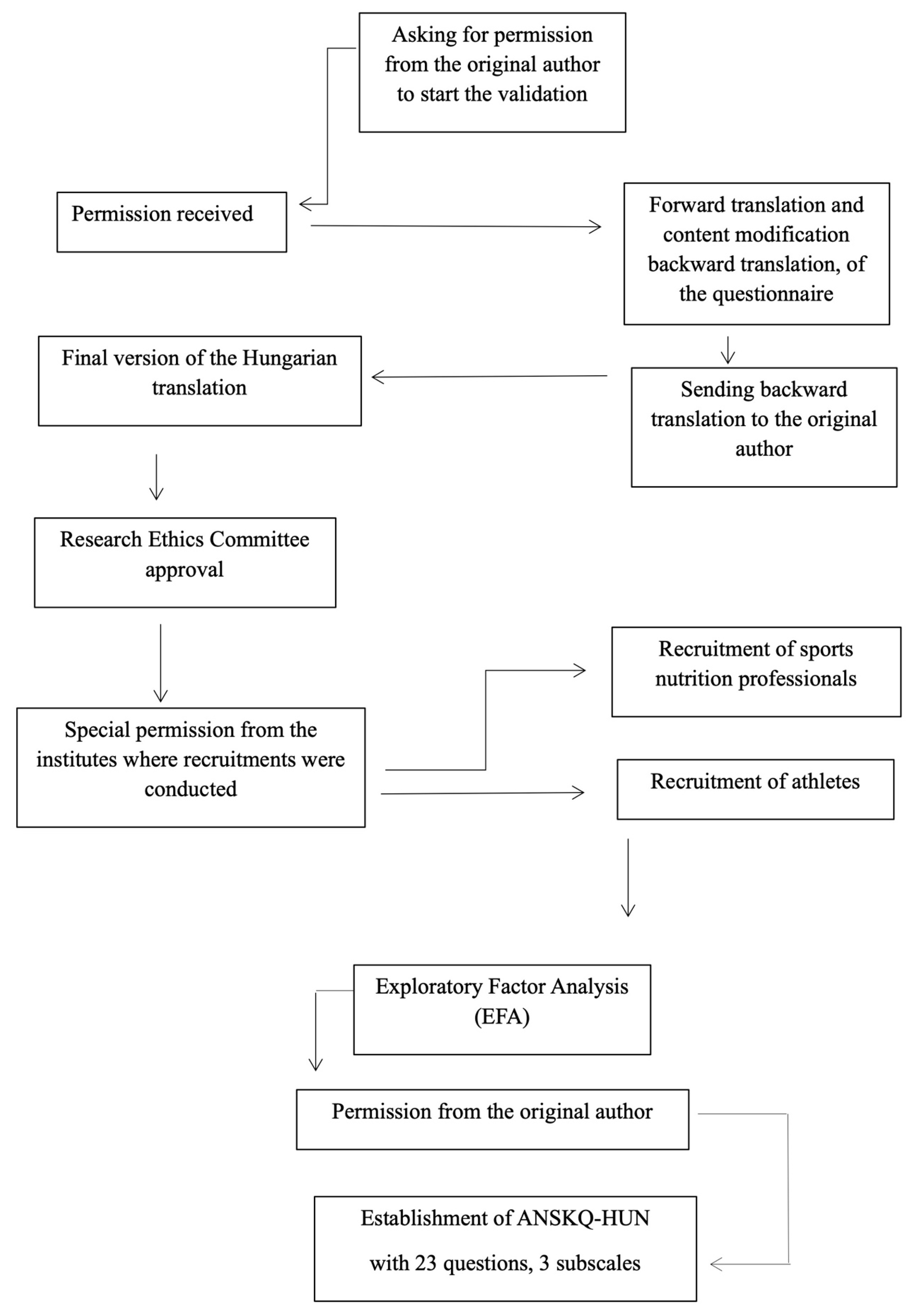

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. English (Abridged) Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire and International Adaptations

2.3. Development of the Hungarian Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire

2.4. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.5. Assessment of Reliability of Hungarian Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire

3. Statistical Analyses

3.1. Validation Procedures

3.2. Assessment of Participant Characteristics and Nutrition Knowledge

4. Results

4.1. Hungarian Version of the ANSKQ: Results of the Final Translated Tool

4.1.1. Face Validity Responses from Sports Nutrition Professionals (Expert Group)

4.1.2. Athlete Participant Characteristics

4.1.3. Item Difficulty

4.1.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the AN-SKQ-HU

4.1.5. Reliability

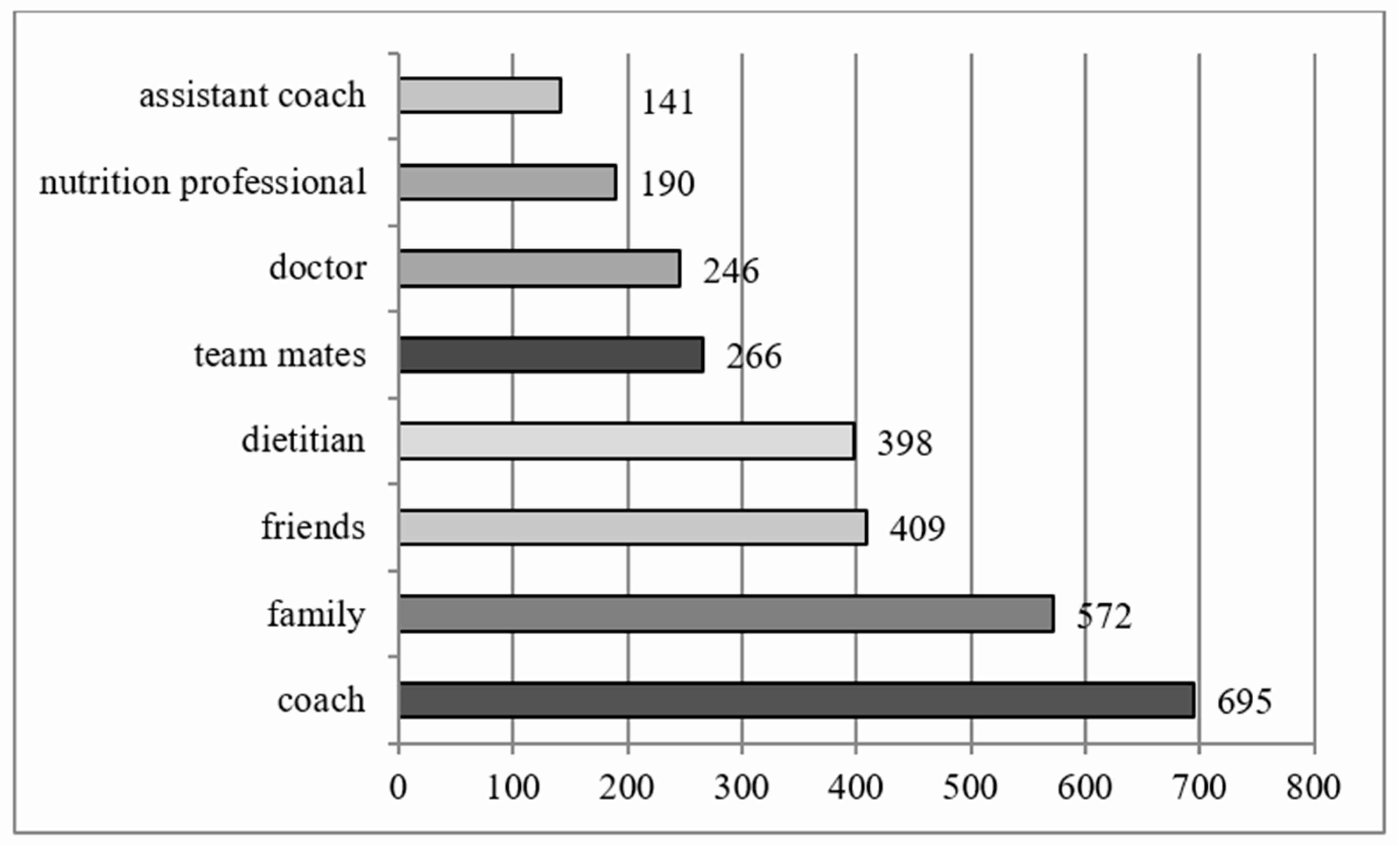

4.1.6. Nutrition Education and Information

4.1.7. Nutrition Knowledge

5. Discussion

- Fundamentals of nutrition, energy requirements of physical activity, and prohibited substances (FEP/F1);

- Micronutrients and performance-enhancing sports nutrition (MPE/F2);

- Utilization of macronutrients (UM/F3).

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANSKQ | Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire |

| ANSKQ-HU | Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire-Hungarian version |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| NSKQ | Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire |

| GSNKQ | General and Sports Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire |

| NSKQ-BR | Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire-Brazil version |

| WADA | World Anti-Doping Agency |

Appendix A

- (a)

- male

- (b)

- female

- (c)

- other

- (a)

- alone

- (b)

- with parents

- (c)

- with a spouse

- (d)

- with sportsmen

- (e)

- with sportsmen of other sports

- (f)

- other

- (a)

- yes (please specify)

- (b)

- no

- (a)

- local/of town

- (b)

- of country

- (c)

- national

- (d)

- international

- (a)

- trainer

- (b)

- support trainer

- (c)

- dietitian

- (d)

- doctor

- (e)

- friends

- (f)

- family

- (g)

- nutritional science expert

- (h)

- team mates

- (a)

- scientific periodical

- (b)

- sport trainer/strength-conditioner trainer

- (c)

- leader coach

- (d)

- dietitian

- (e)

- nutritional science expert

- (f)

- doctor

- (g)

- family

- (h)

- friends

- (i)

- searching on the internet (please give the used websites)

- (j)

- media (magazines, radio, television)

- (k)

- social media (Facebook, Twitter)

- (l)

- teammates

- (a)

- I receive information only in relation to nutrition

- (b)

- I receive information in relation to nutrition as well as possibilities of consulting with nutrition experts/dietitians

- (c)

- neither of the above

- (a)

- yes, of acquiring knowledge of sports leagues

- (b)

- yes, of acquiring knowledge of nourishment as well as providing the possibility to keep in contact with dietitians/nutritional scientists

- (c)

- no, it isn’t the task of sports leagues

- (a)

- access to reliable fundamentals and facts relating to nutrients and healthy nourishment

- (b)

- access to reliable, sporting nutrition-based knowledge

- (c)

- partaking in group lectures held by dietitians/nutritional scientists

- (d)

- opportunities of personal/individual consultation with dietitians/nutritional experts

- (e)

- cooking classes/course

- (a)

- yes

- (b)

- no

- (a)

- outstanding

- (b)

- above average

- (c)

- below average

- (d)

- insufficient

- (a)

- strongly agree

- (b)

- agree

- (c)

- not agree, neither disagree

- (d)

- disagree

- (a)

- yes

- (b)

- no

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- high

- (b)

- low

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- high

- (b)

- low

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- high

- (b)

- low

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- enough

- (b)

- not enough

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- enough

- (b)

- not enough

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- enough

- (b)

- not enough

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- enough

- (b)

- not enough

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- enough

- (b)

- not enough

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- 100 g (1 g/bodyweight kilogram)

- (b)

- 150 g (1,5 g/bodyweight kilogram)

- (c)

- 500 g (5 g/bodyweight kilogram)

- (d)

- should consume as much protein as he/she can

- (e)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- fluid, fat and carbohydrates

- (b)

- fluid, fiber and carbohydrates

- (c)

- fluid and carbohydrates

- (d)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- I agree.

- (b)

- I disagree.

- (c)

- I’m not sure

- (a)

- protein shake

- (b)

- mature banana

- (c)

- 2 boiled eggs

- (d)

- one handful of seeds

- (e)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- 1.5 g/bodyweight kilogram for most sportsmen

- (b)

- 1 g/bodyweight kilogram for most sportsmen

- (c)

- 0.3 g/bodyweight kilogram for most sportsmen

- (d)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- caffeine

- (b)

- ferulic acid

- (c)

- bicarbonate

- (d)

- leucine

- (e)

- I’m not sure.

- (a)

- caffeine

- (b)

- bicarbonate

- (c)

- the use of testosterone

- (d)

- I’m not sure.

Appendix B

- (a)

- férfi

- (b)

- nő

- (c)

- egyéb

- (a)

- egyedül

- (b)

- szülőkkel

- (c)

- párral/házastárssal

- (d)

- sportolókkal

- (e)

- más sportágak sportolóival

- (f)

- egyéb

- (a)

- igen (kérem pontosítsa)

- (b)

- nem

- (a)

- helyi/városi

- (b)

- megyei

- (c)

- országos

- (d)

- nemzetközi

- (a)

- edző

- (b)

- segédedző

- (c)

- dietetikus

- (d)

- orvos

- (e)

- barátok

- (f)

- család

- (g)

- táplálkozástudományi szakember

- (h)

- csapattársak

- (a)

- tudományos folyóirat

- (b)

- sportedző/erő-kondícionáló edző

- (c)

- vezető edző

- (d)

- dietetikus

- (e)

- táplálkozástudományi szakember

- (f)

- orvos

- (g)

- család

- (h)

- barátok

- (i)

- internetes keresés (kérjük adja meg a használt webhelyeket)

- (j)

- média (magazinok, rádió, TV)

- (k)

- közösségi média (Facebook, Twitter)

- (l)

- csapattársak

- (a)

- csak táplálkozással kapcsolatos információt kapok

- (b)

- táplálkozással kapcsolatos információt kapok és táplálkozástudományi szakemberrel/dietetikussal is konzultálok

- (c)

- egyik sem

- (a)

- igen, a táplálkozással kapcsolatos ismeretek elsajátítására

- (b)

- igen, a táplálkozással kapcsolatos ismeretek elsajátítására és a dietetikusokkal/táplálkozástudományi szakemberekkel történő kapcsolattartásra egyaránt

- (c)

- nem, ez nem a sportszövetségek feladata

- (a)

- igen (kérem írja le, hogy miket szed jelenleg)

- (b)

- nem

- (a)

- kiváló

- (b)

- átlag feletti

- (c)

- átlag alatti

- (d)

- hiányos

- (a)

- nagyon egyetértek

- (b)

- egyetértek

- (c)

- nem értek egyet

- (d)

- nem értek egyet, de nem is cáfolom

- (a)

- igen

- (b)

- nem

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- magas

- (b)

- alacsony

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- magas

- (b)

- alacsony

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- magas

- (b)

- alacsony

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- elég

- (b)

- nem elég

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- elég

- (b)

- nem elég

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- elég

- (b)

- nem elég

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- elég

- (b)

- nem elég

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- elég

- (b)

- nem elég

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- 100 g (1 g/testtömegkilogramm)

- (b)

- 150 g (1.5 g/testtömegkilogramm)

- (c)

- 500 g (5 g/testtömegkilogramm)

- (d)

- fogyasszon annyi fehérjét, amennyit csak tud

- (e)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- folyadék, zsír és szénhidrát

- (b)

- folyadék, rost és szénhidrát

- (c)

- folyadék és szénhidrát van

- (d)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- egyetértek

- (b)

- nem értek egyet

- (c)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- fehérje turmix

- (b)

- érett banán

- (c)

- 2 főtt tojás

- (d)

- egy marék olajos mag

- (e)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- 1.5 g/testtömegkilogramm a legtöbb sportoló számára

- (b)

- 1 g/testtömegkilogramm a legtöbb sportoló számára

- (c)

- 0.3 g/testtömeg kilogramm a legtöbb sportoló számára

- (d)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- koffein

- (b)

- ferulinsav

- (c)

- bikarbonát

- (d)

- leucin

- (e)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

- (a)

- koffein

- (b)

- bikarbonát

- (c)

- karnitin

- (d)

- tesztoszteron használatát

- (e)

- nem vagyok biztos a válaszban

References

- Magee, M.K.; Jones, M.T.; Fields, J.B.; Kresta, J.; Khurelbaatar, C.; Dodge, C.; Merfeld, B.; Ambrosius, A.; Carpenter, M.; Jagim, A.R. Body Composition, Energy Availability, Risk of Eating Disorder, and Sport Nutrition Knowledge in Young Athletes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gemert, W.A.; van der Palen, J.; Monninkhof, E.M.; Rozeboom, A.; Peters, R.; Wittink, H.; Schuit, A.J.; Peeters, P.H. Quality of Life after Diet or Exercise-Induced Weight Loss in Overweight to Obese Postmenopausal Women: The SHAPE-2 Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imayama, I.; Alfano, C.M.; Kong, A.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Bain, C.E.; Xiao, L.; Duggan, C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Campbell, K.L.; Blackburn, G.L.; et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise interventions effects on quality of life in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.D.; Freedson, P.S. Combined associations of physical activity, diet quality and their changes over time with mortality: Findings from the EPIC-Norfolk study, United Kingdom. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, E.; Gottesman, K.; Hamlett, P.; Mattar, L.; Robinson, J.; Tovar, A.; Rozga, M. Impact of Nutrition and Physical Activity Interventions Provided by Nutrition and Exercise Practitioners for the Adult General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuenschwander, M.; Ballon, A.; Weber, K.S.; Norat, T.; Aune, D.; Schwingshackl, L.; Schlesinger, S. Role of diet in type 2 diabetes incidence: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. BMJ 2019, 366, l2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Samanes, A.; Trakman, G.; Roberts, J.D. Editorial: Nutrition for team and individual sport athletes. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1524748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Australian team sports athletes prefer dietitians, the internet and nutritionists for sports nutrition information. Nutr. Diet. J. Dietit. Assoc. Aust. 2019, 76, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; Erdman, K.A.; Burke, L.M. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Espino, K.; Rodas-Font, G.; Farran-Codina, A. Sport Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes, Sources of Information, and Dietary Habits of Sport-Team Athletes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, A.J.; Leach, R.; Mann, H.; Robinson, S.; Burnett, D.O.; Babu, J.R.; Frugé, A.D. Nutrition Knowledge of Collegiate Athletes in the United States and the Impact of Sports Dietitians on Related Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Schneider, N.; Vanguri, P.; Issac, L. Effects of Education, Nutrition, and Psychology on Preventing the Female Athlete Triad. Cureus 2024, 16, e55380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boidin, A.; Tam, R.; Mitchell, L.; Cox, G.R.; O’Connor, H. The effectiveness of nutrition education programmes on improving dietary intake in athletes: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Díaz, S.; Yanci, J.; Castillo, D.; Scanlan, A.T.; Raya-González, J. Effects of Nutrition Education Interventions in Team Sport Players. A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, K.; Curley, T. Nutrition Knowledge and Practices of Varsity Coaches at a Canadian University. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2014, 75, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tektunalı Akman, C.; Gönen Aydın, C.; Ersoy, G. The effect of nutrition education sessions on energy availability, body composition, eating attitude and sports nutrition knowledge in young female endurance athletes. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1289448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucherville Pereira, I.S.; Lima, K.R.; Teodoro da Silva, R.C.; Pereira, R.C.; Fernandes da Silva, S.; Gomes de Moura, A.; César de Abreu, W. Evaluation of general and sports nutritional knowledge of recreational athletes. Nutr. Health 2025, 31, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leen Smith, B.; Carey, C.C.; O’Connell, K.; Twomey, S.; McCarthy, E.K. Nutrition knowledge, supplementation practices and access to nutrition supports of collegiate student athletes in Ireland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, W.L.; Faghy, M.A.; Sparks, A.; Newbury, J.W.; Gough, L.A. The Effects of a Nutrition Education Intervention on Sports Nutrition Knowledge during a Competitive Season in Highly Trained Adolescent Swimmers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, S.; O’Connor, H.; Michael, S.; Gifford, J.; Naughton, G. Nutrition Knowledge in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2011, 21, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Devlin, B.L.; Belski, R. A Systematic Review of Athletes’ and Coaches’ Nutrition Knowledge and Reflections on the Quality of Current Nutrition Knowledge Measures. Nutrients 2016, 8, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, R.; Gifford, J.A.; Beck, K.L. Recent Developments in the Assessment of Nutrition Knowledge in Athletes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiczak, A.; Devlin, B.L.; Forsyth, A.; Trakman, G.L. A systematic review update of athletes’ nutrition knowledge and association with dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1156–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.; Weerasinghe, K.; Trakman, G.; Madhujith, T.; Hills, A.P.; Kalupahana, N.S. Sports Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaires Developed for the Athletic Population: A Systematic Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Development and validation of a brief general and sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire and assessment of athletes’ nutrition knowledge. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Developing and validating a nutrition knowledge questionnaire: Key methods and considerations. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2670–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, S.; Bray, A.; Kim, B. The relationship between nutrition knowledge and low energy availability risk in collegiate athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2024, 27, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Trakman, G.; Al Kilani, A. General and sports nutrition knowledge among Jordanian adult coaches and athletes: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, J.B.A.; Mendes, G.F.; Zandonadi, R.P.; da Costa, T.H.M.; Saunders, B.; Reis, C.E.G. Translation and Validation of the Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire in Brazil (NSKQ-BR). Nutrients 2024, 16, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, M.A.D.S.D.; Trakman, G.L.; Mello, J.B.; de Andrade, M.X.; Carlet, R.; Machado, C.L.F.; Silveira Pinto, R.; da Cunha Voser, R. Conocimiento nutricional y hábitos alimenticios de la Selección Brasileña de Fútbol Sala. Rev. Española Nutr. Humana Y Dietética 2021, 25 (Suppl. S1), e1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Carter, J.L.; Brooks, F.; Roberts, C.J. Caregivers nutrition knowledge and perspectives on the enablers and barriers to nutrition provision for male academy football players. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2495879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaoutis, G.; Alepoudea, M.; Tambalis, K.D.; Sidossis, L.S. Dietary Intake, Body Composition, and Nutritional Knowledge of Elite Handball Players. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albassam, R.S.; Alahmadi, A.K.; Alfawaz, W.A. Eating Attitudes and Characteristics of Physical Activity Practitioners and Athletes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Brown, F.; Forsyth, A.; Belski, R. Modifications to the nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSQK) and abridged nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (ANSKQ). J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. The nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSKQ): Development and validation using classical test theory and Rasch analysis. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bolarinwa, O.A. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015, 22, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. POLYMAT-C: A comprehensive SPSS program for computing the polychoric correlation matrix. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M.E.; Smith, G.T. Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhail, D.; Rolls, B.; Yost, K.; Balls-Berry, J.; Gall, M.; Blixt, K.; Novotny, P.; Albertie, M.; Jensen, M. Development and validation testing of a weight management nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Int. J. Obes. (2005) 2020, 44, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation—Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/behealthy/physical-activity (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsma, K. On the Use, the Misuse, and the Very Limited Usefulness of Cronbach’s Alpha. Psychometrika 2009, 74, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Lennox, R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.N.; Richard, D.C.S.; Kubany, E.S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Ibáñez, H.; Drehmer, E.; da Silva, V.S.; Souza, I.; Silva, D.A.S.; Vieira, F. Relationship of Body Composition and Somatotype with Physical Activity Level and Nutrition Knowledge in Elite and Non-Elite Orienteering Athletes. Nutrients 2025, 17, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Elite (n = 132) | Recreational (n = 1203) | Total Sample (n = 1335) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (n = 57) | Female (n = 75) | Male (n = 668) | Female (n = 535) | |

| Age | 19.89 (SD = 2.63) | 20.77 (SD = 3.91) | 22.91 (SD = 8.39) | 23.13 (SD = 8.45) | 22.74 (SD = 8.11) |

| Height (cm) | 184.86 (SD = 8.99) | 165.51 (SD = 18.13) | 181.61 (SD = 11.19) | 168.01 (SD = 6.52) | 174.99 (SD = 11.21) |

| Weight (kgs) | 81.45 (SD = 12.35) | 59.98 (SD = 8.81) | 78.88 (SD = 11.79) | 62.16 (SD = 10.11) | 70.62 (SD = 10.76) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.02 (SD = 4.91) | 21.49 (SD = 2.49) | 23.93 (SD = 3.27) | 21.98 (SD = 3.09) | 22.85 (SD = 3.44) |

| Training hours (per week) | 17.41 (SD = 6.60) | 14.02 (SD = 6.99) | 9.66 (SD = 5.13) | 8.61 (SD = 5.02) | 12.43 (SD = 5.93) |

| Years in sport | 11.01 (SD = 3.88) | 11.06 (SD = 4.51) | 10.98 (SD = 6.47) | 10.26 (SD = 5.88) | 10.82 (SD = 5.19) |

| HLC (local) (n/%) | - | - | 98 (14.7) | 95 (17.7) | 193 (14.4) |

| HLC (regional) (n/%) | - | 3 (4) | 93 (13.9) | 48 (8.9) | 144 (10.78) |

| HLC (national) (n/%) | 5 (8.7) | 7 (9.3) | 317 (47.5) | 220 (41.2) | 549 (41.21) |

| HLC (international) (n/%) | 52 (91.3) | 65 (86.7) | 160 (23.9) | 172 (32.2) | 449 (33.6) |

| Sport Discipline | Elite (n = 132) | Recreational (n = 1203) | Total Sample (n = 1335) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (n = 57) | Female (n = 75) | Male (n = 668) | Female (n = 535) | |

| Aesthetic (n/%) | 1 (1.7) | 18 (24) | 39 (5.9) | 133 (24.8) | 191 (14.3) |

| Endurance (n/%) | 10 (17.6) | 9 (12) | 96 (14.3) | 117 (21.9) | 232 (17.5) |

| Weight-dependent (n/%) | 10 (17.6) | 11 (14.7) | 72 (10.7) | 36 (6.8) | 129 (9.6) |

| Power (n/%) | - | - | 2 (0.3) | - | 2 (0.14) |

| Power-endurance (n/%) | 16 (28.1) | 8 (10.7) | 62 (9.3) | 25 (4.7) | 111 (8.3) |

| Team (n/%) | 17 (29.8) | 29 (38.6) | 391 (58.6) | 222 (41.5) | 659 (49.3) |

| Technical (n/%) | 3 (5.2) | - | 6 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | 11 (0.82) |

| General Knowledge of Nutrition | ID | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The surplus energy consumed from protein may increase the fat content of the body. | 0.40 |

| 2. | Some body fat is needed in order to recover from diseases. | 0.49 |

| 3. | In your opinion does Trappista cheese have high or low fat content? | 0.78 |

| 4. | In your opinion does margarine have high or low fat content? | 0.74 |

| 5. | In your opinion does honey have high or low fat content? | 0.74 |

| 6. | The body is able to use protein for the synthesis of muscular protein only to a limited extent. | 0.61 |

| 7. | Eggs contain all the essential amino acids needed for the body. | 0.53 |

| 8. | Thiamine (vitamin B1) is necessary for providing the muscles with oxygen. | 0.18 |

| 9. | Vitamins provide energy (in the form of kilojoule/calorie). | 0.49 |

| 10. | In your opinion may your bodyweight increase because of alcohol? | 0.88 |

| 11. | Heavy drinking might be defined as the following: | 0.38 |

| Sporting nutrition-based knowledge | ||

| 1. | In your opinion does a medium-sized banana contain enough carbohydrates for glucose resynthesis/replacement after an intensive training session? | 0.67 |

| 2. | In your opinion does one cup of cooked quinoa and one tin of tuna contain enough carbohydrates for the regeneration after an intensive training session? | 0.51 |

| 3. | In your opinion does 100 grams of chicken breast contain enough protein for muscular growth after an intensive training? | 0.36 |

| 4. | In your opinion does one cup of cooked beans contain enough protein for muscular growth after an intensive weightlifting training? | 0.52 |

| 5. | In your opinion does one cup of cooked quinoa contain enough protein for muscular growth after an intensive weightlifting training? | 0.53 |

| 6. | In order to grow muscles, the most important thing is to consume more protein. | 0.23 |

| 7. | Which is the most optimal meal to have after-training for those who want to grow muscles (assuming they have already had breakfast and elevenses)? | 0.32 |

| 8. | If we train at low intensity, our body utilizes mainly fats as a source of energy. | 0.48 |

| 9. | Vegetarian sportsmen are able to cover their protein needs without food supplements. | 0.47 |

| 10. | The daily protein need of a sportsman of 100 kg bodyweight, in a well-trained condition, doing exercises of resistance nature, is approximately: | 0.49 |

| 11. | The optimal calcium intake for sportsmen aged 15–24 years is 500 mg. | 0.22 |

| 12. | A trained person maintaining a balanced diet may improve their sporting achievement by eating food rich in vitamins and minerals. | 0.08 |

| 13. | Supplementation of vitamin C for sportsmen is recommended in all cases. | 0.12 |

| 14. | Sportsmen must drink water to: | 0.21 |

| 15. | According to experts, sportsmen need: | 0.29 |

| 16. | Before a competition/race/tournament sportsmen should have such foods which contain much: | 0.40 |

| 17. | In 60–90-minute-long trainings the consumption of 30–60 g carbohydrates per hour is recommended. | 0.34 |

| 18. | The consumption of carbohydrates during training helps keep the level of blood glucose stable. | 0.58 |

| 19. | Which of the following complies the most with the recommendation referring to the snack eaten during an approximately 90-minute-long training of high intensity? | 0.45 |

| 20. | In your opinion how much protein-consumption is recommended by experts after a training of resistance nature? | 0.07 |

| 21. | The labels of food supplements sometimes contain such information that is not true. | 0.51 |

| 22. | All food supplements are tested in order to make sure that they are safe and not contaminated. | 0.39 |

| 23. | From the following food supplements which is/are said not to have enough proof of improving body composition and improving sport achievement? | 0.10 |

| 24. | The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) bans: | 0.70 |

| Variable | Subscales | Min | Max | M | SD | Sk | Ku |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition for sport knowledge | 0 | 23 | 10.42 | 3.38 | 0.062 | 0.459 | |

| F1-FEP | 0 | 12 | 7.03 | 2.51 | −0.285 | −0.412 | |

| F2-MPE | 0 | 5 | 0.59 | 0.91 | 1.816 | 3.514 | |

| F3-UM | 0 | 6 | 2.79 | 1.48 | 0.168 | −0.464 |

| Component Loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item o | Item n | Item H | PC 1 | PC 2 | PC 3 |

| Gen3 | A2 | FEP1 | 0.462 | −0.201 | 0.222 |

| Gen4 | A3 | FEP2 | 0.440 | −0.288 | 0.232 |

| Gen5 | A4 | FEP3 | 0.517 | −0.055 | 0.240 |

| Gen9 | S7 | FEP4 | 0.632 | 0.258 | −0.025 |

| Sport1 | S1 | FEP5 | 0.429 | −0.166 | −0.280 |

| Sport2 | S2 | FEP6 | 0.447 | 0.069 | −0.309 |

| Sport4 | S4 | FEP7 | 0.489 | 0.087 | −0.069 |

| Sport5 | S5 | FEP8 | 0.624 | 0.215 | 0.067 |

| Sport10 | S7 | FEP9 | 0.404 | 0.149 | 0.238 |

| Sport16 | S11 | FEP10 | 0.495 | 0.084 | 0.086 |

| Sport19 | S13 | FEP11 | 0.538 | 0.007 | 0.144 |

| Sport24 | S16 | FEP12 | 0.579 | −0.199 | 0.190 |

| Sport11 | S8 | MPE1 | 0.122 | 0.586 | 0.243 |

| Sport12 | S9 | MPE2 | −0.233 | 0.736 | −0.120 |

| Sport13 | S10 | MPE3 | 0.067 | 0.764 | −0.103 |

| Sport20 | S14 | MPE4 | 0.133 | 0.659 | 0.107 |

| Sport23 | S15 | MPE5 | 0.075 | 0.640 | 0.322 |

| Gen2 | A1 | UM1 | 0.078 | 0.076 | 0.453 |

| Gen6 | A5 | UM2 | 0.282 | −0.038 | 0.455 |

| Gen7 | A6 | UM3 | −0.016 | −0.010 | 0.520 |

| Sport3 | S3 | UM4 | −0.009 | 0.078 | 0.485 |

| Sport8 | S6 | UM5 | 0.179 | −0.015 | 0.504 |

| Sport17 | S12 | UM6 | 0.059 | 0.124 | 0.601 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovács, R.E.; Tornóczky, G.J.; Trakman, G.L.; Boros, S.; Karsai, I. Initial Validation of the Hungarian Version of Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (ANSKQ-HU). Sports 2025, 13, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120422

Kovács RE, Tornóczky GJ, Trakman GL, Boros S, Karsai I. Initial Validation of the Hungarian Version of Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (ANSKQ-HU). Sports. 2025; 13(12):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120422

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovács, Réka Erika, Gusztáv József Tornóczky, Gina Louise Trakman, Szilvia Boros, and István Karsai. 2025. "Initial Validation of the Hungarian Version of Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (ANSKQ-HU)" Sports 13, no. 12: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120422

APA StyleKovács, R. E., Tornóczky, G. J., Trakman, G. L., Boros, S., & Karsai, I. (2025). Initial Validation of the Hungarian Version of Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (ANSKQ-HU). Sports, 13(12), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120422